Preferred Citation: Lewis, Martin W. Wagering the Land: Ritual, Capital, and Environmental Degradation in the Cordillera of Northern Luzon, 1900-1986. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2d5nb17h/

| Wagering the LandRitual, Capital, and Environmental Degradation in the Cordillera of Northern Luzon, 1900–1986MARTIN W. LEWISUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1991 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Lewis, Martin W. Wagering the Land: Ritual, Capital, and Environmental Degradation in the Cordillera of Northern Luzon, 1900-1986. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2d5nb17h/

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have often had occasion to think that I was fortunate to have attended graduate school in geography at Berkeley when I did. The 1980s saw the traditional concerns of the department, human-environmental relations culturally and historically framed, coexisting—however uneasily—with a vigorous movement toward social theory. Had I enrolled any earlier or later, I doubt that I would have received an education sufficiently broad to have allowed me to write this work.

My debts at Berkeley are numerous. James Parsons's utter delight in landscape will ever be an inspiration, as will Bernard Nietschmann's intellectual courage and iconoclastic visions. To Michael Watts I owe a grounding in political economy; to Robert Reed and to anthropologist James Anderson, many thanks for introducing me to things Philippine. Fellow graduate students from Berkeley played a formative role as well; great appreciation goes to Paul Starrs, Karl Zimmerer, and especially, Karen Wigen.

The geography department at George Washington University has offered an ideal environment in which to prepare the manuscript. Don Vermeer consistently provided support and encouragement, while Deborah Hart furnished intellectual companionship. Monica Jordan was ever helpful. I would also like to thank Joel Kuipers of the G.W. anthropology department for many stimulating observations.

Numerous Cordilleran scholars have substantially contributed to this work. My most perceptive critic has been William Henry Scott, whose scholarship on the Philippine highlands has set the standard of the field. Harold Conklin enthusiastically pushed my inquiries forward in several important directions; to him I owe my deepest appreciation. Special thanks also go to Gerard Finin and Patricia Afable for generously sharing their works in progress. In Benguet, Bridget Hamada-Pawid offered suggestions and advice

that proved essential for the completion of fieldwork. All of the scholars associated with the Cordilleran Studies Center of the University of the Philippines, Baguio, provided great assistance for which I am most grateful. My debt to the Cordillera's local intellectuals—those perceptive observers of their own societies unschooled within academia—is too vast to be recorded here. (Their contributions are discussed in the introductory chapter.)

Financial support for fieldwork was generously provided by a Fulbright Fellowship. Archival work in the United States was funded by a University of California Graduate Humanities Research Grant. A Junior Faculty Incentive Grant from George Washington University allowed me to complete the manuscript. Many thanks to Ellen White for the cartographic work. And finally, this book would not have been possible without the continued support of Kathryn and James Lodato, and of Nell and Wayne Lewis. To the latter I am indebted beyond reckoning.

M. W. L.

1

INTRODUCTION

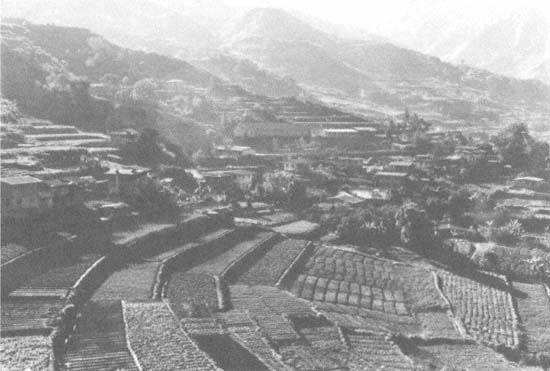

Abatan, Buguias, April 15, 1986

Five long hours by bus from the highland resort city of Baguio lies the unremarkable town of Abatan, a cluster of colorless storefronts of corrugated iron. Perched on a narrow ridge between the headwaters of the Agno and Abra rivers, the huddled buildings of this unpretentious town belie its importance as the marketing headquarters of the northern Benguet vegetable district, centered here in the municipality of Buguias. Where the ridge drops sharply away on both sides, metal sheeting gives way to terraced gardens of cabbages and potatoes extending hundreds of meters down the mountain slopes.

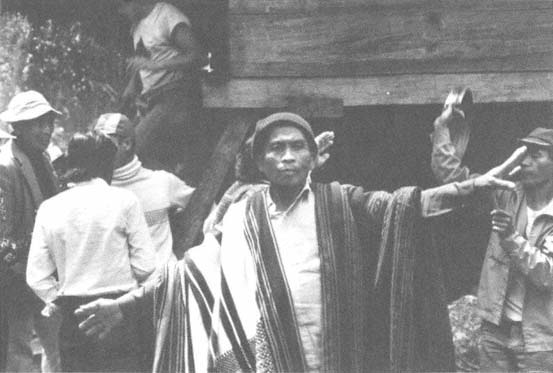

Abatan on most days presents a stark townscape, but a traveler passing through on April 15, 1986, would have witnessed a remarkable sight. On that day, dozens of vegetable trucks packed with villagers converged from miles around on the center of town. Some five thousand persons, representing over forty villages, had come to receive meat and rice beer, to dance and sing, and, most importantly, to worship their ancestors. Of the many prestige feasts celebrated in the Buguias region every year, this event was extraordinary. The celebrants had laid out a repast worth over 300,000 pesos, or $15,000 U.S., including twenty-seven water buffalo and cattle, scores of hogs, heaps of rice, and countless jugs of rice beer. The purpose of the staggering expense was to enlist supernatural assistance for accumulating further wealth.

The Transformation of Buguias Livelihood

Only fifty years ago, the ridge on which Abatan sits was covered with thick forests of pine and oak. On the lower slopes of the adjacent Agno Valley, herds of cattle, water buffalo, and hogs roamed

free in a landscape dotted with small hamlets, irrigated rice plots, and sweet-potato fields. But fierce battles at the end of World War II ravaged herds and fields, demolishing in the process an extensive local trade network that had underwritten social power and wealth. The old ways were never to revive. Within ten years, most residents of Buguias municipality were fully committed to market gardening.

For a time, temperate vegetables provided a measure of real prosperity. Considered a showcase of rural development during the 1960s, the area's landscape still signals the relative wealth of its inhabitants. Houses here are more solid, and clothing more ample, than in almost any lowland area of the Philippine archipelago, a fact not completely explained away by the cool highland climate. Numerous trucks of all sizes similarly testify to past profits, just as the insecticide and fungicide advertisements plastered over the public buildings bespeak a high-yield, chemical-intensive agriculture.

The wealth derived from vegetables also allowed the Buguias people to perpetuate a tradition of redistributive feasting. In earlier days, extravagant animal sacrifice typified religious practice throughout the southern highlands. During the 1830s the would-be conquistador Guillermo Galvey counted some 1,300 hog and water-buffalo skulls on a single house in the village of Kapangan (Scott 1974:214). Yet Kapangan, located on the far fringe of the vegetable district, has not seen a sizable feast in decades. By the 1980s, it was only the market-gardening villages that could finance lavish celebrations. Subsistence-oriented communities, which retained the more environmentally benign indigenous forms of cultivation, greatly curtailed their redistributive feasts after the war, in some instances abandoning the indigenous religion altogether. Benguet's modern center of Paganism—a term used by adherents and their Christian challengers alike—is the thoroughly commercialized village of Buguias Central, focus of this study.[1]

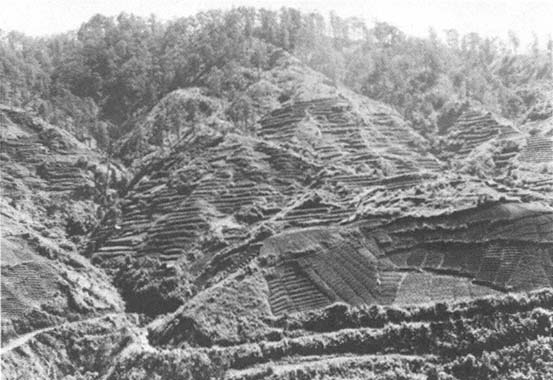

Today, Buguias's prosperity looks increasingly tenuous. Largescale operators, vegetable traders, and chemical merchants continue to reap substantial profits, but the highland vegetable district as a whole saw its agriculture stagnate and its living standards decline as the Philippine economy stalled and sputtered through the

1970s and 1980s. Most growers have fallen deeply into debt, not uncommonly receiving less now for a given crop than they have to pay for seeds and chemicals. Nor does vegetable agriculture appear to be ecologically sustainable. Biocides and fertilizers have polluted local water supplies, erosion steadily denudes the steeper slopes, and deforested watersheds yield ever-diminishing stream flows.

