Preferred Citation: Mally, Lynn. Culture of the Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6m3nb4b2/

| Culture of the FutureThe Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary RussiaLynn MallyUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1990 The Regents of the University of California |

To my mother

Preferred Citation: Mally, Lynn. Culture of the Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6m3nb4b2/

To my mother

Acknowledgments

Many friends and colleagues have helped to make this book better. Lidiia Alekseevna Pinegina, my academic adviser in the Soviet Union, shared her ideas and research with me; her scholarly generosity was a model of glasnost ' before its time. Jutta Scherrer's continuing interest in my work inspired me to see this book to its conclusion. Kendall Bailes, Jeffrey Brooks, and Richard Stites carefully read the dissertation from which this book emerged; their encouragement and criticism led me to rethink many parts of the manuscript. Peter Kenez and Richard Sakwa gave incisive responses to several chapters. I was very fortunate to have a wonderful dissertation committee whose assistance continued long after I received my degree. Nicholas Riasanovsky offered many useful suggestions for turning the thesis into a book. Victoria Bonnell approached both the dissertation and the manuscript with a keen critical eye; her comments have greatly improved the final product. Most of all, I would like to thank Reginald Zelnik for his friendship and tireless commitment to his former students. His meticulous reading of the manuscript enriched this book in both form and substance.

I am indebted to the following institutions: the International Research Exchanges Board, which funded a research trip to Moscow; Temple University, for providing me with a summer stipend; and the American Philosophical Society, for research funding. I was fortunate to receive permission to

work in Soviet archives when that was still an unusual occurrence, and the staff of the Central State Archive of Literature and Art deserves credit for its cheerful assistance. Both Edward Kasinec, of the New York Public Library, and Hilja Kukk, of the Hoover Institution for War, Revolution, and Peace, went far out of their way to help me.

Sheila Levine of the University of California Press has been a model editor, and I wish to thank her for her constant enthusiasm for this project. The Indiana University Press has kindly allowed me to reprint parts of my article "Intellectuals in the Proletkult: Problems of Authority and Expertise," forthcoming in Party , State , and Society in the Russian Civil War , edited by Diane Koenker, William G. Rosenberg, and Ronald Grigor Suny.

At every step along the way my large extended family—siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles—provided emotional support and comic relief. Special thanks go to my parents, Helen and Samuel Urton, who encouraged me to pursue what was for them an unusual career. In the last stages of revisions my daughter Nora was born and did much to keep my work in perspective by showing only an occasional interest in the flashing lights on the computer screen. Robert Moeller was part of this project from beginning to end and read more drafts of this book than either of us can recall. His contributions as a historian, critic, and cook were considerable; as a friend, they were even greater.

Note on Dates and Transliteration

Because this book spans the pre- and postrevolutionary years, I have employed two dating systems. All dates before February 1918 are given according to the Old Style (Julian) calendar. After that time they follow the New Style (Gregorian) calendar.

I have used a modified Library of Congress transliteration system, with two exceptions. Well-known names, such as Eisenstein, appear here in their generally accepted Anglicized forms. In the text, but not in Russian references in the notes, I have also omitted the soft sign: thus Proletkul't becomes Proletkult.

In archival references I have used standard abbreviations for Russian terms: op. for opis ', d. for delo , 1. for list , and ob. for oborot .

Introduction

In October 1919 Petrograd, home of the Russian Revolution, was a devastated city. Severe food shortages had prompted the exodus of large parts of the population. To make a difficult situation even worse, the White Army general N. N. Iudenich began an assault on the city, bringing his armies almost to the suburbs. Yet this emergency did not stop a respected theater director from holding a lecture series on the history of art in an organization called the Proletkult, even though the audience changed constantly because of military mobilizations. At the same time, the Proletkult theater was preparing a performance for the second anniversary of the revolution, a play written by a Red Army soldier who had helped to storm the Winter Palace.[1]

This dramatic mix of political insecurity, physical privation, and cultural creation was not unusual in revolutionary Russia. Similar episodes can easily be found in contemporary journals and newspapers and in the memoirs of cultural activists. They illustrate quite graphically that the proponents of revolution were not willing to limit their goals to the establishment of a new political and economic order. They hoped to create a new cultural order as well.

[1] "Nasha kul'tura: Petrogradskii Proletkul't," Griadushchee , no. 7/8 (1919), p. 31. The lecturer was E. P. Karpov, former director of the Aleksandrinskii Theater. The play, Za krasnye sovety , was written by Pavel Arskii, one of the leaders of the Petrograd Proletkult.

Of course culture is an ambiguous term with many different meanings, ranging from the shared values and assumptions of an entire society to a simple synonym for fine art. Bolsheviks held no common definition, and Lenin himself used the word in strikingly different ways. Sometimes he meant the accumulated knowledge of educated elites, other times the civilized accomplishments of modern industrial societies, such as cleanliness and punctuality.[2] Together with his Bolshevik colleagues, he realized that cultural transformation was an integral part of the revolutionary process, but precisely what this meant for the new government was not immediately apparent. The blueprints for building a socialist culture were no clearer than those for a socialist polity.

Revolutions invariably challenge the cultural foundations of society, whether the participants consciously acknowledge this or not. Russian revolutionaries, like their Jacobin predecessors, welcomed the challenge. The transformation of Russian culture was the topic of wide-ranging debates in the early Soviet years. All the key elements were open to dispute—the meaning of culture, the revolutionaries' power to change culture, and the consequences that such change would have for the new regime.[3]

In these discussions there was very little common ground. Politicians, educators, and artists all concurred that cultural reform in their vast country, with its large illiterate population, was an enormous task. They also rejected a tradition that sharply divided the culture of the privileged elite from that of

[2] For Lenin's views on culture see V. V. Gorbunov, Lenin i sotsialisticheskaia kul'tura (Moscow, 1972); Zenovia A. Sochor, Revolution and Culture: The Bogdanov-Lenin Controversy (Ithaca, 1988), esp. chap. 5; and V. I. Lenin, V. I. Lenin o literature i iskusstve , 7th ed., ed. N. Krutikov (Moscow, 1986).

[3] The broad range of early Soviet views on cultural transformation is presented in Abbott Gleason, Peter Kenez, and Richard Stites, eds., Bolshevik Culture: Experiment and Order in the Russian Revolution (Bloomington, 1985); and William G. Rosenberg, ed., Bolshevik Visions: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia (Ann Arbor, 1984).

the lower classes. But unanimity ended here. State leaders could not even agree on the pace of change. While Anatolii Lunacharskii, the head of the People's Commissariat of Enlightenment, constantly lobbied for more funds and supplies, Leon Trotsky, Commissar of Defense, questioned the wisdom of devoting too many resources to cultural problems as long as the state was not politically and militarily secure.[4]

Indeed, cultural activists did not even share a common vision of the old culture they wished to leave behind, let alone of the new one they hoped to found. For the most cautious the heritage of the prerevolutionary intelligentsia was a positive and inspiring force. It was enough to pass on select aspects of art and learning to the masses in order to lay the foundations for the new society. The most radical rejected this conservative course of dissemination. They perceived the revolution as a clean break, a chance to discover new artistic images and new patterns of social interaction befitting the revolutionary age.

The passion and turmoil of these cultural debates are missing from most Soviet scholarship of the revolution. Soviet works portray the early years of the regime as the first stage of the Soviet Union's "cultural revolution," a long process through which the masses finally gained the education and cultural sophistication denied them by the old regime.[5] According to the standard scheme the Bolsheviks easily defeated their cultural enemies, defined as the intellectual foes of egalitarianism, on the one hand, and, on the other, extreme radicals who rejected the value of all inherited knowledge. The

[4] See James C. McClelland, "Utopianism versus Revolutionary Heroism in Bolshevik Policy: The Proletarian Culture Debate," Slavic Review , vol. 39, no. 3 (1980), pp. 403–25.

[5] For an overview of this scholarship see S. A. Andronov, ed., KPSS vo glare kul'turnoi revoliutsii v SSSR (Moscow, 1972); G. G. Karpov, O sovetskoi kul'ture i kul'turnoi revoliutsii SSSR (Moscow, 1954); M. P. Kim, ed., Kul'turnaia revoliutsiia v SSSR, 1917–1965 gg. (Moscow, 1967); and M. P. Kim, Velikii Oktiabr' i kul'turnaia revoliutsiia v SSSR (Moscow, 1967).

state then went on to establish the basis for a literate, culturally unified society, one in which the benefits of art and learning were equally available to all. This interpretation, with its basic theme of continuous progress, obscures the many conflicts among supporters of the new regime, conflicts over such important matters as the kind of education and entertainment that were best suited for the population. It also glosses over the more profound question of whether state-sponsored enlightenment allowed any active, creative role for the people themselves.

