Preferred Citation: Frank, Ellen Eve. Literary Architecture: Essays Toward a Tradition: Walter Pater, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Marcel Proust, Henry James. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1979. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9t1nb63n/

| Literary ArchitectureEssays Toward a TraditionEllen Eve FrankUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1983 The Regents of the University of California |

To my family

Preferred Citation: Frank, Ellen Eve. Literary Architecture: Essays Toward a Tradition: Walter Pater, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Marcel Proust, Henry James. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1979. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9t1nb63n/

To my family

AUTHOR'S NOTE

I began thinking about architecture as a possible analogue for literature in 1971. The core essays exploring this possibility were written in the years following, from 1972 to 1974. The enlargement upon the idea, the context into which I have placed these essays, came from my experiences after these essays were completed and was integrated into the manuscript in 1976.

Special care has been taken in the selection and arrangment of the photographs and in the printing of this book. I trust literary architecture can weather the time these processes have rightly taken.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I should like to honor my teachers: Donald Davie, Herbert Lindenberger, Douglas Smith, Ian Watt, Wesley Trimpi, Professor Sir Ernst Gombrich. This book is a small gesture of my appreciation. I should also like to acknowledge the generous grants I received for this work: the Fulbright Foundation, Leverhulme Trust Fund, Ford Foundation; to thank the staffs of Stanford University, the Courtauld and Warburg Institutes for their help; William Petzel for his fine photographic skills; Catherine King for her typing. I also wish to acknowledge those who read the manuscript, either in its entirety or portions of it, and who gave me encouragement: Judith Allen, Rudolph Arnheim, Robin Bisio, R. Howard Bloch, Richard Bridgman, Carol Christ, Anne Mellor, Leonard Michaels, Alex Zwerdling; Lloyd Cross for his practical aid; and John Osman for his particular good will. I extend special gratitude to my sponsoring editor William McClung and to my designer Wolfgang Lederer for their commitment to this book and their care for its embodied form. Finally, I should like to thank my mother, Dorothy C. Frank, for her help in the preparation of the manuscript and for her kind support of my work.

E. E. F.

INTRODUCTION

Sit in a child's wagon. Someone pulls you through this house. You have entered white walls thick, prepared for the frescoing of your thoughts. Brown ground of earth is your floor, sky your ceiling. In the first room are Greek temples. You are pulled around them. In one corner you pass Roman ruins; in another, a plain English house with a flight of stairs to its roof. Then the second room. You do not know how you got there. Perhaps you were outside in passage, with Pegasus. In this room are cathedral façades, arches and spires, erect like sentries to Weather. Winged flight: the third room. You begin to smile. Here is a church entire, grey, light. But when you go inside you wish to be outside. So your guide pulls you faster until you no longer know whether you look up outside or are arched over inside. Winged flight: the fourth room. You walk, you have no guide. Here you find smaller rooms crowded with furniture or

cleared in deference to window-views of churches, palaces, or people. Winged flight: the fifth is not a room at all but a hall. Every few feet issues a cord stretching out from under the wall. Windows mark the space above each cord. When you look through the windows, you see trails of houses and cathedrals, this cord stretching straight to Greece, that one shorter going to nineteenth-century France, another marked with speechmakers, still another with men writing on stone tablets. And then you are spun around, you cannot tell this way from that. You are outside. The white walls are gone. It is the world you are in. But ah, over there is the Parthenon, here a Gothic church, to the right your own house with a stairway to the attic and its own view. The world inside was no different, it was just bounded by white walls.

The house I have described is the book before you, the open-air architecture of Literary Architecture . The five rooms are its five chapters, each filled with the furniture of its subject matter, each very specifically located, separated by halls of space. The tour is what I hope will be the experience of reading: a transitive activity connecting these separate rooms of vision and concluding in reflection on these connections. That we sit in a child's wagon to begin this tour is a gentle admonition that our activity of perceiving be undertaken with curiosity, the seeing and taking note of entrances and exits, peripheries and contents. For these are the tissue of this book: the architecture of literature as external configuration, as form and embodiment, of consciousness.

Literary Architecture is a building of connection. The particular subject, what may be thought of as the occasion, is the relationships between architecture and literature as announced in the writings of Walter Pater, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Marcel Proust, and Henry James; for each of these writers declares in one way or another that literature is like architecture. The larger subject is a proposition. There exists as a convention in literature the habit of comparison between architecture and literature extending from Plato to Samuel Beckett and discovering particular expression late in the nine-

teenth century and on into the twentieth. I propose that this convention constitutes a tradition which I should like to call literary architecture. I present the tradition of literary architecture by noting its occurrence and by asking this question: what may be accomplished when writers select architecture as art analogue for literature? The question is new to literary studies. It constitutes the motive for this book.

And yet this book as a building of connection is more than a structure with contents. For a building is not an object (product) only; it is, importantly, an activity. And it is the activity of building that constitutes my largest subject, that is, the nature of experience. Experience may be particularized in literary study to mean critical inquiry, methodology, reading; for our purposes, I should like it to be taken to mean our way of noticing or perceiving, our activity of being in the world. There is precedent for understanding experience and being as building: if we follow the word building to its etymological origins, we find it comes from an Indo-European word meaning "to be, to exist, to grow."[1] It is no surprise, then, that both building-as-object (product) and building-as-activity require and turn upon space constructs, the art of architecture. We may use the brief dream I have recorded as a literary example, for both building-as-object (product) of perception and building-as-activity of perceiving are present. The architectural structure (house) that we enter encloses its own kind of structure (architecture) as its contents (or, in literary language, its content): the Greek temples of Pater, the cathedral remains of Hopkins, the church of Proust, the writing-rooms of James. Our experience as an activity of being—entering and moving through interior space, see-

ing wall-boundaries, looking through windows, feeling stress—is governed by and utilizes the architectural structures we perceive, as we perceive them. This is the constitutive experience. As we tour the rooms, we feel "point of view" as a position of place (where we stand when we view something), "circumspection" as moving around an object that we might see it from all sides, "introduction" as entering a new room-space, "conclusion" as the closing of a portion or lot of space. Similarly, "critical distance" becomes/is the physical space-relation between viewer and viewed (di-stance), "perception" is seeing through space, "perceptual construct" or "system" is architectural structure. Through literary architecture, the language of literary perception displays its enduring substantiality. Experience itself and the conditions of experience marry, may indeed be one with, the objects of experience.

My intention in this book, therefore, is not only to connect architecture and literature in particular writers and in literary history and theory; it is also to suggest the connection between architecture and literature in perceptual experience, as content and activity, subject and method. The tradition I propose, literary architecture, is also the one that I use as method; the one is a tradition or convention in art—literary, critical—the other a tradition or method in life—the activity of perception. The reading that I propose involves two steps: first, the noticing of internal architectural structures, those within the literary work, a James or a Proust novel, or even this book. These internal structures may be, for instance, cathedrals which symbolize character, temples which organize memory, or dwelling-houses which are settings for action. The second task of this sort of reading would be a looking-up

from the book to notice the same or similar structures outside, in the physical, external world. (This approximates the exit from the house in the dream.) We may think of this second activity as the noticing of echoes or correspondences between internal and external structures; but "internal" structures are also structures of consciousness, conventions of perception, systems of belief, as well as the activities of thought and feeling. By "external," in addition to physical architecture and nature's architecture surrounding us, we must also understand all art-as-construct.[2]

Such a structure—one which discovers an internal, felt equivalent—makes sense , or means. We have here, in fact, one definition of meaning: that which has the same nature (the power of movement or correspondence between inner and outer) inside and outside which the occasion of place does not alter. Literature, then, may be described as the giving of something (place, form, or idea) to meaning , not the giving of meaning to something. That consciousness as structure (human nature ) corresponds to or extends the world as structure is easy enough to understand: man and the world are composed of the same elements which either are or have the illusion of being spatial-temporal, the difference being combinations or proportions of elements. Man's main difference is that he imagines his consciousness or experience to be bounded or located in particular space, within white walls, bodies, time, while what is outside his personal realm he imagines to be boundless as he thinks the universe is boundless, timeless as it is timeless. Because of this structural correspondence, we may read all structures, not only those cited within this study, with a mental ruler and a table of equivalents: structures have

either actual spatial extension (architecture) in the physical world or the language of spatial extension (literature) in the world of thought. They may be either as small as individual "cells," as in the prose of Walter Pater, or as large as the "womb-of-all, home-of-all, hearse-of-all night," as in the poetry of G. M. Hopkins.[3] To understand is to notice the internal or felt equivalent of the external structure; the activity of understanding is the activity of learning not what but how that external structure makes sense. Thus my book not only connects two separate arts, architecture and literature, but aspires also to connect subject with method. I should now like to add that it also aspires to connect method with meaning. A building of connection is also a building of meaning.

