Preferred Citation: Howse, Derek, editor. Background to Discovery: Pacific Exploration from Dampier to Cook. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3489n8kn/

| Background To DiscoveryPacific Exploration from Dampier To CookEdited by |

Dedicated to the late

JOHN HORACE PARRY,

who should have been editing this volume

Preferred Citation: Howse, Derek, editor. Background to Discovery: Pacific Exploration from Dampier to Cook. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3489n8kn/

Dedicated to the late

JOHN HORACE PARRY,

who should have been editing this volume

Preface

Since 1968, the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), has annually appointed a Clark Library Professor, sometimes from within the University of California, sometimes from elsewhere. One of this person's tasks is to organize a series of seminars on some chosen theme relating to the particular interests of the Clark Library—English culture during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Each seminar is addressed by an eminent visiting scholar invited by the Clark Professor. While faculty members and graduate students from UCLA and other southern California institutions make up most of the audiences, the seminars are advertised and open to all, often attracting scholars from outside the area. The texts of these Clark Professor lectures are generally published; a list of the published volumes faces the title page of this book.

Early in 1982, the distinguished English historian of maritime and Latin American affairs, John Horace Parry, CMG, Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs at Harvard University and former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Wales, accepted an invitation to become Clark Library Professor for the academic year 1983-84. For the Clark Professor seminars during 1983-84, he chose as his theme Background to Discovery: England from Dampier to Cook—roughly speaking, maritime explora-

tion (or rather the background to it) from 1680 to 1780, mainly in the Pacific, because the main thrust of exploration during that period was there. This was a field in which he himself had made many contributions as a historian.

By mid-1982, Parry had already contacted many of the speakers who eventually contributed, including the present editor. Then, very suddenly, on 25 August 1982, John Parry died at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, aged sixty-eight, immediately following a foreign lecture tour. The present editor, who retired from the post of Head of Navigation and Astronomy at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England, in October 1982, accepted with great humility the invitation to become UCLA's Clark Library Professor for 1983-84.

With the general theme of Background to Discovery: England from Dampier to Cook, the seminars took place at the Clark Library, Los Angeles, once a month from October 1983 to May 1984. The series opened with the lecture "Seapower and Science: Perspectives on the Motives of Exploration in the Eighteenth Century," by Daniel A. Baugh, Professor of English History at Cornell University, setting the scene and giving the underlying motives, political and economic, for eighteenth-century exploration. The November lecture, "The Achievement of English Voyages of Discovery, 1650-1800," by Glyndwr Williams, Professor of History at Queen Mary College, University of London, and President of the Hakluyt Society, 1978-1982, gave the story of the voyages themselves. In December, Seymour Chapin, Professor of History at California State University, Los Angeles, in his lecture "The Men from Across La Manche: A Brief Overview of French Voyages of Scientific and Geographic Discovery, 1660-1790," broadened the political field by detailing French exploration activity during the same period.

The 1984 seminars concerned specific subjects within the main theme. The January lecture by Charles L. Batten, Jr., Professor of English at UCLA, was entitled "Literary Responses to Eighteenth-Century Voyages of Discovery."

In February I explained the state of the art in navigation and the physical sciences in "Navigation and Astronomy in Eighteenth-Century Voyages of Exploration." The March lecture was by another scholar from England, Nicholas Rodger, Assistant Keeper at the Public Record Office, Kew, Richmond, and Honorary Secretary of the Navy Records Society since 1975—"The Royal Navy and Its Archives," an amusing and sometimes provocative paper. The April lecture, "The Noncartographical Publications of the Firm of Mount and Page: Some Problems and Opportunities in Eighteenth-Century Maritime Bibliography," was given by Thomas R. Adams, John Hay Professor of Bibliography at Brown University and formerly Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library. The last lecture of the series, given on 25 May 1984, looked at the subject with an eye to the fine arts—"The Sailor's Perspective: British Naval Topographic Artists," by John O. Sands, Director of Collections at the Mariners' Museum, Newport News, Virginia. One aspect which we would have liked to include was natural history—botany, zoology, anthropology, and so on, all important in eighteenth-century voyages of discovery—but, alas, this did not prove possible, though the topic is of sufficient substance that it may one day form the subject of a seminar series on its own.

The texts of all but two of these lectures are published here. The lectures by Professor Adams and Dr. Rodgers, not quite so closely connected with exploration as were the others, have been published elsewhere.

I am grateful to all the contributors for making the series the success I believe it was, and my sincere thanks must go to the Director of the Clark Library, Professor Norman J. W. Thrower, to the Librarian, Dr. Thomas F. Wright, and to all the library staff, for making each seminar such a pleasant and satisfying occasion.

DEREK HOWSE

SEVENOAKS, KENT

Contributors

Charles L. Batten, Jr ., is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Los Angeles. In Pleasurable Instruction (University of California Press, 1978), he investigates the generic convention of eighteenth-century travel literature. He is currently tracing the influence of eighteenth-century travelers on philosophical controversies in England.

Daniel A. Baugh is Professor of Modern British History at Cornell University. He is the author of British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole (1965) and the editor of Naval Administration, 1715-1750 (1977), and he has written articles on both maritime and non-maritime subjects within the period from 1660 to 1830. He is presently writing a book on Great Britain's "Blue-Water" policy from the sixteenth to the twentieth century.

Seymour Chapin is Professor Emeritus of History at California State University, Los Angeles. He has published extensively on the history of French science, scientific institutions, and scientific voyaging in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Derek Howse was the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1983-1984, having retired the previous year as Head of Navigation and Astronomy at the National

Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. Among his publications are The Sea Chart (with M. Sanderson, 1973), Greenwich Time and the Discovery of the Longitude (1980), A Buccaneer's Atlas (edited with N.J. W. Thrower; University of California Press, forthcoming), and Nevil Maskelyne, the Seaman's Astronomer (1989).

John O. Sands is Manager of Administration in the Collections Division of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. He was previously senior curator for the Mariners' Museum, Newport News, Virginia.

Glyndwr Williams is Professor of History at Queen Mary College, University of London. A former president of the Hakluyt Society, his main research interest is the exploration of North America and the Pacific in the eighteenth century. His most recent books are (with P.J. Marshall) The Great Map of Mankind: British Perceptions of the World in the Age of Enlightenment (1982) and (edited with Alan Frost) Terra Australia to Australia (1988).

I

Seapower and Science:

The Motives for Pacific Exploration

Daniel A. Baugh

Among the principal expanses of ocean there were three whose geography remained substantially unknown to Europeans at the beginning of the eighteenth century: the Arctic, the Antarctic, and the Pacific. The Pacific, still generally called the South Seas (Mer du Sud, Mar del Sur), was the prime focus of curiosity. Its uncharted regions were suspected of containing not only many more tropical islands but also considerable landmasses in temperate latitudes. Eighteenth-century explorers investigated the Arctic and Antarctic mainly to facilitate development of Pacific routes: Their object was either to find a short passage via the Arctic or to discover and secure places suitable for refreshing ships' crews along the two lengthy cape routes, both of which skirted the Antarctic.

European curiosity about the Pacific Ocean intensified suddenly at the end of the 1690s. Soon thereafter Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift, to name only the most famous of early eighteenth-century English authors, put the grow-

ing curiosity about the unknown ocean to various literary and loosely philosophical purposes. Granted, the plots of Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver's Travels both required some sort of "men from Mars," and in those days the Pacific seemed to provide the most plausible source and setting. But there also arose at this time a quasi-scientific curiosity about the South Seas. This was enhanced enormously by William Dampier's charming yet incisive and faithful accounts of his voyages. His first account was published in 1697.[1] Moreover, there was a firm popular belief, especially in England, that the commercial and strategic potential of the South Seas was enormous.[2]

All these infatuations spread remarkably during the first two decades of the century, and if nothing more than curiosity and enthusiasm were needed to launch expeditions, a flurry of exploratory activity in the Pacific, led by the English, should certainly have commenced by about 1720. Nothing of the sort occurred. The years 1697 to 1760 saw only four significant voyages of exploration in the Pacific, that is, voyages properly equipped and primarily intended for exploratory purposes: one by an Englishman, Dampier; two by a Dane, Vitus Bering, who was hired by the tsar of Russia; the other by a Dutchman, Jacob Roggeveen. Thus, notwithstanding the heightened curiosity early in the century, the major powers of Western Europe mounted only two exploratory voyages—Dampier's and Roggeveen's—before the 1760s.

