Preferred Citation: Eder, James F. On the Road to Tribal Extinction: Depopulation, Deculturation, and Adaptive Well-Being Among the Batak of the Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1987 1987. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5s200701/

| On the Road to Tribal ExtinctionDepopulation, Deculturation, and Adaptive Well-being among the Batak of the PhilippinesJames F. EderUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1987 The Regents of the University of California |

To Pia, Alan, and Jonathan

Preferred Citation: Eder, James F. On the Road to Tribal Extinction: Depopulation, Deculturation, and Adaptive Well-Being Among the Batak of the Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1987 1987. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5s200701/

To Pia, Alan, and Jonathan

Preface

In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the Batak of the Philippines were a physically and culturally distinct population of about six hundred individuals inhabiting the mountains and river valleys of central Palawan Island. Isolated by land from other indigenous tribal populations on Palawan and by the Sulu Sea from all but sporadic contact with Filipino and Muslim peoples elsewhere in the Philippine archipelago, the Batak had evolved an elaborate tropical forest foraging adaptation. Like their presumed distant relatives, the Andaman Islanders, the Semang of the Malay Peninsula, and the various Negrito groups on Luzon, they lived in small, mobile, family groups and hunted or gathered a variety of forest, riverine, and coastal foods. Whether or not they enjoyed a state of “primitive affluence,” the Batak must have achieved at least a modicum of success in meeting their subsistence needs and in resisting whatever perturbations penetrated their realm from the outside world, for they had survived for centuries.

By the closing decades of the twentieth century, however, the Batak were in disarray. No longer were they isolated from surrounding populations; everywhere were the homesteads and villages of Filipino farmers who had come to

Palawan in search of land and a better way of life. And no longer did the Batak appear to be an economically, culturally, or evolutionarily successful people. They still survived, as did a part of their former hunting-gathering lifeway. But even as they had also adopted portions of the lifeways of surrounding peoples, they found themselves in much reduced circumstances. Undernourished as individuals, decimated as a population, and virtually moribund as a distinct ethnolinguistic group, the Batak appeared destined for extinction sometime early in the twenty-first century.

The story of the Batak is one that has been repeated throughout the contemporary tribal world: a society that has seemingly thrived for centuries suddenly falters and passes out of the human record. In some cases, the causes of tribal disappearance are tragically obvious. In the centuries following the era of European expansion, the ravages of epidemic disease and wholesale alienation of land and other tribal resources obliterated hundreds of tribal populations. Many escaped these catastrophes only to fall victim to less visible but equally powerful forces—the ecological changes, social stresses, and cultural disruptions set in motion by incorporation into wider socioeconomic systems. Such a people are the Batak.

This work is a detailed account of the Batak's encounter with, and apparent defeat by, the “outside world.” To be sure, it is not the first book of its kind. Charles Wagley's Welcome of Tears, an eloquent account of the demographic and cultural demise of the Tapirapé Indians of Brazil, is probably closest in subject and intent. Colin Turnbull's controversial The Mountain People, a case study of the Ik of Uganda, centered needed attention on the potentially grim consequences of culture loss and social dysfunction (regardless of any ethical questions it may have raised). At a more regional level but of the same genre are Shelton Davis's Victims of the Miracle and Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf's Tribes of India: The Struggle to Survive. And beyond these recent and most closely related works, there is a long and important tradition in

Western anthropology of documenting the impact of modernization and development on indigenous peoples.

This volume differs from previous work on the subject in two important respects. The first is the breadth and depth of my data, which span a period of fifteen years—from 1966, when I first encountered the Batak while a Peace Corps volunteer assigned to teach high school in Palawan, until 1980–81, when I studied them for sixteen months while supported by a sabbatical leave from Arizona State University and a Wenner-Gren Foundation Grant-in-Aid. In between, I made a series of shorter visits to the Batak. I visited them periodically during 1968, at which time I was still in the Peace Corps but teaching adult Tagalog literacy in a Tagbanua community close to the Batak's home. I lived with the Batak for four months during 1972, following twenty months of dissertation fieldwork in a Cuyonon farming community elsewhere on Palawan, while supported by a National Institutes of Mental Health Predoctoral Research Fellowship. I visited them again for two months during 1975, then supported by an Arizona State University Faculty Grant-in-Aid.

Repeated field visits to the Batak over an extended period allowed me to come to know the entire population rather than just a sample of it. By 1981, I had visited all local Batak groups numerous times, and there were almost no adults and few children whom I had not met personally. Moreover, return visits revealed to me, as a single visit could not, the rapid and profound changes that had overtaken the Batak, making it possible for me to adjust my methodological approach as my thinking on their plight evolved. During my earlier visits I employed Cuyonon, the local contact language, but I later learned to speak Batak and to employ it in my fieldwork. Eventually, I was able to complete two thorough censuses, eight years apart, of the entire population; assemble an extensive array of quantitative data on how Batak utilize their time and what they receive from their various subsistence pursuits; measure the height, weight, and skinfold thickness of a sample of adults and children; identify

the principal cultural beliefs and institutions that have been lost since World War II; record a detailed, week-by-week account of the settlement pattern of one entire local group over the course of a year; and collect a variety of more qualitative information about traditional and present-day Batak economy, society, and culture. I obtained, in short, a uniquely comprehensive set of data to work with.

The second respect in which this book differs from others on the subject concerns my analytical orientation and theoretical intent. While this book is fundamentally a case study, I have made a systematic effort to use this case to address some wider issues having to do with human adaptation in general. I am concerned, in particular, with the vital but poorly understood role played by human motivation and with the importance of ethnic identity in fostering that motivation.

In overview, my argument is that something has gone wrong for the Batak, as evidenced by carefully collected data on demography and nutritional anthropometry. These data show that, as a population, they are failing to reproduce at a replacement level and, as individuals, they are in generally poor health. I attribute this circumstance to adaptive disorder in the following manner. The proximate cause of Batak adaptive difficulties, I argue, is a complex of dysfunctional economic and social behavior of the Batak themselves: disinterest in work, poor diet selection, inadequate infant care, and the like. Such behavior may not differ very much from how the Batak have always behaved, but it no longer measures up to the demands of physical and cultural survival. The ultimate cause, I argue, is growing articulation with the outside world—or, more particularly, the precise nature of that articulation.

Connecting my ultimate cause, articulation with wider Philippine society, and my proximate cause, dysfunctional individual behavior, which occupies much of my analysis, is the notion of social stress. I argue that the manner in which the Batak have been incorporated into lowland Philippine

social and economic life has severely stressed many of their social roles and relationships. Simultaneously, many traditional cultural beliefs and institutions have been eroded or have even disappeared, thereby undermining individual and cultural capacity to cope with social stress. In consequence, in this admittedly functionalist view of culture, individual Batak are so debilitated as to be unable to adequately meet the physiological, psychological, and social stresses—that is, the adaptive demands—of everyday life.

A crucial point is that while the adaptive demands presently confronting the Batak may appear heavy, they are not impossibly so. I believe there are genuine and unexploited opportunities for the Batak to “do better”—yet they do not appear to strive to do better. Were the Batak fat and happy, this matter would be, at least for an anthropologist, a non-issue. But it becomes a critical issue in the present situation wherein individual and tribal well-being is at stake. I hasten to add that I do not attribute the Batak's failure to do better to any intrinsic shortcomings. While I am extremely interested in the interplay of economic behavior and the cognitive and noncognitive attributes of individuals, I see these attributes as largely derivative of a particular sociocultural system. The Batak's problem is that their own sociocultural system is malfunctioning. For fifteen years I was strategically placed to observe a massive failure in one society's capacity to equip and motivate men and women to cope adequately with the problems they face and to otherwise survive physically and culturally as a distinct ethnic group. This work represents my desire to describe and analyze that failure and learn from it.

