Preferred Citation: McGilligan, Patrick. Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0z09n7m0/

| Backstory 2Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950sEdited and with |

Preferred Citation: McGilligan, Patrick. Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0z09n7m0/

Acknowledgments

This book, a labor of love for all involved, owes its existence to an unusually supportive editor, Ernest Callenbach, and to the writers who did the hard work of some of the interviews: Tina Daniell, Dennis Fischer, Joel Greenberg, Margy Rochlin, Steve Swires, David Thomson.

The scriptwriters themselves were generous with their time and comments, with (in some cases) photographs from their personal stock, and, generally speaking, warm encouragement.

Pat McGilligan compiled all the filmographies, except Walter Reisch's (contributed by Joel Greenberg). The people who conducted (or, in the case of Tom Flinn, "edited") the interviews wrote the respective introductions.

Alison Morley (in Los Angeles) and William B. Winburn (in New York City) volunteered their time and special talents for portrait photography of several of the screenwriters.

The transcriptions were rendered by the reliable Cindy Walker. The copy editor, whose remarks were appreciated and suggestions invariably adopted, was Lieselotte Hofmann.

The Leigh Brackett interview was originally published as "Grab What You Can Get: The Screenwriter as Journeyman Plumber" in the August–September 1976 issue of Films in Review . An edited portion of the Ben Maddow interview originally appeared as "The Invisible Man" in the Summer 1989 issue of Sight and Sound . The Daniel Mainwaring interview was first published as "Screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring Discusses Out of the Past" in the Velvet Light Trap (Fall 1973). The Curt Siodmak interview was originally published, in slightly different form ("An Outspoken Interview with the Sultan of Speculation"), in the December 1988 and March/April 1989 issues of

FILMFAX . An extract of the Philip Yordan interview appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle and in the Los Angeles Times (Sunday Calendar section). Alison Morley's photographs and interview snippets were published as "The Script Men" in the August 1990 issue of American Film . All interviews are reprinted courtesy of the authors and/or the respective publications.

The Walter Reisch interview was originally conducted under the auspices of the Louis B. Mayer Oral History Program of the American Film Institute, and is excerpted here by permission of Mrs. Elizabeth Reisch, Joel Greenberg, and the American Film Institute.

Friends and colleagues who are to be thanked for advice and assistance include Leith Adams, Walter Bernstein, Ned Comstock, Mary Corliss, Andre de Toth, James Greenberg, Penelope Houston, Faith Hubley, Harlan Jacobson, Stuart Kaminsky, Ron Mandlebaum, Ric Menello, Rod Merl, Gerald Peary, John Pym, Leo Rosten, Marian Seldes, Wolf Schneider, Sheila Schwartz, Bertrand Tavernier, Tise Vahimagi, and Martha Wilson.

The still photographs are courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, British Film Institute, Richard Brooks, Collectors Bookstore, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, Davis Freeman, Film Comment, Elizabeth Reisch, Curt Siodmak, Stewart Stern, USC Special Collections, and UCLA Special Collections.

This book is for Joseph McBride—a contributor to the first Backstory —in fond memory of riding along with him to visit the great ones, learning from him, and almost always, having a good time.

Introduction: The Next Wave

The year 1939, generally regarded as the high-tide mark of the Golden Age of Hollywood, is the informal starting date for the chronology of movies and movie-writing careers covered in this book. The film industry was having a heyday. It was a time of B pictures galore (with many a nugget among them) and already highly evolved, quintessentially American genres—the Western, the musical, the gangster film.

An estimated 483 films were produced and released by the studios in that year. But by 1959, that number had plummeted to 187.[*] In twenty years, dramatic events had overtaken the motion picture industry, reshaping the studios, the films, the scripts.

The first thing one notices about the screenwriters and writing credits of the 1940s and 1950s is the significantly fewer number of each, screenwriters and credits, when compared to the generation of motion picture writers who rose to prominence during the early sound era of the late 1920s and early to mid-1930s.

As the deluge of motion pictures dwindled, so of course did the pool of screenwriters. Indeed by 1959, and the dawn of the unruly 1960s, the studio contract writer could be said to be an endangered species.

In his provocative yesteryear chronicle City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s, Otto Friedrich makes it plain that the 1940s were a decade

[*] * Reel Facts: The Movie Book of Records by Cobbett Steinberg (New York: Vintage Books, 1978).

of transition for the motion picture industry, from an era of hope and glory to a period of caution and upheaval.

World War II was a jolt to the system. The recruitment of writers dropped off. The scripts changed to accommodate new social imperatives and genre demands. There were topical themes, extremes of escapist froth, and paranoical film noir .

Several of the writers interviewed here functioned meritoriously behind the scenes on armed forces documentaries during World War II—Richard Brooks, Garson Kanin, Arthur Laurents, Ben Maddow, Daniel Taradash. But, in general, the war put a gap in careers, and after it ended there were some abrupt transitions.

Garson Kanin stopped directing and started writing movies. Poet Ben Maddow found himself in Hollywood, usually writing film scripts instead of verse. Richard Brooks was elevated, thanks to a novel he had written during his tour of military duty, from the B to the A status of Hollywood scriptwriter.

Then came a cycle of misfortune. The year 1946 saw the first regular network television service; the year 1947 brought the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to Hollywood for closed-door hearings; and beginning in the late 1940s, antitrust rulings prescribed the divorcement of the theaters and the end of block-booking.[*]

Massive studio layoffs accompanied the decline in production. There were also deaths of major (and minor) film executives who had figured, for three decades, in the established network of power and relationships. The rules as well as players of the game were in flux.

As early as the mid-1950s, there were no longer armies of writers on each studio payroll competing for A and B credits. Indeed, many of the studios ceased to make B movies altogether. For all intents and purposes, some studios (RKO, for example) ceased to make any movies.

(W. R. Burnett, the novelist and screenwriter of Little Caesar, High Sierra, The Asphalt Jungle, and many other titles, who survived three decades of the system at Warner Brothers, said in Volume 1 of Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood's Golden Age that the handful of scribes remaining on the payroll in Burbank grimly referred to the studio as "Death Valley.")

For some writers, the bête noire of television production offered a kind of haven.[**] No longer succored by the studios, old-time screenwriters, with credits

[*] * The Paramount antitrust ruling came in May 1948. The "consent decree" actions came at intervals thereafter and called for a complete divorcement of the affiliated circuits from production and distribution branches. For further background on the antitrust dissolutionment, see "Part IV: Retrenchment, Reappraisal and Reorganization, 1948—" and "United States versus Hollywood: The Case Study of an Antitrust Suit" by Ernest Borneman in The American Film Industry, ed. Tino Balio (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976).

[**] ** The purists among the screenwriters abstained from television work, their métier being almost exclusively motion pictures. Only the youngest among the screenwriters in this volume, Stewart Stern, has any significant pre-1960 television writing credits.

dating back to the early silents, provided the backbone for certain of the prestigious television series that originated on the West Coast, from "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" to "Bonanza." Of course, they were also busy tossing logs on the more conventional fires of sitcoms and action fillers.

Just as in the early days of sound, frequently the old-timers were assigned to collaborate with the new-timers. The old-timers might ensure the verities of structure and continuity, while the new-timers bolstered the contemporary slant and slang. In this fashion the older generation of writers was passing the torch of "story craft" to younger disciples who would emerge, in the 1960s and 1970s, as the bright lights of a reconstituted Hollywood.

In a way—though this was always a false dichotomy—the existence of television served to point up the more glittering nature of motion pictures. It was more fashionable to believe that, compared to television, motion pictures were the expansive, exploratory, serious medium, just as Broadway, especially for the 1930s generation, had once held the snob edge over Hollywood.

Films (according to this school of thought) could attempt bold social statements or intimate personal ones. Studios could afford the bloated expense of time-span epics, crowd extravaganzas, or special effects. The wide screen was more alluring to the "name" stars and directors. Movies could turn a quicker and bigger profit. The cinema could, and writers always felt this deeply, explore the outer limits of creativity.

Although the antitrust rulings and the inroads of television weakened the motion picture industry, it was the blacklist that especially injured screenwriters. Of the Hollywood Ten who went to jail in 1950 rather than testify before a congressional committee as to their alleged membership in the Communist Party, eight were writers. No one has done a strict accounting as to how many of the other several hundred blacklistees were screenwriters, but the implication in The Hollywood Writers' Wars by Nancy Lynn Schwartz, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930–1960 by Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, and Naming Names by Victor Navasky—among the very best books on the subject—is that writers formed a disproportionate majority of the victims.

There was a ripple effect among those writers who were not blacklisted, especially the liberals who had to fend off suspicions. As a consequence of the climate of fear, much that was progressive, that advanced story material politically or thematically, was submerged or had to battle its way to the surface.

Of course, no one can say what the blacklisted writers might have written. And how one feels about the quality of the movies of the 1950s depends, inevitably, on one's analysis of the cause and effects, the extent, of the blacklist. There is still debate about the cause, and murkiness about the effects, among film historians. Although the blacklist is central to the experience of Hollywood screenwriters who, one way or another, lived through it, inevita-

bly there is disagreement, disparity, contradiction, and paradox in the collective memory—in this book, as in other chronicles that hinge on the blacklist.

Even in the case of the more famous people, the credits for that period are still being sorted out.[*] The "shared" noms de plume are confusing. In this volume Ben Maddow and Philip Yordan, the former operating as the "ghost" of the latter during the 1950s, cannot quite agree on who wrote what. (Between them, they encompass just about any issue one would care to raise about the blacklist.) Film noir exemplar Daniel Mainwaring also permitted his name to be used as a "front" by certain blacklisted writers, yet he always guarded the secrecy of such arrangements.

