Preferred Citation: Sobin, Gustaf. Luminous Debris: Reflecting on Vestige in Provence and Languedoc. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1999 1999. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5j49p06s/

| Luminous DebrisReflecting on Vestige in Provence and LanguedocGustaf SobinUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 2000 The Regents of the University of California |

For Esther & Gabriel,

With love

Preferred Citation: Sobin, Gustaf. Luminous Debris: Reflecting on Vestige in Provence and Languedoc. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1999 1999. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5j49p06s/

For Esther & Gabriel,

With love

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

If any of the essays that follow help readers come to kindred realizations, then the limited ambitions of this book will have been fulfilled. I feel especially grateful to Eliot Weinberger, who first encouraged me to undertake such a project, and to the numerous archeologists and prehistorians of Provence who have been boundlessly kind, generous, and disinterested in helping me along my way. A number of the essays are specifically dedicated to those who made that "way" such an enlightening one.

GUSTAF SOBIN

INTRODUCTION

There's a breeze blowing through my work hut this morning. To keep my papers from flying about, I use, as a paperweight, a Neolithic stone axe head that I found years ago in a neighboring orchard. The axe head, slender as a trout and streamlined as a Brancusi sculpture, sits somewhat ponderously on top of a thick sheath of rattling white pages. The axe head is over four thousand years old. As for the rattling white pages, they're little more than so many day-by-day bits of scribble, fragment, outline: the disposable draft that authors inevitably accumulate. It's reassuring, of course, to see something as durable as a prehistoric artifact perched on top of one's own ephemera. Reassuring to see the past, in a sense, come to anchor all one's own, provisional, notation. Living as I do in a Provençal landscape rich with memento, with the materialized memory of so many past cultures, I've grown increasingly fascinated through the years with all the flint, ceramic, and serpentine that makes its way to the surface. Makes its way, fresh as dreams and remote as those founding societies, out of all that compounded subsoil.

The artifacts "speak" if we know how to "listen," if we learn how to interpret the operative details by which each might be identified. In this sense, the artifacts themselves are like words. They only await translation. In the essays that follow, I've attempted to translate a number of such words, phrases, relevant passages. I've drawn my materials from exactly those objects, those instances that I consider most meaningful in terms of our own particular existence today. In this respect, I am often reminded of a phrase of Roland Barthes. In it, Barthes describes his hesitation at the entrance to a Parisian cafe as he speculated whether the cafe contained anything "existential" at that given moment. I've chosen my materials herein exactly on that basis. What can a svelte, "willow-leaf" arrowhead tell us about ourselves? How do the ash grey potsherds of an Etruscan jug reflect—like opaque mirrors—some hidden aspect of our very existence? What exactly does the lunar crescent of a Bronze Age earring have to say?

I'd begun, years earlier, combing the surface of orchards, vineyards, wheat fields: whatever ground was subject to periodic plowings. The best season, of course, is winter. With the earth supple and the rainfalls abundant, the artifacts virtually ooze to the surface. I came to know whole patches of ground in which I could expect to find, say, traces of an outdoor Neolithic atelier (scrapers, blades, burins). Other spots secreted hunting tools (lance heads, javelin points), still others yielded a bounty of tiny, square-shaped, Gallo-Roman bath tiles—tesserae . Often these sites were no more than twenty or thirty meters in circumference, almost always within easy reach of still-available water sources and, invariably, sheltered from the all-dominant mistral. Flint, potsherd, the blue calcined bone of Neolithic game animals—all would abruptly disappear the very instant I stepped into the full force of that near-mythical air current. So many thousands of years after the fact, all vestige suddenly would vanish.

In only an instant, I would have stepped from the realm of "culture" to that of "nature": from artifact to scrub oak.

There's scarcely a moment of prehistory, protohistory, or early recorded history that hasn't left its trace in Provence's richly receptive earth. Often lying in as many as fifteen successive layers, these deposits range chronologically from the seasonal abodes of the earliest Paleolithic hunters to those of one's own vegetable garden, rife with the cracked faience and chipped marbles generated by one's own family. Between these two extremes, virtually every moment in human evolution has left its mark. From a bone bracelet of a Neolithic archer to a tiny bronze coin, the viaticum , once wedged between the teeth of a medieval ecclesiastic, history in these parts comes to illustrate itself.

If I myself have never dug—never participated, that is, in a proper, archeological expedition—I've spent a good deal of time practicing a parallel discipline, something I can only call "archival excavation." I've worked my way through the impacted tumuli of endless field reports, the theses (both published and unpublished) of doctoral candidates in archeology, the recorded addresses of prominent prehistorians at annual congresses. In every case, I've done nothing more than dig, scrape, sieve for the luminous detail. Indeed, I've had no further ambition as I rummaged through books, brochures, penned memoirs, and electronic printouts touching on everything from Mediterranean fossil pollens (palynology) to microtoponyms (paleo-linguistics) than the unearthing of those luminous details, those exemplary moments. In doing so, my research reading came to complement my field work: the archiviste , in a sense, elucidated the flaneur . Both, however, had been searching for exactly the same buried properties: the power—inherent in certain objects, certain instances—to generate reflection, reference, to serve as a kind of resuscitated mirror. Ob-

scure, usually encrusted, more often than not illegible, these artifacts nonetheless establish points from which we might situate our own existence today. Yes, across the millennia, the incised pictograph, say, of some protohistoric culture might serve potentially as a station, a vestigial marker for determining who, what, where we are, ultimately, at this very moment. "Existential," indeed. For the past, properly interpreted, clarifies the present: gives us—on occasion—startling glimpses of our own reality.

As we approach the end of yet another millennium, the insights that those glimpses provide grow all the more meaningful. Adrift in a world of semiotic vacuity, lost to ourselves in the midst of so much electronic overload, we've begun, as if intuitively, haunting museums, consulting archives, sifting through the apparent detritus of long-ignored vestige. Here in Provence, for instance, each village has generated its own historian; each dilapidated roadside shrine, its own restorer. In default of a viable present, we've come to valorize the past as never before. Propelled forward, we've turned, quite manifestly, backward, looking for the signs, signatures, and substantiating echoes of a world that underlies our own.

Each of the essays that follow enters, in varying degrees, a dialectic between those two orders of time. For myself, at least, the past per se holds little interest, and the present offers only the profound malaise of a culture increasingly devoid of the protocols of self-reflection. I've taken complete liberty in selecting, at will, specific objects, locations, and instances out of the past on the sole basis that they might serve, no matter how tenuously, that very dialectic. Nothing mattered in my choice of materials but the echoes, the mirroring images they might provide, but the reverberations they might create.

The essays open with the study of a tiny Paleolithic windbreak, four hundred thousand years old, and they end with the examination of an aqueduct

dating from the time of Claudius in the first century A.D. The essays are laid out in chronological order, although they make no attempt to "cover" that vast expanse of time. To the contrary, each represents nothing more than a brief aperçu —an exemplary moment—in that massive unraveling. The present volume spans a period from the outset of civilization to the Latinization of southern Gaul and covers an area approximately that of Roman Provincia, a vast administrative territory constituted by Augustus in 28 B.C. It includes a better part of what we've come to know today as southeastern France. Having lived in this area over the past thirty-five years, I've become, naturally enough, increasingly aware of its immense historical heritage, its vestigial wealth.

It is neither history nor vestige, however, that one first encounters upon arriving in Provence, but landscape, windscape. The wind is everywhere: in the twisted anatomy of the trees that one perceives in Van Gogh's paintings, in the architecture of its farmhouses that appear to crouch, even cower, against the long winter onslaughts of the mistral, in the delicately terraced olive orchards that face, resolutely, downwind. Downwind, too, lies the sun, that vast Mediterranean medallion. This very sun, I learned almost immediately, brings the almonds to flower in mid-February and the earth to crumble each August to a thin, insidious, funereal dust. It's the poignant world of Provence lying before one's eyes that one first encounters upon arriving. Faced with so much abundance, so much fruit and flower and golden, lichen-struck limestone, it's difficult to believe that this world conceals yet another beneath. That the lateral plane of our perceptions, in all its magnitude, keeps us from a deeper, more arcane set of cognitions below. That a vertical reading might indeed be possible.

