Preferred Citation: Brown, Jonathan C. Oil and Revolution in Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb28s/

| Oil and Revolution in MexicoJonathan C. BrownUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1993 The Regents of the University of California |

For G. Franklin and Cynthia Ingalls Brown

Preferred Citation: Brown, Jonathan C. Oil and Revolution in Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb28s/

For G. Franklin and Cynthia Ingalls Brown

Preface

This book may be about Mexico's future as well as its past. After a decade of economic decline, the country's politicians have begun a crusade to integrate Mexico into the world economy and to attract foreign capital. Historians are right to view the new openness with some skepticism. They have, after all, seen it before. At the end of the nineteenth century, Porfirio Díaz once accomplished what Mexico's leaders are now attempting. That exceptional period of economic modernization was succeeded by a revolution. No careful academician claims to foresee the future, but I would suggest that the road the Mexicans travel during the next several decades will be a familiar one. A historical journey over the old route, therefore, would be profitable.

So many persons have helped me in this endeavor that I find it difficult to name them in order of importance. Somewhere near the top of the list would be the late Henrietta Larson, who launched me on this project a decade ago when she sent me her materials on the Latin American operations of the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey). John Tutino deserves credit for telling Larson about me. Together, they helped me return to academia.

My pursuit of the documentary evidence was assisted by Ed Glab, John Oldfield, and L. Philo Maier for Standard Oil; Geoff Jones, A.F. Peters, and Veronica Davies for Shell; Kay Bost and Dawn Letson for DeGolyer; Michael C. Sutherland, Rita S. Faulders, and Msgr. Francis J. Weber for Doheny; Pablo Casanova and Carlos Lomelín for Pemex; and Friedrich Katz with lots of leads.

Student research assistants have been instrumental in collecting (and understanding) much of the material. I have had the capable services of Kurt Weyland, Kevin Kelly, Joe Schreider, Elizabeth Feldmann, Alfredo Poenitz, and Adrian Bantjes.

The researcher also needs financial patronage. I have been assisted by grants from the American Council of Learned Societies and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Texas at Austin has been generous as well: I have received assistance from the Public Policy Research Institute, the University Research Institute, the Mellon research fund of the Institute of Latin American Studies, and the Dora Bonham endowment of the history department.

Numerous persons also gave freely of their material and spiritual encouragement. Jack Womack and John Wirth wrote often and unsparingly, offering advice and letters of support. Others include Mira Wilkins, Alfred Chandler, Laura Randall, Colin Lewis, Jordan Schwarz, Eric Van Young, George Baker, Michael Meyer, and Jim Wilkie. Tina and Freddy Kent gave me shelter in London and took in my family too. Bruce and Jean Wollenberg and Kay Willis put up with us in Santa Barbara; Marty and Carolyn Melosi tolerated us in Washington, D.C., even though they live in Houston. How can I forget Chitraporn Tanratanakul, with her "placas diplomáticas" whisking me through the Mexico City traffic? Both she and Enrique Ochoa collected my microfilm and photocopies long after I had gone. In Mexico, Carlos Marichal, Juan Manuel de la Serna, Jorge Ruedas de la Serna, Cristina González, Víctor Godínez, and María Elena Brady provided hospitality. Pieter and Gesina Emmer and Stan and Ruth Brown offered hospitality in the Netherlands and Germany. I owe special thanks to Max and Ethel Gruber, who helped us during the hard times.

Among those who read and commented on parts of the manuscript were Patrick Carroll, Peter Linder, and Alan Knight (the latter, an inspirational colleague during his tenure as a Longhorn). But Steven Topik saved the book by introducing me to the University of California Press. Editor Eileen McWilliam and two outside evaluators reviewed the manuscript in record time, and now the readers can judge the result.

In the years it took me to research and write this book, the members of my family continued their own quests. Lynore moved with me from Santa Barbara to DeKalb to Austin. While pursuing her own career in education administration, she provided me with the kind of advice every author needs. Each of her suggestions has been right. Jason, who

had already survived one book, went from grade-school to university student, and Adam moved from the cradle to grade school. It all proves that time does not stop just because one guy wants to relive the past.

A final caveat is in order. I did not realize until two years into this project that the oilman Edward L. Doheny and I had been born and raised in the same hometown — Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. An old colleague from the Fond du Lac Reporter, Stan Gores, had even written about him. Subsequently, my mother and father informed me that Doheny had long ago donated the library at the public high school. How's that for fine irony? One kid goes forth from Fond du Lac to gain wealth and fame, and the other to write about him.

Introduction:

Compromising the Forces of Change

Mexicans have a saying: "What would we do without the gringos? But we must never give them thanks."[1] Perhaps the greatest debt Mexico owes to the United States remains the economic modernization of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Americans contributed capital, materials, and skills to develop the modern railways that reduced the country's long-standing regional and mountainous barriers. Americans brought in steam boilers, ore crushers, pumps, and blast furnaces to resuscitate the decrepit mining industry. They introduced sanitation works, power and light plants, telegraphic services, and trolley systems to cities. They brought in hoists and dredgers to build modern ports. Foreigners also purchased land, contributing new techniques and tools to expand Mexico's production of foodstuffs, tropical products, and hemp.

Finally came the foreign oilmen. First, they developed Mexico's market for imported fuel used in illumination and motive power, converting the economy to this modern source of industrial energy. Foreign oil companies then expanded the country's production and refining of petroleum products for export. Nonetheless, the hosts did not view the petroleum industry developed by foreigners as an unrelieved blessing. Mexicans accused the wealthy companies of financing reactionary political movements, dividing and repressing the workers, extracting the nation's nonrenewable resources, and subordinating domestic needs to international interests. Native oil laborers resented the companies for giving foreign workers the privileges and pay denied to

most Mexicans. In 1938, when thousands of Mexicans gathered at the Zócalo to celebrate the expropriation of the foreign oil companies, one of their banners read "Gentle Patria: the Christ Child bequeathed you a country and the devil, your veins of petroleum."[2]

How can one explain the Mexican ambivalence toward the fruits of the Industrial Revolution? Did the petroleum industry relegate Mexico to Raúl Prebisch's economic periphery, giving up its wealth to the industrial center because the terms of trade undervalued raw materials and overvalued manufactured goods? Did economic development generate growth and power for the few and poverty for the many, as the dependentistas might say? Did it create a Wallersteinian world system in which the local elites sold out to the foreign interests and oppressed the workers? Did "monopoly capital" follow the pattern described by Braverman, rendering the Mexican proletariat a deskilled, hapless lump that could not shape its own world?

This study rejects those scenarios. But it also finds unrealistic the neoclassical analysis that predicts that less-developed countries find salvation in imitating the industrial nations.[3] Those contemporary observers who believe Mexico's current policies of privatization and free trade to be the wave of the future might take heed of that nation's historical experience with the oil companies. There is no doubt that Mexicans desire the benefits of capitalism. But their own history has taught them to be wary of the undesirable consequences that unregulated capitalism might produce when confronted with the country's more rigid political and social structures. The fact is, Mexico cannot travel the shining economic path of the United States. Nor does it want to.

Mexico and other Latin American countries share one commonality: their societies have been born and reared in extreme social diversity. Every Mexican searches for his or her identity amid the social plurality and inequality of the multiracial colonial order. Many racial, ethnic, regional, and even language groups have formed the country's heritage. Octavio Paz has written that Mexico has "a history of man seeking his parentage, his origins."[4] Historically, the problem of maintaining unity among such diverse peoples, from the period before Conquest to the present, has led to the perfection of authoritarian methods of social domination and political manipulation. When the oil companies arrived in Mexico, the elite still formed a narrow minority, jealous of its prerogatives and contemptuous and fearful of its social inferiors. Private schooling and political connections beyond the reach of the "havenots" enabled the "haves" to reproduce their social superiority from

one generation to the next. The middle classes imitated the mores of their superiors and sacrificed to keep from sliding backward into the disreputable working class. Persons with dark skin and native cultures were ridiculed and shunned. They found themselves consistently at the lowest end of the socioeconomic order. Even the working class had its own hierarchy of prerogatives and organization. The skilled descendants of Europeans (in attitudes if not race) maintained a privileged position over the less-educated, less-skilled lumpen proletarians. The peasantry itself, disdained by the elite and urban worker alike, retained the closest ties to the Indian past. For workers and peasants, either religious orthodoxy or nationalism in the Gramscian doses prescribed by the elite had substituted for a healthy distribution of income and opportunities. Paternalism and coercion at all levels contained the various components of this social hierarchy, preventing them from bursting their bounds.

