An Examination of Some Representative Treatments of Trade Goods

Much of our misunderstanding can be attributed to false assumptions about Native American culture. Some of these may be discerned in what is nonetheless an excellent survey of relevant literature by Guy Prentice, which deals with a sort of trade object employed by Mississippian societies from A.D. 1000 to 1400, just prior to European contact. These objects were marine shell beads and columellae. Prentice argued that marine shells should not be regarded as, primarily, status items, the usual interpretation of this material. Instead, they should be regarded as "wealth items of extreme tradeability (i.e., a form of primitive money) and secondarily as status items."[9] In making this argument, Prentice cited the ethnohistoric record and archaeological data and provided what he called a "wealth item model" for marine shell bead use that he thought explained this data better than did the status thesis. Prentice noted that the context in which marine shells have been found at archaeological excavations, often in burials, has encouraged the interpretation of their use as status markers. Commenting on this, he quoted Hodder as saying that we "must not expect simple correlations between social organization and

burial."[10] More than status is signified by burial symbolism, he argued, including "ideas concerning death in general, and notions regarding those aspects of social life which should be represented in death."[11] While these comments are a bit vague, they do hint at a value and belief system concerned with more than just status, per se. More convincing for his case is the volume of ethnohistorical evidence he amassed that shows that marine shell items were used by Native Americans, and other traditional peoples, not only as symbols of rank and status but also as a form of wealth. He cited Jane Safer and Frances Gill, who studied the Yurok of northern California:

Tusk shells could purchase a wide range of goods, whose prices were fairly standardized, and virtually all obligations and services from bridewealth to blood debt for murder were valued in tusk string shells.

The Yurok were preoccupied with the acquisition of wealth, in the form of tusk, shell strings, and also woodpecker scalps and obsidian. They believed that if a man fulfilled all religious obligations meticulously, not only would he have luck in hunting, he would draw tusk shells to himself. A large collection of tusk shell strings did not automatically confer prestige, but it was a necessary prerequisite: High status in the community could not be achieved without such a collection.[12]

Safer and Gill also reported on the Pomo of central California, who made shell "money" from the Pismo clam. These cylindrical beads could be owned by men and women and were used to purchase food, bows and arrows, animal hides, baskets, and a host of other things. They concluded, "In most societies where individuals can accumulate wealth, riches and high status go hand in hand."[13] Prentice concluded that "it is this relationship between status and wealth which makes the concept of wealth so important in archaeological and anthropological studies."[14]

Prentice fit all of his data into a body of well-established anthropological theory, most of which posits that the "rise" of less-complex societies to more-complex societies (that is, chiefdom societies from big-man societies, and states from chiefdoms) "may be directly attributable to (although not entirely dependent upon) the ability of the elite to control wealth."[15] Even the very simple big-man society, he noted, depends upon the capability of big men to accumulate and redistribute wealth.

The problem with Prentice's idea concerning the centrality of "wealth" in traditional societies, even the role of wealth in the evolution of society, is that he was using a term that is tied to a very modem notion, that of abstracted, standardized value—a term "steeped" in modernity, abstraction,

and the removal of the subject from the object or immediate experience. All objects in traditional societies signify something much more complex than abstract wealth. (I would maintain that they do this also in modem societies, although perhaps to a lesser degree, but I will not make that argument here.) Prentice was using a modem cultural context in his attempt to explain traditional phenomena. To understand more completely, we must try a bit harder to see the world according to tradition.

A way to do this was provided by the early cultural observer, Marcel Mauss, in his classic, but now frequently overlooked, The Gift. Mary Douglas speculated in a foreword to a recent edition of this as to why "this profound and original book had its impact mainly on small professional bodies of archaeologists, classicists, and anthropologists."[16] She suggested that Mauss and Durkheim represented a kind of social democracy that opposed (perhaps it would not be too much to say, existed in binary opposition to) an Anglo-Saxon utilitarianism, a Social Darwinism. The debate between these two positions was eclipsed after the First World War by that between social democracy and both fascism and communism. Once political fashions again changed, Douglas saw the chance to utilize Mauss to once more engage and contest the idea of "methodological individualism" (or the idea that the individual is the prime mover in society).

