10. The Rooting of Islam in Bengal

Why are you afraid of demons, when you have got the religious books?

From the perspective of Mughal authorities in Dhaka or Murshidabad, the hundreds of tiny rural mosques and shrines established in the interior of eastern Bengal served as agents for the transformation of jungle into arable land and the construction of stable microsocieties loyal to the Mughal state. From a religious perspective, however, these same institutions facilitated the diffusion of uniquely Islamic conceptions of divine and human authority among groups under their socioeconomic influence. Government documents from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries note the establishment of new Friday assemblies or “circles” (iqāmat-i ḥalqa-yi jum‘a) at mosques or shrines patronized by the Mughal government, and refer to such communities as “dependents” (vā bastagān) of those same institutions.[1]

In forest tracts recently cleared for cultivation, the appearance of such assemblies coincided with the establishment of religious rites such as the fātiḥa at rural mosques and shrines. Named after the opening verse of the Qur’an, which would have been recited on the occasion, the fātiḥa was a simple rite of remembrance of the dead, usually followed by a feast. One type consisted of intercessory prayers offered to the Shi‘a successors (imām) to the leadership of the Prophet Muhammad.[2] In another, the fātiḥa-yi darvīshī, prayers were offered in memory of local darvīshes, that is, Muslim holy men.[3] Lists of persons supported by village mosques or shrines frequently mention “leaders in fātiḥa,” “readers of fātiḥa,” or simply “Qur’an-readers.”[4]

The cumulative effect of such simple observances was to promote the cult of Allah and associated lesser agencies in the religious universe of eastern Bengal. This process is usually glossed as “religious conversion,” but the use of this phrase requires a precise understanding of both “religion” and “conversion.” If one accepts the definition of religion proposed by the anthropologist Melford Spiro—“an institution consisting of culturally patterned interaction with culturally postulated superhuman beings”[5]—then it follows that, whatever other changes might occur, a society’s acquisition of a new religious identity will involve a change in the identity of the superhuman beings postulated by that society. In tracing the process of Islamization in pre-modern Bengal, then, we need to focus on the increasing attention given to Allah, as well as to beings such as Iblis (Satan), Adam, Muhammad, the angel Gabriel, a host of minor spirits (jinn), and the many saints (auliyā or pīrs) who entered popular traditions as intermediaries between human society and Allah. The term conversion is perhaps misleading when applied to this process, since it ordinarily connotes a sudden and total transformation in which a prior religious identity is wholly rejected and replaced by a new one. In reality, in Bengal, as in South Asian history generally, the process of Islamization as a social phenomenon proceeded so gradually as to be nearly imperceptible.

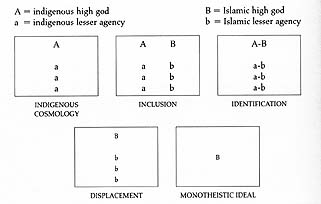

Nonetheless, from the position of historical retrospect, one may discern three analytically distinct aspects to the process, each referring to a different relationship between Islamic and Indian superhuman agencies. One of these I am calling inclusion; a second, identification; and a third, displacement. By inclusion is meant the process by which Islamic superhuman agencies became accepted in local Bengali cosmologies alongside local divinities already embedded therein. By identification is meant the process by which Islamic superhuman agencies ceased merely to coexist alongside Bengali agencies, but actually merged with them, as when the Arabic name Allah was used interchangeably with the Sanskrit Niraṇjan. And finally, by displacement is meant the process by which the names of Islamic superhuman agencies replaced those of other divinities in local cosmologies. The three terms inclusion,identification, and displacement are of course only heuristic categories, proposed in an attempt to organize and grasp intellectually what was on the ground a very complex and fluid process.

| • | • | • |

Inclusion

In the corpus of premodern Bengali literature celebrating indigenous deities such as Manasa, Chandi, Satya Pir, Dharma, or Daksin Ray, one readily sees local cosmologies expanding in order to accommodate new superhuman beings introduced by foreign Muslims.[6] For example, we have seen that the Rāy-Maṅgala, a poem composed in 1686, celebrated both the Bengali tiger god Daksin Ray (“King of the South”) and a Muslim pioneer named Badi‘ Ghazi Khan. According to this poem, conflict between the two was resolved, not by one defeating or displacing the other, but by the elevation of Badi‘ Ghazi Khan to the status of a revered saint, and by the peaceful coexistence of the two figures, who would thenceforth hold a dual religious authority over the Sundarban forests of southern Bengal. This dual authority was represented by the installation of the symbol of the tiger god’s head at the burial mound of the Muslim saint. The two were not, however, fused into a single religious personage, but remained mutually distinct. A separation of the indigenous and the exogenous was also maintained at a higher level. The agent who resolved the conflict between Daksin Ray and Badi‘ Ghazi Khan was neither the Hindu god Krishna nor the Islamic prophet Muhammad, but a single figure represented as half Krishna and half Muhammad.[7] Islamic superhuman agencies were thus associated with indigenous agencies at two levels, though not yet fully identified with them.[8]

The inclusion of Muslim alongside local divinities is also seen in the rich tradition of folk ballads passed on orally by generations of professional bards. Since they were normally preceded by invocations (bandanā) in which Bengal’s rustic bards invoked any and all divinities considered locally powerful, these ballads tell us much about the religious universe of the unlettered audience to whom they were sung. Here we may consider the opening lines of “Nizam Dacoit,” a ballad of Chittagong District dating from the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries:[9]

First of all I bow down to the Supreme Deity [Prabhu], and secondly to (the same Omnipotent Being conceived as) the Creator [Sirjan]; and thirdly to the benign Incarnation of Light. The Koran and other scriptural texts I regard as revelation—the sacred utterances of the Lord [Prabhu] himself.

When the Lord was engrossed in deep meditation, the luminous figure of Mahomet flashed before His mind’s eye, and as He gazed and gazed upon the vision, He began to feel a certain softening of the heart. So out of love, He created the prophet Mahomet and sent him down to the earth as the very flower of the Robikul (the solar race). He next created the entire universe. Had there been no incarnation of Mahomet, there would not have been established the seat of God [arskors, from Ar., ‘arsh, “throne of God”] in all the three worlds.

All reverence to Abdulla and to Amina; salutations at the feet of her, who bore in the womb Mahomet (the deliverer) of the earth. All honour to the city of Mecca in the west and to the Mahomedan saints; and further west, I do reverence to the city of Medina—the burial place of our Rosul [Prophet]. Bibi Fatemah, daughter of Rosul, honoured of all, was called “mother” by all excepting Ali.

In the north, I offer my tribute of respects to the Himalayas, beneath whose snowy heights lies the entire universe. I bow down to the rising sun in the east, and also to the shrine of Vrindavan, together with Lord Krishna, the Eternal Lover of sweet Radha. I next do reverence to the milky rivers and the ocean, dashing against the two shores, with sandy shoals in the middle. In all the four directions, I tender my respectful compliments to all the four sects of the Mussalmans. I pay homage to Mother Earth [Basumātā] below and to the heavens above.

I bow down to Mother Isamati in the village of Raunya and also to the mosque of the great Pir at Nawapara. I next make my salam to the hill of Kavalyamura to the right and the mosque of Hirmai to the left. The great upholders of truth are passed through these tracts. The river Sankha is also sacred.…Tendering my regards to all the sacred spots, I proceed onwards and arrive at Sita Ghat [Sitakund], where I offer my tribute of worshipful regards to that ideal of womanly virtue—Sita Devi—and also to her lord Raghunatha [Rama].[10]

Clearly, the religious culture of the area in which this ballad was sung included a broad spectrum of superhuman agencies, ranging from nearby pīrs and rivers to the distant Himalayas and even the sublime Absolute of Indian philosophy. Above all, the invocation illustrates how easily Islamic superhuman figures could be included in what appears to have been a fluid, expandable cosmology. As in the case of the poem Rāy-Maṅgala, moreover, the poet did not identify these powers with one another, but treated them as separate entities.

The poem also includes both indigenous and exogenous religious ideas. On the one hand, we see the tenacity of the Bengali emphasis on divine power as manifested in female agency—Mother Isamati, Mother Earth, Sita, and Radha. It is significant that this emphasis is extended to include prominent females of Islamic history: special reverence goes to Amina, the Prophet’s mother, and Fatima, his daughter, is referred to as “mother” to all except her husband, ‘Ali. On the other hand, the poem shows that themes wholly foreign to the delta had also infiltrated the religious universe of the Bengali countryside. The emphasis on Light, the association of Light with the Prophet Muhammad, and the creation of the world as the result of God’s desire to see himself, all confirm what we know from Mughal government documents examined in previous chapters—that many of the men who played decisive roles in disseminating Islamic ideas in Bengal were steeped in Sufi metaphysics.

