Making Darkness Visible

Capturing the Criminal and Observing the Law in Victorian Photography and Detective Fiction

Ronald R. Thomas

In photography, process reproduction can bring out those aspects of the original that are unattainable to the naked eye yet accessible to the lens, which is adjustable and chooses its angle at will. And photographic reproduction, with the aid of certain processes . . . can capture images which escape natural vision.

Walter Benjamin

Sherlock Holmes, whom Watson refers to in the first tale of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes as "the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has ever seen," exemplifies the essential Victorian hero who is known above all for his virtually photographic visual powers—the literary detective.[1] The detective's unique talent is an uncanny ability to see what no one else can see, to "capture images," as Benjamin says of the technology of the camera, that otherwise "escape natural vision."[2] Holmes has this power, he tells Watson, because of his specialized knowledge: he knows where to look and what to notice. "You appeared to read a great deal in her which was quite invisible to me," Dr. Watson notes characteristically to Holmes just as the great detective reveals his observations about a client. "Not invisible but unnoticed, Watson," Holmes replies. "You did not know where to look, and so you missed all that was important."[3] What we see, Holmes says, is governed by conventions, which make portions of the world visible to us and determine what is worth our attention (and what is not). The trained eye of the great detective alters those conventions of vision and exposes to us, as Holmes does to Watson and his clients, what had previously been hidden from view. Like another remarkable Victorian

visual apparatus, the camera, we might think of Holmes (and the "sharp-eyed" detectives he represents) as the literary embodiment of the elaborate network of visual technologies that revolutionized the art of seeing in the nineteenth century. Just as the popular iconography of Sherlock Holmes invariably identifies him with the magnifying glass, he and these other literary detectives personify the array of nineteenth-century "observing machines" (from the kaleidoscope to the stereoscope to the camera itself) that made visible what had always been invisible to everyone else.

The camera, John Tagg contends, "arrives on the scene vested with a particular authority to arrest, picture and transform daily life; a power to see and record"—a claim that might be applied with equal accuracy to the simultaneous arrival on the cultural scene of the literary detective.[4] Together, camera and literary detective developed a practical procedure to accomplish what the new discipline of criminal anthropology attempted more theoretically: to make darkness visible—giving us a means to recognize the criminal in our midst by changing the way we see and by redefining what is important for us to notice. Not only did the literary detective and the camera shape the emerging science of criminology and the techniques that made the criminal mind visible to the public eye, but they also played an important role in the process Jonathan Crary calls "a complex remaking of the individual as observer into something calculable and regularizable and of human vision into something measurable and thus exchangeable."[5] In that process, the mechanism of the camera became one of the detective's primary means for identifying a suspect and defining that suspect as an observed object as well as an observing subject, whose normalcy or deviance could be perceived and managed in the eye of a machine. Focusing on the uses of photography in Bleak House and in the first tale in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, I explore in this essay the implications of the remarkable correspondence between the history of the camera and the history of the literary detective in nineteenth-century England to understand how those converging histories rendered persons both visible and invisible, observers and observed.

When Holmes bewilders Watson (as he constantly does) by looking at his client—or at a suspect, or at the scene of a crime, or even at Watson himself—and seeing things invisible to everyone else, Holmes typically responds to his partner's demands for an explanation by asserting, "I see it, I deduce it."[6] Holmes's vision, that is, is not innocent or objective, but is "deduced," reasoned out, rationalized, managed. It is the product of a certain way of knowing. "You see, but you do not observe,"

Holmes reproves Watson. "I have both seen and observed" (11–12). In what Holmes sees, and in what he deems important, the master detective teaches us (as he teaches Watson) not just to see, but to "observe"—in the sense of "observing" the law, that is, conforming to certain ways of seeing. Holmes, and others like him, enable us to see through their powerful lenses—the lenses, we might say, of their cultural power and authority. While these detectives train us to see as they do, subjecting us to a process of constant visual correction and to their own superior visionary powers, they must also remain uniquely privileged sites of vision themselves. To that end, the regime of visual correction they impose upon us involves the validation of photography as a technique of surveillance and discipline, an endorsement that may well have led to the widespread deployment of photography in actual nineteenth-century police work and to the transformation of the camera from an artistic device for portraying and honoring individuals to a powerful political technology with which to capture and control them.

In 1841, slightly more than a year after Louis-Jacques Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot each announced the invention of the modern process of photography, Edgar Allan Poe "invented" the modern detective story and published the first of its kind ("The Murders of the Rue Morgue"). In the intervening year, just before he wrote his famous series of three detective stories, Poe published three essays on photography, two of them in the same magazine in which "The Murders of the Rue Morgue" would later appear.[7] In the first of these essays, Poe proclaimed photography "the most extraordinary triumph of modern science," a form of representation that far superseded language in approximating reality itself and achieving "a perfect identity of aspect with the thing represented."[8] For Poe, the photograph did not simply represent its subject; it attained an ontological equivalence, a "perfect identity" with its referent. But in fact, as the use of photography in detective fiction often makes clear, a photograph can completely redefine the identity of its subject, depending on how the photograph is composed and viewed. Poe's own fictive "observing machine," Auguste Dupin, demonstrated this principle clearly when, through the lenses of his distinctively tinted green spectacles, he alone was able to see the purloined letter that had been hidden in plain view in the lodgings of the ambitious politician who stole it. Dupin's all-seeing gaze, itself obscured from the sight of others by those tinted lenses, detected what had been invisible to everyone else and brought to light what was determined to be absent from the minister's rooms.[9] Dupin knew that the solution to this political

crime was deeply related to the fact that some things "escape observation" only by being "too obtrusively and too palpably self-evident."[10] In his eyes and through his lenses—as if through the lens of a camera—this escape route is revealed and the surface of things is recaptured and re-presented to us for a more careful scrutiny. Holmes's frequent admonitions to Watson only substantiate Dupin's claim and validate his example, reminding us that what we see in a photograph—what is visible to us there as anywhere else—depends on where we look and on what we notice, on the ideological interests with which we view it and establish (in Holmes's words) what we deem important about it.