What I have called literary architecture in itself, and inevitably, proposes to make a connection of a very audacious sort. This is the larger connection of correspondence or equivalence between the two arts themselves, architecture and literature, the one whose characteristic form seizes actual space as territory, the other whose characteristic form spells time. Correspondence is actually active: it is a process of conversion obeying the laws of conservation in which there is no loss. Writers who select architecture as their art analogue dematerialize the more material art, architecture, that they may materialize the more immaterial art, literature. In this way, architecture and literature relinquish an analogical relationship to marry as literary architecture. The conversion, however, does not occur in the forward direction of construction or composition only. It requires a backward activity to precede it, the unbuilding or decomposing of existing structures, either actual architecture or

present conventions of perception. The backward activity not only provides for the transformational process of building literary architecture; it actually makes possible that process by preparing ground or clearing the space necessary for the new—the artist's as yet unbuilt structure of seeing. (Ground clearing is especially important in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when to build a view of the world is to re build an existing world view.) In literary terms, the process of building is "composing," the unbuilding is the "decomposing," or the activity of analysis.

Only in my last chapter do I relinquish particular focus on the literary architecture of my four principal figures. In this final chapter, I hope that, having experienced the activities of building, we may reflect back upon that experience and from it construe larger meaning. The delay is intentional: cognition—knowing—engages, while recognition—knowing that we know—disengages; recognition, in other words, requires the space-time construct distance . Only as conclusion may we understand fully the relation of correspondence, namely, the lucid coherence of literary architecture as practiced by these four writers: for relation requires experience to precede it. Therefore, while my theory of literary architecture emerges with the text, I present the formal tradition of literary architecture as a kind of Proustian retrospection, our reflection upon the buildings of literary architecture, something which occurs and can occur only after we have built the structures themselves.

It will be seen that my Literary Architecture thus cannot claim to be a traditional book, whether in its field, its subject, or its research. It attempts to take note of

something which does not constitute an academic field but which, as its very subject is space—both ground and territory—does constitute a field of another sort, the field of literary and perceptual activity. This is a field which, though it is only just now beginning to be explored by critics, has been so explored by artists that it deserves to be named and recognized as a tradition proper, the tradition of literary architecture. Since this academically new field has been no field, there could be no traditional research within it; instead I have conducted a search, and my method has been one of following hunches, of asking how the architectural analogue serves literary art, and of looking for that "how" into our own activity of perceiving. Literature—our particular focus—is, of course, about itself and about life; that is, it is about our experience of being alive. I have tried not to turn to another system to explain literature and its meaning but to turn to the subject of literature, life, and to those self-consciously selected structures which these four writers use to help them organize their perceptions. My precedent is in the writers we are looking at: for Pater, Hopkins, Proust, and James teach us not only how to read but also how to see, not only the world of literature, not only the world of physical architecture, but also the structures of consciousness itself, most especially the structures of our felt and remembered experience of life.

I may be asked why there are few connective links between my chapters and why this study does not follow chronology so as to constitute a history. In answer, I must plead the nature of my subject matter. Writers who select architecture as their art analogue for literature choose to express time—what we may think of as the linearity, the storyness of history—in terms of space, that

is, on location. They each place us within a particular spatial construct, a literary house, one with extension and peripheries which we are asked to observe. The chapters of Literary Architecture likewise are on location, respectful of the literary boundaries they observe. This positioning should allow us to survey a literary whole: we do not wander beyond our present (time) into another house; we do not wander beyond what is accessible. Each chapter should be read, then, as a taking-up only of the space its author-subject constructs upon, establishing us in relation to his spatial borders. So, too, this book is purposely not a history even though the information it presents may be read for and as history. For the minds it deals with are spacious minds. These writers see and express ideas as fields of extension rather than as lines of direction, much as they feel time, and therefore history, as connectedness, as spatial touching.

Thus while there is little forward (linear) direction in Literary Architecture , there is connectedness of another sort, of fields of vision and influence which radiate, each one obeying its nature. The order of presentation the book observes may be viewed as enlarging spheres. Pater fathers forth the aesthetic concept literary architecture, in fact coining the term; and while he did not achieve imaginative literary architecture with the largeness of Hopkins, Proust, or James, his ideas encompass all that their achievements realize. Hopkins (in history Pater's pupil) represents a use of the architectural analogue at its most economical, as a tool for poetry such that his dense, highly focused art gives us both his particular world and, in a sense, the whole world. Proust represents the analogue at its largest generically, in many-volumed fiction; the architectural analogue enables him to convert linear

time, his private past and the historical past, into a literary art that does not fragment, does not go out of sight or out of reach despite its span. The architectural analogue permits time past to stay on view. James achieves a union of sorts as a writer of poetic fiction. Like Hopkins, James observes careful attention to each word as a tool for perception while using a genre of a much larger scale, his novels suggesting Proust's individual volumes. Thus we see three models of literary architecture following its articulation by Pater. And Pater's name raises another question which might be put to this study: where is John Ruskin, author of "The Poetry of Architecture," The Seven Lamps of Architecture, The Stones of Venice , in all this? I think I must answer that Ruskin is beyond, or at any rate, not within, the scope of this book. Literary Architecture is an inquiry into imaginative literature, not into art criticism or art history. And while Ruskin bequeathed to the nineteenth century a formalized means of "reading" architecture, it was Pater, not Ruskin, who applied architecture to literature by admonishing writers to use the architectural analogue in order to heal an exhausted literary art. This is not to suggest that Pater, Hopkins, Proust, and James are not each indebted to Ruskin; each is, and each pays him homage. Their relations to Ruskin are taken up as those relations seem to require, that is, when reference to Ruskin illuminates the imaginative literature we are studying.

I think of one question that remains: why these four writers and not others, such as Austen or Dickens? This is not just a period question, although it may be answered for period reasons as well as for literary reasons. The question brings us back to the primary meaning or

function of the analogue, to architecture as it represents an embodied consciousness or form of consciousness, as it represents an awareness (idea) of consciousness. The four writers I have chosen select architecture in order to give to language and thought spatial extension, to present the where-ness of ideas and thoughts. By means of the analogue, they may give, or seem to give, substance to that which is no-thing, to that which does not occupy what we call substantial space. That they do this by giving spirit-thought a dwelling place or abode[4] is appropriate: dwelling , if traced to its Indo-European root, comes from a word which means "to rise in a cloud," the "dust," "vapor," or "smoke" which makes seeable, that is, gives substantial form to, the soul or spirit, our breath-being. (The Greek thumos also comes from this root.) A dwelling—body, architecture, literature—is spirit-thought bodied, seeable, given form. Constructing a building is bringing into being ;[5] constructing a dwelling is bringing of being into seeable form . Dwellings or abodes are temporary: abode means, in fact, "the action of waiting," "a temporary remaining" before the spirit returns, with the death of the body, to its disembodied or extended state, the open field.

Pater, Hopkins, Proust, and James choose architecture as their art analogue for literature in part because it is the art form most capable of embodying thought-spirit, or essences, most capable of the conversion act. These four writers call the conversion activity translation; we may think of it also as trans -formation, of one art form into another, of being into embodied being. Austen and Dickens, on the other hand, work in a world of material or constructed equivalents—architecture and politics, architecture and character, and so forth—with-

out converting either the material into the immaterial or the immaterial into the material and thus without doing or describing the trans-form act. Their fiction, as a consequence, does not show the fullest use or reach of the architectural analogue, nor does it offer to us a methodology for understanding the profound beauty and significance of literary architecture. Pater, Hopkins, Proust, and James, to the contrary, push the analogue to its perceptual limits. I choose them, therefore, for the particular largeness of their visions as they achieve form in great literature. That they write within a fifty-year spread is no coincidence: to writers more and more fearful of disappearance not only of the temporal past but of familiar concepts of identity (and such are those writing toward the close of the nineteenth century and on into the first decades of the twentieth), architecture provides a means of preserving or memorializing the past, and identity, even as it provides for the transformation of that past and of being into literary art. Literary architecture celebrates the perceiving mind of the self; but it does so never at the expense of the universe or whole, never to the exclusion of the world.

