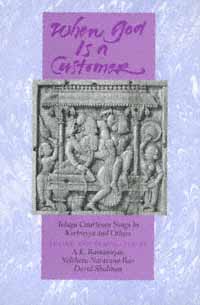

Preferred Citation: Ramanujan, A. K., Velcheru Narayana Rao, and David Shulman When God is a Customer: Telugu Courtesan Songs by Ksetrayya and Others. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1k4003tz/

| When God Is a CustomerTelugu Courtesan Songs by Ksetrayya and OthersEdited and Translated by |

for Wendy Doniger

Preferred Citation: Ramanujan, A. K., Velcheru Narayana Rao, and David Shulman When God is a Customer: Telugu Courtesan Songs by Ksetrayya and Others. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1k4003tz/

for Wendy Doniger

PREFACE

The poems translated here belong to the category of padams —short musical compositions of a light classical nature, intended to be sung and, often, danced. Originally, they belonged to the professional caste of dancers and singers, devadasis or vesyas (and their male counterparts, the nattuvanar musicians), who were associated with both temples and royal courts in late medieval South India. Padams were composed throughout India, early examples in Sanskrit occurring in Jayadeva's famous devotional poem, the Gitagovinda (twelfth century).[1] In South India the genre assumed a standardized form in the second half of the fifteenth century with the Telugu padams composed by the great temple-poet Tallapaka Annamacarya, also known by the popular name Annamayya, at Tirupati.[2] This form includes an opening line called pallavi that functions as a refrain, often in conjunction with the second line, anupallavi . This refrain is repeated after each of the (usually three) caranam verses. Padams have been and are still being composed in the major languages of South India: Telugu, Tamil, and Kannada. However, the padam tradition reached its expressive peak in Telugu, the primary language for South Indian classical music, during the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries in southern Andhra and the Tamil region.[3]

In general, Telugu padams are devotional in character and thus find their place within the wider corpus of South Indian

bhakti poetry. The early examples by Annamayya are wholly located within the context of temple worship and are directed toward the deity Venkatesvara and his consort, Alamelumanga, at the Tirupati shrine. Later poets, such as Ksetrayya, the central figure in this volume, seem to have composed their songs outside the temples, but they nevertheless usually mention the deity as the male protagonist of the poem. Indeed, the god's title—Muvva Gopala for Ksetrayya, Venugopala for his successor Sarangapani—serves as an identifying "signature," a mudra , for each of these poets. The god assumes here the role of a lover, seen, for the most part, through the eyes of one of his courtesans, mistresses, or wives, whose persona the poet adopts. These are, then, devotional works of an erotic cast, composed by male poets using a feminine voice and performed by women. As such, they articulate the relationship between the devotee and his god in terms of an intensely imagined erotic experience, expressed in bold but also delicately nuanced tones. Their devotional character notwithstanding, one can also read them as simple love poems. Indeed, one often feels that, for Ksetrayya at least, the devotional component, with its suggestive ironies, is overshadowed by the emotional and sensual immediacy of the material.

The Three Major Poets of the Padam Tradition

Tallapaka Annamacarya (1424-1503), a Telugu Brahmin, represents to perfection the Telugu temple-poet.[4] Legend, filling out his image, claims he refused to sing before one of the Vijayanagara kings, Saluva Narasimharaya, so exclusively was his devotion focused upon the god. Apparently supported by the temple estab-

lishment at Tirupati, located on the boundary between the Telugu and Tamil regions, Annamayya composed over fourteen thousand padams to the god Venkatesvara. The poems were engraved on copperplates and kept in the temple, where they were rediscovered, hidden in a locked room, in the second decade of this century. Colophons on the copperplates divide Annamayya's poems into two major types—srngarasankirtanalu , those of an erotic nature, and adhyatmasankirtanalu , "metaphysical" poems. Annamayya's sons and grandsons continued to compose devotional works at Tirupati, creating a Tallapaka corpus of truly enormous scope. His grandson Cinatirumalacarya even wrote a sastra -like normative grammar for padam poems, the Sankirtanalaksanamu .

We know next to nothing about the most versatile and central of the Telugu padam poets, Ksetrayya (or Ksetraya). His god is Muvva Gopala, the Cowherd of Muvva (or, alternatively, Gopala of the Jingling Bells), and he mentions a village called Muvvapuri in some of his poems. This has led scholars to locate his birthplace in the village of Muvva or Movva, near Kucipudi (the center of the Kucipudi dance tradition), in Krishna district. There is a temple in this village to Krishna as the cowherd (gopala ). Still, the association of Ksetrayya with Muvva is far from certain, and even if that village was indeed the poet's first home, he is most clearly associated with places far to the south, in Tamil Nadu of the Nayaka period. A famous padam by this poet tells us he sang two thousand padams for King Tirumala Nayaka of Madurai, a thousand for Vijayaraghava, the last Nayaka king of Tanjavur, and fifteen hundred, composed in forty days, before the Padshah of Golconda.[5] This dates him securely to the mid-seventeenth century. Of these thousands of poems, less than four hundred survive. In addition to

Muvva Gopala, the poet sometimes mentions other deities or human patrons (the two categories having merged in Nayaka times).[6] Thus we have poems on the gods Adivaraha, Kañci Varada, Cevvandi Lingadu, Tilla Govindaraja, Kadapa Venkatesa, Hemadrisvami, Yadugiri Celuvarayadu, Vedanarayana, Palagiri Cennudu, Tiruvalluri Viraraghava, Sri Rangesa, Madhurapurisa, Satyapuri Vasudeva, and Sri Nagasaila Mallikarjuna, as well as on the kings Vijayaraghava Nayaka and Tupakula Venkatakrsna. The range of deities is sometimes used to explain this poet's name—Ksetrayya or, in Sanskritized form, Ksetrajna, "one who knows sacred places"—so that he becomes yet another peripatetic bhakti poetsaint, singing his way from temple to temple. But this explanation smacks of popular etymology and certainly distorts the poet's image. Despite the modern stories and improvised legends about him current today in South India, Ksetrayya belongs less to the temple than to the courtesans' quarters of the Nayaka royal towns. We see him as a poet composing for, and with the assumed persona of, the sophisticated and cultured courtesans who performed before gods and kings.[7] This community of highly literate performers, the natural consumers of Ksetrayya's works, provides an entirely different cultural context than Annamayya's temple-setting. Ksetrayya thus gives voice, in rather realistic vignettes taken from the ambience of the South Indian courtesans he knew, to a major shift in the development of the Telugu padam .

If Ksetrayya perhaps marks the padam tradition at its most subtle and refined, Sarangapani, in the early eighteenth century, shows us its further evolution in the direction of a yet more concrete, imaginative, and sometimes coarse eroticism. He is linked with the little kingdom of Karvetinagaram in the Chittoor district of

southern Andhra and with the minor ruler Makaraju Venkata Perumal Raju (d. 1732). Only some two hundred padams by this poet survive in print, nearly all of them addressed to the god Venugopala of Karvetinagaram. A few of the poems attributed to Sarangapani also appear in the Ksetrayya collections, despite the palpable difference in tone between the two poets.

These names by no means exhaust the list of padam composers in Telugu. The Maratha kings of Tanjavur figure as the patron-lovers in a rich literature of padams composed at their court.[8] Similar works were sung in the palaces of zamindars throughout South India right up to modern times. With the abolition of the devadasi tradition by the British, padams , like other genres proper to this community, made their way to the concert stage. They still comprise a major part of the repertoire of classical vocal music and dance, alongside related forms such as the kirttanam (which is never danced).

A Note on the Translation

We have selected the poems that follow largely on the basis of our own tastes, from the large collections of padams by Annamayya, Ksetrayya, and Sarangapani. We have also included a translation of Kandukuri Rudrakavi's Janardanastakamu , a poem dating from the early sixteenth century and linked thematically (but not formally) with the emerging padam tradition. An anonymous padam addressed to Konkanesvara closes the translation. To some extent, we were also guided by a list prepared by T. Visvanathan, of Wesleyan University, of padams current in his own family tradition. Some of the poems included here are among the most popu-

lar in current performances in South India; others were chosen because they seemed to us representative of the poets, or simply because of their lyrical and expressive qualities.

