Preferred Citation: Duus, Masayo Umezawa. The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, c1999 1999. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9290090n/

| The Japanese ConspiracyThe Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920Masayo Umezawa DuusUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1999 The Regents of the University of California |

To Dr. Clifford I. Uyeda

whose fairness has impressed and

inspired me over the years

Preferred Citation: Duus, Masayo Umezawa. The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, c1999 1999. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9290090n/

To Dr. Clifford I. Uyeda

whose fairness has impressed and

inspired me over the years

Preface

My interest in how the history of Japanese Americans has intertwined with that of U.S.-Japan relations began with my first book, Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific , about the trial of Iva Toguri, a Japanese American woman accused of treason for making wartime propaganda broadcasts for the Japanese government. Since then I have published other books on this theme: a history of the 100th Battalion and the 442d Regimental Combat Unit, the Japanese American army units in World War II; and a biography of Tazuko Iwasaki, the first Japanese woman to work as a labor contractor on a Hawaiian sugar plantation. And with this book I return to that theme again.

During the years following World War I, relations between the United States and Japan, though cordial on the surface, were troubled by unresolved tensions. Many Americans distrusted Japan because of its aggressive policies in China, and many Japanese resented discrimination against Japanese immigrants in the United States. The immigration issue was a highly emotional one for the Japanese, whose attempt to include a "racial equality clause" in the League of Nations charter had been rebuffed by President Woodrow Wilson. The anti-Japanese movement in California and other parts of the West Coast has attracted the attention of many historians, but the immigration issue in Hawaii, then not yet a state, has not. A critical event that revealed anti-Japanese sentiment in Hawaii was the 1920 Japanese plantation workers' strike on Oahu, the subject of this book.

I first heard about the 1920 Oahu strike while interviewing Japanese American veterans whose families had been forced off the plantations

at the time of the strike. But it was during my research on Tazuko Iwasaki that I first sensed that a thread might link the strike with the anti-Japanese immigration law passed by the American Congress four years later. That thread was the alarm of the Hawaiian plantation owners, who were upset by the defiance of the Japanese cane field workers. While the planters succeeded in waiting out the strikers, who eventually abandoned their demands for higher wages, they were determined to reassert control of the labor force. Not only did the plantation owners work with the Hawaiian territorial government to indict the strike leaders on trumped-up conspiracy charges, they went to Washington, D.C., to lobby for lifting restrictions on the immigration of Chinese laborers. As I argue in this book, their testimony that a large Japanese immigrant community in Hawaii threatened the national interest contributed to the passage of the so-called Japanese Exclusion Act of 1924.

What confirmed my commitment to this research project was my discovery of the transcripts from the trial of the 1920 strike leaders, charged by the territorial government with conspiring to dynamite the house of Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki, the Japanese interpreter on the Olaa Plantation. I had despaired of finding the transcripts after I learned that the First Circuit Court of the State of Hawaii had thrown out many old records because it no longer had space to store them. By chance I discovered that Professor Harry Ball of the Sociology Department at the University of Hawaii collected documents discarded by government agencies. Thanks to his help I was able to find the transcripts in the basement of the Hamilton Library at the University of Hawaii, where he had stored them, and began to pursue the project in earnest.

In conducting research for this book, I found materials in several other archives. After several years of effort, under the Freedom of Information Act I obtained Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Department of Justice documents on Noboru Tsutsumi and other strike leaders; the record of the House and Senate hearings on the renewal of the importation of Chinese labor was in the National Archives; other official documents came from the Department of the Interior and the Territorial Government of Hawaii; and the diplomatic archives of the Foreign Ministry in Japan provided important source materials on the Japanese side. To the staff persons who helped me in these archives I would like to offer my thanks.

I interviewed many individuals in Japan and Hawaii, including the widows of three of the strike leaders, to learn as much as I could about the strikers. I would like to express my deep gratitude to the following

persons who cooperated with me in my research. In Hawaii: Yasuki Arakaki, Hiroshi Baba, Violet Fujinaka, Tom Fujise, Mitsu Fukuda, Ryuzo[*] Hirai, Tokutaro[*] Hirota, Magotaro[*] Hiruya, Edward Ishida, Koji[*] Iwasaki, Ten'ichi Kimoto, Takashi Kitaoka, Victor Kobayashi, Masao Koga, Kumaichi Kumasaki, Lefty Kuniyoshi, Masaji Marumoto, Spark Matsunaga, Gyoei Matsuura, Yoshie Mizuno, Michiko Nishimoto, Warren Nishimoto, Harold Oda, Franklin Odo, Asae Okamura, Nobuko Okinaga, Shoichi[*] Okinaga, Kiyoshi Okubo[*] , Moon Saito[*] , Ben Sakamaki, Kenji Santoki, Kameyo Sato[*] , Minoru Shinoda, Shigeru Sumino, Sakae Takahashi, Tomiji Togashi, Ryokin[*] Toyohira, Hatsuko Tsuruta, Seiei Wakikawa, Reizo[*] Watanabe, Tsuneichi Yamamoto, Shigeru Yano, and Paul Enpuku.

In Japan: Maino Baba, Mutsui Baba, Kaoru Furukawa, Akiko Fujitani, Kaichi Fujitani, Masao Goto[*] , Takeshi Haga, Yoshie Hashimoto, Chiso Ishida, Michiko Ito[*] , Genshichi Kogochi, Kiyoshi Kondo[*] ,

As many of those I interviewed were of advanced age, some have since passed away. I respectfully express my wish that their souls rest in peace.

I would like to thank Beth Cary for her preliminary translation of the original Japanese volume and my husband, Peter Duus, for revising and adapting her translation. My thanks go as well to Laura Driussi, Sheila Levine, and Rose Anne White of the University of California Press for shepherding the manuscript through production and to Sheila Berg for meticulously copyediting it.

Finally, I would like to thank the Suntory Foundation for its generosity in supporting the translation of the Japanese edition of this book.

MASAYO UMEZAWA DUUS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

JUNE 1998

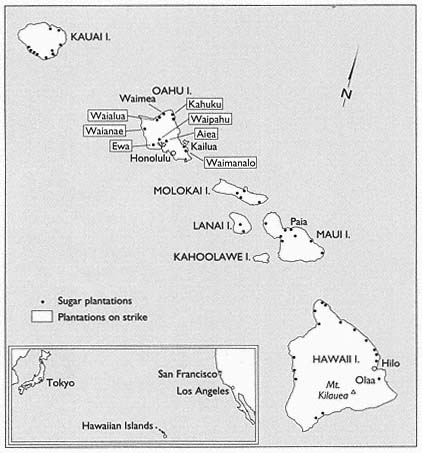

Maps

Map 1

Hawaiian Islands

Map 2

Oahu

Prologue—

A Dynamite Bomb Explodes:

Olaa Plantation, Hawaii: June 3, 1920

An Explosion in the Night

On April 15, 1920, on a street in South Braintree, Massachusetts, the paymaster of a shoe factory and his security guard were assaulted at midday while delivering the employees' payroll. The guard died instantly, the paymaster the next day. Three weeks later, on May 5, the shoemaker Nicola Sacco and the fishmonger Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested on suspicion of robbery and murder. Both men were Italian immigrants known to be anarchists. Thus began the "Sacco and Vanzetti Case," notorious in American labor history.

Less well known is an incident that began six weeks later, on June 3, 1920, at Olaa Plantation on the island of Hawaii, five thousand miles and five time zones from South Braintree. The journey by train across the continent and then by ship from the West Coast took half a month. To mainland Americans, Hawaii seemed closer to East Asia than to America, and the islands were still a territory, not yet recognized as a state.

A small item in the June 4 Honolulu Star Bulletin noted, "The home of a Japanese eight miles from Olaa was blown up with giant powder last night." The newspaper did not give the name of the victim, but it reported that the man was in a back bedroom at the time and was not killed, even though the front of the house was destroyed.

It is not surprising that no name was mentioned. Laborers who worked in the sugarcane fields, the main industry in Hawaii, were anonymous to the companies that employed them. Because their names

sounded unfamiliar to their haole bosses, they were forced to wear aluminum neck tags engraved with numbers. It was by these "bango" numbers that they were recognized when they received their semimonthly pay, charged items at the company store, or were punished for violating regulations.

