Preferred Citation: MacCoull, Leslie S. B. Dioscorus of Aphrodito: His Work and His World. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1988 1988. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0m3nb0cs/

| Dioscorus of AphroditoHis Work and His WorldLeslie S. B. Mac CoullUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1989 The Regents of the University of California |

FOR MIRRIT

Dir gewidmet ist mein Leben:

deine Liebe sei mein Lohn.

Haydn, The Creation, No. 32

Preferred Citation: MacCoull, Leslie S. B. Dioscorus of Aphrodito: His Work and His World. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1988 1988. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0m3nb0cs/

FOR MIRRIT

Dir gewidmet ist mein Leben:

deine Liebe sei mein Lohn.

Haydn, The Creation, No. 32

Acknowledgments

I should like to express my thanks to the following institutions and people who have helped me during the nineteen years of work that went into this book: The American Research Center in Egypt; the American School of Classical Studies at Athens; the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; the British Library; the British School at Athens; the Institute of Christian Oriental Research and the Department of Semitic and Egyptian Languages and Literatures, Catholic University; Collège de la Sainte Famille (Pères Jésuites), Cairo; Columbia University; the Coptic Museum; the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Cairo; Duke University (Perkins Library and the Divinity School Library); the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, where I began my research and where much of the writing was done; the Egyptian Museum; the Franciscan Center for Christian Oriental Studies, Cairo; the French and Italian Archaeological Institutes at Athens; the Griffith Institute, Oxford; the Institut français d'Archéologie orientale, Cairo; the Library of Congress; the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Papyrussammlung); the Papyrussammlung, Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR); the Pierpont Morgan Library; the Pontifical Institute of Oriental Studies at Rome; the Society for Coptic Archaeology; and Trinity College, University of Toronto.

Levon Avdoyan, Roger Bagnall, Robert Bagnall, the late Paulinus Bellet, Monica Blanchard, Sebastian Brock, Francis Campbell, Florence Friedman, Jean Gascou, Francis Gignac, Sidney Griffith, Peter Grossmann, Ann Hanson and the late Arthur Hanson, Deborah Hobson, Susan Finan Ikenberry, Patrick Jacobson, James Keenan, Craig Korr, Enrico Livrea, Helene Loebenstein, Cyril Mango and Marlia Mundell Mango, Robert Markus, Elizabeth McVey, Kathleen McVey, Stephen Morse, Robert

Murray, John Oates, Lucia Papini, Thomas Pattie, the late Bernard Peebles, Lee Perkins, Rosario Pintaudi, Günter Poethke, Linda Collins Reilly, Kent Rigsby, Georgina Robinson, Cornelia Römer, P. J. Sijpesteijn, Emanuel Silver, the late Msgr. Patrick Skehan, Kenneth Snipes, Robert Taft, Janet Timbie, Claudia Vess, Gary Vikan, Guy Wagner, Claude Wehrli, the late Hans-Julius Wolff, and Klaas Worp.

I am grateful to the Göttingen Academy of Sciences, and to Professor Dr. Ernst Heitsch, now of Regensburg, for permission to reproduce the Greek texts in E. Heitsch, Die griechischen Dichterfragmente der römischen Kaiserzeit I–II (Abh.d.Akad.d.Wiss. in Göttingen, phil.-hist. Kl., 3.Folge, Nr. 49 & 58) (Göttingen 1961–1964).

I should like also to honor the memory of the late David Crawford, my predecessor in Cairene papyrology, who was martyred in 1952.

This book belongs in a special way to four people: Elliott Chapin, Maxwell Vos, Peter Brown, and Mirrit Boutros Ghali. "Work is love made visible." By now it will be clear to the person to whom this book is dedicated (do ut des) that it is scholarship and not money, kinship, or power that assures the perpetuation of a people's heritage. Where his treasure is, there will his heart be also. It is time for him to come home.

WASHINGTON & CAIRO

MAY 1988

Abbreviations

Abbreviations for papyri follow the forms established in J. F. Oates, R. S. Bagnall, W. H. Willis, and K. A. Worp, Checklist of editions of Greek papyri and ostraca, 3rd ed. (Greek papyri) and A. A. Schiller, "Checklist of Coptic documents and letters," Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 13 (1976) 99–123 (Coptic papyri). Other abbreviations used in this work are given below.

|

|

Preface

On n'écrit un livre

qu'avec la joie.

Fernand Braudel

It is just over a hundred years since Huysmans's des Esseintes led readers of the "decadence" on what would now be called a trip through the sensibility of Late Antiquity. And it is sixty years since Helen Waddell's singing prose made people begin to be aware that the classics did not come to an end with the age of the Antonines. I am lucky to have come of age as a scholar just at the time when the period after A.D. 284 began to come into its own.

During the past fifteen to twenty years there has been what may well be termed a paradigm shift in scholarly perception of the period A.D. 300–700. "Late Antique" people now have a "local habitation and a name," in Coptic a ma-n-shope,[*] a 'place to be'. This was not the case in the early days of papyrology. As E. Wipszycka has written, "Quant aux textes byzantins, avec leur écriture de type déjà médiéval et truffíe d'abréviations, avec leurs innovations linguistiques et leur orthographe souvent fantaisiste, ils éveillaient en eux [les premières générations de papyrologues] une répugnance instinctive."[1] I have been struck by the persistence of these older judgments since I began working on Dioscorus nineteen years ago.

The pioneers, Jean Maspero and Sir Harold Idris Bell, the first ever to read Dioscorus's papers, were repelled by what they were working on, and

[1] E. Wipszycka, "Le degré d'alphabétisation en Egypte byzantine," Rev.Et.Aug. 30 (1984) 282.

their distaste shudders from the pages of their editions. Bell wrote: "his personality, as revealed in the documents he has left us, certainly does not inspire respect, and his verses indubitably merit damnation; . . . his verses, if infamous as literature, are at least of interest as illustrating the morass of absurdity into which the great river of Greek poetry emptied itself."[2] Maspero wrote: "Le style est flou, les expressions inadéquates à l'idíe, la construction grammaticale souvent insaisissable. . . . Les idíes y sont nulles, l'invention en est tout à fait absente . . . Les concetti de mauvais goût, les jeux de mots de bel esprit provincial. . . . Ce jargon grotesque . . . avec ses platitudes boursouflíes et ses bizarreries de décadent."[3] Even J. G. Milne wrote: "At no moment has he any real control of thought, diction, grammar, metre, or meaning."[4] It is time to go back and read, with the resources of contemporary Late Antique scholarship, what actually stands on the surface of the papyri, instead of repeating the textbook caricatures of another age.

This task is begun. My teacher, and the teacher of so many of North America's papyrologists, the late C. Bradford Welles of Yale University, impressed upon all of his students the necessity of assessing the ancient world on its own terms by using primary sources.[5] Thanks to the work of Roger Bagnall, Klaas Worp, Jean Gascou, and James Keenan, among others, we are seeing the start of a rebirth of "Byzantine" (i.e., post-A.D. 300) papyrology. Without the help and amicitia papyrologorum of these colleagues, I would have worked in fruitless isolation. Instead, cooperative research in many disciplines has begun to create a sound basis for understanding the society of Byzantine-Coptic Egypt.

In an era in which one's very subject matter can be proclaimed subversive, in which it is no longer politically permitted to make discoveries in certain fields on their native turf, it is urgent that whatever remains of the culture of Christian Egypt be studied while it still exists. The change from forty or fifty years ago, when Bradford Welles and Pierre Jouguet did their work and then chatted about it in Groppi's, when the tables of contents of periodicals were filled with new Coptic finds, is frightening and sad. Lefebvre's boxes of Coptic papyri have been allowed to disappear. We must call attention to the threatened state of our field. To quote the late Benedict Nicolson, "tact and urbanity are the enemies of scholarship."

[2] H. I. Bell and W. E. Crum, "A Greek-Coptic glossary," Aegyptus 6 (1925) 177.

[3] J. Maspero, "Un dernier poète grec de l'Egypte, Dioscore, fils d'Apollos," REG 24 (1911) 427, 469, 470, 472. The number of times in P.Cair.Masp. he cannot resist putting the word "poète" into inverted commas is disconcerting.

[4] In P.Lit.Lond. (1927) 68.

[5] Compare A. E. Samuel's preface to his From Athens to Alexandria (Louvain 1983).

The work and the world of Dioscorus present their own coherence, the coherence of a world that loved life and that died an inexplicable death. Dioscorus wrote, in prose and verse, of a world of visible hierarchy and celebration: of Sirius rising to bring the inundation, of pageant and symbolic action, of Dionysos and his train in the fields, of the Parousia of Christ and of the finger of God writing on the imperishable tablets the name of the poet's friend. Working as he did at the meeting place of law and poetry, he knew that

EINZIG DAS LIED ÜBERM LAND

HEILIGT UND FEIERT.

I—

Sources and Life

Dioscorus does not always make sense to us moderns.

C. Bradford Welles

On a July day in 551, a leading citizen of Aphrodito, a city of Middle Egypt, stood in the office of Palladius, the count of the sacred consistory, in Constantinople. With him were three officers of his civic delegation, including a representative acting for one Shenoute, sometimes identified as his brother. Dioscorus, former protocometes or headman of Aphrodito and descendant of its leading family, was following in the footsteps of his father Apollos, who ten years before had come to the capital to defend Aphrodito's right of independent tax collection (autopragia). Conditions at home had since become worse, and it lay with Dioscorus and his fellow syntelestai (contributors) to put them right.

What in fact brought these people, townsmen of a provincial town, to a capital where their countrymen, the Apions, had already spectacularly made their mark? The right of citizens to appeal to the emperor; the awareness that the complexities of culture and faith that preoccupied them were unavoidably bound up with what happened in New Rome; a basic problem of both livelihood and status that needed to be resolved.

