Preferred Citation: Goodman, Bryna. Native Place, City, and Nation: Regional Networks and Identities in Shanghai, 1853-1937. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0m3nb066/

| Native Place, City, and NationRegional Networks and Identities in Shanghai, 1853-1937Bryna GoodmanUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1995 The Regents of the University of California |

for my parents

Preferred Citation: Goodman, Bryna. Native Place, City, and Nation: Regional Networks and Identities in Shanghai, 1853-1937. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0m3nb066/

for my parents

Acknowledgments

My greatest intellectual debt is to my advisors at Stanford University, Harold Kahn and Lyman Van Slyke, who guided me through a dissertation on this topic and whose careful readings and insightful criticisms challenged and inspired me over the course of many revisions. They created a rare atmosphere of intellectual collaboration at Stanford and set high standards for teaching, scholarship and integrity.

I would also like to thank Carol Benedict, Prasenjit Duara, Joseph Esherick, Christian Henriot, Wendy Larson and two anonymous readers for the press, each of whom provided detailed, thoughtful and provocative readings of my full manuscript, substantially enriching its quality. Susan Mann helped guide my initial formulation of my topic and provided insightful suggestions at various points along the way. During a postdoctoral year at the University of California at Berkeley I benefited from the presence of Frederic Wakeman and Yeh Wen-hsin, who took time to read and comment on my work and who challenged me with the breadth of their own work on Shanghai and related topics. Cynthia Brokaw, Andrew Char, Paul Katz, William Rowe and Ernst Schwintzer each read portions of the manuscript and provided insightful comments and suggestions. I am grateful for the generosity of each of these readers, with whose help I have avoided some of the pitfalls of earlier versions.

My initial research in China was greatly facilitated by my Fudan advisors, Professors Huang Meizhen and Yang Liqiang. They also opened their homes to me and introduced me to the special foods of their native

places, in Fujian and Guangdong provinces. Zhang Jishun and Zhu Hong, of the Center for Research on Shanghai, together with Huang Meizhen, smoothed arrangements during a subsequent research trip in 1991, as did the staff of the Foreign Affairs Office at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. I would also like to thank the staffs of the Shanghai Municipal Archives, the Shanghai Municipal Library and the Shanghai Museum of History. Fan I-chun, Yao Ping and Zhao Xiaojian spent long hours helping me interpret elusive documents. Fu Po-shek, Hamashita Takeshi, Luo Suwen, Ted Huters and Jeff Wasserstrom alerted me to sources of which I had been unaware. Dorothy Ko kindly hosted me and helped to orient me during a research trip to Tokyo. Colleagues in the History Department of the University of Oregon provided encouragement and made me more vigilant in my choice of words.

Tom Gold and the staff of the Center for Chinese Studies provided a stimulating environment for writing during my 1990-91 postdoctoral fellowship. I would like to thank the organizers of the 1988 International Symposium on Shanghai History, as well as the Center for Research on Shanghai, for two subsequent conference invitations which provided a forum for discussing my findings with colleagues in the People's Republic of China. The Committee on Scholarly Communication with the PRC (CSCPRC) and the University of Oregon provided funding to attend these conferences. I am also indebted to Christian Henriot and the staff of the Institut d'Asie Orientale in Lyon for their many kindnesses in hosting me during fall 1993 and providing a conducive intellectual climate for my final book revisions.

My research in China was made possible through a CSCPRC grant, funded by the U.S. Department of Education. I would like also to acknowledge funding from the Oregon Humanities Council and a Reed College Vollum Award, both of which permitted me to spend time on research and writing. I am grateful to Sheila Levine at the University of California Press for her support and interest in the manuscript, to Laura Driussi for her patient editorial assistance and to Sarah K. Myers for her meticulous copyediting. My friends Jeff and Rosemarie Ostler provided much-needed help with my manuscript preparation at the last minute. Finally, I would like to thank my husband, Peter Edberg, for editorial and computer assistance and many other contributions which cannot all be detailed here.

Chapter One

Introduction

The Moral Excellence of Loving the Group

Shanghai is a hybrid place which mixes together people from all over China. The numbers of outsiders surpass those of natives. Accordingly, people from each locality establish native-place associations [huiguan] to maintain their connections with each other. The Ningbo people are the most numerous, and they have established the Siming Gongsuo. The Guangdong people are second in number, and they have established the Guang-Zhao burial ground and the Chao-Hui Huiguan. In addition to these, the people from Hunan, Hubei, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Zhejiang, Shaoxing, Wuxi, Huizhou, Jiangning, Jinhua, Jiangsu, Jiangxi and other places have each established huiguan. As for people from localities which have not established huiguan, they have meetings of fellow-provincials every month. This is for the purpose of uniting native place sentiment.... Among the people of our country, there are none who do not love to combine in groups. Thus fellow-provincials all establish huiguan. And people of the same trade all establish gongsuo .... From this it is possible to know that Chinese people have the moral excellence of loving the group.

—Li Weiqing, Shanghai xiangtuzhi

(Shanghai local gazetteer), 1907

You remarked to me that the Chinese, being actuated by a common feeling, none of them would be willing to come forward [as witness against a fellow Chinese] .... You entirely ignore the circumstance that the Chinese people have never been influenced by any common feeling. Further, in the [street], people from every part of China are mixed together, owing to which, no one cares for the sorrows and ills of another [emphasis added].

—Daotai Wu Xu to British Consul (Great Britain, Public Record Office, FO 228.274, 1859)

This study explores social practices and rituals related to xxiangyi , also called xiangqing and ziyi , Chinese expressions for the sentiment that binds people from the same native place. This sentiment, and the social institutions which expressed it, profoundly shaped the nature and development of modern Chinese urban society. The two quotations which begin this chapter suggest twin aspects of urban social organization and behavior that correspond to native-place sentiment. The account in the 1907 Shanghai gazetteer describes organization by native place as a necessary, natural, specifically Chinese and indeed "morally excellent" response to the dangers posed by urban admixture and anomie. Daotai Intendment Wu XU's description of the city under his jurisdiction indicates a possible drawback to the "moral excellence" of native-place sentiment, suggesting that, when individuals from different native-place groups mixed together on a city street, they felt no common identity as Chinese.[1] The chapters which follow address these themes—the prominence of native-place sentiment and organization in Chinese cities and the influence of such ideas and social formations on city life, social order and urban and national identity.

The study is based on Shanghai and covers nearly a century, from the opening of the city to foreign trade in 1843 to the establishment of Guomindang dominance in the Nanjing decade (1927-37). Throughout this period immigrant groups from other areas of China dominated Shanghai's rapidly expanding urban population, which more than quadrupled in the nineteenth century (see Map 1). Shanghai's population in 1800 was between one-quarter and one-third million. By 1910 it was 1.3 million. It doubled again by 1927, to 2.6 million. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, immigrants comprised at least 75 percent of the total figure. Some of these immigrants came to Shanghai to explore economic opportunities; others came in waves to flee war and famine in their native place.

Combining forces to meet the imperatives of their new urban surroundings, these immigrants formed native-place associations, huiguan and tongxianghui . Such associations and the sentiments which engendered them were formative elements of Shanghai's urban environment

[1] Daotai Wu's comment here is somewhat disingenuous, for he was attempting to deflect British concerns that the Chinese residents of the settlement could mobilize effectively together in anti-British behavior. In this instance, the Daotai clearly found it useful to suggest that the logic of local native-place identity impeded national identity as Chinese.

Map 1.

Major provinces of China supplying immigrants to Shanghai

throughout the late Qing and early Republican periods. Social, economic and political organization along lines of regional identity shaped the development of the city.

Such prominence and continuity of native-place sentiment and organization was possible because of the flexibility, adaptability and utility of native-place ideas to forces of economic, social and political change in the city. The numbers of associations and their shifting forms and practices demonstrate these traits of persistence and change, familiarity and changing meaning, which make native-place sentiment a crucial arena for understanding the texture of modern change in the city.

Shanghai, though notable in this regard, was certainly not unique. Immigrant Chinese population groups characterized and even dominated nearly all expanding commercial areas in China during this pe-

riod.[2] Immigration itself does not distinguish Chinese cities from their European and American counterparts.[3] Nonetheless, the degree of cultivation and elaboration of native-place identities and native-place organizations, and the power and duration of these sentiments and institutions, are peculiar to Chinese cities.

