Preferred Citation: Accampo, Elinor. Industrialization, Family Life, and Class Relations: Saint Chamond, 1815-1914. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1989 1989. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8f59p261/

| Industrialization, Family Life, And Class RelationsSaint Chamond, 1815–1914Elinor AccampoUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1989 The Regents of the University of California |

To Bob

Preferred Citation: Accampo, Elinor. Industrialization, Family Life, and Class Relations: Saint Chamond, 1815-1914. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1989 1989. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8f59p261/

To Bob

Preface

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, three simultaneous events touched the core of European family life: while the demographic revolution transformed family structure, industrialization changed gender roles and Enlightenment philosophies inspired new ideals of equality, personal freedom, and individualism. The convergence of these three revolutions caused the family to become more nuclear, private, and child-centered as it also shrank in size. Male and female spheres came to be more sharply defined. Emotional functions replaced economic ones.

The study of family history provides a unique opportunity to understand the conjuncture of these major events that shaped modern Europe. The family, after all, is the starting point of any society and rarely remains untouched by social change, whether as a cause or as an effect. But its history poses an overwhelming challenge as well. The private nature of family life has kept it hidden from history, particularly among people who left few or no records of their past. The changes described above most closely fit the European middle classes—the victors of all three revolutions—who left the most ample documentation of their everyday lives. That the lower classes experienced these massive social changes very differently is indisputable. Their fertility and mortality remained high and they continued to have large families; the shift from home-based production to mechanized factory production in most cases left a large portion of the working class disinherited. Benefits of democratic ideals came to them very late, and only after bitter struggles to add to the political meaning of freedom a social one: the basic right to exist.

Whatever their response or fate, the industrial proletariat endured a precarious existence and created new strains on the societies in which it lived. Records of conflict with employers and police and of militant protest that often translated into political

movements provide some of the best evidence of these workers' histories. And yet those records represent only a fraction of all workers and only one facet of their past. The family is a key to understanding the effects that economic, political, and demographic change had on the "inarticulate" as well as on those who protested their condition. The story of how the urban proletariat experienced the upheavals of its age must include a detailed examination of the family.

A basic notion among many historians is that the lower classes followed the lead of those above them, that, for the most part, their families eventually adopted the same structural patterns and basic functions the middle class had evolved. Yet family life among urban workers remains relatively unexplored. This study argues that industrialization weakened the working-class family. Though its impacts may have been temporary and transitional, industrialization set the family on a path of change quite distinct from that of the middle class and helped to create deeper class differences.

A starting point for understanding family life among workers is its demographic structure. A fundamental premise here is that fertility, nuptiality, and mortality provide measures of well-being. All workers left records of their individual vital histories: birth, marriage, death. Much of the analysis in this book is based on the reconstruction of these vital events. Records of these events offer a means to study life among workers who otherwise left little or no documentation about themselves. Because work and family were so interconnected, this study also treats the family as a point of departure for understanding broader aspects of the working-class world such as work organization and class relations.

While this book is a social history, it is my hope that it will also engage readers in other disciplines. Chapters 2 and 4, in particular, rely on demographic methods of analysis and are addressed to demographers as well as historians. It has not been my intention, however, to treat the methodology and problems of measurement for their intrinsic interest. Instead my purpose has been to utilize this methodology in order to gain more insight into working-class life. Indeed, I initially approached demographic measurements rather naively and only learned the hard way that a scholar trained in a single discipline cannot simply appropriate the methods of another. Collecting data, coding, computerizing, and running programs

on it and, most important, analyzing it with any sort of critical judgment required several more years than I had originally anticipated. In addition to being indebted to mentors and colleagues in the historical profession, numerous people with demographic and computer expertise make the list of those to whom I owe gratitude a long one.

I would first like to acknowledge and thank the sources of funding that supported this project: a University of California Travel Grant, a French Government Fellowship, and a Haynes Foundation Fellowship funded research trips to France. The University of Southern California Faculty Innovation and Development Grant provided generous support for computer use and research assistance. A Mabelle McCleod Lewis Fellowship and a German Marshall Fund Fellowship at various points released me from teaching responsibilities so that I could devote full time to writing, and the latter also supported a final research trip.

In the conception of and inspiration for this project, as well as in the discipline to carry it out, I owe a great debt to faculty members at the University of California, Berkeley. Gerald Cavanaugh first sparked and nurtured my interests in French history. Hans Rosenberg, more than any other single individual, introduced me to concepts of social history and imbued me with a sense of self-discipline. Susanna Barrows, Fryar Calhoun, Natalie Z. Davis, Jan de Vries, and Neil Smelser gave me invaluable guidance in conceiving and developing this topic, as well as in researching and writing.

When I began research in France, Michelle Perrot offered suggestions for possible directions my work might take. Throughout my stay, the Centre d'Historie Economique et Sociale at the University of Lyon II offered gracious hospitality. I particularly thank Maurice Garden for including me in his seminars and making computer services available, Alain Bideau and Robert Estier for guidance in family reconstitution and demographic analysis, Jean Lorcin for advice on local archives, and all the participants of the center's Saturday seminars for their intellectual stimulation. I am especially grateful to Claire Auzias for her ideas, support, and friendship.

Achieving my research goals would have been far more difficult without the friendship of Hélène Mouriquand and her three children, Laurent, Pascal, and Béatrice Amieux, who frequently provided

me with lodging and familiarized me with the Lyonnais region. They not only helped me overcome practical difficulties of Alpine proportions but made me a part of their family. Laurent and Pascal helped reproduce many of the illustrations in this book. Similarly, the weeks I spent in Saint Chamond and Saint Etienne would have been lonely indeed without the friendship of Jean-Claude and Marie Bonnet and their family, who shared many meals and much knowledge about the Stéphanois people. Not only did Michelle Zancarini and her husband, Jean-Claude, provide lodging, but Michelle shared her library and archival material and offered many research suggestions.

I would also like to express my appreciation to the staffs of the various archives and libraries where I conducted this research: the Archives Nationales, the Bibliothèque Nationale, and the Musée Social in Paris, the Archives Départementales of the Rhôone, the Hôtel de Ville of Saint Chamond, the Greffe du Tribunal de Grande Instance in the Palais de Justice in Saint Etienne, the Chambre de Commerce in Saint Etienne. Most particularly, I owe thanks to Mlle Viallard and the staff at the Archives Départementales of the Loire in Saint Etienne, where I spent the major portion of my time.

The coding and computing of the family reconstitution data would not have been possible without guidance and help from Gene Hammel, Ruth Deuel, and Madeline Anderson. Naintara Gorwaney and Larry Logue helped integrate new data and gave indispensable demographic expertise. Larry Logue spent many hours helping me refine the computer analysis.

Many friends and colleagues have commented on various parts of my research, most often as responses to papers presented at meetings of the Social Science History Association and other conferences: George Alter, Rachel Fuchs, Michael Haines, Michael Hanagan, James Lehning, David Levine, Leslie Page Moch, Mary Lynn Stewart (who read the entire manuscript), and Louise Tilly have all in some way given me critical insights. I am particularly grateful to Don Reid, whom I met when I started this project and who has read various parts and entire versions throughout its development. Friendship and critical advice from Kristen Neuschel helped me through some of the most difficult stages of writing. I also appreciate the advice and encouragement given by Lois Banner, Rudy Koshar, and Lloyd Moote.

To several people I owe an especially large debt. Lynn Dumenil and Steven Ross each gave this manuscript detailed and critical readings in its later stages, and while the shortcomings that remain are of course my own, its final form owes much to their respective insights and suggestions. David Weir contributed to this book by opening a fundamentally resistant mind to the broader possibilities and analytical demands of quantification. He spent several patient hours teaching me some of the intricacies of demographic analysis and suggesting ways in which I could refine my statistics and their interpretations. John Merriman became a mentor and friend at the inception of this project, has offered advice and support through every stage, and has read every version of the manuscript. Few people would debark from the train passing through Saint Chamond, as he did, to see the city about which he had read so many chapters. His archival and cultural (including gastronomic) knowledge of France has enriched my own education beyond measure and has become an inherent part of this book.

Yves Lequin, who also became a mentor and friend when I began this project, helped me in countless tangible and intangible ways; to him I owe the most. It was he who suggested that I study Saint Chamond and use the method of family reconstitution. He provided unstinting support and guidance by introducing me to archives and to other scholars, by making facilities available at the University of Lyon II, and by supplying a coding system for birthplaces and occupations in marriage records. He too gave each metamorphosis of the manuscript a careful reading.

