Preferred Citation: Janzen, John M. Ngoma: Discourses of Healing in Central and Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3779n8vf/

| NgomaDiscourses of Healing in Central and Southern AfricaJohn M. JanzenUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1992 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Janzen, John M. Ngoma: Discourses of Healing in Central and Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3779n8vf/

Preface

Discourse is central to the construction of knowledge about misfortune and healing. In Central and Southern Africa, discourses of healing take a number of forms: the evocation of distress and hope before others; prayers to God, ancestors, and spirits; songs both out of the cultural stock at hand as well as original compositions from the wellsprings of individual emotion; highly codified dress; instrumental accompaniment and dance; the creation and use of materia medica. All come together in the "doing of ngoma" that is the subject of this book. Discourse is the descriptive term of choice for this action "doing" because at issue is the mutual expression of feelings and ideas and the marshaling of knowledge and social networks required to bring about an acceptable solution to the range of ills addressed by ngoma-type movements and institutions.

The subject has been much examined in Central and Southern Africa by many authors under rubrics as diverse as divination, healing, health care, religion, epidemics, magic, ritual, cult activity, dance, song, folklore, and more. This book explores for the first time the possibility that some of this activity may in fact be a unique historical institution. Such a proposition is suggested above all by the presence, over a vast region, of similar words, names, procedures, and types of behaviors—discourses, in short—around the interpretation of misfortune and the treatment of affliction. For some time the use of language history has been a tantalizing vehicle for the study of the history of cultural do-

mains. Where the compilation of lexica and grammars has progressed far enough, it is possible to single out for special study terms and structures in language around particular domains. In the present survey work this analysis is applied in a relatively simple manner to some cognate terms of health and healing that are widely used in ngoma. The rigorous analysis needed awaits further collection of detailed local vocabularies and the identification of practices; this has not been done very widely.

However, as this book goes to press, the horizon of new research that will supersede it is already apparent. Great strides have been made with the use of linguistic history as applied to the history of selected cultural domains. The paragon of such work is J. Vansina's recent Paths in the Rainforest (1990), on the evolution of political institutions in the rainforests of Western Equatorial Africa.

New research on ngoma is already in progress, including fieldwork of ngoma in Tanzania, the documentation of revivalist ngoma in the aftermath of the civil war in Zimbabwe, and the mapping of the institution in terms of layers of historical language formation. The result of this work will take its place within a growing body of self-conscious literature on the subject. The present project is the first comprehensive study of the discourse on misfortune and healing in Central and Southern Africa in connection with the institution Ngoma.

I must acknowledge many and varied individuals and agencies who made possible, and facilitated, this project. The University of Kansas sabbatical fund permitted me to take a leave from teaching for research travel in Africa. A senior research fellowship from the CIES-Fulbright Program made it possible for me to travel to the four cities that the research plan suggested would be opportune. The University of Cape Town invited me to its distinguished professor series, which opened doors and made contacts possible that I otherwise would not have been permitted.

Research in Zaire, Tanzania, and Swaziland was greatly facilitated by CIES sponsorship. In Kinshasa, this included such necessary privileges as being picked up from and taken to the Njili International Airport and being helped in a variety of other ways by the people of the Cultural Affairs Office at the U.S. Embassy, Acting Officer Phyllis Oakley and Nsumbu Ndongabi Masamba. Nsiala Miaka Makengo of the National Research Office, and Mabiala Mandela of the Centre de Médecine des Guérisseurs granted me much hospitality, time, and attention, as did Father Joseph Cornet and Lema Guete of the National

Museum of Zaire. I am also indebted to Kamanda Sa Cingumba and Nzimbi Nsadisi for their friendship and assistance.

In Tanzania, Emmanuel Mshiu and Dr. I. A. J. Semali of the Traditional Medicine Research Unit at Muhimbili Hospital were my formal sponsors. The National Research Council authorized the project, for which I am grateful. E. K. Makala, of the Music Division of the Ministry of Culture, and his colleague Yesia Luther King assisted greatly in making a number of contacts and by sharing their understanding of the research topic. Professor Ernest Wamba and Fidelis Mtatifikolo of the University of Dar es Salaam were friends to me while I was in Dar.

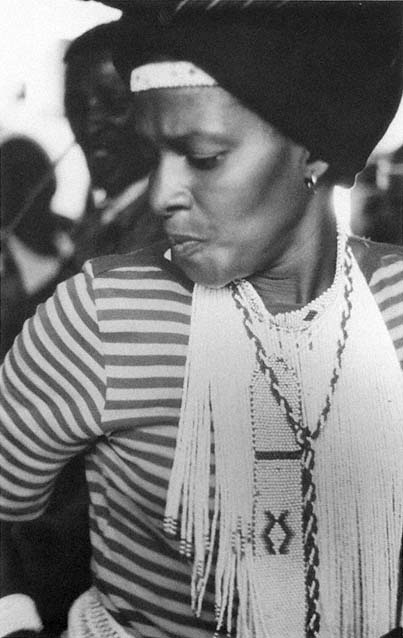

In Swaziland I had an excellent introduction and accompaniment to my stay from Ted Green, who was at the time working with the Ministry of Health and collaborating with Lydia Makhubu of the university in research on indigenous health-care resources, including tangoma (plural for sangoma : "healer"). Harriet Ngubane, a South African anthropologist who has worked with Zulu diviner-healers in Natal, introduced me in a marvelous way to many individuals in Mbabane and provided extensive interpretative help for my research. I am deeply indebted to these two friends.

For my survey research on ngoma in the Western Cape I am indebted to many people, including Professor Martin West, head of the Department of Social Anthropology of the University of Cape Town, and the members of the university administration who helped me during my time in Cape Town as a visiting distinguished professor; Janet Mills, whose acquaintances with numerous amagqira helped me to make quick contact; Adelheid Ndika, igqira (igqira is "healer"; amagqira , "healers" in Xhosa), who graciously invited me to the nthlombe (feast) sessions of her cell, encouraged me to photograph and record the events, and explained what was occurring.

Following a policy begun in earlier writing, I have used the names of healers and other public figures associated with the rituals and subjects of this work, insofar as they granted permission for this. However, although the therapy sessions described are often open to the public, and in that sense very different from the confidential character of Western healing, I have used pseudonyms for the sufferer-novices of the ngoma therapies. Because they were sick or deeply troubled at the time of my encounter with them, they were often not in a condition to consider the question of permission.

Parts of this work, or perspectives forwarded in it, have had the benefit of reaction from a variety of scholarly publics. The section

"Lexicon of a Classical Sub-Saharan Therapeutics" in chapter 2 was first put forward in a paper prepared for the Hamburg, Germany, conference on "Ethnomedicine and Medical History," May, 1980, organized by Joachim Sterly and Hans Morgenthaeler, and subsequently published as "Towards a Historical Perspective on African Medicine and Health" in Ethnomedizin und Medizingeschichte (1983). The present interpretation of the Bantu lexical data benefits from an additional decade of important new analysis. The perspectives presented in the section of chapter 2 called "Social and Political Variables of a Complex Institution" were presented in two papers. The mandate to sharpen the ontological identification of ngoma came from Stan Yoder's discussion of my paper "Cults of Affliction: Real Phenomenon or Scholarly Chimera?" in Tom Blakeley's conference on African Religion at Brigham Young University, October 23, 1986. Another perspective in that section was aired in a paper entitled "How Lemba Worked, or, the Trickster's Transformation" at the African Studies Association, New Orleans, November, 1985. Ideas from this paper also appear in chapter 5, "How Ngoma Works: Of Codes and Consciousness." Some of the material in chapter 4, "Doing Ngoma: The Texture of Personal Transformation" was first given on February 9, 1987, before the Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago, in a Monday colloquium entitled "Words, Beats, Tunes: The Fabric of Personal Transformation in Ngoma Ritual Therapy." The relationship between kin, or lineage-based, and extra-kin strategies of health seeking were explored in a presentation to the Health Transitions conference organized by the Rockefeller Foundation and the Health Transitions Centre at Australian National University in May, 1989.