The manuscript was completed in the Philippines during 1984–85, when I was a Visiting Research Associate at the Institute of Philippine Culture of Ateneo de Manila University and while I was supported by an ASEAN Fulbright Research Award to undertake some comparative research on the adaptive difficulties of other Philippine Negrito groups. I would like to thank these and the previously mentioned

institutions and agencies for their generous support of my research. I also acknowledge permission from Mankind and American Anthropologist to use previously published material. In addition, many individuals helped make this book a reality. I owe special debts of gratitude to George Appell, Nelson Asebuque, Pons Bennagen, Sheila Berg, Apolinario Buñag, Eduardo Cacal, David Cleveland, Thomas Conelly, Carlos Femandez, Rafaelita Fernandez, Raul Fernandez, Brian Foster, Robert Fox, Raymond Hames, Thomas Headland, Barry Hewlett, Connie Kloecker, Edward Liebow, Emilio Moran, Keiichi Omoto, Pedro Nalica, Roman Palay, Ben Pagayona, Steve Pruett, Andrew del Rosario, Marsha Schweitzer, Thayer Scudder, Rudy Tirador, Ernesto Torres, Pedro Vargas, John Vickery, Reed Wadley, Charles Warren, and Felix and Amelita Yara. Most of all, I want to express my deep gratitude to the Batak, a warm and gentle people who deserve far better than their present lot in life.

1

Introduction.

One of the most pressing global social issues of the late twentieth century is the rapid disappearance of many of the world's remaining tribal populations. This disappearance, which entails an irreversible loss of cultural institutions and, in many cases, actual physical extinction, raises scientific and humanistic questions of the most urgent sort. On the one hand, there are clear scientific imperatives—to record for posterity as much as possible about vanishing and distinctive lifeways and to explain, in evolutionary terms, why these lifeways could be so summarily extinguished after surviving for generations. On the other hand, there is the more humanistic concern to do something about “detribalization”—a concern that reflects not only a moral imperative but a growing awareness of the practical contribution that the cultural knowledge of tribal societies might someday make to our survival. But what can be done, or even what should be done, is often unclear.

This careful, detailed analysis of the detribalization of the Batak, a Negrito group in the Philippines, provides important insights into these questions. Traditionally nomadic forestfood collectors, the Batak inhabit the interior of Palawan, where their hunting-gathering economy was once finely

tuned to their tropical environment and relatively undisturbed by outside influences. But, as a result of contact with lowland Philippine society, the Batak long ago began to “settle down”: while continuing to hunt and gather, they also plant crops and trade with and work for their neighbors. As the consequences of these changes have reverberated through the fabric of Batak society and culture, they have paid dearly; they are declining in number, and many elements of their traditional culture have been lost. Indeed, some local groups have already disappeared, and it seems to be unlikely that many others will survive long into the next century.

It is well documented, of course, that tribal people [1] in all parts of the world have for centuries suffered from the adverse effects of the expansion of “civilization” into their traditional territories. Tribal suffering, as the result of European colonial expansion and, later, incorporation into modern nation-states, has ranged from habitat despoliation to disease and malnutrition to the decline of traditional cultural practices to outright tribal extinction. The social science literature on these processes is voluminous and includes both case studies (e.g., Cipriani 1966; Turnbull 1972; Wagley 1977; von Fürer-Haimendorf 1982) and more general assessments (e.g., Davis 1977; Bodley 1982; Goodland 1982).

The title of John Bodley's book, Victims of Progress, effectively captures the implicit model underlying much of this work. On this view, it is held that prior to contact, tribal societies enjoy a state of harmonious equilibrium with their environment and, if not outright primitive affluence, relative contentment. Such societies are contrasted with tribal societies, or the remains of them, after exposure to industrial civilization and “modernization,” when their traditional “adaptations” have been disrupted or even destroyed by outside forces that the tribal people themselves cannot control. Indeed, except as sufferers or innocent victims, these people scarcely participate in the processes in question. The victims-of-progress model has helped to draw needed attention to the often tragic human costs of colonial expansion

and development. But it must be refined if studies of detribalization are to advance our understanding of the more general processes of cultural adaptation, change, and evolution or to serve as effective guides to policymaking. The model is deficient in two respects: it incorrectly stereotypes the nature of tribal societies and cultures, and, more fundamentally, it fails to come to terms with the complex nature of human adaptation.

Incorrect stereotypes of tribal societies are scarcely a recent phenomenon in anthropology; those associated with the victims-of-progress model reflect its characteristic preoccupation with the alleged contrast between tribal societies and modern industrial societies. Thus, it is often said that tribal cultures are antimaterialistic (e.g., Bodley 1982:10–11). This is simply not true about all tribal societies. The traditional cultures of the Tolai (Epstein 1968; Salisbury 1970) and the Iban (Sutlive 1978), for example, are said to have fostered such personal traits as individualism and achievement orientation. Such traits, predictably, powerfully influenced the respective responses of these peoples to the opportunities for participation in wider socioeconomic systems. Similarly, in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, a traditional precontact emphasis on wealth accumulation, status achievement, and competition helped spur postcontact cash cropping (Finney 1973). Those who stereotype precontact and postcontact tribal societies should take heed of Baker's observation that “the present-day integration of traditional populations into the modern urban industrial societies is not producing a uniform set of stresses or responses in the various populations” (1984:11).

The incorrect stereotypes of tribal society and culture visible in some approaches to tribal social change reflect, in part, broader shortcomings in anthropological theory. Thus, not only observers of tribal social change but ecologically oriented anthropologists in general have long characterized uncontacted aboriginal societies as being in some sort of natural equilibrium (Love 1983:4). According to Love, there

is in such models “very little sense of contradiction and conflict in human societies, especially small-scale ones, either internally or with neighbors. Aboriginals, lying on the other side of the Rousseauian great divide, apparently have no serious internal divisions and seem to make few ecological mistakes until pressed upon by outside forces, despite growing evidence to the contrary” (ibid.).

Although the equilibrium assumption has been abundantly criticized, it is still common among anthropologists, particularly when contrasts with the modern world are at stake. But if we are to make a more pragmatic assessment of the impact of change on tribal well-being, it is essential to recognize that at least some tribal societies had serious ecological and social problems of their own prior to contact. Van Arkadie, in critically examining the notion that indigenous peoples made effective and ecologically conservative adjustments to their environments, puts it thus:

If there was in some sense a balance, this was in part because the human condition was often nasty and short (although not, we must add, brutish). Among the reasons why such communities survived over the long term and did not destroy their environments were high death rates, which kept the population in check, and extreme austerity of consumption for extended periods. Before we succumb to sentimental visions of paradise lost, it is worth noting that ecological balance may be maintained in some circumstances by the tight limits on both population size and choices open to humans—an equilibrium at a low level of human welfare…. Moreover, it is not clear from the evidence available, how far an ecological balance was in fact maintained. (1978:163–164)

The victims-of-progress approach to tribal social change is also naive theoretically with respect to the nature of human adaptation: it fails to address a growing consensus that such adaptation must be understood in terms of the reproductive and other strivings of individuals. Indeed, it is often unclear

who or what, precisely, is being “victimized” by progress. Many anthropological analyses of tribal sufferings are vague and overgeneralized, conflating questions of the welfare and survival of societies and cultures with questions of the welfare and survival of people. When tribal peoples are said to be in difficulty, the difficulties may be inadequately documented. The “evidence” of distress may consist of informants' invidious comparisons of life in the present with life in an idealized past, or it may consist only of the anthropologist's own ethnocentric assumption that a person ought to be distressed by those particular circumstances. Many anthropological analyses of the impact of development on tribal societies have the appearance of reasonableness, which, on closer scrutiny, is revealed to derive from functionalist assumptions rather than from hard evidence. Even when there is adequate documentation of particular and serious physiological, psychological, or social impairments, the analyses may fail to specify how particular exogenous or endogenous changes brought about the impairments.

Because this model does not deal adequately with human adaptation, it obfuscates the fact that change and adjustment—including demographic fluctuation and culture change and loss—are normal processes in human societies. Knowing where the “best interests” of tribal peoples lie—in change or in stability—is an extremely difficult problem for which the victims-of-progress model provides limited guidance. As humanistically inclined outside observers, we may lament any culture change or loss in tribal societies, but we must recognize that not all such change or loss merits our intervention.

