1. Before the Turkish Conquest

[The Sylhet region of East Bengal] was outside the pale of human habitation, where there is no distinction between natural and artificial, infested by wild animals and poisonous reptiles, and covered with forest out-growths.

| • | • | • |

Bengal in Prehistory

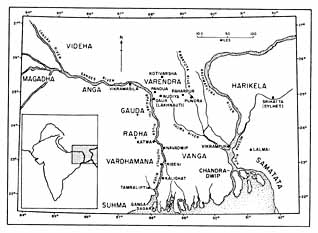

Physically, the Bengal delta is a flat, low-lying floodplain in the shape of a great horseshoe, its open part facing the Bay of Bengal to the south. Surrounding its rim to the west, north, and east are disconnected hill systems, out of which flow some of the largest rivers in southern Asia—the Ganges, the Brahmaputra, and the Meghna. Wending their way slowly over the delta’s flat midsection, these rivers and their tributaries deposit immense loads of sand and soil, which over millennia have gradually built up the delta’s land area, pushing its southern edge ever deeper into the bay. In historical times, the rivers have been natural arteries of communication and transportation, and they have defined Bengal’s physical and ancient cultural subregions—Varendra, the Bhagirathi-Hooghly basin, Vanga, Samatata, and Harikela (see map 1).[1]

Map 1. Cultural regions of early Bengal

The delta was no social vacuum when Turkish cavalrymen entered it in the thirteenth century. In fact, it had been inhabited long before the earliest appearance of dated inscriptions in the third century B.C. In ancient North Bengal, Pundra (or Pundranagara, “city of the Pundras”), identifiable with Mahasthan in today’s Bogra District, owed its name to a non-Aryan tribe mentioned in late Vedic literature.[2] Similarly, the Raḍha and Suhma peoples, described as wild and churlish tribes in Jain literature of the third century B.C.,[3] gave their names to western and southwestern Bengal respectively, as the Vanga peoples did to central and eastern Bengal.[4] Archaeological evidence confirms that already in the second millennium B.C., rice-cultivating communities inhabited West Bengal’s Burdwan District. By the eleventh century B.C., peoples in this area were living in systematically aligned houses, using elaborate human cemeteries, and making copper ornaments and fine black-and-red pottery. By the early part of the first millennium B.C., they had developed weapons made of iron, probably smelted locally alongside copper.[5] Rather than permanent field agriculture, which would come later, these peoples appear to have practiced shifting cultivation; having burned patches of forest, they prepared the soil with hoes, seeded dry rice and small millets by broadcast or with dibbling sticks, and harvested crops with stone blades, which have been found at excavated sites.[6] These communities could very well have been speakers of “Proto-Munda,” the Austroasiatic ancestor of the modern Munda languages, for there is linguistic evidence that at least as early as 1500 B.C., Proto-Munda speakers had evolved “a subsistence agriculture which produced or at least knew grain—in particular rice, two or three millets, and at least three legumes.”[7]

In the sixth and fifth centuries B.C., dramatic changes that would permanently alter Bengal’s cultural history took place to the immediate west of the delta, in the middle Gangetic Plain, where the practice of shifting cultivation gradually gave way to settled farming, first on unbunded permanent fields and later on bunded, irrigated fields. Moreover, whereas the earlier forms of rice production could have been managed by single families, the shift to wet rice production on permanent fields required substantial increases in labor inputs, the use of draft animals, some sort of irrigation technology, and an enhanced degree of communal cooperation.[8] As the middle Gangetic Plain receives over fifty inches of rainfall annually, over double that of the semi-arid Punjab,[9] the establishment of permanent rice-growing operations also required the clearing of the marshes and thick monsoon forests that had formerly covered the area. Iron axes, which began to appear there around 500 B.C., proved far more efficient than stone tools for this purpose.[10] Iron plowshares, which also began to appear in the middle Ganges region about this time, were a great improvement over wooden shares and vastly increased agricultural productivity in this region’s typically hard alluvial soil.[11] The adoption of the technique of transplanting rice seedings, a decisive step in the transition from primitive to advanced rice cultivation, also occurred in the middle Ganges zone around 500 B.C.[12]

| • | • | • |

Early Indo-Aryan Influence in Bengal

These changes were accompanied by the intrusion of immigrants from the north and west, the Indo-Aryans, who brought with them a vast corpus of Sanskrit sacred literature. Their migration into the Gangetic Plain is also associated with the appearance of new pottery styles. Both kinds of data show a gradual eastward shift in centers of Indo-Aryan cultural production: from the twelfth century B.C. their civilization flourished in the East Punjab and Haryana area (Kuru), from the tenth to the eighth centuries in the western U. P. area (Panchala), and from the seventh to the sixth centuries B.C. in the eastern U. P. and northern Bihar region (Videha).[13] Literature produced toward the end of this migratory process reveals a hierarchically ordered society headed by a hereditary priesthood, the Brahmans, and sustained by an ideology of ritual purity and pollution that conferred a pure status on Indo-Aryans while stigmatizing non-Aryans as impure “barbarians” (mleccha). This conceptual distinction gave rise to a moving cultural frontier between “clean” Indo-Aryans who hailed from points to the west, and “unclean” Mlecchas already inhabiting regions in the path of the Indo-Aryan advance. One sees this frontier reflected in a late Vedic text recording the eastward movement of an Indo-Aryan king and Agni, the Vedic god of fire. In this legend, Agni refuses to cross the Gandak River in Bihar since the areas to the east—eastern Bihar and Bengal—were considered ritually unfit for the performance of Vedic sacrifices.[14] Other texts even prescribe elaborate expiatory rites for the purification of Indo-Aryans who had visited these ritually polluted regions.[15]