A pluralistic nation may not be able to accept change with equanimity. Economic change disrupts a society made up of many unequal parts to a greater degree than it would threaten a more homogeneous one. Mexico, whose history was richer and more complex than that of most countries, typified the built-in safeguards with which Latin Americans often confronted change. Mexicans attempted to manage change, modernization, or the introduction of things foreign, by rearranging its new social and political relationships according to traditional patterns of behavior. This is not to say that Mexico's twentieth-century corporate state and social inequality perfectly reflect the royal absolutism and caste society of the colonial period. But they have preserved social behaviors developed at that time. It could be argued that social hierarchy accounted for the preservation of political authoritarianism and, subsequently, for the perversion of modern capitalist stimuli in the interests of containing social unrest. As a force for change, economic growth posed a serious challenge to a society that had not been accustomed to dividing property strictly according to economic criteria. In Mexico, social position and political connections had always influenced one's access to economic benefits.

Research in Mexican labor and political documentation as well as in foreign diplomatic and business archives confirms that Mexico's economy cannot be separated from its politics. Yet, the greatest revelation of all has been the primacy of Mexico's social heritage. In few other national histories have the complexities of the preindustrial social order been more evident than in Mexico: the thin, privileged, and fearful

European upper crust; the competitive, vulnerable, and racially mixed middle strata; and the mass of Indian peasants and day laborers, suffering abuses and saving up grudges. This might have been the cauldron in which Barrington Moore prepared his recipe for the social origins of authoritarianism.[5] But it was not. If they study only Western European and North American historical evolution, the theorists hardly account at all for the kind of ethnic and racial complexity encountered in Latin American societies.

Therefore, I have strived to write a comprehensive history. This book analyzes the reasons for and the consequences of the operations of the American and British oil companies in Mexico between 1880 and 1920. More than a business or economic history might acknowledge, those consequences challenged the very political and social order of the host nation. Chapter 1 concerns the entry of foreign entrepreneurs into Mexico. It demonstrates that they had to expand just to survive the growth of international trade in petroleum. Foreign entrepreneurs succeeded because of their earlier experience in oil production, their vast financial resources, their ability to satisfy both domestic and international markets, and the failure of Mexican entrepreneurs to compete on the same level. At the same time, the activities of the foreign companies became inextricably bound to the political and social breakdown that was already leading the country to revolution. Chapter 2 deals with the operations of the foreign oil companies in the first Mexican oil boom. It places Mexico in the international economic context, showing why and how the companies expanded even as Mexico became engulfed in the first social revolution of the twentieth century.

Chapter 3 offers an unusual explanation for economic nationalism. It demonstrates how the unfettered operations of foreign capital in Latin America were incompatible with the historic relationship between the working class and the state. Most studies emphasize the naughty behavior of the foreign companies and the offended sensibilities of national politicians. My analysis suggests that economic nationalism contains social considerations that are too often neglected. Chapter 4 criticizes many trite, oft-repeated misconceptions about the collusion of foreign interests and domestic reactionary forces. The relationship between foreign oilmen and the "counterrevolutionary" caudillo, Manuel Peláez, has stirred considerable conjecture in the historical debate concerning the Mexican revolution. Was Peláez only the political tool of the foreign interests? In fact, the companies fell victim to a local political struggle only tangentially linked to the role of for-

eign enterprise in Mexico. Nor should one lose sight of the acute social impact of foreign investment. The petroleum industry proved a contradictorily powerful force for both improvement and insecurity in the lives of its Mexican workers. Their collective response, the militancy described in chapter 5, bespeaks the workers' commitment to their own preindustrial values as well as their desire to create their own place in modern industrial society. As each chapter will show, Mexicans of all classes attempted to mold the oil companies to domestic standards — if only to prevent modern capitalism from shattering Mexico's political and social structures.

Returning to the original question: Why cannot the Mexicans show their gratitude? The answer is paradoxical. Every economic benefit that crossed Mexico's northern border also contained its own peril. As the experience of the foreign oil companies makes clear, Mexicans sought to compromise the forces of economic change to a social heritage stronger than modernity itself.

Chapter One—

Not All Beer and Skittles

The Porfiriato, that period of Mexican history dominated by General and President Porfirio Díaz, from 1876 to 1911, was a time of unprecedented economic expansion. Compared to the economic decline and political instability that had plagued Mexico since the beginning of the rebellion for independence in 1810, the Díaz administration seemed to have provided peace and prosperity. Exports grew by 5.6 percent per annum, national income by 2.3 percent, population by 1.4 percent, and per capita income by .93 percent. Foreigners found Mexico so attractive that they pumped an estimated 3.4 billion pesos into the country by 1911. Depending upon their own national economic strengths, foreign investors specialized in different sectors of Mexico's economy. French and Dutch capital financed the public debt. The Germans invested in manufacturing; the Americans, in mining and later petroleum; Britons and Canadians, in public utilities; and the Americans and Britons, in railways. It was said that two-thirds of all capital investment in Mexico, outside of the agriculture and handicraft industries, came from foreign sources. The United States led all investors, but Mexican political encouragement had developed effective competition from British and French capital investments as a foil to U.S. economic dominance. A coterie of immigrant entrepreneurs developed a vibrant domestic manufacturing sector. Political supporters of Díaz often reminded Mexicans of these basic facts. They neglected to mention, however, that the distribution of income remained skewed toward the elite.[1]

Growth of the economy, in turn, generated growth of the Mexican market for petroleum products, lubricants, and illuminants. Railways, mining operations, domestic and export agriculture, industrial and artisan manufacturing, and internal consumption all expanded. In the oil tank car, railways provided an efficient method of bulk transport. The trackage of Mexican railways expanded from 1,073 to 19,280 kilometers between 1880 and 1910. The moving stock of trains needed lubricating oils. So did agricultural processing equipment and the machinery in the mining, textile, and agricultural export industries. In the cities, increasingly prosperous and sophisticated consumers purchased imported lamps that burned kerosene. Kerosene lanterns also became standard equipment in a number of industries, and parlor oil stoves for home heating appeared in the homes of the well-to-do when fuel became more widely available throughout the nation. Even the Irishmade light buoys, equipped with oil lamps and placed by the Mexican government at the entries of the nation's harbors, had tanks large enough to hold fuel for a month of steady light. Nineteenth-century mining operations were starved for fuel, because deforestation hampered the use of wood for the steam boilers of the mines. American investors reopened some colonial mines and applied modern technology to the extraction of silver and gold from low-grade ores. Coal, copper, and lead also came to be mined.[2]

Mexico's domestic market, nonetheless, did little to stimulate Mexican private entrepreneurship in the production of petroleum. Several early Mexican efforts to produce, refine, and sell oil products had failed. To develop the infrastructure of a successful private marketing business in Mexico, the entrepreneur needed capital, management skills, and technological expertise. These commodities, developed in more advanced capitalist economies, meant that only foreigners with prior experience in the oil business could succeed. Their success may have forever blocked effective competition in petroleum from Mexican entrepreneurs. More than that, the foreign entrepreneurs came from another world, not a seignorial but a business world.

American businessmen such as Henry Clay Pierce and Edward L. Doheny found a kind of logical interest in the Mexican marketing and production of petroleum. After all, the United States shared some 1,952 miles of border with Mexico. ("Poor Mexico," Porfirio Díaz supposedly remarked, "so far from God and so close to the United States.") When Standard Oil began exporting Pennsylvania petroleum products, Mexico along with Canada and Cuba represented the nearest

foreign markets. A second rationale for American investment in the Mexican oil industry concerned the earlier American investment in the critical element of Mexico's economic modernization, the railways. Nevertheless, American oilmen had competition not from Mexican entrepreneurs, who in any case lacked the capital and technological resources, but from the British — specifically from Sir Weetman Pearson.

These entrepreneurs operated in the half century before the First World War, the initial stage of economic modernization in Latin America.[3] How much of the results of this growth can be attributed to external forces, represented by foreign investment and technology? How much to internal forces, represented by economic policy and sheer political will? Can scholars distinguish the outcomes of policy from those of politics? Mexican politicians struggling among themselves for power have had an important role in shaping their nations' modern economic environment. Foreign entrepreneurs, therefore, owe much of their success and failure not only to their manipulation of production and markets but also to their individual relationships with domestic politicians.

