Preferred Citation: Hoskins, Janet. The Play of Time: Kodi Perspectives on Calendars, History, and Exchange. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0x0n99tc/

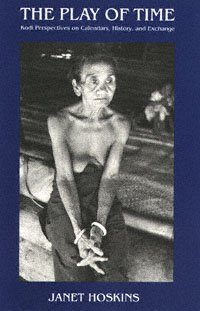

| The Play of TimeKodi Perspectives on Calendars, History, and ExchangeJanet HoskinsUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1997 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Hoskins, Janet. The Play of Time: Kodi Perspectives on Calendars, History, and Exchange. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0x0n99tc/

PREFACE

Our time on this earth. . . .

Ghica pimoka la panu tana

Resting for a moment as we stand

Li hengahu ndende mema

Catching our breath as we sit

Li lyondo eringo mema

Before the tide goes down at dusk

La lena ndiki myara

Before the river sinks to meet the sea

La nggaba kindiki lyoko

The stick cannot be extended

Kaco njapa dughuni kiyo

any more

The rope cannot be made any longer

Kaloro njapa lamenda kiyo

Excerpt from a

Kodi death song

The shortness of human lives is a fact of time and of each person's experience. The measurement of time derives its poignance from the inevitable end to each biographical cycle. The cultural value placed on time begins with the shared significance of our own mortality.

This book is an ethnography of the cultural perception and organization of time in an Eastern Indonesian society. I begin with the collective construction of the past through the model of the calendar. The yearly cycle, apprehended in days, months, and seasons, is synchronized by a calendrical priest, the Rato Nale or "Lord of the Year," who coordinates agricultural activities and their ritual stages. His task, together with the implements associated with its performance, is seen as partially imported from a distant island to the west. But it is given a local meaning that makes the naming of the months and the "New Year" festival of the sea worms into the mark of a distinctly Kodi identity.

The collective, encompassing structure of the calendar provides a form of repeated, reversible time in which human lives can be inscribed. Bio-graphic time, a second form of temporality, moves through these cycles to spotlight unique and irrevocable events, forming chains that leave their mark on houses, villages, and landscapes. This time is not totalizing but particular: it constitutes the value of objects and animals by measuring the investment of human lives in producing and conserving them. Acting

subjects distribute their biographies in different directions, striving for a sort of immortality both through acts that will remain in memory and descendants who will repeat their names in invocations. Their movements are restrained by the calendar, but they are not part of the annual cycle. They embody a cumulative, irreversible time that ties the past to the present and extends into an uncertain future.

The time of the calendar relates human lives to the rhythms of the natural world, the movement of celestial bodies, and the order of the cosmos. Biographic time binds persons to things, to localities, and to other groups of persons through the experience of living and remembering the past. More recently, a third sort of time has been added to locally generated temporalities by the intrusions of colonial conquest, the new Indonesian nation-state, and Protestant and Catholic missionization. This new temporality has shifted the relations of power by presenting a modern, secular, and universal measurement of time—in printed calendars, clocks to record the passage of hours and minutes, and books to trace the succession of historical periods and epochs. In this way, a diversity of different temporal systems is made subservient to a single, overarching system, internally consistent but no longer sensitive to local variations in meaning and sense.

Local systems of time reckoning were struggles against mortality, attempts to preserve a sense of a continuing heritage over the generations by giving a vast authority to the past and to the ancestors. Precedents established in the past were used to validate present actions by calling up a complex repository of images. These "images of the past" were not, however, used simply to replicate what had happened earlier. Rather, they were debated and reflected upon in order to select those that provided patterns worthy of repeating, precedents to guide future innovation. The past was not merely the residue of earlier acts, "history turned into. nature" as a simple "habitus" (Bourdieu 1977). It was dialectically involved with the present and offered an alternative model of potentialities to be realized.

This book makes three different arguments in each of its three sections. In part one, I argue for the complexity of the past, the many different ways in which it is represented in narratives, objects, and actions. All of these representations contribute to a collective heritage that is invested, as a whole, in the indigenous calendar, but none is determinate or absolute in its authority. A study of the collective construction of the past reveals its flexibility and diversity, its openness to multiple interpretations.

In part two, I make the case that time is constitutive of value through an accumulation of biographical experience invested in objects, places, animals, and events. "Value" here is directly related to the perception of

human mortality and efforts to construct a ritual order in which—al-though people still die—something of what they stood for is allowed to live on after them. This notion of value is used in all forms of traditional exchange but today is being increasingly challenged by external forces that propose other standards of value, measuring these values with money, clocks, and schedules.

Part three examines the confrontation of a local heritage that emphasizes the continuity of tradition with a notion of "history" as a progressive series of unique, irrevocable acts. Temporal directionality is here removed from the local context and placed on a global stage. It comes with an awareness of the loss of autonomy and the danger of a loss of diversity as well, as disparate regional voices are increasingly silenced or displaced by the universalizing discourses of church and state.

The book explores three different approaches to the study of time: the "totalizing" approach, in which time is seen as a dimension of a more encompassing classification system, whose origin is social; "practice" theory, in which time is viewed as a strategic resource, manipulated by particular actors in specific contexts; and the "historicist" approach, which emphasizes how time has changed relative to the different values accorded to past, present, and future.

The first mode, established by Henri Hubert's early essay on temporal representation in religion and magic (1909), was continued in the work of Emile Durkheim ([1912] 1965) and in much of British social anthropology (Evans-Pritchard 1940; P. Bohannan 1967). In Eastern Indonesia, it achieved its most complete synthesis in the seminal comparative study of F.A.E. Van Wouden, who tried to demonstrate the essential "unity of culture" in which myth, rite, and social structure were all exhibited in the "rhythmic character of time" ([1935] 1968, 2). Insights from this tradition formed the basis of structuralist analysis, as well as of a series of essays by Edmund R. Leach (1950, 1954a, 1961) dealing with the relationship of calendars, time reckoning, and various cultural categories. These studies help us to understand how time has been invented and constituted within particular cultural systems, given a logic based on certain principles and their relationship to the whole.

The integrity of the calendar as an intellectual system that provides a sort of unwritten score for social action has been challenged by Pierre Bourdieu as the "synoptic illusion" that separates ideas from practices. Arguing that "time derives its efficacy from the state of the structure of relations within which it comes into play" (Bourdieu 1977, 7), he proposes a "practice" theory focusing on the strategic importance of the tempo of transactions, not their place in an abstracted system of representation.

"Play" is stressed as a critical element because it implies that the flexibility and overt intentionality of people manipulating time can be calculated. An apparently unidimensional, linear time thus becomes a tool that both creates and symbolizes social relationships by the strategic manipulation of intervals. Holding back on an action, putting off a payment, and maintaining suspense and expectation are all analyzed as tactics for temporal gamesmanship. Through a series of loosely choreographed or stylized improvisations, time and its ambiguities are manipulated by individual agents with particular goals. Other versions of practice theory may stress the unintended consequences of action (Ortner 1984, 1989) or the multiple overlapping contexts of relevance for differently constituted temporal orders (Giddens 1984).

To "historicize" is to locate a phenomenon in time and see how this temporal location can relativize our appreciation of its significance. The "historicist" offers one resolution for the conflict between "totalizing" theorists and "practice" theorists, in that each approach is best seen as limited by its own temporal assumptions. Put briefly and rather schematically, the totalizing theorists focus on long-term processes and their outcomes. Classificatory systems produce "order" only by means of a retrospective glance. Things "fall into place" in terms of a wider logic as they are reinterpreted by actors and given meanings that relate to other parts of the system. This does not, in my view, make classifications invalid or mean that classificatory orders have no reality in the minds of acting subjects. But it does give them a particular position within indigenous systems of knowledge. Often the prerogative of some cultural interpreters in privileged positions, the perspective of the guardian of the calendar or a ritual authority charged with ensuring consensus is quite different from that of other members of the society.

