Santa Cruz:

Santa Cruz

1695–1706; 1748; 1870s; 1974

Given the vast amount of land in New Mexico that is untenanted even today, it seems strange that there has been concern with overpopulation as far back as the colonial period. In actuality, the problem was not high population but a lack of water and arable ground. When Santa Fe was resettled after the successful return of the Spanish under the leadership of Diego de Vargas in 1693, the town could support only a limited number of people. Also in question were the yield and distribution of the surrounding lands. The founding of Santa Cruz was intended to alleviate the problem, at least for a specific group of settlers.

Santa Cruz occupies the north side of a fertile valley watered by the Santa Cruz River about twenty miles north of Santa Fe. Prior to the Pueblo Revolt there were some scattered ranchos and haciendas on the gentle slopes loosely confederated as La Cañada. On August 11, 1680, they attempted in vain to fortify themselves at Santa Cruz; but their efforts were unsuccessful, and they were forced to flee. During the twelve-year Spanish absence, a mixture of Tano Indians from Galisteo, San Cristobal, and San Lazaro, experiencing difficulties once again with their traditional rivals, the Pecos Indians, moved into the valley, in time forming what Prince termed "quite a large community."[1]

When Vargas retook Santa Fe and set up domestic and political housekeeping, he was faced with a land shortage. The problem was further escalated when a group of colonists from Zacatecas, Mexico, arrived in 1694 and requested land on which to establish homesteads. The governor looked north and decided on the valley of La Cañada, basing his claims to the land on settlement by the Spanish prior to the revolt. Vargas urged the Indians to move farther up the valley and in a gesture of good faith postponed the actual date of removal until the following year. When his order was not heeded, the Indians were forcibly removed. The new colony was to be called "La Villa Nueva de Santa Cruz de Los Españoles Mejicanos del Rey Nuestro Señor Carlos Segundo" (The New Town of Holy Cross of the Spanish Mexicans of the King Our Master Carlos II), a cumbersome name in either language for such a small town. Records usually refer to it more simply as La Villa Nueva de Santa Cruz de la Cañada (The New Town of Holy Cross of the Gentle Valley).[2] The "new" in the title refers to a small community existing before the floundering in 1680 and the subsequent establishment of the new one. Today it is simply Santa Cruz.

The town began by proclamation. On April 19, 1695, Vargas informed the settlers that they were to

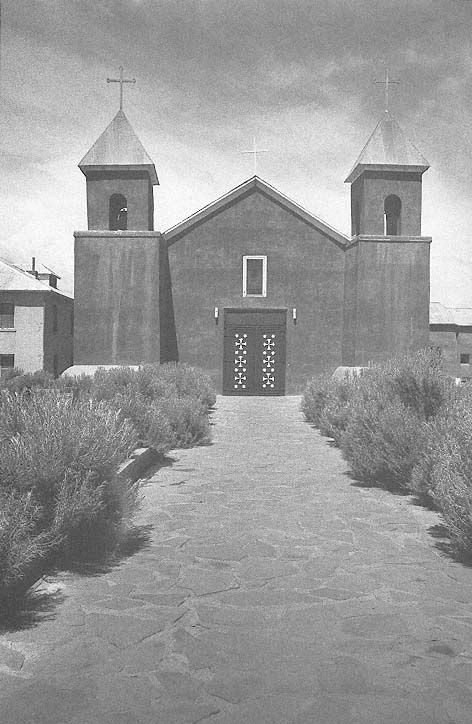

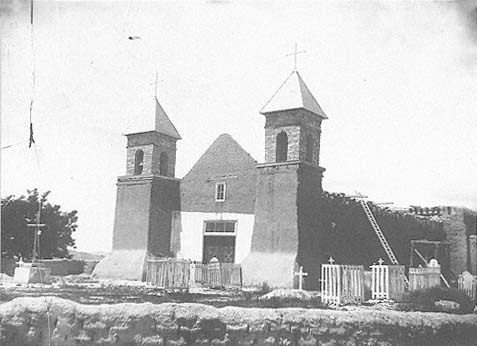

11–1

Santa Cruz

The church after its most recent restoration.

