3—

One Hundred Minutes of Filmgoing

Bird Of Paradise ! Lush dreams of water and sun, Polynesian postcard colors, lagoon and waterfall frolics, heaven modulating into hell as blood spills down the waterfall and into the lagoon, advancing as implacably and as abstractly as the reds in Godard's La Chinoise ; torrents of orange and red volcanic lava supplanting the blues and greens of the idyllic island and its serene, mysterious tribe—

Bird of Paradise ! Scripted and directed by Delmer Daves and released in 1951, distant memory-stain of a fiery sacrifice in orgasmic Technicolor; Kalua (Debra Paget), daughter of the tribal chief, leaping into a volcano to appease an angry god in order to save her people, abandoning her beloved newlywed André (Louis Jourdan), college pal of her brother Tenga (Jeff Chandler), who has fallen in love with her, her tribe, and her island. Like a gush of boiling blood, a deadly synthesis of water and sun bleeding over all the greens and blues of my childhood Judaism, eventually yielding a dull brown that dried and crackled, before slowly flaking away—

Bird of Paradise ! Seen, appropriately, on two Sundays nearly twenty-seven years apart, both times in Florence—an area combining sun and water, green and blue and orange-red sunsets into its own dullish shades of fair and muddy, or flaky brown. On May 13, 1951, late afternoon at the Princess with my brother David, after trailers, newsreel, and Mighty Mouse cartoon; on March 12, 1978, 10:30 P.M. on Channel 6, WBRC-TV from Birmingham, in the former playroom I occupied with my brothers in 1951. With me the second time is my brother Alvin and my friend Ron Russell, a direct or indirect descendant of Jesse James whom I didn't get to know until the midsixties, but who saw the movie at the Princess during the same three-day run, probably on the same day. Neither of us has seen it since.

Bird of Paradise : At first we get only a black and white image of Twentieth Century-Fox's futurist insignia; then Ron takes over the tuning, and a rainbow of early fifties Fox Technicolor fills the screen. Ron remembers the movie better than I do, but both of us recall it as a heavy experience. Not quite traumatic, as Freaks at the Majestic was for me in 1950, or directly

Princess Theatre, Florence, Alabama, circa 1937

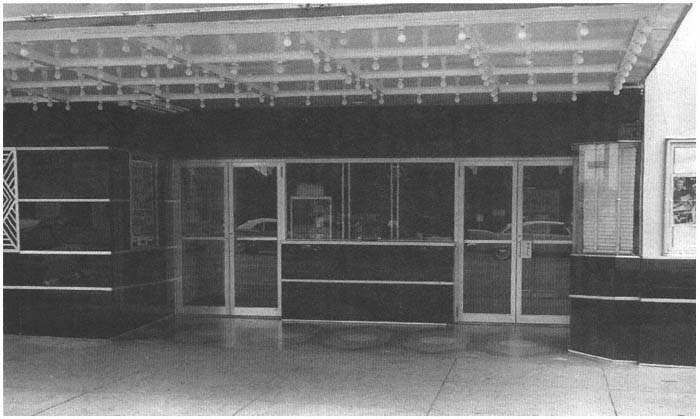

Closer view of remodeled Princess, 1950s

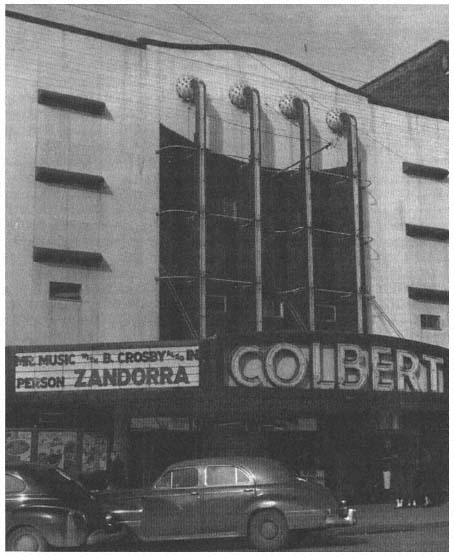

influential, as Athena at the Colbert was for Ron in 1955 when it launched his career in body building, but heavy nevertheless. Certainly not light or sweet like On Moonlight Bay , which we both saw five months later in 1951, but heavy with a sense of shock and outrage. What right had the tribe and its holy man, the Kahuna, to send beautiful Kalua into the volcano? And why did she obey them—particularly when, as Ron and I reasoned separately at the Princess, the volcano stopped erupting only a few seconds after she vanished?

