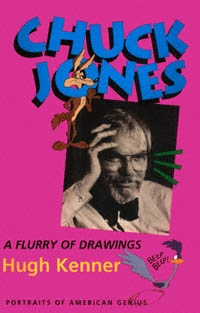

Preferred Citation: Kenner, Hugh. Chuck Jones: A Flurry of Drawings, Portraits of American Genius. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6q2nb3x1/

| Chuck JonesA Flurry of DrawingsHugh KennerUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1994 The Regents of the University of California |

For Harry McCracken

Preferred Citation: Kenner, Hugh. Chuck Jones: A Flurry of Drawings, Portraits of American Genius. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6q2nb3x1/

For Harry McCracken

Preface

Chuck Jones had a great-uncle Lynn who used to tell him that a pig could not be made into a racehorse. What might reasonably be hoped for, he said, was "a mighty fast pig."

So postulate a kid born, 1912, in Spokane. Endow him with a directionless passion for drawing. Enroll him in what was available, Chouinard Art Institute, in Los Angeles of all places, at a time when L.A. was a parvenu's paradise, a cultural desert. Next—1930—plunge the world into economic despair. Sit back, wait. No, do not expect a Malibu Leonardo. But, should genes and fortune and circumstance conspire just so, you may be rewarded with a surprising version of Uncle Lynn's "mighty fast pig."

Such is one approach to Charles Martin (Chuck) Jones, indisputably a master in an art—he'd have called it a trade—that only now is starting to be defined. That was motion picture Character Animation, and it flourished in One place in

the world—Southern California—for perhaps thirty years (say 1933–63). Its several dozen practitioners (or several hundred; definitions are elastic) had the good fortune never to be aware that they were practicing anything resembling an art. (Otherwise put: neither did Animation Critics exist, nor were any Traditions easy to lay hold of.) It flourished thanks to economic givens that ought to have made anything of lasting interest impossible. Then it faded amid paeans to social progress. (And the brief flowering of Periclean Athens: was that perhaps equally chancy? We simply do not know how such things happen.)

Chuck Jones, 81 at this writing and going strong, now finds himself firmly installed in Animation History, a domain of learning that commenced to flourish less than two decades ago. One early instance is the January–February 1975 issue of Film Comment . Another is Jay Cocks's "The World that Jones Made," in the December 17, 1973, issue of Time . Though generous to Jones's way with studio properties—Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck—Cocks drew special attention to the glorious one-shots: One Froggy Evening, notably; and Duck Amuck, which the priesthood is now about ready to call "self-reflexive." Should you ever face the solemn task of preserving just one six-minute instance from the unthinkable thousands of hours of animated footage that's accumulated since—oh, since 1914, you'd not go wrong in selecting "a Jones."

To savor such wonders you need to examine them repeatedly; and as long as they existed only on film, high cost kept access restricted to affluent fanatics. A like situation obtained in the long centuries when books were accessible solely via manuscript copies, too expensive for individuals to dream of. Today the video cassette recorder permits most of us to own

the classics of animation, and certainly the finest work of Chuck Jones, at the total cost of a dinner or two or three on the town. For whatever purposes the VCR may have been marketed, friends of animation at least may perceive its worth. It's one more prizeworthy mighty fast pig.

The Jay Cocks article first alerted me to Chuck Jones. A letter to Cocks fetched a Jones address; then a letter to Jones brought Jones to Baltimore, where, one memorable afternoon and evening, he discoursed, drew pictures for children, and showed a Johns Hopkins audience a film anthology. The texture of the discourse was memorable; I wish I could recall who it was he characterized as "a trellis of varicose veins." And the films—I'll not forget Arnold Stein the Milton scholar, inclining his head after One Froggy Evening to confide, "That was simple . . . and AB-so-lute."

As it was.

At Corona del Mar, California, in July 1990, I saw Chuck and Marian Jones daily for a week. What got taped on those visits is a primary source for this book. Though I've since tried to cross-check facts, I can't guarantee them. Animation history remains rife with vagaries of human memory. Meanwhile it seems worth setting down what I can offer.

A word about printed sources. In addition to the January–February 1975 Film Comment, and one article in a later issue (May–June 1976), I've drawn on Jones's own 1989 memoir Chuck Amuck, on Steve Schneider's 1988 That's All Folksh!: The Art of Warner Bros. Animation, on Joe Adamson's 1990 Bugs Bunny: Fifty Years and Only One Grey Hare, and on John Grant's Encyclopedia of Walt Disney's Animated Characters (second edition, 1992). I've not meticulously acknowledged every use,

partly to keep footnote clutter thinned out, partly because my most frequent recourse to a book or an article was for cross-checking something I'd heard from Chuck Jones. Like all great raconteurs he tends to have formulaic versions of key stories, and when what I heard was almost word for word what another interviewer had heard I felt under no obligation to dwell on the fact.

Four people I've never met helped make this book possible. Jennifer Jumper in Seattle was heroic in transcribing tapes riddled with nonsense such as airplane noises. Dave Mackey in Oakhurst, New Jersey, made a key video available and has since answered flurries of queries. Paul Raulerson in Eagan, Minnesota, explicated the computer's way of handling a comma. And Harry McCracken in Arlington, Massachusetts, put at my disposal his tape library and his vast knowledge of Animation History. I'm in touch with the four of them thanks to a computer network: the Byte Information Exchange (BIX). We enjoy a high-tech age and ought to acknowledge it.

—H.K.

AUGUST 1993

Note on Illustrations

All the illustrations in this book were drawn by Chuck Jones. They are reproduced, with his permission, from his informal autobiography, Chuck Amuck, and from a model sheet he designed to guide the animators of Rikki-Tikki-Tavi .

More important are the key Jones films on VCR tapes. If you've trouble finding them locally, a phone call (Monday–Saturday, 9 A.M .–6 P.M . Pacific time) to (206) 441-4130 will fetch you the Whole Toon Catalog, and what Whole Toon can't find it's a good bet nobody can.

A Flurry of Drawings

Animation, like life itself, relies on natural principles. Life requires simply (simply!) DNA. Animation requires Persistence of Vision. That means: anything you've glimpsed you'll go on seeing for maybe a tenth of a second after it's gone. If meanwhile a different glimpse gets substituted, the two will blend smoothly. And if they depict successive stages of movement, you'll swear you saw something move.

Ways to substitute the next image derive from flip-books, which have been around since at least the nineteenth century. On the bottom margin of a school scribbler, a sketch of a car. On successive pages, the same car, shifted incrementally rightward. Now. Riffle the pages! Watch that auto move!

To check what they've done, animators riffle stacks of pages. No single drawing stands out. Single drawings, however highly finished, may at best—Chuck Jones says—serve to help us remember some animated sequence we recall en-

joying. But Animation itself Jones calls that "a flurry of drawings." How they're shown is less important than their flurry. A flip-book can display a couple of seconds' worth. For something longer, best photograph each frame; then let a projector sequence them on a screen, fast enough for Persistence of Vision to blend them. Sixteen frames per second was fast enough in silent-film days. Sound, when it came about 1928, required twenty-four because film that carried sound had to move faster. But the eye doesn't need that many; twelve per second will do for the eye. So sound helped ease the animator's lot. Instead of sixteen drawings per second, twelve will suffice, each photographed twice. The eye will detect no jerkiness.

A flurry of drawings: one by one by one. Draw the starting pose; then draw the next instant, then the next, clear to the end of this flurry, each image a modified tracing of the one before it: that's called "animating straight-ahead," and it's how all animation was done for a couple of decades, right into the age of sound, sixteen for each second. In 1914, Winsor McCay's many thousand straight-ahead drawings made Gertie the Dinosaur huff, stomp, lower her neck. Chuck Jones, as he likes to remark, was then two years old. "It all happened within my lifetime." (And McCay, born 1871, lived till 1934; by then Jones, 22, had enjoyed three years of breathing animation's ozone.)

McCay redrew every detail of every frame: not only Gertie, who'd shift from glimpse to glimpse, but also all those things that shouldn't shift: rocks, mountains, trees, horizon. Retracing those with machine-like accuracy being simply impossible even for his (or his assistant's) steady hand, they flickered and shimmered around Gertie. In its time, the effect

did seem rather charming. But what a redundancy of effort! A way to draw a background once, for reuse many dozen times, was one thing that would raise animation above slave labor. It would also permit something later to prove indispensable in establishing a world (stable) that contained characters (a-move). That was a perfectly unambiguous distinction between what was meant to stay rock-steady and what wasn't.

