Preferred Citation: Erlich, Gloria C. The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft500006kn/

| The Sexual Education of Edith WhartonGloria C. ErlichUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1992 The Regents of the University of California |

To Phil

In all ways, the foundation

Preferred Citation: Erlich, Gloria C. The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft500006kn/

To Phil

In all ways, the foundation

Preface

At first [Freud] took sexuality to be unproblematic: what was surprising was the extent to which sexuality spread throughout psychological life.

Jonathan Lear, Love and Its Place in Nature

Lest anyone be deceived, let me state right off that, with the possible exception of the appended fragment that Wharton intended to suppress, this is not an X-rated book. The "sexual education" of my title refers both to mastery of "the facts of life," which was an uncommonly problematic business for Edith Wharton, and to something much larger and more pervasive—akin to Jonathan Lear's idea that "human sexuality is an incarnation of love, a force for unification present wherever there is life."[1] For Edith Wharton sexual education was a lifelong process of coming to terms with the role of love and sensuality in human experience.

This book traces Edith Wharton's erotic development and her use of writing to explore new possibilities for that development. The process starts with flaws in the mother-daughter relationship that derailed her emotional development and caused a massive sexual repression. From this unfortunate beginning, Edith Wharton moved unprepared into a disastrous and celibate marriage, so that her awakening to full sexuality was delayed until her mid-forties.

Childhood deficits left her with special developmental tasks that she performed in her own unusual way. Her inability to acknowledge the most basic facts of human sexuality must have caused great confusion in understanding the world about her—both personal and social relationships—saddling her with many misconceptions that she had to correct. In addition,

she had to revise her flawed maternal imagery in order to forge a functional gender identity along with a professional identity. Because sexuality pervades human experience, my story follows several interacting and evolving identity systems—the filial, the sexual, and the creative, each influencing the others.

The book proceeds from the hypothesis that the common social custom by which children receive their primary nurturance from mother surrogates, such as nannies or nursemaids, alters children's maternal imagery and has, therefore, significant influence on their emotional lives. Considering the amount of research currently accorded to mother-infant interactions during the pre-oedipal period, it is surprising how little attention has been given to the consequences of splitting the child's first feelings of attachment among multiple nurturing figures.

The consequences are not uniform or predictable because there are many variables, including social norms, the presence or absence of class difference between the mother and the surrogate (sometimes a family member, often an unmarried aunt), and the child's level of reactivity to this aspect of its environment. In the introduction that follows I adduce testimony about the significance of multiple mothering from a variety of cultures—British, Italian, French, Austrian, and American—admittedly all western and, except for Leonardo da Vinci's Italy, relatively recent, but diverse enough to indicate that whether or not the phenomenon is universal, it is worthy of attention.

The project evolved from my previous book, Family Themes and Hawthorne's Fiction .[2] In that book as in this one, I register the impact of a psychic design derived from early family experience on the particular channel and course of an author's creativity. In Family Themes I examined the effects of doubled paternal figures on Nathaniel Hawthorne's imagination. His psyche and imagination were affected by the split between his biological father, whom he scarcely knew, and a father-surrogate whom he found oppressive.

In both books I treat doubled parental imagery as a salient

feature in shaping the authors' imaginations without suggesting that split parenting is the sole key to their lives and works. Cultural attitudes toward gender and the profession of authorship play into the entire process. With both Wharton and Hawthorne, the power of social attitudes was reinforced by peculiarities of the family constellation.

Edith Wharton experienced a particularly intense form of the kinds of neurasthenia that Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar attribute to nineteenth-century women writers. She suffered for extended periods from eating disorders, hysteria, migraines, claustrophobia, and asthma.[3] Despite her professional success, she never stopped experiencing the "anxiety of authorship" that Gilbert and Gubar find peculiarly intense in women writers. Her individual psychology played into and intensified prevailing social constructions of femininity, creating pressures that she tried to solve by means of her fictive imagination.

Neither biography nor pure literary criticism, this book looks at the continuities between Wharton's life and art. Life and art illuminate each other; neither is privileged over the other, neither subordinate. If The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton contributes something to the psychology of love, it does so by reading the letters, memoirs, fiction, and poetry of this very articulate woman as a composite record of her inner and outer life. Indeed, the book studies this writer's use of fiction to rework her maternal imagery, to imagine scripts for future development, and to integrate alienated aspects of her self. This reciprocal method allows us to see not only the autobiographical elements in Edith Wharton's fiction, but the psychic work fiction performed in the construction of the author's selfhood at various stages of the life cycle. To accomplish this, I try to link into one interpretive system several apparently separate domains: family constellation, cognitive style, sexual development, and literary themes.[4]

The first chapter presents Edith Wharton's early family constellation and an overview of its implications for her life and work. It shows that the emotional split between mother and

nanny initiated a fairly intransigent psychic split that would later be reflected in Wharton's delayed sexual awakening and celibate marriage. I try to envision how it felt to be this ardent and imaginative girl living within a family and social system that denied both her sexual impulses and her creative urges. These drives merged in her father's library, a "secret garden" where sexual inquiry and ecstatic experiences flowed together. From Wharton's autobiographical statements, her erotic poetry, and the incestuous "Beatrice Palmato" fragment, I identify what appears to be the nucleus of her fantasy life—the displacement of her sexuality onto words and books.

Chapter 2, "On the Threshold," analyzes Wharton's first major novel, The House of Mirth, as an extrapolation of the author's family themes and sexual repression. The marriage-seeking heroine is unable to cross the threshold into sexual maturity. Convinced that the novel is driven by the author's own psychological urgencies, I challenge the social-determinist view that it is society that dooms Lily Bart to an untimely death.[5]

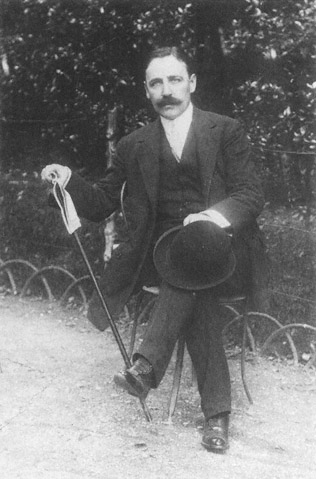

At the center of the book stands Chapter 3, "The Passion Experience," which deals with the dynamics of Edith Wharton's belated sexual awakening in a midlife love affair with the bisexual journalist Morton Fullerton, an unlikely pairing that has long puzzled her biographers. This chapter shows how her own imagination had prepared Wharton for her choice of such an amoral libertine and how Fullerton's incestuous inclinations meshed with Wharton's own. She had anticipated such a relationship in "The Touchstone" and would later elaborate on it in The Reef .

Chapter 4, "Parental Inscriptions," opens with Wharton's relationships with men after the Fullerton affair and her subsequent divorce, showing how her circle of male friends functioned almost as a composite husband. The works of this major period reflect new reworkings of her familiar motifs—sexual inhibition, incest, and complex variations on split parenthood.

The concluding chapter, "Final Adjustments," shows Edith Wharton using fiction to devise scripts to work through the

loneliness and fears of old age. In the Vance Weston novels, Hudson River Bracketed and The Gods Arrive, Wharton moves from the biological mother to a mythicized and benevolent maternal principle. With this change in maternal imagery she was able to bring her femininity into alignment with her creativity by reinventing herself as a mother whose posterity would consist of books. Over this kunstlerroman of a novelist hovers the generative figure of Emily Lorburn, a woman of letters who presides over her own library and inspires the next generation of writers. In Wharton's posthumous final novel, The Buccaneers, her lost nanny returns in the form of a governess, a benign and healing figure who leads a young woman into sexual maturity.

In view of the interlocking of Wharton's affective and professional identities, her greatest creative act may well have been the forging through her own intellect and imagination what life had denied her—an inner mother that would suffice.

Introduction—

On Double Mothering

How was it that hundreds of thousands of mothers, apparently normal, could simply abandon all loving and disciplining and company of their little children, sometimes almost from birth, to the absolute care of other women, total strangers, nearly always uneducated?

Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, The Rise and Fall of the British Nanny

Interrogation of the commonplace has in recent decades yielded radical new perspectives for social historians. They delight in discovering the consequences of practices and beliefs so widely accepted as to be almost invisible at the time—such as assumptions about gender roles, family structure, and hygiene, or, more pertinent to the present purpose, the effects of servants on the life of a family. Biographers and psychoanalysts have been slower to recognize that commonplace experiences such as the presence of a servant or a nursemaid in the household may indeed influence a child's development and constitute a significant element of a life history.

In a remarkable piece of social history, The Rise and Fall of the British Nanny, Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy examined the nanny phenomenon during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Britain, revealing how multiple mothering affected the personality, career, and psychosexual lives of many people, including public figures such as Winston Churchill. The book presents a social history of British upper-class mores, which fostered the development of a nanny culture. It

also offers a historical and psychological perspective on multiple mothering—ranging from foster care and wet-nursing to communal child-rearing on kibbutzim. Gathorne-Hardy is sensitive to the ways in which the introduction of an alternative nurturing figure affects the dynamics of the family and the future erotic life of the child. He observes that upper-class nanny-reared men tend to feel less sexual potency with their wives than with working-class women, perhaps because the latter remind them of their most intimate early caretakers, their nannies.

Gathorne-Hardy expresses astonishment that Anthony Storr, a psychoanalytic biographer of Winston Churchill, tried to account for Churchill's personality by reference to parental neglect without recognizing the formative role played by his beloved nanny. When queried about this lapse, Storr acknowledged that Nanny Everest had indeed saved young Winston's life but argued that "a Nanny's love never made up for a hostile or neglectful mother because a child always knew the mother was the authority."[1] Storr's claim is true enough, but imperfect compensation for maternal deficiencies does not eliminate the nanny from the psychic picture; it complicates the picture.

A large part of the upper-class English child's socialization was left to its nanny, who tended to be a strict disciplinarian. The classic British nanny, according to Gathorne-Hardy, was probably more repressive than the child's own mother would have been, possibly because of a sexual puritanism among women of the respectable working class. Such women were trained by the nanny culture to perpetuate the values of the ruling class. Nannies and nursemaids were at least as snobbish as their employers and probably more rigid about the social distinctions that discriminated against them. But warm and loving nannies, such as Winston Churchill's Nanny Everest, did exist and did, to some degree, compensate for maternal deficiencies.

The nanny of American novelist Edith Wharton was of this loving breed, and she earned the undying affection of her

charge. A major contention here is that Nanny Doyley's presence shifted the forces within young Edith's family constellation and thereby modified her inner life. Biographers are quick to fault Wharton's mother but insufficiently appreciative of the way the introduction of another woman into the child's affections at a particularly sensitive stage could modify family relationships.

For a girl of Edith Wharton's time and social class, rearing by nannies and governesses was customary. In old New York society of the Gilded Age, socially prominent women like her mother did not attend to the details of raising children, and they were not negligent for hiring substitutes. They perceived their principal responsibility as maintaining the social position of the family by entertaining, making social calls, appearing at cultural and charitable events, and being generally ornamental. The daily care and training of children they deemed fit occupation for working-class women with genteel manners. Placing greater emphasis on the social aspects of the wifely role than on the nurturing function of motherhood, they did not give much thought to the psychological impact of class differences between themselves and their children's caretakers.

The meaning of such a widespread and accepted practice differs according to the temperaments and circumstances of children brought up under it. The differences lie in the specifics of the individual life—the details of family relationships, gender, class, culture, and most important, the degree and direction of the child's responsiveness. I suggest here not that surrogate nurturance is a negative practice with predictable or measurable consequences, but merely that it is likely to make some difference in the child's inner world. Rather than try to judge whether the difference is detrimental or beneficial, I am inquiring in this case about a particular child's sensitivity to such a practice and about the nature of her adaptive mechanisms. In this book I study the effects of surrogate mothering on an extremely intelligent and reactive child

Whose writings as an adult indicate that this experience was for her a formative one.

My views on the subject of multiple mothering challenge those who believe that our tradition of mothers rearing their own infants is only a social construct, either an artifact of human history or part of a patriarchal plot to subjugate women. Following the lead of early twentieth-century thinkers such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman,[2] some feminists, including Dorothy Dinnerstein and Nancy Chodorow, among others, see nothing essential in the mother-child bond and believe that mothering can be done equally well by a father, an au pair, or the staff of a day-care center. According to this view, "'mother' is not a noun, it's a verb." Nancy Chodorow argues:

The cross-cultural evidence ties women to primary parenting because of their lactation and pregnancy functions, and not because of instinctual nurturance beyond these functions. This evidence also suggests that there can be a variety of other participants in child care . . . The prehistoric reasons of species or group survival which tied women to children have not held for centuries and certainly no longer hold today . . . There is substantial evidence that nonbiological mothers, children, and men can parent just as adequately as biological mothers and can feel just as nurturant.[3]

This may well be true under certain circumstances, especially if the surrogate care is good and the mother would prefer to be doing something else. Today even mothers who long to tend their own infants are being driven into the work force in unprecedented numbers by economic pressures, earnestly hoping that their child-care arrangements will entail no loss to their babies.

In general, however, recent infant research stresses the exquisitely fine attunement between an infant and its biological mother. This begins during the long months of gestation that heighten the mother's awareness of the coming infant. Her

interest is focused on this one as-yet unknown being, so that when it is finally revealed to her, she is attentive to its slightest signals. The focused attention generated during gestation and the early period just after birth is a major part of her message of care. According to research summarized by Joseph Lichtenberg, "Mothering behavior is primed for the immediate postpartum period and ... early separation can adversely affect the developing maternal bond." He cites experiments showing a direct correlation between the amount of immediate mother-infant contact and the strength of the mother's bond to the child.[4]

Correspondingly, from its earliest days the child knows its mother from all other women—knows the contours of her face, the smell of her milk and her body, the sound of her voice—and prefers this woman to all others.[5] Ideally, each recognizes the other and validates the role of the other—the mother as a good mother, the child as an infant pleasing to this mother and safe in her care.

As D. W. Winnicott made us aware, the details of child care—from the manner of holding, feeding, and cleansing to attunement to the child's slightest signals—function as a language to which the infant responds in minutely sensitive ways. Through this mother-infant dialogue the child becomes socialized into a specific kind of human being. In this mutual attunement is the child's first experience of a shared world, an intersubjectivity that evolves into a need for sharing experience with others. On this first wordless dialogue rests the capacity for intimacy and a preference for certain kinds of relationships.[6]

The inherited range of potential selves becomes, through this interaction, a specific self with its own style of being in the world, its own style of loving, doing, and perceiving. Other primary caretakers would shape a different self because their language of behaviors and style of attunement would evoke different elements from the child's innate repertoire. Infants are adaptable and can shape a coherent self from a multitude of nossible caretakers. but the current consensus

indicates that lack of consistency and reliability in the first attachment can hinder development of a coherent self.

Even though a good surrogate is probably better for a child than a deficient mother, substitution of the first attachment figure with another (however capable and loving) initiates an obscure sense of deprivation, loss, and anger. A delicate link is violated, even though other, stronger ones may be forged. To regard as abandonment the commonplace practice of delegating a child's care to a professional caretaker may seem extreme, but the infant may experience it as abandonment and come to resent the mother of whose smell, voice, and hovering face it feels deprived. In cases described by psychoanalyst Harry Hardin, the child becomes estranged from its mother and perceives her as having turned away her face, or having turned her back to it.[7] Although quite capable of forming bonds with caretakers other than its biological mother, the child will retain in its soul this early bifurcation. A special and very refractory variety of psychic splitting will have occurred.

