Preferred Citation: Christ, Carol T., and John O. Jordan, editors Victorian Literature and the Victorian Visual Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft296nb16b/

| Victorian Literature and the Victorian Visual ImaginationEdited by Carol T. Christ |

Preferred Citation: Christ, Carol T., and John O. Jordan, editors Victorian Literature and the Victorian Visual Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft296nb16b/

Contributors

JAMES ELI ADAMS is Assistant Professor of English and Victorian Studies at Indiana University and co-editor of Victorian Studies . He has published a number of articles on Victorian literature and culture and is completing a book entitled Bold against Himself: Rhetorics of Victorian Masculinity .

MIRIAM BAILIN is Assistant Professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis. Her Sickroom in Victorian Fiction: The Art of Being Ill was published by Cambridge University Press in 1994. She is working on a literary and cultural history of Victorian pathos.

SUSAN P. CASTERAS is Curator of Paintings at the Yale Center for British Art and has organized many exhibitions of Victorian art, including A Struggle for Fame: Victorian Women Artists and Authors; Pocket Cathedrals: Pre-Raphaelite Book Illustrations; Victorian Childhood; and Richard Redgrave . A member of the History of Art faculty at Yale, she has published extensively in the field of Victorian art, including books entitled English Pre-Raphaelitism and Its European Contexts, Images of Victorian Womanhood in English Art, and English Pre-Raphaelitism and Its Reception in America in the Nineteenth Century as well as numerous articles and essays in Victorian Studies, the Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies, and elsewhere.

CAROL T. CHRIST is Professor of English and Provost and Dean of the College of Letters and Science at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of The Finer Optic: The Aesthetic of Particularity in Victorian Poetry and Victorian and Modern Poetics and the editor, with George Ford, of the Victorian section of the Norton Anthology of

English Literature . She is at work on a project on death in Victorian literature.

GERARD CURTIS is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Essex and lectures in art history at Sir Wilfred Grenfell College (Memorial University), Newfoundland. He is the author of "Ford Madox Brown's Work: An Iconographical Analysis" and "Dickens in the Visual Market." Currently he is researching the relationship of image to word in Victorian culture.

JUDITH L. FISHER is Associate Professor of English at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. She is the author of "Annotations to the Art Criticism of William Makepeace Thackeray" and co-editor of When They Weren't Doing Shakespeare: Essays in Nineteenth-Century British and American Theater . She has recently finished a study of language and perception in Thackeray's art criticism and fiction, titled Thackeray's "Perilous Trade."

JENNIFER M. GREEN is Assistant Professor of English at George Washington University. Her essays and reviews have appeared in the Journal of Narrative Technique, Victorian Literature and Culture, Victorians Institute Journal, and Victorian Studies, among others. She is completing a book on photography and representation.

ELLEN HANDY is an art historian and critic and teaches at LaGuardia College, CUNY. Her research encompasses many aspects of nineteenth- and twentieth-century art, particularly photography. Most recently, she organized an exhibition for the Chrysler Museum titled Pictorial Effect/Naturalistic Vision, which presented the work of two Victorian photographers, H. P. Robinson and P H. Emerson.

MARGARET HOMANS is the author of Bearing the Word: Language and Female Experience in Nineteenth-Century Women's Writing (1986) and of essays on nineteenth-century literature and on contemporary feminist theory. The essay in this volume is part of a book project on Queen Victoria and Victorian culture.

SUSAN R. HORTON'SDifficult Women, Artful Lives: Olive Schreiner and Isak Dinesen, In and Out of Africa is scheduled to appear in the fall of 1995 from the Johns Hopkins University Press. Her previous publications include Interpreting Interpreting, The Reader in the Dickens World, Thinking through Writing, and various essays on literary theory, literacy, and Dickens. A past president of the Dickens Society, she is Professor and former Chair of English at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

AUDREY JAFFE , Associate Professor of English at Ohio State University is the author of Vanishing Points: Dickens, Narrative, and the Subject of Omniscience (University of California Press, 1991) and of essays on Victorian literature. She is at work on a book about sympathy and representation in nineteenth-century British literature and culture.

JOHN O. JORDAN is Associate Professor of Literature and Director of the Dickens Project at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He has published articles on several Victorian writers, including Dickens, as well as essays on modern African literature and Picasso. He is co-editor, with Robert L. Patten, of Literature in the Marketplace: Nineteenth-Century British Publishing and Reading Practices, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

ROBERT M. POLHEMUS is Howard H. and Jesse T. Watkins University Professor in English at Stanford University. He is the author of Erotic Faith: Being in Love from Jane Austen to D. H. Lawrence; Comic Faith: The Great Tradition from Austen to Joyce; The Changing World of Anthony Trollope, and, most recently, an author and co-editor of Critical Reconstruction: The Relationship of Fiction and Life . He is at work on a book about parent-child relationships in fiction, faith in the child, and representations of children in literature and art.

LINDA M. SHIRES , Associate Professor of English at Syracuse University, is the author of numerous essays on Victorian literature and of British Poetry of the Second World War (1985), co-author of Telling Stories: A Theoretical Analysis of Narrative Fiction (1988), and editor of Rewriting the Victorians (1992). A 1993–94 Guggenheim Fellow, she is currently writing a book on careers in the Victorian literary marketplace and editing the new Penguin edition of The Trumpet Major .

RICHARD L. STEIN is the author of The Ritual of Interpretation: The Fine Arts as Literature in Ruskin, Rossetti, and Pater (Harvard University Press, 1975) and Victoria's Year: English Literature and Culture, 1837–1838 (Oxford University Press, 1987) along with other writing on nineteenth-century British literature and the fine arts. He is working on a study of Victorian iconography. He has been a member of the faculty at Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley, and is currently Professor and Head of the Department of English at the University of Oregon.

Author most recently of Reading Voices: Literature and the Phonotext and of numerous articles on Victorian fiction and film, GARRETT

STEWART is James O. Freedman Professor of Letters at the University of Iowa.

RONALD R. THOMAS is Associate Professor of English and Chairman of the Department at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. Among his publications are Dreams of Authority: Freud and the Fictions of the Unconscious (Cornell University Press, 1990) and a number of articles on the novel, including studies of Dickens, Collins, Stevenson, and Beckett. He is currently writing Private Eyes and Public Enemies: The Science and Politics of Identity in American and British Detective Fiction, a book investigating the genre's involvement with emerging technologies of criminal identification in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition to teaching at the University of Chicago, he has been a Mellon Faculty Fellow in the Humanities at Harvard University.

Introduction

Carol T. Christ and John O. Jordan

Jonathan Crary, in his book Techniques of the Observer, describes a reorganization of vision in the nineteenth century, a change that created a new model of the observer, embodied in aesthetic, cultural, and scientific practices.[1] Identifying a number of new optical devices invented near the beginning of the century, Crary argues that they indicate a profound change in ideas of seeing central to the construction of modernity. Crary concentrates his analysis on devices that create optical illusions: the thaumatrope, in which a card having on its opposite faces different designs is whirled rapidly to combine the designs in a single picture; the phenakistoscope, in which a disk with figures on it representing different stages of motion is whirled rapidly to create the impression of actual motion; the zoetrope and the stroboscope, later developments of the phenakistoscope; the kaleidoscope; the diorama; and the stereoscope, which combines pictures taken from two points of view to create a single image with the illusion of solidity or depth. One can add to Crary's list a number of other nineteenth-century optical inventions that projected, recorded, or magnified images: the camera lucida, which projects the image of an object on a plane surface; the graphic telescope, which adds magnification to the operation of the camera lucida; the photographic camera; the binocular telescope; the binocular microscope; the stereopticon, a nineteenth-century precursor to the slide projector; and the kinetoscope, an early motion picture projector.

Much in the standard literary history of the nineteenth century supports Crary's claim that an analysis of vision gives crucial insight into the way the Victorians constructed experience. Nineteenth-century aes-

thetic theory frequently makes the eye the preeminent organ of truth. John Ruskin's Modern Painters, with its detailed descriptions of clouds, water, rocks, air, and trees, provides the most encyclopedic example of the authority many writers vested in the eye. "Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy, and religion—all in one."[2] In "The Hero as Poet," Carlyle writes, "Poetic creation, what is this too but seeing the thing sufficiently? The word that will describe the thing follows of itself from such clear intense sight of the thing."[3] Likewise in "The Function of Criticism at the Present Time," Arnold describes the ideal in all branches of knowledge: "to see the object as in itself it really is." The effort of the Pre-Raphaelites to represent religious subjects with minute attention to visual detail reflects a similar faith in seeing.

Poetic theory, accordingly, emphasized what John Stuart Mill called the poet's power of "painting a picture to the inward eye."[4] In his review of Tennyson's first volume of poems, Arthur Henry Hallam defines the "picturesque poet," "whose poetry is a sort of magic, producing a number of impressions, too multiplied, too minute, and too diversified to allow of our tracing them to their causes because just such was the effect, even so boundless and so bewildering, produced on their imaginations by the real appearance of Nature."[5] A character in Mrs. Gaskell's Cranford, enthusiastically praising the visual accuracy of Tennyson's poetry, says it was Tennyson who taught him that ash buds are black in the beginning of March. As Tennyson's legendary fidelity to visual detail suggests, word painting, or what Hallam terms the picturesque, is central to nineteenth-century poetic style. Biographical evidence abounds of poets' quests for visual experience—Wordsworth's hiking tours, Hopkins's journals, Tennyson's falling to his knees in the grass to observe a rose through a dragonfly's wings. Furthermore, there is a close partnership between poetry and painting. "Ut pictura poesis" could stand as a motto not only for Rossetti's paired sonnets and pictures but also for the large body of Victorian poetry about paintings.

The visual experience important to the poetics and poetry of the nineteenth century was also valued in the novel. In "The Art of Fiction" Henry James provides what could stand as a summary statement of the nineteenth-century novel's attempt to picture what it represents:

The air of reality (solidity of specification) seems to me to be the supreme virtue of a novel—the merit on which all its other merits . . . helplessly and submissively depend. If it be not there they are all as nothing, and if these be there, they owe their effect to the success with which the author has produced the illusion of life. . . . It is here in very truth that he competes

with life; it is here that he competes with his brother the painter in his attempt to render the look of things, the look that conveys their meaning, to catch the color, the relief, the expression, the surface, the substance of the human spectacle.[6]

Similar moments, in which the novelist defines his or her art in terms of painting, occur in the works of many nineteenth-century writers. George Eliot's famous chapter in Adam Bede in which she compares her art to Dutch painting provides an example—the pictures "of an old woman, bending over her flower pot, or eating her solitary dinner, while the noonday light, softened perhaps by a screen of leaves, falls on her mob-cap, and just touches the rim of her spinning wheel, and her stone jug" or the village wedding, "where an awkward bridegroom opens the dance with a high-shouldered broad-faced bride, while elderly and middle-aged friends look on, with very irregular noses and lips."[7] That Eliot's novel only partially embodies the aesthetic ideal she describes here does not lessen the significance of the visual analogue she chooses. Or we can turn to Hardy, who finds in the 1880s in impressionist painting a model to which he aspires in his fiction. He writes in his journal, "The impressionist school is strong. It is even more suggestive in the direction of literature than in that of art . . . the principle is, as I understand it, that what you carry away with you from a scene is the true feature to grasp."[8] Beyond finding analogues to their work in painting, novelists formed actual partnerships with illustrators. Dickens's work with Phiz and Cruikshank and Thackeray's design of his own illustrations demonstrate the closeness between verbal and visual art in the nineteenth-century novel.