In particular, British success in the Mexican oil industry was willed by influential Mexicans engaged in a nuanced and delicate political contest. They desired to promote economic development to enhance their internal political control without appearing to be dominated (and thereby discredited) by American business. Politicians surrounding President Porfirio Díaz encouraged all foreign oilmen, but they promoted Sir Weetman Pearson's interests above others. Their political support — in combination with Sir Weetman's business acumen — enabled this British entrepreneur successfully to challenge better-placed American competitors. Nonetheless, the new forces of modernization were beyond the capacity of the Porfirians to control. They may have favored the British, but Americans could not be totally eliminated.

Buy your Lubricating Oils from Us

The Waters-Pierce Oil Company was an American firm with an important mission in Mexico: the development of the domestic oil market. Because of its peculiar niche in the United States petroleum industry, Waters-Pierce came into monopoly control of Mexican petroleum sales during the Porfiriato. Waters-Pierce neither produced nor

refined oil products within the United States; it only sold them. A combination of Waters-Pierce's marketing specialization and its connection to the powerful Standard Oil group worked to develop the necessary sales infrastructure and to widen the growth-induced market for petroleum products. But growth of Mexico's consumption of petroleum products, while enlarging Waters-Pierce's profits, at the same time invited competition. (Profits beget competition, as the old capitalist adage goes.) Once it had developed the market in Mexico, by 1900, Waters-Pierce became vulnerable to competition from producers. Only other foreign businessmen — not Mexicans — had the technical and financial resources to break the marketing monopoly that Waters-Pierce enjoyed in Mexico.

It was not as if no one had known that Mexico possessed petroleum resources. In the Huasteca and Tabasco, pre-Columbian Indians had located a number of pools that oozed sulfurous gases and thick pitch, from which they extracted the substance they used for patching canoes, earthen jars, and baskets. Pitch was also used to cover idols and stucco, to stoke cooking and bonfires, and as a curative salve. In the 1540s Bernardino Sahagún noted that Indian merchants were bringing chapuputli from the Gulf Coast to marketplaces in the highlands. "This chapuputli is odorous," the Franciscan friar reported, "and when it is thrown into the fire, its smell spreads far." Indian women chewed the tar in order to clean the teeth.[4] During three centuries of colonial rule and an additional half-century of troubled independence, both the markets and production of oil in Mexico remained about as limited as these pre-Columbian origins.

Nevertheless, the possibilities of Edwin Drake's 1859 experiment at drilling for crude oil, resulting in history's first oil boom, were not lost upon the Mexicans. The emperor Maximilian gave out a total of thirty-eight oil concessions to Mexicans and Frenchmen in 1865. But nothing happened. After Maximilian fell from power, Ildefonso López had requested the permission of the governor of Tamaulipas to exploit the asphalt bubbling in pools on his Hacienda de San José de las Rusias west of Tampico. He needed a concession from the political authorities, because they had inherited the ownership of subsoil resources — hydrocarbons as well as gold and silver — from the Spanish Crown. What became of López's project is not known. At San Fernando, Tabasco, a priest named Manuel Gil y Sánchez scooped petroleum from what he called a "mine." Apparently thinking of developing an export market, he sent ten barrels of oil to New York. But the Pennsylvania oil

boom begun by Drake's discovery had depressed the price of crude to such a degree that no one there was motivated to buy imported oil. Subsequently, Dr. Silmon Sarlat Nava, the governor of Tabasco, bought the San Fernando property. Changes in the mining laws in the meanwhile had reversed the colonial legal traditions and permitted private ownership of oil. In 1894, Sarlat registered his property with the government, also describing it as a "mine." "In a well of three-meters depth, which I ordered to be dug," Sarlat reported, "the petroleum emerges in a fluid and green state, as that of Pennsylvania in the United States."[5] Considering the enormous obstacles to developing these "excavations," the lack of transportation, the isolation and climate of Tabasco, the lack of either domestic or foreign markets, and the limited production of a three-meter well, it is not surprising that none of these native entrepreneurs brought in an oil field.

The Mexicans were not alone in these early production failures. Several foreigners also failed to initiate the Mexican oil boom during the latter quarter of the nineteenth century. In 1876, a Boston naval captain dug some shallow wells at the Hacienda Cerro Viejo near Tuxpan. The climate, vegetation, poor infrastructure, and lack of capital depressed the seaman, and he committed suicide. Cecil Rhodes, of South Africa fame, then joined in a British consortium, the London Oil Trust, that took over the Cerro Viejo property of the deceased. The Britons attempted to bring inland the most up-to-date drilling equipment. The multiple infrastructural problems were daunting, and Rhodes and his associates, none of whom were experienced oilmen, also gave up.[6] In the meanwhile, exploration was also proceeding farther south near Papantla. A Confederate sympathizer of Irish ancestry, one Dr. Adolfo Autrey, in 1869 took over a prospective oil property and distillery close by the ruins of the sixth-century Totonac city of El Tajín. The oil was described as being "as dense a liquid as cooked linseed oil."[7] Autrey displayed the kerosene produced from his small still at the Exposition of Querétaro in August 1882. By then, he had acquired four haciendas near Tuxpan. Containing large lakes of floating oil, the Hacienda Juan Felipe was described as the "fountainhead" of the petroleum supply in the region. A French engineer visited the oil properties near Tuxpan. He was struck by the incessant bubbling of "hydrogen and naphtha" from these oil springs.[8] Despite the good prospects for production (Juan Felipe later became a booming oil field), ultimately the Boston entrepreneur had to give up the property. His problem was transport. Autrey sent his product out of the rain

forest on mule-back rather than via pipelines. He finally gave up.[9] Other entrepreneurs with greater financial, technological, and marketing resources would eventually open up production on these very same properties — but twenty years later.

As for pioneer oil sales, a Spanish merchant at Tampico, Angel Sáenz Trápaga, had brought some kerosene and gas oil lamps from New York. He was unable to sustain any kind of volume trade in the new product, for which no market as yet had been developed. Later as a broker, Sáenz aided the American marketer Waters-Pierce. The firm had broken off negotiations with the governor of San Luis Potosí, who had requested a personal fee of 100,000 pesos from the company for a permit to build a refinery there. Sáenz helped Waters-Pierce establish the refinery to process imported crude oil at Tampico.[10] This practical Mexican entrepreneur understood that if he himself could not sell oil products directly, he might as well make what profit he could by assisting the Americans.

No doubt, poor waterways, jungle growth, debilitating climate, torrential summer rains, a lack of roads, and a dearth of experienced laborers worked to disable these attempts by Mexicans and foreigners to open up the Mexican petroleum industry. In truth, there was an even greater obstacle. The capital necessary to put in pipelines, hire drilling teams, purchase equipment and barges, and establish refineries was large. To do these things in a rain forest cost significantly more. But no financier, national or foreign, would be willing to place such large amounts of capital into these oil projects until there existed a market for Mexican petroleum products. The logical place to develop a new market was in Mexico itself, since the United States in the late nineteenth century was awash with petroleum. Only foreigners who had prior experience in the oil business were prepared to undertake such an endeavor. For that, Mexico had to await events elsewhere.

Col. Edwin Drake's discovery in 1859 that oil could be drilled for like water revolutionized the industry. Previously, there existed a very small niche in the illuminant markets for oils distilled laboriously from coal and for kerosene distilled from crude oil skimmed — also laboriously — from pools and creeks. No wonder candles and whale oil remained the primary illuminants of the mid-nineteenth century despite the primitive manufacturing methods in candle making and the declining population of leviathans. Technology and capital had played a role in Drake's breakthrough. He had needed capital for equipment and experienced drillers. Some financiers from New Haven, Connecticut, be-

came interested. With new capital, Drake hired a team of experienced water and salt drillers, adopting the existing technology to search for crude petroleum. The Drake well was hardly a gusher. It was only sixty-nine feet deep and flowed at a rate of 25 bd (barrels per day). But it did prove that oil could be produced in commercial quantities by drilling for it.[11] Before too long, petroleum illuminants replaced candles and whale oils, first in U.S. markets, then in markets elsewhere in the world.

Standard Oil had become the most successful business organization in the world within just one generation of Colonel Drake's first oil well in Pennsylvania. Previously associated with a New York mercantile house, John D. Rockefeller in 1865 became a partner in one of Cleveland's oil refineries. By 1870, he had created the Standard Oil Company (Ohio) in order to combine several specialty oil companies into a multi-million-dollar concern. Standard next worked to secure a monopoly of oil transport to the eastern seaboard via rail and pipeline. In 1882, Rockefeller's associates organized the first vertically integrated company. The Standard Oil Trust created a business structure in which each subsidiary company carried out a different, specialized economic function. A leader in export, Standard's East Coast refineries soon handled about 90 percent of U.S. petroleum exports.[12] Standard accomplished its expansion into and domination of oil markets in the American Southwest and in Mexico through an affiliate, the Waters-Pierce Oil Company of St. Louis.