[1981]

11–2

Santa Cruz

The church and the town plaza. The assemblage of roofs covering the

nave and transepts illustrates the changes brought with the late-

nineteenth-century renovations

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

leave Santa Fe on the following Thursday at ten in the morning. "And I will then have in the plaza of the city the pack-mules I now have and will furnish some horses to mount in part those who may need them, and I will aid them in all things, assuring them a ration of beef and corn shall not be wanting as well as half a fanega of corn to each family for planting."[3] Fray Antonio Moreno was to accompany the settlers to comfort them in this trouble-some time, minister to their spiritual needs, and help them build a church.

The Spanish first settled on the south bank of the river, probably occupying to some degree the structures vacated by the Indians. The Spanish might even have built a small chapel. By 1707 they had begun to erect a church. Before construction began, however, the entire town was reestablished on higher ground removed from the threat of the floods that had been bothersome in the past. A widow, one Antonia Serna, donated "the necessary land for the church which had already been started, since it was for the religious, and that for their protection and that of the church, she was giving sufficient land in order that in all four directions the citizens might build the houses they liked in the form of streets, with the church in the middle."[4]

The size of the structure was probably meager, and it was noticeably lacking in either construction expertise or maintenance. If "by 1706 they had a small church and a bell," the building had declined in aspect to a rather dilapidated condition by 1732.[5] After a careful examination Governor Servasio Cruzat y Góngora declared the building to be "beyond repair and in danger of collapsing."[6] In response to a petition from the parish for a new structure, the governor then granted the parishioners the right to rebuild the church "at their own cost, the present one being in ruins."[7] About a week later, on June 21, 1733, the news was proclaimed in the plaza at Santa Cruz.

The widow Serna's intentions would take some time to reach fruition, however. Bishop Tamarón visited La Cañada in 1760. Although more concerned with the manner of confession than the state of the books, he noted that "the church is rather large but has little adornment." The Nueva Villa impressed him even less: "There is no semblance of a town."[8]

Although the exact population at the time is not known, the church project was certainly ambitious, and even today Santa Cruz is the largest colonial period church in the state. The 1750 census listed 197 families with 1,303 persons, already twice the size of most contemporary pueblos.[9] Santa Fe, with

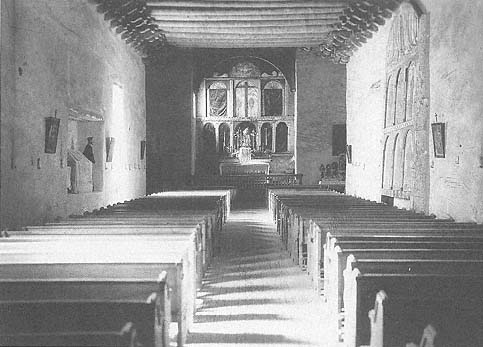

11–3

Santa Cruz

circa 1935

The interior of the church more than fifty years ago looks very much as it does today. Note

the Santo Entierro in the niche on the left.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

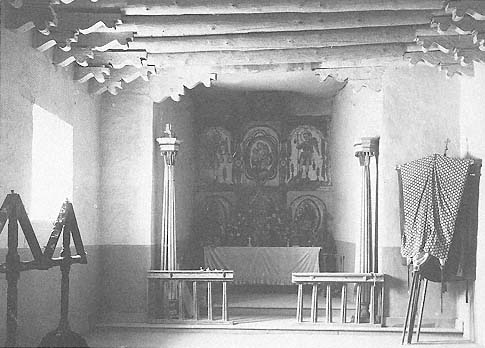

11–4

Santa Cruz, The South Altar

[Jesse L. Nusbaum, Museum of New Mexico, 1911]

an additional eighty-five years of on-and-off heritage, contained between fifteen hundred and seventeen hundred total souls, including some natives and persons of mixed blood. Albuquerque, the youngest of the three new villas, however, equaled Santa Cruz in population, although it was ten years or so younger in age.

"As late as 1744," Kessell noted, "a Franciscan superior declared that the resident minister at Santa Cruz, probably Fray Antonio Gabaldón, 'is now building a sumptuous church by order of my prelates, without its costing his Majesty half a real for its materials or building.'"[10] Kubler added that J. A. Villaseñor y Sánchez recorded the construction as finished in 1748, the date now ascribed to the church's completion.[11]

At least a partial remedy to the lack of adornment was the arrival of Fray Andrés José García de la Concepción, who seems to have possessed an equal love for compulsive labor and wood carving as well as a tremendous zeal for improving the church interior. During his three or so years at Santa Cruz, he completed an altar rail and an altar screen and carved santos of various sorts. His strongly emotional and evocative image of the dead Christ, the Santo Entierro, still occupies a niche in the south wall and records the efforts of one of New Mexico's first santeros.