Finally, treating contemporary tribal peoples as victims of the changes going on around them obscures their frequent complicity in the detribalization process. This is not to deny the numerous and well-documented cases of tribal destruction following establishment on tribal lands of homesteads, logging or mining operations, corporate agricultural plantations, or large water projects. Where such intrusions have

brought land expropriation, habitat destruction, epidemic disease, or even genocide, tribal peoples literally are victims (for such a perspective on the difficulties of tribal Philippine peoples, see McDonagh 1983). But many contemporary cases of detribalization do not involve such dramatic or readily identified external factors. Rather, less visible forces associated with the political economics of modern nationstates—market incentives, cultural pressures, new religious ideologies—permeate the fabric and ethos of tribal societies and motivate their members to think and behave in new ways. These new ways of thinking and acting are often dysfunctional with respect to individual and tribal welfare; that is, by their own changing behaviors, values, and preferences, tribal peoples bring many of their difficulties on themselves.

It should be noted that this assertion does not establish blame but, again, points out a crucial shortcoming in the victims-of-progress model: it diverts attention from the very processes of individual choice and change that must be understood if we are genuinely to assist tribal peoples in distress. Many anthropologists would argue, of course, that tribal peoples are entitled to embrace change, if they want to, on their own terms. But the model provides little room for them to make free choices with respect to change and even less guidance for determining whether these choices are “well informed.” To be sure, difficult questions are involved. How do we distinguish voluntary from coerced choices? At what point will we conclude that tribal peoples must bear the consequences of their behavior, even if those consequences include tribal disappearance? But if these are difficult questions, they are best met head on, unconstrained by a paternalistic, even ethnocentric model that celebrates tribal societies as essentially good and sees the rest of the world as essentially evil.

Central to my analysis and to the theoretical contribution I hope to make is a focus on the wellsprings of individual behavior. The failure to focus clearly on individuals in situ-

ations of change—on their wants and needs, on the demands placed on them—in part explains, I believe, why a large anthropological literature on the impact of modernization on tribal societies, however valuable it is for documentary purposes, has contributed relatively little toward the construction of a more adequate theory of human adaptation and culture change. Too many anthropologists pay lip service to anthropological truisms about the centrality of individual decisions in cultural evolution but in fact treat individuals as helpless (and hapless) bystanders in the change process. Hence, my concern here with the circumstances, abilities, and motivations that influence the individual's decision making in times of rapid culture change—with details of the what, how, and why of sociocultural function and malfunction.

But how, in practice, are “function” and “malfunction” in human societies to be distinguished? These notions are closely linked to a central anthropological concept, adaptation. Although definitions of this term are readily had, one of the thorniest conceptual and methodological problems facing anthropologists interested in cultural persistence and change is the construction of indexes that satisfactorily measure human adaptive function and malfunction, or, as I will have it, adaptive “success” and “failure.” Following evolutionary biology, anthropologists of an ecological bent have interpreted human adaptability as referring to “ecological success as measured by demographic, energetic, or nutritional criteria” (Moran 1979:9). Examples of such criteria familiar to anthropologists are a group's balance between natality and mortality and the relative energetic efficiency of its food-getting activities. These are only indexes, however; they are not a firm measure of “fitness,” which, on this view, is reproductive success, something that is difficult to ascertain directly (ibid.).

Many anthropologists (and others), of course, are uncomfortable with the use of such materialistic and biologically derived indexes as the energetic efficiency of food procurement to evaluate human adaptive success. But indexes that take into account the kinds of factors they would presumably

like to emphasize—for example, quality of life—are even more difficult to develop. Bodley's (1982:150) discussion of how one might assess the “standard of living” of a society is helpful in this regard. He does not introduce the concept of adaptation at this point, but his list of possible indexes for assessing societal standards of living loosely suggests some additional criteria for evaluating adaptive success. This list includes not only such previously mentioned factors as nutritional status and demographic structure but also health status, crime, family stability, and relationship with the resource base.

Such “quality-of-life” criteria have the important advantage of being potentially measurable in field research. In practice, however (and in the case at hand), it may be difficult or impossible to assemble adequate longitudinal data on change in such social attributes as “crime” or “family stability.” But these are precisely the kinds of data that are essential if we are to rest an allegation of societal malfunction or adaptive disorder on more than condemnation of the present and idealization of the past. (In what society today are crime rates and family instability not said to be increasing?) Later in this volume, I attempt to build an inferential argument that factors not unlike increasing crime and family discord are in fact part of the general deterioration of the Batak lifeway. But I do not want the burden of proof that the Batak are in serious adaptive difficulty to rest on such allegations.

With the intent of keeping my own criteria for determining the presence or absence of adaptive disorder as broadly based as possible, I was initially attracted to Jochim's (1981:19) definition of human adaptation as “the possession of a valid set of solutions to a variety of problems.” His approach, which owes much to Dobzhansky (1974), calls attention to the strategizing or decision-making aspects of human adaptation and to the fact that diverse goals, only one of which is reproductive success, underlie that decision making. I find both emphases congenial. But like many an-

thropological usages of adaptation, it is not clear in Jochim's definition how to distinguish, in practice, adaptation-related behavior from all behavior. Thus, while adaptive failure would presumably occur when a people's solutions for dealing with life's problems were no longer “valid,” it is not readily apparent how to assess validity or how to distinguish problem solving from living.

I return in the conclusion to an emphasis on adaptation as successful coping with life's problems. For purposes of developing my empirical argument for the Batak case, considerations such as the foregoing led me to settle on a recent, narrower definition of adaptation articulated by Baker:

An adaptation is simply any biological or cultural trait which aids the biological functioning of a population in a given environment. Thus, it includes such aspects as a population's health, ability to feed itself adequately, functional capability in its physical environment and reproductive performance. This definition encompasses the more precisely defined forms of adaptation used in genetics and the adaptability responses which are denoted by such terms as acclimatisation. However, it stops short of encompassing sociocultural adjustments which do not have demonstrable effects on human biological functions. (1984:2)

In my view, this definition has the advantage of implicitly specifying what will be taken as evidence of adaptive failure: presumably, it occurs when a population's biological and cultural traits are inadequate to support its “biological functioning,” that is, to maintain its health, its subsistence, and its reproductive performance. These are the criteria by which I assess how well the Batak population is functioning (chaps. 4 and 5). Baker, furthermore, specifically juxtaposes against the concept adaptation the important concept stress. According to him “stresses are defined as those natural or cultural environmental forces which potentially reduce the population's ability to function in a given situation” (ibid.:2). This concept (developed in chap. 6) provides the crucial causal link, in my

analysis, between biological malfunction (my proximate evidence of adaptive difficulty) and wider patterns of cultural disruption. The significance of such disruption is visible, in turn, in a final important attribute of Baker's relatively strict definition of adaptation: it specifies that certain particular cultural traits are involved with adaptation, namely, those that demonstrably affect biological functioning. This precision orients my analysis of how the disappearance of certain traditional cultural institutions and beliefs that once functioned to contain stress has undermined individual coping abilities and Batak adaptive well-being (chap. 7).

Despite my attempt to be precise, some may find my definition of adaptation—and thus my criteria for assessing adaptive well-being—too broad. Those of sociobiological inclination might want to argue that my approach diverts attention from the central issue of reproductive success. Durham (1979:47), for example, believes that successful human adaptation would be measured simply by the long-term representation of an individual's genes in a population. I have sought to make my approach consistent with evolutionary biology by using the concept of human adaptation in a way that rejects “adaptationism” (Gould and Lewontin 1979) and allows for imperfect adaptations and even for extinction (Greenwood 1984:66–69). However, in my view, which I believe is shared by many of my anthropologist colleagues, there is more at issue in human adaptation than reproductive striving.