Ironically, Henry Clay Pierce had once been a successful competitor of Standard Oil. The year 1867 found the twenty-two-year-old Pierce in St. Louis distributing oil products for one of the first marketers west of the Mississippi River. He became the oilman's son-in-law and eventually bought out the business. In 1873, Pierce formed a partnership with William H. Waters, who helped him keep the growing Rockefeller interests out of the Southwest.[13] But Pierce needed capital for further expansion and to buy out Waters. His powerful competitors provided it. In 1878, Pierce sold majority interest in his company to Standard in order to get capital for expansion. Together they bought out Waters, Standard taking a 60 percent controlling share of the stock and Pierce the remaining 40 percent.[14] As president of the company, Henry Clay Pierce then became signatory to the famous Standard Oil Trust agreement in 1882. He helped the trust standardize products regularly adulterated by independent jobbers and speculators. Standard's components, the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) and

the Standard Oil Company (New York) handled most of the nation's export of petroleum on the East Coast whereas the Standard Oil Company (California) eventually engaged in exporting from the West Coast. By the 1880s, petroleum ranked as the nation's fourth largest export.[15]

The tie to Standard Oil defined the powers and limits of Waters-Pierce. It only marketed oil products produced and refined by other Standard Oil subsidiaries and affiliates. In turn, Waters-Pierce expanded as Standard's exclusive agent in the states of Texas and Arkansas, Oklahoma and Indian territories, parts of the states of Missouri and Louisiana, and all of the Republic of Mexico. Pierce's company already had sales in these territories, but now its volume sales grew appreciably. Other marketing companies in the Standard group did not operate in Waters-Pierce territory, and it did not operate in theirs. Waters-Pierce did not own a single oil well or refinery in the United States. This relationship to Standard Oil made Waters-Pierce at once a powerful, prosperous, but dependent oil company.

Its experience in Texas bears examination, for Waters-Pierce's vulnerability there presaged its later demise as a monopoly firm in Mexican oil sales. Before the nineteenth century was out, Waters-Pierce had expanded its sales and competed with a tenacity that gained Henry Clay Pierce some enemies among competitors and politicians within his marketing area. In 1889 and 1895, the state of Texas passed antitrust laws requiring licensing of all firms that engaged in interstate business. State statutes outlawed any business combination that fixed prices or restricted competition. At the time, before oil was discovered anywhere in the state, Texas consumers depended upon petroleum goods — mostly kerosene and lubricants — imported in boxes and tins via ship and rail. Pierce controlled 95 percent of this Texas market. His agents charged prices that were 10 to 25 percent higher than those in other marketing areas.[16] Normally, Waters-Pierce extended sixty-day credit to their jobbers on a long line of axle greases, lubricants, and engine oils. "We hope that you will continue to buy your lubricating oils from us," the company would write to Texas merchants. "[We] are willing to make contracts with you for one year at lower prices than you could purchase the same quality of oils for from any of our competitors."[17] The Waters-Pierce agents gave rebates of 15 percent to Texas merchants who signed exclusive contracts with the company.

Merchants in various parts of the Pierce marketing area sometimes broke the exclusive agreement and began to sell the illuminating and lubricating oils of competitors. Waters-Pierce responded by dropping

prices in that locale until the jobbers reconsidered. "Stringent methods were usually followed to keep out competition," reported a long-time Waters-Pierce employee, "and wherever a small concern endeavored to invade the territory occupied by the Pierce interests prices were lowered until the smaller concern was driven out of business."[18] To create the appearance — if not the substance — of competition, Pierce bought out firms like the Eagle Company and the Texas Oil and Gasoline Company of San Antonio and kept them in operation as "apparent" competitors. The state's attorney general remained skeptical. In a popular and widely publicized trial, Waters-Pierce was convicted of acting as a "trust" to fix or manipulate prices and restrain competition. Waters-Pierce in 1898 lost its license to operate in Texas.[19] The Texas case represents the continuing efforts of government bodies in the United States to regulate the volatile competition in the petroleum industry and to prevent the consumers from getting fleeced.

Henry Clay Pierce, however, soon recovered his lucrative market by colluding with Standard Oil to reorganize Waters-Pierce. As he later told a Missouri court, he wanted it to appear that he was managing and controlling the company "absolutely free from the dictation and direction of the Standard Oil Company."[20] In 1900, he took back all Waters-Pierce stock from Standard Oil but secretly returned two-thirds of the shares. The stock strategy — and a timely loan to a Texas congressman — enabled Pierce to apply for a new Texas license. Waters-Pierce thought it was back in business as before.

In any case, the second license had not returned Waters-Pierce to its monopoly position in Texas for long. Discovery of the Spindletop oil field in 1901, ushered in with Anthony J. Lucas's 100,000-bd gusher, abruptly transformed the state's petroleum market. Large new consortiums that combined production, refining, and sales, like the Gulf Company and The Texas Company, came to dwarf Waters-Pierce. The latter, after all, had remained a marketing concern. Just a few acres at Spindletop in 1902 now produced about 20 percent of the nation's petroleum.

Several of the new Texas refineries would have exported to Mexico, if Waters-Pierce had not already had a refinery in place at Tampico. When these first Texas wells began to flow to salt water in 1903, the wildcatters opened up new booms elsewhere in Texas and, by 1907, in Louisiana and Oklahoma as well. By 1902, Texas produced more than 18.5 million barrels of oil, second only to the new boom state of Ohio. As other companies — such as Joseph Cullinan's The Texas Company — expanded refining capacities along the Gulf Coast from 700 bd in 1902 to 200,000 bd in 1905, Waters-Pierce was left out.[21] In the fullness of

time anyway, the company's reorganization had come to seem the fiction it actually was. The state of Texas filed another lawsuit in 1907, resulting in a second revocation of Pierce's license. The continuation of Waters-Pierce's exclusive relationship with Standard Oil had violated the 1903 Texas statute against unfair competition. The Texas courts found that even after the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust in 1892, the Standard Oil Company "controlled, managed and directed" Waters-Pierce.[22] Its connection to Standard Oil that had once made the sales company such a powerful business entity in the American Southwest now, after 1901, relegated Pierce's firm to second-class citizenship within the booming industry. Waters-Pierce would be condemned to repeat the same cycle of power and vulnerability in Mexico.

Shipped Down from New York

It is unclear exactly when Waters-Pierce began exporting, but American petroleum products had found a small market in Mexico relatively early. Soon after the U.S. Civil War, production in the Appalachian field had expanded so rapidly that the classic capitalist syndrome of overproduction and falling prices motivated the petroleum exports. Crude oil's first valuable product, kerosene, rapidly replaced tallow candles and whale oil as the world's foremost illuminant. In addition, the manufacture of kerosene also produced the byproducts of naphtha (gasoline), lubricants, paraffin wax, and tar. The wealthiest of Mexico's consumers were already using imported oil during the empire of Maximilian in the mid-1860s. Their kerosene lamps and cans of illuminating oil arrived on consignment through merchant houses in New York and Mexico City. The Standard Oil Company in the 1870s exported such products worldwide through rather conventional mercantile organizations that traded in a variety of merchandise besides oil. Waters-Pierce also sold through jobbers in Mexico as part of its marketing in the American Southwest. It is certain that Pierce established a permanent and specialized sales force in Mexico soon after Standard Oil purchased the company. In 1887, Waters-Pierce had three salaried agents, a traveling salesman, offices in Mexico City and Monterrey, and a small refining operation in Mexico.[23] Here Pierce managed the market differently from his United States market areas.

Assisted by Standard Oil, Waters-Pierce built and operated oil refineries in Mexico. J.J. Finlay and Company, a subsidiary of Waters-

Pierce named for Pierce's brother-in-law, operated a refining company in Mexico City called La Compañía de Petróleo. Waters-Pierce began construction of a second refinery in January 1887. Each invested approximately $60,000 in their ventures, paying duties on the imported crude oil they processed and claiming to have from the government an "exclusive privilege." Without mentioning his connection to Waters-Pierce, Finlay therefore protested vigorously when a certain Gilberto Crespo y Martínez obtained a concession to import crude petroleum duty free from the Department of Public Works. Despite the fact that the government refused to revoke Crespo's concession, nothing came of this domestic competition. The Tampico plant had a refining capacity of 450 bd; Veracruz, 250 bd; and Mexico City and Monterrey, 100 bd each.[24] Nowhere else did Waters-Pierce also handle the refining end of the business.

