Preferred Citation: Bernstein, Laurie. Sonia's Daughters: Prostitutes and Their Regulation in Imperial Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9199p2dt/

| Sonia's DaughtersProstitutes and Their Regulation in Imperial RussiaLaurie BernsteinUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1995 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Bernstein, Laurie. Sonia's Daughters: Prostitutes and Their Regulation in Imperial Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9199p2dt/

Acknowledgments

This book would never have seen completion without the encouragement and assistance of my loved ones, friends, and colleagues—many of whom overlap. I want to begin by thanking the people who were helpful to me in one way or another in the days when this was still a doctoral dissertation: Andrea Bass-Brawer, Lois Becker, Zita Bekes, Laird Boswell, Inga Bruk, Esther Cohn-Vargas, Carole Curtis, Valerii Danchenko, Carolyn Dean, Linda Edmondson, Stephen Frank, Rose Glickman, Jane Hedges, Shimon Iakerson, Richard Johnson, Julie Liss, Sergei Maksimov, Lynn Mally, Gary Marker, Louise McReynolds, Robert Moeller, Csaba Nemes, Joan Neuberger, Jan Olbertz, Suzanne Qualls, Helen Schwartz, Daniela Steila, Mark Steinberg, G. A. Tishkin, Nina Zonina, and Andrei Zonin.

I also received assistance from librarians and archivists in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) at the Library of the Academy of Sciences (BAN), the Central State Historical Archive (TsGIA), and the Central State Archive of the Leningrad Region (TsGALO). In addition, I would like to thank librarians at the University of California, Berkeley, the Hoover Institution, the New York Public Library, the New York Academy of Medicine, the National Library of Medicine, and the Library of Congress. Jim Fraser from the library at Fairleigh Dickinson University (campus at Madison, New Jersey) and Ben Goldsmith at the New York Public Library helped me find the appropriate illustrations.

This project would never have seen the light of day without Richard Stites, who was the first Western historian to consider the problem of prostitution in Imperial Russia and who kindly encouraged me to ex-

plore the issue in depth. I must also thank Barbara Engel for sharing with me a bibliography on Russian prostitution that proved invaluable in getting this work started.

My remarkable professor at Merritt Junior College in Oakland, Eve Wallenstein, sparked my interest in Russian history. If not for the fine example she set as a teacher, I never would have become one myself. I am also grateful to my dissertation advisers, Nicholas Riasanovsky, Gail Lapidus, and Ruth Rosen, for their encouragement, time, and assistance. Most of all, I want to acknowledge my debt to the chair of my dissertation committee, Reginald Zelnik, for the hours he spent reading drafts of my work, for his suggestions, for his patience with me when I was a graduate student, for his guidance in helping me to make sense out of "Sonia's daughters," and, finally, for giving this project its fitting title.

Several organizations provided me with financial assistance which supported the research and writing of this work. While I was conducting dissertation research, I received funding from the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX), and the Department of History and Center for Slavic and East European Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. The American Association of University Women Education Fellowship Program and the Mellon Foundation contributed generously to my support while I was writing my dissertation. During the post-doctoral phase, I received grants from the American Council of Learned Societies/Social Science Research Association, IREX, and Rutgers University.

Since I began revising the dissertation, several individuals have offered valuable suggestions. I would like to thank Laura Engelstein, Adele Lindenmeyr, David Ransel, Christine Ruane, Gerald Surh, William Wagner, and Elizabeth Waters in this regard. I am also grateful to my women's book club in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and to the members of the Delaware Valley Seminar on Russian History. Sheila Levine of the University of California Press has been more than patient with me over the long haul from completed dissertation to finished manuscript. In the final stages of revising the manuscript, suggestions and support from Carolyn Dean, Joan Neuberger, and Andrew Lees proved extremely helpful. Janet Golden, in particular, helped guide me through the difficult, ultimate revisions. I am deeply indebted to Janet for giving this work a final and close reading, and for bringing to it her keen intelligence and fine editorial skills.

Though many eyes have been on Sonia's Daughters, all errors and misguided flights of historical fancy are very much my own.

The list is getting long, but I cannot stop without acknowledging the love and encouragement from my family. My mother, Priscilla Bernstein, who died in 1982, would have been so proud to see the published me. The subject of my research has always embarrassed my loving father, Sylvester Bernstein, but that has never stopped him from supporting my decision to pursue Russian history as a career, or from doing his best to understand my choices. Sara Mebel', my dear relative in Moscow, was of great help in translating some difficult passages, sending updates in current newspapers, and frying potatoes. My wonderful six-year-old son, Perry Weinberg, made no scholarly contributions to speak of, but the joy that he brings me more than compensates for the many times he has leaned on the computer keys. Last, but never least, I owe my greatest thanks to Robert Weinberg. Since we met in 1979, he has shared his research and ideas with me. He rescued me in the early days of graduate school by taking me to Ramones concerts and teaching me the joys of roller derby. In 1981, he had the foresight to suggest that prostitution would be a worthwhile dissertation topic. His attentive, repeated readings of my chapters and grant proposals, and his insightful suggestions have been above and beyond the call of duty. By marrying me in 1986, he demonstrated how the categories of "colleague," "friend," and "loved one" could indeed overlap—in the best of all ways.

Finally, I want to acknowledge my debt to a skeleton in the Bernstein family closet—my great-great-grandmother, who is whispered to have managed a brothel in Russian Poland.

Introduction

"I ask you: what has Russian literature squeezed from all the nightmare of prostitution? Just little Sonia Marmeladova."

From Aleksandr Kuprin, Iama (1912)

Carrying a parasol and clad in a "fourth-hand, flowery silk dress . . . with its immensely long, ridiculous train and vast crinoline," Dostoevsky's Sonia Marmeladova could not be mistaken for anything but "indecent."[1] "Fallen women" like Sonia figured prominently not only in the fiction of nineteenth- and early, twentieth-century Russia, but also in journalistic and anecdotal accounts. Prostitutes were a fixture on the main streets of Russia's cities—along Kiev's Kreshchatik, in Odessa on Deribasovskaia Street, and in Kazan on the Voskresenka. In Moscow, prostitutes "impudently badger[ed] male passers-by and importunately offer[ed] their services, spewing forth foul language, pushing those they [came] across, squabbling with cab drivers and amongst themselves."[2] The poorer prostitutes in St. Petersburg congregated in the seedy neighborhoods around the Ligovka, the Viazemskii monastery, and the setting for Crime and Punishment, Sennaia Square's Haymarket.[3] Better-

[1] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment, trans. Michael Scammell (New York: Washington Square Press, 1963), p. 192.

[2] Iurii Iu. Tatarov, "Postanovka prostitutsii v gorode Moskve," in Trudy pervago vserossiikago s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami i ego prichinami proiskhodivshchago v S.-Peterburge s 21 do 25 aprelia 1910 grada, vol. 2 (St. Petersburg, 1911), pp. 396–97.

[3] A. Chivonibar, "Torgovlia zhivym tovarom," in Bosiaki. Zhenshchiny. Den'gi . (Odessa, 1904), p. 63. See also Prostitutsiia v Rossii: Kartiny publichnago torga (St. Petersburge, 1908), pp. 154–55.

heeled women sought clients along lively Nevsky Prospect, the scene of Nikolai Gogol's story about an artist who is ruined by his fantasies of a prostitute.

A Kazan journalist described the local prostitutes as "blondes, brunettes, tall, short, old, young, some still slips of things [devchonki ]," wearing fur coats or cloaks, with little caps, hats, or kerchiefs on their heads. Readily identifiable by signs of their trade—painted lips, rouged cheeks, and finery that seemed to mock the decorous dress of the proper lady—prostitutes might also be recognized from the look they cast at potential customers. Unlike "honest' women who remained elusive and demure, prostitutes gazed at men directly. Their "long, expressive glance," wrote the journalist, blended "restless curiosity, the timidity of a beaten dog," and "entreaty" with erotic promise.[4]

In 1843, bowing to prostitution's seeming inevitability, the tsarist Ministry of Internal Affairs began to regulate commercial sex in the Russian empire. A compromise between absolute prohibition and decriminalization, "regulation" purported both to police the behavior of lower-class women and to curb the spread of venereal disease. "Medical-police committees" oversaw the operation of brothels and issued licenses known as "yellow tickets" to prostitutes, obligating them to appear for periodic medical examinations. Authorities incarcerated in hospital wards prostitutes believed to suffer from venereal diseases, releasing them only when the more obvious symptoms of infection abated.