In general, we have adhered closely to the literal force of the Telugu text and to the order of its sentences. At times, though, because of the colloquial and popular character of some of these texts, we have allowed ourselves to paraphrase slightly, using an English idiom or expression. We have also frequently removed, as tedious in translation, the repeated vocatives that dot the verses—as when the courtesan speaks to her friend, who is habitually referred to by conventional epithets such as vanajaksiro , "woman with lotus-eyes," or komaliro , "delicate lady." Telugu is graced with a truly remarkable number of nouns meaning "woman," and these are amply represented in our texts. The heroine is sometimes referred to by stylized titles such as kanakangi , "having a golden body," epithets that could also be interpreted as proper names. For the most part, this wealth of feminine reference, so beautifully evocative in the original, finds only pale and reductive equivalents in the English.

The format we have adopted seeks to mirror the essential features of the original, above all the division into stanzas and the role of the pallavi refrain. While we have always translated both pallavi and anupallavi in full, we have usually chosen only some part of these two lines—sometimes in connection with a later phrase—for our refrains. We hope this will suggest something of the expressive force of the pallavi and, in some cases at least, its syntactic linkage with the stanzas, while eliminating lengthy repetition. The headings provide simple contexts for the poems. We have attempted to avoid heavy annotation in the translations, preferring to let the

poems speak for themselves. Where a note seemed necessary, we have signaled its existence by placing an asterisk in the text. The source for each poem, as well as its opening phrase in Telugu and the raga in which it is sung, appear beneath the translation.

Editions Used as Base Texts

P. T. Jagannatha Ravu, ed., Srngara sankirtanalu (annamacarya viracitamulu ), vol. 18 of Sritallapakavari geyaracanalu . Tirupati: Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam Press, 1964.

Gauripeddi Ramasubbasarma, ed., Srngara sankirtanalu (annamacarya viracitamulu ), vol. 12 of Tallapaka padasahityamu . Tirupati: Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam Press, 1976. (Cited as GR.)

Vissa Apparavu, ed., Ksetrayya padamulu . 2d ed. Rajahmundry: Saraswati Power Press, 1963. (Unless otherwise noted, all the Ksetrayya texts are taken from this edition.)

Mancala Jagannatha Ravu, ed., Ksetrayya padamulu . Hyderabad: Andhra Pradesh Sangita Nataka Akadami, 1978.

Gidugu Venkata Sitapati, ed., Ksetraya padamulu . Madras: Kubera Printers Ltd., 1952. (Cited as GVS.)

Srinivasacakravarti, ed., Ksetrayya padalu . Vijayavada: Jayanti Pablikesansu, 1966.

Veturi Prabhakara Sastri, ed., Catupadyamanimanjari . Hyderabad: Veturi Prabhakara Sastri Memorial Trust, 1988 [1913].

Nedunuri Gangadharam, ed., Sarangapani padamulu . Rajahmundry: Saraswati Power Press, 1963.

INTRODUCTION

On Erotic Devotion

From its formative period in the seventh to ninth centuries onward, South Indian devotional poetry was permeated by erotic themes and images. In the Tamil poems of the Saiva Nayanmar and the Vaisnava Alvars, god appears frequently as a lover, in roles inherited from the more ancient Tamil love poetry of the so-called sangam period (the first centuries A.D. ). Poems of this sort are generally placed, alongside their classical sangam models, in the category of akam , the "inner" poetry of emotion, especially the varied emotions of love in its changing aspects. Such akam poems—addressed ultimately to the god, Siva or Visnu, and contextualized by a devotional framework, usually that of worship in the god's temple—are early South Indian examples of the literary linkage between mystical devotion and erotic discourse so prevalent in the world's major religions.

A historical continuum stretches from these Tamil poets of devotion all the way to Ksetrayya and Sarangapani, a millenium later. The padam poets clearly draw on the vast cultural reserves of Tamil bhakti , in its institutional as well as its affective and personal forms. Their god, like that of the Tamil poet-devotees, is a deity both embodied in temple images and yet finally transcending these icons, and they sing to him with all the emotional and sensual

intensity that so clearly characterizes the inner world of medieval South Indian Hinduism.[1] And yet these Telugu devotees also present us with their own irreducible vision, or series of visions, of the divine, at play with the world, and perhaps the most conspicuous attribute of this refashioned cosmology is its powerful erotic coloring. As we seek to understand the import of the Telugu padams translated here, we need to ask: What is distinctive about the erotic imagination activated in these works? How do they relate to the earlier tradition of South Indian bhakti , with its conventional erotic components? What changes have taken place in the conceptualization of the deity, his human devotee, and the intimate relationship that binds them? Why this hypertrophy of overt eroticism, and what does it mean to love god in this way?

Let us begin with an example from Nammalvar, the central poet among the Tamil worshipers of Visnu, who wrote in the southern Tamil area during the eighth century:

The whole town fast asleep,

the whole world pitch dark,

and the seas utterly still,

when it's one long extended night,

if He who sleeps on the snake,

who once devoured the earth, and kept it in his belly,

will not come to the rescue,

who will save my life? (5.2.1)

Deep ocean, earth and sky

hidden away,

it's one long monstrous night:

if my Kannan too,

dark as the blue lily,

will not come,

now who will save my life,

sinner that I am?

O heart, you too are not on my side. (5.2.2)

O heart, you too are not on my side.

The long night with no end

has lengthened into an eon.

My Lord Rama will not come,

with his protecting bow.

I do not know how it will end—

I with all my potent sins,

born as a woman. (5.2.3)

"Those born as women see much grief,

but I'll not look at it," says the Sun

and he hides himself;

our Dark Lord, with red lips and great eyes,

who once measured this earth,

he too will not come.

Who will quell the unthinkable ills

of my heart? (5.2.4)

This lovesickness stands behind me

and torments my heart.

This con of a night

faces me and buries my sight.

My lord, the wheel forever firm in his hands,

will not come.

So who will save this long life of mine

that finds no end at all? (5.2.6)

The speaker is a young woman, obviously separated from her lover, who is identified as Kannan/Krsna, the Dark God, Rama, and others—that is, the various forms of Visnu as known to the Alvar devotees. The central "fact" stated in each of the verses—which are

taken from a closely knit decade on this theme and in this voice—is that the god-lover refuses to come. The woman is alone at night, in an enveloping black, rainy world; everyone else in the village, including her friends and family, has gone to sleep. She, of course, cannot sleep: her heart is tortured by longing, an unfulfilled love that can be redeemed only by the arrival of the recalcitrant lover. She seems quite certain that this will never happen. Her very life is in danger because of this painful inner state, but there is no one to help her. She blames herself, her "sins," her womanhood—and perhaps, by subtle intimation, the god-lover as well, callously sleeping on his serpent-bed (or, in the final verse of the sequence, "engaged in yoga though he seems to sleep").

All in all, it is a picture of plaintive and frustrated desire. It would be all too easy to allegorize the verses, to see here some version of a soul pining for its possessing deity, translated into the language of akam love poetry. Indeed, the medieval Vaisnava commentators go some way in this direction, although their allegoresis is neither as mechanical nor as unimaginative as is sometimes claimed.[2] But scholars such as Friedhelm Hardy and Norman Cutler are surely right to insist on the autonomy of the poetic universe alive in the Alvars' akam poems. To reduce this poetic autonomy to metaphysical allegory is to destroy the poems' integrity, and with it most of their suggestive power.[3] So we are left with the basic lineaments of the love situation, so delicately drawn in by the poet, and above all with its emotional reality, as the bedrock on which the poem rests. Using the language of classical Tamil poetics, which certainly helped to shape the poem, we can label the situation as proper to the mullai landscape of the forests, with its associated state of patient waiting for the absent lover. The god himself,

Mayon, the Dark One (Krsna), is the mullai deity, and the ceaseless rain is another conventional marker of this landscape.[4] As always in Tamil poetry, the external world is continuous with, and expressive of, inner experience. Thus, in verse 10:

Even as I melt continually,

the wide sky melts into a fine mist

this night,

and the world just sleeps through it

saying not a word, not even once,

that the Lord who paced the earth

long ago

will not come.