The nucleus for the book was set forth in a set of unpublished papers called "Indicators and Concepts of Health in Anthropology: The Case for a 'Social Reproduction' Analysis of Health" and "On the Comparative Study of Medical Systems: Ngoma, a Collective Therapy Mode in Central and Southern Africa." These were circulated in various ways as "Two Papers on Medical Anthropology." Chapter 6 grew out of the first of these papers, and further collaborative writing and thinking on the subject of the basis of health with Steven Feierman in preparation for an edited volume, The Social Basis of Health and Healing in Africa . The reader will find echoes of the perspective put forth here in several published articles, including: "Changing Concepts of African Therapeutics: An Historical Perspective," in African Healing Strategies , edited by Brian M. du Toit and Ismail H. Abdalla, 1985; "Cults of Af-

fliction in African Religion," The Encyclopedia of Religion , edited by Mircea Eliade, 1986; "Health, Religion and Medicine in Central and Southern African Traditions," in Caring and Curing: Health and Medicine in World Religious Traditions , edited by Larry Sullivan, 1989; "Strategies of Health-Seeking and Structures of Social Support in Central and Southern Africa," in What We Know about Health Transition: The Cultural, Social and Behavioural Determinants of Health , edited by John C. Caldwell, et al., 1990.

I remain indebted to numerous others who have listened to my arguments or pointed out important issues as this work has progressed. Special thanks go to Nels Johnson, who reminded me of Mary Douglas's use of Bernstein's analysis as it appears in chapter 3; Thembinkosi Dyeyi of East London, South Africa, who interpreted the intricacies of the "doing ngoma" session presented in chapter 4 and translated its text into English; Stan Yoder, Richard Werbner, Terence Ranger, Henny Blokland, and several other anonymous readers who offered constructive criticisms; Sue Schuessler, who discussed ngoma in many conversations, and whose own work on this subject has helped me understand some of the issues in the literature; Gesine Janzen, who drew the maps and figures; and Linda Benefield, who copyedited the manuscript.

Finally, I am, as always, indebted to Reinhild for her critical encouragement of my research and writing, and to Bernd, Gesine, and Marike for their enduring interest in their father's seemingly endless project on African health and healing.

Introduction

That which was a stitch of pain,

has become the path to the priesthood.

Lemba song text,

Kongo society, 1910

An important feature of Sub-Saharan African religion and healing, historically and in the twentieth century, has been the interpretation of adversity, paradox, and change within the framework of specialized communities, cells, and networks. In Central Africa these communities have come to be called rituals or cults of affliction, defined by Victor Turner, a major author on the subject, as "the interpretation of misfortune in terms of domination by a specific non-human agent and the attempt to come to terms with the misfortune by having the afflicted individual, under the guidance of a 'doctor' of that mode, join the cult association venerating that specific agent" (Turner 1968:15–16). In some circles these communities are called "drums of affliction," reflecting the significance of their use of drumming and rhythmic song-dancing, and the colloquial designation in many societies of the region of the whole gamut of expressive dimensions by the term ngoma (drum). The drumming is considered to be the voice or influence of the ancestral shades or other spirits that visit the sufferer and offer the treatment.

This work is concerned with institutions carrying the designation ngoma and related terms. By entering African religious and therapeutic expression through its own language, we are identifying some important underlying, and possibly historic, commonalities and connections. We can also establish the basis for variants and transformations more intelligibly.

A number of modern scholars have looked at this institution in Cen-

tral and Southern Africa, although not always through the indigenously labeled categories. For example, Hans Cory, in the thirties, studied the constellation of ngoma groups among the Sukuma in colonial western Tanganyika and on the Islamized coast. His work for the British colonial government was concerned with the potential of these groups for social unrest. This work today provides a useful cross section of ethnographic and historic interest at one moment in time (Cory 1936).

The reference point of scholarship on African rituals or "drums of affliction" continues to be Victor Turner's work among the Ndembu of northern Zambia in the fifties; he introduced the term as a translation for the indigenous word and concept ngoma (Turner 1968, 1975). Turner's in-depth studies on several of the twenty-three Ndembu cults of affliction showed their inner workings and social contexts, intricate ritual symbolisms, therapeutic motivations, and societal support systems. At the same time, although he put forth the Ndembu as universal persons with believable aches, pains, and expressions, we now see that his account of them was largely ahistorical, localized in its coverage to the villages in which he did fieldwork, and presented in a largely static analysis characteristic of the prevailing structural-functionalist paradigm of the time. It was not clear in his work how widespread this genre of institution might be, nor whether it was particular to the Ndembu of Zambia on the Southern Savanna.

A variety of authors, researching and writing about the central and southern regions of the continent, described similar features in connection with the verbal cognate ngoma , but they usually did not make the connection between their own work and that of other scholars in other regions. In the era of structural-functionalism and colonial domination, the local "tribe" was the unit of study. Rarely were comparisons, or concerns for historical directions, articulated. However, useful work was accumulating which would make the task of historical comparison possible later on.

J. Clyde Mitchell (1956), a colleague of Turner's, followed the Beni-Ngoma movement into the migrant labor camps of the copperbelt. Terence Ranger found, in coastal and historic trade-route Tanzania, that the revivalist and dance dimensions of ngoma had followed the trade routes and population movements between early colonial settlements (Ranger 1975). Maria Lisa Swantz (1970, 1976, 1977a , 1977b , 1979) and Lloyd Swantz (1974) studied ngoma and related ritual heating on the Swahili coast in connection with social change and development. Wim. Van Binsbergen, Gwyn Prins, and Anita Spring

studied ngoma in Zambia. Spring's work added comparative ethnographic data from the "ngoma mode" of healing among Luvale women (1978, 1985). Prins and Van Binsbergen contributed to the history of western Zambian ngoma, the first to the cognitive framework of ngomalike therapeutic ritual (Prins 1979), the second to the linkage between numerous cults in the history of a region as an expression of differing modes of production and forces of historical change (Van Binsbergen 1977, 1981). Monica Wilson (1936), Harriet Ngubane (1981), and others studied the therapeutic ngoma settings in Southern Africa, where it was perceived as having largely to do with divination (especially among the Nguni-speaking societies).

Despite the value of these authors' writings on the subject of the cult of affliction, none has looked at the larger picture. They do not tell us how far-reaching the institution, as a culturally particular institution, might be. Luc de Heusch and Jan Vansina have been among the few to attempt broader surveys of possession cults in Central and Southern Africa. DeCraemer, with Vansina and Fox (1976), offered a summary profile of Central African religious movements, which they suggested were part of a cultural expression reaching back a millennium or more. But this article, suggestive in its general lines, did not provide a lexical or structural handle on how to study it further. De Heusch (1971) established a structuralist comparison of types of possession cults and relationships throughout the West African and Central African region that had far-reaching ramifications in such scholarship of the area. He emphasized, for example, the important contrast between possession cults, which entailed healing and exorcism, and cults that venerated shades and spirits, on the one hand, and cults that utilized mediumship for the interpretation of misfortune, on the other.

Ian Lewis, with a scholarly focus in the Horn of Africa, has offered important hypotheses on the nature of African cults and religions, first with his "peripheralization" or "deprivation" approach (1977), more recently with emphasis on the extent of "controlled" and "uncontrolled" power in society, and the relationship of witchcraft patterns to patterns of possession (1986). Most recently, DeMaret (1980, 1984) has used archaeological and linguistic findings to attempt an overview of Central and Southern African religious and social features. I will have occasion to come back to these authors and their work.

This brief review of some of the scholarship relating to healing in community settings in Central and Southern Africa suffices to demonstrate that the field is not well defined, nor is it clear where one begins.

Current scholarship tends to break down into a distinction between religion and healing, but this distinction is not so useful in the present setting. A fundamental ambiguity that will need to be worked out in this study is that between the indigenous categories and terms, on the one hand, and the analytical models we devise for such an institution as the rite, cult, or drum of affliction, on the other hand. The term ngoma has been identified as the indigenous word for an institution. And yet, in many regions it is not necessarily used, nor exclusively used, to describe collective rites of healing. In the course of this study, therefore, the layered ontology of the "unit of study" will need to be clarified and variations around themes explained. This will be done ethnographically or contextually, culture historically, ethnologically, and analytically, in sequential chapters.

My own concern for the understanding of the shape and character of African therapeutics began, like that of other scholars, with very local work—in Kongo society of coastal Zaire (1969, 1978a , 1978b )—and has gradually moved to increasingly expansive coverage of institutional arrangements (1979b ), therapeutic dynamics (1986, 1987), and historical processes (1983, 1985). Following intensive fieldwork in Kongo society on the "quest for therapy" and the structure of local institutions, I looked at a major historic cult, Lemba, which had emerged in the context of the coastal trade in the seventeenth century, and which had mediated the disintegrative mercantile forces of the overland caravan routes in that trade with the local lineage-based communities (1982). It became clear that local descriptions and explanations made little sense of the continuities and variations in Lemba. One had to take both the regional view of the cult phenomenon and a long-term historical perspective of the economic, political, and social climate to understand its emergence and duration.