The man unnamed in this incident, however, was not a mere laborer. He was Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki, the interpreter for the Olaa Sugar Company, who was paid a salary under his own name just as the haole employees were. At the time the forty-nine-year-old Sakamaki was known to the haoles as Frank Sakamaki.

During the trial over the incident, Sakamaki recalled the explosion. "It was about eleven o'clock P.M . that night of the third of June; maybe a little before or maybe ten or fifteen minutes," he said. "I didn't take a look at the clock that time; the clock was fallen down. I was awokened by sound and, of course, didn't realize that it was an explosion; first thought it was water-tank fell or something; anyway, I was awokened by the sound, and my wife was in another room and she called me, 'What was that sound? What was that noise?' Then a little later my boy said he smelled powder; then I realized it was an explosion."[1]

The Star Bulletin was wrong when it reported that Sakamaki was in a back bedroom. All of the bedrooms in the Sakamaki house were on the second floor; none were at the rear of the house. According to Sakamaki's testimony, after he heard the blast, he jumped out of bed and rushed downstairs with a flashlight. When he reached the first floor, it was so full of smoke he could not see clearly. Somehow he made his way outside and ran to the house of the inspector (the security guard hired directly by the plantation). Even running through the field of sugarcane taller than a man so fast that he got out of breath, it took him five or six minutes to get there. The inspector's wife, wearing a muumuu as a nightgown, came to the door. The inspector himself had just dashed out of his house, thinking that something had occurred at the mill.

Instead of following the inspector to the mill, Sakamaki ran to the Olaa Sugar Company office, grabbed the wall telephone, and called Charles F. Eckart, the manager of Olaa Plantation, at his home. After Sakamaki apologized for waking him in the middle of the night, Eckart calmly responded that he would contact the local police and then go to the Sakamaki house right away. Approximately twenty minutes later, Henry Martin, deputy sheriff of the Olaa district police station, arrived there by car.

In the meantime Sakamaki had run home and found that the smoke

had cleared considerably, revealing what had happened inside. In the parlor, the table was overturned, and legless chairs were strewn all over the room. It looked as if a toy chest had been dumped onto the floor. In the living room next to the parlor, shards from vases and other objects were scattered everywhere. Then Sakamaki noticed for the first time that the side of the house had been blown off.

In the seventy years since the explosion, Hawaiian society has undergone great changes, but today the only way to reach the Olaa Sugar Company from the city of Hilo is by following the old road. About eight miles from Hilo, Volcano Road, the route taken by tourist buses going to Mount Kilauea, crosses a road so narrow that one could easily miss it. The road curves gently for a mile or so toward the ocean. Since it was a private company road, it is not named on the map, but the local people still call it Plantation Road. Unlike the paved Volcano Road, it remains a gravel road just as it was in 1920. According to the confession of the perpetrator, it was the road he used to flee after setting the explosives.

When I visited Olaa in 1987, the road was overgrown on either side with sugarcane gone wild. After turning onto it, I saw in the distance beyond the golden cane the tall smokestack of the mill. As the mill was to be closed two months later after eighty-five years of operation, no smoke rose from it. The mill consisted of several dilapidated tin-sided structures. The suffocatingly sweet smell so peculiar to sugar refineries, produced by the filtering of the boiled juice pressed from the cane, was long gone. Next to a huge concrete water tank was a tall water tower. It was not the same one there at the time of the incident, but the location and height were similar. When Sakamaki and the inspector heard the blast of the explosion, both had mistakenly thought that the water tower had fallen down.

The Olaa Sugar Company building, referred to by the local people simply as the "Office," is four times larger than it was at the time of the incident. It is a very long single-story wooden structure with peeling white paint and a deep eave along the front to offer protection from the heavy rainfall throughout the year. The distance between the Office and the mill is about one hundred fifty meters across the sugarcane fields. Looking diagonally right behind the Office, the roof and smokestack of the mill are visible and the water tower tank seems to be floating on a sea of sugarcane.

The Sakamaki house was in the middle of the cane field, on the border of north district fields 390 and 370, near Olaa Eight Mile Station on

the rail line from Hilo. Hiroshi Baba, a trucking company owner in Hilo who formerly worked on the administrative staff at Olaa Sugar Company, lived in the former Sakamaki house until he retired. "It was a large house," he recalled, "just like one for the haoles." It stood by itself at a distance behind the company buildings. There were only three other houses nearby—company houses for haole technicians and a Portuguese engineer—but they were still at some distance across the cane fields. The camps where plantation laborers lived, grouped by their countries of origin, were even farther away. The closest, Eight Mile Camp, was half a mile away. The inspector's house at Eight Mile Camp, where about forty skilled mill workers lived, was about four hundred meters from the Sakamaki house.

The plantation workday started before sunup. The plantation laborers awakened at 4:30 A.M . and were in the fields by 6:00. The administration staff were at the Office by 7:00. Because they started so early in the morning, workers went to bed soon after sundown, and the lamps in their houses were turned off early in the evening. Sunset in Hawaii on the day of the incident was 6:38 P.M . When Sakamaki had run along the paths through the sugarcane fields on the night of the explosion, the moon was two-thirds full.

Houses on Hawaii, where the climate is always warm and humid, are set above the ground. The floor of the Sakamaki house was raised about 70 centimeters above ground level on the Hilo side but as high as 160 centimeters on the volcano, or mauka , side. The dynamite had been set under the floor between the parlor and the dining room on the mauka side. The impact of the explosion can be seen vividly in the photographs taken for the police by a Japanese photographer from Olaa on the morning after the incident. The outside of the house was faced with vertical boards. In the section with the worst damage, sixteen of these boards had been blown off, leaving a large hole that looked as if a cannon shell had hit. In other sections, the boards were cracked up to the roofline or were nearly falling off. The window glass had splintered, and the second floor window frame was twisted and dangling. Strewn on the ground were jagged fragments of wood, their ends seemingly sharpened, and scattered about were pieces of what looked like steel pipe. A kerosene tank under the floor had once piped in the oil for the lamps inside the house, but at the time of the explosion it was not being used. If this tank had been full of kerosene, the dynamite blast would have been considerably more destructive.

Plantation workers' living quarters in the camps were mostly row houses, and families even lived in one room, sleeping on mats on the wooden floor. By contrast the Sakamaki family lived in luxury. The house had running water. On the ground floor were a parlor, living room, and dining room across the hall from a kitchen, bath, and storage room. On the second floor were Mrs. Sakamaki's sewing room and four bedrooms. At the time of the blast, Sakamaki had six children. His eldest son, Paul (Tokuo), a seventeen-year-old junior in high school who had smelled the gunpowder right away, was the only one with his own bedroom. On the other side of the sewing room Sakamaki's wife, Haru (36), slept with their sixth son, Noboru (3), their oldest daughter, Masa (8), and their fifth son, Charles (Yuroku[*] , 5). (Their fourth son had died in infancy.) Across the hallway was the room where their second son, George (Joji[*] , 15), and third son, Shunzo (Shunzo[*] , 13), slept, and next to it was Sakamaki's bedroom. At the trial, Sakamaki recalled seeing cracks in his oldest boy's bedroom. "It was a narrow escape for us," he said. "We all think ourselves very fortunate we escape this."

The only Sakamaki children still living are Masa and Ben, a seventh son born ten months after the incident. Masa is the only witness who can describe the dynamiting incident as she saw it, but even now she does not wish to speak of her memories. Ben told me that at the time the Sakamaki garden was full of hibiscus and other colorful plants. "On the banana tree, which was the tallest tree by far," he said, "one of the fragments of wood was stuck like a knife into the trunk."

Who Was Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki?

After Sen Katayama, an early socialist and influential labor leader, visited Hawaii, he wrote an article in his journal, Tobei , devoted to promoting emigration to America.