Bird of Paradise ! Fire and outrage felt as one, a warm and persistent orange-red memory-stain, the title of the movie and most of the story forgotten for well over two decades, until I saw King Vidor's 1932 Bird Of Paradise at the Museum of Modern Art's Vidor retrospective in New York in 1972, recognized the plot, and intuited that I had already seen the 1951 remake. Outrage that persisted to feed another memory-stain, a nightmare dreamt three years later, when David was about to be bar mitzvahed, in which my family was sacrificing itself to Judaism by marching into a chilly lake to drown. "Why don't you come along?" insists my mother, while my father angrily tells me to stop being so selfish. Jealousy for the attention that David was getting, conjuring this up as another family ritual, the don't do it of 1951 becoming the I won't do it of the 1954 nightmare when, like Kalua, I find myself participating and complying nevertheless, against my will, my brain screaming all the while—leaving a burning memory-stain, a blasphemous afterblast that seared my faith.

Bird of Paradise ! Also being seen first-run in 1951 some 750 miles south, in Miami Beach, by ten-year-old Patricia Patterson, future painter, in a brand new deluxe theater containing a real waterfall in its lobby. All week long a skywriting plane has been advertising the opening of movie and theater alike over the blue-green ocean, a sign writ large in the firmament that has also been drawing special attention to Menasha Skulnik, the Yiddish actor who plays the Kahuna—Maurice Schultz in the credits, but Menasha to many of the Miami locals—and Patricia's been walking past the movie theaters, watching the skywriting, checking out the picture cards of Bird Of Paradise , little windows or View Master peeks into a kingdom even more magical than the theater presenting it. Seeing the movie afterwards, later in the week, is almost like reading a footnote. Memory-stains—the traces left that no amount of everyday brainwashing will clean away—are simple embarrassments that imagination, not memory, converts into complex comforts, the snug sort of pockets that we sometimes go to movies to find.

Bird of Paradise ! Collective images of the natives rushing into the emerald sea to greet Tenga and André's boat, diving back off in cascading ripples of pleasure, eating and dancing and sleeping and running together in a common pulse: all part of the movie's pagan delight, utopian giddiness, its gorgeous peyotelike pantheism which says that living is a form of being eternally grateful. But somewhere along the line the green lagoon becomes framed a lit-

tle differently, begins to look thick with bulrushes out of the story of Moses while the mountain becomes red-hot and threatening—like the Paramount insignia with a gaping wound, or Cecil B. De Mille on the verge of a temper tantrum—and the Old Testament ambience takes over, including a red sea of burning coals that Kalua has to cross over barefoot, to prove that her love for the outsider André is good and true. How could it be otherwise with a movie from a Judeo-Christian studio, watched by a snotty eight-year-old kid who was translating all this arcane pseudo-Polynesian ritual into Talmudic threats?

Bird of Paradise ! Ecstatic notions melted down from Flaherty's Moana and Murnau's Tabu , strained through the color schemes of Disney and De Mille, the epic nature worship of Leni Riefenstahl and Esther Williams, into the lyrical cranes and pans of Delmer Daves, delivered in a primal tongue that any kid could understand. If Ron and I hadn't been spending a large part of our days swimming, the dream visions might never have taken hold—of Elysian fields where the sun met the sea and the water was like laughter; of the formal rightness of this developing, modulating into the liquid fire of the volcano—even if our grasp of André and Kalua's love cried out against its unspeakable, unbearable orange-red demands. Kalua's love for André, their last meeting, when she tries to remove all his fear, speaking in riddles he can't understand: "To us, death is nothing. If we are blessed, we have found joy, as I have found it with you." Then leaving him behind in the empty village to rejoin her people, and leaving them as well, on the mountainside, to ascend the exploding inferno. A distant dark silhouette against the flames gazes back at the last moment, looking at André with absolute love across impossibly infinite spaces before dropping into oblivion.