After extensive reading in connection with my own local fieldwork and after historical study, it has become apparent that the cult of affliction and the ngoma designation of it is widespread throughout Central and Southern Africa, although there are many institutional and terminological variations. The scholarly task of the present moment, therefore, is to situate this work in wider regional, societal, and subcontinental context, and in the process to ask how widespread this institution might be, whether its many manifestations are transformations of an underlying common institution, why particular forms of it rise and decline, and how it relates in a dynamic relationship to other features of society and religion. A major lacuna in studying the wider phenome-

non of the cult or drum of affliction across its appearance in Central and Southern Africa has been the absence of a set of comparable studies. Scholars have either done local ethnographic studies with careful attention to the structure of customs and languages and have done little to seek broader generalizations, or they have attempted broader generalizations without careful attention to the cultural particulars.

In 1982–83 I undertook to remedy this situation for myself with an extensive field survey of ngoma manifestations in four settings of Sub-Saharan Africa where the literature suggested it occurred. I was especially interested in how ngoma impulses and organizations were represented in major urban settings. The sites I visited in this work were Kinshasa, a hub of Western Bantu societies, including Kongo, in the Zairian national capital; Dar es Salaam, where Eastern Bantu and national Tanzanian cultures come together, with a strong Islamic presence; the Mbabane-Manzini corridor in Swaziland, at the northern end of Nguni-speaking societies, in a strong traditional kingdom; and Cape Town, in whose black townships all Southern African traditions merge in the underside of a society torn by apartheid.

Why were urban settings selected, which tended to feature immigrants to cities and transplanted practitioners from home areas in the countryside? First, the urban capitals studied offered much more accessibility to regional traditions than single rural areas. Indeed, one could find all regional traditions represented in these cities. Further, it was easy to identify ongoing local scholarship on these traditions and to converse with scholars and practitioners about the unfolding direction of the therapies. Ongoing practice in the urban setting would demonstrate continuing life, although changing, of the institution. Finally, it was virtually impossible for me to do justice to the subcontinental survey short of visiting a selective set of points on the map, such as Kinshasa, Dar es Salaam, Mbabane-Manzini, and Cape Town. Of course, other capitals could have served equally well, including Harare in Zimbabwe or Lusaka in Zambia.

The comparative survey emphasized eight points regarding the therapeutic dimension of cults of affliction: (1) the names of principle rites, their regions of origin, and terminologies; (2) modes of affliction (following Turner: symptomatological signs) and etiologies (spirits, social forces); (3) the characteristic therapy of a rite; (4) the social scale of the affliction (whether individual, group, or combination); (5) the socio-cultural context—class and status, ethnic group, gender—of the afflicted and of the healer; (6) characteristic devices and musical instru-

ments, dances, and songs of the rites; (7) profile of individual(s) in charge of the therapeutic rite—family, diviner, other specialists, association members; (8) perceptible changes in the last decade. These queries provided the underlying thrust of the investigation and were answered in each of the four regions, insofar as possible.

Although this work will address a particular type of institution in concrete historical settings and is in many ways simply a straightforward attempt to understand and to portray this institution, the framework of the inquiry is intended to be universally applicable. In other words, there is a theoretical subagenda to this work, for which ngoma is the case study. I present this agenda in the form of three issues—health, healing, and efficacy. They must be approached, theoretically, in this order. This order may seem reversed to some; however, it stems from a growing concern in medical anthropology that this field is not effectively applied to health issues (Harwood 1987:4). I contend this is the case because of a lack of concern for the ways in which healing, or medicine, affects health, that is, the subject of efficacy, or how the therapy "works."

Increasingly, in social science and medical writing, definitions of health provide the point of departure for the analysis and action of specific interventions. This gets us squarely into the debate on conceptions of health, which authors approach from a variety of viewpoints. Most of the time we use the negative "absence of disease" definition of health, or the demographer's profile of mortality, natality, and morbidity. However, definitions of health may also be philosophical (e.g., Boorse 1977), ecological (Dubos 1968), political economic (Doyal 1979; Savage 1979; Morsy 1981), sociological normativist (Parsons 1951; Freidson 1971; Zola 1966), or ritualistic, discursive, and interpretative. Exploration of definitions of health suitable for the analysis of African ngoma therapy will be addressed in some length in the final chapters of this work.

The application of a concept of "social reproduction" seems particularly suitable here. Given the widespread network relationship building that goes on in ngoma, "health" may be seen as a society or social unit's ability to regenerate itself (i.e., socially reproduce). This approach is inspired by the work in Southern Africa of Colin Murray on labor migration in Lesotho and the outflow of labor capital, resulting in a crisis of social reproduction (1979, 1981). Other authors who have developed a social reproduction analysis include Pierre Bourdieu (1977). This approach overcomes the chronic problem in classical medical anthropol-

ogy and other disciplines of not being able to completely explain the deterioration of health in a society or a sector of society and the way in which members of society cope with this situation. The perspective of health as social reproduction will set the stage for an analysis of the collective therapies of Central and Southern Africa.

Establishing the character of the conscious therapeutic intervention as the basis for the comparative study of medical systems and traditions is the second major theoretical issue in this work. What will be the framework with which to analyze, in common terms, varied phenomena? What are the criteria of the "common," the "comparable"? Are they that which is labeled in indigenous practice and parlance? Or do they have to do with behaviors? In the case of Central and Southern Africa, do the common cognates of Bantu languages play a major role in determining what is the core of the historic and contemporary therapeutic system? Then there are the "institutional" questions, having to do with the primacy of the individual versus the collective, or societal. Central and Southern African therapies such as ngoma are so different, and differ in so many ways, from Western therapy, that we must first ask how the boundaries of researchable reality are to be drawn to identify this as medicine, or as healing, in order for it to have anything in common with the institutions the Western industrial world identifies by these terms.

Criteria of efficacy in therapy will need to be formulated, both in terms of specific therapies and interventions found in ngoma and in terms of the more general question of whether, and how, they may contribute to health. Both individual (psychological, symbolic, pharmacological, musical) as well as social mechanisms (entering and extending a network, creating support groups and redistributive chains, social competence) need to be studied as therapeutic mechanisms that may have generalizable qualities. Many of these measures enhance the ability of individuals and societies to contain trauma and to deal appropriately with difficulties, thereby contributing to social reproduction in the marginalized, alienated, or stressed sectors of a society, which ngoma therapeutics appears to address.

In order to accomplish the basic ethnographic-historical task of presenting ngoma and to open the theoretical discussions raised above, this book has the following structure. Chapter 1, "Settings and Samples," is a straightforward comparative study of four regional settings: Western Bantu, as found in Kinshasa, Zaire; eastern Africa, as found in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; southern Africa, focusing on Mbabane in Swazi-

land, which is one of the North Nguni-speaking societies; and the townships of Cape Town, South Africa, predominately Xhosa, or South Nguni, but also a cosmopolitan synthesis of all of Southern Africa. This survey is largely a presentation of my field research of 1982–83, and thus it has all the strengths and weaknesses of a single scholar's work: limiting, in that it is only one individual traveling vast distances; enhancing, in that a trained eye can see much and make connections that a casual observer misses. In the western setting (Kinshasa, Zaire) I concentrate on the particular cults of affliction called Lemba and Nkita, of Lower Congo origin; Zebola, of the Equator origin; and Bilumbu, of Luba, or Kasai origin. Most of these are couched within the lineage setting or are designed to buttress the lineage. In East Africa (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania), because of the early work of Hans Cory on historic Sukuma ritual organizations, it is possible to offer a profile of both western Tanzanian ngoma and coastal Swahili, Islamized society, and ngoma expressions. From Southern Africa (Mbabane, Swaziland, and Cape Town, South Africa) come some of my best full accounts of ngoma, partly because of fieldwork luck and also because the institution may be less specialized there and may represent a more generic manifestation.

Chapter 2, "Identifying Ngoma: Historical and Comparative Perspectives," raises the possibility that ngoma is indeed a classical manifestation of Central and Southern African ritual. This chapter situates the book's subject in the context of research on the origins and dispersions of Bantu languages and cultures and the distributions of cognate lexica for ngoma and other African therapeutic-religious institutions. What is the evidence for culturally homogeneous domains beyond the linguistic tags? How do we account for the immense variations around the linguistic commonalities in this vast subcontinental region?