Not that McCay's audiences needed that distinction. When he took his film on tour, and stood beside the screen with a pointer to conduct dialogues with Gertie, many were unclear that they were looking at drawings. Some kind of real animal, surely, though oddly drained of color? Or maybe some kind of model? It's hard to realize how long we can take simply learning to perceive a novel medium. (How about a voice in your head, with no one else in the room? When a prominent Boston lawyer heard the "telephone" demonstrated about 1876, well, after pausing long in embarrassment he came up with nothing better than "Rig a jig, and away we go!")[1]

Nor would slave labor have entered McCay's thoughts. Like many pioneer animators, he was driven by a passion for drawing. To make a hundred pictures in a morning, that was sheer heaven!

We're talking of a gone time of linked passions. Moviegoers had a passion too, for nothing more subtle than the sheer illusion of motion. It sufficed that on a wavery screen they saw—galloping horses! (And therein lay the germ of the Western.) Chuck Jones remembers when it was hilarious

[1] It was Bell's assistant, the famed Mr. Watson, who recorded this. See Avital Ronell, The Telephone Book (1991), pp. 227 ff.

if an animated walker just hopped once in a while, an effect he's used himself in several films. A story? That could emerge from whatever some animator happened to think of next.

(And to keep things steadily lined up, put a row of pegs on the table, to fit holes along an edge of what's being photographed. Raoul Barre thought of that in 1914. Every cel, every sheet of animators' paper, has worn those holes ever since.)

The reusable-background problem was solved, after several fumbles, in 1914: U.S. Patent #1,143,542, issued to Earl Hurd. His solution wasn't obvious, discarding as it did the natural supposition that the drawings the camera would see would be the ones drawn on paper. No. Draw the background—once—on paper. Then trace each of your "moving" drawings onto celluloid. Under the camera, lay each "cel" in sequence over the background; click the button for each. Voilà!

That process created two new occupations: cel-tracer, celwasher. The tracers have now mostly been automated out, and a good thing too, since, careful though they might be, they lost subtleties. Run Jones's How the Grinch Stole Christmas on your VCR; examine the wiggly lines that delineate the Grinch's haggard face in closeup; no way those wiggles could have been reliably traced. By Grinch-time (1966) an unwavering Xerox eye was transferring the animator's every nuanced line to the cel. (Opaque areas—after color came in, colored ones—got painted inside the outlines by hand, and still are.) And the washers? Their job was to permit reuse of precious celluloid, by cleaning the paint off cels that had been photographed. Chuck Jones, at 19, commenced his long life in animation as a cel-washer.

He'd been hired by Ub Iwerks of the (yes) Dutch name, and who was Ub? Ubbe Ert Iwerks, who'd come west in 1924 to rejoin his Kansas City partner Walt Disney. They were both 23. It's no secret that Ub's drawing was more resourceful than Walt's; that he co-created Mickey Mouse; that he, single-handed, animated the pioneer Mickey cartoons, notably the 1928 Steamboat Willie . That was the cartoon that made history with fully synchronized sound, thanks to Walt's nigh-infallible nose for trends. By 1930 an entrepreneur named Patrick Powers had persuaded Ub (wrongly) that he was more important than Walt, and set him up in a studio of his own. Ub proceeded to produce films starring Flip the Frog, who flopped. He had, alas, Chuck Jones recalls, "no sense of humor." That was a considerable drawback.

Ub Iwerks did excel at technical challenges. When Flip climbed a stair the viewer's eye climbed with him, so the stair's perspective shifted with every frame. That called for ultra-resourceful animating.

Later, back with Disney, Ub would tinker with such things as Xeroxing cels instead of hand-tracing them, and with processes for achieving a seamless blend of live action and animation. (There seems to be no substance to printed reports that he fathered Disney's Multiplane project, the camera looking down through widely-spaced cels to automate shifts of perspective as viewpoints shifted. True, he worked on such an apparatus. But the long opening shot of Pinocchio, a Multiplane tour de force of 1940, preceded Ub's return to Disney.)

Anyhow, in 1931, with an infusion of cash, Tycoon Iwerks had been on his own; hiring the likes of cel-washers; also importing from the east animators of the quality of Grim Natwick.

"Grim" is said to be what he'd uttered as a toddler, trying to pronounce his real name, which was Myron. Born 1890, and not gone till after he'd passed his hundredth birthday—Lord, like symphony conductors, animators are long-lived!—Grim Natwick had commenced animating as far back as 1916, for the Pathé Studio in New York, where he'd finish eight dozen straight-ahead drawings before his lunch break. Later, with the Max Fleischer people, he laid claim to what then didn't look like immortality by creating Betty Boop, at first a little dog with spit curls that walked on its hind legs to perform a Boop-boop-a-doop vocal identified with a singer named Helen Kane. (In those early days of sound, animating pop hits was one sure cartoon formula.) By three more films the dog's droopy ears had become earrings, and Betty was, well, Betty. Grim Natwick was the envy of other Fleischer animators because he could join Betty's hand to her arm with a wrist; could even manage knees. That was because he'd had formal art-school training. Most animators, then and for decades to come, learned their craft by merely tracing photographs. When photos weren't available, the arms and legs they drew evaded knees and elbows by bending like rubber hoses.

(Tracing photos, a technique much exploited by the Fleischers, is still known as "rotoscoping." It's a way to get a quick fix on humans, who can be filmed in action as no Bugs Bunny can be. It is widely regarded as cheating. It was also a way to manage Snow White 's wooden prince, rightly noted as that landmark film's principal lapse. Yes, action footage of a girl walking and dancing—the model would become better known as Marge Champion—was studied by the animators of the princess, but those frames weren't for tracing. In changing her overall height from eight heads to five, Hamil-

ton Luske, the man in charge, detached her from human proportions and her artisans from tracery.)

And, long before Snow White was thought of, here's Grim Natwick, 41, at the Ub Iwerks studio. And here's a 19-year-old cel-washer, Charles M. Jones, equipped, like Grim, with a species of formal art-school training. And (Grim would recall) "I took him out, bought him an ice cream soda, and taught him all about crooked lines." Ah, esoterica!

Eventually—the details are elusive—Chuck Jones became Grim's Assistant Animator.

That sounds more grandiose than it was. Assistant Animators were earlier dubbed "In-betweeners," and their craft, like cel-washing, depended on a technical advance. That was the observation that if animators drew key poses—a left foot hitting the ground, a right foot ditto—then the frames in between, the ones that shifted the walker from left foot to right foot, could be as routine to draw as they were to walk, and might as well be assigned to anyone with the skill just to draw at all. (Standards would rise, but that was the way it looked then.) "How fast is the walk?" would translate into "How many in-between frames?"—an instruction the animator could relay. That was the end of straight-ahead animation. Thenceforward, Key Poses and In-betweening By the Numbers. As a dividend, a bright In-betweener might be learning to animate. Most animators of the Jones generation and since have learned their craft In-betweening. (Also, a few In-betweeners have been discerned who seem happy to use up their lives just In-betweening. Chuck Jones doesn't pretend to understand them.)

It all made economic sense too. Animators were freed for uniquely productive work, while In-betweening could be left to the peons. For a labor-intensive industry had long been

sorting out its skills. Someone (Disney, Fleischer, Iwerks) in charge at the top. A few key creative people—Animators. Eager In-betweeners, making maybe nine-tenths of the drawings. A background artist or two. And a phalanx of anonymous inkers and painters, to fuss with the cels the camera would actually see. And, no, don't forget the cameraman; we need him. And some folk to whomp up the sound. Oh—don't forget the story either. We'll return to that.

And what, really, was it all about? That depends on the angle from which we calibrate "really." What the moguls saw—we'll start with them—was money (not much) dribbled out to gaggles of odd people, in return for some hand-drawn footage every week or two. Back when just seeing something move was a delight, audiences had formed the habit of expecting such footage; thus a novelty had become a program fixture. By the 1920s the Pat Sullivan studio, which was mostly Otto Messmer,[2] was affording audiences a routine fix with Felix the Cat, the first clear-cut instance of Character Animation. (Gertie? She'd been a prop for the real character, her creator.)

Felix, whom Messmer cannily reduced to some brushable blobs, routinely stalked, pondered, triumphed. "I put emphasis on personality in Felix," Messmer would recall: "eye motion and facial expressions." He'd long since discovered he could "get as big a laugh with a little gesture—a wink or a twist of the tail"—as he could with gags. That meant, he'd created a Character: an emblem audiences could invest with expectations, disappointments, triumphs. It's unknown how

[2] Died 1982, aged 91. Note the pattern of longevity.

many Felix films got made, several hundred anyhow, and an effort to remember that they all preceded sound. It was also a symptom of emergent custom that O. Messmer's name wasn't credited, just Pat Sullivan's. Pat Sullivan was the Producer, i.e., the financial liaison. But he even got himself photographed as if his days were spent animating.