I—

LITERARY ARCHITECTURE:

WALTER HORATIO PATER

2

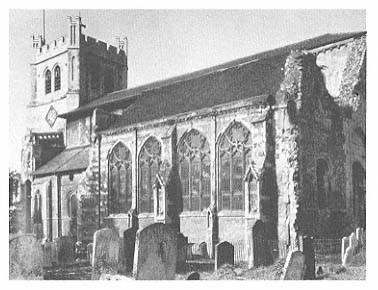

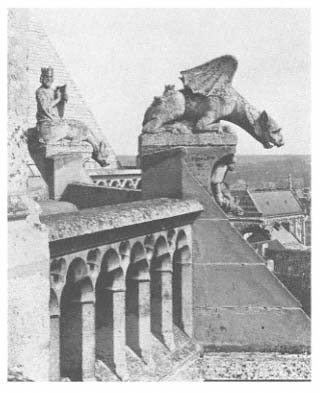

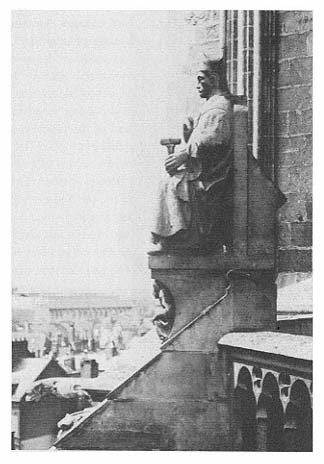

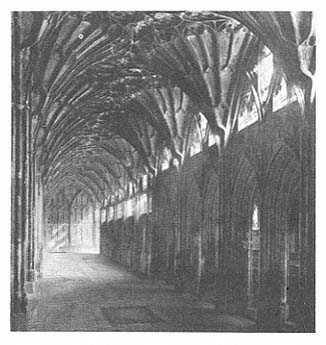

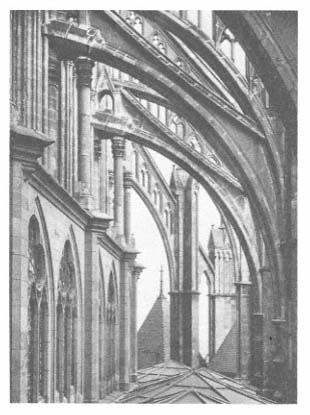

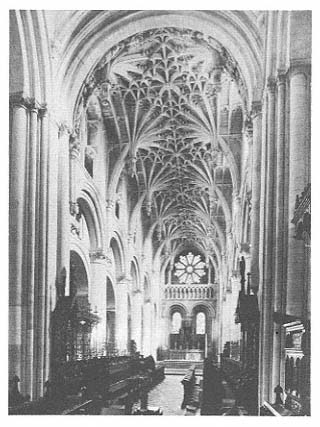

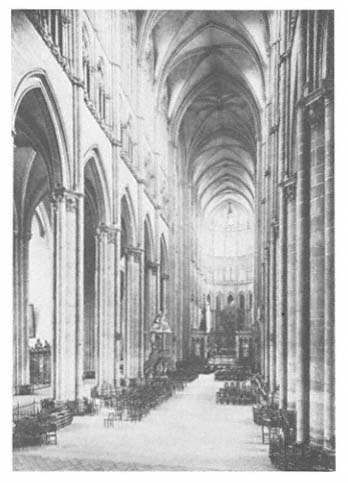

The literary architecture of association: Waltham Abbey leads Pater to

conjure history and rule. Stone, for Pater, was composed of "minute dead

bodies." Pater writes, "In architecture, close as it is to men's lives and

their history, the visible result of time is a large factor in the realised

aesthetic value, and what a true architect will always trust to." Here, in

Waltham Abbey we can see the visible result of time transform

architecture into organic nature. (South Chapel, Waltham Abbey)

One—

Pater's Rooms:

Concepts of Literary Architecture

Several years after Walter Pater's death, the anonymous "F," presumably a student of Pater's at Oxford, wrote a modest and suitably quiet memoir of his don, not a tribute properly, but more a brief sketch appropriately drawn just before the twentieth century foreclosed the Victorian era. The short reflection, called "In Pater's Rooms," includes only four paragraphs, each topically discrete and without connective links. The first describes the room itself, the second Pater's literary attitudes, the third his taste in architecture; the last is a single sentence conclusion remarking that although "that Oxford room" is tenanted by another, it will remain Pater's as long "as English literature lasts."[1] The opening paragraph describing Pater's lodgings begins:

The room was small, but the Gothic window with its bow enlarged it, and seemed to bring something of the outside Oxford into the chamber so small itself. The Radcliffe just a few hand-breadths away from the pane, the towers and the crockets of All Souls' beyond, and to the right the fair dream of St. Mary's spire, filling up the prospect with great suggestions—through the window one took in all these, and they seemed for a moment to become almost the furniture of the student's chamber.[2]

"F" then recalls his conversations with Pater, but in a tone so reminiscent of his master's that it almost betrays the motive for anonymity:

We talked of literary success, and literary prospects for a beginner of good talents, who is willing to work and wait. Dare it be said aloud? most of the modern minor poets might be using their endowments better in writing prose in this "prose age"; the same qualities that minister to a tardy mediocrity in poetry and the world of imagination, would develop grace and artistic finish in prose, the world of fact, which sorely needs to be more than fact, if it is not to be less than truth.[3]

With what seems a careless innocence and ease, "F" has described and synthesized complexities of thought Pater himself was at pains to express and document throughout his literary career. Our concerns now are those transitions "F" omits or, rather, presumes: what relationship might something so seemingly peripheral as Pater's rooms have to his literary and aesthetic values, and what, in turn, do those values have to do with architectural style?

"F," obviously familiar with Pater's fiction, permits of the suggestion that to Pater rooms were the externalized configurations of internal consciousness, descriptive not only of the quality and structure of minds but filled with a metaphoric furniture of thought derived from particular sensuous experience of an outside world as it intruded through windows and doors, making its impress felt. Pater himself had written:

Into the mind sensitive to "form," a flood of random sounds, colours, incidents, is ever penetrating from the world without, to become, by sympathetic selection, a part of its very structure, and, in turn, the visible vesture and expression of that other world it sees so steadily within.[4]

It is difficult for any reader of Pater not to conjure up the rooms which open up in his fictional writings, the se-

questered attic of Sebastian van Storck, the Rococo-frescoed halls of Antony Watteau, even the spare cell of the Prior Saint-Jean. But more elusive is the relevance of a mind-room equation to Pater's larger literary aesthetic. It is no secret that the aging Pater, in his essay "Style," made explicit the requirements for good and great literature:

Given the conditions I have tried to explain as constituting good art;—then, if it be devoted further to the increase of men's happiness, to the redemption of the oppressed, or the enlargement of our sympathies with each other, or to such presentment of new or old truth about ourselves and our relation to the world as may ennoble and fortify us in our sojourn here, or immediately, as with Dante, to the glory of God, it will be also great art; if, over and above those qualities I summed up as mind and soul—that colour and mystic perfume, and that reasonable structure, it has something of the soul of humanity in it, and finds its logical, architectural place, in the great structure of human life.[5]

The passage announces Pater's controversial break from stylistic considerations to substantive ones, those concerning the subject matter of literature and its scope; but what is important for us here are Pater's requirements and the terms in which he couches them. "F" suggests at least one reason for Pater's notorious volte-face in the "Style" essay: presumably, Pater saw what "F" calls a "tardy mediocrity" in modern imaginative literature. While "tardy" sounds like Pater, his own terms are rather different, in slight ways and yet momentously. After noting a quality of mind which, characteristically nineteenth century, is "little susceptible to restraint" and yields "lawless verse," Pater condemns what he terms removable decoration in all literature for having a "narcotic force . . . upon the negligent intelligence to which

any diversion , literally, is welcome, any vagrant intruder, because one can go wandering away with it from the immediate subject."[6] As remedy, Pater makes his request that literary style have two properties, "mind" and "soul."

By mind, the literary artist reaches us, through static and objective indications of design in his work, legible to all. By soul, he reaches us, somewhat capriciously perhaps, one and not another, through vagrant sympathy and a kind of immediate contact.[7]

Mind, however, Pater also calls architectural conception, and its literary effect is curative:

The otiose, the facile, surplusage: why are these abhorrent to the true literary artist, except because in literary as in all other art, structure is all-important, felt, or painfully missed, everywhere?—that architectural conception of a work, which foresees the end in the beginning and never loses sight of it, and in every part is conscious of all the rest, till the last sentence does but, with undiminished vigour, unfold and justify the first—a condition of literary art, which . . . I shall call the necessity of mind in style.[8]

Mind and soul fused Pater calls literary architecture. In literary architecture, the soul of style, while important, affords only secondary colorations, picturesque ones at that, the light and shade, a literary genius loci of atmosphere, playing on and around literature's overriding architectural structure:

For the literary architecture, if it is to be rich and expressive, involves not only foresight of the end in the beginning, but also development or growth of design, in the process of execution, with many irregularities, surprises, and afterthoughts; the contingent as well as the necessary being subsumed under the unity of the whole. As truly, to the lack

of such architectural design . . . informing an entire, perhaps very intricate, composition, which shall be . . . true from first to last to that vision within, may be attributed those weaknesses of conscious or unconscious repetition of word, phrase, motive, or member of the whole matter, indicating . . . an original structure in thought not organically complete.[9]

After describing the literary artist's task as one of "setting joint to joint," Pater concludes the passage with a double image, stating, "The house he [the writer] has built is rather a body he has informed."[10]

For Pater, the activity of great writing is the simultaneous activity of filling—informing—and of forming, the giving of full form/idea to that which is felt, sensed, or known but which has no embodied structure prior to the art act. Literary architecture is, consequently, an alive "reasonable structure": it is a body with a soul. In this context, the building of literary architecture is a composing of pregnant forms: it is pro-creative and full of care. The architectural analogue helps the reticent Pater to speak of such artistic making without embarrassment of exposure. But more significant for Pater, the analogue enables him to suggest that all structures mean regardless of scale, place, or occasion: Pater moves, in his passage of literary architecture, from art structure to human structure to life structure, from "colour" and "structure" (architecture) to "soul" and "mind" (man) to "soul of humanity" and "structure of human life."