In Mexico, the refineries processed crude obtained from Standard Oil — affiliated terminals on the mid-Atlantic coast and, later, the Gulf Coast of Texas. At first, the crude was transported in five-gallon tincans. The tins were then washed out with gasoline and filled with refined kerosene. So ubiquitous had petroleum marketing become in Mexico that visitors traveling over the Sierra de Ajusco south from Mexico City noticed Indian huts roofed with cut-up oil tins bearing Standard Oil brand names.[25] As Pierce explained, "[W]e shipped nearly everything that went into the upkeep of refineries in Mexico from New York, and the tin for the manufacture of cases went from there and iron for tanks, in fact everything that entered into the manufacture of oil down there was shipped from New York."[26] The company's best grade of oil, Eupion, was refined in the Mexican plants, whereas the Eupion that Waters-Pierce sold in the United States originated in refineries controlled by other Standard companies. Its small refining plants processed Pennsylvania crude shipped from Philadelphia. After the Texas oil discoveries, crude was shipped from Corsicana and Beaumont. Pierce transported it to Veracruz and Tampico aboard Waters-Pierce's own bulk steamers. When Standard Oil's California refineries came on line, Waters-Pierce obtained kerosene and other finished products in San Francisco.[27] Mexico's west coast would thence-forward be supplied from California refineries.

Certainly not all of Waters-Pierce's success in Mexico derived from the quality of his three Mexican refineries. Apparently, the distillation they performed on the imported crude oil was quite minor — really a subterfuge to evade the higher import duties on refined products. "The

Company made a practice of bringing in `crude oil' which, as a matter of fact, contained perhaps 90% of the refined product, but was colored by the crude, so as to pay the lower import duty," explained a manager of the Waters-Pierce refinery at Tampico. "The small amount of crude was then refined out, and the whole product sold by the Company at a much less cost than if it had been entirely crude," the manager continued.[28] At the height of its operations in 1902, Waters-Pierce maintained twenty tank-distribution stations and additional sales agencies in Mexico. It owned 104 tank cars and leased another 148 tank cars for transporting oils on the rail lines. In Mexico City, the largest of the marketing areas, Pierce's distribution plant maintained twelve two-horse tank wagons manufactured in St. Louis, ranging in capacity from 160 to 398 gallons each. Pierce sold kerosene-burning heaters in the biggest cities.[29] The company's operations in Mexico had developed unimpeded by competitors since its entry into the country.

Growth of petroleum sales responded to the expansion of the Mexican economy, and the profits of Waters-Pierce expanded accordingly. In order to stimulate Mexico's consumption of imported kerosene, the company sold as many as fifty-five thousand small glass lamps per year — nearly at cost. Its exports to Mexico accounted for 60 percent of all Standard's exports of crude to Latin America and 20 percent of the conglomerate's total crude exports. Saying that he maintained no division of his business between the United States and Mexico, Pierce declared that his total oil sales for 1902 amounted to 2,677,362 barrels. United States trade statistics for the fiscal year ending 30 June 1902 indicate that 287,369 barrels of petroleum products were exported to Mexico. Assuming that all the exports belonged to the monopoly marketer, therefore, Mexico accounted for just ten percent of Pierce's volume sales.[30] (See table 1.) Presumably, the Mexican market provided more than 10 percent of the company's fiscal sales, since his monopoly permitted Pierce to charge higher prices than in its U.S. sales area, where it competed with non-Standard Oil marketing companies. In 1906, Pierce admitted that he had competition of other "tank wagon companies" in its United States territories but not in Mexico.[31]

Certainly, there was no lack of profits. Waters-Pierce Oil Company's capital stock in 1911 was just $400,000, identical to its capitalization when it joined the Standard group in 1878. Still, Pierce paid yearly dividends amounting to 600 percent of its capitalization during the first six years of the twentieth century. One contemporary author placed Waters-Pierce profits at $1.8 million in 1900, $2.0 million each

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

in 1901 and 1902, $2.3 million in 1903, and $2.8 million in 1904. The latter figure represented 672 percent of capitalization.[32] Considering that Henry Clay Pierce was the only other stockholder besides Standard Oil, his personal income must have been considerable.

When he faced a rash of litigation in the first decade of the twentieth century, Pierce claimed that he alone controlled the destinies of the Waters-Pierce Oil Company. Indeed, if one surveys the top management of the company, dominated by family and long-time associates, his claim seems convincing. Pierce, in his mid-fifties, was the chairman of the board. His brother-in-law, Andrew F. Finlay, had been the manager in Mexico and in Galveston before 1890, at which time he became one of the directors of Waters-Pierce. Finlay served as the company's president from 1900 to 1905. Clay Arthur Pierce, the chairman's son, began working for the company in 1898 as assistant treasurer. Serving from 1900 to 1905 on the executive committee, he helped set prices throughout the sales area. Clay Arthur succeeded to the presidency in 1905. The secretary and treasurer of the firm, Charles M. Adams, who had been with the firm since 1878, was responsible for coordinating crude-oil requisitions between Mexican refineries and New York exporters.[33] The management arrangement seems to have given Henry Clay Pierce a measure of autonomy despite the fact that Standard Oil directors were controlling 60 percent of his stock.

In actuality, Standard Oil Company managed the operations of Pierce's company rather closely, a fact that ultimately became a source of some contention. Day-to-day direction of operations from 1900 to 1908 — especially for Mexico — resided in Waters-Pierce's New York representative, Robert H. McNall. McNall was, in fact, an employee of Standard Oil. The address appearing on his Waters-Pierce letterhead, 75 New Street, was actually the rear entrance of Standard's legendary headquarters at 26 Broadway. McNall coordinated Mexican transactions through Standard's export committee, whose offices were also at 26 Broadway. Not even bothering to seek prices and supplies elsewhere, he arranged for the delivery of crude oil to Tampico and Veracruz from Standard affiliates like the Atlantic Refining Company of Philadelphia. McNall also arranged for shipment of Standard California refined oil products from San Francisco to Mexico's west coast ports of Acapulco, Manzanillo, La Paz, San Blas, and Guaymas. He also helped maintain the Waters-Pierce refineries. McNall spent much time ordering pipes, engines, valves, and "a thousand and one articles that are used in a refinery." Refining experts were always nearby for consultation at 26 Broadway.[34]

Standard Oil established a normative and unitizing management over Waters-Pierce, as it did over other affiliates, and coordinated the company's Mexican operations into its all-inclusive information-gathering system. Branch managers routinely dispatched reports from Mexico City to St. Louis, thence to 26 Broadway. Those reports were made on the organization's standard forms, which McNall obtained directly from Standard's refining, transportation, and export departments. He sent the reports to the operating companies. Mexico dispatched forms to fill out to St. Louis on deliveries of naphtha and refined oils, on refinery performance, and on sales. These completed reports eventually returned to McNall. In this manner, Standard Oil even had semiannual statements as to the bad debts charged to the profit-and-loss statement of the Mexican division.[35] Most telling of all, Standard Oil accountants regularly audited the books that Waters-Pierce maintained in St. Louis.

In fact, McNall's authority extended beyond the duties of coordination and information gathering. He and others at 26 Broadway not only evaluated reports of all kinds and audited the Waters-Pierce books but also approved of personnel matters. Concerning Mexico, he once wrote Finlay, the Waters-Pierce president:

I beg to acknowledge receipt of your favor of the 21st. inst., enclosing list showing suggested changes in salaries of Mexico employés. I have been over this matter with Mr. Van Buren [of Standard Oil], and as I telegraphed you today he agrees with your suggestion that these changes be made effective as of January 1st.[36]

Clearly, the Standard Oil Company and its managers retained a large measure of control over the operations of the Waters-Pierce Oil Company both in the United States and in Mexico. The connection accounted for the early success of Waters-Pierce in Mexico — and its ultimate failure.

Although Waters-Pierce dominated the Mexican market as an importing petroleum company roughly from 1880 to 1905, the company did not have to exert its market muscle to subdue either Mexican entrepreneurs or North American competitors. No Mexicans had sufficient expertise or capital. No other U.S. company had business patronage as powerful as that of Standard Oil. Yet competition did finally arrive in 1901, first in the person of a California-based oil prospector, Edward L. Doheny, then in the person of a British engineering contractor, Sir Weetman Pearson. Each had access to technology and capital — and Mexican political support, as we will see below—to discover,

refine, and market domestic petroleum resources. Siege of the Waters-Pierce monopoly in Mexico would ultimately produce a breach between Pierce and his Standard Oil associates.