Sound brought in a new stimulus: music. Audiences could now stomp their feet. And studios tended to own music companies. Warner Bros. owned perhaps six. Aha! Such eyes as Jack Warner's lit up with dollar-signs! Music could bring continuity to Looney Tunes, and the cartoons could help sell the music. For several years that seemed a primary reason to make cartoons. "When I was young," Chuck Jones remembers, "music publishing was a big business because . . . oh, people played the ukulele." (Nowadays, adept with chords on the guitar, many strummers feel no need for sheet music.)

Sound was in some ways a regression: would a hallful of foot-stompers ever miss Character? But yes, a demand persisted for Mickey Mouse, whom Disney and Iwerks had created just when sound was dawning. So for years the Disney output was bifurcated—in alternate fortnights, a Mickey Mouse (character), a Silly Symphony (foot-stomp). Luckily, Walt Disney came to see the Silly Symphonys as carte blanche to just play around. Playing around can pay off. May 1933 saw a turning point in animation history. That was a Silly Symphony called The Three Little Pigs .

In the mid-thirties it was a sensation, a cartoon that went on playing week after week while features came and went behind it. After fifty years it remains amazing. A governing tune—

Who's afraid of the Big Bad Wolf

Big Bad Wolf

Big Bad Wolf

keeps two pigs a-hopping and a-fluting and a-fiddling while a Practical Pig lays bricks.

And they Hop and they Flute and they Fiddle tweedle dee and Again and Again fiddle fie fee fee and the Wolf jumps WHOMP and they Gallop and they Stomp as their Practical friend can see.

The third pig's rhythms are prosaic compared to theirs; diddle diddle diddle diddle isn't his life style. At bottom it's the old theme of the Ant and the Grasshopper, the Ant thoughtful for tomorrow (a wolf may arrive at the door), the Grasshopper incorrigibly toujours gai .

Chuck Jones compares Walt's founding of the Disney Studios with the founding of the New Yorker by Harold Ross at about the same period. If Ross was no great writer, neither was Walt a great animator. But each created a milieu in which greatness could flourish. And greatness, insofar as it's attachable to animation, undoubtably attaches to The Three Little Pigs, three characters (says Jones) who are characterized solely by the way they move, since they look exactly alike. (Before that, he adds, villains were heavy, victims not. That simple distinction continued into the days of Bluto and Popeye.) Unique selfness, inherent in a way of moving: that is the essence of the Character Animation we're keeping track of. Reality inheres in rhythm.

So yes, yes, things were happening backstage, not always beknownst to studios like MGM and Warners which owned chains of theaters, by the early 1930s all "wired for sound."

Into their theaters they dumped their two-hour "product." That meant, more or less, a ninety-minute feature every week, plus a newsreel, plus a two-reeler, plus a cartoon. A reel is about nine minutes. Cartoons got shaved to seven minutes, then to six. But, however brief, a cartoon there had to be. Lacking it, the package would have seemed short-weighted.

In a way, it's as simple as that. Hence all those flurries of drawings.

Termite Terrace

In 1912 the Titanic sank, a man named Funk coined the word "vitamin," Robert Scott reached the South Pole, "Piltdown Man" was exhumed, Jim Joyce turned thirty, and Sam Beckett six. Also New Mexico was admitted to the Union (hence Bugs Bunny's formulaic "Left turn at Albuquerque"; and later the roadrunner, Geococcyx californianus, would become New Mexico's state bird). Moreover, the 1912 autumnal equinox—21 September, a Saturday—saw Charles Martin (Chuck) Jones born in Spokane.

That year was pre-TV, pre-cinema, even pre-radio. (Yes, wireless and movies existed, but no, they didn't dominate the time of any folk save tech fanatics.) That left, well, books, so if you felt unsleepy your recourse was reading. It was also your rainy-day recourse, and, when necessary, your way of cocooning yourself when you were the third of four and your siblings were, all three, assertive. ("Margaret Barbara Jones, master weaver and designer, teacher and fabric designer;

Dorothy Jane Jones, sculptor, writer, and illustrator; Richard Kent Jones, painter, photographer, teacher, and printmaker": that's the roll-call that also includes "Charles Martin Jones, animator and animated-cartoon director.")[1]

He was formed by literacy and is still focused on it. In the heat of discourse he'll drop a phrase from a book every few sentences, and frequently pause to credit it. In his wonderful memoir, Chuck Amuck, he recalls a long-ago cat named Johnson uttering "a single laconic 'Mckgnaow.' " A footnote credits James Joyce's Ulysses, "but Johnson said it first." Now what Leopold Bloom's hungry cat said that Dublin June morning was something slightly different: "Mkgnao."[2] The point is, Jones is quoting from memory, something the truly literate have the confidence to do. He was writing a book that doesn't pretend to scholarship, and felt no special impulse to reach for the shelf, flip pages, verify. His points get made: Johnson, an authentic cat, spoke authentic cat-speech, and Joyce, an authentic writer, got cat-speech right. As does Jones, thanks to the real Johnson reinforcing Joycean fiction the way (as Joyce fans will verify) reality normally does.

Chuck Jones insists on the reliability of authentic writers. Here's Mark Twain on the coyote: "The coyote is a long, slim, sick and sorry-looking skeleton, with a gray wolf-skin stretched over it, a tolerably bushy tail that forever sags down with a despairing expression of forsakenness and misery, a furtive and evil eye, and a long sharp face with a

[1] Chuck Amuck, p. 45.

[2] And with further urgency, "Mrkgnao!" and "Mrkrgnao!" Readers in need of rigorous detail about feline vocal resources should consult Muriel Beadle, The Cat (1977), pp. 186–8.

slightly lifted lip and exposed teeth. He has a general slinking expression all over. The coyote is a living, breathing allegory of Want." Whether that's the authentic coyote of the wilds I've not the experience to say, but it's unmistakably the Wile E. Coyote that Chuck Jones created in 1949, thirty years after he'd "devoured" (he says) Twain's Roughing It at the ripe age of seven.

It's interesting that he doesn't mention being taught to read. In those days many lifelong readers weren't taught to read, any more than they were taught to walk. They just somehow picked it up, frequently by listening to a parent read while a finger moved along the lines. What Jones does mention, more than once, is the abundance of books amid which he grew up. His father, who emerges as fascinatingly feckless, moved the family frequently, always to a rented house so well stocked with books it once took the lot of them a five-year stay to read everything. And they did read everything, trash alongside treasure, discerning a difference but reading both kinds anyway. "It was entirely impossible for me to read without thinking, and reading The Bobbsey Twins, for instance, made me think of throwing up."

He'll also dwell on his father's admiration for a writer who understood gists and how to get them together.

Once, on a glittering ice-field, ages and ages ago,

Ung, a maker of pictures, fashioned an image of snow.

"That's Rudyard Kipling!" said Mr. Charles Adams Jones. "Everything you need to know about his subject, Cro-Magnon man: Who. What. When. Where. In poetic form. In one sentence." If, despite T. S. Eliot's approval, Kipling's repute

does not currently thrive, still it's interesting to note how rapidly Eliot had put "everything you need to know" about J. Alfred Prufrock into twelve opening lines in 1909, and how quickly Chuck Jones got the gist of a demolition worker with dollar-signs in his eyes into the opening moments of One Froggy Evening (1955). Jones had fewer than 400 seconds in which to present his whole fable, never forgetting the need to keep an audience continuously spellbound. No one else got Warner Bros. cartoons under way with such economy.

No one else, either, had so literary a conception of character. Where it had sufficed other animation directors to make Bugs Bunny anarchic, anarchy being the medium's richest tradition, the Bugs of Jones won't declare that This Means War till after his space has been wantonly violated, as by a hunter in Wabbit Season (Duck! Rabbit! Duck! ) or by a furious bull in the ring (Bully for Bugs ). Otherwise Bugs improves his shining hour with the tranquil aid of a carrot, thoughtfully munched. That resembles the care novelists take over motivation, to help as they routinely do a print-bound reader who's unable to see a book's characters unless in what we're not discussing, a "comic book."

Ah, all those books! And Jones's verbal memory for them, up to seven decades later, is incredible. It is simply not true that the human sensibility necessarily divides eye-people from word-people. (Animators are eye-people, yes?)