Concentrating on an individual, rather than a collectivity or a problem, is perhaps unfashionable; however, the accident of physical survival has preserved for us the personal papers of this individual, Dioscorus of Aphrodito, with a completeness unparalleled in the ancient world. We know the scope of his interests, literary and financial; what he noticed in

his surroundings; the shape of his mind.[1] We can even read his immediate thoughts in the form of the rough drafts of his poetry, written on the backs of legal documents from his office. He is uniquely representative of that Late Antique culture flourishing in Egypt from ca. 400 to 641 and after—a figure in a coherent cultural landscape.[2] The history of that culture is not yet written, but Dioscorus's life provides a door into that world.

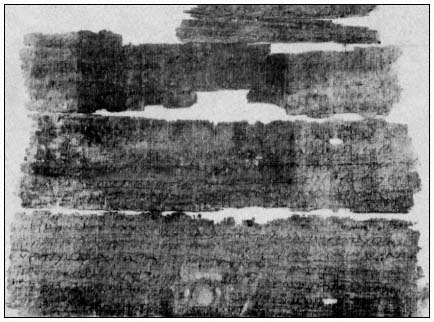

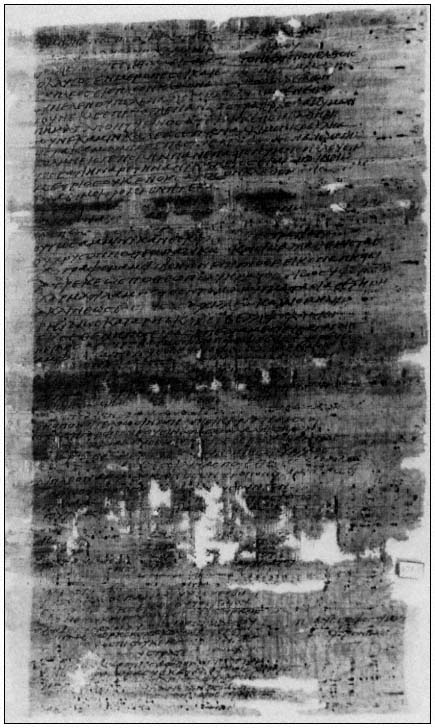

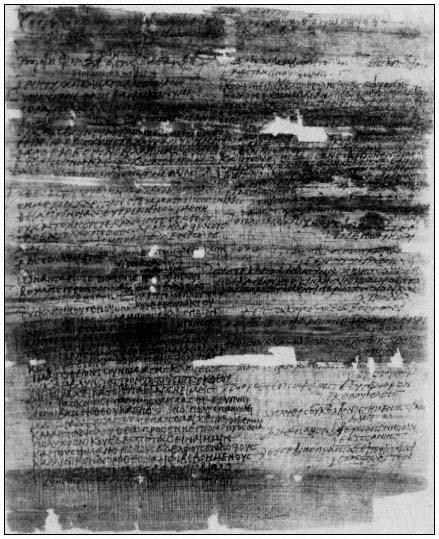

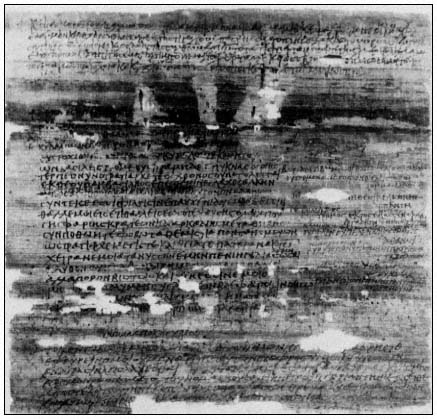

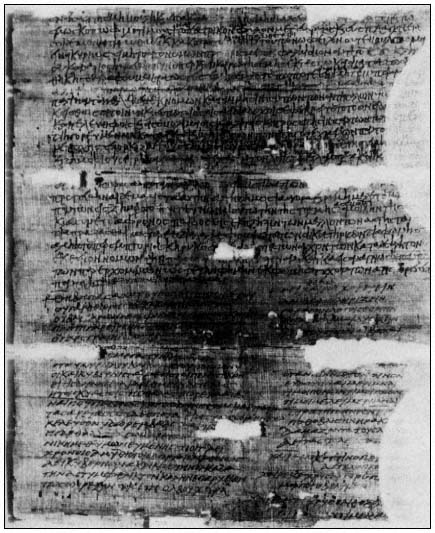

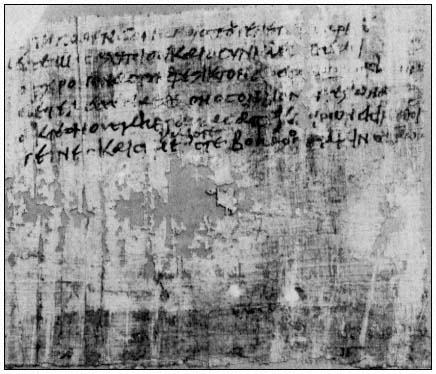

The Papyri

In 1901, during the reign of Khedive Abbas Hilmy and the proconsular administration of Lord Cromer, some villagers in Kom Ishgaw were digging a well. Their Upper Egyptian village lay on the left (west) bank of the Nile, four hundred miles south of Alexandria, south of the sizable and half-Christian city of Assiut, north of what had been Shenoute's White Monastery at Sohag. As so often happens in Egypt when digging is done, they found not water but antiquities: in this case papyri, masses of them, the bundled tax archives of a city. Someone called the police, but before anyone in authority could arrive, many of the papyri had been burned by villagers anxious not to be caught with the goods.[3] The surviving papyri were dispersed through middlemen and dealers, most to find their way to the British Museum and the University of Heidelberg. The science of papyrology was young then, and no scholar had ever seen anything like these voluminous tax codices written in thin, elegant, almost minuscule hands. Bel1[4] in England and Becker[5] in Germany identified them as the records kept by Greek and Coptic scribes under the eighth-century Arab administration of a town called Aphrodito.[6]

[1] The earlier surveys of Dioscoriana, unsympathetic to say the least, by J. Maspero, "Un dernier poète grec de l'Egypte, Dioscore, fils d'Apollos," REG 24 (1911) 426–482 and H. I. Bell, "An Egyptian village in the age of Justinian," JHS 64 (1944) 21–36, have been superseded. For general treatments, see now J. G. Keenan, "The Aphrodite papyri and village life in Byzantine Egypt," BSAC 26 (1984) 51–63; and L. S. B. MacCoull, "Dioscorus and the dukes: aspects of Coptic Hellenism in the sixth century," BS/EB 14 (1988).

[2] The words are those of A. Grafton, Joseph Scaliger (Oxford 1983) 229.

[3] J. Quibell, "Kom Ishgaw," ASAE (1902) 85–88; Keenan, "The Aphrodite papyri," pp. 51–63. On how the "pipeline" has always worked, cf. J. M. Robinson, "The discovering and marketing of Coptic manuscripts," in The roots of Egyptian Christianity, ed. B. Pearson and J. Goehring (Philadelphia 1986) 2–25.

[4] H. I. Bell, "The Aphrodito papyri," JHS 28 (1908) 97–120.

[5] C. H. Becker, "Arabische Papyri des Aphroditofundes," Z.Assyriol. 20 (1906) 68–104; cf. idem, "Historische Studien über das Londoner Aphroditowerk," Der Islam 2 (1911) 359–371.

[6] The major publications are P.Lond. IV (1910) and P.Schott-Reinhardt (1906).

Four years later, in 1905, matters repeated themselves, again by sheer chance. During house-building operations in Kom Ishgaw, the mudbrick wall of an old house collapsed, revealing deep foundations that had covered over yet another massed find of papyri. The local grapevine alerted Gustave Lefebvre, the inspector of antiquities, who hurried to the spot.[7] A few acts of destruction similar to the earlier burning had taken place, but this time most of the papyri were dispersed to dealers, and thence worldwide from Imperial Russia to the American Midwest,[8] to libraries eager to participate in the new rebirth of Greek literature made possible by papyri. Among the papyri there was indeed a text of Menander;[9] but the body of the find consisted of the private and public papers of the sixth-century owner of that text, the lawyer and poet who would become known as Dioscorus of Aphrodito.[10]

The papyri that Lefebvre managed to keep from middlemen and traffickers he brought to the Museum at Cairo (then at Boulaq). He went back to Kom Ishgaw twice more, in 1906 and 1907, and succeeded in finding more sixth-century papyri on the site of the original find. A few had been bought by a M. Beaugé, of the railway inspectorate at Assiut. These documents also were brought safely to Cairo, and the whole lot was assigned to the editorship of Jean Maspero, a young classical scholar and son of the head of the Antiquities Service, Gaston Maspero. Before his death in battle in 1915, Jean Maspero managed to produce the three pioneering volumes of Papyrus grecs d'époque byzantine, of which the first was published in 1911. Together with Bell's 1917 edition of the sixth-century Aphrodito

[7] J. Maspero, "Etudes sur les papyrus d'Aphrodité," BIFAO 6 (1908) 75–120, 7 (1909) 47–102, 8 (1910) 97–152; cf. his preface to P.Cair.Masp. I (1911). Because the eighth-century papyri were the first from the site to become known, the form found in those later documents, "Aphrodito, " with a Greek omega, first found its way into the scholarly literature. As the sixth-century documents from the second find began to be read, the form "Aphrodites[*] kome[*] " from the earlier period came to be known. But although the form Aphrodito is, strictly speaking, a retro-usage from the Arab period, it is more common in writings about the site, and Dioscorus is universally known as "Dioscorus of Aphrodito." In one way it would be more accurate always to refer to the sixth-century city as Aphrodite, as some scholars do at present. But in this work I have kept the old familiar form.

[8] See G. Malz, Papyri of Dioscorus: publications and emendations," Studi Calderini-Paribeni 2 (Milan 1957) 345–356; add Hamburg, Vienna, the Vatican, and Ann Arbor to her list.