This brief account of nineteenth-century visual culture establishes its importance; the meaning of all its prominent features is far harder to assess. Two very different accounts have been given of the history of the visual imagination in the century. One has stressed the predominance of realist modes of representation, culminating in photography and, in the twentieth century, the cinema. The other has emphasized a break with realism, an increasingly subjective organization of vision leading to modernism.[9] Often the same writer can be used to support either model. Ruskin's minute cataloguing of the truth of rocks and trees and his many declarations of the necessity of accurate vision seem to place him squarely in the objectivist camp, yet he erects the argument of Modern Painters in defense of Turner. Similarly, George Eliot repeatedly represents herself as a scientist mirroring the reality she depicts, yet she represents perception as necessarily individual and subjective. Likewise the optical inventions of the century do not support a single model.

Jonathan Crary argues that the optical devices he describes show a new subjective model of the observer emerging in the early nineteenth century, but the photograph, the binocular telescope, and microscope seem to tell a different story, in which optical inventions extend our powers of objective observation.

A comprehensive study of visuality in the nineteenth century, one that would try to understand the relationship of what seem to be different constructions of the observer, has yet to be written. The only two books that attempt a comprehensive argument are Crary's account and Martin Meisel's Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England .[10] Whereas Crary bases his argument on optics, Meisel identifies formal similarities between fiction, painting, and drama, which cut across medium and genre and, he argues, constitute a common nineteenth-century style. This style, according to Meisel, unites pictorialism with narrative to create richly detailed scenes in painting, in theater, and in the illustrated novel, scenes that at once imply the stories that precede and follow and symbolize their meaning.

With the exception of Meisel, no critic has tried to give a general account of visuality in nineteenth-century British art and literature. There are, of course, hundreds of studies that illuminate various aspects of the nineteenth-century visual imagination—studies of the image or description in individual writers or groups of writers, studies of painting or photography, book illustration, the sister arts, landscape, the picturesque the list could go on.[11] But few writers have attempted to link these fields of inquiry to develop a comprehensive account.

The time is now ripe for such an attempt. The development of interdisciplinary scholarship has created useful models for moving across different fields of inquiry and discourse. Influential theoretical formulations by Lacan (on the gaze), Foucault (on surveillance), and Debord (on spectacle) have given new impetus to the study of vision and visuality in a variety of cultural and historical contexts, in eluding literary studies.[12] The groundbreaking work of Roland Barthes on popular culture and on photography has encouraged others to read visual images as "texts," using the tools of semiotics and ideological critique.[13] Psychoanalysis, feminism, film theory, and media studies have all contributed to our understanding of what Martin Jay calls the "scopic regimes of modernity," a phrase he uses to designate the contested terrain of visual theories and practices since the Renaissance.[14] Practitioners of the "new art history" draw readily on literary theory as well as on literary texts in developing their arguments,[15] while the recently founded journal Word and Image shows an interest in the relationship of pictorial

and verbal representation. Furthermore, post-structuralist criticism has motivated a concern with analyzing the representational status of the image in literature and in literary theory, complicating, even deconstructing, the opposition between objective and subjective, mimesis and imaginary construction.[16]

The essays we have collected for this volume concern the relationship between the verbal and the visual in the nineteenth-century British imagination. We have limited our compass to the Victorian period, and we have organized the volume around topics central to an analysis of visuality and the Victorian imagination—the relationship of optical devices to the visual imagination, the role of photography in changing the conception of evidence and of truth, the changing partnership between illustrator and novelist, the ways in which literary texts represent the visual. Each of the essays either addresses a particular relationship of the Victorian visual imagination to Victorian literature or shows how the visual is consequential for studies of Victorian writing. Together they begin to construct a history of seeing and writing in the Victorian period.

From this history, a number of conclusions emerge. Primary among them is that neither an exclusively subjective nor an exclusively objective model provides a sufficient explanation for the Victorian idea of visual perception. Rather, the Victorians were interested in the conflict, even the competition, between objective and subjective paradigms for perception. The ideas that most powerfully engaged their imagination were those such as perspectivism or impressionism that could simultaneously accommodate a uniquely subjective point of view and an objective model of how perception occurs. George Eliot's famous image of the pier glass in Middlemarch provides a good example of such an accommodation:

An eminent philosopher among my friends, who can dignify even your ugly furniture by lifting it into the serene light of science, has shown me this pregnant little fact. Your pier-glass or extensive surface of polished steel made to be rubbed by a housemaid, will be minutely and multitudinously scratched in all directions; but place now against it a lighted candle as a centre of illumination, and lo! the scratches will seem to arrange themselves in a fine series of concentric circles round that little sun. It is demonstrable that the scratches are going everywhere impartially, and it is only your candle which produces the flattering illusion of a concentric arrangement, its light falling with an exclusive optical selection.[17]

Pater's impressionism, most powerfully articulated in the conclusion to The Renaissance, provides another example of a model of perception that

combines scientific objectivism with a personally singular subjectivism. He begins his analysis by representing physical life as "a combination of natural elements to which science gives their names." These elements are in perpetual motion in a set of processes, "which science reduces to simpler and more elementary forces." Human access to this world of elements and processes—the scratches on the pier glass, as it were, in Eliot's metaphor—can only come through the individual's impression, his or her candle. Thus, Pater observes, "The whole scope of observation is dwarfed into the narrow chamber of the individual mind."[18]

The optical instruments so popular among the Victorians demonstrate a similar tension between objective and subjective models of vision. Susan Horton's essay on optical gadgetry and on the representation of seeing in Dickens, which begins this collection, provides a rich analysis of the competition between Romantic and empirical conceptions of vision in the Victorian period. Her essay leads to the insight that optical gadgets were not arrayed on one side or the other of this conflict. She shows that for Dickens they provided a means to contemplate the conflict, indeed, to experience it. Like Eliot's pier glass, like Pater's impressionism, optical gadgets used science to derive a subjective spectacle.

As Horton's essay suggests, the question of what the visible reveals fascinated and preoccupied the Victorians. A second conclusion that emerges from this collection of essays is the importance of the visible trace as evidence, both in broad empirical terms and in a narrower legal and judicial sense. We all have in our stock of Victorian images the picture of Sherlock Holmes and his magnifying glass. In his essay "Making Darkness Visible," Ronald Thomas calls Holmes "the essential Victorian hero who is known above all for his virtually photographic visual powers." Holmes, Thomas argues, seeks "to make darkness visible . . . to recognize the criminal in our midst by changing the way we see and by redefining what is important for us to notice." Holmes thus also shows the tension between uniquely personal and scientifically determined observation. Such interest in the visible clue could paradoxically lead to a greater emphasis on circumstantial evidence than on an eyewitness account. In Strong Representations: Narrative and Circumstantial Evidence in England, Alexander Welsh argues that plots centered on carefully managed circumstantial evidence, "highly conclusive in itself and often scornful of direct testimony," constituted the most prominent form of narrative in the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[19] Welsh's argument might seem to contradict the importance we are attributing to the visual because circumstantial evidence does not derive from direct

visual experience of the event. On the other hand, circumstantial evidence often derives from a visible trace. It thus shows the Victorians' fascination with the way the visible could reveal events of which we have no firsthand visual knowledge.

This interest in visual knowledge in part motivated the pictorial style that Martin Meisel has so exhaustively and richly detailed. A number of essays in this collection confirm the collaboration between narrative and picture that Meisel defines as the matrix of Victorian style. Miriam Bailin's analysis of ekphrasis in Tennyson's Enoch Arden, Judith Fisher's account of the uneasy partnership between image and text in Thackeray, Richard Stein's essay on urban iconography, Susan Casteras's examination of paintings depicting the urban poor, Robert Polhemus's reading of John Everett Millais's painting The Woodman's Daughter together demonstrate how consistently the Victorians pictorialized narrative and made pictures tell a story.

This partnership is not stable throughout the period, however. The early Victorian novel reflects a relatively homogeneous pictographic culture in which text and illustration carry equal weight. This complementary relation between text and illustration is described by two essays, by Gerard Curtis and Judith Fisher, at the beginning of our collection. By the end of the period, however, this partnership no longer existed, disrupted in part by the advent of photography, whose representational claims differed from those of painting and drawing. Curtis argues that the harmonious relationship between writing and drawing, or between pen and pencil, deteriorated gradually during the century until it was destroyed by photography, which replaced the pen illustration and wood-block print as the novel's visual analogue for truth and communicative value. Late-Victorian fiction, as Garrett Stewart argues in the last essay of the collection, reverses the tendency of earlier writing to move from the verbal to the visual, emphasizing instead the textuality of the visual image and leaving fiction less firmly attached to its visual analogues. The pictorial style that Meisel claims as characteristic of the age has been radically altered.

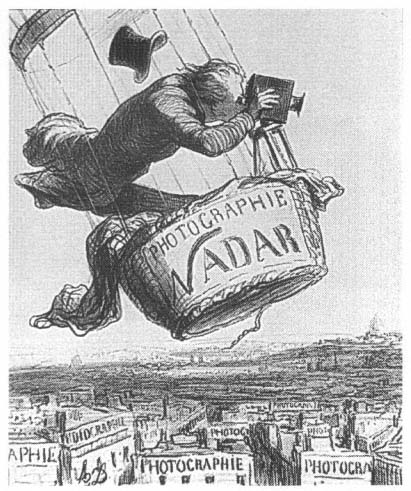

As both Curtis and Stewart observe, the advent of photography plays a central role in changing the relationship between picture and text. Although we group the essays specifically on photography, it plays an important role in many of our authors' arguments. Because the photograph seemed to offer a transparent record of the truth, it assumed a representational authority that rivaled that of text and of graphic art. Its transparency, however, was often illusory. As both Jennifer Green and Ellen Handy show in their essays, the photographer carefully composed

his pictures to focus on what was important to his design and to exclude what he wished to repress. Although photography in many ways initiated and motivated a break with earlier Victorian visual culture, its tensions between objective and subjective models of vision paradoxically resemble those of that culture. The very claims that the photographer could make for the transparency of representation, however, increased his power to mythologize the elements he presented.

