Preferred Citation: Healey, Christopher. Maring Hunters and Traders: Production and Exchange in the Papua New Guinea Highlands. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2k4004h3/

| Maring Hunters And TradersProduction and Exchange in the Papua New Guinea HighlandsChristopher HealeyUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1990 The Regents of the University of California |

In memory of Ralph Bulmer, scholar, teacher, and friend

Preferred Citation: Healey, Christopher. Maring Hunters and Traders: Production and Exchange in the Papua New Guinea Highlands. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2k4004h3/

In memory of Ralph Bulmer, scholar, teacher, and friend

Preface

The Maring are well known in anthropological literature, principally from Roy A. Rappaport's seminal Pigs for the Ancestors (1968). Until recently much of the considerable research among the Maring has taken an ecological approach, concentrating on subsistence agriculture and adaptation to the environment. Although I maintain this ecological orientation, I turn my attention to the exploitation of nonsubsistence, nondomesticated resources. In particular, I focus on the extraction of forest products, especially the hunting of birds killed for their decorative plumes, and on the organization of trade. Forest products have long been the only resource locally available to the Maring which are in high demand elsewhere in the highlands. It is through the production of plumes and other forest goods and their exchange that the Maring are able to provision themselves with other items that are important in prestations of social reproduction but are not locally available. Notable among these latter goods are marine shells and steel tools, which were still widely used in prestations into the late 1970s, along with cash and pigs. Although the latter are, of course, locally bred, significant numbers are also acquired in trade. Geographic patterns of trade and the nature of goods passed in transactions have, however, changed considerably over the last six decades. Many of these changes predated direct contact with the colonial authority. Others have come more recently as the state and the cash economy have increased their institutional pene-

tration of the Maring region. A major objective of this book is to document and analyze the changing nature of trade.

I argue that in the heyday of Maring trade from the period immediately preceding contact until the late 1970s, it was the passage of forest products that gave a dominating structure to the pattern of trading networks. This was a consequence of a combination of ecological and cultural factors. First, the significant deforestation of much of the central highlands means that many valuable plume-bearing birds—notably birds of paradise, parrots, and hawks—and other forest products, are to be found mainly in the more heavily forested regions of the highland fringes. Here, human settlement is generally sparser, affording hunters easier access to the bounty of the forests. In passing, it should be noted that this ecological situation is significantly influenced by past and continuing human action—the clearing of forest for gardens and, more recently, for timber and to make way for smallholder cash crops and larger-scale plantations and the like. As a consequence, game is increasingly confined to relict stands of mountain forest where it becomes ever more vulnerable to further disturbance of habitat and pressure from hunting.

Second, one finds a high cultural value assigned to bird plumes, marsupial pelts, cassowaries, and other forest products in a number of central-highlands cultures, notably the Simbu, Kuma, and Melpa. Here, such goods are important as items of decoration on ceremonial occasions and also for use in prestations. This high demand for forest products, coupled with a lack of their local availability—at least in sufficient quantities—sets up conditions for the emergence of networks of supply connecting more peripheral areas of the highlands to centers of consumption. The organization of Maring trade must be understood by looking at trade in its regional rather than more narrow or local context.

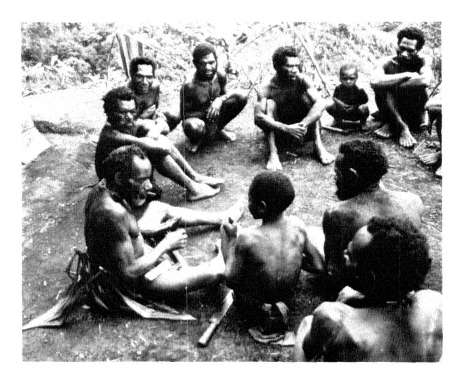

These broad ecological and cultural parameters are obvious dominating forces on the structure of trade networks. Nonetheless, a fuller understanding of trade also requires a detailed analysis of the ecological and sociocultural organization of trade at the local level. Typically, the Melanesian trader is only hazily aware of the shape, extent, and organization of the "systems" of networks within which he is located. His perspective is more parochial and ethnocentric, even egocentric. Yet ultimately, the regional systems we analyze are built up of the uncoordinated activities of individual producers, transactors, and consumers.

The objectives of this book are to provide an examination of the

local exploitation of forest products—as a particular form of production—and of patterns of exchange and consumption. I examine the articulation of such exploitation, distribution, and consumption with wider regional, economic, ecological, and historical processes. I do this by way of a quantitative and diachronic analysis of production and trade over a roughly sixty-year timeframe, tracing the relation of production and trade to other forms of exchange in Maring society.

Beyond all else the book is intended as an ethnography of a hitherto neglected aspect of production and exchange in Melanesia, taking as my focus the organization of hunting and trade among one community of the Maring speakers on the northern fringe of the Papua New Guinea highlands. This work, however, is also an attempt to combine some of the approaches of ecological and economic anthropology. In regard to the latter my sympathies lie with the substantivists in opposition to the formalists. Yet, as will become clear in the following pages, I consider that despite the substantivists' professed respect for the cultural order, wherein "economy" is treated as a category of culture rather than behavior or action, too often the substantivist economic anthropologist smuggles in materialist and utilitarian notions that fail to apprehend the fuller cultural significance of "economy." Substantivists and formalists alike tend to represent trade as a mundane, utilitarian, and practical activity. The general trend of my analysis is to outline the material conditions of production and exchange, moving on in later chapters to examine the embeddedness of trade in the wider social and cultural order to indicate—in an admittedly partial and preliminary way—something of the meaningful and experiential dimensions of trade to those involved.

This work is an outgrowth of a more limited study of the exploitation of birds of paradise which I took up soon after joining the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) in 1970. That project had been established in 1969 by Ralph Bulmer, then Professor of Anthropology at UPNG, and Max Downes, then Chief of the Wildlife Division of the PNG Department of Agriculture, Stock, and Fisheries. The aim was to help in framing a policy for the conservation of the birds that would be consistent with the objectives of wildlife management and the economic and cultural interests of rural people in continued hunting and trade of bird plumes.

My initiation into the mysteries of fieldwork came in 1971 with a very brief visit to the Kyaka Enga of the Baiyer Valley to collect material on trade in bird plumes, and two trips to the Jimi Valley in 1972

(totaling three months) in a survey of hunting of birds of paradise and trade in plumes, taking in settlements of Maring, Narak, and Kandawo speakers. This gentle introduction to fieldwork was of immense benefit; it helped in coping with the usual traumas of being thrown into a new and confusing social world, gave me experience of the practical problems entailed in establishing a fieldwork base, and allowed me to gain a preliminary familiarity with research techniques. Perhaps most importantly, my 1972 visits to the Jimi gave me the opportunity to survey the ethnography, geography, and ornithology of a large area of the valley and to choose a field site best suited for my more-embracing study of hunting and trade.

In November 1973 I returned to the Kundagai Maring settlement of Tsuwenkai for twelve months' fieldwork. The central focus of my research was again on the exploitation of birds of paradise, but the study was broadened to locate hunting of birds and trade in plumes in the wider contexts of the production and exchange of valuables. This study formed part of a three-pronged research program by the Papua New Guinea Wildlife Division for the conservation of birds of paradise. This program consisted of the collection of basic data on bird biology and ecology by officers of the Wildlife Division, an examination of legal aspects of regulating hunting and trade in plumes, and the collection of ethnographic data on the use and significance of birds of paradise to rural people. As a postgraduate student at UPNG, I undertook the last task on behalf of the Wildlife Division. I wish to acknowledge my gratitude for the official support of my project by the Department of Agriculture, Stock, and Fisheries. (Subsequently the Wildlife Division was moved to a series of departments.)

This book is based on my Ph.D. dissertation submitted in 1977 to UPNG. In the intervening years I have had the opportunity to reflect on the earlier work and to return to the field for short periods in late 1978 and again in 1985. I have substantially rewritten the text for this book, although my analysis remains essentially the same. The work of revision mainly took the form of condensing the material, excising several chapters (which have been published separately), refining certain arguments, and incorporating data on change from my later field trips. The "ethnographic present" relates to the early 1970s, on the eve of Independence from Australian administration.

The book is not simply an ethnography of a "traditional past" but includes certain recent transformations. Nonetheless, even into the 1980s change in Tsuwenkai has been slight. The greatest changes have

stemmed from the political encapsulation of the village into the nationstate, with some attendant modification of internal village politics (see Maclean 1984b for a detailed and perceptive account). These new alignments, however, have not engendered any major alterations in the organization of production and exchange which forms the major orientation of this book. This situation may not last long. The very heart of Tsuwenkai is under threat—its soil and rocks and forests—and with it the social and cultural fabric. Mineral exploration has revealed potentially very valuable deposits of gold and other minerals in Tsuwenkai and nearby areas.

Faced with the possibility of large-scale mining development, many Kundagai are filled with alarm for the future of their children in a radically altered social and physical environment. Whatever the outcome, I can only hope that those Kundagai who may read this account will find it an acceptable view of their world as perceived by a foreigner—one mindful of the great honor done him by the generosity of their hospitality and companionship.