The heroine is slowly turning to water, "melting," in the language of Tamil devotion, and although there is pain in this state—the pain of unanswered longing—it is also no doubt a stage in the progressive softening (urukutal ) of the self that Tamil bhakti regards as the ultimate process whereby one achieves connection with the object of one's love.

And things are yet more complex. The blackness of night seems to imitate the role of the god; like the latter, the darkness is enveloping, saturating the world. It is also, again like the deity, cruelly indifferent to the heroine's distress—another form of detachment, like the sleep that has overwhelmed the village (and the god). Internal markers of the mullai landscape thus resonate and alternate with one another, reinforcing its emotional essence within the speaker's consciousness. And, again, the basic experience is one of separation (Sanskrit: viraha ), nearly always a constitutive feature of the bhakti relationship between god and human devotee. Other features of this relationship are also evident in the poem. For example, one immediately observes the utter asymmetry

built into the relation: the heroine, who in some sense speaks for the poet, is relatively helpless vis-à-vis her beloved. She can only wait for him and suffer the torment of his absence. He, in contrast, is free to come or not, to show compassion, if he wishes, and save her life—or let her die of love. There is no way for her to reconstitute his presence. The whole universe proclaims to her his remoteness, seemingly both physical and emotional; she is dwarfed by the inherent lack of equality between them. Interestingly, she blames her situation in part on her womanhood. Being a woman puts her precisely in this position of helpless dependence. She is not even in control of her emotional life: she accuses her heart of having turned against her ("you too are not on my side"), as if a part of herself had split away. This sense of a torn and conflicted personality is typical of the Tamil bhakti presentation of self. Overruling passion for the unpredictable and usually distant deity has disrupted the harmony and coherence of the devotee's inner being.

Contrast this picture—blocked desire, unending separation, a world turned dark on many levels, the helplessness of womanhood, a shattered self—with one we find in Ksetrayya:

Woman! He's none other

than Cennudu of Palagiri.

Haven't you heard?

He rules the worlds.

When he wanted you, you took his gold—

but couldn't you tell him your address?

Some lover you are!

He's hooked on you.

And he rules the worlds

I found him wandering the alleyways,

too shy to ask anyone.

I had to bring him home with me.

Would it have been such a crime

if you or your girls

had waited for him by the door?

You really think it's enough

to get the money in your hand?

Can't you tell who's big, who's small?

Who do you think he is?

And he rules the worlds

This handsome Cennudu of Palagiri,

this Muvva Gopala,

has fallen to your lot.

When he said he'd come tomorrow,

couldn't you consent

just a little?

Did you really have to say no?

What can I say about you?

And he rules the worlds

The senior courtesan or madam is chiding her younger colleague. God himself has come as a customer to this young woman, but she has treated him rather haughtily—taking his money but refusing even to give him her address. The madam finds him wandering the narrow streets of the courtesan colony, too embarrassed to ask for directions. Although his real nature and power are clear enough— as the refrain tells us (and the young courtesan), this customer rules the worlds—it is the woman who has the upper hand in this transaction, while the deity behaves as an awkward and essentially help-

less plaything in her control. He wants her, lusts for her, and yet she easily eludes him. Their relationship, such as it is, is transactional and mercenary, and the advantage wholly hers. if Nammalvar showed us an asymmetrical bond between the god and his lover (who speaks for the poet-devotee), here the asymmetry, still very much in evidence, is boldly reversed. Moreover, the emotional tone of the Telugu padam is radically different from that of the Tamil decade. The atmosphere of tormenting separation, viraha , has dissolved, to be replaced by a playful though still far from harmonious tone. God and woman are involved here in a kind of teasing hide-and-seek, with money as part of the stakes, and the woman is an active, independent partner to the game.

It is not always the woman's voice we hear in Ksetrayya; on rare occasions, the male deity-lover is the speaker. But the image of the woman—the human partner to the transaction—is on the whole quite consistent. Usually, though again not always, she is a courtesan, practiced in the arts of love, which she freely describes in graphic, if formulaic, terms. She tends to be worldly, educated, articulate, perhaps a little given to sarcasm. In most padams she has something to complain about, usually her divine lover's new infatuation with some rival woman. So she may be angry at him— although she is also, at times, all too easily appeased, susceptible to his facile oaths of devotion. Indeed, this type of anger—a lover's pique, never entirely or irrevocably serious—is the real equivalent in these poems to the earlier ideology of viraha . The relationship thus retains elements of friction and tension, though they are less intense than in the Tamil bhakti corpus. Loving god, like loving another human being, is never a simple matter. One might even argue that the god's persistent betrayals, his constant affairs with

other women, are felt to be an integral and necessary part of the love bond (just as quarrels are seen as adding spice and verve to love in both Sanskrit erotic poetry and classical Tamil poems). Indeed, these tiffs and sulkings, so perfectly conventionalized, come close to defining the padam genre from the point of view of its contents, which sometimes function in a seemingly incongruous context. Thus, in a dance-drama composed during the rule of Vijayaraghava Nayaka at Tanjavur and describing his marriage to a courtesan, the bride sings a padam immediately after the wedding ceremony, in which she naturally complains that her husband is (already?) betraying her: "You are telling lies. Why are you trying to hide the red marks she left on your lips?"[5]

We should also note that, despite the angry recriminations, the quarrels, and even the heroine's occasional resolve never to see her capricious lover again, many of the padams end in an intimation of sexual union and orgasm. A cycle is completed: initial love, sexually realized, leads to the lover's loss of interest or temporary disappearance and to his affairs with other women. But none of this prevents him from returning to make love to the speaker, however disenchanted she may be, as Ksetrayya tells us:

I can see all the signs

of what you've been doing

till midnight,

you playboy.

Still you come rushing

through the streets,

sly as a thief,

to untie my blouse.

In general, physical union represents a potential resolution of the tensions expressed in many of the poems. In this respect, too, the padam contrasts strongly with the Tamil bhakti models.

It should now be clear why the courtesan appears as the major figure in this poetry of love. As an expressive vehicle for the manifold relations between devotee and deity, the courtesan offers rich possibilities. She is bold, unattached, free from the constraints of home and family. In some sense, she represents the possibility of choice and spontaneous affection, in opposition to the largely predetermined, and rather calculated, marital tie. She can also manipulate her customers to no small extent, as the devotee wishes and believes he can manipulate his god. But above all, the courtesan signals a particular kind of knowledge, one that achieved preeminence in the late medieval cultural order in South India. Bodily experience becomes a crucial mode of knowing, especially in this devotional context: the courtesan experiences her divine client by taking him physically into her body. Even Annamayya, who is primarily concerned not with courtesans but with a still idealized series of (nonmercenary) love situations, shows us this fascination with bodily knowledge of the god:

Don't you know my house,

garland in the palace of the Love God,

where flowers cast their fragrance everywhere?

Don't you know the house

hidden by tamarind trees,

in that narrow space marked by the two golden hills?

That's where you lose your senses,

where the Love God hunts without fear.

The woman's "house of love" (madanagrha ) is the true point of connection between her and the deity-lover. This notion, which is basic to the entire padam tradition, takes us considerably beyond the sensual and emotional openness of earlier South Indian bhakti . The Tamil devotee worships his deity in a sensually accessible form and through the active exploration of his emotions; he sees, hears, tastes, smells, and, perhaps above all, touches the god. But for the Telugu padam poets, the relation has become fully eroticized, in a manner quite devoid of any facile dualistic division between body and metaphysical or psychological substratum. Put starkly, for these devotees love of god is not like a sexual experience—as if eros were but a metaphor for devotion (as so many modern South Indian apologists for Ksetrayya insist). Rather, it is erotic in its own right, and in as comprehensive and consuming a form as one encounters in any human love.