It is instructive to compare what these folk ballads have to say about the establishment of new mosques and shrines in eastern Bengal with what we know from the Mughal records discussed in chapters 8 and 9. Whereas government sanads describe the founding of local institutions from the perspective of the Mughal bureaucratic machine, the Bengali folk ballad tradition views the same process from the perspective of its rural clientele. Listen to the sixteenth-century ballad “Kanka and Lila,” set in what is now Mymensingh District. “At this time,” goes the ballad,

Although no known Mughal sanads pertain to this man or the mosque he built, it is likely that he, like the many pīrs and mosque functionaries discussed in the preceding chapters, had received government support in the form of a tax-free land grant intended for clearing jungle, establishing a rice-cultivating community, and building the mosque. In any event, it is evident that, by virtue of his charisma and his association with magic, the pīr of this ballad was understood as spiritually powerful. Villagers would likely have conferred on him an intermediate status between the human world and the transcendent power associated with his mosque.there came a Mahomedan pir to that village. He built a mosque in its outskirts, and for the whole day sat under a fig tree. The whole space he cleared with care so that there was not one tuft of grass left. His fame soon spread far and wide. Everybody talked of the occult powers that he possessed. If a sick man called on him he would cure him at once by dust or some trifle touched by him. He read and spoke the innermost thoughts of a man before he opened his mouth. He took a little dust in his hand and out of it prepared sugar balls to the astonishment of the boys and girls who gathered around him. They greatly relished these presents from him. Hundreds of men and women came every day to pay him their respects. Presents of rice, fruits, and other delicious food, goats, chickens and fowls came in large quantities to his doors. Of these offerings the pir did not touch a bit but freely distributed all amongst the poor.[11]

Given that this part of Bengal was overwhelmingly Muslim by the time of the earliest census reports in the late nineteenth century, it is tempting to hypothesize that the holy man’s intermediary status helped in easing the local community’s transfer of religious allegiances from non-Islam to Islam. But what does that actually mean? One can by no means assume that the gap between “Islam” and “non-Islam” in sixteenth-century Mymensingh was the same as that of the late twentieth century. Indeed, the idea of Islam as a closed system with definite and rigid boundaries is itself largely a product of nineteenth- and twentieth-century reform movements, whereas for rural Bengalis of the premodern period, the line separating “non-Islam” from “Islam” appears rather to have been porous, tenuous, and shifting. Indeed, such boundaries seem hardly to have been present at all. Popular literature dating from the seventeenth century, such as the Mymensingh ballads cited above, evolved amongst communities of people who were remarkably open to accepting any sort of agency, human or superhuman, that might assist them in coping with life’s everyday problems.

On this point we can profit from the insights of modern ethnographic research. Writing of religious change among the Yoruba of modern Nigeria, the anthropologist J. D.Y. Peel observes: “The more religion is regarded as a technique, whose effectiveness the individual may estimate for himself, the readier will the individual be to try out other techniques which seem promising. He will not be inclined to rely exclusively on one technique just for the sake of simplicity, nor will he prefer other techniques.”[12] Similarly, Melford Spiro notes the ruthless pragmatism that the Ifaluk peoples of the Central Carolines (in the western Pacific Ocean) had toward superhuman power. “When I asked a group of Ifaluk men about the power of the spirit whose therapeutic intervention was being invoked in a healing ceremony, their response was ‘We don’t know if he is powerful or not; maybe he is, maybe he isn’t. If he is not, we’ll throw him away’ (i.e., we will no longer concern ourselves with him).”[13] In the 1950s Igor Kopytoff remarked on the spirit of pragmatism with which the Suku of the Belgian Congo (now Zaire) assessed religious power. “There is a pervasive assumption in Suku culture,” wrote Kopytoff,

It is this pragmatic attitude to religious phenomena that characterizes the phase of religious change in Bengal I am calling inclusion.that somewhere, somehow, other methods exist for dealing with the culturally-given causes of misfortune—methods already known to others or as yet undiscovered. This instrumental orientation makes the system very much akin to a technology which is ever-receptive to innovation and trials of new means for the same ends.…Spectacular abandonment of old medicines does not mean disbelief in the old as much as the acceptance of the greater efficacy of the new, in somewhat the same way that the adoption of a diesel engine does not mean the rejection of the principles of steam power. When an innovation is seen to be a failure, a return to the old proven techniques is a logical step.[14]

In sum, the worldview of the people here considered was the very opposite of a zero-sum-game cosmology, in which the addition of any one element requires the elimination of another. When Bengali communities began incorporating techniques or beliefs that we would call “Islamic” into their village systems, they did not consider these as challenging other techniques or beliefs already in the system, far less as requiring their outright abandonment. The holy man who appeared in sixteenth-century rural Mymensingh was locally believed to have brought something new to the village, some new access to superhuman power that the villagers had never before witnessed. Everyone spoke of his occult skills and of his ability to cure the sick and read the minds of others. But his arrival did not require a rejection of other cults—dedicated perhaps to the goddess Chandi or Manasa, the god Krishna, or a tiger god—that were locally familiar and known to be efficacious in tapping superhuman power. Nor did the saint come to the village proclaiming with great éclat that a New Age had dawned, a New World been ushered in. As Kopytoff writes of the Suku: “Instead of the promise of a new world, we have but the discovery of a new gimmick for handling the same old world.”[15] This predisposition to accept new “gimmicks” to deal with old problems, while not itself constituting the full religious transformation that subsequent generations would call “conversion,” was nonetheless a necessary first step along this road.

| • | • | • |

Identification

Analytically distinct from merely including Islamic with local superhuman beings in an expanding, accordionlike cosmology was the process of identifying superhuman beings with one another. A classic example of this is seen in a bilingual Arabic and Sanskrit inscription from a thirteenth-century mosque in the coastal town of Veraval in Gujarat. Dated 1264, the inscription records that an Iranian merchant from Hormuz named Nur al-Din Firuz sponsored the construction of a mosque there. The Arabic text refers to the deity worshiped in the mosque as Allah, and describes Nur al-Din as “the king (sulṭān) of sea-men, the king of the kings of traders,” and “the sun of Islam and the Muslims.” By contrast, the Sanskrit text of the same inscription addresses the supreme god by the names Viśvanātha (“lord of the universe”), śunyarūpa (“one whose form is of the void”), and Viśvarūpa (“having various forms”). Moreover, it records that the mosque was built in the year “662 of the Rasūla Mahammada, the preceptor (bōdhaka) of the sailors (nau-jana) devoted to Viśvanātha.” The Sanskrit version thus identifies the deity worshiped in the mosque as Viśvanātha, and the prophet of Islam as a bōdhaka—that is, “preceptor,” “elder,” or “wise man.” Similarly, it styles the mosque’s builder, Nur al-Din Firuz, as adharma-bhāndaya, or “supporter of dharma”—that is, cosmic/social order as understood in classical Indian thought.[16] So, while the Arabic text presents the worldview of the Muslim patron, the Sanskrit text reflects that of the proximate Indian population, which simply identified Islam’s God with Viśvanātha, Islam’s prophet with an Indian bōdhaka, and the Muslim patron of this particular mosque with a “supporter of dharma.” In short, the local Gujarati population, while looking at a monument its patrons dedicated to Allah, saw one dedicated to Viśvanātha.

In Bengali literature dating from the sixteenth century—romances, epics, narratives, and devotional poems—we find identifications of a similar type.[17] The sixteenth-century poet Haji Muhammad identified the Arabic Allah with Gosāī (Skt., “Master”),[18] Saiyid Murtaza identified the Prophet’s daughter Fatima with Jagat-jananī (Skt., “Mother of the world”),[19] and Saiyid Sultan identified the God of Adam, Abraham, and Moses with Prabhu (Skt., “Lord”) or, more frequently, Niraṇjan (Skt., “One without color,” i.e., without qualities).[20] Later, the eighteenth-century poet ‘Ali Raja identified Allah with Niraṇjan, Iśvar (Skt., “God”), Jagat Iśvar (Skt., “God of the universe”), and Kartār (Skt., “Creator”).[21] Even while forest pioneers on the eastern frontier were planting the institutional foundations of Islamic rituals, then, Bengali poets deepened the semantic meaning of these rituals by identifying the lore and even the superhuman agencies of an originally foreign creed with those of the local culture.