This eighteenth-century period of delay was really the latter portion of a longer period, roughly 120 years, in which very little effort was made by Europeans to unlock the secrets of the great ocean. This period, stretching from the 1640s to the 1760s, separates two great ages of Pacific exploration. The first age was long and drawn out; it lasted from about 1510 to the 1640s. Then came the 120-year period of fallow. The second age, signaled by the voyages of Bougainville and Cook, ran from the 1760s to about 1800; exploratory voyages in the Pacific did not thereupon

cease, but all the main cartographical outlines were filled in by 1800.

Two questions are raised by these chronological facts, and they constitute the main concerns of this essay: Why was there a 120-year lapse of exploratory effort? And in what ways, if any, did the leading motives of the 1760s and 1770s differ from those of earlier times? As to the first question, some historians would not agree that there was a 120-year lapse. It will be necessary, therefore, both to establish the limiting dates clearly and to offer an explanation of why the lapse occurred. The second question, regarding differing motives, lies at the heart of my interpretive theme.

Perhaps the most famous person to comment on the question of differing motives was the great Polish-English writer Joseph Conrad. He judged that the era of Cook's voyages marked a fundamental change:

The voyages of the early explorers were prompted by an acquisitive spirit, the idea of lucre in some form, the desire of trade or the desire of loot, disguised in more or less fine words. But Cook's three voyages are free from any taint of that sort. His aims needed no disguise. They were scientific. His deeds speak for themselves with the masterly simplicity of a hard-won success. In that respect he seems to belong to the single-minded explorers of the nineteenth century, the late fathers of militant geography whose only object was the search for truth.[3]

Conrad appears to be focusing here on personal motives, but he would not have denied the influence of culture in shaping personal motives. He is, in fact, contrasting modern, disinterested, scientific exploration with the exploratory venturing of the bad old days of blatant acquisitiveness. (The passage is suffused with esteem for nineteenth-century liberal virtue.) As we shall see, this historical contrast is broadly valid, but not so starkly as Conrad implied. One need only recall from the earlier period the conduct of Columbus, Verrazano, Torres, the Nodal brothers, or Hudson to be reminded that there were men of those times whose desire to be honored for sedulous

and dangerous navigation seems to have matched, and possibly exceeded, their desire for material gain. And if Captain James Cook's motives were "free from any taint" of "the desire of trade or . . . loot," that was partly because as an officer of the Royal Navy he belonged to a well-established and respected professional corps. Within that institution he could look forward to material and social advancement as well as honor, if he did his job well.[4] Very few explorers of the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries were in anything like that position. The institutions of their times were less solidly established.

In this essay, however, we are concerned not with the personal motives of the explorers but rather with the motives that underlay decisions to finance the voyages. To put the matter bluntly, Cook's voyages were expensive and obviously he did not pay their costs. The expenditures for his three voyages were authorized by the British government within a framework of objectives that could be expected to stand up to taxpayer scrutiny. Similarly, Dampier was expected to pursue objects that "may tend to the advantage of the Nation." Lord Keynes's remark, "For only individuals are good, and all nations are dishonorable, cruel and designing," although perhaps unduly bitter, has a bearing here.[5] In short, it is one thing to say that an explorer's motives were purely scientific and professional and quite another to say that the motives underlying the decision to finance his voyages were equally of the same character.[6] Even in our own time, when the pursuit or maintenance of scientific preeminence is generally acknowledged to be a motive sufficient unto itself, considerations of national power and prosperity set limits on public appropriation of funds for exploratory research.

Our theme therefore requires us to step back from the voyages themselves in order to examine the kinds of motives that got the explorers their authorization and funding. We shall find that throughout the whole period from 1500 to 1800 one consideration never ceased to be of primary importance: great-power politics. But we shall also

discover that the geopolitical perspective of ministers of state did begin to change in the 1760s and 1770s.

In the end we shall see that the surge of exploration in the Pacific during those decades was carried forward by a convergence of three broad motivating forces. One of them had operated powerfully from the sixteenth century onward and never ceased to operate: the inclination of the European powers to parcel out the world and its resources—le partage du monde , as Fernand Braudel has spoken of it—in which process the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) between Portugal and Spain stands as one of the earliest and greatest landmarks.[7] Although traces of the second motivating force might be seen in the sixteenth century, it did not crystallize as a powerful force in Western Europe's policy-making until the later part of the seventeenth: this was the development of a widespread public appreciation of the role and importance of seapower. (The focus on seapower was not the same thing as le partage du monde ; its rationale and policy implications were considerably different.) The third was a force whose promise was first announced by Francis Bacon in the 1620s; however, it did not attain the power to open large purses until the middle of the eighteenth century: a new conception of the role of science. This conception held that knowledge of the natural world should be pursued not only for the glory of God and man but also because such knowledge translates to prosperity and power. In this view, any society whose capacity for acquiring knowledge is inferior or merely derivative must therefore expect to hold an inferior and derivative role in global affairs.

The impact of the second and third of these motivating forces, seapower and science, forms the concluding theme of this essay. More immediately our task is to place all three forces in the long historical context of exploration in the Pacific, taking notice not only of their influence, stage by stage, but also the conditions and developments that at certain times overrode them and thus inhibited exploration.

The First Age of Pacific Exploration (ca. 1510-1640s)

The European exploration of the world's largest ocean may be said to have begun either with the penetration of Indonesian waters by the Portuguese in the decade after 1510 or with the circumnavigation by Ferdinand Magellan's ship (1519-1522). Whichever beginning is preferred, it must be granted that the "year 1519 was indeed a year of destiny for the Pacific. A month before Magellan sailed from San Lucar, the city of Panama had been founded."[8] The first age of exploration may be divided into two phases. The initial phase was dominated by the Iberians and lasted about a century. The Spanish played by far the dominant role—largely because after about 1520 the Portuguese concentrated their energies on integrating a trading system based on the Indian Ocean.

What were the Spanish trying to achieve in the Pacific? This question raises the larger question of the motives of Spanish imperialism. The familiar historical answer is that offered by the conquistadors: to seek gold and to serve God. Certainly these goals were approved by Ferdinand and Isabella and their successors. Yet Columbus himself repeatedly sought and was expected by his backers to find an alternate passage to the Indies, so that Spain might enjoy the same profits of trade in spices that Portugal seemed to have within its grasp. Just five years after the conquest of Mexico, Cortés was urged by dispatches from the Spanish court to launch exploratory expeditions in the Pacific (from the west coast of New Spain). The Philippine Islands were finally reached from America in 1543. It took another thirty years for the Spanish to work out a practicable return route, and until the correct method was found (by sailing in more northerly latitudes where the winds were favorable) dreadful losses were incurred from lack of water and shipboard diseases. Hence it was not until the 1560s that "the Manila galleon" could be instituted; Spanish trad-

ing with the Indies became an accomplished fact seventy years after Columbus's first voyage.[9]

Clearly this exploratory thrust across the Pacific had an ambitious yet narrow purpose: to reach the islands discovered by Magellan, to establish a trading center there, and to learn how to get back. Along the way other islands were inevitably discovered, most notably the Marianas (Guam was settled for a watering and refreshment station), but once the correct routes were known most voyages adhered closely to them. The exceptions were the voyages of Mendaña and Quiros, in pursuit of gentlemanly and religious goals, and the voyage of Torres (an experienced pilot of Portuguese extraction and low birth), the first great explorer of the waters around New Guinea.