Despite such taboos, however, Indo-Aryan groups gradually settled the upper, the middle, and finally the lower Ganges region, retroactively justifying each movement by pushing further eastward the frontier separating themselves from tribes they considered ritually unclean.[16] As this occurred, both Indo-Aryans and the indigenous communities with which they came into contact underwent considerable culture change.[17] For example, in the semi-arid Punjab the early Indo-Aryans had been organized into lineages led by patrilineal chiefs and had combined pastoralism with wheat and barley agriculture. Their descendants in the middle Ganges region were organized into kingdoms, however, and had adopted a sedentary life based on the cultivation of wet rice. Moreover, although the indigenous peoples of the middle and lower Ganges were regarded as unclean barbarians, Indo-Aryan immigrants merged with the agrarian society already established in these regions and vigorously took up the expansion of rice agriculture in what had formerly been forest or marshland. Thus the same Vedic text that gives an ideological explanation for why Videha (northern Bihar) had not previously been settled—that is, because the god Agni deemed it ritually unfit for sacrifices—also provides a material explanation for why it was deemed fit for settlement “now”: namely, that “formerly it had been too marshy and unfit for agriculture.”[18] The Indo-Aryans’ adoption of peasant agriculture is also seen in the assimilation into their vocabulary of non-Aryan words for agricultural implements, notably the term for “plow” (lāṅgala), which is Austroasiatic in origin.[19]

By 500 B.C. a broad ideological framework had evolved that served to integrate kin groups of the two cultures into a single, hierarchically structured social system.[20] In the course of their transition to sedentary life, the migrants also acquired a consciousness of private property and of political territory, onto which their earlier lineage identities were displaced. This, in turn, led to the appearance of state systems, together with monarchal government, coinage, a script, systems of revenue extraction, standing armies, and, emerging very rapidly between ca. 500 and 300 B.C., cities.[21] Initially, these sweeping developments led to several centuries of rivalry and warfare between the newly emerged kingdoms of the middle Gangetic region. Ultimately, they led to the appearance of India’s first empire, the Mauryan (321–181 B.C.).

All these developments proved momentous for Bengal. In the first place, since the Mauryas’ political base was located in Magadha, immediately west of the delta, Bengal lay on the cutting edge of the eastward advance of Indo-Aryan civilization. Thus the tribes of Bengal certainly encountered Indo-Aryan culture in the context of the growth of this empire, and probably during the several centuries of turmoil preceding the rise of the Mauryas. The same pottery associated with the diffusion of Indo-Aryan speakers throughout northern India between 500 and 200 B.C.—Northern Black Polished ware—now began to appear at various sites in the western Bengal delta.[22] It was in Mauryan times, too, that urban civilization first appeared in Bengal. Pundra (or Pundranagara), a city named after the powerful non-Aryan people inhabiting the delta’s northwestern quadrant, Varendra, became the capital of the Mauryas’ easternmost province. A limestone tablet inscribed in Aśokan Brahmi script, datable to the third century B.C., records an imperial edict ordering the governor of this region to distribute food grains to people afflicted by a famine.[23] This suggests that by this time the cultural ecology of at least the Varendra region had evolved from shifting cultivation with hoe and dibble stick to a higher-yielding peasant agriculture based on the use of the plow, draft animals, and transplanting techniques.

Contact between Indo-Aryan civilization and the delta region coincided not only with the rise of an imperial state but also with that of Buddhism, which from the third century B.C. to the seventh or eighth century A.D. experienced the most expansive and vital phase of its career in India. In contrast to the hierarchical vision of Brahmanism, with its pretensions to social exclusion and ritual purity, an egalitarian and universalist ethic permitted Buddhists to expand over great distances and establish wide, horizontal networks of trade among ethnically diverse peoples. This ethic also suited Buddhism to large, cross-cultural political systems, or empires. Aśoka (ca. 273–236 B.C.), India’s first great emperor and the third ruler of the Mauryan dynasty, established the religion as an imperial cult. Positive evidence of the advance of Buddhism in Bengal, however, is not found until the second century B.C., when the great stupa at Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh) included Bengalis in its lists of supporters. In the second or third century A.D., an inscription at Nagarjunakhonda (Andhra Pradesh) mentioned Bengal as an important Buddhist region,[24] and in A.D. 405–11, a visiting Chinese pilgrim counted twenty-two Buddhist monasteries in the city of Tamralipti (Tamluk) in southwestern Bengal, at that time eastern India’s principal seaport.[25]

Yet Buddhism in eastern India, as it evolved into an imperial cult patronized by traders and administrators, became detached from its roots in non-Aryan society. Rather than Buddhists, it was Brahman priests who, despite taboos about residing in “unclean” lands to the east, seized the initiative in settling amidst Bengal’s indigenous peoples from at least the fifth century A.D. on.[26] What perhaps made immigrant Brahmans acceptable to non-Aryan society was the agricultural knowledge they offered, since the technological and social conditions requisite for the transition to peasant agriculture, already established in Magadha, had not yet appeared in the delta prior to the Mauryan age.[27] All of this contributed to a long-term process—well under way in the fifth century A.D. but still far from complete by the thirteenth—by which indigenous communities of primitive cultivators became incorporated into a socially stratified agrarian society based on wet rice production.[28]

In the middle of the eighth century, large, regionally based imperial systems emerged in Bengal, some of them patronizing Buddhism, others a revitalized Brahmanism. The first and most durable of these was the powerful Pala Empire (ca. 750–1161), founded by a warrior and fervent Buddhist named Gopala. From their core region of Varendra and Magadha, the early kings of this dynasty extended their sway far up the Gangetic Plain, even reaching Kanauj under their greatest dynast, Dharmapala (775–812).[29] It was about this time, too, that a regional economy began to emerge in Bengal. In 851 the Arab geographer Ibn Khurdadhbih wrote that he had personally seen samples of the cotton textiles produced in Pala domains, which he praised for their unparalleled beauty and fineness.[30]