Bird of Paradise ! Dirty old nostalgia, I wrote last summer: temporal homesickness lavished on objects both real and fancied rather than on people, places, and feelings, all of which seem to have shorter life expectancies. Nostalgia, the nest where racist ideologies and fascist storyboards are hatched and begin to chirp, like Disney ducklings, waiting for directors to come along and show them how to walk, and where to fly. Nostalgia for diverse fortresses—not all of them built in the early fifties, when so many were going up: Wright's Rosenbaum house of 1939, his added wing in 1948, the Shoals Theatre the same year, and Disney's Fun and Fancy Free , also in 1948, at the Colbert or Ritz in Sheffield (memory-stain of three cartoon bears, Bongo, Lulabelle, and Lumpjaw, superimposed over a rear-window view of O'Neal Bridge on the drive back across the Tennessee River from Sheffield to Florence—who cares, so what, totally arbitrary, yet indelible). Fortresses like Florence, the FBI, Bird of Paradise , Don McNeil's Breakfast Club , Rosemary Clooney, and Israel, built to keep all kinds of gooks out—and in.

Was life any simpler then? I doubt it. But most of 1951 is forgotten now, including what was complex. What's left isn't an eight-year-old spectator—a

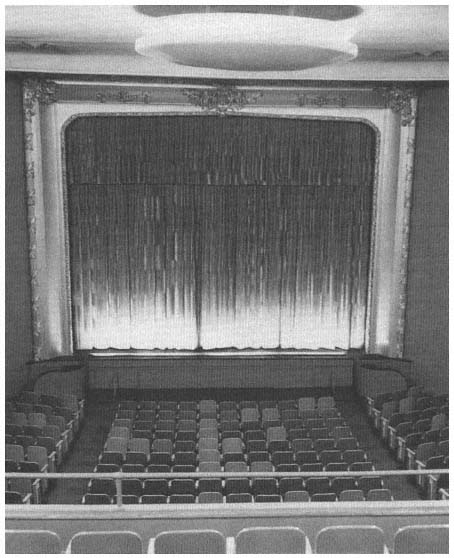

moody and solitary comic book artist and collector whom no one remembers clearly, least of all himself—but a movie called Bird Of Paradise . Seen originally on a big screen inside a gold proscenium wild with filigree (a roaring lion's head its centerpiece) while seated under a huge glass chandelier, an overhanging monolith that instilled excited tremors ever since Claude Rains had sawed an even bigger one loose over a full house in The Phantom Of The Opera at the Princess the year before; seen now on a little twenty-four-inch screen under a hanging plant. (A mile away, the site of the old Princess is the empty space of a parking lot, the building having been leveled in 1968 to expand the even rows of cars behind the First Presbyterian Church, as neat and orderly as the graves in a cemetery, thus inverting the process whereby the Athens Ritz emerged from another place of worship.)

Bird of Paradise , allowing memory limited access to such reference points. Why are they needed? To mark the memory-stains that form the surfaces and textures of one mind's entry into film, staking out the specifics of its desires, whether these be Terry Moore or MGM musicals or Lassie or Fernando Lamas, waterfalls or creeks or camera movements or pastel colors—the extent of the world that was wanted then, when Florence and what arrived there was everything that existed. For Ron it was a halfway station between Tarzan and Steve Reeves in Athena —long before the alienated decadence of a Stay Hungry , based on a Birmingham gym where Ron used to work out. For Patricia it marked a different kind of middle ground, a giant image of Debra Paget somewhere between the lurid and inviting posters of Silvana Mangano in Bitter Rice and Jennifer Jones in Ruby Gentry . For me the breaking of religious taboos and the presence of Debra Paget offered a carnal image that was rekindled recently on a return trip to London, when I saw subtitled prints of Fritz Lang's glorious The Tiger Of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb . (There the image is reduced to algebraic essentials of voyeurism—a formula refined even further with Dawn Addams in Lang's subsequent and final film, The 1000 Eyes Of Dr. Mabuse , as lean and functional as an architectural blueprint.) For all of us, it was like a first kiss of pantheism, a blueprint that creeks, lakes, waterfalls, streams, oceans, fields, and stars had already suggested, but one that only a movie could prove , by ordering and illustrating a world for all to see. We didn't talk or think about good photography in those days, only about good trees.