There are more suggestive links between the materials and the structures of literary art. The mind-structure analogue—either Pater's room as "F" describes it or Pater's literary architecture—offers a distinct notion of inside and outside: the room "seemed to bring something of the outside Oxford into the chamber so small

itself." Some correspondence, even if only in the most literal sense, exists between inside and outside, between a room and its "vagrant intruders." This correspondence has fruitful consequences; the trans-parent window enlarges the inner room-world, informing it by and with the external prospect, which itself is already full of "great suggestions": "through the window one took in all these, and they seemed for a moment to become almost the furniture of the student's chamber."[11] The activity "F" describes here is one of receiving, the artistic activity of influence or impression. For the activity of creating literary architecture, the direction changes to one of expression. One comes to expect Pater's announcement, made later, in his "Style" essay: "Well! all language involves translation from inward to outward."[12] Figuratively, literary architecture enables transmission, if not translation, from the inside out, and it also provides checks to lawlessness: intruders cannot enter wantonly, nor can what is inside grow wildly without structural checks.

As easy as this notion of inside and outside is, it is worthwhile to look at it for another moment, since the idea persists, and has persisted throughout Pater's fictional and critical writings as well as throughout the work of others who also select architecture as their art model. The imprisoned self in the one-time suppressed "Conclusion" of Pater's The Renaissance —suffering the intractability of a relativist aesthetic—also occupies a room of sorts. We cannot help but recall Tennyson's woeful "Soul" locked within "The Palace of Art"; but Pater has morbidly reduced palace to a chamber of Poelike terror, just as elsewhere his rooms shrink still further to single cells, biologically and architecturally more minute and limiting:

At first sight experience seems to bury us under a flood of external objects, pressing upon us with a sharp and importunate reality, calling us out of ourselves in a thousand forms of action. But when reflexion begins to play upon those objects they are dissipated under its influence . . . the whole scope of observation is dwarfed into the narrow chamber of the individual mind. Experience, already reduced to a group of impressions, is ringed round for each one of us by that thick wall of personality through which no real voice has ever pierced on its way to us, or from us to that which we can only conjecture to be without. Every one of those impressions is the impression of the individual in his isolation, each mind keeping as a solitary prisoner its own dream of a world.[13]

Pater's "Conclusion" makes the otherwise neutral word "translation" from the "Style" essay appear tinged with optimism and therefore, appropriately, encouraging. In suggesting the possibility of movement from the inward chamber to the outside, Pater, in "Style," is also suggesting the possibility of creating viable literary works of art. His summation—that great literature "finds its logical, architectural place, in the great structure of human life"[14] —so expands the cloistral chamber of The Renaissance as to offer a positive alternative to the philosophic and psychological confines of a relativistic and, by default, virtually solipsistic existence.

It is important, then, that Pater's anonymous elegist concludes his memoir with a recount of Pater's taste in architecture. Out of "F's" rendering Pater looms as no less a Victorian man of letters for participating in the charged architectural controversies persisting throughout his century. According to "F," Pater felt that

things of quite the first rank had been produced in the 'seventies and 'eighties: gross and flagrant mistakes had been

made in modern Gothic and Renaissance; but churches and public buildings had lately been built as perfect in their way as the work of the twelfth or fourteenth century. He instanced St. Philips Church, which lies behind the London Hospital.[15]

"F" goes on to say that Pater's thinking about Whitechapel "led him to dwell with enthusiasm upon the perfect Norman of Waltham Abbey, that to the death of Harold, and that to the 'stirring, interesting writing of Professor Freeman, which I love to read.'"[16] [Plate 2] The attention paid here to Pater's stylistic sympathies throws into relief "F's" opening description of his don's rooms: no longer is it incidental that Pater's window was Gothic or that the metaphoric furniture of the room was towers and church-steeples of pre-Gothic (Norman), Gothic, and Gothic-Revival Oxford. The Gothic window qualifies Pater's vision: history and philosophy, political and aesthetic, cling to Gothic where they would not cling to buildings from another period or of a differing "mental style"; in turn, the towers and steeples cluttering Pater's room assume symbolic value, recalling to a reader religious and academic collisions of the past, perhaps the scarring Tractarian upheaval or the subsequent secularizing of an Oxford whose dons in the 1870s could relinquish celibacy vows. For Pater, too, as "F" well knew, architectural style triggers, intentionally, an associative remembering, buildings themselves sustaining qualities of expressive art-forms: one building beckons another, Whitechapel the Norman Waltham Abbey; Waltham Abbey then conjures history and rule, namely Harold, who finally solicits from Pater's memory affection for one man's writing, that of Professor Freeman.[17]

"F's" brief service to Pater's memory in 1899 managed to imply a great deal while saying little. In a few para-

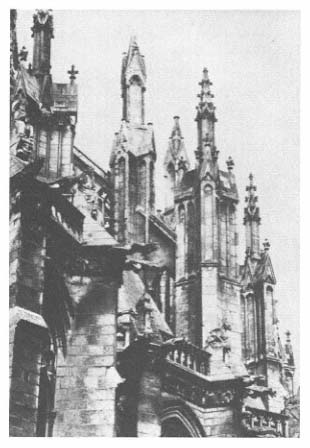

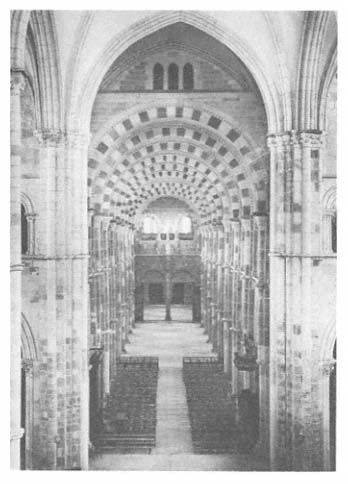

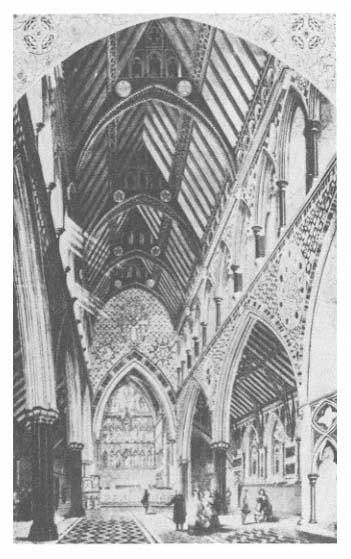

graphs the associative pattern comes clear, and reminiscence turns upon a coupling of architecture with literature. This, in fact, is one extraordinary service Pater's concept of literary architecture performs: in every kind of writing that Pater undertook, he celebrates the power for memory and association that architecture bestows. If a generic architecture (home, church, school), or architecture still more abstracted into sheer structure (rooms), has implications for Pater's conception of literature, so, too, do particular manifestations of architecture. On a formalistic level alone, qualities resplendent in architecture specifically Gothic find literary parallels in Pater's essays. Craftsmanship in Gothic construction, architectural or literary, is meant to suggest the imposition of an artist's individuality, his tastes and skill, onto the structure he builds as he translates outward his private vision. The "irregularities" and "surprises" of Gothic cornices and capitals, the "intricacies" of carved ornament or tracery inseparable in function from church structure—all these find reciprocal terms or characteristics in the literary architecture that Pater delicately evokes and qualifies in his essay "Style." [Plate 3] If we return, for a brief moment, to Pater's own prose, in this instance to the passage of advice regarding literary architecture, we see that Pater himself carries out what he admonishes others to do:

For the literary architecture, if it is to be rich and expressive, involves not only foresight of the end in the beginning, but also development or growth of design, in the process of execution, with many irregularities, surprises, and afterthoughts; the contingent as well as the necessary being subsumed under the unity of the whole. As truly, to the lack of such architectural design . . . informing an entire, perhaps very

intricate, composition, which shall be true . . . from first to last to that vision within, may be attributed those weaknesses . . . indicating . . . an original structure in thought not organically complete.[18]

"If it is to be rich and expressive" comes as an interruption or "surprise," "the contingent as well as the necessary" as an "afterthought" to the first part of the sentence, "forming an entire, perhaps very intricate, composition" carrying an intricacy or detail within it.