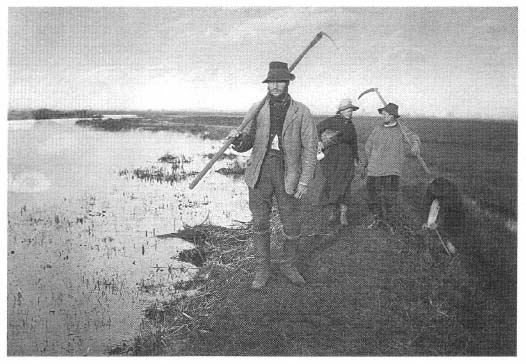

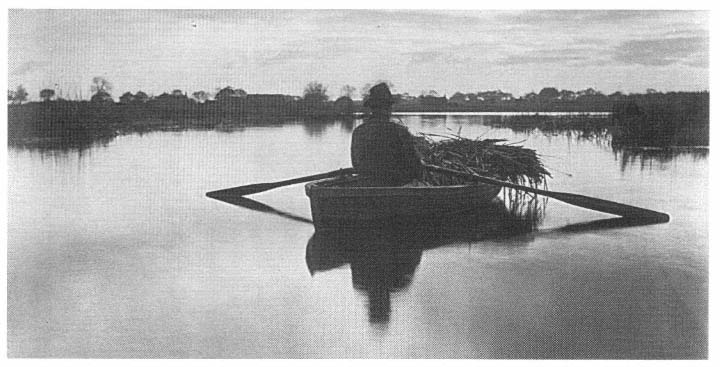

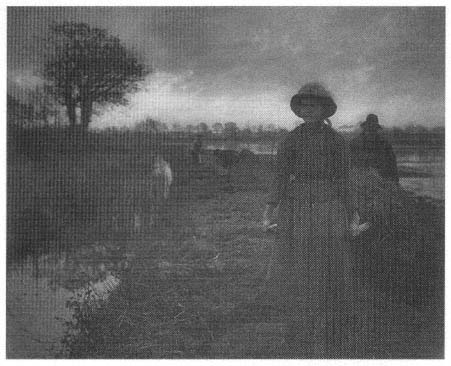

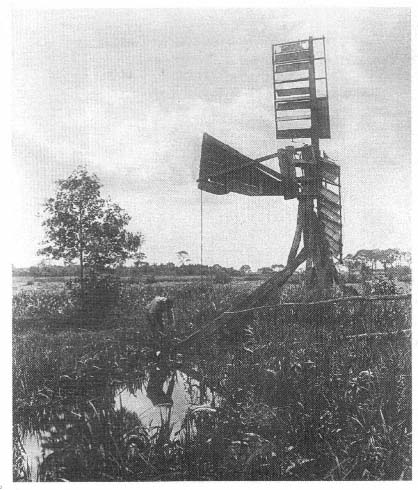

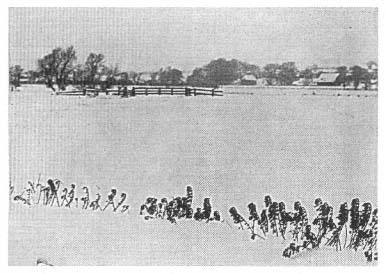

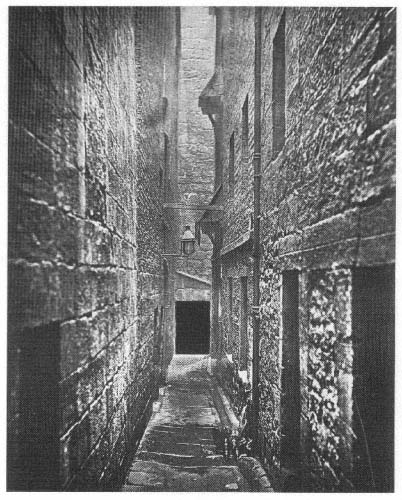

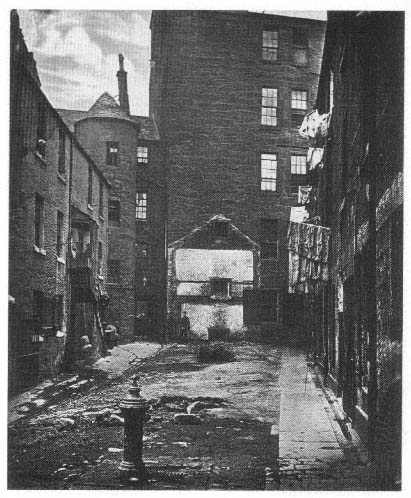

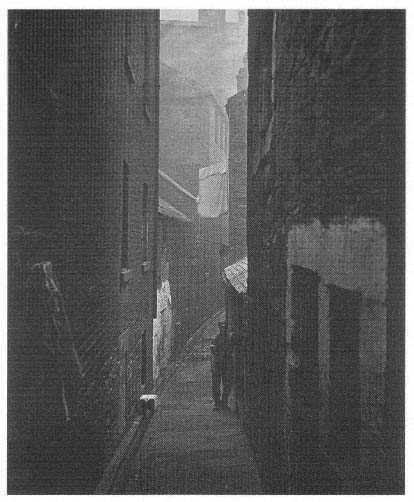

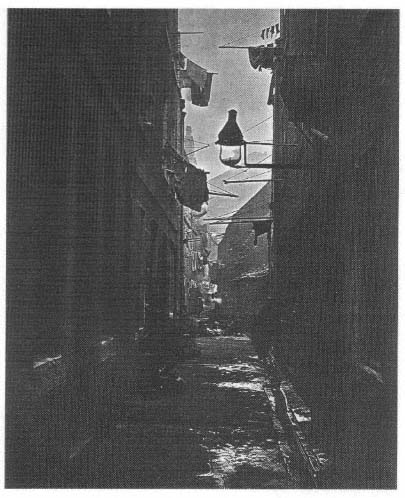

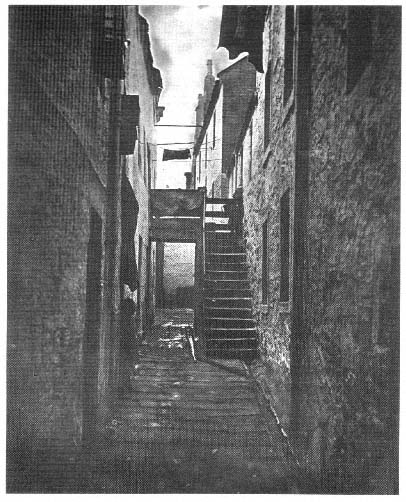

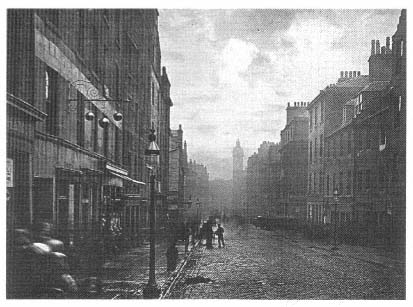

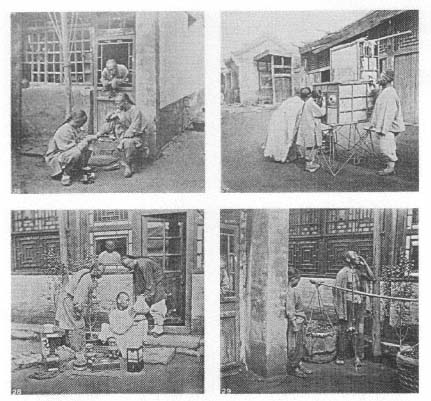

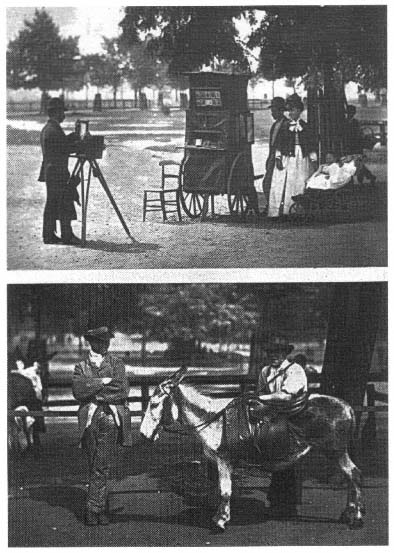

In its ability to construct a social mythology, photography became an important tool for mapping different social worlds. Because it claimed documentary power, photography could construct, classify, and build a relationship to images from exotic social worlds, whether those of the urban poor, foreigners, or even criminals. A number of our essayists demonstrate this use of the camera—Handy in Thomas Annan's photographs of the Glasgow slums; Stein in Adolphe Smith's and John Thomson's collection of texts and photographs, Street Life in London; Green in P. H. Emerson's photographs of the Norfolk Broads; and Thomas in police photography. As Thomas observes, the notion of the photograph as evidence and authentication allowed it to become not only a tool of social knowledge but a weapon enabling social control.

The social functions photography assumed depended in part on transformations in the media—the ease of mechanical reproduction, the prevalence of cheap printing. Readily available and easily reproduced, the photograph transformed the social function of the portrait. What had been a declaration of a socially privileged identity could become an instrument of control and detection and a product for commercial distribution. Public figures could widely distribute images and thus construct an identity in new ways. In their essays, Margaret Homans, Linda Shires, and James Adams all analyze the public figure as a spectacle. The new possibilities of being seen in photographs, often reproduced in print media, created new ways of building power and significance. Even the ideal of the sincere, unselfconscious writer, as Shires and Adams show, involved the author in a theatrical manipulation of his or her image. The author could use the media to commodify his own life in a seemingly unprecedented manner, creating images of identity as a spectacle that could be widely reproduced.

As Susan Horton observes, the nineteenth century devised rationales to legitimate spectatorship as a dominant cultural leisure-time activity. Although the interest in the spectator seems to take its motivation from the optical gadgetry that so fascinated people of the period, it had a far broader cultural importance. It was directly linked to the development of a consumer culture, but, even more important, spectatorship gave

access to cultural life in general. Audrey Jaffe's essay on A Christmas Carol shows how social sympathy emerges from the spectator's relationship to spectacle. She argues that Dickens's text is paradigmatic not only for the nineteenth but also for the twentieth century because of the way spectators, cast as the observers of a series of visual representations, gain access not merely to their better selves but also to a set of social relationships and values.