There's a need today, perhaps as never before, to reestablish contact with that verticality: to feel ourselves rooted, not merely to the past in general but to our own specific moment within the past's tiered continuum. There is a need,

in short, to situate ourselves in regard to our own evolving. Living as we do upon the uppermost layer of a profound compilation—one, that is, of wind, shadow, of voices buffeted by other voices—we need to feel that this residency has been "underwritten" by antecedents: that we, the living, are continuously accompanied by the presence, no matter how remote, of predecessors. That we're not, finally, alone.

PART I—

SILEX

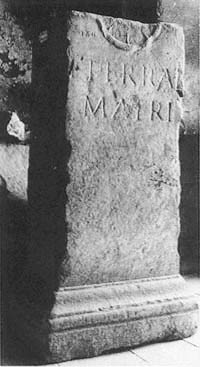

Terra Amata

The beach cobbles lie there in little unruly heaps. Indeed, nothing seems to indicate any inherent arrangement in the way the stones lean one against another, as if toppled, at odd, apparently haphazard angles. There's nothing whatsoever to tell us that they'd been deliberately laid into place, over four hundred thousand years earlier, by Paleolithic hunters in a pathetic attempt to shield their pit fires against the high prevailing wind overhead. Nothing indicates their veritable nature but the fact that the cobbles themselves—loosely arranged in vague crescents, in curves no more than ten centimeters high and fifty centimeters wide—all face in a north-northwesterly direction. All happen to face, that is, the all-dominant, all-determinant air mass of the mistral.

We look on, amazed. Ours? we might ask ourselves. Really ours, these vestiges? The mark—no matter how makeshift—of some distant predecessor? Living as we do under one wind or another, but in the shelter of heated, heav-

A four-hundred-thousand-year-old windbreak.

Photo courtesy Henry de Lumley, Musée de Terra Amata, Nice.

ily insulated houses, we look on, amazed by the fat pebbles in this archeological resuscitation, struck by the enormity of so much scant evidence.

Discovered quite by chance in excavating the foundations for a high-rise apartment house in the suburbs of Nice, the site of Terra Amata has given us a brief but luminous glimpse into a thoroughly obscure period of prehistory.[1] The ancient site lies underneath ten meters of rubble, marine deposit, and aeolian sedimentation. Despite everything we've learned about Terra Amata itself—it was occupied on a seasonal basis by itinerant bands of Acheulian hunters (usually in late spring or early summer, according to pollen analyses

of the subsoil)—we're left with little material evidence regarding the hunters themselves. We have, of course, their artifacts. We even have an area that the archeologists have clearly identified as a worksite, within which the Acheulians would crack open the quartzite beach pebbles and create, with the constituent parts, their implements. But what of the hunters themselves? What of their size and physiognomy, not to mention their rites, their traditions, their Weltanschauung? Of these, nothing remains. Nothing but a small patch of barren earth at the very center of the worksite. There, surrounded by broken bits of beach pebble, in an area that the archeologists have described as "sterile," the tool makers must have squatted, chipping away at those round, ungainly volumes. Nowhere, in fact, is their presence at Terra Amata more apparent than in this manifest absence, this tight, earth-beaten patch of pure lacuna.

We're left, as ever, with residue, with the little that remains. In the Lower Paleolithic, this never constitutes more than a few scattered artifacts: traces of Homo faber 's attempt to survive an essentially hostile environment. So we return, over and over, to those piled cobbles, those pathetic little windbreaks, no wider than one's spread fingers and not much longer than a forearm. For these, unmistakably, were theirs. Cobble over cobble, these were what the hunters assembled for the sake of protecting the quick little scarves of their fires, the scavenged meats that they cooked, over four hundred thousand years ago, in the scooped hollow of the sand dunes. These were the tiny, fortuitous arrangements they made against the flat, lateral pour of that indomitable air current.

The mistral is still blowing. As we leave the museum in which the excavation has been meticulously preserved, we're struck by a blast of that blue air. Through the streets of Nice, the same wind blows unabated. We watch it catch, now, in the awnings of the outdoor cafes and billow through the taut canvas of the brightly striped beach cabanas. For us, of course, it's no longer an is-

sue. We've long since learned how to shelter ourselves against every natural element; even more, we've learned how to harness those very elements to serve our own, ever-expanding needs. The wind—after how many hundreds of thousands of years?—rarely affects our lives. Like one of our own mass-produced appliances, we too have grown "windproof."

What, though, about those fires, we might ask? Those fires within? The subtle little flames each of us covets, not in the scooped hollows of a beach, but in the chambers of the brain or spirit or wherever we'd locate that tiny, flickering, unsubstantial glimmer that we've equated with life itself? The glow, say, of an early intuition? Or the sputtering embers of some still resilient memory? Are these fires any less exposed now than they were then? Any less vulnerable? And those cobbles, our cobbles, what we've laid into place along the rim of our consciousness in an unending effort to protect that fire, that glow, those embers: are they, in effect, any less provisional?

The wind today is still blowing, both inside and out. And if, at Terra Amata, we've lingered so long over such seemingly inconsequential artifacts, it's only because we have recognized—in cobble after teetering cobble—the extreme fragility of our own existence, displayed in paradigm. Found, among so much brute material, metaphor befitting our own human condition.

Reading Prehistory:

The Search for Antecedents

What characterizes humankind is our ability to evoke absent objects; to re-present them mentally.

Georges Sauvet "Rhétorique De L'Image Préhistorique," in Psychanalyse et Préhistoire

In the beginning was the eolith. So, at least, we're told upon opening a dense introductory manual to prehistory. Eo for dawn, lith for stone: in the beginning, at the outset of humanity, came the eolith, the dawn stone, a heavy pebble that's remarkable for nothing but the apparent absence of any distinguishing characteristics whatsoever. Yet there it is, described, analyzed, even pampered—for all its anonymity—as our very first artifact. Ours, we find ourselves asking once again? Living as we do at the far—the opposite—edge of civilization, we look back and wonder. Ours, those cobbles? Those round, nondescript volumes, scarcely chipped about their contours and subject to endless doubt and speculation by the paleontologists themselves? Yes, we wonder. For, at the very start, nothing can differentiate a pebble naturally fractured by intense thermal change from one deliberately crafted. Yet it's exactly there, at that very point, in that precise instant of deliberation, that that virtual figure, Homo habilis , evolves into Homo faber , the artisan. It's the inaugural gesture, the first irrefutable mark.

We read on. We're anxious for signs, indications, for some founding echo to our all-too-precarious existence, our so-called being here. Aren't we always, indeed, on the lookout for some kind of substantiating proof? Searching for antecedents as we enter, deeper and deeper, into the obfuscations of our own present? Archeological typology, we quickly learn, allows us to associate an artifact with a particular level of human development: to correlate, say, a chipped pebble with the cubic dimensions of a human brainpan; to affirm that such-and-such had been fashioned by so-and-so. Us, though, we ask ourselves? Really ours, these ancestors? we go on asking, incredulous over so much dubious relic, so much scarcely articulated rock.

Come, now, the first unquestionable "pebble cultures." Comes that of the Oldowan, 1.75 million years ago, with their archaic handaxes chipped in two directions. Here, at last, we can begin to recognize a logical design, a pattern, repeating itself in the midst of the mineral: a frequency which constitutes a human signature. In the Quarternary (beginning as much as 2 million years ago, according to certain estimates), the ice cap has come to cover nearly the entire continent of Europe. Adapting to this cataclysm, a new creature evolves. In the celebrated formula coined by Linnaeus, this hominid, "loquax, bimanum, erectum, " never stops developing as a rational animal. Page after page, millennium after millennium, we follow this creature's catatonically slow evolution as it manifests itself in its lithic industry. A third chip here, a fourth chip there, and the Oldowan handaxe gradually turns into an oval- or pear-shaped tool, roughly worked on two surfaces. Now even an untrained eye can recognize the handicraft involved. One culture succeeds another: the Acheulian, we're told, follows upon the Abbevillian, 1.5 million years ago. And, as it does, the handaxe grows thinner, finer; its pressure-flaked edges become ever more masterful. Archeologists have come to nickname these implements limandae

after their svelte, fishlike appearance. Tens of thousand years had to elapse, however, for this evolution to occur. We find ourselves, as ever, confronted with the incommensurable.