In my tour of various locations on Hawaii Island, I have been struck beyond my imagination by the many Japanese who are involved in independent businesses and progressing to greater levels of prosperity. In particular, the Japanese like those at Olaa Plantation are actively growing sugarcane in trial cultivation, and so naturally are proud of their accomplishments and full of confidence and high morale. . . . Two men most likely to become well known at Olaa are Mr. Jiro[*] Iwasaki of Eleven Miles and Mr. Juzaburo Sakamaki at Nine Miles [author's note: mistake for Eight Miles]. They are the star actors in local business circles.[2]

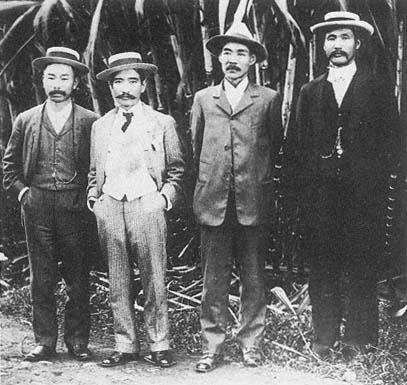

Japanese Americans who remember Olaa in its early days still mention the names of these two close furen (friends), Jirokichi (also known as Jiro[*] ) Iwasaki, the contract labor boss with two thousand immigrant laborers under him, and Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki, the plantation interpreter. Many photographs donated to the Bishop Museum in Honolulu by the descendants of Jirokichi Iwasaki show just the two of them, with the tall Iwasaki seated on a cane chair and the shorter Sakamaki standing next to him. Sakamaki, who always wore a suit, stood upright with hands on hips. Other photographs show the two men with important visitors, such as the consul general of Japan on his way to view Mount Kilauea, a succession of haole managers, or Emo[*] Imamura, the head priest of the Hawaii mission of Honpa Honganji and a powerful presence in the Japanese immigrant community. As these photographs make clear, Iwasaki and Sakamaki were men of status in the local Japanese community.

Sakamaki's distinctive feature was his eyes. In every photograph, Sakamaki stares intently straight at the camera lens, his gaze, beneath bushy eyebrows, penetrating and almost hostile. His eyes seem to reveal a suspicious nature. Even in family photographs in Ben's album, Sakamaki clenches his fists and furrows his brow as if he was in some pain. Ben remembers that his father, who was fifty when he was born, "was extremely short-tempered."

According to Tomiji Togashi, who was born in 1911 and reared on Olaa Plantation where his father had come from Niigata, Sakamaki was feared as a man of strong likes and dislikes. "He boasted that he was from a samurai family," said Togashi. When Sakamaki's house was blown apart in the explosion, his collection of samurai swords, spears, and helmets was flung onto the floor. But after leaving Japan as a youth, Sakamaki had never returned, and according to Ben, all the "samurai things" had been collected in Hawaii.

Records of the retainers in the Tsugaru domain of the Hirosaki City Library in Aomori prefecture show that generations of the Sakamaki family served in Edo as clerks. The sixth-generation Hisao Sakamaki, a samurai with an upper-middle-rank stipend, had six children. Juzaburo, the youngest child of his third son, was born in Tokyo in 1869, the year after the Meiji Restoration. Juzaburo's father died when he was four years old, and the family's life became difficult when the old domains were abolished in 1871. His mother had to run a private boardinghouse to make ends meet. As the youngest son raised by his widowed mother, Juzaburo was uncommonly headstrong. When he was fifteen, without

telling his mother, he stowed away on a ship bound overseas from Yokohama, hiding in the hold for a few days until the ship set sail.

In a way Sakamaki was following in the footsteps of Sen Katayama, who had landed a year earlier in San Francisco at the age of twenty-six, inspired by a letter from a friend who had gone to the United States earlier. America, his friend had written, was a place where you could study even if you were poor. Taking jobs as school boy, dishwasher, janitor, and servant, Katayama persevered until he finally obtained a degree in theology from Yale University's Divinity School. Life as a "school boy," working as a live-in servant helping with housework in the morning and evening while going to school during the day, offered the best opportunity for study, he later observed, but it was all too easy to become bored. "It is regrettable," he noted, "that the students who graduate are extremely rare."

After arriving in the United States, Sakamaki went East to Pennsylvania, where he spent nine years studying and working. But unlike Katayama, Sakamaki did not graduate from college. Although he was admitted to one, he did not stay to graduate. Receiving word that his mother was ill, he decided to return home. But by the time he reached Hawaii he learned that she was already dead, so he canceled his plans to go on to Japan. Just at the time, the Olaa Sugar Company was established, and he was hired as the company's only regular interpreter.

As interpreter, Sakamaki was the only pipeline between the company and the Japanese immigrants who made up the majority of the labor force at Olaa Plantation. Even a labor contractor like Iwasaki had to go through Sakamaki for all his contacts with the plantation manager. The outcome of discussions with plantation management very much depended on what the company interpreter said, so it is not surprising that Iwasaki kept on close terms with Sakamaki, calling him "Ju-chan[*] " and "furen."

Workers who cultivated a few acres of cane fields as tenants of the company as well as field laborers had to go through Sakamaki in all their dealings, from advances on fertilizer to bargaining for wages. Quite a few people called themselves interpreters, but Sakamaki had more clout than the others. As assistant postmaster of the Olaa post office, Sakamaki was involved in all the daily activities of the Japanese in Olaa. The post office was in a corner of the company office. The plantation manager was nominally the postmaster, but in actuality all the work was done by Sakamaki. As the agent of the Consulate General of Japan in Honolulu he was also in charge of administering the immigrants' fam-

ily register items. In this capacity, he not only dealt with registrations of births, deaths, marriages, adoptions and other family matters, he handled remittances that workers sent home. (A 1918 study conducted by the Consulate General showed that two-thirds of the monies sent back to Japan was handled through the plantation post office. Banks were inconvenient for plantation laborers as their branch offices were located in town.) Clearly the rebellious young stowaway, as Katayama reported, had made himself into a man of considerable local importance.

Two Suspects Are Arrested

Deputy Sheriff Martin rushed to the Sakamaki residence immediately after the explosion, but it was still dark, so there was nothing he could be do. He left quickly. Sakamaki's eldest son, Paul, and his second son, George, both high school students, took turns standing guard, pistol at the ready, until the sun rose. Early in the morning of June 4, Martin returned with a photographer to conduct his investigation. The senior captain of the police of the island of Hawaii, H. T. Lake, who had been posted previously at the Olaa police station and knew Sakamaki, also arrived from Hilo.

Arrests came quickly. The Honolulu Star Bulletin , whose June 4 article treated the explosion as a local event, gave it a mere ten lines, reporting that the case had been resolved. "Two Japanese have been arrested on suspicion," the paper reported. "The dynamiting, it is said, was the result of a row over cane contracts." The Japanese-language newspapers reported the case briefly too, but they gave the suspects' names. The Hawaii hochi[*] reported, "The police authorities suspect that those who set the dynamite were laborers with a grudge against the interpreter Sakamaki and intended to kill interpreter Sakamaki. They have arrested two men as suspects, G. Fujioka and S. Iwasa, and have taken them to the police station for questioning." The Hochi[*] article was dated "June 4, 11:34 A.M. : (Honolulu) head office." Since the news was telephoned from Hilo, that means that the suspects had already been arrested at the latest by 11:00 A.M. on the morning following the explosion.

No records of the Sakamaki incident remain in either the local police station or materials related to the history of Hilo. A directory of Japanese residents from the 1920s lists only one Fujioka with the initial G., a tenant field worker from Hiroshima prefecture. The other suspect was Sueji Iwasa, a labor contractor who had risen very rapidly, in competi-

tion with Jirokichi Iwasaki. A native of Fukuoka, he controlled several hundred laborers from Kyushu[*] . Natives of Kyushu had a reputation for being hot-tempered, and Iwasa was particularly well known for his high-handed methods. He was thirty-one years old at the time, some twenty years younger than Sakamaki. Sakamaki may have seen Iwasa as an upstart who, unlike his friend Iwasaki, did not understand the line between what was permissible and what was not.