When the figure commonly regarded as the first detective in the English novel appears for the first time in Dickens's Bleak House, his gaze seems to substantially transform the field of vision upon which it falls, much as Dupin's had done a decade before.[11] Mr. Bucket emerges magically in the pages of Bleak House out of the darkness of a lawyer's rooms in a flash of light and in an explicably "ghostly manner," looking, to the hapless man he was scrutinizing and interrogating, "as if he were going to take his portrait."[12] "Appearing to [Mr. Snagsby] to possess an unlimited number of eyes," the detective Mr. Bucket seems to those on whom he looks to "take" their portraits instantaneously through his powerful lenses, a perfect description of what only the revolutionary new machine called the camera was capable of doing (281). As if to reinforce the comparison, once he takes Snagsby's measure in this scene, Bucket arms himself with a bull's-eye lantern and conducts the bewildered man through the darkened streets of Tom-All-Alone's in search of a boy, flashing his light on a series of faces, ruins, alleys, and doorways, creating the equivalent of flash photographs of these scenes of urban blight, just as he had done earlier when he seemed to take the portrait of Snagsby himself (Fig. 48). The photographic analogy is further substantiated when Bucket finally "throws his light" on the paralyzed Jo, who "stands amazed in the disc of light, like a ragged figure in a magic lanthorn" (280).[13] When the detective mysteriously appears yet again, at the Bagnet household to arrest Mr. George, Bucket is described once more in terms that call to mind a photographic mechanism: "He is a sharp-eyed man, a quick keen man—and he takes in everybody's look at him, all at once, individually and collectively, in a manner that stamps him a remarkable man" (593).

This power to look at and to take in the look of everyone else in a flash of light stamps Bucket as remarkably like the new portrait cameras that were beginning to appear everywhere in England at the time Bleak

House was being written. They proliferated so rapidly because of an important technical development in the photographic process. According to Beaumont Newhall,

a new era opened in the technology of photography in 1851, with the invention by Frederick Scott Archer, an English sculptor, of a method of sensitizing glass plates with silver salts by the use of collodion. Within a decade it completely replaced daguerreotype and calotype processes, and reigned supreme in the photographic world until 1880.[14]

Invented in the year before Bleak House began publication, this new wetplate process moved photography solidly into the commercial world (Fig. 49), as innumerable high-quality prints could now be made from a single negative (the daguerreotype process required a different exposure for each print). Such an advance in technology not only made portraits quicker and cheaper to produce but also made possible two Victorian photographic sensations that had far-reaching sociological implications: the carte de visite (a personal photographic calling card) and, later, the larger-format cabinet photograph (in great demand at first for theatrical professionals' publicity photographs and later adopted by the general public). Both of these forms of mass-produced portraiture became popular among the middle classes, widely distributed to friends, avidly collected, and proudly displayed in family albums as substitutes for the more costly oil portrait, commissioned only by members of the wealthiest and most fashionable families. As a result of this emerging photographic technology and its attendant commercial products, then, the personal portrait was rapidly transformed from a sign of aristocratic privilege and wealth to a mode of middle-class commercialism and entertainment.[15]

The historical coincidence of the invention of this technology with the appearance of the literary detective is important; more telling, however, is the description of the first police detective in the English novel in terms of this particular technology. The detective appears in the Victorian popular imagination, that is, looking like a camera. As Sherlock Holmes and the others who followed Bucket would confirm, the detective as a popular literary hero promoted the notion of photography as a benign form of police work. But the resemblance between the function of the literary detective in the novel and that of the portrait camera carries with it a hidden threat to personal privacy as well as a clear benefit to public safety. In the person of Mr. Bucket, photography is implicitly represented not simply as an instrument for artistic representation or as a remarkable scientific achievement, but also as a technology designed

for surveillance and control, a technique with which to arrest its subject. When Bucket, who is able to be everywhere at once and to take in everyone instantaneously in his "unlimited" gaze, "mounts a high tower in his mind" and gazes across the landscape, he is like a powerful camera, taking the portraits of all those he sees and carrying the prints with him wherever he goes (673). Long before mug-shot files or rogues' galleries became part of the customary ritual of criminal investigation and identification in police departments, Mr. Bucket seems to have established such an archive in the photographic portrait gallery of his mind. "He has a keen eye for a crowd," the narrator informs us; and as Bucket "surveys" the details of the city scene in search of a suspect, the narrator indicates that the detective gazes with special interest "along the people's heads" that fill it, and that "nothing escapes him" (627).

The "taking" of portraits plays an important part in the mystery surrounding the true identities of Esther Summerson and Lady Dedlock in Bleak House and in the investigation conducted by one of Mr. Bucket's amateur-counterpart detectives, Mr. Guppy. The first evidence we have of the filial relationship between Esther and Lady Dedlock, in fact, is provided by Lady Dedlock's portrait. Guppy's initial glimpse of it during his tour of the Dedlock estate in Lincolnshire causes a spark of recognition, provoking the law clerk to ask the servant conducting the tour whether the portrait has ever been engraved—whether, that is, it has ever been mass-produced for public consumption (82). Indeed it has not, he is told; many have asked to engrave it, but all have been firmly refused. Still, "how well I know that picture," Guppy persists. "I'll be shot if it ain't very curious how well I know that picture" (82). Though this is his first visit to the Dedlock estate, Guppy cannot be persuaded that he has not seen this portrait somewhere before. "It's unaccountable to me," he insists; "I must have had a dream of that picture." It is as if the amateur detective, Mr. Guppy, possesses a degraded version of the professional detective's photographic powers, his unconscious operating like a primitive camera producing blurred and unfocused images in his memory. The special function of the professional, Bucket, is to bring that unconscious power into consciousness, making clearly visible to Guppy (and to us) the images and relations seen formerly only through a glass, darkly.

Indeed, those very images will prominently reappear later in Guppy's investigation of Lady Dedlock and her relation to Esther Summerson. When Guppy's collaborator Mr. Jobling (also known as Weevle) takes up residence at Krook's shop to spy on him, Jobling decorates his room with copper impressions of fashionable ladies, pictures taken from a vol-

ume called The Divinities of Albion, or Galaxy Gallery of British Beauty . Among this august collection, it turns out, is a reproduction of Lady Dedlock's portrait. That portrait, since it has presumably not been engraved, may have been reproduced by some primitive photographic process. Indeed, copper plates could be made at this time by using an early photographic technique. But regardless of how this reproduction has been made or where its original came from, its presence in Jobling's rooms indicates that Lady Dedlock's image was "shot" and escaped her own control once it was disseminated into the world as public property. Mechanically reproduced and publicly displayed, that portrait, as honorific as its original may have been intended, now not only threatens Lady Dedlock's privacy but also usurps her control over her secret identity. Guppy's inexplicable familiarity with the original portrait of Lady Dedlock stems from his seeing Esther in it; but he may also presciently see Lady Dedlock's photograph in Lady Dedlock's portrait . If so, what he sees in addition, but resists recognizing, is the dissolution of the "aura" of "authenticity" and privilege (in Benjamin's terms) inscribed in her aristocratic identity. Whether Guppy knows it or not, in his eyes and on Krook's walls the portrait becomes a mug shot, a wanted poster that silently announces Lady Dedlock's dark past and Sir Leicester's unfortunate fall as Bucket will publicly announce them later on.