The voyages of Quiros (1606) and Torres (1610) marked the end of Spanish transpacific probing. Thereafter the policy of the Spanish Empire reflected an awareness of inadequate and declining resources. The result was a defensive posture marked by an almost paranoid attitude toward foreign intrusion, particularly in the Pacific Ocean.

The preceding sketch represents the less familiar, oceanic side of Spain's thrust in its first and greatest century of overseas expansion. It ignores what are generally regarded as the key developments: the impact of silver, the encomiendas , the Christian missions, the conquest of Peru, and so on. But it reminds us that the Spanish crown did not abandon the original purpose of Columbus's voyages. Although the large expedition (seventeen ships) that comprised his second voyage might seem to have reflected a change of priorities, it really reflected only a change of plan. Hispaniola was to be settled with Spaniards and sprinkled with cattle chiefly that it might serve as a marshaling point for further exploratory attempts to find a sea route to the true Indies. In the meantime, the aim was to enable the colony to support itself by gold discoveries and plantation products, following models established principally by the Portuguese at Madeira and other Atlantic islands.[10] To be

sure, when silver was discovered on the mainland in great quantities, development of territory proceeded apace. But before then development of territory was by no means the clear-cut primary goal of the crown. In the early decades Castilian authorities were undecided as to the course of empire, and there were strong pressures in favor of continuing to seek out a path to the Indies.[11] Of course the Spaniards who migrated generally cared nothing about this, and it was they, plus the discovery of silver, that set the dominant style of Spain overseas.

The amazing energy and persistence of Spanish expansion in the sixteenth century, fully exemplified by not only the conquistadors but also Mendaña, Quiros, and Torres, was blanketed in the early seventeenth century by a protective conservatism that proved to be profound and enduring. In this regard the influence of the crown, whose concerns were primarily centered on Europe, was decisive. The cost of maintaining Spain's European dominions, though diminished in the seventeenth century by a less ambitious policy, remained heavy. From Madrid's viewpoint, therefore, nothing was more important than the continuance of plentiful bullion supplies from America. There were even moments when the crown considered abandoning the Manila galleon. Since Manila was essentially an entrepôt at which Oriental luxury goods destined for New Spain were traded for silver, Manila appeared to be diverting the all-important silver flow away from the mother country.

This protective conservatism had a pervasive effect on the general pattern of Pacific exploration. It not only curtailed Spanish exploratory activity but also constrained the initiative of other nations. As thinking in Seville, Cadiz, and Madrid became increasingly preoccupied with the narrow aims of shielding the monopoly of Spanish-American trade and the bullion lifeline, a lifeline that traversed a small corner of the Pacific Ocean, the possibility that the Pacific might be better known or "opened up" could only be regarded with foreboding. In fact, a major reason why

the crown could never bring itself to abandon the Manila trade altogether was the strong probability that some other nation might eagerly fill the role. That nation would not only break the trade monopoly but also seek to dominate the Pacific coast of the American empire and thereby command the fate of the indispensable silver shipments from Peru to Panama. Because the seventeenth-century Spanish Empire was usually destitute of means to police its Pacific shores and sailing routes, it saw its best hope in preserving their inaccessibility. The obvious policy was to discourage anyone, even Spaniards, from finding out anything that might entice other Europeans into establishing a foothold nearby. Accordingly, the achievement of Torres was virtually suppressed,[12] and the first circumnavigation of Tierra del Fuego by the Nodal brothers—an impressive voyage which exhibited effective command, navigational skill, and seamanship—was largely obscured.[13]

From a legalistic viewpoint the government of Spain had long regarded the entire ocean from the Philippines to the New World as an exclusive Spanish preserve. During the seventeenth century, and most of the eighteenth as well, Spain treated its vast claim to the Pacific as would a manufacturing company that has obtained a patent in order to suppress its use. The Manila trade, which was the culmination, however disappointing, of the initial excitement about westward access to Eastern riches, was the sole and rather reluctantly pursued exception.[14]

The first age of Pacific exploration was not yet at an end, however. In the decades after 1600 the Dutch converted a prolonged struggle for independence into an aggressive global maritime war against the Iberian powers; they did not hesitate to ignore Spanish claims. By 1625 the Dutch East India Company had effectively expelled the English from the Indonesian archipelago and pushed the Portuguese to the perimeter. In the 1620s the worldwide expansive energy of the Dutch was at its peak, and no other nation was better positioned to embark on further probing of the Pacific. Yet the Dutch exploratory effort was initially

delayed, and after it did begin it was quickly aborted. Although the governors-general and councillors at Batavia in the 1620s and 1630s were, according to their successors, "seriously inclined to send out expeditions for the discovery of the unknown regions," they had wound up giving other matters priority.[15] At last in the 1640s, while Anthony Van Diemen was governor-general, two voyages for this purpose were sent out in quick succession. Their main objectives were, first, to learn more about the "Southland" (Australia), whose coasts and adjacent sea passages were only slightly known; second, to find and claim for the States General any unknown lands which might lie east of the Southland; and, third, to be "better assured of any eventual passage from the Indian Ocean into the South Sea, and to prepare the way for ultimately discovering a better and shorter route from there to Chili" (shorter because of the favorable prevailing wind in southerly latitutdes).

Upon examining the details of the instructions one is struck by the businesslike and practical outlook. The chance of running into civilized peoples was deemed to be slim; the objectives were realistic (Tasman by his two voyages did in fact validate many of the key expectations); and it was even recognized that trading to Chile might, at least initially, be forbidden by authorities in Amsterdam because Chile lay within the West India Company's sphere.[16] Tasman carried out his instructions competently, but no more than that. His main accomplishments were to establish the existence of the southernmost route from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific and to reckon the approximate size from north to south of the Australian continent. A report sent from the officials at Batavia to the company directors at the end of 1644 presented a calmly balanced assessment of the possibilities, problems, and requirements of dealing with the Australian landmass. The assessment was guardedly optimistic, but the task, they said, could not be hurried. They admitted that "investigating lands is not everybody's work," while adding: "God grant but one rich silver and gold mine, . . . to the solace of the general shareholders and honour of the finder."[17]

But the directors were not interested. In 1645, responding to a preliminary report from Batavia, they wrote a letter that effectively terminated all further exploration of both the Australian landmass and the South Pacific. As for attempting to investigate the southern landmass in hopes of discovering precious metals, the directors wrote:

We do not think it part of our task to seek out gold- and silvermines for the Company, and having found such, to try to derive profit from the same; such things involve a good deal more, demanding excessive expenditure and large numbers of hands; it is clearly seen in the West Indies [i.e., New Spain], what numbers of persons and quantities of necessaries are required to work the King's mines, so that gold and silver are not extracted from the earth without excessive outlay, as some would seem to imagine. These plans of Your Worships somewhat aim beyond our mark. The gold- and silver-mines that will best serve the Company's turn, have already been found, which we deem to be our trade over the whole of India, and especially in Taijouan and Japan, if only God be graciously pleased to continue the same to us.[18]

It was a sound, conservative, business decision. A century later Charles de Brosses remarked that the driving spirit of business was to make timely profits. When big commercial companies undertook voyages of discovery, he noted, they tended to focus on particular prospects of profit; upon encountering great expense or obstacles, they tended quickly to revert to their customary modes of commerce.[19] Certainly this describes the Dutch East India Company's policy in the 1640s. The company's success had been founded on ships, efficient commercial operations, shoreline establishments, and control of small enclaves and islands. Soldiers were expensive and the company tried to keep their use to a minimum. Investigation of Australia's interior therefore would have constituted a marked departure from the hitherto successful line of Dutch East Indian enterprise. The directors' refusal to undertake such exploration was consistent and understandable.