[9] Photoreproduction, L. Koenen et al., The Cairo codex of Menander (London 1978).

[10] The find made earlier (in 1902) thus contained material of later date (eighth century, as above, n. 7); the later find (in 1905, 1906, and 1907) contained material of earlier date (sixth century), namely, the Dioscorus papers. It is the material from the second Aphrodito find with which this book deals. No oldest inhabitant of Kom Ishgaw in the 1980s remembers from childhood anything his parents or grandparents might have related about the original findspots of the papyri; I was unable to trace either one.

papyri that had been acquired by the British Museum (P.Lond. V), and Vitelli's 1915 edition of those bought by the University of Florence (P.Flor. III), these texts constitute the bulk of what we know as the Dioscorus archive of sixth-century Aphrodito, the city that lay under Kom Ishgaw.

Our evidence for the life, work, and world of Dioscorus thus comes from one find (over time) from one place, in preservation widely dispersed, yet in intention forming a unity. The papers kept during a single human lifetime that spanned much of the sixth century reveal the background, activities, and interests of the person who chose to keep them. Numerous discoveries of Byzantine Egyptian remains at sites all along the Nile Valley, from the Fayum to Syene (Aswan), provide a perspective on the period broader than could be obtained from the archives of just one individual in one city. Most of these discoveries were made in the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, when the political climate still allowed exploration in the field of what was once Christian Egypt. Dioscorus can thus be placed in the wider context of his land and his times, on the basis of evidence that, though for the most part long known,[11] remains underutilized. Because we meet him firsthand in his own words, the single figure of Dioscorus of Aphrodito as seen in and through his archive remains the most accessible introduction to the moeurs and the mentalités of sixth-century Egypt.

The paperwork surviving from Byzantine Aphrodito falls into numerous categories, both public and private. Of the public documents we have petitions, depositions before officials, proclamations and edicts (

[11] Papyri from clandestine native diggings at Kom Ishgaw in the late 1930s are just beginning to be known: see L. S. B. MacCoull, "Missing pieces of the Dioscorus archive," Eleventh BSC Abstracts (Toronto 1985) 30.

observed directly and in illuminating detail. At intervals over a period of six years, the present writer has worked at first hand with all of the Dioscorus papyri in Cairo.[12] After struggling with the difficult conditions, bad state of preservation, and frustrating logistics of this depot, one sees the realities of Dioscorus's world in an even sharper light.

The Place

Aphrodito stands on a hill.[13] Unusual among Egyptian sites, which more often lie below the present ground level, the modern village of Kom Ishgaw perches atop a tell that must conceal remains of the Byzantine and Umayyad city (see Figure 2). Aphrodito has never been scientifically explored.[14] The papyrus finds were made by accident, and Quibell and Lefebvre simply looked around the papyrus findspots to gather what they could in the way of artifacts—only a few carvings of wood and bone; the late period was of little interest at the beginning of this century. We do not know what Dioscorus's house or the Apa Apollos monastery looked like. Until, in some better future, field archaeologists have found the physical remains of the Byzantine/Coptic environment:, we can try to reconstruct the city of Dioscorus from the documents, and view it in its own landscape.

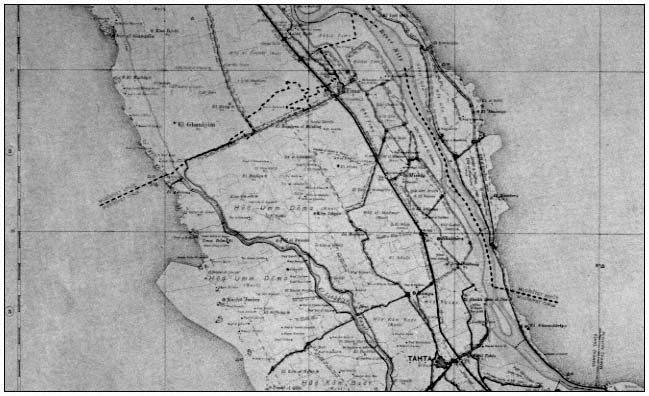

Kom Ishgaw lies amid a network of irrigation canals in the wide cultivated belt west of the Nile's edge (see Figure 3). South of Assiut, the road toward Kom Ishgaw[15] goes by Sidfa with its Uniat school; Tima, largely Christian even today; the Uniat bishopric of Tahta; and Shotep, the ancient Hypselis, where the late sixth-century Coptic exegete Rufus wrote his extensive biblical commentaries.[16] This is a Christian heartland of great antiquity. Some 45 miles to the south is Shenoute's town, Sohag; across the

[12] Only now are some of P.Cair.Masp. becoming accessible to the outside world through photographs made by the International Photographic Archive of Papyri (IPAP). A reedition, projected by Professor J. G. Keenan, would be most desirable. With the other collections one is more fortunate. Firsthand work in London is uncomplicated, and reproductions from nearly all collections are obtainable to facilitate research on Dioscorus papyri beyond the level of the (often early and unsatisfactory) editiones principes.

[13] I am grateful to the pastor of St. George's Coptic Orthodox Church at Kom Ishgaw and the staff of the Lillian Trasher Orphanage at Assiut for help in visiting the site in 1980–1981.

[14] A survey is planned by Professor J. G. Keenan of Loyola University, Chicago (cf. ARCE Newsletter, April 1986).

[15] For an amusing older account, see Bell, "An Egyptian village," p. 21.

[16] The fragments are now being collected and edited by Dr. Mark Sheridan, O.S.B.

river from that lies the Panopolis (Akhmim) that was the target of Shenoute's attacks on paganism and gnosticism.[17] East of these twin cities, up the river's bend, is the Pachomian headquarters of Pbow (near Chenoboskion), where the monastic library once included Homer, the Bible, Menander, and the Vision of Dorotheos;[18] in the same vicinity were deposited the texts that have become famous in our own time as the Nag Hammadi Codices. To the north, some 110 miles by river, lie the chief twin cities of Upper Egypt: Hermopolis on the west bank, and Antinoopolis (Antinoë), seat of the Duke of the Thebaid, directly across the Nile on the east. Around Aphrodito itself are the well-documented monastic sites of Bawit, Der Bala'izah, and Wadi Sarga. Dioscorus, the proud son of an elite family, was at home in a landscape of deeply rooted classical and Christian culture. This is the land of the wandering poets and of the founding fathers of the Coptic church.

Dioscorus was, as well, a citizen of no mean city. If buildings and amenities help to define a city, Aphrodito had its share. Its name in Egyptian, (

[17] Dioscorus's kinsman by marriage, Fl. Phoebammon son of Triadelphus, leased land in the nearby area of Phthla that belonged to Shenoute's monastery (P.Ross.-Georg. III 48; cf. J. G. Keenan, "Aurelius Phoebammon, son of Triadelphus, a Byzantine Egyptian land entrepreneur," BASP 17 [1980] 145–154).

[18] J. M. Robinson, "Reconstructing the first Christian monastic library," Smithsonian Institution Libraries lecture, 15 September 1986.

[20] For the structures and streets of Aphrodito, see A. Calderini, Dizionario dei nomi geografici e topografici dell'Egitto greco-romano I.2 (Madrid 1966) 323–325.

and canals; they seem to have changed little, except for Ottoman-period dilapidation and modern metal waterwheels, since Dioscorus's lifetime. Above all, Aphrodito and its surrounding area boasted over thirty churches and nearly forty monasteries, as well as dozens of farmsteads whose names recall original religious or monastic owners or settlers.[21] None remain standing; but in the sixth century this one Byzantine Egyptian city must have gleamed with white limestone and the columns and arches of basilicas along every vista. Religious building was an index of excellence,[22] and Aphrodito was a city of churches (see Figure 4).

Greater Aphrodito was a sizable settlement. Despite the many difficulties of method that beset attempts to estimate its population, from the indices of personal names recorded in published papyri it might be reasonable to posit, for the sixth century, some three thousand tax-paying male heads of household. This would give a population of about fifteen thousand. Its landholdings in the Antaeopolite managed to balance marginality with fertility. Despite difficulties with the weather and the rapacity (attempted or successful) of officials, we know, for example, that for just one assessment of the first quarter of the sixth century there were nearly four thousand arouras (about eleven million square meters) planted in wheat, seventy-two in barley (for beer), and nine in vineyards (P.Freer 2 III 26). With yields from tenfold to twentyfold (on sowings of one artaba, thirty to forty liters, per aroura), we would be dealing with a global production of sixty thousand artabas, or four artabas (four hundred pounds) of basic grain foodstuff per person per year. (This, of course, is reckoned for after the embole or grain for Constantinople was collected and skimmed

[21] Evidence collected in S. Timm, Das christlich-koptische Ägypten in arabischer Zeit III (Wiesbaden 1985) 1438–1461, s.v. 'Kom Isqaw[*] .'

off.) Over and above this quite adequate subsistence level, supplemented by meat from the herds of sheep and honey from the beekeepers, the landlords and syntelestai (contributors, or members of the landowners' koinon ) dealt in surpluses that enabled them, as local dynatoi, to support the cultural flowering that distinguishes this period of Egypt's history.

The canal system had only a short distance to lift water from the river, which brought luxury goods and human skills. Even the less productive land was put to work as pasture, looked after by often unruly shepherds[23] who were conscripted as field guards. Although Dioscorus on occasion pleaded poverty, for rhetorical effect, his world was a prosperous one. It seems to have suffered hardly any effects from the sixth-century plague.[24] Trades, professions, the civil service, the military, and the church are abundantly represented.[25] Dioscorus's learning—poetic, rhetorical, legal, and biblical—was undergirded by a thriving material culture; his personal landscape was far from being one of deprivation. And the events of his life can be traced through transactions that reflect every aspect of this rich environment.