Indeed, some might argue that my approach to human adaptation is too narrow. My criteria for assessing adaptive well-being, it could be said, take no account of such uniquely human attributes as highly developed cognition and emotion and thus do not allow for a response, for example, to the question of how tribal peoples themselves may feel, regardless of their physiological or demographic circumstances, about their changing lives. Certainly, the presence or absence of subjective or psychological distress is another possible index of societal ill-health or malfunction, one that has, in

fact, also been employed by anthropologists. Savishinsky's (1974) study of the Hare Indians focused on the manner in which contact-related experiences have exacerbated endogenous social and psychological stress loads, with a heightened incidence of mental illness or psychopathology (as defined by the people themselves) being indicative of severe adaptive difficulty (pp. 217–219). Similarly, Bruner (1976:242), examining the kinds of adaptations that the Toba Batak have worked out with the modern world, takes their apparent “lack of internal stress” (i.e., psychological stress) as prima facie evidence that they are “successfully adjusting.” The use of the absence of psychological distress as a criterion for adaptive success offers the advantage of being relatively nonpaternalistic. According to this, in effect, if people are satisfied with their new lives, who are we to question their well-being?

But this reasoning conflates broader issues of adjustment (admittedly important in its own right) with narrower issues of adaptation, which, after all, has to do with persistence over time. If methodological problems could be overcome, however, increasing psychological distress would in my view be a legitimate, even desirable addition to the more biologically oriented criteria I employ here to establish the presence of adaptive malfunction. Further, I see it standing in the same relationship to my variables as the criteria I have employed, that is, like nutritional and demographic difficulties, psychological difficulties (were they present) would likely have antecedents in ecological disruption, social stress, and cultural change. As it happens, I believe that the Batak suffer from a certain psychosocial malaise, but I did not attempt to systematically document this belief in the field. Later chapters will, however, provide some inferential evidence to support it.

Some may find the evidence of adaptive breakdown I do present to be equivocal. The Batak may seem to be disappearing, it could be argued, but it has seemed so for years. Similarly, some Batak may be ill or undernourished, but

others are healthy and robust. That is precisely the point. The “disappearance” of the Batak has been protracted. In any one year, therefore, the circumstances of the Batak do not look so bad; to some, they might appear to be surviving or even adapting. I should perhaps point out that there is a timelessness to many studies of tribal societies which obscures the trajectories of change that such societies travel (and thus the historical and political economic factors that underlie these trajectories; see Love 1983:4). In my view, the emphasis in this work on the history of the Batak (or one hundred years of their history) is one of its great strengths. In any case, I hope that anyone doubtful of the evidence presented in chapters 4 and 5 supporting my argument that the Batak are in serious adaptive difficulty will withhold skepticism about the imminence of Batak disappearance until after consideration of the entire analysis.

Organization

Chapter 2 concerns the Batak as they were around 1880, on the eve of greatly intensified contact with outside peoples and with wider socioeconomic systems. While the Batak may have long practiced agriculture to a small extent and been in contact with trading populations in the Sulu archipelago for centuries, in 1880 they were still quite isolated in their traditional territory and firmly committed to a hunting-gathering way of life. The closing decades of the nineteenth century initiated a period of sustained migrations to Palawan by land-seeking migrant farmers from throughout the Philippines. Migration of lowland Filipino farmers, which greatly increased after World War II and continues to the present, would ultimately precipitate irreversible changes in Batak adaptation. But when these migrations began, the Batak, although not untouched, were still relatively undisturbed.

My reconstruction of Batak life one hundred years ago is only that. It is based on the earliest historical accounts of the

Batak, on comparative data from other, more isolated Southeast Asian Negrito populations, and on the oldest Bataks' personal accounts of “life in the old days.” These accounts are stereotypical at best and of uncertain date, but with caution, they can reasonably be projected back to the turn of the century. If these sources seem an unsatisfactory basis for an ethnographic account of a vanished lifeway, my approach is far more satisfactory than the commonly practiced alternative—taking the surviving hunting-gathering component of a foraging people's present lifeway, blowing it up to full size, and projecting it back into a timeless past as allegedly exemplifying a once-universal hunting-gathering way of life in some part of the world.

My particular concern in chapter 2 is to describe Batak demography, subsistence economy, and settlement pattern at the turn of the century. Whether my account applies equally well (or with equal error) to the Batak economy and settlement pattern at some other time in the past is a moot point. It is not my intention to present my account as some sort of timeless, “aboriginal” baseline from which the Batak departed only after millennia of stasis and isolation. Indeed, a second concern in chapter 2 is to explore the forces of change that had already shaped and altered Batak adaptation prior to 1880.

This provides the backdrop for chapter 3, which is a detailed account of how the Batak live today. I begin by examining the striking changes in Batak settlement pattern after 1880, as lowland colonization of Palawan progressed and as they added new subsistence activities or changed their emphasis on others. This is followed by an examination of the annual subsistence round today, using an array of quantitative data on contemporary patterns of mobility between various residential locations—settlement houses, agricultural field houses, forest camps—to establish the rhythm of economic life. Finally, I consider separately and in detail the various components of contemporary subsistence economy: shifting cultivation, collection and sale of forest products,

and wage labor. For each activity, I examine the characteristic patterns of time utilization involved and the typical caloric, protein, or cash returns.

The Batak's present-day subsistence stance exemplifies a type widespread among surviving Southeast Asian hunting-gathering populations, and in that sense, my account in chapter 3 is intended as a contribution to the ethnographic literature on the subsistence economies of such peoples. In my analytical emphasis, however, I depart from what I see as a common, but facile, assumption that the present-day “subsistence multidimensionality” of people like the Batak is evidence of their flexibility or adaptability. This is true of the Batak in the trivial sense that they have changed their use of time and resources in the face of changing circumstances, but such a characterization would divert attention from the distortions in Batak time allocation and resource use which are engendered by the political and economic pressures of a wider social system. This reasoning leads me to reject, for example, the view that Batak failure to farm more effectively stems from some covert cultural agenda, such as an alleged Negrito distaste for sedentary living or agricultural labor routines. Rather, I argue, continuing insecurity about land tenure and the threat of incremental alienation by lowlanders of any Batak agricultural improvements better explain the current state of Batak agriculture.

More broadly, however flexible or ingenious present Batak subsistence adaptation may appear, it is not oriented toward meeting some timetable or resource use optimal for the Batak alone but toward meeting the pressures and requirements of lowland Philippine society. The Batak do what they do because it is what they are allowed to do. Their subsistence system may seem flexible as a result, but, in fact, it is inadequate to their own subsistence needs. And while the Batak still survive, they are on the brink of physical and cultural extinction.

The evidence supporting this argument is presented in

chapters 4 and 5. Chapter 4 is concerned with adaptive difficulties at the population level. Based on a series of population estimates made since 1900, my own complete censuses of the Batak population in 1972 and 1980, and an analysis of fertility and mortality patterns, I argue that the core Batak population experienced a sustained decline from about 600 individuals at the turn of the century to less than 300 individuals in 1980. During this period, mortality was high at all age levels, and fertility was strikingly low. Women averaged only about four live births each on completion of their reproductive careers, not because they spaced their births but because many ceased childbearing altogether by their late twenties or early thirties.

Compounding (and in part concealing) the decline in the number of ethnic Batak was a dramatic increase, after about 1960, in the proportion of Batak who married outsiders. Indeed, by 1980, it appeared there would be few additional marriages between ethnic Batak. “Out-group” marriage, itself largely a consequence of prior depopulation and cultural disruption, has helped to stabilize the remaining population. But it has also accelerated the disappearance of characteristic Batak physical and cultural attributes; those who do remain are of increasingly ambiguous ethnicity.

Chapter 5 deals with the adaptive difficulties of individuals. The Batak have escaped the kinds of massive depopulating epidemics that have ravaged tribal populations in other parts of the world. But over time, small, localized epidemics of measles and influenza and a variety of chronic respiratory and gastrointestinal infections have taken their toll. I argue, however, that chronic undernourishment, rather than any unique genetic or physiological susceptibility, primarily underlies Batak problems with infectious diseases. A series of anthropometric measurements made over the course of a year show that many Batak are only at 70 to 80 percent of weight-for-height standards and, furthermore, that they undergo a famine season weight loss on the order of 3

percent. My interpretation of these data concurs with the appraisals of doctors and other trained medical personnel who have seen the Batak.