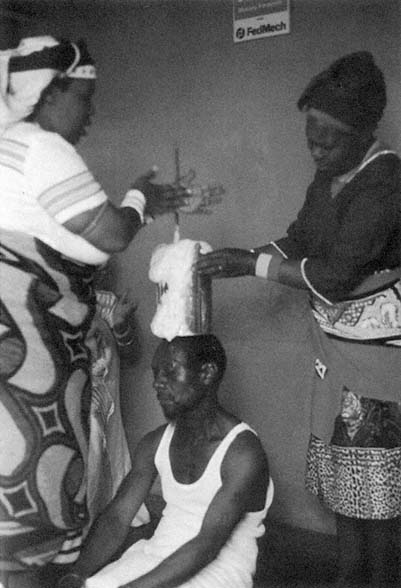

Chapter 3, "Core Features in Ngoma Therapy," develops a description of the main characteristics in ngoma therapy underlying the myriad manifestations of the institution throughout the region. These features include a phased rite of passage in which the sufferer, following identification of a sponsoring healer, moves gradually through the therapeutic initiation to membership in the order; a similar pattern of defining and interpreting misfortune through the invocation of, and possession by, ancestor shades, nature spirits, and other spirits; a common symbolism defining the status of the sufferer-novice moving through "the white," the ritual status of being "in process"; the role of sacrifice and exchange; and the empowerment of the novice through the transformation of the self and the composition and use of medicinal substances.

Perhaps the most important core feature, however, is the subject to which the next chapter is devoted.

Chapter 4, "Doing Ngoma: The Texture of Personal Transformation," moves beyond the behavioral and symbolic features of therapeutic initiation to the conscious, verbal dimension found in the ngoma sessions. A single session is described and analyzed in depth. It provides the basis for a wider comparison with other examples. The centrality of song to ngoma becomes apparent here. The variations in communicative structure of ngoma provide important clues to the understanding of the institution.

Chapter 5, "How Ngoma Works: Of Codes and Consciousness," proceeds with a presentation of the indigenous theory of this form of healing. From there it moves to the application of several academic analytic evaluations of ngoma, including the role of metaphor shaping, of consensus, and of the range of manipulations that shape affect of sufferer and therapists alike.

Chapter 6, "The Social Reproduction of Health," looks at ngoma from the standpoint of its contribution to society's fabric, attempting to answer the question of ngoma's contribution to health as understood in today's world. This chapter, of necessity, opens with a discussion of various health definitions, to determine which set might be appropriate for an understanding of ngoma's contribution to health in a contemporary context.

A project such as this is at once audacious and precarious. It is an attempt to demonstrate something that has not heretofore been known, essentially a mapping out of the core feature of a classic civilizational healing system in Central and Southern Africa, or at least a major feature of it. It is precarious because the assumptions that must be made in attempting this are not well validated. Working with linguistic reconstructions and variations around core behaviors often leads to interpretations of local evidence collected by others. One scholar, looking "over the shoulders" of others, is bound to be wrong some of the time in others' ethnographic backyards. To make matters more complicated, my ethnographic "home territory," Lower Zaire, in the Western Bantuspeaking region, fits the generalizations on ngoma least well, in some respects.

However, it will have been worth the risk if the end result, if only through criticism, provides the stimulation of new ideas and better research, especially that which goes beyond the confines of tribe and territory in Africa.

1

Settings and Samples in African Cults of Affliction

Do you intend to spend your sabbatical in airport waiting rooms?

A skeptical colleague

Lagos airport, awaiting night flight to Kinshasa: It's 34 hours since I've slept. I wonder if there are any kola nuts to be had. How would one find a kola nut in Lagos airport? Is this still Nigeria, or Africa? In the souvenir sales area I approach a group of gathered men and tell them I've been traveling a long time and need to stay awake—any kola? Several reach into their robes and pull out kola nuts. One shares with me, biting off the end of a nut and handing it to me. They are delighted; I feel at home, officially, in Africa.

Field Journal, July 2, 1982

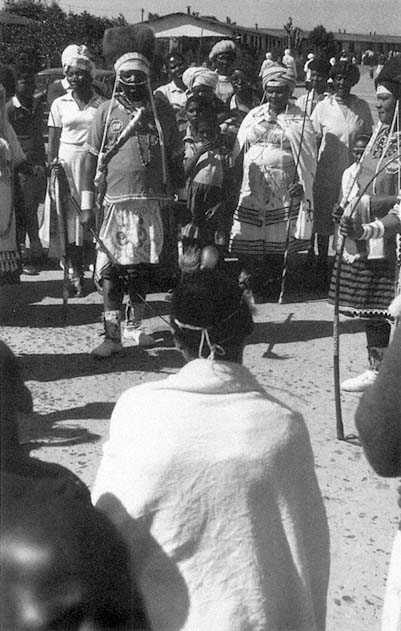

At a "washing of beads" in a Cape Town township: A cross section of black Cape Town, showing great kindness and hospitality toward us. Indeed, it seemed they were seeking approval of the outside world. We heard unusual statements such as "we're not cannibals, drunkards, and uncivilized people" as the government would have everyone believe. They urged us not to be afraid of them. We assured them we weren't, otherwise we would not have come. They kept asking us if we were happy, and offered us chairs, drinks, food to welcome us ... the men sought constant physical contact, to touch, hold or shake hands, as if to indicate their humanity through vicarious recognition.

Field Journal, November 14, 1982

This ethnographic survey is intended to sketch an impressionistic picture of cults of affliction in Central and Southern Africa, particularly in the contemporary urban settings of Kinshasa, Zaire; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Mbabane-Manzini, Swaziland; and Cape Town, South Africa. These national capitals represent the urban syntheses of four major regions of Africa respectively: the Congo basin, particularly Western Bantu-speaking societies; East Africa, particularly the Swahili-speaking setting; the northern Nguni-speaking setting; and societies influenced by Nguni, Sotho-Tswana, and Khoisan and by South African urban

societies of the Western Cape. In each setting some attention will be given to the historical backdrop of cult-of-affliction origins in these regions.

The impressions assembled here can hardly be expected to be systematic. However, they are firsthand authentic portrayals of the subject of the book. Through the conversations with healers and patients, officials and scholars, they reflect some of the thinking on the role of Central Africa's affliction cults in bearing the load of the caring vocations.

The "Grands Rites" Of Kinshasa

Kinshasa, Africa's largest city below the Equator, with about 3.5 million inhabitants, covers over two hundred square kilometers on the banks of the Zaire River. Local scholarship speaks of "les grands rites," representing numerous regional and ethnic traditions from around the Congo basin.

The local society of Kinshasa, and approximately half of its inhabitants, are of the Kongo-speaking (or Kikongo) society, of Lower Congo, or Zaire. From its beginning as the village of Kinshasa, then as the capital of the Belgian Congo, and after independence in 1960, as the capital of Zaire, Kinshasa has drawn residents from the entire region. The civil wars of the postindependence era and the deterioration of rural infrastructure and standard of living, together with the lure of the city, have led to the migration of many people to the city to seek their livelihood. Population expansion far beyond the ability of the city to provide an infrastructure of electricity, sewerage, and even water, has given rise to enormous suburban villagelike settlements. These population movements into the capital have brought with them the religious, therapeutic, and social forms of the regional cultures. From the Luba area of the Kasai region, one finds Bilumbu; from the upriver Mai-Ndombe region of Bandundu, Badju and Mpombo; from upriver in Equateur Province around Mbandaka, Zebola and Elima (or Bilima); from the Upper Zaire and Kivu, Mikanda-Mikanda; from Bas-Zaire and Bandundu provinces, Nkita; and from East Africa and Kivu, Mizuka.

Buttressing The Lineage In Western Bantu Society

Of the major cults of affliction represented in Kinshasa, the most characteristic of Western Bantu society—coastal Kongo, eastward into

Bandundu—is undoubtedly Nkita. Not only is the focus of its therapeutic ritual, the lineage, at the core of the society, but it is ancient. It is mentioned in early historical documentation on the Congo coast, as well as in accounts from Haiti, where it has become an element in the loa system. Nkita is associated with bisimbi nature spirits, and, as a lineage cult, is often involved in the regeneration and maintenance of lineage government. The bisimbi invest, or validate, lineage authority, which in many regions is embodied in powerful medicinal and religious compositions, the minkisi . Nkita concentrates on the dynamics of the matrilineage and the individual affliction believed to originate from lineage problems. The cult cell is within the lineage itself, frequently originating in the crises of segmentation and the need to renew leadership (Bibeau et al. 1977; Janzen 1978; Lema 1978; Nsiala 1979, 1982; Devisch 1984).