Still, this conceptualization of the relationship does have a literary history, and here we can speak of a series of transformations that take us from sangam poetry through the Alvars and Nayanmar to the padam poets. As already stated, the ancient tradition of Tamil love poetry, with its rich body of conventions, its dramatis personae, and its set themes, was absorbed into the literature of Tamil bhakti . In effect, bhakti comes to "frame" poems composed after the prototypes of akam love poems. The verses from Nammalvar cited above, in which the lovesick heroine laments the absence of her lover who is the god, are good examples of this process:

If my Kannan too,

dark as the blue lily,

will not come,

now who will save my life,

sinner that I am?

What might look like a simple love poem has become something else—a lyric of devotion, which uses the signs and language of akam poetics but which subordinates this usage to its new aim by internal reference to the divine object of worship, replete with mythic and iconic identifying traits.[6] By the time we reach the Telugu padams , the process has been taken a step further. The "reframed," bhakti -oriented love lyric has now acquired yet another frame, which reeroticizes the poem, turning it into a courtesan's love song that is, nonetheless, still impregnated with devotional elements, by virtue of the prehistory of the genre. This development, however, takes somewhat different forms with each of the major padam poets and thus needs to be examined more closely, in context, according to the sequence in which it evolved. Indeed, if we focus more on context than content, our perspective on these poems changes significantly. Although all of them, even those seemingly closest to out-and-out love poems, retain a metaphysical aspect, the exigencies and implications of their social and cultural milieux now come to the fore. In what follows, we briefly trace the evolution of the padam in context from Annamayya to Ksetrayya.

On Contexts

Tallapaka Annamayya composed a song a day for his deity, Lord Venkatesvara of the temple on Tirupati Hill, where the Tamil and Telugu lands meet. According to Annamayya's hagiographer—his own grandson, Tiruvengalanatha—Annamayya's son Peda Tiru-

malayya had these songs inscribed on copperplates together with his own compositions. Considering the total number of songs—Tiruvengalanatha speaks of some thirty-two thousand[7] —-this was a very expensive enterprise indeed, which reflects the status of the poet's family as servants of this most wealthy of the South Indian temple gods. The copperplates were housed in a separate treasure room within the Venkatesvara temple at Tirupati; inscriptions suggest that the treasure room was itself an object of worship. Annamayya's songs were probably sung by courtesans who led the processions and danced before the deity in the temple.

The copperplates divide Annamayya's songs into two categories: the metaphysical and the erotic. It is conceivable that Annamayya's career had two corresponding phases, but it is more likely that this classification resulted from a later act of ordering the corpus. In any case, the two categories are reminiscent of Nammalvar's poems. Indeed, Annamayya is believed to have been born under the same astrological star as Nammalvar and is sometimes regarded as a reincarnation of the Tamil poet. Our first concern, then, is with the manner in which Annamayya uses the language and imagery of eroticism to express his type of devotion.

The courtly tradition in both Sanskrit and Telugu subsumed sexual themes under the category of srngararasa , the aesthetic experience of desire. Many long erotic poems were composed on mythological subjects, with gods as the protagonists, as well as on more secular themes, with human beings as the heroes. Still, it was considered unsuitable to depict the lovemaking of a god and a goddess, even for devotional purposes; such depictions were thought to block the highest aesthetic experience. (Hence the controversy in Sanskrit aesthetic texts over whether bhakti is an aesthetic experi-

ence, a rasa , or not.) Some even insist that such descriptions constitute a blemish because the god and the goddess are father and mother of the universe; explicit reference to their lovemaking is thus offensive.

But for Annamayya no such barriers exist. He describes how Padmavati Lord Venkatesvara's consort, sleeps after making love to her husband:

Mother, who speaks so sweetly,

has gone to sleep:

she has made love to her husband

with all her feminine skills

and is now sleeping

long into the day,

her hair scattered on her face.[8]

Annamayya has songs describing the lovemaking of the goddess, Alamelumanga/Padmavati, in all conceivable roles and situations. Nor is Annamayya content with love between god and his consort. He goes on to describe the lovemaking of other women with Venkatesvara, these women representing every erotic type described in the manuals of love (kamasastra ).

For Annamayya, love/devotion is an exploration of the ideal experience of the divine. Most often, he assumes the persona of the woman who is in love with the god—either the consort herself or another woman. Unlike later padam writers, Annamayya does not describe a courtesan/customer relationship between the devotee and the god. No money changes hands, and the woman does not manipulate the customer to get the best deal. In Annamayya it is always an ideal love relationship, which ultimately achieves harmony. God here is always male, and he is usually in control. He

has the upper hand, even when he adopts a subservient posture to please his woman. The woman might complain, get angry, and fight with him, but in the end they make love and the god wins.

When we come to Ksetrayya, however, the situation is transformed. For one thing, Ksetrayya composed during the period of Vijayaraghava Nayaka (1633-1673), the Telugu king who ruled Tanjavur and the Kaveri delta. This period witnessed a significant shift, leading to the identification of the king with the deity.[9] Earlier, the god was treated as a king; now the king has become god. For the bhakti poets of Andhra, however, especially of Annamayya's period, the king was only too human, at most sharing an aspect of divinity, in the strict Brahminical dharmasastra tradition. These poets did not recognize him as their true sovereign since for them the real king was the god in the temple. But during the Nayaka period in South India (roughly the mid-sixteenth to mid-eighteenth centuries), the distinction between the king in his palace and the god in the temple blurs and even disappears. Ksetrayya could thus address his songs to the king and at the same time invoke the god.

Furthermore, this was also the time when cash began to play a more powerful role in interpersonal transactions. A new elite was emerging, one composed not of landed peasants, as in Vijayanagara times, but of soldier-traders, who cut across traditional social boundaries. These people combined two qualities usually considered incompatible in the Brahminical worldview—martial valor and concern for profit, the quality of a ksatriya (warrior) and the quality of a vaisya (trader). Earlier, when god was king or when the king shared only an aspect of the divine, kingship was ascriptive. To be recognized as a king, one had either to be born in a particular

caste as a legitimate heir or to fabricate some such pedigree. Now, in the more fluid social universe of Nayaka times, ascriptive qualities like birth became less important than acquired qualities like wealth. If a king is god, and if anyone who has money is a king, anyone who has money is also god. For Ksetrayya, therefore, who sings of kings as gods, the shift to customer as god was not far-fetched. Courtesans, who earlier were associated with temples, were now linked to kings—any "king," that is, who had money. The devotional mode, however, did not change. The new god, who was not much more than a wealthy customer, was addressed as Muvva Gopala, as Krsna is known in the local temple.

The shift did not happen overnight. Even in Ksetrayya we still encounter songs in which the divine aspects are more dominant than those of the human customer. But there are songs unmistakably addressed to the latter. Although the devotional meanings still linger, one sometimes suspects that they are simply part of the idiom, often not much more than a habit. The direction is clear and pronounced when we reach Sarangapani, where money is almost the only thing of value. Here any customer is the god, known as Venugopala (again after the local name of Krsna).

We have a slightly earlier precedent for this shift in Rudrakavi's Janardanastakamu , a composition of eight stanzas that are also sung, though not to elaborate music like the padams (nor are they danced to). The theme of this sixteenth-century poem is familiar: the poet assumes the persona of a woman who is in love with the god Janardana (Krsna); she complains that her divine lover is seeing another woman. These songs are very much like Annamayya's, except for one major difference. Here the woman threatens the god, although in the end she is still taken by her cunning lover.

Rudrakavi anticipates Ksetrayya's attitudes; he represents a transition.

Annamayya's songs (and probably also Rudrakavi's) were sung in the temple. There is, however, no evidence that Ksetrayya's songs were sung in temple rituals. Ksetrayya's songs survived among courtesans and in the repertoire of the male Brahmin dancers of the Kucipudi tradition who played female roles. That Ksetrayya traveled to many places to visit courts and temples is clear from the many specific vocatives in his songs (including one even to the Muslim Padshah of Golconda). As we have already mentioned, temples and palaces were associated with courtesan colonies, and it is quite likely that Ksetrayya was composing songs for these courtesans to sing—to a deity, king, or customer, the three categories having been, in any case, conflated into one.