Taken together, chapters 2 through 5 document one hundred years of change in Batak demography and subsistence economy and, I believe, convincingly demonstrate that the Batak are in severe adaptive difficulty. Crucial causal links with respect to the behavior of individuals remain undeveloped, however. While such “involuntary” factors as high infant mortality rate and poor maternal nutrition help limit family size, some Batak deliberately restrict their own fertility and—the exigencies of poverty aside—are dilatory in caring for their living children. Again, even poor people are not helpless in the face of infectious disease, and the Batak's failure to mobilize the kinds of health and social support systems that are present among other tribal peoples must be accounted for. Similarly, although resource depletion and competition with neighboring peoples have certainly made the food quest more difficult (if the apparent ethnocentrism may be allowed here), the Batak could do better with their available resources.

These matters are taken up in chapters 6 and 7, wherein I relate the demographic and physiological evidence of adaptive difficulty (presented in chaps. 4 and 5) to wider patterns of social stress and cultural disruption attending the political, economic, and ideological intrusion of lowland Philippine society into Batak society. Sociologists and psychologists have placed more explanatory emphasis on the concept of social stress, and I begin chapter 6 by reviewing briefly the significance of this concept in these sister disciplines. In particular, I examine how the origins, mediators, and manifestations of social stress have traditionally been conceived, suggesting some modifications in these conceptual domains which make them more useful for anthropological purposes. I then describe how increasing stress levels have affected many traditional Batak social roles and relationships: those within domestic families, those between settlement neigh-

bors, and those between the Batak and outsiders. I support my claim of growing social stress among the Batak with comparative observations of stress in other tribal groups undergoing similar changes.

Chapter 7 is concerned with how stress adversely affects the Batak. I show how culture change and culture loss attending the partial incorporation of the Batak into lowland Philippine society have undermined Batak ability to cope with the (growing) stresses of everyday life. Distinguishing between social networks and ego resources for coping with life's everyday stresses, I argue that many traditional cultural beliefs and practices functioned to sustain such resources. As these beliefs and practices have declined, stress-coping resources and individual well-being have deteriorated apace. Thus, the demise of shamanistic curing ceremonies during the 1960s and 1970s reduced Batak ability to mobilize vital supernatural and social support in times of sickness. Similarly, cultural disintegration and an associated erosion of ethnic identity have undermined an important ego resource, self-esteem. I cite comparative data relating disruption of psychological coping resources such as self-esteem to low fertility, impaired recovery from illness, inadequate care of the young and sick, and disinterest in work and suggest that similar relationships may obtain in the Batak case. Batak, meanwhile, emulate the life-styles of neighboring lowland Filipinos, but they so lack the wherewithal that the major outcome, I show, is further erosion of their own social identities and the creation of still other patterns of stress.

Chapters 6 and 7 thus detail the ultimate consequence, for one people's adaptive well-being, of rising stress loads and, at the same time, decreased stress-coping capacity, namely, a perilous decline in individual and collective ability and motivation to cope with the exigencies of survival. These chapters support and flesh out, in effect, the popular notion that indigenous peoples can be so overwhelmed by contact with (and incorporation into) the outside world that they lose the will to live. [2]

Chapter 8 places my findings on a broader stage—anthropological concern with the circumstances promoting the survival of tribal populations as distinct cultural entities. Briefly examining a series of apparently successful cases of adaptation and survival of tribal peoples, I explore the role that ethnicity and culturally constituted patterns of motivation play in helping such peoples resist marginalization to wider social systems. This exploration leads me to the notion of a “healthy society,” one whose members possess sufficient resources to cope, individually and collectively, with the variety of threatening environmental situations posed by everyday life. A tribal people's resources for this endeavor may range from ancestral lands to curing ceremonies, but an underlying sense of ethnic identity everywhere imbues these resources with an overall coherence and thus helps to provide tribal peoples with a purpose in life. The familiar observation that contemporary tribal peoples somehow (like the Batak) lack motivation stems in part, I argue, from the vulnerability of tribal peoples' ethnic identities—and hence the vulnerability of their sense of purpose in life—to deculturating change.

2

The Batak as They Were

Palawan Island lies west and south of the main body of the Philippine archipelago, along a line running northeast from Sabah in the island of Borneo (see fig. 1). The fifth largest island in the Philippines, Palawan is home to three indigenous tribal peoples: the Palawan or Palawano, a shifting cultivation folk inhabiting the mountains in the south; the Tagbanua, another group of shifting cultivators inhabiting the riverbanks and valleys of the central mountains; and the Batak, a Negrito people inhabiting the north central part of the island.

The Spanish encountered Palawan in 1521, when the survivors of Magellan's expedition stopped there to seek provisions during their search for the Spice Islands. Based on his reading of Pigafetta's chronicle, Fox (1982:19) believes that the people they met may have been Tagbanua. In any event, their reception was friendly, and the Spanish apparently found food in abundance (Blair and Robertson 1903–1909, vol. 33, pp. 210–211). Spain, however, showed little interest in Palawan during its 350-year rule of the Philippines. Not until 1622, when five Recollect fathers reached the island of Cuyo, well east of Palawan in the Sulu Sea, did she attempt to garrison or establish missions in the region. There fol-

Figure 1

lowed sporadic efforts to extend Catholicism and political control of the island, particularly in the north. For the most part, these efforts came to nothing. Spain did construct a church and a fort at Taytay, a considerable distance north of the Batak. But until late in the nineteenth century, Cuyo Island, which had become the capital of Palawan Province, remained her only important outpost in the region.

More than lack of interest accounted for Spain's limited impact on Palawan proper: throughout most of her rule in the Philippines, Spain was locked in futile and costly combat with seagoing Muslims, who emanated from the sultanates of Sulu and Brunei, for political control of the more southerly portions of the archipelago, including Palawan. Despite numerous attempts, the Muslims never succeeded in capturing the fort at Taytay, but no Spanish outposts farther south on Palawan were secure from attack. The Spanish gained the upper hand in combat against the swift Muslim sailing craft only after 1848, when they acquired steam vessels (Saleeby 1908:221–223; Fox 1982:22). Even then, Muslims continued to raid Palawan's indigenous population for goods and slaves until the American occupation of the Philippines. Islam, too, retained its cultural presence in southern Palawan: the Palawano there show Muslim influence, and large numbers of Muslim migrants from Sulu and Cagayan de Sulu have settled in the region since the late eighteenth century (Conelly 1983:40).

By the midnineteenth century, some migrant lowland Filipinos were apparently already present in limited areas on Palawan's southern coast, on parts of the west coast, and in the extreme north. But only after 1872, when the town of Puerto Princesa was founded on a small, east coast bay on the middle part of the island, did Palawan become a destination for significant numbers of migrant lowlanders, first from Cuyo Island and later from throughout the Philippines. Even then, Palawan remained a little-known area on the periphery of Philippine economic and political life until well into the twentieth century (ibid.:39). In 1903, the total popu-

lation of Palawan Island was estimated to be only 10,900 persons (National Economic and Development Authority [NEDA] 1980); most of these were probably Tagbanua or Palawano. Today, Palawan remains extensively forested and sparsely populated, and it is commonly regarded as the Philippines' last frontier. But, like all frontiers, it is rapidly becoming settled. In 1980, the island's population was approximately 270,000.