To my husband, Robert Hern, I am also indebted. In addition to his patience, his humor, his insights about working-class family life, and the boundless moral support he gave me while I was writing this study, during the final stage of research he sacrificed a vacation to help track down names in census reports and vital records. As he gave the entire manuscript a mercilessly critical reading, he will appreciate that my gratitude can find no appropriate words. To him I dedicate this book.

Map 1. Department of the Loire

Introduction

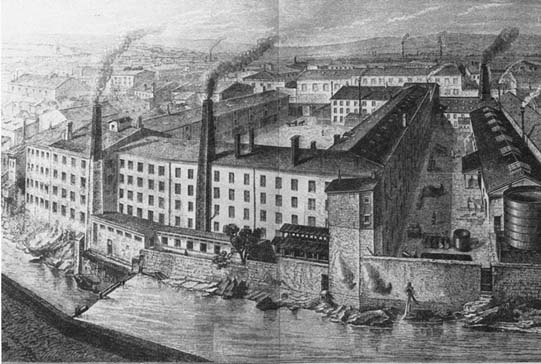

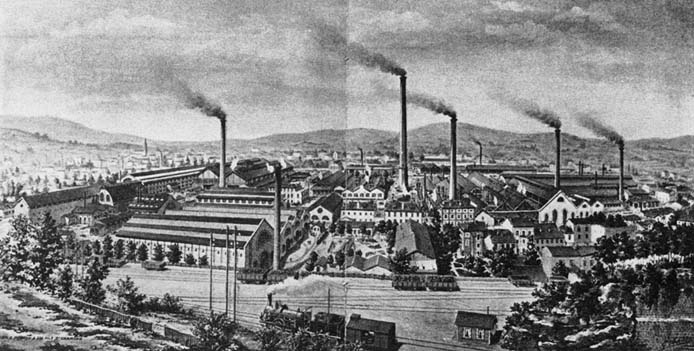

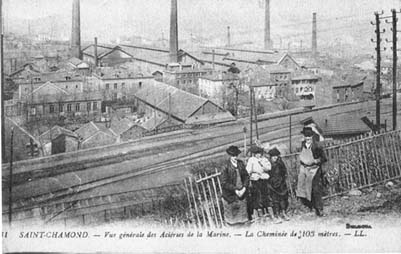

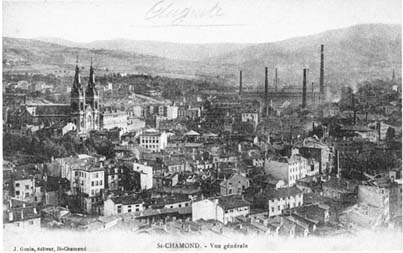

A traveler taking autoroute A-47 southwest from Lyon will first pass by the industrial city of Givors and then descend into the Gier valley. The traffic passes speedily by a cluster of somber little industrial towns that darken an otherwise verdant and pleasant valley: Rive-de-Gier, La Grande Croix, L'Horme. After L'Horme, one comes upon Saint Chamond, the least forgettable of these towns, for there the road goes through, instead of by, the city. A signal, which seems always to be red, halts traffic. The tall smokestacks, darkened old factories, and old houses that retain traces of black smoke impress themselves upon the traveler's consciousness. The green light permits the traveler to continue on to Saint Etienne, a larger version of these industrial towns, but dotted with recently cleaned public buildings and renovated town squares that burst with fountains.

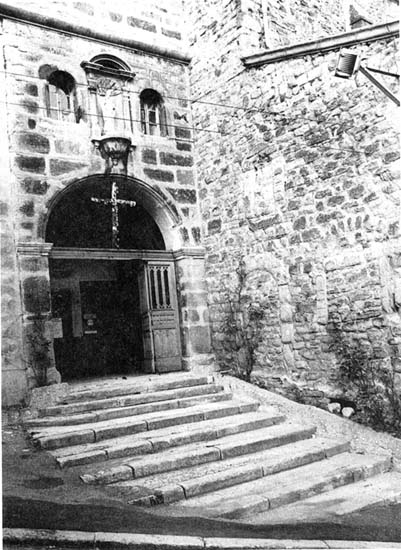

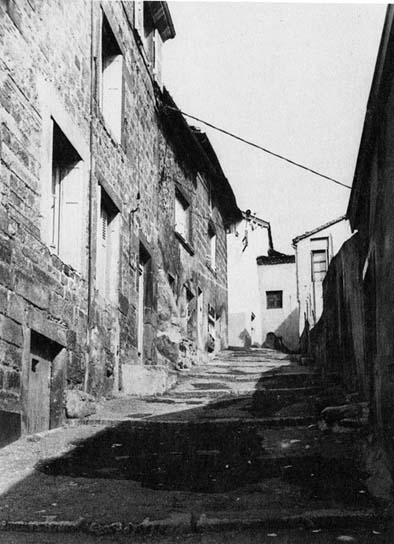

Few tourists would feel inspired to explore Saint Chamond. But a narrow street that goes off to the right leads the venturesome up a steep hill into a neighborhood whose origins date back to the year 640. This hill certainly lacks the charm of Lyon's vieille ville or Croix Rousse. Its past, however, contains a comparable richness. Originally the home of Archbishop Ennemond who came from Lyon, this hill hosted numerous seigneurial lords and religious orders.[1] But apart from street names—rue du Château, rue des Capucins—and the ruins of the chapel of Saint John the Baptist, little of that past remains. Instead one finds the small, unsightly church of Saint Ennemond (see figure 1) and an architecture that speaks to an industrial rather than a religious past.

From at least the sixteenth century, this hill teemed with iron forgers, ribbon weavers, silk workers, and, later, miners, stonecutters, and carpenters. At its base, clustered along the Gier River (currently paved over), millers worked their silk on water-run spindles. The neighborhood of Saint Ennemond today appears much as it did in the middle of the nineteenth century. As one

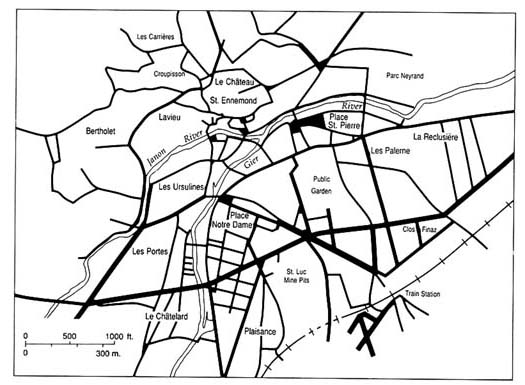

Map 2. Saint Chamond, 1890

military officer described it in 1843, "the houses are of simple construction, built with cut stone." The streets are "generally dirty and poorly paved in round stone."[2] Now blotted with timeworn layers of asphalt, the cobblestone streets twist among old apartments that once housed enormous ribbon looms and shops for iron forges (see figure 2).

The houses designed for tools of production as much as for people testify to a past that knew little distinction between work life and home life. They remind us that one of the most common elements in preindustrial work was its heavy reliance on families rather than factories as work units. From the top of the hill in Saint Ennemond, one can look down upon the lower city, on the other side of the autoroute, where in the nineteenth century industries built their own shrines—braid factories, steel plants, and the immense churches of Notre Dame and Saint Pierre, renovated with bourgeois funds in the 1870s. Today, urban, working-class apartments—tall, gray HLMs (Habitations à Loyer Modéré) built since World War II—dominate the landscape.

Saint Chamond's architecture alone hints at the multiple layers of its history. The differences between the hill and the lower city represent the transformation in workers' lives that came with industrialization. Indeed, the drama that unfolded within these structures during the nineteenth century repeated itself countless times throughout industrializing Europe: productive labor left the home and became concentrated in factories.

When production took place within the home, work and family fused in a number of ways. Labor shared time and space with eating, sleeping, lovemaking, childbearing and childrearing, and socializing with friends and kin. Family and household concerns frequently and spontaneously broke up the sixteen-hour workday. Equally important, the bond between work and family had cultural significance. Men, women, and children often labored as a team. Parents passed skills on to their children, trained and disciplined them, and initiated them into the secrets and associations of their trades. Marriages formed around work relationships and in turn reinforced those relationships. Even when the family members labored at unrelated tasks, the common effort to sustain a family income bound them together.[3]

In removing work from the home and centralizing it near sources of power, mechanization transformed the interrelationship

between family and labor. Merchants no longer put out work to cottagers; instead, the latter had to leave their homes to earn a daily wage. Frequently they had to abandon their homes in the countryside and migrate to the towns and cities where production became concentrated. Not only did such migration often break up families, but factory labor itself changed the relationship between parents and children. Mechanization made some skills obsolete and created other new skills. Training no longer took place in the home and, for the most part, sons no longer learned from their fathers. Factory work also transformed the economic role of women. Because leaving the home to work conflicted with child care, mothers could no longer easily contribute to the family income.