This visual representation of Lady Dedlock is, then, more threatening to her station than the much dramatized fear surrounding the discovery of her handwriting and signature as they appear in the lost letters to Captain Hawdon, letters relentlessly pursued by Guppy and Jobling, Krook, Tulkinghorn, and Smallweed and finally confiscated by Mr. Bucket himself "That's very like Lady Dedlock," Guppy says to Jobling of her gallery portrait. "It's a speaking likeness," he adds (396). And when Jobling chimes in, jokingly, that he wishes it really were a speaking likeness so that they could have some fashionable conversation with it, Guppy reprimands his friend for being flip and insensitive to "a man who has an unrequited image imprinted on his art" (397). Although the more dispassionate professional detective Mr. Bucket has mastered better than Guppy the technology of mentally imprinting images, even he is deceived later in the novel (at least momentarily) when Lady Dedlock assumes the appearance of a laboring woman and thereby temporarily eludes his gaze. For his part, Guppy's outrage at the lack of respect shown Lady Dedlock's portrait predicts what his friend's picture gallery reveals—that the conventions of class distinction as a social mechanism by which to authentically identify persons are an illusion. Or so we must infer when Guppy concludes the "taking down" of the portrait of Lady

Dedlock from his partner's wall, clutches the copy in his hand, and proclaims that he has taken down its original a peg or two as well: referring to this "divinity" now as no more than a "shattered idol," he identifies the image he holds in his hand with his newly found power to "associate" himself with a previously unreachable class of people. "Between myself and one of the members of the swanlike aristocacy whom I now hold in my hand," he says, "there has been undivulged communication and association" (495). The "Galaxy Gallery," like the rogues' gallery that would follow it (Fig. 50), renders the portrait degraded graffiti for the decoration of a bureaucrat's rooms and the exposure of criminal minds. The movement in the novel from the oil portrait of Lady Dedlock proudly hung in her estate to the mass-produced plate of that portrait printed in a magazine to an image pasted on the wall of a law clerk's rooms recapitulates the nineteenth-century transformation of portraiture from an authentic sign of aristocratic status to a mechanical image of middle-class self-representation and, finally, to a clue for criminal investigation.

"Photography," Benjamin would say in his famous essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," "can bring out those aspects of the original that are unattainable to the naked eye yet accessible to the lens," and "can put the copy of the original into situations which would be out of reach for the original itself."[16] This fate, of course, is precisely that of Lady Dedlock's portrait in Bleak House . As I will explore more extensively later in this essay, it is also the presupposition upon which photography was eventually appropriated by criminologists to understand the criminal mind as well. Furthermore, as Benjamin argues, the "aura" of the original work of art was fundamentally challenged by a mechanically reproducible art like photography, bringing into question the cultural value invested in the whole concept of authenticity . "The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity," Benjamin says, and since with the advent of photography any number of prints can be made from a single photographic exposure, the idea of the "authentic" print ceases to make any sense (222–24). The association of the printed portrait of Lady Dedlock with her class status (eventually determined to be "illegitimate"), means that what is true of the "authentic" original work of art is also true of the "authentic" noble classes it represents. Benjamin suggests as much when he claims that "the instant the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production, the total function of art is reversed" from a social practice based on ritual to another kind of social practice—one based on politics (224). The replacement of the fashionable family solici-

tor and confidant in the Dedlock household by the police detective and informant registers that reversion from social ritual to political action. As an agent of the state, Bucket is explicitly invited to be a spy in the Dedlock home, a function Tulkinghorn had taken on surreptitiously in his ritualistic role as family counselor.

In the case of detection that eventually comes to dominate the plot of Bleak House, the threat of Lady Dedlock's duplicated image to the aura of the ancient Dedlock family is as great as that of her disreputable past. The stability of authentic identity (as figured in the anxiety over illegitimacy in the novel) and of the authentic aristocratic class (as symbolized in the "plating" of the original oil portrait) comes under attack in the novel. Indeed, the court's seemingly inherent inability to determine the authenticity of the Jarndyce will only reinforces the reader's sense that traditional institutions have failed as enforcers of cultural continuity and that new structures must develop to perform that role. Standing in the place cleared by the technology of the camera, then, the detective officer Mr. Bucket enters to solve a mystery of identity when the court fails to decipher the mystery of the will. By so doing, Mr. Bucket not only represents a new cultural authority but also defines its power as springing, not from the preservation of traditions, but from the production of images. He popularizes a picture of the detective as the expert professional who authenticates what the ancient court and the traditional oil portrait are no longer empowered to authenticate, discriminating between the real thing and the impostor with his own brand of instantaneous photographic portraiture.

Bucket is distinguished not only by his eyes but also by his insistent forefinger, which, like the finger of Allegory engraved on the ceiling of the murder victim's rooms, is constantly pointing, directing others to look in a certain place, to see what he sees in the way that he sees it. The detective is more than a sharp-eyed observer; he allows, even requires, others to observe in the way he does. At the scene of the murder Bucket investigates, the figure of Allegory is described in this way: "There he is still, eagerly pointing and no one minds him. . . . All eyes look up at the Roman, and all voices murmur, 'If he could only tell what he saw'" (585). Bucket accomplishes exactly what Allegory cannot: he points out what he sees, proceeds to tell it, and commands everyone else to mind him by seeing things his way. Like the camera, Bucket is a technology not only of observation but of representation as well. So effective is his pointing finger in these linked processes that it disciplines the vision of others, constraining their eyes into a certain field, focusing them on a specific object or person or detail. "Look again," he says to Jo when the

boy identifies Mademoiselle Hortense as his mysterious female visitor (282). "Look again," he insists, as he directs Jo to look only at the woman's hands this time, then to look only at her rings, in a gradual process of zooming in and framing and focusing the field of Jo's vision, a process that causes the boy to revise his first conclusion and affirm that these are not the hands of the woman who visited him that night. Compared with the hand he looks at now, that of the mysterious night visitor, Jo decides, "was a deal whiter, a deal delicater, and a deal smaller"; and unlike the maidservant's common jewels, the lady's brilliant rings were "a-sparkling all over" (282). Bucket corrects Jo's vision so that the boy sees what he could not see before: these are working-class hands rather than the hands of gentility, and these are cheap rings rather than the precious jewelry of a lady. In the course of having his vision corrected, that is, Jo is also made to look hard at and acknowledge the signs of class difference that distinguish a mere woman from a lady, a French maid from one of the "Divinities of Albion."