Official counts in 1889 put the number of yellow-ticket holders at somewhere between 17,600 and 30,700.[5] Policemen arrested thousands more each year on suspicion of prostitution. Not all of these women were prostitutes—many former prostitutes remained on the lists, mistakes were made, and overzealous policemen improperly railroaded some women into the system. But, significantly, officials believed that only a fraction of the women who exchanged sex for money had been counted and inspected. High rates of venereal diseases among soldiers, male civilians, and even peasants in the countryside seemed to prove that prostitutes were everywhere and that they presented a serious threat

[4] Aleksandr N. Baranov, V zashchitu neschastnykh zhenshchin (Moscow, 1902), pp. 42–44.

[5] The Medical Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs provided a high number of 30,762. Cited in Konstantin L. Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," in Trudy Vysochaishe razreskennago s"ezda po obsuzhdeniiu mer protiv sifilisa v Rossii, vol. 1 (St. Petersburg, 1897), p. 20. A census for the same year conducted by the Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs quoted the smaller figure of 17,603. A. Dubrovskii, ed., Statistika Rossiiskoi Imperii, vol. 13 (St. Petersburg, 1890), p. xi. I have not been able to determine the reason for the discrepancy between these two ministry totals.

to public health. To tsarist authorities, regulation seemed like the best strategy for tackling both these problems.

Although it was not implemented uniformly, throughout the Russian empire, regulation remained in effect from 1843 until the overthrow of the tsarist regime in February 1917. As state policy, regulation coincided with the era of late Imperial Russia's most momentous transformations, including the emancipation of the peasantry in 1861, the government-financed industrialization drive of the 1880s and 1890s, the revolution of 1905, and World War I. Yet even as social and economic structures changed and the autocratic political order underwent repeated assaults, regulation stood firm. The state never stopped treating prostitution as a "necessary evil" and never ceased to define prostitutes as women in need of supervision.

The tenacity of regulation reflects the fact that one aspect of Russian life stayed relatively constant: that of gender—the way in which male and female roles were socially constructed. The state enshrined the gender system in legal codes and rules that institutionalized male and female difference, such as the law that a wife "obey her husband as the head of the family" and render unto him "unconditional obedience."[6] The regulatory system was a critical expression of this gender order in the way it created a category of "public women" (publichnye zhenshchiny ) whose bodies were supposed to be available to clients, doctors, and policemen on demand. The ideology of male and female difference provided regulation with a steady anchor, enabling the yellow ticket to weather historical currents relatively intact.

Central to this ideological underpinning of regulation was an understanding of sexuality based on gender difference. State officials and educated society conceived of males as requiring outlets for their natural sexual energy, of females as exempt from such needs. Consequently, women who engaged in prostitution were seen either as having been tricked into acting sexually—against their nature—or, at the other extreme, as depraved by definition. In both instances, they deserved medical and police supervision. Men, by contrast, could patronize prostitutes without any interference. In keeping with this double standard of sexual morality, prostitutes were acknowledged as necessary to men's physio-

[6] Svod zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, vol. 10, pt. 1 (1914. ed.), quoted in Dorothy Atkinson, "Society and the Sexes in the Russian Past," in Women in Russia, ed. Dorothy Atkinson, Alexander Dallin, and Gail Warshofsky Lapidus (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977), p. 33. See also William Wagner, "The Trojan Mare: Women's Rights and Civil Rights in Late Imperial Russia," in Civil Rights in Imperial Russia, ed. Olga Crisp and Linda Edmondson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989).

logical well-being at the same time they were vilified as "fallen women." Regulation exacerbated their position by setting them apart and branding them as threats both to public health and the social order.

Gender worked in tandem with class to define who would fall under state surveillance: the regulatory system primarily embraced women from the lower classes. Economic prospects available to these women expanded while regulation was in force, but not sufficiently to provide them with the money they needed to flourish. In the countryside, peasant custom tended to keep women from gaining control over household land; in the cities, female workers were paid one-half to two-thirds of the (low) wages earned by men. Even though industrialization created jobs for tens of thousands of women, there were few paths to female economic independence. As if by design, the wages of working women were too meager and too uncertain to sustain them.

Gender made women economically vulnerable, but it also afforded them the opportunity to supplement their salaries with prostitution or to give up "honest work" completely. Prostitution remained the one (predominantly female) trade that seemed to promise both good money and freedom. Most prostitutes, in thrall to brothelkeepers, exploited by landlords and pimps, and stricken with alcoholism and disease, failed to see those promises materialize. Nevertheless, prostitution had its attractions when compared to other forms of female labor and always held out the possibility that commercial sex could provide an exit from a life of poverty.

Prostitution and its regulation were integral to Russia's structures of gender, class, and politics. Gender ideology and the economic system together guaranteed that there would be a supply of women ready to satisfy the demands of men. The overwhelming majority of prostitutes came from the lower classes, but males from all social strata depended on prostitutes for sexual relief. Sex with prostitutes violated the moral precepts of religion and ethics, but it was as woven into the fabric of Russian society as the larger patriarchal and hierarchical threads. The government for its part strove to protect prostitutes' clients as well as the overall polity through the regime of the yellow ticket.

Regulation was not unique to Russia. In fact, it had been imported from Paris's police des moeurs, and analogous rules governed prostitution in most of continental Europe.[7] Throughout Europe in the late nine-

[7] On prostitution in Britain and the United States, see Judith Walkowitz, Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980); Ruth Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution America, 1900–1918 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982). Other recent histories of prostitution include Alain Corbin, Women for Hire: Prostitution and Sexuality in France after 1850 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990); Mary Gibson, Prostitution and the State in Italy, 1860–1915 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986); Jill Harsin, Policing Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985); Linda Mahood, The Magdalenes: Prostitution in the Nineteenth Century (New York and London: Routledge, 1990).

teenth and early twentieth centuries, regulation was a troublesome and controversial system that raised questions about medical ethics, civil liberties, police authority, and class and gender equality. Regulation prevented a woman from engaging in prostitution on a casual basis; once registered, she generally had no choice but to earn her living from commercial sex alone. Moreover, regulation gave clients illusory notions about the health of registered prostitutes, for physicians often failed to diagnose diseases accurately, and prostitutes contracted and spread infections between examinations. Mandatory hospitalization also failed to justify itself medically. Not only were hospitals unable to house prostitutes through syphilis's elusive contagious periods, but medical science lacked reliable methods for identifying and curing venereal diseases. Regulation, furthermore, created a category of prostitutes that resisted registration. Afraid of detection, many women who genuinely needed medical attention avoided doctors for fear of regulation's consequences. Finally, by limiting compulsory, medical supervision to the women and exempting their customers, regulatory agencies defeated their very purpose, since men remained free to spread venereal diseases.

Prostitutes in all of Europe lived and worked in contrasting degrees of degradation, luxury, and exploitation, with customers ranging from the poorest working man to the richest aristocrat.[8] Russian women turned to prostitution for reasons that varied little from those that motivated women in Europe: financial need, the desire to make "easy money," desperation, unemployment, and personal inclination. As happened in nineteenth-century Europe, prostitution in Russia became associated with the combined traumas of industrialization and urbani-

[8] On prostitution in Imperial Russia, see Barbara Alpern Engel, "St. Petersburg Prostitutes in the Late Nineteenth Century: A Personal and Social Profile," Russian Review 48, no. 1 (January 1989): 21–44; Laura Engelstein, "Morality and the Wooden Spoon: Russian Doctors View Syphills, Social Class, and Sexual Behavior, 1890–1905," Representations, no. 14 (Spring 1986): 169–208; Laura Engelstein, "Gender and the Juridical Subject: Prostitution and Rape in Nineteenth-Century Russian Criminal Codes," Journal of Modern History 60 (September 1988): 458–95; and Richard Stites, "Prostitute and Society in Pre-revolutionary Russia," Jahrbücher für Osteuropas 31 (1983): 348–64. See also Laurie Bernstein, "Yellow Tickets and State-Licensed Brothels: The Tsarist Government and the Regulation of Prostitution," in Health and Society in Revolutionary Russia, ed. Susan Gross Solomon and John F. Hutchinson (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1990).

zation, and, like prostitutes in European countries, many Russian prostitutes suffered from venereal disease and alcoholism. But in other important respects, prostitution in Russia differed. Conditions peculiar to the Russian economy, political environment, and society itself affected the character of prostitution and regulation.[9]

To begin with, regulation took shape in the context of strong patriarchal and paternalistic traditions that lingered well into the twentieth century. Russian society was based on a three-tiered hierarchy of rule, with the father as head of the peasant household, the lord as master of his peasants, and the tsar as the "little father" (batiushka ) of them all. This arrangement was meant to encompass, protect, and restrain all of the ruler's subjects. However, the system began to break down in the mid-nineteenth century, with enough individuals falling through the cracks to warrant official concern. By regulating prostitutes, the state could monitor women who no longer had fathers or lords to control their behavior. Regulation was designed to protect public health, but it was also in place to shore up the patriarchal order.