Jirokichi Iwasaki had died the previous year. At the time of the explosion his widow, Tazuko, a total novice, had become the chief contracting agent for Olaa with the help of her husband's subordinates. Her husband's furen, Sakamaki, was also helpful to her in bidding on contracts. According to Tazuko Iwasaki's recollection, she worried that grudges arising over the bidding might result in sabotage, such as fires set in the cane fields during the harvest. She had her men take turns standing watch over the fields night and day. Other disturbances occurred as well. She mentioned that Sueji Iwasa was responsible for this kind of harassment. Naturally, Sakamaki did not make decisions to award labor contracts by himself. However, it was he who stood between the Japanese contractors and the company manager and other company officials. At the very least, Sakamaki was clearly in a position that made him the target of dissatisfactions and misunderstandings.

Nobody Said Much

A few days after the dynamiting incident, Charles Eckart, the Olaa Plantation manager, gathered the local Japanese contractors and representatives of the tenant farmers at his home. It was located about two miles south of the company office on a rise with a distant view of the ocean. The mansion still stands, its landmark a huge banyan tree that is said to date from the era when native chieftains held power. Along the private road leading to the mansion dozens of tall coconut trees pierce the sky. The three-story white structure sits on the crest of a rise surrounded by an extensive lawn. On its grounds were a stable for a few riding horses and a shed for a dozen or so dairy cows kept for milk and butter. Although the mansion is weathered and worn now, it is still imposing enough to hint at the status and power of the plantation manager, who the Japanese laborers likened to a daimyo, or feudal lord, and who they regarded as the "owner" of the plantation. At the front was a wide porch with a carved bannister from which the ocean could be seen. Hiroshi Baba, who grew up in a cottage behind the mansion, where his father

worked as a cook, recalls that his father told him that it was on that porch that the Japanese representatives assembled.

Charles F. Eckart (age forty-five at the time) had come to Hawaii from California, a state where anti-Japanese feelings ran high. Of the successive managers of the plantation he enjoyed a particularly high reputation among the Japanese immigrant workers, who regarded him as a man of good character. After studying agricultural chemistry in college, he was invited to work at the Hawaii experiment station of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association, where he eventually became the director. Even after he was hired away in 1913 to become the manager at Olaa, he continued to be active in research on prevention of damage by insects. In 1919 he set up a plant to produce paper from the cane fiber remaining after straining. The paper was used to cover cane sprouts to prevent the growth of weeds. This innovation brought savings in labor costs. Later widely used in pineapple fields (where vinyl sheets now substitute for paper), this method earned Eckart a place in the history of Hawaiian sugar production. The 1918 Hawaii Meikan, a Japanese-language directory, noted, "[Eckart] obtains good results by working hard and diligently [as plantation manager] without making distinctions among regular workers, contract workers, or independent tenant farmers [and] promotes mutual benefit to the satisfaction of both sides without clashes of opinion at contract renewal times." (These words are testimony to the capabilities of Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki, who, as interpreter, acted as mediator between the company and the Japanese.)

From the start Eckart faced the explosion incident squarely as a sign of discord among the Olaa Plantation workers. Through a young nisei (second-generation) interpreter, Eckart asked the assembled contractors and tenant representatives, "I'd like to have you tell me without hesitation if you have any pilikia [trouble] or complaints about Frank Sakamaki." But no one said much to the "plantation owner." Sakamaki was neither dismissed nor demoted as a result of the incident. He remained the authority who stood between the Japanese and the company.

After June 4 no further reports on the explosion appeared in either the English or the Japanese newspapers. According to the June 4 Hawaii hochi[*] , Iwasa and Fujioka, the two men arrested for "attempting to kill Sakamaki by setting dynamite," were eventually released for lack of evidence. There were others who may have wanted to harm Sakamaki, but they may have felt that their grudges were satisfied by the dynamiting incident. Even though many deplored the use of dynamite, no one sympathized with Sakamaki. As the days gradually passed, the Olaa laborers,

weary from their grueling work, spoke less and less about the incident, and then not at all.

The True Nature of the Sakamaki Incident

Dynamite, an extremely explosive nitroglycerin compound, can blow apart solid rock in an instant. Today it is still indispensable in mining and in dam, tunnel, and road construction. It also was one of the essential tools of the Hawaiian sugar industry. It was used in the volcanic terrain of Olaa to break up rocks in the cane fields and to construct roads through them. But dynamite can also be used as a weapon, and it is very much part of the history of labor strife in the United States. Indeed, numerous well-known labor struggles involved the use, or rather the alleged use, of dynamite. The Pennsylvania coal mine strike (1875), Chicago's Haymarket Square riot (1886), the Pullman Train Coach Company strike (1894), the assassination of the governor of Idaho (1905), the Los Angeles Times bombing incident (1910), the Lawrence textile workers' strike (1912), the Ludlow coal mine strike (1913), the Tom Mooney case (1915), and more—in many of these cases labor leaders were arrested and convicted on suspicion of killing or attempted killing by dynamite blasts, often on charges trumped up by the authorities, even though the true perpetrators remained unknown.

The dynamiting of the Sakamaki house should be considered part of this history of violent labor strife. Five months before the incident a strike had begun on a scale that Hawaii had not previously seen. Known as the second Oahu Island strike, it spread to all the Hawaiian islands. The strike was organized by the Japanese immigrant laborers who formed the majority of the sugarcane field labor force. At the time of the dynamiting incident no one on the plantation suggested that the explosion at the Sakamaki house might be related to this strike, nor was there any indication that the local authorities viewed the event in that light. But the significance of the Sakamaki dynamiting incident can only be understood against the background of labor struggles in the United States.

Neither the dynamiting incident nor the 1920 Oahu strike has received much, if any, attention in the history of American labor. The likely reason is that these events occurred in Hawaii, a territory distant from the mainland, and involved Japanese immigrant workers who remained outside the mainstream of American society. Nor have historians of the Japanese immigrant community in Hawaii delved into either event de-

spite the importance of the strike in the lives of so many Japanese American families.

This book attempts to situate the events surrounding the 1920 Oahu strike in the framework of both labor history and immigrant history. But to treat them solely within these frameworks may blind us to their true significance. The Oahu strike captured public attention on the mainland in August 1921, when it became an issue before both houses of Congress in Washington, D.C. The struggle between the immigrant Japanese workers and the powerful Hawaiian sugar plantation owners became part of a process that led to the passage of the so-called Exclusion Act of 1924, an event that was to cast a long shadow on future relations between Japan and the United States.

By the early 1920s many Americans had begun to look at Japan and the Japanese with deep suspicion. In late 1921 a long feature article on U.S.-Japan relations captured some of those feelings.

The most important country in the world to Americans today is Japan. . . . Japan is the only nation whose commercial and territorial ambitions, whose naval and emigration policies are in direct conflict with our own. . . . With the temporary eclipse of Germany as a world-power, Japan is the only potential enemy on our horizon, she is the only nation that we have reason to fear. The problem that demands the most serious consideration of the American people and the highest quality of American statesmanship is the Japanese Question. On its correct and early resolution hangs the peace of the world. . . . What is needed at the present juncture is an earnest endeavor on the part of each people to gain a better understanding of the temperament, traditions, ambitions, problems, and limitations of the other, and to make corresponding allowances for them—in short, to cultivate a charitable attitude of mind. . . . [T]he interests at stake are so vast and far-reaching, the consequences of an armed conflict would be so catastrophic and overwhelming, that it is unthinkable that the two people should be permitted to drift into war through a lack of knowledge and appreciation of each other.[3]

But far from nurturing a "charitable attitude of mind" among the American public, the Oahu strike deepened distrust of Japan. And in doing so it marked a step toward the "unthinkable" conflict that many on both sides of the Pacific already saw on the distant horizon.

One—

The Japanese Village in the Pacific

Japanese Immigration to Hawaii

The first Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, known as the gannen mono (first-year arrivals), arrived in 1868. The Hawaiian Kingdom's Board of Immigration had asked Eugene Van Reed, an American merchant who had served as the Hawaiian consul in Japan, to recruit contract laborers to work in the cane fields. Van Reed recommended the Japanese as excellent laborers and spoke in the highest terms of their industry and docility, their cleanliness and honesty, and their adaptability.

It proved difficult to gather the anticipated number of 350 immigrants, and in the end only 148 (of these 6 were women) were actually recruited. Their pay was to be $4 per month with room and board provided for a three-year period, and Hawaii covered their round-trip ship passage. Many of the gannen mono were gamblers and idlers recruited from the streets of Yokohama who knew nothing about farming and were ill-suited for hard work in the sugarcane fields. When misunderstandings arose about their pay, this first effort at bringing in Japanese labor ended in failure. No additional contract workers came from Japan for another decade and a half.