A major argument of this book is that the struggle to found a new cultural order was just as contentious as the efforts to change the political and economic foundations of Soviet society. I aim to show this by examining a mass movement that stood in the midst of cultural debates in the early Soviet years. The Proletkult, an acronym for "Proletarian cultural-educational organizations" (proletarskie kul'turno-prosvetitel'nye organizatsii ), first took shape in Petrograd in 1917, just a few days before the October Revolution. It began as a loose coalition of clubs, factory committees, workers' theaters, and educational societies devoted to the cultural needs of the working class. By 1918 it had expanded into a national movement with a much more ambitious purpose: to define a unique proletarian culture that would inform and inspire the new society.

The Proletkult was controversial first of all because its participants believed that rapid and radical cultural transformation was crucial to the survival of the revolution, a position they presented in loud and insistent terms. The organization's national leaders, and many of its local followers, demanded that culture, however defined, be given the same weight as politics and economics. Despite the military insecurity of the new regime, its political instability, and the rapid economic disintegration caused by the revolution and Civil War, the Proletkult's leaders wanted the state to place considerable resources at their disposal. Without due attention to culture,

they warned, the state's political and economic accomplishments would be built on very shaky ground.

The movement's participants not only underscored the importance of culture but also insisted on the primacy of a new culture that would express the values and principles of the victorious working class. Proletarian culture was an amorphous concept that signified many different things at once: the artistic creations and aspirations of workers; the expression of a revolutionary spirit; and, most broadly, the emergent ideology of the proletarian ruling class. Proletkultists themselves could not agree on common definitions, and the altercations in society at large over the value of prerevolutionary models in a revolutionary age also occurred within the movement. Meanwhile, the very notion of a specific class culture raised the ire of many critics, who questioned what such an adamantly proletarian organization could contribute to the creation of a classless society.

The expansive nature of the movement also placed it at the center of cultural debates. At its peak in 1920 the national leadership claimed some four hundred thousand members organized in three hundred branches distributed all over Soviet territory. Despite lack of funds and basic supplies, Proletkult participants founded a wide network of clubs, schools, workshops, choirs, theaters, and agitational troupes that performed on the fronts of the Civil War. The organization's ambitions were as broad as its following. Proletkultists were not just interested in proletarian artistic forms. They also wanted to create a proletarian morality and ethics. Child-rearing, family relations, and scientific education were all within their purview. Because of its far-reaching interests, the Proletkult inspired both admiration and animosity among other groups seeking cultural change, including the state's own educational agencies.

Perhaps most important, the Proletkult engendered controversy because it embodied a politically charged vision of the newly empowered Soviet proletariat. The most committed

members took the idea of the "dictatorship of the proletariat" quite literally and accorded all proletarian institutions a privileged position in the new society. They saw the working class as an autonomous, creative force that should be given free rein to express and develop its ideas. In the opinion of Proletkult leaders the Soviet government could not operate as a single-minded advocate for the proletariat because it had to consider the needs of other classes. Therefore, they wanted the Proletkult to be completely independent from state cultural institutions. By making this demand they were challenging the state's authority to stand above and mediate between social classes. Indeed, Proletkultists insisted on independence from the Communist Party as well, claiming that their movement, as the representative of the proletariat's cultural interests, was just as important as the party, the representative of its political concerns. These bold demands for autonomy finally led to confrontation. By the end of the Civil War the Communist Party had taken away the Proletkult's independence and placed the organization under the tutelage of the state's cultural bureaucracy.

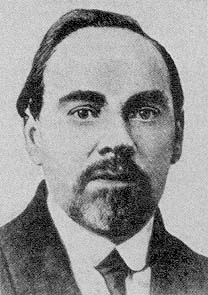

The Proletkult's clashes with the Communist Party have dominated historical scholarship both in the West and in the Soviet Union, earning it a reputation as an oppositional movement. This idea is reinforced by the fact that the Proletkult's most polemical principles—the primacy of culture and proletarian hegemony—can be traced to a group of left Bolsheviks who questioned Lenin's control of the party faction in the years between the Revolution of 1905 and the First World War. The most important of these leftists was Aleksandr Bogdanov, who produced a dazzling range of work on politics, economics, culture, and science before his death in 1928. Bogdanov believed that in order for a proletarian revolution to be successful, the working class needed cultural preparation. It had to devise its own class ideology and its own proletarian intelligentsia in order to take and wield power. Bogdanov's ideas on these matters outlined a distinct approach to revolutionary politics and tactics that was boldly at odds with Lenin's own.

Soviet scholarship highlights the conflicts between Lenin and Bogdanov over the proper course of political and cultural change. Basing themselves on Lenin's generally harsh criticisms of the movement, Soviet researchers have been overwhelmingly negative. V. V. Gorbunov, the most important Soviet specialist in this area, has deemed the Proletkult a separatist, sectarian, nihilistic, and revisionist organization.[6] His highly influential work presents the Proletkult as a dangerous challenge to the political power of the Communist Party and a threat to the social and intellectual foundations of the regime.

In recent years this negative view has been tempered as scholars have attempted to reclaim at least part of this mass movement as a positive force in Soviet cultural history.[7] For example, Soviet authors are willing to concede that local or-

[6] V. V. Gorbunov, "Bor'ba V. I. Lenina s separatistskimi ustremleniiami Proletkul'ta," Voprosy istorii KPSS , no. 1 (1958), pp. 29–40; idem, "Iz istorii bor'by Kommunisticheskoi partii s sektanstvom Proletkul'ta," in Ocherki po istorii sovetskoi nauki i kul'tury , ed. L. V. Koshman (Moscow, 1968), pp. 29–68; idem, "Iz istorii kul'turno-prosvetitel'noi deiatel'nosti Petrogradskikh bol'shevikov v period podgotovki Oktiabria," Voprosy istorii KPSS , no. 2 (1967), pp. 25–35; idem, "Kritika V. I. Leninym teorii Proletkul'ta ob otnoshenii k kul'turnomu naslediiu," Voprosy istorii KPSS , no. 5 (1968), pp. 83–93; and idem, V. I. Lenin i Proletkul't (Moscow, 1974).

[7] See M. P. Kim, "Istoricheskii opyt kul'turnoi revoliutsii v SSSR," Voprosy istorii , no. 1 (1968), pp. 109–22, esp. pp. 116–17; V. T. Ermakov, "Ideinaia bor'ba na kul'turnom fronte v perrye gody sovetskoi vlasti," Voprosy istorii , no. 11 (1971), pp. 16–31, esp. pp. 27–31; V. A. Razumov, "Rol' rabochego klassa v stroitel'stve sotsialisticheskoi kul'tury v nachale revoliutsii i v gody grazhdanskoi voiny, 1917–1920," in Rol' rabochego klassa v razvitii sotsialisticheskoi kul'tury , ed. M. P. Kim and V. P. Naumov (Moscow, 1967), pp. 8–70, esp. pp. 15–25; and I. S. Smirnov, "Leninskaia kontseptsiia kul'turnoi revoliutsii i kritika Proletkul'ta," in Istoricheskaia nauka i nekotorye problemy sovremennosti , ed. M. Ia. Gefter (Moscow, 1969), pp. 63–85. Even Gorbunov participates in this revisionism to some extent; see his "Oktiabr' i nachalo kul'turnoi revoliutsii na mestakh," in Velikii Oktiabr': Istoriia, istoriografiia, istochnovedenie , ed. Iu. A. Poliakov (Moscow, 1978), pp. 63–74.

ganizations sometimes served a positive role, especially when they ignored the narrow restrictions of proletarian culture and devoted themselves to basic educational work.[8] In one of the latest Soviet works, L. A. Pinegina goes even further in this revision. She insists that Lenin himself favored proletarian culture when it was defined as the cultural empowerment of the working class. In her view—still the exception rather than the rule—much of the Proletkult's activity was inspired by Lenin's vision, not Bogdanov's.[9]

Although differing in many ways from Soviet scholarship, Western studies of the Proletkult have also concentrated primarily on the conflict between Lenin and Bogdanov. The earliest works looked mainly at the implementation of proletarian culture in the arts, especially literature.[10] However, an increasing number of Western scholars have begun to study Bogdanov's voluminous writings in order to find an alternative to Lenin's vision of socialist transformation.[11] When the Proletkult has appeared in these works, it has been presented

[8] See, for example, T. A. Khavina, "Bor'ba Kommunisticheskoi partii za Proletkul't i rukovodstvo ego deiatel'nost'iu, 1917–1932 gg." (Candidate Dissertation, Leningrad State University, 1978), which covers the Petrograd/Leningrad Proletkult; N. A. Milonov, "O deiatel'nosti Tul'skogo Proletkul'ta," in Aktual'nye voprosy istorii literatury , ed. Z. I. Levinson, N. A. Milonov, and A. F. Sergeicheva (Tula, 1969), pp. 140–63; V. G. Puzyrev, "'Proletkul't' na Dal'nem Vostoke," in Iz istorii russkoi i zarubezhnoi literatury , ed. V. N. Kasatkina, T. T. Napolona, and P. A. Shchekotov (Saratoy, 1968), vol. 2, pp. 89–105; and V. L. Soskin and V. P. Butorin, "Proletkul't v Sibiri," in Problemy istorii sovetskoi Sibiri: Sbornik nauchnykh trudov , ed. A. S. Moskovskii (Novosibirsk, 1973), pp. 133–46.