To meet this new competition in the first decade of the twentieth century, Henry Clay Pierce and Standard Oil initially resorted to price cuts, to flooding the market with competitive products, and to personnel changes in Mexico. Although Mexican petroleum prices were higher than in the United States, Waters-Pierce dominated a market in which consumer prices were actually falling from the moment that the company had begun refining domestically. From 1886 to 1911, petroleum prices declined steadily, and competition provoked more price cutting after 1901.[37] Doheny's oil discovery at El Ebano in 1902 brought domestic supplies of tars and residual products into the market. Because Pierce enjoyed the status of monopoly oilman in Mexico, the figures for U.S. petroleum exports to Mexico in table 1 accurately reflect Waters-Pierce's response. Waters-Pierce increased its imports of residual products from 20 barrels in 1899 to 3,902 barrels in 1902. Likewise, the monopoly importer greatly increased the lighter ends. In order to offset the expected production from Pearson's new refinery on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Waters-Pierce expanded the imports of illuminating oils from 461,266 gallons in 1904 to nearly 1.5 million gallons in 1906. Eventually, the company had to shut down its inefficient Monterrey and Mexico City refineries and expand the Tampico facility to 5,000 bd. Pierce even began to buy and process Mexican crude in limited quantities.[38] These initial tactics, however, proved insufficient to arrest the competition of Doheny and Pearson.

Next, the oil monopoly tried reorganizing its management in Mexico. In 1904, an employee from the Standard Oil comptroller's office, R.P. Tinsley, came to St. Louis to serve as Finlay's vice-president. He also brought a Standard-appointed comptroller. In Mexico, meanwhile, the resignation of Thomas Ryder, a manager there, shook the organization. He took many Waters-Pierce employees with him to work for the competing British Pearson firm. In 1905, Tinsley forced out President Finlay, Pierce's brother-in-law, who departed immediately for Europe "to restore his health." Tinsley himself took over as president and immediately proceeded to make personnel changes, dismissing directors selected by Pierce and replacing many of the managers in the field. Pierce later expressed some bitterness about Standard Oil's meddling in his company's personnel management. The chairman of the board complained that Tinsley sent a Standard Oil general man-

ager to Mexico "who was entirely unfamiliar with Mexico, its customs, people, languages or the business of the company. The effect of that was to cause the very efficient manager of the company to resign his position."[39] Tinsley apparently replaced old Waters-Pierce men in as many as three hundred positions. Pierce protested vigorously. He ultimately succeeded in getting Standard Oil to withdraw Tinsley. Pierce's son, Clay Arthur, became the new president. Yet the company's position in Mexico as well as in the United States continued to erode.

From this point onward, Waters-Pierce and Standard departed in their policies over Mexico. Waters-Pierce, after all, was involving Standard Oil in a number of state antitrust suits that would eventually reach the United States Supreme Court. The Standard officials did not hide their dislike of Pierce. One executive confided that when Henry Clay Pierce got into a jam, he became nasty: "He was the meanest fighter you ever saw."[40] In addition, the sheer weight of the antitrust litigation undertaken by Texas and Missouri began to sap the business initiative of Waters-Pierce. In 1908, a two-year trial in Missouri terminated in Pierce losing his charter to do business in his home state. The Missouri court had found that Waters-Pierce and another Standard affiliate, Republic Oil Company, headed by a young Walter J. Teagle, had colluded to divide the market territory.[41]

Further troubles remained in store for Waters-Pierce in Mexico. It was Texas all over again. By 1908, one of the competitors, Sir Weetman Pearson, had established a refinery and a sales organization in place in order to challenge Pierce for the Mexican marketplace. "Mr. Pierce thought himself so strongly entrenched in the oil business that he `went to sleep' on the job," his Tampico refinery manager reported later. "The competition [with Pearson] for a number of years was of the cut-throat variety, and there was no love lost between the two companies."[42] Nonetheless, a market for specialty oil imports would survive the onslaught of domestic production. Foreign miners continued to buy foreign oil as late as 1908, even though they had to pay import duties. "The reason why we ship these goods from the states," confided a Philadelphia mining capitalist in Etzatlán, Jalisco, "is on account of the very inferior grades that we obtain in Mexico, which will not do our work. . . . [The oils] that are used for machinery purposes cannot be obtained in that country, as the quality that is sold is so inferior that it had almost ruined our machinery."[43] But of course Waters-Pierce wanted to remain more than just the Mexican marketer of specialty imports.

In November of 1908, the increasing strength of Doheny and Pearson brought Clay Arthur Pierce to Mexico City. Mexican newsmen sensed a great struggle in the making. They found Clay Arthur at the Palace hotel. "Of course you cannot expect me to discuss future plans regarding our business in Mexico," the president of Waters-Pierce told the Mexican reporters, "but I can call your attention to the fact that a company, with as much capital invested as that which the Waters-Pierce Oil Company has in Mexico, and with as many years of activity as it has had here, cannot but be prepared to meet whatever situation may come up." Clay Arthur Pierce detailed a litany of services that his company had provided for Mexico over the past three decades. He said that he doubted that another company would be able to organize its marketing in order to give the Mexican public equally as good service as Waters-Pierce. "Where it has been found necessary to cut the price of oil against competitors' initial cuts," Pierce concluded, "the Waters Pierce company has necessarily done so but it has kept up the standard of its products and service. Consumers of our materials get the product of the Pennsylvania fields, which is the very finest oil found anywhere." Pierce refused to respond to reporters' queries about when his company would begin to develop Mexican oil fields.[44]

The younger Pierce's sometimes inopportune comments to the Mexican press illustrate another of Pierce's weaknesses. Like many other American entrepreneurs, he did not consider it to be absolutely essential to be a business diplomat in Mexico. It was enough that the Americans were bringing the fruits of capitalism to this backward country. "The American `generally tries to hog the whole thing' and is often short-sighted in his dealings with the Mexican people," a former Pierce employee observed later. "The English and the Germans, on the other hand, are much more considerate, and in this way gain very considerable business advantages over the American."[45] Such would be the case with Pierce's adversary, Sir Weetman Pearson.

Having lost its market dominance in the southwestern United States, Waters-Pierce was preparing to defend its last lucrative monopoly sales area — not from Mexican entrepreneurs but from other foreigners. The long-time monopoly importer was vulnerable. Initially, Henry Clay Pierce had concluded a contract with Standard Oil that bequeathed him enormous advantages. He had access to as much refined petroleum as he needed, and no other Standard-affiliated firm could enter Pierce's market area. The Mexican market fell into his lap. The profits of Waters-Pierce were very high in Mexico, where it had little com-

petition. But the Standard Oil contract prevented Waters-Pierce from diversifying. It could neither produce nor refine crude oil. The refining capacity of Waters-Pierce depended upon Standard's patronage, which did not extend at all to production in Mexico. Consequently, new sources of production — such as Spindletop, Oklahoma, and Kansas — flooded Waters-Pierce's territory with cheap crude oil out of Standard's control. New refining centers along the Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Texas encouraged the development of powerful and fully integrated competitors. Moreover, growing U.S. legal problems were also poisoning the working relationship between Standard Oil and Waters-Pierce. The American business environment had already humbled Waters-Pierce. Soon thereafter, competition in the Mexican market-place would do the same.

Drilling to the Source

The early history of the petroleum industry, as most capitalist breakthroughs, abounds in willful, driven men. John D. Rockefeller, who consolidated the first oil trust, and Henry Clay Pierce, who dominated Mexico's market, were such men. So was Edward Laurence Doheny. Doheny personified a type of American business entrepreneur who abandoned family and security in search of wealth on the American frontier. His discovery of oil in California seemed to have been accomplished by chance. Doheny built that opportunistic discovery into a worldwide organization that pioneered in the production of Mexican crude oil. He capitalized on the rapid expansion of markets for petroleum and even contributed in the process to developing additional uses of the substance in Mexico. Doheny succeeded in Mexican production because he had superior resources of capital and technology. One might also observe that he entered Mexico in 1901, during a period of intensive domestic economic growth partially attributable to, among other things, Pierce's having promoted the use of petroleum products. No contractual limitations to a superior organization inhibited Doheny's entrepreneurship. If pluck contributed to his California oil success, it played no role in Doheny's far superior achievements in Mexico. He was a willful, wealthy, competent, and now oil-experienced entrepreneur. Almost until the end of his life, Doheny thought himself a man capable of molding destiny.