I began my studies at UPNG under the late Ralph Bulmer, and to him I owe my greatest intellectual debt, for guiding my entree into the field and for helping define my research problem. He commented generously and profusely on drafts of my dissertation and otherwise gave me the benefit of his wide scholarship in all matters of Melanesian ethnography and ornithology. I am also indebted to Andrew Strathern, who acted as supervisor in my studies and offered much-needed encouragement and advice in the field, and who steered the preparation of the dissertation on which this book is based to a successful conclusion.

Many others have contributed to the writing of this book. In particular I wish to thank Roy Rappaport for his comments and suggestions, Bill Clarke for ethnographic discussions and botanical information in the field, and an anonymous reader for the Press who made numerous valuable suggestions that have improved the final text. To Fitz Poole, an editor of this series, I owe thanks for his patience and counsel while the manuscript was under consideration with the Press. I have gained many ethnographic and analytic insights from discussions with Neil Maclean who has worked among the Tugumenga Maring. More generally, I have benefited enormously from the stimulus of friends and former colleagues at the University of Adelaide, especially Tom Ernst, Bruce Kapferer, Deane Fergie, and Neil Maclean, and from Jane Goodale who spent a year and a half in Darwin.

Three months' fieldwork in 1972 was supported by the University

of Papua New Guinea. My 1973-1974 fieldwork was partly funded by grants from the New York Zoological Society,. the Myer Foundation, and the then PNG Department of Natural Resources. In late 1978 I returned to the field for one month, while a grant from the Wenner—Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research enabled me to conduct a further two months' fieldwork in May-July 1985. I thank all these institutions for their support, and the national government and the Western Highlands Provincial government for permission to undertake research. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge the help offered by my parents and parents-in-law.

For hospitality and logistical support in the field I am grateful to Rev. Peter and Mrs. June Etterley, Rev. Brian Bailey, and the staff of Saint John's Church, Koinambe, and the staff of Tabibuga and Simbai government stations. Mr..(now Rev.) Alban Berobero helped me settle in at Tsuwenkai. Thanks are also due to Sue Plavins for typing the manuscript and the support of the Northern Territory University in preparing the manuscript for publication.

It is a convention at this point to acknowledge one's debt to the companion who has shared the burdens and pleasures of fieldwork, and who has put up with one in the process of distilling order out of the chaos of fieldnotes; but I have been asked to forgo such gratuitous gestures. As for my two daughters, they unwittingly delayed the writing of this book by exercising their right to attention, but in the process they helped keep me human. The resulting manuscript is perhaps better than it might have been otherwise.

Finally, I must acknowledge my debt to the Kundagai. My wife and I first came to Tsuwenkai unbidden and unexpected for a brief visit in 1972. We were invited back, yet the continuing warmth and generosity of our hosts surpassed our expectations. The memory we shall cherish but can hardly repay. To everyone in Tsuwenkai I must offer thanks for their hospitality, companionship, and friendship, no less than for their willingness to impart information to an often obtuse student. In particular, I acknowledge my gratitude to the late Kar and Planc who helped me understand the past, to Councillor Menek for his wise advice and support, and to Philip Amang for his help around the homestead and in the collection of data. Matthew Deimang Kuk cheerfully left his home up-river in Kwiop to join me as an assistant and give me the benefit of his talents as an interpreter. Bernard Kwie was a fount of information, advice, and support during my most recent fieldwork. And

last, I must record my profound gratitude to Lucien Yekwai for the special gifts of his knowledge, wit, and friendship.

Ralph Bulmer's untimely death in 1988 was a great loss to his many friends in Papua New Guinea and elsewhere, and to Melanesian studies. This book owes immeasurably to his inspiration, example, and guidance, and is dedicated to his memory.

A Note on Conventions

There is no standard orthography to represent Mating speech, and each ethnographer has tended to develop his or her own system. This variability partly reflects dialect differences: Maring put some importance on sometimes minor variations in pronunciation and vocabulary in different dialects. The orthography I have chosen is only broadly phonetic; I have tried to render Maring words readable rather than indicate precisely how they sound. Letters used have the same values as in Tok Pisin (Neo-Melanesian Pidgin), with the exception that the letter c indicates the ch sound in English "church." The letters ng sound as in "sing" and ngg as in "finger." The greatest liberty I have taken is with the use of the schwa, the short, unrounded vowel as in the first vowel of the British pronunciation of "banana," for which no romanized symbol suffices. In some words I have simply omitted this vowel, as in ambra ("woman") where it occurs between b and r; in others I have rendered it with a vowel that most closely approximates its sound in context, as in both vowels of the personal name Menek , or the last vowel of yimunt ("tree fern").

Tok Pisin words and phrases are indicated by the letters TP in parentheses.

Bird and other animal names present some problem. There are few standardized English vernacular names, and many are cumbersome (e.g., Yellow-billed Mountain Lory). Scientific names may be more acceptable to specialists but are even less comprehensible to the general

reader (e.g., the parrot just mentioned is known to ornithologists as Neopsittacus muschenbroekii ). Although I feel that precise identifications are important, I mostly refer to birds (and some other animals) by English vernaculars, the more cumbersome ones sometimes shortened. Precise identifications are listed in appendix 2.

The Maring have known three currencies: Australian pounds (to 1965) and dollars, and national Kina (K) since Independence in 1975. All monetary values are expressed in Kina (though most valuations occurred before 1975), with no adjustment for revaluations, at the rate of 10 shillings to $A1 to K1. There are 100 Toea to the Kina. The Kina was at parity with the Australian dollar, though revaluations now place it at about $A1.50. To avoid confusion with the marine shell known in Tok Pisin by the same name (and after which the currency is named), the shell (also known as pearlshell) is referred to with a lower case "k," the currency with a capital "K."

Introduction

The island of New Guinea nudges the equator at its western extremity. Yet between the steamy coastal plains the land is compressed and heaped up into a series of high ranges and temperate valleys. On the northern and southern fringes of the highlands in particular, the topography is heavily dissected. Here it is possible for the traveler to move within a day's march through several resource zones spanning many hundreds, even thousands, of meters from major valley floors to the mountain peaks. Such close-packed environmental differences are paralleled by cultural diversity.

Despite their sometimes forbidding habitats, no New Guinea societies were ever truly isolated. Exchanges of goods and people across cultural boundaries assumed great importance in many areas. This natural and cultural diversity encouraged considerable traffic in material objects, and studies have clearly shown that trade is most highly developed between communities of differing ecological or cultural regions with specialized natural or manufactured resources. It is such locally specialized products that provide the bulk of goods traded across regional divisions (Gewertz 1983; Harding 1967; Hughes 1977; Keil 1974; Schwartz 1963; Tueting 1935). This book is concerned with the social, cultural, and ecological dimensions of the production of valuables and trade among the Maring people on the northern fringe of the central highlands of Papua New Guinea.

Trade is but one aspect of regional and intergroup relations and

must be understood in the context of other kinds of dealings, such as marriage, warfare, ceremonial exchange, and their political-economic dimensions. But trade is also bound up with humankind's interaction with the environment—the economics and ecology of production or exploitation, by which the supply of trade goods is affected, as well as the distribution and consumption of goods whereby continued demand is generated.

Although there are numerous studies of intergroup relations throughout the New Guinea region, systematic attention to trade has concentrated on the lowlands and islands. Numerous ethnographies of the highlands make passing reference to trade. The only substantial treatments are by Hughes (1973; 1977) for a large area of the highlands and foothills, and Keil (1974) for the Benabena region of the Eastern Highlands. Other briefer descriptions and analyses of note include those provided by Rappaport (1968) for the Maring, Strathern (1971) for the Melpa, Heider (1970) for the Dani, Kelly (1977) for the Etoro, Reay (1959) for the Kuma, and Godelier (1977; 1986) for the Baruya.