[9] See L. A. Pinegina, "Organizatsii proletarskoi kul'tury 1920-kh godov i kul'turnoe nasledie," Voprosy istorii , no. 7 (1981), pp. 84–94; and idem, Sovetskii rabochii Mass i khudozhestvennaia kul'tura , 1917–1932 (Moscow, 1984).

[10] See Edward J. Brown, The Proletarian Episode in Russian Literature , 1928–1932 (New York, 1953); and Herman Ermolaev, Soviet Literary Theories , 1917–1934: The Genesis of Socialist Realism (Berkeley, 1963).

[11] For a sampling of this scholarship see Karl G. Ballestrem, "Lenin and Bogdanov," Studies in Soviet Thought , no. 9 (1969), pp.283ndash;310; John Biggart, "'Anti-Leninist Bolshevism': The Forward Group of the RSDRP," Canadian Slavonic Papers , vol. 23, no. 2 (1981), pp. 134–53; Loren R. Graham, "Bogdanov's Inner Message," in Red Star: The First Bolshevik Utopia , by Alexander Bogdanov, ed. Loren R. Graham and Richard Stites (Bloomington, 1984); Dietrich Grille, Lenins Rivale: Bogdanov und seine Philosophie (Cologne, 1966); Kenneth M. Jensen, Beyond Marx and Mach: Alexander Bogdanov's Philosophy of Living Experience (Dordrecht, 1978); Peter Scheibert, "Lenin, Bogdanov and the Concept of Proletarian Culture," in Lenin and Leninism , ed. Bernard Eissenstaat (Lexington, Mass., 1971); Jutta Scherrer, "Les écoles du parti de Capri et de Bologne: La formation de l'intelligentsia du parti," Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique , vol. 19 (1978), pp. 259–84; Sochor, Revolution and Culture ; S. V. Utechin, "Philosophy and Society: Alexander Bogdanov," in Revisionism: Essays on the History of Marxist Ideas , ed. Leopold Labedz (London, 1962); and Robert C. Williams, The Other Bolsheviks: Lenin and his Critics , 1904–1914 (Bloomington, 1985).

as "Bogdanov's" organization, the social consequence of his complex ideas about culture and society. The Proletkult thus becomes a symbol for Bogdanov; its size is used to show the popularity of his ideas and the possibility for a different outcome to the revolution. Even those works that focus directly on the Proletkult have made the interaction of Bogdanov's theory and the Proletkult's practice their central theme.[12]

One cannot omit the altercations between Lenin and Bogdanov from a serious history of the Proletkult. Their philosophical and political disputes informed its inception and prefigured its demise. But in my view those scholars who reduce the Proletkult organization to Bogdanov's movement give it a coherence and simplicity that it did not have. They

[12] The best of these works are by West German scholars. See Gabriele Gorzka, A. Bogdanov und der russische Proletkult: Theorie und Praxis einer sozialistischen Kulturrevolution (Frankfurt am Main, 1980); Peter Gorsen and Eberhard Knödler-Bunte, Proletkult: System einer proletarischen Kultur (Stuttgart, 1974), vol. 1, pp. 13–122; and Klaus-Dieter Seemann, "Der Versuch einer proletarischen Kulturrevolution in Russland, 1917–1922," Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas , vol. 9 (1961), pp. 179–222. One exception is Sheila Fitzpatrick's The Commissariat of Enlightenment: Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts under Lunacharsky , 1917–1921 (Cambridge, Eng., 1970), which examines the Proletkult's conflicts with the state bureaucracy.

also place it too easily within the broader framework of an anti-Leninist opposition, a generalization that seriously distorts many participants' intentions.

In this book I examine the Proletkult as a complicated social and cultural movement with many conflicting programs. Rather than focusing primarily on the ideas of the leadership, I investigate its heterogeneous social composition and its varied cultural practices. Using the archival records and publications of both local and central organizations, I try to show the complex interaction between official pronouncements and their implementation.[13] Such an approach illuminates the diversity of this organization and shows what it shared with many other early Soviet institutions. It also reveals what the Proletkult's successes and failures can tell about the revolutionary process in general.

As an independent mass cultural movement the Proletkult was a unique phenomenon in the early history of Soviet Russia. Many of the problems it faced, however, were not unusual. Like other groups claiming a proletarian identity, it struggled to discover how to gain predominance in a country where workers were a rather small minority. The official solutions the organization devised, such as trying to limit its membership to the most experienced workers or excluding nonproletarians from its ranks, were ultimately not very successful. The Proletkult was "proletarian" only in the broadest sense of the word; it drew its major support from the laboring population at large, from industrial workers and their children, from white-collar employees and artisans, and even from the peasantry.

Proletkult participants had enormous problems articulating a role for experts and intellectuals in the new society, another common dilemma. If one judged from its most radical pronouncements alone, the movement seemed to ad-

[13] This study makes extensive use of the archival holdings of the Proletkult, housed in the Central State Archive of Literature and Art in Moscow. The archive contains the records of the central organization as well as those of local circles, including membership rules, minutes of organizational meetings, and questionnaires about social composition and cultural practices.

vocate an extreme form of workers' control. Insofar as intellectuals were needed, they should be drawn from the working class. Some members went even further, opposing any form of social hierarchy whatever. As all Soviet institutions quickly discovered, however, the creation of a new intelligentsia inevitably required the participation of the old one. The Proletkult devised ingenious methods to limit nonproletarian artists, teachers, and experts to minor roles. But in the final analysis the influence of these class-alien elements was not so easy to curtail. Although the Proletkult gained a reputation for antiintellectualism, intellectuals were in fact key actors who helped to define the form and content of proletarian culture.

Like the leaders of all other Soviet institutions, central Proletkult planners fought hard to weld their many local branches into a cohesive national structure. Their plaintive calls for more information and more compliance from provincial chapters were echoed in countless other organizations, from the Communist Party to the government's cultural bureaucracy. The Proletkult's cardinal principles, autonomy and independent action (samostoiatel'nost ' and samodeiatel'nost '), encouraged local creativity. And yet the central organization struggled constantly and often unsuccessfully to implement its decisions at the local level. Despite its most valiant efforts, resolutions made at the center never dictated the practice of the organization as a whole.

In this study I try to avoid the simple dichotomy of theory versus practice, which pits the ideas of leaders like Bogdanov against the day-to-day work of local circles. Certainly there were fundamental beliefs that tied the Proletkult together. Members shared a commitment to proletarian hegemony, institutional autonomy, and the centrality of cultural change. But all these ideas were open to myriad interpretations. National leaders themselves did not always agree on the best way to nurture a new intelligentsia or to create a cohesive

movement. The malleability of the Proletkult's principles helped it to attract a large following.

Proletkultists passionately asserted the proletariat's central position in the new social order, but they did not agree on just what the proletariat was. For some it was synonymous with the industrial working class. They hoped the movement would find a following among the most culturally and politically advanced representatives of the factory labor force. For many others, not unlike the Populists and Socialist Revolutionaries of years gone by, the proletariat included all of the long-suffering Russian people, the narod . These advocates welcomed typists, house painters, and peasants without any sense of social contradiction. The broad appeal of the Proletkult's class-based language reveals the flexibility of social categories during this period of rapid social change.