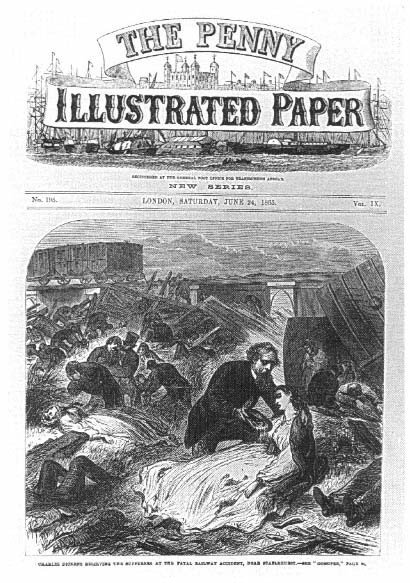

Jaffe's essay, like many essays in this volume, locates in Dickens the paradigmatic writer for her argument. In part the focus on Dickens is an accident of occasion: these essays were originally papers delivered at the 1992 Dickens Conference in Santa Cruz. But Dickens's predominance here has more to justify it than the fact of the conference. In his partnership with illustrators, in his pictorialization of narrative, in his fascination with optical gadgetry, and in his uncanny anticipation of twentieth-century cinema, Dickens, more than any other nineteenth-century writer, provides insight into the multiple aspects of the Victorian visual imagination.

For their assistance at different stages in this project, we are grateful to Linda Hooper, Lark Letchworth, and Heather Julien of the University of California Dickens Project and to Barbara Lee and Betsy Wootten of Kresge College, University of California at Santa Cruz. Special thanks go to Murray Baumgarten and to Paul Alpers for their encouragement and advice.

Were They Having Fun Yet?

Victorian Optical Gadgetry, Modernist Selves

Susan R. Horton

Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.

Walter Benjamin, "Theses on the Philosophy of History"

Solomon Gills repeatedly insists to his nephew Wall'r that he is old-fashioned, that the world has gone past him. But in one way he is one of Dickens's most modern characters. When we first catch sight of him, he has red eyes from looking through the lenses of all those optical gadgets in his shop, eyes "as red as if they had been small suns looking at you through a fog; and a newly-awakened manner, such as he might have acquired by having stared for three or four days successively through every optical instrument in his shop, and suddenly came back to the world again, to find it green."[1]

Those red eyes place him in distinguished company. Three of the most prominent students of vision in the 1830s and early 1840s either went blind or permanently damaged their sight by staring into the sun: David Brewster, inventor of the kaleidoscope and improver of the stereoscope; Joseph Plateau, who studied the persistence of vision; and Gustav Fechner, one of the founders of quantitative psychology. Sol Gills does not go blind. But Dickens, in his portrait of him, produces a verbal version of the piercing confrontation of eye and sun that art historian Jonathan Crary identifies in the late paintings of Turner.[2] Placing the sun in Old Sol's eyes—his name itself a pun—Dickens then turns the reader into a spectator at this transposition.

In the Dickens world this kind of play with visuality is not unusual,[3]

and that is the point. Dickens's narration regularly turns readers into watchers of characters watching one another watching, often watching one another's reflections. On the final page of Bleak House, Esther Summerson's response to her husband's question whether she ever looks in the mirror is "You know I do; you see me do it" (880). The Lammales' marital partnership in Our Mutual Friend is based on an intricate system of scheming and sparring we often watch in the mirror in which they watch each other: "Her eyes . . . caught him smirking in it. She gave the reflected image a look of the deepest disdain, and the image received it in the glass" (260). At young Paul's christening breakfast, Dombey's image is caught in the chimney glass that "reflects Dombey and his portrait at one blow" (52), and readers' first view of Miss Tox's room in that same novel is through the glass over the portrait in her locket, where the "deceased owner of a fishy eye . . . balance[s] the kettle holder on opposite sides of the parlour fireplace" (84). It is not Sydney Carton we see standing before the revolutionary tribunal, but his reflection in a mirror, that "throws the light down upon him. Crowds of the wicked and the wretched had been reflected in it, and had passed from its surface and this earth's together," we are told, and the courtroom itself is represented precisely as if it were one of the dozens of rotundas in operation in mid-century London housing static or moving panoramic or dioramic shows (A Tale of Two Cities, 70–71).

Extended verbal versions of Velázquez's Las Meninas, Dickens's novels are also perspectival reflections on the problematics of empirical vision far more complicated than the woodcuts and engravings meant to illustrate them. This consistent interest in visuality makes a great deal of Victorian prose "modernist" well before the visual arts, and makes "nature, " as the art historian Rosalind Krauss suggests, "the second term of which the first is representation."[4]

Three large questions concern me here: (1) What inspired all this looking at looking? (2) How were Victorians coming to terms with their increasing interest in watching their own watching? (3) What consequences were brought about by the rationales Victorian viewers devised to justify a happy spectatorship and to come to terms with the unreliability of vision?

Walter Benjamin provides my inspiration. Benjamin believed difficult times require major acts of imagination and improvisation, particularly Imaginative acts in which the present moment is projected into the past and the past moment brought forward into the present so as to dissolve the deceptive distance criticism produces between the two. For Benjamin this dissolution is the crucial critical move, since the critical distance

we so carefully cultivate has effectively shut us off from the lessons the past most wants to teach and the present most needs to learn.

A look at scientific experiments carried out in the early nineteenth century is a good place to begin to understand the legacy of Victorian visuality. From 1820 to 1840 huge numbers of experiments were conducted on the physiology of the eye and on the processes of vision; the more that was learned about vision, the more unreliable it seemed to be. Between 1791 and 1798 Goethe wrote frequent letters to Schiller, reporting on the results of his work on the physiology of the eye. Two volumes of these letters were eventually published, entitled The Theory of Colors . They appeared in English translation in the 1830s and would, I surmise, have been brought to the attention of the average English reader through George Henry Lewes's Life and Works of Goethe, which appeared in Britain in 1855. The Theory of Colors proved so popular that it was often reprinted through the century. In it, Goethe insisted over and over that sense impressions depend solely on the sensory nerves excited, not on the external stimuli impinging on them. The Theory of Colors included explicit instructions enabling readers to experience what came to be called the persistence of vision: shift the eye back and forth from a blue circle to a yellow one, and it "sees" a green one that is not there. During the 1830s other experimenters were discovering that the retina could be made to "see" light when sufficient pressure was applied to the eyeball, that the eye would "see" light if exposed to electrical stimulation, and that a blow to the head would make a person "see" light.

These experiments were not centralized in one branch of science, and the resulting findings were frequently published in popular magazines like La Nature, a Victorian version of Popular Science, rather than in specialized journals. Once empirical science had demonstrated how easily the eye could be tricked, an explosion of optical gadgetry and optical toys was inevitable. Optical gadgetry was not invented during the nineteenth century, but until the later eighteenth century the technical means for tricking the eye had been fairly limited. One of the earliest and most popular forms of illusion-generating devices was the phantasmagoria. During medieval times shadows cast on walls with smoke and candlelight had given spectators the frisson of contact with the ghosts and phantoms of the spirit world. During the nineteenth century, these phantasmagorias experienced a resurgence in popularity, and the forms in which they existed grew more numerous. Using one of the increasingly popular magic lanterns, showmen turned a darkened room in which a transparent screen had been dropped between an audience and a lantern filled with one or another form of illuminant into a quite so-

phisticated version of a phantasmagoria. If the slides were of the "dissolving" or "sliding" type, ghosts would appear to open and close their mouths, eyes to shift, skeletons to advance and retreat.[5]

"Apparently one of the ghosts has lost its way, and dropped in to be directed. Look at this phantom!" says the narrator of Our Mutual Friend (148). Phantoms and apparitions materialize and dematerialize regularly throughout A Tale of Two Cities . The Monseigneur's thoughts are described as having been produced out of a process of "vapouring" (226–27), a formulation that would undoubtedly have invoked in Victorian readers the phantasmagoria's smoky gases. Descriptions replicating the phantasmagorical experience enhance Dickens's mysteries:

The fire of the sun is dying. . . . shadow slowly mounts the walls, bringing the Dedlocks down. . . . upon my lady's picture . . . a weird shade falls from some old tree, that turns it pale, and flutters it, and looks as if a great arm held a veil or hood, watching an opportunity to draw it over her. Higher and darker rises shadow on the wall—now a red gloom on the ceiling—now the fire is out. (Bleak House, 564)

Twentieth-century interpretive strategies have turned into complexity—prefigurations of revelations, representations of the Freudian dream space—what for Dickens may have been primarily verbal representations of the phantasmagorical experience. Some of the psychic charge generated by Dickens's novels originates in his maneuvering readers so that they oscillate between recognizing that the ghosts that appear are figments of a character's overwrought imagination and discovering that seeming ghosts or phantoms are simply characters seen imperfectly, from a distance.[6] Part of Victorian readers' pleasure in these novels would have been recognizing in the verbal text their own visual experiences with optical gadgets and toys.

But the responses these evocations of optical gadgetry generated were as complex and various as the gadgets themselves. The kaleidoscope had been invented by Sir David Brewster around 1815, and even this simple toy seems to have produced radically differing reactions. For Baudelaire, and later still for Proust, it suggested wonderful possibilities: "To become a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness [may be] the goal of the lover of universal life," Baudelaire muses. But for Marx and Engels, writing their German Ideology between 1845 and 1847, the kaleidoscope was a fit metaphor for the dangers of faulty perception, "a sham, a trick done with mirrors. Rather than producing anything new, it repeats a single image" and is "entirely reflections of itself."[7]

No short essay can explore all the optical gadgetry nineteenth-

century viewers experienced, let alone analyze the epistemological changes its existence brought about. "People seem to think the camera will do anything," confides one of the street entertainers Henry Mayhew interviews in London Labour and the London Poor . "After their portrait is taken, we ask them if they would like to be mesmerised by the camera, and the charge is only 2d."[8] All they had to do was sit perfectly still and stare into the lens until the mesmerism took effect. After two or three minutes most subjects found that they grew dizzy, their eyes watering, and they gave up. The showman kept the 2d. The scam succeeded in no small part because subjects assumed that their own bodily frailty, not the camera, had let them down. The eyes may fail; the camera never does—a point to which I will return.