The history of lineage and public cults of affliction is significant in coastal and Western Bantu society. Given the prominence of fairly fixed settlements, landed agrarian lineages, and of markets and trade, and of—especially coastal and Southern Savanna—chiefdoms, this is not surprising. However, few of the early institutional forms have been adequately studied. The close articulation of emblems of authority, social renewal, and healing is common. My work on the historic Lemba cult that emerged in the seventeenth century in the context of the great coastal trade bears this out (Janzen 1982). Lemba represented a ritualized concern for several dimensions of society—the maintenance and protection of alliances between landed and prominent lineages; protection of the mercantile elite from the threat of envy by their subordinates due to their accumulation of wealth; the maintenance of trade routes overland between the Atlantic coast and the big markets of the interior; finally, the resolution of contradictions that resulted from the social upheavals caused by the great trade. There will be occasion to return to Lemba as an example of a public cult of affliction later in this book.

As in many cults of affliction, nkita is at once the name of the illness, the spirit behind it, and the therapeutic rite. The sign of affliction in Nkita is frequently expressed in diffuse psychological distress, dreams, and fevers, or threat to the continuity of the lineage in the form of children's illnesses or deaths, the barrenness of women or couples, or lingering sickness of male leaders. These problems are often associated with the suspicion of inadequate leadership, or at any rate a loss of contact with the bisimbi or nkita spirits in which lineage authority is vested. An individualized version of Nkita therapy concentrates on particular

cases that, if cumulative and serious, may trigger a collective therapy that seeks to renew leadership through the resolution of conflicts and the reestablishment of harmonious relationships with ancestors and nature spirits.

The Nkita rite, following the identification of the individual or collective diagnosis of the cause of the misfortune, requires the "quest for nkita spirits" in a river at the outset of the seclusion of the sufferer. These spirit forces are usually represented in smooth stones or lumps of coral resin found in appropriate streambeds, and they become the focus of the identification of the sufferer with the spirits. The seclusion of the sufferer-novice and instruction in the esoteric learning of Nkita is the first stage of teaching by the Nkita leader. The site or domain of this seclusion, a common feature of all ngoma initiations, is in Kikongo called vwela and refers to the forest clearing or the enclosure of palm branches, set apart and sacralized for this purpose.

Because of the lineage focus of Nkita and simbi spirit mediation, the rites attendant to Nkita have a close connection to, or arc done concurrently with, other rites that perpetuate collective lineage symbols, such as shrines bearing ancestors' mortal remains (nails, hair, bits of bone), leopard skins, chiefly staffs, sabers, or other signs considered to bear the spirit and office of past leaders. In some of these parallel rites, ceremonial couples, such as the Lusansa male and female priests, provide the personification of the continuous spiritual line. Instances of sickness or infertility in lineages associated with these rites may precipitate the nomination of new priestly couples.

In urban Kinshasa, according to psychologist Nsiala Miaka Makengo, who surveyed Nkita extensively in the mid-1970s (1979, 1982), there are an estimated forty to fifty "pure" Nkita practitioners, a figure that does not, however, include those whose practice is limited to their own lineages. The full rites, done with a full-fledged nganga Nkita are expensive and complex, thus beyond the reach of many families. Cost and availability of drummers, musicians, supporting personnel, transport to the site, and coordinating the whole ritual have become problematic. Thus, Nkita practitioners have tended to become generalized therapists for Kongo and non-Kongo people, in which non-kin join the seances, and the rituals become generalized for a range of conditions. Nsiala found that these Nkita healers receive on average five cases per day that require hospitalization, either in their compounds or another hospital, and up to a dozen cases that can be treated and released (1979:11). Of these, 40 percent were male, 60 percent female. They

came in all ages, distributed as follows: Children from birth to five years (15 percent), youths up to sixteen years (50 percent); adults (35 percent). Despite the apparent trend for the Nkita healers to become generic urban healers, their work continues to reflect the dual levels of the individual and the collectivity. Although the majority of cases are individuals, unique family or lineage therapies have evolved in the urban setting. These include mutual confessions, the group confessing to the sufferer, lifting the potential harm of malefic medicines, and holding veritable "psychopalavers" to vent the aggressions that exist within the group. These mechanisms of group renewal are frequently interspersed with divination to seek further understanding as to the internal group reasons for misfortunes.

God, Jesus, The Ancestors, And Janet In Luba Divination

Bilumbu, of Luba-Kasai origin, reflects the same emphasis on the core points of the social structure, in this case the patrilineage. Like Nkita, it has experienced significant changes with the urbanization of its clientele. The kilumbu (singular of bilumbu ) is a medium of the spirits who interprets the misfortunes of others. Bilumbu mediums enter this role after having their own possession or disturbances, and having been told by diviners that they have bulumbu , that is, the gift of prophecy or divination. The bilumbu, as well as the chiefs (balopwe ) in Luba society, are the individuals who legitimately interpret buvidye , the quality associated with bavidye , the founding spirits of the Luba nation (Booth 1977:56; Roberts 1988).

Observation of a Makenga variant—"to work for those who need it"—of the Bilumbu rite in Kinshasa in 1982, however, makes very plain that the urban rite, at least this one, has changed significantly from what it was earlier. After many generations of male mediums in a particular patrilineage, a woman had become the central medium of this particular cell. The "generalization" of divination and therapeutics, which has already been mentioned in connection with Nkita healers, was also evident in this instance of Bilumbu.

Kishi Nzembela, a woman of about sixty years, mother of eight, grandmother of twenty-two, carried on her lineage's Luba divinatory and therapeutic tradition. Zairian psychologist Mabiala ma Ndela, who accompanied me on this visit, had known Nzembela for some time and regarded her work as somewhat atypical within this tradition.

Nzembela "owned" or "managed" the spirit of her deceased daughter Janet, although all buvidye holders within the Nzembela line of mediums and spirits had been males for at least four generations before her.

Nzembela prefaced our discussion of her ancestors, and her daughter Janet, with emphatic affirmations that she was a devout Catholic and believed in God and Jesus, and that these must be named before any ancestors in an invocation. The walls of her small chapel featured two painted portraits, one of the Christian Trinity, the other of her daughter Janet.

Nzembela's entry into this work had begun in 1956, eight years after the death of her daughter Janet at age eighteen. Janet, a cripple, had been a talented, dynamic person and a leader, having been elected to head a group of handicapped children. She was also a gifted singer and had wanted to pursue a career as a singer. She had been possessed by spirits and claimed the gift of spiritual healing, as well. At eighteen, in the course of a pregnancy that seemed to the family to go on interminably, she died of complications. The family had also at that time had trouble with the police at the market.

Janet's spirit visited the family in 1956, when her brother, a soldier in training in France, was possessed following a sickness he could not overcome with help in hospitals. In his dreams, Janet instructed the family to give her a proper burial, to construct a beautiful tomb. Her brother did not wish to become a medium, so Nzembela, the mother, offered to do it for him. In a family celebration, a beautiful tomb was dedicated (in the byombela rite with the ngoma drum), and a feast was held following the sacrifice of a goat and four chickens. Having done this, Kishi Nzembela received a vision in which her mother, Madila, told her there was no conflict between the work of Janet and membership in the Catholic church. She was instructed to continue attending church, although on hearing of her possession, the church threatened her with excommunication. She went to the priest with her dilemma. After her presentation of her visions, and the priest's affirmation of how beautiful they had been, she received his blessing. If her work was evil, it would destroy her; if it was good, she would be blessed.[1]

She has continued working with the spirit of Janet and has had many mostly Luba clients from within and outside the family, including a few whites. Nzembela does not divine and heal on Sundays, the days she prays and worships. Weekdays, she is very busy. Some clients enter into trance quickly, others need pemba , white powder, sprinkled on them to achieve it. Nzembela offered that her own behavior may affect the

degree to which Janet will come to clients. If, for example, she has done wrong, Janet will hesitate. Sometimes Janet journeys to Europe to visit her siblings, in which case she will not respond to singing and chanting in Nzembela's seances.

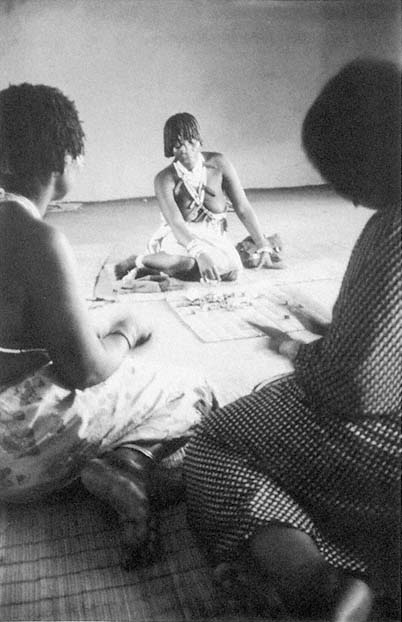

As we arrived to visit Nzembela, she was singing and shaking two rattles. Five other persons were seated on the floor inside the chapel, either singing or in trance (fig. 1). Nzembela had already taken care of one healing case earlier in the morning. Mabiala and I were invited to join those seated before her. All present were given white powder to put on their foreheads and at each temple, so as to be able to "see clearly" the things of the spirit. Nzembela and an assistant were wearing white coats with a red cross on the lapel. As the singing and rattle shaking became more intense and Nzembela distributed dried tufts of an aromatic plant to inhale, several of the participants began waving their hands about. Nzembela was leading the rhythm, but it was her young assistant who first became fully entranced and provided the central mediumship role for the seance. This woman was a client of several months, about twenty years old. She had been married, but her husband had not paid her family the bride price, and he had left her with a young child. Her family was angry with her and the young man. She was under great stress. Nzembela had taken her in to work and counsel with her.