Practice theorists, by contrast, focus on the negotiation of meaning in short-term processes, where actors procure symbolic as well as material capital (Bourdieu 1977). Many of the assumptions of practice theory are correct within this limited time span, but when such notions are extended over longer periods they tend to flatten out notions of cultural difference and reduce complex liturgical cycles to "practical maneuvers." Such analysis does an injustice to the complexity and intellectual sophistication of other peoples, who do attempt to "totalize" their social relations in various contexts but do not always agree on a method for doing so.

Practice theorists are right to argue that values are disputed and societies may be organized according to various interacting principles. But the new attention to actors and agency becomes meaningful only in relation to larger structures of temporal sequences and stages defined over the longue

durée . In a society like Kodi, the strategies of individual persons are worthy of our attention, but so is the process by which these strategies may eventually be encompassed into the larger temporal frame of the social life of the house, the heirloom, the garden site, and the village.

The "person" and his or her life span represent but a single moment in the complex historical development of institutionalized sequences such as the calendar, the ritual cycle, or the narrativized "past." Although each life requires its own accounting and each ritual event can have its own temporal dynamics, they must be juxtaposed to the wider cultural context in which they occur. Despite the technical difficulties of studying historical change in a society with few historical records, time must be seen as a crucial (perhaps the crucial) dimension of analysis.

Classification can be historicized, studied not as a final "moment" in which holistic integration is achieved but as a continous process of sorting out events and reordering them according to cultural values. An understanding of temporal configurations requires a movement between "person" and "process," between "events" that are inflected by actors' strategies, on the one hand, and retrospective interpretations that reabsorb them into longer-term sequences, on the other.

The historicist perspective adopted here borrows heavily from Mikhail Bakhtin's "historical poetics" (1981, 1984a, 1984b), Paul Ricoeur's treatment of time and narrative (1988), and a philosophical position that goes back to Wilhelm Dilthey but has recently reemerged in contemporary debates (Biersack 1991; Ohnuki-Tierney 1990; Veeser 1989). It begins with the idea that although there can be a multiplicity of perspectives on the past, these perspectives—constituted through a retrospective glance—are vitally involved in shaping actions and motivations in the present. Cultural perceptions are not based on fixed essences or orders but on understandings that are produced over time. The critical evaluation of the importance of the past, thus, is not a recent development, the product of literacy, capitalism, or the emerging world system. "Historical consciousness" has been with us for centuries but has taken many different forms in different societies, often interacting in dialogue.

Thirty years ago Evans-Pritchard (1961, 178) wondered, "Why among some peoples are historical traditions rich and among others poor?" He has been answered by arguments about hierarchy and political centralization, which assert that there is "more history in the center" (Fox 1971) and that the amount of "the past in the present" is related to the coercive authority structures of domination and inequality (Bloch 1977). But if "historical traditions" are defined broadly, as an omnipresence of the past and its signs, coded not only in narrative but also in objects, places, and

actions, then "the past" makes itself felt in complex ways, offering precedents for innovation as well as reproducing earlier states (Valeri 1990). Recent attention to different genres of historical representation has shown that the otherness of earlier experience can include the coexistence of antagonistic pasts that are themselves subject to a shared narrative framework (Appadurai 1981, 202) and provide the wellsprings of social change (Peel 1984, 127).

This case study of a single Eastern Indonesian people examines their complex relations to outside forces and how these have been involved in the construction of a cultural notion of the past. It then turns to the interplay of sequences and strategies in exchange and the transformation of local notions in dialogue with an externally introduced "history." The key questions asked are: Is there a hierarchy of temporal notions, so that one, for instance the calendar, is preeminent over others? Can this hierarchy change over the course of events, and can we chart the changes in other perceptions of time duration, process, cumulative effects? How are the political consequences of everyday negotiations of time—in exchange transactions, offerings to ancestors, and decisions about the timing of ritual performances—related to wider conceptions that make them meaningful?

The study questions the notion of historical representation and in particular the assumption that narrative representations are always in some way primary over other forms. In Kodi, I argue, the most significant forms for representing the past are often objects (exchange valuables or part of the "inalienable wealth" of a house) or actions (ritual sequences and procedures). Objects and sequences do not necessarily result in a "reification" or "objectification" of the past, but can also be part of a process of creative regeneration. "All relics of the past," as Greg Dening (1991, 359) has noted, "have a double quality. They are marked with the meanings of the occasions of their origins, and they are always translated into something else for the moments they survive." The social life of objects shows them to be deeply enmeshed in historical processes, in which they may move between the categories of "gifts" and "commodities," acquiring new meanings and values in the course of exchange. Local perspectives on the past use objects to mark the relationships between actors and events, giving a visual and tactile form to memories and historical configurations.

Temporal categories provide both ways of thinking and ways of acting. In order to sort out Kodinese perspectives on their own society and its transformations, I distinguish between "time" (as the culturally encoded experience of duration), "the past" (as a retrospectively constructed view of what has happened), and "history" (as a specific technique and inter-

pretation of how past and present are represented). Each of these is investigated and described independently in the pages that follow, and at the end I try to assess how they may be related. I argue that in the past, the indigenous ritual calendar was the key sequence that structured much of social life. In the absence of a centralized polity, the control of time was the main hierarchical function of the "Priest of the Year" and the focus of a sense of cultural unity—however diffuse and contested that unity often was. In the postcolonial period, the calendar has been increasingly displaced by the structures of the Christian church, the Indonesian state, and the wider ideological forces now identified with an ideal of national progress. Kodi has not been so "sheltered" from world events that these forces were not felt in the past, but in the thirty years since independence their influence has become dramatically more powerful.

The earlier classification of time and ritual order remains a "voice" within Kodi society, and it is not entirely a voice of the past because efforts are being made to preserve many of its features in transformed form. This study asks the reader to pay attention to the way past and present can speak to each other in a single cultural context and can inflect a certain "historical consciousness," which, while it may not be our own, is worthy of consideration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe a debt of gratitude to the many people who helped me to write this book. Two years of doctoral research in 1979-1981 were supported by the Fulbright Commission, the Social Science Research Council, and the National Science Foundation, under the auspices of the Indonesian Academy of Sciences (LIPI) and Universitas Nusa Cendana, Kupang. Six months of additional fieldwork in 1984 and a three-month trip in 1985 were funded by the Anthropology Department of the Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. In 1986 I returned to Kodi for three months with Laura Whitney to study ritual communication, using film and video, supported by the Faculty Research and Innovation Fund of the University of Southern California. In 1988 we continued this research project for six months with funding from NSF Grant No. BMS 8704498 and the Fulbright Consortium for Collaborative Research Abroad.

My first rethinking of the Kodi material after writing the dissertation took place in 1984-1985 at the Anthropology Department of the Research School of Pacific Studies, headed by Roger Keesing and James J. Fox, where I was fortunate to have been a member of the research group on gender, power, and production, led by Marilyn Strathern. The book was written in 1990-1991, when I was a member of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, and part of an interdisciplinary group focusing on the historical turn in the social sciences. I am particularly grateful to Clifford Geertz for offering me the opportunity to complete the manuscript and live with my family under such pleasant conditions. After I submitted the book, my husband and I were invited by Signe Howell to come as guest researchers in 1992 to the Institute for Social Anthropology at the Uni-

versity of Oslo, where we enjoyed generous hospitality and a chance to discuss our work with many new colleagues. People at each of these institutions provided both intellectual stimulation and friendship which helped me while finishing this work.

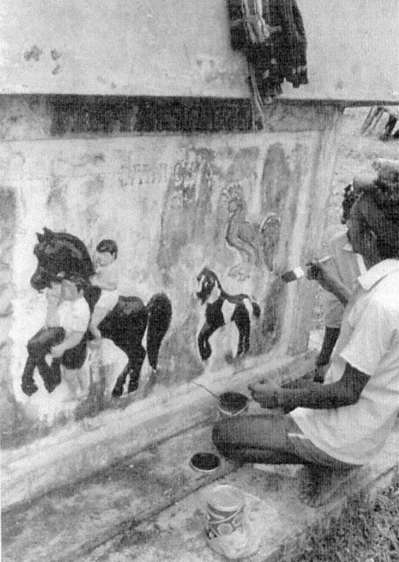

The final compilation of the manuscript was done at my home institution, the University of Southern California, with the gracious assistance of Debbie Williams and Mae Horie. The Center for Visual Anthropology, and the film-making example set by Tim and Patsy Asch, encouraged me to use forms of visual documentation as well as the more conventional notebook and tape-recorder, and inspired me to work with Laura Whitney to produce and write two 25-minute films on Sumbanese ritual, Feast in Dream Village and Horses of Life and Death (distributed by the University of California Extension Media Center, Berkeley). Other faculty and students at USC provided a congenial working environment and generous leaves to return to Indonesia and write up the results.