Naturally, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had trouble keeping the official credits straight during this unfortunate era. Despite the tremendous personal and professional odds against the blacklisted community, and the formal opposition of the industry, there were pseudonymous, blacklist-related Oscar nominees and Oscar winners in the different script categories practically every year of the 1950s.

(Not that, as Arthur Laurents and Philip Yordan relate in their respective interviews, there weren't some dubious credits—and Oscars—before the blacklist as well.)

The career climb for scriptwriters was perilous in the 1950s, and the creative atmosphere in the industry somewhat restrictive. A scriptwriter had to be determined—dead set on that sunshine and swimming pool (the perks were still attractive)—and in love with the idea of writing movies .

That, if anything, was the fundamental difference between the scriptwriters of the earliest sound era and those of the "next wave."

More of the "next wave" scriptwriters had prejudices in favor of, not against, motion pictures. The great film artists, such as D. W. Griffith, Charles Chaplin, and Orson Welles, had conquered the effete critics. Now there were

* The Hollywood Ten themselves were effectively blacklisted by the joint statement of the Hollywood studio bosses at the Waldorf Conference of November 1947. However, the institutionalization of the blacklist is generally dated as beginning around 1950, when the appeals of the Hollywood Ten were denied and they went to prison. The second round of HUAC hearings began in 1951, and with it the dragnet and repression of hundreds of others. Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund's The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930–1960 (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor/Doubleday, 1980) is one of the many sources that date Dalton Trumbo's screen credit for Spartacus, in 1960, as marking the watershed beginning of the end of the blacklist, although for many others, the curtailments effectively lingered on until the mid-1960s.

Just as in this volume there is disparity in accounts, disagreement can be found in the best histories. There are Hollywood people who claim that manifestations of the blacklist were widespread immediately after the HUAC hearings of 1947, and others who say that the practical effects of blacklisting continued, for them, well beyond the mid-1960s. Obviously, the blacklist was not monolithic. Readers are advised to consult and compare these recommended books, among the most comprehensive and reliable ones on the subject: Ceplair and Englund's The Inquisition in Hollywood, Victor Navasky's Naming Names (New York: Viking Press, 1980), and Nancy Lynn Schwartz's The Hollywood Writers' Wars (New York: Knopf, 1982).

museum retrospectives and celebratory books about "the cinema," along with well-documented admiration for the Hollywood-stamped product in such sophisticated foreign capitals as London, Paris, and Rome. Movies had been validated as an art form.

The screenplay itself had acquired grudging respect. As we know from FrameWork, Tom Stempel's valuable history of U.S. screenwriting, there were, early on, plenty of how-to books about motion picture scenarios, as well as, dating from the 1930s, prestigious script collections edited by John Gassner and Dudley Nichols (Oscar winner for the screenplay of The Informer in 1935). These preserved the best "film plays" for study and imitation by fans and practitioners.

The ambivalence towards Hollywood that haunted the group of screenwriters interviewed in Volume 1 of Backstory does not manifest itself, at least to the same marked degree, among the screenwriters of Volume 2.

The "next wave" of screenwriters may have had flourishing sidelines. They may have had independent bodies of work as novelists or playwrights or even, as in the case of Ben Maddow in this volume, as poets. But with notable exceptions, they became the first generation of scriptwriters who put films on the same aesthetic plane as novels and plays.

The impaired state of the film industry in the 1950s did offer some advantages for the younger, more resourceful up-and-comers, who in any case would not have the sentimental perspective of having experienced the good old days of studio writing assignments.

Thanks to the Screen Writers Guild, the scriptwriter was in a better position to protect himself or herself creatively as well as financially. There were benefits and a basic scale owing to the historic guild settlement with the producers in 1941, as well as a formal arbitration process to adjudicate the credits.[*] Although it is impossible to calculate such things, it seems there was much less "forced collaboration" as the 1940s gave way to the 1950s, less rewriting behind the backs of screenwriters. Now, if nothing else, producers had stringent budget incentives to stick to one or two writers.

Broadly speaking, individual writers had more authority and status than in the preceding generation. Writers were compelled less by the machine-belt production that was slowing down or by the need to compile roving "fix-it" credits to justify a studio sinecure. There were still the aggravated relationships between writers and producers (and directors), there were still the familiar shackles of genre axioms. But there were obvious strides in creativity, too.

Perhaps the major changes in post-World War II (and pre-Vietnam War

* See Nancy Schwartz's excellent The Hollywood Writers' Wars for a fully fleshed chronicle of the decade-long struggle to organize the Screen Writers Guild (nowadays known as the Writers Guild of America).

era) film narrative came in areas of content rather than form—sex and politics, Freudian psychologizing, racial problems, and life-style issues (booze, drugs, rock and roll). As the world turned, so did Hollywood.

The scriptwriters of the 1940s and 1950s responded to the changing attitudes and concerns. Featured in this volume are the writers of Intruder in the Dust (1949), The Blackboard Jungle (1952), From Here to Eternity (1952), and Rebel Without a Cause (1955), among other seminal films. Some of these movies may seem tame nowadays, but in their time they were perceived as landmarks in their depiction of inflammatory social issues.

If the best scripts of the "next wave" reflected society more truly, they also seemed to reflect their particular writers more transparently. That was one of the advances over the past. The identity of the writer was manifest in his recurrent concerns and motifs, in a thread of consistent personality throughout a varied career. Writers still could not be autobiographical, strictly speaking, but neither were they constrained to be as impersonal as before. In a word, screenwriters could express themselves more freely.

The Hollywood screenwriters of the 1930s, the "first wave" of sound-era writers, were an extraordinarily versatile group. But their versatility was imposed in part by the studio assignment merry-go-round and in part by the more developmental nature of the task. To some extent, however, the career versatility mitigated against any personal subtext in the writing.

As Stewart Stern remarks in his interview, he always responded better to a script subject that rose "out of the soul." And as Betty Comden and Adolph Green attest, they found themselves echoed, to a surprising degree, in the musical comedies they wrote. What bothered Ben Maddow in the 1950s was the alienation he felt from his true self when he ghosted impersonal scripts for Philip Yordan.

The writers of the 1940s and 1950s were not quite the interchangeable, amorphous creatures that they once appeared to be, at least to many producers of the 1930s. "Send in the boys!" was the old refrain—a couple of writers, the more the merrier. The "next wave" were known to have precise strong suits—distinct literary personalities—outside of which they, and Hollywood, rarely chose to venture.

Writers could also direct. Big revelation!—and yet that's what it was. Before the recognition of the Screen Writers Guild and the flexing of writers' muscles, this dual role was not a given.

Beginning in the early 1940s there was an onrush of top-notch writer-directors like Preston Sturges, Orson Welles, Billy Wilder, and John Huston, not to mention such less impressive examples as Nunnally Johnson, Norman Krasna, and Dudley Nichols. It became practically de rigueur for any important screenwriter to make a stab at directing.

In Volume 1 of Backstory, there were precisely three writers from the

generation of the 1930s who traveled that path. In the present volume, seven writers of the fourteen interviewed also served stints as directors.

Ben Maddow (for independent films and documentaries) and Garson Kanin (whose directing career preceded, and was largely independent of, his scriptwriting career) are each a saga unto themselves. Walter Reisch's directing résumé was, with the exception of one U.S. venture, restricted to Europe. Daniel Taradash tried directing only once. The horror specialist Curt Siodmak tried it several times but never quite enjoyed the authority and obligation as much as did his brother, Robert. These were all intermittent directing careers, whereas the iconoclastic Richard Brooks, of course, was one of the preeminent writer-directors of his generation, able to master both professions.

Directing could be lonely, arduous, stressful. More than one screenwriter in this volume found that it was not the end-all and the be-all. Yet surely the lesson is not lost on the current generation of Hollywood writer-directors that people like Brooks, who armored their integrity by directing their own scripts, have turned out to have the longest, most productive careers.

Many critics consider the 1940s to be an exceptional period of studio movie-making. As books like Nora Sayre's Running Time and Peter Biskind's Seeing Is Believing[*] point up, the 1950s are the more arguable decade. Some seasoned directors hit their stride (Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, George Stevens, Douglas Sirk, Nicholas Ray, and Anthony Mann, to name a few), while others (among them Frank Capra, Charles Chaplin, Fritz Lang, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, Preston Sturges, Lewis Milestone, and William Wellman) stumbled. One's point of view on the decade depends, inevitably, on whether one focuses on the riches, the dregs, or the vast in-between.

Here are reminiscences from fourteen screenwriters responsible for some of the treasure trove, not only from the Truman-Eisenhower era, but from the span of their respective careers, whether they began writing in the 1930s and continue today, into the 1990s, or whether they may have resided, for long stretches of their careers, in Europe or New York City—even Ohio! or Florida! (For as Hollywood quaked, one of the beneficial side effects was that screenwriters could and did scurry to live elsewhere.)

Their backgrounds run the gamut from hardscrabble roots to silver-spoon upbringings, just as their careers include every type of writing challenge, every happenstance, every studio experience. There are undeservedly obscure writers and there are distinguished Oscar winners, unbelievably prolific writers and those who suffered from an occasional "block."

There are updates on the studios and their chieftains of the 1940s and

* Nora Sayre, Running Time: Films of the Cold War (New York: Dial Press, 1982); and Peter Biskind, Seeing Is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties (New York: Pantheon, 1983).

1950s; vignettes of directors (like Cukor) who respected the script and others (like Hawks) who fiddled with it; glimpses and anecdotes of eminent colleagues, including an assortment of tales about Faulkner; insights into the tricks, traps, and technology of films; philosophy about the illusions and realities of the craft.