Bird of Paradise ! Don't know, will never know again whether the cartoon that day at the Princess was a Mighty Mouse or something else. The ads in the Florence Times don't say, and the only record of that booking in Florence—probably made by Beulah Sutton, a bookkeeper who worked in the offices upstairs at the Shoals and ordered most of the short subjects from Atlanta—would have been in one of those countless ledgers that my father turned over to a trucker in 1960, after the business was sold, to carry to the paper plant. The cost of trucking the damn things equaled what the plant was

Remodeled Princess (the Cinema), 1958

willing to pay for the clutter—which meant the ledgers weren't worth a plugged nickel to anyone, practically speaking. As any self-respecting Alabamian would rightly point out today, the information of what cartoon showed with Bird of Paradise at the Princess isn't worth diddlyshit. Neither are most of the other vestiges of unofficial pasts that we no longer inhabit.

Bird of Paradise ! There were other escapes, to be sure, in the early fifties—Queen for a Day, Whip Wilson, crossword puzzles. My father's Sunday column for the Florence Times occasionally suggested a few combinations:

"M-m-m-m-m" is the word for the movies showing this week at Muscle Shoals Theatres.

You can take this as a fervent murmur of appreciation for Marilyn Monroe, who is one of the stars in "Clash By Night." Or for the luscious blonde who provides the bait in "Man Bait."

Or you can take it as a reference to the manifold multiplicity of the letter M in this week's movies.

As in "Maru," Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery (George) and "Man Bait."

Of course, if you were disposed to be argumentative, you could make out a pretty good case for the letter R instead, what with Ruth Roman, Robert Ryan and the fact that the recent releases represented locally this week are rather Romantic.

But enough of all this.

(Except Marilyn! Never enough of Marilyn!)

God, he must have been bored then. Around the same period, August 1952, he toyed with the notion of pairing The Iron Mistress and Clash By Night on a theater marquee. The idea for a double feature persisted as a gag, but this was the early fifties and the match never took place.

(This isn't all that was going down in that period, a liberal, up-to-date auteurist critic might argue. Look at a director like Douglas Sirk, who was confronting the same audiences and Hollywood genres and subverting them both with ironic social critiques—even though hardly anyone was aware of it at the time. Okay; the gods of TV programming decree that I'm able to see Sirk's 1952 No Room For the Groom in Florence three nights after Bird of Paradise , broadcast by WTCG, from Atlanta. Tony Curtis marries Piper Laurie on a short GI leave and, due to diverse comic complications, isn't able to sleep with her. When he returns months later, a crowd of her cousins, invited by her monstrous mother [Spring Byington], are occupying every room in the house, and it takes him the remainder of the movie to consummate his marriage.

Actually, this low-budget black and white nightmare sums up the Pete Smith Specialty, the Joe McDoakes comedy, and the Goofy cartoon, three

characteristic manifestations of the period—like Jiggs and Maggie and impotent old Major Hoople—stretched out to excruciating, sadistic feature length. No death and resurrection, as in the later Road Runners, but a continuity and immortality of petty domestic pain that inches forward slowly and relentlessly, blocking libido on all sides, at every turn: Pete Smith's anonymous, voiceless dumbbell hero stepping on a garden hoe and the soundtrack going boiing, Hoople muttering incomprehensibly into his vest at his boardinghouse table, and McDoakes, once again defeated, retiring with a philosophical shrug to his old position behind the pre-Oldenburg eightball of the end title.