And another theme: all that paper! The way Chuck Jones tells it, every time his father launched a new enterprise, letterhead got printed on high-quality stock. The supply of such enterprises seemed as inexhaustible as their timing was luckless—who but Jones Sr., with a short option on Signal Hill, would have entrusted geraniums "for the Eastern market" to its oil-saturated earth? The Jones children, though, lived

amid unimaginable quantities of Hammermill Bond paper and Ticonderoga pencils. Consequently, they all became visual artists. When Kimon Nicolaides at the Art Students League advised a beginning class that their learning process would involve getting rid of the 100,000 bad drawings they had inside them, Chuck Jones was already well past his third hundred thousand.

At the Chouinard Art Institute, as we've noted, he learned among other things the sort of anatomical knack Grim Natwick also commanded, for instance with wrists and knees. A fascinating drawing shows us how, if we've learned to make an image of a human leg that contains some anatomical insight concerning its bones, we have only to adjust a few proportions to draw the leg of a horse, a dog, a cat . . . "Same bones," says the caption in Chuck Amuck; "different lengths

only." So the fact that few animated cartoons used human characters wasn't relevant. As we can see a few pages further on (266–7), the familiar Warner Bros. Repertory Company consisted of humanesque figures with animal faces and proportions. For here, their gazes locked in confrontation, behold a housecat (sitting) and Sylvester (erect on hind legs).[3] Despite mild similarities of detail they are clearly denizens of different universes; you'd not get a Sylvester by propping that cat erect. Conversely, Bugs in the posture of a crouching rabbit looks cramped and unBugsy. He ought to be upright, one arm akimbo, the other flaunting a carrot. And as for the coyote: the real or zookeeper's coyote, as drawn by Jones, looks rather like a sheep. But Wile E. has arranged his bones in simulation of a hobo's leisure, recumbent, right forepaw supporting an unkempt head on which that scheming expression isn't anything conceivably natural to Canis latrans . ("Dog who howls," yes, that's the coyote's official name. It's noteworthy that Wile E. Coyote in most of some two dozen films didn't utter a sound.)

Let's return briefly to the redoubtable parents. Charles Adams Jones, born on a Friday the thirteenth, was "meant to be a Baptist minister in Texas." His parents, the ones responsible for meaning him to be that, "were born in a tiny town that doesn't exist any more called Adams, Texas, because the ancestors were related to the Adams family." Whew. So, "Father grew up and became conversant with the Bible and was valedictorian of his high school class and received a full scholarship to Carnegie Tech." Unhappily, he couldn't accept

[3] Sylvester? He's the cat best remembered for being obsessed with Tweety the canary. Seldom a Jones character, he generally worked for his designer, Friz Freleng.

it because he had to help support his family. So by 25 he'd become railroad yardmaster in San Francisco, from which his next move was to Panama, where they had their minds on a Canal. "Both my sisters were born in the Panama Canal Zone. And I was conceived there, but born in Spokane, Washington. I never forgave him for that. It's much more elegant to say you were born in Panama, at least I thought so—in the tropics." Father, "a sort of Richard Harding Davis," loved the idea of living in the tropics. So he always dressed in white and wore boots. "God, he was a good-looking, beautiful, handsome man."

Mother? Mabel McQuiddy Martin, "born in a place called Nevada, Missouri." Pronounce that Ne-vay -da. And raised in Schnute, Kansas, where she was "belle of the town." Charles Adams Jones came there to visit a friend, spotted the belle, "hired a pair of spanking bays and a carriage with the fringe on top, swept her off her feet, took her away for a honeymoon in New York and then down to Panama." Next, Metropolitan Life hired C.A.J. to manage its northwest territory; hence the move to Spokane just before the birth of our Charles Martin, who bears his father's first name and his mother's maiden name and goes by "Chuck." C.A.J. didn't like living in Spokane, any more than his son was to relish having been born there instead of in Panama, "so much more elegant to say." So Jones Sr. "headed for Southern California, and that was the last of being wealthy. He kept starting new businesses and failing." And the kids had all that Hammermill Bond to use for drawing-paper, and all those pencils. "I think all kids will draw if they're encouraged to do so" is Chuck's answer to a question about where the talent may have come from. Encouragement, doubtless, is part of the story. But also there was their mother's attitude:

"She was willing to make the sacrifice most parents will not make: she would not criticize, and she would not over-praise. Years later she told me that if we brought a drawing to her, she didn't look at the drawing, she looked at us. And if we seemed to be excited, then she would be excited. But if I just brought a drawing for, you know, just because, then she would look at it . . . and she would never say 'What's that?' or 'Is that Daddy?' or anything like that. She would look at it and say, 'My, you used a lot of blue, didn't you?'

"No criticism. Also no over-praise. Praise probably hurts more than anything else. You come running over with a drawing, and they say, 'Oh, that's wonderful,' and stick it up on the refrigerator. After a while the child says, 'Look, I know all my drawings aren't good.' And loses interest because, obviously, the parent had lost interest."

Chuck Jones was 15 when he entered Chouinard after not graduating from high school, and in the time he spent there he had no glimmer of the use to which he'd one day be putting the anatomy they were teaching him. His stint of cel-washing at the Ub Iwerks establishment (1931) came after some futile months at a commercial art studio, where he was dogged (he says) by a post-Chouinard inability to draw. (Subsequently, he hastens to add, ten years of night school and "the great teacher Donald Graham" would enable him to claim that if he still can't draw he can fake it pretty well. As he assuredly can.)

In 1933, following a distinct lack of success as a freelance portrait sketcher at $1 per, Chuck Jones made the move of his life, to Leon Schlesinger Productions. Schlesinger had previously headed something called Pacific Art and Title, the principal product of which was the dialogue cards on which si-

lent films depended. (The heroine's lips move; then a card: "Oh, Henry . . . I hear . . . horses! ") A feature might use several dozen of those, or up to several hundred. But now that there were soundtracks, audiences could hear the heroine's voice, and the future for dialogue cards seemed bleak. Schlesinger, ever canny, saw how to cut his dependence on cards. He cooked up a three-way deal. He would back a couple of artists named Hugh Harman and Rudolph Ising, sometime Disney associates, to crank out a cartoon a month; the cartoons in turn he would market to Warner Bros., who would use them to promote songs from their feature films and their sheet-music companies. Thus cash would flow from the Warners to Schlesinger, who would pass no more than he had to back to Harman-Ising[4] while reserving the rest for necessities such as his yacht. Thus the Looney Tunes were born, and if you think that name carries an echo of Silly Symphonys you are right. The first Looney Tune, Sinkin' in the Bathtub, opened in a Warner-owned theater on Broadway, May 6, 1930. Its star was a li'l ol' black boy named Bosko, and finger-pointers should pause to recall the technical constraints of an era when all cartoon stars were apt to be black: Felix the Cat, Flip the Frog, yes, Mickey Mouse himself. A body you could fill in fast with a brush: that was a great help when you had to turn out hundreds upon hundreds of nigh-identical drawings. (Also, Bosko exploited the tradition of Al Jolson's blackface Jazz Singer, the pioneer talkie and a Warner Bros. production.) A year and a half later, Warners commissioned a second series, called Merrie Melodies. Those were conceived as one-shots, meant to market Warner songs, and

[4] And here it's routine to remark a lovely pairing of names.

for several years every Merrie Melodie was required to contain "at least one complete chorus of a Warner-owned tune."

Harman and Ising had ideas of quality that Leon Schlesinger didn't want to finance, and eventually they terminated the deal and took Bosko with them to MGM. That left Schlesinger owning, as Steve Schneider puts it, "the rights to the phrases 'Looney Tunes,' 'Merrie Melodies,' and 'That's all, folks!' but with no staff and no known characters."[5] To maintain the cash flow from Warners he hadn't a recourse save to get a staff together. He took over a building on the old Warner lot, lured Friz Freleng and Bob Clampett back from Harman-Ising, and picked up from Disney a few men experienced enough to start in as Production Supervisors, later called Directors. It was in the midst of that turmoil that Charles M. Jones joined the staff: a sometime cel-washer whose in-betweening hadn't made Ub Iwerks think he was worth keeping around. If on some pages of Chuck Amuck the self-deprecation sounds a trifle formulaic, still it's easy to imagine how Jones could have felt that the Warner cartoon operation acquired him, somehow, by mistake. He would stay with it for three productive decades.