Yet despite growing ecological peril and economic uncertainty, the people of Buguias remain committed to the gamble that is market gardening. Although they live under a constant threat of market collapse, farm families hope for the unpredictable upturns, wagering their crops—and increasingly their environment—on the day when they may reap the coveted "jackpot" harvest. For gambling is a fundamental precept of life in Buguias, albeit not exactly gambling as we conceive it. Many of the manifestations are familiar: boys of five and six wager their pocket money on the flip of a coin; young men frequent the cardhouses, cockpits, and casino of Baguio City; even elders bet compulsively at rummy. But most Buguias people do not consider fate to be blind; rather, they believe that risk can be manipulated through ritual. Like their grandparents before them, most contemporary villagers attempt to ensure the success of their most chancy undertakings through placating their ancestors and feasting their neighbors. It is the resulting nexus of economy, ecology, and religion, with its unusual concatenation of capitalist transformation, cultural persistence, and environmental degradation, that forms the core of this work.

Commercialization and Local Change

Commercial Agriculture and Environmental Degradation

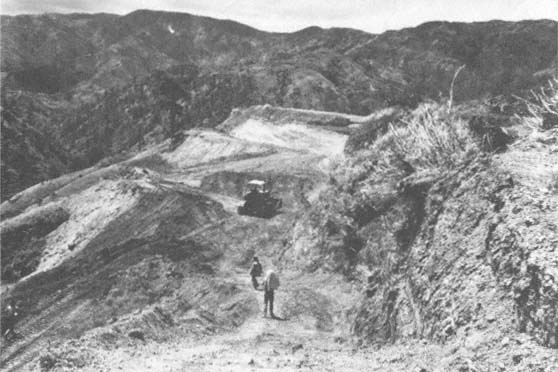

The environmental destruction accompanying the spread of commercial agriculture along the margins of the global economy is now well documented by geographers and anthropologists. Areas previously marked by sustainable subsistence cultivation soon exhibit such symptoms as rapid soil erosion, deforestation, and pesticide

contamination (Nietschmann 1979; Blaikie 1985; Grossman 1984; Grant 1987). Damage most commonly results when impoverished growers are forced to retreat to ever more marginal lands (Blaikie and Brookfield 1987). In Buguias, however, it is primarily the most prosperous farmers—those wealthy enough to hire bulldozers to flatten hilltops and to construct private roads—who precipitate erosion and deforest the slopes. Wealthy growers expanding into the fertile eastern cloud forests also destroy watershed vital for the entire valley, and increasingly outcompete the growers in the older, exhausted districts. But all villagers, rich and poor alike, degrade their lands, especially by unleashing biocides and fertilizers into the streams of the region.

This devastation does not stem from cultivators' ignorance or mismanagement. Benguet vegetable culture is in many respects intricately fitted to the local landscape, with each crop cultivated in the precise microhabitat to which it is best adapted. Moreover, most gardeners are aware of the dangers of chemical contamination and denuded slopes. But the commercial system in which they are imbricated leaves them few alternatives. With a long-term decline in profits and a notoriously capricious vegetable market, growers must feverishly intensify production in a desperate attempt to avoid losing ground during poor seasons (what Bernstein [1977] calls the "simple reproduction squeeze"). And the prospect of unpredictable price jumps propels them in the same direction; the lure of a jackpot harvest brings an even higher pitch of activity during the perilous typhoon season, a time marked by accelerated erosion and periodic market windfalls.

The environmental and social pressures of market-oriented agriculture in the global periphery can be extraordinarily destructive; in the worst cases, as Watts has shown for Nigeria, the "horrors and moodiness of the market" (1983:xxiii) can bring famine and mass starvation. But the vegetable districts of northern Luzon have as yet seen only the early warnings of an ecological and economic debacle. The vegetable farmers today remain the envy of both subsistence growers in the mountains and impoverished peasants in the lowlands. Nor has the market's individualizing force brought cultural dissolution as it so often does. In fact, far from destroying local culture, commercial development has greatly enhanced its

central feature, the redistributive prestige feast. But the very continuation of communal feasting has actually become an accomplice to the environmental breakdown.

Commercialization and Redistributive Feasts

While Buguias's environmental destruction replicates a sadly familiar pattern, its elaboration of communal feasting in conjunction with commercial gardening is unusual. Such rituals need not vanish as a community becomes tied to larger economic circuits; indeed, the most famous redistributive rite, the potlatch of northwest North America, flowered after trade links were established with European merchants (Belshaw 1965:28). Yet a long-standing scholarly tradition holds that such feasts, and communal ties in general, wither away once a society is incorporated into the world economy. Bodley (1975:167), for example, argues as follows:

Integration is not possible unless tribal cultures are made to surrender their autonomy and self reliance. When these are replaced by dependence on . . . the world market economy, a whole series of changes will follow until virtually all of the unique features of tribal cultures have been replaced by their contrasting counterparts in industrial civilization.

A pivotal agent of such change is usually said to be an emergent capitalist class, if not a generalized capitalist mentality, that resists ceremonial and other social outlays. As Grossman (1984:10–11) writes:

Villagers also want to free themselves from traditional social obligations that they believe hinder capital accumulation. Their individualistic behavior is manifested in a variety of realms: the extent of sharing, reciprocity, and cooperation in cash-earning activities is less than in traditional subsistence-oriented endeavors. . . .

And even when ceremonial exchange does persist under expanding market relations, "ritual inflation" (in which wealthy individuals devote ever-larger sums to display while the poor are disenfranchised) may undermine its stability, if not the entire social order (Grossman 1984:23; Volkman 1985:7; Hefner 1983:683). In a simi-

lar argument, James Scott (1976) links the spread of commercial relations with the downfall of a communitarian ethos in mainland Southeast Asia. In the precolonial states of this region, he argues, peasant politics were centered around a "subsistence ethic" that united each community within a "moral economy" and militated against risk-taking and profit-seeking behavior. With colonial rule, however, "the commercialization of the agrarian economy was steadily stripping away most of the traditional forms of social insurance" (Scott 1976:10).

During the heyday of modernization theory in the 1950s and 1960s, most scholars applauded the market's ability to displace traditional cultural forms. Religion in general was thought to fetter development (see von der Mehden 1986:5), and many observers predicted that competitive economics would destroy communal institutions, leading eventually to "detribalization" (see de Souza and Porter 1974). Present-day writers tend to view cultural breakdown in the wake of commercialization as ethnocide rather than progress, but they have inherited the assumption of its inevitability. The two schools' analysis of the occasional survival of communal feasting bears this out. What constituted for modernization theorists an irrational stumbling block has become for scholars of the underdevelopment camp a bulwark against capital, the key to cultural persistence, and a core around which to organize political resistance.

Voss (1983) has recently extended the anticommercial version of this thesis to the Cordillera of northern Luzon. He argues that redistributive rites are declining in commercialized areas, but that their survival limits capitalist penetration elsewhere. Specifically, he holds that in Sagada "the maintenance of such non-commercialized relations as redistributive feasting . . . has been instrumental in limiting class differentiation" and in molding market economics into a socially benign form, whereas in the Buguias region, he claims, socially atomized and fully capitalistic producers have reduced their ceremonial expenditures to a minimum (1983:14–15, 225–230).

Voss is probably correct in regard to Sagada, the primary locus of his research, but I would argue that he misrepresents feasting in Buguias. In Buguias not only are public feasts much more common than in Sagada, but more importantly, they are strongly reinforced

by agricultural commercialization. Farmers who successfully accumulate must also feast their neighbors. This should not surprise us. It has long been acknowledged that "redistribution" is usually a misnomer for what happens in prestige feasts; as Wolf (1982:98) writes, "Feasting with the general participation of all can go hand in hand with the privileged accumulation of strategic goods by the elite." Yet conventional academic wisdom has not taken this point to heart. Commercialization does often leave cultural wreckage in its path, but as Buguias shows, such is not invariably the case (for examples other than Buguias, see Parker [1988] and Fisher [1986]).