Whatever the merits of Douglas's evaluation of intellectual trends, The Girl provided a cultural perspective that more closely approximates the traditional apprehension of exchange and of the material objects involved in that exchange. Mauss noted that exchange in traditional societies (which he also called primitive or archaic societies) is always characterized as gift giving. The giving of gifts is always described by informants in these societies (and, therefore, probably conceived of consciously) as voluntary. In fact, as Mauss's fieldwork and scholarship (since bolstered by any number of other studies) clearly demonstrated, both the gifting and the reciprocation of the gift in one form or another is strictly prescribed by the traditional culture . Mauss asked, rhetorically, "What power resides in the object given that causes its recipient to pay it back?"[17] The answer to this, of course, is that the object itself has no "power" or "meaning" (and, for that matter, no "value" in the abstract modern sense, either), power is culturally inscribed—and inscription, for the most part, is achieved through the ritual that accompanies both gifting and the reciprocation of the gift.

Mauss referred to this sort of ritual exchange as a "total" social phenomenon, total because it involved all aspects and institutions of society: economic, religious, moral; forms of production and consumption; political and familial units.[18] One might well argue that this occurs, in part,

because traditional societies are not as differentiated as modem ones; firm distinctions do not exist between institutions, or between functional segments. In what could well serve as a reply to Prentice, Mauss said this about the exchange practice in traditional societies:

Yet the whole of this very, rich economy is still filled with religious elements. Money still possesses its magical power and is still linked to the clan or to the individual. The various economic activities, for example the market, are suffused with rituals and myths. They retain a ceremonial character that is obligatory and effective. They are full of rituals and rites.[19]

There are other differences between uses of wealth in traditional and modern societies:

They hoard [in traditional societies], but in order to spend, to place under an obligation, to have their own "liege men." On the other hand, they carry on exchange, but it is above all in luxury articles, ornaments or clothes, or things that are consumed immediately, at feasts. They repay with interest, but this is in order to humiliate the person initially making the gift of exchange, and not only to recompense him for loss caused him by "deferred consumption." There is self-interest, but this self-interest is only analogous to what allegedly sways us.[20]

In part, Mauss drew upon Bronislaw Malinowski's Argonauts of the Western Pacific for data with which to bolster his characterization of traditional exchange."[21] Malinowski emphasized the eclectic nature of this; the ritual mixes things, values, contracts, and men together.

The centerpiece of Malinowski's study is the famous kula ring, a phenomenon that attracted a great deal of Western attention precisely because it appeared so nonsensical to modernist observers. The kula ring refers to a system of ritual trade of vaygu'a, "a kind of money," which is of two sorts. The first of these are the mwali, bracelets carved and polished, which are kept in a shell until great occasions when they are worn by their owners or the owners' relatives. The other form of vaygu'a are the necklaces called soulava, which are carved from the mother-of-pearl of the red spondylus. The chain of islands involved in the kula trade forms a circular pattern. The mwali are always traded in one direction, the soulava in the other. Only certain persons of high prestige are permitted to own the vaygu'a, and these individuals may own them several times over the course of their lives. Ownership, then, is of a particular sort: one may not keep these items too long, and they may only be traded in a kula ceremony. The vaygu'a eventually build upon a history, a story that is told about who

has owned them and the circumstances of their exchange; eventually, each is given a name and is attributed with a personality. Some persons take their own name from that of an especially admired vaygu'a. The objects become sacred. Malinowski noted that to have such an object in one's possession is "exhilarating, strengthening, and calming in itself."[22] So strong is their power that vaygu'a provide solace to the dying: They are rubbed on the dying person's stomach or placed on his forehead, for example, as if the association with the sacred object could imbue his life, quickly passing away, with meaning. This power appears analogous to the medicine of the Plains Indians.