L.-J.-M. Daguerre invented the static panorama in the 1820s. The multimedia diorama appeared at the same time. In the first, viewers sat in one spot while pictures rotated around them; in the second, the pictures remained stable while the two concentric rotundas of the amphitheater housing them and the audience were moved easily in a circle "by a boy and a ram engine."[9] In both devices a combination of layered flat planes and movement produced the illusion of three-dimensionality. The zoetrope arrived in the 1830s, and in 1834, the stroboscope, the flicker of light and motion in each prefiguring moving pictures. The iconoscope, a vacuum-tube precursor of the television, appeared about the same time. Unless Victorian photographs lie, by 1850 every well-appointed Victorian parlor had a stereoscope or two, offering viewers an experience of what came to be called the reality effect. By century's end, enterprising manufacturers seem to have decided that three-dimensional nudes were the stereoscope's best subject matter, thus proving the essentially erotic, voyeuristic connection between optical gadgetry and spectatorship that I consider later in this essay and guaranteeing the banishment of the stereoscope from genteel drawing rooms.[10]

Contemporary art historians like Rosalind Krauss and Jonathan Crary argue that all these optical gadgets were more than playthings. They were embedded "in a much larger and denser organization of knowledge and of the observing subject," as Crary suggests.[11] He devotes a significant portion of his Techniques of the Observer to analyzing the epistemological implications of the camera obscura, a darkened box with a small aperture to let in light, which projected images from outside onto one of the inside walls. The image produced was an exact replica (albeit inverted) of what the eye would see if it looked directly at the object being reflected. The camera obscura, then, delineated a position for the observer (inside, enclosed, private, quite literally "in the

dark"), a position Crary argues became "a precondition for knowing the outer world." The dark isolated center where the viewer sat came to constitute the single definable point from which the world could be logically deduced and re-presented.[12]

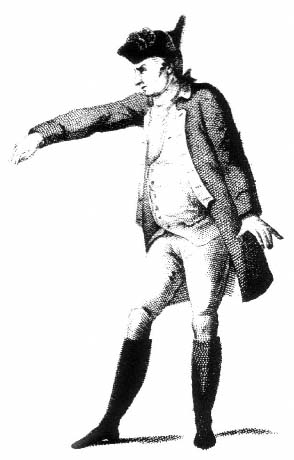

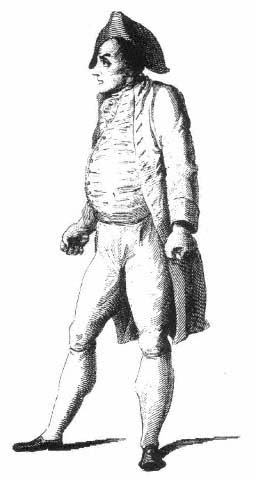

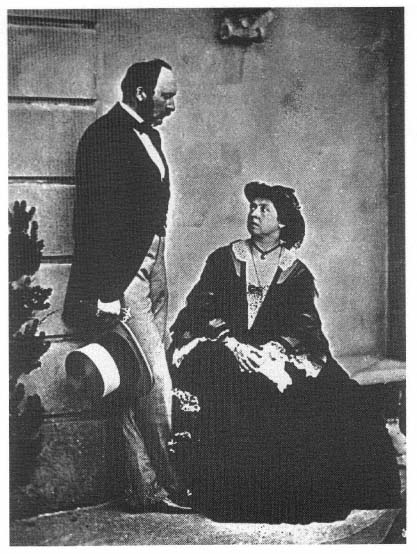

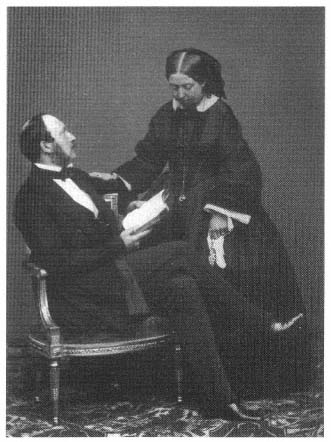

In fact from its earliest appearance the camera obscura had existed in two quite different forms: as a darkened room, in which a spectator sat, and as a handheld version (see Figs. 1, 2). Still, the connections Crary makes between the vantage point the camera obscura requires and nineteenth-century urgings toward "right seeing," and between right seeing and right thinking, are visible everywhere in Victorian prose. "The right thing in the right place is beautiful; the right thing in the right place is Truth," proclaimed the nineteenth-century photographer P. H. Emerson.[13]

Clearly, the twin discoveries that the eye could be tricked and that anything could easily be distorted when presented through different lenses or by positioning the viewer in a different spot can be seen to be the simplest explanation for the urgent advocacy in so much Victorian writing of "right seeing" and "right perspective." These twin discoveries are also the simplest explanation for the frequent warnings against those illusory perspectives that might trick us into wrong thinking. Marx and Engels in The German Ideology:

The social structure and the state are continually evolving out of the life-process of definite individuals . . . not as they may appear in their own or other people's imagination, but as they really are . . . . Men are the producers of their conceptions, ideas, etc.—real, active men. . . . If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-processes as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process. . . . The phantoms formed in the human brain are also, necessarily, sublimates of their material life-process, which is empirically verifiable and bound to material premises [emphasis added].[14]

Writing of events in 1852 in The Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx notes "the Constitution, the National Assembly, the dynastic parties. . . . the thunderfrom the platform, the sheet lightning of the daily press . . . all has vanished like a phantasmagoria before the spell of a man whom his enemies do not make out to be a sorcerer."[15] One of the most popular slipping slides for phantasmagorical spectacles throughout the nineteenth century was of ships foundering in a storm at sea, often accompanied by such "sheet lightning."[16]

Like the phantasmagorical spectacles to which Marx alludes here, experiences with the camera obscura were nothing new. The device had

been described as early as the tenth century by Alhazen (abu-'Ali al-Hasan ibn-al-Haytham).[17] But its popularity surged after 1815, and in whatever form people encountered it, it too changed the way they saw. There was the camera obscura with a handle inside that the spectator could turn, swiveling the mirror attached to it and thereby reflecting images from all quarters outside the box. "You could watch it all," notes Olive Cook, "without yourself being seen, and because the people and objects in the picture are so curiously diminished and so strangely lifted from their actual surroundings into the picture rectangle they take on a significance which they do not have when seen normally by the naked eye."[18] Traveling coaches were built with lenses in the top. With the blinds on the windows completely drawn they became camera obscuras on wheels,[19] allowing the passenger inside to enjoy what must have been a deliciously panoptical spectatorship, something Dickens may well have had in mind early in A Tale of Two Cities as the Monseigneur watches the spectacles of want and hunger outside in splendid detachment as his carriage rolls on to his country estate.

Camera obscuras reflected actual objects back at the observer—though upside down. But the magic lantern substituted a reflected image for a direct one, and wherever one looks in Victorian writings, one sees writers struggling to resist not only the seductive appeal of reflections but also an increasing reliance on reflections for a sense of self identity. One major evidence of Teufelsdröckh's dark night of the soul in Carlyle's Sartor Resartus is his recognition that he has become a kind of reflection junkie: "How . . . could I believe in my strength, when there was as yet no mirror to see it in?"[20] Every child in the playground yelling, "Watch me! Watch me!" to her caregiver is Teufelsdröckh's inheritor. For us moderns, heirs to a century's worth of experiencing the self not just as viewer but as viewed, it seems that increasingly the fully experienced experience must be a mediated one. Late-twentieth-century intellectuals have legitimately made much of the Foucauldian surveillance practiced by the colonizer on the colonized; the gaze of males on females, of dominant on subaltern. But were there space here to bring forward all the instances in Victorian prose in which "private" identity seems to require a public audience for its production—Dombey's, Teufelsdröckh's, Sidney Carton's—another piece of our epistemological inheritance from the nineteenth century would become clear.

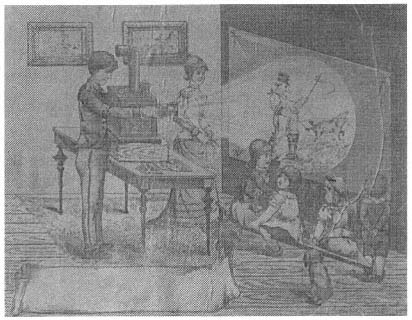

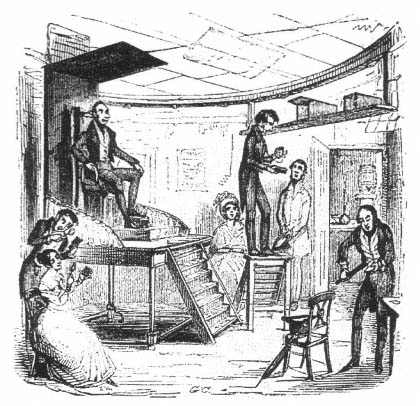

If some of the forms of camera obscuras and magic lanterns Crary discusses did not appear or change during the nineteenth century as dramatically as he suggests, one dramatic change did occur. In earlier centuries phantasmagoria and magic lantern show spectators had

been manipulated from "outside," by a showman. But spectators at nineteenth-century magic lantern shows could see the mechanical device, often being seated on the same side of the screen as the magic lantern, so that part of their enjoyment was the making of the spectacle itself. The Boston Globe wood engraving from circa 1885 (Fig. 3) shows people producing their own magic lantern show, for instance. One contemporary advertisement for a magic lantern designed for home use promised that "Everything necessary is provided and the whole apparatus can be set up without interfering with the furniture or fixtures."[21] In her memoirs Harriet Martineau recollects the magic lantern of her childhood: "I used to see it cleaned by daylight and to handle all its parts, understanding its whole structure; yet such was my terror of the white circle on the wall, and of the moving slides, that to speak the truth, the first apparition always brought on bowel-complaint."[22]

While "handl[ing] all its parts," one could have the extraordinary experience not only of seeing the world through the lenses of optical gadgets and toys but also of being a spectator occupying two places at once: the double experience of having an experience and of watching that experience from the outside, exactly what we moderns parody when we catch ourselves watching ourselves watching, experiencing ourselves experiencing, and ask, "Are we having fun yet?" Rosalind Krauss talks about the "beat" or "throb" of this inside/outside ("I'm in this experience; I'm watching this experience") as it is replicated by the slats of the zoetrope.[23]

Crary suggests that the Victorians were caught between two models of vision: that of the empirical sciences, which were proving the eye of the observer unreliable and subjective, and that of the various romanticisms and early modernisms, which posited the observer as an active, autonomous producer of his or her own visual experience.[24] Predictably, the share of contradictory models created some unease, and the insistence of people like Darwin that one trust the empirical precisely when it was proving itself unreliable led to some interesting interventions. John Ruskin argued against any mediation between the eye and the object it rests upon. But he argued for what he called "the innocence of the eye" even as his writings worked to persuade others to see, not with their own "innocent" eyes at all, but through those wonderfully elaborate rhetorical lenses he was perpetually fashioning for them. Matthew Arnold, by lodging our critical responsibility in our "see[ing] the object as in itself it really is," in his "Function of Criticism at the Present Time"—despite Victorians' increasing uncertainty of the visual as a grounding for truth—can be understood as advocating the Kantian sub-

lime: he insisted, that is, on an essence hidden behind appearances. If appearances lie, if the visual is not to be trusted, one needs a proper guide telling one what one ought to assume is "there" in what is seen. That proper guide of course is reason, and reason requires the surrender of both imagination and empirical vision. This trajectory can be followed unbroken to today's debates over the canon, and the appeal of the argument that one needs to be taught to rely on others to tell one where to look, and what to see, becomes altogether explicable.[25]