These Hollywood scribes have differing approaches to scriptwriting. Some (like Richard Brooks and Walter Reisch) believe story and construction to be paramount. Some (theater animals like Garson Kanin and Arthur Laurents) assert that characterization is the cardinal basis. Others (like Leigh Brackett and Dorothy Kingsley) say they were largely content to contribute highlights to other people's screenplays.

There is the usual cheating on the part of the editor to include interviews with people who do not fit tidily into any generational—or genre—concept.

The last gasp of "talkies" screenwriters lured to the film capital with pomp and publicity by the studio talent scouts arrived in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The resourceful Walter Reisch came over by boat in 1937 as a guest of Louis B. Mayer, along with other European refugees escaping Hitler. After winning a national playwriting competition, the intelligent adaptor Daniel Taradash signed with Columbia, the better to escape law practice, in 1938. The mystery man and master of many modes, Philip Yordan, arrived in Hollywood in 1937. Richard Brooks timed his first visit to coincide with the World Series of 1940.

The others are all 1940s arrivals. Stewart Stern, an infantry veteran whose war experience colored his sensitive view of the world, is the only one to affix his name to his first screenplay as late as 1951.

Among the fourteen interviewees are included paragons of most Hollywood genres. Private-eye yarns, neurotic potboilers, and pulp horror seemed to proliferate in the 1940s, and in this book there are one-on-one transcripts with several geniuses of those categories. These writers, with their dark themes, may have been yoked, ineluctably, to the anxiety/fear/suspense of the film noir organism, yet each also manifests unmistakable quirks and signposts.

For example, Daniel Mainwaring's fatalistic scripts are rooted in his own identification with, and suspicion toward, small-town Americana; while Richard Brooks' lone protagonists are, like their creator, self-made men, answerable only to themselves.

Curt Siodmak (from Germany) as well as Walter Reisch (from Austria) had flourishing film careers in Europe for a decade before arriving to cope with Hollywood axioms in the late 1930s. It is interesting that both of them, refugees from Nazism who long, long ago worked together on a science-fiction film classic, F.P.1. antwortet nicht (F.P.1. Does Not Answer, 1932), ultimately trod such divergent ground. Siodmak, a prolific novelist consigned to B studios and producers, became the ultimate shlockmeister of his era, the creator or co-creator of many horror, adventure, and science-fiction film clas-

sics. Reisch, for directors Ernst Lubitsch and George Cukor, for MGM and for Twentieth Century-Fox, refined the elegant Kammerspiel and documentary-style melodrama.

Among the story genres that seemed to dominate the 1950s were the anti-Red parables, the biblical and historical epics, the troubled-teenager pictures, the hard, unsentimental Westerns, the soapy family-dynasty dramas, the "meaningful" science fiction, and the larky musicals. With the exception of the anti-Red offshoot, in this volume we have representative exponents of every territory.

Included are writers of scripts that somehow seem to reflect perfectly that era—time capsules, as it were, of the 1950s—whether it be Richard Brooks' shaping of The Blackboard Jungle, or Comden-Green's ebullient musical Singin' in the Rain (1952), the Philip Yordan psycho-Western Johnny Guitar (1954), or the quintessential James Dean vehicle (co-written by Stewart Stern), Rebel Without a Cause . Typical or topical, these films also reflect something of their writers. That is one of the themes sounded, repeatedly, in this volume.

These writers, presented in alphabetical sequence, brought style and distinction to every project they tackled.

The cult science-fiction and mystery novelist Leigh Brackett began as a "ten-day wonder" at the shoestring studios. Then, on the mistaken assumption she was a hard-boiled male, she was hired by director Howard Hawks to work with William Faulkner on adapting Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep (1946). She worked almost exclusively for Hawks for twenty-some years before being lured away by the fine contemporary directors Robert Altman, for his version of The Long Goodbye (1973), and George Lucas, for the second installment of Star Wars (The Empire Strikes Back, 1980).

In the 1940s and I950s, there was no more gutsy screenwriter than Richard Brooks. He was responsible (often as writer-director) for such diverse material as the novel (The Brick Foxhole ) that was the basis for Crossfire (1947); the Bogart films Key Largo (1948), Deadline U.S.A. (1952), and Battle Circus (1953); and faithful screen adaptations of Joseph Conrad, Dostoevski, Tennessee Williams, Sinclair Lewis, and Truman Capote. Though his career faltered in the 1980s, Brooks's finest films will never go out of fashion.

Arguably the "first couple" of Hollywood musicals (though they aren't married to each other), Betty Comden and Adolph Green co-wrote the scripts for many of our best-loved song-and-dance comedies, including Singin' in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), and It's Always Fair Weather (1955). They stuck to the Arthur Freed unit at MGM and worked primarily with old friends Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly and with director Vincente Minnelli. New Yorkers to the core, Comden and Green left Hollywood with the dissolution of the studio apparatus and returned to stage work, but left an indelible mark as the perfectionists of the modern screen musical.

Garson Kanin 's career was as varied and spectacular, behind the scenes, as the more public one of his wife and frequent collaborator, actress Ruth Gordon. A Broadway and Hollywood wunderkind as an actor and director, he co-directed an Oscar-winning documentary during World War II, then scored his first major success as a playwright-director with the smash Broadway hit Born Yesterday (film version, 1950). He and Gordon provided the witty repartee of sparkling Hepburn-Tracy vehicles and the combustible situations of the early Judy Holliday comedies, all of them directed by their friend George Cukor. After Kanin left movies, he became "the Boswell of Hollywood," a novelist and social historian of Tinseltown's glamorous past.

The fix-it writer Dorothy Kingsley, a former socialite from the Midwest who forged a long comedy career at MGM, graduated through the years from innocuous (and profitable) Esther Williams poolside musicals to splashier (also profitable) tune-filled vehicles with the more imposing names of Frank Sinatra, Cole Porter, and William Shakespeare prominent in the credits.

The novelist, playwright, and stage director Arthur Laurents lived in Los Angeles for all of two years in the late 1940s, but scripted memorably for directors Alfred Hitchcock, Anatole Litvak, Max Ophuls, David Lean, and Otto Preminger. Though blacklisted to some extent, Laurents kept busy in the 1950s and eventually wrote the books for two Broadway perennials, West Side Story and Gypsy . The screen adaptation of his novel The Way We Were (1973) became one of the box-office blockbusters of the early 1970s. Though Laurents is self-deprecating about his film work (and his reasons, as recounted in this interview, are hilariously convincing), he has a reputation as one of the screen's consummate romantics.

Another exceptional, variegated, ultimately checkered career: Once associated with the documentary movement of the 1930s (he co-wrote the seminal Native Land in 1942); Ben Maddow began to write studio features in the late 1940s. His studio assignments (Intruder in the Dust in 1949, The Asphalt Jungle in 1950) were acclaimed, but the flow of work was cut off by the blacklist. Later, after years of "writing underground," Maddow dabbled in directing noteworthy avant-garde features. His Hollywood period was blighted by his role as a House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) cooperative witness, which Maddow speaks about for the first time, and painfully, in this interview.

Walter Reisch had a remarkable life story—spanning involvement with the nascent, post-World War I Austrian film industry; a stint with UFA, producer Erich Pommer, and "talkies" in Berlin; work with Alexander Korda in London; and long contract years with MGM and Twentieth Century-Fox, in Hollywood. An adept originator as well as a director of note in Europe, Reisch became a specialist in "story construction" in the United States, conforming admirably to the disparate studio regimes of Louis B. Mayer and Darryl F. Zanuck.

The younger brother of atmospheric suspense director Robert Siodmak,

Curt Siodmak is the author of many prescient science-fiction and speculative novels, including the well-known Donovan's Brain, which is never out of print and has been filmed three times to date. Though Siodmak likes to say he worked as a screenwriter only for the weekly paycheck, his motion picture contributions—imaginative stories with various dread creatures run amok (to some extent allegorical nightmares of Hitler, who drove him from Europe)—make him one of the leading exponents of the fantastic cinema.

The questing screenwriter Stewart Stern, who has written for Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward and Dennis Hopper, can be said to be a link between the antiheroes of the film generation of the 1940s and those of a more contemporary mold. Unable to cope with the exigencies of Hollywood in the 1970s, Stern left Los Angeles and active screenwriting, retreating to Seattle, where he resides today. As with his screenplays, Stem's emotions are close to the surface, and he speaks movingly of his own limitations, of career disillusionment, of his writer's block.

A somber note is contributed by Daniel Taradash , the Harvard-educated lawyer who became one of Hollywood's most respected literary recyclists, with significant credits ranging from Golden Boy (1939) to Rancho Notorious (1952) to From Here to Eternity (1953) and Picnic (1955). Taradash himself describes the early half of his career, still in the studio heyday, as "triumph," and the latter half, in the hands of independent producers and iffy properties, as "chaos."

As the prototypical "businessman-writer," Philip Yordan deserves, perhaps, a book of his own. A prolific self-promoter with many hard-hitting screenplays to his credit, including Dillinger (1945), House of Strangers (1949), Detective Story (1951), Johnny Guitar (1954), God's Little Acre (1958), and Studs Lonigan (1960), Yordan is controversial for the use of "surrogate writers." He admits to having employed certain blacklisted writers under his aegis in the 1950s. Yordan specialized in crime thrillers, weird Westerns, ancient and religious epics, and nail-biters about rotten families and doomed heroes. Though he lived overseas for many years, Yordan emerged unscathed from the collapse of the Bronston film empire, and returned to the United States in the 1970s to live in San Diego, where he continues to churn out low-budget exploitation features.[*]

Oral history is not, strictly speaking, factual. Fact is increasingly presumptive in the realm of Hollywood history and hard to pin down amid so much

* According to Ephraim Katz, The Film Encyclopedia (New York: Perigree Books, 1979), p. 168: "[Samuel Bronston] made little impact until the late 50s, when he began producing spectacular epics in Spain. Early success encouraged him to invest in the building of enormous studios near Madrid; he was single-handedly responsible for putting Spain on the map as a center for international film production. But he borrowed heavily and overextended his investment and by 1964 was forced to suspend all business activities. The ensuing court litigations prevented him from further production."

conflicting rumor, gossip, legend, folklore, and reminiscence. A dozen people will tell tales of Harry Cohn's funeral, and who cracked wise what. The historian might attempt to organize the most plausible and narrowed-down scenario. The oral historian takes a kind of glee in the loose ends, in the cacophony and din.