The object of this book is to examine precisely what this dramatic change in the relationship between work and family meant for the lives of nineteenth-century workers. Specifically, it uses family formation and family structure as windows onto the world of workers and as points of departure for understanding workers' material experiences with industrialization and changes in the organization of work. How workers adapted to industrial change in turn cannot be understood apart from their relations with employers and the local elite, whose behavior—benevolent, utilitarian, or a combination of both—created the context in which workers' consciousness developed. Thus a secondary focus of this study is an analysis of class relations in the light of changes in family structure. Industrial change pressed workers into new modes of survival. It also forced the elite to develop new strategies to preserve and discipline the working class and to try to mold workers in their own image.

The city of Saint Chamond and its surrounding region offer rich opportunities to examine the relationship between family structure and economic and technological transformations, as well as implications family change had for class relations. The city is located in the Stéphanois basin, an area which corresponds roughly with the arrondissement of Saint Etienne in the department of the Loire. Referred to frequently as "the cradle of the industrial revolution in France," this basin has long attracted scholarly attention.[4] Its mountains and valleys provided industry with abundant primary resources—particularly in water power and coal deposits—and set the stage for industrialization along classical lines. The region attracted

industry not just because of its resources but also because agriculture alone could no longer support the growing population.[5]

Cottage industry, and especially the employment it provided for women and children, thus contributed significantly to the sustenance of the rural population. An extensive network of domestic workshops produced nails, bolts, files, luxury arms, glass, ceramics, silk ribbon, and thread. By 1790, these industries supported a population of 118,981 in the Stéphanois region. Beginning about 1820, the importation of English metal-working processes, combined with the introduction of steam power, radically transformed this region's economy, demography, and social relations. By 1866, the Loire ranked as one of the most densely populated departments in France.[6] Most of this population crowded into the principal Stéphanois cities of Saint Etienne, Firminy, Le Chambon-Feugerolles, Saint Chamond, and Rive-de-Gier. Stéphanois industrialization also forged a militant working class and an entrepreneurial bourgeoisie committed to republicanism. This workshop of France has become a laboratory for historians interested in studying the economic, social, and political impacts of industrialization.

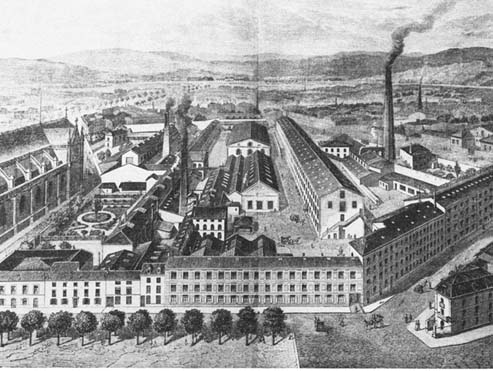

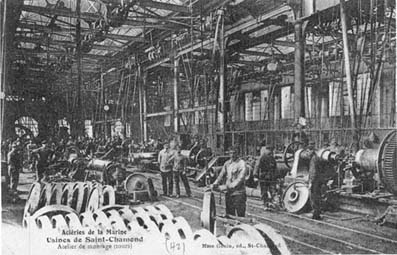

Saint Chamond's development pivoted on the commercial manufacturing of iron and silk. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ribbon merchants and forge masters expanded the domestic industries of ribbon weaving and nail making throughout Saint Chamond and deep into the adjacent countryside. In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, heavy metallurgical production and mechanical braid-making became established. By the 1850s, for a number of reasons that varied from industry to industry, ribbon and nail merchants either left Saint Chamond entirely or invested their capital in the new factory-based industries. The simultaneous mechanization of silk and iron production industrialized Saint Chamond more completely and dramatically than its neighbors. This development in turn transformed the town's labor force, environment, and architecture. Industrialization largely eliminated domestic production, polluted the environment, and drew thousands of migrants from the surrounding countryside. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the town's population grew from 4,000 to 14,000 inhabitants.

Saint Chamond's transition from artisan-based production to full-scale factory production and the pattern of migration and urban

growth there make it an ideal setting for the study of family change among workers. Its combination of metallurgy and textiles makes possible a comparison among different types of artisans and industrial workers; previous social, economic, and political histories of the region, moreover, offer an implicit comparative perspective with other towns and cities.

This book argues that among both artisans and industrial workers a strong relationship existed between the organization of labor and gender roles, the number of children born to workers, and the number of their children who died early in life. Among artisans, family structure depended upon gender-specific demands of labor and varied by occupation. Occupational differences became less important with industrialization. By removing work from the home, mechanization forced workers to restructure their family lives. They had smaller families for both voluntary and involuntary reasons. Most couples clearly attempted to limit the number of their children more than they had in the past, but many had smaller families also as a result of poor health and infant and child deaths.

As workers lost control over their work lives, curtailing family size became more important as a means of exercising self-determination. But many working-class families did not succeed in surviving independently and had to rely on material assistance. In this regard, industrialization meant new forms of dependence on the employer class. Removal of work from the home not only made material independence more difficult but undermined workers' power in other ways. Factory work deprived them of the ability to develop skills and authority within their own families. Apprenticeship either disappeared entirely or came under factory control. Factory work attracted to the city migrants who also suffered a loss of independence from employers because they lacked strong familial bonds and social ties.

This study of industrialization and the working-class family fits into a broad body of literature that spans a century and a half, and its conclusions will clash with those of many studies that have preceded it. Little dispute is engendered by the statement that the removal of work from the home had significance for workers' lives; what that significance was, however, escapes consensus. Throughout the nineteenth century, many observers sharply criticized factory labor. As early as the 1830s, sociomedical economists such as

Louis René Villermé brought attention to the miserable, insalubrious conditions in factories.[7] Later in the century, when working conditions had improved somewhat, political economists still had reason for concern. The concentration of workers into industrial urban slums made them more visible. Crime and poverty made it apparent that workers' home lives had become a source of moral degeneracy. Consternation over working-class morality grew more intense with every social upheaval in which they participated: the revolution of 1830, pervasive working-class unrest shortly thereafter, the revolution of 1848, the increased incidence of strikes in the 1860s, and most important, the Paris commune of 1871. This last event presented the specter of socialism in its most pronounced form yet.

In response to the apparent moral decay in French society, by the 1870s Frédéric Le Play had begun to formulate a sociology of the working-class family. With a methodology based on observation and induction, he concluded that partible inheritance, legislated during the Revolution of 1789, had proletarianized rural workers and devastated their families. It destroyed the traditional stem family, in which the father perpetuated his authority by transferring family property to only one heir, who would provide a pension for his parents and cash or dowries for his siblings. Equal inheritance weakened paternal authority and destroyed the family as a moral and economic unit. Large-scale industrialization accelerated this destruction, particularly for the working classes, for it further destabilized family life.[8]

Le Play inspired many followers who adopted his methodology as well as his conclusions. Among them was the abbé Cetty, who in 1883 published La famille ouvrière en Alsace . Based on interviews with workers in the industrial centers of Alsace, this study attempted to uncover the roots of working-class misery. Although Cetty's perceptions are often skewed by his own moralistic predisposition, his thorough investigation leaves rich material for historians of the working class. Following Le Play's reasoning, Cetty believed that lack of patrimony and the removal of work from the home destroyed the power and authority of fathers over their sons. In former times, the worker's children "grew up under his eyes, were raised by his side, and when they came of age, he made them a part of his work, took them by the hand, and guided their first efforts." But with the introduction of factory labor, young boys associated

talent, art, and progress only with the machine and not with their fathers' experience.[9] Factory organization encouraged insubordination toward the father, for the son did not work under his direction. Working for the same employer placed father and son in a position of equality and sometimes even put the latter in a superior position.[10]