A century later another Arab geographer, Mas‘udi (d. 956), recorded the earliest-known notice of Muslims residing in Bengal.[31] Evidently long-distance traders involved in the overseas export of locally produced textiles, these were probably Arabs or Persians residing not in Pala domains but in Samatata, in the southeastern delta, then ruled by another Bengali Buddhist dynasty, the Chandras (ca. 825–1035). What makes this likely is that kings of this dynasty, although much inferior to the Palas in power, and never contenders for supremacy over all of India like their larger neighbors to the west, were linked with Indian Ocean commerce through their control of the delta’s most active seaports. Moreover, while the Palas used cowrie shells for settling commercial transactions,[32] the Chandras maintained a silver coinage that was more conducive for participation in international trade.[33]

Under the patronage of the Palas and various dynasties in Samatata, Buddhism received a tremendous lift in its international fortunes, expanding throughout maritime Asia as India’s imperial cult par excellence. Dharmapala himself patronized the construction of two monumental shrine-monastery complexes—Vikramaśila in eastern Bihar, and Paharpur in Bengal’s Rajshahi district[34]—and between the sixth and eleventh centuries, royal patrons in Samatata supported another one, the Salban Vihara at Lalmai.[35] As commercially expansive states rose in eastern India from the eighth century on, Buddhism as a state cult spread into neighboring lands—in particular to Tibet, Burma, Cambodia, and Java—where monumental Buddhist shrines appear to have been modeled on prototypes developed in Bengal and Bihar.[36] At the same time, Pala control over Magadha, the land of the historical Buddha, served to enhance that dynasty’s prestige as the supreme patrons of the Buddhist religion.[37]

Mas‘udi’s remark about Muslims residing in Pala domains is significant in the context of these commercially and politically expansive Buddhist states, for by the tenth century, when Bengali textiles were being absorbed into wider Indian Ocean commercial networks, two trade diasporas overlapped one another in the delta region. One, extending eastward from the Arabian Sea, was dominated by Muslim Arabs or Persians; the other, extending eastward from the Bay of Bengal, by Buddhist Bengalis.[38] The earliest presence of Islamic civilization in Bengal resulted from the overlapping of these two diasporas.

| • | • | • |

The Rise of Early Medieval Hindu Culture

Even while Indo-Buddhist civilization expanded and flourished overseas, however, Buddhist institutions were steadily declining in eastern India. Since Buddhists there had left life-cycle rites in the hands of Brahman priests, Buddhist monastic establishments, so central for the religion’s institutional survival, became disconnected from the laity and fatally dependent on court patronage for their support. To be sure, some Bengali dynasties continued to patronize Buddhist institutions almost to the time of the Muslim conquest. But from as early as the seventh century, Brahmanism, already the more vital tradition at the popular level, enjoyed increasing court patronage at the expense of Buddhist institutions.[39] By the eleventh century even the Palas, earlier such enthusiastic patrons of Buddhism, had begun favoring the cults of two gods that had emerged as the most important in the newly reformed Brahmanical religion—Śiva and Vishnu.[40]

These trends are seen most clearly in the later Bengali dynasties—the Varmans (ca. 1075–1150) and especially the Senas (ca. 1097–1223), who dominated all of Bengal at the time of the Muslim conquest. The kings of the Sena dynasty were descended from a warrior caste that had migrated in the eleventh century from South India (Karnataka) to the Bhagirathi-Hooghly region, where they took up service under the Palas. As Pala power declined, eventually evaporating early in the twelfth century, the Senas first declared their independence from their former overlords, then consolidated their base in the Bhagirathi-Hooghly area, and finally moved into the eastern hinterland, where they dislodged the Varmans from their capital at Vikrampur. Moreover, since the Senas had brought from the south a fierce devotion to Hindu culture (especially Śaivism), their victorious arms were accompanied everywhere in Bengal by the establishment of royally sponsored Hindu cults.[41] As a result, by the end of the eleventh century, the epicenter of civilization and power in eastern India had shifted from Bihar to Bengal, while royal patronage had shifted from a primarily Buddhist to a primarily Hindu orientation. These shifts are especially evident in the artistic record of the period.[42]

Behind these political developments worked deeper religious changes, occurring throughout India, that served to structure the Hindu religion as it evolved in medieval times and to distinguish it from its Vedic and Brahmanical antecedents. As Ronald Inden has argued, the ancient Vedic sacrificial cult (ca. 1000–ca. 300 B.C.) experienced two major historical transformations.[43] The first occurred in the third century B.C., when the Mauryan emperor Aśoka established Buddhism as his imperial religion. At that time the Vedic sacrifice, which was perceived by Buddhists as violent and selfish, was replaced by gift-giving (dāna) in the form either of offerings to Buddhist monks by the laity or of gifts of land bestowed on Buddhist institutions by Buddhist rulers. In response to these developments, Brahman priests began reorienting their own professional activities from performing bloody animal sacrifices to conducting domestic life-cycle rites for non-Brahman householders. At the same time, they too became recipients of gifts in the form of land donated by householders or local elites, as began occurring in Bengal from the fifth century A.D. This first transformation of the Vedic sacrifice did not, however, cause a rupture between Buddhism and Brahmanism. In fact, the two religions coexisted quite comfortably, the former operating at the imperial center, the latter at the regional periphery.[44]

The second transformation of the Vedic sacrifice occurred in the seventh and eighth centuries, when chieftains and rulers began building separate shrines for the images of deities. The regenerative cosmic sacrifice of Vedic religion, which Buddhists had already transformed into rites of gift-giving to monks, was now transformed into a new ceremony, that of the “Great Gift” (mahādāna), which consisted of a king’s honoring a patron god by installing an image of him in a monumental temple. These ideas crystallized toward the end of the eighth century, when, except for the Buddhist Palas, the major dynasties vying for supremacy over all of India—the Pratiharas of the north, the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan, and the Pandyas and Pallavas of the south—all established centralized state cults focusing on Hindu image worship. Instead of worshiping Vedic gods in a general or collective sense, each dynasty now patronized a single deity (usually Vishnu or śiva), understood as that dynasty’s cosmic overlord, whose earthly representative was the gift-giving king. These conceptions were physically expressed in monumental and elaborately carved temples that, like Buddhist stupas, were conceptually descended from the Vedic sacrificial fire altar.[45] Brahmans, meanwhile, evolved into something much grander than domestic priests who merely tended to the life-cycle rituals of their non-Brahman patrons. Now, in addition to performing such services, they became integrated into the ritual life of Hindu courts, where they officiated at the kings’ “Great Gift” and other state rituals.