Naturally, screenwriters get the benefit of the doubt here, and that may be cause, for some, for skepticism. Although the editor admits siding passionately with the writers' point of view and their generally unsung contributions, he also tries to be fair. Where an obvious or glaring error of fact has been detected, the correction has been noted in the text or footnoted.

The strength of a group portrait such as this lies, it is hoped, in the cross-weaving of viewpoints, in the chorus of voices, as well as in the close-ups of the individuals.

So there will be din and the cacophony, yes, some questionable assertions—and some clarion truth—as fourteen of the best screenwriters of their time recollect their lives, their careers, and the backstories of writing their motion pictures.

A Note on Credits

It is not a simple job to compile the filmography of a screenwriter, for as Richard Corliss has written in his indispensable book, Talking Pictures, "A writer may be given screen credit for work he didn't do (as with Sidney Buchman on Holiday ), or be denied credit for work he did do (as with Sidney Buchman on The Awful Truth )." Which is to say, there are irresolvable gaps in the best sources.

The American Film Institute's Catalog of Feature Films (1921–1930, 1961–1970) is incomplete for the years that are missing and not always reliable for the years that are covered. The joint project of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Writers Guild of America-West, Who Wrote the Movie (And What Else Did He Write)? (1936–1969), is less than authoritative. It overlooks movies written before the inception of the guild and toes the official guild line of accreditation thereafter. Consequently, excluded are many famous and not-so-famous instances of uncredited complicity. The blacklist years are riddled with aliases and omissions. And the guild maintains rules (disallowing screen credit to any director who has not contributed at least 50 percent of the dialogue, for example) that, while they may protect screenwriters, do not promote a full accounting of the screenplay.

The credits for this book were cross-referenced from several sources—those cited above, the New York Times and Variety film reviews, International Motion Picture Almanac and Motion Picture Daily yearbooks, A Guide to American Screenwriters: The Sound Era, 1929–1982 by Larry Langman (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1984) and The Film Encyclopedia by Ephraim Katz (New York: Perigree Books, 1979). In individual cases there was additional spadework by the original interviewers. As a final

resort, whenever possible, the interview subjects were confronted with the results of research and asked to add to or subtract from the list. Richard Brooks, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, Garson Kanin, Dorothy Kingsley, Curt Siodmak, and Stewart Stern all reviewed their transcripts and filmographies, clarifying aspects of their interviews.

As to specific claims and counterclaims concerning who wrote exactly what, there is another kind of cross-referencing to be done. The oral historian cannot always separate fact from factoid or opinion from the ax-to-grind. Likely there is much in this collection of reminiscences that contradicts, or is contradicted by, material in other books. Partly, such conflicting tales are to be expected of a branch of the film industry that has been relatively untapped for its perspective, where egos and careers have been so trampled. And partly such differences arise inevitably from individual points of view on a group enterprise.

Leigh Brackett: Journeyman Plumber

Interview by Steve Swires

She wrote that [The Big Sleep] like a man. She writes good.

Howard Hawks, quoted in Hawks on Hawks

In many ways, Leigh Brackett was the archetypal Howard Hawks woman. She was energetic, stubborn, self-sufficient, and self-deprecating, as were many of the female (and for that matter, male) characters in her scripts for Hawks' The Big Sleep (1946), Rio Bravo (1959), Hatari! (1962), El Dorado (1967), and Rio Lobo (1970), as well as for Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye (1973). Besides being one of the few successful women screenwriters, she was one of the earliest successful women science-fiction writers, having entered the field professionally in 1939. Her best-known character is the larger-than-life swashbuckling hero Eric John Stark, who first appeared in the pages of Planet Stories in the 1940s and who returned in a series of novels she wrote for Ballantine Books.

Brackett was married to the well-known science-fiction writer Edmond Hamilton, and they lived in Kinsman, Ohio, where, according to her husband, she spent her time "at a typewriter under the eaves of our old farmhouse, writing science fiction and mysteries, with frequent interruptions to run a tractor, clear paths in the woods, and spray the orchard." She also edited a collection of her husband's stories, titled The Best of Edmond Hamilton .

(This interview was conducted several years before her death and the post-humous release of The Empire Strikes Back, her final screen credit.)

Leigh Brackett (1915–1978)

1945

The Vampire's Ghost (Lesley Selander).[*] Story, co-script.

1946

Crime Doctor's Manhunt (William Castle). Script.

The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks). Co-script.

1959

Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks). Co-script.

1961

Gold of the Seven Saints (Gordon Douglas). Co-script.

1962

Hatari! (Howard Hawks). Script.

13 West Street (Philip Leacock). From her novel The Tiger Among Us .

1967

El Dorado (Howard Hawks). Script.

1970

Rio Lobo (Howard Hawks). Co-script.

1973

The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman). Script.

1980

The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner). Co-script.

Television credits include episodes of "Alfred Hitchcock Presents," "Checkmate," "Archer" and "The Rockford Files."

Books include No Good from a Corpse, Shadow over Mars (a.k.a. The Nemesis from Terra ), The Starmen (a.k.a. The Galactic Breed or The Starmen of Llyrdis ), The Sword of Rhiannon, The Big Jump, The Long Tomorrow, Eye for an Eye, The Tiger Among Us (a.k.a. 13 West Street ), Rio Bravo, Follow the Free Wind, Alpha Centauri—or Die!, The People of the Talisman/The Secret of Sinharat, The Coming of the Terrans, Silent Partner, The Halfling and Other Stories, The Ginger Star, The Hounds of Skaith, The Reavers of Skaith, The Best of Leigh Brackett, The Best of Planet Stories No. 1: Strange Adventures on Other Worlds (edited by Brackett), and The Best of Edmond Hamilton (edited by Brackett).

Brackett was a winner of the Western Writers of America Golden Spur Award and of the Jules Verne Fantasy Award. In her official Writers Guild résumé, she was also noted as "a proud Ohio potato grower."

Your first screenplays were for The Vampire's Ghost [1945], a "ten-day wonder" at Republic, and Crime Doctor's Manhunt [1946], part of the Crime Doctor series at Columbia. You went from those B movies to The Big Sleep,

* In the filmographies in this volume, the directors' names appear in parentheses following the titles.

directed by Howard Hawks, in 1946. How did you manage so prestigious an advancement?

The "ten-day wonder" was because my agent, Hugh King, had been with Myron Selznick, my agency at that time, and he had gone over to Republic as story editor and had sort of managed to shoehorn me in because they were doing this horror film. They decided to cash in on the Universal monster school, and I had been doing science fiction, and to them it all looked the same—"bug-eyed monsters." It made no difference. I did The Vampire's Ghost there, and just out of the clear blue sky this other thing happened, purely on the strength of a hard-boiled mystery novel I had published. Howard Hawks read the book and liked it. He didn't buy the book, for which I can't blame him, but he liked the dialogue and I was put under contract to him.

You worked on the screenplay of The Big Sleep with William Faulkner. I wouldn't say that you collaborated, but both of your names are in the credits as having written the script, along with Jules Furthman .

I went to the studio the first day absolutely appalled. I had been writing pulp stories for about three years, and here is William Faulkner, who was one of the great literary lights of the day, and how am I going to work with him? What have I got to offer, as it were? This was quickly resolved, because when I walked into the office, Faulkner came out of his office with the book The Big Sleep and he put it down and said: "I have worked out what we're going to do. We will do alternate sections. I will do these chapters and you will do those chapters." And that was the way it was done. He went back into his office and I didn't see him again, so the collaboration was quite simple. I never saw what he did and he never saw what I did. We just turned our stuff in to Hawks.

Jules Furthman came into it considerably later, because Hawks had a great habit of shooting off the cuff. He had a fairly long script to begin with and he had no final script. He went into production with a "temporary." He liked to get a scene going and let it run. He eventually wound up with far too much story left than he had time to do on film. Jules came in and I think he was on it for about three weeks, and he rewrote it, shortening the latter part of the script.[*]

If you try to watch the film as a standard mystery, fitting all of the clues

* Jules Furthman was classed as "damned good" by Howard Hawks, who ranked him in the company of Hemingway, Faulkner, and Hecht and MacArthur (see Joseph McBride's Hawks on Hawks [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982]). An ex-newspaperman, Furthman began doing screen stories in 1915, worked regularly with directors Hawks and Josef von Sternberg, and has credits on such vintage films as Underworld (1927), Morocco (1930), Shanghai Express (1932), Blonde Venus (1932), Bombshell (1933), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), Come and Get It (1936), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), The Shanghai Gesture (1941), The Big Sleep (1946), Nightmare Alley (1947), Jet Pilot (1957), and Rio Bravo (1959).

together to logically develop a hypothesis as to who the murderer might be, you find yourself continually frustrated by the narrative development .

I think everybody got very confused. It's a confusing book if you sit down and tear it apart. When you read it from page to page, it moves so beautifully that you don't care, but if you start tearing it apart to see what makes it tick, it comes unglued. Owen Taylor, I believe, was the name of the chauffeur. I was down on the set one day and Bogart came up and said, "Who killed Owen Taylor?" I said, "I don't know." We got hold of Faulkner and he said he didn't know, so they sent a wire to Chandler. He sent another wire back and said: "I don't know." In the book it is never explained who killed Owen Taylor, so there we were.