Cetty also attributed the "almost irredeemable decadence" of the family to the unhappy fate that industrialization had imposed on women. He pointed to the central question of the family wage: women had almost no choice but to enter the factory. Prostitution offered the only other alternative. Their departure from the home to the factory attacked domestic life at its very source. And removal of productive labor itself disorganized the family and reduced the home to a mere shelter for eating and sleeping: "[The family] is no longer a hearth around which a new generation grows and develops with the same faith, the same soul, the same character." Parents and children returned from the factories too exhausted for conversation or education. The family lost its role as a source of moral authority and knowledge.[11]

The decline in parental, particularly paternal, authority created a vicious cycle in each generation that weakened the structure of the family. It led to early marriages and numerous children, which in turn resulted in high rates of infant mortality and death from childbirth. Women worked in factories until they delivered babies and then immediately resumed work. Between 1861 and 1870, Mulhouse averaged 33 infant deaths per 100 legitimate births. Worse than early marriages was the habit of concubinage (cohabitation) when workers could not afford to marry. Cetty found the practice reproachable in and of itself, and he showed it also helped produce higher rates of infant mortality: 45 of every 100 illegitimate babies died before they were a year old.[12]

The decline of paternal authority, the necessity for women to work outside the home, the destruction of family traditions, and premature marriages made the family unable to meet its own needs. The death of either parent, which frequently came early, would throw the family into a state of dependence. Other relatives no longer cared for family members as they had in the past. Institutions thus developed to meet those needs. Orphanages, kindergartens (salles d'asile ), and hospices had become establishments of "first necessity"; in Mulhouse, the salles d'asile "render such great

services, that have so entered the customs of the inhabitants, that it would be hard to imagine this city without them."[13] Although Cetty praised charitable activities in the industrial centers of Alsace, he did not look to charity as a solution to the problems of the working-class family. Instead, the family had to be strengthened from within. He cited efforts among some industrialists to reinforce morals both in and outside the workplace.[14]

Cetty and Le Play condemned industrialization because it ruined the family and thus undermined the moral basis of society. Noteworthy about their position is that they did not blame the worker for moral degeneration. Instead, the family had become the "first victim of industrialism," whose situation required the invention of a new word, pauperism .[15]

Not all contemporary observers shared the views of the Le Play school. The well-known inquiries of Louis Reybaud and Armand Audiganne, for example, did not consider the removal of work and of women from the home as destructive to the family. The fact that women had always performed productive labor made their entry into the workshops and factories seem logical. Indeed, many investigators believed factory work to be beneficial to women because machine-tending suited their strength. They did not, moreover, view factory work as a source of family decay. Employers and observers alike frequently indicated that unmarried women supplied most of the labor force; they left the factory either after marrying or after the birth of their first child. Unlike Cetty, Reybaud and Audiganne believed the miserable slums they witnessed in their travels resulted, not from industrial capitalism leading systematically to pauperism, but from individual moral failings.[16]

The most recent generation of scholarship echoes these latter observers insofar as it has treated the working class as maker of its own history rather than as passive victim of the industrial process. E. P. Thompson pioneered new avenues of research by bringing to light the existence of a positive, rich working-class culture that enjoyed independence.[17] Labor movement activity grew out of that culture. As social history came to focus on working-class life rather than on labor movements and strike activities alone, the working-class family emerged as an important source of culture.

Recent research tends to support the view that industrialization did not severely disrupt family life among workers, and certainly that it did not destroy it in the ways Cetty and others suggested.

Examples abound. Nearly thirty years ago, Neil Smelser noted that mechanization in the English cotton industry did not break up the family; parents employed their own children in factories and thus replicated some of the teamwork they had depended upon in their homes. Michael Anderson later demonstrated that, if anything, migration and industrialization strengthened relations among family and kin. Migrants from the countryside did not travel alone to the city. They came with, or after, family, friends, and neighbors. Hardship forced them to rely on one another even more than before. During critical life situations—unemployment, sickness, the death of a key wage-earner in the family, widowhood—workers relied on one another and used bureaucratic forms of assistance only as a last resort. In his more recent study of the Lyonnais region, Yves Lequin also stressed continuity in the industrial process: industry moved to the countryside long before workers moved to urban industry. When they did migrate to the city, many came from only a day's journey away, and they maintained contact with the countryside. Moreover, they came from regions that already had the same industries as those in the city. In other words, occupational and thus cultural continuity mediated the move from country to city.[18]

Lequin's conclusions complement another direction of research that further turns attention away from industrialization per se as the most important watershed in the history of the working class. Wage labor in the context of cottage industry proletarianized workers and transformed their family lives long before mechanization did. Artisans became proletarianized because they lost control over the purchase of raw materials, tools of production, and the marketing of finished products. This process, recently labeled proto-industrialization , prepared workers for urban factories and was a phase not only preceding industrialization but necessary to it.[19]

The focus on proto-industrialization has brought to the surface the darker side of domestic industry. In addition to proletarianizing workers, it also reshaped the working-class family by encouraging workers to have large numbers of children so that they could contribute wages to the family income.[20] It could and did lead to the exploitation of men, women, and children. In the light of recent research, the Le Play school's nostalgia for domestic industry looks extremely romantic. Not only did the working-class family survive

factory labor intact, but the mode of production preceding it offered a far from ideal situation for the traditional family as they conceived it.

In their path-breaking study of industrialization and women's work, Joan Scott and Louise Tilly also downplay the severity of change that mechanization brought to the family. They conclude that the family provided "a certain continuity in the midst of economic change" in the contexts of domestic and of factory production. Even though industrialization removed work from the home, the spheres of family and work did not separate completely; the family "continued to influence the productive activities of its members."[21] Most important, they called attention to the crucial relationship between production and reproduction. In the transition from the family economy to the family wage economy and family consumer economy, workers adjusted their fertility strategies. According to this scholarship, the family turned out to be remarkably flexible in the face of industrial change.

The studies of these researchers and others investigating the family economy have demonstrated that although most production ultimately did leave the home, the process occurred gradually. New types of domestic industry replaced those that became mechanized. The introduction of electricity began another era of home industry, much as did the personal computer in recent years. Married women and mothers, by continuing to work in the home, carried on the same kind of productive activities they always had. Home industry permitted them to continue to juggle productive and reproductive responsibilities.[22]

Implicitly and explicitly, this scholarship suggests that the family served not only as a source of continuity but, indeed, a source of strength, if not defense. Echoing Michael Anderson's findings, Jane Humphries has offered the hypothesis that family hardship promoted a "primitive communism" among workers that, in turn, helped promote class consciousness. In the effort to avoid the "degradation of the workhouse," only kinship ties could "provide an adequate guarantee of assistance in crisis situations." Not only were kin ties strengthened, but the struggle to provide for nonlaboring members of the family created a consciousness of social obligation that extended to nonkin. This sense of obligation in turn established a basis for class consciousness and class

struggle. The family's ability to survive independently of state institutions provided a foundation for class resistance to economic exploitation.[23]

The existence of a powerful labor movement by the end of the nineteenth century demonstrates that industrialization did not destroy the moral fabric of the working class. Workers could not have organized if factory labor had reduced their family lives to total disarray. Complete demoralization would have resulted in apathy. On the contrary, a positive culture gave workers the class consciousness, inspiration, and courage to resist exploitation and demand more rights in the workplace. William Reddy, for example, has recently documented that protest often derived from the effort to protect not just the family income but a way of life organized around it.[24]

The recent empirical research seems to overturn the assessments of working-class life that are based on eyewitness accounts of the Le Play school. This study of workers in Saint Chamond, however, argues that while the modern research corrects the Le Play school it goes too far in downplaying the extent and profundity of change that occurred in family life. It has also left unexplored the implications those changes had for class relations. The argument presented here turns to an analysis of demographic patterns as a key to understanding economic change and working-class family life. A close examination of marriages, births, and deaths among proto-industrial and industrial workers reveals that an enormous change in the family did occur with industrialization: through deliberate control over births as well as through high mortality, family size declined; the working-class family also became weakened as a basis for class culture as it lost a certain measure of autonomy.