In Buguias, public and private interests are tightly fused. The celebrants of the community's grandest feasts are its most successful entrepreneurs, individuals who invest in business expansion as well as in communal rites. And with few exceptions, those who have renounced, often on economic grounds, the old religion they call Paganism have been unable to translate their savings into prosperity. Pagan ideology expressly endorses commercial ventures, reserving its highest accolades for the "progressive" individuals who work hard, adopt new technologies, invest in productive enterprises, and lend money for gain—so long as they also honor their ancestors and feast their neighbors.

Theoretical Underpinnings

The conceptual framework adopted here derives in part from "regional political ecology," a recent movement formed through the marriage of the environmental concerns of cultural ecology and the developmental focus of political economy. In this emerging literature, social conflict and land degradation tend to be emphasized over the communal harmony and environmental adaptation highlighted by earlier scholars. (See, in geography, Grossman 1984; Blaikie and Brookfield 1987; Bassett 1988; Zimmerer 1988; Hecht and Cockburn 1989; and Turner 1989. In anthropology, see Schmink and Wood 1987; and Sheridan 1988). Inspiration is also found in traditional cultural geography, which approaches the human modification of local environments as deeply rooted historical processes, molded in part through the cultural perceptions of human agents. Culture is viewed here not as an autonomous, "super-organic" entity (see Duncan 1980), but rather as inextricably bound

up with politics and economics, continually reconstituted and reshaped through subtle interplay between individuals and social groups.

The underpinnings of the "political" side of political ecology derive largely from radical development studies. This tradition has been fruitful in illuminating specific economic processes behind local environmental change in the modern era, which must in most instances be analyzed within the context of global capitalism. But it has also biased the field against recognizing that "precapitalist" societies, and certainly "socialist" ones, often evince similar processes of land degradation. Blaikie and Brookfield (1987) offer one corrective in the novel tactic of collegial disputation, one writer arguing from a Marxist background and the other countering from a behavioralist stance throughout a coauthored text. Although writing in a dialogic mode is not an option for the solo author, I have allowed a degree of theoretical agnosticism into this text by (loosely) employing both Weberian and Marxian notions, tending toward the latter when analyzing the economy, and veering toward the former when considering religious issues. Both traditions offer powerful lenses that can profitably be trained on social and ecological change in Buguias; to take either one alone is to risk limiting inquiry and obscuring those processes that defy expectations.

One of the fundamental premises of this study is that social, cultural, economic, and ecological change must be analyzed in dense empirical detail. Here I am especially inspired by Stephen Toulmin, whose richly eloquent Cosmopolis (1990) thoroughly undermines the modernist agenda of "universal, general, and timeless" theorization and instead leads the way into a more humane appreciation of "the oral, the particular, the local, and the timely" (1990:186)—all conceived within a fluid ecological perspective. Thus, while employing a variety of theoretical constructs, I have avoided couching the findings within any "grand theory." My ethnographic sensibility leads me to seek "explanation[s] of exceptions and indeterminants rather than regularities" (Marcus and Fischer 1986:8); by the same token, as a geographer I am wary of "spatial over-aggregation" (Corbridge 1986). Broadly similar patterns often emerge where modern economic processes transform ritual and ecological practices, but a useful heuristic for directing the questions must not become a limiting template for interpreting

findings. Commercialization has often dissolved communal bonds, but its failure to do so in Buguias does not necessarily mean that we have found an aberrant exception. In practice, this means being willing to revise radically one's preconceptions. I argue from experience here; having arrived in Buguias with a deep Polanyian (see Polanyi 1957) skepticism regarding "precapitalist" markets, I was only gradually, and painfully, disabused of this romantic notion as I delved into the commercial history of Buguias.

Field Methods

In probing the paradoxes implicit in interpreting "the other," Marcus and Fischer (1986) conclude that fieldwork is essentially dialogic, a fact that they argue should be acknowledged by incorporating the voices of the studied not as informants but as collaborators. Such an approach, they claim, can open doors to indigenous "epistemologies, rhetorics, aesthetic criteria, and sensibilities" (1986:48).

This project followed Marcus and Fischer's dictum in important ways. From the day I arrived in Buguias with Karen Wigen, my wife and fellow geographer, research was not only facilitated but actually guided by a local couple, Lorenzo and Bonificia Payaket. The Payakets took keen if often amused interest in all of our questions, repeatedly suggesting new avenues of inquiry. In particular, although we entered the field with no intention of studying religion, they insisted on introducing us to indigenous priests. Their message was simple: to understand Buguias you must understand religion. Eventually we deferred.

After a few weeks in Buguias, a basic routine was established. Each evening, two or more of us would meet to determine the next day's explorations, the Payakets suggesting local experts with whom we could consult on a given topic. The following morning, we would walk to where the chosen individuals lived and interview them, often through the agency of field guides. In the early months our inquiry was limited to the village of Buguias Central. Gradually we began to venture farther afield, eventually making foot and bus journeys of several days to visit each settlement prominent in Buguias's history.

After returning home we would again confer with the Payakets, who would judge the reliability of our findings, suggest individu-

als who could either corroborate or give conflicting accounts, critique our field maps, and add observations of their own. These evening discussions can only be described as seminars. The sessions grew particularly lively when the Payakets brought with them individuals expert in the subjects at hand. But all conversations eventually wandered freely, leading in many unexpected directions. Nor did we limit ourselves to empirical findings; our evolving interpretations also formed a conversational mainstay.

Through these alternating interviews and evening discussions we gradually elicited the outline of Buguias's history presented here. Although I have also consulted the standard sources of historical scholarship (colonial documents, travelers' accounts and diaries, early scholarly reports, and newspaper articles), these rarely elucidate the most important local developments. Since Buguias was and is a predominantly oral culture, living memory is the primary source for reconstructing the community's past. In seeking standards of reliability, I follow Rosaldo's (1980) lead; where numerous individuals reiterate the same story, without contradictions, I have accepted it as most likely true. Where consensus is not obtainable, conflicting versions are retained with no attempt to choose among them.

Any interpretation is by nature partial, as much allegory as analysis. As such, the story told here remains to the last only one among several possible "true fictions" (Clifford 1986) that could have been wrought from the ethnographic materials pertaining to Buguias. If my time in Buguias proved conceptually liberating, it did not, however, divest me of all prior ideological baggage. Moreover, the individuals with whom I worked have undoubtedly inscribed on the text their own prejudices and programs as well, seeking to project their community in a specific light. The author bears final responsibility for any errors compounded through the numerous tissues of interpretation that constitute the work.

Identifying Buguias in the Ethnographic Landscape

The indigenous inhabitants of the Cordillera, collectively referred to as Igorots (a term some groups find offensive), were never hispanicized, and they retain a limited cultural autonomy to this day.

Map 2.

The Standard Ethnographic Map of the Cordillera of Northern Luzon.

Western ethnographers have divided these highland peoples into seven or eight major groupings, once considered tribes, now usually termed ethnolinguistic groups (LeBar 1975, Keesing 1962; see map 2). But the categories employed here reflect a convoluted history of academic misconceptions (for an indigenous scholar's as-

sessment of the standard ethnographic classification, see Magannon 1988).

In the nineteenth century, Spanish and German observers partitioned the Cordillera by entirely different schemes; these may have been less accurate but they were no more misconceived than those later perpetrated by the Americans. The American ethnographic map originated with the outrageously sloppy scholarship of Dean C. Worcester, self-styled white deity of the archipelago's non-Christians (see Hutterer 1978). Finding the Spanish and German classifications cumbersome, Worcester (1906) took it upon himself to define new groups among the highlanders. Unfortunately, he seriously misunderstood the foreign-language sources he was criticizing.[2] In classifying the various Cordilleran peoples, Worcester ultimately relied on visually distinctive cultural features casually observed by himself and his friends.[3]

Competent ethnographers later modified Worcester's system. In Benguet, Moss (1920a , 1920b ) successfully insisted that the linguistic groups called Kankana-ey (or Kankanay) and Nabaloi (or Ibaloi), long recognized by all able observers, deserved separate "tribal" status. But Worcester's overall scheme prevailed, distorting subsequent ethnographic perceptions. Some of his so-called tribes, such as the Kalinga, were but melanges of dissimilar cultural groups (some of which have since coalesced to a degree); other more coherent groupings, most notably the Kalanguya (or Kallahan), received no recognition at all, simply because neither Worcester nor any colonial anthropologist happened to visit them.[4] Recently linguists have begun to devise a more accurate classification system, but many geographic subtleties continue to elude cultural taxonomists (see, for example, Wurm and Hattori 1983; for the best work on southern Cordilleran linguistic and cultural groupings, see Afable 1989).