Meanwhile, a wonderful plot twist. The second time Chuck Jones was terminated by the Iwerks enterprise (no, you don't need the details; Ub let him go, he sneaked back in, was fired again; it all happened in a few weeks of 1931)—well, the second firing was performed by Ub's secretary, Dorothy Webster, a sociology graduate (U. of Oregon). The ways of courtship being extraterrestial, in 1935 that same Dorothy Webster became Mrs. Charles M. Jones, and in 1937

[5] Steve Schneider, That's All Folks! (1988), p. 40.

mother to Linda Jones, who today, as Linda Jones Clough, runs two companies called Linda Jones Enterprises and Chuck Jones Enterprises, of which a principal activity is "producing, preserving and authenticating drawings and cels from my past, present and future, selling them through major art galleries in the United States." Dorothy Webster Jones, "friend, critic, writer, dance partner,[6] wonderful mother and grandmother," died in 1978. Five years later Chuck married Marian J. Dern, by profession a writer-photographer. He's been blissfully fortunate, twice.

It was Dorothy, he says, who somehow got him the job at Schlesinger's, back in the time of the breakaway from Harman-Ising. That put Chuck Jones in position to benefit by a major episode in animation history.

For in 1935, twenty-seven-year-old Fred ("Tex") Avery from Taylor, Texas, claiming to be a descendant of Judge Roy Bean, showed up at Schlesinger Productions. He said he'd directed two cartoons for Walter Lantz, though, Steve Schneider says, "no screen credits exist to that effect," and he somehow got put in charge of a new unit, staffed by men who weren't happy where they'd been. They included Chuck Jones, Bob Clampett, and "a terrific draftsman" named Bob ("Bobe") Cannon. About 1970 Avery was recalling them all as "tickled to death": "They wanted to get a 'new group' going, and 'we could do it' and 'let's make pictures.' It was very encouraging. . . . We worked every night. My gosh, nothing stopped us!" They were installed in a building of their own on the Warner lot—a white one-story bungalow,

[6] A 1954 square-dance book, Five Years of Sets in Order, is introduced by Chuck Jones.

quickly dubbed Termite Terrace once the new crew became aware of other live beings around. Shamus Culhane would remember from his stint there in '43 a place that "looked and stank like the hold of a slave ship," and Michael Maltese, long-time storyman, remembered a colleague who "tried to set fire to it once, just for the hell of it, just to see if it burned. And it wouldn't burn." And before long, in that unlikely place, Chuck Jones, sometime cel-washer and in-betweener and quondam apprentice to Grim Natwick, was animating for Tex Avery.

For reasons that will appear, he couldn't have had a better mentor at just that point in his career. Avery's sense of the animatable universe was formed in the decade when a dotted line from the eye of Felix the Cat could knock over a chipmunk, and he remained impervious to any claim that animation should strive for the Illusion of Life. So an Avery squirrel shakes a boxing glove lest it contain a (shudder!) horseshoe, whereupon a full-sized horse tumbles out head-first, its expression blissfully bland. Or an Avery bit-player with "one foot in the grave" hobbles up to the bar with (in Joe Adamson's words) "an entire plot of ground, an erected tombstone and a decorative tulip all cumbersomely attached to the end of his right leg."[7] That kind of gag takes a couple of seconds; Adamson is right to emphasize that what's funny isn't really the gag, after all rather simple-minded if you think about it, but "the brazen vividness of the presentation." The days of Felix were gone; animation's universe had since been enriched with color, sound, copious detail; its inhabitants were no longer inky blobs. Even Mickey Mouse, at one time a

[7] See Joe Adamson, Tex Avery: King of Cartoons (1975).

blackness with big white eyeballs and a pair of red shorts, had acquired, by the time of 1937's Brave Little Tailor, a jacket, a belt with a wallet, moreover a loop to carry scissors, all topped by a jaunty feathered hat with a turned-up brim. In so lavishly detailed a universe the mere dotted-line stare would need enhancing, perhaps with trumpets, raised curtains, centered spotlights.

All this craziness, Jones thought it worth emphasizing one morning, was dreamed up and executed by men in hats and ties and vests. "In those days, when you went to work you took off your coat, maybe, but very often you left your vest on. And if you loosened your tie, still you did not take it off." That describes men in uniform, so to speak.

Tex Avery stayed at Warners till Leon Schlesinger fired him in mid-1941 (their dispute was over the final forty feet of a film called The Heckling Hare ), and Chuck Jones animated or helped animate seven Avery pictures, 1936–37. It's arguable that the truly mad and memorable Avery emerged at MGM, 1942–55. To that period belong, for example, the films, notably Little Rural Riding Hood, that feature a lecherous wolf (essentially, the Disney wolf of 1933, but no longer obsessed with just food) and a disarmingly human redheaded nightclub singer. She is animated with the chastest imaginable sexiness,[8] and he, on first sighting her from his table, invariably finds some eleven different ways to fly madly apart. Sheer libido, you understand, nothing to remark on, the world needs to be kept populated; still, it's hard to forget his eyes popping out two yards on taut strings, or his feet astomp on his head, or his body breaking up into five pieces which by some miraculous law snap back together.

[8] And no rotoscopes were used, Joe Adamson assures us; nor was anyone so much as peeking at live-action footage.

As to what all this has to do with Chuck Jones, who as we've said animated for Avery during just two years, after which he was promoted to Supervisor (i.e., Director) on his own; well, it's perfectly true that Avery's style of boundless exaggeration was never Jones's. What Tex Avery did establish—though for Chuck Jones the lesson took time to stick—was simply the autonomy of the Director's created world. The world of the transcendent Jones cartoons—think of One Froggy Evening or What's Opera, Doc? —has no firm connections with any world outside itself. Humans, such as dicker with talent agents or use their life savings to hire theaters, coexist with a green frog who wears a top hat and sings "Hello, My Baby" and can also walk a tightrope. A pig who sings Wagner soon joins a rabbit who can play a ballerina in drag and can also slide down a white horse with the best of circus stars, in what the rabbit announces has been not opera but send-up ("What did you expect—a happy ending?"). It doesn't seem too much to say that Tex Avery's presence—though none of his major films got made at Warners—underlaid the great period when Warner cartoons, to the general bemusement of Warner brass, paced the cartoon industry, and also fostered Chuck Jones. Jones needed Avery's example. But Tex Avery had to get clear of Warners to flourish, and Jones could not have flourished anywhere else.

For a fix on this complicated theme, consider the role of Walt Disney Enterprises in a world where rival studios, and notably Warners, seemed to have no firm objective save not to be lavish with money. At WDE they came to know what they were after, and it wasn't what Avery was after, nor for that matter what the post-Avery Warners valued. What they

were after chez Disney was the look of expensive perfection. Now define Perfection. (Clearing of executives' throats . . .)

Cartoons were for kids—right? Or so Walt Disney was thinking by about 1935. Thus at Burbank they made Silly Symphonys that would have been far better had they been sillier—a langorous Wynken, Blynken and Nod, for example, as cutey-cute cute as the wooden shoe of a starship they rode through the sky, dangling candy-cane hooks to catch stars. Mothers were meant to recall how their mothers had read Eugene Field's verses to them; were meant also to conclude that their own children would of course love what they themselves seemed to remember loving. Meanwhile the animators gave more and more attention to getting details like the swirl of waves Exactly Right. They'd even check their drawn efforts against live-action footage. When Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, two of Disney's "Nine Old Men," subtitled their big 1981 Disney Animation book "The Illusion of Life," they disclosed more than they perhaps meant to. Somehow, some time a little after the transcendent Three Little Pigs, the perfection Art seeks had been redefined at Disney. Artists were to try for something miscalled Realism, described at one point in the Thomas-Johnston book as "that rich look of a first-class illustration," which hints at, oh, gallery-quality Norman Rockwell.

Warner Bros. animation at its finest had no truck with any such Illusion of Life. But that would be later. At Warner Bros. in the 1930s, Chuck Jones says, Disney's doings were regarded with absolute awe, and by no one more than by Jones himself, who, once he became a director, worked through a long sticky period of Disney-worship. (Obvious how Chouinard training might encourage that. Attach a hand to an arm?

Ah, one more thing I know exactly how to do.) Early in the second half-century since Tom Thumb in Trouble (1940) was, as they say, "released," a viewer of that landmark film is hard put to distinguish admiration from embarrassment. "Supervision" is "by Charles M. Jones"; also credited is one animator, Robert Cannon, the "terrific draftsman" who'd been part of Avery's inheritance at Warners and who clearly had a fine grasp of how to portray the undistorted human form. It's, yes, beautifully drawn; and if you like a nice sentimental story, that's present too, thanks to storyman Rich Hogan (who would soon move to MGM and for years provide Tex Avery with his most Averyesque ideas, dancing redheads, exploding wolves.) But this story? To quote Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald's indispensable Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, "Once upon a time in the dark forest lived a woodchopper and his tiny son, Tom Thumb. Tom is so small that he can take a bath in his dad's cupped hands." A bird (we'll skip some details) saves Tom's life but Dad drives it away. Tom sets forth in a snowstorm to find it. And (quoting again), "Dad awakens and calls for his son. The little bird hears Dad's calls and flies to Tom, bringing him home. Dad, crying over the loss of his son, looks up to see Tom and the bird. That night, Tom is safely asleep in the pillow, the little bird nestled in Dad's beard." Treacle; lachrymose treacle, moreover. But it's all done with exemplary expertise. Astonishing, how the Warner folk could animate a big bearded human with slow but admirable realism, back when other studios (Disney, Fleischer) would prepare to do just that kind of thing by studying live-action footage such as Leon Schlesinger said he lacked the budget for.