Second, regulation represented one more restriction on an already encumbered population. The post-emancipation social structure of Imperial Russia adhered to a system of estates (sosloviia ), despite the transition to class society. The population of the Russian empire fell within legal social groupings that restricted each estate's occupational and geographic horizons and delineated its respective rights and obligations. The majority of individuals were part of the peasant category and lived on the land, but even many of the Russian workers in towns and cities were still formally inscribed in the legal peasant estate. Post-emancipation Russia therefore had anomalous qualities tied to the conventions of serfdom and the fact that the tsar's subjects never knew legal equality.

Third, notions peculiar to Russia about the peasantry and its role also affected the way prostitution was interpreted. Russian educated society analyzed prostitution in ways similar to the middle and upper classes in Europe, but native cultural traditions also influenced the nature of the discussion, particularly Russia's "populist" legacy of romanticizing the peasantry. Many observers characterized prostitutes as innocent peasant girls whose naïveté had left them vulnerable to the machinations of

[9] Paris regulations, as well as comparable rules for Berlin, Hamburg, Vienna, and Denmark, are in Abraham Flexner, Prostitution in Europe (New York: The Company, 1914), pp. 405–52.

brothel owners and "white slave traders." A State Duma deputy displayed an extreme side of this view when, in face of much evidence to the contrary, he denied an allegation that peasant families were sending their daughters to an annual fair in Nizhnii Novgorod to earn money as prostitutes. "The Russian peasant population," he declared, "has never engaged in this sort of business and never shall."[10]

Fourth, although women throughout Europe faced terrible workplace oppression, Russian female workers were confronted with an especially hostile environment, working as they did up to sixteen hours a day in unsanitary conditions for wages well below subsistence levels. Industrialization in the Russian empire lagged far behind western and central Europe until the state promoted rapid, massive economic development at the end of the nineteenth century. That is, when most of Europe had already absorbed the shocks of industrialization and urbanization, Russia was just beginning to feel them. Both male and female workers in the Russian empire lacked the benefits of effective protective legislation or trade unions to redress their grievances. Women occupied the lowest rungs of the occupational ladder as domestic servants and unskilled and semiskilled laborers.[11] While women everywhere, burdened with low wages, job discrimination, and sexual harassment, often found that prostitution spelled the difference between starvation and survival, Russian women had even fewer options. The dual legacy of serfdom and patriarchy kept them in an unusually downtrodden position, while Russia's legally structured estate system and the laws against labor organizing placed strict limitations on their social and geographic mobility.

[10] Gosudarstvennaia Duma. Stenograficheskie otchety (St. Petersburg, 1909), tretii sozyv, sessiia 2, zasedanie 109, May 8, 1909, p. 899.

[11] On women workers, see Rose Glickman, Russian Factory Women: Workplace and Society, 1880–1914 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984). For discussions of Russia's working class, see Victoria Bonnell, Roots of Rebellion: Workers' Politics and Organizations in St. Petersburg and Moscow, 1900–1914 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983); Joseph Bradley, Muzhik and Muscovite: Urbanization in Late Imperial Russia (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985); Laura Engelstein, Moscow, 1905: Working-Class Organization and Political Conflict (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982); W. Bruce Lincoln, In War's Dark Shadow: The Russians before the Great War (New York: The Dial Press, 1983); Gerald Surh, 1905 in St. Petersburg: Labor, Society, and Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989); Robert Weinberg, The Revolution of 1905 in Odessa: Blood on the Steps (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993); Charters Wynn, Workers, Strikes, and Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend in Late Imperial Russia, 1870–1905 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992).

Fifth, questions of Russia's relations to the West occupied a prominent place in the minds of privileged society. In Western industrializing societies, prostitution became a symbol of what had gone wrong since the advent of "the city" and "the machine." Along with its dread companion, venereal disease, prostitution represented the corruption of sexuality itself.[12] It mattered little that prostitution had existed for centuries; counterpoised against the transformations of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, this trade assumed new cultural meanings. In Russia as well, prostitution took on symbolic importance as one of the malignant aspects of modern urban life. But because policies promoting industrialization were associated with the West, prostitution also became another lens through which to view "westernization." As one contemporary observer claimed, Russia had been unsullied by the Western vices that nurtured the growth of prostitution until Peter the Great looked to the West for technology and guidance and the German-born Catherine the Great increased burdens on the serfs. Nonetheless, prostitution never "attained such dreadful proportions" as it had "beyond the border."[13]

Finally, the civil liberties cherished in the emergent bourgeois societies of western Europe never blossomed in Russia. Though revolution in 1905 loosened some of the tight shackles on society, censorship and police repression persisted. Individuals in the Russian empire felt political oppression not only as a lack of rights, but as an inability to develop organizational traditions outside state control and tutelage. Laws limiting the actions of educational institutions, charities, and professional groups stunted the growth of Russia's civil society. While labor unions and political parties were changing the nature of western and even central European states, similar organizations in Imperial Russia—at least until 1906—had to remain underground, their members subject to arrest and exile. In the years prior to World War I and the revolutions of 1917, Russian prostitution served as an ideal locus for the various strains of social dissatisfaction and political dissent. The tsarist government's control of prostitution meant that the general heading of prostitution also embraced larger political questions concerning the role of the state.

[12] Allan M. Brandt has argued that venereal disease symbolized "corrupt sexuality" and appeared to be a "sign of deep-seated social disorder." See his No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 5.

[13] K. F. Griaznov, Publichnye zhenshchiny: Kartiny sovremennoi i drevnei prostitutsii u vsekh narodov (Moscow, 1901), pp. 108–10, 170, 172.

Prostitution and its regulation impinged on questions relating to labor, sexuality, urbanization, public health, and the status of women, and thus easily lent themselves to critiques of existing social, economic, and political structures.

The singular qualities of Russia's experience of prostitution suggest that it would be most fruitful to examine prostitution and regulation contextually and thematically, rather than chronologically. The advantages of the thematic approach are that, first, it provides a perspective from which to study the historical actors as they went about their business—the bureaucrats who contrived regulation, the doctors who conducted it, the policemen who enforced it, the members of society who accepted it or challenged it, and the prostitutes who lived with it. Second, it reveals the enduring power of the state as the author and executor of regulation. Last, the thematic approach makes clear how deeply entrenched was the system of gender in all of the factors that influenced prostitution and its regulation.

That is not to argue that historical events did not affect prostitution and regulation in significant ways; to be sure, historical developments strongly affected prostitution. Nevertheless, three key factors stayed constant: gender ideology, the role of the state, and the identification of women who engaged in prostitution as a class apart. Each chapter in this work therefore provides a different angle from which to view Russian prostitution and regulation. Taken together, they supply a panoramic view that is connected by persistent ideologies of gender, class, and power. The survival of prostitution—even into the Soviet period—underscores the way gender is a fundamental construction for the ordering of society.

This work begins with the advent of regulation, exploring the rules developed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In the mid-nineteenth century, concerns about morality, public order, and public health materialized in the form of regulation. The rules promulgated in 1843 were broken more than they were followed, and they left prostitutes and other women vulnerable to abuse and exploitation by policemen and other authorities. Yet they served an important purpose: they created a framework in which the state could order the lives of lower-class urban women.