In discussing the strong attachment to mothers even of children who spend five days a week in day-care centers, from as early an age as three and a half months, psychoanalyst Louise J. Kaplan cites a study by Jerome Kagan of the maternal attachments of children raised communally on a kibbutz: "The number of hours a child is cared for by an adult is not the critical dimension that produces a strong attachment. There is something special about the mother-infant relationship. The parent appears to be more salient than substitute caretakers to the child. It is not clear why this is so."[8] The salience of birth mothers over "psychological mothers" even when there is no significant class difference testifies to the power of the biological bond but fails to address the consequences of severing the two.

If the caretaker is the one whose hands provide the closest experience of human contact, the one who really trains and socializes the child, the more salient mother, for whom the child's heart yearns, comes to seem rejecting and remote. Anger then taints this first love, and the child will have difficulty

gaining a realistic image of its resented mother. The salient figure is not obliterated by the nanny; she holds her important place, but with her back turned, so to speak. A passage from Wharton's memoir quoted in the next chapter depicts her nanny and furry dog in the foreground of her family memories, her mother in the background with "all the dim, impersonal attributes of a Mother, without, as yet anything much more definite" (Backward Glance, 26).

Wharton regarded her nanny as a benevolent goddess who wrapped her in a cocoon of safety, but even good care proffered by a nursemaid is a commodity purchased by parents who renounce this role for themselves. Any nanny can be dismissed, and even if retained, she will depart eventually to care for other, younger children. When she leaves, the child feels abandoned, or, we might say, doubly abandoned, because the second loss amplifies the first. The child loses the illusion of what it never really possessed, an inviolable bond with its first beloved caretaker. The departure of a nanny seems a far more radical infidelity than the diversion of a mother's attention by a new baby; the nanny's total and seemingly willful disappearance must feel like a radical betrayal of love and trust.

Harry Hardin has studied the sequelae of early primary surrogate mothering in general and in the life of Sigmund Freud in particular. From his review of the scanty literature on the subject he concludes that those who experience nanny rearing tend to feel estranged from their birth mothers, that "surrogate mothering is synonymous with loss"[9] and usually results in problems with intimacy:

Initially, introduction of a surrogate into the family may cause a severe disruption of the infant's relationship with his own mother; this occurrence may initiate the patient's life-long avoidance of further intimacy. Then, with rare exceptions, the infant inevitably, and often suddenly, loses the [surrogate] caretaker . . . In my view, no infant can be psychologically unscathed by such trauma which so often occurs during its vulnerable separation-individuation phase of development.[10]

Furthermore, "as a result of her alienation, the mother is rendered incapable of adapting to her infant's changing requirements when the surrogate leaves."[11] Hardin adduces a case in which an infant perceived its return to the care of its natural mother as an adoption. Both mother and child, then, are altered by the introduction of an alternate primary care-taker.

The infant's attachment to a nanny is likely to cause the mother to become jealous. Loss of importance to her child acts as a negative reinforcement, reducing her pleasure in being a mother and creating friction within the triad. Without positive reinforcement, she will be less effective in her role. What is basically hers alone, the thrill of being the most important person in the world to this tiny, totally dependent human being, goes to a stranger. And eventually the child will feel guilt at having transferred this irreplaceable gift outside the family, where it will be lost forever, severed from its natural affective chain.

Probably Freud was the first to attempt a biographical inquiry into the psychic consequences of multiple mothering in his Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood . From the fact that Leonardo experienced dual mothers, a biological mother and an adoptive one, Freud derived the very shape and character of Leonardo's artistic and intellectual career as well as his sexual orientation. As many have recognized, Freud found and depicted in the pattern of Leonardo's childhood and career important features of his own development. His argument may have been weakened by scarcity of biographical data and an excess of interpretive zeal, but his method, if used cautiously, still offers us a useful model.

Powerful first-hand testimony about the mother-nurse-maid split in the American South comes from novelist Lillian Smith in Killers of the Dream . After speaking nostalgically about the body of her own black mammy, she presents the personal and social consequences of the dual mother split:

But this dual relationship which so many white southerners have had with two mothers, one white and one colored and

each of a different culture that centered in different human values, makes the Oedipus complex seem by comparison almost a simple adjustment.

Before the ego had gained strength, just as he is reaching out to make his first ties with the human family, this small white child learns to love both mother and nurse; he is never certain which he loves better. Sometimes, secretly, it is his colored mother" who meets his infantile needs more completely, for his "white mother" is busy with her social life or her older children or perhaps a new one, and cannot give him the time and concern he hungers for. Yet before he knows words, he dimly perceives that his white mother has priority over his colored mother, that somehow he "belongs" to her, though he may stay more with the other. . . . His colored mother meets his immediate needs as he hungers to have them met. She is easy, permissive, less afraid of simple earthy biological needs and manifestations. When naughtiness must be punished, it is not hers but the white mother's prerogative to do so; and afterward, little white child runs back to colored mother . . . who soothes him....

And now curious things happen. Strong bonds begin to grow . . . holding him to two women whose paths will take them far from each other.... His conscience, as it grows in him, ties its allegiance to [his white mother] and to the white culture and authority which she and his father represent. But to colored mother, persuasive in her relaxed attitude toward "sin," easy and warm in her physical ministrations ... he ties his pleasure feelings . . . A separation has begun, a crack that extends deep into his personality . . . His "white" conscience, now, is hacking at his early love life, splitting it off more and more sharply into [polarities like mother and nurse, madonna and whore, pure and impure, conscience and pleasure, marriage and lust].[12]

This passage expresses dramatically the feeling of being split between two primary loyalties. Whether or not Lillian Smith's portrayal of the moral tone of black mammies is objectively true, she expresses the meaning for a child of the class difference between its two mothers.

Beyond the personality and mothering instincts of the two women lies the caretaker's embeddedness in a specific cultural tradition. Erik Erikson's studies of the way various cul-

tural systems are encoded in traditional child-care practices depict the transmission of systems of value and behavior through the minutiae of the child-caretaker interaction. Ideally, caretakers' behavior conveys "a firm sense of personal trustworthiness within the trusted framework of their community's life style.... [Primary caretakers] must also be able to represent to the child a deep, almost somatic conviction that there is a meaning in what they are doing."[13] Should the meanings shift between two caretakers representing different cultural traditions, there is a risk of some flaw, however minute, in the development of basic trust.

Real-life experience of divided mothering appears to alter the functioning of the intrapsychic "good mother-bad mother" split described by object relations theory. For many of those who experience divided mothering, the gentle nurturing qualities cluster permanently around one of the two mother figures and the dangerous or threatening qualities around the other. The split contributes to a polarization of female attributes such that the two do not fuse in adulthood into a single realistic image of the mother as a whole woman comprising both positive and negative attributes. Integration into a single figure is necessary if the son or daughter is to be freed from domination by internalized mothers. As background for this study of Edith Wharton, I have examined the split-mother phenomenon in a variety of writers, not all of whom will be discussed here, and found in each instance significant consequences of that early experience. Among them are Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna, William Faulkner, Edgar Allan Poe, Lillian Smith, Ellen Glasgow, and Honoré de Balzac.

Of course, the consequences vary according to countless circumstances such as personality, gender, social class, and the age of the child when the nursemaid enters its life. Research into the psychology of creativity, such as that by John Gedo, suggests that "children destined for greatness" are particularly sensitive to the presence or absence of parental support.[14] The earlier in infancy the surrogate situation is established, the more marked are the consequences. As an infant,

Balzac lived in the home of his peasant wet nurse, to whom he was so powerfully attached that he was furious at being returned to his mother after weaning. He never forgave his mother for abandoning him to the nurse in the first place or for removing him from her in the second.

But even when the nursemaid is not present from the beginning, the child's attachment can be very deep. Biographers attest to the importance of a black mammy in the life and work of William Faulkner. Although scholars differ as to whether Mammy Callie was present from his infancy or entered his life when he was five, his personality and fiction indicate a deep split in his maternal imagery that can be attributed to this divided love. As Judith Sensibar observes in analyzing what she considers an early screen memory, two cousins stand for two contrasting mother-figures, the biological mother and the mammy.