The case of Buguias reveals the inadequacies of the standard classificatory scheme. The community lies in the interstice of three linguistic or cultural groups; two of these, the Ibaloi and the Southern Kankana-ey, are now recognized, but the third, the Kalanguya (or Kallahan), remains virtually ethnographically invisible (see map 3). Although Buguias was probably an Ibaloi settlement originally, its residents today are most closely related (genealogically) to

Map 3.

The Languages and Dialects of the Southern Cordillera.

Mandek-ey, or I-Buguias, is at present spoken only

in the southernmost hamlets of Buguias Village.

the Kalanguya; the village dialect (called Mandek-ey, or I-Buguias), while containing elements of all three neighboring tongues, is also most closely affiliated with Kalanguya. Over the past sixty years, however, Kankana-ey has penetrated southward into the village, and today Mandek-ey survives only in the southernmost hamlets of Buguias. As a result, outsiders generally classify Buguias as a Southern Kankana-ey community.

The geographic referent of the term "Buguias" is also equivocal. It originally referred to a single territorially based village, in some respects an indigenous microstate. Like other sizable Cordilleran villages, Buguias was accorded a vague political status under the Spanish colonial regime; gradually this solidified, and today Buguias forms a barangay , the smallest political territory in the Philippines. The modern barangay, called Buguias Central, corresponds

Map 4.

Buguias Village. The dashed line encloses the modern barangay of Buguias Central; the solid line encloses the

traditional village, or ili , of Buguias. The traditional village was divided into four constituent units (Tanggawan,

Balagtey, Giwong, and Demang) during the American period. These smaller ili function today

imperfectly to the old village, since over the years some hamlets have been grafted to the original community while others have been deleted from it (see map 4). Only in the ritual realm does the old communal structure survive, and even here it was significantly transformed when the village elders, sometime in the American era, split the old village into four constituent sacerdotal units.

But "Buguias" also refers to an area larger than the barangay, or village, of that name. The southern Cordilleran peoples have long classified their neighbors according to several partly overlapping ethnographic systems, based respectively on language, environment, and proximity to large, older settlements. Since Buguias has long been an important community, its name is applied to a region extending well beyond the boundaries of the village itself. To their Cordilleran neighbors, "the Buguias people" includes not only the inhabitants of Buguias village but also the residents of surrounding communities—individuals who would identify themselves as being from Buguias when visiting distant places.

Roughly corresponding to this region is Buguias municipality in the imposed political hierarchy (see map 5). Both the Spanish and the American colonialists administered sections of the southern Cordillera through the larger villages, first designated rancherias , later townships, then municipal districts, and finally municipalities. Since the Americans continually sought to economize by consolidating these units, municipal boundaries remained unstable. Early in the century, for example, "greater" Buguias annexed its northern neighbor, Lo-o. Even under the postcolonial Philippine regime, Cordilleran municipal boundaries have shifted as municipalities have vied for several tax-rich border zones. At the same time, villages within the same municipality have sometimes contended for the seat of local government, further reworking geographical alignments. Buguias municipality, in fact, has for some years been administered not from Buguias Central but from the more accessible crossroads community of Abatan.

In this work, "Buguias" will refer both to the indigenous ritual village (now divided into four units) and to the modern barangay. Although the boundaries of these two divisions are not exactly coincident, ambiguity is minimal. When the larger regional unit is intended, it will be designated either as Buguias municipality or as greater Buguias.

Map 5.

The Municipalities of Benguet Province. (Refer to map 1 for relative

location.) The city of Baguio forms an enclave, independent from the

surrounding province.

Overview

This work comprises two intertwined allegories. The first concerns the persistence of a society and the continued florescence of a culture, the inverse of a long dominant theme. The second tells a more familiar and more tragic tale: while this culture has so far abided the engulfing global economy, its very foundation is at risk. Buguias's commercial gambit may simply prove to be a brilliant disaster.

The story opens with a view of the landscape of Buguias as it appeared in the time of American rule. The initial chapter outlines subsistence production, an environmentally benign agricultural system that nevertheless radically transformed the landscape of Buguias. The following chapter explores the contours of social life, which were marked by distinct class stratification but tempered by frequent interclass mobility. A look at the ritual system, in which consumption climaxed, rounds out the picture of prewar Buguias as a self-contained community. The discussion then broadens out to consider the wider networks within which the Buguias people operated. Chapter 5 maps first the geography of trade, and then the penetration of imperial power. This completes Part I, a largely synchronic cut at prewar life.

World War II constituted a radical discontinuity in Buguias history, and with an interstitial discussion chronicling the war's devastation, the narrative takes a more diachronic turn. The story of the postwar era in Part II opens with the drama of reconstruction. The first two chapters of this second part cover the vegetable boom years from 1946 to 1973; the remainder of the work focuses on the era of stagnation and turmoil beginning in 1973 and continuing to the late 1980s. Topically, the discussion thus progresses from the successful rise of the new agroecological and economic order to its darker underside, the social tensions and environmental traumas that are increasingly revealed. The work concludes with an analysis of religion, the focal point of current ideological, economic, and political contention.

PART I

PREWAR BUGUIAS

2

Food, Fuel, and Fiber:

Human Environmental Relations in Prewar Buguias

Introduction

A view of Buguias from the air in the 1920s would have revealed a complex landscape of interwoven plant communities. On the highest reaches of the eastern slope, outliers of the dense, oakdominated cloud forest (or kalasan ) protruded below the misty ridgeline of the Cordillera. Downslope, the oaks gave way to single-species pine stands, forming a true forest on the higher and steeper slopes and thinning out at lower elevations. Near the upper hamlets of the village, pines crowned a savannah community of short grasses, yielding on steeper sites to cane-grass swards. Still farther downslope, the pines dropped out altogether, leaving only pasture grasses on the lowest slopes.

Within this broad zonal pattern, variations of soil, relief, and long-standing agricultural practice created a vegetational mosaic. The shady northern faces of steep side canyons supported diverse hardwood thickets, while on their sunny southern exposures grew a jumble of brush, pine, and coarse grasses. Scattered throughout the landscape, but particularly in the lower reaches, were sharply bounded cultivated plots. Most contained tangles of sweet-potato vines, a select few were flooded and planted to rice, and small plots surrounding the village's several score dwellings supported diverse assemblages of herbs and fruit-bearing trees.

This landscape was a cultural artifact, continually reshaped through the labor of the Buguias people as they wrested their livelihood from the land. In provisioning themselves, the Buguias people transformed their homeland, altering both its physical substrate and its biotic communities. Through cultivating and pasturing they worked their greatest ecological transformations. But the residents

of Buguias also gleaned a harvest of wild edible plants and animals, as well as vital nonfood plant products (including fibers, woods, and medicines). All microhabitats of Buguias thus contributed to human livelihood, and all were remolded in turn by human activities.

But if the Buguias people transformed their landscape, the human impact varied widely in extent and duration. Sites found suitable for terracing were entirely remade; others, such as ravines, were only casually tapped for wild produce. The territory of Buguias was thus loosely divided into separate geographical zones, each subjected to different kinds of human pressures.

The fundamental division enclosed the cultivated from the "wild." Both cropped and non-cropped lands were further subdivided according to the plant associations they supported. Agricultural plots were of three distinct named types: dry fields (devoted largely to sweet potatoes), flooded rice terraces, and door-yard gardens. Less exact divisions marked the uncultivated lands, as many species (the insular pine, for example), could grow in virtually any area; yet even here, distinct plant associations emerged in part through human interference. These various plant communities, both wild and cultivated, might aptly be called subsistence sectors (what Wadell [1972] refers to as "agricultural subsystems"), highlighting at once their role in provisioning the human community and their spatial boundedness.