The Idea of Native Place

Identity and Connection with the Native Place . The Chinese language contains a variety of expressions for the concept of native place. Terms such as jiguan, sangzi, laojia, yuanji , and guxiang , which abound in Chinese records and literature, translate variously as birthplace, hometown, native place and ancestral home. The concept of native place was a critical component of personal identity in traditional China, and geographic origin was generally the first matter of inquiry among strangers, the first characteristic recorded about a person (after name and pseudonyms), and the first fact to be ascertained regarding individuals coming before the law.[4]

For immigrants who sought a living in Shanghai, native-place identity expressed both spiritual linkage to the place where their ancestors

[2] See Chang Peng, "Distribution of Provincial Merchant Groups in China" (Ph.D. diss., University of Washington, 1958); Mark Elvin and G. William Skinner, eds., The Chinese City between Two Worlds (Stanford, Calif., 1974); G. W. Skinner, ed., The City in Late Imperial China (Stanford, Calif., 1977); G. W. Skinner, "Mobility Strategies in Late Imperial China: A Regional Systems Analysis," in Regional Analysis , ed. Carol A. Smith (New York, 1976), vol. 1, 327-64; William Rowe, Hankow: Commerce and Society in a Chinese City, 1796-1889 (Stanford, Calif., 1984). Nonetheless, immigration was particularly dramatic in Shanghai because it was a relatively small city prior to 1840 and because it experienced extremely rapid growth after 1860.

[3] Recent studies of urban labor and social movements in the United States have stressed the importance of immigration and ethnicity. See, for example, Joseph Barton, Peasants and Strangers: Italians, Rumanians and Slovaks in an American City, 1890-1950 (Cambridge, Mass., 1975); Eric L. Hirsch, Urban Revolt: Ethnic Politics in the Nineteenth-Century Chicago Labor Movement (Berkeley, Calif., 1990); Richard B. Stott, Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity and Youth in Antebellum New York City (Ithaca, N.Y., 1990); Judith Smith, Family Connections: A History of Italian and Jewish Immigrant Lives in Providence, Rhode Island, 1900-1940 (Albany, N.Y., 1985); John Bodnar, Workers' World: Kinship, Community and Protest in an Industrial Society, 1900-1940 (Baltimore, Md., 1982). For a study of the cultural meaning of local identity at both the regional and the national levels in Germany, see Celia Applegate, A Nation of Provincials: The German Idea of Heimat (Berkeley, Calif., 1990).

[4] See G. William Skinner, "Introduction: Urban Social Structure in Ch'ing China," in Skinner, The City in Late Imperial China , 538-48; Skinner, "Mobility Strategics"; Ho Ping-ti, Zhongguo huiguan shilun (On the history of Landsmannschaften in China) (Taipei, 1966); Rowe, Hankow: Commerce and Society , 213-51. Numerous popular expressions describe attachment to the native place, such as hun gui gutu (the soul returns to the native place); rong gui guxiang (to retire in glory to one's native place); luoye gui gen (falling leaves return to the roots); jiu shi guxiangde hao; yue shi guxiangde yuan (wine is better from one's native place; the moon is rounder in the native place). The term youzi refers not just to a wanderer but to one who is separated from his native place. Separation from one's native place is also a prominent theme in classical Chinese poetry. Meng Jiao's poem, "Youzi Yin" (Sigh of a wanderer), is understood to express the sojourning condition and the ties binding the sojourner to his native place:

The thread in the hand of the loving mother

Is woven into the sojourning son's garments.

Before he leaves she makes her stitches double

Fearing he will be long in returning.

However deep his gratitude, how can he ever

Repay a debt that will bind him always?

Adapted from Liu Shih Shun, ed. and trans.,

One Hundred and One Chinese Poems, with

English Translations and Preface (Hong

Kong, 1967), 72-73.

were buried and living ties to family members and community. These ties were most frequently economic as well as sentimental, for local communities assisted and sponsored individual sojourners, viewing them as economic investments for the community. Both religious and economic practices depended on the assumption that the traveler's identity would not change along with his place of residence, that changes of residence were only temporary, and the traveler would return to his native place regularly on ritual occasions, and finally, upon his death.[5] These beliefs were not altered by a residence that lasted several generations. Children of immigrants who were born in places of "temporary residence" similarly did not acquire a new native-place identity but instead inherited the native place of their fathers or grandfathers. In practice, insofar as possible, immigrants returned home for marriage, mourning, retirement and burial. Moreover, throughout their period away, they sent money back to their native place, expressing their family and geographic loyalties in flows of remittance.

Because of these patterns of belief and practice, urban immigration

[5] See Skinner, "Introduction," 538. This normative viewpoint was expressed in terms of male sojourners. Men dominated sojourning communities in late-nineteenth-century Shanghai. Sojourning merchants at the head of large families kept most, if not all, of their family members in their native place. While women sojourners did exist, notably as prostitutes in nineteenth-century Shanghai and as prostitutes and factory workers in the twentieth century, the imperatives for linkage to their native place were weaker, owing to the fact that women married out of their families and were not buried in their natal villages and, moreover, to women's customary exclusion from public activity.

in China was perceived as sojourning and did not involve a fundamental change of identity. Immigrant communities in Shanghai referred to themselves as "Ningbo sojourners in Shanghai" (lü Hu Ningboren ) or "Guangdong lodgers in Shanghai" (yü Hu Guangdongren ). These labels stress the fundamental nature of native-place identity, even as they recognize the sojourners' location in Shanghai. The labels also suggest the hybrid nature of sojourners' identities: while linked to both Shanghai and their native places, once sojourning, they were not purely of their native place, nor could they simply adopt their locational identity (Shanghai).

For individual sojourners the maintenance of elaborate ties with their native place was an ideal which could only be fully achieved by the wealthy.[6] Nonetheless, all but the most impoverished sojourners tried regularly to visit their homes, even when their villages were distant. This included members of secret societies and criminal gangs. Reporting on the January plunder of a pawnshop by a Guangdong gang as well as attacks on wealthy households in the Shanghai suburb of Gaoqiao (on the east bank of the Huangpu River), the North China Herald of January 23, 1858, noted that this was the season when Cantonese were about to return to their native province for the Chinese new year, "the Scoundrels thereby laying in a stock of clothing and money for their new year dissipations and absconding with impunity."

It was most critical for sojourners to return to their native place for burial. Chinese death ritual required that the dead be buried in ancestral soil and that tablets for the deceased be installed in the family altar, so that their spirits could enjoy the comforts of home and the sacrifices and solicitude of later generations.[7] Nonetheless, the cost of shipping a coffin safely home could be prohibitive. To avert the tragedy of burial away from native soil, native-place associations assisted less able fellow-provincials in achieving the goal of home burial. The associations also

[6] Skinner ("Introduction," 545) suggests that failed sojourners were among those buried in paupers' graves, dying an "anonymous and ignominious urban death." Nonetheless, "pauper burial grounds" (yimu ) were maintained by a number of native-place associations, in addition to their regular cemeteries and coffin repositories, so that impoverished sojourners could receive a burial connecting their spirit to their native place. Chaozhou and Ningbo huiguan meeting notes suggest that corpses were only retained by the Tongren Fuyuantang (a major Shanghai charitable institution) when native place could not be determined (or when a native-place association did not claim the corpse).

[7] See C. K. Yang, Religion in Chinese Society (Berkeley, Calif., 1970), 39-40; James Watson and Evelyn Rawski, eds., Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China (Berkeley, Calif., 1988).

established graveyards in Shanghai for sojourning fellow-provincials entirely lacking in means. Many of these burials were considered temporary, pending shipment home. Similarly, buildings were erected in Shanghai for the temporary storage of coffins until they could be shipped back to the native place, and funds were collected within the native-place community to assist with building expenses. Foreign travelers in China in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries frequently observed the shipment of corpses in heavy, hermetically sealed coffins, expressing adherence to the ideal in practice. Large-scale temporary storage of coffins, contact with cemeteries in the native place, coordination of transportation, and the underwriting of coffin transportation expenses were continual and important areas of huiguan activity.[8]

Separation and Suffering . The act of sojourning stimulated both the cultivation of native-place sentiment and linkage among fellow-provincials. Mutual ties developed and intensified as fellow-countrymen traveled beyond their native place, leaving the special way of speaking and the unique forms of dried tofu or sweet cakes of their village; passing through neighboring counties with still comprehensible dialects and recognizable dishes; and arriving finally in strange places where words were unfamiliar and palatable food was difficult to find. Both the tongxiang (fellow-provincial) bond and the nostalgic recreation of the native place were sojourner responses to separation from the native place and the hardship that such separation was perceived to entail.