It is, rather, their refusal to countenance maritime exploration in the unknown parts of the Pacific that constituted a departure. They ruled out the possibility of a transpacific trade with Chile because that coast lay within the West In-

dia Company's preserve. Hence exploration of the seas to the eastward was useless. And, in the same vein as the Spanish imperial authorities, the directors hoped that the unknown land would remain unknown, "so as not to tell foreigners the way to the Company's overthrow."[20] Hitherto the directors had often been willing to assent to bold proposals from abroad, even where commercial prospects were distant or uncertain. In the mid-1640s, however, their policy changed.[21]

The change of policy was undoubtedly a reflection of the general pressure, especially financial, on the Dutch republic that began to take the wind out of its maritime expansion. The Dutch West India Company, whose objectives proved beyond its means, had begun to impose heavy demands on the taxpayers that appeared to have no limits. By the 1650s—in fact from then on—the Dutch Were on the defensive: the English attacked their commerce and Atlantic settlements by sea, and the French, in the 1670s, put pressure on their home borders by land. Although the directors of the East India Company were overly optimistic when they presumed that Japan and Taiwan would remain part of the eastern network, their commercial decision to stick to the profitable spice trade proved to be wise.[22] But as a result the Dutch East India Company, like the Spanish Empire, retained yet refused to exploit a diffuse monopolistic claim to the vast expanses of the Pacific.

Diversions and Deterrents (ca. 1640s-1760s)

Exploration is planned discovery. Discoveries may be made casually or accidentally, but those are not part of our subject. We have thus far traced the manner in which planned exploration of the Pacific came to an end by the 1640s. Our task now is to explain why the lapse persisted for 120 years. Basically there are two avenues of interpretation. One would emphasize diversions—other concerns, other

priorities. The other would emphasize deterrents—most of which related directly to the geographic and political situation in or near the Pacific basin. In some respects the two interacted, of course, but on the whole they remained separate.

Certainly there is a powerful case for stressing exogenous diversions. Key points would include the conservatism which enveloped Spanish and Dutch policy, concentration of English and French resources on colonial development in North America and the West Indies, and the task of improving trading opportunities in India. Perhaps the most important diversion of all was the peculiarly unsettled condition of seventeenth-century European politics, marked by an intensive yet highly unstable process of state building in the two emerging maritime powers, England and France; for this reason those countries were strongly inclined toward short-term goals. Furthermore, throughout the first half of the eighteenth century all European governments tended to concentrate on the immediate requirements of European rivalry and the balance of power.

Turning to the factors indigenous to the Pacific basin that tended to deter exploration, the most obvious was geographic—the Pacific Ocean's size, distance, and difficulty of access from Europe. Nevertheless, the monopolistic claims of the Spanish Empire and the Dutch East India Company did in fact play a powerful role in discouraging exploratory activity after the 1640s.

At first glance a historian would be tempted to deny this. Everyone knows that Spain's bold claim to the whole of North America was freely ignored by the English, Dutch, and French with impunity. Although seventeenth-century Spain made an effort to police its vital core of American waters in the Caribbean and near the isthmus, [23] practically nothing was done to guard the periphery. Similarly, the Dutch East India Company did not attempt to police any regions east of the Spice Islands. Thus, though trespassers were warned, the ocean between the Moluccas and the South American coast appears to have been wide open.

But in reality it was not. By themselves the inflated monopolistic claims were undeniably frail. But when taken in combination with circumstances of geography, the limited range of commercial opportunity, and the vicissitudes of European diplomacy, the claims wound up having a powerful influence on the history of exploration.

We begin by examining the ways in which the combination of these circumstances and the monopolistic claims tended to deter serious exploration. Then we will take up the influence of Atlantic and European diversions.

The size of the Pacific and its distance from Europe were of course unchanging factors, but however great the toll on ships and crews, these obstacles obviously did not deter exploratory efforts prior to the 1640s. There was, however, a third geographical factor: Ships could reach the Pacific only by the two southerly approaches, both of which—unless the voyage was very fortunate—entailed the hazards of human and material exhaustion. The fact that within a century of Magellan's voyage the two routes of access had come to be dominated strategically by the Spanish Empire and the Dutch East India Company constituted a considerable hindrance to other nations. These two powers might contrive to interdict the approaches, of course, but mainly they rendered the nearby shores hostile and hence substantially increased the risks of passage.

Let us first consider the South Atlantic approach. The discovery of the route around Cape Horn by Jacob Le Maire made it theoretically far more difficult for the Spanish to interdict this approach. But because the Spanish could scarcely afford the resources to guard either the straits or the cape route on a regular basis during the seventeenth century, Le Maire's discovery did not in reality make much difference. [24] The key problem was wear and tear on ships and crews. Both routes were arduous; voyages completing the passage often needed repairs and refreshment. The austere, rockbound coast of the far south, though unoccupied, was hardly suitable. Because of the pattern of wind belts it was prudent (necessary really) to

head north for quite a distance before striking out westward. Along this path there existed one useful point of relief, 600 miles off the coast and not occupied by the Spaniards: the island of Juan Fernández (Robinson Crusoe's island), where ships could find fresh water, fruits, and greens. It became a well-known refuge for early eighteenth-century English adventurers. [25] But because no accurate method of ascertaining longitude at sea existed before the 1760s, there was considerable risk of not finding the island. For instance, in 1741 Commodore George Anson, upon reaching the island's known latitude, mistakenly estimated that he was west rather than east of it and therefore began his search by sailing away from it; the consequent delay cruelly amplified the deaths from scurvy. As a result of Anson's use of the island, the Spanish undertook at long last to occupy and fortify it. [26] Since in 1741 Britain and Spain were at war, Anson's voyage was an expedition of war. In peacetime a foreign vessel in dire distress might venture to call at a South American port, but it was taking a chance, for the Spaniards assumed—almost always correctly—that foreign vessels in those waters were up to no good.

The importance of this inhibition to Pacific voyaging is further illustrated by the repeated efforts, made especially by the English, to find a Northwest Passage; these efforts were motivated by a desire to find not only a shorter route to the Far East but also a route which was well clear of Spanish power. As well, the flurry of excitement over the Falkland (or Malvinas) Islands in 1770, a feature of the second age of Pacific exploration, was founded on a British urge to possess a base for refreshing crews en route to and from the Pacific via Cape Horn.

On the other side of the Pacific there were, after Tasman's discovery of the passage south of Australia, two known approaches. The southernmost route was favorable only for eastbound voyages because of the prevailing winds. Access north of Australia passed through the Dutch preserve. Again, it was the need for a safe place to recu-

perate that mattered most. Two illustrations of the difficulties encountered by explorers because of the Dutch East India Company's attitude toward trespassing will suffice.

When William Dampier made his second voyage to the western Pacific, a planned voyage of exploration sponsored by the English government, he found his ship to be much in need of water and sought assistance at Dutch Timor. He sent his clerk ashore to tell the governor the nature of his voyage, and

that we were English Men: and in the King's ship. . . . But the Governour replied, that he had Orders not to supply any Ships but their own East-India Company ; neither must they allow any Europeans to come the Way that we came; and wondred how we durst come near their Fort. My clerk answered him, that had we been Enemies, we must have come ashore among them for Water: But, said the Governour, you are come to inspect into our Trade and Strength; and I will have you therefore be gone with all Speed. My Clerk answered him, that I had no such Design.