But a post-Kantian subjectivity was already around as Arnold was writing. Marx and Engels begin The German Ideology by attacking "Young-Hegelians" like Carlyle (and presumably Arnold) because "the phantoms of their brains have got out of their hands."[26] Marx and Engels do not so much deny the existence of an essence behind appearances, unavailable to empirical vision, as make identifying that "essence" our most urgent work. Personal interpretation of what the eye sees takes precedence over reason because it constitutes our best means to grasp the material conditions of our lives: "The 'essence' of fresh water fish is the river. But it ceases to be its essence when the river is made to serve industry, and dye from tanners flows into it."[27] The specters or phantoms of the phantasmagoria become Marx and Engels's subject as well: "It is self-evident that 'spectres' . . . are merely the idealistic expression of conceptions. . . . The image of very empirical fetters and limitations."[28] That the empirical might actually constitute "fetters" is echoed in The Gründrisse, in which Marx chides Mill for not seeing as clearly as he might precisely because he is looking too close and has "lost his way in eclectic, syncretic compendiums."[29]

Nine years after Arnold published his "Function of Criticism at the Present Time," Pater would insist in his preface to The Renaissance that "the first step towards seeing one's object as it really is, is to know one's own impression as it really is." Later still, Wilde would address this same Kantian struggle in his Dorian Gray . "It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances," Lord Henry notes, adding that "the true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible."[30] Recognizing the violence implicated in all calls to the sublime, he confesses, "I can stand brute force, but brute reason is quite unbearable."[31]

As mid- and late-Victorian prose writers struggled to come to terms with the fallibility of the visual as grounding for the true, the Victorian public were attending optical shows in droves, were regularly inviting street lanternists into their parlors and drawing rooms for party entertainments, or were renting or buying gadgetry of their own. Richard Altick's Shows of London is the best of the many surveys of the public

shows. And nearly any good study of the prehistory of photography and motion pictures considers optical gadgetry for home use. There were biscuit tins with slats in their sides that, when emptied, became a zoetropic wheel. Newspapers frequently contained a pattern readers could cut out, fasten into a circle, and turn into a zoetrope. Milton Bradley was producing zoetropes by 1870 (see Figs. 4, 5).[32]

Those of course were for home use. As for public spectacles, Olive Cook notes that as many theaters housing dioramas or panoramas existed

in London one hundred twenty years ago . . . as there are movie theatres today. In Leicester Square, the Strand, at Regent's Park; on Regent, Oxford, Saint James, and King Streets; at Hyde Park Corner, Waterloo Place, the Haymarket, Piccadilly, Adelaide Street. The Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, and Drury Lane all included dioramas in their repertoire. Play productions included entre-acte showings of such things as the "Moving Diorama of the Polar Expedition" just as newsreels used to be shown, or previews are, at movie theatres today.[33]

There was the Betaniorama, the Cyclorama, the Europerama, the Cosmorama, the Giorama, the Pleorama, the Kalorama, Kineorama, Poecilorama, Neorama, Nausorama, Octorama, Physiorama Typorama, Udorama, and Uranorama. These were popular not just in England. In Le Père Goriot a group of young artists speak a species of dialect Balzac calls rama that soon "infects" everyone around them: "La récente invention du Diorama, qui portait l'illusion de l'optique à un plus haut degré que dans les Panoramas, avait amené dans quelques ateliers de peinture la plaisanterie de parler en rama, espèce de charge qu'un jeune peintre, habitué de la pension Vauquer, y avait inoculée. 'Eh bien! monsieurre Poiret . . . comment va cette petite santérama ?'" Soon, Vautrin notes, "Il fait un fameux froitorama, " to which Bianchon responds, "Pourquoi dites-vous froitorama ? il y a une faute, c'est froidorama ." Their banter is interrupted only by the arrival of a fine "brotherama."[34]

Dickens's novels contain specific references to moving panoramas and dioramas and to peepshows, for instance, the Battle of Waterloo Peep Show in Our Mutual Friend, which could be transformed to show another battle if the showman simply altered the shape of the Duke of Wellington's nose—a bit of information Dickens may have lifted directly from one of the interviews with street performers in Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor : But other references are less obvious. Young David Copperfield leaves the theater at Covent Garden after seeing a production of Julius Caesar, "revolving the glorious vision all the way." Modern readers may assume that "revolving" just describes

his turning an idea around in his head, but Davy immediately confesses, "I was so filled with the play, and with the past—for it was, in a manner, like a shining transparency, through which I saw my earlier life moving along" (286). Olive Cook notes that from 1826 to 1850 "many exquisitely painted transparencies" appeared.[35] Exactly which "shining transparency" Dickens has in mind here is impossible to tell. During his lifetime he would have had access to the "Opening of the Thames Tunnel" peepshow; "The Great Exhibition of 1851" peepshow; "The Coronation of Queen Victoria" peepshow; "The View of London" panorama of 1829, continuously shown until 1875, which simulated the view from the dome of St. Paul's while it was being repaired; the "Ruins in a Fog" topographical diorama in Regent's Park (1827); and the "Mount Etna" panorama in Regent's Park, which continued to be shown until 1885. This last was particularly affecting since it involved not only sophisticated lighting effects but also the simulated effect of spewing lava.[36] Dickens may have been remembering the gigantic transparent pictures by Daguerre first exhibited in the Eidophusikon: magical extravaganzas, combining effects of sound, music, and motion, that were exhibited under changing light in a cylindrical room with a single opening in the wall like a theater proscenium, the room itself slowly turning, moving the spectators from one part of the picture to another, giving the impression the images were animated.

In its earliest years, around 1830, the Eidophusikon had exhibited topographical or architectural scenes ("The Valley of the Sarnen in Canton Unterwalden, Switzerland," or "The Interior of Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral"); somewhat later, battle pieces ("The Fall of Sebastopol," "The Battle of Solferino," and "The Burning of Moscow") became popular; and as late as 1890 scenes such as "The Battle of Waterloo" and full-size panoramas and dioramas commemorating outstanding social or historical events, like the "Crowning of Queen Victoria," showing the queen marching stately up the aisle to her coronation, were still being shown. The popularity of such entertainments ended when the structures housing them disappeared, nearly always and inevitably because the lamp or gas jet illumination needed for the shows sent the buildings up in flames.[37]

So many of these buildings disappeared and so many of these "magic transparencies" disintegrated after 1860 that we can easily overlook how often and how literally Dickens describes the experience of panorama, diorama, and magic lantern show. Insofar as we do, we miss some of his comedy. If most transparencies represented edifying scenes, Davy's seeing his young life as an appropriate subject for one of them accentu-

ates his entirely illusory sense of his own self-importance—as it also suggests his seeing himself as a spectator at his own life, something to which I will return shortly. We might also miss the poignancy of Dickens's description of Mrs. Gradgrind in Hard Times, "look[ing] (as she always did) like an indifferently executed transparency of a small female figure, without enough light behind it" (16), and the especial poignancy of her death, when "the light that had always been feeble and dim behind the weak transparency, went out" (200).

In Our Mutual Friend, as Silas Wegg examines the human and animal miscellany in Mr. Venus's bottle and bone shop, the reader might recognize Dickens's replication of the experience of attending a static panoramic spectacle. Wegg, like the spectator at such a panorama, turns his head around and sees "humans warious. Bones, warious. Skulls, warious. Preserved Indian baby. African ditto . . . Cats. Articulated English baby . . . Glass eyes, warious. Mummied bird. Dried cuticle, warious. Oh dear me! That's the general panoramic view."

As early as the late eighteenth century the enterprising Belgian showman Étienne Gaspard Robertson had mounted his magic lantern on a trolley with rails. By placing it behind a translucent screen, he produced images that could be made larger or smaller and figures that appeared to "come forward" (as the magic lantern was moved forward on its trolley) and "retired" (as it was moved hack). Mayhew's interviews with traveling showmen in London Labour and the London Poor suggest mid-nineteenth-century street showmen took their shows indoors at night and during cold weather, and Dickens's description of Venus and Wegg holding "the candle as all these heterogeneous objects seemed to come forward obediently when they were named, and then retire again" (81–82) turns them into showmen of exactly this type.

But if human beings make culture—all those optical gadgets, the panoramic shows they made possible, and the nineteenth-century novels and essays that allude to them—culture also produces human beings. The optical gadgets Victorians produced made particular beings of them . Like movies in the twentieth century, optical gadgetry in the nineteenth was a commercial activity. No one forced Victorians to pay to experience the magic lantern slides of itinerant street lanternists or to buy magic lanterns; to visit the Rotunda of London to experience static or moving dioramas or panoramas; to hire psychics to frighten them with phantas-magorias projected on their parlor walls; or to buy zoetropes and phenakistoscopes, any more than anyone forces us today to line up for tickets to the latest Terminator . As Christian Metz notes in his Lacanian study The Imaginary Signifier, the optical gadget industry includes not just the

gadgetry itself and those who run or sell it, but also "the mental machinery . . . which spectators 'accustomed to' [it] have internalized historically and which has adapted them to the consumption" of the images produced by it.[38]

Victorians were paying to see the world differently and to experience the joys of spectatorship; and what they were paying for was undoubtedly changing them. They were experiencing, for one thing, as Jonathan Crary suggests, the driving of a wedge between the real and the optical; between seeing and believing . The mystery plots of nineteenth-century detective novels, Wilkie Collins's magnificent Moonstone (1868) and Woman in White (1859–60), for instance, rely on readers' accepting without question the fallibility of empirical vision. In The Moonstone, Rachel Verinder really "sees" Franklin Blake steal the moonstone from her sitting room; Gooseberry really "sees" Mr. Luker pass off the diamond in the bank to a swarthy sailor with a beard. They really do. But seeing produces no necessarily accurate representation of what is afoot in the world. Watching, being watched, comparing what one "thinks" one saw with what actually is, staying alert for disjunctures between the thought and the reality are activities that constitute the woof and warp of Woman in White .

I looked round, and saw an undersised [sic ] man in black on the door-step of a house, which, as well as I could judge, stood next to Mrs. Catherick's place of abode—next to it, on the side nearest to me. The man did not hesitate a moment about the direction he should take. . . . I waited where I was, to ascertain whether his object was to come to close quarters and speak. . . . To my surprise he passed on rapidly, . . . without even looking up in my face as he went by. This was such a complete inversion of the course of proceeding which I had every reason to expect on his part, that my curiosity . . . was aroused, and I determined on my side to keep him cautiously in view, . . . without caring whether he saw me or not, I walked after him. He never looked back.[39]

Despite all this minute attention to the empirical, neither Walter Hartright nor anyone else ever sees what is so obvious about Anne Catherick and Laura Fairlie. Seeing is not necessarily believing; and the optical is not necessarily the real. Similarly, in some of our most interesting contemporary courtroom trials video footage that might seem irrefutable proof of guilt or innocence can be proved to be anything but. Any good defense lawyer, any good prosecuting attorney, knows that a jury can be convinced that what it sees is not what is.