In writing your portion of the screenplay, did you have any concept in mind of the role of the private eye as an archetypal hero?

I don't think I dissected it that much. I was very much under the spell of Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, and I have written a few stories myself in that same vein. Something struck me. I liked it and I felt it, but I don't think I really analyzed it as I might do now, but I was a lot younger then. I just sort of accepted it.

Are there contributions you made to the characterization of Philip Marlowe which are distinct from Hawks'?

I don't know that I contributed too much to Marlowe, because I was taking directly from the book. This was the bible, and I wouldn't dream of changing it. I think that the characterization of Marlowe as done by Bogart and directed by Hawks was entirely their own. On the other hand, I think Bogart was ideal and, as far as I was concerned, he was the greatest actor that ever happened. I adored him. Actually, it was a joy to watch him on the set because he was stage trained. On a Hawks film nobody gets their pages until five minutes before they're going to shoot. Bogart would put on his horn-rims, go off in a corner, look at it, and then he'd come back on the set and they'd run through it a couple of times, and he'd have it right down, every bit of timing, and he'd go through about fourteen takes waiting for the other people to catch up to him.

I don't like to say this, because it sounds presumptuous, but Hawks and I kind of tuned in on the same channel with regard to the characters, and I think this is probably one reason that I worked with him so long. He was able to get out of me what he wanted because I had somewhat the same attitude towards the characters as he did.

There is a revisionist effort popular with such critics as Pauline Kael and Richard Corliss to consider the work of the screenwriter in contrast to the auteur theory, which postulates the director as the author of the film. When you look back on the movies that you wrote for Hawks, do you see them as Leigh Brackett films or Howard Hawks films or as collaborations?

It's a collaboration. The whole thing is a team effort. A writer cannot

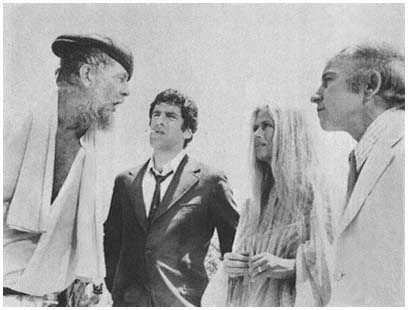

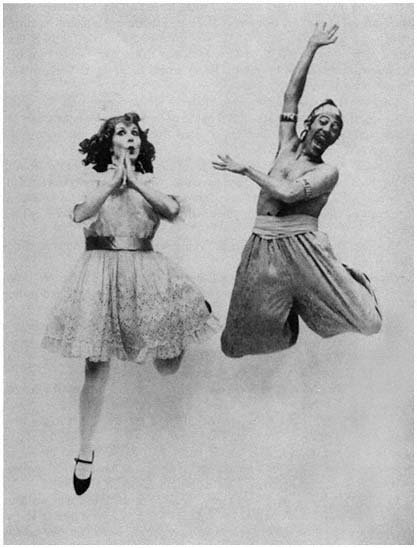

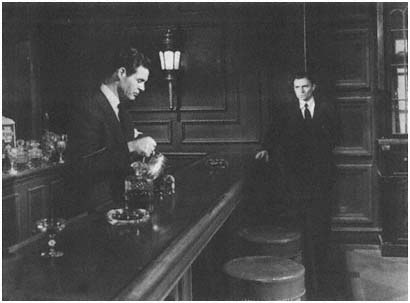

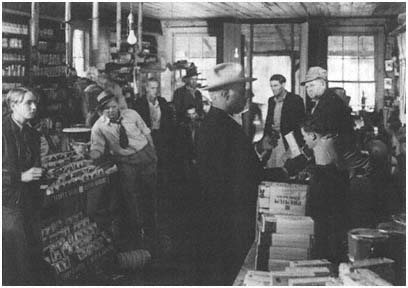

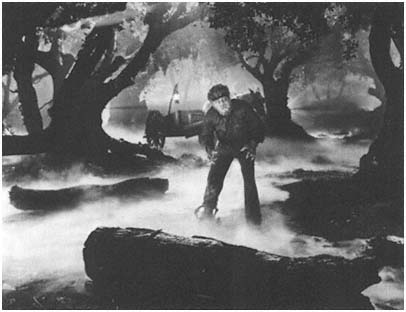

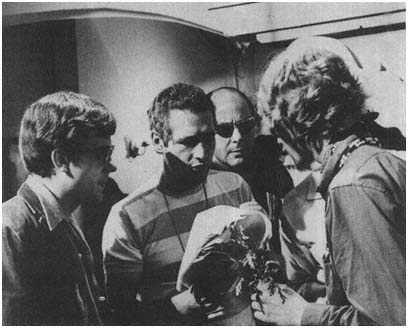

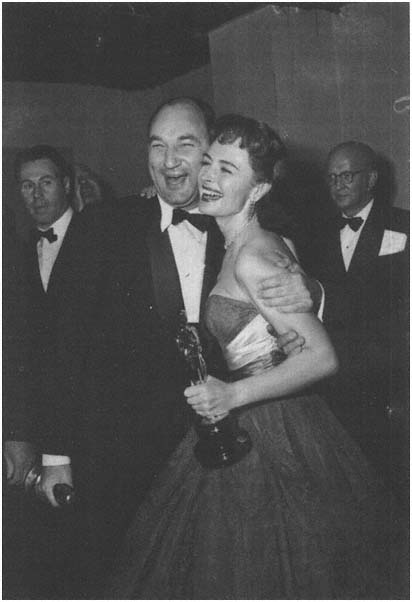

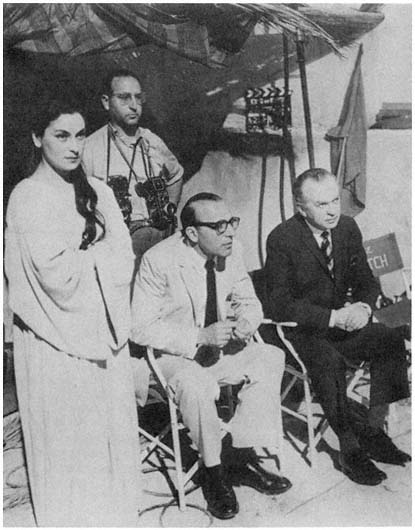

"Tuning in to the same channel": Leigh Brackett and director Howard Hawks at

work on Rio Bravo (Photo: Museum of Modern Art)

possibly, when he's writing a film, do exactly what he wants to do as when he's writing a novel. If I sit down to write a novel, I am God at my own typewriter, and there's nobody in between. But if I'm doing a screenplay, it has to be a compromise because there are so many things outside a writer's province. Hawks was also a producer, and he had so many things to think about that had nothing to do with the creative effort—with the story—like cost and budget and technical details that you must learn to integrate. You cannot possibly just go and say: "Well, I want to do it thus and such and so,"

because presently they say: "Thanks very much and goodbye." it just has to be that way.

You came out of the tradition of the pulp magazines, where you were allowed a degree of creative control. How did you react to having less control over your work in Hollywood?

I sort of went off into corners and wept a few times at things that made me very unhappy. I think the hardest thing about adapting to working with other people was that. Because I was a fiction writer primarily, and I was used to writing in a little room with the door shut, just myself and the type-writer—all of a sudden I'm sitting in this room with film people and I've got to talk ideas. God I froze. Everything I was about to say sounded so dreadful. It took me quite a few years to adapt and also to learn my craft, because I don't think there's anything better than screenwriting to teach you the construction of a story.

I was very poor on construction when I first began. If I could hit it right from the first word and go straight through, then it was great. If I didn't, I ended up with half-finished stories in which I had written myself into a box canyon and couldn't fight my way out. In film writing you get on overall conception of a story and then you go through these endless story conferences. Hawks used to walk in and he'd say: "I've been thinking . . ." My heart would go right down into my boots. Here we go: Start at the top of page one and go right through it again. But you still have to keep that concept. It's like building a wall. You've got the blocks, and you've got the wall all planned, and then somebody says: "I think we'll take this stone out of here and we'll put it over there. And we'll make this one a red one and that one a green one." You're still trying to keep the overall shape of the story, but you're changing the details. It took me a long time, but I finally learned how to do it. It was exhausting.

One of the observations gleaned from an auteur-oriented examination of Hawk's films is that certain sequences keep repeating themselves, being remade in different settings with different actors. For example, the scene in The Big Sleep where the gangster is in the house with Bogart and Bacall while his henchmen are waiting outside. Bogart throws him out and hawks cuts to a shot of the door being riddled with bullets. That scene is reshot in El Dorado where John Wayne throws a cowboy out of a saloon and Hawks again cuts to a shot of the door being riddled with bullets from the henchmen waiting outside. Your wrote the screenplay for El Dorado. Did you do that deliberately, or was that Hawks?

That was Hawks. I have been at swords' points with him many a time because I don't like doing a thing over again, and he does. I remember one day he and John Wayne and I were sitting in the office, and he said we'll do such and such a thing. I said: "But Howard, you did it in Rio Bravo . You don't want to do this over again." He said: "Why not?" And John Wayne,

all six feet four of him, looked down and said: "If it was good once it'll be just as good again." I know when I'm outgunned, so I did it. But I just don't like repeating myself. However, I'm wrong about half the time.

El Dorado is virtually a remake of Rio Bravo, with a certain reversal of characters . In Rio Bravo, John Wayne is the upstanding sheriff and Dean Martin is the drunken gunfighter . In El Dorado John Wayne is the upstanding gunfighter and Robert Mitchum is the drunken sheriff . Why bother to make El Dorado when you had already made the definitive version of that story in Rio Bravo?