The suffering that sojourning entailed was a frequently evoked literary theme. Few literate Chinese would not have been familiar with Li Bai's famous poem:

The moon shines on my bed brightly

So that I mistake it for frost on the ground.

[8] For example, see J. J. M. de Groot, The Religious System of China , vol. 3 (Taipei, 1892-1910), 838; "Notice of the Siming Gongsuo," Shenbao (hereafter referred to as SB), March 14, 1912. Rowe (Hankow: Commerce and Society , 265) suggests that in Hankou there was little evidence of the shipment of coffins. There is no doubt regarding Shanghai ("Siming gongsuo yi'anlu" [Meeting notes of the Siming Gongsuo], 1915-39, manuscript, Shanghai Municipal Archives [hereafter referred to as SGY]; "Chaozhou huiguan yi'an beicha" [Meeting notes of the Chaozhou Huiguan], 1913-39, manuscript, Shanghai Municipal Archives [hereafter referred to as CHYB]; see also SB, March 14, 1912).

I gaze at the moonlight with head lifted;

Now my head droops and I think of my native place.[9]

Immigrants separated from their native place were not merely nostalgic, they believed they suffered physically and spiritually from the separation. In a letter to the Shanghai newspaper, Shenbao , the Xiangshan writer "Rong Yangfu" (a pseudonym) defended the integrity of people from his native place in the province of Guangdong, who had been maligned in a previous article. He began by describing the richness of Xiangshan intellectual traditions, evidenced by the famous Huang and Zheng families which had produced eighteen generations of Xiangshan scholars. Then, in order to account for the existence of disreputable Xiangshan prostitutes in Shanghai, he argued that because of their separation from their native place, the moral character of these individuals had deteriorated and they were no longer really Xiangshan people. They may have been born in Xiangshan, but they had become impure in the polluting atmosphere of Shanghai: "How is it that none speak the Xiangshan dialect? The reason is that they were kidnapped young from Xiangshan to serve in Shanghai in these despicable professions. Moreover, when they came to this foreign place they drank the water and ate the food, and their language changed. Their hearts also changed."[10]

For Rong and his audience, native-place identity derived as much from the food and water of the native place as from the culture and dialect—in fact, the intake of foreign food resulted in linguistic and even spiritual destruction. In the sojourning condition, native-place identity was invoked less as a birthright than as a delicate plant which demanded constant cultivation.

Expressions of the importance of connection with the native place for the living were mirrored in the spiritual realm. There were two types of huiguan: yang huiguan , for the living; and yin huiguan , for the dead. Serving the dead in the manner that yang huiguan served the living, yin huiguan were built in burial grounds where they housed coffins, comforting and uniting the sojourning souls.[11]

Even gods who were away from their native place were believed to

[9] "Thoughts on a Quiet Night" (Jing ye xiang ), adapted from Liu Shih Shun, One Hundred and One Chinese Poems , 20-21.

[10] SB, January 17, 1874. "Rong Yangfu" is the composite of three surnames.

[11] The term yin huiguan has sometimes been misunderstood to refer simply to the building constructed by the huiguan to house coffins. The larger ritual function is apparent from records of yin huiguan construction in CHYB, December 1923; January 1924.

suffer. In cities outside Fujian, figures of the Fujianese goddess Tianhou (Empress of Heaven) were carried to the local Fujian huiguan to be ritually reunited with their native soil.[12]

Sojourners' Constructions of Native-Place Community. Huiguan were nodal points in a system of formal and informal native-place coalitions which marked the urban landscape, and they are therefore a major focus of this study. Because they bore native-place labels, brought together sojourners in various activities and represented the "face" of different native-place communities, they were crucial sites for the construction of a positive idea of native-place identity and community for their sojourning populations. This development of community relied on financial resources and networks of influence in the city, resources which motivated the development of patron-client tics connecting poorer sojourners to a sojourning elite. Groups without the means to construct native-place associations tended to have weaker identification with fellow sojourners in Shanghai and weaker notions of native-place identity.

Sojourners established huiguan to create a supportive home environment in an alien city as well as to symbolically assert the importance of their sojourning community.[13] Formal association began with the construction of a temple for local gods and burial-grounds or coffin repositories for sojourners. Through their connection with religious life and critical ritual moments in the lives of sojourners, associations maintained native-place ties and sentiment over long periods in foreign environments, contributing to the organization of trade and safeguarding native-place business or trade interests. These associations played a formative role in organizing what might be called the "raw materials" of native-place sentiment—dialect and the local practices people brought with them into the city—and reformulating them into an urban representation of native-place community.

Native-place sentiment and organization in the sojourning community worked in the manner of a large kin organization. The number of

[12] Zhang Xiuhua, "Wo he Tianhou gong" (My experiences with the Temple of the Empress of Heaven), Tianjin wenshi ziliao xuanji (Selected materials on Tianjin history and culture) 19 (March 1982):190.

[13] The native place itself provided no such supportive environment but, rather, one fraught with strife and competition. The nature of native-place community was transformed by sojourning. See James Cole, Shaohsing: Competition and Cooperation in Nineteenth-Century China (Tucson, Ariz., 1986).

actual kin sojourning in a city could rarely be large enough to constitute a powerful organizational base. The tongxiang tie had the advantage of encompassing a significantly larger group, subsuming within it kin ties.[14]Huiguan directors consciously reinforced the linkages between their associations and actual organized lineages through the institution of the worship of deceased huiguan directors. The spirit tablets of these former directors (xiandong shenwei ) served the role of huiguan ancestral tablets.[15]

Although sojourners at most levels of society coalesced into native-place groups, only communities with sufficient capital could undertake the construction of the large buildings and burial complexes that characterized fully developed native-place associations. Within each city, the native place was reconstituted according to the size and stature of the sojourning urban community. If sojourners from one province were sufficiently numerous and wealthy, they formed several prefectural-level (sometimes even county-level) associations. Where sojourners were more scarce, they formed provincial-level associations and even associations of people from adjacent provinces. Thus, for instance, a person in Shanghai from Huilai county, in Chaozhou prefecture (Guangdong), belonged to the Chao-Hui Huiguan (representing the two counties of Chaoyang and Huilai), one of several associations serving the relatively large population of Chaozhou sojourners. In Suzhou, by contrast, as the Guangdong community grew smaller over the course of the nineteenth century, the originally separate Chaozhou association merged with the Liangguang association, which represented the two provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi.

The variability of association names and degrees of territorial inclusiveness in different cities has led some scholars to question the real importance of the native-place idea in social organization.[16] Evidence from Shanghai of contact among associations in different cities representing overlapping native-place areas suggests that, in fact, such flexibility was an active tactic facilitating the maintenance of native-place

[14] Skinner, "Introduction," 541.

[15] According to meeting notes of the Siming Gongsuo, after one hundred years directors had "spirit niches" (shenkan ) built for them in the Gongsuo's Tudi (earth god) temple, which were worshipped on the Chinese New Year, "in return for their service" (SGY, July 1919).

[16] Gary Hamilton, "Nineteenth Century Chinese Merchant Associations: Conspiracy or Combination?" Ch'ing-shi wen-t'i 3 (December 1977):60-62; Rowe, Hankow: Commerce and Society , 263.

communities. Although it is certain that native-place associations reflected practical as well as sentimental imperatives, it would be a mistake to imagine that sentiment (as opposed to instrumentality) was secondary in the nature and activities of these associations. First, there were definite limits to the flexibility of the concept. Although the native-place unit could expand to encompass adjacent prefectures and even provinces, it was normally unthinkable that northerners and southerners, for instance, or people from nonadjacent provinces would organize together in a single huiguan . Second, study of the broad compass of associational activity (as opposed to a limited functionalist view which sees native-place ties as tools of economic self-interest) makes dear an inextricable interweaving of religious practice, economics, taste, habit, and other cultural meanings. Finally, and most important, it is critical to recognize that (however flexible the native-place idea was in practice) communities in the city nonetheless constructed themselves symbolically in reference to a unit of place, a "placeness" which provided a basis not simply for individual identity but also for connections among people. The impulse to organize on the basis of place is epitomized by the Pudong Tongxianghui, a native-place association in Shanghai formed by local people who were not actually sojourners.