When we understand the model world that Russian bureaucrats constructed for Russia's prostitutes, we can comprehend how women operated within and outside it. The second chapter examines how the regulatory system affected the lives of all women from the urban lower classes,

whether or not they were prostitutes. The existence of regulation necessitated coping with two groups that challenged the whole logic of the system, juvenile prostitutes and unregistered ("clandestine") prostitutes. Regulation also fashioned another stage—the medical-police clinic and venereal ward—on which prostitutes, doctors, and policemen acted out their prescribed roles.

Chapter 3 situates prostitution in Russian society, both as a response to male demand and female supply. It looks at how prostitution fit into the overall conception of male and female sexuality and then examines it in the light of the economic structure by discussing the wages and conditions that affected the female work force. Who were the women who turned to prostitution in Russia? Where did they come from? What kind of experiences did they have before they made the decision to engage in prostitution?

Chapter 4 explores the reasons that impelled women to prostitution, first from the point of view of society and then from that of the women themselves. For educated society, prostitution functioned symbolically, with prostitutes either falling into commercial sex as passive victims or because they consciously chose a path of degeneracy. When we look at the prostitutes' own reasons, the meaning of their trade becomes more prosaic and, consequently, more comprehensible.

The world of the Russian brothel is the subject of the fifth chapter. Brothels were as much objects of prurient fascination as they were anathemas to a society that liked to think of itself as morally sound. Brothel prostitution and "white slavery"—forcing women into prostitution by kidnapping, drugging, and beating them—were synonymous in Russia. Although forced prostitution did exist, the reality of brothel life involved less sensational kinds of oppression—debt peonage, exploitation, and disease. The myth of widespread white slavery, particularly that element of the myth which labeled Jews as the chief perpetrators, nevertheless allowed Russians a comfortable way to pigeonhole prostitution and affirm popular, antisemitic images. The outcry against brothel prostitution and white slavery also helped fuel a grassroots movement to rid Russia of licensing altogether, with opponents of brothels battling in city councils and district meetings.

Chapter 6 discusses how men and women from Russia's privileged strata interacted with prostitutes as their self-appointed saviors in charitable societies. It explores the philosophy and routine of two institutions designed to rehabilitate prostitutes and the activities of Russia's main organization to prevent prostitution, the Russian Society for the

Protection of Women. Finally, it examines the conflict between two groups with antithetical definitions of prostitution—salvationists and socialists.

Official state attempts to reform regulation are the subject of chapter 7. Essentially, the state was stuck in the contradictory role of acting as both the protector of the Russian people and the sponsor of women who traded in sex. One way officials handled this situation was by trying to perfect regulation so that it served to protect not only prostitutes' customers and society, but, paradoxically, the prostitutes themselves. Criticism of regulation spurred these efforts and illuminated the hole that the state had dug for itself by regulating prostitution in the first place. For more than a decade, regulation underwent various projects of reform, most of which never moved off the paper on which they were scribbled. But governmental self-criticism in this area encouraged the efforts of opponents of regulation, who used critiques of the medical-police committees to pursue their own visions.

The final chapter analyzes the attempts by Russian educated society to abolish regulation altogether. Like "abolitionists" in Europe, opponents of Russian regulation attacked the system for its medical shortcomings, the way it oppressed women, and its institutionalization of the sexual double standard. But, although society raised a fairly strong voice for abolition of regulation at the First All-Russian Congress for the Struggle against the Trade in Women and Its Causes (Pervyi vserossiiskii s'ezd po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami i ego prichinami) in 1910, the state turned a deaf ear. As much as it recognized regulation's many flaws, it could not see its way to turning prostitutes loose. Ironically, for all their antipathy to regulation, neither could the self-styled "abolitionists."

There is, finally, another group that explored and confronted Russian prostitution—Russian writers. Elevated into powerful literary symbols by authors like Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Gogol, and Chekhov, prostitutes became female archetypes who either disillusioned the men with whom they associated or raised them to a higher plane of being.[14] Dostoevsky's

[14] For discussions of literary images, see George Siegel, "The Fallen Woman in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature," Harvard Slavic Studies 5 (1970): 81–107; Mariia I. Pokrovskaia, O padshikh: Russkie pisateli o padshikh (St. Petersburg, 1901). Examples of literature with prostitutes as characters include Nikolai Gogol, "Nevsky Prospect"; Nikolai Nekrasov, "When from Thine Error, Dark, Degrading"; V. Krestovskii, "Pogibshee, no miloe sozdanie"; S. Nadson, "Slezy"; Vsevolod Garshin, "An Incident" and "Nadezhda Nikolaevna"; Leonid Andreev, The Dark; Nikolai Chernyshevsky, What Is to Be Done?; Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment and Notes from Underground; Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina and Resurrection; Anton Chekhov, "A Nervous Breakdown"; Aleksandr Kuprin, Iama .

Sonia, one of literature's most memorable characters, worked the streets, but her selflessness and inner purity helped cleanse the blood from the hands of the murderer Raskolnikov. Because the image of Sonia informed all educated Russians' perception of prostitution—whether they believed in her or not—this work is called "Sonia's daughters."

Chapter 1

The State and the Yellow Ticket

Churches, icons, crosses, bells, Painted whores and garlic smells, Vice and vodka every place—This is Moscow's daily face.

Quoted in Olearius, Travels (1647)

The Birth of Regulation

The first official government policies in Imperial Russia treated prostitution as a serious crime against both public decorum and morality. As early as the seventeenth century, an order lumped "whoring" with fighting and robbery, stipulating that "streets and alleys should be strictly patrolled day and night" to prevent such occurrences.[1] In 1716, Tsar Peter the Great proclaimed that "no whores [bludnitsy ] will be permitted near the regiments." Women who violated his order ran the risk of being taken under guard and driven out of the area—naked. Two years later, Peter directed the police chief of the new city of St.

[1] I. E. Andreevskii, Politseiskoe pravo, vol. 2, p. 17, in Veniamin M. Tarnovskii, Prostitutsiia i abolitsionizm (St. Petersburg, 1888), p. 98; Mikhail M. Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma i razlichnye fazisy v istorii otnoshenii k nim zakonodatel'stva i meditsiny v Rossii," Trudy s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 2, p. 337. According to the Law Code of 1649, a beating from a knout awaited anyone who arranged "lecherous relations" between men and women.

Petersburg to stamp out "all suspicious houses, namely taverns, gambling parlors, and other obscene establishments."[2] His niece, the empress Anna, also refused to tolerate prostitution, ordering all "debauched" women kept by "freethinkers and innkeepers" to be beaten with a cat-of-nine-tails and thrown out of their homes.[3]

The prohibition of commercial sex assumed another character in the middle of the eighteenth century, now influenced by fears that linked prostitutes with the spread of venereal disease. In 1762, a home designated by St. Petersburg authorities "for the confinement of women of debauched behavior" became Kalinkin Hospital, an institution that would develop into Russia's most prestigious center for the treatment of venereal diseases.[4] The next year, women who had been named by soldiers as the source of their venereal infections were ordered confined within its walls. After "treatment," the ones with no visible means of support were deported to labor in Siberian mines.[5]

[2] Voinskie artikuly of April 30, 1716, cited in Arkadii I. Elistratov, "Prostitutsiia v Rossii do revoliutsii 1917 goda," in Prostitutsiia v Rossii, ed. Volf M. Bronner and Arkadii I. Elistratov (Moscow, 1927), p. 13. Peter's second decree is described in Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," pp. 337–38. Another source quotes a decree against houses suspected as sites for various "obscenities." See R. L. Sabsovich, "Reglamentatsiia prostitutsii i abolitsionizm, in O reglamentatsii prostitutsii i abolitsionizm (Rostov-na-Donu, 1907), p. 1.

[3] Ukaz of May 6, 1736, quoted in Elistratov, "Prostitutsiia v Rossii," p. 14.