Enter Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez on his tour of the missions in 1776. In his fastidious fashion Domínguez recorded that the church was built of adobe, faced east to its plaza, contained a clerestory, and had the typical steps up to the sanctuary. But alas the choir could not sing in its usual place, he noted, because there was no choir loft. There were four windows with wooden gratings, one in each wall of the transept on the Gospel (south) side, two in the nave on the south wall, and another over the main door. The roof construction, however, was unusual: "The roof of this church is arranged differently from the usual, for there are five cross timbers consisting of three strong beams at regular intervals as far as the mouth of the transept. They are wrought and have multiple corbels. In each of the five spaces between these cross timbers there are twelve wrought beams running lengthwise of the church." The sanctuary also contained "a vaulted arch made of boards."[12] Domínguez then credited Captain Juan Esteban García as the builder of the ceilings and Fray Andrés José García with the remainder of its construction. There was but one tower at the time.

Domínguez, usually critical of New Mexican church ornaments, had mild praise for the García altar screen: "The altar screen is of the kind of wood common in the kingdom, and it is exquisitely made, for it is painted with white earth and consists of two sections that look like the boxes of a bull ring, for the niches are squared and, except for the chief one, all have little balustrades below as is customary in the aforesaid boxes."[13] Less appealing to the friar's Mexican taste was the pulpit: "The pulpit is in the usual position and is a horror."[14] Period. The altar for the Third Order occupied the Gospel side of the chancel, although the Carmel chapel extended to the north. The latter was blessed with a choir loft, however, as the nave was not. At the head of the transept was a sacristy. The convento, built mostly by Gabaldón, abutted the church to the south. Its furnishings were scant.

Like Tamarón, Domínguez was not impressed with the disposition of the town. "In view of the fact that the Villa of Santa Fe," Domínguez noted wryly,

is not as golden as the glitter of its name, in spite of the circumstances mentioned that it is the capital, etc., it will be apparent that this Villa of La Cañada, which does not have such an ostentatious aspect, is probably tinsel. . . . The church, then, is in the place I described with eight small houses like ranchos to keep it company. The rest of the villa is nothing more than ranchos located at a distance.[15]

The church had ministration of Chimayo, Quemado, and Truchas further up the valley. The population comprised 125 families with 1,389 persons, suggesting that the land supported just about as many colonists as it could.[16]

Just seven years after Domínguez's visit, Fray Sebastián Fernández had to replace some of the roof beams that had rotted. To balance the chapel of Our Lady of Carmel to the north, the south transept was rebuilt as the Third Order chapel some time between 1784 and 1789, underwritten by the financial resources of Fray José Carral.[17]

Change, whether constructive or destructive, was chronic in the lives of New Mexican churches. By 1796 considerable work had been expended on the body of Santa Cruz. The church "is very spacious," wrote Fray José Mariano Rosete, "of good adobe construction, with new roof having large pine vigas and lumber of the same. . . . The Church and Chapels contain their new pulpits; throughout there are four excellent confessionals." The single tower remained, but "there is a choir loft with its railings and its ladder, all new."[18]

Santa Cruz church, a massive structure dwarfing the few residential structures that might have surrounded it, must have appeared extremely im-

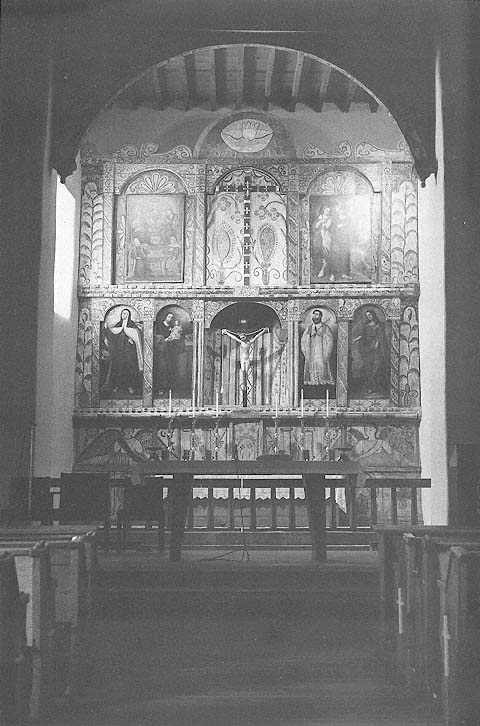

11–5

Santa Cruz

Although the clerestory is blocked by the metal roof, a south-facing window approximates

the light quality of a clerestory on the altarpiece.