We should also note that in these songs the courtesan and the god-customer acquire individual identities. Telugu scholarly tradition later attempted to reduce them to character types, based on conventional Sanskrit texts on erotics and poetics, but such classifications miss the special quality of Ksetrayya's poems and personae. For instance, women's roles in drama, dance, and poetry were classified into fixed types according to the woman's age, body type, and sexual availability. For example, a heroine is sviya , "one's own wife," anya , "another man's wife," or samanya , "common property," like a courtesan. Depending on her experience, she is mugdha , "an innocent," praudha , "the bold one," or madhya , "the in-between." Heroines are also classified into eight types according to their attitudes toward their lovers. Permutations and combinations of these and other categories yield a staggering number of different types of heroines. An anonymous late-eighteenth-

century Telugu work, the Srnigararasamanjari , attempts to apply such a scheme to Ksetrayya's songs and even expands the classifications further. Ksetrayya's depictions are, however, much too individuated to fit any such prefabricated typology.

The attempt to justify these songs by invoking academic (sastric ) categories is a characteristic response to perceived needs. First, there was a wish to make Ksetrayya's work acceptable to scholars—to legitimize his status as a poet in a way that would allow his courtesan songs to be read as poems of srngararasa , the refined "taste" or "essence" of sexual love, thus giving them a place with the works of the great poets of Sanskrit and courtly Telugu. Second, there was a concomitant desire to dilute the realistic sexuality of the courtesans and to read into these texts elevated meanings of spiritual love. These are two sides of a single process, which requires some further explication if we are to understand the evolution of current attitudes toward Ksetrayya and his "biography."

Around the turn of the century, with the advent of Victorian moralistic attitudes in public life, sexuality and eroticism in Hindu culture and literature came to be seen as a problem. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries social reformers in Andhra opposed the institution of courtesans per se. Kandukuri Viresalingam (1848-1919) started the antinautch movement, which advocated that respectable men should not visit courtesans. Until this time it had been considered prestigious for a man from an upper-caste family to maintain a courtesan. Important men in society prided themselves on their association with courtesan dance groups, which were named after them. People in high positions, such as district magistrates and police commissioners, sponsored courtesan singing groups (melams ); anyone who had business with

the officer was expected to attend such performances and give a suitable gift (osagulu ) to the courtesans, a percentage of which went to the sponsoring officer. As can be imagined, this practice led to corruption in high places. The antinautch movement addressed itself to these social ills with puritanical zeal. But the movement had a negative effect on dance and music. The courtesan had traditionally been the center of song and dance in South India. Housewives were normally prohibited from appearing in public, and certainly from singing or dancing before men. By contrast, the courtesan enjoyed a freedom usually reserved for the men; not only did she not suffer from many of the restrictions imposed on women but she was given the same honor shown to poets in a royal court. Names of great courtesans such as Macaladevi are known in literature dating from the Kakatiya period.[10] Some, such as the learned Rangajamma, were prominent poets in the Nayaka courts.

But all this was possible only to a woman born in a courtesan caste. By the nineteenth century women born in other castes, for whom marriage was prescribed, were not free to cultivate any of the skills courtesans practiced. Any effort on the part of the family woman even to try to look beautiful or display womanly skills was severely censured. Thus, looking into a mirror at night or wearing too many flowers on certain occasions would bring down the wrath of the elders and accusations that the woman was behaving no better than a courtesan. No insult could be worse: in family households a courtesan was regarded as the most despicable thing a woman could become. By this time, then, the world of women was clearly divided into two opposed parts, that of the courtesan and that of the family woman, and neither of the two wished to be mistaken for the other. Chastity, modesty, innocence, dependency,

the responsibility to bear male children to continue the line, and the bringing of prosperity to the family by proper ritual behavior— these were the roles and values assigned to the housewife. These very qualities would be considered defects in a courtesan, whose virtues were beauty, boldness in sex and its cultivation, and a talent for dancing and singing in public. A courtesan could be independent, own property, earn and handle her own money; cunning and coquetry were part of her repertoire. She had no responsibility to bear children, but if she did have a child, a female was preferred to a male. Indeed, a male child in a courtesan's household was both a practical problem and an embarrassment.

Given that these two worlds were so clearly divided, a movement to abolish all courtesans endangered a valuable part of the culture—all that related to song and dance. Granted, in the twentieth century attempts were made to interest young women from respectable families in dance and music so that they could perform in public. Prestigious institutions like Kalakshetra in Madras presented the courtesan dances in a cleaned-up form, renamed the genre Bharata Natyam, and provided it with an antiquity and respectability aimed at making it acceptable to educated, upper-middle-class family women. Still, it was not easy to get these women to sing Ksetrayya's songs, with all their uninhibited eroticism. Doubts and hesitations persisted. Thus, E. Krishna Iyer writes in his English introduction to G. V. Sitapati's 1952 edition of Ksetrayya's padams : "Is it proper or safe to encourage present day family girls to go in for Ksetraya padas and are they likely to handle them with understanding of their true devotional spirit? At any rate can a pada like 'Oka Sarike ' ["if you are so tired after making love just once"] be ever touched by our girls?"[11] Apologetics mix with a

palpable fear of the explicit eroticism of these poems, Krishna Iyer arguing that the people of Ksetrayya's time had a strength of mind we no longer possess.

The trend was now to reinterpret sexual references and representations in Hindu religious texts, ritual, art, and literature by assigning exalted spiritual meanings to them. Even so, many valuable religious and literary texts were proscribed as obscene, while others were published with dots replacing objectionable verses, sometimes spanning whole pages.[12] In an effort to protect traditional texts from disappearing altogether, certain scholars and patrons of art produced limited unexpurgated editions exclusively for scholarly distribution. For works like Ksetrayya's there was yet no reliable printed edition; the songs were preserved in palm-leaf or paper manuscripts. Scholars like Vissa Apparavu and patrons like the Maharaja of Pithapuram (who had long family associations with courtesans) attempted to collect and publish these texts, the Maharaja, for example, sponsoring G.V. Sitapati's volume of Ksetrayya's songs. The effort was laudable and did save the literature from utter extinction. But in order to save the songs the new patrons and scholars "spiritualized" them, arguing that these were by no means erotic courtesan songs. The apparent eroticism was only an allegory for the union of jiva and isvara , the yearning human soul and god.

According to hagiographic legends recorded at this stage, Ksetrayya was above all a devotee. Subbarama Diksitulu, author of the Sangitasampradayapradarsini (1904), tells a story about "Ksetrajna," as he calls him in a conspicuously Sanskritized form. This Ksetrajna, while still a child, was taught a gopalamantra by a great yogi. The boy spent many days uttering the mantra in the

temple, and eventually the god Gopa1a—deity Gopala—deity and patron of the erotic—appeared before him and blessed him. Ksetrajna immediately broke into song. He traveled to the courts of Tanjavur, Madurai, and Golconda, composed songs in praise of the kings there, and was honored in turn by those kings.[13] In another story, reported by the scholar Rallapalli Anantakrsna Sarma, Ksetrayya, a singer and poet who had earned the patronage of kings for his songs about them, returned one day to his native village, Muvva, where he fell in love with a courtesan at the local temple of Muvva Gopala. The courtesan objected that he sang only about kings, never about the god of Muvva, with whom she was in love. So, in order to please her, Ksetrayya sat in meditation for a long time until the god appeared to him and blessed him. From then on, in an ecstasy of divine love, Ksetrayya went from temple to temple, singing to Muvva Gopala. That was why he was called Ksetrayya, one who knows the ksetras or holy places.