[4] There is some confusion in the sources over the origins of Kalinkin Hospital. A nineteenth-century Russian physician dates Kalinkin from the 1750s, but admits that the hospital's history is obscure because records were not kept until after 1830. According to one Soviet source, from 1765 to 1774, women with venereal disease were treated not in Kalinkin, but in two merchants' homes on the Vyborg side of St. Petersburg. Others, however, name as the place to which such women were sent. John Alexander mentions a Kalinkin Institute that had been founded in 1783 to train German surgeons, but asserts that it had little significance until an 1802 merger with the Medical-Surgical Academy Mikhail Ia. Kapustin, Kalinkinskaia gorodskaia bol'nitsa v S.-Peterburge (St. Petersburg, 1895), pp. 3, 7; A. M. Kopylov, "Iz istorii pervykh bol'nits Peterburga," Sovetskoe zdravookhranenie, no. 2 (1962): 58–59; M. A. Frolova, "Istoriia stareishei v Rossii Kalinkinskoi kozhno-venerologicheskoi bol'nitsy," Autoreferat dissertatsii (Leningrad, 1960), p. 4; A. A. Martinkevich and L. A. Shteinlukht, "Iz istorii Kalinkinskoi bol'nitsy (175O–1950)," Vestnik dermatologii i venerologii, no. 1 (January–February 1951): 43–44; John T. Alexander, "Catherine the Great and Public Health," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 2 (April 1981): 195, 198. There is a brief description of Kalinkin Hospital in S. P. Arkhangel'skii, S. E. Gorbovitskii, S. T. Pavlov, O. N. Podvysotskaia, and L. A. Shteinlukht, "Kratkii ocherk razvitiia dermatologii i venerologii v Peterburge-Leningrade," Vestnik dermatologii i venerologii, no. 4 (July–August 1957): 45.

[5] This is called an ukaz by the empress Elizabeth in Elistratov, "Prostitutsiia v Rossii," p. 14, but it is dated more than a year after her death. In Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny k prostitutsii (Kazan, 1903), p. 23, the State Senate is listed as the author. See also Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia," Real'naia entsiklopediia meditsinskikh nauk, vol. 16 (St. Petersburg, 1897), p. 469; Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," p. 339.

Syphilis was of such concern to Catherine the Great that in her famous "Instructions" she referred to it as a disease that "hurried on the Destruction of the human Race." The empress urged that the "utmost Care ought to be taken . . . to stop the Progress of this Disease by the Laws."[6] During her reign, new regulations on public order made it illegal "to open one's own home or to use a rented home day or night for indecency [nepotrebstvo ]; to enter a home day or night for indecency; to support oneself or another through indecency."[7] Catherine's son, Paul I, decreed in 1800 that all women "who have turned to drunkenness, indecency, and a dissolute list" should be exiled for forced labor in Siberian factories. One source mentions how Tsar Paul compelled prostitutes to wear yellow dresses as a sign of their "shameful trade."[8]

Yet despite repressive laws, there is no doubt that prostitution thrived in Imperial Russia, sometimes with the permission of the authorities. In the mid-seventeenth century, a German observer of Russian life commented on the "insolence" of Moscow women and the scandalous public brothels. Aleksandr Radishchev, Russia's first "repentant nobleman," in his 1790 Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, complained of the "painted harlots on every street in both the capitals," and blamed the government for allowing prostitution to take place. Indeed, in direct contradiction to the Catherinian regulations, authorities in the late eighteenth century apparently designated certain sections of St. Petersburg for the operation of "free houses."[9]

Prostitution remained illegal, but in the 1840s the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del; hereafter MVD) initiated a policy of official toleration after the fashion of the Parisian police des moeurs . The state's decision to regulate prostitution had roots in the continental European tradition of the "medical police" that had associated public health with public order as early, as the eighteenth cen-

[6] Basil Dmytryshyn, ed., Imperial Russia: A Source Book, 1700–1917, 2d ed. (Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden Press, 1974), pp. 76–77 (emphasis in original).

[7] Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, vol. 21 (St. Petersburg, 1830), p. 480.

[8] N. I. Solov'ev, "Presledovanie prostitutok v tsarstvovanii Imperatora Pavla Pervago," Russkaia starina (February, 1916): 363–64; Belyia rabyni v kogtiakh pozora (Moscow, 1912), p. 48. For yellow dresses, see Griaznov, Publichnye zhenshchiny, p. 110.

[9] "Olearius's Commentaries on Muscovy," in Basil Dmytryshyn, ed., Medieval Russia: A Source Book, 900–1700 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967), p. 241; Alexander Radishchev, A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958), p. 170. See also S. Bogrov, "Prostitutsiia," Entsiklopedicheskii slovar' t-va F. Granat i K, vol. 33, p. 582. A Baku physician claimed that the first brothels were permitted in Russia during Catherine's reign. Arutuin A. Melik-Pashaev, "Prostitutsiia v gorode Baku," Svedeniia mediko-sanitarnago biuro goroda Baku (November–December 1913): 846.

tury.[10] But the regulation of prostitution was also one among many of Tsar Nicholas I's efforts to standardize and bureaucratize Russian society. Lev Perovskii, the tsar's ambitious new minister of internal affairs, reckoned the regulation of prostitution as part of his numerous programs of medical and police reforms.[11]

Like the prefect of the Paris police and many other nineteenth-century European administrators, Perovskii equated the control of venereal disease with the control of prostitution. Prostitutes were "public women," dangerous founts of disease whose very existence necessitated state intervention. But it was considered futile for the state to prohibit prostitution entirely; rather, authorities were now to recognize prostitution as an inevitable and necessary evil. It no longer sufficed to send prostitutes and women suspected of prostitution to Siberian mines, to beat them or to stigmatize them with yellow dresses; they were now to be tolerated for the sake of monitoring and control.

Perovskii's decision was influenced by the recent triumph of Dr. Alexandre-Jean-Baptiste Parent-Duchâtelet's formulation about prostitutes and prostitution in France.[12] According to a historian of French prostitution, "The nineteenth-century view of the prostitute was essentially that of Parent-Duchâtelet." This influential French physician published a major tome in 1836 that hailed toleration as a necessary evil engendered by the inevitability of prostitution.[13] Essentially, whether

[10] Catherine's concerns about syphilis mirrored central European notions of a "medical police." Indeed, in the late eighteenth century, J. P. Brinkman, author of Patriotische Vorschläge zur Verbesserung der Medicinalanstalten (1778), served as the personal physician for two Russian grand dukes. An advocate of a medical-police system, he believed that "the moral behavior of the people must be regulated by law so that dissipation will not sap their vital energies." George Rosen, "Cameralism and the Concept of Medical Police," in From Medical Police to Social Medicine (New York: Science History Publications, 1974), p. 140.

[11] Perovskii is characterized as a dynamic and ambitious administrator in Daniel Orlovsky, The Limits of Reform: The Ministry of Internal Affairs in Imperial Russia, 1802–1881 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), p. 30. Perovskii attempted to eradicate crime in St. Detersburg by organizing police raids and dispatching spies and agents provocateurs among the city's population. See Sidney Monas, The Third Section: Police and Society in Russia under Nicholas I (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961), p. 247. Perovskii was also instrumental in centralizing medical affairs under the recently organized Medical Council. Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del: Istoricheskii ocherk (St. Petersburg, 1901), p. 54. One year after Perovskii was appointed, a "medical-police regulation" called for the identification and isolation of urban residents with contagious diseases. Statute 562, Ustav meditsinskoi politsii, izd. 1842 g., quoted in Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, p. 78.

[12] See Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," p. 342.

[13] Harsin, Policing Prostitution, p. 102. To Parent-Duchâtelet, prostitution was an "indispensable excremental phenomenon that protects the social body from disease." Corbin, Women for Hire, p. 4.

prostitution was tolerated or not, men would continue to seek commercial sex, women from the lower classes would continue to oblige them, and venereal disease would continue to spread as a result. Thus, reasoned Parent-Duchâtelet, it was necessary to intervene, if only to stem the damage.

The advent of industrialization and the rise of a bourgeois class coincided with the evolution of regulation in western Europe. Russian regulation, however, was not connected with a perceptible growth in industry. In fact, Nicholas I was hostile to industrialization because he feared the social dislocation it produced. Until the late 1880s, Russia industrialized slowly and cautiously, ever wary of fostering a landless proletariat that would threaten the social order.[14] Nor had a bourgeoisie emerged in Russia to strive for political, economic, social, or cultural hegemony. Rather, regulation emerged in a more narrow stratum, the result of one ambitious individual's desire to make his mark during the reign of a tsar justly known as the "gendarme of Europe." Though European systems and ideas inspired Russia's toleration of prostitution, regulation emerged in a peculiarly Russian milieu and in a peculiarly Russian context. In other European states, the ground had to be prepared in order to launch regulation.[15] By contrast, no one paved the way in Russia for regulation; in an autocracy one had only to convince the tsar.