Many people read portions of this manuscript and offered valuable comments, only some of which I have been able to incorporate. I am especially indebted to Marie Jeanne Adams, Greg Acciaioli, Ann Geissman Canright, Lene Crosby, James Fernandez, Gregory Forth, James J. Fox, Rita Kipp, Joel Kuipers, Signe Howell, J. Stephen Lansing, Sheila Levine, Nancy Lutkehaus, David Maybury-Lewis, Stanley Tambiah, Laura Whitney, and three anonymous readers from the University of California Press. My most exacting critic has always been Valerio Valeri, who has however tempered his intellectual demands with gifts of love, companionship and caring. He accompanied me on return trips to Sumba in 1986 and 1988, and his thinking has influenced my own in countless ways over eight years of shared living and writing.

In Kodi, I enjoyed the hospitality of four different families: Hermanus Rangga Horo in Bondokodi, Gheru Wallu in Kory, Maru Daku (Martinus Mahemba Ana Ote) in Balaghar, and Markos Rangga Ede in Bukambero. My "teachers" in traditional lore are described in the first chapter, but I owe a great debt to all the Kodi people who took me into their homes and spent hours discussing their language and customs with me.

My parents, Herbert and Katharine Hoskins, taught me to love literature and oral narrative in many different cultural guises and have given me great encouragement and practical help. My sisters, Susan Hoskins and Judy Robinson, both visited me in the field, and Susan came a second time to take sound and edit the film project in 1988. I dedicate this book to my family, for all the emotional support they have given over the years, including its newest additions, my daughters Sylvana and Artemisia Valeri.

NOTE ON TRANSCRIPTION

This book presents the first extended series of texts transcribed in the Kodi language of West Sumba. The transcription system used is an adaptation of one already in use on the island and taught by elementary school teachers to their students. When I first arrived on Sumba in 1979, I was told by literate Kodi speakers that, although no Westerner had ever managed to learn to speak their language, they knew quite well how to write it with "Indonesian" letters, but that Kodi, like English, is a language that is not always written the way it is pronounced.

The first transcription system devised for all the Sumbanese languages came from the Dutch linguist Louis Onvlee, who worked with local assistants to translate the New Testament into the Kambera and Weyewa languages and published general descriptions of the linguistic diversity of the island (Onvlee 1929, 1973). As his system was also used by my informants, I follow it for the transcription of most words, as well as for the convention that many sounds are written with combinations of Latin characters. Consistent with modern Indonesian spelling, the sounds that were written in an older Dutch Malay as /tj/ and /j/ are here /c/ and /y/.

Kodi has three nasal consonants: /m/ a bilabial nasal, /n/ an alveolar nasal, and /ng/ a velar nasal. There are nine stops: /mb/ a prenasalized bilabial voiced stop, /b/ a preglottalized, implosive bilabial voiced stop, /p/ a bilabial voiceless stop, /nd/ a prenasalized voiced alveolar stop, /d/ a preglottalized, implosive voiced alveopalatal stop, /t/ a voiceless alveolar stop, /ngg/ a prenasalized voiced velar stop, and /'/ a glottal stop. There is also /gh/ a voiced velar fricative, the semiconsonants /w/ labiodental voiced and /y/ palatal, and the laterals /l/ apico-alveolar and /r/ alveolar,

with two affricates: /c/ a voiceless alveopalatal, and /nj/ a prenasalized voiced palatal affricate.

There are five vowels /i,e,u,o,a/ and four diphthongs /au,ai,ou,ei/ pronounced approximately the same as in other Sumbanese languages (Onvlee 1929, 1973, Kuipers 1990, Geirnaert Martin 1992).

Kodi is a highly inflected language, and sounds are often affected by the phonetic environment in which they are found; this is why informants claimed it could not be pronounced as written. But through a special use of certain letters it is possible to reflect the spoken language more closely. I use /y/ to indicate an extra syllable inserted after a consonant which follows the /ei/ sound in a preceding word. The /y/ sound is also inserted after the first consonant of a proper name to indicate that reference is in the third person (somewhat akin to the Indonesian practice of referring to an absent person as "Si Someone"). The insertion of this syllable changes the consonant /t/ to /c/ and the consonant /nd/ to /nj/ and may affect the way other parts of the word are pronounced. Thus, the prominent ancestor called Temba is referred to as Cyemba in Kodi, but if he is called with his title Rato the original form of the name returns, as in Rato Temba. A man who is called by his horse name is addressed as /ndara/ but referred to as /njara/. Kodi speakers do not modify the way they pronounce proper names when discussing absent persons in Indonesian, so I use the modified spelling of inflected names only in Kodi texts. These phonetic traits may explain some apparent inconsistencies in the transcription of proper names.

The book contains texts both in vernacular speech and in the special register of ritual speech which the Kodi call panggecango or "speech which is sewn up into couplets" (Hoskins 1988b). To reflect the marked social status of this indigenous verse form—the "words of the ancestors," which are believed to be relatively fixed and unchanging—I have arranged the paired lines to show their form as verse, and wherever possible I have included the precise Kodi text. These are considered words which have been passed down from past generations, and they represent a prized cultural heritage. I hope that these ways of representing the Kodi language on the page will be recognizable to my Kodi informants, who corrected many pages of transcribed texts so that their words could "travel over the oceans and reach people on the other side."

INTRODUCTION

THE LAND AND PEOPLE OF KODI

When I first arrived on Sumba in 1979, strapped onto a wooden bench as the only passenger of a tiny Twin Otter plane, it seemed an island out of time. Leaving behind the crowded, involuted civilizations of Java and Bali and their desperate struggle with the crises of modernization and development, I landed on a strip of asphalt laid out on an otherwise empty; grassy plateau called Tambolaka. With no human being in sight, the plane's arrival was of interest only to a lazy herd of grazing horses and buffalo who looked up from a desolate landscape of rolling hills and sharp gullies, a few thatched, high-towered bamboo houses just visible at the horizon. Two outbound passengers arrived mounted on small lively horses, their heads wrapped in red headcloths and their bodies draped with indigo loincloths and mantles. These were members of an important Kodi family, the people I had come to study for the next two years. They did not speak to me, but silently loaded their baggage, which included a screaming pig and a bundle of fine textiles, into the plane and left a small offering of betel on the runway. Other family members walked up to retrieve the two horses and erected a small post, on which chicken feathers had been tied, to show that sacrifices had been made at home to secure the blessings of the ancestors for this voyage overseas to seek medical treatment. As the plane taxied around and prepared to fly back to Bali, I had the brief sensation that I was about to be marooned in an another era, where horsemen with feathered headdresses herded buffalo and fought tribal wars with little or no awareness of the world beyond them.

Particularly disconcerting was the fact that my presence provoked no surprise or gawking stares—though the arrival of strange white women

was hardly routine; instead the others simply turned away, avoiding contact, which made me feel all the more invisible and out of place. Two years later, when I met members of the same family I had seen on the runway that first day, I asked them what they had thought at the time. "Oh, we didn't know then that you come to Kodi to study our language, to live with us and take a Kodi name. All we could see then was a foreign lady who came from a land where the sun set into the tides and the moon rose on shifting sands. We thought our hands would never join, and our feet would never meet."

An anachronism is usually defined as something that remains or appears after its own time. What I felt in these first few minutes most vividly was not that I was confronted with an anachronism, that these people represented some archaic or obsolete way of life, but that I myself had come unstuck from any familiar temporal framework and was quite simply misplaced in time. Sumba seemed not a survivor from the past, but an area that was profoundly out of sync with the modern world, moving to its own rhythms and unbothered by much distant turmoil. What the people on the runway felt, in contrast, was that a Westerner could have little interest in them and would not want to become a part of the very different temporal framework of their lives. The meeting that they thought inconceivable seemed unlikely because of the long historical and geographical isolation of their island.