[1981]

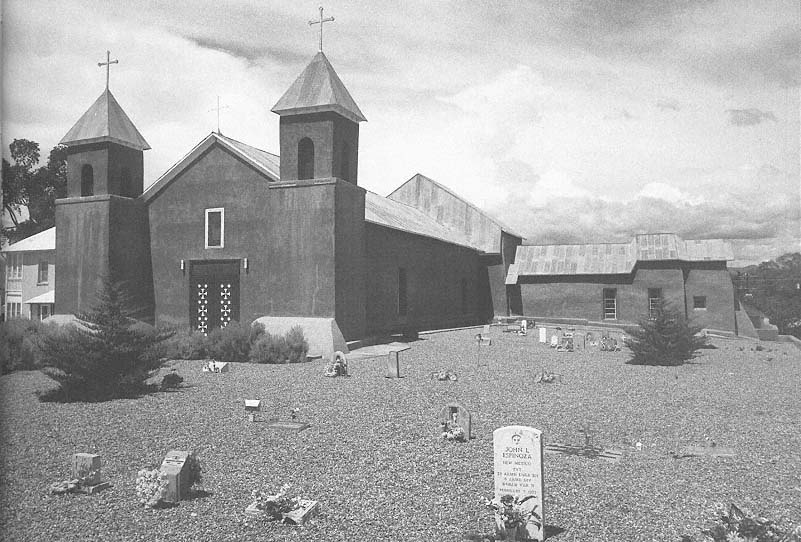

11–6

Santa Cruz

circa 1883

Late in the nineteenth century the church was ornamented with elaborately decorated

parapets.

[W. H. Jackson, Museum of New Mexico]

11–7

Santa Cruz

June 1897

By the end of the last century attempts to decorate the mud church had dissolved in the

rain and wind. The painted lower part of the facade concentrates attention on the entry.

[Philip E. Harroun, Museum of New Mexico]

pressive for its day; perhaps more as the image of a fortress of God than as a welcoming shelter. The elements of God and nature, however, in conjunction with the passage of time never ceased their effect on adobe construction.

Visitors to Santa Cruz were continually impressed by the size of the church, but never by its quality of finish. Fray José Benito Pereyro's 1808 report found the church "[is] materially reasonable and has, although very old but serviceable, the necessary ornaments." The convento, however, "is almost totally unserviceable, and was built at the expense of Fray Ramón Antonio Gonzáles, consisting of seven rooms, upper and lower levels."[19] Don Juan Bautista de Guevara, paying the villa a visit in 1818, had little except critical comments for the expressive imagery used on the hide paintings that decorated the church, although he noted that the chapel of Our Lady of Carmel had a wooden floor. Tamarón condemned its bareness; Domínguez and Guevara cared little for the aesthetics of its painting, with the exception of the altar screen. "The cemetery is thirty-one varas square, with its entrance, which is without the wooden door because it is broken. . . . In each corner is a little chapel (ermita ). One of them has fallen but the wood to rebuild it is at hand. . . . In each of said chapels there is a platform-like table, and these serve as stations during the procession on the day of Corpus Christi."[20]

With 1826 came the visit of Don Agustín Fernández San Vicente, who also described Santa Cruz: "The door of the church looks to the east and is of two leaves. . . . Above there is an adobe tower with two small stories and its spire (capitel ) and a cross of wood. . . . The church yard or cemetery is thirty varas square with a gallery all around having wooden pillars and a good roof but without drain spouts, and with its main gate. In the center is a wooden cross on a flat-topped pedestal."[21]

Santa Cruz remained a sleepy town during the first half of the nineteenth century, although it was a battle site in the revolution of 1837. During the insurrection of 1847 the villa witnessed another key shootout, which ultimately led to the destruction, by cannon and fire, of the Taos pueblo church of San Jerónimo. Father Juan de Jesús Trujillo left a report in 1867 that credited his own efforts for changes and repairs to the church. "[Of] two towers of earth and rock, the one on the south [was] constructed during my time. . . . There is a choir loft, a glass window with its screen. The choir loft and window screen were installed during my tenure. There is another choir loft at the door of the church held by supports added during my tenure."[22]