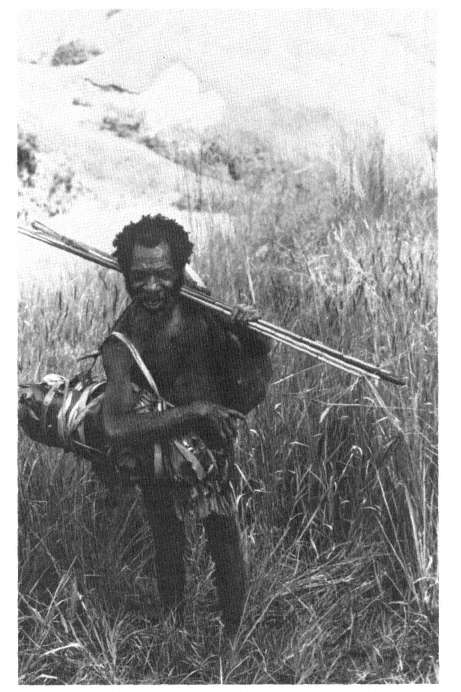

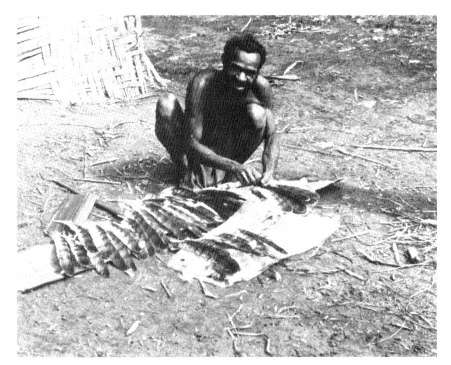

Highland trade can be characterized by a constellation of features: traditionally a virtual absence of any form of organization approaching markets (but cf. Keil 1977) and a general lack of communal or cooperative activities beyond expeditions of men traveling for companionship and protection; the short distances individual traders travel; the passage of goods in small consignments, generally in one-for-one exchanges; the overwhelming concentration of trade in the hands of men; and the general restriction of goods to valuables or luxuries other than food. Even within these limits on goods, the range of items is quite astonishing, though highly variable from one region to another. In aboriginal times trade goods included stone axes, a variety of marine shells, salts, live animals (notably pigs and cassowaries, but also dogs, fowls, and marsupials), plumes of numerous species of birds, furs and skins of several marsupials, animal-tooth and vegetable-bead necklaces, cosmetic tree oil and pandanus oil, tobacco, pigments, medicinal and magical earths, weapons, drums, string bags, kilts, bark capes, bone daggers, fiber belts and armbands, besides other handicrafts. Luxury foods were seldom distributed in trade, and staple foods never. With the exception of pigs, the great bulk of high-value goods were produced exclusively by men and were generally for the use of men in ceremonial gifts, decorations, or ritual observances.

The organization of trade and the range of items traded is, perhaps, more varied in lowland and island New Guinea. The most obvious contrast with the highlands are the great maritime trading systems of the north coast (Barlow 1985; Hogbin 1951; Lipset 1985; Tiesler 1969), Admiralties (Schwartz 1963), Vitiaz Strait (Harding 1967), Massim (Belshaw 1955; MacIntyre and Young 1982; Malinowski 1922; Seligman 1910), south coast of Papua (Dutton 1982; Malinowski 1915), and the Fly-Torres Strait region (Landtman 1927). Some of these systems, notably the Vitiaz Strait, involve specialist middlemen traders. Trade importantly depends on cooperation between groups of individuals, not least because of the technical requirements of sailing. Besides a great variety of valuables similar to those traded in the highlands, numerous luxury and everyday items of manufacture were traditionally traded in lowland and island New Guinea. Importantly, luxury and staple foods were, and still are, commonly traded.

Where trade systems were dominated by high volumes and frequent consignments of staple foods, rather than other goods, markets were significant institutions, and the bulk of transactions were conducted by women. The lower and middle Sepik and the Tolai area of New Britain are examples of such female-dominated, subsistence-food-oriented traditional markets (Barlow 1985; Epstein 1968; Gewertz 1983; Salisbury 1970).

Although trade has been a neglected field of study in the highlands, a great deal of attention has been focused on systems of the distribution of great volumes of valuables—primarily pigs and shells—in ceremonial exchange (e.g., Bulmer 1960; Feil 1984; 1987; Josephides 1985; Lederman 1986; Meggitt 1974; Sillitoe 1979; Strathern 1971). In some regions ceremonial exchange may indeed have developed at the expense of trade, or by the transformation of trading relations (cf. Healey 1978a ), but I suspect that highland trade has attracted so little attention not because it is of limited material significance, but because in comparison to ceremonial exchange it appears so utterly mundane. And whereas the analysis of the exchange of valuables continues to concentrate on its more dramatic and ceremonialized forms (e.g. Lederman 1986), the study of production has concentrated on subsistence foods rather than valuables. The pig, of course, is a paramount valuable that has figured prominently in analyses of production, if only because it is largely nurtured on garden produce. There are, nonetheless, massive amounts of other objects variously known as valuables,

wealth objects, and prestige goods which require considerable labor to produce, are consumed in very different ways from subsistence items, and which are redistributed in prestations and trade.

This work examines the interconnection between the ecology of the production of valuables through the exploitation of nonsubsistence goods and the social and cultural organization of production and exchange. An important focus is the dynamic operation of production and trade through time. Although synchronic studies illuminate the functions of trade (or other activities) in effecting the distribution of specialized goods between ecologically and culturally distinct provinces, they do not allow us to test for the temporal stability or otherwise of trade systems. Equilibrium in functional models, ecological and anthropological, does not imply constancy but a dynamic balance of forces (Kormondy 1969; Rappaport 1979). Simply because a system has been identified does not presuppose that it is in equilibrium. The capacity of a trade system to achieve a degree of permanence and stability through the balance of supply and consumption depends not only on the proportions of different goods in circulation but also on the ecology of initial production. Where trade goods are derived from plants or animals, the ability of those producing or extracting the goods to maintain supply becomes theoretically infinite; the raw materials are self-perpetuating. The demand of populations desiring these goods sets a base level or rate at or above which these goods must be supplied, whereas the capacity of the animals or plants to reproduce sets an upper limit on supply. If the producers or exploiters attempt to inject more of these goods into the trade system than natural regeneration can replace, then the system must at best be interrrupted and at worst be destroyed with the extinction of the resources if substitutes cannot be found.

Products of animal and vegetable origin, such as bird plumes, marsupial pelts, bows and arrows, tree oil, and net bags, are still highly desired and traded in many parts of the highlands. It is therefore still possible to study the ecological bases of production—to discover the mechanisms whereby demand can be met and balanced within the limitations of supply set by the capacities of the raw materials to reproduce themselves. It is also possible to explore the social and cultural forces that, in conjunction with ecological factors, give a trade system its distinctive geographic shape, modes of operation, and historical dynamics.

Trade as an Analytic Category

At this point some indication of what I mean by trade is essential. There are two prevailing uses of the term in anthropology: it is applied loosely and generally to refer to any passage of goods by a variety of means, and it is applied in a more limited sense as a category distinct from ceremonial or gift exchange or prestation. Indeed, some ethnographies and undergraduate texts even set trade apart from exchange—referring to "trade and exchange"—which is at once an unfortunate imprecision, for what is really meant is "ceremonial exchange," and an absurdity, for trade is obviously one form of exchange.

Theoretical and ethnographic understandings of ceremonial exchange, gift exchange, or prestation have achieved a degree of elaboration and sophistication. Trade, barter, or commodity exchange have fared less well. In some ethnographies trade is implicitly everything that gift exchange is not. Those works that deal with trade explicitly commonly characterize it as being "more economic," "commercial," or less sociable than gift exchange; an activity engaged in by calculating, self-interested individuals out of crudely utilitarian and materialistic motives of private gain (see e.g., Tueting 1935; Podolefsky 1984). Trade thus hovers on the boundary between hostility and friendship and can be made a positive force of social (as distinct from regional) integration by inflecting the practice of trading in the direction of gift exchange through such acts of sociability as entering into formal partnerships with others, honoring trade partners with gifts or favored terms of trade, and the like (e.g., Sahlins 1972). This view may adequately characterize the practice of trade in some areas, but it may obscure as much as it reveals. Certainly, as the present ethnography will show, the presumption that trade is essentially grounded in utilitarian and materialistic forces is unacceptable as a generalization.

Anthropologists have long distinguished between ceremonial exchange and trade, following native practice. The most notable example for Melanesia is the Trobriand distinction between kula and gimwali (Malinowski 1922), but there are many similar instances. Sahlins (1972: 185 ff.) has developed a general framework for the discussion of exchange of material goods in his scheme of reciprocities. He identifies certain factors—kinship distance, rank, relative wealth or need, the types of goods transferred—which among others influence the na-

ture of reciprocity. His discussion of the continuum of forms from generalized through balanced to negative reciprocity points to the difficulties of separating one form of exchange from another for definitional purposes. This conclusion is important in that it derives from a consideration of the interplay of social forces acting on the parties to an exchange, rather than from a comparison of the observable character of different forms of exchange.