Copper-plate inscriptions issued from the tenth through the twelfth centuries show how these ideas penetrated the courts of Bengal. Detailed lists of state officers found in inscriptions of the major dynasties of the post-tenth-century period—Pala, Chandra, Varman, and Sena—all show an elaboration of centralized state systems, increasing social stratification, and bureaucratic specialization.[46] Moreover, donations in land became at this time a purely royal prerogative, while the donations themselves (at least those in the northern and western delta) consisted of plots of agricultural land whose monetary yields were known and specified, indicating a rather thorough peasantization of society. And, except in the case of Samatata, recipients of these grants were Brahmans who received land not only for performing domestic rituals, as had been the case in earlier periods, but for performing courtly rituals.[47] Indeed, the granting of land to Brahmans who officiated at court rituals had become a kingly duty, a necessary component of the state’s ideological legitimacy.

In these centuries, then, the ideology of medieval Hindu kingship became fully elaborated in the delta. The earliest Sena kings, it is true, had justified their establishment of power in terms of their victorious conquests,[48] and in this respect they differed little from their own conquerors, the Turks of the early Delhi sultanate. Yet the Senas’ political theory was based on a religious cosmology fundamentally different from that of their Muslim conquerors. In the Islamic conception, the line separating the human and superhuman domains was stark and unbridgeable; neither humans nor superhumans freely moved or could move from one domain to the other. In the Sena conception, however, as in medieval Hindu thought generally, the line between human and superhuman was indistinct. Since it was the king’s performance of royally sponsored rituals that served to uphold dharma—that is, cosmic, natural, and human order as understood in classical Indian thought—movement between the two domains could be actuated by the intervention of the king’s ritual behavior. “He was never tired of offering sacrifices,” one inscription boasts of Vijaya Sena (ca. 1095–1158),

By ritually bringing about “an interchange of the inhabitants of heaven and earth,” the king symbolically erased the distinction between the human and superhuman domains. Like Hindu kings elsewhere in eleventh- and twelfth-century India, the Senas projected their vision of the cosmos and their own proper place in it through the medium of architecture, specifically the monumental royal temple. By replicating cosmic order in the medium of stone monuments, in which they placed an image of their patron overlord, and by placing themselves and their temples at the center of the earthly stage, these kings mimicked the manner in which their patron overlord presided over cosmic order. Thus Vijaya Sena proclaimed:and through his power Dharma [dharma], though she had become one-legged in the course of time, could move about on the earth, quickly taking the help of the rows of sacrificial pillars. That sacrificer [the king] calling down the immortals from the slopes of [the cosmic mountain] Meru full of the enemies killed by himself, brought about an interchange of the inhabitants of heaven and earth. (For) by (the construction of) lofty “houses of gods” (i.e. temples) and by (the excavation of) extensive lakes the areas of both heaven and earth were reduced and thus they were made similar to one another.[49]

The Sena kings also expressed their kingly authority by performing the “Great Gift” ceremony in honor of their patron overlord, who under the last pre-conquest king, Lakshmana Sena, was Vishnu. Although this great god was the ritualized recipient of the “Great Gift,” its effective recipients were officiating Brahman priests.[51][The king] built a lofty edifice of Pradyumneśvara, the wings, and plinth and the main structure of which occupied the several quarters, and the middle and the uppermost parts stretched over the great oceanlike space—(it is) the midday mountain of the rising and setting Sun who touches the Eastern and Western mountains, the supporting pillar of the house which is the three worlds and the one that remains of the mountains.… If the creator would make a jar, turning on the wheel of the earth Sumeru like a lump of clay, then that would be an object with which could be compared the golden jar placed by him (i.e., the king) on (the top of) this (temple).[50]

| • | • | • |

The Diffusion of Bengali Hindu Civilization

By the time of the Muslim conquest, then, the official cult of a cosmic overlord, monumental state temples, and royally patronized Brahman priests had all emerged as central components of the Senas’ religious and political ideology. It was not the case, however, that by that time early Indo-Aryan civilization and its later Hindu offshoot had penetrated all quarters of the Bengal delta evenly. Rather, the evidence indicates that Bengal’s northwestern and western subregions were far more deeply influenced by Indo-Aryan and Hindu civilization than was the eastern delta, which remained relatively less peasantized and less Hinduized. This is seen, for example, in pre-thirteenth-century land use and settlement patterns. A seventh-century grant of land on the far eastern edge of the delta, in modern Sylhet, describes the donated territory as lying “outside the pale of human habitation, where there is no distinction between natural and artificial; infested by wild animals and poisonous reptiles, and covered with forest out-growths.”[52] In such regions, grants of uncultivated land were typically made in favor of groups of Brahmans or to Buddhist monasteries with a view to colonizing the land and bringing it into cultivation.[53] One plate issued by a tenth-century Chandra king granted an enormous area of some one thousand square miles in Sylhet to the residents of eight monasteries; it also settled about six thousand Brahmans on the land.[54]

But in the west the situation was different. In the Bhagirathi-Hooghly region, most land grants were made to individual Brahmans and were typically small in size. After the ninth century, royal donations in this area aimed not at pioneering new settlements but at supporting Brahmans on lands already brought under the plow. These grants typically gave detailed measurements of arable fields, specified their revenue yields, and instructed villagers to pay their taxes in cash and kind to the donees.[55] Such terms and conditions point to a far greater intensity of rice cultivation, a higher degree of peasantization, and a greater population density in the Bhagirathi-Hooghly region than was the case in the relatively remote and more forested eastern delta.