Vissa Apparavu reports that a similar story is told by the villagers of Movva, supposedly Ksetrayya's place of birth. According to this story, Ksetrayya's real name was Varadayya. He was an illiterate cowherd who often whiled away his time sitting in the local Gopala temple. Once he fell in love with a shepherdess (or, in another version, a courtesan) who rejected him because he was an unlettered lout. Varadayya then sat, adamant, inside the temple until the god appeared before him and gave him the gift of song and poetry. Varadayya became a devotee of the god, and his love for the woman was transformed into a spiritual quest in which she, too, took part. The two of them are said to have roamed the countryside, singing together.[14]

This type of story is obviously intended to "reframe," and there-

by deeroticize, Ksetrayya's poetry. Modern Telugu films about Ksetrayya have also followed this line. Another, perhaps older, type of legend, however, celebrates Ksetrayya's role as a court poet. Vijayaraghava Nayaka, the king of Tanjavur, is said to have honored Ksetrayya and given him a high position at court. At this, the other poets grew jealous and complained that it was inappropriate for the king, who was a great scholar himself, to elevate Ksetrayya to this level. When Ksetrayya learned of this opposition, he left the last two lines of a song (the padam known as vadaraka po pore ) unfinished, telling the king that he should have it completed by his other poets while Ksetrayya was away for three months on a pilgrimage.[15] The poets struggled for three months but were unable to complete the poem. When Ksetrayya returned, the humiliated poets fell at his feet and begged forgiveness for talking ill of him. Ksetrayya then finished the song. This kind of legend, typically told about court poets such as Kalidasa, tries to assimilate Ksetrayya to the category of court poet, whereas the legends retold by Vissa Apparavu and Rallapalli Anantakrsna Sarma attempt to make him into a temple poet.[16] In both cases, though, we observe a similar drive to obscure or explain away the underlying eroticism of the padam corpus.

On Reading a Padam

Employing but a small number of themes and voices (the courtesan, the god/customer, a senior courtesan who may even be the madam of the house, and sometimes a married woman who has taken a lover), Ksetrayya creates a lively variety of poems with unusual details. In one, a married woman who finds herself pregnant berates

her lover, demanding that he "go find a root or something" to terminate the pregnancy. In another, a senior courtesan, talking to a younger one who is discontented with her lover, says, somewhat testily, "When your Muvva Gopala joins you in bed, if you, my lovely, get ticklish, why complain to me?" We have chosen here only one of the poems for detailed comment—and bear in mind that, in other poems, similar devices may carry very different nuances. Even though these poems belong to the tradition of "light" music (as opposed to the classical tradition, though they do find their way into classical repertoires) and some even sound like American pop songs of the "he-done-me-wrong" variety, every one of the poems in this volume would repay the kind of attention we suggest in what follows, however lighthearted, simple, or even pornographic they may appear at first sight. And indeed they are pornographic in the etymological sense of the term: they are songs for and about courtesans (Greek porne , "prostitute").

Here is poem 175 from the Ksetrayya collection:[17]

A Woman to Her Lover

How soon it's morning already!

There's something new in my heart,

Muvva Gopala.

Have we talked even a little while

to undo the pain of our separation till now?

You call me in your passion, "Woman, come to me,"

and while your mouth is still on mine,

it's morning already !

Caught in the grip of the Love God,

angry with him, we find release drinking

at each other's lips.

You say, "My girl, your body is tender as a leaf,"

and before you can loosen your tight embrace,

it's morning already !

Listening to my moans as you touch certain spots,

the pet parrot mimics me, and O how we laugh in bed!

You say, "Come close, my girl,"

and make love to me like a wild man, Muvva Gopala,

and as I get ready to move on top,

it's morning already. !

As mentioned earlier, every padam begins with an opening stanza, which provides the refrain. This is divided in the original into two parts called pallavi and anupallavi , refrain and subrefrain. The refrain is repeated at the end of each caranam or stanza, as the translation suggests, although we have chosen to abridge the refrain to a phrase.

Characteristic of the refrain is the way it brings closure to each stanza yet returns the listener to the opening lines. The refrain completes the sentence, the syntax of the stanza; it also satisfies the expectation of the listener each time it occurs. Thus, with each succeeding stanza there is a progression and at the end of each a regression, a return that nonetheless gives the repeated phrase a new context, a new meaning. In this poem, the stanzas together also move toward a completion of the sexual act, with the lovers asking for more. When the poem is sung or danced to, the pallavi line is played with, reached differently each time and variously enacted, suggesting different moods in song and different stances and narrative scenes in a dance performance. In this sense, only the

words of the refrain are the same with each repetition: the more it remains the same, the more it changes.

Yet each time the refrain occurs, it laments the lack of completion. "It's morning already! " bemoans the frustration of unsated desire. In the original Telugu, all the verbs of the stanza are non-finite, whereas the verb in the refrain is finite and thus completes the sentence. In terms of meaning, however, the refrain insists on the lack of any satisfying climax and closure. This self-contradictory structure—the form at odds with the meaning—seems to suggest the insatiability of sexual satisfaction. Desire always wants more; the appetite grows on what it feeds on.

This piece—like all Ksetrayya's poems, even the ones that depict lovers' quarrels and infidelities—ends in union: "and [you] make love to me like a wild man, Muvva Gopala." Still, the next line, which begins a new sexual move, ends in dissatisfaction, as the speaker blames that intrusive, ever-recurring morning. These features—the context of dance and song, and the poem's very form, which recapitulates desire from arousal to climax and maybe a return to another beginning—give such songs a light-winged quality of celebration and a very physical playfulness. Likewise, the diction of the padam tends to the colloquial and the familiar. For example, the language of the poems consists mostly of pure Dravidian words, with very few Sanskritized forms, and the poet often uses the intimate vocative ra , which—so a popular oral verse tells us— is appropriate to the speech of young people, to the battlefield, to poetry, and to situations of lovemaking.[18] In general, the sounds reinforce the meanings, often subliminally. For instance, in the second stanza the lines have four second-syllable rhymes: iddara, koddiga , niddara , and muddu . The soft dental double consonants

(-dd -) tend to remind a Telugu speaker of touching, pressing, tightening, embracing, and other such kinesthetic sensations. This particular series also constitutes an internal progression that culminates in muddu , a common word for "tender" or "sweet." The poem is thus building toward this moment of tenderness, before the refrain cuts it off with the dawn. Similarly, the last stanza has second-syllable rhymes on liquids—kalala , ciluka, kaliki, kalasi — which suggest gliding and quick movements. Language-bound as they are, such phonesthemes are impossible to render in another tongue; they are, like so much else in poetry, a translator's despair.

Conclusion

If we compare the padam just analyzed to the Nammalvar poem with which this introduction began, we can sense the distinct evolution of the padam tradition away from its roots in Tamil devotionalism. Here there is no sense that the speaker is in the wrong; she is not waiting eternally for her lover's arrival; there is no landscape of sky and cloud and dark night waiting with her, symbolic of the god's engulfing nature. Nor is the god himself invoked with all his insignia (wheel, mace, lotus feet), nor are we reminded of his many cosmic avatars and acts, against which the speaker's little drama of unrequited love is played out. Viraha , separation—a dominant mood in Nammalvar and other bhakti poets—is here located in the past and thus relegated to the early part of the poem ("Have we talked even a little while to undo the pain of our separation till now?"). If the tradition of love poetry and all its signifiers are enlisted to speak of the human yearning for the divine, here the signifiers of bhakti poetry are only fleetingly alluded to, often by no more than the local name of the god, Muvva Gopala.

To repeat: the original context of the Ksetrayya padams was the courtesan's bedroom, where she entertained a customer identified as a god. No amount of apologetic spiritualizing, no hypertrophied classification in terms of the Sanskrit courtly types, should be allowed to distort the sensibility that gave rise to these poems—even, or especially, if this sensibility has largely died away in contemporary South India. At the same time, we should not make the mistake of underestimating the vitality of the devotional impulse at work in the padams . These are still poems embodying an experience of the divine. The bhakti idiom is never truly lost through the long process of reframing. One indication of its survival is the existence in the padams of strong intertextual resonances, as themes and phrases proper to South Indian devotionalism and familiar from its basic texts are assimilated to the padam's erotic context. Thus Ksetrayya's heroine complains that she has wasted much of her life in ways remote from her real goal, sexual union with her lover:

When will I get married to the famous Mannaru Ranga?

A daughter's life in a lord's family,

I wouldn't wish it on my enemies.

Some days pass as your parents do your thinking for you.

Some days pass brooding and waiting for the moment.

Some days pass pondering caste rules.

Meanwhile the bloom of youth is gone

like the fragrance of a flower, like a trick of fate.

I wouldn't wish it on my enemies

The literature of bhakti is full of such laments. In Tamil we have Cuntaramurttinayanar (9th century), who often reproaches himself in similar terms:

So much time has been lost! . . .