Some ethnographers, however, have attempted to distinguish trade from other forms of exchange on the basis of the outward or observable form of exchange, rather than on the basis of the relationship of the actors. Such definitions may consist of a list of characteristics demarcating trade from prestation (e.g., van Baal 1975; Hughes 1977). Such definitions are inadequate because they refer to the actual conduct of the transaction by which goods are exchanged—the nature of the objects, the relationships of those involved, the relative amounts of ceremonialism, publicity, corporation, magic, or politics involved during the exchange. In societies where economic activities, ceremony, politics, and so forth are not sharply demarcated but are infused in many institutions and situations, this kind of definitional view of trade and prestation necessarily overlaps. Using this approach it is not always easy to classify a material transaction observed in the field. An unceremonial, private, delayed exchange of dissimilar goods of equal value between affines combines descriptive attributes of both trade and gift. Although what is normally understood as trade, barter, or commodity exchange falls within the categories of balanced or negative reciprocity in Sahlins's scheme, his approach to the question of definitions offers no clear way out of the problem. But it does provide a useful theoretical model for a consideration of the structural and economic implications of different substantive forms of exchange. Nonetheless, I argue that if we are to gain a proper understanding of production, distribution, and consumption of goods in sociological terms, a distinction between fundamental forms or modes of exchange must be made. In nonmarket exchange (cf. Polanyi 1968) there are two such modes, which I term trade and prestation. I use the latter term in a general sense, derived from Mauss (1954), to include a diversity of reciprocal gifts transacted by individuals or collectivities on specific formal occasions, such as moments in an individual's life cycle, as well as informal occasions when gifts are not normatively prescribed. For the moment, I take refuge in a particular ethnographic understanding—that of the Maring

who are the subject of this book. The Maring term munggoi rigima (literally "valuables exchange"), which I translate as trade, refers to transactions explicitly concerned with the acquisition and distribution of goods whereas munggoi awom (literally "valuables give"), or prestations, refers to transactions explicitly concerned with the establishment, continuation, or discharge of social relations, rights, and obligations. Trade is thus overtly concerned with relations between material objects mediated by social relations, and prestations, with relations between people mediated by material goods. (The Maring concepts are examined more fully in chap. 4.) This distinction is fundamental to what follows, though it would be naive to expect it to be recognized explicitly in all precapitalist societies. Boldly stated, it has clear applicability to different forms of exchange elsewhere but is hardly profound. The rest of this book, however, amounts, among other things, to an elaboration and explication of the nature and significance of this distinction. In the final chapter I arrive at some important modifications of this definition of trade which soften the rigidity of the present position.

A Model of Trade

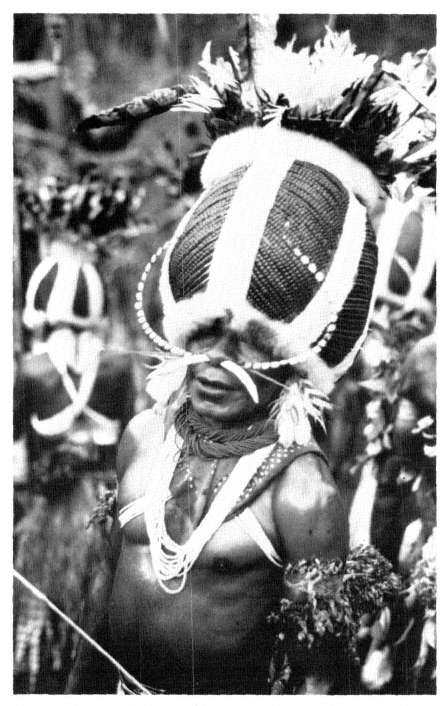

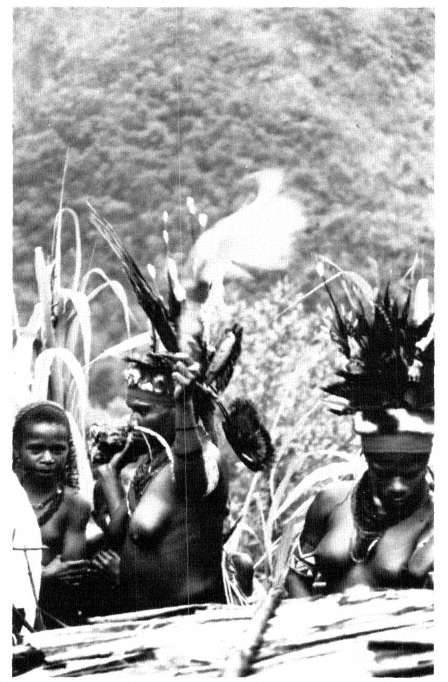

A striking feature of central-highlands societies is the richness of their ceremonial decorations (see Strathern and Strathern 1971). The most impressive element is often a headdress of bird of paradise plumes, parrot skins, and eagle, hornbill, and other feathers. Plumes are not only highly prized as items of visual splendor but are wealth objects redistributed in bridewealth and other prestations. It is in a relatively limited area of the central highlands—the Simbu and eastern Wahgi Valleys—that plume use is most highly developed in terms of the quantities and varieties desired. Because of extensive deforestation, many densely settled communities lack access to what forest remains in narrow belts above the level of agriculture (about 2,200 meters). Since the majority of bird species most highly valued for their plumes live either in high-altitude forest or in lower altitudes on the northern and southern highland fringes, the central highlanders are unable to satisfy their own requirement for plumes from their own forests and must obtain the bulk of feathers from communities on the fringes with easy access to wild birds. In the latter areas population densities are generally lower and extensive forests support a rich and diverse fauna,

including birds of paradise, parrots and hawks, marsupials, and other forest products.[1]

These conditions set the parameters for an analysis of trade that takes as its focus the provision of one class of goods: forest products, most especially bird plumes. Simply stated the model is a center-periphery one consisting of a trading network of plumes and their exchange goods made up of concentric rings arranged around a core of communities I call ultimate consumers of plumes. Feathers, mammal skins, live cassowaries, and other such products of the forest are traded toward this central area where they remain until worn out or destroyed. They may be redistributed in trade or prestation but not exported beyond the center. At the extremities of the model are located numerous primary suppliers of plumes and skins who obtain all of their stocks for local use and trade by hunting. Intervening areas are occupied by intermediate suppliers who receive plumes in trade from the periphery and augment the volume sent on to ultimate consumers by adding more feathers by local hunting. Such communities may also be intermediate consumers to a greater or lesser degree and are therefore critical for the volume of plumes delivered to the central consumption area.

This scheme clearly involves two "systems" of exchange that are only partially connected. One involves the socially and culturally mediated passage of dissimilar goods in opposing flows—the organization of trade. The relative kinds, quantities, and values of different categories of goods and the demand for them may vary through time and from one sector of the trade sphere to another, so engendering a degree of internal tension that may be necessary for the continued functioning and survival of trade as a means of supply. The second system involves the ecological relationship between human communities and the wild populations of birds and other resources on which they prey to sustain their position in the trade network.

The overall structure of trade is articulated in terms of patterns of distribution of plumes. Their supply is thus critical, and ultimately the number of plumes available for trade—and so the volume of exchange goods in passage—rests on the recruitment rate in wild-bird populations. To maintain trade humans must not reduce bird populations below certain critical levels by destruction of habitat or by predation rates that exceed recruitment rates. This scheme does not necessarily imply homeostasis in the system of exploitation and trade, but it does require that the birds are not eradicated without compensatory shifts

to new supply areas. This means that in particular locations birds may be subjected to extreme under- or overexploitation provided that the volume of plumes delivered to ultimate consumers remains much the same. The model does not therefore involve any necessary stable or dynamic equilibrium between human activity and bird populations, either overall or in particular locations. It is possible, then, for some suppliers to pass out of the trade network entirely by destroying their resource base, since there are no negative feedback loops connecting goods received in exchange for plumes (from consumers) with the subsystem of plume production that rests on the breeding biology of birds.

From this concentric structure of networks it follows that the products of a multiplicity of primary suppliers become fed into progressively fewer or more densely packed channels. Loss rates of plumes from damage and age may vary in different parts of the network, but all things being equal this funneling effect results in the delivery of massive quantities of plumes to the center, even though the contribution of individual supply communities might be quite small.

The dynamics of this scheme can be elaborated considerably.[2] For the moment, the point to stress is that the model provides a focus for the detailed analysis of specific ethnographic data on trade. From an initial concentration on the production of one class of valuables for use in trade, one can expand the analysis to encompass the wider social, cultural, and ecological context within which that production occurs.

Elsewhere I have documented the trade in bird plumes in the New Guinea region and shown that the pattern of distribution in the interior—roughly encompassing the Papua New Guinea highlands—conforms broadly to the geographic structure of the model sketched above (Healey 1980). The purpose of the present work is to examine the organization of production and exchange at the level of the local community. In that respect it differs from most other studies of trade that take a regional perspective. I seek to show how local production and exchange are articulated in sociocultural and ecological dimensions with wider regional forces.

This book, then, explores, through the example of the Kundagai Maring, how goods enter, move in, and leave the larger sphere. In the absence of markets or centralized organization, trade networks of the kind dealt with here are always managed at the local level, and ultimately by individuals who may be quite unaware of their economic and ecological role in the region as a whole. What sustains production and trade at the local level cannot, therefore, be accounted for by reference

to the larger structure. That structure is the consequence of the interconnections of local producers and transactors, not the determinant of their activities.