Ironically, the detective seems to contradict the ideological implications of the very technology he embodies here. As the camera democratized the human image and transformed the portrait from an exclusive possession of the privileged classes to a commodity easily attainable by the middle class, Bucket's vision seems rather to reinforce the visual signs of class distinction in this scene. We might view Bucket's later failure to recognize Lady Dedlock when he pursues her with Esther through the streets of London, however, as an implicit critique of that sign system's authenticity and dependability, or at the least as an indication of its limitations. In failing to realize that the lady had simply changed clothes with a working-class woman, Bucket, like Jo in this earlier scene, wrongly assumed that the clothes make the lady, that the visual signs of gentility constitute dependable evidence of someone's identity.[17] Together, these two incidents illustrate the real force of the analogy between camera and detective: the way both signal the transformation of the visual image from a self-celebration and an index of self-proclaimed authenticity to a form of bureaucratic surveillance and identification whose decoding demands the interpretive expertise and authority of a professional. They demonstrate that what we see and how we value it result from mechanisms and conventions that can be altered as dramatically as changing a camera lens alters the field of the eye's vision.

When Mr. Bucket arrests Mademoiselle Hortense, another working-class woman who had once disguised herself as a lady, the detective is said to make "no demonstration except with the finger" as he shows the

accused murderer where to sit. "Now, you see," Mr. Bucket informs the woman he now refers to as "the foreign female," "you're comfortable, and conducting yourself as I should expect a foreign young woman of your sense to do. So I'll give you a piece of advice, and it's this, Don't you talk too much. You're not expected to say anything here, and you can't keep too quiet a tongue in your head. In short, the less you Parlay the better, you know" (648). Bucket then explains to Sir Leicester that the woman's guilt "flashed upon me, as I sat opposite to her at the table and saw her with a knife in her hand" (649). In another of those seeming flash photographs or magic lantern images that imprint themselves on his mind, Bucket sees the culprit's guilty hands in the constricted way he taught Jo to see, indicting her with his finger and silencing her with the tale that only he can tell.[18] And yet, as he speaks for the class by whom he is employed in this scene, he also speaks for the nation, projecting the guilt for the crime upon the body of the "foreign female," whose distinctively foreign manners and appearance form the visual evidence that justifies his suspicions of her. For all the complications of his character, Bucket is the single figure in Bleak House who is able not only to see through its infamously impenetrable fog, but to speak out of it as well—at once visualizing and telling the truth that otherwise mains invisible.

While Bleak House was written after the advent of photography, it is set in the decade prior to Daguerre's and Talbot's announcements of their inventions. Dickens admired photography and knew as much about it as about the detective police, even if Bucket did not. Dickens even published articles on the subject simultaneous with his publication of Bleak House . His great detective, we may argue, stands in for the dreamed-of but as yet unrealized photographic technology in the novel (as the camera and its anonymous operator replace the detective in Fig. 51). What the narrator of Bleak House says of the railroad might also be said of photography: "As yet such things are non-existent in these parts, though not wholly unexpected" (654).[19] Just as the detective's ubiquity and mobility anticipate the eventual pervasiveness of the railroad throughout the provinces, his visionary powers anticipate those of the portrait camera and the collodion photographic processes of the 1850s. "The eye," Dickens quotes a real detective as saying in a Household Words essay published the year before Bleak House, "is the great detector."[20] Dickens refines the point by adding that "the experience of a Detective guides him into tracks quite invisible to other eyes" (369). And in another piece on the subject of criminal detection that appeared in the same journal soon after the novel was published, Dickens argues that if

we were only "trained" to look correctly, we (like Bucket) would be able to recognize the criminal simply by looking at him. "Nature never writes in a bad hand," Dickens says. "Her writing, as it may be read in the human countenance, is invariably legible, if we come at all trained in reading it."[21] The detective's sharp eye and his persuasively pointing finger are the agents Bleak House offers for that training, teaching us to see the unseen in Lady Dedlock and in Mademoiselle Hortense as well, just as Bucket teaches the once-blind Esther to see the unseen when he brings her face-to-face with Lady Dedlock's corpse and points out to the daughter the body of her mother disguised as a working-class woman, lying on the grave of her nameless father. Throughout the text, Bucket's camera-eye does more than perceive and portray; it disciplines.

The transformation of the camera from an agent of celebration to one of surveillance that Dickens negotiates in Bleak House is equally detectable in his treatment of the subject of photography in the pages of Household Words around the time of the novel's publication. During the 1850s, Dickens published two essays on the topic in his weekly journal. The first, "Photography," which appeared in 1853, about midway through the monthly publication of Bleak House, contains descriptions of the photographer and his "mysterious designs" that strongly resemble those of the detective in Dickens's novel.[22] The writers of the article marveled at the achievements of this new technology, regarding it as both a magical art and a new science, dwelling on the amazing procedures by which the photographer was able to produce effortlessly "a thousand images of human creatures of each sex and of every age—such as no painter ever has produced" (54–55). The speed with which these portraits "burst suddenly into view" causes considerable awe in the authors, who affirm that it "would have given labour for a month to the most skilful of painters" to produce such results (55, 58). The preoccupation in the article with photography as an advanced form of portrait painting recalls the centrality of the portrait in Bleak House and Guppy's obsession with the image imprinted on his mind and hanging in Krook's rooms. Despite its comparisons of the photographer's magic to the portraitist's skill, however, the article also manifests something ominous about the powers of this new technology. The photographer is referred to as a "taker of men" who, when asked about the origin of all these photographs—these "innumerable people whose eyes seemed to speak at us, but all whose tongues were silent"—affirms of the subjects that "they have all been executed here" (55). Unlike the oil portrait, somehow, the photograph not only silences its subjects but takes their lives as well.