Although institutional autonomy was highly valued by Proletkult members, it too was an ambiguous concept. At its most extreme, autonomy implied that such class institutions as the Proletkult would dominate government organs, an idea that certainly posed a challenge to the authority of the party and the state. But autonomy could just as easily be read as an affirmation of local control. Provincial circles insisted on their right to find their own solutions to local problems, solutions that sometimes meant forming close alliances with party and state organs. The Proletkult's endorsement of independence did not cement its institutional integrity; instead it encouraged heterogeneity.

The most basic principle of all was a shared belief in the centrality of cultural change. But what kind of culture and what kind of change? Proletkultists' answers to these questions were as varied and contradictory as those that were circulating in society at large. The organization attracted educators who hoped to reorganize universities on the basis of a vaguely defined proletarian science. It also gained the services of music teachers who wanted to share the work of the masters with the masses. Within its confines peasant children

learned Tchaikovsky's operas, workers performed Chekhov on factory stages, and urban youths discovered the principles of production art taught by the avant-garde. For many participants proletarian culture meant simply that the proletarian revolution would bring culture to them. The content of that culture, its audience, and its transmitters were all open to interpretation.

Proletkultists were inspired by a utopian vision of the society of the future. This vision is apparent in the titles of their local journals—Petrograd's The Future (Griadushchee ), Kharkov's Dawn of the Future (Zori griadushchego ), Tambov's Culture of the Future (Griadushchaia kul'tura ), from which this book takes its title. To be sure, utopianism in itself does not constitute a unified worldview, and Proletkultists put forward many conflicting plans for the ideal culture.[14] Not surprisingly, most of the organization's work never measured up to the visionaries' expansive claims, and one of the most frequent criticisms directed against the movement was that its accomplishments were much more modest than its grandiose predictions. Although this is certainly true, I still hope to capture the utopian spirit that encouraged Proletkult members, however briefly, to view piano lessons and literacy classes as major steps toward the creation of a new society. Their sincerity and enthusiasm need to be appreciated before we can begin to assess their failures.

My focus is on the period from 1917 to 1922. In these years the Proletkult was able to gain a national following and a major voice in cultural debates. Then, as a result of its changed status and funding cutbacks at the end of the Civil War, it rapidly declined to a small and restricted core of members. The final chapter outlines the organization's fate

[14] On the many varieties of early Soviet utopianism see Richard Stites, "Utopias in the Air and on the Ground: Futuristic Dreams in the Russian Revolution," Russian History , vol. 11, no. 2/3 (1984), pp. 236–57; and idem, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Visions and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution (New York, 1989).

from 1923 until it was finally disbanded in 1932. In this period we are in a very altered cultural landscape, one in which the Proletkult was at best a minor player.

The period of the movement's greatest influence, 1918–1920, coincides exactly with the years of the Russian Civil War. With its peculiar combination of hardship and utopia, devastation and creation, the war helped to further enthusiastic revolutionary goals. This was, in the words of an early Soviet scholar, the "heroic phase" of the Russian Revolution.[15] All social and economic institutions appeared to be malleable and open to the most radical change. The Proletkult's euphoric promises of a new culture captured this combative, optimistic spirit.

The Proletkult's marked decline starting in the first year of the New Economic Policy can be explained in part by the Communist Party's opposition to the movement and its subordination to state organs. Faced with severe funding cutbacks and sharp restrictions on its activities, it lost most of its local network and the majority of its followers. In most Western scholarship the Proletkult's collapse is treated as the inevitable result of the Bolshevik consolidation of power.[16] The party leadership under Lenin was not willing to tolerate a large and independent workers' movement, especially one associated with the politically suspect Bogdanov. Like other groups that advocated proletarian autonomy—such as factory committees, unions, and workers' groups within the party—the Proletkult did not survive the Civil War without radical alterations.

However, government hostility alone cannot explain the Proletkult's demise. Its participants themselves were at odds over how best to realize a proletarian culture, and much of

[15] L. Kritsman, Geroicheskii period Velikoi russkoi revoliutsii , 2d ed. (Moscow and Leningrad, 1926).

[16] See, for example, Williams, The Other Bolsheviks , pp. 185–87. For a more differentiated view see Gorsen and Knödler-Bunte, Proletkult , vol. 1, pp. 114–15.

their energies were devoted to internal disputes. The central leadership intervened in the work of local affiliates, denying them resources and even closing them down when it did not approve of their activities. Although the organization constantly criticized state programs, it still relied on the government for almost all its support, making it an easy target for cutbacks. Moreover, Proletkultists' vision of a utopian future, which inspired and united the movement, was itself a fragile construct. It depended on the heroic spirit fostered by the Civil War and on an expansive interpretation of proletarian power. The realities of NEP Russia, with its fiscal restraints and commitment to class compromise, could not sustain the same enthusiasm.

Proletkultists often overstated the importance of their institution and its powers. Nonetheless the popularity of this organization shows that cultural aspirations were also part of the reason that intellectuals, workers, and peasants went to the barricades and battlefields. Participants in the Proletkult sought not only new political and economic institutions but also a fundamental reorganization of the cultural foundations of society. Indeed, they believed that without such changes the revolution would be incomplete. "The Proletkult is a spiritual [dukhovnaia ] revolution," proclaimed the worker-poet Ilia Sadofev in 1919. "For the old, dark, capitalist world, it is more terrifying, more dangerous than any bomb. . . . They know very well that a physical revolution is only a quarter of the Bolshevik-Soviet victory. But a spiritual revolution—that is the whole victory."[17]

[17] Il'ia Sadof'ev, "Chto takoe Proletkul't," Mir i chelovek , no. 1 (1919), p. 12. All translations are mine unless otherwise identified.

1

Proletarian Culture and the Russian Revolution:

The Origins of the Proletkult Movement

The movement for proletarian culture that spread across Soviet Russia in the early years of the revolution had a complex social and intellectual heritage. It was most directly inspired by the theories of the left Bolshevik intellectual Aleksandr Bogdanov, who believed that the proletariat had to found a new cultural system, that is, a new morality, a new politics, and a new art, in order to succeed against the old elite. But proletarian culture proved to be an expansive slogan that easily bore many other meanings. It appealed to workers who were eager to break all ties with intellectuals and to cultural radicals who wanted nothing to do with Russia's past. It also inspired liberal reformers who hoped to share their knowledge of classic Russian culture with the masses.

Russian socialism, in its varied manifestations, was simultaneously a political and an educational movement. Intellectual socialist leaders keenly felt the rift between themselves, as representatives of privileged and cultured society, and the Russian masses, who were essential for a successful political upheaval. They hoped to transcend this divide by educating the masses to perceive their true interests. By doing so they believed that they were preparing the masses for radical political change. The educators had laudable goals. They tried to

convey some knowledge of Russian high culture to their students, while at the same time convincing them of the need for revolution. Yet despite these good intentions, there were strains between the teachers, who conceived of themselves as the bearers of culture (kul'turtreger ), and their students, cast in the role of willing and grateful recipients.[1]

Aleksandr Bogdanov's theory of proletarian culture was conceived as a way to transcend this tension. Inspired by his own experiences in populist circles, Bogdanov believed that it was possible to enlighten workers without dominating them.[2] His purpose was not primarily to transmit political theory or high culture. Rather he hoped to encourage workers to take control of the socialist movement themselves. This unique didactic process would allow the proletariat to formulate its own class ideology and morality, which was eventually to serve as the basis for the socialist society of the future.

Moved by their own desire to reach the people, many intellectuals devised popular educational projects in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Philanthropists, liberals, populists, and socialists of all persuasions turned in increasing numbers to become teachers in evening classes, Sunday schools, open universities, and clubs. Their efforts also encouraged a popular educational press that aimed to bring scientific knowledge, contemporary literature, and a sense of cultural community to the laboring population at large. Proletarian culture also loosely described these endeavors. The intelligentsia was bringing culture, the finest artistic and scientific accomplishment of their society, to the working

[1] See Norman M. Naimark, Terrorists and Social Democrats: The Russian Revolutionary Movement under Alexander III (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), pp. 154–86; Allan K. Wildman, The Making of a Workers' Revolution (Chicago, 1967), pp. 89–117; and Reginald E. Zelnik, "Russian Bebels: An Introduction to the Memoirs of Semen Kanatchikov and Matvei Fisher," Russian Review , vol. 35 (1976), pp. 249–89, 417–47. The Russian word kul'turtreger is taken from the German Kulturträger .

[2] See James D. White, "Bogdanov in Tula," Studies in Soviet Thought , vol. 22 (1981), pp. 33–58.

classes. They hoped to share this precious heritage and imbue the people with a sense of political and social responsibility.