I wrote the best script I have ever written and Howard liked it, the studio liked it, Wayne liked it, and I was delighted. We didn't make it, because he decided to go back and do Rio Bravo over again. It could have been called The Son of Rio Bravo Rides Again . I wasn't happy, but I did the best I could to make it a little different. Amazingly enough, very few people, except film buffs, caught the resemblance. I thought, my god! The critics will clobber us, because we did this before, practically word for word. The scene where Jimmy Caan threw himself in front of the horses we had done in Rio Bravo, but it was cut out of the final print because the final print was overlength. I said: "Howard, you can't do that. Warner Brothers owns it." He said: "All right, I'll buy the rights back." So what can you do?

Of the two, Rio Bravo was infinitely better cast . Arthur Hunnicutt in El Dorado played what was essentially Walter Brennan in Rio Bravo, but his performance is in no way comparable . Brennan as "Stumpy" is one of my favorite film performances, and was certainly of Oscar calibre .

He deserved it. Arthur Hunnicutt is a nice man and a good actor, but he's not Walter Brennan. When we began working on Rio Bravo we were harking back to To Have and Have Not [also directed by Hawks, 1944], in which Brennan played a similar character. We took him off a boat and put him in a Western town. That didn't work too well, so it got gradually worked around, after about the fourth or fifth version of the screenplay. Howard has a certain number of things that are very important to him. Usually the relationship between two men is a love story between two men. The obligations of friendship—what a friend is required to do for a friend. I suppose if you look at it, there are great resemblances.

You also helped write the screenplay for Hawks' last film, Rio Lobo. There are sequences in it which are in his earlier pictures, so for a third time he reshot some of the same scenes .

I didn't do the original script. Hawks asked me to work on it in the beginning, but I said: "I'm sorry. We're leaving for a trip around the world tomorrow, so I can't." Instead he got Burton Wohl. I came in on it, actually, as a rewrite. Not being used to working with Hawks, Mr. Wohl had some difficulty adjusting. Howard drives writers right up the wall. He will throw you a whole bunch of stuff and say: "This is what I want." And then he goes away

and you don't see him again for weeks. He leaves it to you to fit it all together and make a story out of it. He doesn't go into all the ramifications of motivation—that's what he's paying you for.

Writers get very confused. Most of what I did on Rio Lobo was to try and patch over the holes. If these people ride into town and go into the saloon and shoot somebody—why? Nobody knows. And you try to figure out why. So that was mostly what I did. I was unhappy that he went back to the same old ending of the trade, because it was done beautifully in Rio Bravo and done over again in El Dorado . As Johnny Woodcock, the film editor, said, "We get better at this every time."

I'd like to get your observations on working with John Wayne . When I interviewed [director] Mark Rydell at the time he was promoting Cinderella Liberty [1973], he shared an anecdote with me about the filming of The Cowboys [1972] . He noticed that, on the set Wayne became very friendly with Roscoe Lee Browne, who is a man of impeccable taste and sophistication. They would sit around quoting poetry to each other and sharing their love for the classics. Did you find any unexpected qualities in Wayne's personality?

I don't think I ever quite came across that facet of his personality. I didn't ever work too closely with him. On Hatari! they went to Africa for a number of months and came back with magnificent animal footage, but there was no people story. Of course, I had written five scripts, but none of them was the script, as it were. That was the year that Howard was not buying any story. He didn't want plot; he just wanted scenes. So I wrote ahead of the camera.

Normally, once a picture starts shooting, a writer's job is finished. He doesn't have anything to do with the people. But I was on the set with Duke, and to a certain extent, for a short while, on El Dorado as well. He is a highly professional actor. He is quite without [an arrogant] side. He's been the number one box office star for God knows how many years, but he doesn't come on that way. He's just there to do his job and do it as best he can.

I remember him working with the baby elephant in the scene at the end of Hatari!, where the critter gets on the bed and it crashes down. They tried about eighteen takes, and he said: "He's doing it right, I'm not." The elephant had his cues down perfectly, but it was Duke who was blowing it. He's a much more complex person than people give him credit for being.

What do you think of the Westerns that have been made in recent years, coming after the classic work of Ford and Hawks?

Every once in a while I go back and read a little Western history, which is a marvelous corrective. Hollywood has created a totally mythic West, which never existed on land or sea. The whole concept of the hero, I think, began with Owen Wister's The Virginian, more or less. Ever since, there's been a too great feeding on oneself. When you utilize the same elements over and over, you finally begin to turn out excrement. The trouble is we've gotten away from what actually happened in the West. I wish that somebody would

just read a little history. The pioneers were hardworking people who worked like mad to scratch to stay in one place. It was a hard, cruel country out there. These were heroes in a different sense, because they fought however they could to hold onto what they had. They didn't worry about who drew first. They just went up from behind with a shotgun. The idea was: "Don't get killed yourself—kill him."

Of course, I like the Hollywood Western because it's fun, but I think that some people are taking it far too seriously, because they're not dissecting anything real to begin with.

From what you've said, it sounds as though it was a very lively atmosphere around the sets of the Hawks films, with his spontaneously creative working habits. It must have prepared you, then, for Robert Altman, who I understand also likes not to inform the cast as to what they'll be shooting the next day. In fact, many times he doesn't bother to worry about it himself. How were you brought into the project of writing the screenplay for The Long Goodbye?

Elliott Kastner, who was the executive producer, used to be my agent at MCA a long time ago and we're good friends. He remembered The Big Sleep and he wanted me to work on The Long Goodbye . He set the deal with United Artists, and they had a commitment for a film with Elliott Gould, so either you take Elliott Gould or you don't make the film. Elliott Gould was not exactly my idea of Philip Marlowe, but anyway there we were. Also, as far as the story was concerned, time had gone by—it was twenty-odd years since the novel was written, and the private eye had become a cliché. It had become funny. You had to watch out what you were doing. If you had Humphrey Bogart at the same age that he was when he did The Big Sleep, he wouldn't do it the same way. Also, we were faced with a technical problem of this enormous book, which was the longest one Chandler ever wrote. It's tremendously involuted and convoluted. If you did it the way he wrote it, you would have a five-hour film.

I worked with another director who was on it before, Brian G. Hutton. He had a brilliant idea which just didn't work, and we wrote ourselves into a blind alley on that. It was a technical problem of plotting—the heavy had planned this whole thing from the start. So what you had was a prearranged thing where everybody sort of got up out of several boxes and did and said exactly what they had to do and say in order to get you where you had to be. It was very contrived and didn't work. Brian had to leave because he had another commitment, so when Altman came onto it I went over to London for a week. He was cutting Images [1972], which was a magnificent film—beautiful, powerful. We conferred about ten o'clock in the morning and yakked all day, and I went back to the hotel and typed all the notes and went back the next day. In a week we had it all worked out. He was a joy to work with. He had a very keen story mind.

Mark Rydell played the character Marty Augustine in The Long Goodbye.

He is an old friend of Altman's, so I imagine they were able to work together more easily. Rydell claimed that he knew intuitively what Altman' s conception of the movie was, which many critics, as well as many members of the audience, missed—the satirization of the genre of the private-eye film, by placing the conventions of the forties in direct conflict with the realities of the seventies. Were you aware of Altman' s intentions during your story conferences?

Actually, I was more aware of the construction of the thing, which is more my department. What he does with it after he gets the script is something else again. I don't think I was quite as aware of the satire as I became later.

Jay Cocks of Time magazine accused Altman of mocking "an achievement to which at his best he could only aspire," because he tried to demythologize Philip Marlowe. I imagine a lot of critics who are in their forties and fifties now grew up with the myth of Bogart as Marlowe, and hated to see the end of the film in which Marlowe murders Terry Lennox with no remorse. In fact, after he commits the murder, he dances down the road whistling "Hooray for Hollywood!" You are responsible, to some degree, for helping to create and propagate that original myth with The Big Sleep. Then you turned around and helped to sabotage it in The Long Goodbye. Do you consider that a betrayal of your earlier values?

No. Actually the ending, where Marlowe commits the murder, was in the script before Altman came onto it. The ending of the book was totally inconclusive. You had built up a villain. You feel that Marlowe has been wounded in his most sensitive heart, as it were—he's trusted this man as his friend; the friend has betrayed him. What do you do? We said let's just face up to it. He kills him.

In the time that we made The Big Sleep you couldn't do that because of censorship, had you wanted to do it. We stuck very closely to Chandler's own estimate of Marlowe as a loser, so we made him a real loser—he loses everything. Here is the totally honest man in a dishonest world, and it suddenly rears up and kicks him in the face, and he says: "The hell with you." Bang! I don't know whether we were right to do it, but I don't regret having done it. It felt right at the time. This was the way it turned out.

What do you think of the conceptions and characterizations of Marlowe as portrayed in the other film versions of Chandler's novels?

I thought Murder My Sweet [1944] was a beautiful film. The others all had points of excellence and also points where they didn't quite come across. The experimental business of "I am a camera" in Lady in the Lake [1946] didn't work too well.