[Cousin Vannye's] honey-colored hair looks inviting and seductive although she acts aloof and impersonal. But it is his other mother, the quick, dark Natalie (Caroline "Callie" Barr, his black nurse who cared for and lived with him from his birth until her death in 1940), who touches him and carries him. She offers him warmth and protection from "loneliness" and "sorrow."[15]

William Faulkner came to regard himself as one of his Mammy Callie's "white children" (the term he had inscribed on the tombstone he ordered for her). She was buried from his home, where, according to biographer Frederick Karl, she had been a "complete member of the household, beloved [and] respected."[16] Faulkner wrote to a friend:

She still remained one of my earliest recollections, not only as a person, but as a fount of authority over my conduct and of security for my physical welfare, and of constant affection and love. She was an active and constant precept for decent behavior. From her I learned to tell the truth, to refrain from waste, to be considerate of the weak and respectful to age.[17]

The experiences of Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna illustrate the patterns and variations I have found in the lives

of creative personalities who had multiple mothering from early infancy. Unlike Leonardo, Freud had his two mothers simultaneously, not sequentially, and both of them within the important first years of life. Freud's young, inexperienced Jewish mother turned over to a middle-aged Catholic servant woman the major care of this precocious and highly responsive child.[18] His letters to Wilhelm Fliess attest to the nursemaid's crucial role in the formation of many of Freud's personality traits and—even more important—to her significance in the formation of his most influential theories. As I show in a study now in preparation, the infant Sigmund's experience of primary nurturing divided between mother and nanny caused a corresponding division in his female imagery, so that all the earthy and seductive qualities adhered to his nursemaid and the idealized ones to his mother. In turn, this split helped shape his major theories—his paradigms of family relationships and his attitudes toward women—and helped prepare his mind for formulation of the oedipal theory.

His daughter Anna could be said to have had three mothers—Martha Freud, her birth mother; Martha's sister Minna, who lived with the family and shared household responsibilities; and a Kinderfrau named Josefine, a Catholic nursemaid who was brought into the family at Anna's birth and remained until the girl started school. Although Josefine cared for the older children as well, Anna was her main responsibility. Josefine was her "primary caretaker" and became what Anna Freud herself called her "psychological mother." Anna's tribute to Josefine underscores what I consider the prototypical pattern in mother-nanny splittings: adoration of the nanny at the expense of the mother. She called Josefine "Meine alte Kinderfrau, meine alteste Beziehung und die allerwircklichste aus meiner Kinderzeit" ("my old nursemaid, my oldest relation, and the most genuine of my childhood").[19] For a person outside the family to be deemed the "most genuine relation" of someone's childhood is a phenomenon deserving very serious attention.

Anna enjoyed the ideal situation of every nanny-reared

child. She was Josefine's undisputed favorite. After a gas explosion in the Freuds' apartment, Josefine first rescued Anna and then returned to see about the other children. When asked by the brothers, "'If there were a fire, who would you save first?' . . . she answered unhesitatingly, 'Anna' . . . and it constituted proof of what [Anna] felt: that she was Josefine's favorite, Josefine's—in effect—only child." Anna reciprocated the preference. While in a park with her mother and Josefine, she lost sight of the nursemaid and ran off desperately to find her, getting herself lost in the process. Says Elisabeth Young-Bruehl of this event, "Many years later, Anna Freud used this story to indicate that it was Josefine's attention that made her feel secure."[20]

With her mother, Anna Freud at best maintained an armed truce, according to the evidence marshaled in Young-Bruehl's recent biography. Anna found Martha Freud too controlling and excessively involved in conventional domestic details and appearances and suffered under Martha's disparaging views of Anna's appearance and clothes. Clearly, Anna vied with mother and Tante Minna for the position of companion, aide, and later caretaker to Sigmund Freud. Always jealous of her mother and succeeding to an unusual degree in gaining possession of her father, she seems never to have seriously considered marriage.

Throughout her life, Anna Freud sought in close ties with women the love she had experienced with her old Kinderfrau . Some of these women were professional mentors, others intimate companions. Finding that many of Anna Freud's female attachments were attempts to recover her lost relationship to Josefine, Young-Bruehl writes of the tie to Lou Andreas-Salomé, "the childless Frau Lou had entered into the line of succession to Anna Freud's good mother, the adoring Kinderfrau, Josefine, for whom she had been an only child. "[21]

With a Catholic nursemaid and a multiplicity of mother figures, Anna Freud's family constellation resembled that of her father. But the pattern of her personality shows remarkable analogies to that of Edith Wharton. Both women felt

superior to their mothers and identified with and were markedly attached to their fathers. Anna Freud actually succeeded to an extraordinary degree in displacing her mother as her father's helpmeet. Freud's pun on his favorite daughter's name, "Anna Antigone," points frankly to the oedipal character of their relationship. Edith Wharton's self-narrative connects the birth of her femininity and her literary gifts to the highly romanticized figure of her father. As a child she was acutely sensitized to whatever erotic signals emanated from that beloved man. What she may have made of such messages will be discussed in the next chapter.

Both women grew up feeling themselves to be physically unattractive, although they expressed their discomfiture in different ways. Edith Wharton tried to compensate with splendid clothes; Anna Freud gave up competition and dressed inconspicuously. Both were the youngest children in their families and were so eager to catch up with the older ones that they scorned children's books in favor of adult stories about "true" life. Both very early expressed their fantasy lives in literary inventions, wrote highly personal poetry, and were strongly cathected to material adjuncts of the written word, Edith Wharton to certain books, Anna Freud to pens and other writing implements.

As powerful professional women, both experienced problems in gender identity (what Anna Freud called a "masculinity complex") and struggled to accommodate both their ambitions and their need to give and receive nurturance. In their imaginative writings, both tended to identify with male characters. Both felt that their professional selves were masculine. They acted in the world as if they were males but expressed their maternal impulses in altruistic endeavors, such as caring for children displaced by war. Both were extravagantly fond of pet dogs; Wharton was rarely seen without at least one, and usually two, small lapdogs. Edith Wharton occasionally developed emotional attachments to children of her friends but, of course, did not make children her life work. Books were to be her offspring.

Most salient for our purpose here is the fact that both women adored their nannies and disparaged their mothers. And both, throughout life, sought various surrogates for their nannies, their lost "good mothers." Anna Freud found them in friends, colleagues, and mentors—members of her own social class. Although Edith Wharton had some women friends from her own milieu, she was emotionally dependent on a few servant women whom she kept close to her throughout life. With members of her own class, Wharton was a powerful and dominant figure, but her lifelong need for nurturance and dependency could best be met by working-class women. When the last of her beloved servants died she felt truly abandoned.

With Wharton as with many others, a loving mother surrogate somewhat ameliorated the consequences of maternal deprivation but did not fully compensate for it. Apparently a child's instinctive sensitivity to social class and power relationships tells it that the nursemaid, really a servant of the mother, lacks domestic and social authority. Wharton's memoirs and fiction tell us more or less directly that love without power within the child's own destined social world does not suffice to make it feel protected and prepared for life.

1—

Family Ties

"M'ama . . . non m'ama . . . ," the prima donna sang, and "M'ama!," with a final burst of love triumphant.

The Age of Innocence

Although Edith Wharton was endowed by nature with good health and an appetite for sensuous experience, she suffered in youth a repression of her sexuality so massive that she claims to have known virtually nothing of the "process of generation till [she] had been married for several weeks" ("Life and 1," 33–34).[1]

Her marriage to Edward Wharton was virtually celibate after this unfortunate beginning, so that her real sexual awakening was delayed until her mid-forties when she met and fell passionately in love with Morton Fullerton. She attributed her delayed sexual maturation and its attendant consequences to her mother's prudish exaggeration of the Victorian sexual code. Her childhood experiences served to magnify what social historian Peter Gay calls the "learned ignorance" about sexual matters imposed on women of Edith Wharton's time and class, the Gilded Age of old New York society.[2] Her socially prominent parents, George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander Jones, epitomized the conservative values of that society.