Agreeing to keep a distance from the fort, Dampier got the water. [27] This occurred in 1699, in the reign of William III. It was probably not a coincidence that Dampier's voyage of exploration to regions near the Dutch East Indies was authorized at a time when the English and Dutch heads of state were, to say the least, on good terms, being the same person. Even so, the Dutch reception of Dampier at Timor exuded hostility and suspicion.

The voyage of Jacob Roggeveen, who set sail from the Texel in August 1721 with two ships, provides our second illustration. It was also a genuine voyage of exploration, undertaken by arrangement with the Dutch West India Company. Roggeveen's aim was to try to find terra australis incognita , the great continent rumored to exist in the south central Pacific. He had some goods with him for trading with the new customers. After an extensive voyage, with provisions running low, he was forced to find relief at Batavia. Roggeveen had been worried about this eventuality and had written ahead requesting permission to put in there for supplies. To no avail. When he reached

Batavia ships, crews, and cargoes were detained. He had to return home in an East India Company vessel. [28]

To sum up the account at this point, we have seen that neither the Spanish Empire nor the Dutch East India Company was willing after the 1640s to undertake serious exploration. Although they were incapable of closing the Pacific to foreign intrusion, they were able to make repeated intrusions hazardous and thus to call into question the future usefulness of exploratory findings. Outsiders had to calculate that substantial and expensive force would eventually be required. The deterring consideration was not so much the hazard of the single exploratory voyage as the degree of commitment faced by sponsoring governments, syndicates, or companies if they wished to assure themselves of future returns. It is small wonder that most ventures in this period pursued quick profits rather than long-term goals. But of course serious, planned exploration generally presumes long-term goals; it is ordinarily a kind of preliminary research in which the benefit, if any, is to come from subsequent and repeated journeys.

There is no doubt that in some spheres quick profits could indeed be got, and this brings us to the question of commercial opportunities. At the outset, a negative point should be noted. Because the Pacific Ocean was distant and relatively inaccessible from Europe, its islands were not economically suitable for "plantation" products except for those which would not flourish in Atlantic regions. Similarly, its fisheries were too far away for the catch to be sold competitively in European markets (during the eighteenth century). These constraints ruled out two inducements that had played major roles in opening up the Atlantic and Caribbean.

The commercial opportunities that did exist in the Pacific during this 120-year period may be divided into five categories. First, the real and attainable but not glitteringly attractive: furs, skins, walrus ivory, whale oil, and minerals. Second, the real and attractive but probably unattainable: chiefly trade with Japan, which the Japanese kept

closed off except for a tiny window open to the Dutch; trade with the Spice Islands, tightly monopolized by the Dutch; direct trade to South America, about which more will be said in a moment; and a transpacific carrying trade between China and South America, which only the Spanish were in an immediate position to conduct through their entrepôt at Manila. Third, the real and probably attainable but essentially irrelevant to discovery of the unknown parts of the Pacific: chiefly trading between China and India. The fourth category does not perhaps deserve to be classed as commercial opportunity: the real though unknown and problematic. For instance, an exploratory voyage, if conducted assiduously, could hope to discover "rare commodities"—pharmacopoeial, culinary, or otherwise. If the plants that produced them could be made to grow on islands or shores nearer Europe, the eventual returns could be sizable. The search for valuable and exotic commodities was a commonly stated object of later eighteenth-century European exploration in the Pacific, even before Sir Joseph Banks applied his enthusiasm, wealth, and influence to the quest. [29] But clearly this sort of goal—not at all foolish—tends much more toward basic research than commercial viability. The fifth and last category of opportunities is impossible to ignore though it may appear strange on the list: the unknown and unreal. It cannot be ignored because it played a role in the resumption of European exploratory activity after 1760. Our concern here, however, is with the first three categories—the known and calculable opportunities.

It was the first category that led the Russians into the North Pacific in the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century these commodities (especially those derived from sea mammals) became an important foundation of Western European and American commerce in the Pacific, but their value-to-bulk ratio was not generally high and therefore the profit margins did not seem attractive in the early eighteenth century—except to the Russians. But the Russian situation was unique. In the seventeenth century the

Russian Empire had extended itself across all of Siberia and was probing Kamchatka. The drive had been fueled mainly by profits from furs and to a lesser extent by iasak , a tax payable in furs levied upon subjugated aborigines. The furs were chiefly sold by Russian entrepreneurs to China, and the tsar's treasury took 10 percent of the gross. By the early eighteenth century Siberian sources were showing signs of becoming depleted, but entrepreneurs, taking to the sea, were finding plentiful supplies in the Aleutian Islands. Thus Russian expansion into the "Eastern Ocean" was economically self-sustaining, indeed highly practical. The product could be conveniently sold in Asia, and a handsome income flowed to the tsar's treasury, which grew ever more needful of it as Peter the Great and his successors pursued militarily expensive ambitions in Europe. In fact, there is a strong case, contrary to the traditional view, for thinking that the primary purpose of the government's sponsorship of Bering's voyages, even his first voyage, was not to settle a geographical question but to lay a foundation for eastward expansion of the Russian Empire. [30] Obviously, in this period such commercial attractions could apply only to Russia.

Western Europeans when they eyed the Pacific were left to contemplate, among the known commercial opportunities, only the very faint hope that either Japan or the Dutch Spice Islands would be opened to them and the extreme unlikelihood of being able to mount a successful transpacific carrying trade. In the latter regard the most likely Asian country was China; it became gradually more accessible to the British in the eighteenth century. But the British East India Company stood in the way. China lay within its monopoly sphere, and in the later eighteenth century the growing trade between China and India was seen as essential to the company's financial viability. With the whole imperial position in India at stake, there was no chance that parliament or cabinet would allow a transpacific side-show unless the company wanted to undertake it, however much free-traders might rail against the allegedly con-

straining effects of the company's monopoly. The overall effect on British policy was to attach China to concerns in India rather than to new possibilities in the Pacific. [31] The French government, on the other hand, was from time to time prepared to close its eyes to the monopoly claims of its India company if there was money in it for a hard-pressed treasury to tax or borrow. [32] In the first two decades of the eighteenth century French trading vessels made more than a half-dozen voyages carrying Chinese goods to South America. These voyages fitted the description of a carrying trade, but they were in reality only a small adjunct to a much larger commercial enterprise of the time whose focus was South America—by far the most enticing of the opportunities on our list. To the South American opportunities we now turn.

In 1669, amid a burst of enthusiasm at court for distant commerce, two English naval vessels under the command of Captain John Narborough were dispatched to the nether part of South America "to make a Discovery both of the Seas and Coasts of that part of the World, and if possible to lay the foundation of a Trade there." The plan entailed charting, recording navigational data, and inventorying flora, fauna, and minerals. Perhaps most important of all, Narborough, while taking care to avoid contact with the Spaniards, was to "mark the temper and inclinations of the Indian Inhabitants" in hopes of making friends and preparing the way for trade. [33] The idea was far from new. Though such schemes repeatedly failed, the Protestant powers could not bring themselves to give up the hope that friendly natives, annoyed with Spanish rule, might provide access to the wealth of Peru. (Hendrick Brouwer had led a similar venture in the 1640s on behalf of the Dutch West India Company; he used force, and it ended in disaster.) [34] The English probe of 1669 ended in disappointment and minor losses. The mission and its results illustrated two key points: the tremendous allure of Peruvian treasure (chiefly the silver from Potosí) and the futility of English attempts to find a peaceful method of trading for it.