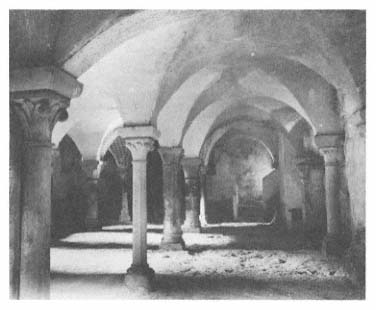

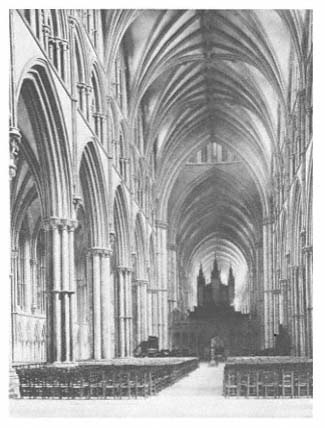

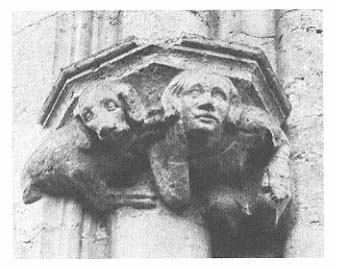

It is misleading, however, it is all too easy, to index Pater's writing by a metaphoric system in which preferences in architectural style denote equivalent preferences in history, philosophy, or aesthetics. This is to reduce Pater's oftentimes protean values to one scheme, implicitly and temporally consistent. It is much more profitable to recognize that the architectural door which swings wide on an historical past and on literary style also swings wide on private memory, and that it postulates something about its interiors: they are accessible, recoverable, describable. In one of his Imaginary Portraits , "Emerald Uthwart," for instance, a reader may "dive" with the Oxford student Emerald along a "passage," not, as we might expect, of old buildings, but of "old builders."[19] [Plate 4] In the same way, Pater may move, by induction or deduction, from literal or imaginary edifices, so as to reconstruct, often fictionally, a past made replete through creative rather than historical detailing. In such a context, Piranesian ruins (or empty spaces where buildings once stood) provide materia and creating room for a writer of historical fiction or philosophic fiction. Shifts of time—from a Rome in rubble to a whole Rome before its fall, and so to a nineteenth-century-recon-

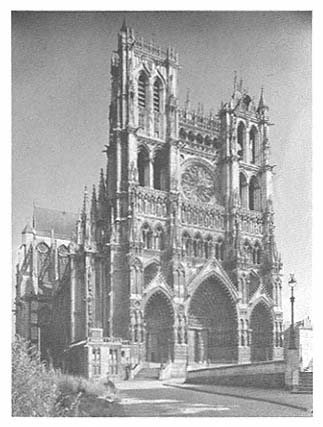

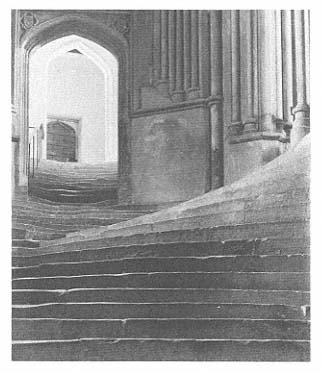

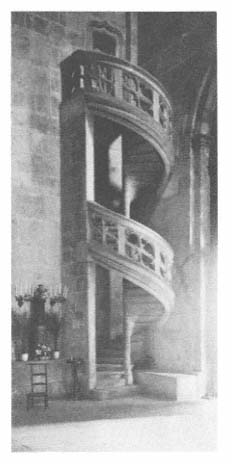

3

"Irregularities, surprises, afterthoughts": "just-jotting"

rhythms of the Gothic. It is not difficult to see how inspiring

the Gothic was, with its staccato intricacies and its pride of

territory. Such are the rhythms which attract Hopkins as well

as Pater. (Notre-Dame d'Amiens)

structed Rome (as in Marius the Epicurean )—show how effective architecture can be, as a provocation to synoptic fictions. Finally, a modern reader may look at "The Child in the House" or any other of the Imaginary Portraits , with an eye to architectural structure. In "Child," for instance, the "design"[20] which best describes "the process of brain building" is, by now predictably, the home of the story's central character, Florian Deleal: that structure then suggests mind-design, cognitive growth, nostalgia; and by implication, in accord with a terminology to be found in the aesthetic essays, it also suggests Pater's ideas about memory and fiction- or poetry-making. Such internal architecture does more than reveal the character's mind: through a perfect matching of thought to language or language to thought, the retreated writer himself goes public. Pater's careful literary monuments—his literary art entire—may be visited by all readers. Each may witness there the activity of growth itself of what would otherwise remain hidden, the private trains of thought (open sets) and of memory (closed sets) of the artist. Here we find another aspect of Pater's achievement: through his literary architecture readers may see the boundaries—the walls—of the artist's understanding and experience of the world at the same time that we see those limitations transformed into structures of meaning. Through creative expression Pater exposes the structural demarcations of his own collapsed life. These processes are tracked in detail, not only (subterraneanly) in his own fictions, but throughout his critical and historical writings. In the following section I shall concentrate on the interplay between fiction, architecture, and memory, especially as it was inherited by Pater out of a long tradition, and was then transformed by him.

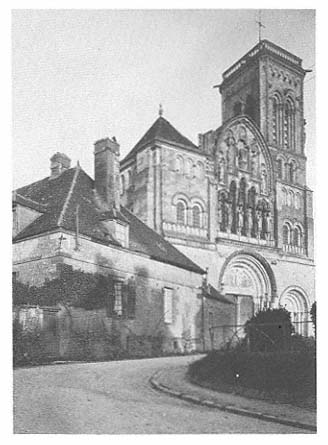

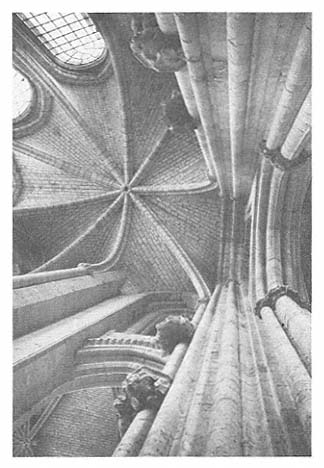

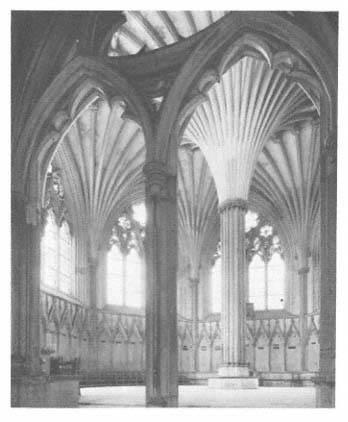

4

The mind of literary architecture: diving along a passage of old builders .

Here we see the world of time recorded as architectural style. (Vézelay)

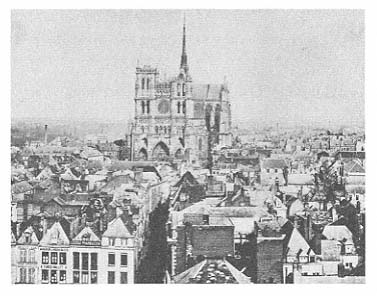

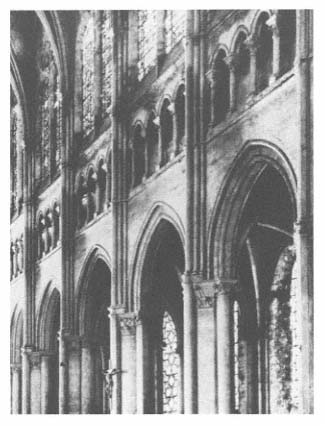

5

Notre-Dame d'Amiens: "L'église ogivale par excellence," Pater

claims in his essay "Notre-Dame d'Amiens." Pater sees in the

"queen" of Gothic churches "certain impressive metaphysical

and moral ideas, a sort of popular scholastic philosophy, or as

if it were the virtues and vices Aristotle defines, or the

characters of Theophrastus, translated into stone."

Two—

The Ars Memoria Tradition:

Architecture and Pater's Fiction

I come to the fields and spacious palaces of memory (campos et lata praetoria memoriae) where are the treasures of innumerable images, brought into it from things of all sorts perceived by the senses. There is stored up, whatever besides we think, either by enlarging or diminishing, or any other way varying those things which the sense hath come to; and whatever else . . . which forgetfulness hath not yet swallowed up and buried. When I enter there, I require instantly what I will to be brought forth, and something instantly comes.