Beck and Friedwald provide an interesting coda to their entry on Tom Thumb in Trouble . "Although the Warner car-

toon staff had tried to mimic Disney in the past, by 1940 they had pretty much given up that ambition in favor of the gag approach with which they would soon achieve popular success. This film is a deliberate, last-time effort to figure out the Disney formula. Disney would be used only as a source of satire in the future."

"The gag approach" . . . : That phrase is unnecessarily blank, implying as it does adolescent disrespect for something we haven't the skills or the budget to emulate. And "the Disney formula": that depended, surely, less on Disney animation than on Disney marketing. Walt's narcotics were safe for the kiddies; whereas it's been routinely objected from that day to this that the Warner formula is bad for them, incorporating as it does so much violence . My first afternoon with Chuck Jones, in Baltimore, back in 1974, was punctuated by a woman with a Social Conscience who charged him with promulgating violence, vide those awful "Road Runners." Having heard that, oh, say, 8,053 times, Chuck wasn't deterred. The Coyote, he pointed out, is the only one who gets battered; but never, ever, does the Coyote find himself in a situation he didn't set up, personally and in detail. (Unmollified, Ms. Conscience, a lighter-into, next lit into the hors d'oeuvres.)

We're walking a delicate line. On the one hand, Jones is allegedly the maestro of mindless violence. (Wrong.) On the other hand, he's animation's stickiest sentimentalist. (Also Not Right, though Tex Avery is quoted as saying "That was almost a Jones" about a cartoon of his own he thought was too sentimental.) What Jones did was struggle clear of the treacly Disneyesque. (Feed the Kitty —treacly? No. Though it does offer a moment when audiences have been known to weep.) The great Jones films are neither sentimental nor vio-

lent, though their care for their characters could lead you to think the former while their sheer speed nudges you to the latter. Bully for Bugs —sentimental? Nonsense. Violent? Also nonsense, despite everything its script inflicts on a bull we surely never think is real.

A bull we never think is real—that's a tricky concept. For if we don't think of a bull the cartoon gets trivial, whereas thinking of a beast in pain expels us from the cartoon world. But that is not a beast, therefore not in pain; it's a wondrous arrangement of lines and color and movement. That's something true of all animation, and it's remarkable how much oftener the question comes up chez Jones than, say, chez Avery. Jones differs from Avery in working somewhere close to the mysterious zone where we viewers connect pen-and-ink artifice with the world we inhabit. He'd not claim ownership there, perhaps not even understanding. Still, no other animator seems to have worked in that domain with so much confidence.

In 1942, aged 30, he directed a cartoon which (he says) was "the first Chuck Jones," that is, the first film to bear what could later be recognized as his unmistakable imprint. That was The Dover Boys, a wondrous romp with Tom, Dick and Larry, three jolly chaps enrolled at Pimento University ("Good ole P.U.") and chastely enamored, all three, of the steadfast Dora Standpipe. The date, judging by the one auto we get to see, is ch, about 1910, so Tom, Dick and Larry get around by pedaling (one tandem, one penny-farthing, one trike). How Dora gets around is less clear. Her gown touches the ground and she seems to have no feet, but she's a dynamic wonder as she glides down stairs and wobbles like a bowling pin at each landing. Her resemblance to a bowling

pin doesn't deter a dire fellow named Dan Backslide, who hangs out in pool-halls and, yes, covets chaste Dora. Pool-halls, we know about those; in one wonderful shot our three heroes and Dora glide by such a place on bikes, each averting a horrified gaze. Then—well, you have to see it. There's not a false move, a false moment. Movement is crisp, and stylized in a way that would be seeming normal perhaps twenty years later.[9] And, weirdest of all the weird details in The Dover Boys, a queer little bald bearded fellow in a swimsuit who has more than once caught our attention by intermittent hops across

[9] In his memoir Talking Animals and Other People (1986), the great animator Shamus Culhane has John Hubley saying (p. 240) that The Dover Boys was a prime inspiration for the UPA cartoons of the 1950s, fabled for their "style."

the bottom of the screen (one-two-three-HOP! ) turns out to be the final winner of Dora Standpipe's heart as he and she hop away into a satisfyingly clichéd sunset. (Jones's Minah Bird, of whom more later, had that Hop mannerism too; and you'll recall Jones recalling a long-ago time when animators could get a laugh just by making a walking figure suddenly Hop. He's a stubborn clinger, is Jones, to what he perceives as validated conventions.)

A strange film, The Dover Boys, a clean break with Disneyfication and perfectly self-contained as few Warner cartoons could think of being back in '42. That contentment in being self-contained is one of its Chuck Jones trademarks. So is its restriction of Animation's whole repertoire to a few formulaic devices. You don't lose when you restrict, no, you gain. That's true of all Art, and a maxim Animation was too long a time validating. Out in Burbank the Disney folk were never sure that there was any limit between what they were doing and utter hang-it-all Realism. (T. S. Eliot, whom they didn't read, had supplied a theme for pondering a decade previously. What had killed off a theater the glory of which was Shakespeare, had been, Eliot postulated, its limitless appetite for Realism.)

Now about the Minah Bird. It first turns up as early as 1939, in a film called Little Lion Hunter . It's still present in several successors, till as late as 1950 (Caveman Inki ). In each film Inki, a little black fellow with a spear, seems to be the only human inhabitant of a jungle so stylized its white hills resemble molars. Armed solely with a spear, he hunts such critters as a parrot, a giraffe, a butterfly. (A spear, for a butterfly! Much isn't adding up.) Through Inki's universe there leaps, occasionally, the Minah Bird. It's black, and intent on nobody knows what, and it has that mannerism of hopping

on every third step, guided by the rhythm of Mendelssohn's Fingal's Cave overture. Every time it appears, normal causation is suspended; but if you think it's Inki's good angel you're deceived, since Inki does tend to benefit but never wholly. Thus at the end of Inki and the Minah Bird (1943) the lion is chasing Inki into the sunset, but the Minah Bird has acquired the lion's false teeth, and what danger a toothless lion is likely to be is something on which we may speculate. (That lion, by the way, is a wonder, animated by Shamus Culhane, the same who had marched Disney's Seven Dwarfs singing "Heigh Ho!" Some eight years before Inki, Culhane attended classes taught by the same teacher Jones is proud to credit, Don Graham. And at the zoo to which Graham took the class once a month, Culhane recalls being captivated by "a mangy-looking lion," said to have once been the model for the MGM titles, but by then "the sorriest King of Beasts I ever saw."[10] Drawings he made there supplied "the best poses" for Inki's lion. And Chuck Jones was especially pleased because a lion's hind legs, for once, got animated correctly.)

Jones claims not to understand his Minah Bird films. He also claims that they drove Walt Disney to distraction. "Make something as funny as that," Walt ordered his staff, and nobody could because nobody could grasp the formula. Nor could Jones, though he made at least five of them. That such strange enigmatic things ever achieved release is a mark of the Schlesinger studio in those days. Perhaps Leon's yacht explains something. "He was a very vulgar, peculiar, naive, lovely man," Jones once recalled, and that cascade of adjectives signals something unusual. "He once bought a yacht

[10] See Talking Animals and Other People, pp. 134 and 246–51.

from Richard Arlen and called it the 'Merrie Melodie,' with a little dinghy on the back that he called 'Looney Tunes.' One day I said, 'Mr. Schlesinger, when are you going to take us out on your yacht?' And he replied, 'I don't want any poor people on my boat.' But, of course, he was the reason we were poor."[11] And their poverty helps explain what we'd best be grateful for now, Leon's scant attention to their doings on the Terrace.

[11] Steve Schneider, That's All Folks! (1988), p. 38.

Life in a Comma-Factory

Jack and Harry, the take-charge Warner brothers, were notorious for interfering with anything they thought they understood. Their malaise pertained to the profit margin on features, which tended to be thin and was easily violated by directors whose pretensions to "artistry" kept them fussing with angles and retakes while the clock ticked. Two minutes and a half of usable footage each day was a feature director's normal quota. Back before he bolted Warners for MGM (and The Wizard of Oz ), Mervyn LeRoy was valued for routinely doubling that.