Wharton's depiction of the cult of female purity in The Age of Innocence reveals that women knew how to work within that convention, to maintain the appearance of innocence

while knowing well enough the important facts of life. In the words of May Welland, the incarnation of "factitious purity," "You mustn't think that a girl knows as little as her parents imagine. One hears and one notices—one has one's feelings and ideas" (149). Created in the author's late maturity, May Welland was granted a sophistication about sexuality that Wharton herself had lacked during her nubile years and was to acquire very painfully later in life. To a greater degree than others, the youthful Edith Wharton accepted the cultural fiction of female innocence and imposed it all too rigidly on herself.

She opens The Age of Innocence with Newland Archer entering his opera box in the midst of a performance of Gounod's Faust on the eve of his engagement, as Marguerite is singing "M'ama . . . non m'ama! . . . M'ama" ("He loves me, he loves me not, he loves me"). The words highlighted by this dramatic moment suggest a bilingual pun connecting love and mother, a pun derived from Edith Wharton's earliest affective life—mama, no mama, yet, after all, mama. Having a bodily mother whom she felt was no mother to her spirit, receiving compensatory love from a nanny, but having no single figure who reliably embodied the mothering function, young Edith had no mama, had two mamas, yet after all had one real mama who, by virtue of occupying the maternal space, exercised a powerful psychic sway. And the simultaneous having and not having of a mother contributed to difficulties throughout her affective life, so that when young she repressed all knowledge of sexuality, when married she lived celibate, and when she finally achieved sexuality in a midlife romance, she loved under adulterous and humiliating circumstances.

Mother and Nanny

The division that Edith Wharton experienced between the biological and the nurturant aspects of mothering resulted in a general tendency to psychic splitting that was to permeate

her feeling, her thinking, and eventually the very texture of her fiction. Nurturing, she tells us, came not from her socially preoccupied mother, but from a very devoted nanny. The contrast between the nanny's loving behavior and her mother's remoteness and judgmental attitudes magnified the normal intra-psychic split of good and bad mother.

The split that relegated to Lucretia Jones only the negative aspects of mothering—domination, intrusiveness, power to injure—created a pattern that would dominate Edith Wharton's psychic life and extend even beyond her mother's death. Once Lucretia Jones was cast into the role of the bad mother and became thus inscribed in her daughter's imagination, rectification of the mother-daughter relationship seemed almost impossible. The longevity of Wharton's anger is shown by her selection of illustrations for her memoir, A Backward Glance, which was written in her seventies, decades after Lucretia's death; she chose pictures of herself at various ages, several pictures of her houses, and portraits of her father, grandparents and great-grandparents and Henry James, but not a single image of her husband or her mother. The frightened child developed into an adult who spent considerable energy negotiating with her mother's influence, an adult who eventually achieved autonomy, but only at great cost.[3]

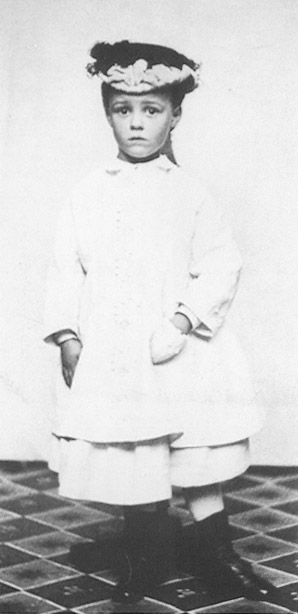

Outwardly, Edith Wharton's childhood situation was not exceptional for a girl of her class and time. She was born in 1862 into a socially prominent New York family that was "well-off, but not rich" if compared to such magnates as the Astors, to whom they were related through the Schmermerhorns.[4] The family of George Frederic and Lucretia Jones lived comfortably on money derived from municipal real estate, which allowed them a fashionable existence in New York and Newport until post-Civil War inflation forced them to economize by living for many years in Europe, starting when Edith was four. Being a quick learner and voracious for knowledge, she

acquired fluency in the major European languages and a taste for continental scenes, architecture, and culture. Building on this base, she would later educate herself in languages, philosophy, religion, and literature, well beyond the accomplishments of most women of her time.

After the family returned to America in Edith's tenth year, she enjoyed the social life of both New York City and Newport—nannies, governesses (but little formal schooling), parties, and a fashionable debut. Altogether, she had a masterful intellect, social position, sufficient wealth to lead a fashionable life, and a privileged variety of experiences. Her memoir, A Backward Glance, claims that her "little-girl life, safe, guarded, monotonous, was cradled in the only world about which, according to Goethe, it is impossible to write poetry" (7), that is, an environment so satisfying that it provides insufficient conflict to inspire an artist.[5]

But social and family conditions were not nearly so bland or so favorable as Wharton indicated. In "Life and I," an earlier and more candid manuscript version of her memoir, she reveals that she had felt neither cradled nor safe. For her, childhood was a series of terrors. She was worried, frightened, and subject to terrifying fears and compulsions. She suffered from wide emotional swings ranging from helplessness to grandiosity, felt divided between incompatible public and private selves, and was driven to extravagant and sometimes socially unacceptable activities.

By her own account, she suffered serious neurotic disturbances. She was afraid of animals other than small furry ones. Frequently she experienced terrifying panic attacks while waiting on the threshold of her parents' home, as if expecting that the door might be opened by a witch. She dreaded all tales of the supernatural, especially fairy tales, which feature good and bad mother figures—fairy godmothers, stepmothers, and witches.[6]

These fears were later converted into psychosomatic or neurasthenic illnesses, such as extreme reactions to minor

differences in temperature, nausea, anorexia, and asthma. In 1908 she wrote to Sara Norton:

Tell Lily . . . that for twelve years I seldom knew what it was to be, for more than an hour or two of the twenty-four, without an intense feeling of nausea, and such unutterable fatigue that when I got up I was always more tired than when I lay down. This form of neurasthenia consumed the best years of my youth, and left, in some sort, an irreparable shade on my life . . . I worked through it, and came out on the other side, and so will she.[7]

Wharton's agonizing symptoms conform remarkably well to those of the nineteenth-century neurasthenic woman as described by Elaine Showalter in The Female Malady . Although similar in many ways to hysteria, neurasthenia was considered a more "prestigious and attractive form of female nervousness than hysteria," comprising blushing, vertigo, headaches, neuralgia, insomnia, depression, and uterine irritability. With symptoms similar to those of hysterics, neurasthenics were thought to be more cooperative than hysterics, more ladylike and well-bred, more refined, and often more intellectually gifted and ambitious.[8] Neurasthenia like Wharton's was thought to result from sexual repression and other denials of bodily appetites in order to conform to a ladylike ideal, as well as to conflicts about "women's ambitions for intellectual, social, and financial success."[9]

Such pressures were particularly troublesome in Wharton's social milieu, which, in addition to fostering a repressive code of female behavior, distrusted intellectual ambition in general. Unlike Henry James, Wharton was born into the fashionable rather than the intellectual branch of the haute bourgeoisie, so that while living in America she had little contact with artists or literary people. As her friend Mrs. Winthrop Chanler put it: "The Four Hundred would have fled in a body from a poet, a painter, a musician or a clever Frenchman."[10] The part of Edith Wharton that identified with the values of her social set became uneasy about the artist and intellectual

that was emerging from within, causing her to cultivate that artistic self in secret. Confused and lacking support for her emergent self, she rigidified the socially validated self into a virtual parody of the proprieties. Said a Newport acquaintance from the intellectual set, "Our acquaintance was slight, she belonging to the ultra-fashionable crowd, and I in quite another group. Though the intellectuals and the fashionables met, they never quite fused. She was slender, graceful and icy cold, with an exceedingly aristocratic bearing."[11] The exaggerated quality of Edith Wharton's aristocratic demeanor was also related to fear of her mother's disapproval.