When the young assistant, following the singing, became possessed with Janet, she announced—in an altered voice—Janet's greeting. Thereafter, "Janet," in a painfully distorted voice, spoke about each case before her, in turn, interspersing her comments with addresses to "Mama" Nzembela, telling her what she was seeing in the cases. The case of another young woman's affliction, she said, resulted from her "witchcraft" of having lured her sister to Kinshasa. Her abandonment of her rural parents had generated conflict in the family. She would need to be cleansed and reconciled with her parents to be whole again.

The young medium, possessed with Janet, turned to me and asked about my marriage. When I assured her it was good, she wanted to know with what problem I had come. I decided on the spur of the moment to mention a work-related problem. "Janet" said, and this was confirmed by Nzembela, that there were indeed persons or spirits who were trying to hurt me, even though they had not succeeded in doing so. The medium gave me some pemba powder to put on my forehead and temples, and under my feet and under my pillow, to help me in dreams to see the truth about my situation. This would also return the evil intentions back upon their perpetrators.

Figure 1.

Kishi Nzembela's compound in Kinshasa, Zaire: (a) Nzembela's

therapeutic chapel decorated with paintings of Jesus and the angels, and

daughter Janet; (b) storeroom; (c) patrilineal ancestors' shrine with wooden

figures depicting particular persons; (d) matrilateral female ancestors'

shrine; (e) tree shrine with base painted with white and red dots; (f) water

tap; (g) latrines; (h) living quarters.

Another seance began with Nzembela, shaking the rattle, singing her hymnlike song about Jesus and God who had saved us and Janet who would bring solace. A young man was in deep prayer, as if trying to enter trance to see his problems. Nzembela picked up a second rattle to intensify the rhythm and to bring the young man into trance, but he did not come. Later she took up his case in a semiprivate counseling session and listened to his complaints and miseries. Presently the young woman assistant entered trance, "Janet" again greeted "Mama" and the others and then turned to the young man to divine his case. Through the assistant, "Janet" said she could not see his problem behind his dizziness and loss of memory. She then turned to her own child. "Janet"

began thumping on the child, holding it between her legs, rolling around, while the child screamed. "Janet" said the child had a bad spirit of death in it. The child's mother (in trance) was evil, and the child was in terrible shape. I feared that this outburst of self-negation by the young woman would hurt or even kill her infant. However, this did not happen.

Further cases were more mundane. There was the woman who wanted to find out why her husband's Mercedes had crashed. He had seen bad spirits, said Nzembela. A woman whose husband was roaming around unfaithfully, "Janet" accused of wrong actions toward her husband.

The voice of "Janet" lapsed and Nzembela, as herself, began listening, occasionally offering advice, to the quiet young man who had been sitting in the corner throughout all this. She moved close to him, "in therapy" now, and spoke softly to him, prohibiting him from thinking of suicide. She encouraged him to pray, to take white powder, and to return next day for cleansing. The others present also received similar counsel and attention from Nzembela.

She also told of a case of a white man's family that had come to her for the presentation of their problem: his failing business and a marriage that was breaking up. During the divining and therapy session the family's daughter went into trance and revealed that her husband, a Latin or Italian, was from a people who had something against her own people, the Flemish. Her ancestors were against her marriage to him. After some confessions and the revelation of other problems, this family was helped to resolve their differences.

Apart from the young apprentice who had entered possession several times, it was unclear how many of these clients would eventually be drawn into a network of similar Bilumbu medium-healers. The session ended when all the clients had been dealt with for the morning.

Urban Changes In Cults Of Affliction

This brief account of two urban cults of affliction from the Western Bantu setting, both emphasizing lineage or family mediation, does not exhaust the range of types and regions represented in Kinshasa. It hints of some of the changes that cults of affliction undergo with urbanization.

Zebola, which originated in the upriver Equator region, manifests itself in physiological and psychological sicknesses of individual men and women. In its historic rural context, Zebola affliction is usually traced

back to possession by nature spirits. A regimen of seclusion, counseling, and ritual therapy brings the clients, mostly female, back to health through therapeutic initiation in the Zebola order. In its urban setting, especially Kinshasa, Zebola possession is frequently diagnosed in cases of women who are pathologically affected by isolation from their peers or families in their urban households. Becoming a Zebola sufferer and neophyte puts the individual into permanent association with a peer group of fellow sufferers, and through therapeutic initiation, eventually gives the individual a leadership role in the wider Zebola community and network.

Ellen Corin's penetrating study of Zebola (1979), both in Equateur Province and in Kinshasa, demonstrates that the women and (a few) men who enter Zebola are increasingly from a variety of cultural backgrounds beyond the upriver Equator region. She notes that the therapeutic initiation, which lasts for months or years, brings the isolated individual into close bonding with others, and from obscurity to a recognizable ritual position in the society. Trancelike behavior inspired by Zebola spirits is less marked in the city than in the countryside.

Mpombo and Badju (Bazu) originate from the Mai-Ndombe region a few hundred kilometers upriver. Zairian psychologist Mabiala, who is studying these cults, notes that a variety of ill-defined signs and symptoms are the modes of affliction here, including dizziness, headache, lack of mental presence, skin rash, lack of appetite, difficulty in breathing, heartburn with anxiety, rapid or arhythmic heartbeat, fever with shivers, sexual impotence, dreams of struggles, or being followed by threatening animals; weight loss or excessive weight, especially if accompanied by spirit visitations; and a variety of gynecological and obstetrical difficulties. Therapeutic initiation also characterizes the entry into the cult of the afflicted.

Mizuka in Kinshasa is a cult of affliction brought to the city and represented largely in the Swahili-speaking community. Men and women are initiated following psychic crises, hallucinations, nervousness, weight loss, weakness, dizziness, and bad luck (Bibeau et al. 1979). Other cults of affliction in Kinshasa include Nzondo, Nkundo or Elima of northern pygmy influence, Mikanda-Mikanda, and Tembu.

Mabiala (1982) has summarized the recent trends in Kinshasa cults of affliction in both negative and positive terms. The high cost of living in the city has driven many people to become healers to earn an income. Many of these individuals are not well trained and have promoted widespread charlatanism. In the village, where most people knew one another and where authority was more intact, this was not so common.

Many people, seeking solutions to their problems, fall victim to the charlatans who hide their incompetence behind a mask of anonymity and fakery, claiming to be competent in whatever their clientele seems to need. This willingness to broaden the competence of the therapeutic focus for increased business, Mabiala and others call "excessive generalism." This, however, also reflects the continued adaptability of traditional medicine in the face of a changing variety of problems, including the broad and vague conditions that may lie behind specific organic symptoms. The importation of a therapeutic tradition into an urban setting far from where it has been learned or originated may lead, in certain circumstances, to a greater degree of abstraction of the principles involved in the selection and combination of medicines and techniques. If specific plants or materials called for in the recipe are not available in the city, substitutes may be selected based on the dictates of underlying principles. A final, negative development Mabiala sees is the trend of African healers to mimic Western medicine. They may modify their practice with technical items such as stethoscopes, microscopes, syringes, and of course the white coat and the "doctor" title.

On the positive side, Mabiala notes the progressive detribalization of therapeutic rites. Clients' willingness to consult healers of language and cultural traditions other than their own permits a greater adaptability to urban conditions and circumstances. The exchanges of therapeutic knowledge that result from healers themselves receiving treatment in cultural contexts other than their own, or being in "isolation" with another tradition's care, has the effect of spreading and enriching the knowledge base available for all. At the same time, there tends to be a rejection of those techniques that seem irrelevant or obsolete. A very positive development in African therapeutics is the addition, to this therapeutic base, of ideas of hygiene acquired by reading, from mass media, or through more focused programs by agencies promoting public health. The encouragement of healers' organizations by the government and the formation of a variety of such groups has also been a positive development, giving greater visibility to healers and bringing recognition by scientists and health-care agencies.