Dioscorus was a Coptic dynatos,[26] a member of his society's most prominent and privileged group, Alexandria educated,[27] widely traveled, and living halfway between the two districts of the Hermopolite and the Panopolite that were headquarters of classical learning in Egypt. As such, he was far from being the lowbrow Copt too often caricatured by historiography.[28] Rather, he exemplified the kind of local propriétaire who supported and made possible the high creativity of Coptic culture. In Alexandria he became familiar with the best of Monophysite and Aristotelian thought (and the anti-Nestorian and the beginnings of anti-Chalcedonian controversies of the period that sparked such work), and had become

[23] J. G. Keenan, "Village shepherds and social tension in Byzantine Egypt," YCS 28 (1985) 245–259.

[24] Cf. G. Casanova, "La peste nella documentazione greca d'Egitto," Atti XVII congr.intl.papirol. (Naples 1984) 949–956, esp. 954. Dioscorus's reference in P.Cair.Masp. III 67283.9 (of A.D. 547/8) is figurative, not literal.

[25] See L. S. B. MacCoull, "Notes on the social structure of late antique Aphrodito," BSAC 26 (1984) 65–77.

[26] Cf. F. Winckelmann, "Ägypten und Byzanz vor der arabischen Eroberung," Byzantinoslavica 40 (1979) 161–182, and idem, "Die Stellung Ägyptens im oströmischbyzantinischen Reich," in Graeco-Coptica, ed. P. Nagel (Halle 1984) 11–35.

[27] See L. S. B. MacCoull, "Dioscorus of Aphrodito and John Philoponus," Studia Patristica 18 (Kalamazoo 1987) I.163–168.

[28] Still repeated in D. W. Johnson, "Anti-Chalcedonian polemics in Coptic texts, 451–641," in Pearson and Goehring, Egyptian Christianity, 230–233. There is no evidence whatever for a Roman/Byzantine plot to keep the Copts an "underclass."

acquainted with the new Digest and Codex of Justinian in his student days. He had in his youth lived through the forcible replacement of Patriarch Theodosius by Paul of Tabennisi (from the nearby Pachomian headquarters); for most of his lifetime he would live through a period of vacancy of the non-Chalcedonian patriarchal see, until the accession of Damian in 578. The period of his youth (especially from 531 to 538) witnessed the development of the Monophysite church of Egypt; he would have been aware of the death in Egyptian exile, in 538, of Severus of Antioch, already a culture hero, and of Jacob Baradaeus's journeys in support of non-Chalcedonian clergy. In the imperial capital he visited, Justinian's theological activity would have been evident. And Dioscorus's pride in and indebtedness to his fifth-century predecessors in the craft of poetry are apparent.[29] Present to his mind were the language of Homer and Nonnus, and of Shenoute, the Pachomian corpus, the Apophthegmata, and the Bible with its extensions in liturgy and hagiography. In tracing the events of Dioscorus's life, we are not to lose awareness of the wider world within which that life unfolded.

The Career

We can infer, from the dates in the archive, that Dioscorus was born about A.D. 520. His father was the former protocometes (village headman) Apollos, later to become a monk; his grandfather another Dioscorus; his great-grandfather Psimanobet (Coptic for 'the man from the place of geese').[30] From his writings it is obvious that he received the best education in the classics and the law that was available, most probably at Alexandria.[31] True to the Mediterranean paramount value of family, he married and fathered children. And he embarked upon the sort of legal and administrative career only to be expected of the scion of Aphrodito's first family.

[29] As is his combining this craft with the life of a public man of affairs. If the epithalamium in P.Ryl. I 17 dates to the fourth century (Hermopolite), its technique foreshadows that of Dioscorus in his own wedding poems; if the address to the Nile in PSI VII 845 dates to the sixth century (provenance unknown), it would be interesting to know its Sitz im Leben (is the anti-women tone the result of some particular local social problem?). Could the encomium in P.Flor. II (Heitsch 36), with its Heracles figure that was to be so familiar to Dioscorus, be by Pamprepius of Panopolis (see Chapter 3)?

[30] Or "the gooseherd."

[31] Cf. the discussion of his educational background in MacCoull, "Dioscorus of Aphrodito and John Philoponus," pp. 163–168.

The first dated document from Dioscorus's archive, P.Cair.Masp. I 67087 of 28.xii.543, shows him involved in a case at law concerning damage to a field, before one Colluthus, boethos of the court at Antaeopolis, the former nome capital.[32] Dioscorus was successful in getting the defensor to fill out a deposition. His title is already Flavius (the higher rank), as was that of his father (who had formerly been an Aurelius, the lower rank).[33] In the following year Aurelius Apollos, son of Hermauos, sold him wool for one-third solidus, payable on delivery (P.Cair.Masp. II 67127). In 546 he made a loan to two Aphroditan farmers (P.Eg.Mus.inv.S.R. 3733 A6r). In 547 he leased land to a priest and his brother (P.Cair.Masp. I 67108), and cosigned the transfer of land tax in a document in which the priest Jeremiah son of Psates ceded land to him (just under two arouras of sown land, plus reed-growing land and wooded land: P.Cair.Masp. I 67118 of October 547). On 27 August of the same year, as protocometes, he leased one aroura to the deacon Psais, son of Besios and Tasais (P.Cair.Masp. II 67128). Altogether the usual sort of activity for the young squire-jurist.[34]

The year of 547/8, an eleventh indiction (cf. poem H6 in Chapter 3), was a troubled year for Aphrodito. The inhabitants petitioned Justinian (P.Cair.Masp. I 67109v) and Theodora (P.Cair.Masp. III 67283) for protection of their right of autopragia, independent tax collection, against the rapacity of the pagarch of Antaeopolis. Dioscorus's tenant Aur. Psaios was remitted part of the rent he owed (ten artabas of grain) for the coming twelfth indiction (P.Cair.Masp. I 67095, 1.iv.548), while Dioscorus leased one aroura to the weaver Victor for flax planting (P.Cair.Masp. I 67116). Again in 549 (14.viii) he leased three arouras of land to the same deacon Psais (P.Cair. Masp. II 67129), and he lent money (one solidus less three keratia) to the priest Jakubis son of Abraham (P.Cair.Masp. III 67251, 18.x). His landholdings increased in 550, with a cession to him of land by Psates, reader in the principal church of Aphrodito (P.Cair.Masp. I 67108), in conjunction with a dowry dispute.

The following year found Dioscorus in Constantinople, having audience, together with his colleagues, Callinicus son of Victor, Cyrus son of Victor (representing, probably, Dioscorus's brother Senouthios), and Apollos son of John, with Fl. Palladios, count of the sacred consistory (P.Cair.

[32] See the remarks of Keenan, "Village shepherds."

[33] Cf. P.Cair.Masp. I 67064.13–14, a letter to Apollos complimenting his son the lawyer. On Apollos's upward social mobility, cf. J. G. Keenan, "Aurelius Apollos and the Aphrodite village elite," Atti XVII congr.intl.papirol. (Naples 1984) 957–963.

[34] On this sort of career, among Dioscorus's contemporaries and connections, cf. Keenan, "Aurelius Phoibammon," pp. 145–154. For Dioscorus's own career, cf. H. Comfort, "Dioscorus of Aphrodito as a lawyer," TAPA 65 (1934) xxxvii.

Masp. I 67032). They obtained an imperial rescript ordering the duke of the Thebaid to undertake an official inquiry into Aphrodito's right of autopragia (P.Cair.Masp. I 67024–67025).[35] (Soon after this, perhaps in July or August 551, Dioscorus wrote his isopsephistic poem on S. Senas, perhaps in thanksgiving for the outcome of his journey.[36] ) Dioscorus also obtained help in the capital with problems concerning his inheritance (P.Cair.Masp. I 67026–67027–67028), which are mentioned later in his encomiastic poetry. The documentation that has survived from this visit gives telling glimpses of the bureaucratic mind at work: the Constantinopolitan officials are eager to settle the matter before it reaches the ears of the emperor.

In connection with Dioscorus's return from the capital,[37] there appear his first efforts at encomiastic poetry (H6 and H8: see Chapter 3), written in hexameters and seasoned with autobiographical allusions. In the same year, 553, he of course continued working: he rented out a wagon (cf. P.Vat.CoptiDoresse 1)[38] for harvest transport to a group of farmers headed by Aur. Menas (P.Cair.Masp. III 67303, 27.iv.553). Still protocometes in this year (P.Cair.Masp. III 67332), he wrote a tax agreement addressed to the pagarchs Julian and Menas (P.Lond. V 1661, 24.vii).[39] In 555 (3.v) he leased pastureland to George son of Psaios, a shepherd from Psinabla in the Panopolite (P.Lond. V 1692), and in 557 he made a loan to the deacon Mousaios son of Callinicus (P.Cair.Masp. II 67130, 25.ii). For the last years of the reign of Justinian, we have no further dated transactions from his archive.[40]

The accession of Justin II in November 565 saw Dioscorus having

[35] Cf. V. Martin, "A letter from Constantinople," JEA 15 (1929) 69–102; R. G. Salomon, "A papyrus from Constantinople," JEA 34 (1948) 98–108. And see G. Geraci, "Dioskoros e l'autopragia di Aphrodito," Actes XV congr.intl.papyrol. 4 (Brussels 1979) 195–205; G. Poethke, "Metrocomiae und Autopragie in Ägypten," in Nagel, Graeco-Coptica, pp. 37–44.

[36] See my commentary in "The isopsephistic poem on St. Senas by Dioscorus of Aphrodito," ZPE 62 (1986) 51–53.

[37] Dated by Maspero ("Un dernier poète grec de l'Egypte, Dioscore, fils d'Apollos," REG 24 [1911] 460–466) to 553. I have refined the chronology somewhat.