The crushing landslide of family, greed, stupidity, hypocrisy, ugliness, and complacency in these worlds made a Bird of Paradise everything its title claimed it to be. Had I seen Sirk's perverted hate letter to America in 1952 at the Norwood—shown by a competitor of the Rosenbaums who got all the Universal movies first-run—I might have giggled some, but it wouldn't have nurtured any dreams. The erotic interruptions of Steinberg's The Devil is a Woman and Buñuel's That Obscure Object of Desire are conceived sensually, but No Room for the Groom is so mangy-looking that eroticism can be posed only on a hypothetical level before it gets canceled.

Sirk's world without alternatives, like Fassbinder's, is never far from the inertia that engulfed the early fifties in America—not so very different from the all-tabloid media presiding today, punched up and juiced to the point of immobility, drowning in its own fat. Looking back on former inertia with a mixture of nostalgia, fondness, and cold irony is taken in some quarters to be somehow akin to "subversive" leftist politics, yet it is difficult to see how: Sink's and Fassbinder's critiques remain conservative gibes in relation to their respective periods—W. C. Fields-like grumbles and cynical little pokes rather than critical assaults against worlds that are defined by their inability to change, hopeless worlds such as the mental lives of small towns like Florence, in love with itself even as its buildings are being recycled into shopping malls. Worlds like that of Bird of Paradise , a racist film with the same degree of Brechtian self-reflection that can be found in Sirk's Imitation of Life or Fassbinder's Ali —no more, no less, for better and for worse. If the old critical tools are being recycled into auteurist or "structuralist" grids, the purpose is precisely the same: for your shopping convenience.)

Bird of Paradise ! As an American friend in London once described The Best of Everything (1959), it's a movie with lots of text. And part of this text is a particular conjunction of time and space: a spring already warm enough for swimming, after a weekend spent at the Country Club pool or riding on a farm the horse that my brothers and I owned, or exploring and traversing portions of a whiterock creek across the field next to my house—and Sunday school that very morning at the reform Jewish temple in Sheffield, across the river. A spring that was already summer, six weeks before I

was leaving for Camp Blue Star in Hendersonville, North Carolina. What else was happening on May 13? It was two days after David's tenth birthday and Bugs Bunny was sneezing into his glass-blower; Mr. Botts in Priscilla's Pop fell off his roof and into his wife's favorite rosebush, and Secretary of Defense Marshall was reported saying that "we are moving towards success" in ending Red Chinese aggression in Korea but warning (according to the Florence Times ) that Russia is the "real opponent" who could plunge the world into war. Only the week before, David Ben-Gurion of Israel had arrived at the Muscle Shoals airport for a tour of TVA installations, accompanied by an official party of over a dozen people—including Bo and Mrs. Golda Meir, minister of labor—and David R. had snapped some shots with his Brownie while Stanley took home movies.

Bird of Paradise ! Crashing into the drab surface of a year that up to then had mainly been in black and white, from winter trees and dirty laundry sky to Zandorra, World Famous Mystic, on stage at the Shoals and Colbert theaters twice daily, who wore black spidery dresses and told members of the audience what they were thinking; black and white like Ben-Gurion, his hair, and the clouds he came from; like Harvey and For Heaven's Sake , Mad Wednesday and The March of Time; like Alfalfa in Our Gang comedies and Rootie Kazootie on the television set you saw in a window, The Fuller Brush Girl and The Mudlark , At War with the Army and In a Lonely Place , vanilla frozen custard, The Next Voice You Hear and Watch The Birdie , Mr. Music and Mrs. O'Malley and Mr. Malone ; black and white like nearby Wilson Dam, The West Point Story , the preview for The Mating Season , and Whiterock Creek. Crashing into ripples like a stone plunked into a lagoon, rainbow fragments rushing off in all directions. Like the Noah's Ark rainbow appearing on the island one day to bless Kalua and André's love, "It is the best of signs," which makes the natives drum out the happy news on enormous tree trunks, sending out radiant signals that bring everyone running, then sitting together in a circle where Kalua dances for André; and afterward, still daytime, everyone in the tribe lying in a peaceful row on mats on a long, cool porch. Kalua and André, in the midst of the commune, wake, lie facing one another, kiss.