The areal configuration of subsistence sectors was never static. In the long view, fields and pastures expanded steadily. New dry fields could be carved from woodland, meadow, or canebrake; hillsides were slowly terraced; and new pastures sprouted from the charred soils of former woodlands. In specific instances, the direction of change could be reversed. A rice field might yield to cane or brush, for example, if its supply of water suddenly diminished.

The following chapter reconstructs Buguias subsistence as it existed in the 1920s and 1930s, the earliest period accessible through living memory. Deeper historical background is examined through archival sources where possible. The first section details each of the three major agricultural sectors: dry fields, door-yard gardens, and rice terraces. The next two sections outline the products of uncultivated lands. Here subsistence was less rigidly constrained by sector; domestic animals, for example, could often wander through

vast uncultivated areas. These discussions are thus organized along product rather than sectoral lines, first considering domestic stock, and then moving to undomesticated plants and animals. The fourth section examines first human agency in the formation and maintenance of distinct communities of uncultivated plants, and then turns to the processes of agricultural intensification at work in the prewar era.

Agricultural Fields

Dry Fields: Uma and Puwal

The core of livelihood in prewar Buguias was a distinctive form of dry-field cultivation called uma , derived from swidden practices. Like its slash-and-burn antecedents, uma agriculture entailed cutting and burning woody vegetation prior to planting, and in earlier periods all Buguias dry fields had probably exhibited the common features of long-fallow swidden horticulture. By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, the interval between cropping cycles had been shortened sufficiently that most dry fields in central Buguias were cultivated for much longer periods than they were fallowed. In the puwal variant, slashing and burning no longer preceded planting. Both umas and puwals were intensively cultivated plots, adapted in many respects to a savannah rather than to a woodland environment.

Sweet potatoes, the staple of both people and domestic hogs, dominated the dry fields. Tubers were consumed in such quantity as to completely color the memory of prewar subsistence; this was the time, the Buguias people say, "when we ate only sweet potatoes." The common people typically dined on boiled sweet-potato tubers seasoned with sweet-potato vinegar, garnished with sweet-potato leaves, and perhaps completed with a dessert of sweet-potato syrup. In seasons of tuber scarcity, dried sweet-potato chips, either reconstituted in soup or pounded and cooked with millet, sufficed. Subsidiary dry-field crops, including several kinds of beans, peanuts, sesame seeds, maize, panicum millet, sorghum, and Job's tears, provided seasonal supplements, but were never abundant in most households. Among the poor, mealtimes were indeed a matter of "tugi angey " (or "sweet potatoes only").

Buguias dry fields could thrive only on select sites. Slopes had to be gentle for soil fertility maintenance. Clay-rich soils were always favored, for lighter earth would not retain adequate moisture for dry-season (December through April) growth. The natural terraces above the Agno River formed ideal sites, but many had long been appropriated for rice terraces. The gentle and irregular eastern slope of the village afforded the most numerous suitable locations. Here the favored sites were U-shaped hillside indentations formed by slope failure. The flattish deposit of deep soil at the slump foot could support sweet potatoes throughout the year, while the adjacent scarps produced superior tubers in the soggy wet season. In areas of suitable soil and slope, however, uma fields could form a continuous band of cultivation.

In the heart of every Buguias dry field lay the sweet-potato patch, monocropped for fear that other plants would stymie the all-important staple. The generally heavier-feeding subsidiary crops were relegated to the field edges, or occasionally to central strips. Typically surrounding the nucleus were rings of sorghum, panicum millet, maize, and various pulses. Annuals, such as maize, sorghum, and millet (often interplanted with kidney beans) were favored for central strips, since they would not interfere with the long-term sweet potato rotational schedule. In the wettest months (July through September), larger field segments normally planted to sweet potatoes might be devoted to millet or peanuts. (Some growers, fearing rat predation, would distance their millet crop from brushy surrounding growth by planting it in the center of the field.) Seed of the perennial baltong bean (Vigna sinensis ) were sown among stumps or rock outcrops where they would not interfere with sweet-potato cultivation, while brushy kudis beans (Cajanus cajanus ) often occupied drier slopes on field margins.

Buguias women cultivated approximately a dozen varieties of sweet potatoes. Some women intercropped multiple cultivars; others preferred segregation. Generally, those with large fields (.5 hectares or more) cultivated monovarietal patches, which allowed easier management since each cultivar matured at a different rate. The specific varieties planted, whether in mixed or segregated patches, depended in part on the partialities of household members, as each variety had a distinct taste and texture.

Buguias women planted sweet potatoes thrice annually, and harvested each planting up to three times before the vines reached exhaustion at the end of one year. The first planting, in April or May, either anticipated or coincided with the first rains. By October this planting's initial tubers, though fibrous and of poor quality, were ready for harvest. February marked a second harvest interval, and the final one occurred in May. The dry-season tubers were of higher quality, but as the vines aged, quality declined. A second planting in September or early October produced a superior initial crop; the young vines flourished with the copious rains and the tubers could mature as the soil dried. This planting's harvests occurred in January, again in May, and finally in August. December, marking the start of the dry season, brought the final and least productive planting; success then was possible only in the most moisture-retentive fields. Yet this crop too could produce through the entire year; only in the poorest fields was year-round cultivation impossible. Here harvests would be completed early in the dry season, the remaining foliage burned, and the uma fallowed until the arrival of the rains.

The multiple plantings of differentially maturing sweet-potato varieties coupled with (partial) seasonal rotation with other crops and complicated by the differing physical attributes of each field, required a fine-tuned seasonal labor schedule. Uma work was also highly skilled; even the harvest was demanding, since individual tubers had to be removed at their most palatable stage without damaging the vines. Only carefully tended plants could produce through an entire year. From December to March, the prime harvest, Buguias women sliced and sun-dried the surplus, which would form the mainstay in the lean season following the early rains.

The typical uma was cropped for five to ten years, at which point declining yields forced a two- to three-year fallow. This long cropping period was possible only through continual labor. Weeding was the most arduous task; Buguias women would dig several feet into the ground to remove the tenacious roots of ga-on (Imperata cylindrica ) in particular. Weed foliage obtained both within and from the edges of the uma was buried in the field along with the old, uprooted vines, thus helping to replenish the soil.

Intensive dry-field cultivation required gentle slopes and deep soil, but new fields were sometimes relegated to substandard sites. Steeper plots could be upgraded by leveling; stone-walled semi-terraces minimized erosion while maximizing dry-season moisture retention. Unlike rice terraces, such dry terraces needed some slope, since a flat field would waterlog in the rainy season, resulting in tuber rot. These semiterraces were comparatively easy to construct; often little more than a few carefully placed boulders sufficed.

The nutrients added to the uma from field-margin weeds, downward-moving soil (notable in slump-foot cultivation), and legume root nodules were insufficient to offset harvest losses. Over time, tuber size diminished while insects and pathogens multiplied. Exhausted fields were then left to natural succession. Typical invaders included the ubiquitous bracken fern, several exotic composites (Tithonia maxima and Eupatorium adenophorum ), and the cane grass Miscanthus sinensis. After a few years these fallowed umas were cut, burned, and replanted. Abandoned fields on drier sites or in pasture areas were, in contrast, invaded by sod-forming grasses (especially Themeda triandra and Imperata cylindrica ), after which they were characteristically opened to cattle. These tenacious fire-adapted grasses precluded further recourse to the techniques of uma. Rather, if the site were to be recultivated the sod had to be overturned, a practice known as puwal cultivation.

In making a puwal, the cultivator would invert sections of sod with iron-tipped poles. If turned to a depth of some 30 centimeters at the end of the dry season, the grasses would be killed and the soil both aerated and enriched by decaying leaves, roots, and manure. Newly made puwal fields could be quite fertile, encouraging the conversion of prime pastures, even those never previously cultivated. After soil preparation, the puwal was cultivated much like the uma.

Recultivation of the fallowed dry fields was relatively easy; the mandatory fences were already in place (although, if wooden, they would need repair), and, at least with umas, the light successional vegetation could easily be cleared. Newly married couples, however, often had to create new fields. These could be either uma or puwal, depending on the site chosen. Any pine standing on the

site would be salvaged for wood, but other woody plants would be burned in situ for soil enrichment.