A further caution must be added. The scheme just outlined treats plumes as the products of ecologically specialized peripheral regions. For consumers to signal effectively a demand for plumes they must offer in exchange goods that are desired by plume suppliers. In general, the exchange items are also specialized products unavailable locally to plume suppliers for ecological or cultural reasons. The goods in demand may vary from one area to another. Further, there is no necessity that ultimate plume consumers be primary suppliers of other goods. One may imagine several patterns of trade in a variety of goods superimposed on a landscape so that their boundaries overlap. Thus, the model is not one of a trade system as such, but of one category of goods passed in trade. Indeed, to speak of systems is to suggest that there are boundaries of a reasonably determinate nature. Empirically it may be possible to demarcate the patterns of distribution of material goods, but the degree of noncongruence in these geographic patterns, added to the variable sociological means of distribution, make it impossible to define trade systems. There are no isolated, impervious trade systems in operation in Melanesia, if anywhere. It is clear, nonetheless, that there are areas where there is a concentration of most exchanges within certain geographic and sociological limits, and I shall refer to them as trade regions.

This book deals with the operation of a segment of one such region, which is indeterminate in extent but centered on the major highland valleys. Hughes (1977) has ably described the ecological structure of the region on the eve of the colonial era. The segment in question consists of a number of communities on the rugged northern fringe of the highlands, whose place in the wider trade region is assured by virtue of their privileged place as one of the major supply areas of various forest products in trade directed toward ultimate plume consumers. The particular focus is on the Kundagai of Tsuwenkai, a group of some three hundred Maring speakers.

Much of what follows amounts to the construction of a more elaborate model of trade in terms of ethnographic and ethnohistorical evidence. The picture just outlined is one couched largely in ecological and functional terms. It is important, however, to avoid allowing such formulations to dominate the process of producing an ethnography—both

in the field situation and, more importantly, in the final presentation and analysis of data.[3] It is well, then, to state the general perspectives adopted. The model is essentially one of equilibrium. This study, however, does not assume homeostasis as a necessary tendency of the complex of transactions examined. I am concerned to discover the capacity for trade to be sustained, but this does not involve any presumption of steady states. Besides, even to discover an equilibrium is not to show that it is systematically achieved.

Second, although production and exchange occur in particular ecological contexts, I accept that all activity is crucially shaped by cultural factors. Ecological conditions, therefore, cannot be determinants of individual or collective repetitive action, nor of features of culture. Finally—and flowing from this attention to the cultural order—the analysis rejects formalism in the explanation of exchange, most especially its common appearance in ideas of material utility.

The following two chapters set the context for an examination of hunting and trade. Chapter 1 outlines critical features of the Kundagai physical environment and aspects of social organization. Such data are obviously necessary for a fuller understanding of the social and cultural organization of production and exchange. Chapter 1 also outlines Maring concepts of spirits and their place in the natural world within which hunting occurs. Finally, I provide a discussion of the historical dimensions of settlement of the Kundagai village of Tsuwenkai and of transfers of rights to land, events that clearly have contributed to the contemporary social and geographic patterns of exploitation of the environment.

In chapter 2 I seek to show the cultural significance of bird plumes among the Maring as objects of decoration. The uses of plumes and other forest products are a significant but not sole impetus to local production. An important point that emerges from this chapter, moreover, is that many kinds of feathers retained for decorations are not available locally but must be obtained from elsewhere. Just how this is organized is the focus of later chapters.

Ecologically focused studies of production in agricultural societies have, understandably, concentrated on subsistence foodstuffs. Little systematic attention has been paid to either the production of nonsubsistence valuables, on the one hand, or to the exploitation of non-domesticated resources, on the other hand. Marks's (1976) study of big-game hunting among the central-African Bisa is a rare exception.

Chapter 3 takes up these issues and provides an examination of the ecology of hunting of birds for their valuable plumes and the social and cultural organization and regulation of hunting.

The remainder of the book is concerned with the ecology and sociocultural organization of aspects of the distribution and consumption of material objects. In particular, I seek to show how levels of production and exchange of one class of goods—forest products—relates to the total flow of goods by a variety of means. This involves specifying the kinds of goods, material and otherwise, that are transferred parallel to or in opposition to forest products, their patterns of ownership, and the kinds of transactions in which they are passed. Chapter 4 introduces this analysis, presenting data on valuables, their ownership, and their redistribution in prestations. An important aspect of this chapter is the analysis of gross levels and directions of passage of goods in prestations.

The following chapters are devoted to the analysis of trade. Chapter 5 provides an ecologically oriented description of trading patterns over time and an analysis of mechanisms for the maintenance of a more or less constant passage of goods in the absence of any regulatory institutions. Chapter 6 provides an overview of the historical dimensions of trade, pointing to the importance of European penetration of the central highlands for the consolidation of changing trade patterns in the northern fringe of the highlands and the significance of plume trade in the contemporary cash economy. In chapter 7, I develop an analysis of exchange value and suggest the mechanisms by which rates of exchange of some trade goods remain stable while others have changed.

The concluding chapter shifts the focus from the relationship between objects passed against one another, which characterizes the preceding chapters, and concentrates on the social relationships between the traders themselves. Through a discussion of the manner in which trade may be employed as a communicative means expressive and constitutive of social relationships, I argue that prevailing utilitarian understandings of trade require some reappraisal.

The general objectives of this study are twofold. Substantively, this work provides an added dimension to the ethnography of the Maring and of hunting and trade in the highlands in general. Theoretically, the book is an attempt to develop a more thorough understanding of the articulation of production and exchange, combining the insights of ecological and economic anthropology.

1

The Kundagai

Environment and Society

The Western Bismarck and Schrader Mountains form the last bastion of the central highlands before the land falls away to the humid lowlands of the Ramu floodplain. Several cultural groups inhabit these northern fringes: the Maring, Narak, and Kandawo whose affinities are close to Wahgi Valley central highlanders, and the Kopon, Kalam, and Gainj comprising a language family only distantly related to the main highlands stock (see map 1).

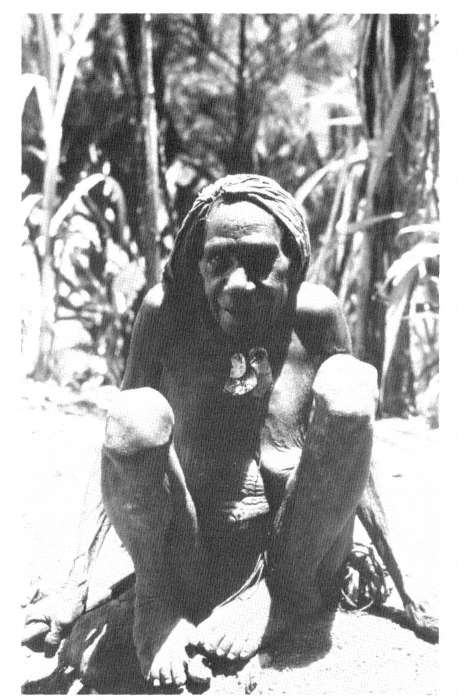

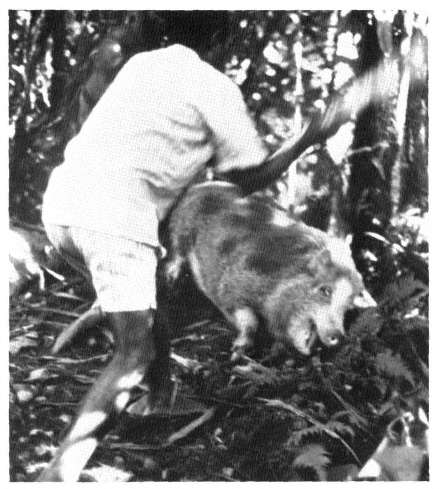

Like their fellow highlanders the Maring are swidden agriculturalists and pig-raisers. The staple diet is provided by sweet potato and taro, but a great variety of other crops is grown. Some have always been present, others have been introduced from their neighbors over the last hundred years or more. The list includes yams, cassava, bananas, sugar cane, pitpit, corn, and cucurbits, besides numerous leafy greens and tree crops, notably the fruit pandanus and breadfruit. In addition to pigs, which are seldom eaten outside of irregular ritual and ceremonial occasions, the Maring keep a few fowls, dogs, and cassowaries. Many local groups enjoy a higher intake of meat than one might otherwise suppose, however, for game is plentiful in some areas. Nonetheless, exploitation of wild resources is not solely geared toward satisfying gustatory desires, for the forests abound in a great variety of birds and mammals whose feathers and pelts are eagerly sought by those less favorably endowed.

The Kundagai are one such community who engage in considerable

Map 1.

Jimi Valley

hunting to supply trade goods. They are one of more than twenty Maring local populations and occupy a large territory stretching between the Jimi and Simbai Rivers. They live in three settlements: Bokapai and Tsuwenkai in the Jimi Valley, and Kinimbong in the Simbai. I am concerned mainly with the people of Tsuwenkai (map 2), and unless stated otherwise I mean the name Kundagai to refer to that section of the population living there.

This chapter describes the environmental and ethnographic context for the subsequent account of hunting and trade. I begin with attention to aspects of the natural environment, with some general notes on the impact of human occupation. There follows an account of critical aspects of Kundagai social organization. I conclude with a summary of settlement history with particular attention to land tenure.