More than just translating Perso-Islamic romantic literature into the Bengali language, these poets attempted to adapt the whole range of Perso-Islamic civilization to the Bengali cultural universe.[22] This included Perso-Islamic aesthetic and literary sensibilities, as well as conceptions of divinity and superhuman agency. Thus the Nile river was identified with the Ganges, and a story set in biblical Egypt alludes to dark forests filled with tigers and elephants. The countryside in such stories abounds with banana and mango trees, peacocks and chirping parrots; people eat fish, curried rice, ghee, and sweet yogurt, and chew betel; women adorn themselves with sandal paste and glitter in silk saris and glass and gold bangles. Everywhere one smells the sweet aroma of fresh rice plants.[23]

The reasons poets employed this mode of literary transmission are not hard to find. Already exposed somewhat to Brahmanic ideas of the proper social order and its supporting ideological framework, the rural masses of the eastern delta’s expanding rice frontier were familiar with the Hindu epics. One sixteenth-century poet wrote that “Muslims as well as Hindus in every home” would read the Mahābhārata, the great religious epic of classical India. Another poet of that century wrote of Muslims being moved to tears on hearing of Rama’s loss of his beloved Sita in the epic Rāmāyaṇa.[24] In addition to such Vaishnava sympathies, the people of this period were also saturated with the maṅgala-kāvya literature that celebrated the exploits, power, and grace of specifically Bengali folk deities like Manasa and Chandi. It is hardly surprising, then, that romantic tales from the Islamic tradition drew on this rich indigenous substratum of religious culture. For example, an eighteenth-century Bengali version of the popular Iranian story of Joseph and Zulaikha employs imagery clearly recalling Radha’s passionate love for Krishna, the central motif of the Bengali Vaishnava devotional movement. “Your face is as bright as the full moon,” runs a description of the biblical Joseph,

Similarly, the Sufi Saiyid Sultan, the epic poet of the late sixteenth-century Chittagong region, spares no detail in endowing Eve with the attributes of a Bengali beauty. She uses sandal powder and wraps her hair in a bun adorned with a string of pearls and flowers. She wears black eye paste, and a pearl necklace is draped around her neck. Adam was struck by the beauty of the spot (sindur) on her forehead “because it reminded him of the sun in the sky.”[26]and your eyes are black as if bees are buzzing round them. Your eyebrows are like the bow of Kama [the Indian god of love] and your ears like lotuses which grow on shore. Your waist is as slim as that of a prowling tigress. Your step is as light as a bird’s and when they see it even sages forget all else. Your body is as perfect as a well-made string of pearls. A maid, therefore, cannot control herself and longs for your embrace.[25]

The authors of this literature, Bengali Muslims, consciously presented Islamic imagery and ideas in terms readily familiar to a rural population of nominal Muslims saturated with folk Bengali and Hindu religious ideas.[27] Yet in doing so they felt a degree of anguish. Although certain that Arabic was the appropriate literary vehicle for the transmission of Islamic ideas, they could not use a language with which their Bengali audience was unfamiliar. Referring to this dilemma, the seventeenth-century poet ‘Abd al-Nabi wrote, “I am afraid in my heart lest God should be annoyed with me for having rendered Islamic scriptures in Bengali. But I put aside my fear and firmly resolve to write for the good of common people.”[28] Similar feelings were voiced by Saiyid Sultan, who lamented,

Such expressions of tension between Bengali culture and the perceived “foreignness” of Islam were typical among those who were outsiders to the rural experience—whether they were members of Bengal’s premodern Muslim literati, European travelers in Bengal, or modern-day observers.

Nobody remembers God and the Prophet; The consciousness of many ages has passed. Nobody has transmitted this knowledge in the local language. From sorrow, I determined To talk more and more about the Prophet. It is my misfortune that I was born a Bengali. None of the Bengalis understand Arabic, And so not one has understood any of the discourse of his own religion.[29]

But the rural masses do not appear to have been troubled by such tensions, or even to have noticed them. For them, an easy identification of the exogenous with the indigenous—that is, the “Arabic” with the “Bengali”—had resulted from prolonged cultural contact, in the course of which Allah and the various superhuman agencies associated with him gradually seeped into local cosmologies. What the anthropologist Jack Goody has written of modern West Africa applies equally to premodern Bengal: “I know of no society in West Africa which does not make an automatic identification of their own High God with the Allah of the Muslims and the Jehovah of the Christians. The process is not a matter of conversion but of identification. Nevertheless, it prepares the ground for change, here as elsewhere.”[30] An excellent illustration of this is found in the earliest preaching of Christianity among the pagan Greeks. Addressing the council of Athens in the first Christian century, the apostle Paul declared:

Instead of demanding outright rejection of the Athenian pantheon, Paul not only complimented the Greeks on their religious scruples but identified the Christian deity with an indigenous one, thereby making a transition from the “old” to the “new” both possible and acceptable.[32]Men of Athens, I have seen for myself how extremely scrupulous you are in all religious matters, because I noticed, as I strolled round admiring your sacred monuments, that you had an altar inscribed: To an Unknown God. Well, the God whom I proclaim is in fact the one whom you already worship without knowing it.[31]

We see an instance of identification in premodern Bengal in the history of the cult of the legendary holy man Satya Pir. Over a hundred manuscript works concerning this cult have been identified, most of them dating from the eighteenth century, with the earliest of them dating to the sixteenth century.[33] The emergence of the cult thus coincided chronologically with the growth of agrarian communities focused on the tiny thatched mosques and shrines that proliferated throughout rural East Bengal in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The early literature written in praise of Satya Pir portrays a folk society innocent of hardened communal boundaries, and one that freely assimilated a variety of beliefs and practices that were “in the air” in Bengal’s premodern religious environment. A text devoted to the cult composed by the poet Sankaracharya in 1664 identifies Satya Pir as the son of one of Sultan ‘Ala al-Din Husain Shah’s daughters, and hence a Muslim. Another version, composed by Krishnahari Das, begins with invocations to Allah and stories of the Prophet. Yet the same text portrays Satya Pir as born of the goddess Chandbibi and as having come into the world to redress all human ills in the Kali Yuga, the last and lowest Hindu epoch preceding a period of restored justice and harmony. Other texts explicitly identify this Satya Pir with the divinity Satya Narayan, understood as a form of the Brahmanic god Vishnu.[34]

Some scholars have understood the Satya Pir cult, and indeed Bengali folk religion generally, in terms of a synthesis of Islam and Hinduism.[35] But such thinking simply projects back into the premodern period notions of religion that became widespread in the colonial nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and that postulated the more or less timeless existence of two separate and self-contained communities in Bengal, adhering to two separate and self-contained religious systems, “Hinduism” and “Islam.” Reinforcing this understanding was the objective polarization of colonial Bengali society into politically conscious groups drawn along communal lines. Thus it was at this time that Muslims ceased worshiping Satya Pir, while Satya Narayan became identified as an exclusively Hindu deity worshiped only by Hindus.[36] In reality, though, such polarized religious communities had evolved out of a time when religious identities at the folk level were far less self-conscious and religious systems were far more open-ended than in modern times.

It is not only during or since colonial times, however, that people have held to a polarized image of premodern Bengali religious culture. Even contemporary Europeans saw Bengali society through binary lenses. “Mahometans as well as Gentiles,” wrote the French traveler François Pyrard in early 1607, “deem the water [of the Ganges River] to be blessed, and to wash away all offences, just as we regard confession.”[37] Here the author’s reference point is not twentieth-century Bengal, riven by its communal loyalties, but seventeenth-century Catholic Europe, riven by its communal loyalties. Considering France’s long history of confrontational relations with nearby Arab Islam, Pyrard doubtless presumed a clear understanding of what constituted a “Mahometan,” and respect for the sanctity of the Ganges River would certainly not have been included in that understanding. Imagining deltaic society to have been sharply divided into two mutually exclusive socioreligious communities, the Frenchman was naturally struck by the spectacle of “Muslims” participating in a “Hindu” rite.

