Motion Picture Patents Company Agreements

The Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPCo) was owned equally by the Edison and Biograph companies, with a few shares going to the directors as required by law.[23] Dyer, vice-president of the Edison Manufacturing Company, was elected president and George F. Scull, another Edison lawyer, was elected secretary. Harry Marvin and Jeremiah Kennedy were elected vice-president and treasurer respectively. The MPPCo was formed with the recognition that the patents controlled by Biograph and those controlled by Edison were of equal importance in the eyes of the courts. Each company agreed to deposit its shares of stock with the Empire Trust Company, which acted as trustee, and instructed it "not to release, transfer or return the said certificates so deposited without the consent of" both parties and Thomas Armat.[24]

The Edison Manufacturing Company, the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company, the Armat Motion Picture Company, and Vitagraph Company of America assigned their patents to the MPPCo in return for certain guarantees on the morning of December 18, 1908. That afternoon the MPPCo signed agreements with nine producers and importers: the Kleine Optical Company, Biograph, the Edison Company, and the original Edison licensees, excepting the Méliès company. The Méliès concern was denied a license because it had come under the control of Max Lewis, a Chicago renter, in violation of earlier Edison licensing agreements.[25] Over his objections, Kleine was only allowed to import three reels of film per week, two to be supplied by Gaumont and one by Urban-Eclipse. Gaumont was selected because it owned the patents to the Demeny camera and might have provided independents with a non-infringing apparatus if left outside the trust (the status of the Demeny camera had yet to be tested in

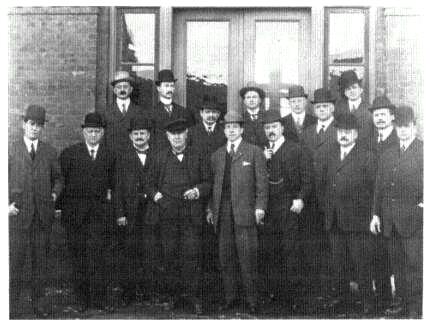

Executives of film companies newly licensed by the Motion Picture Patents Company

gather at the Edison Laboratory on December 18, 1908. First row (left to right): Frank L.

Dyer, Sigmund Lubin, William T. Rock, Thomas A. Edison, J. Stuart Blackton, Jeremiah

J. Kennedy, George Kleine, and George K. Spoor. Second row: Frank J. Marion, Samuel

Long, William N. Selig, Albert E. Smith, Jacques A. Berst, Harry N. Marvin, Thomas Armat(?),

and George Scull(?).

the courts).[26] Urban-Eclipse was probably included because Charles Urban controlled G. Albert Smith's kinemacolor process. Other European firms were considered too weak to effectively confront the power of the MPPCo and were entirely excluded.

Based on the MPPCo's control of essential patents, interlocking agreements were made with the moving picture manufacturers and importers, film exchanges, exhibitors, Eastman Kodak, and various projector manufacturers.[27] These not only assured the collection of royalties in different areas but further concentrated power in the hands of the film producers and importers who were the keystone of the contractual system. The nine companies could only lose their licenses if they acted in gross violation of the agreements and ignored specific warnings for a protracted period of time. Their right to a license was effectively assured. Moreover, additional licenses could only be granted with majority approval of the already licensed manufacturers. They still paid royalties to the licensor on raw stock, but the amount was lower than under the old agreement. Royalties remained 5 mills (½¢) per foot for firms buying less than 4,000,000

feet of raw stock each year, but were 4.5 mills per foot for manufacturers purchasing from 4,000,000 to 6,000,000 feet, 4 mills per foot if between 6,000,000 and 8,000,000 feet, 3.75 mills if orders totaled between 8,000,000 and 10,000,000 feet, and only 3.25 mills per foot if a company exceeded 10,000,000 feet per year. The Edison Manufacturing Company, however, did not pay a licensing fee on raw stock. A minimum pricing schedule for films leased to exchanges continued as before. List price was 13¢ per foot and standing orders were 11¢ per foot—figures that assured a healthy profit margin for most producers. The licensed manufacturers had no restrictions on the quantity of their releases. Only Kleine was limited to three reels of film per week.

The MPPCo signed an agreement with Eastman Kodak on January 1st, superseding the one previously in effect between the raw stock supplier and the Edison licensees. Under this reciprocal arrangement, licensed producers and importers would only purchase film from Eastman, and Eastman in return would only sell 35mm motion picture film to licensed manufacturers, excepting a small percentage of film set aside for experimental and educational purposes. As it had done for the previous six months, the Eastman Kodak Company collected MPPCo royalties on raw stock as it was purchased by the licensed manufacturers. This arrangement made it more difficult for independent moving picture producers to operate effectively and secured Eastman's position by turning major users into long-term customers. The company also agreed to supply raw stock for a maximum cost of 3¢ a foot for unperforated film and 3.25¢ for perforated. Such an arrangement reduced commercial uncertainty for both parties.