French taste arrived with Archbishop Lamy in the 1860s and reached Santa Cruz shortly thereafter. Kessell credited either Reverend Jean Baptiste Courbon, who lived at Santa Cruz from 1869 to 1874, or Reverend Lucien Remuzon, in residence from 1875 to 1880, with the incredible transformation of the exterior of the church at that time.[23] The bulk of adobe bricks piled one on the other in walls five feet thick remained in evidence, but its mass was disguised beneath an ornamental treatment that could have rivaled pastry decoration. The walls were left unplastered, or at least the brick units were exposed, and each wall was capped with decorative spun finials. Little arches running along the length of each of the chapels graced the parapets. The towers now supported chapeaux of wood; and each of them—and the pediment—was crowned by a decorative, florid iron cross.

Most prominent in the early photographs from the 1870s is the high (twelve- to fourteen-foot) wall that surrounded the entrance court and that was pierced by a gate on axis with the main doors of the church. Two tiny arches capped the pediment, forming a transition between the towers and the slope of the pediment. The entirety was aesthetically provocative—some evocative conjuring of an exotic conglomerate style that seems to rate the name of Primitive-Moorish-African-French or any combination of these in any order. It could not last. Decorations of that sort exposed to natural forces too much surface area for their mass, a property that hastened the disintegration of unfired earthen material. No doubt, the lovely and charming French efforts began to melt almost as soon as they were completed, if not before.

At this time, however, additional windows had been added to the church, the sole source of lighting having been the clerestory and the window that illuminated the choir. In a William Henry Jackson interior photo of 1881 the handsomely proportioned interior, with its rough whitened walls, heavy vigas and corbels, and gently rising packed earth floor, appears sparse, yet focused. The Santo Entierro still occupies its niche in the south wall, and the old altarpiece is now mounted on the north wall of the nave. A baldachin covers the altar extending into the nave, and the pulpit to which Domínguez so strongly objected is not to be seen. The walls around the entrance court, however, have not fared so well. Another of Jackson's photos, this one an exterior, shows the walls melted down to three feet, fragments of the parapet decoration of the north chapel still remaining and one iron cross on the north tower sadly askew. As a positive gesture the area immedi-

ately around the main door has been whitewashed: the efforts toward maintenance are still present but are limited.

About this time Lieutenant John Bourke passed through Santa Cruz and waxed sufficiently romantic to use the sublime aspects of the church as a counterpoint for the "horrors" of its iconography:

Within there is a choir in a very rickety condition, and a long narrow nave with a flat roof of peeled pine "vigas" covered with riven planks and dirt; on one side, there is a niche containing life-size statues of our Savior, Blessed Virgin, and one or two Saints; all of them, as might be expected, barbarous in execution. Facing this niche is a large wall painting, divided into panels, each devoted to some conventional Roman Catholic picture, which in spite of the ignorance of the artist could be recognized.[24]

Although Bourke took issue with the aesthetics of the images, he seemed at least somewhat touched by the quality of the church as a religious setting:

Tallow candles in tin sconces, affixed to the whitewashed walls, lit up the nave and transept with a flicker that in the language of piety might be styled a "dim religious light," but in the plain, matter-of-fact language of every day life would be called dim only. Full atonement for the comparative obscurity of the parts of the sacred edifice occupied by the Congregation was made in the illumination of the chancel which blazed in the golden glory of a hundred tallow candles. A dozen or more cedar branches, souvenirs of last Christmas, held to their positions of prominence with a sere [sic ] and yellow persistence much like that of maidenly wall-flowers in their tenth season.

Upon the floor of flagging and bare earth, a small congregation was devoutly kneeling . . . without a seat or bench upon to rest at any moment during the long service.

Ridiculous as some of these proceedings were, it was impossible not to be deeply impressed by the fervent and unaffected piety of all the congregation.[25]

By the turn of the century the church had been protected by a wooden pitched roof, shortly thereafter superseded by one of metal. The sloped caps on the towers were probably contemporary. Four windows in the nave, two on the north wall, two on the south wall, were cut in 1918 by Anastacio Luján, who is also credited with plastering the exterior.[26] The wall around the campo santo eroded further and in time was reduced to a wire and pole fence. A transom was installed over the main entrance, and the earthen floor was replaced by a level wooden floor set on sleepers. The enlarged windows were to some degree a necessity because the clerestory had been lost when the pitched roof was added. One window, however, high on the south wall in the sanctuary, effectively replaced the directional clerestory light that had fallen on the altarpiece.