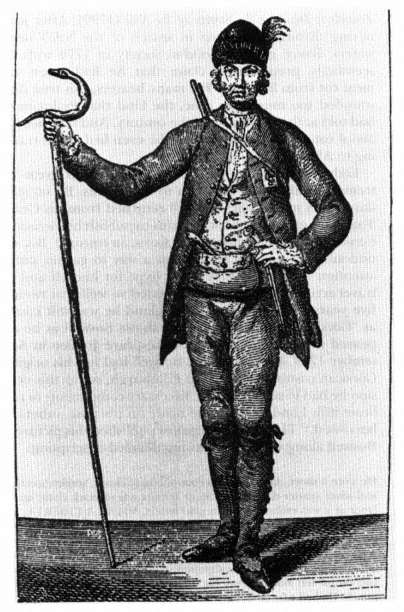

Narborough's voyage is properly classed as one of exploration. It was designed to gain geographical knowledge and to smooth the way for future developments, and he did succeed in obtaining data for some high-quality charts. As it happened, the English wound up devoting their navigational research to predatory rather than commercial purposes. There was further navigational "research" of a more casual sort: Bartholomew Sharp, during a piratical expedition upon the Pacific in 1680, managed to take from a Spanish ship her secret book of charts and sailing directions and bring it back to England. He reported: "The Spaniards cryed when I gott the book (farewell South sea now)." [35] One may well doubt that this cry was really voiced, but the point is easy enough to grasp: the era in which the Spanish could rely on the assistance of navigational ignorance to protect the west coast of America from foreigners had come to an end. [36] William Dampier's career illustrates the importance of buccaneering to the English. He began his nautical career in the South Seas as a buccaneer—in the same expedition as Bartholomew Sharp—and ended it in a similar manner with two privateering voyages during the latter part of the 1702-1713 war. Another English privateer of the period, Edward Cooke, wrote in the dedication of his published account: "I present a Voyage round the World, principally intended to reap the Advantages of the South-Sea Trade, whereof your Lordship is the Patron, and which prov'd successful in the plundering the Town of Guayaquil, on the Coast of Peru, and the taking of a rich Ship bound from Manila to Acapulco." [37] Cooke's manner of using the word "trade" is interesting. It neatly sums up the overall character of English enterprise on the west coast of South America at this time.

On the whole, the various English efforts to tap the wealth of that coast must be counted a failure—though punctuated here and there by some dazzling successes. Buccaneering in the reign of Charles II did not yield much success. The Darien scheme (1697-1700), aimed at siphoning Peruvian wealth at the isthmus, was wiped out by Spanish arms. The War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713),

which many enthusiasts hoped and believed would have the effect of securing direct English access to the west coast, yielded instead the Asiento privilege, whose stipulations explicitly forbade such trade. (In the treaty negotiations Spain obdurately refused the English request for a port of call on the coastline.) Even Anson's voyage during the war of 1739-1748 became a material success only by the lucky stroke of his running into a well-laden galleon near the Philippines. There had been so much noisy English enthusiasm, over so long a period of time, yet so little to show for it. [38]

Until about 1700 the French had no better access to the region than the English. After that the story was quite different. In 1698 a reconnaissance voyage by Beauchesne wound up paving the way for a new era. For by the time he returned home in 1701 France and Spain were united by a strong dynastic tie—the dying king of Spain had bequeathed the throne to Louis XIV's grandson—and a war to defend that inheritance was fast brewing. The Spanish navy at this point was moribund, so the task of defending the silver lifeline and the trading monopoly in wartime had to be given over—though Madrid did so with the greatest reluctance and misgiving—to the French. Because the approved imperial channels of trade to Peru had been cut off for almost a decade, the west coast was sitting on a great pile of silver and starved for European goods. At the end of the war of 1689-1697 the Compagnie de la Chine and the Compagnie de la Mer Pacifique (or Mer du Sud) had been allowed to form in order to provide employment for privateering crews and ships, especially those of Saint-Malo, upon which the monarchy had come to rely heavily for carrying on maritime warfare. [39] When war recommenced in 1702 the moment had come for direct French trade to the west coast. Wartime circumstances, extraordinary influence at the court of Madrid, and subterfuge at Versailles, as steady as it was shameless, produced a bonanza for the adventurers of Saint-Malo, La Rochelle, and other ports. Between 1695 and 1726 the figures show 168

French vessels venturing to the South Seas, of which 117 returned (26 were sold in America, 12 wrecked, 13 captured). More than half a dozen are known to have crossed the Pacific. [40] The Spanish were given to understand that it was all occurring without French governmental approval. After granting permission to some merchants of Saint-Malo to trade in the South Seas in August 1705, the king's minister, Chamillart, wrote to the minister of marine: "Since the king does not wish to give any public title or personal authorization to their enterprise, it is necessary for the passports to state some other purpose, such as going to our American islands, or going on exploration, or some other pretext." To the French ambassador at Madrid, who was raising questions, he wrote: "You may assure the Spaniards that the king has not given and will not give any permission to his subjects to go and trade in the American territories ruled by the king of Spain. All that have been issued are some permits given in the normal way for the French islands in America and for going on explorations." [41] The returns were enormous, and largely in the form of bullion.

On the one hand, this surge of lucrative trade actually tended, at least in an immediate sense, to deflect interest away from exploration of the unknown parts of the ocean. The many French voyages tracked along known coasts and routes, and although the government took steps to gather accurate navigational knowledge of the South American littoral, the character of the voyages was almost wholly commercial. On the other hand, these voyages demonstrated to the European nations the feasibility of regular sailings around Cape Horn (at least when the nearby shores were not guarded in a hostile manner).

Thus by about 1710 the Pacific Ocean seemed open. Ordinary merchantmen were sailing there, and the breach of the Spanish monopoly seemed irreparable. Yet, as it happened, there was only one serious exploratory effort in the epoch that followed—by Roggeveen, the Hollander, in 1722. Neither Britain nor France essayed a serious voyage

of Pacific exploration for the next forty years. And by the mid-1720s trade to the west coast was again closed to outsiders.

Both Britain and France deliberately allowed the Spanish monopoly to be restored. To explain why they did this is also to explain why the British and French governments did not encourage peacetime expeditions of any kind to the Pacific during the next forty years. The explanation is to be found partly in the Atlantic but mostly in Europe. Hence the last 40 years of the 120-year period of fallow are to be explained primarily by the influence of exogenous diversions.

Notwithstanding the attractiveness of Peruvian wealth, Britain and France had higher priorities. The final outcome of the treaty negotiations of 1713 made this clear: Both nations agreed to forgo direct trade with the west coast. In each case the policy was prompted by caution and therefore acceptance of the status quo ante, and during the next two decades this disposition suited well the inclinations of the leading ministers of state, Sir Robert Walpole and Cardinal Fleury. The calculations were nicely balanced. Britain feared that French influence at the court of Madrid, enhanced by the Bourbon connection, might secure to French merchants a continuing privilege of direct trade. The French feared that if their own direct trade to the west coast persisted, the burgeoning power of the British navy would be brought to bear in support of British contraband traders on that coast. It was for this reason that the French court decided it could no longer wink at the direct trading. [42] The two newly risen giants of maritime enterprise, warily eying one another, thus kept their distance from the Pacific except when Britain was formally at war with Spain.