The Physical Enviroment

The government rest house of Tsuwenkai lies at about 5º25' S, 144º38' E, at an altitude of 1,680 meters. The settlement is in the headwaters of the Pint River, a tributary of the Jimi. The Jimi Valley comprises the Tabibuga District of the Western Highlands Province and is administered from Tabibuga on the Tsau-Jimi Divide. Until the early 1970s, when a road suitable for four-wheel drive vehicles was completed from Tabibuga to Banz in the Wahgi Valley, the only means of contact within and beyond the Jimi was by walking tracks or light aircraft. By the mid-1980s the Kundagai and others had invested around twenty years' of manual labor into building a road connecting settlements on the north bank of the Jimi to Tabibuga. Although the Jimi River was bridged in 1978, the road was still not passable in 1985 to traffic beyond a few kilometers from the bridgehead. Long, well-graded, but unconnected sections of road were continually reclaimed by secondary growth or swept away in landslides. The labor involved in roadbuilding and maintenance was compounded by repeated rerouting of extensive sections of the road.

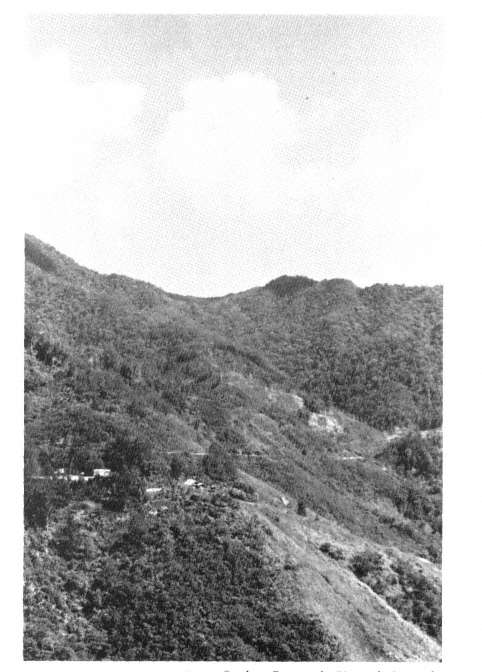

The north wall of the Jimi Valley is formed by a western extension of the Bismarck Range. The valley is separated from the densely populated Wahgi Valley to the south by the Sepik-Wahgi Divide that rises to over 3,700 meters in places. These two ranges converge in jagged, cloud-piled ridges on the central massif of Mount Wilhelm. On clear days this highest peak in Papua New Guinea is visible from Tsuwenkai some 60 kilometers to the southeast, rendered a mere hummock by the

Map 2.

Tsuwenkai Vegetation and Settlement

closer, more dramatic ranges. The Jimi is a turbulent, rock-strewn river that rises on the snow-fed slopes of Mount Wilhelm and plunges down its narrow, cliff-hung bed on its way to the Sepik River to the northwest. To the north of the Bismarck Range the Simbai River flows eastward and then north to join the Ramu River.

I made no detailed records of climate during fieldwork other than noting temperatures for 204 days over 12 months in 1973-1974. Clarke (1971: 39-50) and Rappaport (1968: 32-33) give details of rainfall at Gunts, Tsembaga, and Simbai Patrol Post in the Simbai, and at Tabibuga in the Jimi. On comparative grounds the annual rainfall at Tsuwenkai is probably between 3,000 and 4,000 millimeters.

During the wetter season, about November to April, rain falls almost every afternoon, and mountain peaks are often obscured by cloud for much of the day. In the late afternoon heavy banks of cloud well up in the Simbai to spill over into the Jimi, and the evening is often enlivened by the ominous roll of distant thunder and the flicker of lightning from the Ramu lowlands. The dank and miserable reputation those regions enjoyed among my Kundagai friends seemed well deserved.

In the drier season, May to October, the sky is often cloudless and no rain may fall for periods of up to a week. Occasionally the dry season does not become properly established, or is shorter than usual, and so hampers garden preparations as gardeners wait for fine weather. Under these circumstances a gardener may be unable to clear as much land as desired or to achieve an adequate burn of trash. Such times create anxiety over food shortages, although the Kundagai mainly suffer hunger for favored crops rather than any serious absolute shortage of food. Heavy afternoon rains sometimes cause minor flooding of streams, small landslides beside tracks, some sheet erosion in gardens with sparse vegetation cover, and damage to sugar crops flattened in the downpour. Although excessive rain periodically causes problems, the Jimi does not appear to be significantly affected by drought, although many smaller streams dry up toward the end of the drier season.

Daily maximum temperatures varied during fieldwork from 16.5º C in June to 29º C in October, averaging 22.8º C. Minima were usually reached around six A.M. and ranged from 11º C to 18º C (both records in November), averaging 14.9º C. I do not know if frosts ever occur; certainly the Jimi was not affected by the devastating frosts in higher

altitudes of the Western and Southern Highlands Provinces of 1972, which occurred while I was in the upper Jimi.

As elsewhere on the highland fringes the landscape is dramatic. The Jimi River flows along the northern part of the valley so that a cross-section of the valley is a lop-sided V shape, with a steep north wall and more gentle southern slopes. Especially on the north side the numerous watercourses are deeply incised, producing a rugged topography. Tsuwenkai itself is situated on the flanks of a range on the west of the Kant River, extending southward from the Bismarck crest. The Kant Valley is narrow, with short, steep lateral spurs and intervening streams. The Kant joins the Pint River south of Tsuwenkai. Aside from some tiny marshy patches by the river, there is no flat land in the Kant Valley and only a few gently sloping areas along the upper course of the Pint. Tsuwenkai territory ranges in altitude from about 1,200 meters to at least 2,800 meters in the short space of about six kilometers.

North of Tsuwenkai a low pass, Gendupa, allows fairly easy access across the Bismarcks to the Simbai Valley. A similar pass at Gachambo at the headwaters of the Kant connects with the Mieng drainage system. Another pass north of the Mieng gives access to Kumbruf in the Simbai.

The loose shales and clays of the Tsuwenkai region are prone to landslides, especially after the shallow soils are waterlogged with rain. Small slides are common on embankments beside tracks and gardens. Larger slides of one or more hectares in extent occur in both grasslands and primary forest.

Vegetation and Ecological Zones

The Tsuwenkai region totals about 25 square kilometers, excluding 1 to 1.5 square kilometers of high-altitude forest claimed by the Simbai Valley Tuguma (see below).

On the basis of vegetation and fauna, Tsuwenkai can be viewed as a montane region. The Kundagai of Tsuwenkai are probably the only Maring group to be confined exclusively to the montane zone, although they do have some access to lower areas at Kinimbong in the Simbai. The Tsuwenkai region can be divided into three ecological zones with characteristic vegetation types.

Montane Zone

This zone consists of primary montane forest[1] and extends down from the mountain peaks of over 2,800 meters to the forest edge at

about 1,700-1,850 meters. The Maring call such forest kamungga, apng geni , or apng geni mai . The last two terms refer to virgin forest. Kamungga is often used as a synonym for montane forest but may also refer to secondary growth. The connotations are generally wider than a vegetation type, including high altitudes, a cold and wet climate, and a characteristic fauna. The term, then, refers not only to a vegetation type but to a particular ecological zone.

Clarke (1971:207 ff.) and Rappaport (1968: 271 ff.) give details of the floristic composition of montane forest. Characteristic of this zone are groves of tall Pandanus palms and huge cenda trees (unident.). Above about 2,400 meters are stands of kamai, Nothofagus Beech.[2]

The Kundagai say that in the recent past montane forest extended over most of the Tsuwenkai area right down to the Kant River. Much of this in the lower altitudes was apparently oak forest of Castanopsis and Lithocarpus species. There are small stands of remnant oaks in the Kant Valley.

Montane forest has a more or less continuous canopy about 30 meters or more above the ground. Two, sometimes one, substages are generally present. The ground level is usually fairly clear, though where a dominant tree has fallen or trailing bamboo becomes established the undergrowth can be quite dense. Most trees are heavily laden with moss, especially above about 2,200 meters where trees become somewhat stunted.

The montane zone covers about sixteen square kilometers or 64 percent of the Tsuwenkai area.

Zone of Human Habitation

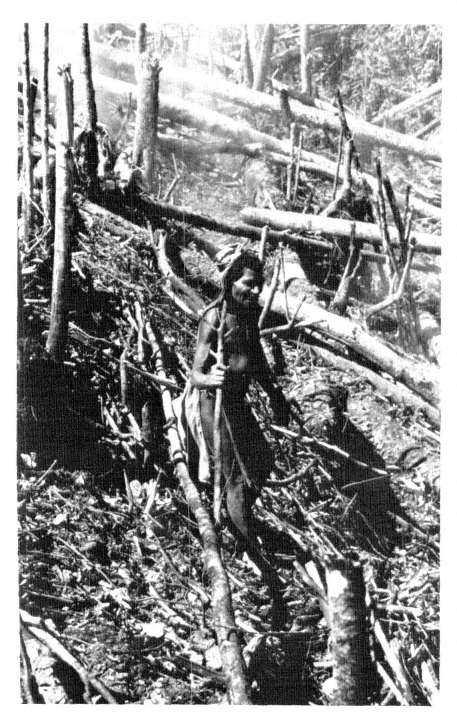

In Tsuwenkai most of the land below the montane zone falls into this category. This region presents a patchwork pattern of secondary forest in various stages of development, gardens, homesteads, and groves of planted trees. Tracts of anthropogenic grassland are interspersed within this area. The zone owes its origins almost entirely to the presence of humans, having developed where man has cut or burnt the original forest. Because of the diversity of vegetation it is convenient to distinguish several subzones.