Augustine

Our susceptibilities, the discovery of our powers, manifold experiences . . . belong to this or that other well-remembered place in the material habitation . . . and the early habitation thus gradually becomes a sort of material shrine or sanctuary of sentiment; a system of visible symbolism interweaves itself through all our thoughts and passions; and irresistibly, little shapes, voices, accidents—the angle at which the sun in the morning fell on the pillow—become parts of the great chain wherewith we are bound.

Walter Pater

How indelibly [sensible things] affect us; with what capricious attractions and associations they figure themselves on the white paper, the smooth wax, of our ingenuous souls, as "with lead in the rock forever," giving form and feature, and as it were assigned house-room in our memory, to early experiences of feeling and thought, which abide with us ever afterwards, thus, and not otherwise.

Walter Pater

Despite the lapse of time and the differences in tradition, it may be said that Pater and Augustine share assumptions about memory and place. For both, memory becomes a collection of mental images drawn from sense impressions and extended in time, linked associatively to place and figuring as edifices in the mind, or with Pater, edifices projected from the mental into material abodes. Pater, like Augustine, goes to places for their reconstructive value: "The quiet spaciousness of the place is itself like a meditation, an 'act of recollection,' and clears away the confusions of the heart."[21] But while Augustine summons up memories by an act of will, Pater and his fictional characters more often passively yield themselves to the influences of place and to the memories there associated. It is assumed that associations may be ordered in these memory store-houses, and that recollection of specific images or ideas, temporarily forgotten or buried, may be the aim of an associative ordering. Yet for Pater, order (or lack thereof) and association function, in ad-

dition, for a descriptive purpose, so as to portray what Pater calls the process of brain-building . If it is—and it is—unfair to say that Augustine is not concerned with cognitive processes, it would be as unfair to say that such was Pater's only concern. That "white paper" should figure as the recipient of sense impressions is far from incidental. It is here perhaps that Pater's purpose differs most widely from Augustine's: whereas Augustine reconstructs religious and meditative experience, Pater is concerned to suggest the active art of writing and creating. Sense images are recorded indelibly within the rooms of memory; but just as indelibly, and very much to the purpose for Pater, they may be recorded verbally as literary art. Quite simply, when Pater describes buildings—be they Vézelay or Notre Dame d'Amiens of his architectural histories, or else imaginative structures as in his fictions—he reciprocally talks not only about memory but about literature. Literature, by its analogous relationship to memory and architecture, comes to be defined as a process of recapituation, not only of a private past but of an historical one, what the nineteenth century might call racial, a past, as we have seen, recoverable through architectural renderings.

Pater, in his attitudes toward literature, architecture, and memory, holds assumptions and values which we shall find shared by others; and, in his own modest way, Pater attempts what flowers more fully elsewhere, especially in the subsequent literary creations of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Marcel Proust, and Henry James. Like these men after him, Pater inherits and brings together at the very least two seemingly separate and ancient traditions: the ars memoria tradition[22] which uses architecture as a quotidian structure for memory and

a convenient metaphor for the mind; and what I call the ut architectura poesis tradition which suggests that writers respect and imitate in their literary style principles of architectural construction or structure. It is important to our concerns with Pater and with the larger implications of literary architecture, that what seem to be vestiges of the classical mnemonic system, the one to which Augustine in fact subscribed, do survive in nineteenth-century architecture manuals;[23] and, perhaps to our surprise, we find that these very manuals also borrow and use poetic or linguistic terms to describe the art of architecture. In this context, then, Pater's careful argument for literary architecture—rather than a newly formulated analogy between literature and architecture—represents for literary art what might be considered a repossession or borrowing back of terms and concepts which had once been literary commonplaces but which had been used more recently to dictate not literary but architectural practice in the nineteenth century.[24]

Although Pater himself rarely addresses the relationship between architecture and memory with the seeming explicitness that his architectural mentor, John Ruskin, does in the "Lamp of Memory" section in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), for Pater as for Ruskin, architecture serves a memorial function: it recapitulates the historical past. Pater comments in "Prosper Mérimée":

In that grandiose art of building, the most national, the most tenaciously rooted of all the arts in the stable conditions of life, there [are] historical documents hardly less clearly legible than the manuscript chronicle.[25]

Once again, the analogy between architecture and literature helps Pater to describe how he and others in the

6

Memorial architecture with historical documents.

(Notre-Dame d'Amiens)

nineteenth century view buildings. While Pater and Ruskin cautiously avoid identifying the two art forms, Ruskin by remarking that one does not "read" certain building styles as one would read Milton, Pater by carefully hedging on his analogical formulation ("hardly less clearly"), the two overtly sanction the notion of shared qualities, even the belief that one art could, to use Ruskin's term, subsume the other.[26] Only with qualifications, then, does Pater agree with Ruskin that architecture, like poetry, is a "conqueror of forgetfulness."[27] If nature can no longer retain records of the past as it did for Romantic poets, architecture can. In "Emerald Uthwart," Pater, for instance, links architecture to consciousness when he conveys how King's School Canterbury records the past:

Why! the Uthwarts had scarcely had more memories than their woods, noiselessly deciduous, or than their pre-historic entirely unprogressive, unrecording fore-fathers, in or before the days of the Druids. Centuries of almost "still" life—birth, death, and the rest, as merely natural processes—had made them and their home what we find them. Centuries of conscious endeavour, on the other hand, had builded, shaped, and coloured the place, a small cell, which Emerald Uthwart was now to occupy; a place such as our most characteristic English education has rightly tended to "find itself a house" in—a place full, for those who came within its influence, of a will of its own.[28]

That there should exist a relationship between the individual and architecture as it embodies memory or the historical past, between Emerald and his school, means that there is an overlap between the aesthetic and the moral worlds. In part because architecture reveals the mind of its builders and of its period, it may impress

its philosophical and ethical values upon those who dwell in it:

The very place one is in, its stone-work, its empty spaces, invade you; invade all who belong to them . . . seem to question you masterfully as to your purpose in being here at all, amid the great memories of the past, of this school;—challenge you, so to speak, to make moral philosophy one of your acquirements, if you can, and to systematise your vagrant self; which however, will in any case be here systematised for you.[29]

Pater is quite explicit that "impressibility" is a positive quality, especially for artists, and that architecture as physical edifice or literary structure, because it impresses aesthetically, determines or contributes to the moral quality of character impressed. If architecture assumes such power for Pater, we may begin to understand and anticipate how important architecture is for literature. We do know that Pater, throughout his own aesthetical, fictional, and philosopical writings, continually chooses to describe schools, churches, homes—structures in which a kind of learning is assumed to take place. In Plato and Platonism Pater comments:

There exists some close connextion between what may be called the aesthetic qualities of the world about us and the formation of moral character, between aesthetics and ethics. Wherever people have been inclined to lay stress on the colouring, for instance, cheerful or otherwise, of the walls of the room where children learn to read, as though that had something to do with the colouring of their minds; on the possible moral effect of the beautiful ancient buildings of some of our own schools and colleges, on the building of character, in any way, through the eye and ear; there the spirit of Plato has been understood . . . [as has] the connexion between moral character and matters of poetry and art.[30]

Memory housed architecturally becomes, thus, dynamic, to just the extent that its inhabitants become passively receptive.[31] The seesaw of static against kinetic, rest against motion, mind against soul, structure against inhabitant (not to mention structure against weather, territory against space) is endlessly in play; and just as in literary style, given optimum conditions, the passive and active coexist, so in the artistic personality the two work harmoniously if possible. In this way, an artist impressed may in turn construct or reconstruct, through memory, either the process of being impressed (his own growth), or else merely his particular, reflected, sense of an external world (his own decay).