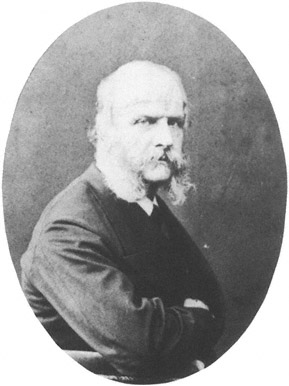

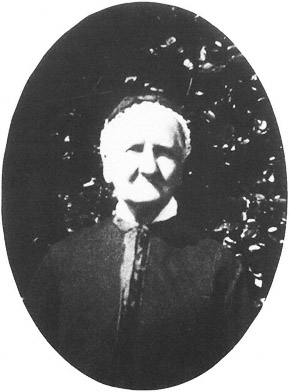

Wharton's memoirs point directly to disturbances in the mother-daughter relationship as the origin of her problems. She portrayed her mother as a beautiful, fashionable, narrowly conventional society woman of fairly trivial interests. At nineteen, after a fairly adventurous and partially secret courtship, Lucretia Rhinelander married Edith's father, twenty-three-year-old George Frederic Jones—handsome, well educated, and well-to-do—the typical New York gentleman of Wharton's stories.[12] After settling in Gramercy Park, the bride entertained frequently and lavishly, "taking her place among the most elegant young married women of her day" (Backward Glance, 18). Rumor has it that the expression "keeping up with the Joneses" derived from the grand social presence of Lucretia Rhinelander Jones.

But Lucretia's elegance was at least partly compensatory. Although she had grown up enjoying an aristocratic family position, by the time of her coming out the Rhinelanders were often short of funds. Lucretia had to attend her own debut in a home-made gown and ill-fitting second-hand slippers. With experiences vacillating between pride and humiliation, Lucretia felt so insecure that she needed to fortify herself with external signs of social position—rigid proprieties and an inexhaustible supply of splendid clothes from Paris. Said her daughter with empathic relief at Lucretia's eventual reputation as the best-dressed woman in New York, "At last the home-made tarlatans and the inherited satin shoes were

avenged" (18). Despite this apparent triumph, Lucretia was unable to impart social confidence to her daughter, who also tended to fortify herself with lavish clothes.

The couple had two sons, Frederic and Henry, who were respectively sixteen and twelve years older than Edith, the only girl of the family. When Edith was born, her father was forty, her mother thirty-seven years old. Family patterns and relationships were well established by this time, putting Edith into a fairly isolated position with regard to her brothers and even to her mother, who probably had little interest in returning to childrearing after so long an interval. The mother seemed distant, self-involved, and probably by this time more attuned to the ways of men than to the needs of a small girl.

Wharton's autobiographical documents depict her mother as cold, reproving, and remote. Motherly comfort came only from Doyley, her nanny. Here is the constellation as depicted in A Backward Glance:

Peopling the background of these earliest scenes there were the tall, splendid father who was always so kind, and whose strong arms lifted one so high, and held one so safely; and my mother, who wore such beautiful flounced dresses . . . and all the other dim, impersonal attributes of a Mother, without, as yet anything much more definite; and two big brothers who were mostly away . . . but in the foreground with Foxy [her dog] there was one rich all-permeating presence: Doyley—a nurse who has always been there, who is as established as the sky and as warm as the sun, who understands everything, feels everything, can arrange everything, and combines all the powers of the Divinity with the compassion of a mortal heart like one's own! Doyley's presence was the warm cocoon in which my infancy lived safe and sheltered; the atmosphere without which I could not have breathed. It is thanks to Doyley that not one bitter memory, one uncomprehended injustice, darkened the days when the soul's flesh is so tender, and the remembrance of wrongs so acute.

(26)

In the foreground of this family picture stand a nursemaid and a furry dog—someone to love her and something to love! And just as Doyley was the forerunner of Wharton's beloved

servant Catherine Gross, that furry dog was the first of many that were to follow Wharton throughout life. Edith Wharton was usually seen holding one or more small dogs, cradling them in her lap, or draping them over her shoulders. Despite the benign atmosphere of A Backward Glance, bitter memories and injustices did indeed survive, and some were recorded in her abandoned autobiography, "Life and I." There she gives quite a different picture—a poignant account of mother's failure to provide the warm cocoon and of the consequences of living without one.

In many expressions of Wharton's spirit these joys and deficits of her formative years were to be recapitulated—the arms of the knightly father, and two female divinities, one remote, impersonal, disapproving, and sometimes punitive, the other a sheltering cocoon with powers of divine comfort. The child felt herself subjected to supernaturally beneficent and maleficent powers that controlled her bodily sensations—temperature, shelter, and the very breath of life. This feeling was to accompany her throughout life, causing restlessness and dissatisfaction with any one place or set of circumstances. She was always on the move, seeking the right place to be.

Despite the elaborate social life Wharton was to maintain in both America and Europe, she felt lonely, and despite elegant dwellings on two continents, she rarely felt at home. As she says of her perpetually displaced character Lily Bart, "the being to whom no four walls mean any more than others is, at such hours, expatriate everywhere." Having been unable fully to possess the cocoon that Doyley spun around her, Edith Wharton repeatedly sought and furnished new homes, perpetually seeking patriation in a home that would contain all the warring elements of her personality.

Doyley's very virtues altered the balance of forces within the Jones family. She became a standard of comfort against which Lucretia Jones looked inadequate to her daughter. Responding with all her grateful love to Doyley's nurturance, young Edith must have failed to give Lucretia signals that would have stimulated her latent maternal impulses and elic-

ited warmer responses. The child must also have felt guilt for failing to love her mother and feared some retribution for giving to an outsider the love properly belonging to a parent. A negative cycle was generated between mother and daughter, with the mother reacting to the child's rejection and the child allowing negative imagery to fill the sacred maternal space. Lucretia came to seem like the God of Calvinism—vigilant, omnipresent, and unappeasable. Edith experienced a monumental need to placate this mother, a need so powerful that she offered up her own sexuality on the altar of this angry deity.

Such a cycle generates its own dynamics. Edith's image of her mother as a terrifying omnipresent power rendered the actual mother inaccessible for emotional support and ineffective in transmitting a model of capable femininity. Rejecting her mother, Wharton willed herself to be unlike Lucretia Jones in important ways. She tried to emulate her mother's elegance but rejected her role as an adult sexual being and mother. This separation of ornamental beauty from adult female sexuality is the genesis of Wharton's most touching figure, the exquisite Lily Bart, who seeks a husband but unconsciously sabotages every incipient union. In general, Wharton characters who are fitted by nature to relish the pleasures of life but always undermine their own hopes are revenants of the ardent Edith Wharton, a "life-lover" who so managed her affairs as to frustrate her own urgent desire for love and sexual fulfillment.

Receiving most of her nurturance from a surrogate mother added a deep insecurity to Edith's young life. Although Doyley remained with the Jones family well beyond Edith's infancy, she must have had day's off when the child feared she might never return. Knowing that Doyley was a salaried employee, Edith must also have feared that she might be dismissed. Attachment to Doyley and her later surrogates did not compensate for the maternal deficit, mainly because even the divine Doyley did not and could not suffice to fill the maternal role. Young Edith's polarization of the two women

attributed to the mother power without love, to the nanny love without power. With mother perceived sometimes as a dim, aloof figure, sometimes as a punitive deity, and with nanny adored as an all-loving—but powerless angel, the child stood frozen between mutually canceling antitheses. As a remedial figure of Wharton's childhood, Nanny Doyley ameliorated the child's sense of maternal deprivation, but as a domestic servant without power in Wharton's destined social world, she lacked authority. A servant is not a mother, at least not while the real mother is present. Doyley's visibly subordinate position in the household prevented her from assuming full maternal powers in Edith's mind. Motherhood is more than comfort, it is power and social efficacy, attributes belonging to the biological mother—to the mistress of the house and wife of the father.