[38] See L. Papini, "Annotazioni sul formulario giuridico di documenti copti del VI secolo," Atti XVII congr.intl.papirol. (Naples 1984) 767–776; eadem, "Notes on the formulary of some Coptic documentary papyri from Middle Egypt," BSAC 25 (1983) 83–89. She dates these papyri to either 520–522+ or 535–537+ (the latter seems more likely).

[39] Compare the texts in BIFAO Bulletin du Centenaire (Cairo 1981) 427–435.

[40] However, P.Lond. V 1686 and P.Cair.Masp. II 67170–67171 have been redated to 564/5: R. S. Bagnall and K. A. Worp, "Chronological notes on Byzantine documents, V," BASP 17 (1980) 19–22. The thirteenth indiction in P.Berol. 11349.37 might, however, be 564, as the document describes Dioscorus's problems with a negligent tenant. (But 579 is also possible.)

moved from Aphrodito (cf. P.Cair.Masp. III 67319) to Antinoë, seat of the Duke of the Thebaid, where he sought to reestablish himself as a jurist through exercise of his talent as an occasional poet.[41] (In Byzantine Egyptian society, a well-turned verse could serve as a self-advertisement and a job application.) He wrote a hexameter encomium to the image of the emperor,[42] and an iambic poem addressed to Victor the hegemon (praeses) asking to serve in the city as notarios (see Chapter 3). In this year he sold land to the monastery of Sminos (Zminos) in the Panopolite (P.Lond. V 1686, 7.xi), and wrote a lease of a pomarion or plot of gardenland together with its trees and plants, irrigation machinery, and a mudbrick shed, on behalf of the same house (P.Cair.Masp. II 67170–67171). He also leased land in the north property of Pka(u)met to Aur. Psempnouthios, a mechanarius (P.Cair.Masp. I 67109, 18.vii).

These were busy years for Dioscorus, the lawyer and poet. In 566 (28.ix) he was retained by Aur. Athanasia in a case at law to claim an inheritance from her father (P.Cair.Masp. II 67161); and he drew up the division of an inheritance among a widow and her five sons (P.Cair.Masp. III 67314). He paid off a debt owed by his late father Apollos and his brother Senouthes (P.Hamb. III 231, 22.ii; cf. P.Mich. XIII 669). Also from this year or the year or two following come his arbitration of an inheritance for Phoebammon the stippourgos (flax worker), P.Lond. V 1708, and the poem fragment P.Lit.Lond. 101 (cf. P.Cair.Masp. 67055 and 67179), on the verso of P.Lond. V 1710, a piece of an encomium. (For the chronology of Dioscorus's complete poems, see Chapter 3.)

In 568 Dioscorus drew up a contract (28.iv) for Aur. Psois and Aur. Josephis son of Pekysis, carpenters (P.Cair.Masp. II 67158), and executed a loan contract wherein John, deacon of the monastery of S. Victor at Pindaros in the Antinoite, lent Fl. Christopher of Antinoë two solidi without interest for two months (P.Cair.Masp. II 67162, 22.v). He also wrote the document in which Aur. Colluthus, poulterer, paid a debt of two solidi to Aur. Martin of Antinoë, a dependent of the noble house of Duke Athanasius (P.Cair.Masp. II 67166, 15.iv). In 569 he had even more to do: when Fl. John son of Acacius, logisterius of Lycopolis, borrowed fifteen solidi from Aur. Maria, daughter of Cyriac the scholasticus (lawyer) and granddaughter of the late illustris Theodosius (P.Cair.Masp. III 67309, March), it was Dioscorus who drew up the contract. He acted similarly when Fl. Victor,

[41] On some elements of the unrest leading to his move, see Keenan, "Village shepherds," 245–259. Cf. P.Hamb. III 230.

[42] See L. S. B. MacCoull, "The panegyric on Justin II by Dioscorus of Aphrodito," Byzantion 54.2 (1984) 575–585.

son of the late scholasticus Phoebammon[43] and grandson of the late Count Thomas of Antinoë sold one aroura of land to Aur. Melios (P.Cair.Masp. II 67169 and 67169bis, 11.ii). (It would seem that the lawyer class was sticking together to help one another.) Dioscorus also wrote the loan contract in which Aur. Colluthus son of Lilous, vegetable seller at Antinoë, lent nine and one-half keratia to Aur. Colluthus son of George, butcher in the city (P.Cair.Masp. II 67164, 2.x), a transaction involving people of more modest class.

Dioscorus executed two transactions in this year recorded and preserved in Coptic: the land cession, P.Cair.Masp. II 67176r+P. Alex.inv.689 (dated 28.x.569),[44] and the arbitration, P.Cair.Masp. III 67353r. In the first document, we meet the principals, two half-brothers, Julius son of Sarapammon and Anoup son of Apollo, who reappear in the second papyrus. Julius and Anoup were making arrangements for their property before entering the monastic life (see Chapter 2). Also likely to be dated to 569 or shortly thereafter is Dioscorus's other Coptic arbitration, P.Lond. V 1709, which begins with the same formulary phrases as does 67353r. The London document deals with the affairs of another family, that of Phoebammon and Victorine and their half-sister Philadelphia, children of the late deacon John, another dependent of Duke Athanasius's house. These Coptic proceedings afford precious evidence for the conduct of cases and the development of Coptic private law before the Arab conquest.

In 570, Dioscorus, still in Antinoë, drew up the will of Fl. Phoebammon, the chief physician of the city (P.Cair.Masp. II 67151–67152, 15.xi). He also produced a contract of divorce (P.Cair.Masp. III 67311) and drafted a request to the new Duke of the Thebaid, Callinicus, passing on a complaint by one Apollos of Poukhis against the topoteretes (tax warden) of Antaeopolis (P.Cair.Masp. III 67279). From these years come poems addressed to Duke Callinicus himself: while still with the rank of count he had been the recipient of Dioscorus's epithalamium H21, on the occasion of his wedding to Theophile, and his accession to the dukedom is celebrated in the hexameter encomium H5 (see Chapter 3). Most of Dioscorus's occasional poetry

[43] Cf. P.Cair.Masp. III 67312, 31.iii.567, the will of his brother, Fl. Theodore; and P.Cair.Masp. III 67299, a land lease.

[44] I am grateful to Professor K. A. Worp of Amsterdam for accurately reading the dating clause. Text and commentary appear in L. S. B. MacCoull, "A Coptic cession of land by Dioscorus of Aphrodito," II intl.congr.copt.stud. (Rome 1985) 159–166. See L. S. B. MacCoull, "The Coptic archive of Dioscorus of Aphrodito," Cd'E 56 (1981) 185–193; eadem, "Additions to the prosopography of Aphrodito from the Coptic documents," BSAC 25 (1983) 91–94. The antiquated prosopography of V. Girgis, Prosopografia e Aphroditopolis (Berlin 1938), needs to be replaced; a guide to the Aphrodito archives is in progress.

and his variations on his own favorite themes are dated in this Antinoë period.

By 573 Dioscorus had returned to Aphrodito. His work in the ducal capital was done, and pressing business involving his family holdings recalled him—again the classic life pattern of the Mediterranean landed gentry. Acting as agent for the monastery of Apa Apollos, which his father had founded, he drew up the contract in which a monk of the house, Psates, donated a building site and two solidi to found a xenodocheion (P.Cair.Masp. I 67096).[45] Dioscorus appears to have been less active as a lawyer after his return to Aphrodito, but from this period (573–576) comes his most ambitious poetic effort, the pair of encomia on Duke John (H2 and H3; see Chapter 3). In these elaborate productions, blending elements of earlier styles of work, he included elegant, almost baroque self-references to leading themes of present and past years, and even a quick glance at the Tritheist controversy.[46]

The latest datable document from Dioscorus's archive is a leaf from the eight-page account book P.Cair.Masp. III 67325, IVr 5 bearing the date 5.iv.585 (Pharmouthi 3, third regnal year of Maurice, third indiction). The accounts, in Dioscorus's hand, seem to come from a few years earlier—the eighth indiction of Iv 14 must be 574, not 589. His account keeping continues serenely in the expected vein of concern for the local landlord: receipts and disbursements of grain, seed grain, amounts of chickpeas and of mud for bricks; payments for a camel driver and a builder; many ecclesiastical tenants, including "Apa John my in-law." There is even a local field that has come to be known by the name

So sketched, outlined from a list of documents, the bare bones of a life seem like the record of days of a Japanese minor court poet or a Chinese official, doing his job and producing polite literary effusions on festive occasions. Too, the culture of Byzantine Egypt was one in which literary cultivation was the sine qua non, the way to office and advancement. But this province was, above all, the place and the time, where all the traditions

[45] Cf. ZPE 26 (1977) 279.

met and cross-fertilized, and this process is what we see at work in Dioscorus's life and productions. His abundant papers embody in every phrase his society's characteristic presuppositions about the world—the total ease in which Christianity and the pagan learning were interwoven without a second thought, the visual opulence, the varying weights of value given to different areas of learning, the uniqueness of what was local and familiar.[48]

The glimpse we get of the values and the morale of Dioscorus's class gives a new and fresh twist to Rostovtzeff's preoccupation with the possibility of attenuating the forms and the matter of a culture. This local aristocracy was deeply rooted in its own heartland, its own landscape; cosmopolitan bearers of Hellenic culture though they may have been, they never forgot the textures and flavors of their home province. Their classicism, like their Christianity, was worn with a local flair.

We might also, parenthetically and for comparison, consider the role of the Apions, the Psimanobets' grander neighbors, people who had held the highest offices and married near-royalty. To what extent were they Egyptians and to what extent Constantinopolitans, if the question can be asked at all? They were Egyptians who had moved out and up; but compare the remarks of Alan Cameron.[49] He draws a picture of their boredom (or that of their spouses) on the obligatory visits to Oxyrhynchus (a phenomenon not unknown among their twentieth-century counterparts). Dioscorus never sat in the imperial cabinet, but he functioned, as decade succeeded decade, as one of the people who held the society together. Though not an office-holder in the capital, he embodied the best qualities of local loyalty and of what a traveled and experienced person could bring to local culture.

