| • | • | • |

“A Man of Simple Dreams”

The most critically acclaimed scenes are those that depict Nasser interacting with common Egyptians, praying in public, or at home with his family, an overworked father trying to balance politics with his children’s desire for a beach vacation. In an early scene Nasser converses with a canal worker who has been sacked by European overseers, and is moved by the injustice of his plight. Up late in his study, he answers the telephone three times after midnight, only to find on the other end a peasant woman newly arrived from the village, looking for her son. The third time, flustered by her unwillingness to accept that she has not reached Hagg Madbuli, Nasser identifies himself: “I am Gamal Abdel Nasser.”[7] Silence, then: “God save you, my son [Rabbina yansarak, ya ibni]” (‘Abd al-Rahman 1996, 32). Almost everyone’s favorite scene is stolen by the veteran actress Amina Rizq, who has been playing tradition-bound matriarchs for the past forty years.[8] Here she plays a persistent peasant woman who demands and is allowed to meet the president. Once inside she relates the story of her grandfather, a peasant killed digging the canal, and presents Nasser with the man’s robe, a family heirloom. “When I heard you on the radio,” she asserts, “I said, by God, Umm Mustafa, this Gamal has avenged you and eased our hearts; so I am giving you this robe because you are most deserving of it” (1996, 119–20).

Fig. 3. Nasser (Ahmad Zaki) praying for the nation in Nasser 56. Courtesy of Arab Film Distributors.

[Full Size]

These scenes, products of the screenwriter’s creative imagination, encapsulate persistent popular memories of Nasser as populist hero, the man of the people. Allen Douglas and Fadwa Malti-Douglas, analyzing a comic-strip biography of Nasser that appeared several years after his death, note:

They could easily be writing a contemporary script for formal and informal discussions of Nasser’s personality and legacy with Egyptians from all walks of life.Nasser’s communion with his people is so close that he shares their tragedies as well as their triumphs. He does not stand above them as all-knowing or all-wise. The Egyptian leader’s closeness to the people is further reflected in the frequent use of his first name without titles or appellatives, both by the narrator and by the people. (1994, 41)

Egyptians who lived the Nasser years, including many who spent time out of favor and in prison (although less so those who suffered economic dislocation), still speak with exceptional warmth about Nasser. Grand politics, successes and terrible failures aside, they recount seeing him walking the streets or driving unguarded in his car. They rarely, if ever, stopped to greet him, but, more important to their personal rescripting, feel they could have. In much the same fashion, Mahfuz ‘Abd al-Rahman has described Nasser as “a man of the utmost simplicity and modesty,…a man of simple dreams,” for whom “the pleasures of life consisted of olives and cheese, going to the cinema, listening to Umm Kulthum” (1996, 6–7), a man who “could not comprehend a home with two bathrooms,” let alone a private pool (pers. com.). In interviews Ahmad Zaki, whose career blossomed at the tail end of the 1960s, has spoken of Nasser as a father figure (Ramadan 1995).

The very depiction of Nasser, albeit imaged as Ahmad Zaki, startles. For nearly two decades his likeness was everywhere, and he remains the symbol of the iconized Arab ruler (Ossman 1994, 3). But those images came down in rapid succession following Sadat’s ascension to power. Where they could not come down, as at the rarely visited monument to Soviet-Egyptian friendship at the Aswan High Dam, Nasser’s profile was all but hidden by a superimposed image of the inheritor. Private establishments still display personal icons, and one bust remains in an arcade in downtown Cairo. Once the heart of the cosmopolitan city, the area is now primarily shopping turf for the lower middle class, and the arcade is particularly rich in its selection of conservative headwear for women. There is no designated monument to Egypt’s most significant ruler of this century, no stadium, airport, public building, or major thoroughfare that bears his name (a Nile-side boulevard running through Imbaba officially does, but it is universally referred to as Nile Street). Nasser’s tomb, unlike Sadat’s, is not visited in any official commemorative capacity. There is a Nasser subway stop, but it is adjacent to a fading city center, one that is not heavily used.[9]

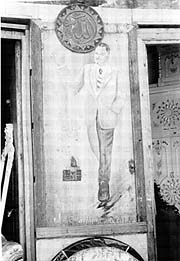

Fig. 4. The iconic Nasser outside a corner shop in a popular district of Cairo. Photograph by Joel Gordon.

[Full Size]

Nasser’s name still evokes great passion, and approbation is by no means universal or unequivocal. Like any regime seeking to foment and sustain a revolution, the Nasserist state razed before building, disrupted lives and careers of opponents, and devoured some of its own. The legacies of Nasserism remain multiple and will be weighed differently by different generations, proponents of different political and social trends, sons and daughters of different social classes. Nasserism is held accountable by some for virtually every social ill facing the nation, from traffic snarls and pedestrian anarchy to the fall of social graces. Nasser has been accounted a traitor by Islamists, a prisoner of his class by leftists, a tinhorn tyrant by scions of the old parties and aristocracy. The Nasserist political experiment is widely accepted to have failed in its stated goal of restoring a “sound” democracy. Arab Socialism, the economic strategy that produced nationalization and the creation of a vast public sector, will continue to polarize Egyptians, although the debate may increasingly turn on intentions versus consequences.[10] Nasserist foreign policy, Arabism and nonalignment, the conflict with royalist neighbors and Israel, also polarizes, and the generation that lived the period will always live in the shadows of Yemen and June 1967.