To elaborate Melanie Klein's imagery of the good and bad breast (which can be intensified when the split images derive from separate maternal figures), each extreme implies its opposite. Doyley's very goodness evoked her polar negation—a persecutory biological mother who is both wronged and wronging. Having hypostatized the rejected mother into a hostile force, a vengeful Fury, Edith consumed considerable energy in efforts at appeasement. The sacrifices she made to this image, sacrifices of sexual curiosity and denial of sexual impulses and all that followed from such repressions, served to increase her anger and thereby her guilt.

The persecuting image of Edith's mother as judgmental, forbidding, aloof yet omnipresent, may have been a projection of the child's need for punishment rather than an accurate description. To some degree, Lucretia Jones probably was self-centered and preoccupied, but Wharton's own memoirs contain evidence that her mother cared about her. The record is contradictory. Wharton reports her parents' concern when she came near death from typhoid fever at a German spa in her ninth year. In their despair the parents daringly secured advice from the czar's personal physician, who prescribed plunging the child into ice-cold baths. "At the suggestion my

mother's courage failed her; but she wrapped me in wet sheets, and I was saved" (Backward Glance, 41).

Mother and daughter took frequent carriage rides and made social calls together. Although young Edith felt herself to be homely and awkward in comparison to her beautiful mother, Lucretia Jones commissioned many paintings and photographs of her daughter and displayed them prominently.[13] Lucretia not only supervised Edith's reading but paid scrupulous attention to her diction and usage. She denied her daughter writing paper, so that the child had to write on discarded wrapping paper, but bought her a prized volume of poetry for her birthday. Although she seemed not to encourage Edith's creative writing, she tried to jot down the child's improvised oral narrations and, as Edith discovered after Lucretia's death, even saved copies of the child's letters to aunts and other relatives ("Life and I," 15). What was probably the most misguided of her attempts to relate to her daughter was her publication of Edith's adolescent verses without the girl's knowledge or permission.[14] This intrusive violation of her daughter's privacy was probably intended to be a pleasing surprise.

Regardless of the historical truth about Lucretia Jones, the internalized mother was experienced as a persecutory figure.[15] Wharton wrote of having suffered "excruciating moral tortures" that seemed derived from her mother but were actually self-imposed. She recognized that her parents, nanny, and governesses really had not preached, scolded; or "evoked moral bogeys." Indeed, she found that her parents were "profoundly indifferent to the subtler problems of the consciousness. They had what might be called the code of worldly probity." Mother's rule was politeness, father's was kindness; and the only behavior they really condemned was ill breeding. They had not even treated lying as particularly naughty:

My compunction was entirely self-evolved .... I had never been subjected to any severe moral discipline, or even to that religious instruction which develops self-scrutiny in many children . . . I had, nevertheless, worked out of my inner mind a

rigid rule of absolute, unmitigated truth-telling, the least imperceptible deviation from which would inevitably be punished by the dark Power I knew as "God." Not content with this, I had further evolved the principle that it was "naughty" to say, or to think, anything about anyone that one could not, without offense, avow to the person in question.

["Life and I," 4–5; italics added]

Her moral suffering came from the conflict between her own impossibly high standards of truth and her mother's "code of worldly probity." The conflict was dramatized when she was berated by her mother for expressing publicly her thought that a certain elderly woman was as ugly as an old goat: "For years afterward I was never free from the oppressive sense that I had two absolutely inscrutable beings to please—God & my mother—who, while ostensibly upholding the same principles of behaviour, differed totally as to their application. And my mother was the most inscrutable of the two" (6–7).

With this oppressive presence the daughter craved to be reconciled. Through fiction she tried to imagine ways of freeing herself from guilt and from fear of her mother's punitive rage. She needed to bring her good and bad mother-figures into relationship—to fuse them into a single image of competent, authoritative, and reliable nurturance. She searched her imagination to create a usable maternal presence that would meet her unsatisfied infantile needs and also be capable of leading her into full womanhood.

She juxtaposes to an account of her burgeoning sensuality the anguish of being shamed by her mother for seeking sexual enlightenment:

Life, real Life, was . . . humming in my blood, flushing my cheeks and . . . running over me in vague tremors when I rode my poney [sic] . . . or raced & danced & tumbled with "the boys." And I didn't know—& if ... I asked my mother "What does it mean?" I was always told ... "It's not nice to ask about such things." . . . Once, when I was seven or eight, an older cousin had told me that babies were not found in flowers, but in people. This information had been given unsought, but as I had been told by mamma that it was "not nice" to enquire into

such matters, I had a vague sense of contamination, & went immediately to confess my involuntary offense. I received a severe scolding, & was left with a penetrating sense of "notniceness" which effectually kept me from pursuing my investigations farther; & this was literally all I knew of the processes of generation till I had been married for several weeks....

A few days before my marriage, I was seized with such a dread of the whole dark mystery, that I summoned up courage to appeal to my mother, & begged her, with a heart beating to suffocation, to tell me "what being married was like." Her handsome face at once took on the look of icy disapproval which I most dreaded. "I never heard such a ridiculous question!" she said impatiently; & I felt at once how vulgar she thought me.

But in the extremity of my need I persisted. "I'm afraid Mamma—I want to know what will happen to me!"

The coldness of her expression deepened to disgust [and the question went unanswered] . . . I record this brief conversation, because the training of which it was the beautiful and logical conclusion did more than anything else to falsify & misdirect my whole life .

("Life and I," 33–35; italics added)

The fear of being thought unclean appears to have driven out whatever sexual knowledge Edith had picked up through her friends, her experience, and her extensive reading. She would not allow herself even to think whatever her mother decreed to be "not nice." Believing that mother could monitor even her thoughts, she effectively banished sexual knowledge from her mind, even to the point of believing "that married people 'had' children because God saw the clergyman marrying them through the roof of the church!" (34). The illusion of maternal omniscience generated such exaggerated compliance, such extreme scrupulosity, that her entire sexual nature—feelings along with knowledge—were driven underground.

Riven by such conflicts, Edith Newbold Jones was so unprepared for her marriage in 1885 at the age of twenty-three that for the next twelve years she suffered depression, nausea, and headaches. In 1898, thirteen years after the wedding, she required several months of residential psychiatric treatment. Her account of her mother's refusal to impart any sexual infor

mation, even when implored for it on the eve of the wedding, is now a famous part of Wharton folklore. Even if true as reported, the kind of total ignorance that Edith professes must be attributed as much to her own repression as to her mother's prudery. I suspect that then, as now, few women first learned the "facts of life" from their mothers or required elementary instruction on the eve of their weddings. If M. Jeanne Peterson's study of Victorian gentlewomen is applicable to American women of Edith Wharton's class and generation, they "knew about sex and had levels of tolerance about sexual matters and sexual misbehavior that belie the Victorians' reputation for prudery."[16]

Edith certainly was exposed to the usual stimuli that arouse sexual inquiry. She had many friends, especially among the boys of her acquaintance, whom she much preferred to girls. Her earliest recorded memory is of a highly pleasurable kiss from a small boy cousin, and she had two older brothers. She records episodes of flirtatiousness, which must have generated some somatic awareness of sexuality. In "Life and I" she documents a very normal curiosity about the first acts of husbands with respect to their brides: I confess to a weakness for 'the Lord of Burleigh,' based I think, on its documentary interest as a picture of love and marriage (Subjects which already interested me profoundly.) From this poem I drew the inference that a husband's first act after marriage was to give his wife a concert ('and a gentle consort made he')" (9).