No spectators are entirely comfortable knowing that the eye is fallible—or seeing themselves as spectators. Spectators need what Metz

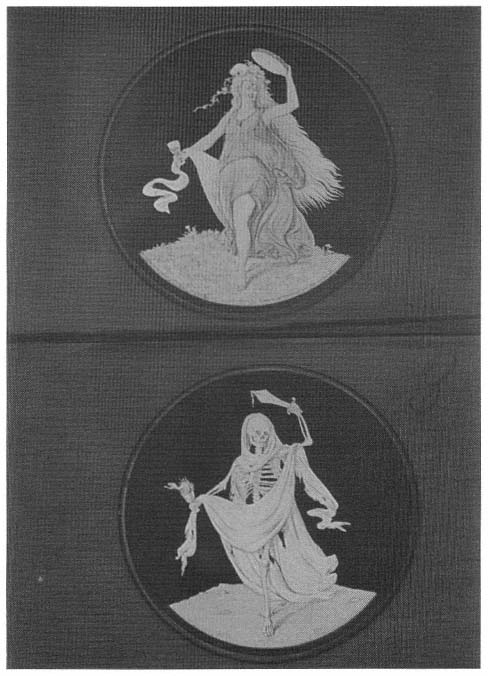

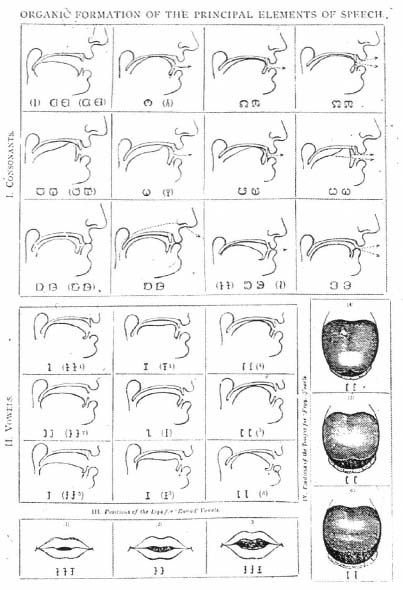

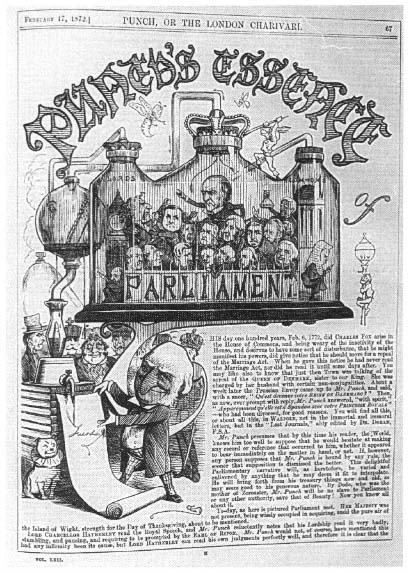

calls a sanctioning construction, something that makes it "all right" to be just a spectator; a genealogy of such constructions can itself be easily constructed. People in the Middle Ages enjoyed their ghosts and specters conjured with mirrors, clouds of vapor, and noises of thunder produced by the rattling of tin—like those produced by wandering trege-tours like those in Chaucer's "Franklin's Tale"—and they too required a sanctioning construction. Medieval spectacles were presided over by priests and magicians. Many of the earliest optical devices were invented by clerics who were also scientists. Athanasius Kircher, who invented the magic lantern around 1640, was a Jesuit priest, and the earliest showmen were often priests or conjurers.[40] They depicted scenes like "the devil rising up to tempt Adam and Eve" or "Noah at the Flood." The spectacles were said to illustrate the work of the Devil, and watching them was supposed to make the viewer fear the Devil's sorcery. Many of the glass transparencies surviving from early-nineteenth-century phantasmagorias and magic lanterns depict biblical scenes or scenes designed to teach a moral lesson: the Prodigal Son, Death seizing a miser, Noah's Ark, and "the Evils of Drink," a dissolving slide showing a beautifully dressed woman being transformed into a horrible skeleton (Fig. 6).[41]

But between 1820 and 1840 less edifying scenes became subjects for popular viewing: a rampaging bull; Napoleon in retreat from Moscow.[42] As the subjects for spectacles changed, the sanctioning construction did as well. Science became the new "god," blessing spectatorship in the Victorian age. Nineteenth-century performances were almost always preceded by a brief lecture by the lanternist or projectionist on the wonders of the technology and science that made the performance possible. The hated "Mr. Barlow" of Dickens's essay of that name from The Uncommercial Traveller is the obsessive teacher, who can ruin even a beautiful night sky because he cannot resist turning it, and everything else, into "a cold shower-bath of explanations and experiments." Mr. Barlow is reported to have "invested largely in the moving panorama trade," and Dickens owns that "on various occasions" he had identified Barlow "in the dark with a long wand in his hand, holding forth in his old way." Barlow's obsession with turning everything into a science lesson is precisely why Dickens professes to "systematically shun pictorial entertainment on rollers" (341). E. P. Thompson's history of the rise of Methodism and other Evangelical religions among the Victorian working class suggests to me that optical spectacles might have become one of the few acceptable forms of entertainment. Even the strictest of Evangelicals allowed for—indeed required—"the earnest pursuit of useful

information."[43] You could watch those magic lantern shows with an easy conscience if what was "really" happening was that you were being educated in and edified by the wonders of modern technology.[44]

A last look at Victorian visuality turns the lens on us. The Victorian woman who "saw" both a dissolving slide of the evils of drink and her own arm holding the magic lantern "showing" the scene could feel both morally edified and detached, "exonerated" for her guilty spectatorship—she might also feel, perhaps, an erotic tingle—while watching the clothes dissolve before her eyes on the victim of drink and the skeleton appear. She also "really " "saw" her own distance from the scene she "saw." Craig Owens suggests that the modern world did not result from the replacement of a medieval world "picture" with a modern world "picture," but was a consequence of "the world bec[oming] a picture at all ."[45] And in The Painting of Modern Life T. J. Clark discusses the nineteenth century's obsession with making both money and the extreme lack of it visible : "The city and social life in general was presented as . . . a separate something made to be looked at—an image, a pantomime, a panorama."[46] Dickens wanted to make poverty, the confusing city, and its masses of homeless wanderers visible to Victorian readers. But his pictures were being read by an audience identifying themselves increasingly—in part because of their experience with optical gadgetry—as spectators, even more comfortably experiencing themselves as simultaneously "inside" and "outside" their own and others' experiences: that is, "inside" and "outside" sympathy. Readers interpolate or read themselves into the signs they are shown, Althusser tells us.[47] But we do like to watch. Whether we are watching starving Somalians on TV or dissolving magic lantern slides illustrating the evils of drink, our spectatorship and voyeurism always have to vie with, and struggle toward, sympathy.

This is not to say we have become indifferent to suffering. But we have had a century's practice inuring ourselves to others' sufferings and a century's worth of sanctioning constructions that make it difficult for us to resist seeing them as spectacle. A year ago my colleague Linda Dittmar brought to campus the Cuban director Sergio Giral's powerful film The Other Francisco . The film begins with a Cuban playwright reading aloud from the script of a play he has written. This play-within-the-film is a highly idealized history of a slave's suicide, a suicide prompted by the slave's despair over the rape of his lover by the plantation owner's son. But this narrative is broken off, and a new voice enters the film. This new voice confronts the viewer with a more accurate representation of the slave's history, This history is far more horrific, punctuated

by horrendous abuse: beatings, torture, the chopping off of various appendages with a cutlass.

It was clear after the showing of this film that all of us spectators had been powerfully affected by the brutality in the film. Our hesitant attempts at discussion after a long and awkward silence were revealing; what they revealed, I believe, was our late twentieth century's sanctioning construction. Some of us began by wondering whether the machete in the film might not be "a phallic symbol."

If the medieval viewer's sanctioning construction, making comfortable spectatorship possible, was the edification and moral instruction provided by the phantasmagorical spectacle of God or the Devil, and a Victorian viewer's was the edification of science and technology, the unwary modern viewer can now be comforted by the late-twentieth-century sanctioning construction: the allegorizing tendency (and all interpretation, as Northrop Frye told us many years ago in his Anatomy of Criticism, is an act of allegory) that enables us as spectators to avoid, as far as possible, both discomfort and guilt: to "see" in the slaveowner's cutlass a phallic symbol and in police beating a black man, a man resisting arrest.

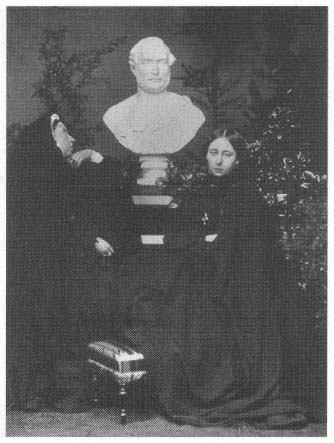

Fig. 1.

Johann Zahn, camera obscura portabilis (reflex box camera obscura),

1685. Courtesy of the Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities

Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Fig. 2.

Sketch of Athanasius Kircher's portable camera obscura from the second

edition of Ars Magna Lucis Umbrae , 1671. Courtesy of the Gernsheim Collection,

Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

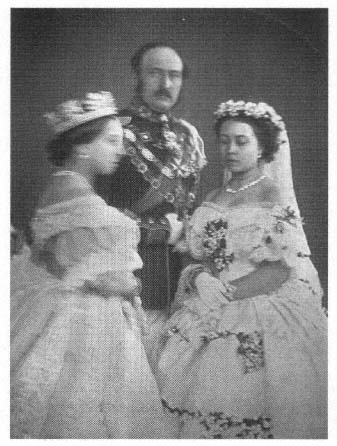

Fig. 3.

Wood engraving of a home magic lantern show, c. 1885. From the

collection of Richard Balzer. Photograph by David M. Seifer.

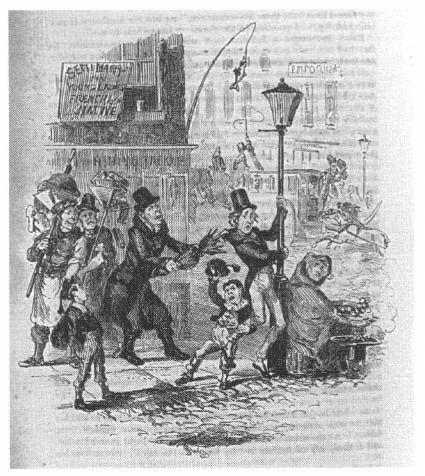

Fig. 4.