Differences between east and west are also seen in patterns of urbanization. Using archaeological data, Barrie Morrison has made comparative calculations of the total area of ancient Bengal’s six principal royal palaces.[56]

The four largest of these were located in cities of Varendra, or northwestern Bengal, whereas the palace sites of Vikrampur and Devaparvata, located in the east and southeast (at Lalmai) respectively (see map 1), were many times smaller. In part, this reflects the political importance of Varendra, always a potential player in struggles over the heartland of Indo-Aryan civilization owing to its contiguity with neighboring Magadha and the middle Gangetic Plain. Yet the data on palace size also indicate a greater degree of urbanization and a higher population density in the delta’s northwestern sector than was the case in the south and east. With larger cities, too, went greater occupational specialization and social stratification, for in Bengal as in ancient Magadha, the core areas of Indo-Aryan civilization spread with the advance of city life.

Pundranagara 22,555,000 sq. ft. Pandua 13,186,800 sq. ft. Gaur 10,000,000 sq. ft. Kotivarsha 2,700,000 sq. ft. Vikrampur 810,000 sq. ft. Devaparvata (at Lalmai) 360,000 sq. ft.

There are several reasons for the greater penetration of Indo-Aryan culture in the western delta than in the east. One has to do with persistent facts of climate. Moving down the Gangetic Plain, the monsoon rainfall increases as the delta is approached, and within the delta it continues to increase as one crosses to its eastern side. The Bhagirathi-Hooghly region, comprising most of today’s West Bengal, gets about fifty-five inches of rain annually, whereas central and eastern Bengal get between sixty and ninety-five inches, with the mouth of the Meghna receiving from one hundred to one hundred and twenty and eastern Sylhet about one hundred and fifty inches.[57] If this climatic pattern held in ancient times, the density of vegetation in the deltaic hinterland, formerly covered with thick forests, mainly of śāl (Shorea robusta),[58] would have increased as one moved eastward. Cutting it would have required much more labor and organization, even with the aid of iron implements, than in the less densely forested westerly regions.

Also at work here were patterns of Brahman immigration to and within Bengal. West Bengal was geographically contiguous to the upper and middle Gangetic zone, long established as the heartland of Indo-Aryan civilization. Hence, when from the ninth century an increasing number of scholarly and ritually pure Brahmans migrated from this area into Bengal, most received fertile lands in the western delta. On the other hand recipients of lands further to the east, in the modern Comilla and Chittagong area, tended to be local Brahmans or migrants from neighboring parts of the delta.[59] This suggests an eastward-sloping gradient of ritual status, with higher rank associated with the north and west, and lower rank with the less-settled east.

Finally, the different degree of Aryanization in the eastern and western delta was related to ancient Bengal’s sacred geography, and in particular to the association of the Ganges River with Brahmanically defined ritual purity. This river was already endowed with great sanctity when Indo-Aryans entered the delta,[60] and for centuries thereafter Hindus made pilgrimage sites of towns along its banks in western Bengal—for example, Navadwip, Katwa, Tribeni, Kalighat, and Ganga Sagar. With reference to the eastern delta, on the other hand, the geographer S. C. Majumdar notes that “no such sanctity attaches to the Padma below the Bhagirathi offtake nor is there any place of pilgrimage on her banks.”[61] This was because from prehistoric times through the main period of Brahman settlement in the delta, the principal channel of the Ganges flowed down the delta’s westernmost corridor through what is now the Bhagirathi-Hooghly channel. It did not divert eastward into the Padma until the sixteenth century, long after the Turkish conquest. As a result, the river’s sanctity lingered on in West Bengal—even today the Bhagirathi-Hooghly River is sometimes called the Adi-Ganga, or “original Ganges”—while the eastern two-thirds of the delta, cut off from the Ganges during the formative period of Bengal’s encounter with Indo-Aryan civilization, remained symbolically disconnected from Upper India, the heartland of Indo-Aryan sanctity and mythology.

By the thirteenth century, then, most of Bengal west of the Karatoya and along the Bhagirathi-Hooghly plain had become settled by an agrarian population well integrated with the Hindu social and political values espoused by the Sena royal house. There, too, indigenous tribes had become rather well assimilated into a Brahman-ordered social hierarchy. But in the vast stretches of the central, eastern, and northeastern delta, the diffusion of Indo-Aryan civilization was far less advanced. In the Dhaka area, the city of Vikrampur, though an important administrative center, from which nearly all of Bengal’s copper-plate inscriptions were issued in the tenth through twelfth centuries, shrank before its neighbors to the west in both size and sacredness. And in the extreme southeast, the impressive urban complex at Lalmai-Mainamati, with its distinctive artistic tradition,[62] its extensive history of Buddhist patronage, and its cash-nexus economy, appears somewhat disconnected from the Gangetic culture to the west, looking outward to wider Indian Ocean commercial networks.

In sum, although the eastern delta had certainly begun to be peasantized, especially along the valleys of the larger river systems, such as at Vikrampur and Lalmai, the process had not advanced there to the extent that it had in the west and northwest of Bengal. East of the Karatoya and south of the Padma lay a forested and marshy hinterland, inhabited mainly by non-Aryan tribes not yet integrated into the agrarian system that had already revolutionized Magadha and most of western Bengal. As a result, in 1204, when Muhammad Bakhtiyar’s Turkish cavalry captured the western Sena city of Nudiya, it was to this eastern hinterland that King Lakshmana Sena and his retainers fled. It was also in this region that subsequent generations of pioneers would concentrate their energies as Bengal’s economic and cultural frontiers continued to migrate eastward.