By that time sugar had become king in Hawaii. In the late eighteenth century James Cook, the first Caucasian to set foot on Hawaiian soil, had noted in his ship journal that he had seen sugarcane. Half a century later, in the 1820s, missionaries arrived by sailing ship from New England, not only to convert the natives to Christianity, but also to teach them how to write and farm. It was the Hawaiian-born descendants of

these missionaries, called kamaaina , who saw the potential for sugarcane production in Hawaii. In 1848 foreigners, who had previously leased cane fields from the Hawaiian kings and chieftains, were allowed to buy land. Haole ownership of land increased rapidly. Not only did the scale of the sugar industry change suddenly, the social structure of Hawaii was transformed as well. The power of the Hawaiian royal dynasty, established by King Kamehameha I ten years before the missionaries' arrival, began to decline.

From the beginning the greatest problem for the Hawaiian sugar industry was the lack of a labor force. Native Hawaiians worked only when they felt like it—a custom they called kanaka —and were not inclined toward heavy labor in the fields all day long. Their numbers were also rapidly reduced by epidemic disease brought by foreign whaling ships. In 1850 a labor contract law was enacted to increase the labor supply. Workers from China were the first outsiders to be sought out as cheap labor. Docile and hardworking, they gradually constituted the majority of cane field laborers. But after working diligently and saving money, these Chinese workers would leave the fields when their contracts were up (five years initially, three years from 1870 on) to open up businesses. Some also went to the American mainland.

From early on Chinese laborers had gone to California to work on building the continental railroad. The Taiping rebellion and other disturbances that wreaked havoc in China produced a continuous stream of immigrants seeking work in America. But the Chinese newcomers were soon perceived as a threat by Caucasian laborers. Not only did they put up with exploitation and work hard for low pay, they held fast to their own ways of life. They still wore their pigtails, they lived in their own separate Chinatowns, and they continued to gamble and smoke opium. Seeing the Chinese as immigrants who could not be assimilated, the Caucasians began to demand that the Chinese must go. When a recession in the 1870s led to severe unemployment, Caucasian labor unions took the lead in the movement opposing Chinese immigration to the United States. Gradually the quota for Chinese immigrants was decreased, and in 1882 Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

By this time only a quarter of Chinese laborers who had migrated to Hawaii were left in the cane fields, and the sugar planters of Hawaii had already begun to seek other cheap labor to take their place. The Japanese government signed a formal immigration agreement with the kingdom of Hawaii in 1885. During the next nine years, nearly thirty thousand Japanese crossed the ocean to work under three-year contracts for

wages of $12.50 per month. Most were poor tenant farmers from the bottom economic strata in Japan. Unlike the gannen mono, these Japanese contract workers were accustomed to working in the fields. Seeing that the Japanese worked as strenuously as the Chinese, the plantation owners soon competed to hire them. (Plantation managers ordered the procurement of "Japs" in the same memoranda in which they ordered macaroni, rice, horses, and mules.)

The Japanese government backed the contract labor system as a way of earning foreign exchange. It declared, "If we send 3 million workers out into the world and each one of them sends back to Japan $6 per year, the country will benefit." In fact, money remitted by the immigrants to Japan during the Meiji period amounted to more than 2 million yen annually. For a Japan struggling under foreign debts incurred to procure military equipment and other foreign goods, the foreign currency sent home by the immigrants, who hoped to return home "clad in brocade" after enduring hard labor under the broiling Hawaiian sun, was not an insignificant sum.

The United States was in a period of rapid industrial growth after the end of the Civil War. A great wave of European immigrants were pouring into the East Coast as unskilled factory workers, just as the Japanese were pouring into Hawaii, still an independent kingdom. There was a significant difference, however, between the Japanese and the European immigrants. The Europeans had forsaken their homelands and had placed their hopes in the New World, where they intended to stay permanently. By contrast, the Japanese immigrants to Hawaii expected to return home. In fact, they were indentured as contract immigrants, a practice forbidden by law in the United States. Japanese Foreign Ministry documents referred to the immigrants as "officially contracted overseas laborers" (kanyaku dekaseginin ), and they were admitted into Hawaii solely to work in the sugarcane fields.

After 1893, when the Japanese government entrusted the immigration business to private immigration companies, the number of privately contracted overseas laborers increased. The following year the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown with the help of American marines supporting the haole sugar planters. Hawaii became a "republic." Four years later, in 1898, the republic was annexed by the United States. For the sugar planters, who engineered the whole process, joining the United States was a long-cherished goal. Annexation meant an end to tariffs, enabling Hawaiian sugar to compete better with Cuban sugar or beet sugar from the U.S. mainland.

Nearly all the sugar plantations in Hawaii were under the control of five major sugar factoring companies organized by the powerful and unified kamaaina elite. Dominating all aspects of sugar marketing and management, as well as procurement of the labor force and seeds, these companies gradually absorbed small-scale growers with meager capital. Known as the Big Five, they became the new royalty of Hawaii and exercised enormous influence over the Hawaiian territorial government.

The annexation of Hawaii coincided with the extension of American sovereignty over the territories of the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, acquired as a result of the Spanish-American War, and with the enunciation of the Open Door policy in China. These developments marked a full-fledged American advance into the Asia-Pacific region, just at a time when Japan was expanding its power on the Asian continent after its military victory over China in 1895. In a clear display of its national strength, almost annually Japan had already been sending its imperial fleet, with rising sun flag unfurled, to Hawaii, a strategic spot in the Pacific Ocean.

Olaa Plantation, where Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki was hired as an interpreter, was established as a corporation capitalized at $5 million in May 1899, a year after annexation. Anticipating capital infusion from the U.S. mainland, much new plantation land was opened up after annexation. The development of Olaa was unprecedented in scale. An enormous land reclamation project opened some 20,000 acres (8,093 hectares) of cane fields extending from a point eight miles from Hilo to the Kilauea volcano. Originally owned by the Hawaiian royal family, the Olaa area was a jungle thick with ohia trees, ferns, and shrubs. The land had been sold to private individuals, and coffee cultivation had been attempted some ten years before but had ended in failure because of too much rainfall. The climate, however, was very suitable for sugarcane cultivation.

The first person to be hired for the Olaa reclamation project was the labor contractor Jirokichi Iwasaki. Gathering about fifty Japanese laborers and with the help of three horses, Iwasaki cleared 40 acres (about 16 hectares). He was the first contractor to undertake not only clearing the land but also the entire process of sugarcane cultivation, from kanakou (planting of cane), hanawae (irrigation of planted cane), hole-hole (cutting of dried grass), and kachiken (harvesting the cane) to furubi (transporting the cane by waterways) and hapai ko (loading). And it was Juzaburo Sakamaki's job not merely to act as interpreter but to enable the Japanese laborers and the company to understand each other.

Within six months of the opening of the plantation, the number of laborers at Olaa swelled to 1,829. The vast majority were Japanese (1,268 were Japanese, 132 were Chinese, and 429 were Hawaiian). Still there were not enough. Workers were needed not only to grow sugar cane but also to lay a railroad line to carry the cane to the port at Hilo.

Annexation advanced the interests of the sugar industry, but it was not all to the producers' advantage. When Hawaii came under American law, contract labor immigration ended immediately. Finding themselves unexpectedly free, many Japanese workers left Hawaii in search of "gold-bearing trees" on the American mainland, where working conditions were vastly better. The Hawaiian sugar producers, who had expected that American law would not apply in Hawaii for three years, grew alarmed. To deal with the exodus of Japanese laborers, the Hawaiian legislature enacted a high business tax on the go-betweens who supplied laborers to the mainland, but even this did not halt the flow of workers out of Hawaii.