Another childish verbal misunderstanding illuminates the nexus in the child's imagination of adulthood, sexuality, and guilt. She had pondered the similarity between the words "adult" and "adultery "—noting that "persons who had 'committed adultery' had to pay higher rates in travelling (probably as a punishment for their guilt), because I had seen somewhere ... the notice, 'Adults 50 cents, children 25 cents'" (10). These examples indicate that considerable mental energy had been devoted to sexual investigation, bearing out Freud's

view that speculation about the sexual activities of parents is the origin of intellectual curiosity—our first important attempt to puzzle out the unknown. He surmised that children would divine the facts of generation even if never informed of them.[17]

Puberty and menstruation must have raised additional curiosity. After her early debut at seventeen, she joined a social circle of young married women, who must have communicated something of the realities of married life. If she really arrived at marriageable age believing that women become pregnant because God sees their weddings through the roof of the church, what prevented so intelligent a person from checking out this unlikely supposition?

Rather than join the general indignation against Lucretia Jones for her purported rejection of Edith's prenuptial questions about what happens to women when they marry, I am tempted to echo Lucretia's observation that Edith must have noticed that men and women are made differently, and that she "can hardly be as stupid as she pretends."[18] The not-quite-credible wedding eve story may reflect displaced anger at Lucretia Jones's astonishing omission of Edith's name from the invitations to her own wedding, which reads, "Mrs. George Frederic Jones requests the honor of your presence at the marriage of her daughter to Mr. Edward R. Wharton, at Trinity Chapel, on Wednesday April Twenty-ninth at twelve o'clock."[19]

Edith's request for sexual information could have masked a shy desire for intimacy with her mother—a sharing of womanly secrets. The Old Maid, Wharton's fictive treatment of such an interview on the eve of marriage, clearly points less toward sexual instruction than toward mother-daughter intimacy just before the daughter's entry into the married state. Imparting such information before a wedding may be a ritual designed to transmit female adulthood from mother to daughter, and this transmission is exactly what failed to occur in Edith Wharton's development.

The "No" of the Mother, the Realm of the Father

Wharton's conceptions of power, gender, and sexuality were derived from the complex politics of her family constellation. The partial displacement of Lucretia Jones by a nursemaid affected Edith's sexual development by altering the dynamics of the oedipal phase and making space in the child's psyche for unusually florid incestuous fantasies. Lucretia's inability to hold onto her own daughter's affection may have suggested a similar slackness in her hold on her husband, leaving a power gap into which the child's imagination might enter. And, as I discuss more fully in Chapter 4, the split maternal image might have suggested a fancy that her brother's tutor and not George Frederic Jones was really her father, thus rendering Mr. Jones more available as an object of sexual fantasies. Given the extravagance of Edith's imagination and the energy she put into sexual investigation, there are manifold possibilities for elaboration of the forces within the family system.

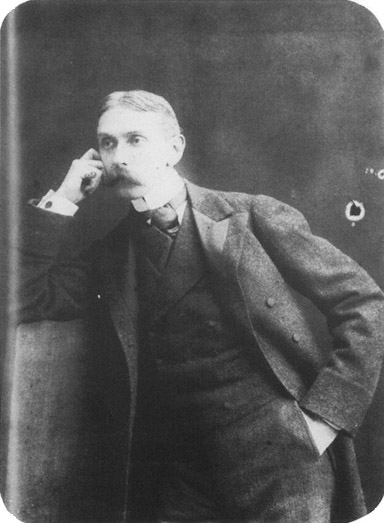

Balancing the two female figures of her childhood was the "tall, splendid father who was always so kind, and whose strong arms lifted one so high" (Backward Glance, 1), a figure who, unlike the mother, was immune from the rancor of childhood disappointments. Edith idealized him and identified with him. Married shortly after his graduation from Columbia College, he inherited enough money that he never had to work for a living. He lived a life of gentlemanly leisure, occupying himself largely with work on the boards of charitable and cultural institutions.

The recollection of a proud childhood walk with him is the opening note of A Backward Glance . In this radiant memory Wharton found the formation of one aspect of her selfhood: I may date from that hour the birth of the conscious and feminine me in the little girl's vague soul" (2). With her father as the mirror of her fine appearance, she came to experience

herself as a "subject for adornment." Her pride in being daddy's pretty little companion includes a romantic attachment to this handsome father, competition with her mother for this position, and a compassionate loyalty to him.

But as Adrienne Rich says, a nurturing father "must be loved at the mother's expense."[20] Edith saw her father as a fellow victim of Lucretia's materialism and social ambitions. During the Civil War years, the Jones income suffered from fluctuations in real-estate values, causing the family to spend about eight of Edith's childhood years in Europe to reduce expenses. Edith remembered her father bent over his desk in "desperate calculations ... in the vain effort to squeeze my mother's expenditures into his narrowing income."[21] To this image of paternal worries she juxtaposed that of her mother as a "born shopper" who indulged in unnecessary buying until the money "gave out."

She tended to visualize her father in his library, a small room decorated in the Walter Scott tradition, with an oak mantelpiece "sustained by vizored knights." The room was "lined with low bookcases where, behind glass doors, languished the younger son's meager portion of a fine old family library."[22] This typically Victorian "gentleman's library" became Edith Wharton's schoolroom, her university, and her emotional center.

Beginning to sense her own mental powers, Edith turned to her father as the source of what she valued most in herself and to his library as the locus of her most valued experiences. With important consequences for her artistic persona, she came to regard him as the generator of her literary self. He taught her how to read and introduced her to poetry: "My first experience of rhyme was the hearing of the "Lays of Ancient Rome" read aloud by my father . . . The metre was intoxicating" ("Life and I," 9).

She found or read into this mild, wife-dominated gentleman a love of poetry and a literary talent frustrated by his wife's prosaic values. She wrote, expressing great pity for his lost sensibilities:

The new Tennysonian rhythms also moved my father greatly; and I imagine there was a time when his rather rudimentary love of verse might have been developed had he had any one with whom to share it. But my mother's matter-of-factness must have shrivelled up any such buds of fancy . . . and I have wondered since what stifled cravings had once germinated in him, and what manner of man he was really meant to be. That he was a lonely one, haunted by something unexpressed and unattained, I am sure.

(Backward Glance, 39)

The polarizing tendency described above with respect to the dual mother figures was also at work in Wharton's imagery of her two parents. She perceived them as negations, of each other, with all the good directed toward the father. Onto him she projected her own sense of victimization by a female, so that Lucretia seemed to shrivel the soul of this sensitive man. Wharton's fiction frequently echoes this pattern of shy male sensibility sacrificed to female crassness.

Edith's father gave her the freedom of his library. Her mother read novels avidly but forbade them to the daughter because of their sexual content. Young Edith obeyed her mother's rule but used her library privilege to frustrate its intent. She must have been something of a casuist, evading the ban on novels by reading plays, the first that she recalls being about a prostitute. From her readings in the Bible, poetry, and Elizabethan drama she must have found all the clues she needed to surmise "the facts of generation," but feeling guilty about knowledge forbidden by her Mother, managed to repress it. Lucretia Jones's prudery triumphed better than she knew or intended—Edith became distanced from her developing erotic feelings and transferred all her passion into the area of books and imagination.

She developed a rapturous relationship to the written word, to which her beloved father had introduced her. His library became a "secret garden," a locus of virtually ecstatic experiences, from the sensuous pleasures of luxurious bindings to those of the expanding imagination: "Whenever I try to recall my childhood it is in my father's library that it comes

to life. I am squatting on the thick Turkey rug . . . dragging out book after book in a secret ecstasy of communion . . . There was in me a secret retreat where I wished no one to intrude" (69–70; note the identification here of the library with her self or her body).

Activities connected with books, whether hearing stories read, making up her own stories, or browsing among the books, are described in "Life and I" in orgasmic language. She experienced a "sensuous rapture" from the spoken and written word even before she knew how to read. She tells of a "devastating passion" for the process of "making up," which consisted of pacing the floor holding a specific book (often upside-down) and ecstatically pouring out invented tales as if she were reading them. She managed to turn the pages at approximately the right intervals, hoping that the watching adults believed she could read. The rapture was tied to specific editions of specific books, so that "invention flagged unless I had the right print." She was under such urgent compulsion to repeat this activity that she would have to abandon playmates in order to relieve her tension at fairly frequent intervals.