Ngoma On The Swahili Coast

One of the foremost common characteristics of the cults of affliction of Kinshasa and Dar es Salaam is that they are rituals imported by immigrants from all regions of the nation. In Tanzania these cults of afflic-

tion from the coast and the interior are differentiated around particular themes and issues; they are also ethnically diversified. In the urban setting, their practitioners continue the particular emphasis of the classic rite. But they also are sensitive to the changing expectations upon healers in the urban setting and may shift their emphasis to new issues.

Despite the diversity of cults from across Tanzania and the tendency for them to become generalized to the urban setting, there is a sense in which cults of affliction are more homogeneous in Dar es Salaam than in Kinshasa. The term ngoma is widely recognized as connoting performance, drumming, dancing, celebration, and ritual therapy. This understanding of ngoma means that the performances are independent of the healing functions, leading to a distinction between ngoma of entertainment and of healing (ngoma za kutibu ).

The dominant community of ngoma therapies in Dar is that of the coastal Zaramo and Zigua peoples. An important work devoted to the subject by Finnish ethnographer Marja-Lisa Swantz (1979) identifies the major indigenous ngoma as Rungu, Madogoli, Killinge, and Ruhani. Many other distinctive ngoma rites have been identified among immigrants to Dar from coastal cities and the islands. A Kilwa healer practices ngoma Manianga and Mbungi. Another ngoma cell group of healers practices Msaghiro and N'anga. In addition to these ngoma of coastal societies, one also finds ngoma of inland groups in Dar. The BuCwezi cult of the lake region is found in the city, as are those of other Western Tanzanian societies such as the Nyamwezi, the Sukuma, and even some Nilotic groups such as the Maasai. The extensive writing on ngoma in Sukuma society near Lake Victoria may be summarized briefly for its excellent portrayal of a backdrop to some of the national activities that occur in ngoma today.

A Classic Profile Of Ngoma In Sukumaland, Western Tanzania

The Sukuma people, studied extensively by Hans Cory earlier in this century, offer a rich and elaborate array of historic ngoma comparable to that described among the Ndembu by Victor Turner. Cory, an Austrian ethnologist who worked for the British colonial government, left both extensive published and unpublished archival notes, now housed in the African Studies Center Library of the University of Dar es Salaam. These documents illustrate varied approaches to classify and understand the ngoma associations.

According to Cory, some ngoma were devoted to ancestor worship and divination: Ufumu, on the paternal side; Umanga, on the maternal side; Ulungu and Luwambo specifically belonged to particular clans. These ngoma Cory called "non-sectarian churches," since individuals could belong to several at once, and they were never intolerant of one another. Mabasa was joined by parents of twins and was concerned with the ceremonial cleansing of twin children. Other ngoma Cory saw as guilds for the study and practice of particular arts and occupations. They formed strong, disciplined fraternities, involved in mutual assistance and the protection or perpetuation of professional and technical secrets and obligations. These included: Uyege, for bow-and-arrow hunters of elephants, which had evolved into a fraternity and dance society; Utandu, a type of guild for rifle hunters of elephants; Uyeye and Ugoyangi, for snake handling and treating of snake bites; Ununguli, for porcupine hunters; Ukonikoni, a guild of medicine men devoted to witch finding; and Usambo, a thieving or thief-catching society. Ugumha (or Ugaru) and Ugika were ngoma societies without discernible function other than performance in dance competitions. Salenge was a mutual aid and dance society into which only the leader was fully initiated. Uzwezi (or Bucwezi), which had come to the Sukuma from Usumbara, and Migabo, which had come from the Swahili coast, had, after being concerned with the ancestor worship of certain clans, evolved into generalized dance societies (Cory 1938).

Cory, the colonial ethnologist, thought that the ngoma orders among the Sukuma had a positive role because they did not meddle in politics. In the absence of other Sukuma initiations, they instructed the youth in respect for elders, provided social solidarity, and instilled fear of the consequences of neglected social obligations. Thus they contributed to social stability. They also offered outlets for artistic and histrionic expression. The dance competitions he saw as generally positive, although they took much time away from the peoples' work in the fields.

Ngoma Of The Land, Ngoma Of The Coast

The particularism of naming in the Sukuma ngoma setting suggests that there is much innovation and adaptation in the overall idiom. In ngoma of the Dar es Salaam Swahili coast, the proliferation of orders arises at least as much from specific spirit classes as from particular functional specializations. Whereas the ngoma association names appear to offer a particularized view of ngoma, spirit classes diagnosed

to possess afflicted individuals are generalized into two or three groups. Among the coastal Islamized peoples, spirits are called masheitani or majini, both Arabic-Swahili words. The distinction between the two is not as important, apparently, as that distinguishing spirits of the water from those of the land, with some occasionally identified with the beach or coast. Thus, Msaghiro is an ngoma for sufferers of chronic and severe headache caused by a combination of Maruhani, Subizani, and Mzuka spirits, all coastal or beach spirits. Each of these classes is subdivided. The Subizani, of whom there are ten, are beach or rock spirits; some are male, some female, who have to do with children, both making them ill and helping to raise them to health. N'anga ngoma is a manifestation of Warungu spirits of the land, hills, baobab trees, and mountains; their mode of affliction is chronic severe headaches. Frequently each spirit type will be "played" in an ngoma ritual by a particular type of instrument. Not surprisingly, it is the major inland spirits that are usually represented by the classic single membrane ngoma drums.

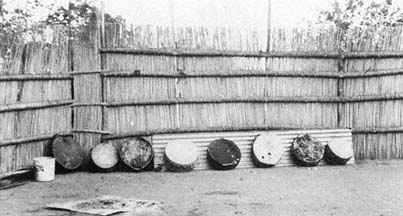

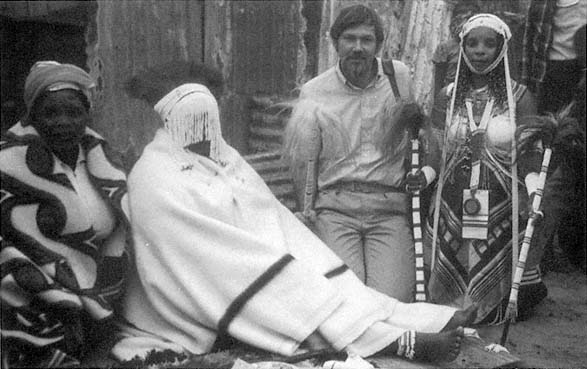

Emmanuel Mshiu and I. A. J. Semali of the Traditional Medicine Research Unit had arranged for me to see Botoli Laie, a healer they knew from their surveys, to work with ngoma. Botoli was a Mutumbe from coastal Kilwa who lived in the Manzese locality of southwest Dar es Salaam, not far from the main road but back in the villagelike area filled with houses surrounded by banana and palm trees and lush gardens. Botoli was home, with his two wives and children, and yes, he would gladly talk. And yes, he did work with ngoma: Manianga and Mbungi. His house was large for the area, with a raised courtyard suitable for ngoma performances and a mazimu ancestor shrine in one corner (see fig. 2).

Botoli had become an mganga (healer) in 1952 and had obtained the ngoma dimension of his work apparently without sickness having drawn him into it. I asked him whether he had suffered prior to his initiation. "No," he said, he hadn't been sick, but he was called to do ngoma Manianga and Mbungi after he was in practice. He resisted it, but then went ahead anyway.

Botoli was a vigorous man who talked in an authoritative voice. He willingly answered my questions, ready to show me the basic lines of his work with ngoma. He was a full-time healer, established with a well-built house, exuding a cohesive ambience. His children and two wives listened attentively to our conversation.

"Ngoma Manianga," he said, is used to deal with spirits of the interior of the country, that is, from Tabora and other regions across

Figure 2.

Compound of Botoli Laie in Dar es Salaam; (a) house; (b) ngoma

drums kept here; (c) ngoma performance area; (d) mazimu ancestral

shrine; (e) tomb; (f) consultation and medicine room; (g) stream lined with

banana trees.

Tanzania and East Africa. These masheitani are ten in number: Makogila, Ali Laka, Akiamu, Akolokoto, Akimbunga, Amiyaka, Akitenga, Ananditi, Chipila, and Ndwebe. When people are affected with these masheitani, they have bodily weakness, loss of weight, or general bodily swelling; they get shaking of the body, headache, and loss of appetite. They need then to be treated, to be taken through the course of treatment including specific materia medica from the mkobe (medicine basket), as well as dancing.