Resources were dispensed as through an eye-dropper. The director of Emile Zola wanted a crowd of 400. Allotted just 200, he lowered the lighting to "rainy day" level and deployed 400 umbrellas, only half of which had people under them. The director of The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex was ordered not to let any sets be dismantled since their reuse in the upcoming Sea Hawk would "save a fortune."

Jack Warner, whom Fortune in 1937 called "a jocose penny-watcher,"[1] saw to it that Warner Bros. avoided co-starred features because those would mean paying two stars. In the pre-war decade when the house style was established, the Warners tended to concentrate on pictures one male actor—Paul Muni, Jimmy Cagney—could dominate. They preferred, too, darkness and fog, because sets you couldn't see didn't need constructing. An in-house memo of 1937—not from a Warner but in the Warner spirit—instructs a director not to "pump too much fog into the foreground in gusts." Artistic criteria? Fiscal? Uncertain. Around the same time, Jack Warner's attention was being mesmerized by the tint of Errol Flynn's mustache: "The mustache certainly looks good. I am sure that the mustache is the thing for this picture." (That was Lives of a Bengal Lancer .)

Mustaches after all came cheap, and "cut-rate dreaming" was the Fortune writer's phrase for the whole operation. He cited Harry Warner: "Listen, a picture, all it is is an expensive dream. Well, it's just as easy to dream for $700,000 as for $1,500,000."[2] (Meanwhile, over at the Disney dream-factory, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was running up a tab—for a venture in animation!—of more than the million-and-a-half that gave Harry Warner shudders at night.)

[1] Someone less tactful once said Jack's suits had rubber pockets so he could steal soup.

[2] In 1937 dollars, of course. For an early-90s equivalent try multiplying by about 10. And that's just to adjust for inflation. Today's overhead—color, special effects, union scale boosts—costs easily another fivefold. So in the 1990s animated features were enjoying a comeback after decades of eclipse. However labor-intensive, they were actually cheaper to make than damn-the-budget live action.

Warners, by the early 1940s, owned 17,000 movie-houses in 7,500 towns, a total of 10,500,000 paying seats. Keep filling those seats, was the word that went to directors. And every fortnight, preferably oftener, went the word to Termite Terrace, We need one snappy new cartoon.

Yet, whatever horror stories linger in veterans' memories, Termite Terrace, unlike any other Warner Bros. division, ran with a singular minimum of interference. So complex was its operation, you might have expected an accountant's face at every transom. But no. And why not?

For one thing, the Warners didn't own the place till as late as 1944. They simply bought its product from Leon Schlesinger Productions. And after they took over, and installed Eddie Selzer as boss, though Eddie was a bore and a nuisance the Brothers seemingly weren't. Jack Warner's recorded interferences, though catastrophic, were but two: when he closed the studio briefly in 1953, then for good in 1963. Beyond that, the indifference does seem out of character. But look, the cartoon division wasn't important. That may well be an explanation.

For examine something else that's unimportant. I press a key. A comma appears on my computer screen. Now how did that happen?

Even at its simplest—on an IBM desktop machine—the sequence is unbelievably intricate. That key closes its unique combination of circuits. Next, a keyboard microchip, prodded to do something, wakes up. Checking the active circuits against a list, it emits a "Scan Code"—comma! The code goes to an Interrupt Service Routine, which is contained in a Device Driver, which has seven subsections you don't want to hear about, all essential to handling that tiny Scan Code. Like

phone girls and file clerks guarding an Executive Producer, they cater to the whims of the Boss Microchip, the Central Processing Unit. It's possible, for instance, that the CPU may have other things on its mind which had better not be violated. So, clear its desk! And fourteen separate items, which may or may not be important (but you never know), get squirreled to safety by a head flunky, just to free high-level attention for the incoming comma. And now (music up!) the Scan Code can be ceremoniously placed in a sacred area called the Data Buffer. Only after that does the CPU get its fourteen items back so it can go on with its deliberations if it has any. What happens next depends on whether, when I pushed that key, I was running a program or just doodling. If a program, well, it's still more complicated. . . . But the Data Buffer is retentive, and eventually (we're counting in milliseconds) a little comma does emerge from its entrails to show up on the screen, while thousands cheer.

The sequencing of events at Termite Terrace, to generate a cartoon every ten to fourteen days, was at least as convoluted as that. The point of the parallel is that no one cares how a comma hits the screen so long as it gets there. Fast. And no one at Warners seems to have cared, either, how a cartoon got to 17,000 screens, so long as it reached them on schedule. Life at Termite Terrace was, blessedly, Life in a Comma-Factory. The product? Merely a punctuation mark, just before the two-reeler that came just before the feature. And the moral is, What Freedom!

By about 1949, the beginning of the Chuck Jones Golden Era, several economies had long been installed. Each, in the Warner spirit, ought to have been a hobble. At Termite Terrace each was a liberation.

First, how much footage? Cartoons ran about 7 minutes.

At 420 seconds, that's 10,080 frames, or 5,040 drawings when we shoot each of them twice. A lot of drawings. Even at starvation wages, a lot of money: say $30,000 per Looney Tune: say three-quarters of a million bucks annually, plus change.

That's about the cost of one middling 90-minute feature; and for about twice the delivered footage per year! Foot for foot, Termite Terrace might seem a bargain.

Still, it's features, not cartoons, that draw the crowds. Cartoons being trivial, something seemed out of balance. Seven minutes per product: might exhibitors stand for less? It turned out they'd regard five minutes as short weight. The compromise was six; six minutes plus or minus a grotesquely specified two-thirds of a second. Standardization #1: Scale as fixed as the size of a window at Chartres .

Next, we've got to get this place organized. Every two weeks, that's twenty-six a year; three directors can handle that, each responsible for about ten films. From conception to delivery, a cartoon might take twelve months or more. So a director at any time had ten or more going at once, the newest just being talked out, the oldest acquiring its sound track, perhaps eight others in stages of gestation. Thus, Standardization #2: The picture belongs to the director .

That system was firmly in place by 1944, when the Warners bought Schlesinger out. By 1947 the three directors were Isadore (Friz) Freleng, Charles Martin (Chuck) Jones, Robert (Bob) McKimson. And the control of each, over each project credited to him, was, finally, absolute. Termite Terrace being the only shop where so rigid a system was installed to meet so exacting a schedule, the Warner Bros. cartoon division was likely the only place in all of cinedom to which the auteur theory can be rigidly applied.

Auteur is what the French call an author, a creator; and auteur theory was something film historian Andrew Sarris began promoting about 1968, to celebrate, as his gadfly Thomas Schatz puts it, "the director as the sole purveyor of Film Art in an industry overrun with hacks and profitmongers." Schatz calls that "adolescent romanticism"; his The Genius of the System (1988) is persuasive about hacks and profitmongers not sabotaging good films, but imposing the limits that made good films possible. For art is largely an affair of limits. When the Medici asked for a panel of certain dimensions to adorn, as it were, their summer cottage, that was when they got Botticelli's Venus .

Schatz, though, nowhere mentions the cartoon operations maintained by the studio systems he surveys: a pity, since the reason we have such a book as Steve Schneider's That's All Folks! (subtitled, The Art of Warner Bros. Animation ) is that the Warner system, albeit by inadvertence, guaranteed a niche where miracles could happen: where "Art," an overused word, is fitfully applicable.

And the time has come to demystify the Termite Terrace usage of "Director." The DeMille image—bawling through a megaphone at actors—is inapplicable; there was no Bugs Bunny to bawl at, save as numerous pencils created him at the rate of twelve drawings per second (every frame shot twice, remember?) Over at Disney, to say that Art Babbitt supervised one of Fantasia' s highest points, the Chinese Mushroom Dance, or that Shamus Culhane marched the Seven Dwarfs off, Heigh Ho, is to say we don't know what we're saying, since (as Jones remarks) the head animator of a Disney sequence worked with a sequence director, who in turn had the privilege of consulting the film director, who might consult

Walt. Also, Walt might just drop in. So we can't tell when or how often Walt may have been involved. Walt, a mediocre animator but a storyman of genius, had the last word on every detail and would order things redone from scratch. At Warners they didn't enjoy the luxury of redoing. Just get it the way it's going to be, the first time round.