Secondary Forest and Woodland . While recounting the oral history of Tsuwenkai, informants often made reference to former vegetation cover. From their remarks it appears that secondary forest transforms into forest classed by the Maring as apng geni mai after forty to seventy

years. [In the lower and wetter Ndwimba Basin of the Simbai regeneration is quicker (Clarke 1971: 61).]

The speed of development of secondary forest and woodland varies from one site to another but, on average, growth reaches a height of about nine meters in ten to fifteen years. The Kundagai attribute such variations to differences in soil fertility and the floristic composition of the fallow growth—no doubt interrelated factors. Moisture content of the soil probably also influences regeneration. Thus, relatively open-spaced communities dominated by the trees Trema orientalis, Dodonaea viscosa , and Alphitonia incana , shading a scrubby understory, tend to form woodlands on drier sites. In wetter areas secondary forest: is denser, supporting a greater variety of plants. Various Piper and Ficus species, and tree ferns, Cyathea , are common on such sites, as well as succulents such as wild ginger, Alpinia spp.

Bush Fallow . Lower growth is generally composed of dense stands of saplings pushing their way through a tangled layer of shrubs and bushes. On damp sites beds of pitpit (Miscanthus cane-grass) are common.

The distributions of secondary forest and woodlands and bush fallow are not differentiated on map 2 but comprise all areas not shown under primary forest, gardens, and grassland.

Homesteads and Plantations . These are areas dominated by vegetation actively induced by human activity. In contrast to gardens they tend to be semipermanent. There are around forty separate homestead or single-house sites scattered along the west flanks of the Kant Valley. Frequently a leveled space must be excavated into a hillside to provide room for a house. Settlement patterns are discussed below; here it need only be said that the Kundagai do not generally form any strong attachments to a particular homestead site, other than of convenience or sentiment. Once a house is beyond repair after two or more years' occupancy, the householder may rebuild nearby or more than a kilometer away. Moves are motivated by various factors: a desire to be close to new gardens, to friends or relatives, or to escape from unpleasant neighbors or sickness and witchcraft associated with a particular location.

Tobacco and bananas are often planted among the hearths and refuse of old house sites, and the yard may be planted extensively with casuarina trees. Once these reach a suitable height, coffee seedlings are

often planted in their shade. In this way old homesteads are transformed into relatively permanently altered areas. Sites that are totally abandoned generally revert to secondary forest, or occasionally to a disclimax of grass.

Groves of bananas, sugar, and green-leaved vegetables are usually planted within a homestead yard, along with shrubs and trees of an ornamental, utilitarian, or magical nature, such as casuarinas, tankets, crotons, bamboos, and various succulents and aromatic herbs.

Most coffee groves are established close to homesteads, in old kitchen gardens. Coffee requires a good shade cover, and casuarinas are favored for this purpose because they grow rapidly, yield superior timber for firewood, building, and fencing, and enrich the soil.

Groves of various other tree crops, especially the marita Pandanus, Pandanus conoideus , are scattered about in secondary growth or in homestead gardens. Few other propagated tree crops are grown in Tsuwenkai as they fare poorly at this altitude.

Included in this subzone are the raku[3] or ceremonial pig-killing groves and ossuaries. There are at least fifteen of these scattered throughout the zone of human habitation. Raku are generally small, less than about 0.2 hectares, although some are on the edge of primary forest or within secondary forest. Many raku are composed of remnant patches of montane forest, others are of secondary growth that has sprung up in the shade of casuarinas, Araucaria pines, and other trees planted by early Kundagai immigrants to Tsuwenkai. Raku are associated with particular clans, and the bones of the dead clansmen were formerly secreted in the ground or in tree hollows and epiphytic plants. Under government and mission influence the dead are now buried in graves, usually outside raku . The spirits of the dead are believed to linger about raku and, although one may gather firewood and creepers or resin from Araucaria pines from a raku , one should not cause undue disturbance lest the spirits visit sickness on the living.

The distribution of homesteads and isolated houses is shown in map 2. I have no estimate of the total area involved, nor of the area of groves of coffee or casuarinas and raku . These latter areas have not been distinguished on the map but are included within the type of vegetation surrounding them.

Secondary forest, bush fallow, homesteads, planted groves, and raku together cover about 6.3 square kilometers or 25.2 percent of the Tsuwenkai area. Spontaneous fallow growth constitutes the larger part of this area.

Gardens . The Maring practice swidden or slash-and-burn agriculture (see Clarke 1971; Manner 1977; Rappaport 1968; 1971, for details of agricultural practices and energetics). Each householder clears two or more gardens a year. Yields can be sustained from a little over one year to two years after planting depending on the crops planted. Sugar, bananas, and pitpit, Saccharum edule , can be harvested for the greatest length of time. The Kundagai generally plant their gardens only once and, although they are weeded periodically, much secondary growth has already sprung up among the crops by the time they are abandoned.

Map 2 shows gardens ranging in age from those just cleared in the dry season of 1974 to gardens about two years old. The total area under cultivation (excluding smaller homestead gardens that are not shown on the map) is less than 0.5 square kilometers. This constitutes no more than 2 percent of the total Tsuwenkai area or 8.3 percent of the area currently under a fallow of secondary forest, woodland, and bush.[4] There is a concentration of gardens on the southern slopes of Komongwai. This area is particularly favored because of the fertility of the soil, in consequence of which crops and fallow develop more rapidly than elsewhere, permitting more intensive cultivation under shorter fallow periods.

Gardens are cut at altitudes ranging from the Kant River (about 1,200 meters at lowest) to the edge of montane forest at about 1,850 meters. In the Simbai Valley, gardens are mainly cut between 900 meters and 1,520 meters, mostly below the lower limit of Tsuwenkai gardens. Rappaport (1968: 52) states that Tsembaga fallow periods are shorter in lower altitudes and, overall, average around fifteen to twenty-five years.

Tsuwenkai gardens do not appear to conform to this pattern, having shorter fallow periods despite higher altitude. Of a sample of twenty-nine gardens in preparation during 1973-1974, one was being cut in primary forest at about 1,720 meters. The remainder were in secondary forest. All these sites had been gardened at least once previously,[5] while one was being planted for the fourth time. According to the Kundagai, fallow periods vary in relation to soil fertility and floristic composition of regrowth, not altitude, although these factors are partially dependent on altitude. The type of crops to be grown also occasions some variation: sweet potato is considered to grow adequately on poorer soils or on land left fallow for shorter periods. The average fallow period for the twenty-eight gardens is fifteen to sixteen years (range six to

twenty-two years, mode twelve years, eight cases). A sample of a further twenty-six newly prepared gardens in 1978 yielded the same average and modal figures (range ten to twenty-six years). In 1985 a sample of thirty-two new gardens indicated a slight lengthening of fallow cycles. Three gardens were being prepared in primary forest; the average fallow period for the remaining twenty-nine gardens was eighteen to nineteen years (range nine to thirty-five years with a bimodal distribution of ten to eleven years, six cases, and sixteen to seventeen years, five cases). This shorter fallow cycle than Simbai regimes may reflect a slightly higher recovery rate of soil fertility. The Kundagai themselves consider Tsuwenkai to be sufficiently fertile, though they compare it unfavorably with lower altitudes in Kinimbong, Koinambe, and Bokapai. Informants were adamant that fallow periods were not limited by a shortage of garden land,[6] and the tendency toward longer fallow cycles and clearing of virgin land in 1985 is indicative of abundant land resources rather than falling productivity.

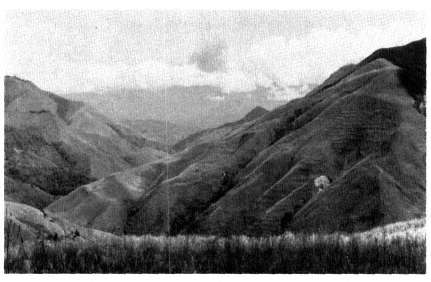

Grassland

The most extensive grasslands in the Tsuwenkai region are close to its southern boundary. Oral traditions indicate that the larger tracts of grassland from Korapa southward have remained relatively stable in area for about two hundred years, although there may have been some expansion of grassland on Komongwai. Aside from oral traditions the antiquity of these grasslands is further suggested by the component species. Themeda , which grows on older grasslands with poorer soils (Henty 1969: 1), is probably the dominant species in most grassland associations. Kunai grass, Imperata cylindrica , dominates in some widely scattered areas. Grassland covers about 2 to 2.5 square kilometers, or about 9 percent of the total Tsuwenkai area. The largest single area of grassland, on Komongwai, is just over one square kilometer in area.