The construction of organized communities and institutions of fellow-provincials meant that the native-place identity of sojourners linked them not only to their native place but also to their reconstituted native-place community in Shanghai. This resulted in a kind of doubling of gestures. The wealthy maintained face in both communities, funding charitable works among fellow-sojourners in Shanghai and for fellow-provincials at home. Similarly, birthdays and other celebrations were held in both places. Upon his father's sixtieth birthday, for instance, the wealthy Xiangshan businessman Xu Run demonstrated his filial piety by constructing congratulatory "longevity halls" (shoutang ) in both Shanghai and Xiangshan. Thus an understanding of the nature of native-place sentiment in Shanghai must comprehend the re-creation of the native-place community in Shanghai.[17]

Because Shanghai huiguan often established regular communication with huiguan in other cities representing the same native place, it is also possible to speak of the creation (despite the apparent contradiction) of a third, interurban, level of native-place community on the national

[17] Xu Run, Xu Yüzhai zixu nianpu (Chronological autobiography of Xu Run) (Shanghai, 1927), 25.

level. This seemingly paradoxical creation of national communities out of native-place tics was a critical element in the modern transformations of native-place community. Although the grouping together of fellow-provincials segmented cities internally, it also resulted in the transcendence of urban borders, integrating urban centers into larger interurban networks of fellow-provincials. Sojourning Guangdong merchants in Shanghai were in dose touch with sojourning fellow-provincials in other ports where they maintained business interests. In several cases, stronger and wealthier Shanghai huiguan directed the activities of smaller and weaker ones. The Shanghai Chaozhou Huiguan, for instance, often directed the affairs of the Suzhou Chaozhou Huiguan. The Siming Gongsuo, or Ningbo Huiguan, maintained close contact with Ningbo groups in other cities and oversaw and coordinated activities on a multiport scale.

The potentially national scope of native-place communities is confirmed by the example of the Hu She, an association formed by sojourners from Huzhou (Zhejiang). The Hu She was explicitly established in 1924 on a national basis, with its central headquarters in Shanghai and branch offices in Nanjing, Wuhan, Suzhou and Jiaxing, among other cities. The existence of formally and informally constituted national so-journing networks highlights the paradox of "local" native-place ties as they functioned historically. Although it might be imagined that native-place sentiment was necessarily localistic and parochial, the existence of multiple levels of native-place community meant that in practice the horizons of native-place sentiment could range from the provincialism of the native place, to more cosmopolitan Shanghai urban awareness, to deep involvement in national issues.[18]

The Native Place and China . Although Chinese commentators understood native-place sentiment to be natural, they also described it as virtuous and "morally excellent," as illustrated by the quotation which begins this chapter. The virtue of native-place sentiment lay

[18] CHYB; SGY; Hu She dishisanjie sheyuan dahui tekan (Special issue on the 13h general members' meeting of the Huzhou association) (Shanghai, 1937); Chen Lizhi, Hu She cangsang lu (Records of the vicissitudes of the Hu She) (Taipei, 1969). In her compelling study of Zhejiang elites, Mary Backus Rankin describes interprovincial networks of Zhejiang sojourners centered on Shanghai; see Elite Activism and Political Transformation in China: Zhejiang Province, 1865-1911 (Stanford, Calif., 1986), 268-73. The degree to which individual sojourners participated in national communities would depend both on the individual's place within the sojourning community (elite or non-elite) and on the commercial or political reach of the particular native-place community in question.

in its groundedness in a larger political ideology which deepened the rationale for native-place ties and gave them broader and extralocal significance. Love for the native place was virtuous because it helped to constitute and strengthen the larger political polity of China. Native-place sentiment was vulnerable (as suggested by the second quotation) if it was not attached to this larger ideal. Therefore the leaders of native-place organizations in the nineteenth century legitimized their associations not through appeals to nature or to utility but through reference to Chinese identity.

For most of the nineteenth century the ideological connection between native-place identity and Chinese identity was grounded in quasi-Confucian ideas of concentric circles of cultural and territorial identity. This rationale for the establishment of native-place associations is reflected in a statement of the origin of the Shanghai Guang-Zhao Huiguan (Guangzhou and Zhaoqing prefectures, Guangdong):

China is made up of prefectures and counties and these are made up of native villages, [and the people of each] make a concerted effort to cooperate, providing mutual help and protection. This gives solidarity to village, prefecture and province and orders the country. Since [ancient agrarian harmony deteriorated], merchants have increasingly sojourned in distant places, living with people not from their native village, county or prefecture, and they have different senses of native-place feeling. Thus people from the same village, county and prefecture gather together in other areas, making them like their own native place. This is the reason for the establishment of huiguan . This is the ancestors' way of expressing affection for later generations. Shanghai is first under heaven for commerce, and the gentry and officials of our two Guangdong prefectures of Guangzhou and Zhaoqing are more numerous here than merchants from other places. [Therefore we established a huiguan .][19]

Such statements, which resembled in structure the concentric logic of the Confucian text "The Great Learning" (Daxue ), also served strategic purposes, defusing threats both from the state and from hostile locals in Shanghai who would view the establishment of an outsiders' huiguan with suspicion. Given the hostility of the Qing state toward private associations, this statement, like others of its type, invoked Confucian values as a means of providing legitimacy to the organization by linking local

[19] "Shanghai Guang-Zhao huiguan yuanqi" (The origin of the Shanghai Guang-Zhao Huiguan) (Tongzhi period [1862-1874]; hand-copied document, courtesy of Du Li, Shanghai Museum). My interpretation of this quotation has benefited from discussions with Joseph Esherick and Ernst Schwintzer.

solidarity to the order of the polity (leaving the commercial advantages of association unstated). Similarly, such statements stressed a common orthodoxy which could be shared by people from different places, help-hag to dispel perceptions that sojourners were utterly foreign. In this regard, native-place associations brought with them into the city a language of common Chinese identity, even as they served as powerful markers of cultural difference among different Chinese groups.

The Chinese elites, reformers, and community leaders who articulated ideological connections between the native place and the larger political entity of China would, over time, abandon their invocation of Confucian values and take on the rhetoric of modern Chinese nationalism. In the process, their use of native-place sentiment and organizations would both reflect and help to define the urban development of Chinese nationalism.

Native-Place Divisions in Shanghai: The Surface of City Life

In late-nineteenth-century Shanghai more than half the population was made up of immigrants from other areas of China, and distinctions along lines of regional identity were reflected everywhere in city life. Language separated immigrant groups, as did varying ethnic traditions, differences in the organization of daily life and preferences in the choice of marriage partners. There were also regional divisions in urban geography, religious expression, the organization of trade, education and welfare, and even the organization of social control and social unrest.