Retrospectively, it is easy to see that this first impression, like so many others, was an illusion. Nevertheless, it opened the way to an intuition that I did not come to understand for another ten years. It showed me that I was confronting something very different, even alien, not so much in the people as in their temporality—their ideas of their own place in the world and how they moved through time. The idea that some people could exist separated from our own time worlds has long been part of the romantic appeal of isolated islands for travelers, adventurers, and, of course, anthropologists. While anthropologists have recently been criticized for constructing a great temporal distance between other worlds and our own (Fabian 1983; Thomas 1989), these experiences of temporal dissociation can also be heuristic. They can serve to awaken us to some of our own assumptions and unsettle the taken-for-granted relations among past, present, and future. As Fabian noted, "Experience of difference and otherness begins only when received time-space fusions begin to become undone" (1991, 199). That moment of confusion on the runway was to be the beginning of a long apprenticeship in the study of time.

"A Land Apart": Geography and Subsistence

The islands of the outer arc of the Lesser Sundas (map 1) do not have the great volcanoes and fertile tropical soils of Indonesia's main islands of Java, Sumatra, Bali, or Sulawesi. Largely comprising uplifted coral reefs, Sumba has low mountain ranges and a heavily weathered, rugged topography of limestone and other sedimentary rocks. It is a relatively large island of 11,500 km2 , 200 km long and from 36 to 75 km wide, dominated by wide grasslands. Southeast trade winds blowing off the Australian continent bring a hot dry climate to the eastern part of the island, which has virtually no rainfall for eight months of the year. Low, grass-covered hills appear stark and rather forbidding along the northern coast, broken only occasionally by dry gullies cutting their way toward the sea. As one moves inland and farther south, the rolling hills give way to a more rugged highland region of rocky inclines and forested mountains. None of these peaks reaches a great height, however: Mount Wanggameti in East Sumba is the island's highest point at only 1,225 meters.

Many areas are only sparsely populated; the island's four hundred thousand people are spread unevenly over the eastern and western halves of the island because of differential access to water. In the savanna grasslands of the east, population density averages only 18/km2 , whereas in the damper western half it rises to 50/km2 , with annual population growth standing at 2 percent (Helmi 1982). Rainfall differences range from a sparse thirty inches on the dry plains of the northeast, near Waingapu, to over a hundred at the wettest part of the island, Waimangura in the western highlands (Hoekstra 1948, 8). The physical contrast between the wet and dry areas seems greater than the difference in rainfall would indicate because much of the water that flows northward disappears underground, percolating into the porous limestone.

The Kodi district, to which I was headed, lies at the western tip of the island (map 2), perched at the "base of the land" (kere tana ); this area is seen by the Sumbanese as the lower half of a human body whose head lies in the east. Kodi is lush in the rainy season but dries out to a parched, dusty plain in the months from March to November. The region is not suitable for wet rice cultivation; indeed, it is ecologically closer to the eastern grasslands with their pattern of swidden cultivation of dry rice and extensive livestock grazing.

Rice and corn form the basis of Kodi subsistence. Both are planted in mixed gardens, along with beans, tubers, chilies, and vegetables. Rice is believed to have special life-giving, nutritional qualities, and hence it is the focus of collective life (it is the only proper food to serve to guests)

Map 1.

Eastern Indonesia: the Lesser Sunda Islands

Map 2.

Ethnolinguistic map of Sumba. Each area corresponds to a traditional

ceremonial domain.

and has primary importance in the ceremonial system; yet because only a single annual wet-season crop can be produced, actual eating patterns depend heavily on other inferior crops. Corn is less appreciated than rice, but it can be harvested twice a year, so it comes closer to being the true staple of most households. The absence of rice is culturally defined as "hunger" and the long period from October to January is called the "hungry season" since it comes after most rice supplies from the previous year have been exhausted. A small share of rice is always set aside for calendrical festivities in late February or early March; this meal may represent the last time rice is eaten before the new harvest in April.

The fifty thousand Kodi people live widely dispersed in garden hamlets scattered through three different river valleys (Kodi Bokol, or "Greater Kodi"; Bangedo; and Balaghar). Despite its many problems, the Kodi coast

presents a picture of fertility and abundance during much of the year. The main road that runs the eighty kilometers from the regency capital of Waikabubak is lined with banana and mango trees, and as it approaches the coast the view opens up to take in the sea and plantations of coconut and areca. The low-roofed thatch houses in garden hamlets are in fact only temporary dwellings, for the people's more permanent attachments are to the sixty-five ancestral villages that line the coast (map 3).

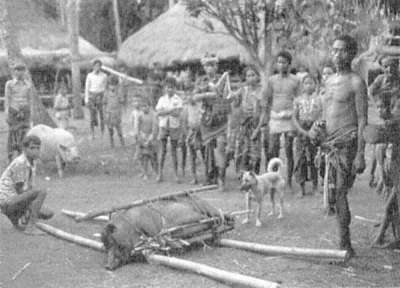

Land is used in three different ways in Kodi: as gardens (mango ), as fallow plots (rama ), and as pastures for livestock (marada ). Traditional methods of shifting cultivation have become less effective now that so much land has been brought under cultivation, and the Kodi are well aware of the diminished fertility of their fields. Pastoralism—raising herds of buffalo, horses, and cattle—has long been the center of the Kodi prestige economy, but it is becoming more important to subsistence as well. Grass-land farming is still possible, but it requires extensive time and effort. The coarse, tall tufts of swordgrass are burned off in the dry season, to expose new tender green shoots that can be grazed by herds of horses and buffalo. The ground must then be broken up, turned, and allowed to dry for six weeks to remove plant residues. It is worked again, the soil being chopped into smaller chunks and dried for a second burning. Such methods are similar to those used in grassland areas of Sumatra (Sherman 1990) and highland Burma (Leach 1954b), which share the high cultural valuation placed on rice but also suffer from severe ecological constraints.

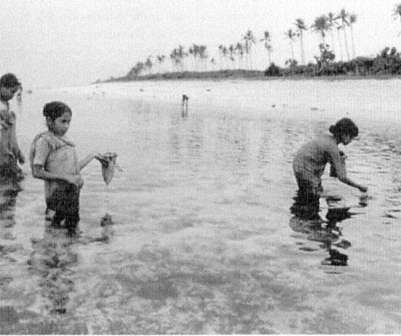

Because of climatic variation and the uncertainty of agricultural production, relations between the interior and the coastal regions have long been based on a system of internal trade known as mandara (literally, to ride on a horse in search of food). Toward the end of the dry season, people from Kodi and other seaside districts travel inland to find vegetables, tubers, and other early-ripening foods to sustain them through the hunger months. These crops are exchanged for salt, dried fish, lime, pigs or livestock, and cloth. Gifts of cloth—a product largely of the coastal regions, where indigo plants grow in profusion—are particularly important, since textiles are required for all traditional exchanges. Although commercial dyes have largely replaced natural ones in textile production in many areas of the interior, making the Kodi monopoly on indigo less important, natural dyes are still required for the finest ritual cloths. In this domain, several older Kodi women maintain their preeminence as specialists in the secret art of dye-making (Hoskins 1989c).

In years of serious drought or famine, the line between the subsistence sphere and the prestige sphere of livestock raising becomes blurred, and then not only textiles but even horses or buffalo are exchanged for food.