It is possible to read Pater's fiction, then, in such a way as to take into account memory images and architectural structures as analogically suggestive, one of the other. As an example, we may look at a few passages from "The Child in the House," if only for the richness of interpretative possibilities. The story begins:

As Florian Deleal walked, one hot afternoon, he overtook by the wayside a poor aged man, and, as he seemed weary with the road, helped him on with the burden which he carried, a certain distance. And as the man told his story, it chanced that he named the place, a little place in the neighbourhood of a great city, where Florian had passed his earliest years, but which he had never seen since, and, the story told, went forward on his journey comforted. And that night, like a reward for his pity, a dream of that place came to Florian, a dream which did for him the office of the finer sort of memory, bringing its object to mind with a great clearness, yet, as sometimes happens in dreams, raised a little above itself, and above ordinary retrospect.[32]

The initial relationship between dream and memory[33]

is based on place association. Pater sets up an associative chain in which there exists ostensible movement from parable, Bunyan-esque and general, to the particular or idiosyncratic, Florian Deleal. The house recalled is "raised" by dream rather than memory "above ordinary retrospect." After the passage just quoted, Florian, in the act of recalling (as distinct from the act of dreaming) places himself inside the house and thus identifies himself with soul and with the passive. He does this in order to describe an active process ("brain-building"):

This accident of his dream was just the thing needed for the beginning of a certain design he then had in view, the noting, namely, of some things in the story of his spirit—in that process of brain-building by which we are, each one of us, what we are.[34]

Florian's verbal constructions betray, however, his assumptions about cognitive growth: they register passivity, that is, the refusal to take responsibility for growth of self. "With the image of the place so clear and favourable upon him, he fell to thinking of himself therein, and how his thoughts had grown up to him."[35] Florian then describes the old house:

The old-fashioned, low wainscoting went round the rooms, and up the staircase with carved balusters and shadowy angles, landing half-way up at a broad window, with a swallow's nest below the sill, and the blossom on an old pear-tree showing across it in late April, against the blue, below which the perfumed juice of the rind of fallen fruit in autumn was so fresh. At the next turning came the closet which held on its deep shelves the best china. Little angel faces and reedy flutings stood out round the fireplace of the children's room. And on the top of the house, above the large attic, where the white mice ran in the twilight—an infinite, unexplored wonderland

of childish treasures, glass beads, empty scent-bottles still sweet, thrum of coloured silks, among its lumber—a flat space of roof, railed round, gave a view of the neighboring steeples; for the house, as I said, stood near a great city, which sent up heavenwards, over the twisting weather-vanes, not seldom, its bed of rolling cloud and smoke, touched with storm or sunshine.[36]

The ordering of association (which, incidentally, involves all the senses, not only sight) in this passage depends at first on the wainscoting which leads Florian around a spatially conceived house. Florian's tour ends, finally, above the attic, outside, on the roof-top. The physical movement as such is one of ascent, not descent, to bird's nest, to pear tree, finally to attic and sky. Outside is something "wonderful, infinite and unexplored," while what is inside, by default, is relegated to the known and finite. The roof-top scene curiously repeats or imitates the aspiring or upward motion of Florian's physical progress through the house: "sent up heavenwards" are the cloud and smoke of the city mingled with natural atmosphere, storm and, alternatively, sunshine. The view reflects, rather oddly, Pater's conspicuously un-Ruskinian tolerance of the city with its effluvia, its fog, and smoke.

Architecture provides, then, not only a design establishing conditions of inside and out, but one making possible a direction of influences and soul growth. As home, it also suggests origins of feelings or moods as well as the beginnings of perceptual clarity: the distinctness between inner and outer yields to a fusion or blurring, which is how growth starts. "Inward and outward," so Florian says, are "woven through and through each other into one inextricable texture," half qualities from "the wood and the bricks," the other half "mere

soul-stuff."[37] It is interesting that association patterns elsewhere in the story, those not linked to the architectural device "house," also stop or end at "church," and that the penultimate stop before that conclusion is invariably "home." We begin to think that there is only one way to church. When association connects itself with structure, in this instance the church in the city, its movement once again becomes pyramidal, as if it were graphing spiritualization in space:

The coming and going of the travellers to the town along the way, the shadow of the streets, the sudden breath of the neighbouring gardens, the singular brightness of bright weather there, its singular darknesses which linked themselves in his mind to certain engraved illustrations in the old big Bible at home, the coolness of the dark, cavernous shops around the great church, with its giddy winding stair up to the pigeons and the bells. . . .[38]

Associative patterns based on buildings are not ordered temporally (there is no passage of time within Florian's home) but depend, rather, on spatial organization. Value judgments, too, link themselves to these spatial arrangements, the spiritual being above the attic, the soul within the house always escaping outward to spiritual light let in by windows or streaming onto the roof-top.

Pater's patterns of association, as we might fairly expect, do vary in important ways from those patterns used in classical memory systems.[39] Nonetheless, Pater's variations, while in some ways peculiar to him, may also suggest other services which the architectural analogy might provide for writers either familiar with Pater's work or inheriting a similar past. In classical theory,

architecture as an artificial memory model is used most generally by a rhetor who places objects within a conceptualized and particularized structure in an order so that he may remember specific points or ideas. The associations proceed then from the arbitrarily placed objects. In Pater's fiction, however, individual objects placed in specific locations, though they trigger individual memories, more often function symbolically, so that a reader may gather from them, or adumbrate, meanings he wishes them to contain. Whereas we might say that the rhetor's placement of an object usually demands a coherence and order subservient to his argument, Pater's associations generally do not presuppose a direction logically based or logically maneuvered to persuasive ends. And whereas it seems that the order of steps in this artificial memory system is controlled by the carefully crafted model, in Pater the order, and what connects two things, is found in the thing itself as often as it is found in the structure. In other words, the object as symbol frequently contains that which generates recall of the next. It is true, however, that in Pater's fiction the architectural structures are in fact as arbitrary and idiosyncratic as associative ramblings would be without those structures. There seems to be a pretence in Pater—that architectural orderings involve a reduction of randomness, and a consequent diminishing, in importance of the specific things mentioned. When the motive in Pater's associative memory system is to emphasize the final step, as is generally the case with a rhetor, his structure is generally pyramidal; however, when the associative links themselves are each more important than any last step or conclusion, Pater refrains from using a

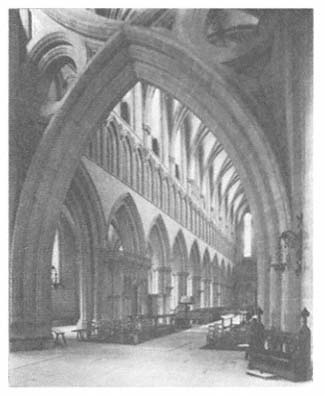

7

Rounding a corner of the mind: La Madeleine, Vézelay.

spatial structure having a top and a bottom. Indeed, it is not always clear that these structures have even an inside and an outside.

Pater insists that literary architecture should "foresee the end in the beginning," and this is a prescription which we shall encounter again and again as we read other writers who select an architectural analogue.[40] Foresight, in Pater's sense, is also characteristic of classical memory systems in which the end, or argumentative point, is preconceived and then broken down into a series of logical steps. In Pater's particular associative thought patterns, one similarly senses that he foresees the end of his associations in the beginning, that the enumeration of parts is a calculated elaboration of the points making up the whole. But for Pater, unlike classical rhetors, the component parts leading to the end never equal the end, and the last point is generally an added element that the constituent parts did not contain or do not produce. A holistic view of this sort allows Pater a retreat from an empirical position while in fact he has tempted the reader with a style seemingly empiricist, that is, the supposedly open-ended associative process. For Pater, the architectural device for associative memory has the advantage of avoiding the empiricist's bind of causality, seeming instead to establish fixed points and yet without becoming didactic and Cartesian. Whereas relativistic or impressionistic philosophy presumes to record impressions as they occur, without concern for the end, Pater's associations actually exist within a closed system in which the end is not only foreseen but prescribed.

From Pater's comments in "Style," if not indeed (and more compellingly) from his prose itself, one can see how he was attracted by stasis: a writer should "repeat"

8

"Cliffs of quarried and carved stone . . . radix de terra sitienti. " For Proust,

this would be an example of "church epitomizing town, representing it

speaking of it and for it to the horizon." (Notre-Dame d'Amiens)

his steps only that he may give the reader a sense of secure and restful progress, readjusting mere assonances even, that they may soothe the reader, or at least not interrupt him on his way.[41]

Pater, it seems, slows down the reader almost so as to distract attention from the end, and so to expand the spiritual qualities of the associative components. Superficially then, the soul of style dominates the mind, camouflaging the clear outline, the stated but meticulously disguised limits of Pater's epistemological system. One thinks that Pater takes a dynamic system and freezes it; and he does that, it is true, when he talks about holding onto the moment of flux and expanding it. But more often than not, the entire system is one of rest (that flux is within the "narrow chamber"), and the dynamic that exists does so within strict limits. Pater's alternation between motion and rest seems to direct us away from his thought peripheries, those severely limited and limiting epistemological assumptions, and force us back into the midst of his elaborations, of what seem now Pater's fetish, his self-consuming (and self-deceiving?) processes. That stasis, or rest, does in fact circumscribe the entire system is something Pater fears, just as he and his characters fear being closed in. Thus there exists always a break through to open windows, to skies, to that which is spiritually transcendent, anything which distracts from or invigorates a deterministic, generally pessimistic world view.[42] All processes of ordering, be they through architectural memory or literary architecture or both, support what cannot but appear as a conservative aesthetic, an aesthetic allowing for growth only in recapitulation.