Regional groups were not just distinct but unequal. Native-place identities helped structure socioeconomic and to some extent gender hierarchies in the city. These hierarchies corresponded to the economic power of different sojourning groups. At the peak of regional and occupational hierarchies were people from Zhejiang, Guangdong and southern Jiangsu province. The stature of a given sojourner community depended on the power of its elites, because workers (in terms of sheer numbers) dominated nearly all sojourning communities. Immediately after the opening of Shanghai as a treaty port, Guangdong merchants rose quickly through involvement in foreign trade. By the 1860s, despite Guangdong and Jiangsu competition, Zhejiang sojourners dominated

the critical banking, shipping, and silk sectors. Considerably lower in the Shanghai native-place hierarchy were people from Shandong, Hubei, and northern Jiangsu (Subei), regional communities with weak elites and whose non-elite members were often unskilled laborers in Shanghai. As Emily Honig points out, the appellation Subei ren "was a metaphor for low class." Even today Subei people are avoided as marriage partners by Shanghainese.[20]

Language was the first marker of native-place differences, separating new immigrants from other residents in the city. Even after generations of common residence in the city, distinct and frequently mutually unintelligible dialects made communication among different immigrant groups uncomfortable at best and often impossible. According to a description published in 1917,

Shanghai is a mixed-up place of people from many regions, the languages are numerous and jumbled and cannot be carefully enumerated. We can generally divide them into categories: 1) Guangdong speech—foreigners came north from Guangdong to Shanghai, therefore Guangdong people are powerful. 2) Ningbo speech—Ningbo borders the sea and opened relatively early; Ningbo people also came to Shanghai first. 3) Jiangsu people's speech—the hosts. 4) Northern speech—wealthy merchants, traders and actors from Beijing, Tianjin, Shandong, Shaanxi.... 5) Shanghai local speech ... [but] aside from the areas south and west of the city wall where there are pure locals, speech has continually changed and so-called Shanghai vernacular is usually a mixture of Ningbo and Suzhou speech; not the same as before the opening of the treaty port.[21]

As late as 1932, the Shanghai writer and astute social observer Mao Dun commented on the lack of a functioning common language among working people in Shanghai. After conducting an investigation among Shanghai workers to see how people from different places communicated with each other, he concluded that after eighty years of immigration into the city, Shanghai had no common language. He found instead

[20] See for example, Yuen-sang Leung, "Regional Rivalry in Mid-Nineteenth Century Shanghai: Cantonese vs. Ningbo Men," Ch'ing-shih wen-t'i 8 (December 1982):29-50; Rankin, Elite Activism , 85; Emily Honig, "The Politics of Prejudice: Subei People in Republican-Era Shanghai," Modern China (hereafter referred to as MC 15 (July 1989):243-74; Emily Honig, Creating Chinese Ethnicity: Subei People in Shanghai, 1850-1980 (New Haven, Conn., 1992), 4.

[21] Yao Gonghe, Shanghai xianhua (Shanghai idle talk) (Shanghai, 1917; Shanghai Guji Chubanshe reprint Shanghai, 1989), 19. An account of the languages of Shanghai written in nearly identical language may be found in Xu Ke, Qing bai lei chao (Qing unofficial writings) (Shanghai, 1916; Shangwu yinshuguan reprint Taipei, 1983), 43:24.

a minimum of three emerging types of "common speech." The first type used Shanghai local dialect as a basis, with an admixture of elements of Guangdong, Northern Jiangsu (Jiangbei) and Shandong dialects. The second used Jiangbei dialect as a basis, with liberal additions of Shanghai and Shandong phrases. The third was a kind of Shanghai-accented northern speech, with similar admixtures from other dialects. The "common language" used in any given location depended on which native-place group predominated. For people who spoke other native dialects, he observed, this meant that any communication in the "common language" would be necessarily crude and limited in vocabulary.[22]

People from different parts of China tended to live in different neighborhoods, or "small cultural enclosures," in the description of a recent study of Shanghai popular culture.[23] Ningbo people in Shanghai lived in the northern part of the Chinese city and in the French Concession. Guangdong people lived in the southern part and southern suburbs of the Chinese city, and in several distinct neighborhoods in the International Settlement. Jiangxi people were concentrated in Zhabei, to the north and west of the International Settlement. Poor immigrants from northern Jiangsu settled first in shack districts along the banks of the Huangpu and in growing tenement areas, especially in Zhabei, that were referred to as "Jiangbei villages."[24]

These residential divisions were complex and often overlapping, reflecting different areas of settlement for workers, as opposed to wealthy sojourners or resulting from different immigrant waves. Although the

[22] Mao Dun, "Wenti zhong de dazhong wenyi" (Problems for art and literature for the masses), originally published in Wenxue yuebano (Literature monthly) 1 (July 1932), reprinted in Zhongguo xiandai wenxue shi cankao ziliao (Research materials for the history of modern Chinese literature) (Beijing, 1959), 335-37. Jiangbei refers to the area of Jiangsu province north of the Yangzi. For the definition of Jiangbei in Shanghai, see Honig, Creating Chinese Ethnicity , chap. 2.

[23] Zheng Tuyou, "Chongtu, bingcun, jiaorong, chuangxin: Shanghai minsu de xingcheng yu tedian" (Conflict, coexistence, mixture and new creation: The formation and characteristics of Shanghai popular culture), in Shanghai minsu yanjiu (Research on Shanghai customs), Zhongguo minjian wenhua (Chinese popular culture), ed. Shanghai minjian wenyijia xiehui (Shanghai popular culture committee), vol. 3 (Shanghai, 1991), 9.

[24] Because the entire native-place community did not live together, neighborhood divisions were not neat. Different trades were located in different areas; workers often lived around the enterprises employing them; new immigrants often lived in areas other than those in which older residents lived. This complexity did not mean that different groups blended in a neighborhood; rather, the city was made up of many small groups, parts of larger native-place communities. See Leung, "Regional Rivalry," 30-33; interview with Shen Yinxian, who cared for the gods in the Jiangxi Huiguan until the Cultural Revolution, Shanghai, October 1983; Honig, Creating Chinese Ethnicity , 45.

intricacies of residential divisions and subdivisions make them difficult to trace on a map, they were present in the minds and daily experiences of Shanghai residents. Newspapers commonly referred to areas such as Hongkou as Cantonese, or, similarly, to "the Fukien part of the suburbs." Specific roads were identified by the native place of their inhabitants. According to Zhan Xiaoci, son of the Quan-Zhang Huiguan director, Zhan Ronghui, sojourners from the Minnan dialect area of southern Fujian lived around Yong'an Road and East Jinling Road. In the words of Hu Xianghan, whose description of Shanghai neighborhoods was published in 1930, North Sichuan, Wuchang, Chongming and Tiantong roads were "just like Guangdong"; Yanghang Road, outside the small east gate of the Chinese city, was "just like Fujian." Prior to the renaming of many streets in the Communist era, a number of Shanghai street names were named for native-place associations which built them or were located on them, or for their Guangdong, Fujian or Ningbo sojourner inhabitants.[25]

Because of residential overlap and the needs of trade, people from different native areas might do business together at the same teahouse. Nonetheless, the regional types—to the extent of body shapes and sartorial differences—were easy to distinguish, even for the foreign observer: "An experienced eye readily detects in the crowd that peoples the teashop, the visitors from the different cities which have dealings with Shanghai and the man who is at home. We see Soochow men, Shantung men in their warm hoods, both contrasting with the spruce Cantonese or the man from Hangkow or Kiukiang."[26]

Shanghai architecture, like Shanghai street names and neighborhoods, reflected the influence of different native-place groups and the presence of native-place associations. As Shanghai housing strained to accommodate the growing population, there was widespread construction of simple adjacent houses along Shanghai alleyways (lilong ). Among the several types of lilong housing were the "Guangdong-style

[25] North China Herald (hereafter referred to as NCH), August 17, 1850; interview with Zhan Xiaoci, Quanzhou, Fujian, March 19, 1984; Hu Xianghan, Shanghai xiaozhi (Little Shanghai gazetteer) (Shanghai, 1930; Shanghai guji chubanshe reprint, Shanghai, 1989), p. 51; Xue Liyong, Shanghai diming luming shiqu (Shanghai place-name and street-name anecdotes) (Shanghai, 1990), 140-48. The passages in Hu are cited in Zheng Tuyou, "Chongtu," 9, and in Elizabeth Perry, Shanghai on Strike: The Politics of Chinese Labor (Stanford, Calif., 1993), 17. Regional differentiation of neighborhoods persists, to a degree. Ningbo people are particularly numerous in the southern part of the old city; Zhabei continues to be the residence for many people from Subei.