Notes

1. Situated in the northwestern delta north of the Padma River, Varendra included the territories now constituting the districts of Malda, Pabna, Rajshahi, Bogra, Dinajpur, and Rangpur. The Bhagirathi-Hooghly basin included several ancient cultural subregions—Suhma, Vardhamana, Raḍha, and Gauḍa—corresponding to the modern districts of Midnapur, Howrah, Hooghly, Burdwan, Birbhum, and Mur-shidabad. Ancient Vanga, or Central Bengal, included the area corresponding tothe modern districts of Dhaka, Faridpur, Jessore, Bakarganj, Khulna, Nadia, andTwenty-four Parganas. Samatata included the hilly region east of the Meghna River in the southeastern delta, corresponding to modern Comilla, Noakhali, and Chittagong. Harikela referred to the delta’s northeastern hinterland, including modern Mymensingh and Sylhet. On the ancient subregions of Bengal, see Barrie M. Morrison, Political Centers and Cultural Regions in Early Bengal (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1970), esp. ch. 4, and Susan L. Huntington, The “Pala-Sena” Schools of Sculpture (Leiden: Brill, 1984), 171. For a discussion of Bengal’s physical subregions, see O. H. K. Spate and A. T. A. Learmonth, India and Pakistan: A General and Regional Geography, 3d ed. (London: Methuen, 1967), 571–73.

2. Aitareya Brāhmaṇa 7.6, cited in S. K. Chatterji, Origin and Development of the Bengali Language (Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press, 1926), 1: 62.

3. These include the Āyāraṃa Sutta and Gaina Sūtras, cited in Chatterji, Origin and Development, 1: 71.

4. Chatterji, Origin and Development, 1: 67.

5. P. C. Das Gupta, The Excavations at Pandu Rajar Dhibi (Calcutta: Directorate of Archaeology, West Bengal, 1964), 14, 18, 22, 24, 31. The site is located on the southern side of the Ajay River, six miles from Bhedia. The archaeological record reveals prehistoric rice-cultivating communities living all along the middle Gangetic Plain. Excavations in the Belan Valley south of Allahabad have found peoples cultivating rice (Oryza sativa) as early as the middle of the seventh millennium B.C., which is the earliest-known evidence of rice cultivation in the world. G. R. Sharma and D. Mandal, Excavations at Mahagara, 1977–78 (a Neolithic Settlement in the Belan Valley), vol. 6 of Archaeology of the Vindhyas and the Ganga Valley, ed. G. R. Sharma (Allahabad: University of Allahabad, 1980), 23, 27, 30.

6. Ram Sharan Sharma, Material Culture and Social Formations in Ancient India (New Delhi: Macmillan India, 1983), 118.

7. See Arlene R. K. Zide and Norman H. Zide, “Proto-Munda Cultural Vocabulary: Evidence for Early Agriculture,” in Austroasiatic Studies, ed. Philip N. Jenner, Laurence C. Thompson, and Stanley Starosta, pt. 2 (Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1976), 1324. The authors show that Munda terms for uncooked, husked rice (Oryza sativa) have clear cognates in the language’s sister Austroasiatic branch, Mon-Khmer. They also conclude that “the agricultural technology included implements which presuppose the knowledge and use of such grains and legumes as food, since, the specific and consistent meanings for ‘husking pestle’ and ‘mortar’ go back, at least in one item, to Proto-Austroasiatic.”

8. Te-Tzu Chang, “The Impact of Rice on Human Civilization and Population Expansion,” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 12, no. 1 (1987): 65.

9. Spate and Learmonth, India and Pakistan, 47.

10. Romila Thapar, From Lineage to State: Social Formations in the Mid-First Millennium B.C. in the Ganga Valley (Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1984), 68. Although fire could have been used for clearing forests of their cover, permanent field agriculture required the removal of tree stumps, for which the use of iron axes and spades would have been necessary. Sharma, Material Culture, 92.

11. Sharma, Material Culture, 92–96.

12. Ibid., 96–99.

13. Michael Witzel, “On the Localisation of Vedic Texts and Schools,” in India and the Ancient World: History, Trade and Culture before A.D. 650, ed. Gilbert Pollet (Leuven: Departement Oriëntalistiek, 1987), 173–213; and id., “Tracing the Vedic Dialects,” in Dialectes dans les littératures Indo-Aryennes, ed. Colette Caillat (Paris: Collège de France, Institut de civilisation indienne, 1989), 97–265.

14. Romila Thapar, “The Image of the Barbarian in Early India,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 13, no. 4 (October 1971): 417. The text is the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa.

15. These include the Mārkaṇdeya Purāṇa and the Yajṅavalkya Smṛti 3.292. Cited in Thapar, “Image,” 417.

16. For example, the eastern frontier of Indo-Aryan country in the ṛg Veda was the Yamuna River; in the Paippalāda Saṁhitā, it was Kasi (Benares region); in the Saunakīya Saṁhitā, it was Anga (eastern Bihar); and in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa (7.18), it was Pundra, or northern Bengal. See Witzel, “Localisation,” 176, 187.

17. Today modern Bengali, an Indo-Aryan language, is surrounded on all sides by a number of non-Indo-Aryan language groups—Austroasiatic, Dravidian, Sino-Tibetan—suggesting that over the past several millennia the non-Indo-Aryan speakers of the delta proper gradually lost their former linguistic identities, while those inhabiting the surrounding hills retained theirs. On the other hand, the survival of non-Indo-Aryan influences in modern standard Bengali points to the long process of mutual acculturation that occurred between Indo-Aryans and non-Indo-Aryans in the delta itself. Such influences include a high frequency of retroflex consonants, an absence of grammatical gender, and initial-syllable word stress. As M. H. Klaiman observes, “descendants of non-Bengali tribals of a few centuries past now comprise the bulk of Bengali speakers. In other words, the vast majority of the Bengali linguistic community today represents present or former inhabitants of the previously uncultivated and culturally unassimilated tracts of eastern Bengal.” M. H. Klaiman, “Bengali,” in The World’s Major Languages, ed. Bernard Comrie (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 499, 511. See also Chatterji, Origin and Development, 1: 79, 154; and F. B. J. Kuiper, “Sources of the Nahali Vocabulary,” in Studies in Comparative Austroasiatic Linguistics, ed. Norman H. Zide (Hague: Mouton, 1966), 64. For a map showing the modern distribution of the Bengali and non-Indo-Aryan languages in the delta region, see Joseph E. Schwartzberg, ed., A Historical Atlas of South Asia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 100.