There is one further vegetational and ecological zone in the middle and lower reaches of the Jimi. This is characterized by primary lower-montane rainforest, termed wora by the Maring to distinguish it as an ecological zone from the kamungga . There is no such forest in Tsuwenkai territory, although it is present in Kundagai lands in Bokapai and Kinimbong. The term wora , however, is sometimes applied to advanced secondary forest near the Kant River to distinguish it from primary high-altitude forest.

Effects of Human Activity on the Environment

As already noted, the zone of human habitation owes its characteristics largely to the activities of man, having developed on sites cleared for gardens. Humans continue, however, to have an influence on the vegetation long after regrowth has reclaimed their gardens. Primary and secondary forest is exploited for a wide range of vegetation used for technological, ritual, or magical purposes. During the productive life of gardens, the Maring practice selective weeding, generally removing weeds and shrubs but sparing tree seedlings (Rappaport 1968). The result of such selectivity almost certainly produces forest somewhat different in composition and conformation from what it might have been if allowed to develop without interference. Foraging domestic pigs also cause some damage to the forest ground cover, uprooting saplings and shrubs up to altitudes of about 2,000 meters on ridges closest to the settlement. Such interference need not be detrimental to the ecosystem. The succession of secondary growth to climax forest is apparently not prevented, though it may be retarded.

The area of secondary growth and gardens is largely the product of about the last seventy years of continuous occupation (see below). There is evidence, however, to suggest that most if not all the stable grasslands in the Pint Basin are disclimax communities growing on former forested land gardened by earlier inhabitants of the region.

Several Kundagai recognized that stable grassland can develop on sites of former human occupation and attributed the extensive grasslands of the Pint Basin to human activity. The role of fire is also recognized in maintaining grassland, and with this in mind the Jimi Local Government Council has drawn up a by-law forbidding the burning of grassland. The Kundagai actively attempt to reclaim grassland for agricultural use by planting casuarinas. The success of this program was evident in the marked reduction in areas of grassland within the settlement between 1978 and 1985.

Pigs are probably also instrumental in maintaining grassland communities. Except on rare occasions feral pigs are unknown in Tsuwenkai. The effects of pigs on the environment are therefore ultimately a consequence of human occupation. By uprooting tussocks in grassland, pigs may also destroy seedlings of other plants colonizing some areas. Pigs can churn up large areas without killing the grasses themselves.

Factors contributing to the maintenance and reclamation of grass-

land probably balance one another, for the total area of grassland in the Pint Basin as a whole does not appear to have changed much in the decade 1959-1969 (Healey 1973: 17).

It is not clear, however, whether the amount of Tsuwenkai forest has decreased over recent years. The population appears to be increasing (see below), and one might therefore expect that more gardens are now being cut. It seems likely, nonetheless, that the amount of Kundagai land under cultivation has actually decreased over the last two decades. In the 1940s the Maring as a whole were reduced by about 25 percent in a severe dysentery epidemic (Buchbinder 1973). Then in 1955 or 1956 the Kundagai suffered another epidemic, probably of influenza, which informants say took a heavy toll of life. Before this epidemic they were more numerous than at present. My genealogical data are insufficiently detailed to test this statement statistically, but they do suggest a higher death rate of young and middle-aged adults for the time of sickness than for other periods. It is quite likely, therefore, that informants' statements are accurate and that the Kundagai do not require as much garden land now as in the past.

Although there has been continuous settlement of Tsuwenkai for the last seventy years, the population fluctuated greatly until about 1955-1956. The largest population up to that date was probably in about 1930-1935 or 1940 when the figure may have approximated the present level. In the mid-1950s a major movement from Kinimbong to Tsuwenkai occurred. Since then the population has remained fairly constant or grown somewhat. In the years preceding the last Kundagai konj kaiko or pig-killing festival in 1960, however, many more gardens than usual were cleared to support the growing pig herd and to provision feasts associated with the ritual cycle. These years probably saw the most extensive clearing of primary and secondary forest for gardens, a conclusion supported by the large amounts of advanced secondary forest in the upper Kant Valley and on the east bank of the Kant, which are said to have been last gardened prior to the kaiko . It seems likely, therefore, that for the present, the area of climax forest is actually increasing slightly as older secondary growth completes its stages of succession.

This situation may not continue for long, as population growth appears to be accelerating, partly because of easier access to medical facilities in Tsuwenkai—an Aid Post was established in 1974—and at the Koinambe Hospital. Undoubtedly the area under cultivation will have to be expanded in the future. However, since there appears to be

more secondary growth than the present demands for garden sites require, it will be some time before the Kundagai find it necessary to clear more primary forest or shorten the fallow cycle in existing secondary growth to accommodate more gardens.

Increases in coffee plantings may accelerate population pressure on the land. Coffee is the only cash crop grown in Tsuwenkai and was introduced in the late 1960s. Extensive plantings did not occur until the 1970s, and now most men have at least one small plot of a few score trees.

I cannot estimate the total area of coffee plantations, although it is probably only a very small proportion of the zone of human habitation. Rising coffee prices, however, stimulated greater plantings in the late 1970s. Since coffee is a semipermanent crop, further planting means that increasing amounts of land are being lost to the subsistence economy. This expansion coupled with a growing population will necessitate the cutting of new gardens in the pool of secondary forest in excess of present requirements for fallow land.

Population Density

The overall population density is about 12 persons per square kilometer. The economic density—the ratio of people to areas of garden and fallow land—is 48.25 persons per square kilometer. This figure would be lower if areas of potentially arable primary montane forest were considered in addition to currently and formerly cultivated land.

The overall population density in Bokapai land is about twenty-one persons per square kilometer, and in Kinimbong about nineteen to thirty-one per square kilometer. The lower figure relates only to Kundagai inhabitants, the higher includes about sixty Aikupa clansmen living in association with the Kinimbong Kundagai. I do not have data on the area of arable land in these locales to estimate economic densities, though these are possibly higher than in Tsuwenkai. Overall density throughout Kundagai territory, comprising some fifty-nine square kilometers, is about seventeen persons per square kilometer.

Table 1 compares the population densities of several Maring communities.

The of the Simbai Valley have the lowest known overall population density of any Maring group. The Tsuwenkai Kundagai have the next lowest figure, whereas their economic density is just above the mean for all fifteen populations listed. It is notable that the

TABLE 1. | |||||

Populationa | Number | Territory size (km2 ) | Overall pop. density/km2 | Area arableb land(km2 ) | Economic density/km2 |

Tsuwenkai Kundagai | 304 | 25.0 | 12.0 | 6.3 | 48.3 |

Bokapai Kundagai | 605 | 28.8 | 21.0 | ||

Kinimbong Kundagaic | 90 | 4.8 | 19.0 | ||

All Kundagai | 999 | 58.6 | 17.0 | ||

Tsembagad | 203 | 8.5 | 23.9 | 3.3 | 61.5 |

Tuguma | 255 | 7.8 | 32.7 | 5.8 | 44.0 |

Kanump-Kauwil | 342 | 10.6 | 32.3 | 6.1 | 56.1 |

Kandambent-Namikai | 324 | 11.6 | 27.9 | 6.7 | 48.4 |

Tsenggamp-Mirimbikai | 160 | 8.2 | 19.5 | 2.6 | 61.5 |

Bomagai-Anggoiange | 130 | 9.0 | 14.4 | 8.1 | 16.0 |

Funggai-Koramaf | 155 | 16.9 | 9.2 | 11.5 | 13.5 |

Ipai-Makap | 200 | 11.6 | 17.3 | 3.2 | 61.8 |

Kauwatyig | 850 | 28.5 | 30.0 | 23.0 | 36.9 |

Manambanh | 622 | 28.0 | 22.0 | ||

Tugumengah | 800 | 25.0 | 32.0 | ||

Ambrakwih | 270 | 14.5 | 18.6 | ||

Total | 5,310 | 227.2 | 73.4 | ||

Mean | 354 | 16.2 | 22.1 | 8.1 | 44.8 |

a See app. 4 for locations. Data source: own material and Buchbinder (1973) unless otherwise noted below. | |||||

b lncludes only land currently under cultivation and fallow. | |||||

c Excludes allied Aikupa clan, territory size unknown. | |||||

d From Rappaport's (1968) data the equivalents are: population 204; territory size 8.3 km2 ; overall density 24.6/km2 ; area arable land 3.5 km2 ; economic density 58.3/km2 . | |||||

e From Clarke's (1971) data the equivalents are: population 154; economic density 32.7/km2 ; from which the area of arable land can be computed as 4.7 km2 . | |||||

f Lowman-Vayda (1971) gives population densities as 9.3 and 28.7/km2 . | |||||

g From Lowman-Vayda (1971). Areas are computed from recorded densities. | |||||