Concurrently, we're led through a succession of glacial expansions and interglacial contractions—all, of course, phases of that single, overriding epoch: the Quaternary. These phases have each been given the sharp, Teutonic place names of their alleged points of origin. Mindel, Riss, and Würm, for instance, are all affluents of the Danube. On the other hand, the cultures affected—determined—by these glacial fluctuations have each been named after the archeological sites far to the southwest with which—in terms of cultural evolution—they've been associated. Abbeville, Chelles, Saint Acheul, Le Moustier, La Madeleine are but a few such eponyms. Our familiarity with those places (all in France) or, simply, the lilt of their names brings us no closer, however, to those lost cultures. To the contrary, a kind of desolation increasingly sets in as we read on. A jaw bone, a few teeth, a crushed femur: are these really our vestiges? Our biological remains?

Here we're at the mercy of not only the archeologists, but a whole army of specialists, each qualified in some particular area of prehistoric research. The paleogeologists, readers of rock and rubble, can determine exactly how and when a particular cobble, for example, took on the shape that it did. By its striations alone, these specialists can tell us whether the cobble in question has been exposed to sea, wind, fire, glacial pressures, or solar heat. Equally as well, they can interpret river deposits, analyze loess—a volatile, wind-driven sediment—or the solifluction effect on any particular gravel bed. As we read on, though, we seem to be going further and further astray in our search for antecedents, for traces of some human determinant with which we might, even tenuously, identify. And although we've just been informed that a strict cor-

relation exists between, say, sea levels, glacial relics, and human artifacts, we feel, if anything, more removed than ever from any brief, albeit ephemeral, instance of self-recognition.

The paleobotanists, curiously enough, lead us even further astray. Prying fossilized pollen loose from the same stratigraphic layers as those in which worked tools or human bones have been identified, they relate one form of extinct life to another. More desolate yet, we listen as they tell us, for example, how deposits of a certain microscopic marine creature—the radiolarian—accumulating at a rate of one centimeter per millennium, constitute a perfect means of determining a particular moment in human evolution. The moment can be "located," we're told, in relation to the level of alluvial accretion in which it occurs.

Where are we though, we're forced to ask ourselves? Reading as diligently as we can, chapter after chapter, glaciation after glaciation, don't we run the risk of falling half-consciously into the chasms of prehistory itself? Slipping between two pages into some dismal abyss? Finding ourselves smothered by so many concretized blankets of sediment, glacial debris, stalactitic drippings? There's little, indeed, to retain us. In default of that founding echo, there's little to reassure us that here , in fact, is still here . The discovery of a skull—irrefutable evidence, we're told, of a new level in evolutionary development—does little to allay our anxieties. No, we could go on falling, readily enough, through so many pages of so-called substantiating evidence, conclusive fact. Quite clearly, the arrival of Homo neanderthalensis does nothing to help. With their low foreheads, massive, overwhelming brow ridges, and stunted chins, they bear, indeed, scarcely any resemblance to us whatsoever. And even if the archeologists are quick to praise the considerable technological advances made by this predecessor, it's virtually impossible—in an age of genetic research

and interplanetary exploration—to appreciate those advances to their fullest. These hominids—born, we're told, in the relatively temperate climate of the third interglacial period, rife with elephant, rhinoceros, and hyena—came to acclimate themselves to the gradual arrival of the last glaciation. Driven by severe cold into caverns, they adapted their lithic industry accordingly. If the aboriginal handaxe (beginning with the eolith and culminating in the elegance of the Acheulian limanda ) had been perfectly suited for the nomadic life of small hordes in relatively warm open country, flake tools—flint knives with finely retouched edges—came into use now for skinning and preparing game in far colder climates. As ever, a fresh set of material circumstances elicited a fresh technology. Rather than working a rough block of flint into a corelike implement, the Neanderthal could turn the residual flake—the waste product itself—into a ready-made tool of its own. This discovery, we're told, was nothing short of revolutionary.

We read on. We go on looking, as we've always looked, not so much for them as for ourselves, our own, obscure traces. Reading books, visiting museums, or simply stopping short before the vast, gold umbrella of some chestnut tree in mid-autumn, aren't we always, in a sense, looking for ourselves? A lonely species by nature, made even more so today by the loss of any commonly shared vision—any collectively accepted referent—we wander through galleries, archival tumuli, and archeological vestige, hoping to discover, at any given instant, the key, the tiny, metallic glint in the midst of our own shadows. Call it, if you will, the breath at the very heart of our own empty mirror.

We turn backward because there's nowhere else, finally, to look. Nowhere else to search for our own specific, instigating moment but through the caverns and peat bogs of a prehistory that continually escapes us. We go on, wading through the millennia, inspecting the scant evidence, hoping that a collar-

bone here, a chipped flint there, might give us some small inkling. We've been forewarned, however, that human evolution is rarely explicit. If indeed we can trace the immeasurably slow technological progress that so many unearthed artifacts attest to, we're still left with little or no idea of our predecessors as living entities. Even their skeletal remains are few and fragmentary throughout the early Paleolithic and most of the middle Paleolithic: throughout, that is, ninety-nine percent of human evolution. We have to wait until the very end of this seemingly interminable period—until the closure, that is, of the Mousterian, in about 32,000 B.C. —before we encounter the first full, fossilized skeletons. Are we, we might ask ourselves, turning necroscopic in our search for antecedents? More drawn, say, to the tibiae than the possible reconstitution of gesture, movement, reflection? No, quite the contrary. For we can only begin to reconstitute the veritable life of these predecessors when we're allowed to examine not the bones alone, but the manner in which they'd been prepared for ritual inbumation. The skeleton of a man, for instance, buried in a small rock shelter at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, his head facing east in a half-circle of stones, a bison's hoof for viaticum lying alongside, tells us more about our own hidden identity than any number of axes, blades, or scrapers. For here, at long last, we can begin to enter prehistoric thought itself. The bones, ironically, bring us closer now to the animate, the cognitive. In a distinct acceleration of human development that has both puzzled and fascinated prehistorians, we're given, quite suddenly, a wealth of evidence. We have, for example, the Moustier skeleton buried in a fetal position, its head resting for the past thirty-four thousand years in the fold of its right arm. Or we'll read of another skeleton: that of a nine year old discovered in southern Uzbekistan, his grave encircled with the horns of Siberian mountain goats. The skull of this child, significantly, shows the first unmistakable traits of a new level

in human evolution, of a new creature: Homo sapiens sapiens . We're at the dawn, now, of the late Paleolithic. More meaningfully, we're at the very point of encountering a hominid we can not only clearly identify but acknowledge. We're on the verge of self-recognition.

The late Paleolithic, we're told, began abruptly with extensive human migrations out of the Middle East (alleged birthplace of the Homo sapiens sapiens or Cro-Magnon), accompanied by critical advances in cultural development. Emerging as they did in the last pulsations of the final glaciation (about 36,000 years ago in France), these new, rapidly evolving societies carved the antlers of their favored game, the reindeer, into beautifully tooled pins, chisels, and hunting points with finely cleaved bases. Across the hard tundra, they hunted mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros, capturing their quarry in pitfalls or, where the ground was too frozen, erecting elaborate overhead fall traps to snare those ungainly mammals. But, far more than by any technological achievement, these Aurignacians—as they came to be called—distinguished themselves pictorially. For the first time societies began painting and carving, representing in images what had gone, until then, undepicted. The earliest cave paintings date from this period: their bold outlines—silhouettes, really—were executed by torch-light in red ochre and black oxide of manganese, or carved, scratched, incised into the rock partitions themselves. Portrayed in profile and in all their vernal innocence, horse and bison, ibex and antelope seem to gaze across thirty thousand years of elapsed time with a purity of line that astonishes us today.

Is it "art," then, in its very first manifestations, that we so readily associate with? Is it the power of representation that furnishes us—at long last—with that founding echo, that establishing fact? With the flush of self-recognition? Let's indeed look closer. What, exactly, has found expression in these earliest

graphic gestures? Is it the huge underbelly of the bison itself? Its gait, its carriage, the way its head seems buried in the massive heft of its shoulders?