France's general inclination to cultivate Spanish allegiance is a commonplace of eighteenth-century diplomacy. It is Britain's posture that requires explanation. Although Britain went to war with Spain three times between 1714 and 1750, British interests on the whole were well served

by the policy of trying to maintain peaceful relations with Spain. Of course, the proponents of aggressive maritime expansion did not agree; the popular cause—popular in London anyhow—mustered enough political support to bring on a major war with Spain in 1739. (On the other two occasions armed conflict arose more from Spanish than from British impetus.) Popular clamorings for war, however, were offset by British statesmen's concern not to put the export trade with southern Europe to hazard. During the fifty years after 1714 this trade was very important. [43] Within its orbit the Iberian peninsula played a major role both as a market itself and as a conduit for goods reexported to South America via Cádiz and Lisbon. Moreover, both Spain and Portugal bought large quantities of the most politically sensitive English export product: wool cloth. (Portugal was practically the only market in the world where English cloth exports expanded during the eighteenth century.) Finally, the trade balance with Iberia was strongly favorable to England, and the difference was made good in precious metals and coin. In fact, a prime reason for the expansion of Anglo-Portuguese trade in the decades prior to 1760 was the discovery of gold in Brazil in the 1690s. [44]

Over many centuries England had little difficulty in maintaining close ties with Portugal, both for strategic and for commercial reasons. Relations between England and Spain, on the other hand, were continually plagued by basic problems. Aside from the popular English enthusiasm for aggression in Spanish America, there were the potentially hostile Bourbon connection, the English wish to retain Gibraltar and Minorca (for strategic positioning against French seapower), incidents arising from contraband trading in the Caribbean, and other frictions. In view of these issues and the actual eruptions of war, it is all too easy to forget that during the half-century that followed 1714 British diplomacy generally tried to steer its way through the difficulties. It did this out of concern not only for the balance of power in Europe but also the substantial

commercial advantages of the trade with Old Spain. In 1750 a commercial treaty, highly beneficial to English trade with Old Spain, was concluded under auspicious circumstances, and Anglo-Spanish relations remained friendly until Ferdinand VI died in 1759.

Summing up the situation down to 1759, we may say that both Britain and France avoided the Pacific in time of peace in order to avoid offending Spanish sensibilities. In 1749, for example, the British cabinet canceled a projected voyage to the Falkland Islands and South Seas because Madrid learned of it and objected—this occurring at a moment when promising negotiations were under way concerning the commercial treaty signed in 1750. [45] But after 1759 British policy toward Spain underwent a significant change.

The seeds of change lay in the new Spanish monarch's mistrust of the British. By 1761 William Pitt, who had formerly valued Spanish neutrality (and the lucrative trading that went with it), believed that Spain was preparing for war and urged his cabinet colleagues to commence hostilities immediately. They refused and he resigned. But Pitt had read the drift of Spanish policy correctly: French counsels were prevailing at the court of Charles III and the following year Britain found itself at war with Spain anyway. For Spain had made a decision unequivocally, willfully—and disastrously as it turned out—to join France in the Seven Years' War.

This decision transformed the extended outlook for Anglo-Spanish relations, because it happened at a time when English politicians of an older generation—Walpoles and Pelhams—who had nursed relations with Old Spain as best they could for half a century were retiring from the political stage. The new men fretted far less about European ties than had their predecessors. Moreover, the trend of trade statistics in the 1760s showed that the relative importance of Iberian trade was declining rapidly. [46] Spanish goodwill seemed scarcely worth an effort. When peace re-

turned to Europe in 1763, an altered British attitude toward Spain soon became obvious. Hence the somewhat nebulous opportunities and concerns of the Pacific no longer had to be weighed against a concrete and compelling European case for not giving offense to Spain.

The Commencement of the Second Age of Exploration

Initially, we saw how the Spanish Empire and Dutch East India Company turned conservative and thus inclined toward keeping others and even themselves ignorant of the Pacific Ocean's geography. In the preceding section we noted that reliable access to the ocean was circumscribed by Spanish and Dutch monopolistic claims; that French and English activity on the west coast of South America between about 1700 and 1720 had much to do with immediate acquisition of wealth but little to do with exploration; and that during the period from 1713 to 1760 diplomatic and commercial considerations in Europe inhibited both Britain (when not at war with Spain) and France—the emergent maritime powers—from undertaking Pacific ventures because the Spanish so disliked them. Finally, we observed that in the early 1760s the third point lost most of its force as far as the British were concerned.

It is important to notice the kinds of deterrents and diversions that are being excluded. My inclination is to share Spate's doubts about the applicability to the history of the Pacific of long waves of economic expansion and contraction ("phase A" and "phase B") which some modern French scholars have put forward with skill and subtlety. [47] Moreover, Braudel's accent on the diversionary effect of the effort put into "building America" ("it was necessary to build America, which was Europe's task, in the long term ") is not detectable in the policies of the various European powers. His idea appears to be based on the energies and

efforts of colonists, but the logic of a diversion-of-effort argument must rest on what mother countries do, not what colonists do.[48]

But the most notable proponent of the diversion-of-effort thesis was Vincent Harlow, who stated it as follows:

The seamen and geographers of the Renaissance had devised the novel and daring expedient of establishing a means of communication with the Eastern World by sailing west across the unknown ocean of the Atlantic, but the unexpected discovery of the American barrier between Europe and Asia had caused a complete diversion of this outward movement. The Europeans who used the sea-routes opened by Cabot, Columbus, and other navigators of the time were not merchants on their way to the court of the Great Khan or the bazaars of Ophir, but conquistadors , sugar and tobacco planters, settlers, and coureurs de bois . For a century and a half the Europeans devoted their energies to the consolidation of the American inheritance, interspersing their activities with fierce quarrels among themselves. . . .

By the middle of the 18th century the Europeans were on the move again.[49]

Down to about 1700 this thesis has some validity. Undeniably, the "consolidation of the American inheritance" was the main preoccupation in the seventeenth century (though one should not forget the activities of the Dutch and English East India companies). After 1700, however, there was ample energy and eagerness available for the Pacific in London (and Saint-Malo too). We have seen that the British and French governments were unwilling to unleash it in peacetime. Moreover, when these governments did show interest in the Pacific in the 1760s, the "fierce quarrels among themselves" were by no means considered to be things of the past.[50] All in all, the diversion-of-effort thesis cannot surmount two historical obstacles: why the Spanish and Dutch ventured in the Pacific and East Indies before the 1640s and why the British and French did not do so from about 1720 to 1760.

Harlow's diversion thesis laid the groundwork for the main objective of his study, which was to show that British imperial policy underwent a profound reorientation after

1763. The new orientation was marked by two features: a preference for trade over territorial dominion and a "swing to the East," where the new trading opportunities were to be sought. ("The Second Empire began to take shape in the 1760's as a system of Far Eastern trade.") The "First" British Empire had got itself entangled with colonies of settlement, plantations, and the like, and these, he argued, entailed vexing political problems which came to a head in the 1760s and provoked a search for different methods in a different place. Britain's interest in the Pacific Ocean, signaled by the surge of exploratory voyages, her-aided the change.[51]

This is no place for a comprehensive critique of Harlow's schema. But the terms of the debate "on the questions of motivation and direction" of British imperial policy after 1763 have been set by him,[52] and he interpreted the commencement of British exploration in the Pacific during the 1760s as a leading indicator of "the swing to the East" and the new preference for commerce over dominion. Since our purpose here is to ascertain the motives and reasons for the timing of the second age of Pacific exploration—and in so doing to show that concerns over seapower as well as a new way of thinking about scientific research were paramount (and commerce was not)—it is necessary to confront Harlow's interpretation.