Door-Yard Gardens

Haphazard plantings around the houselot constituted the second subsistence sector, the door-yard garden (ba-eng ). Some gardens produced large quantities of vegetables, fruits, and even cash crops, but most were small affairs. Yet the garden did hold two advantages over the uma: manure-enriched soils and easy access.

Tobacco and potatoes, considered too demanding for dry-field cultivation, often grew alongside the nutrient-rich pigpens. Hog manure was also periodically distributed through the rest of the garden.[1] It could be used to fertilize sweet potatoes only if thoroughly composted (Purseglove 1968, v. 1:85), a difficulty that, combined with the burden of hauling, precluded manure use in the dry fields. But even fresh dung benefited most door-yard crops. Several varieties of taro grown for the piggery were especially favored in the garden because of their shade tolerance and vigorous response to casual manure application.

Condiments (Capsicum peppers, onions, ginger, garlic, and sugar cane), and vegetables (lima and other beans, squash), were grown in the door-yard garden mainly for convenience. As new vegetables, such as bitter-gourd, eggplant, and sayote (chayote), appeared during the American period, gardens became more diverse. Sayote quickly emerged as the standby vegetable of all social classes; this perennial produces ample quantities of edible leaves, stems, and fruits, and its large tubers can serve as a famine reserve. Only the larger gardens were dominated by fruit trees (such as mangoes and avocados), since frequent household relocation constrained arboriculture. Poorer households thus rarely grew more than a few banana stalks.

The most valuable door-yard crop was coffee. Introduced in the late Spanish period, coffee cultivation spread rapidly among the elite, who found the beans a valuable trade item as well as a beverage source. Having planted sizable orchards of arabica trees, wealthy individuals soon lost their inclination to relocate their homes periodically. As coffee drinking and trading spread, poorer

couples too planted smaller orchards. But in the final years of the Spanish period, blight struck, damaging especially those orchards located on clay soils. Coffee production henceforth would be concentrated in the gardens of a few wealthy households situated on rich loam.

Pond Fields: Taro and Rice

The irrigated or pond-field terrace, an artificial wetland seasonally planted to rice and, occasionally, to taro, formed the third agricultural sector of prewar Buguias. Among many Cordilleran groups (including the Ifugao, the Bontoc, the southern Kalinga, the Northern Kankana-ey, and the Ibaloi of Kabayan and Nagey), pond fields were a significant, if not dominant, element of the agricultural landscape. In the Buguias region, however, rice was a subsidiary crop, albeit vital as the source of rice beer. Buguias residents seldom ate unfermented rice, and on the rare occasions when they did, they usually mixed it with millet or dried sweet potatoes.

The first pond-field terraces in Buguias may have been designed for taro.[2] This most versatile of crops grew unirrigated in dry fields and door-yard gardens, but it produced larger, if poorer tasting, tubers when cultivated in water. In prewar Buguias, taro grew in several aqueous niches: along irrigation canals, in natural seeps, around small ponds, on the edges of rice terraces, and in small terraces of its own. A vastly greater expanse of pond-field land, however, was devoted solely to rice.

Rice beer in prewar Buguias was a necessary ritual intoxicant. Virtually all couples occasionally brewed beer, but only the wealthy owned pond fields; poorer individuals purchased rice or worked in the paddies of wealthier relatives. Even couples possessing extensive terraces (up to several hectares) fermented the bulk of their harvests. The sweet and yeasty beer dregs, however, made a treat especially beloved of small children.

Buguias's pond-field system gradually expanded through the late Spanish and early American periods. Natural river terraces, reasonably level and low enough in the valley to be dependably watered, formed ideal building sites. Some lower terraces could be irrigated directly from the Agno River, but the necessary diversion works would be demolished annually in typhoon floods. More man-

ageable water sources were the non-entrenched, perennial side streams and the natural seeps. But by the American period, continued pond-field expansion necessitated the excavation of canals—some several kilometers long—to tap the larger eastern tributary streams.

Labor in the rice fields was arduous. Leveling and churning the muck had originally been done entirely by hand, although by the later American period some individuals had harnessed water buffalo for the task. Seedbeds, started in November or December, were ready for transplanting by January, although fields watered from the community's several hot springs could be planted a month or more later. By April, the enlarging grains required the constant vigilance of old men and children to ward off birds and other pests. In July, hastened by the impending typhoon season, the fields were reaped. After harvest they remained flooded, thus receiving nutrients from typhoon-eroded sediments. The only other fertility supplements consisted of Tithonia leaves and water-buffalo manure, the latter deposited casually when the animals worked the fields or wallowed in them during the off-season.

Compared to other Cordilleran peoples, the Buguias villagers planted few varieties of rice. Each of the two major types, glutinous diket and nonsticky, red kintoman , boasted no more than three or four distinct strains. The growing conditions of each variety were considered roughly equivalent, although one slowly maturing cultivar had to be transplanted by December. Glutinous and non-sticky grains were usually mixed for eating and for the making of beer. The Buguias people knew of many different varieties planted by other Cordilleran peoples, and some of these they recognized as superior. But although they not uncommonly planted experimental fields, few new varieties proved successful. Especially desired was a lowland strain that would produce a crop in the cloudy wet season, but no planting ever proved successful.

Buguias residents continually enlarged their pond-field system through the American period. Wealthy traders and livestock breeders initiated most new construction, which they usually contracted out to the expert terrace engineers from Ifugao and Bontoc subprovinces. (The latter workers were acclaimed for their ability to lever large river boulders into terrace walls, while the former were noted for their skilled masonry with smaller stones.) Most

Buguias people thought that terraces built by local residents lacked the durability of those constructed by outside workers.

Animal Husbandry

Domestic animals provided the people of prewar Buguias with ample meat, but little else. Leather strips served as ropes and whole hides as sleeping mats, but even cattle skins were often patiently chewed and swallowed. A few individuals plowed with water buffalo, and the elite sometimes rode horses, but animal power was inconsequential overall. Meat was vital, however, and people labored to fashion a landscape that could yield abundant supplies. Houselot animals, such as hogs, foraged in uncultivated areas but depended primarily on agricultural produce. Cattle, horses, and buffalo, however, subsisted solely on the fodder of the human-created and maintained savannah.

Houselot Animals: Hogs and Chickens

Hogs, raised by all families, foraged daily in the open pasturelands. At night they returned through fenced runways to their pens, situated below each house. In the grasslands and pine savannahs they rooted for worms and grubs, fungus, and wild tubers. Those in the higher reaches of Buguias could roam as far as the kalasan, or cloud forest, well-stocked with acorns, fungus, and especially earthworms. On returning each evening they were fed boiled sweet potatoes and sweet-potato peels, pounded rice hulls and bran, kitchen garbage, and human waste. Both under- and oversized tubers were relegated to the swine; in most households, well over half of the crop went to the piggery. Hogs flourished in the rainy season, but during the annual drought the earth hardened and wild foods grew scarce, and the weakened animals suffered frequently from skin diseases.

In the American period a few individuals began raising lowland hogs, valued chiefly for their ability to gain weight on the raw sweet potatoes that the so-called native hog could scarcely digest. These animals were not ritually acceptable, however, precluding them from replacing the indigenous stock. Kikuyu grass, purportedly brought to Buguias by a teacher, was also introduced in this

period. The thick stolons of this aggressive exotic, which flourished in moist microhabitats, provided a fine year-round hog feed.

Other houselot animals occupied niches similar to that of swine. The average family owned some twenty chickens, while the wealthy might possess as many as two hundred. Chickens returned each night to roost in predator-secure pens or in trees, and foraged daily in the nearby pastures. All households kept dogs, primarily for their meat, feeding them bones, scraps, and, of course, sweet potatoes. And finally, a few individuals raised pigeons, ducks, and even geese.

Pasture Animals: Cattle, Water Buffalo, and Horses

Unlike hogs and chickens, pasture animals were the responsibility of men. The average man in prewar Buguias devoted most of his labor to pasturing horses, water buffalo, and especially cattle. Water buffalo, the only ritually sanctioned pasture animal, were prestigious but not numerous. They reproduced poorly in the cool environment, and surviving calves, completely helpless for three days, often succumbed to disease or were trampled by bulls. Horses were valued primarily for their meat, although a few wealthy men kept riding mounts. But horses did not thrive as well as cattle on the Buguias grazing regime, and were thus relatively rare. Goats were raised in even smaller numbers.