No, we might readily respond at this point, it's none of these. The mammal, despite its figuration, hasn't been portrayed or replicated as much as conjured—graphically summoned—as a metaphysical entity. It's not, indeed, a representation we're admiring here, but an invocation: not a beast that's been depicted, but a wish . We might well imagine that the artists themselves, confronting the immense emptiness of the tundra in relation to their own dire circumstances, didn't paint what they saw but what they needed: the inherent power they might magically appropriate from those migratory game species that, otherwise, lay well beyond their reach.

In short, we're in the presence of an articulated absence, or, more exactly, of an interval that seems to span the space between the manifest and the imagined, to oscillate between the here and the there , the now and the ever-imminent then . Between, that is, desire and gratification, supplication and response. Does anything more fully characterize our own true nature? Our spatial dimension? We are creatures, indeed, of interval, of innate longing. Locked into an ongoing instant of continuous projection, we, as Homo projectivis (if such a neologism can be permitted), finally come, now, to the point where we can claim ourselves. After so many pages of text, covering so many ill-defined millennia of human development, we begin, at long last, to recognize ourselves in these first invocations. Page after page, illustration after illustration, we become, ironically enough, visible to ourselves in the same instant that we acknowledge those who depicted—for the first time, in still-hesitant outlines—the invisible. As we do, our mirror, quite suddenly, comes to fill.

The First Hunters and the Last

It's where the fields began to narrow on either side of a tight, rock-bound canyon that I'd find them. Arrowheads, javelin points—they'd lie scattered over the otherwise empty ground (especially after the winter rains) in a perfectly random manner. They couldn't, therefore, be associated with some prehistoric site, couldn't be considered, say, the emanations of some clearly delineated Neolithic settlement. No, given the absence of any other form of artifact (particularly ceramic) and the variable distance between one hunting implement and another, their presence—archeologically speaking—could only be qualified as "eccentric." But was it, in actual fact? Couldn't some relationship be established between the implements themselves and the gully just beyond? Couldn't something be learned from the fact that the frequency of my "finds" would increase in a clear, if sporadic, manner as I approached the canyon itself?

Here, I'd learned to read landscape as never before. Learned to interpret, as

a text of sorts, the muffled dialectic that exists, occasionally, between a specific place and its history: between a patch of earth, say, and whatever vestige it happens to exude of some past human culture. Here that vestige proved to be immensely eloquent. Judging by the artifacts themselves, I was dealing with a period of time that ran from the late Magdalenian, clear through the Neolithic to the very edge of the Bronze Age. In other words, I was dealing with the material evidence of hunting societies that spanned a period of no less than eight millennia, beginning with a moment twelve thousand years earlier.

Why here, though? I'd answer my question soon enough, for the response was all too evident. "Here," I came to realize, was a naturally endowed wedge for capturing game: a narrow, narrowing, funnel-shaped passage for running them down, cornering them within that tight limestone corridor. For a distance of at least a hundred meters it offered no shelter, no trees, no escape path whatsoever. Over the millennia, it had provided hunters, clearly enough, with an ideal ground for bringing their quarry to bay.

Twelve thousand years. The mind either balks at the immensity of such a figure or grows giddy contemplating the abstract expanse of so much elapsed time. There's nothing abstract, however, about the artifact itself: it might be a long, slender arrowhead in the form of a willow leaf lying in the palm of one's hand. Almost as long as the palm is wide, it's every bit as tactile, tangible as one's own pocket knife or fountain pen. Twelve thousand years suddenly seems to contract, to conflate into a single, glistening instrument. Like a lost word, a hieroglyph from some distant language, the artifact demands careful scrutiny, not just mere curiosity. It wants to be read.

Here, in brief, is a summary description of a few such artifacts from this location. I've chosen them for their value as specimens—as typological archetypes—and arranged them in chronological order. This order in no way

reflects the material circumstances in which I found them, spread out over several hectares of ground and covering a period in my own life of over fifteen years. It simply represents a sampling of the times I'd go out "silexing"—as I came to call it—after a day's work as a writer, and find myself, once again, scanning the empty expanses before me, scouring the ground for a second set of stray vocables, lost nominals.

A Shouldered, Laurel-Leaf Point (Pointe à Cran) Pressure-Flaked over Both Surfaces.

The "shouldering"—the tapering of the flange for the sake of its hafting—almost invariably indicates the Magdalenian. Most likely, too, this particular piece had been mounted on the tip of some long, slender javelin or lance rather than on the shaft of an arrow, for bow and arrow appear at a somewhat later date. We're still in the late Paleolithic, in the twilight of the last glaciation. Itinerant hunters, traveling in small, compact groups, supplementing their game foods with roots, wild honey, acorns, and larvae, still employ propulsors for sending their harpoons and assagais—heavy implements—flying though air. They still employ javelin points such as this one as they move—as if in symbiosis—in the wet tracks of the very last retreating reindeer.

A Transverse, Trapezoidal Arrowhead of Tiny, Microlithic Dimensions.

I might have missed this artifact altogether (and how many others, quite similar) if I hadn't seen its likeness illustrated in archeological manuals or displayed behind dusty glass showcases in local museums. These first true arrowheads are, in fact, remarkably inconspicuous. Not only small and relatively asym-

metrical, they were executed with a total disregard for appearance. In short, they don't "look like" arrowheads. Nonetheless, these tiny armatures (weighing two grams on the average), mounted on die-straight branches of hazel-wood and shot from the earliest sprung bows, could slice air at the rate of thirty meters a second. They'd tear—rather than pierce—the flesh of their prey; as such, they've come to be classified as trenchant or sectional weapons. Who, in fact, crafted these curious, trapezoidal shapes? We learn that they belonged to a people—an entire civilization—caught in a slow but inexorable process of transformation. Moving from a nomadic existence to the first, archaic forms of a sedentary culture, these people, who emerged in the Mesolithic (9000–6000 B.C. ), enjoyed the outset of a temperate climate not altogether different from today's. Simultaneously, they saw the arrival of a flora and fauna that would have remained to this day, had we not over the past thousand years disrupted our ecosystem to the extent that we have.

An Exceptionally Long, Almond-Shaped Arrowhead, Perfectly Bisymmetrical, Showing Traces of the Original Resin with Which It Was Ligated.

We've clearly entered, with this armature, the Neolithic, and so moved from the trenchant to the penetrant. As to the arrowhead's exceptional length, this can be related, readily enough, to the site itself. If, in the surrounding hills, I found arrowheads that never measured more than three or four centimeters, here I found points of the exact same facture that were nearly twice that length. The difference in dimension could only be attributed to their essential difference in function. If, in the hills, rabbit, hare, fox, and game birds were the traditional quarry, here in this natural limestone passage it was boar, wild oxen, and deer—driven down from the heights—that were tracked and cornered.

In both cases, the length of the point was perfectly commensurate with the weight—the bulk—of the game pursued.

Curiously enough, we've entered, with these beautiful armatures, a period in which the hunt no longer constituted a primary source of sustenance. Having come to settle in small agrarian communities, Neolithic people would depend increasingly on the harvest of their own crops and on domesticated cattle. According to osteological analyses, the bone remainders of wild animals would usually account, now, for less than ten percent of the total faunal deposits. One can only imagine, however, that game remained (as it does today), if not a necessity, a prized delicacy of the very first order.

An Arrowhead in Rippling, Honey-Brown, Zoned Silex, Barbed and Tanged to a Profile That's Often Compared to That of a Christmas Tree.

With implements such as these, we've reached the apogee of flint making. At this level of technical proficiency, we know that "the end is near," as one archeologist has put it.[1] Perfection, after all, can only edge toward its own exhaustion. Soon, very soon, the last moments of the Neolithic (labeled, rather misleadingly, as the Chalcolithic: 2500–2300 B.C. ) would produce the first trickle of a new, imported weaponry, pounded out of a hitherto unknown substance: bronze. Soon, the stone mallet and amorphous flint core would be supplanted by hammer and anvil; the open-air industry of knapping would give way to the smoke of so many blazing forges.

If I never found bronze arrowheads myself, it was due to both their extreme rarity and my own mischance. I'd simply never been lucky enough. On the other hand, I'd managed to collect a considerable amount of flaked prehistoric

hunting tools within a clearly delineated area. That area, I should add, didn't include the limestone passageway where the arrowhead would have been recuperated from the viscera of the felled animal; they were found, rather, on either side of that deadly passage. There, on either side, the point might have easily gone astray or been dragged into the surrounding undergrowth by a wounded mammal seeking shelter.