Whereas French regulation was tied to fear of the lower orders in the early part of the nineteenth century—when the "laboring classes" and "dangerous classes" were essentially synonymous to the bourgeois observer[16] —Russian cities involved a different kind of social geography. Free workers were an anomaly in a society mostly divided into lords and their serfs. Neither the worker nor the bourgeois "owned" the cities. With the exception of St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, and other provincial capitals, cities and towns within the Russian empire were mostly administrative centers for the execution of state duties. The great influx of rural migrants did not really begin in Russia until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, there were evidently enough women on the fringes of the patriarchal system in Nicholas I's Russia —

[14] See Reginald E. Zelnik, Labor and Society in Tsarist Russia: The Factory Workers of St. Petersburg, 1855–1870 (Stanford: University Press, 1971).

[15] For example, during the 1850s the writings of William Acton and W. R. Greg served this function in Great Britain. British attention to this issue also followed a sanitary movement that linked public order and public health. Walkowitz, Prostitution and Victorian Society, pp. 42, 70–71.

[16] Alain Corbin ties support for French regulation to the phenomenon described in Louis Chevalier's classic work, Laboring Classes and Dangerous Classes in Paris during the First Half of the Nineteenth Century . See Corbin, Women for Hire, p. 111.

daughters of artisans and tradesmen, daughters of serfs who had been sent to the cities to work, former serfs, domestic servants, soldiers' wives (soldatki )[17] —to warrant official concern. As Laura Engelstein has pointed out, "The original program of syphilis control targeted groups that had escaped the traditional, patriarchal institutions supposed to keep the dependent orders in line: peasants who left the village, women who had left the family."[18] An early twentieth-century tsarist bureaucrat characterized the shift to a policy of tolerating prostitution this way: "The interests of public morality fell victim to the interests of public health."[19] But regulation clearly represented more than a public health measure; it was also informed by the desire for an orderly social body, as well as a distinct interpretation of gender and sexuality. Despite peasant wisdom that saddled women with reputations as insatiable temptresses,[20] the authors of regulation tacitly accepted a more bourgeois vision of sexual desire—one that associated it exclusively with males. Male desire was considered so irresistible as to require gratification; female desire remained beneath mention or consideration. Regulation thus institutionalized this sexual order by monitoring the women who would cater to male sexual needs. Regulators also reasoned that by sanctioning the existence of a class of prostitutes, they were clearing the way for most women to remain virgins until marriage. As long as prostitutes were available, it was believed men would keep their hands off non-prostitutes.

Using Parisian regulation as its guiding light, an advisory commission organized by Perovskii in 1843 recommended establishing a trial system of toleration in St. Petersburg. The central government's Committee of Ministers approved the proposal before the year was out, but made it clear that it would not accept a plan for funding regulation from the prostitutes themselves. In the committee's words, a tax on "public

[17] Married to men with twenty-five-year obligations in the army, soldatki had reputations for loose morals. They constituted half of the women Paul I sent to Siberia, and they figured prominently among the women who turned children over to Russia's foundling homes until military reforms in the 1870s. David Ransel, Mothers of Misery: Child Abandonment in Russia (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), pp. 154–60.

[18] Engelstein also argues that regulation was "[i]n the classic tradition of enlightened despotism and the domestic tradition of paternalistic rule." Engelstein, "Morality and the Wooden Spoon," pp. 189, 194.

[19] Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," pp. 341–52.

[20] On peasant images of female sexuality, see Christine D. Worobec, "Temptress or Virgin? The Precarious Sexual Position of Women in Postemancipation Ukrainian Peasant Society," Slavic Review 49 (Summer 1990): 227–38.

women would not conform with the spirit of our laws because it would seem as though the government for its part was permitting the earning of a living through indecency."[21] Thus, the Committee of Ministers was careful to have the government's hands appear clean, even as those same hands signed the papers that countenanced state sponsorship of commercial vice. Though the system was frequently referred to by a cognate of the French réglementation (reglamentatsiia in Russian), the administration and eventually the public employed the native word for supervision or surveillance, nadzor .[22]

To establish nadzor on an empirewide basis, in October of 1843 the MVD's Medical Department requested all provincial governors to provide it with information on rates of venereal disease among the "common people" in their area of jurisdiction and to propose measures to halt the spread of these diseases. Interestingly, though many governors sounded an alarm about the rise of venereal disease, they did not attribute it solely to prostitutes; they also blamed military personnel, serfs who engaged in seasonal labor, and soldiers' wives. Suggestions to protect public health included ordering Russian Orthodox priests to admonish their flocks and instituting a regimen of periodic medical examinations for men, not women. One provincial governor, for example, proposed broad surveillance of the military, factory workers, shops, and taverns. But the Medical Department responded by asserting that women were in fact the chief source of venereal disease.[23]

Particularly influential was a report from a Major-General Akhlestyshev, the city governor of Odessa. The Black Sea port, it appears, had already implemented a program with policies reminiscent of Paris's police des moeurs . In Odessa, prostitutes were registered on police lists, obligated to undergo weekly examinations, and, if physicians diagnosed them as suffering from a venereal disease, incarcerated in the hospital.[24]

[21] Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," p. 343. Quote from Mariia I. Pokrovskaia, "Iarmarochnaia prostitutsiia," in Prostitutsiia, ed. Ape (St. Petersburg, 1906), p. 12; "Zakonodatel'noe predpolozhenie ob otmene reglamentatsii prostitutsii," Izvestiia S.-Peterburgskoi gorodskoi dumy, no. 21 (May 1914): 2074.

[22] Such an interpretation of the government's duty is well suited to Michel Foucault's analysis of other nineteenth-century disciplinary procedures. See, for example, Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (London: Allen Lane, 1977).

[23] Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," pp. 344–45.

[24] Ibid., p. 345; Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, pp. 74–76; Tsentral'nyi Gosudarstvennyi Istoricheskii Arkhiv (hereafter TsGIA), Upravlenie glavnago vrachebnago inspektora MVD (hereafter UGVI), fond 1298, opis' 1, delo 1730, "O nadzore za prostitutsiei," June 1910–December 1911, report of July 15, 1910, by privy councillor Mollerius.

Those three I's—identification, inspection, and incarceration—would ultimately serve as the linchpin of the empire's new system, guiding Russia's treatment of prostitution until the collapse of the tsarist regime in February 1917.

The Medical Police and Yellow Tickets

"Danger of disease? . . . A solicitous government looks out for that. It looks after and regulates the activity of brothels and makes lewdness safe. And doctors for a consideration do the same."

Pozdnyshev, in Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata

In the autumn of 1843, tsarist authorities organized a trial medical-police committee (vrachebno-politseiskii komitet ) for St. Petersburg under the MVD's Medical Department and in 1844 created a similar committee for Moscow.[25] By fits and starts, other Russian cities followed suit. The MVD issued specific rules pertaining to the regulation of prostitution several times: for Petersburg in 1844, 1861, 1868, and 1908, and for the entire empire in 1851 and 1903. Several cities, including Moscow, Minsk, and Nizhnii Novgorod, developed their own locally tailored systems of regulation, but at least theoretically, most of the Russian empire conformed to the model created by the ministry.

An investigation and comparison of the rules for "public women" reveal how the tsarist administration conceived of its role and the way that it understood prostitutes and prostitution. Though regulation had a simple raison d'être, that of protecting society from likely carriers of venereal disease, taking its cue from Paris it quickly assumed other guises as well. In the regulators' view, women who worked as prostitutes needed not only medical screening, but protection and management. As a "necessary evil," prostitution was considered a receptacle for the male desire that could not be contained within the sexual status quo. Thus, prostitutes were both "victims of social temperament" (as Russians euphemistically referred to them) and "temptresses" who corrupted and ruined young men. Prostitutes were scorned as fallen women, but they were also seen as requiring paternalistic care. Such care was assigned to the medical police in the form of strict monitoring

[25] Derived from "Zakonodatel'noe predpolozhenie," pp. 2072–77; Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," p. 343.

of dress and behavior in addition to physical health. Yet, as the MVD realized its own limitations and how the regulations themselves were inadequate in terms of their original rationale and the epidemiology of venereal diseases, the rules changed.