In the meantime anti-Japanese movements gained momentum on the West Coast. The California Japanese Exclusion League circulated pamphlets alleging that Japanese immigrants "don't mind low pay and long hours of work"; that they "have a strong sense of patriotism, and send money to their homeland without contributing to the American economy"; that they "do not make efforts to learn English"; that they "do not throw off their own culture, and refuse to assimilate"; and that they "engage in public urination, gamble with hanafuda cards, and, even on Sunday, get drunk and buy women." When there was an economic downturn, Caucasian workers targeted Japanese immigrants just as earlier they had worked to exclude Chinese low-wage workers.

Against this background, in 1907 President Theodore Roosevelt issued an executive order on termination of labor migration from Hawaii. Since Japan showed its ambition to dominate East Asia with its victory in the Russo-Japanese War two years earlier, American wariness toward Japan was rapidly on the rise. In 1906 the San Francisco School Board had resolved to segregate Japanese pupils in the public schools. When the Japanese government objected, the federal government in Washington, D.C., forced the city of San Francisco to rescind its resolution. But at the same time Roosevelt issued his executive order preventing Japanese immigrants from going to the mainland from Hawaii.

In 1908 the so-called Gentlemen's Agreement was reached to appease anti-Japanese feelings. The Japanese government agreed to voluntarily restrict emigration to the United States to reentering immigrants and

their parents, wives, or children. Until the Gentlemen's Agreement the majority of Japanese immigrants had been single men, and with so few women, relations between the sexes in the Japanese immigrant community provided one source of anti-Japanese feelings among the Caucasians. To put an end to this situation "picture bride" marriages—marriages of convenience contracted by prospective partners who exchanged photographs—were encouraged.

On the Eve of the First Oahu Strike

The Hawaiian consul in Japan, Van Reed, who had sent the first group of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, assured the Hawaiian authorities that the Japanese were "docile." From the time the first shipload of government contract immigrants arrived, however, they constantly called for improvements in their harsh working conditions. The lunas , the overseers in the cane fields, were mostly Scottish, Portuguese, and Hawaiian. The Scottish, many of them former ship hands, in particular, were known for their mercilessness. They patrolled the fields on horseback, occasionally wielding their long snakeskin whips. A Department of Labor official sent to investigate labor conditions in the cane fields in 1910, reported that callous exploitation and abuse by the lunas were common on many plantations. He concluded that psychological oppression of cane field workers in Hawaii was no different from that suffered by black slaves in the South.

The Japanese laborers reacted to brutal treatment by the company by escaping, setting fire to cane fields, and other hostile acts. When contract labor was outlawed after annexation, the number of strikes, formal protests marked by organized negotiation, suddenly increased. For example, all the Japanese workers at Olaa Plantation struck on June 25, 1905. The origin of this strike was the death of a laborer who had taken medicine given him by the plantation hospital doctor. In those days plantation hospitals were often hospitals in name only, staffed by doctors with questionable qualifications, who sent workers home with laxatives for stomach- or headaches and Mercurochrome for cuts. The main work of the plantation hospital doctor, it was said, was to judge whether a worker was feigning illness.

The details of the 1905 Olaa strike are sketchy, but remaining documents indicate that the laborers demanded the dismissal not only of the plantation doctor and the clinic janitor but the plantation company in-

terpreter, Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki, as well. The disturbance subsided the next day, however, and Sakamaki was not dismissed. Calling this protest a "strike" was clearly overreaction on the part of the company, but strikes on other plantations occurred around the same time. In 1901 cane cutters on Ewa Plantation struck for higher pay, and similar strikes took place at Waialua and Lahaina plantations in 1905 and Waipahu Plantation in 1906. But plantation workers also protested other kinds of exploitation and abuses as well.[1]

The first Oahu strike occurred in 1909, the year after the Gentlemen's Agreement. Approximately seven thousand Japanese laborers in all plantations on Oahu abandoned the cane fields for three months just before harvest, and the resulting collective bargaining was on an unprecedented scale. For the first time strikers called for the abolition of racial discrimination in treatment of workers and demanded wage increases to improve living conditions.

From the outset the sugar planters' policy toward laborers was based on racial discrimination. When the plantation owners imported Chinese low-wage labor, one of their motives was to raise the competitive spirit of the Hawaiians, who they thought took things too easily. On the plantations workers of each nationality set up their own living areas, forming Japanese camps or Chinese camps. Immigrant workers preferred to live together with their fellow countrymen. The plantation owners turned this to their own advantage by cleverly manipulating the competitiveness among the different nationalities to increase productivity. In the order of their arrival, the nationalities were Chinese, Japanese, Polynesians, Portuguese, Germans, Norwegians, Spanish, Australians, Italians, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Koreans, Filipinos, and Russians.

As the Asian worker population grew, the plantation owners attempted to balance the labor force by hiring at least 10 percent white workers. They offered Europeans much better conditions than the Asians. The white workers were technicians and skilled workers in the mills, not manual laborers in the plantation fields. Records for 1896 show that while Japanese were given transportation costs plus wages, Germans were paid three times the wages of Japanese and given board as well. Rather than the shabby row houses allotted to Japanese, single-family houses were the norm for whites.

Although European workers were treated preferentially, most of them left for the American mainland when their three-year contracts expired.

Few stayed on in Hawaii. The Portuguese were the exception. The majority had come to Hawaii with their families intending to settle. The Portuguese came from a country close to the African continent and were swarthy, so the Hawaiian sugar planters did not recognize them as 100 percent white, but they did consider them best suited to oversee Asians in the fields.

Three months before the start of the first Oahu strike on January 29, 1909, a committee investigating agriculture in Hawaii sent a report to the secretary of agriculture in Washington, D.C.:

There are some things about the Japanese situation in Hawaii that I believe the President should know. We are having industrial troubles with this race and there have been threats on the part of the Japanese of murder, assassination and destruction of plantation properties by fire, although thus far nothing more serious than to be a concerted effort to get all the Japanese laborers in Hawaii to go on a strike, has come of it.

The report, conveying the sugar planters' alarm about the Japanese laborers, was forwarded by the secretary of state to the secretary of the interior and on to the president. It forecast that strikes were coming in Hawaii. From the planters' perspective the attitude of the Japanese laborers was threatening.

When the 1909 strike began, for example, it was not unusual to see editorials such as the following in the Japanese-language newspapers.

Now is the time to act in the spirit of national unity to assert our comrades' prestige and our comrades' rights. Even if, as you might say, we must endure coarse food, as subjects of the greater Japanese empire we will not flinch in standing up for a righteous cause. The Japanese are a people with the world's most fearsome perseverance. As long as they have rice and salt they can keep alive. In the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, our heroic officers and soldiers sustained themselves for many months eating almost nothing but rice and pickled ume plums. That demonstrated our national glory in the world.[2]

During the 1909 strike opponents called those demanding wage increases "agitators," "irresponsible men," "opportunists," and "outlaws"; similarly, those who were against the strike were called "planters' dogs," "planters' pigs," "insurgents," "traitors," and "Czarist spies."

The number of Japanese immigrants increased sharply after the Russo-Japanese War. In 1906, 30,393 Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaii, slightly more than the 29,669 who had come during the nine-year government-sponsored contract labor system. The majority were younger sons of farming families, who had returned safely from the war

front but were unable to find work or inherit land. The government in Tokyo as well as prefectural governments fanned an "American fever" among these returning veterans. But the arrival of these immigrants, who had survived the battlefield, not only incited anti-Japanese feelings on the American mainland, it brought a sudden increase in the number of Japanese groups with patriotic names in Hawaii as well.

The book most often packed in the trunks of these former soldiers was Sen Katayama's Tobei annai (Guide to Going to America), a slim volume of seventy-nine pages first published in 1901. The initial printing of two thousand copies sold out in one week, and the book went through many subsequent printings, becoming a best-seller of the day. Its message was forthrightly patriotic. "For our country Japan to build up a strong power in the Orient and to attempt to achieve an independent destiny, Japan must promote thriving industries," the author noted. "That is to say, our country Japan should not remain an isolated island in the Orient but should pursue its advantage by expanding into the rest of the world. . . . It is my deepest belief that our fellow Japanese who depart their country and brave the vast wild ocean to enter another land, engage in business abroad, and make themselves economically viable are the most loyal to the Emperor and patriotic among our countrymen ."