Words, I called them. In my own need to read landscape—cultural landscape—as text, I'd sought out whatever vocables, mute ideograms, I could find. But was my analogy justified? Wasn't an arrowhead, within that irreparably lost grammar, less like a word than an instance of punctuation, most particularly that of the hyphen? A hyphen that had miraculously survived each of the two terms it had once united: the hunter, that is, and the hunted? Wasn't I holding, in the palm of my hand, a handsomely pressure-flaked connective between two dissolved signifiers? Two totally divorced entities?

I was dealing, after all, with a period of time in which game was plentiful and human population slight. It was, in Marshall Sahlins's words, an age of abundance, that of an "original affluent society."[2] Never again would nature be so bountiful; never again would earth supply humankind with such a seemingly inexhaustible storehouse of meat, fish, wild fruits. The image of Eden—ecologically speaking—was far more than allegorical. The woods abounded with rabbit, roe, red deer, and boar, and in the foliage overhead shuttled snipe, woodcock, partridge, and dove. Yes, an Eden of sorts that existed—as Edens always do—in an immensely delicate, infinitely precarious balance between giver and given, provider and provided.

Today, it's difficult to believe that such a balance ever existed. As I'd take the path down to that prehistoric hunting ground, especially in winter when the fields had just been plowed and were already sprouting with fresh artifacts,

I would hear hunters—the very last hunters—crying out to their dogs. And I'd hear the dogs, too, their goat bells tinkling down out of the hills as they sniffed the wet grasses before them.

"Cerca, cerca ," I'd hear. "Keep looking," the hunters would cry out in Provençal as, from time to time, they came into sight, empty leather pouches slapping flatly against their flanks. "Cerca, chin ," they'd cry out as they followed the edges, now, of those freshly plowed fields, the blue barrels of their shotguns glinting metallic over one shoulder or lying prone in the crook of their forearms. It was, of course, a vacuous enactment, an empty ritual. For there is nothing left now to hunt. On the hunters' part, it has become, each autumn, nothing more than a ceremony that each performs, driven, no doubt, by some deep, vestigial instinct. Call it, if you like, a genetic tick arising out of some immemorial codification. For not only has the country been hunted out, the massive—abusive—use of insecticides has so totally upset the ecological balance that the remaining fauna has either fled or perished. This particular Eden has turned into a gameless wasteland.

Occasionally, of course, one might still bear of some passing gibier . Last winter, for instance, a boar was downed in these very same fields. Its innards, apparently, still contained traces of the rice it had last fed on, escaping—far below—the flooded estuary of the Rhone. But even then, as one hunter remarked, its hide was a good deal "pinker than black." Like most game today, it had been domestically bred. One might make the same observation in regard to the rare partridge, pheasant, or hare. Freshly released from the wire-webbed cage of some breeder, it no longer possesses the natural instincts—or savor—of its species. It makes for easy prey and yields little more than its own somewhat tasteless flesh. As for the wild rabbits, they're afflicted, more often than not, with myxomatosis, and they die from something far worse than

buckshot. The hunter today roams through woods and along the edge of fields that have long since relinquished all claim to natural habitat. Even the trees seem little more, now, than decorous props for an irrepressible, all-invasive technology.

I'm not suggesting that one need return to the Neolithic to rediscover some kind of natural equilibrium, for game in Provence remained relatively abundant until quite recently. I only wish to invoke a golden age in which wildlife was bountiful, and nature—a nature not only respected but venerated—provided for every basic human necessity. It was a time in which societies, living in relatively small numbers, enjoyed a perfect surfeit of sustenance; a time in which humankind—unhampered by humankind —knew plenitude.

"Cerca, cerca ." As I would scour the surface for artifacts, searching for traces of those first hunters, I would hear, in the distance, the petulant little cries of the very last. Hear the goat bells of their dogs as they rushed this way, then that, flaring out over the broken ground in search of some last surviving spoor. "Keep looking," the hunters would cry out. "Cerca lou lapin ," they'd call, entreating as they did, in that nearly extinct idiom of theirs, the very last escaping game. By eleven each morning, I knew, their hunting satchels would already be jammed with simples, wild chicory, salades de champs . And, at noon sharp, they would unload their shotguns—more out of outrage than cruelty—on anything that moved: crow, magpie, squirrel. Look—but for what? There was virtually nothing left, now, to look for.

If I'd come to read the aboriginal arrowhead not as a word but as a kind of hyphen drawn between two discrete quantities—between society and nature, the bestowed and the bestower—the connective itself implied agreement, reciprocity, trust. It implied a contract of sorts in which a lesser entity (ourselves) was granted permission to subsist upon the bounty of a greater entity (nature).

As a contract, alas, it has long since been broken. Subtle, immensely delicate, and perfectly determinant, it has left nothing today but scattered artifacts. Left nothing but those narrow, pressure-flaked flint weapons that once sliced air at thirty meters per second, conflating—as they did—the two indispensable terms of our very existence. Reciprocal signifiers—it's not altogether certain that we can survive without them.

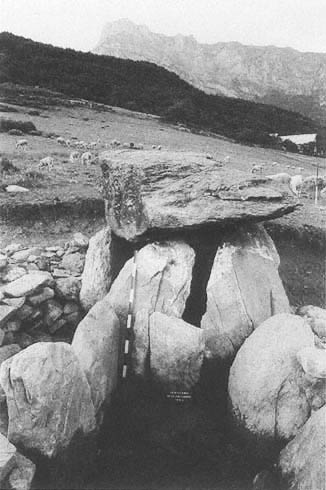

Neolithicizing Provence:

Cardial, a Culture That Came from the Sea

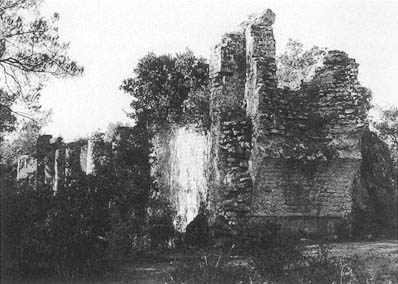

It came in a wave, in a steady, immensely slow, earth-lapping undulation. There was nothing to stop it. In what has often been called the single most significant moment in human evolution, the arrival of the Neolithic (in Provence as a bit everywhere) would mark the end of one level of development, based essentially on hunting in small, nomadic groups, and the outset of another, devoted to farming and stock breeding. In increasing numbers, societies would establish themselves in their first fixed communities. This immense evolutionary step was due, in part, to ceramics: to the invention of the earthenware container. In allowing populations to store, it allowed them to settle. In Provence, they would settle first in grottoes close to the sea. The earliest of these, L'Abri de la Font-des-Pigeons at Châteauneuf-les-Martigues, has offered archeologists a wealth of information.[1] From its lowest stratigrapbic layer, it has yielded—along with the oldest documentary evidence of ceramics in territorial France—the eponymic decor by which these ceramics might be identified.

A fragment of cardial ceramic ware.

Drawing by Gabriel Sobin.

Named Cardial ware after the seashell—the common, heart-shaped cockle (the Latin word is cardium )—with which it was imprinted, this earliest pottery celebrates its own origins. It came in a wave, as if emerged from the sea, from a sea already rife with oars, with sails, with the produce of emergent cultures bearing the first unmistakable marks of a Mediterranean homogeneity. Similar "impressed ware," dating from the same period, has been discovered in sites as apparently disparate as Corsica, Liguria, and Spain. In each case, the ceramics bear the characteristic signature of those initiating cultures. The imprint itself was obtained by pressing the serrated edge—the teeth—of the cockleshell against the yet unfired contours of the ceramic vessel. It left, as impression, a brief, vibratory squiggle suggesting liquid, liquidity, the shimmering of fluid, say, over the flanks of some stout, round-bottomed storage jar.