Biscuit tin designed to be used as a zoetrope, with slides, England, c. 1920.

From the collection of Richard Balzer. Photograph by David M. Seifer.

Fig. 5.

Cutout zoetrope from the Sunday Supplement to the Boston Herald,

1896. From the collection of Richard Balzer. Photograph by David M. Seifer.

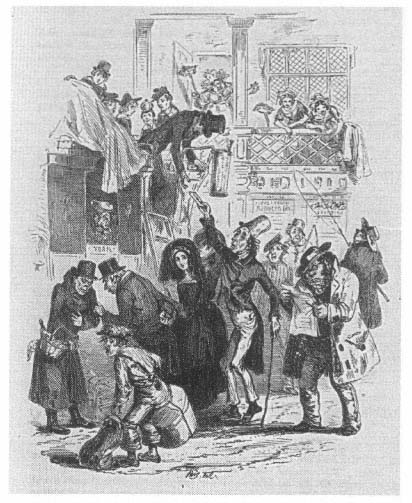

Fig. 6.

"The Evils of Drink," dissolving slides for use in a biunial magic

lantern, c. 1880. From the collection of Richard Balzer. Photograph by David M. Seifer.

Shared Lines

Pen and Pencil as Trace

Gerard Curtis

Tennyson, in a poetic tribute to his friend the writer and artist Edward Lear, writes:

all things fair,

With such a pencil, such a pen,

You shadow forth to distant men,

I read and felt that I was there.[1]

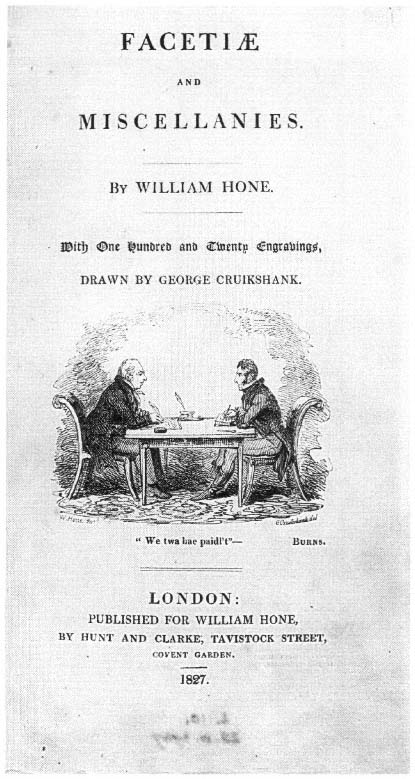

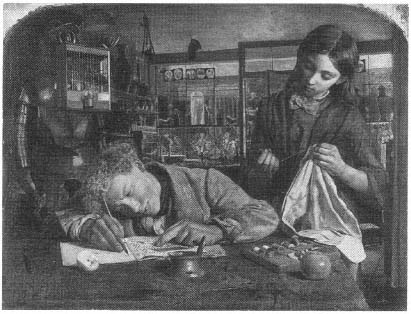

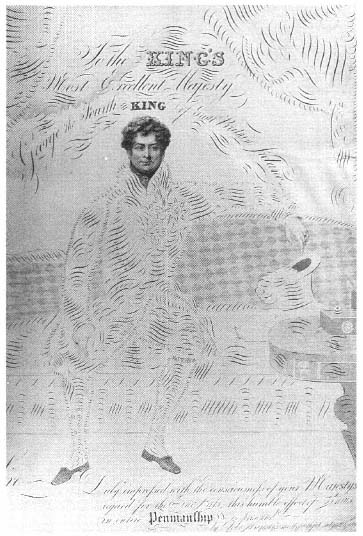

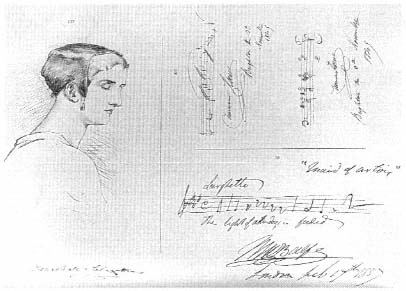

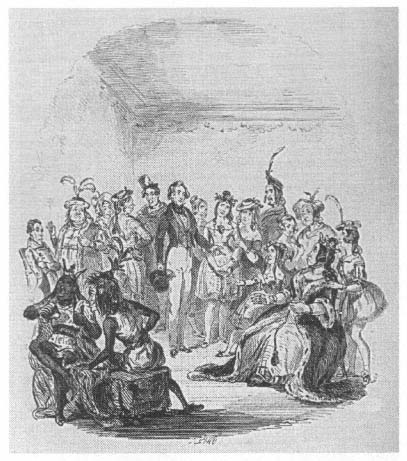

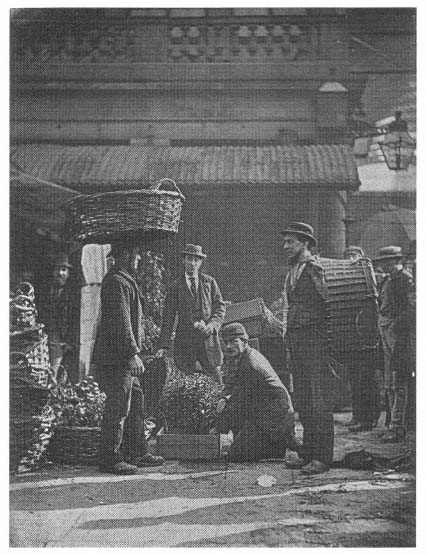

Tennyson's tribute makes an essential association between the pen and the pencil, partners in a single act, and the "trace" they leave, which provides a visible imprint of the author's imagination. George Cruikshank's joint portrait of himself and the reforming pamphleteer William Hone, done in 1827 (Fig. 7), provides another vivid image of this partnership. Hone and Cruikshank are seated at a desk in a position of mutual respect and understanding; both are in the act of scribing with pen and pencil (Cruikshank also has an engraving tool beside him). Writer and artist have equal weight in what are seen as analogous activities.

In today's computer age (with the binary code as its root system) such emphasis on the drawn line seems merely fanciful; in the Victorian period, "the line," whether drawn or written, functions as a trace that constitutes the sign of meaning. This essay will examine how during the nineteenth century the textual, or written, line came to dominate while the drawn line diminished in value. By the end of the century, a number of artists felt that the basis of their partnership with writers had dissolved. They battled to reassert the value of the graphic line, a battle reflected in Cruikshank's polemic attack on William Harrison Ainsworth and Charles Dickens in The Artist and the Author (1871–72), in

which Cruikshank claims he was the originator of Ainsworth's Tower of London and Dickens's Oliver Twist .[2]

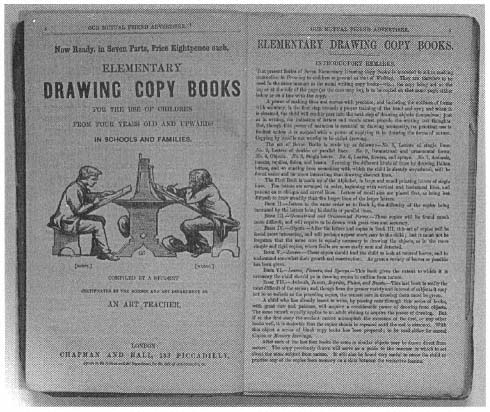

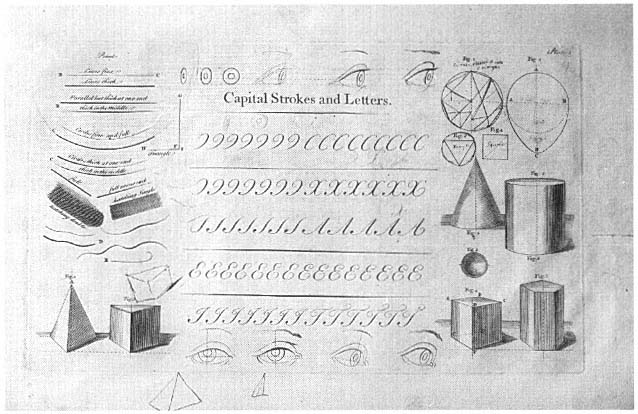

Two advertisements for elementary textbooks in the original Dickens serials demonstrate the stress the Victorian period placed on the foundational aspect of line.[3] In one, Hannah Bolton's First Drawing Book (advertised in Bleak House, no. 9 [November 1852], p. 3.), drawing (or the drawn line) is seen as aiding the schoolmaster in giving "intelligent assistance to the scholar; and while training the band [emphasis added]," it "will instruct the mind." But even more telling is the advertisement for Elementary Drawing Copy Books (Fig. 8) from Our Mutual Friend . By using this copybook series, students could learn drawing and improve their writing at the same time. The book stresses line as the essential link between writing and drawing, words and image. The book starts by instructing students to copy out the alphabet, so that they learn "the different kinds of lines by drawing Italian letters," and ends by having them draw animals and insects. In these now largely forgotten copybook exercises children, under the guidance of the "writing master," learned the structure of the line.

In these copybooks, textual literacy in elementary education gave rise to visual literacy, and vice versa, through a common source in line.[4] Such a linking of text and image was necessary in a period when the records of commerce depended upon the skills of fine penmanship. Advertisements throughout the century helped promote these skills, essential to banking, legal copying, domestic accounts, general accounting, communication, record keeping, and self-advancement. The Domestic CopyBook for Girls taught the proper woman's hand for writing letters, order forms, and housekeeping accounts, while other guides, such as Business Writing and Pitman's Commercial copy Books, taught a masculine hand for commercial work. Gilbert Malcolm Sproat noted in his 1870 text Education of the Rural Poor that the primary skill to be taught in school, above even reading and arithmetic, was writing: "good handwriting is perhaps the most immediately valuable accomplishment for middle-class boys at their start in life."[5] Robert Braithwaite Martineau's painting of 1852, entitled Kit's Writing Lesson (Fig. 9), visually illustrates this point, with Kit (from Dickens's Old Curiosity Shop ) shown laboring over a copybook, doggedly attempting to imitate fine lettering and thus develop that prerequisite to success, an accomplished "hand."[6]

The first volume of The Universal Instructor; or, Self Culture for All (1880–84) carried a series of articles on penmanship, and the proper training of hand and eye in writing. It mentions that a good hand means much, and it teaches decorative penmanship. The third volume contains

a number of articles on drawing. The first of these begins with the essentials of line work, grounded in geometry and the straight line. The articles progress to shading and then to color.[7]The Universal Instructor thus saw both penmanship and drawing as skills necessary for self-education, self-culture.