This more threatening power of the photographer becomes the focus of an article on photography that appeared in Household Words only four years later, provocatively titled "Photographees."[23] Told from the point of view of the portrait photographer, it describes the camera's various subjects—the "photographees"—whom the photographer "composes" and ranks in order of their difficulty to capture in his lens. The article culminates with a description of the portraitist as policeman, recounting the time when the photographer was engaged to shoot "the most unwilling sitters whom I ever took"—a group of prisoners from "a certain north country gaol" (354). The pictures were commissioned to assist the authorities in recovering any of the prisoners who might escape the prison; the camera was deployed to "capture" their likeness and imprison them in "a portrait gallery of felons" (354). "The photographees did not like my interference one bit," the photographer affirms. "The machine seemed to remind them exceedingly of a bull's eye lantern, to which they had a very natural repugnance" (354). Like Mr. Snagsby looking in the glaring bull's-eye of that other "taker of men," Mr. Bucket, these subjects are arrested by the eye that takes their portrait and assures their imprisonment, intuitively recognizing the executionary power this technology exerts over them.

If the first detective in the English novel is described as a camera, it was not long before the camera was described as a detective. A few years before Sherlock Holmes was introduced to the English public in 1887, a device called the "detective camera" was introduced into the market-place in England. So named because it could be hidden in a walking stick or behind a buttonhole, the detective camera could be owned and operated by anyone without subjects' even knowing they were being "taken." Some of these new handheld cameras were advertised at reasonable prices in the very magazine that first published the Holmes stories, and some were even the subject of articles in that magazine about "the curiosities of modern photography" and its use in solving crimes.[24] In the same volume of the Strand in which the first story of the Adventures was published, in fact, there also appeared an article on the "warranted detective camera," titled "London from Aloft," which hailed the machine's new improvements and looked forward to the day when "in time of war . . . one might snap the merry camera on the wrathsome foe below in all his dispositions and devices, and in good safety drop the joyous bombshell on the top of his hapless head—foresooth what fine thing must be that!" (Fig. 52).[25]

That the camera was imagined as a weapon of national defense as well as a source of truth could hardly be more graphically described than

in this instance, where the snap of the shutter gives way to the explosion of the bombshell. Also in 1887, moreover, Blitzlichtpulver —flashlight powder—was invented in Germany for flash photography, which used guncotton and magnesium powder to provide an often dangerous explosion of light. At the same time, the dry-plate, fixed-focus photographic process of the detective camera was being perfected by Kodak, replacing the wet-plate process developed in 1851 and enabling amateurs and journalists alike to take instantaneous candid snapshots of people without their consent. So widespread was the practice that eventually the New York Times was prompted to complain about the invasion of privacy from "Kodakers lying in wait."[26] In England, meanwhile, the Weekly Times and Echo applauded the formation of a "Vigilance Association" in 1893 whose sole purpose was the "thrashing of cads with cameras who go about in seaside places taking snapshots of ladies emerging from the deep."[27] Self-appointed vigilante groups were formed, that is, to police the unauthorized deployment of this policing technology. In light of this response, the term "detective camera" appeared most appropriate for these devices, since in taking someone's picture, these cameras, like the private eyes they were named after, also took possession of the subject's identity and took authority over the presentation of the self.

It is equally appropriate, then, that photographs should play a prominent role in the accounts of the greatest English literary detective. In the very first story of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes ("A Scandal in Bohemia"), the master detective is not hired to recover a missing gem, protect a threatened head of state, or investigate a murder. He is commissioned by a king to procure a photograph. The possession of the photograph is of such "extreme importance," Holmes's client predicts, that it will have a significant "influence on European history" (15). The personal photograph, this tale acknowledges, has profound historical and political implications. When the king of Bohemia appears in disguise in the beginning of "A Scandal" to request that Holmes protect him from ruin by the actress with whom the king had become romantically entangled, Holmes immediately sees through the king's disguise. He does not see, however, why the king is so concerned that the "adventuress" will blackmail him and destroy his plan to marry the princess of Scandinavia because, it appears to Holmes, this Miss Irene Adler has nothing "to prove" the "authenticity" of her claims against the king's reputation. Handwriting can be forged, Holmes assures him, personal notepaper stolen, the royal seal imitated. There is really nothing to worry about. But when Holmes learns that the king has had a photograph

taken of himself in the company of the woman in question, the detective recognizes the danger. "Oh, dear!" he exclaims. "That is very bad! Your Majesty has indeed committed an indiscretion. . . . You have compromised yourself seriously" (17).

The usually unflappable Holmes's extreme reaction to the power of the photograph to authenticate and to threaten is striking here, especially since immediately before his interview with the king, Holmes himself has (like his predecessor, Detective Bucket) been described to) us as a kind of camera. Not only is Holmes introduced by Watson in the beginning of the story as "the most perfect reasoning and observing machine the world has ever seen," but he is also identified by the doctor as a "sensitive instrument" in possession of "his own high-power lenses" (Fig. 53), which are capable of "extraordinary powers of observation" (19). It is only fitting, then, that the object of Holmes's quest in the first of his adventures should be a photograph. And it is just as appropriate that at the conclusion of his investigation Holmes should request of his royal client another photograph (of Irene Adler alone in evening dress) as payment for his services. The purpose and the end product of the detective's labor, in other words, are equated in this tale with the purpose and end product of the camera.

What is it, then, that this powerful, personified camera "sees" and fears in the photograph he sets out to take on behalf of his client? Paradoxically, not only does Holmes recognize the photograph as a piece of incontestable evidence, as a genuine index to truth and "authenticity," but he also perceives it immediately as a powerful weapon with which the truth can be manipulated. "The photograph becomes a double-edged weapon now," he observes to Watson when he learns of Miss Adler's sudden marriage to an English lawyer named Godfrey Norton. "The chances are that she would be as averse to its being seen by Mr. Godfrey Norton, as our client is to its coming to the eyes of his Princess. Now the question is—Where are we to find the photograph?" (25). Even if Irene Adler's new circumstances make her prefer to suppress rather than reveal the photograph in question, the picture remains a dangerous weapon, and the king is still willing to "give one of the provinces of my kingdom to have that photograph" (18). The king realizes that this image of himself must be possessed so that it can be disowned. He is convinced that the history of Europe is at stake. In a narrative in which no one is quite who they appear to be, where the client, the detective, and the suspect all wear disguises, this ultimate visual index of"authenticity" can be deployed as a deceptive weapon. It must be bought, Holmes first recommends when he learns of Miss Adler's possession of

the photograph; failing that, he says, it must be stolen. Even if this particular picture is no longer a direct threat against his client, Holmes knows that whoever possesses it controls the truth—and can thus influence the course of history.