Curiously enough, this first manifestation of the Neolithic in Provence would remain water oriented throughout its two-thousand-year duration. In permeating the interior, it would follow the course of rivers, establishing itself

in small communities on either bank. Not once would it settle in the hinterlands, beyond. Reflexive by nature, the Cardial culture seemingly advanced with its face facing backward, never, at any point, renouncing its eminently marine—eminently Mediterranean—origin. Was this due to some basic, metabolic need on the part of those initiating societies? To a diet that required, say, a certain salt- or freshwater nutrient? This is altogether possible. In any case, these first Neolithic populations would continue to practice, along with agriculture and stock breeding, the essentially atavistic activities of fishing, trapping crustacea, gathering gastropods. Indeed, as they moved inland in that slow, wavelike migration of theirs, they'd leave—as vestige—not only their shell-impressed pottery, but so much scattered sea token, marine memento. In Avignon, for instance, along the banks of the Rhone, a worker operating a steam shovel in the 1960s discovered, quite by chance, an early Neolithic skeleton: an inhumed corpse in partial anatomical connection. Identified as that of a male in his mid-thirties, its skull was coiffed in a delicate hair net of perforated seashells. This net, a mesh really, beaded with Dentalia and Columbella, constituted an essential part of the defunct's funerary wardrobe, along with its seashell belt. Unmistakably Cardial, it offers eloquent testimony to a culture that—for all its revolutionary achievements in the fields of agriculture, animal husbandry, and ceramics—remained, nonetheless, profoundly reminiscent .

Even more remarkable, however, was the rate at which that wave—that slow undulation—would unfurl. For we have archeological evidence that the Cardial, in its infiltration of riparian Provence, took nearly a thousand years to travel from its initial site within close reach of the coastline, Châteauneufles-Martigues, to that of its ultimate station northward, Courthezon, in the Vaucluse.[2] The distance between these two points amounts to no more than eighty-five kilometers along a straight line. Even if we double that figure, however,

Cardial inhumation: note the traces of a funerary belt made of seashells

about the subject's waist.

Photo courtesy Gérard Sauzade.

to allow for the fact that this culture would have followed the sinuous contours of both the Rhone and its confluent, the Ouvèze, we're still brought to a startling observation. It took nearly a millennium for the Cardial to travel a distance that now can be driven in a bit more than an hour, and dialed—like anywhere else in the world—in a matter of seconds. We have grown so used to living in a violent contraction of space and time that, in comparing these two diametrically opposite cultures—ours and theirs—it's not the speed at which we're presently traveling that so astonishes us, but the apparent languor—immobility—in which they, the first Neolithics, seemed to indulge.

Two suppositions come immediately to mind. Whoever they were (and we know, in fact, painfully little), we may safely assume that they weren't motivated by gain, acquisition, conquest. They may, indeed, have lived very much like certain Californian tribes before the Spanish conquest: in relative autonomy, with mutually respected boundaries that kept each tribe, as if circumscribed, inside some naturally defined perimeter. Within that perimeter, however, lay an abundance of cultivatable soil and a seemingly inexhaustible store of natural resources. Living in relatively small numbers in the midst of so much bounty, these societies had no real need to expand. They self-sufficed. Their culture, consequently, didn't penetrate the interior as much as seep, trickle—traveling at exactly the speed at which recipient populations chose to absorb, to assimilate, their innovating techniques. Our first supposition, we discover, has led ineluctably to our next. Not only was Provence "neolithicized" without the least trace of conquest, cultural imposition, mainmise , but the whole process occurred—over that very period of one thousand years and within an area not exceeding a thousand square kilometers—at a cadence of assimilation entirely determined from within: by, that is, each of the collectivities involved. It should be noted that these recipient peoples were still living, for the most part, in the late Mesolithic: hunters and gatherers, they had continued to survive, at a subsistence level, in small, semi-nomadic communities. Almost entirely autarkic, they would undergo acculturation at a rate that varied according to the volition of each particular society. One after another, however, they came to cultivate their own fields, breed their own cattle, settling—for the first time—into fixed, agropastoral communities.

What happened, we might ask, to the Cardial culture, to those earliest Neolithic societies in Provence? They had marked the first—albeit hesitant—steps in what V. Gorden Childe called the Neolithic Revolution.[3] That revolution

would gradually absorb the Cardial in its three-thousand-year peregrination, totally transfiguring society at every conceivable level. Caught in its acceleration, the Cardial would fade, give way—inevitably—to far more aggressive forms of acculturation, yield to forces far less circumspect. The mid- and late Neolithic in Provence would create the material conditions for an immense increase in food production. This increase would lead the way, ineluctably, to a proportionate rise in human population. One would be the sine qua non for the other. In turn, this sudden demographic expansion would generate in a relatively short period of time a whole set of fresh conditions of its own. Most especially, it would spell an end to those unquestioned boundaries. Under the pressure of that spreading population came—naturally enough—incursion, encroachment. Came, by the end of the Neolithic, border disputes, property squabbles, intertribal conflicts. Came, for the first time (at least to our knowledge), the manufacture of flint weaponry for the express purpose of warfare. How, we might ask, can archeologists make this distinction, given that the arrowheads used in these intertribal conflicts in no way differ from those employed in hunting? The material evidence speaks for itself.[4] At Roaix in the Vaucluse, for example, the production of flint armature continued to rise at the same moment that the hunt (according to modern analyses of the faunal deposits) fell to an all-time low. There remained for most of those svelte, symmetrical projectiles but one possible quarry.

We might infer from the given evidence that these first verifiable instances of human conflict created in the consciousness of these tribespeople a heightened sense of the imminent, the impending, of the dangers that lay—permanently now—at the very heart of the temporal. That bit by bit societies had begun living against rather than within : living at the risk and peril of their own fellow creatures, as opposed to the inscrutable mercy of natural—call them

supernatural—forces. That bit by bit the temporal had begun substituting itself for the spatial: the perception of the immediate for that of the boundless. The rustling undergrowth for the radiant cloud.

None of these profound transformations in human consciousness would have been possible, however, without the technological achievements that immediately preceded them. Of all those achievements, the invention of ceramic ware would determine those transformations more, perhaps, than any other. Indeed, it would come to alter humanity's vision of the world altogether. Quite aside from the obvious advantages that ceramics afforded—to store food supplies against their very source, a capricious nature, that is—they gave societies the means to quantify what they'd always considered, until then, unquantifiable. They could count what they'd always considered, until then, uncountable. Humanity would begin laying down a reign of numbers over the fields of the given, the naturally bestowed. With so much well-stocked inventory, it could begin taking its distance from the unpredictable workings of invisible agencies. Bit by bit, it would come to separate itself from the inseparable, from that level of consciousness that admits to no severance between the animate and the inanimate, between the self and the inextricable fabric of so much surrounding phenomena. Increasingly, Neolithic societies would come to live under the privileged sign of number: a number by which they might not only measure but temporize, creating—quite unwittingly—the very conditions for their own ineluctable alienation. Bit by bit, they would come to take their distance from those earliest rocks, winds, stars, those immeasurable expanses of which they once felt themselves an integral part. Humankind would enter, now, a vision of existence based more and more on quantification and its immediate corollary: the temporal. At the far end of that vision—at the very extremity of its long corridor—the mirror of death would await those evolving populations.

It came in a wave: in a steady, immensely slow, earth-lapping undulation. It came as if despite itself, prescient—already—of the overwhelming effect it would have upon everything it touched. Wrapped against its own momentum, as if coiled in a futile attempt to check or—at least—minimize the extent of its own influence, it would carry, in its invisible chambers, the very memory of its lost origins. In the thousand years it would take to travel no more than a hundred and seventy sinuous kilometers, it would carry—imprinted on its ceramic vessels or perforated to adorn the bodies of both its living and its dead—the ubiquitous signature of the seashell. Mementos, indeed. Against the unraveling of what we'd come to call an irreversible evolutionary process, the cardium—the simple, pink-hearted cockle—would bear singular witness.

Archeological Rhetoric

for Jim Clifford

No more than a century ago, Provençal archeologists would go out on Sunday excursions, as they'd call them. Entering into "delectable valleys" (vallées délicieuses ), they'd follow the "fanciful curves" (sinuosités capricieuses ) of river beds in search of prehistoric artifacts: whatever those "archaic societies" (antiques populations ) might have left in way of vestige. If the language of those nineteenth-century erudites remained unfailingly lyrical, their vision, nonetheless, expressed a remarkable sensitivity to environment, to the specific qualities of place itself. Invariably, they'd associate their discoveries with the natural milieu in which they'd been found. Wind, shadow, the orientation of certain rock faces in regard to some specific stellar configuration would enter their reports. Nothing remained disrelated. Upon discovery, each artifact would immediately be assigned its place—rhetorically speaking—within the resonant fields of the associative.