To understand premodern Bengali society on its own terms requires suspending the binary categories typical of modern observers such as D. C. Sen,[38] of contemporary outsiders such as François Pyrard, and of members of the contemporary Muslim elite such as Saiyid Sultan, all of whom were informed by normative understandings of Islam. Instead of visualizing two separate and self-contained social groups, Hindus and Muslims, participating in rites in which each stepped beyond its “natural” communal boundaries, one may see instead a single undifferentiated mass of Bengali villagers who, in their ongoing struggle with life’s usual tribulations, unsystematically picked and chose from an array of reputed instruments—a holy man here, a holy river there—in order to tap superhuman power. What Dusan Zbavitel has written of the ballads of premodern Mymensingh—that they were “neither products of Hindu or Muslim culture, but of a single Bengali folk-culture”[39]—may be justly said of premodern Bengali folk religion generally.

| • | • | • |

Displacement

A third dimension of the Islamization process—the displacement of Bengali superhuman agencies from the local cosmology and their replacement by Islamic ones—is clearly visible in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when waves of Islamic reform movements such as the Fara’izi and the Tariqah-i Muhammadiyah swept over the Bengali countryside. These movements aimed to strip from Bengali Islam all the indigenous beliefs and practices to which folk communities had been accommodated, and to instill among them an exclusive commitment to Allah and the Prophet Muhammad.

The most influential nineteenth-century reform movement, the Fara-‘idi, had been launched by Haji Shariat Allah (d. 1840), a man of humble rural origins who in 1799 made a pilgrimage to Mecca when only eighteen years of age. He then passed nineteen years in religious study in Islam’s holiest city at a time when Arabia itself had fallen under the spell of a zealous reform movement, Wahhabism. Returning to Bengal in 1818, the ḥājī found that customs that had seemed natural to him before his pilgrimage now appeared as grotesque aberrations from Islam as practiced in Wahhabi Arabia. From 1818 until his death in 1840, he tirelessly applied himself to reforming his Bengali co-religionists. In time, he passed into legend as an almost super-historical figure, a savior of Islam in Bengal,[40] whose deeds a local bard versified around 1903–6:

In 1894 James Wise characterized the nineteenth-century reform movement as one of “ignorant and simple peasants, who of late years have been casting off the Hindu tinsel which has so long disfigured their religion.”[42] But as the above poem shows, more was involved in Haji Shariat Allah’s movement than merely casting off “Hindu tinsel.” References to the ḥājī’s efforts to abolish the fātiḥa and the “worship of shrines,” and to inhibit the influence of “corrupt” mullās, point to an attempt to eliminate the very instruments and institutions by which Islam had originally taken root in the delta. Without the shrines whose establishment had been authorized by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century provincial Mughal officials, there would have been no institutional basis for mullās and other members of the religious gentry to establish the fātiḥa—that is, readings from the Qur’an—in the newly created settlements of the eastern delta’s expanding rice frontier.

Where had you been When Haji Shariat Allah came thither (to Bengal)? Who did abolish the custom of Fatihah, The worship of shrines, and stop the corrupt Mullah? When he set his foot in Bengal All shirk (polytheism) and bid‘at (sinful innovation) were

trampled down.All these bid‘at were then abolished And the sun of Islam rose high in the sky.[41]

Under the influence of the teachings of another Muslim reformist, Karamat ‘Ali (d. 1874), boatmen of Noakhali District who had hitherto been addressing their prayers to the saint Badar and to Panch Pir (the “five pīrs”), were soon addressing their prayers to Allah alone.[43] Such activity on the divine level was paralleled by similar activity at the human level. Bengalis whose identity as Muslims had not previously been expressed in exclusivist terms now began adopting Arabic surnames, a sure sign of a deepening attachment to Islamic ideals. For example, the district gazetteer for Noakhali, published in 1911, notes that the “vast majority of the Shekhs and lower sections of the community are descended from the aboriginal races of the district,” and that Muslims “with surnames of Chand, Pal, and Dutt are to be found in the district to this day.”[44] But by 1956 it was observed that among Muslims of that district such names had practically disappeared and, owing to “the influence of reforming priests,” had been replaced by Arabic surnames.[45]

There is, then, no denying that in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Bengali Muslims became increasingly aware of the beliefs and practices then current in the Arab heartland, and that they attempted to integrate those beliefs and practices into their identity as Muslims.[46] The factors contributing to this sense of awareness are well known: the assault on Islam mounted by Christian missionaries in India, the spread of reformist literature facilitated by print technology, political competition between Muslim and non-Muslim communities in the context of colonial rule, steamship technology, and a quickened incidence of pilgrimage to Arabia. As the ethnographer H. H. Risley wrote in 1891: “Even the distant Mecca has been brought, by means of Mesrs. Cook’s steamers and return-tickets, within reach of the faithful in India; and the influence of Mahomedan missionaries and return pilgrims has made itself felt in a quiet but steady revival of orthodox usage in Eastern Bengal.”[47]

It would be wrong, however, to think of movements to purify local cosmologies as phenomena confined to the nineteenth or twentieth centuries, or as functions of, or responses to, the advent of “modernism.”[48] Both in the original rise of Islam in Arabia and in the subsequent growth of Islam in premodern Bengal, one finds movements comparable both socially and theologically to those of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In all three instances—in early Arabia, in premodern Bengal, and in modern Bengal—lesser superhuman agencies came to be absorbed under or into the sovereignty of a single deity, a dynamic process Max Weber called “religious rationalization.”[49]

The first of these, the rise of Islam in Arabia, established the model for the subsequent movements in Bengal, as in the Muslim world at large. Sources dating from the second through the seventh centuries reveal the gradual evolution of a monotheistic cult, heavily influenced by Jewish practice and Jewish apocalyptic thought, that in the time of Muhammad (d. 632) succeeded in absorbing neighboring pagan cults in the Arabian peninsula. As early as the second Christian century, a Nabataean inscription identified Allah as the patron deity of an Arab tribe in northwestern Arabia.[50] By the fifth century, two centuries before Muhammad, a Greek source reports Arab communities in northern Arabia practicing a religion that, although corrupted by the influence of their pagan neighbors, resembled the religion of the Hebrews up to the days of Moses. They practiced circumcision like the Jews, refrained from eating pork, and observed “many other Jewish rites and customs.” The source adds that these Arabs had come into contact with Jews, from whom they learned of their descent from Abraham through Ishmael and Hagar.[51] The earliest known biography of Muhammad, found in an Armenian chronicle dating from the 660s, describes the Arabian prophet as a merchant who restored the religion of Abraham among his people and led his believers into Palestine in order to recover the land God had promised them as descendants of Abraham.[52]

Between the second and seventh centuries, then, Allah had grown from the patron deity of a second-century Arab tribe to, in Muhammad’s day, the high God of all Arabs, as well as the God of Abraham. This evolutionary process is also visible in the Qur’an. Before Muhammad’s mission, the tribes of western Arabia were already paying increasing attention to Allah at the expense of lesser divinities or tribal deities. By the time Muhammad began to preach, Allah had become identified as the “Lord of the Ka‘aba” (Qur’an 106:3), and hence the chief god of the pagan deities whose images were housed in the Meccan shrine. In some Qur’anic passages the existence of lesser divinities and angels was also affirmed, although their effectiveness as intercessors with Allah was denied.[53] In others, however, Arab deities other than Allah were specifically dismissed as nothing “but names which ye have named, ye and your fathers, for which Allah hath revealed no warrant.”[54] This latter passage indicates the triumph of the monotheistic ideal, the end point of an evolutionary process in which divinities other than Allah were not merely dismissed as ineffectual but denied altogether.

Such a process of religious rationalization was repeated in premodern Bengal, as seen especially in the Nabī-Baṃśa, the ambitious literary effort of Saiyid Sultan. This poet and local Sufi of the Chittagong region flourished toward the end of the sixteenth century, a time when the forested hinterland of the southeastern delta was only beginning to be touched by plow agriculture and intense exposure to the Qur’an. Characterized as a “national religious epic” for Bengali Muslims,[55] the Nabī-Baṃśa is epic not only in its size—the work contains over twenty-two thousand rhymed couplets—but also in one of its principal aims: to treat the major deities of the Hindu pantheon, including Brahma, Vishnu, śiva, Rama, and Krishna, as successive prophets of God, followed in turn by Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad.