Nineteenth-century observers and modern historians have noted that industrialization caused a lowering of the age at marriage, reduced life expectancy, and increased infant and maternal mortality. But at the same time, in part because of earlier marriages, it also caused a larger than average family size among workers. While workers supposedly continued to have large families, contraceptive practices spread regionally and conquered all of geographical France. Thus in the face of this overall decline, the newest of social classes, that of urban industrial workers, apparently remained a bastion of high fertility. While considered "laggers" in the general demographic transition of Western society, they eventually joined

the middle class in having smaller families once infant mortality decreased and their standard of living rose.[25]

Analyses of family structure among industrial workers have been based mostly on aggregate data from vital events or from census reports, neither of which can provide a completely accurate picture of fertility or trends in fertility. Aggregate data, for example, cannot control for such factors as duration of marriage; census reports supply information for households rather than for families and do so only at five-year intervals. A more accurate method for documenting fertility change in a local context is through family reconstitution—the actual reconstruction of individual families through linkage of birth, death, and marriage records over two or more generations for the entire population of a single locality. Most family reconstitution studies have concentrated on preindustrial populations, in part because they seek to establish the roots of the fertility transition, which began prior to industrialization. Moreover, in practical terms, the task of family reconstitution is an overwhelming one even for small village populations. Few family reconstitutions have been conducted in an urban context, and none has been done, to my knowledge, for a nineteenth-century industrial city.[26] Yet without this technique, gaining a detailed picture of fertility and mortality among urban workers and thus better insights into the material conditions of their family lives remains beyond the historian's grasp. Through a method of cohort analysis, I have overcome most of the obstacles inherent in reconstituting families in an urban population.[27]

Using family reconstitution, Part 1 of this book explores the relationship between work and family in two contexts: among proto-industrial artisans in the first half of the nineteenth century, and among factory workers in the second. Although workers did continue to have relatively larger families, family size declined considerably with industrialization. More important than the decline itself are the conditions under which it took place: workers had fewer children not because they began to follow the path of their middle-class counterparts, but because the industrial work organization pressed them into doing so. The decline in fertility neither stemmed from an improved standard of living, as is often argued, nor did it necessarily lead to a higher standard of living. Instead, fertility and mortality signified distress among certain elements of the industrial population.

Part 1 also explores the meaning that change in work organization had for the family by reexamining and questioning the continuity between rural and factory industries, as well as occupational continuity between generations. Registers of births, deaths, and marriages used for family reconstitution contain detailed information about occupation, birthplace, and residence. The linkage of these records in the individual family histories over two or three generations in Saint Chamond thus makes possible a close examination of migration and occupational change. Despite the proletarianization prior to mechanization, and the continuity it provided for urban industry, migration and new modes of production indeed produced a generational break with the past. Occupational inheritance did decline, and where it persisted it created fewer and less meaningful bonds among family members. Migration also broke up families even when it strengthened ties among those members who stayed together.

This study of occupational change and family structure also touches on the question of whether patriarchal authority within the family deteriorated, leaving family life more permeable to employers' paternalistic incursions. Removal of work from the home meant a decline in occupational inheritance as well as a loss of family cohesion. This process portends a loss of social power as well as of authority over the work process itself. When skills and their perpetuation remained in the domain of the family rather than of the capitalist, workers had leverage over who attained skills. The decline in occupational inheritance and the fact that its very nature changed clearly transformed the relationship between parents and children, because parents lost much of their ability to shape a child's future, and children had to leave the family to obtain skills. The family lost custody over technological knowledge. This process also changed the relationship between employers and workers, for the former began to control apprenticeships.[28]

A third area of investigation in this book is class relations, to which Part 2 is devoted. This subject has certainly received more than its share of attention from historians. And yet scholars have focused mostly on workers who exerted power. They have not often enough questioned why the majority of workers did not organize and why those who did failed in their efforts to construct a society according to their own vision. This study examines class relations in a society where workers did not exercise very much

power and seeks to explain why this was the case despite their efforts to organize. One area of investigation is the practice of paternalism, a topic that has received increased attention in recent years. Paternalism has generally been examined in the context of workers who rejected it, which has led to the conclusion that it did not succeed in its goal of pacifying the working class. Many workers did indeed shun material assistance. Others, however, had no choice but to rely on it. Whether or not it achieved its goal, material assistance did play a role in class relations that has, as of yet, remained relatively unexplored.

The use of paternalism to describe various forms of charity in the late nineteenth century has confused the issue because the word connotes an anachronistic, Old Regime view of the world and thus one whose policies were doomed to failure in the nineteenth century. The analysis of charity in Saint Chamond is based primarily on the archives of the city's hospice—a source rarely used in studies of the working class—as well as on employer practices within and outside the workplace. These sources show that industrialists in Saint Chamond tailored their paternalistic activities to conditions of urban industrialization. They adopted new ways of administering material assistance such as employer-controlled insurance and child-care centers. These institutions not only addressed the new pressures that came with industrial society but also attempted to moralize workers. Rather than restoring power and authority to the working-class family, these paternalistic practices assumed some family functions and further deprived workers of independence. What happened in Saint Chamond at least partially supports recent theories regarding industrial discipline derived from Michel Foucault and Jacques Donzelot and applied by Michelle Perrot.[29] The inability to survive independently made many working-class families permeable to intervention from local caretaking institutions. The family became a medium for class relations and an arena for elite influence.

Part 2 also examines local politics and the labor movement in this context. Here previous work done on the Stéphanois region provides a comparative perspective. Yves Lequin, Sanford Elwitt, Michael Hanagan, and David Gordon have analyzed working-class and middle-class left-wing political activity in this region during the nineteenth century.[30] In both its bourgeois and its working-class political consciousness, Saint Chamond proved exceptional

for this region and provides interesting points of contrast. Its bourgeoisie remained devoutly Catholic and politically conservative, if not monarchist, through the end of the nineteenth century, while the working class was relatively tranquil. This book argues that rapid industrialization, the need to rely on material aid, and the Catholic, monarchist, and paternalist stance of employers weakened workers' propensity to develop a strong political movement; moreover, because local priests were friends of the poor, workers could not fully sympathize with the anticlericalism of the left wing. At the same time, workers did retain a cultural independence and many of them resisted elite domination even though it did not become effectively translated into political opposition. Their resistance is all the more remarkable given the cultural barriers to the formation of worker associations and the pervasiveness of employer efforts at political hegemony.

Every city or region is unique. The hope of a local study is to speak, not to that uniqueness, but to common human experience. In Saint Chamond, the years between 1860 and 1880 mark a period of discontinuity in working-class culture and family formation strategies. These workers' experience does not fit easily with the thrust of recent scholarship. But perceptions of continuity and discontinuity do not necessarily contradict one another. Instead, they represent coexisting realities. Neither proto-industrialization nor industrialization assumed homogeneous forms in their respective developments. Nowhere did industrial capitalism develop linearly. Thus the impacts of industrialization on the working-class family varied as well. In Saint Chamond, mortality and fertility rates suggest that industrialization caused distress for the working-class family. Rarely are demographic patterns unique to a single locality, and Saint Chamond was not alone in its high rates of death and low rates of birth. Nor was it unique in its strong paternalism. In the structural weakening of the family and its vulnerability to assistance from the elite, the experience of the Saint-Chamonais should provide insight into workers' lives in other industrial centers.

PART 1

WORK AND FAMILY STRUCTURE

1

Labor and Family among Artisan Workers, 1815–1840

In 1807, Jean-François Richard-Chambovet, a prominent ribbon merchant in Saint Chamond, traveled to Paris, a journey few Saint-Chamonais of the nineteenth century ever made. He certainly had the leisure to travel during this year, for revolution and war had nearly decimated his business. While wandering about Paris trying to distract himself from commercial troubles, Richard-Chambovet came upon a shop of antiques and used goods. There a curiosity caught his eye: a loom with thirteen spindles. How strange this mechanism appeared to him, for it was completely unlike the ribbon looms with which he had great familiarity. The shop had three of these looms; Richard-Chambovet purchased them all, for the hefty sum of 390 francs apiece, and brought them back to Saint Chamond.[1]

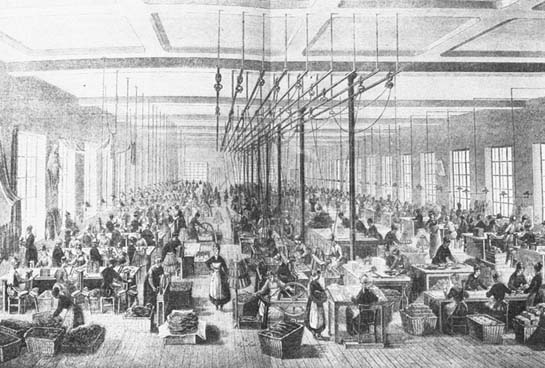

Little did this ribbon merchant know that his simple purchase would eventually reshape the economy of his native town and, indeed, change the direction of its history. These looms braided threads rather than weaving them. Their arrival coincided with the introduction of steam power. Much less delicate than ribbon looms, braid mechanisms adapted well to steam. By 1820, Richard-Chambovet had a factory with 298 braid looms. A decade later, steam powered 4,000 spindles in Saint Chamond, and by 1860 this number had multiplied by no less than one hundred. Mechanically produced braids did not replace the shinier and more delicate woven ribbons. Indeed, the Restoration brought a return to fancier tastes, and the ribbon industry experienced a golden age between 1815 and 1825. But by the 1840s factory-produced braids replaced ribbons as the primary textile industry of Saint Chamond.[2]