As might be expected, however, that rhetoric was never more than ap-

An excursion to Bonnieux and Buoux: a nineteeth-century

rendering of artifacts. From Une excursion à Bonnieux et à

Buoux: Mémoires de l'Académie de Vaucluse, 1886.

proximative. Read today in light of modern archeological terminology, it strikes one as vague, impressionistic, even—in terms of documentation—downright irresponsible. We're still at the outset, we should remind ourselves, of a recently discovered "humanism," as opposed to the ever more specialized, ever more applied "science" archeology would soon become. In moving from one to the other, archeology would coin a terminology of its own. Indeed, in the intervening century, one may not only follow the development of archeology as discipline, but—simultaneously—as rhetoric. One, ineluctably, would reflect the other. In reading a set of field reports in any form of chronological order, for instance, one has the impression of gradually abandoning an entire environment for the sake of an ever narrower, ever more explicative field of inquiry. Of going, within a relatively brief span of time, from watercolor to x-ray.

Hector Nicolas—to take an example—in filing his report from Avignon on 8 November 1884, would describe the flint tools he'd found in those delectable valleys: there, where so many "clear ripples" (ondes limpides ) came to "ravish" (ravir ) the banks in the continuous "throe" (tressaillement ) of their passage. The tools themselves, alas, received far less evocative treatment. Some are described as having "no appreciable form" (sans formes définies ) whatsoever; a flint armature—an arrowhead? a javelin point?—is rapidly dismissed as some "roughly executed" (à peine ébauchée ) weapon of no discernible period.[1] We only need compare this passage with another, taken at random, from some present-day archeological study touching upon the same topological area. There, a particular artifact will be inventoried, for example, as follows: such and such a "mesial fragment of a blade(let) with proximal fracture due unquestionably to thermal action" will exhibit traces of "silica gloss on its scalariform edge-dressing interrupted, occasionally, by irregular flaking . . . ," etc.,

etc. The instrument itself, we learn, was fashioned out of a "quasi-translucent blonde silex" and discovered at such-and-such a square centimeter on "stratigraphic level 38" of such-and-such a site.[2] In comparing these two documents, one is struck, of course, by the qualitative difference in their descriptions. One soon comes to realize that this young discipline, in growing ever more precise, would create for itself an ever expanding taxonomy. As its field of inquiry narrowed, its terminology could do nothing but proliferate.

The focus of attention would come to fix itself almost exclusively on the artifact itself. Today, a particular flint tool, for instance, is first examined in relation to its raw material: the flint nodule or the matrix that once encased it. After preliminary study to determine the morphology of a "reconstituted lithic assemblage," an unworked nodule of local extraction will undergo "granulometric analyses" to gauge the frequency of "fracture propagation" under assumed working conditions. These analyses will be followed by others to measure the "elastic and isotropic qualities" of the mineral involved and its aptitude, finally, for knapping. We've come a long way from those Sunday excursions and the poetic résumés of that early Provençal archeologist, plucking artifacts like pastries from the entry of some "monstrous cave" (caverne monstrueuse ). In no time whatsoever, we have gone from a single individual's immediate impressions to the thoroughly anonymous data of irrefutable, material fact.

After all those intense, preliminary analyses, touching on the inherent qualities and susceptibilities of its mineral composition, the artifact will then undergo a series of examinations to determine the technical aspects of its fabrication. Typometric, typological, and functional, the criteria for these examinations have grown increasingly exacting. For its edge-dressing alone, a given blade will be scrutinized to determine the precise angle at which its pressure-flaked dressing was executed. Even the scale of the flakes themselves ("long,"

"short," "invasive," "self-inclusive"), their morphological characteristics ("scutate," "scalariform"), the very cadence—rhythm—of their distribution, will enter an ever-expanding field of determinants. With each new determinant, we'll have—of course—a fresh description. The terminology only goes on growing.

Laboratory examination with the naked eye isn't enough, though; the artifact will inevitably fall subject to intense microscopic readings as well. At a low level of magnification, it will undergo "edge-damage analysis" to determine by scratch marks alone (its "stigmata") the direction in which it was originally employed, the extent of wear that it underwent, and, of course, the exact function it once fulfilled. These tests will invariably be followed by others under increasingly high levels of magnification. In "microwear analyses," for instance, through the use of scanning electron microscopes, bits of residue—vegetal fiber, phytoliths—will occasionally be detected along the edge, say, of some particular instrument. This detrital deposit gives research archeologists invaluable information in regard to the materials that this instrument once serviced.

Have we grown any closer, though, to those scant deposits? To so much scarcely perceptible matter? Indeed, in reading archeological studies, one has the distinct impression today that our means of detection overwhelm the vestigial materials that they've come to detect. We know more and more, it seems, about less and less. Victims, perhaps, of our very methodology, we've zeroed in on an ever narrowing field of inquiry. We've come to question, in ever more incisive terms, a body of material increasingly devoid of context.

Concurrent, now, with all the laboratory analyses come graphs, charts, "typometric diagrams" that trace—in sprays of minuscule dots—the displacements of a particular lithic manifestation. Called clouds, these sprays carry in

their amorphous drift a whole microcosm of prehistoric data. Where, though, in all this processed information, are those lost societies? Where are those vanished cultures in the minutia of so many hyper-refined pictographs? Granted, archeology as "the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of physical remains" (as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary ) shouldn't be confused with metaphysics, with our own private need to affix an existential value onto each material insight. And yet, here we are, shuffling through the pages of that human history and prehistory, wondering, indeed, who those forgotten people really were. Well beyond the internal wars that archeologists wage over the increasingly finite questions of chronology and classification, we go on asking, too. As our own most distant reflections, we're curious to "unearth" the air that they breathed, the very sounds with which their rock shelters resounded, the lightning bolts in which they might have recognized the jagged signatures of an otherwise invisible spirit world. They escape us, of course. Escape us entirely. Our speculations, finally, are nothing more than the by-products of flair, instinct, intuition: our own, sensorial "reading" of so much extinct human landscape.

Has modern archeology, though, in its microsurgical approach to prehistory, come any closer, we might ask? As a science devoted to the study of human culture, has it taught us any more, in fact, than did those first, leisurely scholars who would amble out on Sundays in search of artifacts while remaining, all the while, unfailingly attentive to the contextual elements of place itself: the attributes—both palpable and impalpable—of a given historic environment? Nature, as Heraclitus wrote, loves to hide. So, too, does the veritable sense of so much apparently interpreted matter. Indeed, it might even be said that every fresh concentration of knowledge generates, ipso facto, a fresh dispersion. Nature—one might extrapolate—loves to flee.

Nicolas put it another way. In the opulent rhetoric of his time, he reported: "There where the mountain thrusts itself forward in immense, overhanging ledges, the shelters beneath defy all description. For it is there," he went on, "that the projecting, geological strata, hovering over their prodigious volumes would seem to protect those archaic societies from our very investigations."

"To protect those archaic societies from our very investigations." We go on investigating, though, don't we? Go on examining so much scant evidence for its least, elusive trace. Go on entering, in the ever narrowing field of a continuously expanding terminology, our own impacted data. The data, however, do not seem to bring us any closer.

Moon Goddess:

Speculations on a Pictograph

In every archaic culture, a grammar of images, of pictographs, precedes that of letters: the sign, or sema, is first of all pictorial. Even if these pictographs evolve with time into phonetic units—find themselves transformed, that is, into so many verbal signifiers—at first it is the pictures themselves that speak . Carved into wood, rock, deer's antler, it's the sign, the linguistic antecedent, that signifies . Having neither the aesthetic pretension of sculpture nor, as yet, the verbal attributes of the written character, it belongs to an intermediate idiom of its own.