Doheny's thirty-year journey from his youth in Wisconsin to Mexico resembles the classic Greek odyssey. It combined both caprice and fate. In 1892, after two decades of mine prospecting in New Mexico and Arizona, Doheny and his partner, Charles Canfield, arrived in Los Angeles with scarcely $1,000 between them. Doheny noticed that the local ice plant obtained pitch for fuel from the La Brea tar pits at West Lake Park. As Doheny later explained:

Without ever having seen an oil district or an oil derrick, as I had never been east of Chicago in my life, my natural prospecting instinct told me that these tar exudes bore the same relation to the petroleum below that the resin on the outside of a pine tree bears to the more limpid sap within. I felt sure that by drilling to the source of these exudes I would develop a supply of petroleum.[46]

Doheny and Canfield had begun the Los Angeles oil strike with a seven-barrel-per-day, hand-bailed well that was only 170 feet deep. Within five years, however, experienced well drillers from Pennsylvania moved into the area, opening up some three hundred wells within a 160-acre area. Well riggings stood "as thick as the holes in a pepper box" among residential homes in the West Lake Park suburb of Los Angeles. To compete with rival oilmen attracted to California, Doheny learned the technology and hired drillers from back east. He expanded into the Fullerton, Bakersfield, and Kern River oilfields.[47] The Los Angeles discovery ultimately directed his entrepreneurial talents to Mexico, where some of Doheny's U.S. buyers already had investments.

Perhaps years of prospecting had prepared Doheny to survive the rigors of intense competition in the U.S. petroleum industry. The new oilman refused to depend entirely on selling his production to existing marketing companies like Union Oil and the growing Standard Oil Company of California. Doheny organized the Producers Oil Company and began to build his own marketing apparatus. He approached the Souther Pacific Railroad. Collis P. Huntington's company ran its locomotives on coal and wood obtained in the East and Northwest. The California crude was heavy, especially suitable as fuel oil. It prepared Doheny, in a way, for the even heavier oil he would discover in Mexico. The prospector-turned-oil-businessman set up a demonstration oil-burning steam boiler. He introduced a force-fed jet to a locomotive fuel system that had been burning petroleum in Peru.

He then approached other western railroad men. The Atchinson, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad was always on the lookout to buy oil close to its operations. Coal was more expensive to ship, and created

much waste.[48] Doheny's California properties produced enough petroleum to supply the Santa Fe Railroad with one million barrels of oil per year for use on its ferry steamers and yard engines in California and for sprinkling the railway roadbed through the Mojave Desert to San Francisco. The contract was worth $1 million in sales.[49] Doheny was following destiny.

His California oil business led Edward L. Doheny directly into Mexico. The Santa Fe Railroad's A.A. Robinson, builder and president of the Mexican Central Railroad, informed Doheny that his line running between San Luis Potosí and Tampico had been depending upon imported Alabama coal of "indifferent quality." Moreover, Robinson had just constructed the spur line to Tampico under pressure from the Díaz government; development of a new industry in the territory would provide revenues for his beleaguered line. Therefore, Robinson asked the enterprising Doheny to investigate rumors of bubbling pits along the railroad's right-of-way. Canfield and a California railway man, A.P. McGinnis, accompanied Doheny in May 1900 as he traveled in a private Pullman car, complete with cook and porter. They stopped thirty-five miles west of Tampico. The party descended from the luxurious Pullman, were stunned by the stultifying humidity of Mexico's hot lands, plunged into the lush underbrush behind a Mexican guide, and found some exudes.[50] The chapopotes, as the residents called them, were ponds of brown pitch through which gas bubbled from deep underground. The inhabitants for years had maintained fences around these oil pools to keep the livestock from disappearing into them. Doheny concerned himself, however, with the industrial potential of the exudes.

The American entrepreneur next turned to assembling the necessary capital and technology from his own economy that could be used in the Mexican venture. Returning to Los Angeles, Doheny, now forty-four years old, absorbed himself in establishing a home for his twenty-five-year-old second wife and in organizing a Mexican production company. He collected capital from a group of investors and railway men in California and formed the Mexican Petroleum Company.

Back in Mexico in August 1900, Doheny and Canfield announced that they would pay five pesos to any inhabitants who led them to a tar pit.[51] He acquired his first property along the eastern border of the state of San Luis Potosí. Mariano de Arguínzoniz was offering for sale 283,000 acres of the Hacienda del Tulillo. Arguínzoniz was difficult. Doheny and Canfield were unknown, could not speak Spanish very

well, and were without means of establishing their credibility. "I wired to the City of Mexico, to an attorney whose name had been given to me by a friend of mine in Chicago, and asked him to meet us at Aguascalientes," Doheny explained later. "The attorney we wired was the Hon. Pablo Martínez del Río, since deceased. He was, perhaps, the most prominent English-speaking Mexican attorney in the City of Mexico."[52] Martínez del Río served as Doheny's legal representative in Mexico and introduced him to the heads of various government departments. Because Doheny was establishing a new industry, he obtained certain rights to import machinery duty free for ten years. This was to be an exclusive privilege, but Doheny discovered that a British oilman later received the same rights. Of Pearson, Doheny said that he was "placed on even a better footing than us — getting a 50-year concession — although our efforts to discover petroleum were eminently successful and his efforts, commenced several years afterwards, were based upon our success."[53] As soon as he learned that these Yankees were oilmen, however, Arguínzoniz raised the price from $250,000 to $325,000. Doheny then purchased the Hacienda de Chapacao of 150,000 acres next to Tulillo.

The Chapacao property gave him access to existing rail lines and to the Tamesí and Pánuco rivers leading to the port of Tampico. For his assistance in closing the land deals and serving as Doheny's retainer in Mexico City, attorney Martínez del Río received 600,000 pesos (approximately $300,000). But Doheny insisted that the previous owners sign over the mineral rights, a clause Doheny had included in all his land purchases in the United States.[54] After all, Mexican mining laws since 1884 had copied Anglo-American precedents. Doheny and other foreign oilmen obtained subsoil rights through lease and purchase directly from the Mexican landowners. Foreigners were quite comfortable with this arrangement, because it paralleled the legal practices of private property in the Anglo world.

The Mexican government welcomed Doheny's new petroleum venture, providing encouragement and tax breaks. The U.S. minister to Mexico, Gen. Powell Clayton, introduced Doheny to President Porfirio Díaz. Mexico's chief executive said that domestic petroleum production would save a country already deforested and dependent upon imported fuel. At the time, as Doheny explained later, "I was very busily engaged in denying rumors published in Mexican periodicals to the effect that we were an agent of the Standard Oil Company or a subsidiary of that organization." Díaz, no doubt aware of Pierce's association with Stan-

dard Oil, did not want the infamous oil trust to capture Mexico's petroleum. The president secured Doheny's promise to sell his oil properties to the Mexican government before offering them to Standard Oil. President Díaz was also interested in the demonstration effect of foreign capital. "He told us that his greatest desire for our prosperity in Mexico," said Doheny, "was the example which our workmen would present to the Mexican workmen of how to work, how to live, and how to progress."[55] In the meantime, attorney Martínez del Río assisted Doheny in securing all the lawful tax breaks from the government. Despite the political support he received, Doheny was convinced that none of the Mexicans — Díaz and Martínez del Río included — thought that his oil venture would succeed.