Katayama, who had returned to Japan after spending more than a decade living and studying in America, was a Christian Socialist. He founded Kingsley Hall, the first modern settlement house in Japan, participated in forming Japan's first labor union, became the editor of the first trade union paper, and joined with Shusui[*] Kotoku[*] and Isoo Abe to organize the Society for the Study of Socialism (Shakaishugi Kenkyukai[*] ). As he traveled throughout Japan publicizing the labor movement, Katayama urged Japanese youth to emigrate to America, and he established the American Emigration Association (Tobei Kyokai[*] ), which held monthly meetings at Kingsley Hall. Readers who subscribed to his trade union paper, Rodo[*] sekai (Labor World), automatically became members of the society.[3] Not only did Katayama want to stabilize the paper's finances by gathering readers interested in going to America, he also hoped to inform these youths about labor issues and socialism. The back cover of Tobei annai carried an advertisement for Rodo sekai . "Those who have been tyrannized by authority, come and enjoy Labor World ," it said. "Those who are oppressed by the wealthy, come and make your appeal to Labor World ." While Sen Katayama was a socialist, he was

also a thorough realist. His argument for emigration was well within the bounds of a nationalist argument, which expected the emigrants to return to Japan.

Suspicious Japanese in America

Not all the Japanese immigrants who crossed the Pacific were field laborers or ambitious students. The United States, particularly the West Coast, was also a haven for those whose political views were too radical to be tolerated by the authorities at home. At first many were refugees from the "popular rights movement," which had fought to force the Japanese government to adopt a constitution establishing a popularly elected national assembly. By the early 1900s Japanese with more extreme views began to arrive on the West Coast. The San Francisco region, including the city of Oakland across the bay, became a hotbed of antigovernment political malcontents. It is likely that the activities of these Japanese on the West Coast heightened the anxieties of the Hawaiian sugar planters and territorial officials.

In 1907, two years before the first Oahu strike, an open letter addressed to "Mutsuhito, Emperor of Japan from Anarchists-Terrorists" was posted at the Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco. It began, "We demand the implementation of the principle of assassination." After claiming that the emperor was not a god but, like other humans, an animal who had evolved from apes, it went on, "[The first emperor] Jimmu, the most brutal and inhumane man of his time, ruled as sovereign; under the name of being ruler he relished in every kind of crime and sin; his son followed his example and his grandson after him followed the example of his father; and so on and on down until 122 generations later." The "open letter" concluded, "Hey you, miserable Mutsuhito. Bombs are all around you, about to explode. Farewell to you."

This head-on attack against the authority of the emperor system shocked both Prime Minister Kimmochi Saionji and elder statesman Aritomo Yamagata, who immediately called in the head of the supreme court and the chief prosecutor to demand a review of the control of socialists. The incident sharply changed the attitude of the Japanese government toward leftist movements. The following year secret documents identifying "dangerous persons requiring close scrutiny" were prepared by the Police Bureau of the Home Ministry for distribution within the government. Socialists, anarchists, and communists were to be put un-

der secret surveillance, but all those who criticized the existing national political system were targeted as well.

It is of particular interest that in this secret document are to be found many reports about "those residing in the U.S." According to an August 31, 1909, report by the consul general in San Francisco, "The anarchist movement had its origin in young men who gathered in San Francisco to hear Denjiro[*] [Shusui[*] ] Kotoku[*] advocate socialism on his visit to the U.S."[4] Shusui Kotoku spent eight months in San Francisco after arriving in November 1905. He had been imprisoned for five months for violating press ordinances in articles written for the Heimin shinbun (Commoner's Paper), and after his release from jail he left for America to recover his health. In San Francisco he relied on the help of Shigeki Oka, a former colleague at the newspaper Yorozu choho[*] , who headed the San Francisco branch of the Heiminsha, a radical organization, and eked out a living in the freight business. With Oka's help, Kotoku made contact with American socialists and anarchists. What most influenced him during his stay were San Francisco's Great Earthquake, which occurred six months after his arrival, and his contacts with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), an organization that found its way into the Police Bureau's top secret report.[5]

The mainstream of the American labor movement was represented by the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the largest labor union since its founding in 1886. The AFL took as members only skilled laborers and tended to exclude people of color. The IWW was formed in opposition to the AFL and welcomed members regardless of nationality, race, religion, or gender. An epoch-making federation, it included those abandoned by the AFL, those at the bottom of society, unskilled laborers, blacks, and new Asian immigrants unable to speak English. Unlike the moderate AFL, which put cooperation between labor and management first, the IWW adopted a strong ideology stressing that there were no common interests between employer and employee and that the mission of the working class was to "abolish the capitalist system." The IWW proclaimed that the sole road toward working-class liberation was through direct action such as strikes and boycotts. From its inception, the American authorities put the IWW under close scrutiny as a radical group.

Kotoku contrasted his impressions of the IWW and AFL as "idealistic versus realistic, revolutionary versus reformist, radical versus moder-

ate, those that put weight on the propagation of ideology versus those that place emphasis on winning elections." He confessed, "If I were to choose between these two, I prefer the idealistic, revolutionary, and radical."[6] On his return to Japan, Kotoku[*] squarely denounced the parliamentarianism of the moderate socialists and declared that the only strategy for the workers was to mount a general strike. He had become an advocate of the revolutionary methods of syndicalism. By urging a strategy of direct action imported from America, Kotoku hoped to reinvigorate the socialist movement, which was being stifled under intense repression from the authorities.

In San Francisco, Kotoku had again met Katayama with whom he had organized the Society for the Study of Socialism. Although the two men were opponents within the socialist movement, and although their personalities and ways of life were quite different, they were cordial toward one another in a foreign land. Katayama had been in the United States and Europe since December 1903. He had just returned to America after attending the Sixth International Socialist and Trade Union Congress in Amsterdam, where he served as vice-chairman along with the Russian representative. The congress had unanimously passed a resolution opposing war. During his stay in the United States, Katayama had planned to lead a group of immigrants to open up rice cultivation in Texas, but this plan ended in failure. However, he had succeeded in forming socialist groups among Japanese immigrants in Seattle and other areas on the West Coast.

Just before his return to Japan in 1906 Kotoku had organized a socialist revolutionary party whose party membership register included the names of fifty-two persons from San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Sacramento, Chicago, Boston, and New York. Among them was Sakutaro[*] Iwasa, who later became a central figure along with Sakae Osugi[*] in the anarchist movement. The incendiary open letter posted on the consulate door in San Francisco was instigated by a member of this group. Having promoted his ideas freely in the United States where he could evade the Japanese authorities, in what seems to be an irresponsible decision, Kotoku summarily returned to Japan. The explosion of free thought he stimulated drew the attention not only of Japanese officials but also of American authorities.

Even before the open letter incident, the socialist revolutionary party had created a furor by publishing an article suggesting the assassination of the American president in its organ, Kakumei (Revolution). The San Francisco Chronicle ran the headline "Secret Servicemen on the trail of

Japanese publishers—Japs favor killing of President Roosevelt."[7] And across the bay, the Berkeley Daily Gazette warned, "Hotbed of Japanese Anarchists located here—the Yellow Peril."[8] The author of the radical statement, Tetsugoro[*] Takeuchi, a member of the revolutionary party, was forced to move to Fresno, where he organized the Japanese Fresno Federation of Labor and published its magazine, Rodo[*] (Labor). In 1908 he led five thousand Japanese seasonal migrant grape pickers in a strike demanding better working conditions and wage increases. It was supported by Italian and Mexican members of the IWW. Four months before, Japanese immigrants had participated in a strike started by Mexicans in the sugar beet fields of southern California. Although the strike was quickly suppressed, the new involvement of Japanese laborers with the IWW attracted the notice of American authorities.

It was against this background of radicalism and labor unrest among Japanese workers on the mainland that the 1909 Oahu strike began. Sakutaro[*] Iwasa and other Japanese sympathizers in San Francisco, calling themselves the Japanese Federation Strike Investigation Committee, sent a reporter from the newspaper Nichibei to Hawaii. An editorial in the paper strongly supported the strike: "This strike is the only way to struggle against capitalists."[9] Although the Japanese supporters on the mainland showed extraordinary interest in the Oahu strike, the largest ever mounted by Japanese immigrant workers, neither Japanese leftist activists nor the IWW became involved. Neither did the Police Bureau's secret report list any activists related to Hawaii.