In Dioscorus's contracts and poems, the phrases create their own universe. We shall watch this happening in detail in the poetry and the prose. Perhaps, after all, this vision is the real gift of Late Antique Egypt, not just the monastic movement or the other facile suggestions: the ability to take a Homeric tag or an Aristotelian truism learned at school and transmute it into a koan, a counterintuitive paradox, seeming not to make sense, yet that shakes our foundations, making us rethink our assumptions. Dioscorus's world gave birth to its own riddles, and its own solutions.

[48] "A common-sense quest for local solutions to the urgent problem of maintaining a traditional way of life, on the part of an aristocracy whose horizons had always been at least partially local." P. Wormald, review of Western aristocracies and imperial court by J. F. Matthews, JRS 66 (1976) 222.

[49] Alan Cameron, "The house of Anastasius," GRBS 19 (1978) 268–269.

II—

The Greek and Coptic Documents

I fought the law, and the law won

Bobby Fuller

To be a jurist in the mid-sixth century was to be at the leading edge of learning. The careers of such men as Agathias[1] and Tribonian[2] stand out against a background of the unknown thousands of provincial lawyers who kept the empire running. The phenomenon of the jurist as a man of letters, far from unknown in the English-speaking world and on the Continent, was also notable in Late Antiquity. The prose writings of Dioscorus of Aphrodito come from a literary background in which skill in classical learning stamped the local writer as a recognizable member of the shared culture.

The growing rhetoricization of legal acts[3] reflected a combination of

[1] Averil Cameron, Agathias (Oxford 1970) 1–11.

[3] There is abundant literature on the process of rhetoricization of the law, a process that had been going on since the heyday of the Second Sophistic. The broad theories of J. Stroux, Römische Rechtswissenschaft und Rhetorik (Potsdam 1944) are no longer accepted (cf. L. Wenger, Die Quellen des röm. Rechts [Vienna 1953]); see A. A. Schiller, Roman law (The Hague 1978) 569–571, 582–584. But compare F. Schulz, Roman legal science (Oxford 1946) 262–277, 295–299 (cf. 328–329). When the Florence concordance to the Greek Novels is finished, much work will be facilitated (cf. Honoré, Tribonian, chaps. 3 and 4). Much of the legal literature of this period still lurks in the adespota of Roger A. Pack, The Greek and Latin literary texts from Greco-Roman Egypt[2] (Ann Arbor 1965). We might think also of thejuristic fragments from the binding of Nag Hammadi Codex VIII (see NHS 16, Leiden 1981). The rhetoric of the law is seen even more in the praxis of the documents than in the prescriptions of jurists.

the classical training required by society and the permeation of language by scriptural and patristic echoes. A legal document as it came from Dioscorus's pen was far from a dull, flat-footed, matter-of-fact record of a transaction. But it was also not simply a verbose exercise in the sound of one's own voice or the freakishly antiquarian hunt for obscure words.[4] Even more so than a poem, a legal document was a mirror of his world, inasmuch as it was a working reality that actually effected something.[5] One could not be too careful in the face of the law[6] (especially as it had come to be understood by the 560s). The legal act and procedure were intimately bound up with their social context.[7] As a practicing member of the Egyptian bureaucratic elite,[8] Dioscorus consciously tried to do full justice (in every sense) to the problems that came his way. His travels, as well as his family background of philosophical learning,[9] high status, and involvement with monasticism, added to his competence as a professional.[10] In the Greek and Coptic documents that compose the body of his work, we can

[4] See H. Zilliacus, Zur Abundanz d.spätgriech. Gebrauchssprache (Helsinki 1967), esp. 20–25 (cf. 10), 62–68. R. MacMullen, "Roman bureaucratese," Traditio 18 (1962) 364–378, is overfull of unhelpful jargon. We are in the presence of matters other than the "leere Floskeln" beloved of classical critics (e.g., W. Spiegelberg and F. Rabel, "Ein koptischer Vertrag," Abh. Göttingen, phil.-hist. Kl., n.F. 16.3 [1916–17] 75–84). Cf. L. S. B. MacCoull, "Child donations and child saints in Coptic Egypt," EEQ 13 (1979) 409.

[5] Cf. Marc Bloch, The historian's craft (New York 1953) 168: "the vocabulary of documents is, in its way, only another form of evidence. . . . Each significant term, each characteristic turn of style becomes a true component of knowledge—but not until it has been placed in its context, related to the usage of the epoch, of the society or of the author." Also A. E. Samuel, From Athens to Alexandria (Louvain 1983) 9: "Because economic behavior is so indicative of over-all social attitudes, we can use the evidence of economic theory and activity to reveal those tacit assumptions about man and society which underlay the construction of social and cultural institutions." Even the act of making up a valid transaction reveals a world. A document was a dispositive thing: H.-J. Wolff, Das Recht der griechischen Papyri Ägyptens (Hdbuch d.Altertumswiss. 10.5.2) (Munich 1978) 141–144.

[6] Cf. L. S. B. MacCoull, "Child donations," pp. 409–415.

[7] R. V. Colman, "Reason and unreason in early medieval law," J.Interdisc.Hist. 4 (1974) 571–591, esp. 571–579—a brilliant study.

[8] See T. F. Carney, Bureaucracy in traditional society: Romano-Byzantine bureaucracies viewed from within (Lawrence, Kansas, 1971) II.117–122, 176–187 (cf. 78–83). Unlike John Lydus, Dioscorus does not voice open disillusionment with his job or with "the system."

[9] It is Dioscorus's papers that have preserved the Horapollon letters: J. Maspero, "Horapollon et la fin du paganisme égyptien," BIFAO 11 (1914) 163–195.

[10] Cf. F. S. Pedersen, "On professional qualifications for public posts in late antiquity," Class.etMed. 31 (1975) 161–213. As one might expect, though, breeding and connections counted. Dioscorus had both status as local gentry and educational attainment.

see how the functions of recording and of decision became fused.[11] In this process lay the seeds of the future of Coptic law.[12]

The documentary production of Dioscorus offers the penultimate stage of development—before the evolution that took place after the Arab conquest—in which to observe the perennial interpenetration of Reichsrecht and Volksrecht[13] in a late Roman province. And more: the polarities observable in the praxis of Aphrodito and Antinoë are not only those of the imperial legislation of Old and New Rome[14] vis-à-vis the inherited custom of the country.[15] The tensions also appear as an interaction between two modes of perceiving the role of the human intellect, one profoundly positive and one profoundly negative—an ambiguity that has continued to affect Coptic culture to the present day. The actions and transactions of Dioscorus and his fellow citizens show forth their definitions of truth, their mechanisms for finding out truth, and their underlying assumptions about how truth operates in human life.[16]

The style, in Greek and Coptic, in which these transactions are couched reflects the network of interlocking responsibilities[17] so characteristic of the Late Antique city (particularly in Egypt with its uniquely inescapable landscape).[18] Dioscorus's personal documentary style, as seen in its own time,[19] bears the imprint of several major influences. Besides the technical language he had learned and used as a working tool,[20] he every-

[11] Cf. B. Stock, The implications of literacy (Princeton 1983) 41–42; cf. 58–59.

[12] The position taken by A. A. Schiller in "The courts are no more," Studi E. Volterra (Milan 1969) 469–502, is rather extreme: he asserts that the non-Chalcedonian Copts' loathing for the "official" justice of the Chalcedonian government was so intense as to bring about the development of a whole system of private, personal, arbitration-based justice for the community. The actual situation surely did not draw such hard-and-fast lines before the conquest. (Afterwards became a different matter.) Cf. Colman, "Reason and unreason," pp. 573–575.

[13] So formulated after the title of Mitteis's classic work, Reichsrecht und Volksrecht in den östlichen Provinzen d. röm. Kaiserreich (Leipzig 1891).

[14] Cf. A. A. Schiller, "The fate of imperial legislation in late Byzantine Egypt," in Legal thought in the USA under contemporary pressures, ed. J. N. Hazard and W. J. Wagner (Brussels 1970) 41–60.

[15] For an earlier period, cf. E. Seidl, Rechtsgeschichte Ägyptens als römischer Provinz (Sankt Augustin 1973).

[16] The divisions in Late Antique Egyptian society are usually discussed as being those of center vs. periphery, of "classical" vs. "anticlassical" elements, along linguistic and confessional lines. (Cf. Chapter 3, n. 58.) These analyses do not work any more than does a simple Reichsrecht/Volksrecht methodology.

[17] Cf. Colman, "Reason and unreason," 573–575.

[18] P. R. L. Brown, The making of late antiquity (Cambridge, Mass. 1978) 3–4, 81–85.

[19] Zilliacus, Abundanz, pp. 6–8, 43–47, for examples.

[20] Ibid., 63.

where echoes the Scriptures and the liturgy. His Greek style appears modeled to a perceptible extent on the rhetoric of Cyril of Alexandria,[21] and his vocabulary shares elements with the philosophical usage of John Philoponus.[22] Of course, beneath the surface of his Greek lies Coptic syntax: the parataxis, the effective asyndeton, the aesthetic implied in an analytic language of particular verbal systems and word orders.[23] His Coptic style itself combines businesslike straightforwardness, vividness in narration, and imaginative embellishment. The tendencies visible in Dioscorus's prose can be seen taken further in such sixth- to seventh-century pieces as the Greek ecclesiastical letters in P.Grenf. II 112[24] and BKT VI 10677, and the Coptic synodal letter of Patriarch Damian in Epiphanius II 149–152. (Recognizable stylistic elements are still alive nearly three hundred years later, in the documents of the Hermopolite monastery of Apa Apollo.[25] ) Dioscorus's documentary work stands nearly midway in the history of that Late Antique Geschäftsprosa, which was itself an art form.