18. Cited in Witzel, “Localisation,” 195.

19. Colin P. Masica, “Aryan and Non-Aryan Elements in North Indian Agriculture,” in Aryan and Non-Aryan in India, ed. Madhav M. Deshpande and Peter E. Hook (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1979), 132.

20. This is not to say that anything resembling today’s caste system suddenly appeared at this early date, although the ideological antecedents for that system are clearly visible in this framework.

21. See Thapar, From Lineage to State, chs. 2 and 3. Some of the new cities and states included Campa of Anga, Rajghat of Kasi, Rajgir of Magadha, and Kausambi of Vatsa. It has been suggested that the new urbanized areas appeared so suddenly because of competition among former Indo-Aryan lineage groups for wealth and power, which in turn created a need for centralized political systems that could sustain war efforts. See George Erdosy, “The Origin of Cities in the Ganges Valley,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 28, no. 1 (February 1985): 96–103.

22. Northern Black Polished ware has been discovered in Chandraketugar in the Twenty-four Parganas, Tamluk in Midnapur, Bangarh and Gaur in Malda, Mahasthan in Bogra, and Khadar Pather Mound and Sitakot in Dinajpur. See Clarence Maloney, “Bangladesh and Its People in Prehistory,” Journal of the Institute of Bangladesh Studies 2 (1977): 17.

23. Ramaranjan Mukherji and Sachindra Kumar Maity, Corpus of Bengal Inscriptions Bearing on History and Civilization of Bengal (Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 1967), 39–40.

24. Gayatri Sen Majumdar, Buddhism in Ancient Bengal (Calcutta: Navana, 1983), 11.

25. R. C. Majumdar, History of Ancient Bengal (Calcutta: G. Bharadwaj & Co., 1971), 522–23. See Schwartzberg, ed., Historical Atlas, 18, 19.

26. Puspa Niyogi, Brahmanic Settlements in Different Subdivisions of Ancient Bengal (Calcutta: R. K. Maitra, 1967), 4, 19–20.

27. As D. D. Kosambi noted, Brahman rituals were accompanied by “a practical calendar, fair meteorology, and sound-working knowledge of agricultural technique unknown to primitive tribal groups which never went beyond the digging-stock or hoe.” D. D. Kosambi, “The Basis of Ancient Indian History,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 75, pt. 1 (1955): 36. See also ibid., pt. 4, 236n. Kosambi was the first to observe that “the major historical change in ancient India was not between dynasties but in the advance of agrarian village settlements over tribal lands, metamorphosing tribesmen into peasant cultivators or guild craftsmen.” Ibid., 38.

28. A similar process has been noted for neighboring Assam. Analyzing inscriptions of the fifth to thirteenth centuries, Nayanjot Lahiri notes “an irresistible correlation between the peasant economy and the principles involved in the caste structure in Assam. There is no group of tribesmen in this region which has not involved itself in the caste structure in some form or the other after the adoption of wet rice cultivation. In the process of detribalisation and their inclusion in the traditional Hindu fold the Brahmins were extremely significant. Detribalization involved, among other things, a renunciation of tribal forms of worship and the acceptance of traditional Hindu gods and goddesses.” Nayanjot Lahiri, “Landholding and Peasantry in the Brahmaputra Valley c. 5th-13th centuries A.D.,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 33, no. 2 (June 1990): 166.

29. Although most Pala copper plates from ca. 750 to ca. 950 were issued from Magadha in modern Bihar, literary sources place the dynasty’s original home in Varendra, over which the Palas continued to exercise authority until the mid twelfth century. Majumdar, History of Ancient Bengal, 99, 159.

30. Ahbar as-Sin wa l-Hind: Relations de la Chine et de l’Inde, trans. Jean Sauvaget (Paris: Société d’édition “Les Belles Lettres,” 1948), 13.

31. Mas‘udi, Les Prairies d’or [Murūj al-dhahab], trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille, corrected by Charles Pellat (Paris: Société asiatique, 1962), 1: 155. “Dans le royaume du Dharma [i.e., Pala], les transactions commerciales se font avec des cauris (wada‘), qui sont la monnaie du pays. On y trouve le bois d’aigle (‘ūd), l’or et l’argent; on y fabrique des étoffes d’une finesse et d’une délicatesse inégalées. Les Indiens mangent sa [i.e., the elephant’s] chair, et ils sont imités par les Musulmans qui habitent ce pays, parce qu’il est de la même espèce que les boeufs et les buffles.”

32. Sauvaget, Ahbar as-Sin wa l-Hind, 13; Mas‘udi, Prairies 1: 155.

33. M. R. Tarafdar, “Trade and Society in Early Medieval Bengal,” Indian Historical Review 4, no. 2 (January 1978): 277. The evidence for Chandra coinage is based on a horde of about 200 silver coins discovered at Mainamati “in a level,” writes A. H. Dani, “which clearly belongs to the time of the Buddhist Chandra rulers of East Bengal, who had their capital at Vikramapura.” The mint-place given on some of these coins is Pattikera, the name of a village still extant in Comilla District. See Dani, “Coins of the Chandra Kings of East Bengal,” Journal of the Numismatic Society of India 24 (1962): 141; Abdul Momin Chowdhury, Dynastic History of Bengal, c. 750–1200 A.D. (Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1967), 163 and n.5. See also Bela Lahiri, “A Survey of the Pre-Muhammadan Coins of Bengal,” Journal of the Varendra Research Museum 7 (1981–82): 77–84.

34. Frederick M. Asher, The Art of Eastern India, 300–800 (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1980), 91.

35. Barrie M. Morrison, Lalmai, a Cultural Center of Early Bengal: An Archaeological Report and Historical Analysis (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1974), 27. For a discussion of Buddhist civilization in ancient Samatata, see Puspa Niyogi, “Buddhism in the Mainamati-Lalmai Region (with Reference to the Land Grants of S. E. Bengal),” Journal of the Varendra Research Museum 7 (1981–82): 99–109.

36. Haroun er Rashid, “Some Possible Influences from Bengal and Bihar on Early Ankor Art and Literature,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 22, no. 1 (April 1977): 9–19.