KODI BOKOL | |||

Kabihu Pola Kodi ("the trunk of Kodi") | |||

1. Bukubani | 9. Wei Ratu Rambi | 17. Ndelo | |

2. Wei Karoko | 10. Wei Hyati Wyora | 18. Watu Pakadu | |

3. Nggalu Watu | 11. Pakare | 19. Tossi | |

4. Lawudi | 12. Kere Homba | 20. Kalirnbu Atur | |

5. Ramba Lodo | 13. Mabaha | 21. Mboro Mbake | |

6. Wei Yengo | 14. Bahewa | 22. Wondo | |

7. Linngyaro | 15. Bondo Gole | ||

8. Hambali Atur | 16. Mete | ||

Kabihu Mbali Hangali ("the other side of the embankment") | |||

23. Wei Kadoki | 29. Ngi Pyandak | 35. Pou Dawa | |

24. Bondo Maliti | 30. Kere Tana | 36. Bondo Kamodo | |

25. Bondo Kawango | 31. Toda | 37. Bondo Kodi | |

26. Malere | 32. Menakaho | 38. Rambi | |

27. Malandi | 33. Lewata | ||

28. Wei Kahumbu | 34. Bongu | ||

KODI BANGEDO | |||

Kabihu Mahemba | |||

39. Hali Kandangar | 41. Balengger | 43. Manu Longge | |

40. Waindimu | 42. Parona Baroro | 44. Kabota | |

Kabihu Pawungo | |||

45. Mehang Mata | 49. Homba Wawi | 53. Hangga Koki | |

46. Pakare | 50. Watu Lade | 54. Ratenggaro | |

47. Rangga Baki | 51. Ngahu Watu | ||

48. Nggalu | 52. Bondo Tamiyo | ||

KODI BALAGHAR | |||

55. Weingyali | 59. Maghamba | 63. Baroro | |

56. Wei Hyombo | 60, Weinjolo Wawa | 64. Kaha Malagho | |

57. Weinjolo Deta | 61. Wei Katari | 65. Kaha Katoda | |

58. Mahendak | 62. Weinjoko | 66. Kaha Deta | |

Map 3.

The location of traditional territories (kabihu) and ancestral villages in Kodi

In 1977, locusts destroyed a large number of gardens, and 1982 saw a plague of mice and the spread of new crop disease. In Kodi terms, such disasters are disruptions of seasonal temporality ("the months of hunger are not the only hungry ones; the months of plenty are also lean"), upsetting an already precarious balance of ecological factors and human activity; they require the ritual mediation of traditional timekeepers to set them right.

The Long Conversation: Fieldwork Conditions and the Study of Time

I did not come to Sumba to study the perception and organization of time. My dissertation proposal, formulated after reading what few materials on Kodi had been published by missionaries and visitors, focused on the relation of mythology and social organization.[1] Rather, I was only slowly initiated into the topic over the course of seven different periods of ethnographic research that spanned more than a decade (1979-89). I did, though, come with an interest in the cultural construction of the past, and particularly in the narrative definition of precedent, which ethnographic studies had indicated would be expressed in elaborate genealogies in parallel verse (Adams 1969, 1970; Fox 1971).

This past itself was more alive and influential than I had expected, because in the early 1980s the traditional religion of marapu worship was still practiced by three-quarters of the population. Spirits of the dead were invited to all important ritual events and fed sacrifices, as well as regularly blamed for inflicting misfortune on their descendants when promises or obligations were not fulfilled. Precedence was invoked as an ordering principle but continually contested and renegotiated. Genealogies were short and alliances unpredictable; hence, the unity of the Kodi people took shape mainly through adherence to the yearly calendar. In sharp contrast to the stratified societies of East Sumba, the Kodi people had no royal

[1] When I arrived on Sumba in 1979, the only ethnographic materials concerning the island available in the United States were the collected essays of the missionary-linguist Louis Onvlee (1973), a series of articles by art historian Marie Jeanne Adams (1969, 1970, 1971a, 1971b, 1974, 1979), and some older missionary writings (Kruyt 1921, 1922; Wielenga 1911-12, 1916-18). Kodi was described in a fascinating but brief article by Van Wouden ([1956] 1977), and some Kodi fables had been published by Needham (1957b). Since that time, however, there has been an explosion of interest and research, including the essays in Fox 1980d and new ethnographic studies by G. Forth (1981), Kuipers (1990), Renard-Clamagirand (1988, 1989), Geirnaert Martin (1987, 1989, 1992), Keller (1988), I. Mitchell (1981), and Keane (1990).

genealogy that ordered collective memory or produced a single master narrative of regional history. Over the next ten years, subsequent field trips led me to question whether the period they called la mandei lama ulu ("the past") was one thing or many different things.

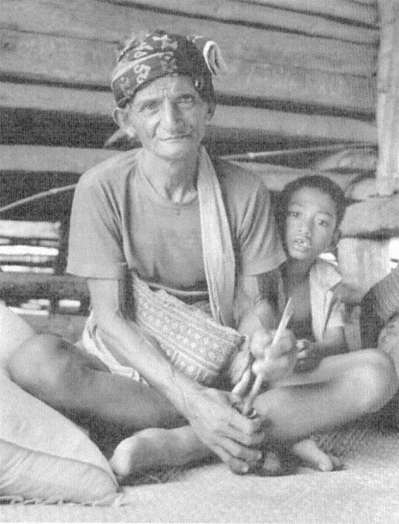

Despite their initial standoffishness, Kodi people proved remarkably open and hospitable once they heard that I had come to study their language and culture. In Java, I had met a Kodi student who arranged for me to spend the first three months of my stay with his aunt, Gheru Wallu, in the market center at Kory in Greater Kodi. A rigorously traditional woman who spoke almost none of the national language, she was also a skilled herbalist, masseuse, and midwife. As my skills in the language gradually improved, I shifted to a new location closer to the ancestral villages along the coast—ritual centers and site of the calendrical festivities. I moved into a small house in Bondo Kodi that had been built for a nurse and set up my own home, living with two local girls, Maria Rihi and Fenina Manu, who helped with cooking and washing. Finally, toward the end of my stay, I spent two months in the distant river valley of Balaghar as the guest of my teacher Maru Daku.

During most of my fieldwork, men served as my "teachers" while women were my "companions." The important men who consented to become my instructors and guides in the arcane world of ancestral custom called me their "student" and "daughter." The women who lived with me in three separate households and helped me with the practical matters of life called me "sister" and "friend." Because of the way my gender and relative youth were culturally construed, my relations with men were cordial but hierarchical. They knew I wanted to collect and compile socially valued forms of knowledge, and they respected my work because I also respected them. Women, however, usually excluded from competitive claims to possess such knowledge, teased me about my earnestness; it was they who gave me the Kodi name by which I am still known there: Tari Mbuku, the name of a female ancestor but also, interpreted in Indonesian, having the double meaning of "looking for a book."

When I first began "looking for a book" I expected it would be an analysis of genealogies and traditional narratives in relation to the system of kinship and alliance. The material's I finally brought together for my dissertation, however, focused on the feasting system and its basis in spirit worship (Hoskins 1984). In turn, feasting was an arena for achieving renown and playing out the politics of exchange, which, I came increasingly to realize, was connected to a very different form of temporality.

The puzzles that eventually became the subject of the present study emerged in conversations with four Kodi "teachers" each of them a "man

of knowledge" who controlled a different aspect of local temporality. The first "knew stories," the second "knew history" the third "knew how to sing the words of ritual" and the fourth "held the rites of the year."

Maru Daku, a famous bard and respected elder, was unrivaled in his mastery of Kodi verbal lore ("The book of our customs lies underneath his skin," a friend once said of him), and he was a figure of great authority, if a controversial one. Maru Daku's command of traditional narratives held his listeners in thrall, even when they disapproved of many aspects of his own life. An early convert to Christianity, he eventually repudiated the church leadership and returned to marapu worship. His great inventiveness with words was both praised and suspected and (as happens so often in Kodi life) won him an audience but not always followers.

Hermanus Rangga Horo, my second teacher, had been not only the last Dutch-appointed raja of Kodi but also the head of island government for a period after independence. He believed strongly in scholarship and recordkeeping; indeed, the personal notes and journals he kept over the eighty-seven years of his life were the only surviving local archive. I draw on them, and on his own vivid memory of past events, frequently in these pages, as well as on many discussions of custom and local litigation, the problems of governing a remote island only now "breaking into history," and the transformations that had occurred since independence.

My third teacher, Markos Rangga Ede, was a priest and singer who carried out marapu rites in his homeland of Bukambero and throughout the district of Kodi. Boasting a baritone so forceful it could "tear apart houses" with its tones, he was a traditionalist leader who served at times during my stay as the ward clerk and ward headman of Bukambero; he was always a strong local personality. For eight years I have followed him to rituals, recorded his songs and the dialogue of orators and diviners, then spent days going over the material with him to understand it in all its complexities.