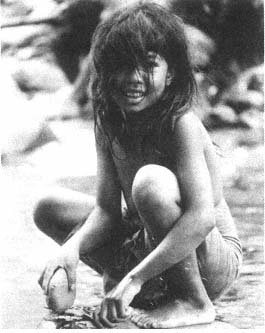

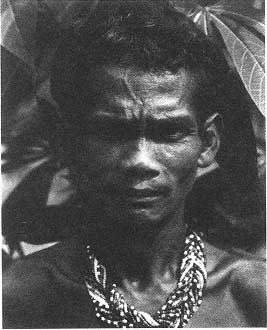

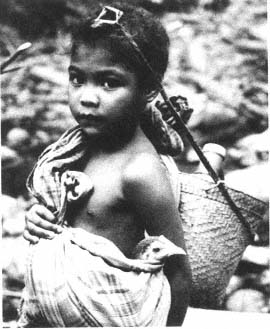

Of Palawan's three tribal populations, the Batak were always the fewest in number and the most localized in distribution. At the turn of the century, about 600 to 700 Batak inhabited a series of river valleys along a 50-kilometer stretch of coastline northeast of what is today Puerto Princesa City. As now, they closely resembled other “Philippine Negritos,” both in their mobile hunting and gathering lifeway and in the physical attributes—short stature, dark skin, and curly hair—that earned these distinctive-looking people their name.[1] Approximately two dozen ethnolinguistically distinct groups of such peoples are found in the Philippines, including the Mamanwa of Mindanao and a series of groups known variously as Agta, Ayta, Aeta, Ata, or Ati scattered widely in northern, eastern, and west central Luzon, the Bicol Peninsula, and the islands of Panay and Negros. Philippine Negritos, in turn, resemble other small, dark, hunting and gathering folk of Southeast Asia, in particular, the Andaman Islanders and the Semang of the Malay Peninsula. Collectively, “Southeast Asian Negritos” have long been presumed to represent the surviving remnants of what was once a more widespread and more racially and culturally homogeneous population (e.g., Cooper 1940; Fox 1952). Such claims remain speculative. A more recent, and probably sounder, view is that each group of Southeast Asian Negritos represents the outcome of long-term, local evolutionary development under similar ecological conditions (Solheim 1981:25; Rambo 1984).

Philippine Negritos have been unevenly studied. The best known ethnographically are those of Zambales in west cen-

tral Luzon (Reed 1904; Fox 1952) and the various Agta or Dumagat groups in northeastern Luzon (Vanoverbergh 1937–38; Peterson 1978; Griffin 1981). The Batak did not receive significant scholarly attention until after World War II. Charles Warren's fieldwork among them during 1950–51 led to a master's thesis (1961) and a series of publications (notably, Warren 1959, 1964, 1975). More recently, the Batak have been the subject of a doctoral dissertation by Rowe Cadeliña (1982).

I describe here the Batak lifeway as it probably was during the closing decades of the nineteenth century. The basis for my reconstruction is Batak oral history, comparative data on other, less disturbed Southeast Asian foraging populations, and the only two significant historical accounts of the Batak: a manuscript written in Spanish in 1896 by Manuel Venturello (1907), a member of the Puerto Princesa municipal council and a report by E. Y. Miller (1905), an American army lieutenant. I also make use of Warren's (1964) ethnography, which was based in part on these same sources. My purpose is not to determine whether in 1880 the Batak were “pure hunter-gatherers” (they were probably not). Rather, I want to establish two points: first, at that time, the Batak were still firmly committed to a hunting-gathering way of life in which other subsistence activities were recent or peripheral, and second, in 1880, they were still demographically, socially, and culturally intact.

My emphasis is on settlement pattern, subsistence economy, and those aspects of culture most closely tied to the business of making a living. Given the nature of my sources, my account must be largely qualitative, although I will hazard some quantitative estimates of those aspects of Batak adaptation of greatest comparative interest: local group size, frequency of mobility, length of workday. I have eschewed the temptation to report here any of the quantitative data (which instead appear in chap. 3) on such facets of the present-day Batak hunting-gathering economy as time allocation patterns or returns to labor at forest camps. For

reasons explained below, however “aboriginal” life at contemporary forest foraging camps may appear, data obtained at them are of doubtful value for purposes of reconstructing the past.

A Tropical Forest Foraging Adaptation

Traditional Territory

Palawan Island occupies a unique geological position in the Philippines. It lies at the northern edge of the Sunda shelf, separated from the main part of the archipelago by deep ocean waters but from Borneo by only 50 kilometers of shallow sea. When ocean water levels dropped dramatically during the Pleistocene glaciations, portions of the Sunda shelf were exposed as land bridges that connected Palawan to Borneo and thence to the Southeast Asian mainland. This circumstance explains the close present-day affinities between Palawan and Bornean fauna and the failure of a number of animal species (including some hunted by the Batak) to reach the remainder of the Philippine archipelago.

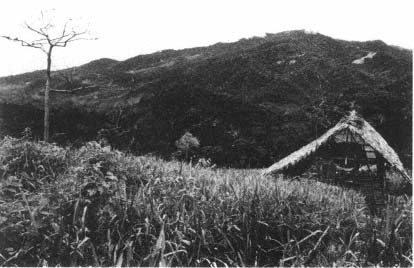

A chain of mountains runs the length of Palawan and is responsible for some marked climatic differences between the east and west coasts. Although the entire island generally has a June to December rainy season and a relatively severe January to May dry season, the western and northern parts of the island receive considerably more rainfall than the east coast, much of which is sheltered from the southwest monsoon. Indeed, the east coast of Palawan receives only about 1,600 millimeters of rain a year, making it one of the driest areas in the Philippines (Wernstedt and Spencer 1967:438). With regard to vegetation, such seasonally dry tropical environments contrast in important ways with humid tropical environments. In the humid tropics—roughly, where temperatures are consistently high and where average monthly rainfall is not less than 100 millimeters for any month of the

year—are found the tall, lush, and species-rich evergreen rain forests often associated with this region (Hutterer 1983:178). In those tropical areas affected by marked and prolonged seasonal droughts, however, as in that part of Palawan where the Batak live, forests are consistently reduced in height, density, and species richness. Paradoxically, seasonally dry forests generally provide more plant food for human consumption than do rain forests. The latter have little vegetation at ground level, most potential plant food being in the canopy. But seasonally dry forests typically have a variety of more accessible trees, shrubs, and vines producing carbohydrate-rich seeds, fruits, and tubers. Such forests also tend to have more clustering of individuals of the same species than is found in forests of the humid tropics (ibid.:180–181).

Because of the rainfall regime and the soil and topography, Palawan has only limited agricultural potential. Rivers are characteristically short and steep, and the coastal plains are generally narrow. The kinds of fertile, alluvial soils most favorable to irrigated rice cultivation are found in only a few coastal areas. In the hills and mountains, thin and relatively infertile sandy clays and clay loams prevail (Wernstedt and Spencer 1967:437–438). Cashew and other tree crops prosper in Palawan, however, and recent years have seen considerable government interest in developing the uplands through various sorts of agroforestry projects.

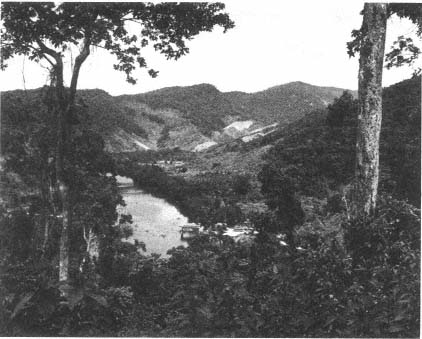

Figure 2 illustrates that part of the island inhabited by the Batak. The area is rugged and mountainous. In some places, the mountains fall directly into the sea; elsewhere, there is a narrow coastal plain up to a few kilometers in width. Nine successive valleys whose rivers empty into the east side of the island compose the principal homeland of the Batak. From south to north, these are the Babuyan, Maoyon, Tanabag, Tarabanan, Langogan, Tinitian, Caramay, Quinaratan (Rizal on some maps), and Buayan River valleys. Today, most of these provide the names for a series of lowland communities strung along the highway that winds

Figure 2

up the east coast of the island from Puerto Princesa City to Roxas. In terms of distance along the coast, Batak territory lies adjacent to a 60-kilometer section of coastline from the mouth of the Babuyan (58 km north of Puerto Princesa) to north of the Quinaratan. The coastline of Palawan makes a sharp turn between Langogan and Caramay, however, and the headwaters of the first five of these east coast river valleys are, in fact, all found on the various slopes of Cleopatra's Needle (1,593 m), a prominent cone-shaped mountain lying in the center of the island.