For aspiring worker-intellectuals educated in study groups and, after 1905, in institutions affiliated with the labor movement, proletarian culture was an expression of their aim to challenge the cultural predominance of the intellectual elite. Some workers openly rejected the intelligentsia's aid and claimed that self-education was their goal. Although the members of these circles usually aspired to the fruits of high culture, they also encouraged their fellow workers to express their own artistic views and to criticize "bourgeois culture" and the class that sustained it.

When the Proletkult emerged in 1917 all these unlikely collaborators could claim some responsibility for its formation. Bogdanov and his allies molded Proletkult ideology to reflect their commitment to proletarian cultural leadership. The movement incorporated the participants in union clubs, people's universities, and self-education circles and reflected the ambivalent attitudes of these participants toward bourgeois culture and the intellectuals who possessed it. It also attracted part of the staff and the clientele of the liberal adult education movement, with its inclusive, democratic approach to education. These diverse understandings of culture, politics, and the proletariat would both shape and limit what the Proletkult could become.

Left Bolshevism and Proletarian Culture

The intellectual foundations for the Proletkult movement were laid in the years after the failure of the Revolution of 1905. The defeat of the revolutionary forces marked a severe crisis for the Russian socialist movement and for the Bolsheviks in particular. When the government disbanded the Second Duma in 1907 and the police began to restrict the activities of political parties and legalized worker groups, Social Democrats had to decide whether to participate in parliamen-

tary elections or to continue the revolutionary struggle through underground agitation. This dilemma split the Bolshevik faction in two. Lenin argued that it made no sense to eschew legal channels because a new revolutionary upsurge lay far off in the future. He was opposed by a group known as the "left Bolsheviks," led by Aleksandr Bogdanov, who believed that the revolution would soon continue and that the Bolsheviks should not be lulled into quiescent parliamentarianism.

The left Bolsheviks, who included Bogdanov, Anatolii Lunacharskii, Maxim Gorky, and Pavel Lebedev-Polianskii, challenged Lenin's claims to leadership and his vision of party politics. They attacked him on three different fronts: political strategy, party organization, and, most fundamentally, socialist theory.[3] Lenin's authoritarian methods of party organization received special criticism. Because the ranks of intellectual leaders had been depleted through arrests, disaffection, and exile, the left Bolsheviks feared that workers in Russia had been left without guidance. They argued that the Bolsheviks needed to encourage more collective and inclusive organizational tactics and to devote more resources to the training of worker-leaders who could assume positions of power.

Most important, the left Bolsheviks were deeply committed to a reinterpretation of Marxist theory that would give ideology and culture a more creative and central role. Opposed to the rigid materialism of Lenin and Plekhanov, they believed that the ideological superstructure was more than a reflection of society's economic base. Lunacharskii had long been fasci-

[3] There is a large and growing literature on left Bolshevism. For the most recent works see John Biggart, "'Anti-Leninist Bolshevism': The Forward Group of the RSDRP," Canadian Slavonic Papers , vol. 23, no. 2 (1981), pp. 134–53; Robert C. Williams, "Collective Immortality: The Syndicalist Origins of Proletarian Culture, 1905–1910," Slavic Review , vol. 39, no. 3 (1980), pp. 389–402; idem, The Other Bolsheviks (Bloomington, 1985); and Avraham Yassour, "Lenin and Bogdanov: Protagonists in the 'Bolshevik Center,'" Studies in Soviet Thought , vol. 22 (1981), pp. 1–32.

nated by the power of art to inspire political action. Both he and Gorky were convinced that socialism could convey the force of a "human religion" and inspire individuals to look beyond themselves to a higher good, one that encompassed the fate of all humanity. Taken together, their ideas came to be known as "god-building" (bogostroitel'stvo ).[4] At the same time, Bogdanov was engaged in a massive project to integrate the process of cognition into Marxism in order to develop a more sophisticated understanding of ideology.

From 1907 to 1911 the leftists were serious contenders for control of the Bolshevik center. Initially, their activist political tactics were very appealing to the rank and file.[5] They spread their ideas about ideology and society in socialist journals; Bogdanov even published a popular science fiction novel, Red Star , which depicted the results of a successful socialist revolution on Mars.[6] Bogdanov also reached out to a scholarly socialist audience. In his book Empiriomonism , made famous by Lenin's violent objections to it, he employed the ideas of contemporary Western European thinkers such as Ernst Mach and Richard Avenarius.[7] In Bogdanov's view the socialist polity of the future would demand a new awareness of the relationship between the individual and society and would require a different approach to ethics, science, human values, and art.

[4] Jutta Scherrer," 'Ein gelber und ein blauer Teufel': Zur Entstehung der Begriffe 'bogostroitel'stvo' und 'bogoiskatel'stvo,'" Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte , vol. 25 (1978), pp. 322–23; A. V. Lunacharskii, Velikii perevorot (Petrograd, 1919), pp. 14–22; and idem, "Ateisti," in Ocherki po filosofii marksizma (St. Petersburg, 1908), pp. 107–61.

[5] Geoffrey Swain, Russian Social Democracy and the Legal Labour Movement (London, 1983), pp. 41–43.

[6] See Loren R. Graham, "Bogdanov's Inner Message," in Red Star: The First Bolshevik Utopia , by Alexander Bogdanov, ed. Loren R. Graham and Richard Stites (Bloomington, 1984).

[7] Dietrich Grille, Lenins Rivale (Cologne, 1966), pp. 110–19; Kenneth M. Jensen, Beyond Marx and Mach (Dordrecht, 1978), pp. 67–86; and Zenovia A. Sochor, Revolution and Culture (Ithaca, 1988), pp. 42–45.

The leftists attempted to put their ideas about party organization and tactics into practice by starting two exile schools for worker-cadres in Capri and Bologna between 1909–1911.[8] Because training and education were a central part of their program, the leftists attached great significance to these schools. The first opened at Gorky's villa on the island of Capri in the summer of 1909 with thirteen worker-students elected from Russian party committees sympathetic to the left Bolsheviks' political stance. The teachers were prominent intellectuals, including Gorky, Bogdanov, Lunacharskii, and the historian Mikhail Pokrovskii. They devised an ambitious curriculum that included classes on the history of the socialist movement, literature, and the visual arts. In addition, the school offered practical courses on agitational techniques, newspaper writing, and propaganda.[9]

Capri school leaders also tried to give life to their ideas about party organization. To elaborate their critique of the Bolshevik center, the instructors gave lectures on socialist party organization with titles such as "On Party Authoritarianism." They tried to put party democracy into action on a small scale. Both students and teachers were elected to a school council that oversaw day-to-day affairs. When the council concluded that the lectures were too long and did not leave students enough time for questions, the teaching sched-

[8] On the background of the Capri school see Jutta Scherrer, "Les écoles du patti de Capri et de Bologne," Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique , no. 19 (1978), pp. 259–84. On the schools in general, see S. Livshits, "Kapriiskaia partiinaia shkola, 1909 g.," Proletarskaia revoliutsiia , no. 6 (1924), pp. 33–73; idem, "Partiinaia shkola v Bolon'e, 1910–1911 gg.," Proletarskaia revoliutsiia , no. 3 (1926), pp. 109–44; N. Semashko, "O dvukh zagranichnykh partiinykh shkolakh," Proletarskaia revoliutsiia , no. 3 (1923), pp. 142–51; Heinz Fenner, Die Propaganda-Schulen der Bolschewisten: Ein Beitrag zur Vorgeschichte der Proletkultbewegung (Berlin, 1920); Williams, The Other Bolsheviks , pp. 151–59; and the memoirs of one participant, V. Kosarev, "Partiinaia shkola na ostrove Kapri," Sibirskie ogni , no. 2 (1922), pp. 63–75.

[9] On the Capri students see Livshits, "Kapriiskaia shkola," pp. 51–53; on classes see Kosarev, "Partiinaia shkola," pp. 70–73; and Scherrer, "Les écoles du parti," pp. 270–77.

ule was restructured and questions were integrated into the teaching format.[10]

This first experiment did not fulfill the organizers' high hopes. The teachers fought among themselves, and Gorky eventually broke with Lunacharskii and Bogdanov. Five of the Capri students deserted the program to join Lenin. Only one worker-participant, Fedor Kalinin, would go on to distinguish himself as an important party leader. Nor did the school succeed in consolidating the left Bolsheviks' political position. Already in 1908, Lenin denounced their reinterpretation of Marxism in a weighty tome entitled Materialism and Empiriocriticism .[11] He ousted Bogdanov from the Bolshevik faction before the first classes in Capri began.[12] He even tried to co-opt some of the leftists' ideas by starting a party school of his own near Paris.[13]

Despite these setbacks, the Capri experiment was a formative experience for many left Bolsheviks, Bogdanov in particular. At the conclusion of the school, a group of students and teachers came together and gave themselves a new name: the Vpered (Forward) circle.[14] The Vperedists, who gained recog-

[10] Kosarev, "Partiinaia shkola," pp. 66–67.