In this respect we may compare Saiyid Sultan’s overall endeavor with that of the mid-eighth-century Arab writer Ibn Ishaq (d. ca. 767), author of the earliest Islamic biography of the Prophet Muhammad. Both men aimed at writing a universal history that began with Creation and continued through the life of the Prophet Muhammad. To this end both divided their works into two large sections: a first part detailing the lives of all the prophets preceding Muhammad—which in Ibn Ishaq’s work was entitled the Kitāb al-Mubtada’, “Book of Beginnings”—and a second part devoted exclusively to the Prophet Muhammad. This organization gave both works a powerful teleological trajectory. “By including all the world’s history,” writes the historian Gordon Newby, Ibn Ishaq’s Kitāb al-Mubtada’ “demonstrated that time’s course led to Islam, which embraced the prophets and holy men of Judaism and Christianity, and finally produced the regime of the Abbasids, whose empire embraced Muslims, Christians, and Jews.” Moreover, as a commentary on both the Bible and the Qur’an, the Kitāb al-Mubtada’ “fosters the Muslim claim that Islam is the heir to Judaism and Christianity.”[56] In like fashion, the Nabī-Baṃśa, by commenting extensively on Vedic, Vaishnava, and śaiva divinities, in addition to biblical figures, fostered the claim that Islam was the heir, not only to Judaism and Christianity, but also to the religious traditions of pre-Muslim Bengal.

The structural similarity between the Kitāb al-Mubtada’ and the Nabī-Baṃśa arises from the similar historical circumstances in which the two works emerged. Both authors lived in frontier situations where religious and social boundaries were very much in flux and where Islam, though politically dominant, was new and demographically dwarfed by a majority of adherents to much older creeds. In both cases, moreover, the religious and social identity of the Muslim community had not yet fully crystallized and was still very much in the process of formation. Such “frontier” circumstances fostered a climate conducive to literary creativity,[57] as both Ibn Ishaq and Saiyid Sultan felt it necessary to define the cultural identity of their own communities in relation to larger, non-Muslim societies. Both endeavored to specify the historical and cosmic roles played by prophets who had preceded and foreshadowed the prophetic career of Muhammad. Such a strategy not only established vital connections between the larger community and their own but, more important, asserted their own claims to primacy over the majority communities.

Ibn Ishaq wrote the bulk of his Kitāb al-Mubtada’ in Baghdad during the 760s. Located near the capital of the former Sasanian Persian dynasty, far to the north of what was then the Islamic heartland—Mecca and Medina in western Arabia—Baghdad in Ibn Ishaq’s day was still in a cultural frontier zone, where a good deal of interaction between Muslims and non-Muslims could and did take place. At that time Muslims comprised less than 10 percent of the population of Iraq and Iran, the remainder being mainly Christian, Jewish, or Zoroastrian.[58] Since many figures from the Christian and Jewish scriptures also appear in the Qur’an, early Muslim scholars like Ibn Ishaq, desiring to form a fuller understanding of the Islamic revelation, took pains to collect lore concerning such biblical figures from representatives of the Jewish and Christian communities.[59] These extra-Islamic materials were then fitted into an evolving conception of community, history, and prophethood that linked the new Muslim community to the older communities, while at the same time distinguishing the new from the older communities.

Thus by the eighth century the most creative forces that served to forge an Islamic cultural identity were no longer to be found in Islam’s original centers of Mecca and Medina, which had already become cities of shrines and reliquaries. Rather, the new religion’s most creative energies had by then passed to the north, where Arab Muslims encountered, and had to come to terms with, much older civilizations. But Baghdad would not for long remain a frontier society. Ibn Ishaq happened to live there during the culturally formative and doctrinally fluid moment just before Abbasid power was consolidated, before the schools of Islamic Law had crystallized, and before Baghdad itself had passed from a frontier town to a sprawling metropolis at the hub of a vital and expanding Islamic civilization. At this point, when most of Iraq, Syria, and Iran converted to Islam, concern with pre-Islamic history slackened, and the part of Ibn Ishaq’s work dealing with pre-Islamic prophets, the Kitāb al-Mubtada’, fell into disrepute, soon to disappear altogether from circulation.[60]

Although separated from the Kitāb al-Mubtada’ by eight hundred years, Saiyid Sultan’s Nabī-Baṃśa appeared during a similar phase in the evolution of a Muslim community’s socioreligious self-consciousness. Hence we find in it a similar tendency simultaneously to associate Islam with earlier traditions and to dissociate it from them. Saiyid Sultan not only identified the God of Adam with the Sanskrit names Prabhu and Niraṇjan; he also identified the Islamic notion of a prophet (nabī), or a messenger sent down by God, with the Indian notion of an avatār, or an incarnation of a deity.[61] The poet lays out these ideas at the very beginning of the epic. “As the butter is hidden in the milk,” he wrote, drawing on the rich imagery of India’s Puranic literature, “that is how Prabhu was co-existent with the Universe. He manifested himself in the shape of Muhammad, as his avatār.”[62] The author also juxtaposed Indian with Sufi notions of divine activity. After expressing the Vaishnava sentiment that Krishna had been created “in order to manifest love (keli) at Vrindavan,” the poet expressed the Sufi sentiments that God (“Niraṇjan”) used to enjoy his own self by gazing at his reflected image in a mirror, and that before creating the sky and the angels he had created the “Light of Muhammad” (Nūr-i Muḥammad).[63] Saiyid Sultan even understood the four Vedas as successive revelations sent down by God (“Niraṇjan,” “Kartār”), each one given to a different “great person” (mahājan). Accordingly, Brahmans had been created in order to teach about Niraṇjan and to explain the Vedas to the people.[64] Rather than repudiating Bengal’s older religious and social worlds, then, the epic served to connect Islam with Bengal’s socioreligious past, or at least with that part of it represented in the high textual tradition of the Brahmans.

Indeed, the book’s very title—Nabī-Baṃśa means “the family of the Prophet”—points to the author’s overall effort to situate Muhammad within a wider “family” of Bengali deities and Hebrew prophets. Like family members pitching in to solve domestic problems, Islamic figures in the Nabī-Baṃśa occasionally appear for the purpose of resolving specifically Indian dilemmas or problematic outcomes. Even before creating man, wrote the poet, Niraṇjan created a prophet (nabī) to preach to the angels and demons because they had become forgetful of dharma, or “duty” as understood in classical Indian thought.[65] And Adam himself was created from the soil of the earth goddess Kṣiti, mother of Sita, as a device for resolving the problematic conclusion of the popular epic Rāmāyaṇa. Upon hearing Kṣiti’s complaints concerning the shame suffered by her daughter Sita, whom people had falsely blamed for infidelity to Rama, Niraṇjan told the angels, “By means of Adam I will nurture Kṣiti; I will create Adam from the soil (mātī) of Kṣiti.”[66]

But it would be wrong to consider the Nabī-Baṃśa a basically “Hindu” epic with a few important Islamic personages and terms simply added to it, or as a “syncretic” work that merely identifies foreign deities with local deities. For on fundamental points of theology, the poet clearly drew on Judeo-Islamic and not on Indic thought. For example, his contention that each nabī/avatār of God (i.e., “Niraṇjan”) had been given a scripture appropriate for his time, departed from the Indian conception of repeated incarnations of the divine and affirmed instead the Judeo-Islamic “once-only” conception of prophethood. Moreover, the epic did not subscribe to a view of cosmic history as oscillating between ages of splendor and ages of ruin in the cyclical manner characteristic of classical Indian thought. Rather, according to Saiyid Sultan, as religion in the time of each nabī/avatār became corrupt, God sent down later prophets with a view to propagating belief in one god, culminating in the last and most perfect nabī/avatār, Muhammad. Already in the four Vedas, the poet states, God (“Kartār”) had given witness to the certain coming of Muhammad’s prophetic mission.[67]

The epic thus presents a linear conception of religious time that is not at all cyclical, but moves forward toward God’s final prophetic intervention in human affairs. It thus fully accords with the Qur’anic understanding of prophecy and of God’s role in human history. It is, of course, true that the poet identifies Allah with Niraṇjan, and nabī with avatār. But the Prophet Muhammad is seen as standing at the end of a long chain of Middle Eastern prophets and Indian divinities, with whom he is in no way confused or identified. By proclaiming the finality and superiority of Muhammad’s prophetic mission, then, Saiyid Sultan’s work provides the rationale for displacing all other nabī/avatārs from Bengal’s religious atmosphere. In this respect, Saiyid Sultan departed from the tradition of previous Bengali poets, who were content with merely including Allah in Bengali cosmologies, or with identifying Allah with deities in those cosmologies.