It has been said that Philip Marlowe was sort of the son of Sam Spade. As Chandler said: "Down these mean streets must go a man who is not himself mean." In other words, here is the knight in shining armor with a shabby trench coat and snap-brim felt hat. I think he is a universal folk hero who does not change down through the ages except in the detail of his accoutre-

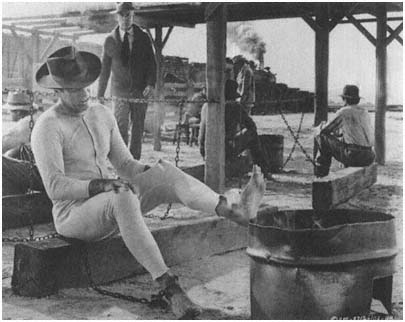

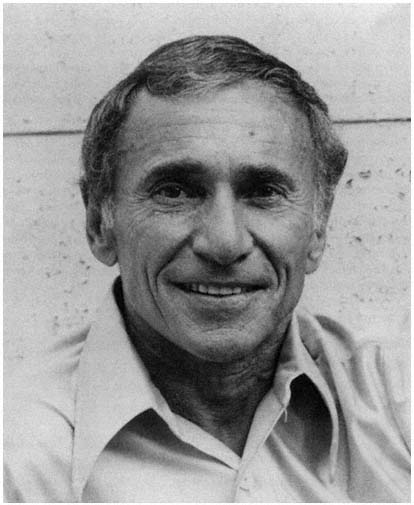

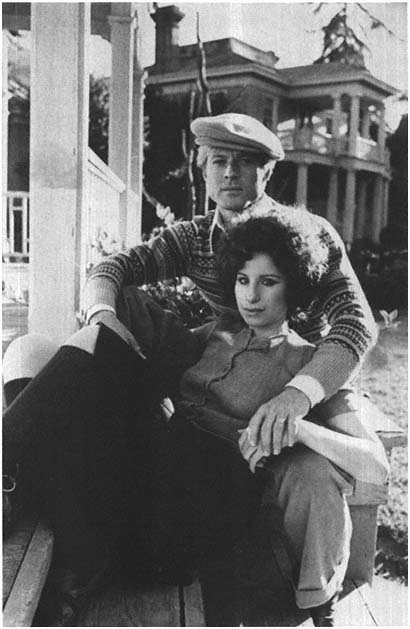

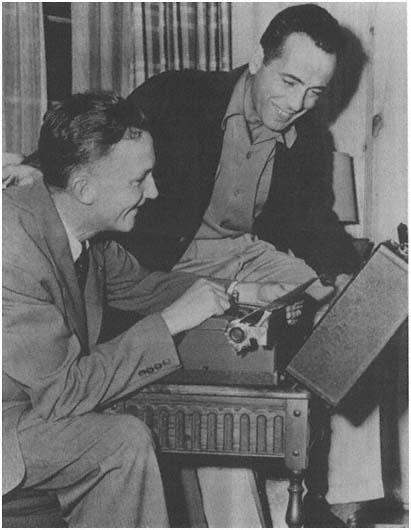

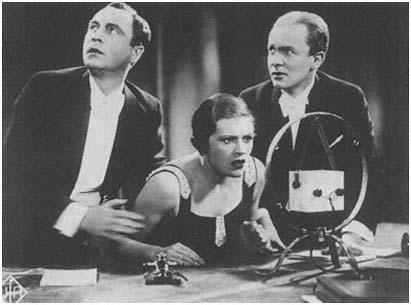

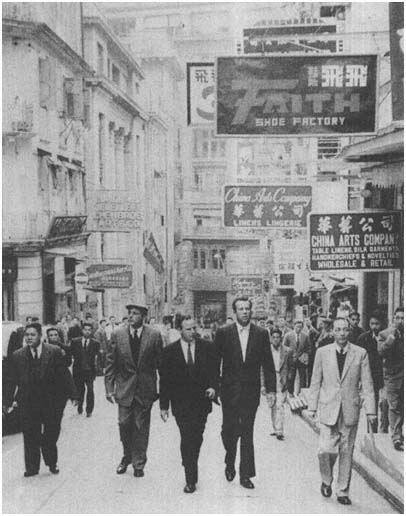

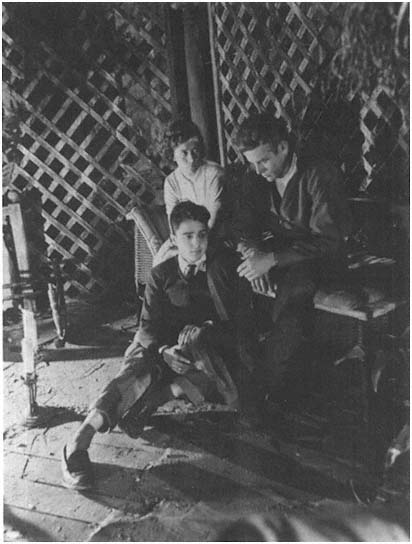

"A real loser": Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) with Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden, at

left), Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt), and Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson) in the 1973

version of Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye . Leigh Brackett updated the

quintessential 1940s private-eye novel for director Robert Altman's film.

ments. He's not carrying a sword but a .32 automatic. The essential is that here is a man who is pure in heart, who is decent and honorable and cannot be bought—he is incorruptible. I think the concept was damn good, a very moral concept.

What did you think of Gould's performance, miscast as he was?

I thought he did a beautiful job. However, the thing about Elliott is that he isn't tough. His face is gentle, his eyes are kind, and he doesn't have that touch of cruelty that you associate with these characters.

With all of the disappointments that you've suffered—having your scripts revised without your approval to produce inferior versions of previous pictures—will you continue to write screenplays? Is there anything on the horizon that we can look forward to?

There's nothing definite at the moment. I have an original Western screenplay out and around, and I'm hopeful. It's a comedy. There are a number of things on the fire with television. As you know, the whole picture has changed out there very greatly in recent years. You grab what you can get. I wrote a script for "The Rockford Files" that was telecast last season.

But I greatly enjoy the work. It's a challenge. It's more technical than creative. What you have to be is a very good journeyman plumber and put the parts together. And then, if you can still inject a little bit of something worthwhile, you've done as much as can be expected.

Richard Brooks: The Professional

Interview by Pat McGilligan

He [Richard Brooks] was a strong, tough, agile man of about forty-two years who looked and dressed like a bum most of the time because he hated the codes of the front-office contingent. But were those flashes of street survival instinct that dominated his personality in unexpected moments the real Richard Brooks, or were they a meticulously nurtured camouflage that a forceful personality had chosen in order to ward off, and forever frustrate, simple definitions of itself? Puzzlement. Yet could he not be both?

Sidney Poitier, writing in This Life about meeting Richard Brooks before the filming of The Blackboard Jungle

Sunset Boulevard. Driving west. Pass the Beverly Hills Hotel. Turn right on Benedict Canyon. Big houses for big movie stars. Another mile. Up there to the left, where Manson's gang committed bloody murder one night—beautiful Sharon Tate.

A traffic light. Turn off Benedict Canyon. Finally, a stone wall. Behind it a two-story stone house. Ring the doorbell.

Richard Brooks opens the door. Old sweat pants, faded, wrinkled old T-shirt with the MGM lion.

Quiet. First thing you notice: the quiet. No TV, no voices, no sounds.

Then the books. Every wall: books. Thousands of them. Room after room. Dictionaries: Italian, German, French, Swahili. Books on or about religion, science, crime, theater, movies, dance, fables, fiction.

"Big house."

He doesn't answer.

"Who else lives here?"

"Nobody."

"No woman, children, not even a dog? You look like a man, who—"

"Yeah. I love dogs. But who'd take care of a dog when I'm working? On location? You think I'd condemn my dog to a kennel?"

We settle in the kitchen. I plug in my tape recorder. Brooks gets a bottle of Akvavit from the freezer.

We talk and drink.

Born in the slums of South Philadelphia. Immigrant parents. Both worked in a factory. Learned to read and write from newspapers. The Bulletin and the Inquirer . The family moved to West Philly.

He was an "only" child. He went to grade school. They worked six days a week. He didn't see his parents except maybe half an hour at night. And Sunday. He was a street kid. A loner then. A loner now.

Finally started high school. Parents moved. Went to trade school. Learned carpentry. Parents moved. Went to a different high school. Graduated: 15 years old. Worked that summer in a gasoline station. On Saturday another job. Usher in the Earle Movie Theatre on Market Street.

Then, the big time—Temple University. School of Journalism.

Then—disaster. Stock market crash. The big Depression. One parent fired. Family struggling. No money for college. Two semesters a year, about $250 for each semester. Big money. Too much for this family. He left Temple at the start of his senior year. He tried to get a job on the Bulletin . They were firing, not hiring. Same story at all the papers.

One morning he left a note for his parents, hopped a freight train, and left town, heading west to find a job. About two years on the road. Hard times. Hundreds of people for every job.

Drove a truck in Missouri. Washed dishes. Restaurant in Arkansas. Dug irrigation trenches in Oklahoma. Picked cotton in Texas. Fixed flats. Gas station in Nebraska. Two hard years. Living day to day. Rescued from a hundred freezing nights by the Salvation Army. Hot soup. A cot and a blanket. And they deloused your clothes.

Sold a few stories to newspapers. Learned about survival. Learned, too, about farmers and workers and housewives who refused to quit in the face of a killer Depression, with absolute faith in themselves and in America.

Another winter coming. Grabbed a fast freight. Unloaded in York, Pa. Hitchhiked into Philly. Within a week landed a job with the Philadelphia Record . Sports department. Eight dollars a week, covering high school sports. Hired on for one year. Heard about a job in Atlantic City. Hit the road. Landed a job on the Press Union . Sports. Ten dollars a week. Occasional features brought an extra couple of bucks. One year. Clean room with a toilet down the hallway.

Finally: New York. Every writer's dream. The New York World-Telegram . Crime news. Special assignments. Within a year: Radio. WNEW. On the air 24 hours a day. Played records 23 of those hours. The "Make-Believe Ball-

room" and "The Milkman's Matinee." WNEW needed a newsman. He was it. Then NBC. Blue Network. News.

1939. World War II. Europe, Africa, Asia were in it. We'd be in it soon.

1940. He wanted to see California before the war got him. Drove west in a secondhand old ratty car. Same route he had taken by freight car once.