I have wasted so much time being stubborn.

I don't think of you,

don't keep you in my mind.[19]

Or, in a manner verbally very close to Ksetrayya's formula:

Those days that I leave you

are the days consciousness fails,

when life leaves the body

and one is carried away

on a high funeral bier.[20]

The precise formula—"some days (konnallu ) pass"—occurs elsewhere in Telugu, for example in the Venugopalasatakamu , sometimes attributed to Sarangapani (though it was more probably written by a later poet at the Karvetinagaram court, Polipeddi Venkatarayakavi):

Some days passed not knowing the difference

between grief and happiness.

Some days passed in youthful longing for other men's wives,

without knowing it was a sin.

Some days passed begging kings to fill my stomach,

as I suffered in poverty.

Time has passed like this ever since I was born,

swimming in the terrible ocean of life in this world.

O Venugopala, show me compassion in whatever way you

like,

just don't take account of my past.[21]

Echoes such as these help establish the padam's peculiar cultural resonance as a devotional genre building upon, but also transforming, powerful literary precedents.

Let us try to sum up and reformulate the distinctive features of

this form. Like much of the earlier bhakti poetry, the padam generally prefers the female voice. Some padams present us with the persona of a married woman addressing her lover, in a mode of erotic violation. Here, marriage and the husband function as the necessary backdrop to the excitement of real passion, as in many of the poems of Krsna-bhakti from Bengal, although in the padams the woman largely retains the initiative.[22] But, from Ksetrayya on, the female voice is most often that of the courtesan, a symbol of open, intensely sensual, but also mercenary and potentially manipulative sexuality. We thus achieve an image of autonomous, even brazen, womanhood, a far cry from the rather helpless female victim of the absent god in Tamil bhakti . In other respects, too, the differences are impressive. The torments of viraha have given way to less severe tensions relating to the lover's playboy nature, his betrayal of one courtesan with another, his irrepressible mischief and erotic games. Desire is far less likely to be blocked forever, and many of the poems culminate in orgasm, often openly mentioned. This, then, is more a poetry of union than of separation. In contrast to the torn female personality of Tamil bhakti , the courtesan in these poems is remarkably self-possessed. Indeed, the balance of power has dramatically shifted, so that it is the god who frequently loses himself in this woman, while she is capable of toying with her lover, feigning anger, or mercilessly teasing him. She may also, of course, be truly abandoned, left languishing in ways reminiscent of earlier models, but more often she embodies a mode of experiencing the divine that is characterized by emotional freedom, concrete physical satisfaction, and active control. It is the courtesan, after all, who has only to name her price. Undoubtedly the most tren-

chant expression of this perspective is the anonymous padam addressed to Lord Konkanesvara:

I'm not like the others.

You may enter my house,

but only if you have the money.

If you don't have as much as I ask,

a little less would do.

But I'll not accept very little,

Lord Konkanesvara.

To step across the threshold

of my main door,

it'll cost you a hundred in gold.

For two hundred you can see

my bedroom, my bed of silk,

and climb into it.

Only if you have the money

To sit by my side

and to put your hand

boldly inside my sari:

that will cost ten thousand.

And seventy thousand

will get you a touch

of my full round breasts.

Only if you have the money

Three crores to bring

your mouth close to mine,

touch my lips and kiss.

To hug me tight,

to touch my place of love,

and get to total union,

listen well,

you must bathe me

in a shower of gold.

But only if you have the money

What could be clearer than this escalating scale of prices? The god can decide for himself what he wants—or rather, can afford. One is reminded, somewhat ironically, of the list of rituals, each with its set price, performed for pilgrims at South Indian temples. There, however, it is the devotee who pays the fee, while the god, addressed in the act of worship, is the ultimate beneficiary of the gift. An even more powerful inversion—and an indication of just how far the padam tradition has traveled away from earlier bhakti models—is expressed in an image painted by the Virasaiva poet Basavanna (12th century), with reference to rituals of a different sort:

I drink the water we wash your feet with,

I eat the food of worship,

and I say it's yours, everything,

goods, life, honour:

he's really the whore who takes every last bit

of her night's wages,

and will take no words

for payment,

he, my lord of the meeting rivers![23]

THE SONGS

Annamayya

A Woman to Her Lover

Don't you know my house,

garland in the palace of the Love God,

where flowers cast their fragrance everywhere?

Don't you know the house

hidden by tamarind trees,

in that narrow space marked by the two golden hills?

That's where you lose your senses,

where the Love God hunts without fear.

Don't you know my house ?

Don't you know the house,

the Love God's marketplace of passions,

the dusk where the dark clears and yet is not clear?

Don't you know the house

where you live in your own heart?

That's where all affections hold court.

Don't you know my house ?

Don't you know the house

where the garden of daturas make you go mad with love?

You should know: you're the lord of Venkata hill.

Its gates are signed by the Love God,

and you should know that's where

you heap all your wealth.

Don't you know my house ?

Annamayya 262, GR

"maruninagari danda"

raga sri

The Other Woman to Venkatesa

Why blame me that I'm jealous?

When she's with you,

shouldn't I be embarrassed?

When you and she talk in private,

shouldn't I stay outside the gate?

When you signal each other with your hands,

shouldn't I hide and look away?

When she's with you

When you and she look at each other's faces

with me around, shouldn't I hide my face

in my hands?

When you two are covered in a shawl,

isn't it right for me to go play dice?

When she's with you

When your Alamelu* is here in town for you,

what's left for me to do but bow my head

to the two of you?

O Venkatesa, the two of you have ruled me.

Isn't it a pleasure to serve you both?

When she's with you

Annamayya, copperplate 485:448

"enta kuccituralanta"

raga: mukhari

Her Friends Tease the Woman in Love

These marks of black musk

on her lips

red as buds,

what are they

but letters of love

sent by our lady to her lord?

Her eyes the eyes of a cakora bird,

why are they red in the corners?

Think it over, my friends:

what is it but the blood

still staining the long glances

that pierced her beloved

after she drew them from his body

back to her eyes?

What are they but letters of love ?

How is it that this woman's breasts.

show so bright through her sari?

Can't you guess, my friends?

What are they but rays. from the crescents

left by the nails of her lover

pressing her in his passion,

rays now luminous as the moonlight

of a summer night?

What are they but letters of love ?

What are these graces, these pearls

raining down your cheeks?

Can't you imagine, friends?

What could they be but the beads of sweat

left on her lotus-face

by the Lord of the Hills

when he pressed hard,

frantic in love?

What are they but letters of love ?

Annamayya 82, GR

"emoko cigurutadharamuna"

raga: nadanamakriya

A Woman Talking to Herself

Better keep one's distance

than love and part—

especially if one can't manage

seizures of passion.

Make love, get close, ask for more—

but it's hard to separate and burn.

Gaze and open your eyes to desire,

then you can't bear to shut it out.

Better keep one's distance

The first tight embrace is easy,

but later you can never let go.

Begin your love talk—

once hooked, you can never forget.

Better keep one's distance

Twining and joining, you can laugh;

soon you can't hide the love in your heart.

Once the lord of the Lady on the Flower

has made love to you,

you can no longer say

it was this much and that much.

Better keep one's distance

Annamayya, copperplate 484:440

"tagili payuta kante"

raga: ahiri

A Woman to Her Lover

O you lover of whores:

I know your ways,

I can see them all.

Why do you need a mirror to see

the jewel on your wrist?

Some woman has tried to hug you hard

with her hand covered with bracelets.

I can still see the print of their curves

on your shoulder. Why tell me lies?

I know your tricks.

You lover of whores, why do you need a mirror ?

Some woman has comfortably slept

on your chest and the sapphires

of her necklace have left a print

on your skin. Why contest it over and over?

O you love expert, I can't be harsh.

You lover of whores, why do you need a mirror ?

Some woman has made love to you,

Lord of Venkata hill,

plundered your body's perfumes.

Soon after, you come into my arms.

How can I blame you? My weariness is gone.

You lover of whores, why do you need a mirror ?