Five kilometers northeast of Arles and only several hundred meters beyond the Abbaye de Montmajour, a series of such pictographs can be found scattered over open ground. Carved in limestone on flat, recumbent slabs or, in one case, upon the flank of a menhir, they each describe an inverted U . Down the center of that inverted U runs a prolonged dash. Taken together, the vaulted U and the vertical dash it encloses form the two movements—reciprocal

Carved pictographs from Les Collines de

Cordes. Drawing by J. Granier;

courtesy Palais de Roure, Avignon.

gestures—of a single, singular pictograph. This pictograph may or may not be accompanied by outlying dashes, crosses, cupules: signs that have traditionally been interpreted as stellar. As to the meaning of the pictograph itself, we have only what the archeologists would call working hypotheses. We may safely assume, however, that the sign, unmistakably female, represents the vulva and, as such, signifies birth, fecundity, perpetuation. It's not by chance that this immediate area, Les Collines de Cordes, is rich in hypogea: underground burial chambers carved in long corridors out of the surrounding rock.

Clearly the pictographs relate directly to the burial chambers themselves. For everywhere throughout the megalithic culture of this period, symbols of re-birth and regeneration accompanied the dead. Nowhere, we may safely say, was life represented in all its procreant magnitude more fully than in these late Neolithic burial sites.

Far earlier, though, in the midst of the Aurignacian (in about 30,000 B.C. ), the inverted U -shaped pictograph had already made its appearance. Labeled "vulvaform" by André Leroi-Gourhan, it was often represented, painted or engraved, deep within the recesses of any number of late Paleolithic underground sanctuaries such as those at Abri Cellier and Abri Castanet. In the Cabinet des Félins at Lascaux, the inverted U of the vulva is repeated three times in a concentric, vibratory pattern, thus bracketing the vertical stroke mark of the vagina within. The form, of course, is ineluctable. In an iconographic rendering of the female anatomy, the pubic section—be it oval, triangular, quadrilateral, or claviform—could hardly be treated otherwise. Evidence indicates that Magdalenians would travel great distances to collect this very sign in the form of a seashell, a delicate bivalve known, appropriately enough, as a cypris . Named after Aphrodite, the Cyprian, its form bears a striking resemblance to that of a vulva. The sign itself must have constituted a privileged element in an alphabet of signs, be it carved upon the face of a wall or simply collected as a naturally endowed ideogram.

Here, though, in Les Collines de Cordes, we're no longer in the Paleolithic, but in the late Neolithic (about 3000 B.C. ). Although graphically identical, the sign itself has undergone a fundamental symbolic change. Throughout both the Paleolithic and Neolithic, it signified, of course, fecundity. If, however, in the former period that fecundity was exclusively perceived in terms of the living (and most especially in regard to the propagation of the species), in the

latter period it came to be associated with the regeneration of the dead. In the afterlife of the corpse, laid in fetal contraction within the cella of some chamber tomb, it suggested—we may safely speculate—rebirth and resuscitation, but in a world apart. Symbolically charged, the pictograph not only invoked that second world but indicated the way—the very passage—by which the dead might accede. Manifestly enough, the way was matricular.

It would be tempting to compare this relatively discreet sign with that, far more explicit, of the famous "Cuttlefish of Lufang" pictograph, carved upon the wall of a chamber tomb at Crach in the Morbihan, or the painted frescoes of that same sea creature as they appear at the palace of Knossos in Crete. The similarities are remarkable. Scarcely disguised by so many surrounding appendages, couldn't this cephalopod be the very signature of the vulva itself? What's more, can't we speculate that we're dealing, in each instance, with a moment in the late Neolithic in which lunar (and thus aquatic) divinities reigned over the consciousness of humankind? In which the diaphanous figure of the moon goddess herself still flooded the fields of the human psyche? Indeed, with these scattered pictographs in Les Collines de Cordes, we might well be witnesses to the very last moments of those "lunar-telluric-agrarian hierophanies," as Mircea Eliade describes them.[1] Soon, we know, these somewhat subliminal, if all-determinate, divinities will be replaced everywhere by male counterparts. Undergoing a steady process of "virilization," the mythologies of late Neolithic and Chalcolithic societies will gradually solarize : gradually abandon the discreet, somewhat esoteric signatures of the lunar divinities in favor of the ever more figurative, "activated" representations of the nascent sun gods. We're on the verge, now, of history. It's a time in which humankind would come to take increasing technological control over its natural environment. Along with farming and stock breeding, the advent of metallurgy (bronze and,

soon after, iron) would permit societies to live with a growing sense of independence in regard to their immediate environment. In greater and greater numbers, agropastoral communities would spring up, developing, as they did, an increasingly hierarchical, increasingly male-dominated socio-religious mentality. Chieftains, now, would be consecrated upon death and treated as divinities, gods invested with the fecundating powers of the sun, as opposed to the germinal effusion of those far earlier "lunar-telluric-agrarian" goddesses whom they'd come to replace.

One profound transformation would beget another. Along with new societal structures would come an increasing need to abstract: to eliminate the last mimetic traces of nature with an entirely fresh set of cognitive signals. Already, out of the Fertile Crescent in the Near East, the first alphabets would have made their appearance. Soon, even in Provence, the carved sign would be replaced by the written sound. A new order would come into play. The pictograph—resemblant, reflexive, metonymic—would vanish forever.

It's all the more moving, today, to find traces of that lost language and, perhaps, one of its quintessential signs: the vulval imprint of the moon goddess herself. Here, though, in Les Collines de Cordes, that scattered sign lies exposed to vandalism, growing atmospheric pollution, and the increasingly frequent brushfires that have come to ravish the surrounding undergrowth. Reduced today to a terrain vague , the area itself has been enclosed in wire fencing by its irate proprietors, but little can be done, ultimately, to protect these rare pictographs from the incursion of squatters, delinquents, or, far worse, the well-informed treasure hunters who come to pillage the hypogea.

We're left, as ever, with what remains. Isn't history, in fact, never more than that which, miraculously enough, survives history ? The salvaged document? The patiently deciphered tablet? The accidentally uncovered tomb? Yes, we're

left, at least here, with the scattered pictographs of a culture that hadn't yet codified its signs into script, hadn't yet "civilized" its divinities by the mediation of abstract signifiers. It still basked in mimetic effigy; with these vulval imprints it still felt itself rung—we may assume—in the matricular outlines of an all-embracing lunar cosmogony. Far more advanced cultures would come, soon enough, to replace it. But it's not altogether certain that this culture and the profound deposits it left within the human psyche could, in fact, be replaced. For at an operative level, there'd be nothing, absolutely nothing, with which to replace it. It constitutes foundation itself.

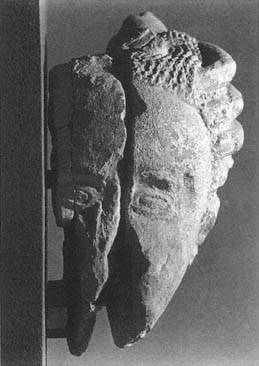

The Skull with the Seashell Ear

We're duly forewarned. Culture, in the eyes of archeologists, refers exclusively to material culture: to the little we can glean and, upon gleaning, interpret from those vast, subterranean warehouses of mute artifact. Long since removed from any sociocultural context whatsoever, the artifact, be it bone, flint, or the charred tube of some steatite bead, reaches us bereft of instigating factors—language, gesture, ritual. For all intents and purposes, the artifact reaches us blank. It can, of course, be dated. Thanks to thermoluminescent and radiocarbon analyses, a time frame can usually be established. Furthermore, the artifact itself can be compared, typologically speaking, to other artifacts. One bit of material evidence can be brought to substantiate, to testify for another. The artifact remains, nonetheless, an essentially mute object: a thing in a taxonomy of things, methodically numbered, classified, relegated. It belongs, ultimately, to nothing more than inventory itself.

Occasionally, though, an object seems to break free from all such relega-

tion. From the tight circle of so many given, scientific determinants, it will assert itself at a depth, a dimension, entirely its own. Such is the case with a skull discovered in 1955 by archeologists excavating a megalithic chamber tomb at Roque d'Aille in the Var. The skull, unearthed from the lowest and consequently earliest stratigraphic layer, had quite clearly undergone cremation. Exposed to the latent heat of a pyre of less than 500 degrees centigrade, the skull, according to modern analyses, hadn't suffered the cellular decomposition that's invariably brought on by higher temperatures. Calcined, it had done little more than blacken.