The highest-ranking priest in Kodi was a "Father Time" figure, the Rato Nale, or "Lord of the Year." In Tossi, the ritual center of the domain, this office was held by Ra Holo, a patient and considerate host to me on my many visits. His own modesty and self-effacing demeanor contrasted strongly with the heavy obligations of his task; as the embattled nature of his position grew ever clearer to me, I came better to understand why he seemed reticent and taciturn on particular occasions. His counterpart in the outlying village of Bukubani, Ra Ndengi, agreed to narrate certain myths and allow me to observe the ceremonies of the new year; he was not, however, as reflective and questioning of his own task as Ra Holo.

Death interrupted the long conversations I began, taking away many

of the strongest voices in my fieldwork. Maria Rihi, my "younger sister" and companion in my first home, was tragically killed in an accident at the end of my first year of research. A year later, Maru Daku fell seriously ill and recited a touching last testament to family and friends in my living room (Hoskins 1985). He later recovered and was able to bid me farewell, but I received news of his death as I was preparing my dissertation. His nephew, Ndara Katupu, who helped to compile and transcribe his words, died some months later. My host for return visits in 1984 and 1985, H. R. Horo, died before we returned on a film project in 1986 and 1988. And a graduate student from the Australian National University, Taro Goh, who attended the funeral I describe in chapter 9, died in the hospital of East Sumba six months after beginning his own field research on the island. The loss of these people, sudden and unpredictable because many were so young, haunted me during my writing and analysis, and no doubt contributed to the focus of this work on temporal notions as a response to human mortality.

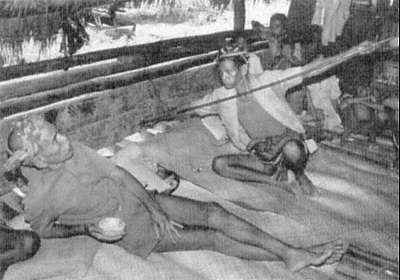

The "sitting work" of transcribing texts, analyzing them, and interpreting them always took much more time than the "walking work" of traveling to distant villages and attending rituals.[2] It was while sitting with women, chewing betel, stringing cotton thread onto a loom, and untangling recently dyed yarns that I first stumbled on the idea that different temporalities could be the key to understanding much of the ceremonial system and its transformations. The shrewd and often sarcastic commentaries of women who watched from the darkened hearths at the center of Kodi houses encouraged me to look more closely at the ordering of events and lives in time. Their narratives also alerted me to the special significance of objects, because whenever I asked a woman for the story of "her life" I was given instead the story of an object, an exchange valuable, or a domestic animal. Whereas men narrated accounts of how they became the owners and exchangers of wealth, women confided indirectly, telling stories of possessions that had been tied to their own identities and then been taken away.

Because this study examines the public, shared world of the calendar and the annual cycle, it only touches on the more private world of domestic objects, persons, and gendered selves. The wider temporal perspective of the calendar, the exchange cycle, and the encounter with history is not an exclusively male one, but it does give important men a greater voice than

[2] Among those who worked with me on the transcription and evaluation of a number of texts, I would like to thank A. W. Bulu, Gregorius Gheda Kaka, Lota Mahemba, Yusup Ndara Katupu, Gideon Katupu, Ndengi Yingo, Radu Yingo, Rehi Pyati, Andreas Ra Mone, and Deta Raya.

their wives or daughters. The more hidden world of household politics and personal memory deserves separate treatment (Hoskins 1987b, 1988c, 1989c, in press). The conversations I had with men centered on time as an encompassing system of order; in those with women it was presented more as a dimension of biographical experience. Eventually, I hope to write about both perspectives.

The Play of Time in Anthropological Writing

Moving from the here-and-now reality of fieldwork to writing about those experiences in an ethnographic monograph creates a discrepancy between personal memory and an analytic account. The mixture of empathy, nostalgia, and guilt that I felt after my departure from the field was processed into descriptions which took various forms—a dissertation, articles, films, and drafts of the present manuscript. I returned to Kodi six times, bringing some of these materials for my former teachers to look over, but few were really interested in the theoretical questions that I address here. Our sharing of the same historic time and space during fieldwork—what Fabian (1983) calls "coevalness"—was replaced by a temporal and spatial distance which made the final writing a retrospective exercise that was mine alone.

The problem of "primitive temporality" that I explore in this study has not generally been linked to the concerns of history, anthropology's own politicized context, or the world economic system. Several recent writers have even questioned whether the argument that other peoples live in different time-worlds amounts to a "denial of coevalness"—an exclusion of them from our own temporal framework and an assertion that they live outside of history (Fabian 1983; Marcus and Fischer 1986; Clifford and Marcus 1986). In my view, this need not be the case; but to free ourselves from such false assumptions we must first get rid of the adjective primitive . As Fabian (1983, 18) says, "Primitive , being essentially a temporal concept, is a category, not an object of Western thought."

This work is about a specific historical and social system of timekeeping—Kodi temporality. This system is not treated as a subtype of "the primitive"; rather, the conceptual distance between Kodi time concepts and our own is the focus of analysis, not only so that we may delineate differences between "us" and "them" but also to problematize our own concepts, showing them to be neither necessary nor universal. Although the highly contested nature of the past has been the subject of much debate among Western historians, few ethnographic studies address it directly.

To restore the topic of indigenous temporality to responsible examination, I have tried to avoid certain traps in ethnographic writing which

recent writers have called to our attention (Fabian 1983, 1991; Sanjek 1991; Thomas 1989). There is, for example, no "ethnographic present" in this book. Descriptions of Kodi life are drawn from historically situated events and persons, who bear their real names, as my Kodi informants requested. The sense of personal engagement and shared experience that I had in the field is revealed through use of the first person in situations where my own involvement was important. This book is not, however, a work of "reflexive anthropology" in the sense that it takes as its primary subject the encounter between the anthropologist and her hosts. My initial feelings of confusion about time are relevant to this theme, but to dwell excessively on each mistake and misunderstanding along my path would be self-indulgent and ultimately solipsistic. Fieldwork is a time when most of us become painfully aware that we are neither objective nor omniscient. In writing about the experience, therefore, I concentrate on how I was ultimately able to make sense of some of these initially alien concepts.

Notions of time are notoriously slippery and hard to grasp. In describing the Western ideas I brought along as part of my own conceptual baggage, I must speak in metaphors. We say, and believe we understand what we mean, that "time is money" and "history moves forward in a linear progression." The people of Kodi say, and tried to explain to me what they meant, that "time is value" and "the presents turns to the past" to seek models for innovation and change. Both of us, in dialogue, often have trouble understanding what lurks beneath the metaphors; we require the context of lived experience to clarify such apparently abstract distinctions. This book tries to provide that context, describing how the past is represented in narrative, objects, and action, and how Kodi calendars and exchange transactions play out specific notions of time. The story must begin with the social groups and categories that I had first thought would be the subject of my study of Kodi. They start to tell us a story about a different way of moving through time-but they are only the beginning.

Social Units in Kodi Society

People locate themselves in time by means of the categories of the kinship system. In Kodi, these categories are preeminently those of ancestors, descendants, and affines. Kinship and alliance are constructed as temporal modes of connection. One mode of connection is established along the patriline, which defines locally resident groups and the worshippers who gather in each ancestral village. A second mode is established along the matriline, with people belonging to named but dispersed social groups somewhat vaguely connected to notions of shared substance, personality,

or attributes. Affinal relations constitute a third mode, coursing through the patricians and matriclans as the "flow of life" by which women are moved to new homes and bear children to continue the descent line into a new generation.