[11] On Lenin and Bogdanov's philosophical disputes see David Joravsky, Soviet Marxism and Natural Science (New York, 1961), pp. 27–44. On the publication of this book see Nikolay Valentinov, Encounters with Lenin , trans. Paul Rosta and Brian Pearce (London, 1968), pp. 233–39.

[12] See Georges Haupt and Jutta Scherrer, "Gor'kij, Bogdanov, Lenin: Neue Quellen zur ideologischen Krise in der bolschewistischen Fraktion, 1908–1910," Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique , vol. 19 (1978), p. 329.

[13] Ralph Carter Elwood, "Lenin and the Social Democratic Schools for Underground Party Workers, 1909–11," Political Science Quarterly , vol. 81, no. 3 (1966), pp. 370–91.

[14] On Vpered in general see Krisztina Mänicke-Gyöngyösi, "Proletarische Wissenschaft" und "Sozialistische Menschheitsreligion" als Modelle proletarischer Kultur (Berlin, 1982), pp. 25–67; K. A. Ostroukhova, "Gruppa 'Vpered,' 1909–1917 gg.," Proletarskaia revoliutsiia , no. 1 (1925), pp. 198–219; "Vpered," in Bol'shaia sovetskaia entsiklopediia (Moscow, 1926–1947), vol. 13, columns 386–89; and N. Voitinskii, "O gruppe 'Vpered,' 1907–1917 gg.," Proletarskaia revoliutsiia , no. 12 (1929), pp. 59–119.

nition from the Bolshevik faction only as a literary group, included a new element in their critique of Lenin and his politics: proletarian culture. In the Vpered platform, written by Bogdanov, they argued that the party had to look beyond narrow political and economic interests to prepare ideologically for the coming revolution.

There is only one conclusion. Using the old bourgeois culture, create a new proletarian one opposed to the old and spread it to the masses. Develop a proletarian science, strengthen authentic comradely relations in the proletarian milieu, devise a proletarian philosophy, and turn art in the direction of proletarian aspirations and experience.[15]

From this point on, proletarian culture became a major theme in Bogdanov's political writings. He made it clear that he did not mean art, science, or philosophy alone. Rather for Bogdanov proletarian culture meant a distinctive class ideology. It was the spirit of socialism already apparent in embryonic form within capitalist society and expressed through the proletariat's comradely collective working habits and organizational structures.[16] In his expansive use of the term, culture had the function of organizing human perception and hence shaping action in the world. Because of the existence of social classes, there could be no unified, common basis to human perception. It was the proletariat's task to create its own ideology, its own way to structure human experience. Because the working class was organized collectively through a labor process that enhanced comradely social relations, proletarian culture would contain a more unified, harmonious view of the world than the class cultures that preceded it.

Bogdanov's ideas on proletarian culture paralleled those of Marx on proletarian class rule. The proletariat was the "uni-

[15] "Platforma gruppy 'Vpered': Sovremennoe polozhenie i zadachi partii," reprinted in Sochineniia , by V. I. Lenin, 3d. ed. (Moscow, 1936), vol. 14, pp. 452–69, quotation p. 455.

[16] A. A. Bogdanov [Maksimov, pseud.], "Sotsializm v nastoiashchem," Vpered , no. 2 (1911), columns 59–71, esp. 70–71.

versal class"; it alone embodied the values of the classless society. Proletarian culture, Bogdanov argued, would be the most universal and inclusive of all class cultures. It would provide a fundamental preparatory step toward the creation of a truly human, classless culture in the future.[17] He insisted that cultural transformation was not a frivolous enterprise; on the contrary, it was an essential prerequisite for a successful socialist revolution. Until the proletariat devised its own collective class ideology it would forever depend on the values of the bourgeoisie. Proletarian culture was the only way to insure the victory of socialism. It had to be nurtured and developed before the proletarian revolution in order for socialism to flourish.

To implement his ambitious ideas, Bogdanov looked to institutions like the Capri school. Such programs, which he called "proletarian universities," would be open to the most sophisticated representatives of the working class. They, in turn, were to form the basis of the new proletarian intelligentsia, which would then begin the task of organizing the broad mass of workers.[18] Thus Bogdanov's program was essentially an exclusive one; he was not proposing methods for mass education. Rather than abandoning the vanguardist principles of Bolshevism, he reassessed them to insure that the vanguard came from the proletariat itself.

Vpered was not a successful political group. The Capri school had only one brief sequel, in the socialist city of Bologna during the winter of 1910–1911. By then it had no official ties to the Bolshevik center. Vperedists fell victim to émigré infighting, and Bogdanov left the circle entirely by 1911.[19] His

[17] See A. A. Bogdanov, Kul'turnye zadachi nashego vremeni (Moscow, 1911), pp. 23, 54.

[18] Ibid., pp. 69–70.

[19] Bogdanov's exodus from Vpered is usually explained by his disagreements with other members over the definition and importance of proletarian culture. See Voitinskii, "O gruppe 'Vpered,'" pp. 109–10. However, Dietrich Grille speculates that he might have abandoned his political contacts in order to qualify for a general political amnesty in 1913. See Grille, Lenins Rivale , p. 33.

political challenge to Lenin's control of the Bolshevik faction was over.

But the left Bolsheviks did not give up their commitment to proletarian culture. Even after he left Vpered, Bogdanov continued to elaborate his theories. Lunacharskii pursued his interest in fine art and ideology by founding a circle for proletarian literature in Paris. There he trained exiled worker-writers, including Aleksei Gastev, Fedor Kalinin, and Mikhail Gerasimov, all influential figures in the early history of the Proletkult.[20]

With the start of the First World War Vpered was reconstituted in Geneva by Pavel Lebedev-Polianskii, who would later serve as the Proletkult's first president. With Lunacharskii's aid, he used the concept of proletarian culture to explain why most European socialists had given their support to the war effort. Their patriotism revealed that socialists' ideological development was weak. The only way to end workers' dependence on the bourgeoisie was to develop proletarian culture and make scientific and socialist education the central task of social democracy.[21]

The need to educate the working class for revolution was the Vperedists' central message. Culture, art, science, literature, and philosophy—these were the weapons needed to prepare a proletarian victory. If the working class devoted itself to education, if it shaped its own revolutionary leadership and class ideology, then it would not stand helpless and divided as it had in the years of reaction following 1905. But even as the Vperedists wrote about the proper preparations for revolution, the revolution itself overtook them.

[20] On Lunacharskii's circle see Robert C. Williams, Artists in Revolution: Portraits of the Russian Avant-garde , 1905–1925 (Bloomington, 1977), pp. 52–53; Lunacharskii, Velikii perevorot , p. 51; and Kurt Johansson, Aleksej Gastev: Proletarian Bard of the Machine Age (Stockholm, 1983), pp. 40–42.

[21] "Ot redaktsii," and V. Polianskii, "Russkie sotsial'shovanisty i zadacha revoliutsionnoi sotsial' demokratii," Vpered , no. 1 (1915), pp. 1–3, 7–8.

Culture for the Proletariat: Adult Education

Vperedists arrived at their cultural platform in part because they believed that the Russian intelligentsia was not a reliable partner for the working class. Suspicions between the workers and the intelligentsia, indeed between educated society and the lower classes in general, were deeply rooted in Russia, and the failure of the Revolution of 1905 only increased this tension. Many intellectuals were leaving politics altogether. Some began to attack the ethos of the old intelligentsia, including its traditional sense of moral responsibility for the lower classes.[22] Artists and writers who had once been concerned with social and political problems in their work began to pursue new aesthetic approaches, such as modernist writing and abstract painting, which were much less accessible to popular audiences.[23] The intelligentsia seemed confused and divided over what, if any, its social role should be.