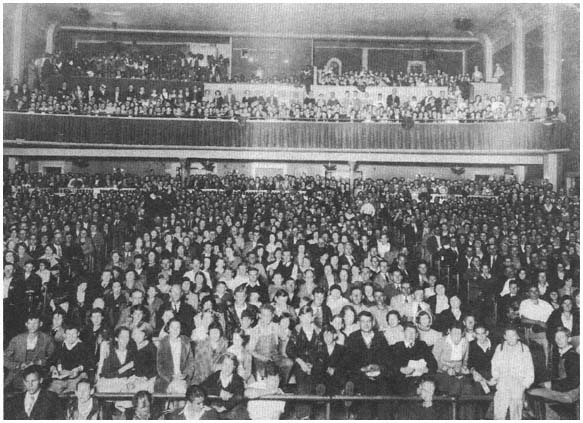

Bird of Paradise ! Another bird, another paradise was being unveiled that Sunday at the all-Negro Carver Theatre in Sheffield, next to the railroad tracks, a program of films by Will Cowan, starring "Sugar Chile" Robinson, Billie Holiday, and Count Basie—but I didn't know that then. I didn't know much either about the dark laughter coming from the colored section of the Princess balcony. Instead, I was responding to the Tropical Life Saver colors of Hawaii, where Daves's movie was actually shot, which seemed a fair approximation of heaven after such versions of relative familiarity as Father's Little Dividend and Born Yesterday at the Shoals earlier that May. David and

Colbert Theatre, Sheffield, Alabama, 1951

Princess audience in the 1930s (colored balcony in upper left)

I get in for free—greeting, as usual, Elmo the manager and Mr. Richie the ticket taker—and it costs Ron a dime. On the way out, David says he likes the movie and I say that I don't. We're always like that, David liking movies with tragic endings and me hating them; ten weeks later, he's enthusing over The Great Caruso while I find myself in tears after hearing only the plot—to which our father adds the plots of Hamlet and Oedipus Rex, explaining what tragedy is all about, which makes me sniffle that much more.

Bird of Paradise ! Shown only a month before the Majestic in Florence and the Ritz in Sheffield played their last programs for all eternity on the same Saturday night: at the former, Bar 20 Rides Again with Hopalong Cassidy and Fugitive Valley with the Rangebusters; at the latter, The East Side Kids, in Early America with Bill Elliott, and the last chapter of Radar Patrol vs. Spy King and the first episode of Desperadoes of The West . . . an uncompleted cycle for how many kids that day? And afterward how many tortured, unfinished dreams haunted the Majestic when it was used as the local Stevenson-Sparkman headquarters in 1952, or the Ritz when Bobby Denton recorded there for Tune Records in 1957?

Bird of Paradise ! A phoenix whose cycle is never finished, a few sparks striking one side of a sibling rivalry and igniting a blasphemous dream of genocidal suicide that scared me so much I had to reestablish contact with both fathers, on earth and in heaven, one at a time. The second one, whom I prayed to at night, gradually faded away after 1954 and the first one helped me to loosen that tie by presenting his own atheism to me, for the first time, after I had staggered out of nightmare and bed, down the hall, through the dining room and living room to his snug study, the only lighted room in the house. Today, when my nomadic life often seems to be the most Jewish part of me, the closed, perfect world of Bird of Paradise in its initial unveiling still holds delicious configurations, at least until it gets to the mountain. Then the red coals and volcano come on more like show biz revelations of nature's dark underside with folkloric trimmings, like that frenetic Depression musical King Kong , and I'm reminded, yes, that mercy and moral absolutes were the messages handed down to Abraham and Moses on their respective mountains. But sacrificial and punitive demands were also made of these men—in Abraham's case before, in Moses' case afterward. And something gets lost and trampled in the process, a jarring change of gears such as one would experience by seeing Looking for Mr. Goodbar immediately after Close Encounters of the Third Kind . America calls it growing up; I say it's spinach. Spinach lost and spinach gained—and most nights now, in most towns and cities all over the country, there's nothing else for supper.