Hence the Director's necessary iron control. Briefly: he confabbed with the storymen, he worked with the soundmen; he knew the strengths of his key Animators; he knew their In-betweeners. He drew "Model Sheets" to help numerous hands keep his characters unified. (Jones's Bugs isn't Freleng's Bugs.) And his crucial role came down to (1) making 300 or up to 500 key drawings to guide the Animators; (2) making frame-by-frame plans called Exposure Sheets that would bring the thing out exactly on the last second (360 seconds, that's 4,320 drawn frames, give or take a half-dozen.) With ten or twelve projects under way on any morning, the director might be shown one of up to 50,000 drawings, by some underling in a jam. Unflappable, he'd recognize its place in which sequence of which film. Such talent was rare, the knack for those key drawings rarer still, command of the Exposure Sheets likely rarest of all. Great as the best Warner Animators were, it's no wonder so few became Directors.

Chuck Jones tended to make more key drawings than the other directors. They show how a sequence of movement is to begin and end. He's explicit about their role. The Animator wasn't to trace them. The Animator was to use them as guides, defining a flurry of drawings he could feel happy with. "Ken Harris will change everything. He'll use an idea, but the action will flow through and go beyond it. Or he may forget it completely. But his animation will indicate what I

had in mind." One facet of directing is prodding the very best out of such a rare talent as Harris's.

(And the In-betweeners? A hack In-betweener, as the art had evolved by the era we're speaking of, might as well be computerized—something that's still being worked on—but a good one, moving toward Animator status, understood how between key frames different parts of a creature shift different weights at different velocities. As the foot comes to rest, the body still lurches forward. Great animators insist that there is no such thing as an exact in-between, equidistant between extremes. So cherish your In-betweeners, who generate possibly 80 percent of the frames that end up, inked and painted, on-screen.)

The Animators also kept a wary eye on the director's other principal offering, the Exposure Sheet. It's a printed strip of sturdy paper, about nine inches wide by twenty long, ruled with a horizontal line for every frame, plus emphatic lines for feet of film, seconds of time. Every drawing we're going to generate gets accounted for there, every footstep, drumbeat, syllable of dialogue. No live-action auteur could have dreamed of such command. And each sheet takes care of 6 feet. So 540 feet of film—6 minutes—means 90 of those sheets, a thickish stack.

Bugs Bunny is walking 12 paces per foot (at 12 drawn frames per foot, that's a second per pace). Down the left-hand column, "Action," an X at every 12th line means a foot touching ground; key drawings will guide the Animator there. And Bugs is saying (what else?) "What's up, Doc?" In the next column ("Dialog"), at frame 8, the "Wh" commences (his mouth starts to open); by frame 16 his mouth is wide open on the "ah"; by frame 22 it's closed on the "ts." That kind of thing is plotted on the Exposure Sheet for every syllable of

dialogue; the mouth-closing "c" that ends "Doc" coincides with frame 52 (drawing 26). The rule is that sound can escape the mouth only on vowels, consonants determining the beginning and finish of the vowel sound. On M, F, P, the mouth closes. On T, N, L, the tongue goes up against the roof of the mouth. Such are the instants the director needs to locate for the Animator, so the timing of dialogue will flow aright. Between such key points, a competent Animator is on his own. At Warners they had some very competent Animators.

Jones can tell, he says, if timing is off by one frame. That's less than an eyeblink. Prescriptions could be unbelievably precise. When the Coyote dropped off the cliff, as he did repeatedly, it would take, says Jones, "Eighteen frames for him to fall into the distance and disappear, then fourteen frames later he would hit. It seemed to me that thirteen frames didn't work in terms of humor, and neither did fifteen frames. Fourteen frames got a laugh." And from the Exposure Sheet all hands—Animators, In-betweeners, Sound Crew—knew exactly what was required.

But there's more. In addition to a wide rightmost block headed "Camera Instructions," where you'd specify, say, panning the next forty frames across a wide background, the Exposure Sheet has six more numbered columns. Those are for any special high-jinks with cels. Because if Elmer Fudd holds still and just moves his lips to say "Wabbit season," the main Elmer-cell, to save a lot of redrawing, can just be overlaid with a sequence of mouth-cels. You might find yourself repeating that principle for several layers, trusting someone in Ink-and-Paint to remember that colors change when they're perceived down through overlaid cels. To keep Elmer's red jacket Elmer-red beneath three cels meant calling for a richer red with a special number.

And let's attend anew to one phrase: "to save a lot of redrawing." If that began as a concession to the cash-register, it soon became a principle of art. Recall Gertie the Dinosaur, of pre-cel days, when endless retracing made everything shimmer and wobble. But cels let us think of shimmer and wobble as special effects. Special too is the non-wobbling rigidity of drawings simply reused. So as animation evolved post-cel, just what changes now becomes what matters, to offset what—for two seconds (eternity!)—isn't changing. That gets emphasis Animators can get in no other way: think of Elmer's obsessed rigidity as he listens for wabbits. Maybe eyes blink (overlaid cels); maybe they don't. Selective redrawing became, especially at Warners, one of animation's subtlest modes of expression. What the Termite Terrace zanies found in it resembles Milton's discovery, circa 1660, of the range of effects blank verse on a printed page could extract from a mid-line pause: Line visible, stable; Pause audible, fluctuant.

What that does is throw emphasis back on the key drawings: the moments of stasis, of expressive posture, which might even stay frozen for several frames. At Disney the emphasis was on fluent movement; at Warners, the prolific Friz Freleng's habit tended that way too. It was during stretches of dialogue that Disney's custom was to introduce punctuating pauses, where they can be subtly irritating simply because they're meaningless. But Chuck Jones cherished the summarizing key pose, and his Exposure Sheets were apt to instruct that it be held: held an exact number of frames. And of such was his kingdom of heaven.

Generally, as a cost-saver, the largest number of characters visible in one shot was two.[3] Thus in the Hunting Trilogy of 1951–53 (Rabbit Fire; Rabbit Seasoning; Duck! Rabbit! Duck! ), though each film revolved around three characters—Elmer Fudd, mighty hunter; Bugs Bunny, cool evader; Daffy Duck, hysterical victim—the economical strategy was to establish their relationship, then resort to "one-shots" and "two-shots." And the two-shots could economize too, by just "looking at one of the characters" without troubling to animate him. Thus, "Daffy would say, 'Oh, no you don't,' and Bugs would just stand there waiting. Because that is what he would do anyway." Chuck Jones guesses that in a given picture, perhaps 60 percent of the shots use just one character. "We soon learned that it was not just to cut down on the number of separately animated cels, but to emphasize the power of a strongly-drawn non-talker as a foil for the voluble. It became what I call Motivated Camera. Having established the rhythm of the relationship between two characters, I could go to one for something to say, go to the other for the reaction. We learned to do it pretty well." Indeed they did. Something from the Hunting Trilogy tends to show up on most lists of Warner cartoon highlights.

An economic necessity, true; but there's no denying how, here as so often, necessity "resulted in far better picture-making."

And for another interesting reason: "It also resulted in our cutting all the fat out of our dialogue. I mean, if you have something to say, say it. You know."

[3] By contrast, there are scenes in Snow White where as many as thirty animals are all differently busied. But cost wasn't governing such scenes.

And to show that I knew, I volunteered, "Get the meaning across and then stop."[4]

And Jones, good liberal that he is, responded with "Woodrow Wilson, I think it was, who said, If you're shooting, do not use a shotgun, use a rifle with a single bullet; likewise when you're writing." That's the one time I've heard an ex-president of Princeton cited as a monitor of verbal style.

One can hardly overestimate the extent to which the Warner Cartoon Style stemmed from the need to minimize costs. "If I had suggested doing 101 Dalmatians everyone would have thought I was crazy. Even a dog named Spot, with one spot, would have been out of the question. What costs in animation isn't colorful and detailed backgrounds; those are its cheapest elements, because a short with maybe 65 backgrounds will still need 5,000 drawings. It's the details in those drawings that cost. When Disney made 101 Dalmatians, the animators didn't animate dalmatians, they animated white dogs. Somebody else came along and put the spots on. O. Henry said that the most exacting (make that 'exasperating') job in the world was that of foreman to a gang of invisible weavers. I'm not so sure."

And they kept the spots consistent on each dog?

"No, they animated just eight different dogs. That was the first time they used a computer, for the few scenes when you see the whole pack of puppies at once. It decided how to randomize eight dogs repeatedly so that 101 of them running at you would look like 101 dogs rather than a dozen-plus sets of eight."

[4] From Ezra Pound's Cantos, where the sense is attributed to Confucius.

Limited animation

Full animation

Ramifications of the need to economize are not, alas, infallibly benign. Saturday morning television would bring about what the film critic Leonard Maltin calls the Muzak of animation.[5] Chuck Jones once summed up what he calls it in one