Workers' organizations and left-wing political parties interpreted these changes in the simplest way: bourgeois intellectuals, frightened by the revolution, had abandoned the lower classes.[24] This generalization was not entirely unjustified. Many intellectuals did indeed give up illegal underground activity in the years of repression, a shift felt keenly by the workers in these movements.[25] Nonetheless, not all intellectuals lost their sense of social obligation. Instead many turned away from revolution and embraced legal activity, both cultural and educational. Members of the intelligentsia

[22] Jane Burbank, Intelligentsia and Revolution: Russian Views of Bolshevism , 1917–1922 (New York, 1986), pp. 8–10.

[23] For the debate on modernism see Jeffrey Brooks, "Popular Philistinism and the Course of Russian Modernism," in Literature and History: Theoretical Problems and Russian Case Studies , ed. Gary Saul Morson (Stanford, 1986), pp. 90–110.

[24] See, for example, the complaints of workers in the Bolshevik press, reprinted in S. Breitenburg, ed., Dooktiabr' skaia Pravda ob iskusstve i literature (Moscow, 1937), pp. 31–32.

[25] See the comments of the Bolshevik worker and Proletkult organizer Aleksandr Samobytnik-Mashirov in A. Mashirov, "Zadachi proletarskoi kul'tury," Griadushchee , no. 2 (1918), pp. 9–10.

organized and staffed the numerous adult education courses, people's universities, educational societies, libraries, and theaters that multiplied in cities and villages between 1906 and 1914. Through their work they created a much richer and more complex network of educational experiences for the lower classes than had existed before the Revolution of 1905.

The intelligentsia's involvement in workers' educational programs had begun in the mid-nineteenth century with the Sunday school movement. Inspired by the writings of a Kievan educator, university students and other intellectuals had opened Sunday and evening schools for the urban lower classes in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and several other Russian cities. These programs were staffed by sympathetic intellectuals who frequently devised their own curricula. The study plans varied greatly from place to place, ranging from simple literacy programs to rather elaborate training in the social and natural sciences. From these first experiments a whole complex of evening classes and weekend schools emerged.[26]

In the late nineteenth century more comprehensive educational programs began to take shape, modeled on some of the longer running Sunday and evening schools and inspired in part by English experiments in workers' adult education.[27] The Revolution of 1905 gave an enormous boost to these efforts, and new schools opened in St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1906 and soon thereafter in over twenty cities, including Ufa, Baku, Warsaw, and Tomsk. These institutions, called "people's universities," were sponsored by a variety of local groups and relied on the services of the local intelligentsia. For example, the Kuban People's University in Ekaterinodar was staffed by local doctors, lawyers, and gymnasium teachers.[28]

[26] On the Sunday school movement in St. Petersburg see Reginald E. Zelnik, Labor and Society in Tsarist Russia: The Factory Workers of St. Petersburg , 1855–1870 (Stanford, 1971), pp. 160–99.

[27] See Ia. V. Abramov, Nashi voskresnye shkoly: Ikh proshloe i nastoiashchee (St. Petersburg, 1900); and E. N. Medynskii, Vneshkol'noe obrazovanie: Ego znachenie, organizatsiia i tekhnika (Moscow, 1918).

[28] V. M. Riabkov, "Iz istorii razvitiia narodnykh universitetov v gody sotsialisticheskogo stroitel'stva v SSSR," in Klub i problemy razvitiia sotsialisticheskoi kul'tury (Cheliabinsk, 1974), pp. 35–36; and Medynskii, Vneshkol'noe obrazovanie , pp. 266–70.

Along with the popular universities there were also new art and music schools open to the general population. The People's Conservatory in Moscow, founded in 1906, was richly endowed with an excellent musical staff. Among the teachers were Aleksandr Kastalskii and Arsenii Avraamov, who would become important organizers of Proletkult musical training.[29] People's theaters, first begun in the late nineteenth century, also mushroomed in the years after 1905. These drama circles aimed to acquaint the lower classes with the best of Russian playwrights, including Gogol, Tolstoy, and especially Ostrovsky.[30] Although these programs made some concessions to popular tastes, such as incorporating folk music into conservatory curricula, inevitably the intellectual organizers conveyed their own standards of excellence.

Another educational forum were "people's houses" (narodnye doma ). Before the Revolution of 1905 the houses were largely used as organizational centers for cultural activities in city districts and towns. After 1905 they began to take on a more independent educational function. Like people's universities, they were sustained by many different local groups. Zemstva and cooperative organizations were by far the most common sponsors, and the government contributed money from its Trusteeship of the People's Temperance, founded with funds from the liquor monopoly.[31] Organizers hoped that the friendly and comfortable clublike atmosphere of the houses would make education more appealing to the local population. The most famous of these institutions was the

[29] N. Briusova, "Massovaia muzykal' no-prosvetitel' naia rabota v pervye gody posle Oktiabria," Sovetskaia muzyka , no. 6 (1947), pp. 46–47; and Boris Schwarz, Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia , rev. ed. (Bloomington, 1983), p. 5.

[30] Gary Thurston, "The Impact of Russian Popular Theatre, 1886–1915," Journal of Modern History , vol. 55, no. 2 (1983), pp. 237–67.

[31] Jeffrey Brooks, When Russia Learned to Read: Literacy and Popular Literature , 1861–1917 (Princeton, 1985), pp. 313–14.

Ligovskii People's House, run by the Countess Panina in St. Petersburg. Opened in 1891 as a cafeteria for students, it was taken over by the Imperial Technical Society and transformed into a night school. In 1903, when Countess Panina took control, the center greatly expanded its activities, adding a theater, art classes, and much more extensive educational programs.[32] Several worker activists involved in the Petrograd Proletkult had had some contact with this cultural center.

The public served by these varied cultural institutions was diverse, reflecting the organizers' desire to reach "the people." It included workers, peasants, and the poorer townspeople. Fees were kept as low as possible, and some events were free. Although the regime hoped cultural offerings would divert the lower classes from political action, it was not always confident they would do so. Despite close government scrutiny, it proved difficult to separate politics from cultural work. Socialist teachers found opportunities to convey Marxist and other critical ideas in their classes, and working-class pupils learned to use cultural centers as a shield for clandestine political work.[33]

A popular educational press, which took root in Russia between 1905 and 1917, also propagated the cause of adult education. Publications such as Herald of Knowledge (Vestnik znaniia ) and New Journal for Everyone (Novyi zhurnal dlia vsekh ) gained large followings, especially among culturally ambitious white-collar employees.[34] The editors, who were themselves intellectuals, aimed to provide a general overview of the most pressing scientific, social, and cultural issues of the day in an easily accessible format. Thus these journals served as guides for those interested in self-education. Although they attracted a readership among clerks, skilled

[32] Medynskii, Vneshkol'noe obrazovanie , pp. 102–3.

[33] See the memoirs of socialist teachers in one of Moscow's best-known schools for workers, E. M. Chemodanova, ed., Prechistenskie rabochie kursy: Pervyi rabochii universitet v Moskve (Moscow, 1948), pp. 13–140.

[34] Brooks, "Popular Philistinism."

workers, and primary school teachers, their simplified approach to complex issues earned them the scorn of many intellectuals, who believed their offerings were at the level of "third-rate people's universities."[35]

The intellectuals involved in these varied programs had many different motives. Some, especially after the experience of 1905, were frightened by the specter of a revolution by the "dark," uneducated Russian masses. Others hoped to combat the danger of a rising popular culture of adventure novels and tabloid newspapers, which offended many intellectuals' cultural values.[36] Political activists believed they could divert legal programs to further the revolutionary cause. But no matter what their immediate motivation or their political persuasion, they were all continuing an intelligentsia tradition of enlightenment and propaganda that had begun much earlier in the nineteenth century. These new institutions were a forum where the "culture bearers" could pass their burden on to the people and in the process help to shape the people's cultural heritage.

Clearly, most of these intellectuals had different goals than the Vperedists. They understood "culture" as the finest products of Russian and European civilization, not as a class ideology. They wanted to enlighten all of the laboring masses, not the industrial proletariat alone. Regardless of their political beliefs, they felt that the transmission of high culture was the single most important step toward positive social change. Yet despite these fundamental disagreements, both Vperedists and the reform-minded intelligentsia shared common ground. Both were convinced that education was essential for emancipation and that intellectuals had a role to play in the process of enlightenment. Although their emphasis was very different, both found value in Russia's cultural heritage. Thus it is not surprising that many of those who took part in adult educational projects offered their services to the Proletkult

[35] Ibid., p. 99.

[36] Brooks, When Russia Learned to Read , especially pp. 295–352.

after the October Revolution. There they continued the task of bringing culture to the masses, now rechristened as the proletariat.