Dioscorus was a bilingual man functioning in a bilingual society. As Roger Bagnall has stated, "the Coptic papyri of the archive need editing, for without them any synthetic study of the world of Dioskoros would be a

[21] See A. Vaccari, "La grecità di S. Cirillo d'Alessandria," Studi P. Ubaldi (Milan 1937) 27–40; cf. L. R. Wickham, Cyril of Alexandria: select letters (Oxford 1983) xiv, for a decidedly negative opinion of Cyril's style. See also C. Datema, "Classical quotations in the works of Cyril of Alexandria," Studia Patristica 17 (Oxford 1982) 422–425.

[23] Cf. I. M. Diakonoff, Hamito-Semitic languages (Moscow 1965) 38–41. Coptic does not form certain kinds of compounds, and places weight in the noun more than the verb; this explains much. Zilliacus, Abundanz, p. 10, is surely wrong in not seeing many signs of Coptic interference in sixth-century Greek documentary style (from Egypt). (Cf. F. T. Gignac, Grammar of the Greek papyri of the Roman and Byzantine periods I [Milan 1976] 46–48.) Dioscorus's prose, however, is not to be dismissed as the bumblings of a babu who had never properly learned to think in or to employ the language of the high culture (cf. H. I. Bell, "An Egyptian village in the time of Justinian," JHS 64 [1944] 27–31, one of the milder condemnations of his style). Its charm lies in sharply rendered perceptions and unexpectedly happy juxtapositions. (For this sort of poikilia and variation as Late Antique stylistic traits, cf. the remarks of M. Roberts, "The Mosella of Ausonius," TAPA 114 [1984] 344 with nn. 8–10, 353.)

[24] Now redated to A.D. 557 by S. Bernardinello, "Nuove prospettive sulla cronologia del Pap.Grenf. II 112," Scriptorium 34 (1980) 239–240; cf. "Cronologia della maiuscola greca di tipo alessandrino," Scriptorium 32 (1978) 251–255.

[25] See M. Krause, "Das Apa-Apollon-Kloster zu Bawit" (Diss., Leipzig 1953), now finally to appear in printed form. The MSS are British Library Or. 6202, 6203, 6204, 6206; their oath formulas can be integrated with those collected by K. A. Worp, "Byzantine imperial titulature in the Greek documentary papyri: the oath formulas," ZPE 45 (1982) 199–223. My initial study of them will appear in BASP 24.

farce."[26] Unfortunately, our knowledge of the Coptic portion of Dioscorus's papers is not yet complete;[27] and, given conditions in Egypt, substantive results cannot be expected in any foreseeable future. In searching the Coptic documentary papyri in collections known to contain Greek items by Dioscorus, I have not found anything either in his hand or mentioning his name. Did the process by which the Dioscorus archive came to be scattered among numerous libraries affect only the Greek papyri? In any case, such Coptic documents as I have found to exist will be fully incorporated into the present treatment.

What little information we have of the circumstances of the second Kom Ishgaw find in 1905 or the clandestine diggings in 1937 and 1938, followed by over forty years of total lack of interest, does not even now enable the researcher to track down Dioscorus's Coptic pieces. Three boxes of Coptic material from the site were given by Lefebvre to the Cairo Museum;[28] however, because Jean Maspero could not read Coptic, they were put aside, and the fate of their contents is still unknown. Those sixth-century Coptic Aphrodito documents that have come to rest in the Vatican library, having been removed to safety at the time of the transfer of material to the then-new Coptic Museum, are not in Dioscorus's hand. We may assume, however, that he had kept them among his working papers. Perhaps they were inherited from his father, although the Vatican papyri contain few clues as to dating. Numbers 5 and 1 probably come from 535/6 and 536/7,[29] during Apollos's floruit and Dioscorus's youth. Their phraseology displays the characteristic fullness of Greek usage and legal idiom[30] we are later to find noticeable in Dioscorus's own work at the Aphrodito and Antinoë chanceries. But, apart from the normal "squirearchical" documentation (in Greek) outlined in Chapter 1, we do not hear Dioscorus's own voice in either language until 547/8, when he had become the heir to his estates and assumed the role of spokesman for his community.

The earliest preserved monument, the first extended piece of Dios-

[26] R. Bagnall, review of I papiri Vaticani di Aphrodito by R. Pintaudi, BASP 18 (1981) 177.

[27] See my overview, The Coptic archive of Dioscorus of Aphrodito," Cd'E 56 (1981) 185–193. Further pieces, it seems, lurk in the Cairo Museum among the material numbered S.R. 3733; I am still in process of preparing texts. Two are in the Ismaila Museum.

[28] P.Cair.Masp. III, preface; L. S. B. MacCoull, "Additions to the prosopography of Aphrodito from the Coptic documents," BSAC 25 (1983) 91.

[29] See L. Papini, Notes on the formulary of some Coptic documentary papyri from Middle Egypt," BSAC 25 (1983) 83–89, and "Annotazioni sul formulario giuridico di documenti copti del VI secolo," Atti XVII congr.intl.papirol. (Naples 1984) 767–776.

[30] L. Papini, ibid. (utraque ).

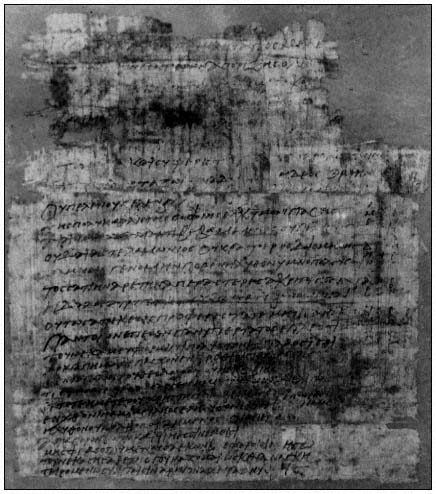

corus's prose writing, is the petition to the empress Theodora of 547/8, P.Cair.Masp. II 67283, written just at the end of the empress's life. This production dates from the eve of Dioscorus's journey to the capital, before he began (as far as we know) the composition of poetry. In this, his first work, we can see some of the elements that went into the formation of his mind: familiarity with his family's papers, reminiscences (perhaps) of Apollos's trip to Constantinople, knowledge of the workings of the chancery and, of course, the classics and the scriptures. In it we can already see many of the elements that are to be characteristic of his developed prose style: ornamental and emotionally expressive nouns, declamatory flourishes, biblical and classical reminiscences effectively interwoven. It builds in a crescendo from a simple opening identifying the petition's author and recipient to an elaborate rhetorical close that depicts the empress's healing hand protecting the land from evil.

The opening of the text is addressed by the Aphroditans to a deacon, Victor, and a body of officials (with the title

are punished, dwellings are made splendid, and the possessions of your native people are kept safe from being undermined or razed" (presumably by tax collectors illegally looking for that last keration).

In this splendid rhetorical closing, with the image of the healing hand adorning Egyptian civic life and enabling the good life to be led (an image resembling Hestia Polyolbos), Dioscorus has given, at the beginning of his career, a classic statement of Late Roman civic values. Could Apollos have seen Theodora, in 541, and come home full of tales? Perhaps. In any case, Dioscorus's striking image of the healing hand and the civic benefits it enacts both vividly recalls visual depictions of the Hand of God in Late Antique art and boldly states an ideal. The ideal was one of simultaneous visible splendor in the city's material structure and shining justice for its inhabitants. However imperfectly realized, still the ideal was there, and it is a merit of Coptic society to have clothed it in such all-enfolding and luminous imagery.

By the last years of the reign of Justinian, financial and social tensions at Aphrodito were an old story, and one familiar to the former young squire who had been to the capital of the empire and was no stranger to responsibility. The events that led to and prompted Dioscorus's career move from Aphrodito to the ducal court at Antinoë have already been sketched.[31] From 564 (probably) we have, in Coptic, the record of an arbitration[32] in a case at law that illustrates the sort of last-straw frustrations he had to endure in the business of estate management. Some eighteen months later he will have transferred to the Antinoë chancery, now jurist and poet rather than homebound landlord.

P.Berol. 11349,[33] drafted by another notary but with a small annotation in Dioscorus's hand, begins with the technical operative verb of arbitration,

In the first part of the narrative, Dioscorus speaks in the first person. He contends that Joseph, his tenant, has so imperfectly worked the land he has leased from Dioscorus that the field has not yielded its quota of tax

[31] Cf. MacCoull, "Dioscorus and the dukes," BS/EB 1987.

[32] Noticed by A. A. Schiller in his introduction to the second edition of KRU (Leipzig 1971).

[33] I am grateful to Dr. G. Poethke of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (DDR) for photographs of the papyrus. It is not, except for an annotation, in Dioscorus's own hand, but it yields a coherent text.

(demosion and phoros), and that therefore Dioscorus is unjustly stranded with the tax liability. At harvest time (Pachons and Payni), Dioscorus himself secretly checked the accounting and was so shocked at the outcome that he lodged a complaint against Joseph; thus, if the arbiter finds Joseph guilty, it is he who will (rightly) have to pay the tax. It seems that Joseph has also compounded his negligence by allowing animals with their herders to trespass across the field,[34] thus making the land even less able to yield its needed quota. Dioscorus concludes his accusation by alleging that Joseph has even acted in collusion with the (unnamed) boethos to cover up what he has done. Next, the arbiter records Joseph's flat denial of any negligence; then, switching into the first person, he states that he attributes the wrongdoing to Joseph the tenant, not to the owner who has brought the complaint, but that Joseph may not have known that his actions constituted negligence.