The minister of internal affairs, Lev Perovskii, conceived of nadzor when the vast majority of Russia's population was still made up of serfs. As a result, the rules that Russia had borrowed from Paris assumed a different aspect, for they were no longer designed for the urban lower classes of a constitutional monarchy, but for an autocratic society divided into legally defined estates. In Paris, the rules limited a woman's freedom; in Russia, they simply placed new constraints among a population accustomed to living in bondage. The MVD made explicit the estate-based nature of regulation in an 1844 administrative circular. "It goes without saying," wrote the ministry, that these measures must apply to "only those individuals who by their way of life, as well as their rank and other communal [obshchezhitel'nye ] circumstances, can be subject to them" (i.e., serfs and the urban lower classes).[26]

The first set of rules, designed for St. Petersburg in 1844, began unequivocally: "A public woman is obliged with all conscientiousness to carry out the rules that have been enacted and shall hereafter be enacted by the committee."[27] Violators risked indeterminate sentences in the workhouse. Medical examinations were to be undergone "unquestioningly" once a week for independent prostitutes (odinochki ) and twice weekly for women in brothels. If a prostitute or her examining physician noticed any signs of venereal disease, she was to report immediately to the hospital. The rules rewarded a prostitute's compliance by promising free treatment to women who reported voluntarily.

When it came to disease prevention and personal hygiene, a prostitute's obligations became vague, of dubious benefit, and impossible to enforce. For example, the rules required her to wash "certain parts" of her body as often as possible with cold water. "After relations with a man," she could not take another client before having washed and, if possible, changed the linen. As for actual baths, though, she need take only two per week. Because physicians believed that blood served as an ideal conduit for infectious diseases, a prostitute was not to practice her trade during menstruation. A spartan note crept into the rules with

[26] Quoted in Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, p. 23.

[27] Rules in Sbornik pravitel'stvennykh rasporiazhenii kasaiushchikhsia mer preduprezhdeniia rasprostraneniia liubostrastnoi bolezni (St. Petersburg, 1887), pp. 49–51. See also Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia," p. 470.

cautionary words against too much makeup and perfume. In the realm of extreme administrative fantasy was a rule asserting that "public women are obliged to examine the reproductive parts and underwear of their visitors in order to protect themselves from infection." Needless to say, the dark, hasty, and often drunken encounters between clients and prostitutes rarely leant themselves to such clinical beginnings.

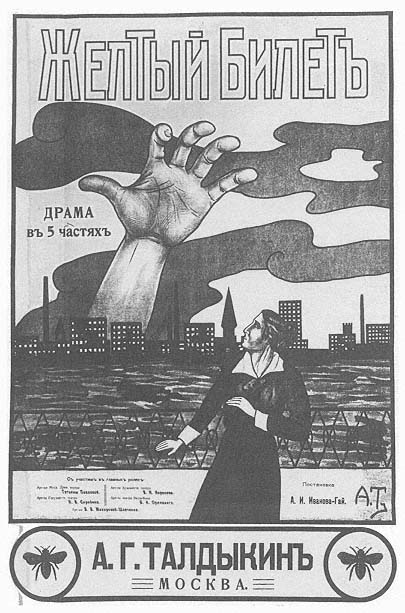

Reflecting the dual nature of regulation as both a police and hygienic measure was a rule that demanded prostitutes carry their "medical ticket" at all times. Commonly known as the "yellow ticket" (zheltyi bilet ), this was a card issued to all registered prostitutes as certification of their trade and a handy medical guarantee for the interested client.[28] In its original form, the medical ticket listed a woman's name, age, and address, and left room for a physician's stamp or mark regarding her state of health.[29] While it appeared innocuous, the yellow ticket in fact created a new social category in tsarist Russia, that of the "public woman." Divided from those women who were practicing prostitution on a casual or clandestine basis, bearers of the yellow ticket were protected from police harassment as much as they were fully subject to police controls. Unlicensed women avoided the obligation to appear for examinations, but they remained vulnerable to arrest during the police raids that periodically swept through the working-class districts of Russia's major cities.

A set of regulations even more exacting than those directed toward prostitutes governed brothelkeeping (soderzhatel'stvo ), a profession limited to women between the ages of 30 and 60 who had no children living with them.[30] Whereas prostitutes had only eleven rules to obey, brothelkeepers were subject to nearly three times as many. These rules combined ministry concerns about order and public health with a new element—evident discomfort over licensing houses of vice. Consequently, a madam (soderzhatel'nitsa ) had to be more than a mere landlady; she had to "restrain" the women in her charge from abusing alcohol, to "demand" that they remain "tidy," to "observe" that they

[28] Yellow tickets appear to have existed even prior to the introduction of regulation. In 1835, an "Imperial command" provided for free treatment at the police ward of Kalinkin Hospital for women with "distinctive yellow tickets." Borovitinov, "Publichnye doma," p. 341; Kapustin, Kalinkinskaia gorodskaia bol'nitsa, p. 13. In 1909, the MVD's Medical Council ruled that yellow tickets should be replaced by white ones that contained photos of their bearers. From "Usilenie nadzora za prostitutsiei," Populiarnyi literaturnomeditsinskii zhurnal doktora Oksa (April 1909): 53.

[29] Sbornik contains a sample copy of the 1844 medical ticket on p. 51.

[30] For the rules pertaining to brothelkeepers, see ibid., pp. 35–39.

followed the regulations about modestly applied makeup and personal hygiene (such as making sure that their underwear was clean). It was also her responsibility to maintain not only "quiet" in the bordello, but an atmosphere of "decency" (blagopristoinost '). Accordingly, brothel doors were to remain shut on Sundays and holy days until after the midday meal, and male minors and students could not be admitted "under any circumstances." As for the "whores" themselves, none of whom could be under 16 and all of whom had to be registered with the police, they were not to be "exhausted" by "excessive use." Nor could they be held in a brothel any longer than they wished. Should a woman wish to quit, any debts she owed the brothelkeeper could not serve as an obstacle.

Rules gave the brothelkeeper medical responsibilities as well. Although the medical-police physician made regular visits, madams were expected to examine the women in their houses on a daily basis and dispatch those with venereal symptoms to the hospital. Monetary incentive was added: women who appeared voluntarily would be treated without charge, while treatment for those whose illness had been discovered by a doctor would be charged to the brothelkeeper. If a prostitute missed an examination, the brothelkeeper herself would be liable to prosecution. The madam upon suspicion of vice had to submit to medical examinations, as did her grown daughters, female relatives, and female servants. Finally, severe penalties could be imposed for aiding a pregnant prostitute in securing an abortion, turning to unlicensed medical practitioners, or using home remedies to treat sick prostitutes.[31] (This proscription no doubt referred to the common practice of brothelkeepers and their associates of dabbling in folk medicine to cure various illnesses, as well as to their custom of terminating unwanted pregnancies.)

The St. Petersburg experiment proved auspicious enough for the MVD to order provincial authorities throughout the empire in 1851 to follow the capital's rules in their home provinces by keeping "full and accurate lists of public women, that is, those women who regard debauchery [rasputstvo ] as a trade."[32] But provisions for the control of venereal disease were broadened here to include the potential male carriers whom regulation had, at first, ignored. Prevention of venereal disease

[31] Statutes 25–32 in ibid., pp. 37–39.