At the same time as the kula —at the intertribal fairs that accompany the kula ceremony—the Trobrianders practice the gimwali, a much more "capitalist" affair in which an economic exchange of useful goods is conducted. Hard bargaining is done here, of the sort that would be totally inappropriate in a kula. Mauss summarized the role of the kula as follows:

The kula, in its essential form, is itself only one element, the most solemn one, in a vast system of services rendered and reciprocated, which indeed seems to embrace the whole of Trobriand economic and civil life. The kula seems merely to be the culminating point of that life, particularly the kula between nations and tribes. It is certainly one of the purposes of existence and for undertaking long voyages. Yet in the end, only the chiefs, and even solely those drawn from the coastal tribes—and then only a few—do in fact take part in it. The kula merely gives concrete expression to many other institutions, bringing them together.[23]

I would like to emphasize certain points taken from the above description of the kula exchange, which Mauss held forth as representative of exchange in traditional societies. First, not all of the goods exchanged are imbued with the magical power of the vaygu'a, a power which Mauss indicated is enough to give meaning to Trobriand existence, and one that transforms the vaygu'a into the most valued of Trobriand objects. The vaygu'a derive their power, then, from the kula ritual. Ritual, as Mauss's teacher Emile Durkheim stated, produces sentiment, an affective response which forms the shared, internalized values and beliefs common to traditional societies. This commonality of belief and value Durkheim termed mechanical solidarity, drawing a parallel to the most simple biological organisms, which display a mechanical structure in the sense that each cell in such an organism (for example, a sponge) is so much like all other cells in the organism that a cell or group of cells may be removed without destroying the unity or viability of the parent organism.[24]

Social relationships in such societies are paramount, those between the individual and her or his close and extended family being most influential. Ritual works to reaffirm an individual's place in this constellation of relationships and to create other, fictive kinship relationships. Such relationships are regarded as being cosmically and supernaturally ordained. As Durkheim noted in The Division of Labor, "if there is one truth that history teaches us beyond a doubt, it is that religion embraces a smaller and smaller portion of social life. Originally it pervades everything; everything social is religious."[25] Further, as Mircea Eliade has convincingly shown, ritual inevitably refers to mythological occurrence, replicating the actions of the deities and ancestors, and in that way legitimating and sacralizing the relationships reinforced or produced by ritual.[26]

Often, the primordial state in which these mythological events transpired is replicated also. This primordial state is a time and place before the advent of history, in which the bounds of reality as it is now experienced did not apply. Various means are used to achieve such a state, including fasting, sleep deprivation, self-mutilation and torture, and the ingestion of drugs. The Sun Dance of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux and the variations of this ceremony practiced by several other Plains tribes include many of these means. Visions that thenceforth provide guidance are experienced in the primordial state.

Some attempt to replicate or, at least, refer to the primordial state is made in rituals of lesser significance, including trading ritual. Plains Indian groups invariably smoked tobacco during exchanges of goods, so much so that the trading of horses was called "smoking over" horses in historic times. Donald Blakeslee and, before him, Joseph Jablow had convincingly established that such behavior is a continuation of the tradition of the calumet ceremony .[27] As Jordan Paper noted in his recent, comprehensive study, "the centrality of the pipe to the religious life and understanding of many native peoples of North America can best be compared to the role of the Torah in Judaism and the Koran in Islam; it is the primary material means of communication between spiritual power and human beings."[28] The calumet ritual was a crucial element in the trade at Bent's Old Fort.

Tobacco was, thus, not only an important trade item but also a substance made use of in the trading ritual to replicate the primordial state and enhance the efficacy of the ritual. Its psychotropic, and cultural, effects should not be underestimated. Joseph C. Winter makes a clear case for the use of tobacco as a psychotropic. He begins by reporting on the work

of Johannes Wilbert, who conducted a study of the connection between tobacco use and shamanism in South America. Wilbert concluded that "Shamans use enormous amounts of tobacco to achieve effects that confirm the most central tenets and beliefs of their religion."[29] In fact, shamans aim to experience acute nicotine intoxication, stopping just short of using the drug in amounts that would be fatal. The resulting visions are interpreted as legitimizing cultural institutions and normative behavior. Winter goes on to say:

From southern Alaska to southern Chile, tobacco has been used for religious, economic and social purposes, and for many Native American groups, it serves as an important medium of energy exchange. Among the Warao, for example, who live in a region of the Orinoco Delta where it cannot be grown, the acquisition of tobacco for use by heavily addicted shamans, requires a large expenditure of physical energy by the rest of the populace. Trade goods have to be prepared, such as manufacturing hammocks and baskets, catching colorful birds, and training valuable hunting dogs, then the goods have to be exchanged with tobacco-producing groups on long distance trading expeditions. High amounts of energy are also exchanged by the shaman and his people during numerous public ceremonies, rituals, seances, and curing events, all of which involve the consumption of enormous amounts of highly potent tobacco.[30]

The ritual importance of tobacco was perhaps not so exaggerated among North American Native American groups as among those in South America. Nonetheless, as Mary Adair has stated, "no other plant figured so prominently in religion and secular ceremonies, rites of passage, economic and Political alliances or social events and relaxation" among North American groups considered as a whole.[31] It is also well documented that tobacco was among the most intensely desired trade items by these Native Americans.

Winter sought to establish the antiquity of the traditional use of tobacco by the natives of North America by dating the spread of the plant in the Western Hemisphere. He noted that the range of the occurrence of some species of tobacco plants moved rapidly southward from North America just after the Pleistocene, that is, just as humans reached those areas of South America. The strong implication here is that humans acted as the agency by which tobacco, which requires cultivated or disturbed soil in which to grow (and is almost unknown in the wild, at present), spread over the New World. Winter suggested that this may have occurred as early as 9000 B.C. [32]

This is supported by a line of ethnological logic, advanced notably by

Weston La Barre, but also by Wilbert, Peter Furst, and von Gernet, that the earliest inhabitants of the New World, the Paleo-Indian big game hunters who crossed over the Bering Land Bridge 12,000 to 14,000 years ago, would have possessed a shamanistic religion.[33] These religions predictably employ psychotropic drugs for visions and out-of-body experiences. Groups with shamanistic religions would have quickly realized the utility. of tobacco to that end. Winter went so far as to say that "eventually, even the religions of the Native Americans became organized in one degree or another around it, as even their gods became addicted to it."[34] Winter pointed out another very significant aspect of the tradition of tobacco use by Native Americans: that the deliberate growing of tobacco in Paleo-Indian or even Archaic times would constitute the origins of agriculture; that is, agriculture would have been initiated not for the production of food, but for drugs employed in the replication of the primordial state.[35]

Tobacco was highly valued by Native Americans because of its religious and ritual associations. It seems possible that alcohol held a special appeal to Native Americans for the same reason. There existed among Native Americans a strong tradition of shamanistic ecstasy and a concern with the power associated with visions thereby induced. Native Americans, however, were not oblivious to the double-edged nature of alcohol use. While describing the historic liquor trade with Native Americans along the Arkansas River, LeCompte noted that the Cheyenne disdained the use of alcohol for many years. They were finally persuaded

to try it by trader John Gantt in 1832 or 1833, when he added sugar to

whiskey in order to make it more immediately appealing to the Native Americans.[36]

Within a decade the Cheyenne had developed major problems associated with the use of alcohol. Already by 1835, the Cheyenne informed a Colonel Dodge at Bent's Fort that "in arranging the good things of this world in order of rank . . . whiskey should stand first, then tobacco, third, guns, forth, horses, and fifth, women."[37] Indian Superintendent William Clark had observed at about the time Gantt deceived the Cheyenne into imbibing alcohol that after a single drink "not an Indian could be found among a thousand who would not sell his horse, his gun, or his last blankets for another drink."[38] LeCompte further noted that whiskey was not only the most demanded, but also, by far, the most profitable trade item. Even "friends" of the Indian, who were on the one hand appalled at the devastation inflicted upon the Native Americans, were, on the other hand, amazed at the profitability of the trade in alcohol and unable to resist par-

ticipating. Jim Beckworth, known and respected as "Yellow Crow" to the Cheyenne, explained as follows:

Let the reader sit down and figure up the profits on a forty-gallon cask of alcohol, and he will be thunderstruck, or rather whiskey struck. When disposed of, four gallons of water are added to each gallon of alcohol. In two hundred gallons there are sixteen hundred pints, for each one of which the trader gets a buffalo robe worth five dollars![39]

It is interesting that both Euro-Americans and Native Americans succumbed to the seductions characteristic of their respective cultures. LeCompte makes an observation that coincides with my own conclusion concerning the circumstances of traders active in the Southwest:[40] the Anglo trader was not infrequently someone who could not enter economic systems in the East or in Europe. This is exemplified by the principals of the Bent & St. Vrain Company. Ceran St. Vrain was a younger son of a deposed French nobleman who had died insolvent when Ceran was sixteen. The Bents were born into the large family of Judge Silas Bent of St. Louis, a respected man, but one without the considerable financial resources it would require to maintain the social positions of all of his offspring. Such people were born into a society where a secure position and, consequently, an identity. were dependent upon amassing wealth. Beckworth, a mulatto, was an employee of the Bents and in a sense their protégé. For all of these individuals, the decision to pursue the difficult and dangerous life of a fur trader could be characterized as a gamble taken to secure a stable identity: It was evidently a gamble desperate enough to cause them to overlook the moral qualms they had about contributing to the misery that alcohol was inflicting upon the Cheyenne. Though there is evidence that the Bents themselves tried to ration alcohol to the Cheyenne, and thereby lessen the damage, there were scores of traders eager to provide alcohol in large quantities (like John Gantt) for every relatively ethical trader, like the Bents.

One can, I think, intuitively understand the appeal of liquor to Native Americans as one becomes aware of the extent to which the sustaining structures of their culture had deteriorated over the previous three hundred years. The disease, social dislocation, and changes in ways of life have been amply documented. Certainly alcohol would have had its customary effect of at least temporarily ameliorating anxiety by inducing an emotional state of Olympian detachment and omnipotence. It is interesting to speculate, too, that in the extreme effects of alcohol the Native Americans might also have been seeking a return to the primordial chaos that

was a part of their shamanistic religion, with the hope that a new world might be constructed by means of this experience. Whatever the validity of this idea, it is suggestive that tobacco and alcohol were obviously not desired for their usefulness in any technoeconomic sense, but that they were nonetheless among the most valued trade items.

The ritual aspect of exchange renders it into what Mauss referred to as a "total" social phenomena, in which all kinds of social institutions are given expression simultaneously.[41] Two classic ethnohistories of Plains Indian groups take note, at least implicitly, of this view of trade: Oscar Lewis's The Effects of White Contact upon Blackfoot Culture and Joseph

Jablow's The Cheyenne Indians in Plains Indian Trade Relations, 1795-1540 .[42]

These works are similar, and neither deals with the more explicitly semiotic aspects of trade goods. Both do, however, clarify that trade prior to and just after contact with Anglos was characterized as gift exchange, that the exchange was accompanied by a variety of rituals, including the smoking of tobacco (so much so that the ritual exchange was referred to as occurring "under the pipe"), and that fictive kinship relations were established. Such kinship relations were often made more important by the practice of cross-adoption: Each group would adopt children from the other. By the early nineteenth century such trade among Plains Indians had become quite complex. More European trade goods, especially firearms, had complicated the equation, as had the increasing friction and competition between groups brought about by jockeying for position within the trade.

Jablow presented an eyewitness account of a three-way exchange between the "Big Bellies" (the literal translation of the Gros Ventres), the "Schians" (the Cheyenne), and the Hidatsa, which occurred in about 1805 at a Hidatsa village in which this tension is obvious. After some preliminary rituals, which had gone well until the unexpected arrival of some Assiniboin who were enemies of the Cheyenne but were nonetheless taken under the protection of the Hidatsa, the exchange began in earnest. The presence of the Assiniboin was an obvious source of discomfort to the Cheyenne:

The Big Bellies brought in some ammunition and laid it upon the shrouds; the son (adopted by Le Borgne, the Hidatsa chief) was directed to lay the stem (pipe) over these articles, which he did accordingly. Our old general was again posted opposite the entrance of the shelter, where he was fully employed in his usual vocation of hanging, inviting everyone to put something under the stem. But all his eloquence was in vain; not a Schian came forward until some of their old men had gone the rounds making long

speeches, when a few of the Schians appeared with some garnished robes and dressed leather, which were spread on the ground near the bull's head, which was then laid upon the heap. The Big Bellies then brought two guns, which they placed under the stem. The Schians put another one or two under the bull's head. Our party were each time more ready to come forward with their property than they were with theirs. The latter next brought some old, scabby sore-backed horses for the bull's head. This compliment was returned by our party with corn, beans, ammunition, and a gun. General Chokecherry grew impatient, and reproached the Schians in a very severe and harsh manner for their mean and avaricious manner of dealing, in bringing forward their trash and rotten horses, saying that the Big Bellies were ready to give good guns and ammunition, but expected to receive good horses in return. In answer to this they were given to understand by the Schians that they must first put all their guns and ammunition under the stem, immediately after which the Schians, in their turn, would bring in good horses. As it was never customary in an affair of this kind for either party to particularize the articles to be brought to the stem or bull's head, but for everyone to contribute what he pleased of the best he had, this proposal induced our party to suspect that the Schians had planned to get our firearms and ammunition into their possession, that they might be a match for us, and commence hostilities. To prevent this, no more guns or ammunition were brought forward, and the Schians were told they must first produce some of their best horses; but to this they would not listen. After a few more trifles had been given on both sides, the business came to a standstill on the part of the Schians, who retired to their tents.[43]

Evident here is the breakdown of the ritual aspect of trade that evolved in the nineteenth century. This breakdown had implications internal to trading groups. With emphasis on profits to be derived from trading and the amassing of wealth, rudimentary class differences sprung up among what had been, essentially, egalitarian social organizations among Plains Indians. Horses continued to be a sign of wealth (but one that also sign fled a number of other personal attributes about the owner, including prowess in war), but as the trade in buffalo robes grew, men with many horses exchanged them for multiple wives. More wives could process more buffalo hides to robes. There was even an economy of scale in operation: Jablow noted the case in which a Blackfoot chief reported that his eight wives could transform 150 buffalo skins to robes in one year, whereas a single wife could only have processed ten.[44]

Differences in wealth were soon reflected in other areas of society, as Lewis observed.[45] Only the well-off could afford to buy firearms and ammunition, dried provisions, a good horse, and protective war charms needed for raids and battle. The poor, then, rarely led raiding parties and

were therefore deprived of the opportunity to establish themselves in more general leadership roles. Even in the realm of the sacral, wealth differences had an effect. War bonnets, elaborate headdresses, medicine pipes, and other sacred objects, while they could perhaps in every case not be bought, were now more accessible to wealthier individuals. The rich could achieve and be recognized by virtue of better war equipment and their ability to draft other individuals of lesser wealth into their war parties.

Ritual in such circumstances becomes less the apparent agency by which meaning is attached to material items. I suggest here, though, that ritual is only, in Mauss's term, degraded. (In a more fully modern society, ritual is even better described as fugitive .) It still has a great effect, although the effect of ritual becomes more obscure as formal ritual breaks down. Nonetheless, the meaning and value of an object is still determined by its continuing association with a formal ritual, which may no longer be practiced, or by association with a degraded ritual, which refers to mythological occurrences in a manner less formal, less obvious, and perhaps even more within the realm of the subconscious.

As an example of this, consider the ritual of exchange as experienced by the Euro-American trade partners. On the surface, their behavior might appear to be, and may have seemed to them to be, motivated entirely by the "rational" desire for profit. Their behavior nonetheless had as a referent the mythology of capitalism and modernity, associated with what Tocqueville, and others since, have called the "cult of the individual." This value and belief system dictated what was necessary and proper behavior.