[26] NCH, February 8, 1872.

residences" (Guangshi fangwu ), relatively simple two-story buildings which grouped three to four residences together in an entryway. Such homes were concentrated in the Hongkou area (an area known for its Guangdong population), where they housed workers, peddlers, and other low-income people.[27]

The continuous construction and renewal of buildings housing native-place and trade associations provided visible reminders both of the permanence of regional organization within the city and the unequal power of specific regional groups. In post-Opium War Shanghai and in many other cities, the headquarters of wealthy associations were the most imposing buildings in the city, encrusted with gold-painted carvings, often with wood or special construction materials brought from the native place. British visitors to Shanghai in the 1850s found the larger huiguan more impressive than Chinese government offices. In contrast, weaker sojourner groups often lacked the funding to establish even rudimentary buildings. Subei sojourners, for example, had no association hall in the nineteenth century and therefore lacked a crucial symbol and organizational trait for developing identity and community.[28]

Although the care employed in the construction of huiguan distinguished them from the unenthusiastically built government offices, they resembled these offices in both architectural form and function. Self-conscious expressions of the wealth and power of their communities, the grandeur of these buildings and their formal resemblance to the county and circuit yamen expressed also their function as governing centers for their sojourning populations. The architecture of the city attested to what Van der Sprenkel described as two loci of government in Chinese cities, the official (stemming from the yamen ), and the unofficial (stemming from associations like huiguan ).[29]

Huiguan buildings incorporated the great walls, gates, multiple courtyards, halls, side offices and gardens of the official yamen style, and

[27] Chen Congzhou and Zhang Ming, eds., Shanghai jindai jianzhu shigao (Draft history of modern Shanghai architecture) (Shanghai, 1988), 161-63.

[28] General Description of Shanghae and Its Environs (Shanghai, 1850) provides the following explanation for the poor appearance of public buildings: "The reason is that when ... offices [of the Shanghai magistrate and Daotai] have to be erected, an order is issued to the people to build ... and as the officials are seldom or ever favorites, the people do as little for them as they possibly can. Hence they procure the smallest sized timber and the most fragile materials, so as to run up sheds of a given size in the cheapest manner."

[29] On the lack of a positive self-definition of Subei native-place identity, see Honig, Creating Chinese Ethnicity , 28-35. See also Sybille Van der Sprenkel, "Urban Social Control," in Skinner, The City in Late Imperial China , 609-32.

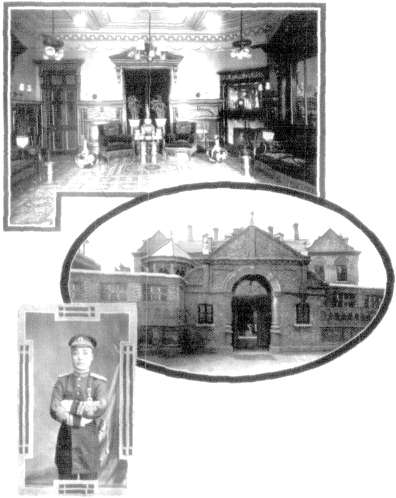

Figure 1.

Yamen architecture. Source: Tongzhi Shanghai xianzhi (Tongzhi-

reign Shanghai county gazetteer) Shanghai, 1871.

also features of temples, notably altars for their local gods and stages for theatrical productions (see Figures 1 and 2). In this composite architectural form they embodied both secular and spiritual authority for their communities.

The spatial and architectural effects of regional communities did not function only to divide the city. Although residential patterns and architecture marked native-place differences in the city, the fact of immigration and the presence of small Guangdong, Ningbo, Fujian and Jiangxi areas in the city in a sense made Shanghai into a miniature of all of China. Even as immigrant groups maintained their own customs in the city, their common presence concretized the diversity of China in one locality, making the larger polity more conceivable. Huiguan buildings, mostly grouped together around the old city and the eastern commercial areas, suggested not simply difference but also—in their common form—a certain Chinese universality. Although the ornaments and furnishings of different huiguan reflected the tastes and materials of their native places, there is a certain irony in the fact that (for all their regional specificity in function and culture) in architectural form all huiguan were

structurally similar. In this sense, once again, huiguan present the curious paradox of containing both provincial and universal aspects.

Native-place identity was frequently worked out on the streets, on the docks and in factories, where tensions emerged among economically competing groups. People from different regional backgrounds were often involved in fights. Native-place ties also organized or subdivided Shanghai gangs. Guangdong gangsters backed up Guangdong merchants on the street. The Subei gangsters Jin Jiuling and Gu Zhuxuan recruited followers through the native-place association they directed.[30]

[30] For a discussion of regional divisions in gangs, see Wu Zude, "Jiu Shanghai banghui xisu tezheng" (Characteristics of old Shanghai gang culture), in Shanghai minjian wenyijia xiehui, Shanghai minsu yanjiu , vol. 3, 80-85.

Figure 2.

Huiguan architecture. Source: Huitu Shanghai zazhi

(Shanghai pictorial miscellany) Shanghai, 1905.

Major social conflicts could also reflect native-place community and organization. There were, for instance, two major "Ningbo Cemetery Riots" when, in 1874 and 1898, the French attempted to build a road through a Ningbo burial ground. In the Revolution of 1911 as well as in the great nationalist social movements of the twentieth century, the May Fourth Movement and the May Thirtieth Movement, native-place associations were responsible for the mobilization of their fellow-provincials.

Similarly, native-place divisions were critical to social control. Both Chinese and foreign authorities held native-place associations responsible for the actions of their fellow-provincials. Chinese and foreign courts also routinely referred cases back to fellow-provincial associations. The severity of punishments meted out in Chinese courts could also vary

according to the native place of the offender. A foreign observer noted in 1868, for instance, that "the heavy bamboo is only used on very bad Characters or Cantonese."[31]

Distinctive native-place cultures were reproduced through a variety of social institutions and practices. Education was frequently organized by native-place groups, a practice which reinforced and perpetuated differences in dialect and custom. Guangdong children went to Guang-dong schools; Ningbo children went to Ningbo schools; Fujianese attended school at the Quan-Zhang Huiguan (Quanzhou and Zhangzhou prefectures).

Native-place identity was vigorously defined through cuisine, an enormously significant area of cultural articulation in China. Chinese guides to Shanghai written in the late Qing and Republican period abound in descriptions of regional cuisines and characterizations of the types of people who ate each sort of food. Restaurant location and the relative importance in Shanghai of a regional cuisine depended on the prominence of sojourners from that area. The principles underlying the distribution of Shanghai restaurants are explained by Wang Dingjiu, editor of a 1937 guide entitled The Key to Shanghai (Shanghai menjing ), in a, section entitled, "Key to Eating":

Shanghai commercial power has always been divided between two major groups, Ningbo and Guangdong.... Although the power of Guangdong people is not as widespread as that of Ningbo people, their strength is still considerable. The three famous department stores, Yong'an, Xianshi and Xinxin, all are headquarters of Guangdong merchants. Thus the Guang-dong restaurant trade, in recent years, has become extremely well developed....

Because Anhui people are most numerous among the clerks in the Shanghai pawnshop trade, on the streets where there are pawnshops there will always be one or two Anhui restaurants to serve the appetites of their tongxiang . Thus [the existence of Anhui restaurants] is in direct proportion to the existence of pawnshops....

There are many Ningbo people sojourning in Shanghai and they are extremely powerful ... [but] the taste of Ningbo food is not congenial to most people. Therefore, aside from Ningbo and Shaoxing customers, people from other areas don't welcome it.[32]

[31] NCH, October 3, 1868. This article goes on to observe a "notable ... difference [in the manner in] which the punishment is carried out on Cantonese and Northerners; the former catching it awfully."

[32] Wang Dingjiu, "Chi de menjing," in Shanghai menjing (The key to Shanghai) (Shanghai, 1937), 7-26.