In fact, the poet explains the whole Hindu socioreligious order as it existed in his own day as the work of the fallen Islamic angel Iblis, or Satan. “The descendants of Cain,” he wrote, “indulged in worshiping idols (murti) in the shape of men, birds and pigs—all taught them by Iblis.”[68] And it was Iblis who, on discovering the Vedas, had deliberately created an alternative, corrupted text, which the Brahmans unwittingly propagated among the people.[69] On this basis, Brahmans were said to have misguidedly taught people, for example, to cremate their dead instead of returning them to the ground from which man was created.[70] And it was from such corrupted scriptures that Brahmans got the idea of wearing unstitched clothing (i.e, the dhoti) instead of stitched clothing.[71] For the use of stitched clothing had been taught by “Shish” (Seth in Genesis), the son of Adam and Eve after Abel’s death, from whom were descended the righteous people of the earth, the Muslims.[72]

In short, far from describing Islamic superhuman agencies in Indian terms, the Nabī-Baṃśa does just the opposite: while Brahmans are portrayed as the unwitting teachers of a body of texts deliberately corrupted by Iblis, the rest of the Hindu social order is portrayed as descended from Cain, the misguided son of Adam and Eve. It was only from Adam and Eve’s other son, Shish, that a “rightly guided” community, the Muslim umma, would descend. The epic thus reflects a level of consciousness that had come to understand Islam as more than just another name for an already dense religious cosmology, and “Allah” as more than just another name for a familiar divinity. Rather, Saiyid Sultan, like the early Arab writer Ibn Ishaq, understood the advent of Islam as the inevitable result of a unique cosmic and historical process.

| • | • | • |

Literacy and Islamization

Although the growth of Islam in Bengal witnessed no neat or uniform progression from inclusion to identification to displacement, one does see, at least in the eastern delta, a general drive toward the eventual displacement of local divinities. In part, one can explain this in terms of Bengal’s integration, since the late sixteenth century, into a pan-Indian, and indeed, a global civilization. Akbar’s 1574 conquest of the northwestern delta established a pattern by which the whole delta would be politically and economically integrated with North India. What was unique about the east, however, was that prior to the late sixteenth century, its hinterland had remained relatively undeveloped and isolated as compared with the west; hence the expansion of Mughal power there was accompanied by the establishment of new agrarian communities and not simply the integration of old ones. Composed partly of outsiders—emigrants from West Bengal or even North India—and partly of newly peasantized indigenous communities of former fishermen or shifting cultivators, these communities typically coalesced around the many rural mosques, shrines, or Qur’an schools built by enterprising pioneers who had contracted with the government to transform tracts of virgin jungle into fields of cultivated paddy.

It was mainly in the east, moreover, that political incorporation was accompanied by the intrusion and eventual primacy of Islamic superhuman agencies in local cosmologies. Contributing to this was the very nature of Islamic religious authority, which does not flow from priests, magicians, or other mortal agents, but from a medium that is ultimately immortal and unchallengeable—written scripture. The connection between literacy and divine power in Islam is perfectly explicit.[73] Moreover, well before their rise to prominence in Bengal, Muslims had already constructed a great world civilization around the Qur’an and the vast corpus of literature making up Islamic Law. It is therefore not coincidental that Muslims have described theirs as the “religion of the Book.”

It is true, of course, that the Hindu tradition is also scripturally based. As living repositories of Vedic learning, or at least of traditions that derive legitimacy from that learning, Brahmans “represent” scriptural authority in a way roughly analogous to the way Muslim men of piety mediate, and thus “represent,” the Qur’an. By the time of the Turkish conquest, a scripturally based religious culture under Brahman leadership had already become well entrenched in the dense and socially stratified society of the western delta. In this context, the intrusion of another scripturally defined religious culture, Islam, failed to have a significant impact. But the coherence of the Brahmanic socioreligious order progressively diminished as one moved from west to east across the delta, rendering the preliterate masses of the east without an authority structure sufficient to withstand that of Islam. Among these peoples the rustic shrines, mosques, and Qur’an schools that we have been examining introduced a type of religious authority that was fundamentally new and of greater power relative to what had been there previously. “In non-literate societies,” writes J. D.Y. Peel, a scholar of religious change in modern West Africa,

the past is perceived as entirely servant of the needs of the present, things are forgotten and myth is constructed to justify contemporary arrangements; there are no dictionary definitions of words.…In religion there is no sense of impersonal or universal orthodoxy of doctrine; legitimate belief is as a particular priest or elder expounds it. But where the essence of religion is the Word of God, where all arguments are resolved by an appeal to an unchangeable written authority, where those who formulate new beliefs at a time of crisis commit themselves by writing and publishing pamphlets…religion acquires a rigid basis. “Structural amnesia” is hardly possible; what was thought in the past commits men to particular courses of action in the present; religion comes to be thought of as a system of rules, emanating from an absolute and universal God, which are quite external to the thinker, and to which he must conform and bend himself, if he would be saved.[74]

In eastern Bengal, where Brahmans were thinly scattered, the analog to Peel’s “particular priest or elder” was typically a local ritualist who was neither literate nor a Brahman. True, the mosque builders, rural mullās, or charismatic pīrs who fanned out over the eastern plains may also have been illiterate; moreover, the basis of their authority, like that of indigenous non-Muslim ritualists, was often charismatic in nature. But what is important is that these same men patronized Qur’an readers and “readers of fātiḥa,” who, even if themselves only semi-literate in Arabic, were seen as representing the authority of the written word as opposed to the ad hoc, localized, and transient authority of indigenous ritualists.[75] Therefore, with the introduction of Qur’an readers, Qur’an schools, and “readers of fātiḥa” into the delta, the relatively fluid and expansive cosmology of pre-Muslim eastern Bengal began to resolve into one favoring the primacy of Allah and the Prophet Muhammad. As Peel puts it, religion began to acquire “a rigid basis.”

Further facilitating the growth of this “religion of the Book” in Bengal was the diffusion of paper and of papermaking technology. Introduced from Central Asia into North India in the thirteenth century by Persianized Turks, by the fifteenth century the technology of paper production had found its way into Bengal, where it eventually replaced the palm leaf.[76] Already in 1432, the Chinese visitor Ma Huan remarked that the Bengalis’ “paper is white; it is made out of the bark of a tree, and is as smooth and glossy as deer’s skin.”[77] And by the close of the sixteenth century the poet Mukundaram noted the presence of whole communities of Muslim papermakers (kāgajī) in Bengali cities.[78] The revolutionary impact that the technology of literacy made on premodern Bengali society is suggested in the ordinary Bengali words for paper (kāgaj) and pen (kalam), both of which are corrupted loan words from Perso-Arabic. It is also significant that on Bengal’s expanding agrarian frontier, the introduction of papermaking technology coincided with the rise of a Muslim religious gentry whose authority structure was ultimately based on the written word—scripture. While it would be the crudest technological determinism to say that the diffusion of paper production simply caused the growth of Islam in Bengal or elsewhere, it is certainly true that this more efficient technology of knowledge led to more books, which in turn promoted a greater familiarity with at least the idea of literacy, and that this greater familiarity led, in turn, to the association of the written word with religious authority.

Serving to check the growth of the “religion of the Book,” however, was the fact that the book in question, the Qur’an, was written in a language unknown to the masses of Bengali society. Moreover, since the Qur’an had been revealed in Arabic, in Bengal as elsewhere fear of tampering with the word of God inhibited its outright translation. As we have seen, Bengali Muslims were extremely reluctant to translate even Islamic popular lore into Bengali. Of course, they could have done what many other non-Arab Muslims did—that is, retain their own language for written discourse but render it in the Arabic script, as happened in Iran (modern Persian) and North India (Urdu). The transliteration of any language into Arabic script not only facilitates the assimilation of Arabic vocabulary but fosters a psychological bond between non-Arab and Arab Muslims. In the seventeenth century, in fact, attempts were made to do the same for Bengali. The Dhaka Museum has a manuscript work composed in 1645 entitled Maqtul Husain—a tract treating the death of Husain at Karbala—written in Bengali but using the Arabic, and not the Bengali, script.[79] Although subsequent writers made similar such literary attempts,[80] it is significant that the effort never took hold, with the result that Bengali Muslims remain today the world’s largest body of Muslims who, despite Islamization, have retained both their language and their script.[81]