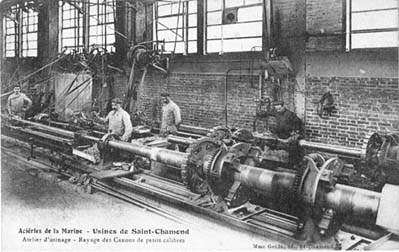

The Saint Chamond economy simultaneously expanded in the metallurgical sector. The extensive coal deposits of the Stéphanois region attracted entrepreneurs who introduced blast furnaces and

rolling mills in the 1820s and 1830s. They built English forges in Saint Chamond and the surrounding communes of Terrenoire, Lorette, Izieux, Saint-Julien-en-Jarrez, and Saint-Paul-en-Jarrez. By 1831, large-scale industry in two sectors vital to the French economy, textiles and metal, had been installed in Saint Chamond. Meanwhile, the two traditional craft industries that had established Saint Chamond as a commercial town, nail making and ribbon weaving, had all but disappeared by 1850.[3]

During the first half of the nineteenth century the basis of the Saint Chamond economy thus became transformed from domestic production to large-scale factory production. Capital and labor were transferred from craft to mechanized industries. In this complex process, the choices, activities, and capital of Saint Chamond's merchants and entrepreneurs played a decisive role. The transfer of labor, however, required a distinctly human shift and thus entailed the decisions, choices, and will of workers in Saint Chamond as well. Industrialists certainly felt pleased with this town's technological transformation; but how did workers experience it?

In some other parts of France where industrial capitalism similarly transformed industries and local economies, artisans resisted change and retarded its effects by maintaining control over their own labor. Although the Le Chapelier Law of 1791 was intended to abolish guilds and other worker associations, many persisted. Craft guilds, confraternities, compagnonnages , and other quasi-religious associations helped artisans extend their work identity to a sense of fellowship with other members of their trade. Associations enabled them to maintain some control over their work by regulating entry into the craft through apprenticeships and by regulating standards of production.[4]

In other cases, however, economic development alone undermined the power of worker associations to preserve their way of life. In Saint Chamond, for example, merchants controlled raw materials, imposed standards of work, and monopolized the sale of finished products. Confréries persisted throughout the nineteenth century, but they came to be dominated by employers and confined themselves primarily to religious functions.[5] As associations weakened, the family assumed more significance as a repository for culture centered around work, and particularly as a main source for apprenticeships. Consciously or not, it developed into the primary

theater in which tactics for preserving a way of life became formulated; equally, it became the arena in which workers relinquished their way of life. How they responded to economic change in large part depended on the degree to which the family operated as a production unit and on the extent of their success in passing skills on to new generations.

While during the course of the nineteenth century industrialization reshaped family life, what happened within the family also largely determined the fate of domestic industries. In Saint Chamond, the majority of men and women devoted themselves to some stage in the production of nails, ribbons, and the processing of silk. Most work took place in the home, and in both silk processing and iron working, parents passed skills on to their children. Each craft, however, responded to economic change in Saint Chamond very differently. Despite a decline in the ribbon industry, weavers clung to their trade and persisted in passing it on to their children. Nail makers and their sons more readily abandoned their craft.

One reason for the divergent patterns in these responses stems from the nature of the work itself. In the end products as well as in the labor that created them, these two crafts could not have differed more. Ribbon weavers turned organic material into beautiful luxury items that had little utilitarian purpose beyond the satisfaction of consumer vanity. Their value was subject to the whims of constantly changing fashion. At the same time, their production required lengthy apprenticeship, highly developed skills, dexterity, patience, and, for the best ribbons, a true artistic talent. Nail makers turned inorganic material into an exclusively utilitarian object with little aesthetic value. Only seasoned nail makers appreciated aesthetic qualities in details of difference among the thousand or so varieties. Their indispensability insured more consistent employment. The creation of nails, however, required more practice than training, more brute force than talent.

Ribbon weavers indeed felt more pride in their work, which partly explains their greater attachment to it. But this attachment did not stem from the nature of the work alone. The relationship between family and work among both nail makers and ribbon weavers provides insight into cultural approaches that informed their behavior. A key difference between the two crafts helps to

explain their divergent responses to economic change: though both industries took place in the home, ribbon weaving depended upon the family as a unit, while nail making relied primarily on adult male labor. To survive in the face of technological change and loss of control over various stages of production, ribbon weavers drew more heavily on the productive capacities of their wives and children. Nail makers, on the other hand, turned outward from the family and tended to seek opportunities that were less domestically oriented.

From the preparation of raw materials to the marketing of the final product, ribbon production had a complex organization, of which weaving constituted but one stage. It was this stage, however, that involved the family most completely as a work unit. A master weaver usually owned three to six looms on which he, his family, and his journeymen worked. His wife and children provided invaluable assistance in auxiliary tasks such as winding bobbins. Wives also supplemented the family income by spinning or warping silk for merchants.[6] As heads of a family enterprise, weavers exercised considerable independence.

Yet because weaving was only one stage in ribbon production and, indeed, dependent upon the other stages, weavers could not enjoy complete autonomy. All phases of ribbon production were seasonal, contingent on the silk harvest between May and July as well as on orders from fashion houses in London, Paris, and New York. Silk preparation lasted from three to six months, and looms operated for about eight months of the year. It was in silk preparation and marketing that merchants had gained considerable control by the end of the eighteenth century. Called maîtres faiseur fabricant —they put others to work, or they "put work out"—they had come to direct the bulk of the Saint Chamond labor force that worked in silk. The fabricant experimented with patterns, textures, and colors and decided which ones he would have produced for firms in Paris, London, and New York. He then had raw silk prepared and dyed according to the specifications of the pattern and hired a weaver to produce it. The leading ribbon fabricants of Saint Chamond—especially the Dugas brothers, Dugas-Vialis and Co., Bancel, Gillier and Sons, and David-Dubouchet—were the wealthiest and most important in France.[7]

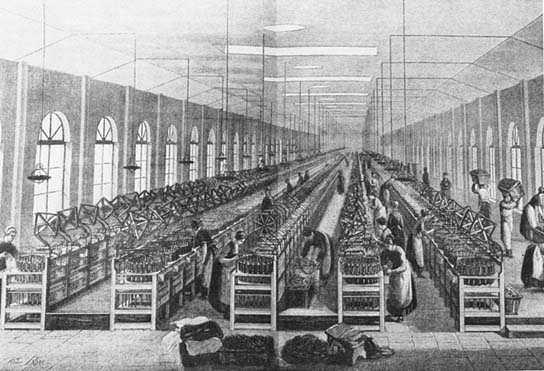

After purchasing the silk cocoons, the fabricant hired young girls

to unravel their single threads and wind them onto skeins. This work lasted approximately three months after the cocoon harvest and was the most distasteful in the silk preparation process. The worker first had to find the end of the single strand that composed the cocoon. She took about six cocoons at once and plunged them in extremely hot water to loosen the gum. She next unraveled all six cocoons while twisting the strands together and then placed them on a skein.[8]

Workers could perform this task in their own homes, but increasingly fabricants employed them in workshops. By the 1830s skeining workshops were equipped with motorized spools and furnaces for centralized heating of water basins. This job especially relied upon migrant labor—young girls who usually returned to their rural villages after the season. As such, skeiners "belonged to the poorest class" and suffered the most miserable conditions. The stench of cocoons permeated the workshop and penetrated their clothing. The constant submersion of their hands into nearly boiling water caused chronic pain. Soaking them in red wine and cold water during breaks and after work provided meager relief. Skeiners earned 60 to 90 centimes for their sixteen-hour workday. Fabricants usually lodged them, but under conditions Villermé described as miserable. They slept two together in beds of straw and ate meals consisting of "weak bouillon, legumes, potatoes, potherbs, a few milk products and sometimes a little codfish."[9]