Annamayya 84, GR

"lanjakadav'auduvura"

raga: ahiri

Rudrakavi

Eight on Janardana of Kandukuru

1 | You've come, haven't you, |

you Janardanaof Kandukuru . | |

2 | Three days ago, |

you Janardanaof Kandukuru . |

3 | You and she, |

you Janardana of Kandukuru . | |

4 | Who was that shy girl |

you Janardana of Kandukuru ? | |

5 | I know all your secrets. |

off my body. | |

you Janardanaof Kandukuru ! | |

6 | You were my constant support, |

Janardana of Kandukuru . | |

7 | All my anger is gone. |

Janardanaof Kandukuru ? |

8 | When you fill my two eyes, |

Janardana of Kandukuru .* |

Ksetrayya

The Madam to a Courtesan

Woman! He's none other

than Cennudu of Palagiri.

Haven't you heard?

He rules the worlds.

When he wanted you, you took his gold—

but couldn't you tell him your address?

Some lover you are!

He's hooked on you.

And he rules the worlds

I found him wandering the alleyways,

too shy to ask anyone.

I had to bring him home with me.

Would it have been such a crime

if you or your girls

had waited for him by the door?

You really think it's enough

to get the money in your hand?

Can't you tell who's big, who's small?

Who do you think he is?

And he rules the worlds

This handsome Cennudu of Palagiri,

this Muvva Gopala,

has falled to your lot.

When he said he'd come tomorrow,

couldn't you consent

just a little?

Did you really have to say no?

What can I say about you?

And he rules the worlds

Ksetrayya 176

"cellabo palagiri cennude vidu komma"

raga: sankarabharanamu

A Woman to Her Lover

"Your body is my body,"

you used to say,

and it has come true,

Muvva Gopala.

Though I was with you

all these days,

I wasn't sure.

Some woman has scratched

nail marks on your chest,

but I'm the one who feels the hurt.

You go sleepless all night,

but it's my eyes

that turn red.

"Your body is my body ," you used to say

Ever since you fell for that woman,

it's my mind

that's in distress.

When I look at those charming love bites

she has left on your lips,

it's my lip that shakes.

"Your body is my body ," you used to say

Maybe you made love

to another woman,

for, O lord who rules me,

my desire is sated.

Forgive me, Gopala,

but when you come back here,

I'm the one who feels small

with shame.

"Your body is my body," you used to say

Ksetrayya, GVS 1:2

"ni menu na men'anucunu"

raga: yadukula kambhoji

A Man Speaks of His Love

What can I do to cool my passion?

Who will bring her,

that gem of a woman,

back to me?

I was able to draw your face,

bright as a lotus,

but could I paint in

its fragrance?

I have drawn your lips,

glowing with desire,

but I couldn't put in

their honey.

Who will bring her ?

I knew how to draw

your lovely eyes,

but not the trembling glance;

painted the soft lines

of the throat

I know so well,

but could not fill it

with birdlike tones.

Who will bring her ?

I even painted

the lovemaking,

bodies coiled

in the Snake Position,

but I couldn't paint you

as you cried, all alive,

"Come, come to me again,

Muvva Gopala!"

Who will bring her ?

Ksetrayya 126

"emi seyudu"

raga: kambhoji

A Courtesan to a Young Customer

You are handsome, aren't you,

Adivaraha,*

and quite skilled at it, too.

Stop these foolish games.

You think there are no other men

in these parts?

Asking for me on credit,

Adivaraha?

I told you even then

I won't stand for your lies.

Handsome, aren't you ?

Prince of playboys you may be,

but is it fair

to ask me to forget the money?

I earned it, after all,

by spending time with you.

Stop this trickery at once.

Put up the gold you owe me

and then you can talk,

Adivaraha.

Handsome, aren't you ?

Young man:

why are you trying to talk big,

as if you were Muvva Gopala?

You can make love like nobody else,

but just don't make promises

you can't keep.

Pay up,

it's wrong to break your word.

Handsome, aren't you ?

Ksetrayya 1

"andagadav'auduvu lera"

raga: sankarabharanamu

A Young Woman to a Friend

Those women, they deceived me.

They told me he was a woman,

and now my heart is troubled

by what he did.

First I thought

she was my aunt and uncle's daughter,

so I bow to her, and she blesses me:

"You'll get married soon,

don't be bashful. I will bring you

the man of your heart."

"Those firm little breasts of yours

will soon

grow round and full," she says.

And she fondles them

and scratches them

with the edge of her nail.

"Come eat with me," she says,

as she holds me close

and feeds me as at a wedding.

Those women, they told me he was a woman !

Then she announces:

"My husband is not in town.

Come home with me."

So I go and sleep in her bed.

After a while she says,

"I'm bored. Let's play

a kissing game, shall we?

Too bad we're both women."

Then, as she sees me falling asleep,

off my guard,

she tries some

strange things on me.

Those women, they told me he was a woman !

She says, "I can't sleep.

Let's do what men do."

Thinking "she" was a woman,

I get on top of him.

Then he doesn't let go:

he holds me so tight

he loses himself in me.

Wicked as ever, he declares:

"I am your Muvva Gopala!"

And he touches me expertly

and makes love to me.

Those women, they told me he was a woman !

Ksetrayya 264

"mosabuccir'amma magavani yadad'anta"

raga: saveri

A Courtesan to Her Lover

Who was that woman sleeping

in the space between you and me?

Muvva Gopala, you sly one:

I heard her bangles jingle.

As I would kiss you now and then,

I took her lips into mine,

the lips of that woman fragrant as camphor.

You must have kissed her long.

But when I tasted them,

they were insipid

as the chewed-out fiber

of sugarcane.

Who was that woman ?

Thinking it was you, I reached out for a hug.

Those big breasts collided with mine.

That seemed a little strange,

but I didn't make a fuss

lest I hurt you, lord,

and I turned aside.

Who was that woman ?

You made love to me first,

and then was it her turn?

Does she come here every day?

Muvva Gopala,

you who fathered the god of desire,

you can't be trusted.

I know your tricks now

and the truth of your heart.

Who was that woman ?

Ksetrayya 61

"iddari sanduna"

raga: kalyani

A Courtesan to Her Friend

It's so late.

He's not coming,

no way.

No use worrying about him.

Just because you've the misfortune

to be my friend,

you needn't wait up till dawn.

You can throw away

the sandal and the musk

and go to sleep.

Who knows where

he is spending the night,

and with what woman?

The whole village is fast asleep.

It's so late

Listen: every bird

has gone home to his mate.

It's rare we get what we desire.

Still, what was my special sin?

It's so late

All excited,

I made the bedroom ready,

waiting for my man.

What's the point now

of these ornaments,

all these flowers?

Who will see this beauty?

He's not to be trusted,

this Muvva Gopala,

who has ruled in my bed.

It's so late

Ksetrayya 37

"inta prodd'aye"

raga: pantuvarali

The Courtesan Speaks to Her Lover

I'm seeing you at last.

It's been four or five months,

Muvva Gopala!

Last night in my dream

you took shape before my eyes.

I got up with a start,

looked for you,

didn't find you.

The top of my sari

was soaked with tears.

I turned to water,

gave in to sorrow.

I asked myself

if you might not

be thinking of me, too.

I'm seeing you at last,

the answer to my prayers

Ever since we parted,

there's been no betel for me,

no food,

no fun,

no sleep.

I'm like a lone woman

in a forest

after sunset,

soaked through by the rain

in the heavy dark,

unable to find a way.

I'm seeing you at last,

the answer to my prayers

My parents blame me,

my girlfriends mock.

This may sound strange,

but I can tell you:

ever since we first made love,

my world

has become you.

I have no mind

other than yours.

I'm seeing you at last,

the answer to my prayers

Ksetrayya 213

"ninnu juda galigene"

raga: punnagavarali

A Courtesan to Her Lover

Why are you so taken? Is she really

more beautiful than all these women?

You can't stop looking at her for a moment.

Why don't you speak your mind?

Does she come to you

flowing with affection

to gather you up in her embrace?

Does she roll you betel leaves,

praise you as the lover

most suited to her love?

Does her passion overwhelm?

I'd love to hear the details

over and over

of what you do

when your minds are one.

Tell me now.