When Holmes first considers the photograph the king engages him to retain, before even seeing it he realizes that, like him, it represents a powerful representational technology. It may stand at once as a proof of "authenticity" and as a "weapon" of manipulation that gives its possessor significant power. But in the other photograph of Irene, which replaces the first, he sees exactly what the king sees—the woman. He sees the essential qualities of the feminine captured in a single image. "To Sherlock Holmes," Watson begins the narrative cryptically, referring to Miss Adler as the subject of this photograph, "she is always the woman." Irene Adler holds this privileged place for Holmes, we are led to believe by Watson, because the great detective who spurns all emotional involvement is romantically attracted to her—and only to her. This attraction explains why in the first of the adventures, Holmes uncharacteristically fails to attain his objective and is deceived himself. Emotional involvement produces "grit in a sensitive instrument" like Holmes, Watson tells us, "or a crack in one of his own high-power lenses" (9). This is why "A Scandal in Bohemia" is the exception that proves the rule of the great detective's infallibility, and why, having been outwitted by Irene Adler, Holmes henceforth remains a resolutely cold and unemotional "machine." But such an explanation only begs the question. Why is Irene Adler the sole woman to catch Holmes's eye (and put the crack in his lens)? Why does she stand for "the woman" in his mind?

Irene Adler has this power for the perfect observing machine because for him she is first and foremost a photograph. Or, to be precise, she is two photographs: the one Holmes was hired (and failed) to obtain and the one he requests (and receives) as payment for his services. Irene Adler outwits Holmes by substituting the second photograph for the first. Since for Holmes, she was said to always be the woman, it is only right that she should deceive him and foil his plan by disguising herself as a man, thereby forcing the detective to give himself away unawares. Irene is a threat not only because she is a commoner who can embarrass royalty, but also because she is the woman who can be mistaken for a man—because she challenges the detective's perceptions of her and her conformity to certain gendered codes of behavior. As Bucket is deceived for a moment by a lady's disguise as a laborer, Holmes is momentarily deceived by a woman's disguise as a man. That brief lapse foils Holmes's

whole plan of attack and denies him the photograph he originally set out to possess.

In the course of explaining his plan for solving the case to Watson, Holmes indicates that he knows exactly how women behave, and that this knowledge is the basis of his entire strategy: they are "naturally secretive," he declares to Watson, and this distinctively female characteristic will trick Irene into showing him where she has hidden the photograph. "When a woman thinks that her house is on fire, her instinct is at once to rush to the thing which she values most. It is a perfectly overpowering impulse, and I have more than once taken advantage of it" (28). Holmes concocts his scheme, confident that women are perfectly predictable creatures ruled by instinct and impulse, fundamentally unlike the men who know how to take advantage of these traits. When Irene appears at Holmes's own front door dressed as a young man in a coat and hat rather than as a woman in evening dress, therefore, Holmes literally does not see her. He observes her but he does not see her, because he observes the visual laws that prescribe the way a woman should appear rather than describe the way she is. Holmes had reasoned that a cabinet photograph of the kind he sought was too large to be hidden on Irene Adler's person. So large did the image loom in his mind, it would seem, that he sees only the photograph when he should be seeing her body. As it turns out, the photographic image was not hidden on Irene's body; her body itself was hidden (at least from Holmes) by the photographic image of her as "the woman" as it was imprinted on his mind.

When Irene Adler foils Holmes's plan to recover the photograph and sneaks away with it, she leaves behind a note that explains how she fooled him into giving himself away. "Male costume is nothing new to me," she says. "I often take advantage of the freedom which it gives" (31). "As to the photograph," she goes on to explain, "I kept it only to safeguard myself, and to preserve a weapon which will always secure me from any steps which he might take in the future." Like male costume, the photograph that puts the woman in the same frame with the king serves as a cloak of freedom for her. But the resourceful actress also leaves behind for the king this other photograph "which he might care to possess"—the one of herself in evening dress. It is Holmes, however, not the king, who wants this picture of the woman alone in what we might call "female costume." In this photograph, Irene Adler may be safely captured as the more predictable feminine sexual object Holmes imagines (and desires) her to be. "This photograph," Holmes says, he "should value even more highly" than the crown jewels the king offers

him in payment for his troubles at the end of the case. If the first photograph in the case is a weapon Irene Adler will use to safeguard and secure herself, this second photograph is a weapon Holmes can use to safeguard and secure his image of the woman. "And when he speaks of Irene Adler, or when he refers to her photograph, it is always under the honourable title of the woman," Watson repeats in the tale's final sentence. For Holmes, that is, the photograph does not just represent the woman; it is the woman. Tucked away in his file, the photograph becomes a replacement for the person. But this photograph is also a reminder to us, if not to Holmes, that the Victorian ideology of gender blinded even the most perfect observing machine in the world, that it produced limitations on vision that even Holmes had to "observe."[28]

In many of the Holmes stories that follow "A Scandal in Bohemia," photography figures prominently as a means to secure an identity, unmask an impostor, or substantiate an accusation in "The Man with the Twisted Lip," "Silver Blaze," "Yellow Face," and "The Cardboard Box," for example. Fittingly, however, in the first story of the last Holmes volume, The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes, a photograph of a woman is once again the object of Holmes's investigation, and once again photography is acknowledged not only as a form of evidence but also as a weapon of manipulation. As in the earlier case, Holmes is hired to defend the honor of a royal client who wishes to remain anonymous. But "The Case of the Illustrious Client" offers an ironic commentary on its predecessor, for in the later case the avid collector of photographs is neither the detective, nor the client, nor the police but an internationally renowned criminal—"the Austrian murderer," Baron Gruner. Among the cruel man's vices, it seems, is womanizing, an activity Gruner records in a book of photographs. "This man collects women," we are told by one of his victims "as some men collect moths or butterflies. He had it all in that book. Snapshot photographs, names, details, everything about them."[29] Just as police departments and detective agencies were assembling books of criminal mug shots to aid their investigations, this criminal keeps an archive of his illustrious victims' portraits, which he uses to blackmail the women once he has disposed of them. "The moment the woman told us of it," Holmes says of this book of photographs, "I realized what a tremendous weapon it was" (998). In this case the weapon of photography is aimed at the British royal family rather than a European monarch, and at the risk of his own life Holmes rescues that weapon from foreign hands. Whereas "A Scandal in Bohemia" threatens Holmes's reputation by handing him one of his rare defeats, this other case threatens his very life when his snapshot-collecting

antagonist seriously wounds him. In both cases, however, the detective is hired to obtain photographic evidence for "an illustrious client," aligning himself with the interests of an ancient nobility by getting control of a modern technology.[30]