The House

The house (uma ) is the starting point of each individual's location in time. Born as a member of a house in an ancestral village, a man will remain attached to that house throughout his life, will make offerings to its ancestors and heirloom objects, and his bones will come to rest in the stone tombs that circle its central ritual plaza. A woman will, at some point, be transferred by marriage into another house and will come to worship the ancestral community of her husband, but she will retain strong ties to her natal house. Members of the "house of origins" (uma pa wali ) provide blessings of health, fertility, and well-being for her and her children, remaining obligated to continue friendly exchanges until the final gifts of death, when they finally take back the life they have given to the village by carrying the body of the out-marrying woman and her children to the grave.

The house is both a physical structure and a social group. The tall thatched towers of Kodi ancestral houses rest on a wide bamboo frame that slopes down to a raised floor of unbroken bamboo poles. Many houses are without walls but have inner partitions and platforms for the storage of heirloom objects, which hang from the peaked ceiling. The roof and floor of each house must be rebuilt every decade, and the obligation to "keep the house standing" is the most prominent ceremonial obligation shared by the "people of the house."

The house represents an unbroken line, extending vertically back in time, connecting the current inhabitants with their predecessors and successors. At the top of this line is the founding ancestor, named and propitiated on all ritual occasions, and below him are arranged all that has resulted from his life: his descendants, possessions, ritual offices, followers, and captives. The "masters of the house" (mori uma ) are those directly descended from this ancestor or else formally incorporated into the house by completing exchange payments (for wives or adopted children). The other "people in the house" (tou ela uma dalo ) are affiliated to the house through debt, capture, or default, and thus are not part of the house as a corporate unit but only "sheltered" by it. The term is usually used as a euphemism for slaves and dependents, who have no formal membership, cannot participate in house rituals, and must "sit at the edge of the veranda" (londo la hupu katonga ) when the ancestors are directly addressed.

Ancestral villages (parona ) are made up of a minimum of four ranked houses and usually contain between seven and thirty named house plots, each connected to a defined descent group (although fewer houses may actually stand in the village plaza, some of which may be in poor repair). A village name always refers to its location ("large hill" "rocky cliff," "edge of the land") or the tree planted in the center of the plaza, which serves as its altar ("leafy banyan," "wide-trunked kapok," "tamarind skull tree"). Direct descendants of the founder are called the "fruits and flowers, sprouts and shoots" (wu wallada, kahinye katulla ) that grew from this great trunk, the male descendants being the seed-bearing "fruit" (wuyo ), the females being the "flowers" (walla ) who go off to bloom in other villages. The female term is anterior but ephemeral; the male one provides continuity into the next generation.

The house built by the village founder stands at the head of the central plaza (kataku nataro ) and faces the next-ranking house at the "base" (kere nataro ), with the following two at the "right" and "left" wings (kapa lawana, kapa kaleiyo ). This division into four quadrants establishes an order of precedence followed in all sacrifices and offerings, as a share must always be given to the four "main houses" (bei uma ). All other houses originated as the "children" (ana uma ) of these four founders but may have developed other complex relations to each other in the division of ritual tasks. The houses are given individual names derived from their founder ("Byokokoro's House," "The Foreigner's House"), their ritual tasks ("The Drum House," "The Slaughtering House"), or idiosyncratic characteristics of their appearance ("High-roofed House," "House with Side Posts").

The ancestral village as a unit is exogamous, except for a few exceptionally large villages, which have split into two moieties that can now intermarry. Marriages are negotiated between members of different ancestral villages, and the exchange of bridewealth (livestock and gold from the groom's side, cloth and pigs from the bride's) should ideally involve all the members of a house. The house also owns land and heirlooms collectively and must meet as a corporate group to decide any shifts in its properties.

Houses are associated with genealogies; most persons can recite the names of several important ancestors, which situate them in one of the houses and indicate how they are descended from the founding ancestor. Kodi genealogies are not, however, limited to human forebears. The sacred litany that is repeated at each house ritual, the li marapu or "voices of the ancestors" is not only a list of personal names, but also a naming of sacred objects and sacred places important in the history of the house. The "time

line" thus extends the notion of "family history" to incorporate possessions and landmarks that, too, are seen as important predecessors in the shared past of the community.

Patrilines and Matrilines

Genealogical memory is relatively shallow, usually extending back no more than four or five generations. Even members of important families could not remember the names or relationships of people in their great-grandparents' time, although they might remember the name of certain important predecessors. The head priest of the calendar, the Rato Nale or "Lord of the Year" knew the genealogical links that bound him to previous holders of the office back to the beginning of the twentieth century, but not before. Descendants of the first two Dutch-appointed rajas could not produce the legitimating genealogical documents (silsilah ) that their colonial masters required. The last Kodi raja, H. R. Horo, hired my teacher Maru Daku to construct an account of his own family history to justify his right to hold office.

The few important elders or ritual specialists who had detailed knowledge of genealogies were often called in to resolve legal disputes centering on rights to land or heirloom valuables. Their task shows that in an important way time is measured through exchange transactions—the careers of objects—and not through the simple succession of generations. It also shows that the passage of "natural time" cannot be estimated from genealogical evidence alone. A counting of generational intervals is routinely used to measure the period of time that has passed in planning a feast or negotiating a new alliance, but since certain predecessors are often "forgotten" these accounts serve more to legitimate claims to a longstanding position than to estimate an actual time span.

Kodi stories about ancestors share the property noted by Paul Bohannan with regard to Tiv myths and legends in that they often do not distinguish between the founder of a lineage and his group of descendants. Bohannan (1967, 265-27) explained that "myths are told as explanation of social process, not as 'history.'... There are a relatively few stock incidents which can be applied to any instance of the social process to be illustrated." If we do not try to use genealogies to reconstruct a Western chronology but rather to gain insight into an indigenous one, we can make this "explanation of social process" the focus of analysis, probing the unfamiliar shape and constitution of the Kodi li marapu to garner clues about a different construction of time and history.

The house provides the location and the connection between the person and his or her ancestors, through the li marapu or time line that extends

back to the founding ancestor. The body, especially the blood, contains the substance that links the person to the matriline and a cross-cutting network of "relatives" (dughu ) who neither live together nor worship in the same house. The term for matriline, walla , means "flower" and refers to the "flowering" of a woman's descendants in many different directions. Each walla is a named, exogamous group, associated with personal characteristics such as a fondness or intolerance for particular foods, personality traits (brashness, trustworthiness, duplicity), and secret knowledge (the tricks of indigo dyeing, herbalism, love magic).

The walla bears the personal name of an ancestress (Loghe, Mbera, and so forth) or the region from which she came. Stories about the origin of matrilines are told in a tone of gossip and scandal, since they usually concern an infraction or violation of a taboo. Walla Gawi, for instance, is descended from a woman who copulated with a goat, Walla Mandaho from one who eloped with a swordfish. The name Walla Wei Kanikiwikyo ("the urine descent line") comes from an infant who urinated on her mother's lap, was severely beaten and finally cast off. Two walla are named after related shrubs, Ro Rappu and Cubbe ("potato leaves" and "potato shrub"), which influenced the fetuses of women who developed yearnings for them during their pregnancies. The most dangerous walla , Walla Kyula, bears the name of the black witchcraft bird, whose song is an omen of approaching death. Marriage with a woman from Walla Kyula is extremely hazardous, as she is believed to be able to assume the shape of wild animals, fly around at night to prey on the internal organs of her enemies, and suck vital energy from her own husband and children.

Because wallas carry many unsavory associations, a person's matriline is often kept secret, to be disclosed only in a giggling whisper behind the house. It provides a link to the past, but a shady past full of suspicion and doubt, not the glorious past celebrated in the li rnarapu . The question of walla affiliation surfaces most often in the context of marriage negotiations, where questions of the bride's rank, blood lines, and personal characteristics can become an issue. The rules of walla exogamy are much stricter than those of the patrilineal house or village. Because the walla is seen as based on a unity of blood, violations of the exogamy rule can provoke not only social sanctions but a rebellion in the body itself. If a woman should be given in marriage to a dughu , a member of the same walla , the very blood of her womb is said to "rise up in protest," producing high fevers and hemorrhaging. The reaction cannot be mediated in any way, and difficult childbirth, chronic illness, and even death could result.