37. For example, Dharmapala’s son Devapala (812–50) received an envoy from the Buddhist king of Srivijaya in Java-Sumatra, who requested the Pala king to grant a permanent endowment to a Buddhist monastery at Nalanda. Similarly, during the reign of Ramapala (1072–1126), the ruler of the Pagan Empire in Burma, Kyansittha (d. ca. 1112), sent a considerable quantity of jewels by ship to Magadha for the purpose of restoring the Buddhist shrines in Bodh Gaya. Hirananda Shastri, “The Nalanda Copper-Plate of Devapaladeva,” Epigraphia Indica 17 (1924): 311–17. Janice Stargardt, “Burma’s Economic and Diplomatic Relations with India and China from Early Medieval Sources,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 14, no.1 (April 1971): 57.

38. On the Arab trade diaspora, traceable in the Indian Ocean to the first century A.D. and especially evident by the tenth century, see André Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 1: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th-11th Centuries (Leiden: Brill, 1990), 65–86.

39. Notes by Chinese pilgrims in Bengal attest to the drop in the number of Buddhist monasteries there, and also to the emergence of Brahmanic temples. Writing in the early fifth century, Fa-hsien counted twenty-two monasteries in Tamralipti. Two centuries later, Hsüan-tsang counted just ten monasteries there, compared with fifty Brahmanic temples. By 685, the number of monasteries in Tamralipti had dropped to just five or six, as recorded by the pilgrim I-Ching. A similar pattern held in North Bengal (Varendra), where Hsüan-tsang counted twenty monasteries and a hundred Brahmanic temples, and in southeast Bengal (Samatata), where he counted thirty monasteries and a hundred temples. The decline in court patronage of monasteries might not have been so serious, however, had there been a fervent and supportive Bengali Buddhist laity. But what is conspicuously absent in the history of East Indian Buddhism as recorded by Taranatha, a Tibetan monk who wrote in 1608, is any evidence of popular enthusiasm for the religion. Rather, the author seems to have identified the fate of Buddhism with that of its great monasteries. The withdrawal of court patronage for such institutions thus proved fatal for the religion generally. See Chinese Accounts of India: Translated from the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang, trans. Samuel Beal (Calcutta: Susil Gupta, 1958), 4: 403, 407, 408; A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671–695) by I-Ching, trans. J. Takakasu (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1966), xxxiii; and Taranatha’s History of Buddhism in India, ed. Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (Calcutta: K. P. Bagchi & Co., 1980), xiii-xiv.

40. Huntington, “Pala-Sena” Schools, 179, 201. Most of the art patronized by Pala kings of the eleventh and twelfth centuries was Brahmanic in subject matter, with Vaishnava themes outnumbering the rest three to one. Ibid., 155.

41. H. C. Ray, The Dynastic History of Northern India (Early Medieval Period), 2d ed. (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1973), 1: 354–58.

42. Huntington, “Pala-Sena” Schools, 179, 201.

43. Ronald Inden, “The Ceremony of the Great Gift (Mahādāna): Structure and Historical Context in Indian Ritual and Society,” in Marc Gaborieau and Alice Thorner, Asie du sud: Traditions et changements (Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1979), 131–36.

44. Ibid., 133.

45. Ibid., 134. See also Ronald Inden, “Hierarchies of Kings in Early Medieval India,” Contributions to Indian Sociology 15, nos. 1–2 (1981): esp. 121–25.

46. Swapna Bhattacharya, Landschenkungen und staatliche Entwicklung im frühmittelalterlichten Bengalen (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1985), 165.

47. Morrison, Political Centers, 108.

48. See Nani Gopal Majumdar, Inscriptions of Bengal, vol. 3 (Rajshahi: Varendra Research Society, 1929), 52–53.

49. Ibid., 54.

50. Today, unfortunately, only a few architectural fragments remain of what must have been a magnificent edifice, situated at Deopara some seven miles northwest of Rajshahi town, on a road leading to Godagari. Ibid., 42, 54–55.

51. Thus we read that Lakshmana Sena had made a donation of cultivated, tax-free lands “as fee for the ceremony of the Great Gift in which a golden horse and chariot were given away, on this auspicious day, after duly touching water and in the name of the illustrious god Narayana [Vishnu], for the merit and fame of my parents as well as myself, for as long as the moon, sun and the earth endure, according to the principle of Bhumichchhidra [tax-exempt status], to Iśvaradevaśarmman, who officiated as the Acharya [priest] in the ‘Great Gift of gold horse and chariot.” ’ Ibid., 104.

52. Cited in Niyogi, Brahmanic Settlements, 41.

53. Bhattacharya, Landschenkungen, 168.

54. Morrison, Political Centers, 98.

55. Ibid., 17, 99. Bhattacharya, Landschenkungen, 168.

56. Morrison, Lalmai, 124.

57. Spate and Learmonth, India and Pakistan, 575.

58. Ibid., 63; Anil Rawat, “Life, Forests and Plant Sciences in Ancient India,” in History of Forestry in India, ed. Ajay S. Rawat (New Delhi: Indus Publishing Co., 1991), 246.

59. Bhattacharya, Landschenkungen, 167–68.

60. The Ganges cult is of great antiquity, and the associations of water with life, fertility, and the Goddess are traceable to the Indus Valley civilization. We know from the Arthaśāstra (4.3), composed between the fourth century B.C. and the third century A.D., that prayers were offered to the Ganges as a remedy for drought. By the sixth century, figures of the goddess Ganga figured prominently as guardians on temples of the Gupta dynasty (ca. 300–550 A.D.). Steven G. Darian, The Ganges in Myth and History (Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1978), 88.

61. S. C. Majumdar, Rivers of the Bengal Delta (Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press, 1942), 66. See also Surinder Mohan Bhardwaj, Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973), 36–37, 81; Schwartzberg, ed., Historical Atlas, 34.

62. Asher, Art of Eastern India, 99. Huntington, “Pala-Sena” Schools, 200.