Cattle, horses, and buffalo remained at pasture day and night. They subsisted largely on the native forage, supplemented occasionally with old sweet-potato vines. The few corrals generally held stock only prior to transporting or butchering. During typhoons, men herded their animals into protected areas, sometimes putting them in crude shelters built on the leeward side of hills. Otherwise livestock wandered untended, although conscientious graziers checked daily to ensure that none had wandered away or "fallen off the mountain."

Cattle were provided salt every few days, although several small herds in eastern Buguias obtained salt directly from local springs. Men could assemble their stock by blowing a water-buffalo horn, each instrument having a distinct sound that the animals could distinguish. Buguias cowboys assisted with births and watched after

the young, especially the buffalo calves. Breeding received casual attention, although healthy bulls with propitiously placed cowlicks were favored as studs. Branding occurred only at the insistence of the American authorities.[3] Men easily recognized their own animals, and disputes arose only over calves delivered unattended in distant pastures.

Pasture Management

The so-called native cow of Benguet is a small, slowly maturing animal, optimally butchered at four years of age. Like the native hog, it is a fussy eater; several forbs unpalatable to the natives are readily eaten by introduced zebu crosses and so-called mestizo hybrids. But the Buguias pastoralists carefully managed their pastures to provide the grasses on which their stock thrived.

Themeda triandra (red oat grass), usually in association with Andropogon annulatus and Imperata cylindrica , dominated the savannah landscape of prewar Buguias (see Penafiel 1979). On the higher slopes and ridges scattered pines crowned the pastures, but only the more remote upper canyons supported trees thick enough to shade out the grass. Western range managers consider Themeda a mediocre if not poor feed, but to the Buguias pastoralists it was ideal.[4]Themeda responds well to fire (Crowder and Chheda 1982: 297), their primary range-management tool, and withstands reasonably heavy and continual grazing.

Buguias pastures grew lush in the wet season, but produced a watery low-protein forage. As protein increased in the early dry season, cattle fattened. December thus marked the optimum time for butchering and selling. Forage quality again diminished as pastures desiccated in February and March; fires might then be lit to stimulate new growth. In the late dry season many small springs would lapse, depriving cattle of several pasture zones. By March stock sometimes had to be hand-fed with cane-grass leaves, brought in from inaccessible ravines and slopes.

The savannah landscape of prewar Buguias was an anthropogenic environment, created and maintained by human intervention. Only continual labor could prevent reversion to woody growth. As burning allowed easy management, many pastures were annually torched, and even the more remote pine woods were occasionally

singed. But fire alone would not eliminate all undesired plants; in intensively managed pastures the Buguias people dug weeds by hand. Weed infestations intensified after the invasion, circa 1916, of the Mexican composite Eupatorium adenophorum.[5]Eupatorium , thriving in all microhabitats from dry, rocky slopes to boggy seeps, soon ranked as the foremost pest. Each plant had to be uprooted and burned, a task performed in prime pastures once or twice every year.

Grazing pressure itself helped maintain the savannah. In areas too steep for cattle but still occasionally burned, the cane grass Miscanthus sinensis dominated. Miscanthus decreases quickly if continually grazed, as its highly placed growth nodes are easily destroyed (Numata 1974:135). Cane swards could still survive, however, in remote and seldom-grazed pastures.

Although most pastures were held in common, few were overgrazed. Buguias men knew well the carrying capacities of their prime pastures, and if these were exceeded community pressure fell on the offending individual. Some persons believed in naturally—or supernaturally—enforced stocking limits. One story recounted how the ancestors had established the limit of a certain pasture at ten animals; after a greedy man added two more, the correct ratio was restored when the new animals simply "fell off the mountain." Carrying capacity estimations in prime pastures were made for roughly discrete areas, separated by natural barriers (steep slopes and ravines) and sometimes by fences. Distant grazing lands were more loosely monitored. Cattle could not even reach certain remote grasslands unless trails were first cut across intervening slopes. This was risky, as well as labor-consuming, since animals periodically slipped from even the best-graded passages. But stock could sometimes range far from central Buguias, finding greener fields perhaps, but also adding to the cowboys' burdens.

An elaborate fence network marked off cultivated areas from the open pastures. Cattle, hogs, and water buffalo continually threatened and occasionally devastated umas, pond fields, and dooryard gardens. Even chickens could destroy rice-seed beds. Old men remember that making fences and maintaining them were their most arduous tasks. The kind of fence chosen for a given field depended on the materials at hand, the desired level of permanence, and the specific animal threat. Durable stone walls were fa-

vored for larger home gardens, more intensively cultivated umas, and rice terraces. For most dry fields, pine fences, sometimes reinforced with hardwood brush, sufficed. Owing to wet-season rot, such fences demanded constant repair. Where wood was not easily accessible, Buguias men usually built sod walls with facing ditches. On the steepest slopes, living fences of agave functioned well with little maintenance. Complex fence networks of pine, stone, and bamboo protected houselot gardens, especially vulnerable to residential swine.

The Harvest of Uncultivated Lands

Uncultivated plants and wild animals also helped support the people of prewar Buguias. Gathered plants and hunted animals, while never forming staples, provided incidental protein and vitamins as well as welcome culinary variation. The production of fuel, fiber, and building materials from uncultivated lands, however, was absolutely essential.

Hunting, Fishing, and Insect Gathering

The hunting of deer and wild hogs, the only large game, demanded skill, patience, and sometimes daring. Although neither creature inhabited central Buguias, deer roamed the more remote pine forests and savannahs, and wild hogs populated the higher oak woodlands. A few expert spear-wielding hunters followed trained dogs in pursuit of game, but most men preferred sedentary techniques. Some excavated pitfall traps alongside animal trails, rendering them deadly with sharpened sticks. The easiest method of deer capture was to burn an area of brush and then hide nearby until the animals arrived to lick the mineral-rich ash. Few men were versed in the more elaborate hunting techniques, but those who were could provide ample meat for their families and their neighbors.

Smaller mammals, such as civets and rats, were both abundant and troublesome. Civets raided houselot gardens, eating even coffee berries and occasionally killing chickens, while rats feasted on most crops. Hunting these animals thus protected other food

sources and provided meat as well. Snares were usually employed, but young men enjoyed small-game hunting at night using dogs as trackers and pine torches for illumination.

Birds, ranging from large waders to tiny perchers, provided special delicacies. Buguias villagers caught migratory birds in season and residents the year round. Specialized snares were employed for different species at different times of the year; passive nooses sufficed in favorite roosts, while bent-stick spring traps snagged the warier species. The most plump and plentiful of the avian prey were the quail of the pasturelands, the snipes of the rice fields, and the wild chickens of the higher forests.

Most persons enjoyed fishing. The plentiful sculpins were sometimes netted by women, but were more often trapped by young men who would divert a river channel, thereby exposing all manner of life in the desiccated bed. Men and boys captured meaty eels with nets, hooks, and in river diversions. In rice fields and irrigation ditches, mud fish provided children with easy prey. Amphibians were plentiful in select seasons: tadpoles crowded the riverbed in March and April, and adult frogs could be captured at night, having first been blinded by torch light, in November and December.

Favored invertebrates spiced the seasonal fare as well. Fatty termites were funneled into water pots as they emerged for nuptial flights following the first rains. In the early years of this century an even greater bonanza occasionally appeared in the form of locust swarms. Buguias residents followed the insects for many miles, sometimes returning with several bushels to be dried and consumed at leisure. Lowland locust eradication programs sponsored by the U.S. were little appreciated in Buguias. More regular if less abundant invertebrate morsels included the mole crickets of the rice fields, the three varieties of rice-field snails, and the various river-dwelling water bugs. A few old men specialized in honey gathering, discerning hive locations by patiently observing the flights of bees. Honey itself was a delicacy, but wax was even more appreciated as a fiber coating.