Film exchanges were given until January 20th to sign contracts with the MPPCo. These were to go into effect on February 1st. Almost all the renters from the Film Service Association and a few major "independent" exchanges were given the opportunity to become licensees. The Toledo Film Exchange was not offered a license because its checks had often bounced; the Chicago Film Exchange because of its attempt to acquire the Méliès license; Adam Kessel's Empire Film Company probably because it was bicycling prints; and Harstn & Company because its purchases were too small under the old system.[28] In the earlier agreements between the FSA and the Association of Edison Licensees, manufacturers and renters met, at least nominally, as equals. This was no longer the case. The MPPCo offered renters a license that could be unilaterally revoked with or without cause after fourteen days' notice. As one trade journal remarked: "The position of the renter. . . is not an enviable one. He might work up a large business, the tenure of which is determinable by a fortnight's notice at the discretion of a possibly irresponsible person. Thus, the sword is always suspended over the head of the renter. Not a reassuring state of affairs to an ordinary business man."[29] The MPPCo and the manufacturers, rather than the FSA, established rules and punished the violations of rental exchanges.

Many of the regulations established by the FSA were enforced with new rigor. Again licensed exchanges could only acquire films from licensed manufacturers, just as licensed manufacturers could only deal with licensed exchanges. Film was no longer sold outright but leased. A film or some substitute had to be returned to its original manufacturer seven months after it was acquired. Films could also be recalled by the manufacturer after an exchange violated the licensing agreement. Each branch owned by a renter was now treated as a separate exchange, while the minimum amount of film that an exchange had to purchase was increased to $2,500 per month, double the old figure. Nor could film be shuffled back and forth between exchanges run by the same owner. This eliminated a number of small exchanges and branches, but increased overall demand. It also encouraged a steady, year-round flow of films through the system. The release system was refined: a film could not be shipped from an exchange before 9 A.M. on its release day. A minimum rental schedule was again established, this time determined by the manufacturers. Moreover, a licensed exchange could only rent to a theater that was licensed by the MPPCo. Violations resulted in fines and eventual suspension. As a result, renters found their activities highly regulated and restricted.

Exhibitors were a new and important revenue-generating element in the MPPCo's agreements. The key patents for exhibition were controlled by Thomas Armat, whose attempts to license exhibitors in the 1890s and early 1900s had failed after receiving insufficient judicial support. The MPPCo now asserted that Armat's patents, in combination with others under its control, allowed it to license exhibitors for the use of its members' various inventions. Each exhibitor was required to pay the MPPCo $2 a week per theater, irrespective of its size or profitability. Compulsion was not so much legal as commercial. In practice, a license simply gave the exhibitor the right to use licensed films rented from licensed exchanges. Exhibitors who showed unlicensed films without paying the $2 were not challenged for patent infringement. An exhibitor could not, however, present licensed and unlicensed subjects at the same time. When this was attempted, the MPPCo instituted replevin suits and repossessed its films. The power of the MPPCo over the exhibitor was based on its control of product rather than on potential legal action for patent violation. Originally the exchanges were expected to collect the theaters' royalties for the MPPCo. When the renters protested, however, the MPPCo agreed to assume that role.[30] The problem of coordinating exhibitors and exchanges proved so awkward and unsatisfactory, however, that the original plan was reinstituted within a few months. While renters paid no direct royalties, like Eastman they were given the task of supervising another branch of the industry. Royalties from exhibitors alone were expected to total more than $500,000 a year during the first year of operations.[31]

Incidental to this series of interlocking agreements was the licensing of ten projector manufacturers, who were charged a royalty fee of $5 per machine.

Three of the licensees—Vitagraph, George Spoor & Company, and the Armat Motion Picture Company—were inactive. Several others were licensed film manufacturers, including the Selig Polyscope Company, the Lubin Manufacturing Company, the Edison Manufacturing Company, and Kleine's Edengraph Company (manufacturer of the Edengraph projector, which descended from the machine Porter had used and refined at the Eden Musee). Licensing arrangements excluded some small equipment manufacturers and raised barriers to entry into the field. The MPPCo forced the Viascope Company out of business by court action.[32] Licensed projectors were, in theory, only to be used with licensed films, but no mechanism was set up to assure that this would be the case. Perhaps more important, the manufacturers agreed to sell their machines for at least $150 each, assuring an adequate profit margin for everyone concerned. Since profits from projector sales represented a large portion of Edison motion picture profits, the financial value of this arrangement cannot be ignored.[33]

Royalties came from three different areas of the industry (exhibitors, film producers, and equipment manufacturers) and were divided in the following manner:

1. Net royalty figures to be derived by (a) subtracting Vitagraph royalties, $1 per projecting machine manufactured, from total machine royalties, (b) deducting 24 percent from gross exhibitor royalties for distribution to motion picture manufacturers and importers other than Biograph and Edison, and (c) deducting general litigation expenses from film and other royalties

2. Net royalties to be paid for distribution (a) to Edison in an amount equal to "net film royalties," and (b) to Biograph two-thirds and to Armat one-third of the remainder, up to an amount equal to "net film royalties"

3. Any balance after the division indicated above to be paid to Edison, Biograph, and Armat on a basis of one-half, one-third, and one-sixth respectively[34]

The Edison Company maintained its prominence in the new corporation, which its vice-president headed. Edison received the largest portion of the royalties, and the company's products were protected from price wars and other forms of competition it considered undesirable.