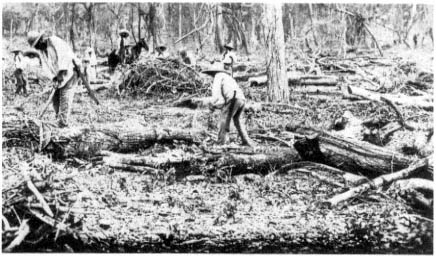

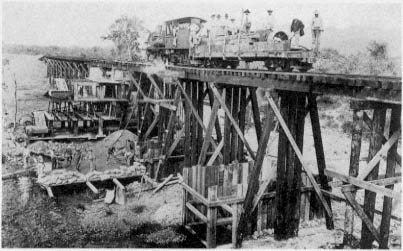

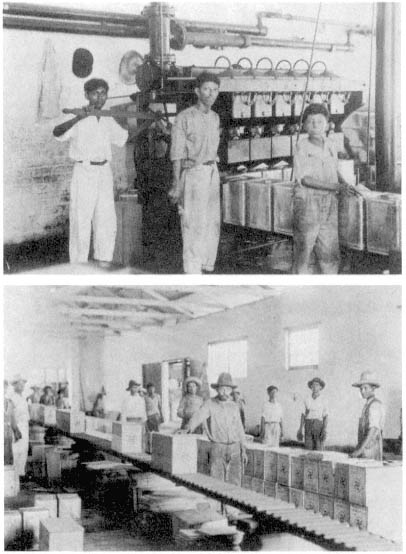

By February 1901, Doheny's men were preparing to open Mexico's first oil field — at El Ebano. Some experienced oilmen from Spindletop in Texas may have come to look over Doheny's properties. Walter Sharp, who along with Howard Hughes, Sr., would later develop the Hughes drill bit, went to Tampico and Matamoros in 1901. "The Standard and Water's Pierce [sic ] Oil Company are fighting the oil business very hard," Sharp wrote, "and it will take every bit of energy and good business plans or they will own it all."[56] Doheny's men established an oil camp at KM 613, a marker denoting the distance in kilometers from Aguascalientes along the right-of-way for the rail and telegraph lines to Tampico. The Mexican Central Railroad constructed a four-hundred-foot siding so that freight cars could unload imported equipment. Herbert G. Wylie came from Los Angeles as the general superintendent at Ebano. He immediately set three thousand Mexicans to clearing the "impenetrable jungle," making roads, building wood-frame houses, and constructing a small refinery. In an incident that portended future problems, Wylie had to fire an American foreman who displayed impatience toward the Mexican laborers. From Pittsburgh, Doheny brought in the equipment for the ice and cold-storage plant, water distillery, electrical plant, sawmill, machine shop, boiler, and blacksmith shop. Boilers were disassembled, hauled into Ebano on boats, then transferred to pack animals and reassembled at the well sites.[57]

North American drillers began the first well in May, and within two weeks the night crew struck oil at a depth of 525 feet. "Oil had come into the hole in such quantity as to lift the tools off the bottom and interrupt drilling," Doheny wrote later. "[The driller] immediately put out the fire under the boiler and shut down, to await daylight and our

inspection."[58] These first shallow wells produced about 10 to 50 bd of heavy, viscous crude oil. Measured at 10 degrees to 12 degrees Baumé, the crude oil of El Ebano was as "thick as cold honey." It served as a heavy fuel oil and asphalt but contained little of the valuable lighter ends such as kerosene. As they began to drill deeper in search of a lighter crude oil having greater rates of flow, Doheny's men used cable tools manufactured in Pennsylvania. Drilling crews first sank an eight-inch pipe into the soil until it struck bedrock. After dropping some two tons of drilling tools into the pipe, they engaged the machinery that raised and dropped the drill bit forty to fifty times per minute. The bit turned on each blow and pulverized the rock. Injected water mixed with the pulverized rock and was pumped out of the well as the drill worked downward. On average, the drilling teams could bore about one hundred feet per day into the earth.[59] Exploration proceeded slowly, and the oil proved disappointingly heavy.

Doheny's subsequent explanations of the El Ebano oil strike under-estimated the technological obstacles of the Mexican strike. Doheny tended to exaggerate his own entrepreneurial role, great as it already was. To a financial writer years later, and in his appearances at congressional hearings, Doheny depreciated the value of trained geologists. "Geology profs don't find oil," he used to say.[60] Nevertheless, he was a smart enough businessman to make use of available knowledge. Doheny hired Mexican geologist Ezequiel Ordóñez, who had written an optimistic report on Mexico's oil prospects for the Mexican Geology Institute. His report had become so controversial that Ordóñez was forced to resign from that organization when he encountered the wrath of the powerful finance minister, José Yves Limantour. The Mexican geologist found the American entrepreneur optimistic, domineering, unable to accept being contradicted, and strangely lacking in original ideas. Ordóñez located Doheny's prolific well at the base of Cerro de la Pez (Pitch Hill) at El Ebano. Pez No. 1 came in on 3 April 1904, flowing at a rate of 1,500 bd. Several years later, a Stanford University geologist would remark that all the successful Ebano wells had been put down practically on the seepages. Other geologists and engineers also served Doheny by mapping all the oil exudes on the El Ebano properties.[61] For the moment, the larger well that Ordóñez brought in permitted the pioneer oil producer to continue his operations.

Establishing a commercial oil producing venture in the wilderness at El Ebano proved a daunting task. Armed with capital, technological experience, a reasonably developed infrastructure, and access to growing

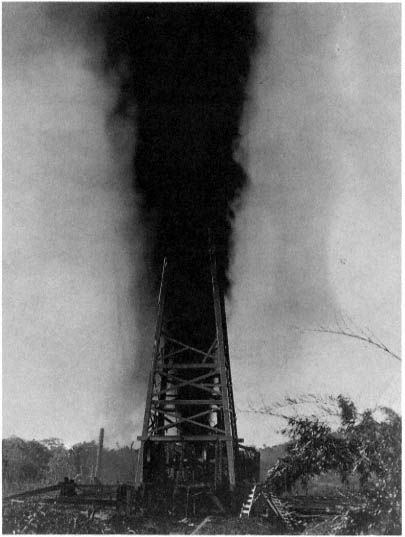

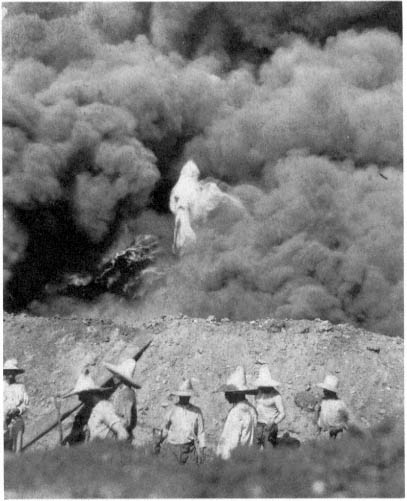

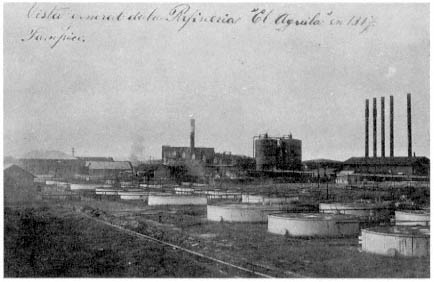

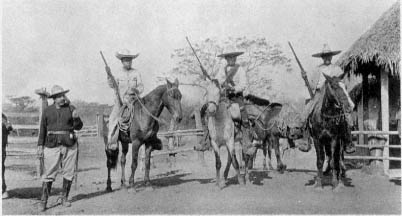

Fig. 1.

An El Ebano well blows in, c. 1904. One of the first oil wells in Mexico,

this El Ebano gusher blows out gas and thick crude petroleum shortly

after being drilled in. the workmen next disassemble the remainder of the

wooden derrick, remove the equipment, and place a valve over the

well casing. from the Estelle Doheny Collection, courtesy of the Archive

of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, Mission Hills, California.

domestic and foreign markets, Doheny was the first oilman equal to the challenge. First, the land was cleared. "A narrow gauge railroad had to be built," the superintendent, Herbert Wylie, reported, "and the whole region opened up before oil could be produced."[62] Moreover, a pipeline for the heavy oil was undesirable. "The continued heating of the oil, especially to a temperature that would enable us to pump it through a long pipe line, would render this oil unfit for fuel," Wylie observed. A railroad spur was absolutely necessary to get the oil out. The porous adobe soil prevented wagon traffic during the rainy season.[63] Then the managers needed to secure an adequate supply of water for drilling operations and for the workers. A neighboring hacendado would charge $500 for allowing the company to run a water line across his land from the Pánuco River. Besides, the Pánuco water had an unpleasant odor. Wylie favored water pumped from the Tamesí River.

The Mexican Petroleum Company had a difficult time selling Doheny's heavy petroleum. Wylie approached foreign railway men, but many as yet had no way of transporting the fuel. Worst of all, the Mexican Central Railroad reneged on its promise and refused to purchase the thick stuff from Doheny. Just nine months before its first strike, the management of the Mexican Oil Company had concluded a sales contract with the Mexican Central. The oilmen were to convert the Central's locomotives at their own expense and keep those locomotives supplied with fuel at set prices of 90 cents to $1.20 per barrel. Financially strapped in 1902, the old board, dominated by Doheny's associate Robinson, sold out to new investors led by rival oilman Henry Clay Pierce. Apparently, Pierce used his influence to cancel the oil purchases.[64] The Doheny interests were disheartened.