Unfortunately, no absolute date has been preserved in this document; however, the thirteenth indiction mentioned in line 37 would suggest the year 564, when Dioscorus was still at Aphrodito and being bedeviled by the Menas affair (see later discussion), rather than 579, when he was back home in what seem to have been comparatively peaceful days. At the end of the document it is recorded that Dioscorus takes his oath on the amounts of money involved and that, for his part, Joseph goes surety for the amount, presumably, of the tax. The end of the papyrus is lost, so we cannot know what judgment the arbiter formally pronounced.

Even in a bare narration like this, a plea at law that aims to tell simply the facts, we can discern features of Dioscorian style, this time in Coptic (and being filtered through the offices of a notary). "He made my portion into rust and blight," he says; he paints a picture of chicanery and deception undermining the fundamental ties of a society in which ancient custom (

During 565, the last year of Justinian's reign, Dioscorus pursued his career of land entrepreneurship and estate management, framing documents of sale in normal legal style as he had done in the previous fifteen years and more (e.g., P.Cair.Masp. II 67170–67171 and P.Lond. V 1686, recording his dealings with the Panopolite monastery of Zminos and refer-

[34] Compare J. G. Keenan, "Village shepherds and social tension in Byzantine Egypt," YCS 28 (1985) 245–259.

ring to his troubles with the Phthla shepherds). But it is when he is newly arrived in Antinoë the next year, filled with indignation at the behavior of Menas, the encroaching pagarch of Antaeopolis, that we see his next documentary productions in the high style.

By the autumn of 566[35] Dioscorus had moved to Antinoë. Personally and professionally it was a step up. As a nomikos probably on the ducal taxis, he would command the respect and the fees that were owed to a learned jurist with his experience; as resident in the first city of the Thebaid, he had the opportunity to increase his skill as a man of letters; and as a representative of his heritage, he would become still more deeply involved in the defense of Aphrodito against the perennial inroads of the Antaeopolitan pagarchy. Aphrodito's rights and his responsibility for them had brought him to the capital of the empire, and they would continue to claim him here at the seat of the duke. The wicked pagarch comes to be the central figure of his rhetoric—a plague out of the Old Testament, a raiding barbarian, almost an antichrist. (To what extent an annual tax requirement based on the pagarchy, rather than autopragia, was felt by contemporaries to be an irremediable flaw in the system is unknown.[36] ) In his first year at Antinoë, Dioscorus composed two of his grandest pieces of prose centering round this theme, P.Lond. V 1677 and P.Cair.Masp. I 67002. The didaskalia to Theodora has become grand-opera eloquence. Right at the beginning of his Antinoë period, Dioscorus pulls out all the stops.

P.Lond. V 1677, a petition to a magister, is a document written out of burning personal outrage. The affair of Menas, pagarch of Antaeopolis, is the very last straw that has driven Dioscorus to become a suppliant (and job seeker, as we have seen from his early poetry) at the ducal court. Menas has used his office in collusion with the unruly shepherds of Phthla—we have not heard the last of them—to damage Dioscorus's family holdings. To expose this wrong, he brings to bear every rhetorical figure and liturgical and scriptural echo he can orchestrate.

Dioscorus begins with a dative, in cheirographon style: "To my truly good master and philanthropic benefactor (

[35] P.Cair.Masp. II 67161; Bell's introduction to P.Lond. V 1674, p. 56. On the social and cultural attractions of the ducal capital, see MacCoull, "Dioscorus and the dukes."

[36] A question not raised in W. Liebeschuetz, "The origin of the office of the pagarch," BZ 66 (1973) 38–46.

sion], and also the Dorotheos of his poetry?) Next, his captatio benevolentiae is a decorative and elaborate period that centers on the word

In this state, "worse than the aftermath of a barbarian raid" (a topos Dioscorus will use several times), what can be done? Man is left

Dioscorus's word order and vocabulary reflect his deepest values. His most complex period here begins with

Close reading of a text like this rewards the historian with a wealth of meaning. When the documents of this period have been read at all, other than purely as sources of fact, they have been held up as laughable. How could these writers, using ten synonyms where a bare word would do,

[37] Keenan, "Village shepherds," 245–259.

inflate their petty troubles to sound like the end of the world? How could they have turned the skills of the free orator to such base ends? But this mode of criticism has been found wanting. We must listen from the inside. Dioscorus's feelings as a member of his society emerge nakedly from the texts he writes for specific cases. Egyptians especially, rooted in their landscape, were painfully aware of how fragile were the boundaries marking off their lives: green from dry, nurturing from barren and threatening. They also knew how shaky could be the fences between themselves and barbarism, physical and cultural. And they were clear about the priorities within their own world. To see justice and order and the saving splendor of hierarchy manifest in one human official[38] (addressed, too, by a resoundingly abstract title) was to feel that the earth was still under their feet. At his conclusion, Dioscorus repeats the concepts of soteria and diamone: above and below, a sureness in things.

In the small world of this one petition, Dioscorus is treating two of the most serious problems of his time: illegal tax encroachment by pagarchs, and the transfer of sown land to shepherds. He invokes both theological and civic values (reading

At the end of the indiction year 566/7, Dioscorus directly addressed the Duke of the Thebaid himself, Athanasius, both on his own behalf and in concert with the property owners (syntelestai) of Aphrodito. His second petition recounting the Menas affair, P.Cair.Masp. I 67002, also begins by calling itself a

"All justice and right dealing," he begins, "ever brighten the progress of your exalted authority, which is preeminently best; and we have long since received it [i.e., your authority] the way those in the netherworld once waited for the parousia of Christ, the eternal God." This striking figure was noticed even by Bell.[39] We have already seen how justice is a central theme in Dioscorus's poetry. Here he couples

[38] Compare the vision of the policeman's uplifted hand in Charles Williams's The greater trumps (London: Faber and Faber, 1954).

[39] Bell, "An Egyptian village,' p. 33.

Plotinian word for emanations. The coming of the duke is a kind of emanation of Justice itself. In the previous document, Dioscorus began with sound; here he begins with light, with the beams of justice lighting up the duke's advent the way Christ's Harrowing of Hell struck a beam of light upon the dazzled shades. The balanced endings of his clauses, with their metrical value as clausulae, meaningfully play one against the other; exousia, parousia. It is a beautiful picture (and one not found, it seems, in the iconography of the Coptic visual arts)—that of all the patriarchs and prophets and human forebears, and even the "good pagans," having their longings fulfilled at last. Just so are the Aphroditans' longings for justice to be fulfilled.

"For," he goes on, "after God, our Lord and Savior, the true helper and benefactor who loves humankind, we hold your Highness with all hope of salvation, who are everywhere praised and proclaimed and reported to us in all necessities, that you will extend a way out of our wrongs and deliver us from the unspeakable things, too many for this papyrus to contain, which have happened at the hands of Menas." Dioscorus constructs a doubly balanced sentence: first he pairs God and the duke, and then, branching off, he uses a pair of verbs to describe how the latter will

In the rest of this petition, Dioscorus's rhetorical style takes a scriptural turn. He describes his young children as "hardly knowing their right hand from their left" (I.12), which Gelzer noted as an echo of the last verse of Jonah.[40] The dishonest Menas, classically

[40] Archiv 5 (1913) 189 (footnoted by Maspero in his edition).

After a narrative of the pagarch's wrongs—imprisonments, confiscations—Dioscorus reminds the duke that the Aphroditans are his men "and men of the imperial house" (II.14–15). He returns to the opening theme: "And it is for us a work of prayer [a Copticism:

We have not heard the last of this pagarch's misdeeds. In another crescendo, Dioscorus recounts how Menas interferes (counterproductively, one would think) with the irrigation system, the lifeline of the Egyptian countryside, for his own short-term ends. After the responsible syntelestai had strengthened the canal at the time of the Nile flood, "for access and irrigation" (a sort of cross between a hendiadys and a zeugma), the pagarch impeded their work, acting

In the last twenty lines, Dioscorus once again describes the fury[42] of Menas and the shepherds, even to the pitch of hyperbole: "human blood ran like water over the land," he says. (In local mythology, a few stones thrown can be a massacre.) At the end, he recalls again the duke's parousia: "We clasp the knees of your Highness, whom we behold like those who see God" (III.21). The pagarch is "like a ramping and a roaring lion" (

[41] The houses of women religious at Aphrodito/Antaeopolis are listed in the survey of P. Barison, "Ricerche sui monasteri dell' Egitto bizantino ed arabo," Aegyptus 18 (1938) 121–122, 98. (Compare below, comments on P.Lond. V 1674.)

[42] Possibly also a scriptural echo; there are overtones of the descriptions of fierce destroyers in Isaiah and Jeremiah.

At about the same time as he wrote the previous document (566/7), Dioscorus was retained by the Antinoite monastery of the Apostles at Pharoou to compose another petition to the same duke (P.Cair.Masp. I 67003). While at Antinoë, he was to have more than one transaction with this religious house, comparatively distant though it was (see the comments on P.Cair.Masp. II 67176+P.Alex.inv. 689). Its full title was that of the "Christ-bearing Apostles." Could it have been the same place as the

In fact, Dioscorus had the closest possible family connection with this monastery, for it had been founded by his father, Apollos. We know that Apollos had entered the monastic life, although whether he joined before or after his journey to Constantinople is uncertain.[44] He subsequently spent the rest of his life in the monastery in the Antaeopolite nome that he founded, named Apa Apollos after himself (with the dedication to the Christ-bearing Apostles [P.Cair.Masp. I 67096, 573/4]), and for which he named Dioscorus curator. Apollos was dead by 546/7, twenty years before the present Greek document was written. But the identification is assured by the conclusion of P.Alex.inv. 689, written in Coptic in Dioscorus's hand and dated 28 October 569. It is addressed "to the pious superior of the monastery of Pharoou and its whole village, from Dioscorus, the most humble son of Apa Apollo of Pharoou" (lines 26–29). We can thus conclude that the house of the Christ-bearing Apostles, of Pharoou and that of Apa Apollos of the Christ-bearing Apostles were one and the same.