When considering trade objects exchanged in the nineteenth century, an era that saw the increasing degradation of trade ritual, it is perhaps easiest to understand the symbolic value of trade objects in general by looking first at those objects associated with the most obvious and undegraded ritual. Francis Paul Prucha's book, Indian Peace Medals in American History, provides an example of a class of objects with quite obvious ritual associations.[46] At the same time, these items subverted the ritual Native American "gift" economy. Peace medals manufactured for the Indian trade as gift items were quickly recognized as essential to the establishment of an Indian policy. As the head of the Indian Office, Thomas L. McKinney said in 1829, "without medals, any plan of operations among the Indians, be it what it may, is greatly enfeebled."[47]

The British, French, and Spanish had distributed such medals for decades prior to American independence. The American use of these

medals was similar to that of the Europeans: they were given to Native American leaders on ritual occasions such as the signing of treaties, visits to the nation's capital by Indian chiefs, or during tours of the frontier by government officials. The Native Americans were, typically, anxious to substantiate social relations with powerful exchange partners: "When the United States replaced the British, the Indians were eager to obtain symbols of allegiance from the new Great Father."[48] On their side, Americans wishing to establish friendly relations with a tribe would attempt to collect all the medals given to their new trading partners by the former powers, usually the Spanish, French, or British. Americans were well aware that these exchanges symbolized the formal shifting of allegiances. About one such incident, a British officer commented, "Formerly a chief would have parted with his life rather than his medal."[49]

At first the medals used by Americans were struck in silver with the image of George Washington. They were among the most cherished possessions of the recipients and became a symbol of their authority. Often, they were buried with chiefs or passed down from generation to generation. Soon, however, wading companies began to manipulate these symbols to their benefit. They would strike their own medals, with likenesses of American presidents or of company officials. Initially, these too were of silver, but later silver content was much reduced or other metal was used. These medals were often given by trading companies to Native American individuals who might not be recognized as unequivocal leaders among their people but who were compliant to the interest of the trading company. In this way trading companies attempted to act as "king makers," placing in power individuals who would advance the interests of the trading company.

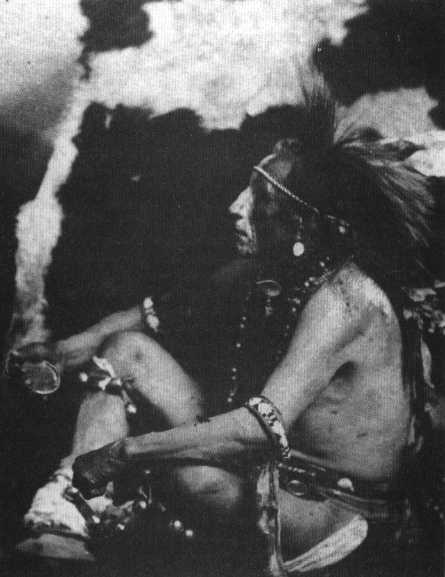

As set forth earlier, ownership or display of trade goods obtained through ritual exchange represented social relationships, ones sanctified by the reference to an archetypical, mythological relationship represented by the ritual. A clear modern example from our own society would be that of a wedding ring. As with a wedding ring, a symbolic object defines not only a social relationship, but the self constructed by means of social relationships. This explains the urgent concern of Native Americans about the display of such symbolic material; through display they defined themselves and their place in the world. Charles E. Hanson, Jr., revealed that the principal users of mirrors, another highly valued trade good, were men (fig. 14). While they were invariably used in preparation for war or ceremony, there are many eyewitness references to frequent and everyday use. A traveling warrior carried his weapons, a bag of red

Figure 14.

An early photo of a Sioux man, Louis Dog, using his hand

mirror. (Courtesy Museum of the Fur Trade, Chadron, Nebraska;

reported in Charles Hanson, Jr., "Trade Mirrors," The Museum

of the Fur Trade Quarterly 22, no. 4 [1986]: cover.)

paint, and his mirror, according to a colonial observer. A Sioux warrior is reported who rearranged his appearance, including his hair and makeup, five times a day. Hanson quotes the Santa Fe trader Josiah Gregg, who noted in 1844 that no warrior was equipped without his mirror "which he frequently consults. He usually takes it from its original case, and sets it in a large fancifully carved frame of wood, which is always carried about him."[50]