For his work with ngoma Manianga, Botoli uses a simple costume consisting of a red blouse and matching skirt, with designs sewn on the blouse (see plate 7). His paraphernalia include a small ngoma drum (musondo , also used in puberty rites) sometimes a smaller double membrane drum, and about ten sets of gourd shakers. There were also sets of cloths in red, black, and other colors, associated with various spirits. The strings Botoli wore around his shoulders had red, white, and black bags sewn onto them, which symbolically articulated cosmological oppositions such as the domestic versus the wild and land versus water. Each of his ngoma included a medicine basket (mkobe ), in which he

kept a collection of a dozen or so small jars and tins of medicines specific to the ngoma. (This set of ritual items is strongly reminiscent of the nkobe of western Kongo.)

Ngoma Mbungi has much the same paraphernalia: drums, shakers, and mkobe . The five ngoma drums of Mbungi represent five up-country masheitani: Mchola, Matimbuna, Mbongoloni, Chenjelu, and Kimbangalugomi, each of which is roused and manipulated by its own drum. The instrumentation also includes two wooden double gongs, which Botoli demonstrated. The resemblance between this ngoma kit and those of the Southern Savanna-to-Kongo region is striking and raises questions about their common history. Further research is needed to establish the approximate historical connection in the spread of these rituals across the mid-continent. Were they products of the coast (Kilwa)-Tabora-Kigoma trade route in the nineteenth century and earlier? Or were they the product of an even earlier common framework?

Botoli said he works with five to seven other waganga (healers) in the ngoma rites when the performance is at his house and he is the leader; elsewhere the host for that event is the leader. He noted that he has had many novices and was still in touch with them through ngoma events, although he could not give their precise number.

Although Botoli owns the instruments that are part of the paraphernalia of each ngoma of which he is healer, he is not the expert drummer in the rites. For major rites he hires drummers who are noted for their skill; they need not be novices or patients. The performers who do therapeutic ngoma are thus the same as those doing secular ngoma, or ngoma for circumcision, or any other festival or ceremony. It is the context and content of the songs, then, that identifies ngoma as therapeutic.

Ngoma Dispensaries, Fee-For-Service Ritual

Further insight into the organization of ngoma in Dar es Salaam was afforded by a visit in Temeke District of Dar es Salaam with the Hassan brothers, who are prominent in the Shirika la Madawa ya Kiasili, a coastal organization of healers. I was accompanied by E. K. Makala of the Ministry of Culture, whose music and dance section not only sponsors ngoma dance competitions around the country but also is conducting research on the song-dance aspects of therapeutic ngoma.

Mzee Omari Hassan's house is also his clinic. The main hall and sev-

eral side rooms and the back court were loosely filled with sick people and Omari's family. In this family all three wives helped care for the sick, as well as the two sons. The wives were introduced at one point, then disappeared; the sons were allowed to participate in the talks and even asked questions later. Omari's brother Isa, who is also a healer, came by at one point to say hello.

This particular tradition had been transmitted from one generation to the next in the patriline for a long time, well before the time four generations ago when the family had converted to Islam. Omari and family are of the Wazigua tribe, of the Bagamoyo District. He had moved to Dar in the 1940s.

Omari Hassan spoke of the way he had learned the teachings of healing from his father. His father, like himself, had involved his children in the work. The children would go along with him to search for medicines in the forest, and he would explain details to them. Similarly, Omari involved his family; the children play the ngoma drums in the rites.

As in the case of Botoli, Omari's ngoma techniques had been picked up as part of his occupation, rather than in connection with an ordeal of sickness and possession. He specifically denied having been sick with the diseases that were treated through the ngoma he knew. All six had been learned from his father, and were very old: Msaghiro, for persons suffering chronic headache, if no other cure is forthcoming (small drums resembling tourist drums are used); Madogoli, for treating mental disturbances in persons with a high state of agitation; N'ganga (or N'anga) for incessant, severe, migrainelike headaches; Manianga, for persons with numb or paralyzed limbs, especially on one side of the body (shakers are the instrument here); Lichindika, for lower-back pains, when persistent; and Kinyamukera, for those suffering from an affliction whose signs include partial loss of eyesight and twisted mouth or face. When asked how many ngoma he had performed the previous week, Omari indicated that it had been about fifteen, that is, several per day. This occurred in the context of up to fifty patients per day frequenting his clinic.

This picture of ngoma differed from the one I had encountered earlier. Rather than a sufferer-novice being initiated to a cell or network, this style of treatment resembled a clinic with a doctor and many public clients. Was this the result of urban complex society, or of professionalization, in which the rituals are taken over by a specialist and dispensed to patients?

Omari treats a variety of cases with herbs and mineral medicines. When asked what his most frequent cases are, he mentioned cancer, diabetes, asthma, gonorrhea, hemorrhoids, headaches, backaches, mental disturbances—in other words, he tries his hand at about anything. Makala told of how Omari Hassan had treated a boy with a distended eyeball, after this child had been to the State Hospital at Muhimbili and they could not do anything for him. A picture taken by Dr. Emmanuel Mshiu had been in the newspaper with a write-up of traditional medicine as a resource. The eye had been put back, or had retreated back into its socket, following Omari's treatment. When asked what cases he would refer to hospitals, he said, "ordinary sickness" but not sheitani (spirit) sicknesses.

I tried to determine how Omari related his work as mganga ngoma to Islam. He had studied in Koranic school, as had some of his sons. When asked which order he belonged to, he said "Muhammadiyya," unwilling to commit himself on whether he was Sunni, Shi'ia, or Sufi. When asked about those Muslims who believe their Islamic belief will not permit them to practice ngoma rituals, he said that was an indication of their not being well trained. They do not know about ngoma. A competent Muslim doctor has to use ngoma, if one is confronted with sheitani -caused illnesses. Ngoma, he said, helps the patients to express their anxieties and to perceive treatment methods from the sheitani as they speak through the sufferers.

Omari's guidance for his therapeutic work came from another source, an Arabic text. He showed me a thick book, "from Egypt," without title or author (it had been rebound and started on page 15). He also kept notebooks in which he recorded some of his own techniques and interpreted them for his sons. He said that he had not added to the very old ngoma his father had taught him, but that he had improved on some of the methods. He also showed me notebooks (Swahili in Arabic script) in which he copied and interpreted medical practices from the book, as well as his findings about plants and ngoma techniques. This gave evidence of the active codification of African herbal and ritual therapy in interpretative writing, alongside whatever version of Islamic medicine this book offered.

Omari's involvement in the Organization of Traditional Medicine, Shirika la Madawa ya Kiasili, meant that he could practice in an authorized ngoma dispensary. The organization, with branches in Dar, Bagamoyo, and Morogoro, utilized these dispensaries for their meetings and their therapeutic sessions. Omari showed me a file of corre-

spondence with the government, dealing with the Shirika's organization and with government authorization. One letter authorized him to practice on condition his place be checked annually by someone from the Ministry of Health.

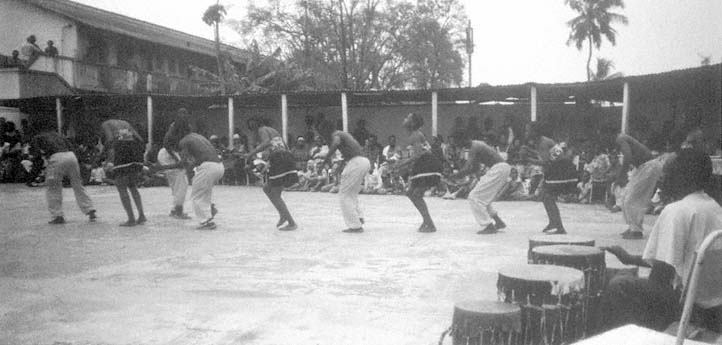

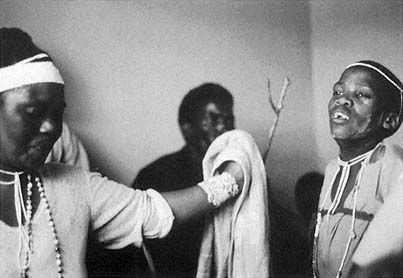

During another visit I was witness to performances of ngoma Msaghiro and N'anga. We received the same welcome as before; little children came to meet us and took our bags from us for the last part of the walk. We again received Pepsis. Omari came in and welcomed us, although he dashed off again to make preparations for Msaghiro and N'anga. We sat for a time, and Makala of the music section of the Ministry of Culture chatted with an Msukuma fellow and with another man, dressed in a suit and dark glasses, who said he represented the political party in power. Another individual was a patient, and a second said he, too, was a patient, but he also turned out to be involved in a healers' organization with the Hassan brothers.