The basic flaw is that both of Harlow's key propositions are largely chimerical. The "swing to the East" cannot be substantiated by evidence of any type.[53] The other proposition, that British policy moved toward a preference for trade over dominion after 1763, is to be doubted on three counts.[54]

First, it is a profound error to suppose that the quest for dominion had ever been the mainspring of English imperial policy before 1763. Recently a very strange reinterpretation of the British Empire has been elaborated on the basis of a similar idea.[55] To accept it one has to perceive the empire throughout its earlier history as mainly a matrix of tributary arrangements designed to satisfy the patronage

needs and military predilections of a portion of the English governing class. Undeniably such a matrix formed a subplot and appeared dominant on some occasions and in some places, but it is beyond question that trade, plunder, and the defense of trade had always been the primary motive forces of English overseas policy before 1763.[56]

Second, there is the problem of Indian imperialism. If any imperial situation did accord with the idea that the main concerns were tribute, patronage, and dominion, it was the situation in India after about 1760. From then on the East India Company behaved more like a tax-collecting governing body than a trading establishment. The scope of its dominion expanded. In fact, the idea of a commercial "swing to the East," to the extent that it has any genuine substance (trade to China and Southeast Asia), tends to clash with the idea that dominion was shunned, because the urgent quest for these new avenues of trade was spurred by the need to find an economically viable method of supporting dominion in India within the framework of a private company. [57]

The third count is that in the 1760s British policymakers were still at least a half-century away from putting their faith in free trade. Rightly or wrongly, commerce was still seen as something that had to be husbanded and therefore carried on under conditions controlled by the mother country. In other words, trade continued to be conceived of as an "imperial" matter.[58] One may fairly say that Harlow was not denying this. His argument did not directly address the question of free trade but centered rather on a preference for trade over dominion—in the same manner, one might say, that the Dutch East India Company had preferred trade to dominion in the seventeenth century. The eventual development of British commerce under "informal empire" (that is, relying on economic rather than political sinews) appears to lend substance and plausibility to the argument. Still, Harlow's discourse at times verges near the authentic language of free trade. The British Empire was, he says, moving toward a commercial system "beneficent and profitable, imposing no restrictions and

incurring no burdens." He envisions a "network of commercial exchange extending through the Pacific and Indian Oceans. By opening up vast new markets in these regions, a diversity of exotic commodities, earned by home production, would flow back into British ports." This was what the architects of the "Second British Empire" were looking for: "The hope and intention was to find a vent for the widening range of British manufactures" by creating such a network.[59] The puzzle is that if finding a vent for the widening range of British manufactures was the main object, why was it desirable to search for the solution in distant and unknown seas while a booming trade with North America was admirably serving the purpose? Harlow does not address this point. Alexander Dalrymple, however, clearly did, and because Harlow derives a good deal of inspiration from him, Dalrymple's views on this question, published in 1770, are worth examining.

Dalrymple saw nothing but danger in the North American trade. His reason was unusual and highly relevant to our purpose. It was not the familiar objection that North America did not fit into the Old Colonial System but rather that the North American market was too successful in receiving British manufactured goods. The American colonists were thus in a position to put pressure on the imperial government; the mother country was too dependent upon them as buyers. "Discovery of new lands" and thereby new markets for British goods, he wrote, would diminish the "decisive importance" of the American colonies to the empire.[60] In other words, a new trading region and system were needed to keep the imperial-commercial system from becoming too dependent upon one region—particularly a region that, at the time Dalrymple was drafting these ideas, had become notably obstreperous about obeying the decrees of the imperial legislature.

The key point here is that Dalrymple's reasons for exploring new commercial realms do not accord with Harlow's. For Dalrymple's argument is essentially defensive in character: he insisted that Britain must seek to develop a controllable and counterbalancing alternative system. To

be sure, he spoke of "discoveries in the South Sea" leading to "an amicable intercourse for mutual benefit," but these benign and optimistic phrases must be evaluated in the general context of his imperial objective.[61] Whereas Harlow sees the thrust into the Pacific as something born of confidence,[62] Dalrymple saw it as an antidote to potential imperial disaster.

Upon turning to the true motives, we may begin by observing that the motives behind the British thrust to the Pacific in the 1760s and 1770s involved both moods: confidence and anxiety. There was in the early 1760s (as there had been for forty years) great pride and confidence in Britain's standing as the world's leading naval power. There was also a deep concern to do everything necessary to retain that position of naval preeminence. It is not a trivial fact that the British voyages of discovery were all organized by the Admiralty (with cabinet approval) and in each instance—John Byron, Samuel Wallis, Philip Carteret, and James Cook—the ships were commanded by officers of the Royal Navy. The primary objectives, both short-term and long-term, were directly concerned with seapower.

The initial strategic aim was to secure claim to the Falkland Islands, an independent way station for assisting ships on the Cape Horn passage; their possession, as Lord Anson had remarked, would make the British "masters of those seas." Anson was First Lord of the Admiralty and was thinking mainly of the problem of supporting naval expeditions to the Pacific in time of war, though he also spoke of the potential advantages of gaining a commercial foothold in Chile. The Earl of Egmont, the First Lord who presided over the dispatching of Byron's expedition, was thinking along identical lines. A secondary objective of the 1760s was to see whether any islands or continents existed in the Pacific which might be made to serve naval or commercial ends. But the immediate concern was a base in the Falkland Islands.[63] The Admiralty had pursued a policy of establishing permanent overseas bases since the 1720s; the interest in the Falklands harmonized with this trend.

But the secondary objective may have weighed just as heavily on the minds of those who looked to the future of British seapower. Their concern was to maintain a continued preponderance of the two main underpinnings of naval strength at that time: merchant shipping and skilled seamen. The Navigation Acts had been chiefly addressed to these ends; they were designed to facilitate a national merchant marine and thus to provide early training and subsequent employment for skilled British seamen who could be enlisted or impressed into the navy in wartime. The trouble with the vibrant, growing, industrially beneficial transatlantic trade with America was that it was being carried on increasingly in ships of the Thirteen Colonies, many of which never got near British ports. Moreover, impressment of "American" seamen (it was often a nice question what "American" meant in this regard) had been running into serious political and practical barriers. The seamen in the transatlantic trade thus appeared to be largely unavailable to the Royal Navy in case of need. This problem was plainly visible by 1763—well before American independence.

To those concerned for the future of the navy, therefore, the development of new arenas for British shipping seemed highly desirable.[64] And it was even more important to prevent the French from doing the same thing. Thus the British Admiralty was, in effect, buying insurance. The cost of all the British exploratory voyages of the 1760s was probably less than the cost of one ship of the line fully fitted—a reasonable insurance premium. The lords of the Admiralty did not need to suppose that possibilities of commerce were of much immediate importance; nor did they have to seriously believe that large, well-populated, undiscovered continents or islands existed. They only had to make sure the French would not be able to claim such places first.[65]

The question of underlying British motives in the Pacific, it might be noted, has given rise to an interesting debate on the decision to colonize New South Wales. In this

debate the revisionists argue that the government had something more in mind than a place to dump convicts when it chose Australia. The subject lies in the 1780s, beyond the bounds of this essay, but the theme is highly relevant. All in all, the case for a naval role is rather strong, but it does not nullify the importance of finding a suitable spot for the convicts. The case for a commercial role, however, seems to be rather feeble.[66]

In sum, then, the financial sponsorship of British exploration in the 1760s was motivated by a protective maritime imperialism . (One witnesses here an early instance of that phenomenon which became so characteristic of modern British imperialism and so exasperating in its apparent hypocrisy to Britain's rivals: expansion for defensive purposes.) The voyages to the Pacific were part of the ongoing global struggle between Britain and France. The key ingredients were national defense, rivalry, and pride. The voyages were undertaken not in a spirit of fulsome self-confidence but in the mood that purchases insurance. If prospects of commerce proved to be unreal or remote, the premium would nevertheless have been wisely paid.

Seapower also played an important role in the French effort, but allowance must be made for the differing commercial and naval situations of the two nations. It is well known that Charles de Brosses, whose work inspired Louis Antoine de Bougainville to go out to the Pacific, was an Enlightenment figure of some note, a savant fascinated by geography who like Dalrymple believed the "scientific" case for the existence of terra australis incognita to be very strong. De Brosses was also a fervent patriot convinced that France's future lay in maritime commerce and naval strength. The trouble was, he wrote in the preface to his Histoire des Navigations aux terres australes , that Britain ("a neighboring power") had appropriated to itself "la monar-chie universelle de la mer," without consideration or care for any other nation. It was that fact, he said, which gave birth to the book.[67] Inspired by reading de Brosses's book, Bougainville set out first to claim and establish a base on the Falkland Islands. He arrived there before Byron, whose