As the era grows more distant, historical perspective may help to contextualize the logic of certain directions and policies. Greater historical focus has already produced notable changes in the ways in which Nasserism has been envisioned—and debated—in the quarter century since Nasser’s death. Yet, contrary to Bodnar’s (1992, 13–19) thesis—which may well hold for his American context—in which vernacular traditions gradually become subsumed into an official text, in Egypt, and presumably in other countries where an official discourse quickly and effectively silenced all others, the process seems to be going in the opposite direction. Vernacular discourses, allowed a voice after two decades, quickly drowned out the official text, leaving public memory of Nasserism very much up for grabs.

Nostalgia in Egypt today is a complex phenomenon. The majority of the population was born after 1967, and many after Sadat’s assassination in 1981. Less than Nasser’s shadow, they have grown up in a society in which popular memory is dizzyingly multivocal. In the past two decades, during which Egyptians have been free to openly debate their history, vernacular antihistories related by representatives (some self-styled) of old-regime parties, royalists, leftist movements, and the Muslim Brothers have emerged from the underground to become standard counterorthodoxies to the official Nasserist account of the revolution. Those affiliated with the Sadat regime comprise another orthodoxy caught between competing prior legacies. The Nasserist response, official and not, has become just another vernacular tradition competing for public memory.

Ten-year anniversaries, by their very nature as discrete constructs to mark and evaluate the passage of time, provide a convenient referent. In July 1972 the country still grieved Nasser’s passing yet applauded Sadat’s dismantling of the state security apparatus, the release and welcome home of political prisoners and exiles, and the purging and incarceration of those who had dominated the “centers of power” (marakiz al-quwwa). Ten years later, when the revolution turned thirty, Egypt again faced a change in leadership, power having been transferred suddenly in a moment of national crisis. A new regime now curried favor by opening political prison doors, by prosecuting a new cohort of power abusers, and by lending freer rein to opposition voices to speak, write, and ultimately participate in government. One consequence was a frank and multivoiced discussion of the political origins of the Nasser revolution, before and particularly after the July coup. The focus remained political, the general assessment of Nasserism critical, intensified by recollections of a period, 1952–55, when the officers squandered much of the goodwill that greeted their takeover and imposed their revolution by coercion more than charisma (Gordon 1992).

As the revolution turned forty, a pronounced shift in emphasis was under way. The exploration ten years earlier into political failure had been fueled by hopes of a truly broadened liberalism. By the early 1990s much of that hope had turned cynical. To a society riven by malaise, and at times and in certain places by interconfessional strife, Nasserism has increasingly come to represent an era of hope, unity, national purpose, social stability, and achievement. This was reflected in sentiments voiced on the street as well as in the press, official and opposition, where a growing number of Egyptians recalled a society in which there was a shared sense of community in which common, enlightened aims predominated and in which religion did not create barriers (Gordon 1997b).

Underscoring this nostalgia, and recalled increasingly by Egyptians, are recollections of a golden age of popular culture. The Nasserist state promoted and subsidized cultural production on many levels: classical Western dance and music, folklore, history, cinema, theater, radio and television drama, fiction, poetry, comedy, the fine arts. In retrospect much of it may have been hackneyed, too ideologically grounded, too often in the hands of bureaucrats rather than creative artists, some of whom left the country. Yet such assessments beg the issue of nostalgia. The faces and voices of popular movie stars and singers from the 1950s and 1960s—Fatin Hamama, ‘Abd al-Halim Hafiz, Rushdi Abaza, Shadiya—have become deified. Film classics by Salah Abu Sayf, Kamal al-Shaykh, or Barakat—before and after nationalization—and even the B-films of Niyazi Mustafa and Hilmi Rafla will never be equaled.[11] Nor will the lyrics of Salah Jahin, Ahmad Shafiq Kamil, and ‘Abd al-Rahman al-‘Abnudi, paired with tunes by Kamal al-Tawil, Muhammad al-Muji, and Baligh Hamdi. These sentiments are echoed even by many who are otherwise highly critical of Nasserism and work to undo its economic and political legacies.[12]

The author of Nasser 56 is quick to assert that he never has been a Nasserist. A secondary-school student with leftist links in 1952, he mistrusted the officers’ motives and demonstrated against the regime. He never joined the party in any of its guises, even though he worked for the state media, and remains critical of the political order Nasserism fostered. Yet, like most of his generation, ‘Abd al-Rahman was consumed with a desire for social justice and a dream of Arab unity—and was captivated by Nasser’s charisma. He admits to being dazzled by his subject in ways unfamiliar to him:

Implicit in the family scenes, the images of simplicity, Nasser’s meals of cheese and olives or Mahmud Yunis sleeping on his office floor, the scenarist seeks to recapture and reimpart a sense of what Egypt was and has lost.I have written about dozens of historical figures from ‘Amru al-Qays to Baybars, from Qutuz to al-Mutanabbi and Sulayman al-Halabi. In drawing close to each of these characters I have always entered into a dispute with them, primarily because we are bound by our own era and circumstances.…What is strange is that when I wrote about Gamal Abdel Nasser the opposite occurred.…[I]t was when I tried to come to know Gamal Abdel Nasser as a person that I became so moved. It was not the oft-told stories that affected me so much as the little tangibles. (1996, 6–7)

Mahfuz ‘Abd al-Rahman, like others of his generation, those who came of age under Nasserism, is rescripting the period with a focus on an enlightened community rooted in twin notions of progress and independence. His other great project in recent years has been a major revision of Khedive Ismail (1865–79), through the vehicle of a television serial that has aired over three Ramadan seasons, the prime month of television viewing (Abu-Lughod 1993b; Gordon 1997a). Bawwabat al-Halawani (Halawani’s Gate) spins a tale of court intrigue that revolves around the romance between the musician ‘Abduh al-Hamuli and his protégée Almaz, a poor girl taken from her parents and brought up in royal circles. But the backdrop is Ismail’s desire to modernize his country, the financial and political costs incurred, and, ultimately, the Suez Canal. Dismissed by much of Western scholarship and Nasser-era history as a foolish spendthrift who, entranced by Westernization, broke the state, Ismail emerges under ‘Abd al-Rahman’s pen as a Renaissance man, a prisoner not of false illusions but of an international power structure that will ultimately not permit an independent Egypt.[13] In many ways the two projects, Nasser and Ismail, go hand in hand. Whatever their failings and failures, both leaders promoted cultural enrichment as a means toward liberation, and both ultimately confronted forces larger than they or Egypt.

Both projects also promote a paradigm that the state, for slightly different reasons—and obviously with less comfort in the case of Nasser—finds acceptable and beneficial in its confrontation with its most powerful vernacular challenge, Islamism. Egyptian television has always served to “produce a national community” (Abu-Lughod 1993b, 494). Yet, as Lila Abu-Lughod and others have noted, in recent years television serials (and the cinema) have become rostrums in “the most pressing political contest in Egypt…the contest over the place of Islam in social and political life” (1993b, 494). Long ignored, strikingly absent from drama that purportedly depicted contemporary society, Islamist characters have become almost stock figures in television serials and the subject of one major motion picture, Al-Irhabi (The Terrorist; Jalal 1994; see Armbrust 1995). Always militant—and misguided—they generally meet unhappy ends at the hands of their “brothers” after recognizing the error of their ways.[14]

‘Abd al-Rahman’s reexamination of the past has always been a personal search for the drama inherent in the historical moment (‘Abd al-Rahman 1991). His work has spanned time and place, from early Islamic Iraq to modern Egypt. For him the dramatist has freedom to explore questions the historian cannot, but the dramatist must be bound by the historian’s reliance on evidence. He is an indefatigable researcher who has battled both stolid academics, wary of the writer’s craft, and, at times, popular historical and literary wisdom, against which his scripts have rubbed. ‘Abd al-Rahman’s favorite anecdote involves a particularly obdurate actor who, protective of his good-guy popular image, refused to play a brother of the legendary Arab hero ‘Antar ibn Shadad, even though the script, which he had not read, revised the role, portraying the brother in a much more sympathetic light.

At the same time, like others who maintain intellectual independence yet work in or for the state-run media, ‘Abd al-Rahman participates in “a shared discourse about nationhood and citizenship” (Abu-Lughod 1993b, 494) and thus represents at once a personal and quasi-official voice. To champion Ismail is, in today’s discourse, to counter the Islamist claim to authenticity, one that would view Ismail’s Westernization as anathema. Likewise, to script Nasser at Suez, to depict such a powerful moment of national unity, serves, among other things, to counter social trends that are nationally divisive, even “un-Egyptian.” It is notable that the original cast of characters out of which the Nasser film emerged included products and leading champions of Westernization: Rifa‘ al-Tahtawi, ‘Ali Mubarak, and Taha Husayn.

This is not to suggest that state production officials who backed the project, or the creators, envisioned it consciously as a weapon in the battle against Islamism. At the same time, the green light to make a film about Nasser, and one of such scale, could not have been given without serious consideration. Support for the film clearly represented a gamble—that viewers would rally around the moment, rather than the figure, and that the moment, one of national unity in the face of specific historical foreign aggression, would not transcend historical time/place to mirror more recent national struggles with foreign creditors (World Bank, International Monetary Fund), struggles in which the government in its drive to privatize the economy is often portrayed as serving personal and foreign interests. What government officials obviously did not bank on was the degree to which the film, by so powerfully imaging the crisis, the personalities, the national moment, would underscore present-day malaise and popular perceptions of their own inadequacies—and, ultimately, the degree to which the film would resurrect the image of its hero.