The first Oahu strike ended in failure when all of its leaders were arrested. Soon after the strike, however, working conditions improved when treatment of workers on the basis of racial discrimination lessened and wages were increased. But the strike also spread anti-Japanese sentiments among the Hawaiian governing elite. The "Japanese problem" in Hawaii eventually came to the surface in the late 1910s in the controversy surrounding the oversight of the Japanese-language schools. As a participant in World War I, America had gone through a campaign of "one nation, one flag, one language." It was vital that an awareness of being an American was instilled in a nation made up of immigrants from so many countries. At a time when this "100% American movement" was at its height, the Japanese-language schools in Hawaii became the object of attack.

Two—

A Person to Be Watched:

Honolulu: 1918–1919

According to the records of the Japanese Consulate General in Honolulu, on February 28, 1918, twenty-eight-year-old Noboru Tsutsumi arrived in Hawaii to take up a post as principal of a local Japanese-language school. Two and a half years later his name also turned up in the records of the General Intelligence Division of the Bureau of Investigation (renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1935) in Washington, D.C. The division had been established by Attorney General A. M. Palmer in June 1919 after a series of bombings at the homes of high-level government officials. Charged with gathering information about revolutionary and ultra-radical groups, the General Intelligence Division was placed under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover, who had entered the bureau a scant two years before. Fulfilling Palmer's expectations in short order, Hoover set up a master file of all radical activities, making it possible "to determine or ascertain in a few minutes the numerous ramifications or individuals connected with the ultra-radical movement."

Bluntly put, the activities of the Bureau of Investigation were the by-product of the "red scare" that followed the Russian revolution. Fearing political subversion, the bureau specifically targeted labor movement leaders who were foreigners. Those suspected of being "Red" or "foreign spies" were interrogated mercilessly. Two days before Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested, for example, a suspected anarchist fell to his death from the fourteenth floor of the bureau's New York branch office where he had been detained. It was rumored that unable to endure the severity of his interrogation he had committed suicide, or that he was

pushed by G-men. Among the comrades active in the movement demanding his release had been Sacco and Vanzetti.

The Bureau of Investigation compiled a Weekly Summary of Radical Activities from reports sent in by branch offices in major cities throughout the United States. These reports contained information about anarchist and socialist groups, the Communist party, labor union activities, and strikes, but they also covered the American Legion and other patriotic and right-wing groups. Reports about labor strikes were nearly always stamped "Attention of Mr. J. E. Hoover." The bureau also collected detailed reports about matters related to public security overseas. Naturally developments in the Soviet Union constituted the bulk of the information, but reports on "Japanese Affairs," including domestic strikes in Japan, gradually increased. Reports on activities of Japanese in the United States were limited, however, and information about Japanese in Hawaii was essentially nonexistent for this period. But the bureau did maintain files on Japanese "non-immigrants," or hiimin (the category used by the Japanese government under the Gentlemen's Agreement). Apparently suspecting all such people of espionage activities, the names of all Japanese on passenger lists of ships putting in to port were reported. No attention was paid to Japanese like T. Tsutumi who disembarked in Hawaii. But his name did turn up in reports from the Los Angeles branch office of the Bureau of Investigation in reports of labor unrest on the West Coast of the mainland:[1]

T. Tsutsumi; a strike leader and one of the leaders of the Japanese Federation of Labor. (January ?(unknown), 1921)

Tsutsumi, Takashi; subject attended the conference of the Hawaii Laborers' Association. (December 1, 1919)

Tsutsumi, T.; subject was Secretary of Hawaiian Laborers' Association at the time of strike in 1920, and was principal figure in directing strike activities. (September 10, 1921)

As there was no bureau branch office in the district of Honolulu and the Hawaiian Islands, the investigative reports were issued by the Los Angeles or San Francisco office.

The Los Angeles branch office investigative file on "T. Tsutsumi" dated January 13, 1921, reads as follows:

Tsutsumi one of the leaders of the Japanese Federation of Labor is considered by Informants as a very dangerous agitator and a Radical Socialist . He is highly educated in Japanese, being a graduate of the Imperial University at

Tokio [mistake for Kyoto Imperial University]. . . . He is a very fluent speaker, very radical in his views. The laborers at present worship him like a god and believe whatever he tells them. . . . Tsutsumi, in a speech, told the Japanese that if they did not win he would commit Hari Kiri, that it would be unpardonable sin if the Japanese did not win and that in that event he would suicide. He said that the Sumitomo bank had agreed to advance $200,000 to the strikers in case of an emergency and that the Yokohama Specie Bank stated that this is false as the bank will not advance money without good security .[2]

In short, Tsutsumi was put on the bureau's blacklist as one of the most radical Japanese residing in America and requiring special observation.

A Japanese Named "T. Tsutsumi"

The Bureau of Investigation files all refer to Takashi Tsutsumi or T. Tsutsumi, but English-language newspapers in Hawaii sometimes referred to him as N. Tsutsumi and treated him as an entirely different person. When Tsutsumi took the stand at the Sakamaki dynamiting trial, he was first asked by the prosecutor which initial was correct. The character for his given name was pronounced "Noboru," but it is more commonly read as "Takashi." The mistake followed him around even in Japan.

Noboru Tsutsumi was born on April 8, 1890, in Kozuhata[*] , Eigenji town, Kanzaki-gun, Shiga prefecture. Kozuhata is a village nestled in a mountain valley of lotus fields bordering on Mie prefecture. Most of the inhabitants made their living from woodcutting and charcoal making. The number of families living in the village today is 168, three times that in the 1890s, and the village is now famous as a place to view maple foliage in the autumn. One of the two temples in the village, Jogenji[*] of the Higashi Honganji sect, was administered by the family into which Noboru Tsutsumi was born. He was the third son, with two older brothers and two younger sisters. As he grew up the villagers called Noboru "temple boy."

Since his father, Reizui Kurokawa, the fifteenth-generation chief priest, had a weak constitution, he was not a very dominant force in the family. His mother, Masano, who had come from the neighboring village's temple, took charge of everything. Masano was Reizui's cousin. According to her nephew Hajime Furukawa (b. 1897), second son of her oldest brother who inherited the temple where Masano was born, Masano was the one who actually ran the Jogenji temple and cultivated some fields as well. Since Furukawa's mother had died when he was an

infant, Masano took on that role. She never raised her voice to scold him or her own children.

According to Furukawa, his cousin Noboru was the child most like Masano, not only in appearance but also in personality. Furukawa was attached to his cousin, whom he called "No-san[*] ," and often followed him around. It was No-san who took him into the nearby mountains and taught him which leaves and berries were edible. No-san was extremely adept at catching loaches in the rice paddies. Noboru was also known as a "bright boy" from his days at Kozuhata[*] primary school, which still stands at the crest of the hill above Jogenji[*] temple.

The temple raised silkworms as a side business. Shelves for spring and summer breeds of silkworms lined all the rooms but the main worship hall. Noboru and the other children diligently gathered mulberry leaves for the silkworms in large baskets on their backs. Silkworms were the only source of the temple's cash income. In a poor village like Kozuhata, offerings to the temple consisted of rice and vegetables harvested in the fields. The priest's family did not want for food, but there was never much cash on hand. The eldest son, Eseki, who knew he was to succeed his father, did not study hard. But the second son, Ekan, and Noboru, four years younger, were gifted students, and their school tuition came entirely from the income earned by the silkworms. After graduating from upper primary school both went off to normal school.

On finishing fourth grade many of the boys from this area were sent to Kyoto and Osaka to become apprentices, dreaming of the day when they would set up their own shops and become full-fledged merchants in the Omi[*] region.[3] Unlike the other village families, the priest had his dignity to consider and could not send his children off to be apprenticed to shopkeepers. Neither did the family have the means to provide their sons with advanced education. Normal school was the only place they could receive more schooling without paying tuition. Normal school students boarded for one year of preparatory subjects and four years of regular work, and all fees, from books to uniforms, were covered at public expense. When there were other necessary expenditures, public-spirited temple parishioners helped out.