Some early sources report that Batak also traditionally inhabited a small area of the west coast of Palawan, on the Caruray River (see fig. 2). Indeed, much of Venturello's account derives from firsthand observations made during “the six years that [he] lived in Caruray at a place near the Batacs” (1907:549). Miller's oldest informants even claimed that the Batak of the Caruray area “are the ones from whom the [Batak] tribes of both coasts sprung” (1905:186). In contrast, Conklin's (1949:272) map of the distribution of the Batak shows them limited to the east coast, and I could find no contemporary Batak residents in the Caruray area. My own informants, however, agreed that Batak did once inhabit the Caruray area and that the present-day “tribos” there, an unusually dark-skinned folk known as “Caruraynen” and today regarded as a kind of Tagbanua, are of Batak descent. My own interpretation (in chap. 4) is that the Caruray River valley was once an alternative residence for the group of Batak who traditionally inhabited the Buayan River valley (fig. 2), from which it is easily accessible. The “Buayan” Batak, now extensively intermarried with Tagbanua, share some physical and linguistic features with the Carurayan “Tagbanua,” with whom they in fact claim some affinity.

Excluding the Caruray region as anomalous, a crude estimate of the total area of aboriginal Batak territory may be obtained by totaling the separate areas of the nine successive east coast river valleys, following all drainages back to the spine of the island or to where they abut the watersheds of

adjacent river valleys. The area thus obtained (shaded on fig. 2) is approximately 1,200 square kilometers, and it appears that despite its considerable size, the Batak were thoroughly familiar with it. Present-day Batak preserve remarkable inventories of place-names to identify various points on the streams and watersheds of their respective river valley. For example, along the meandering, 36-kilometer main course of the Langogan River, between its mouth and its head-waters at the spine of the island, Batak identify 90 distinct locations. More than 300 other features—mostly tributary streams, forest zones, and ridge tops—are identified elsewhere in the valley. Thus, a total of about 400 features are identified across the entire river basin, an area of approximately 240 square kilometers, for an average of about 1.7 named features for every square kilometer.

Settlement Pattern and Social Organization

At any one time (or even in any one year), of course, the Batak occupied or visited only a fraction of their territory. They were a highly mobile people, however, broadly dispersed across the landscape in a series of transitory forest and riverine camps of constantly shifting size and membership but always consisting of a cluster of related, nuclear families (Warren 1964:89). As with other bilaterally organized peoples in this part of the world, nuclear families are the basic Batak production and consumption units. Such families make their own decisions concerning residence, activities, and relations with other people, and each is potentially self-sufficient economically, for a man and woman working together can obtain all the necessities of life (Estioko-Griffin and Griffin 1981:98; Endicott and Endicott 1983:5).

At the close of the nineteenth century, approximately twenty to fifty Batak families were associated with each of the river valleys that composed their traditional territory. The inhabitants of each apparently saw themselves as some-

what different from the Batak of neighboring river valleys. How extensive such differences may have been is difficult to reconstruct, but a suggestive comparison may be drawn with the socioterritorial organization of the Agta of northeastern Luzon and the Batek of the Malay Peninsula. Both are foraging peoples resembling the Batak, but their aboriginal settlement patterns are still relatively intact. The Batek reside within a nesting series of socioterritorial units, each more inclusive than the preceding one. The everyday residential units of family and camp fall within wider “river valley groups” and “dialect groups.” When a dialect group spans several river valleys, differentials in social interaction are such that subtle cultural differences arise between valleys, as with respect to particular religious beliefs (Endicott and Endicott 1983:9–11). Agta settlement pattern is much the same (Rai 1982:61–83).

It appears that a greatly atrophied version of what was once a comparable form of socioterritorial organization still persists among the Batak today. Residents of the six southernmost river valleys, for example, share a single dialect, while two other dialects (one now moribund) are indigenous to the remaining three river valleys. It is also said that only in two river valleys did Batak ever practice their distinctive honey-season ritual.

A headmanshiplike institution may have given some political expression to the feelings of social and cultural solidarity shared by residents of the valley. Certain older men, by virtue of personality, emerge as natural leaders and become the focus of a residential aggregate. The opinions of such individuals are respected but are not binding; the others are free to argue or to leave (Estioko-Griffin and Griffin 1981:98). The degree to which such leaders traditionally influenced the affairs of Batak in an entire river valley (rather than day-to-day residential clusters; see below) is unknown. Warren does speak of a Batak “kapitan” for each river valley, but Batak political organization has been changed greatly by

extensive borrowings from the Tagbanua and incorporation into the modern Philippine political system (Warren 1964:93–95).

Beyond any more structured social or cultural differences among Batak inhabiting different locales, each individual Batak has a powerful emotional attachment to the particular river valley in which he or she grew up. Similar attachments have been reported for the Agta (Griffin 1981:32) and the Batek (Endicott and Endicott 1983:5), and they are rooted at least in part in the practicalities of everyday life. Typically, one's closest kin are found there, and there, too, one gains an intimate knowledge of the terrain and the location of important subsistence resources. Not surprisingly, in these circumstances, most nuclear families ordinarily confined their movements to their river valley. Most marriages, furthermore, were between inhabitants of the same locale—a practice that, in turn, helped to maintain subcultural differences among river valleys. To be sure, marriage between Batak inhabiting different river valleys also occurred regularly and ensured that most Batak had kin in many locales. But the Batak were isolated enough and their numbers (both overall and within river valleys) were robust enough so that they had little opportunity, inclination, or need for marriage with members of other ethnic groups. They were, in short, still self-recruiting. As recently as 1950, when demographic disruption was already extensive, Warren observed that the Batak “seldom married Tagbanua” and that out-group marriage in general was only “occasional” (1964:65).

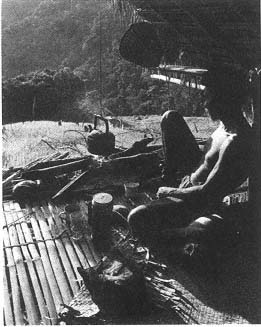

Whatever similarities or communities of interest all of the Batak inhabiting a single river valley may have shared, they did not ordinarily reside together. From the standpoint of the everyday business of making a living, the most important aspect of settlement pattern was the smaller living group in which the Batak went about their day-to-day affairs. Nuclear families may have been independent production and consumption units, but cooperation in production and sharing in consumption are central characteristics of hunting-gathering

societies. Among the Batak, the principal social organizational context for economic cooperation and food sharing was the camp, a temporary residential aggregate sometimes consisting of only two or three nuclear families, sometimes many more.

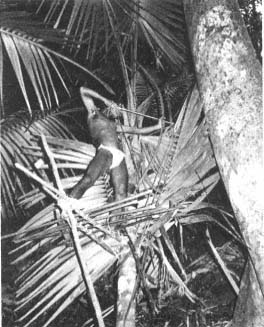

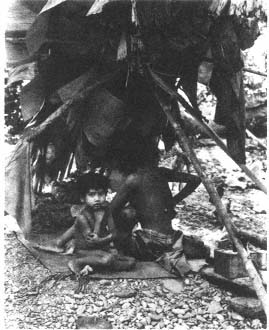

A Batak camp consists of series of leaf shelters, each with a hearth in front. The shelters are cone-shaped dwellings constructed by placing palm fronds or wild banana leaves over a triangular framework of three or four poles that are positioned on the ground in a semicircular fashion and tied together near the apex with bark or rattan. Each nuclear family has its own shelter and hearth, as do any widows, widowers, or (at times) adolescents living in camp. The shelters are at varying distances and randomly located with respect to one another. Fairly steep slopes are sometimes favored, in which case simple floors are constructed. Camps can be located almost anywhere but are always near a water source, whether a riverbank, stream, or seep. They may also be located under rock overhangs (leaf shelters are not entirely waterproof) or on tops of boulders or rock outcroppings above streams (to escape mosquitoes and other pests).

Camp size and duration varied with resource availability, season, and inclination. At times, it was said, the entire population of a river valley—as many as forty families—would camp together. But more common, apparently, were extended family clusters of two to five households. Unfortunately, none of our turn-of-the-century observers of the Batak had much to say about settlement pattern. But the Cummings expedition of 1911–12 did report that the Batak lived in groups of two to three households (Field Museum 1983). Also, Warren believes that the Batak lived in small bands until the end of the Spanish era. He reports that even in 1950, and when the Batak were not at their (recently organized) settlements, they were dispersed in “highly transitory” groups of ten to twenty individuals (Warren 1964:89, 1975:68).