Since Islamic scripture was neither translated nor transliterated in premodern Bengal, it not surprisingly first entered mass culture in a magical, as opposed to liturgical, context. In Ksemananda’s Manasā-Maṅgala, a work composed in the mid seventeenth century, we hear that in the house of one of the poem’s Hindu figures (Laksmindhara, son of Chand), a copy of the Qur’an was kept along with other charms for the purpose of warding off evil influence.[82] From the remarks of Vijaya Gupta, a poet of East Bengal’s Barisal region, who wrote in 1494,[83] we find an even earlier reference to the same use of Muslim scripture. In this instance, the written word appeared not in a Hindu household but in the hands of a mullā. A group of seven weavers, evidently Muslims, since they resided in “Husainhati,” were bitten by snakes unleashed by the goddess Manasa and went to the court of the qāẓī seeking help. Wrote the poet:

Here we see a Muslim ritualist mediating on the people’s behalf with a class of ubiquitous spirits, bhūt, that pervaded (and still pervades) the folk Bengali cosmology.[85] Moreover, the mullā clearly used the scripture in a magical and not a liturgical context, for it was not by reading the holy book that he dealt with evil spirits but by having his clients wear written extracts from it around their necks—a usage that enjoyed the endorsement of the state-appointed Muslim judge, or qāẓī.[86] In modern times, too, one finds ritualists employing the magical power of the Qur’an for healing purposes in precisely the manner that mullās had done three centuries earlier. In 1898 an ojhā, a local shamanlike ritualist, was observed in a village in Sylhet District using Qur’anic passages in his treatment of persons possessed by bhūts.[87] And in recent years ojhās among the non-Muslim Chakma tribesmen of the Chittagong Hill Tracts have been integrating Muslim scripture and Islamic superhuman agencies into their healing rituals, indicating the continued penetration of Islamic religious culture beyond the delta and into the adjacent mountains.[88]There was a teacher of the Qāḍī named Khālās…who always engaged himself in the study of the Qur’an and other religious books.…He said, if you ask me, I say, why are you afraid of demons [bhūt], when you have got the religious books. Write (extracts) from the book and hang it down the neck. If then also the demons (implying snakes) bite, I shall be held responsible. The Qāḍī accepted what the Mullā said and all present took amulet[s] from him (the Mullā).[84]

On the other hand, European observers noted that Bengali mullās also used the Qur’an in purely liturgical, as opposed to magical, contexts. In 1833 Francis Buchanan observed that in rural Dinajpur, mullās “read, or repeat prayers or passages of the Koran at marriages, funerals, circumcisions, and sacrifices, for no Muslim will eat meat or fowl, over which prayers have not been repeated, before it has been killed.…According to the Kazis, many of these Mollas cannot read, and these only look at the book, while they repeat the passages.”[89] Although the mullās observed by Buchanan were themselves unable to read, they were nonetheless understood by their village clients to be tapping into a transcendent source of power, the written word, fundamentally greater and more permanent than those known to local ritualists. In the same way, it was reported in 1898 that Muslim villagers in Sylhet “employ Mullahs to read Koran Shariff and allow the merit thereof to be credited to the forefathers”[90]—an apparent reference to the same kind of fātiḥa rituals that sanads of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries had authorized for rural mosques and shrines.

All of this points to a progressive expansion in the countryside of the culture of literacy—that is, a tendency to confer authority on written religious texts and on persons associated with them (whether or not they could read those texts). This expanding culture of literacy naturally facilitated the growth of the cult of those superhuman agencies with which that culture was most clearly identified. In short, as the idea of “the book-as-authority” grew among ever-widening circles of East Bengal’s rural society—a development clearly traceable from the sixteenth century—so too did the “religion of the Book,” with its emphasis on the cosmological supremacy of Allah.

| • | • | • |

Gender and Islamization

The evolution of Islam in Bengal illustrates the complex relationship between economic base and ideological superstructure, a perennial issue amongst theorists of social change. It is evident that the incorporation of indigenous peoples of the eastern delta into an expanding peasant society paved the way for their gradual Islamization, and in this respect a changing economic base did indeed shape the resultant ideological superstructure, or Islam. Yet it is also true that the Islamic vision of the proper society as sustained by “the Book,” together with the corpus of Perso-Islamic popular lore that swept over premodern Bengal, served to pattern the subsequent evolution of Muslim culture in the delta. Nowhere is this more visible than in the changing status of women in Bengali Muslim communities.

In moral terms, the Qur’an, which refers repeatedly to “believing men,” “believing women,” and to “Muslim men and Muslim women,” places the two sexes in a position of absolute equality before God (Qur’an 33:35). But in social terms, women are subordinate to men. In the context of seventh-century Arabia, it is true, Qur’anic injunctions respecting women doubtless constituted a progressive force: the Qur’an emphasizes the just treatment of women, it prohibits female infanticide and the inheritance offemale slaves, and it provides legal protection for women in matters like inheritance or divorce. But women inherit only half of what men do, and they are generally understood as requiring male supervision, as indicated in the following Qur’anic verse:

Underlying the content of this passage is a structural hierarchy of authority connecting Allah, men, and women. Whereas God and men are grammatical subjects and actors, women are objects of action; indeed, much of the chapter entitled “Women” (Sura 4:1–43) consists of God’s instructions to men as to what they should do in respect to women.Men are in charge of women, because Allah hath made the one of them to excel the other, and because they spend of their property (for the support of women). So good women are the obedient, guarding in secret that which Allah hath guarded. As for those from whom ye fear rebellion, admonish them and banish them to beds apart, and scourge them. Then, if they obey you, seek not a way against them.[91]

These scriptural norms were gradually translated into social reality in most societies that became formally Islamic—including, eventually, in Bengal. They also seem to have merged with social practices current among non-Arab civilizations with which early Muslims came into contact. Thus, in the seventh century, when pastoral Arabs conquered the agrarian societies of Iraq and Syria, Muslim conquerors absorbed a wide spectrum of Greek and, especially, Iranian culture. This included what became known as the purdah system, or the seclusion of a woman from all men but her own—in private apartments at home, and behind a veil if she walked abroad—which had long been a mark of privilege in upper-class Byzantine and Sasanian society.[92] By the second half of the eighth century, the seclusion of women and the wearing of the veil had become official policy at the Abbasid court in Baghdad. Soon urban Muslims of all social classes followed the court’s example, with the result that by the fourteenth century, women had effectively disappeared from public life throughout the Arab Muslim world. But this was not yet the case beyond the Arab world, among Turkish, Indian, and West African peoples who had been only recently Islamized. Thus the great Arab traveler Ibn Battuta (d. 1377) expressed shock at seeing unveiled Muslim women in southern Anatolia, Central Asia, the Maldive Islands, and the western Sudan.[93] The Moroccan was especially astonished by the unrestrained social movement of Turkish women in Central Asia.[94]

In Bengal, both before and during the rise of Islam, outsiders made similar observations. In 1415, before Islam had become a force in the countryside, the Ming Chinese ambassador to Bengal noted with apparent reference to wet rice field operations that “men and women work in the fields or weave according to the season.”[95] Toward the end of the following century, around 1595, Abu’l-fazl recorded in his entry for Chittagong that “it is the custom when a chief holds a court, for the wives of the military to be present, the men themselves not attending to make their obeisance.” Referring to Bengal generally, he remarked that “men and women for the most part go naked wearing only a cloth (lungi) about the loins. The chief public transactions fall to the lot of the women.”[96] Although Muslim communities were just beginning to appear in the Bengal countryside when Abu’l-fazl wrote these lines, his remarks suggest that neither the veiling nor the seclusion of women had yet taken hold.

Still, the normative vision of a segregated society undeniably formed part of scriptural Islam, and pressure to realize that vision increased to the extent that Islamic literary authority sank roots in Bengali popular culture. The earliest reference to a normative gendered division of labor is found in a Bengali version of the story of Adam and Eve dating from the late sixteenth century. In Saiyid Sultan’s epic poem Nabī-Baṃśa, the angel Gabriel gives Adam a plow, a yoke, seed, and two bulls, advising him that “Niraṇjan has commanded that agriculture will be your destiny.”[97] Adam then planted the seed and harvested the crop. At the same time, Eve is given fire, with which she learns the art of cooking.[98] In short, a domestic life would be Eve’s destiny, just as Adam’s vocation would be farming.