The arrested beauty of Pater's literary architecture registers his inspired transformation of his own limita-

9

"It is a spare, rather sad world at most times that

Notre-Dame d'Amiens thus broods over."

tions into art: sensuous experience for Pater never occurs in an external or natural world, but manages, nonetheless, to live within his careful language of interiors. In this way Pater's language itself is an accommodation to his fear of unbounded energy or natural weather. In passages where his characters are out of doors, there invariably occurs a retreat; and yet this is not surprising given Pater's view of the world and of the function of literature. To Pater, all fine art should be turned to "for a refuge, a sort of cloistral refuge, from a certain vulgarity in the actual world."[43] Pater's literary architecture—whether the structure of his sentences, the houses in his fictions, or the monuments in his histories—look out over his world of pain and protect him from it just as they magically let us see what he fears. Pater concludes his essay on Notre-Dame d'Amiens with just this marriage:

It is a spare, rather sad world at most times that Notre-Dame d'Amiens thus broods over; a country with little else to be proud of; the sort of world, in fact, which makes the range of conceptions embodied in these cliffs of quarried and carved stone all the more welcome as a hopeful complement to the meagreness of most people's present existence, and its apparent ending in a sparely built coffin under the flinty soil, and grey, driving sea-winds. In Notre-Dame, therefore, and her sisters, there is not only a-common method of construction, a single definable type, different from that of other French latitudes, but a correspondent sentiment also; something which speaks, amid an immense achievement just here of what is beautiful and great, of the necessity of an immense effort in the natural course of things, of what you may see quaintly designed in one of those hieroglyphic carvings—radix de terra sitienti : "a root out of a dry ground."[44]

Here the peculiar pain of Pater discovers expression in his

odd, transitive move from a situation open to his own pre-established and closed view of the world, from an overview to a coffin. And yet Pater's built literary world is informing and in forming; he offers to those after him an economical device for speaking of relation—between self and world, mind and other—in terms of space and place, that is, as we actually experience and recall our being, our life, our death: the spatial richness of architectural structure as it governs our physical experience of the world and our language-thought of spatial experience about that world.

II—

"THE POETRY OF ARCHITECTURE":

GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS

10

"The strong and noble inscape." Gerard Manley Hopkins:

Tracery of a Gothic Window.

One—

Architecture and Terminology

Stress, instress, scape, inscape, arch-inscape, sprung, pitch, centre-hung, end-hung, moulding, proportion, structure, construction, design —the literary terminology of Gerard Manley Hopkins is very familiar. While we know that Pater was one of Hopkins's teachers at Oxford, Hopkins's terms, at least at first glance, might seem to have little to do with the literary architecture of his don. That they are idiosyncratic and defy simple definition is well known; and that they have called for careful, oftentimes conflicting, interpretations by critics concedes both their potency and their enigmatic richness. I should like, nonetheless, to look at these terms again and to ask two simple questions: what do these terms have in common? and where do they come from?

Stress, sprung seem mechanical, pitch musical, moulding sculptural; scape, like instress and inscape , seems Hopkins's own, whereas proportion, structure, construction, design are so general as to be applicable to nearly any of the arts. Only centre-hung and end-hung remain. And these Hopkins defines explicitly:

It strikes me that these two kinds of action and of drama thence arising are like two kinds of tracery, which have, I dare say, names; the one in which the tracery seems like so much of a pattern cut out bodily by the hood of the arch from an infinite pattern; the other in which it is sprung from the hood or arch itself and would fall to pieces without it. It is like tapestry and a

picture, like a pageant and a scene. And I call the one kind of composition end-hung and the other centre-hung and say that your play is not centre-hung enough. Now you see.[1]

Centre-hung and end-hung are architectural terms; and the art analogue Hopkins sets for literary drama is architecture. This ought to make us look at a book which Hopkins casually mentions in his early Diaries. Unfortunately Hopkins does not identify it, and we cannot identify it ourselves. But we know that it was a glossary of architectural terms and we may legitimately suppose that it was something like John Parker's A Glossary of Terms used in Grecian, Roman, Italian and Gothic Architecture,[2] if indeed it was not that very book. We come across it when Hopkins is discussing architectural motifs.

Transoms in Decorated and Early English. In former not infrequently found for the purpose which they were intended to answer, before they became in Perpendicular only ornamental, viz. to give strength to mullions of tall windows. So also in Decorated where they are quite common in domestic architecture, but very rare in ecclesiastical. The Glossary mentions two examples. In long windows however as in towers (e.g. S. Mary's, Oxford) they are not uncommon. Their evidently deliberate rejection in ordinarily proportioned windows by the Decorated architects ought to be decisive against them.

(JP, 14, 1863–64)

Do the remaining terms also derive from or refer to architecture? If we turn to Parker, perhaps the one Hopkins had cited, we find the following:

stress: the result in a member of the action of external forces upon it. For example: tensile stress is the stress due to the action of two external forces tending to pull the

constituents of a member apart: comprehensive stress is the stress due to the action of two external forces tending to push the constituents of a member together.

scape: another term used for a column shaft, or for the apophyge, of a column.

arch: an arrangement of wedge-shaped masonry, or bricks, built over an opening in a wall, in such a manner that the arch is self-supporting and will also take weight imposed on it.

sprung, springer, springing, springing line, springing point: the point from which an arch springs, from the top of an abutment.

pitch: the angle at which a roof slopes.

moulding: a general term applied to all the varieties of outline or contour given to the angles of the various subordinate parts and features of buildings, whether projections of cavities, such as cornices, capitals, bases, door and window jambs and heads, etc.

As for proportion , Hopkins's use of the term rests explicitly on an analogy with architecture, as we see when he remarks on English and Italian sonnet form:

Now in the form of any work of art the intrinsic measurements, the proportions, that is, of the parts to one another and to the whole, are no doubt the principal point, but still the extrinsic measurements, the absolute quantity or size goes for something. Thus supposing in the Doric Order the Parthenon to be the standard of perfection, then if the columns of the Parthenon have so many semidiameters or modules to their height, the architrave so many, and so on these will be the typical proportions. But if a building is raised on a notably greater scale it will be found that these proportions for the columns and the rest are no longer satisfactory, so that one of two things—either the proportions must be changed or the Order abandoned. Now if the Italian sonnet is one of the most

successful forms of composition known, as it is reckoned to be, its proportions, inward and outward, must be pretty near perfection.

(CD, 85–86, 1881)

Hopkins talks of design (which he elsewhere equates with pattern and inscape in poetry) when he discusses the use of dialect:

but its [dialect's] lawful charm and use I take to be this, that it sort of guarantees the spontaneousness of the thought and puts you in the position to appraise it on its merits as coming from nature and not books and education. It heightens one's admiration for a phrase just as in architecture it heightens one's admiration of a design to know that it is old work, not new: in itself the design is the same but as taken together with the designer and his merit this circumstance makes a world of difference.

(LB, 87–88, 1879)

Thus we begin to see that while the terms Hopkins uses may have primary meanings in other arts, they all have architectural ones as well. Of the term which remain, structure and construction are architectonic by definition. The only terms which do not occur in architectural glossaries of the time are Hopkins's own coinages inscape and instress . And in the context we have established, Hopkins's addition of the prefix in to scape and stress only serves to emphasize the architectural meanings, since it directs attention to notions of interior and exterior, inside and outside. For Hopkins, constructed and organic things both have insides and outsides, even man. The body may have, metaphorically at least, its structural ins and outs, its

. . . rack of ribs; the scooped flank; lank

Rope-over thigh; knee-nave; and barrelled shank—

Head and foot, shoulder and shank—(Poem 71)

And its spiritual or emotional self must perforce respect the inhabited, structural boundaries: "Man's mounting spirit in his bone-house, mean house, dwells—" (Poem 39)

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves—goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying What I do is me: for that I came . (Poem 57)

Instress and inscape require and depend upon architectural space concepts. Moreover, they suggest the possibility of access: what may be inner—either as skeletal or soul self—may speak, may be described, hence may be perceived. The act of perception, either as sight or cognition, becomes concretized into a kind of literal penetration to what we might call essence, the structural or soul "inscape" of person or thing. In his references to architecture, then, it appears that Hopkins has translated into his own literary terms and concepts some attitudes at least reminiscent of, if not inspired by, Pater.

11a

"Flos, flower, blow, bloom, blossom ": architecture and etymology.

Gerard Manley Hopkins: Sketches from the early Diaries, 1863.

Two—

The Note-Books :

Architecture and Etymology

If we leaf through Hopkins's notebooks, any surprise we may have at discovering that architecture has much to do with Hopkins's poetic, should subside: Hopkins's own sketches—of Norman and Gothic windows, stairs, tracery and transoms, arches and columns—lace the pages of his journals, either illustrating his often technical descriptions of buildings, or just oddly afloat between his discussions of word roots, thoughts, or weather observations. In the early Diaries alone there are at least two dozen verbal descriptions and more than a dozen drawings in one brief journal-year. While it is not at all extraordinary that Hopkins took an interest in architecture, especially since at Oxford he was in the midst of clamor and controversy over new college buildings, his interest is not to be explained so simply; and it seems fair to ask what relationship Hopkins's interest in architecture may have to his fascination with words and with nature.