After two or three weeks, it is said, a group of Batak

camped at a particular location would deplete local resources or tire of the area. They would then move elsewhere in the forest and establish a new camp. This memory estimate of past forest camp mobility, equivalent to about 17 to 26 residential moves per year, is consistent with ethnographic observations of other, more isolated Southeast Asian hunting-gathering populations. Rai observed local groups of Agta to change residence 20 times per year (1982:105–107), and Kelly, using data obtained during the 1920s, estimates that Aeta bands shift residence 22 times annually and Semang bands, 26 times annually (1983:280–281).

The Batak deployed from such camps to search for food. A few subsistence activities—fish stunning, communal pig hunts—involved all camp members in a common effort. Most subsistence activities, however, were conducted by smaller task groups, formed according to inclination and the activity at hand. Thus, a group of three women might go off to fish or to dig tubers or two men might go in search of honey. In this fashion, men and women came and went throughout the day. Any adults remaining in camp would look after any children who had been left behind (Endicott and Endicott 1983:7–8).

As food was brought into camp, it was shared with others. While food sharing was a central aspect of camp life, it was not done indiscriminately. Just how much food sharing occurred one hundred years ago is, of course, a moot point. The following description of food sharing in contemporary Batek camps is strongly reminiscent of the way Batak talk about food sharing in the past.

Meat and vegetable foods are shared according to the same principles: that food is shared first with one's own children and spouse, then with parents-in-law and parents, and then with all others in camp equally. The result is that small amounts of meat, such as a small bird, and vegetables may not extend further than the immediate family. Usually, however, meat comes into camp in the form of monkeys or other

animals large enough to ensure that all families in camp receive a share. Each household can normally procure enough tubers in a working day to last it a day or two, depending on the size of the family. Despite each family's having an independent supply of tubers, plates of cooked tubers are shared with each family in a small camp or with an equivalent number of families in a large camp. In times of need a family without food thus receives a share of vegetable foods, and in times of plenty the sharing takes on the appearance of a ritual exchange. (Endicott and Endicott 1983:8)

Resource Utilization

The Batak traditionally exploited food resources in three major resource zones: the forest, freshwater rivers and streams, and along the seashore. The first two zones were the most important. Tropical forests contain numerous useful plants and animals, and rivers provide a variety of protein foods. Ecozones in themselves, the latter also break the closure of the forest, which results in a distinctive growth of herbaceous vegetation at river's edge (Rambo 1982:264). The Batak were cut off early from effective access to the ocean (see chap. 3), and none of the historical sources mentions any Batak use of coastal resources. Many of the adults still living today did periodically visit the seashore during their youth to fish in the surf, collect clams, or make salt. But based on the Batak's own version of their past, foods obtained from the ocean, tidal flats, coral reefs, or strand were never of more than secondary importance. Indeed, Warren (1964:46) was told that in the distant past, the Batak did not fish in the ocean at all. The possibility that the Batak once extensively utilized coastal resources cannot be ruled out entirely, however; reef shellfish, for example, are important to Agta along the Pacific coast who often camp at river mouths (Griffin 1981:32, 35).

Tables 1 and 2 show the principal animal and plant foods the Batak say they once utilized. Much could be said about

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

these, but here I will only discuss the more important ones and describe the ways they were obtained, loosely distinguishing among gathering, fishing, and hunting. For stylistic convenience, I write partly in the present tense, but it should be noted that I am attempting to describe the subsistence economy that may have prevailed one hundred years ago.

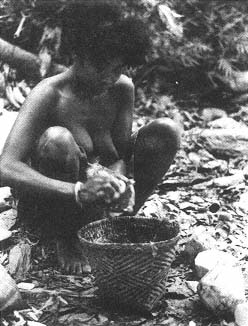

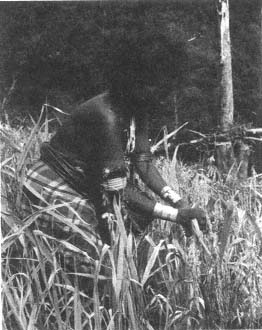

GATHERING . Wild yams and wild honey once provided most of the carbohydrates in the Batak diet. Approximately eight species of yams or other tubers were consumed. Each is seasonal and favors a particular environmental zone, where there is considerable clustering by species. The seasons of each species do not coincide, however; nor do their characteristic microenvironments. Thus, some yams were always available somewhere, although it was necessary to search for them. When and in what numbers harvestable wild yams will be found is somewhat unpredictable, but the Batak return annually to some areas known to have good stands. In general, though, yams were like other subsistence resources: they were sought and obtained by forest camp task groups going out in different directions over a period of time until the readily collected supply was exhausted. Small groups of women, together with their children, normally gathered yams, although men dug for them as well and helped carry loads back to camp (Endicott and Endicott 1983: 12–13).

Kudot and abagan were the two most important wild yams (see table 2). Kudot is available from July through May. Its shallow, large tubers are easily dug, but they contain a poisonous alkaloid, dioscoreine, and must be peeled, thinly sliced, soaked in water, and rinsed before cooking and eating. This leaching process takes approximately three days, although it can be shortened by using seawater instead of fresh water. Abagan is available from September to July. While it may be roasted or boiled immediately, without processing, and is in fact quite tasty, its long, slender tubers grow deep in the ground and can be difficult to dig up.

The Batak collected the honey of five species of bees

during a honey season lasting from March to September. Seasonality in the availability of honey reflects seasonality in the food supply. The Batak identify about fifteen species of trees that flower between March and August and are thus important to bees. Honey collecting is a male activity, normally done in two steps. Suitable hives first had to be located, and to this end, men usually went out alone, walking transects in the forest while looking and listening for bees. (Of course, they also discovered hives in the course of other subsistence pursuits.) Those who were merely searching for hives often left their collection equipment behind, on the grounds they would not find a hive anyway or the hive they discovered would be so large that assistance would be needed or so small that collection would have to be postponed. If the finder of a hive did not plan to collect its contents immediately, he left a marker nearby to inform other would-be collectors that this particular hive was claimed.

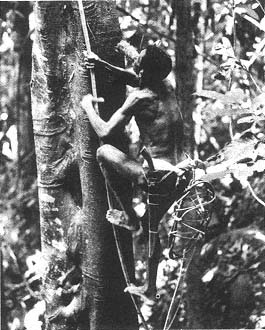

Collection of honey from a previously located hive was normally done by a task group of two or three men assembled by the finder. A large and relatively aggressive bee (Apis dorsata? ) provided the bulk of the Batak's honey supply. This bee characteristically builds a large comb on the underside of a seemingly inaccessible tree branch high in the forest canopy. The Batak, however, are skillful and daring tree climbers. If the main trunk is sufficiently gnarled or covered with vines, a man simply climbs it, cutting steps as necessary. Younger or lighter men may dispense with climbing the main trunk altogether, instead climbing the latticelike lianas that hang from the canopy to the forest floor. Once in the treetops, the Batak easily move from branch to branch and even from tree to tree. The necessary collection equipment is prepared in advance. A small, smoking torch of bark or bark cloth is used to drive the bees off the comb. Pieces of comb are then broken off, wrapped with the paperlike covering of a palm trunk, placed inside a container woven from rattan, and lowered to a companion waiting on the ground. The collectors first relax and eat their fill. Comb rich in larvae is

wrapped in tree leaves to take back to camp. The honey from the remaining comb is squeezed into basins of palm or tree bark, which are, in turn, emptied into bamboo storage containers. Up to 15 liters could be extracted in this fashion from a single large hive.

Other important gathered foods included palm shoots and rattan pith and various kinds of greens. Like wild yams, many of these supplementary vegetable foods are seasonal and irregularly distributed. Some of these foods could always be obtained in the vicinity of a forest camp, however. Finally, although the Batak recognize a large number of edible fruits, only a few, such as the wild rambutan, apparently were of more than secondary or incidental importance in the diet.