Culture by the Proletariat: Workers' Institutions

The Revolution of 1905 spurred yet another cultural network, one that was controlled by the laboring classes themselves. The organizational laws of 1906, which allowed the legal formation of unions, encouraged the creation of workers' clubs and educational societies closely tied to the labor movement. With names such as "Enlightenment," "Education," and "Knowledge," these groups gained great popularity among both unionized and nonunionized workers.[37] The intended membership was the urban proletariat, which, although not always easy to define, was surely a narrower public than the people earmarked for general adult education. The programs were also more limited, largely because of restricted resources.

The rapid growth of cultural circles showed the workers' desire for education and entertainment. It was also an expression of their profound distrust of the intelligentsia. Many believed that the liberals had betrayed them in the revolution and were appalled by the socialist intellectuals' waning interest in the political struggle.[38] The new institutions were a way to educate a proletarian leadership through channels workers themselves controlled. Participants hoped that these circles would encourage an independent working-class intelligentsia, thus insuring that the proletariat would never have to

[37] Victoria E. Bonnell, Roots of Rebellion: Workers' Politics and Organizations in St. Petersburg and Moscow , 1900–1914 (Berkeley, 1983), pp. 328–34.

[38] See David Mandel, "The Intelligentsia and the Working Class in 1917," Critique , no. 14 (1981), pp. 68–70; and A. Mashirov, "Zadachi proletarskoi kul'tury," Griadushchee , no. 2 (1918), pp. 9–10.

depend on unreliable intellectual allies, as it had during the Revolution of 1905.[39]

Unions and clubs had an uneasy relationship with people's universities and related groups associated with the highly suspect liberal intelligentsia.[40] Although workers attended these institutions, many believed that their own clubs and societies should replace them and become, in the words of one union publication, "the center of [workers'] entire intellectual lives."[41] They aspired to self-education (samoobrazovanie ) and aimed to exclude the intelligentsia entirely. Yet despite these optimistic hopes for autonomy, cultural circles still solicited the help of intellectuals as teachers and lecturers. These contradictory sentiments of need and resentment further strained relations between workers and educated society.[42]

The offerings in workers' clubs and theaters revealed the dominant influence of the prevailing high culture. Along with classes on the history of the socialist movement were events very similar to those offered in people's universities and people's houses. Tchaikovsky and Rimskii-Korsakov were performed at musical evenings and the repertoire of proletarian drama circles was not markedly different from that of people's theaters. In its first season the theater at the Petrograd workers' society "Source of Knowledge and Light" performed Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Shakespeare. Russian classics were by far the favorites in club libraries.[43] Although the proletariat

[39] See I. N. Kubikov, "Rabochie kluby v Petrograde," Vestnik kul'tury i svobody , no. 1 (1918), pp. 28–29; Leopold Haimson, "The Problem of Social Stability in Urban Russia, 1905–1917," in The Structure of Russian History , ed. Michael Cherniavsky (New York, 1970), p. 346; and Swain, Russian Social Democracy , pp. 34–35.

[40] Swain, Russian Social Democracy , pp. 36–37.

[41] Nadezhda , no. 2 (1908), p. 8, cited in Bonnell, Roots of Rebellion , p. 332. Bonnell's translation.

[42] Bonnell, Roots of Rebellion , pp. 332–34.

[43] I. N. Kubikov, "Literaturno-muzykal'nye vechera v rabochikh Klubakh," Vestnik kul'tury i svobody , no. 2 (1918), pp. 32–34; idem, "Uchastie zhenshchin-rabotnits v klubakh," Vestnik kul'tury i svobody , no. 2 (1918), pp. 34–37; I.D. Levin, Rabochie kluby v dorevoliutsionnom Peterburge (Moscow, 1926), pp. 108–10; Medynskii, Vneshkol'noe obrazovanie , p. 293; and Breitenburg, Dooktiabr'skaia Pravda , pp. 50–51.

was certainly not immune to the attractions of the tabloid press and popular adventure stories, these societies tried to encourage more "refined" cultural tastes.[44]

Not all workers were content to accept the Russian classics as their own, however. While participants in proletarian clubs debated the value of bourgeois culture, creative literature by workers began to appear in the socialist press. Inspired in part by the example of Maxim Gorky, proletarian authors began to describe their lives of labor and political struggle in stories, poems, and plays. The worker-poet Egor Nechaev made a name for himself at the end of the nineteenth century with his evocations of political freedom, socialism, and factory life. By the first decades of the twentieth century socialist newspapers and journals published more and more literature by authors with direct experience in the factory. The best known writers associated with the Proletkult, including Mikhail Gerasimov, Vladimir Kirillov, and Aleksei SamobytnikMashirov, all began publishing in leftist journals and newspapers before 1917.[45] Sympathetic workers and intellectuals pointed to this new literature as evidence that the proletariat could create a significant artistic culture of its own.

The results did not please everyone. A prominent Menshevik, Aleksandr Potresov, gave a very somber assessment of workers' creative accomplishments. Because of their timeconsuming economic and political struggles, he believed that workers did not have the leisure to turn to culture. The art

[44] On the attraction of popular culture see Semen Kanatchikov, A Radical Worker in Tsarist Russia: The Autobiography of Semen Ivanovich Kanatchikov , trans, and ed. Reginald E. Zelnik (Stanford, 1986), pp. 19, 401; and Swain, Russian Social Democracy , p. 60.

[45] For an overview of this literature see V. L. L'vov-Rogachevskii, Ocherki proletarskoi literatury (Moscow, 1927), pp. 32–44; L. N. Kleinbort, Ocherki narodnoi literatury , 1880–1923 gg. (Leningrad, 1924), pp. 108–28; and A.M. Bikhter, "U istokov russkoi proletarskoi poezii," in U istokov russkoi proletarskoi poezii , ed. R. A. Shatseva and O. E. Afonina (Moscow, 1965), pp. 5–30.

they engendered was modest and unoriginal, and revealed the overwhelming dominance of bourgeois culture over their creative lives. The proletarian community, organized around struggle, was a Sparta, not an Athens. Workers should not delude themselves into thinking that they could create a proletarian culture under capitalism; instead they should alleviate the conditions that caused their subjugation.[46]

Many people, including Gorky himself, stood up to defend the quality of proletarian literature against such charges.[47] But the most passionate responses came from those who insisted that Potresov did not understand how culture and politics were intertwined. Valerian Pletnev, a Menshevik workerintellectual who would eventually become president of the Proletkult, argued that the proletariat was creating a culture through its clubs, evening schools, and theaters. Workers should be encouraged in these pursuits; they should not be told that their efforts were of little value, for the proletariat could only be victorious if it challenged the power of the bourgeoisie with its own proletarian culture.[48]

Writing in an exile journal, the Vperedist Lunacharskii insisted that Potresov minimized the importance of art in workers' lives and in the working-class movement as a whole. Potresov's depressing predictions about the dominance of capitalist culture were irrelevant. Workers should learn from the art of the past, but they would also learn how to apply that knowledge for their own ends.[49] Rather than turning their

[46] A. Potresov, "Tragediia proletarskoi kul'tury," Nasha zaria , no. 6 (1913), pp. 65–75. See also idem, "Otvet V. Valerianu," Nasha zaria , no. 10/11 (1914), pp. 41–48.

[47] See M. Gor'kii, "Predislovie k 'Sbornik proletarskikh pisatelei,' "in Sobranie sochinenii v tridtsati tomakh , by M. Gor'kii (Moscow, 1953), vol. 24, p. 170.

[48] V. F. Pletnev [V. Valerianov, pseud.], "K voprosu o proletarskoi kul'ture," Nasha zaria , no. 10/11 (1913), pp. 35–41.

[49] A. V. Lunacharskii, "Chto takoe proletarskaia literatura i vozmozhna li ona?" Bor'ba , no. 1 (1914), reprinted in Sobranie sochinenii v vos'mi tomakh , by A. V. Lunacharskii, ed. I. I. Anisimov (Moscow, 1967), vol. 7, pp. 167–73.

backs on culture for politics, they should discover how to use art as a weapon in the struggle for socialism.

The links between culture and politics were illustrated very graphically when the revolutionary movement began to regain its momentum in the turbulent years from 1912–1914. Workers' clubs and educational societies became increasingly politicized, as many participants moved from the more cautious Menshevism to Bolshevism.[50] Because unions were under close surveillance, clubs became centers for underground organization. The St. Petersburg educational society "Science and Life," dominated by Bolsheviks, was a planning center for the strike activity that swept the city in July 1914.[51]