Rather than cultivate cosmopolitanism, most Shanghai residents preferred when possible to eat their own native-place cuisine. By the 1930s Shanghai guidebooks encouraged the development of somewhat more experimental tastes, and observers reported that Guangdong food (and occasionally Sichuan food) had become fashionable. This was achieved, apparently, only with strenuous promotion on the part of entrepreneurial chefs who wooed local palates. According to one account, although Guangdong restaurants were physically attractive, most Shanghai residents found them too expensive and, moreover, could not understand the ornate food names on their menus, with their references to "phoenix claws," "tigers," "dragons" and "sea dogs." Beginning in the 1920s the Guangdong Xinya restaurant on Nanjing Road added to its menu sauteed shrimp, a popular Jiangsu dish, thereby luring Jiangsu people inside. Although guidebooks admitted that Cantonese food tasted good and could be enjoyed even by non-Cantonese, this was not the case for other regional cuisines. Anhui restaurants, for example, languished economically because they were unable to attract a large clientele. Not only was Ningbo cuisine feared by nonnatives, but those who walked unaware into the restaurant of another regional group risked poor treatment: "If you try Ningbo food make sure you go with a Ningbo person. The price will be less expensive and the quality better. If you go as an outsider they will cheat you."[33]

Native-place tastes and affectations were equally pronounced in the "flower world" and "willow lane." The lore of Shanghai prostitution suggests regional recruitment and organization, with different euphemisms, prices and practices associated with prostitutes from different regions. Wang Dingjiu introduces Shanghai brothels in much the same manner as his account of Shanghai restaurants:

Shanghai is a great marketplace ... and it is also a marketplace of sex. The many brothels are convenient for travelers and stimulate the market. Thus prostitution and commerce are intimately related.... Since there are so many sojourning Ningbo merchants in Shanghai, Ningbo "temple disciples" [euphemism for prostitutes] have a special position in the prostitute world.... When non-Ningbo people hear the speech of Ningbo girls they get gooseflesh and shiver. But they suit Ningbo appetites. Thus the customers of Ningbo prostitutes are mainly their own tongxiang .[34]

[33] Quotation from Wang Dingjiu, "Chi," 26. Other sources are Hu Xianghan, Shanghai xiaozhi , 39-41; Zheng Tuyou, "Chongtu," 17-18.

[34] Wang Dingjiu, section titled "Piao de menjing," 1, 34.

Prostitutes were ranked imaginatively in a native-place hierarchy. According to a guide to Shanghai, Suzhou women dominated the most expensive grade of prostitutes, called chang-san . Suzhou women were also considered most beautiful. The next rank of Suzhou prostitutes were called yao-er . Ningbo prostitutes, whose quality and ranking were between the two levels of Suzhou brothels, were called er-san . Prostitutes from Guangdong were divided into two categories, a high-class "Guangdong prostitute" (yueji ) and the lower class "salt-water sisters" (xianshuimei ). These latter were unique in that they catered exclusively to foreigners. Each regional group brought its own local brothel tradition. Ningbo prostitutes wore different clothes and served different delicacies than did Guangdong prostitutes. Although higher-priced prostitutes of different groups all sang pieces from Beijing opera, they specialized in the songs and opera of their native place.[35]

The example of prostitution points to the importance of native-place identities as a classificatory scheme in the minds of Chinese urban residents. As Christian Henriot has demonstrated, in contrast to the insistence of Shanghai writers on the existence of a strict regional hierarchy, the regional organization of prostitution was an ideal which was only partially maintained in practice. Economic conditions and recruitment channels were such that the largest number of prostitutes came from places near Shanghai. The numbers of Cantonese and Ningbo prostitutes were small compared with the size of their communities. Because of widespread recognition of the beauty of Suzhou women (and perhaps because exoticism was an asset in the realm of sexual desire) Shanghai elites showed more cosmopolitan tastes in this area, patronizing the higher-class Suzhou prostitutes, whether or not the clients themselves were from Suzhou. Such cosmopolitanism could nonetheless reinforce native-place distinctions, real and fictional.

[35] Ibid., 33-39; Qian Shengke, "Jinü zhi hei mu" (Dark secrets of prostitutes), in Shanghai hei mu bian (Compilation of Shanghai's dark secrets) (Shanghai, 1917), 1-24; "Piaojie zhinan" (Guide to prostitutes), Shanghai youlan zhinan (Guide to visiting Shanghai) (Shanghai, 1919), 1-51; Chen Boxi, ed., Shanghai yishi daguan (Anecdotal survey of Shanghai) (Shanghai, 1924), vol. 3, 79-100; Renate Scherer, "Das System der chinesichen Prostitution dargestellt am Beispiel Shanghais in der Zeit yon 1840 his 1949" (Ph.D. diss., Free University of Berlin, 1981), 97-99, 116, 134-35; 146; Gail Hershatter, "The Hierarchy of Shanghai Prostitution, 1870-1949," MC I5 (October 1989):463-98; Gail Hershatter, Shanghai Prostitution: Sex, Gender and Modernity (tentative title, forthcoming). The names chang-san and yao-er , derived from mah-jongg tiles, referred to a scale of prices.

Non-Suzhou women cultivated Suzhou accents in order to command higher prices.[36]

Theater, like cuisine and like "the flower world," reflected different regional styles and aesthetics. The existence of different regional operas in the city—Anhui, Suzhou, Guangdong, Shaoxing, and Beijing styles, to name a few—and the location of many opera performances in huiguan suggest not a common theatrical experience but a divided one. Open-air performances did not exclude nonnatives and were surely enjoyed by many urban residents who were simply attracted to the excitement. But insofar as native-place communities sponsored performances of their regional operas, these performances reflected the "face" of specific native-place groups in the city.

Urban religious practices also marked group boundaries, dividing the Chinese urban residents of Shanghai into separate communities. Different native-place groups identified with different deities, different locations for religious observances and somewhat different festival calendars. Even when different communities shared gods, they commonly had different temples. For example, sojourners from coastal, seafaring areas, especially along China's southeast coast, worshipped the goddess Tianhou. People from the adjacent southeastern provinces of Guang-dong and Fujian could come together for an occasional large-scale procession for Tianhou, but normal Tianhou worship was regionally subdivided: "Each Shanghai huiguan has built a Tianhou altar for worship and burning incense. Her birthday is on the 23rd day of the third lunar month. [For several days at this time] each huiguan has opera performances.... But the Jiangxi Huiguan only has a celebration [in the eighth lunar month], since Jiangxi is a linen-producing region. In the spring the merchants are in the production area buying goods. They wait until the market is slack, and use this time for [their devotion to] the god."[37]

In addition to worship of particular, regionally identified gods and regionally identified calendars, Chinese urban religious practice in

[36] See Henriot's definitive study, "La prostitution à Shanghai aux XIXe-XXe siècles (1849-1958)," 3 vols. (Thèse d'Etat, Paris, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, 1992).

[37] Yao Gonghe, Shanghai xianhua , 22-23. Tianhou, a goddess known as a protector of fishermen, was worshipped along the southeast coast of China, particularly in Fujian and Guangdong but also in Zhejiang. See James Watson, "Standardizing the Gods: The Promotion of T'ien Hou (Empress of Heaven) Along the South China Coast, 960-1960," in Popular Culture in Late Imperial China , ed. David Johnson, Andrew Nathan and Evelyn Rawski (Berkeley, Calif., 1985), 292-324.

Shanghai involved the differential practice of common festivals and a common calendar. All Chinese in Shanghai observed the common holiclays of the Chinese lunar calendar—among these the Chinese New Year, Qingming (the day of sweeping graves), and Duanwu (summer solstice). But how the holidays were celebrated—what individuals did, ate, or said on such occasions—varied according to local customs. For example, native-place tastes resulted in different styles of zongzi (leaf-wrapped steamed rice delicacies eaten at the time of the Duanwu holiday). Zhejiang-style zongzi are small and contain meat or red beans in addition to rice. Guangdong zongzi (considered faulty by Zhejiang and Jiangsu natives) are larger and contain a wider variety of stuffings mixed together—salted duck egg, yellow beans, sausage or chicken. Even to-Clay these local differences are a matter of regional pride and a means of emphasizing regional identity.

Qingming, the day on which families ritually swept their ancestral graves, could only have served to reinforce geographic differences. Native Shanghainese and people from areas close to Shanghai traveled to their family burial grounds in the outskirts of the city or in nearby villages. Sojourners from distant areas were drawn instead to their native-place cemeteries and coffin repositories in Shanghai.

The practices of everyday life in Shanghai suggest a number of observations about the possible ideas of identity and community available to Shanghai residents. It is important to consider and distinguish three obvious levels of territorial identity: native-place, urban (Shanghai), and national (Chinese) identity.[38] Most obviously, dialects, religious observances, culinary differences, and the presence of huiguan , native-place schools and other institutions in the city provided the sources and practices which defined native-place identity in the city. This potential basis for individual self-definition and collective community was experienced in the context of other, larger, bases for community and self-definition.