[32] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 13–14; Nikolai Di-Sen'i and Georgii Fon-Vitte, eds., Vrachebno-politseiskii nadzor gorodskoi prostitutsiei (St. Petersburg, 1910), p. 11.

now meant surveillance in the form of general periodic examinations for male factory workers as well as for prostitutes. The examinations of factory workers did not, however, succeed in discovering venereal disease with any great accuracy. A Russian worker described how these examinations proceeded in his Moscow factory prior to Easter and Christmas holidays:

On payday, in the paymaster's office, a doctor would be seated next to the bookkeeper while he paid us. We would line up, undo our pants, and show the doctor the part of our bodies he needed to see. The doctor, after tapping it with a pencil, would tell the bookkeeper the results of his "examination," whereupon the bookkeeper would hand us our pay. Although there were probably quite a few workers at the factory who were infected with venereal disease, I do not know of a single instance when the doctor found such a person during these medical examinations.[33]

Men suffering from venereal disease were also to be interviewed to determine the source of their contagion, with examinations obligatory for those whom they named.[34]

Although empirewide nadzor fell under the aegis of public health protection, it is obvious that regulation and related measures were aimed at the lower classes. The rules betrayed the administration's willingness to stop short of subjecting female workers to invasive medical procedures. Yet, when it came to women identified by diseased males or women about whom "strong doubts" existed as to their state of health, scruples gave way to intervention. The ministry also mandated medical examinations for "all persons of both sexes from the lower class who had been arrested by the police for deeds against public decency [blagochinie ]." Tsarist authorities had granted themselves the prerogative to determine which women exhibited "debauched" behavior and thereby represented a threat to public health. Essentially, the state inscribed society on a grid of class and gender that divided the "good" women from the "bad," and the rich men from the poor.

The MVD approved a new, more explicit set of rules for Petersburg's

[33] Reginald E. Zelnik, trans. and ed., A Radical Worker in Tsarist Russia: The Autobiography of Semen Ivanovich Kanatchikov (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), pp. 51–52.

[34] From A. I. Smirnov, "Ob uchrezhdenii vrachebno-politseiskikh komitetov," Trudy Vysochaishe razreshennago s"ezda, vol. 1, p. 3. When a military commander of troops in Kaluga province ordered examinations for twenty women who had been named as sexual partners of soldiers with venereal infections, only two turned out to have visible signs of venereal disease. Otchet Meditsinskago departamenta Ministerstva vnutrennikh del za 1891 god (St. Petersburg, 1908), p. 177.

medical-police committee just a few months following the emancipation of Russia's serfs in February of 1861. Although most of the revised rules simply reiterated earlier ones, some painstakingly elaborated prior rulings and softened a few others. Police-oriented regulations were now expanded to counter the serfs' newfound freedom, creating a novel dimension for the government regulation of prostitution, the substitution of medical licenses for prostitutes' internal passports. Deprived of the identification required of all Russian subjects, women who registered with the medical-police committees after 1861 had nothing to show prospective landlords or employers but their embarrassing yellow tickets. At the end of the century, critics would charge that this policy doomed thousands of women to treat prostitution as their permanent and irrevocable career, and removed any cloak of anonymity that women who turned to this trade on a casual or clandestine basis may have maintained within their communities.[35] Though only Petersburg's rules specified the confiscation of a prostitute's passport, most cities and districts adopted similar policies.

The new rules also circumscribed prostitutes' movements in ways that the original regulations did not.[36] Now prostitutes had to conduct themselves "as modestly and decently as possible, not displaying themselves from windows in an unseemly state, not touching passers-by on the street, and not calling them over." If they appeared in public, they could not "do anything indecent and were not to walk together in a group." Furthermore, in the name of propriety, public women were forbidden from occupying in box seats in local theaters.[37] To guard against the existence of unlicensed bawdy houses and to make sure that groups of prostitutes remained under a watchful eye, odinochki could not live

[35] This is called the "first terrible instrument of bondage" in Elistratov O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, p. 7. In Prostitution and Victorian Society, Walkowitz argues that the promulgation of regulation in Great Britain accelerated the creation of a professional class of prostitutes. A prostitute who participated in a 1975 prostitutes' strike in Lyons described how she felt when she accepted Morocco's version of a yellow ticket for work in a licensed brothel: "[The police] issued you with a special card with all your particulars and your photo on it. They took away all your papers—your passport, your identity card, absolutely all your papers. That bit was terrible. You felt well and truly . . . BOOKED." A——, "A Woman's One Asset," in Prostitutes—Our Life, ed. Claude Jaget (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1980), p. 61.

[36] For the 1861 rules, see Sbornik, pp. 52–55.

[37] In a more extreme vein, Berlin rules from 1911 prohibited prostitutes from visiting "theatres, circuses, or exhibitions, or the concert gardens connected with them, the Zoological Gardens, the Museums, the railway stations . . ., or, finally, any places that may be named in later orders of the police authorities." Flexner, Prostitution in Europe, p. 416.

more than two to an apartment and could expect periodic home visits from committee doctors and police agents.

From a hygienic point of view, the new rules adhered to the former principles, but with some curious additions, such as recommendations for weekly baths only. No longer were prostitutes obliged to examine their clients' underwear and genitals; this was now a "right," not a requirement. Between clients, a prostitute had to add douching to her routine of cold-water washing. In a more propitious direction, a new statute guaranteed free treatment for all diseased prostitutes. But women who did not enter Kalinkin Hospital within two hours from the time a physician diagnosed them as contagious risked being brought there by police agents.

The final four rules were designed to regulate the relationship between prostitutes and brothelkeepers. Brothelkeepers could not keep more than three-fourths of a prostitute's income and in return they were obligated to provide lodging, light, heat, plentiful and healthy food, sufficient linen, and clothes. If a woman remained in a brothel less than one year, she was compelled to return those items given to her by the brothelkeeper; otherwise, everything remained in her possession. The rules of 1861 for prostitutes also contained a statute reminding them of their right to leave a brothel at any time, specifying that any obstruction by the brothelkeeper constituted a criminal offense.

The new rules for brothelkeeping narrowed the age limit to women between the ages of 35 and 55, and spelled out their obligations with much more detail.[38] Although the early rules had specified how debts could not obstruct a woman's desire to quit her brothel, several of the 1861 regulations addressed this issue more explicitly, suggesting that indebtedness had turned out to be a highly contentious area. For example, 1861 regulations granting brothel prostitutes the right to maintain separate account books for recording their earnings and personal possessions indicate that brothelkeepers had been guilty of keeping their own (dishonest) records. Illiterate prostitutes (the overwhelming majority) were even permitted to request assistance in this endeavor from their friends or from police agents and, as further protection, the police kept their own record of a prostitute's possessions. Every week, a prostitute and her brothelkeeper were supposed to review their accounts and sign them; failure to do so meant that the prostitute did not have to pay anything. Yet, significantly, a prostitute could no longer leave at will: the

[38] In 1844, there were thirty-two statutes for brothelkeepers. In 1861, this number increased to fifty-eight. See Sbornik, pp. 36–49; Baranov V zashchitu, pp. 158–62.

new rules obliged women to pay their debts unless they demonstrated a sincere desire to reform by entering a halfway house for "fallen women."[39]

The 1844 regulations had been silent about a brothelkeeper's past. The medical-police committee, however, now required a police investigation of a prospective madam's background to find out whether she had a criminal record and whether she was prone to drunkenness or "unruly conduct" (k buistvu ). Along the same lines, brothelkeepers were to treat their prostitutes "gently" and refrain from beatings. That the committee believed it necessary to include rules designed to prevent the "oppression" of prostitutes in 1861 suggests that brothelkeepers and their associates had earned reputations of brutality.

On paper, the rules transmuted bawdy house revelries into sterile encounters designed only to satisfy the client's "physiological needs." New regulations carefully setting exact limits on the brothel's location, appearance, and functions signaled the committee's desire to mask brothel activities and render these houses invisible.[40] In the paradoxical formulation of a medical-police inspector at the end of the nineteenth century, "The committee does not regard the brothel as a place for debauchery, but as a place which serves the physiological needs of unmarried men. As a result of this view, it is impossible to tolerate any kind of facilities in these houses which would induce debauchery."[41] Accordingly, brothels could not open onto the street like stores. Brothel windows facing the street had to be kept permanently shut and covered with white muslin curtains during the day, wooden shutters or some heavy, opaque material at night, and most brothels could not be within 320 meters of churches or schools.[42] Rules also advised brothelkeepers to restrain prostitutes from unspecified forms of immodest behavior in theaters and other public places. The same rule applied within the brothel: gambling was prohibited, and brothelkeepers were forbidden from selling

[39] Though there were frequent accusations about collusion between brothelkeepers and local authorities, this rule more likely reflected fears that former brothel prostitutes would continue to engage in prostitution without any official supervision.