By around 1700 the process of Islamization had proceeded to the point where romantic literature set in the Bengali countryside now included Muslim peasants as central characters. Yet the gendered division of labor and female seclusion, long entrenched in the Islamic heartlands, had still not appeared in the Bengali Muslim countryside. The Dewana Madina, a ballad composed by Mansur Baiyeoti around 1700 and set in the town of Baniyachong in southern Sylhet, tells of a Muslim peasant woman’s lament for her deceased husband. “Oh Allah,” she sobbed,

what is this that you have written in my forehead?…In the good month of November, favoured by the harvest-goddess, we both used to reap the autumnal paddy in a hurry lest it should be spoilt by flood or hail-storm. My dear husband used to bring home the paddy and I spread them in the sun. Then we both sat down to husk the rice.…In December when our fields would be covered with green crops, my duty was to keep watch over them with care. I used to fill his hooka with water and prepare tobacco;—with this in hand I lay waiting, looking towards the path, expecting him!…When my dear husband made the fields soft and muddy with water for transplanting of the new rice-plants, I used to cook rice and await his return home. When he busied himself in the fields for this purpose, I handed the green plants over to him for replanting.…In December the biting cold made us tremble in our limbs; my husband used to rise early at cock-crow and water the fields of shali crops. I carried fire to the fields and when the cold became unbearable, we both sat near the fire and warmed ourselves. We reaped the shali crops together in great haste and with great care. How happy we were when after the day’s work we retired to rest in our home.[99]

If one compares today’s Bengali Muslim society with that depicted in this early ballad, one sees how far the purdah system has become a reality. Whereas the ballad depicts men and women both reaping the rice paddy, spreading it for drying, and transplanting young seedlings, today only men perform these operations, while women’s work is confined to post-harvest operations—winnowing, soaking, parboiling, husking—all of which are done within the confines of the farmyard.[100] In the eastern delta the principal drive behind the domestication of female labor, according to recent studies, has been the popular association of proper Islamic behavior with the purdah system—that is, the very system of female seclusion that became normative in Muslim Arab societies from the eighth century on.[101] In the predominantly Hindu western delta, by contrast, rural women do participate in pre-harvest field operations.[102] Similarly, among jhūm cultivating populations of the Chittagong Hill Tracts to the immediate east of the delta, where Mughal administration, Muslim pioneers, and wet rice agriculture did not penetrate, women are also active in field operations—planting, weeding, harvesting, winnowing—and are in general socially unconstrained.[103]

This suggests that among communities that had become nominally Muslim from the sixteenth century on, there was a time lag between the appearance of a normative vision that separated male and female labor and the eventual realization of that vision. As with the increasing attention given to Islamic superhuman agencies, this seems to have resulted from the gradual diffusion of men or institutions associated with religious literacy—that is, the idea that the written word exerts a compelling authority over one’s everyday life.

| • | • | • |

Summary

In 1798 Francis Buchanan, an English explorer and servant of the East India Company, toured the hilly and forested interior of Chittagong District on official business, and incidentally made important observations about the religions of the peoples he encountered. Among the “Arakanese” peoples of the Sitakund mountains, for example, Buchanan noticed some worship of śiva.[104] In central Chakaria, he found forest-dwelling Muslims who made their living collecting oil, honey, and wax.[105] Further south, among the jhūm cultivators of Ukhia, he found a form of Buddhism that he said “differs a good deal from that of the orthodox Burma”: their priests were styled “pungres,” and their chief god was Maha Muni, worshiped in the form of a great copper image.[106] On the other hand, in the Cox’s Bazar region the Englishman was unable to find evidence of religious ideas of any sort. “They said they knew no god (Thakur) and that they never prayed to Maha Muni, Ram, nor Khooda”[107]—that is, deities associated respectively with the Buddhist, Hindu, and Muslim traditions. Clearly, by the end of the eighteenth century, scripturally legitimated religions had as yet gained only a tenuous foothold, if any at all, among the jhūm population ofBengal’s extreme eastern edge. Here Allah—or his Persian equivalent, Khudā —was only one among several high gods in current circulation.

Table 9. Religious Aspects of Islamization in Bengal

Like François Pyrard before him, Buchanan seems to have brought into Bengal’s interior an understanding of religions as static, closed, and mutually exclusive systems, each with its own community and its own superhuman beings. For Pyrard, these were “Mahometans” and “Gentiles”; for Buchanan, followers of “Maha-moony” (i.e., Buddhists), “Mohammedans,” and “Hindoos.” But what Pyrard and Buchanan encountered were systems of religious beliefs and practices that at the folk level were strikingly porous and fluid, bounded by no clear conceptual frontiers. In fact, it was precisely the fluidity of folk Bengali cosmology that allowed Bengalis to interact creatively with exogenous ideas and agencies, as is summarized in table 9. Both indigenous and the Islamic cosmologies comprised hierarchies of superhuman agencies that included at the upper end one or another high god (or goddess) presiding over a cosmos filled with lesser superhuman agencies. Allah was identified as the Islamic high god, followed by a host of lesser superhuman agencies, including the Prophet Muhammad at the upper end and various charismatic pīrs at the lower end. Initially, superhuman agencies identified with contemporary Perso-Islamic culture were simply included in local cosmologies alongside indigenous powers already there. In time, these became identified with those in the indigenous cosmology; still later, they were understood to have displaced the latter altogether.

As with that of any other exogenous agency, however, the advance of Islamic superhuman agencies in Bengali cosmologies was always inhibited by the perception that they were alien. To be widely accepted, a deity had to be perceived not only as powerful and efficacious but as genuinely local.[108] Thus the success of Islam in Bengal lay ultimately in the extent to which superhuman beings that had originated in Arab culture and subsequently appropriated (and been appropriated by) Hebrew, Greek, and Iranian civilizations, succeeded during the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries in appropriating (and being appropriated by) Bengali civilization. Initially, this involved the association or identification of Islamic with Bengali superhuman beings. But when figures like Adam, Eve, and Abraham became identified with central leitmotifs of Bengali history and civilization, Islam had become established as profoundly and authentically Bengali.

Notes

1. “Kanun Daimer Nathi,” Chittagong District Collectorate Record Room, No. 64, bundle 78, case no. 5027; No. 7, bundle 62, case no. 4005.

2. Fātiḥa-yi imāmīn-i aiyām-i ‘āshūrā. Ibid., No. 251, bundle 55, case no. 3568; No. 127, bundle 63, case no. 4049; No. 232, bundle 30, case no. 1935.

3. For example, in 1749 the Mughal government granted Shaikh Jan Allah of Satkania Thana 25.6 acres of jungle so that he might perform fātiḥa-yi darvīshī at a shrine entrusted to him. Ibid., No. 196, bundle 19, case no. 1093.

4. Muṣallīān-i fātiḥa, or fātiḥa-khwānī, as in ibid., No. 31, bundle 77, case no. 4971; No. 40, bundle 47, case no. 3054. “Qur’an readers” were titled Qur’ān-khwānī, or tilāwat, as in No. 65, bundle 73, case no. 4677; No. 72, bundle 63, case no. 4100; No. 113, bundle 35, case no. 2296.

5. Melford E. Spiro, “Religion: Problems of Definition and Explanation,” in Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion, ed. Michael Banton (London: Tavistock Publications, 1969), 96.

6. Bhattacharyya, “Tiger-Cult and Its Literature,” 49–56; Tarafdar, Husain Shahi Bengal, 17–18, 164–66, 233–35; P. K. Maity, Historical Studies in the Cult of the Goddess Manasā (Calcutta: Punthi Pustak, 1966), 182. See esp. Asim Roy, The Islamic Syncretistic Tradition in Bengal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983).

7. Bhattacharyya, “Tiger-Cult and Its Literature,” 49–50.

8. In parts of Bengal this sort of easy inclusion has persisted down to modern times. In 1956 it was noted that fishermen in the West Bengal Sundarban forests, before putting their nets to water, typically performed pūjā to the forest goddess Bon Bibi (literally, “forest goddess”) as a ritual intended to protect them from harm. For this purpose a small thatched and bamboo hut was constructed, in which was placed a clay image of Bon Bibi seated on a tiger. Flanking her on her right was an image of Daksin Ray, depicted as a strong, stout man standing with a sword. Behind him stood a bearded Muslim faqīr known as Ajmal, and in front of Daksin Ray lay the body and severed head of a young boy. Although the names and functions of the figures in the 1956 account differ from those of the seventeenth-century poem, the elements of both accounts—a tiger deity, a soldier, and a superhuman agent identified with Islam—have remained constant over the centuries, distinct from one another but included within a single religious cosmology. H. L. Sarkar, “Note on the Worship of the Deity Bon Bibi in the Sundarbans,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 22, no. 2 (1956): 211–12.