In these foundational texts in the history of Victorian detective fiction, photography both observes and defends late-nineteenth-century European class privilege (as Lady Dedlock's portrait becomes a clue in the detection of her common "criminal" past) and gender difference (as Irene Adler challenges Holmes's "natural" categories of differentiation between men and women as exhibited in her photograph, even as she threatens European royalty). Realigning the framework of patriarchal power and defining themselves as the rightful replacements for debased legal authorities, Bucket and Holmes represent new forms of privilege and power, qualities invested now in a class of professionals (like themselves) who are legitimized by their expertise rather than their birth. These literary detectives not only represent that class but also secure and safeguard it with the high-power lenses through which they observe the world and convert it into images subject to their expert surveillance. Repeatedly, the technology they embody is focused upon the body of a woman, the representation and possession of which either enables the maintenance or threatens the subversion of established categories of class and gender.

Throughout these narratives of detection and enforcement, then, the photograph figures as a contested site of power and representational authority, just as it increasingly did in actual police practice in the nineteenth century. Assertions like Poe's about photography's scientific character and its power to capture rather than simply represent the real prefigured these eventual applications of photography to criminal identification, prisoner documentation, and courtroom evidence. As the texts examined here demonstrate, however, in addition to popularizing this notion of photography as evidence and authentication, detective fiction also made clear that the photograph could be a weapon for control and coercion.[31] Indeed, police work was one of the first public uses to which the new technology of photography was put when the portraitist Mathew Brady was commissioned in 1846 to photograph criminals for a British textbook on criminology.[32] Later in the century, police departments in Europe and America alike adopted Alphonse Bertillon's archival system for organizing criminal information, a system based on the portrait parlé, or "talking picture," a card consisting of a photograph of the criminal accompanied by a set of vital statistics by which he could be identified with certainty (Fig. 54). Whatever the suspect might claim

about himself, the assumption was, his photograph could "talk" too, and would invariably tell the real truth about him.

The links between the methods of Bertillon and those of Holmes are clear enough to be registered explicitly in the Holmes stories themselves. When in "The Adventure of the Naval Treaty" Holmes speaks with Watson about Bertillon, he expresses his "enthusiastic admiration of the French savant."[33] Later, in "The Hound of the Baskervilles" (a tale in which identifying a family portrait plays a central role), Holmes's client refers to Bertillon and Holmes as the two "highest experts in Europe" in criminal investigation, citing Bertillon as "the man of precisely scientific mind" and Holmes as the "practical man of affairs."[34] Indeed, their careers were almost exactly contemporary since Bertillon was just rising to prominence in the Paris Prefect of Police office when Holmes was introduced to the public in the pages of the Strand . Holmes, the practitioner of Bertillon's theory, was also the popularizer of his method, which included the application of photography to police work. As is demonstrated by the widespread deployment of the portrait parlé (or mug shot) and the rogues' gallery as forms of criminal identification, photography was appropriated in the nineteenth century by police and detective forces alike as an instrument of dependable intelligence and as a basis for conclusive proof, effectively transferring the suspect's right to tell his own story to an official agent of the government.

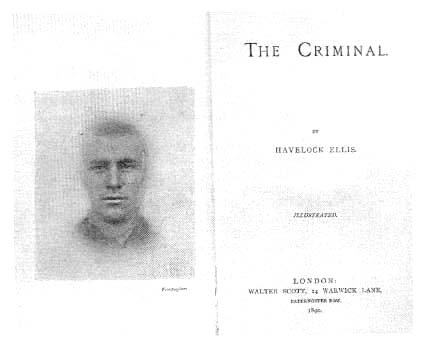

If Bertillon's use of photography to distinguish one individual from another depends upon and reinforces the authenticating virtues of photography, however, Sir Francis Galton's somewhat earlier introduction of composite photography to render the portrait of a "criminal type" emphasizes photography's disciplinary and controlling powers. One of the more imaginative and revealing deployments of photography in the emerging science of criminology, Galton's composite photography sought to visualize and "bring into evidence" all the traits of the typical criminal, much as criminologists like Lombroso or Havelock Ellis did in identifying the "stigmata" that mark the "born criminal." When Ellis uses one of Galton's composites as the frontispiece to the first edition of The Criminal, the pioneering book on criminal anthropology in England, he makes the relation between the two fields of inquiry explicit (Fig. 55).[35] The observing machine Galton invented, like those of Dickens or Doyle, disciplined the observer's eye, making certain invisible features visible and making certain visible features disappear. Galton's account of the technique's capabilities seems to invoke Dickens's and Doyle's descriptions of their visually gifted detectives: "A composite portrait represents the picture that would rise before the mind's eye of

a man who had the gift of pictorial imagination in an exalted degree."[36] Galton first described the procedure for making these photographs in 1878, in a paper tracing the idea to a stereoscopic technique in which cartes de visite from two different people were used to create the illusion of a single face with the attributes of both persons. He gradually refined the procedure to superimpose many portraits of criminals on a single negative to produce pictures of what he called a criminal type. The images so produced "represent not the criminal," he cautions, "but the man who is liable to fall into crime" (224). "These ideal faces have a surprising air of reality," Galton would nevertheless maintain. "Nobody who glanced at one of them for the first time would doubt its being the likeness of a living person, yet, as I have said, it is no such thing; it is the portrait of a type and not of an individual" (222).

The machine Galton devised to achieve this visualizing power was based on a principle of redundancy. When he photographed the carefully registered portraits of various criminals in succession on a single plate, he reasoned that whatever traits were common to all the criminal faces would reinforce one another and appear with more definition on the final print, while the eccentric features of a single individual would appear only once and therefore would effectively disappear in a blur on the final print: "The effect of composite portraiture is to bring into evidence all the traits in which there is agreement, and to leave but a ghost of a trace of individual peculiarities" (7). "I have made numerous composites of various groups of convicts, which are interesting negatively rather than positively," he continues. "They produce faces of a mean description, with no villainy written on them. The individual faces are villainous enough, but they are villainous in different ways, and when they are combined, the individual peculiarities disappear, and the common humanity of a low type is all that is left" (11). In Galton's reasoning, as in his photographs, the individual becomes ontologically secondary to the primary reality of the type of which he or she is an example, even though the type is itself constructed from the assembled individuals.