The patrilineal house and village are socially created corporations united in the worship of a specific group of ancestors, objects, and places. Since

patrilineal groups have political, ritual, and jural authority, membership can be transferred by legal fictions and ritual mediation. It is possible, for example, to adopt a potential bride into a new house and village, if necessary, to allow two members of the same village to marry. The problem involves the direction of marriage payments, and thus the definition of social groups through exchange relations, rather than the primordial ties of blood. Violations of walla incest provoke supernatural sanctions that threaten the health of the offenders. Violations of incest prohibitions in the house or village can be resolved by the payment of kanale , a legal fine that is also used in cases of adultery or a broken engagement.

These contrasts reveal a marked difference in the way relationships through men and women order Kodi society. The patriline provides a vertical axis for Kodi social life in three senses: (1) it links people back through time by delimiting lines of descent that organize the transmission of ritual prerogatives through the generations; (2) it relates the human order to divinity and to ancestral origins, providing a cosmological justification for the contemporary division of land and powers; and (3) it dramatizes hierarchical relations in both human and spirit worlds at large-scale ceremonies and feasts. The matriline, in contrast, orders social life along a horizontal axis: (1) it links people of different patrilineal houses and villages across space because of membership in the same walla ; (2) it forms a personal network of matrilineally related people said to share a common substance (blood) but no ritual or corporate functions; and (3) relationships traced through women work against notions of rank and lineage opposition by providing a cross-cutting system of kin ties that are essentially egalitarian.

Alliance

Alliance links houses and villages and serves as a conduit for the transfer of women, animals, objects, and ritual prerogatives. It is a form of social cooperation and mutual assistance that not only is still hotly contested in Kodi social life, but has provoked a number of interesting contests in the scholarly world as well.

Marriage systems in Eastern Indonesia have long been the focus of research and analysis, ever since Van Wouden's famous characterization of them as "the pivot on which the activity of social groups turns" ([1935] 1968, 2). Early work concentrated on prescriptive asymmetric alliance, which was believed, in the famous "Leiden hypothesis" to be paired with double descent in the original proto-Austronesian form of dual organization. Kodi played an important role in the deconstruction of that original hypothesis. Reports of double descent, "in which both patrilineal and

matrilineal clans operate side by side in the organization of the tribe" ([1935] 1968, 163), suggested that the original system might have survived in its most "intact state" there.

Van Wouden himself did two months of fieldwork in the region in 1951. He found, to his chagrin, that the Kodinese differ from many other Sumbanese peoples in that marriage is not governed by a categorical prescription. Thus, a crucial argument in his original thesis had to be modified. His initial disappointment brought him to a more sophisticated formulation of the nature of variation in Eastern Indonesia, stressing the different directions that descent and alliance had taken in societies of the region. While he noted that opposing systems still shared a certain "structural coherence," their historical divergence had become a question "so complex and encompassing that it is doubtful it could ever be properly posed, let alone answered" (Van Wouden [1956] 1977, 219).

Van Wouden's article on Kodi remains an ethnographic classic, not only because it is the earliest description of the region, but also because it signaled an early "opening up" of Dutch structuralism. The goal of comparative research was no longer the working out of a single model (a goal supposedly anterior to the great diversity of present practices), but the understanding of relationships and systemic change along a number of dimensions (Fox 1980a, 6). Recent fieldworkers who have studied asymmetric systems have shown how alliance is essential to the constitution and definition of social groups (G. Forth 1981; Lewis 1988; Traube 1986; Valeri 1980; McKinnon 1991) and the structure of descent is a product of the pattern of marriage.

Although sharing a clear kinship with these societies, Kodi alliance is still "looser" and less consistently articulated than other social institutions. In Lévi-Strauss's terms (1969a), Kodi marriage forms a "complex" system, not an "elementary" one, and it has become increasingly clear that the same is probably true of the majority of Eastern Indonesian societies (Fox 1980b, 329-30). Since alliance is not directed by a categorical prescription, it is endlessly negotiated on the shifting terrain of intergroup relations. Rather than being frozen into an authoritative and enduring "totalizing system," it becomes the focus of local politics and the marker of individual achievement.

The relation of wife-giver and wife-taker in Kodi is asymmetric. The direct exchange of sisters (pandelu lawinye ), accordingly, is strictly forbidden. The most harmonious marriage is said to be with the cross-cousin (anguleba ), a category that does not distinguish the mother's brother's daughter (MBD) from the father's sister's daughter (FZD); in both cases, the marriage is valued because it involves a "return" of descendants to the

house. In MBD marriage, the son "returns" to the house that his mother came out of, "following her tracks, retracing her steps" (na doku a wewena, na bali a orona ) to enter again the "door that he came out of, the steps that he came down" (tama la binye oro loho, la lete oro mburu ). In FZD marriage, the grandchildren will "return" to the walla of their grandfather, so that although their mother lives in a separate house and village, the house is once again associated with his matriline.

Both of these ideas of "return" play on the common Eastern Indonesian theme of the reunion of descendants of a brother and sister, which occurs after a generation of separation. The "return of the blood" provides a sense of closure for alliance cycles that is desirable in many societies (Barnes 1974, 248-49; Lewis 1988, 301; Traube 1986, 88), even if it is not always statistically achieved.

A census of 334 households (and 412 marriages) conducted in 1980 showed only 18 cases of cross-cousin marriage (10 with the MBD, eight with FZD) in the administrative ward (desa ) of Waiha, a relatively isolated region in Balaghar. A survey of exchange activities conducted in 1988 among 50 households in Bondo Kodi, however, showed a much higher incidence: 12 marriages with the MBD and 4 with the FZD. Bondo Kodi is the district capital and the residence of many important families; there, cross-cousin marriage was most likely to occur when the "return" involved a great separation in space, as when the son of a woman who had married into another district or region "followed her footsteps" back to her home region to seek a wife. Informants also argued that such marriages were more common in wealthy families, "who just want to exchange with each other" and do not want to disperse their valuables in new directions.

A prescriptive rule for asymmetric cross-cousin marriage is correlated in Sumba with increased social stratification. Those districts that are most clearly divided into social classes are also said to observe the rule most rigidly. Partly because they are increasingly aware of the diversity of social systems on the island, several Kodi observers provided me with astute commentary on the logic of these transformations:

Whenever we give a woman to another village, we will keep traveling that path for many years to come. If you are wealthy already, you want to give your daughter to someone who will take care of her, who shows his generosity in the bridewealth, and who will continue to demonstrate his respect with later payments. If they are already your wife-takers [laghia ], their name is good and you can be sure they will help out. Initially, you may ask for less bridewealth because there is already trust and love on the path. But if they are strangers, they must establish their good faith with larger pay-

ments. Otherwise, your valuables will travel down those paths and disappear.

Alliance sets up a mutual lending relationship, and credit is evaluated on the basis of a past history of exchanges. Thus, it is prudent for a wealthy family to marry "close"—among the group of families already linked to them as affines. The "return of the blood" is also a way of assuring the return of valuables, which "follow the path" along with the bridegroom who returns to his mother's village.

A more daring strategy involves investing in outsider groups who have amassed enough wealth to improve their social position through marriage. These groups may include wealthy families from other districts, who want to expand their alliance networks. Marriages that cross district boundaries are increasingly common, as well as prestigious, but they are always expensive. Instead of traveling a familiar path, the bridegroom must "cross over new pastures and cut through virgin forest" (na palango marada, na dowango kandaghu ). He offers more buffalo and horses to his wife-givers because (as some would say) "he is buying a social position as well as a wife."

Bridewealth payments from the groom's side are calculated in "tails": equal numbers of horses and buffalo, usually from ten to thirty. Each "tail" should be reciprocated from the bride's side with a man's and a woman's cloth, one long-tusked pig for each ten livestock animals presented, and a gold ear pendant. When the bridewealth is over thirty "tails" of livestock, then heirloom valuables such as ivory bracelets, a bronze ankle ring, a gold crescent headpiece, or imported glass beads might be added to the counterprestation. Interdistrict marriages negotiated in the last forty years have often involved bridewealths of a hundred or more livestock, and the shortage of traditional gold and ivory valuables has prompted a shift to new consumer goods—a bed, cupboard, dining table, or set of dishes can now be used to "match" the groom's payment.