Los Angeles. Lotusland. Sunshine. Grapes, oranges. Hollywood Boulevard. Grauman's Chinese Theatre. Magic of the movies.

Corner of Sunset and Vine—NBC. Didn't need another newsman. Had a spot open on their Blue Network. Fifteen-minute shot, five times a week. They wanted an original story complete, not a serial, written and read by the same person. Twenty-five dollars a day. Two hundred and eighty stories and a year later, ready for a change.

Universal Studios needed a rewrite on White Savage (1943) starring Maria Montez, Jon Hall, and Sabu. Six days' work. One hundred dollars and a shared screen credit: Additional dialogue by. Rewrite on Cobra Woman (1944) starring Montez, Hall, and Sabu. A few chapters of a serial: Don Winslow of the Coast Guard (1943).

Orson Welles' "Mercury Theatre on the Air." Not more money but a helluva lot more respect.

A couple more scripts at Universal.

Joined the Frank Capra Motion Picture Unit as a civilian. Documentaries. The Why We Fight series created for the U.S. Army. Prelude to War, Battle of China, Battle for Britain, Battle of Russia, War Comes to America, etc.

Pearl Harbor attack.

1943. Joined the U.S. Marine Corps. Boot camp in San Diego. Then to Quantico, Va. Attached to 2nd Marines, Photographic Section. Learned to fight. Assembled combat film into documentaries. Marines in action: Battle of Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, The Marianas Islands, etc.

During the next two years, he also wrote a novel. Wrote it at night. Wrote it in the "head" with forty gleaming toilet bowls as witnesses.

Sinclair Lewis wrote: "The Brick Foxhole is a powerful, shocking tale about soldiers fighting the war from a stateside barracks. For them it became a war without meaning. Their driving force was hate. Hatred for Negros and Jews and Catholics and especially homosexuals. Hatred, finally, for each other and themselves. It's a blistering novel you'll never forget."

The Brick Foxhole became Crossfire (1947). The antihomosexuality became anti-Semitism. Brooks returned to Hollywood with a job offer from Mark Hellinger, a former journalist with a reputation as the producer of hard-hitting films.

Worked in Hellinger's stable. (Later, after Hellinger's untimely death, he wrote a first-rate novel about someone similar to Hellinger, titled The Producer .) Successful collaboration (particularly with John Huston). A writer-

director contract at MGM. A decade of worthwhile projects that are distinguished by their literary roots, their social edge, their deeply felt emotionalism.

Then Brooks struck out on his own, producing as well as directing, and turning to such vaunted and disparate literary properties as Sinclair Lewis' Elmer Gantry (1960), Joseph Conrad's Lord Jim (1965), and Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (1967).

In time came The Professionals (1966), a thoroughly satisfying Western that is a metaphor for his own professional code; and the offbeat genre variations $/Dollars (1971) and Bite the Bullet (1975), which, though somewhat less successful, had humor, style, and—something to be expected in any Brooks film—bite.

In general, a remarkable oeuvre, combining the finest entertainment values with personal high principle. Hallmarks as a writer: ringing dialogue, provocative characterizations, challenging material, and superior script orchestration. As a director: high visual standards and a consistently engaging, expressive camera style.

Many of the Brooks films were considered impossible, unfilmable, in their day. A novel by Dostoevski (The Brothers Karamazov) was not only formidable in length and content, it was unavoidably "Russian" at the height of the Cold War. Something of Value (1957) dared to confront colonialism in an era that still embraced colonialism. Elmer Gantry outraged religious groups and, in an era that has seen the undoing of some scurrilous television evangelists, is still exceedingly apt.

He has demonstrated a passion for exploring themes of guilt, responsibility, and justice, the relationship between upbringing and antisocial behavior. The Blackboard Jungle, in 1955, with its gritty verisimilitude and social pleading, was only the first of Brooks' trilogy of adaptations of bestsellers about the roots of violent crime. In Cold Blood and Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977) were to follow, over the next two decades, each film in the triology becoming more difficult and controversial.

Like other screenwriters who came to the fore in the 1940s, Brooks did not write about himself or his life overtly—the ego was always submerged. Yet obliquely (as in The Catered Affair, in 1956, which Brooks directed only and whose script is by Gore Vidal from a television play by Paddy Chayefsky) or more expressly (as in The Happy Ending, in 1969, which was Brooks' conception from start to finish—a somber prefeminist fable about love, marriage, and alcoholism, starring his then wife, actress Jean Simmons), the thread of autobiography is there. If there is a recurrent motif in his films, it is one that is organic with his life story—that of the self-made man who, caught up in some crisis, must answer to himself.

In recent years, with Hollywood in flux and in the grip of ever-changing executive hierarchies, Brooks has worked less often and less momentously,

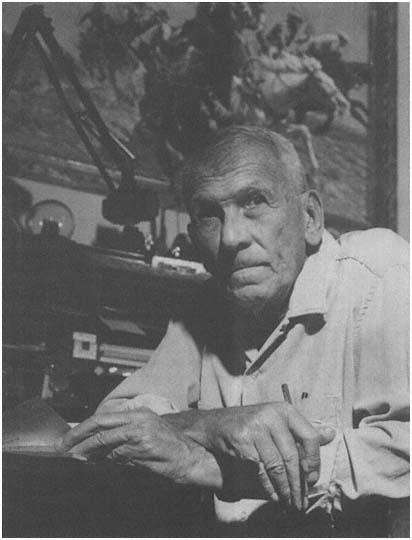

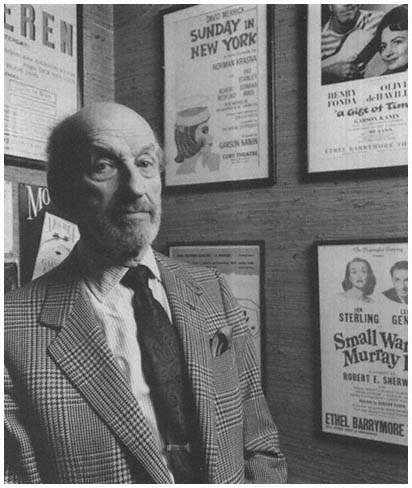

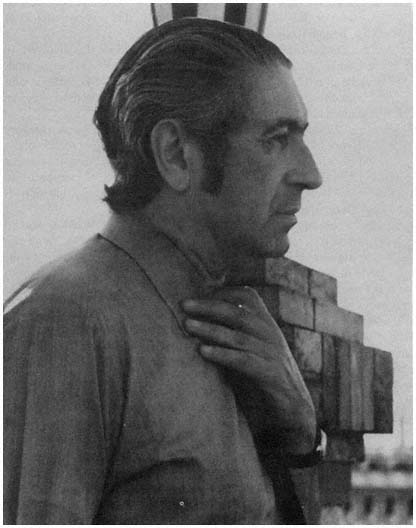

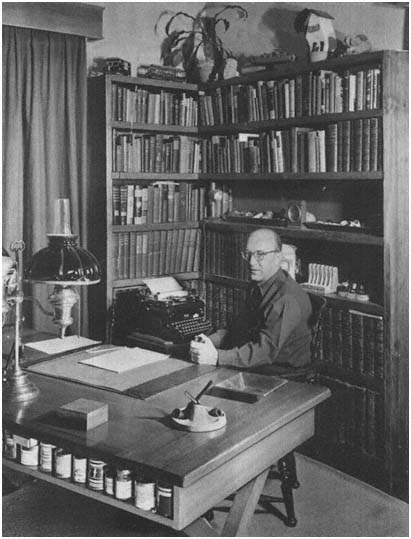

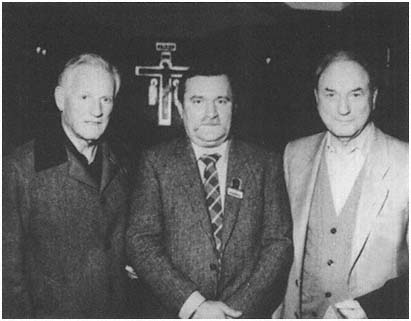

Richard Brooks in Los Angeles, 1988. (Photo: Alison Morley)

which has hurt his standing with the contemporary critics. (One film, Fever Pitch, in 1985, was taken away by the producers and recut, the worst insult.) Once the ultimate studio man, he has become ferociously independent; the secrecy of his scripts is zealously guarded; and (more so than while at MGM) he takes on obsessive hand in the postproduction.

Not in the least casual about this interview, Brooks labored over the tran-

script as if it were footage of a Brooks film to be edited. All to the good—it must be said that this ex-newspaper reported, now in his mid-seventies, took me to school with his editing, changes, and criticisms.

Richard Brooks (1912–1992)

1942

Men of Texas (Ray Enright). Additional dialogue.

Sin Town (Ray Enright). Additional dialogue.

1943

White Savage (Arthur Lubin). Script.

Don Winslow of the Coast Guard (Ray Taylor, Lewis D. Collins).

Serial, additional dialogue.

1944

My Best Gal (Anthony Mann). Story.

Cobra Woman (Robert Siodmak). Co-script.

1946

Swell Guy (Frank Tuttle). Script.

The Killers (Robert Siodmak). Uncredited contribution.

1947

Brute Force (Jules Dassin). Script.

Crossfire (Edward Dmytryk). Adapted from his novel The Brick Foxhole .

1948

To the Victor (Delmer Daves). Story, script.

Key Largo (John Huston). Co-script.

1949

Any Number Can Play (Mervyn LeRoy). Script.

1950

Crisis (Richard Brooks). Script, director.

Mystery Street (John Sturges). Co-script.

Storm Warning (Stuart Heisler). Co-story, co-script.

1951