In addition to marking native-place identity, the quotidian habits of Shanghai residents provided sources for feelings of common Chinese identity. This becomes very clear in the context of holiday customs. Although differential New Year or Qingming practices heightened aware-

[38] For a stimulating review and reconceptualization of theoretical debates regarding the sources for and nature of ethnic and national identities, see Prasenjit Duara, "De-Constructing the Chinese Nation," Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 30 (July 1993):1-26.

ness of distinctive regional identifies, the common lunar calendar entailed the simultaneous celebration by all Chinese residents, sojourners and nonsojourners alike, elites and non-elites, of important festivals at intervals in the year. The obvious observance of common holidays by Chinese residents—contrasted with the equally obvious nonobservance of these holidays by the foreign residents in the city—highlighted a shared Chinese identity. Although it might be argued that the ideological connections between sojourner communities and China were elite constructions not shared by non-elite sojourners, daily religious practices provided an obvious source for non-elite constructions of common Chinese identity.

The question of a specifically Shanghai identity is more difficult.[39] As suggested earlier, the act of sojourning and the location of sojourners in Shanghai were crucial in providing sources for Chinese identity, both because sojourners moved beyond their localities and confronted a "China in miniature" in Shanghai's diverse Chinese population and because in Shanghai sojourners confronted foreign concessions and foreigners in a semicolonial framework. Residence in Shanghai brought Chinese into daily contact with foreigners and with the indignities of foreign privilege and foreign jurisdiction over Chinese soil. Because of these features of the city, and although the urban location was crucial, the subdivision of Chinese residents into native-place groups and the semicolonial context (which created a greater and more absolute division between Chinese and foreigners) worked together to minimize the development or expression of a common cosmopolitan, specifically urban, Shanghai identity among sojourners.

Aside from common residence in the city, it is difficult to pinpoint specifically urban practices which might provide a basis for the formation of Shanghai identity, prior to the development of a Shanghai municipal government in 1927. Although customary religious observances at times took place on a citywide scale, these celebrations did not convey a specifically urban meaning. The locations of specific festivals in hui-

[39] Location and periodization of the development of specifically Shanghai identity is a matter of some debate. For a summary of pertinent issues, see Frederic Wakeman and Wen-hsin Yeh, "Introduction," in Shanghai Sojourners , ed. Frederic Wakeman and Wenhsin Yeh (Berkeley, Calif., 1992), 1-14. For studies which assume (with varying degrees of emphasis) that shared urban identity is a crucial development in a modernization process that necessarily transcends local particularisms, see Rowe, Hankow: Commerce and Society ; William Rowe, Hankow: Conflict and Community in a Chinese City, 1796-1895 (Stanford, Calif., 1989).

guan , in native-place cemeteries, or in temples associated with specific regional groups divided Shanghai space into local territories for ritual purposes. The varied regional opera performances in the city reflected the lack of a common urban cultural style.[40] Although the foreign municipal councils of the concession areas busily constructed municipal edifices—monuments, grand avenues and government buildings—there were no competing Chinese municipal spaces—city halls or public squares—to spatially represent Shanghai identity.[41] Sojourner associations did not take part in the Shanghai city-god procession. Processions expressing specifically municipal consciousness originated in Shanghai with the foreign-concession governments and their habits of public military drilling and fire-brigade parades. These foreign demonstrations of prowess in municipal government were fled to the nationalistic sentiments of the foreign powers; each used its municipal accomplishments in Shanghai to demonstrate the superior institutions of its nation.

The presence of such displays of national power, manifested through municipal institutions, had a crucial catalyzing effect on Shanghai's Chinese residents. Their response was self-defensive participation in these foreign parades and institutions, as a matter of Chinese identity and national pride (see Figure 3). Such participation, and such expressions of Chinese identity in the last decades of the Qing, occurred in the context of organization by native-place and (occasionally) trade group. Although such moments reinforce the coexistence of native-place and Chinese identity, they do not provide evidence for common Shanghai identity.

[40] An opera style specific to Shanghai did not develop until the mid-Republican period. Shenqu (Shanghai song), recognized by the 1920s, developed gradually from an amalgamation of Jiangsu and Zhejiang styles. Mature Shanghai opera, Huju, was formalized only in the 1930s. Even in the 1930s the solidification of a Shanghai style was not a spontaneous cultural development but, rather, the result of the new municipal government's efforts to organize culture through the creation of a Municipal Shanghai Opera Research society. See Gu Tinglong, Shanghai fengwu zhi (Shanghai landscape gazetteer) (Shanghai, 1982), 270-71; Luo Suwen, "Cong xiqu yanchu zai jindai Shanghai de qubian kan dushi jumin de yule xiaofei ji shenmei qingqu" (Looking at urban residents' entertainment consumption and tastes through opera performance trends in modern Shanghai) (paper presented at the University of California, Berkeley, March 7, 1992). Scholarly and commercial elites from different native-place groups found common enjoyment in the kun and jing (Suzhou and Beijing) operas, which played at the expensive commercial theaters that appeared in late-nineteenth-century Shanghai. Such elite cosmopolitanism (or connoisseurship) was a Chinese cosmopolitanism, not a demonstration of specifically Shanghai culture or identity.

[41] For a discussion of the contrasting spatial and architectural features of Chinese and European cities, see E W. Mote, "The Transformation of Nanjing," in Skinner, The City in Late Imperial China , 114-17.

The organization of the habits of everyday life similarly facilitates reflection on sources for the development of identity on the basis of economic class. Well into the Republican era, regional divisions engendered social divisions which developed together with and helped constitute class divisions. Neighborhoods often expressed regional and occupational identity more clearly than class identity. Although, as noted earlier, mention of certain native-place identities suggested class positions (Ningbo was high; Subei was low), most native-place groups encompassed a class hierarchy within their communities. Restaurants similarly were differentiated by regional cuisines rather than by the economic capacity of their clientele. Within one building many restaurants offered food at a variety of prices—inexpensive dumplings or noodles in a common room on the ground floor; medium-priced food on the second floor, and elegant banquets in private rooms on the top floor.[42] This gustatory model of all classes together (but arranged hierarchically) under one sojourning native-place roof serves as a metaphor for the nested social layers of the broader urban regional communities.

The foregoing discussion of sources for group identities contextualizes the working out of native-place identity in the city. Native-place identity was articulated in relation to (and often in combination with) other available sources of identity, territorial and economic. The boundaries of perceived or operational community at any given moment would depend on the situational context. There was nothing in native-place identity which necessarily precluded the development of other forms of community. The ways in which native-place identity intersected with people's experiences of their national or economic positions would, however, help to shape both the development of nationalism and class formation.

Native-Place Organization and Occupational Organization

Native-place organization overlapped with the organization of trade throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centu-

[42] This organization may still be observed today in Shanghai restaurants. In 1985, at the venerable Xinya Cantonese restaurant on Nanjing Road, for instance, soup, noodles, porridge and crude dishes were served at large noisy garbage-strewn tables on the first floor; the second floor offered tablecloths and more expensive dishes; the third-floor private booths served dainty delicacies to a wealthier clientele.

ries because sojourners from specific regions tended to specialize in one or more trades. This resulted in what William Skinner described as an "ethnic division of labor" in Chinese cities. Tea traders were from Anhui; silk merchants, from Zhejiang and Jiangsu. As Elizabeth Perry's study of Shanghai labor details, artisans and workers were similarly subdivided: "Carpenters were from Canton, machinists from Ningbo and Shaoxing, and blacksmiths from Wuxi." When competing in a trade, regional networks often carved out separate niches. The sugar trade, for example, was organized separately among groups from Chaozhou, Guangzhou, Ningbo and Fujian. Shanghai idioms expressed this identity of different regional groups with specific trades. The dominance of people from Huizhou prefecture (Anhui province) in the Shanghai pawnshop trade in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for

Figure 3. Ningbo partici- pants in Parade of the

Shanghai International Settlement. Source:

Dianshizhai huabao (Di- anshi Studio pictorial

newspaper), 1983 Guang- zhou reprint of late-

Qing edition (1884- 1898).

example, is evident in the expression wu Hui bu cheng dian ("Without a Huizhou person, there's no mortgage).[43]

Because groups of fellow-provincials often practiced several trades and, moreover, because trades were not always exclusively monopolized by people from one area of China, the native-place organization of trade is not always immediately obvious. For example, there is nothing in the name of the Rice Trade (Miye ) Gongsuo to suggest that it was an organization of local Jiangsu merchants. Adding to the potential for confusion, the names of individual associations (often the only re-