In 1974 the Santa Cruz church was designated a National Historic Site. Shortly thereafter the church council requested architect Nathaniel Owings to prepare a master plan for the church's restoration, which was undertaken in association with Johnson-Nestor, Architects, of Santa Fe. Its report reviewed the history of the church as well as its current context and condition. The findings recommended that the transom over the door be removed to improve the scale of the building and that a high wall be reinstated around the campo santo to create a more significant transition to the plaza, which had been reduced over time to a traffic crossroads. The plaster on the towers should be removed to expose the stone construction; in fact, all cement plaster should be replaced by mud plaster, the report stated. Repairs should be made to the wooden floor where necessary, and in the transepts and in other areas of low use, earthen floors should replace the concrete, tying the church back into its past. The report also recommended the reinstallation of the baldachin, the pulpit (Pace Domínguez!), and the choir loft in the north chapel.

More radically, the architects suggested that the north windows be sealed and that the size of the south windows be reduced to recreate more of the feeling of the original illumination in the nave. The metal roof should remain, the recommendation said, meaning that the clerestory itself could not be freed; the reasoning here suggested that the high metal roof was now common in the architectural vernacular of the New Mexican mountains and that with it the church had acquired a certain familiarity. Certainly the hulking roof had become almost as much the image of the church as the adobe beneath it. It was a curious and unique form, derived from its leaping over the clerestories in each of the transepts.

Not all the work was carried out. In the late 1970s priority was given to the restoration of the artworks, some of which were in a precarious state of preservation. The cement plaster in the interior was stripped and replaced with mud plaster covered with tierra blanca. Certain portions of the exterior walls were stabilized, and some attempts at land-scaping the campo santo were undertaken. Much remains to be done.

Santa Cruz is still a large church for New Mexico, and the visitor coming upon it on the High Road to Taos is always surprised; the church's bulk is so much greater than any structure in the immediate

11–8

Santa Cruz

The pitched roof covers the irregular profile of the adobe forms like a metal carpet.

[1986]

11–9

Santa Cruz, Plan

[Sources: Kubler, The Religious Architecture , 1940, based on HABS; and plan by Johnson-Nestor,

Architects, 1978]

vicinity. The grounds of the church and the plaza it fronts are almost always dusty, which can either be annoying or atmospheric, depending on the visitor's mood. The two-leaved doors, although eroded by exposure to the elements, are still beautiful, with graceful, yet simple carvings applied to the panels. In 1981 the transom above the door was blocked: not in adobe as prescribed by the restoration report but with a piece of plywood covering the broken glass. Inside, the newly restored altar screen glows yellow with the brilliant light from the south sanctuary window. The art in the church is splendid and includes several works by Rafael Aragón, a noted mid-nineteenth-century santero who is buried in the church. The parish seems to thrive, with 1,400 families registered, according to a 1980 article, and is committed to restoring and maintaining the structure and its art.[27]

In 1920 the administration of the church was turned over to the Congregation of the Sons of the Holy Family from Barcelona, Spain, in whose care it remains today. There is a solidity to the church anchored to the earth by its eastern facade: the two squat towers sitting on their portly bases. From a distance the structure appears almost toylike; from closer the toy is transformed into powerful bulk. Notwithstanding his dislike of the more gory aspects of Hispanic colonial art, Bourke could still wax poetic about Santa Cruz. Sleeping out in the plaza in 1881, he awoke: "The rising sun threw against the sapphire sky the angles and the outline of the old church, bringing out with fine effect its quaint construction and excellent proportions. The waning moon in mid-sky shed a pale, wan light that grew fainter and fainter as the orb of day climbed above the horizon;—back of all rose the massive, deep-blue spurs of the Sierra de Chama."[28] Today, at sunset as well as sunrise, the effect remains poetic.

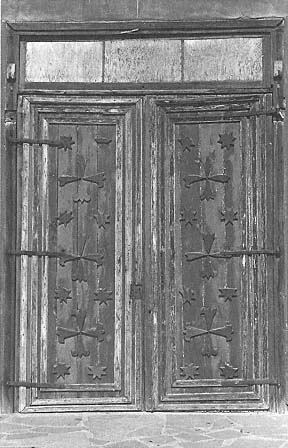

11–10

Santa Cruz

The wood appliqué entrance doors to the nave.

[1981]