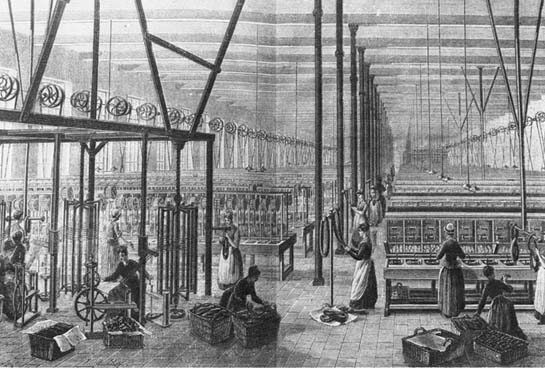

After having the silk skeined, the fabricant then sent it to a miller. Silk millers exercised a profession in their own right, but they too came under the direction of fabricants —they worked as jobbers, fulfilling precise orders. Millers "threw" silk for merchants in Lyon and Saint Etienne as well as for those in Saint Chamond. They too relied on a female labor force, most of whom worked under their supervision in a workshop. Workers placed the skeined strands of silk on a mill consisting of rotating vertical spindles and bobbins. The mill twisted each thread in one of two directions to form the warp and weft, respectively. The tightness of the twist depended on the kind of thread required for the weave of a particular design.[10]

Water powered the spindles that twisted the silk, so the millers clustered along the Gier River, where they employed and lodged in workshops at least eight to ten workers, and sometimes as many

as thirty or forty, who each supervised up to sixteen spindles. The women who worked for silk millers suffered conditions not much better than those of the skeiners. They too labored a sixteen-hour day for 90 centimes. Their employment lasted about six months.[11]

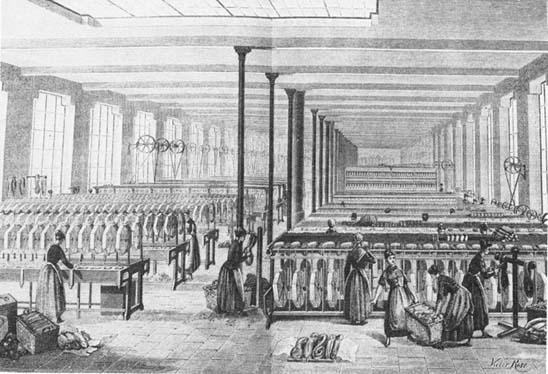

Once the miller completed the job he sent the silk back to the fabricant , who in turn sent it out to a dyer. After scouring, cleaning, and dyeing the silk, the dyer returned it, still on skeins, to the fabricant . There the warp thread underwent one further stage of twisting on wooden spindles. Finally, warpers (ourdisseuses ) performed the delicate task of placing all the strands in a parallel fashion and stretching them with equal tension. Spinners and warpers worked either in their own homes, on the premises of the fabricant , or in the workshops of headmistresses. These processes too became increasingly centralized in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Because their work required skill, practice, and patience, warpers fared somewhat better than skeiners, mill workers, and spinners. They earned 1f40 per day, and some of the older, more experienced women were permitted to work in their own homes. Their work also lasted only six months.[12]

After warping, the fabricant finally sold both the warp and the weft to the weaver. The weaver wove the silk into ribbons which he sold back to the fabricant , who then again employed a female labor force to perform the finishing, including folding and packaging the ribbons for marketing.

With the exception of the weaving and dyeing, this industry from start to finish relied upon an extensive, protean female labor force drawn from both town and country. The women could perform almost all these preparatory processes in their homes, provided they could obtain the proper materials and equipment. But in the first half of the nineteenth century, fabricants and silk millers increasingly organized these workers into workshops. A number of factors made centralization more practical. Most important, fabricants could better supervise the workers as well as the silk itself. In addition, silk could not tolerate changes in temperature or humidity, and keeping the raw materials under the fabricant's supervision assured proper treatment. The concentration of workers in shops also helped prevent the theft of silk and its waste products.[13]

The government inquiry of 1848 reported, not surprisingly, very poor conditions among the mill workers, skeiners, and spinners

who labored in workshops. Respondents complained of overly strict supervision, stomach ailments, and leg varices induced by having to stand for long periods of time or by pumping the spinning-wheel pedal. Because silk could not tolerate atmospheric variations, these women suffered winter cold, summer heat, and high levels of humidity and breathed foul air because windows and doors had to be kept closed. Silk particles caused serious chest irritation. Long hours and workshop discipline surely made conditions there worse than those in workers' own homes.[14]

The history of family and occupational life in Saint Chamond can be retrieved from marriage records, especially when used in conjunction with birth and death records for the purpose of reconstituting families. Records from couples who married between 1816 and 1825 and proceeded to have families in Saint Chamond through the first half of the century provide insight into the relationship between work and family life and into family responses to the technological change that took place during these years. Of the 539 women who married in Saint Chamond between 1816 and 1825, nearly 50 percent declared their occupation as silk workers of some kind (Table 1). Of those, 20 percent wove silk and the remainder declared jobs as silk worker, warper, skeiner, or spinner. Forty-one percent had fathers who wove ribbons.[15] It is impossible to know how many of these women worked in their own homes and how many in workshops; no doubt those who came from ribbon-weaving families assisted their parents when they were needed and worked outside the home during various periods as well.

Whether these women wove ribbons in their own homes or skeined silk in the workshops of fabricants , or both, they could bring valuable knowledge and experience into a marriage with a ribbon weaver. The assistance of a weaver's wife and children played a particularly important role in his productivity. Once the fabricant sold the prepared weft and warp to the weaver, the family had to operate as a tightly coordinated unit. Fabricants habitually gave weavers last-minute rush orders and ruthlessly demanded that deadlines be met. The weaver first had to "mount" the loom according to the pattern and type of ribbon specified in the order. This process took anywhere from one day to more than a week, depending on whether plain or patterned ribbons had been ordered. The task was accordingly painstaking.[16]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition to weaving, wives assisted their husbands in a number of other indispensable ways. As the weaver set up the loom, his wife worked over a canetière , a mechanism that passed the weft thread from the bobbin onto canettes , smaller bobbins that fit into the interior of the loom shuttle. Once her husband finished a ribbon, she picked floss and impurities from it (émouchetage ). Throughout the ribbon production process, she also ran important errands. She often obtained the thread and other materials from the fabricant and did the negotiating with him over prices of materials and labor. Here she could draw on her own experience, either from having grown up in a ribbon-weaving family or from having previously worked under a fabricant . Nearly 60 percent of the ribbon weavers who married between 1816 and 1825 chose brides who had already worked with silk; nearly 40 percent married the daughters of ribbon weavers. The importance of a wife's skills in this trade is even reflected in the literacy rates: 40.2 percent of ribbon weavers' wives were able to sign their marriage records, a rate more than twice as high as that of nail makers' wives. Ribbon weavers themselves were more literate than other types of workers,

because of the accounts they had to keep; it helped if their wives also had such skills.[17] Indeed, marriage served as the point of departure for a family enterprise, for ribbon production depended heavily on the participation of all family members.

If marriage served to consolidate skills, family formation perpetuated them. Of all the ribbon weavers in the older generation present at the weddings celebrated between 1816 and 1825, 83 percent had passed their skills onto a new generation. More than two-thirds of them had daughters who declared occupations in the silk industry. Of ribbon-weaving grooms whose fathers declared professions, 65 percent also wove ribbons.[18] Although the information about fathers' occupations remains incomplete, it does indicate a strong degree of occupational inheritance. As these figures suggest, apprenticeship almost always took place within the family. It began at about age fifteen or sixteen and lasted two to five years. Each of the specialties—plain ribbons, patterned or velvet ribbons, and, later, elastic—required a separate apprenticeship. Though training usually prepared the young weaver to be a journeyman before he reached age twenty, according to one observer it often took three generations to produce an able ribbon-weaver. The ability to weave the fanciest ribbons depended not just on skills learned from one's father but on inborn artistic talent. Occupational inheritance served as the wellspring for each generation of weavers. It also helped shape the industry. In his 1929 thesis on the silk ribbon production Henri Guitton attributed loom innovations to "modest workers who watched looms working under the hands of their fathers, and who, remaining the rest of their lives in their presence … felt the perfection that technology demanded as a function of the needs and possibilities of the moment."[19]

If occupational inheritance helped weavers become inventors and entrepreneurs, innovations in this industry in turn, ironically, made it more difficult for weavers to become masters and to pass skills on to their sons. Although some workers exploited new opportunities and attained a higher status, innovations during the first three decades of the nineteenth century had some negative consequences for the average weaver: looms became less affordable, their greater complexity made the traditional apprenticeship insufficient, and the weaver lost further control over the production

process to an increasing number of middlemen. While ribbon production remained a family enterprise, survival became more difficult and fewer sons carried on the trade.