For Galron this "type" is not a fiction even if it is a construction. Indeed, the composite photograph his camera produces appears real to many people because, Galton argues, in a sense it is. The composite photograph reveals some essential truth, it "brings into evidence," as he puts it, truths otherwise invisible to the eye. Galton uses the rhetoric of the "type," the "ideal," and the "generic" to suggest the higher reality of an abstract yet authentic human norm, compared to which individuals are reduced to ghostly traces, existing literally as mere shadows of the more substantial type. Instead of the photograph's "perfect identity"

with the subject it represents that Poe proclaimed, Galton's composite photograph achieves greater reality and truth than its individual subjects ever could. For Galton, the photograph of the type is the real thing, and whatever constitutes the individual is reduced to an insignificant blur:

Composite pictures, are, however, much more than averages; they are rather the equivalents of those large statistical tables whose totals, divided by the number of cases, and entered in the bottom line, are the averages. They are real generalisations, because they include the whole of the material under consideration. The blur of their outlines, which is never great in truly generic composites, except in unimportant details, measures the tendency of individuals to deviate from the central type. (233)

In Galton's hands, the camera is wielded like a weapon to enforce and defend a particular conception of the criminal type and of reality as well. His images not only make the deviant equivalent to the criminal, they train every individual to be subject to the tyranny of types (normal and criminal) and to view every other individual with the eyes of a suspicious detective. By taking persons out of their concrete historical circumstances and locating them in some timeless zone of photographic reality, Galton is able to investigate the mind as well as the body of the criminal and to expose us to the process at the same time. "My argument is," he asserts,

that the generic images that arise before the mind's eye, and the general impressions which are faint and faulty editions of them, are the analogues of these composite pictures which we have the advantage of examining at leisure, and whose peculiarities and character we can investigate, and from which we may draw conclusions that shall throw much light on the nature of certain mental processes which are too mobile and evanescent to be directly dealt with. (232)

It is easy to see how a technique that so seamlessly elides the barrier between imagination and fact and ignores any fundamental distinction between individual identity and collective "character" could be put to use in Galton's argument for a policy of eugenics to improve the race and to fortify the nation. Indeed, the book in which Galton first used the term "eugenics" and elaborated its principles begins with a chapter describing the technique of composite photography and its importance in demonstrating how "the innate moral and intellectual faculties" are "closely hound up with the physical ones" (Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, 1883). It is also easy to see how the authenticating and disciplinary function of photography suggested by the perfect observing machines Mr. Bucket and Sherlock Holmes (who merely moni-

tored gender and class difference) could develop into a nightmare of policing and control aimed at purifying a race and typing individuals. Like their literary counterparts, Victorian scientists made use of Victorian cameras to teach the world to see in new ways, to observe laws of vision that often obscured as much as they illuminated. The photograph and the literary detective, like the fingerprint and the entire discipline of criminology, may be thought of as allied forms of cultural defense in which the bodies of persons were systematically rendered into legible texts and then controlled by the experts, who alone knew how to read them. When we look at those nineteenth-century photographs, and at the machines that took them, we must remember that these images were generated to make us notice certain things about history by making us blind to other things.

Fig. 48.

Engraving by R. T. Sperry from Helen Campbell, Darkness and Daylight; or,

Lights and Shadows of New York Life (Hartford, Connecticut: A. D. Worthington,

1892), introducing the chapter by Thomas Byrnes from the "Famous Detective's Thirty

Years Experiences and Observations." The engravings for the book were made

"from photographs taken from life expressly for this work, mostly by flash-light."

Recalling the scenes of Inspector Bucket in Bleak House, the flash of the detective's

bull's-eye here resembles the flash by which the original photograph would have been taken.

Fig. 49.

George Cruikshank, wood engraving of Richard Beard's public photographic

portrait studio in London, 1842, the first such studio in Europe. Beard franchised the

business throughout London and the provinces between 1841 and 1850, by which time

the considerable fortune he had accumulated was exhausted by protracted lawsuits

against infringers of his copyright. Photograph courtesy of the Gernsheim Collection,

Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Fig. 50.

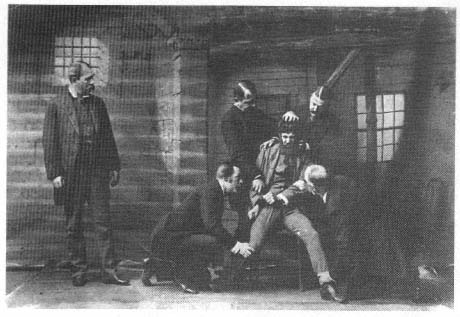

Jacob A. Riis, "Photographing a Rogue: Inspector Byrnes Looking On." Byrnes's

use of the portrait for his famous rogues' gallery anticipated the widespread use of the

portrait parlé of Bertillon in police departments and the files of mug shots that would

form the basis of criminal records in Europe and America. Photograph: The

Jacob A. Riis Collection, Museum of the City of New York; used with permission.

Fig. 51.

Drawing by R. T. Sperry, "An Unwilling Subject—Photographing a Prisoner for the

Rogue's Gallery at Police Headquarters" (1892). This engraved version of Figure 50

(demonstrating Byrnes's technique of coerced and resisted portraiture) replaces the

detective at the left in the photograph with the photographer and his camera, suggesting

their interchangeability. Like Figure 48, this engraving illustrates the

chapter of Byrnes's recollections in Darkness and Light .

Fig. 52.

Honoré Daumier, "Nadar Raising Photography to the Height of Art,"

lithograph, 1862. Nadar is credited with taking the first aerial photograph (in 1850) and

was as one of the first to use arc light for flash photography in the early 1860s. As the

Strand Magazine article attests, the aerial photograph would, in 1890s England, become

a form of national surveillance and defense as well as an elevated art. Photograph courtesy

of the Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center,

The University of Texas at Austin.

Fig. 53.

D. H. Friston's frontispiece for the first edition A Study in Scarlet is the first

depiction of Sherlock Holmes. It pictures him with the high-powered lens with which he

would always be identified.

Fig. 54.

In this illustration from Anthropologie Métrique, the book Alphonse Bertillon

co-authored with A. Chervin (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1909), the camera resembles

a machine of execution or interrogation as much as a form of representation. Bertillon's

system was deployed by law-enforcement agencies, anthropologists, and even

missionaries to monitor, scrutinize, and control the criminal (or foreigner).

Fig. 55.

The frontispiece for the first edition of Havelock Ellis, The Criminal (1890),

employs one of Sir Francis Galton's composite photographs to represent "the criminal type."