The pursuit of wild creatures, other than deer and hogs, was—and still is—primarily an activity of young, unmarried men. Buguias bachelors still spend hours diverting streams for a meager catch of tadpoles, sculpins, and water bugs. This is not "optimal

foraging" so much as simple entertainment. In the prewar period, poorer villagers found intensification of sweet-potato patches much more rewarding than hunting or fishing. But wild meat—some of it, such as tadpole flesh, very strong of taste—did provide welcome variation to an otherwise bland diet.

Wild Plant Foods

Prewar Buguias was endowed with several wild fruits and vegetables. Brambleberries and huckleberries were abundant in pastures and woodland clearings, and wild guavas grew thick in several dry grasslands. Children gathered most fruit, consuming the bulk forthwith but usually bringing some home for their families. The foremost wild vegetable was Solanum nigrum , a weed of abandoned dry fields. Buguias residents collected wild tomatoes and Capsicum peppers (both exotics), as well as watercress. They regarded mushrooms highly and sought them diligently, gathering over twenty different varieties, some in sufficient quantity for drying. But perhaps the most essential wild "food" plant was the cosmopolitan weed Bidens pilosa , which formed the base of bubud , the yeast cake used in making rice beer.

Only in famines were wild foods essential. A delay of the southwest monsoon could bring food shortages, and real hunger would ensue if drought persisted, as it once did, until July. A prolonged typhoon could also spoil the sweet-potato crop, thus depleting the essential food stock. Even a rat infestation could cause a food deficiency. During times of severe want, the Buguias people consumed the tubers of a drought-adapted pasture legume and the pithy centers of Miscanthus canes. In the harsh famine at the end of World War II, some individuals retreated to the oak forest to gather acorns. The standby food of hard times, however, was taro. Wild taro, common in higher elevation seeps, was edible if leached, and several varieties of cultivated taro survived well through the worst storms and droughts.

Non-Food Products

The most significant use of wild plants was for nonfood products. Several wild legumes and the semiwild (and exotic) agave yielded

fibers for rope and thread. In the early American period, poorer residents pounded the bark of several different trees into fabrics suitable for loincloths and skirts. Bark clothing disappeared only in the 1930s, when it was universally replaced by cotton cloth. Wild grasses served as thatch, and a variety of vines fastened house rafters and fences. Connected bamboo lengths formed water conduits, and individual sections functioned as canteens. Artisans carved hardwood, obtained from small groves in stream depressions, into bowls, handles, and durable tools. And finally, the versatile Miscanthus cane served in all manner of light construction.

But pine wood overshadowed all other hinterland products. Straight-bole trees, found on favored northern exposures, provided lumber. Hand-split pine planks sufficed for house construction in the early period, but by the 1920s boards sawn by itinerant Northern Kankana-ey workers were commonplace. Most fences (planks and posts) were pine, and hollowed pine logs formed conduits over stream crossings in the larger irrigation systems. Pine wood also fueled the hearths and heated the homes of prewar Buguias. The villagers usually derived their firewood from the more gnarled trees of the rocky slopes and southern exposures. Smoldering fires gave warmth when temperatures dipped to near freezing in December and January and helped counter the wet season's damp. Finally, metalworks were fueled by charcoal, derived largely from pine branches and bark.

The most valuable pine product was perhaps saleng , the resinous heartwood of old or prematurely injured trees. Saleng provided illumination: torches for outside activities, and slender "candles" for the home. The Buguias people also treasured such wood for its resistance to rot; only saleng posts could support a house for more than a few rainy seasons, or serve at all in fencing.

The inhabitants of prewar Buguias did not consider wood procuring to be an especially onerous chore. Pines were still plentiful and large, and a variety of labor-saving techniques were employed. Men and older boys usually secured a year's supply of fuel in the dry season; left to desiccate in the field the wood would lose roughly half of its weight before being carried. On steep slopes logs were shunted down gravel shoots to more accessible sites, if necessary affixed to boulders for extra weight. Trees closer to settlements

were more casually, and gradually, harvested by boys who would climb them to lop off branches for fuel.

Vegetational Change and Agricultural Intensification

Since human subsistence in prewar Buguias relied on wild as well as cultivated lands, one may question just how "natural" the uncultivated lands of Buguias were. And since people continually intervened in natural processes, we must also ask whether the re-configurations they wrought were truly sustainable. The steady growth of human numbers in particular suggests that we must be cautious in proclaiming the prewar subsistence system as ultimately ecologically benign.

Vegetational Change: the Kowal Thesis

Norman Kowal (1966) argues that prior to the advent of swidden cultivation and associated burning, the Cordillera was entirely wooded. Lowland "rainforest" grew below 1,200 meters, the zone between 1,200 and 1,600 meters supported a "submontane" forest of mixed hardwoods (containing pine only on rocky outcroppings and slide scars), and above 1,600 meters grew the true oak-dominated montane forest, called the kalasan in Buguias. Following human disturbance, this series was replaced by one containing Imperata grassland in the lowest reaches, Themeda grassland from approximately 1,000 to 1,400 meters, pine savannah (botanically identical with the Themeda grasslands except for the addition of scattered pines) between 1,200 and 2,000 meters (the original hardwoods surviving in stream depressions), and montane oak forest above 2,000 meters. Jacobs (1972) argues that on the very highest level, the summit of Mount Pulog, fires caused by humans (associated with camp sites rather than swiddens) allowed a grassland dominated by dwarf bamboo to replace the oak association.

Oral environmental histories gathered in several Benguet municipalities support Kowal's thesis. Throughout the province, even in now treeless areas, settlement stories tell of wandering hunters building their homes in "jungle" areas. Without further empirical

Figure 1.

The Buguias Environment: A Cross Section through the Southern Cordillera. Vegetation zones modified from Kowal (1966).

work (palynological analysis, for example), any discussion of vegetational change under human pressure must remain tentative. The following pages thus outline the more likely pathways of anthropogenic vegetation change in prewar Buguias.

Vegetational Change in Buguias

In present-day Buguias, montane hardwoods occupy only the northern exposures of steep side canyons. According to Kowal's model, hardwoods would have dominated the prefire landscape of Buguias, with pine restricted to dry and rocky sites. Such pockets of seasonal aridity are widespread in this area, however, and many steep southern exposures may never have supported montane forests. Although Buguias lies only sixteen degrees north of the equator, slope aspect is significant since drought occurs when the sun is well within the southern hemisphere. Furthermore, fire, which universally favors pine, can be sparked by the lightning that sometimes accompanies the year's first storms. Thus the vegetation of Buguias in earlier times was probably a mosaic of pine savannah and montane forest.

The early agriculturalists probably chose sites in the fertile montane forests for their first swiddens. With long initial fallow, forest vegetation would have been able to regenerate, but with intensification, Miscanthus cane would have spread. Indeed, in both the Ifugao culture region and in the Bot-oan area immediately east of Buguias, Miscanthus swards dominate swidden fallows (see Lizardo 1955). But with the introduction of cattle in the later Spanish period, Miscanthus would have declined while pasture grasses increased. As the fire- and grazing-adapted savannah spread, the montane forest would have retreated to ravines inaccessible to flame. In the more intensively grazed areas of the lower valley, pine would have declined, as yearly burning inhibited its regeneration. In the highest reaches—those above 2,000 meters—perennial saturation would have protected the oak forest, but even here fire could burn a few meters into the woodland each year, allowing a progressive march of grassland vegetation (Jacobs 1972). But for the most part, the higher oak forest would have remained little modified by human activity, except for the few areas cut for uma

fields and the selected ridgetops annually cleared for the nocturnal hunting of migratory birds.

The anthropogenic savannah was vital for prewar Buguias subsistence; it afforded graze for the herds and pine wood for fuel, construction, and illumination. But pine regeneration may have been inadequate to sustain this regime in the long run. Pine seedlings require some five to ten fire-free years to become established, and many pastures were burned annually. Most lower-elevation Ibaloi districts had already been deforested well before the turn of the century (Semper 1862 [1975]), owing perhaps to lowered pine vitality in warmer climes (Lizardo 1955) but probably also to the longer history of Ibaloi pastoralism. Certain Kankana-ey areas, especially those, like Mankayan, that supported an indigenous mining and smelting industry, were also deforested long ago (Marche 1887 [1970]). Whether prewar subsistence patterns would have truly allowed a sustainable pine harvest is an open question.