The first major technological change that ultimately began to proletarianize the weaver came with the Zurich or high warp loom, which brothers Jean-Baptiste and Jacques Dugas first introduced to Saint Chamond in 1765. This loom made possible the simultaneous production of thirty-two ribbons. A single bar in the front that the weaver raised and pushed moved its numerous shuttles. This new loom held such importance for the industry that Louis XVI ennobled the Dugas brothers and the government granted premiums of 70 francs annually for eight years to anyone who would obtain one. By 1777, Saint Chamond's fabricants supplied silk to 2,400 Zurich looms in and around the town.[20]

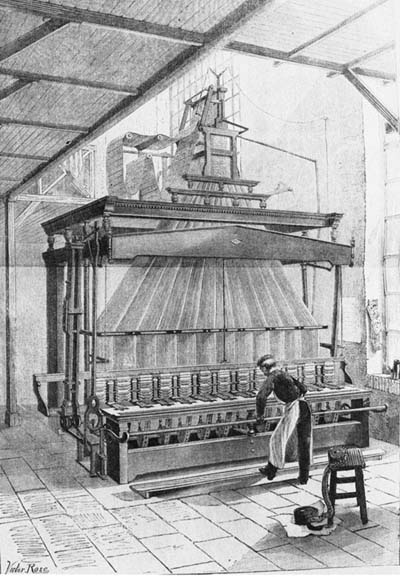

Their size and complexity made Zurich looms much more expensive than the low warp or tambour looms. Moreover, the simpler looms continued to operate because the shuttles of the Zurich could not produce the same variety in size and patterns. Jacquard originally designed his mechanism for the looms in Lyon that wove single pieces of fabric. Its adaptation to the Zurich took several years, but it ultimately improved the versatility. Weavers in the Stéphanois began using the Jacquard with a single shuttle for simple designs in 1824. The same loom with several shuttles for large designs and brocades became standard throughout the region within the next eight years (see figure 3).[21]

As a result of the Jacquard, the situation of ribbon weavers became worse in some respects than that of silk weavers in Lyon. By the 1850s, looms in Lyon cost 250 or 300 francs. But in Saint Chamond and Saint Etienne, because of the adaptations made in order to produce numerous ribbons simultaneously, the Zurich and Jacquard looms cost 1,000 francs. Those made of walnut or mahogany sold for 2,000 to 3,000 francs. Such enormous capital outlay began as early as the French Revolution to restrict the number of loom owners, especially since government premiums had ceased by this time.[22]

In addition to raising the price of looms, the Jacquard mechanism made them much more complex. Its main innovative characteristic was that it reproduced patterns automatically. Two specialized workers, a sketcher (dessinateur ) and reader (liseur ) performed

the preliminary work to set up the mechanism. Their task bore similarity to that of a modern computer programmer. The sketcher drew the design on graph paper with conventional symbols to indicate how the weft thread would produce the pattern. Using a mechanical language, the reader punched into cardboard the intended movement of the warp threads during the passage of the loom shuttle. He then placed this program on a cylinder in the loom, and the pattern reproduced itself automatically as the weaver moved the shuttle. This job required more skill than that of the sketcher and at least three years of apprenticeship—as much training as most weavers required.[23]

The Jacquard mechanism thus removed from weavers one of the stages in ribbon production: implementation of the designs. As one observer put it, with the Jacquard "the ribbon weaver has no need to know how to read the cardboard designs in order to reproduce them. He is no longer anything but a simple agent who executes an operation."[24] Instead, the sketcher and reader took over this task in the fabrication of patterned ribbons. They too were hired by the fabricant . The reader in particular became a key intermediary between the fabricant and the weaver, for he installed the punched cardboard for the latter. This mechanism also made the job of mounting looms far more painstaking, because the weaver had to avoid damaging the punched cardboard and the cylinder. Fabricants imposed stiff financial penalties if any damage did occur.[25]

Though weavers continued to work in small family workshops, these technical advances divided the labor by gender and by geography. Women mostly wove on the low warp and tambour looms, which produced plain ribbons. Looms fit for patterned ribbons became increasingly difficult for them to operate because decorative and metallic thread made the shuttles weigh at least 130 pounds. In addition to becoming male-dominated, the production of patterned ribbons became urban-centered. Their delicacy required closer supervision both in their production and in regulation of the patterns themselves—in the hilly and mountainous countryside within a radius of five or six kilometers from Saint Chamond, weavers tended to plagiarize designs. Thus advances in loom mechanisms during the first thirty years of the nineteenth century were concentrated in towns and cities; weaving in some of

the rural areas outside Saint Chamond became exclusively a female occupation, while in the city itself it became predominantly male.[26]

From about 1830, when the Jacquard loom became standard in Saint Chamond, the multiplication of processes carried out by others complicated the weaver's task and denied him access to some of the specializations. Once he had received an order, for example, he had to make as many as twenty errands to the fabricant 's shop to obtain the necessary silk and loom pieces. Often he would be promised silk in the morning and then waste an entire day standing at the shop's door waiting for it. Sometimes it took ten to fifteen days to collect all the necessary prepared pieces just to begin weaving. As respondents to the government inquiry of 1848 put it, the time a weaver spent running errands and waiting cut into his work, "his only property."[27]

The ribbon weaver was held fully responsible for the quality of the finished ribbon. If the dyer, sketcher, reader, or warper had made mistakes, the weaver had to correct them or see that they were corrected, which stole more time from his weaving. His wife's contribution toward these time-consuming chores, particularly the running of errands, became ever more important as the fabrique grew more complex.

The increased need to supervise the production of patterned ribbons led to the introduction of a third middle person between the weaver and fabricant : the commis de barre , who took over functions the weaver had once performed himself. Barre referred to the bar on the front of the loom that moved the numerous shuttles. The commis found "bars"—weavers—to carry out the orders for the fabricants . In addition to scouting for weavers, the commis negotiated prices, surveyed the work, and regulated disputes on behalf of the fabricant . Most often the commis had been a ribbon weaver himself and continued to oversee a workshop. He might own three or four looms worked by his family and journeymen. His own experience as a weaver had taught him the commercial side of the industry. He had learned to negotiate shrewdly with fabricants and commis and had acquired a business sense about the prices of raw materials and the market for finished products.[28]

The increased reliance on commis caused considerable vexation. They received 5 percent of the price the fabricant paid the weaver for ribbons, further cutting into the weaver's wages. More complaints

had to do with the humiliation to which commis subjected weavers. It was the commis who often demanded the order be filled within an unreasonably short period of time so that he could then extract more from the weaver's pay as a fine. Under pressure from the fabricant , the commis also went out of his way to detect imperfections in the ribbon. He frequently cheated the weaver by finding fault with the ribbon's color, texture, or pattern and holding him responsible for mistakes the sketcher, reader, dyer, or warper had made. Most often the weaver would not risk going before the Conseil des Prud'hommes to complain, for fear that the fabricant or commis would stop giving him orders. Although weavers worked successively for several fabricants , they could not afford to alienate any of them for fear that they would not be chosen to work during the commercial slowdowns that came so frequently in the ribbon industry.[29]

The higher prices of looms, the increased subdivision of work into specialties, and the greater reliance on commis began to influence the ribbon industry most profoundly after the Jacquard loom became a mainstay in the Stéphanois region during the 1820s and early 1830s. Responses to the government inquiry of 1848 reflect their impact. Most complaints referred to the cheating commis . Saint-Chamonais described the relationship between weavers and commis as "feudalistic": weavers received "protection" if they were family members of the commis or if they had provided certain "services" to the commis or fabricant , particularly sexual favors from their wives or daughters.[30]

Weavers also expressed deep concern about their loss of control over specializations and their decreasing ability to equip their children with the skills necessary to operate the more complex looms. They deplored the traditional methods of apprenticeship for their arbitrariness. In other words, inheriting skills from a family did not adequately equip a young weaver for the new technology. A father's knowledge and experience no longer sufficed. They called for a professional school that would provide theoretical as well as practical instruction in all types of looms, in punching cards for the Jacquard (mise en carte ), in designing patterns, and in loom mechanics.[31]

Respondents to the government inquiry also complained bitterly about the occupational hazards of ribbon weaving, some of which