Mirrors were not common European items when the Indian trade began, but as soon as they were made in quantity they were provided to Indian traders. William Pynchon, an Indian trader from what is now Springfield, Massachusetts, had mirrors in his trading stock by 1636. Thenceforth they were a staple of the trade in North America. It is perhaps significant that during the religious and military revival sparked by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother, Tenkswatawa (the Prophet), in 1812 "the shores of Lake Superior were said to have been littered with blankets, mirrors, and other trade goods." All of this was done in response to the urgings of the revival leaders, who "urged the Ojibway to cleanse themselves of the evil ways of the white men and to turn their backs on tricksters who had used the sacred Midewiwin society to gain power."[51] In casting away the trade mirrors, the Ojibway were arguably ridding themselves of not only the symbols of their relationships with the Anglos but also the images of themselves in those relationships.

Less evidently, but just as surely, more functional trade items represented relationships between Native Americans and Euro-Americans. Thomas Schilz and Donald Worcester noted that although trade goods may have been coveted because they "made life easier," they also endowed their possessor with wakan (power): "Middlemen who could acquire powerful talisman like horses, guns, steel tools, and other products of the white men wielded not only economic but also spiritual power over their people."[52]

Elaborating upon the idea a bit more, they stated that the introduction of firearms into the Southwest dramatically altered the balance of power there, and introduced observations that call into question what might seem to be the obvious reason for this, that firearms were a dramatic improvement in the technology of warfare available to the Southwestern Indians. First of all, they observed that these Native American groups never adopted firearms as their primary weapon. They continued to rely upon the bow and arrow.[53] Although Schilz and Worcester did not discuss the reasons for this in any detail, it is generally known that a typical Plains Indian brave could, in a given amount of time, release more

arrows than, and as accurately as, an individual with a firearm could fire shots. This situation prevailed until about the third quarter of the nineteenth century, when firearm technology was improved. Before then, the Apache, for example, armed with bows and arrows, were considered by many Western military officers to be as least as good as their light cavalry. While firearms might have been relatively more effective than the bow and arrow in forested areas, in the wide open spaces of the western Plains and the Southwest, firearms held no advantage, at least in the early nineteenth century.

A number of historians have opined that until the Spanish were displaced from the Southwest in 1821, modern, good-quality, firearms were not readily available to Native Americans. The Spanish policy was to supply the Indians (especially the indios barbaros —the nomads) with outmoded weapons, preferably of inferior steel, which put the Indians at a technological disadvantage and made them more dependent upon the Spanish for replacements and repairs.

It is significant that even with the departure of the Spanish from the southwestern Plains and the entry of the Americans, who would trade virtually any item, Native Americans (along with trappers) evidently continued to use "outmoded weapons." The notion that large caliber, smoothbore, flintlocked firearms were preferred by these groups into the second half of the nineteenth century has been a generally accepted, if not rigorously formulated, notion among fur trade historians for some time. William J. Hunt's analysis of the firearm-related artifacts he recovered from archaeological excavations at Fort Union on the upper Missouri River lends substantial support to this.[54]

There were practical reasons for the predilection: flintlocks were less expensive ($7.00 even in 1861 versus $42.00 for a Henry rifle); flints were much less costly per shot than were percussion caps; if one were to run out of manufactured flints a substitute of sorts could be fashioned from a cryptocrystalline rock; and smoothbore flintlocks could be loaded with almost anything in a pinch, including stones.[55] All this indicates that the Spanish strategy was a dubious one. It also raises questions about the efficacy of such firearms on the southwestern Plains. Given their customary tactics in warfare and hunting, it is by no means certain that the Plains Indians would have been disadvantaged by their absence. The bow and arrow was even simpler to use than the musket, at least to the Native American. It was also a less complicated mechanism and so less likely to malfunction. It was easier to carry, and replacement parts were readily available and cost nothing. It is true that the shock of a musket ball could bring

a buffalo, or a man, down more quickly than could an arrow, especially at long ranges. But this advantage did not outbalance those associated with the bow and arrow, especially since traditional tactics were those that dealt with targets at close range.

At Bent's Old Fort, the weight of evidence suggests that more technically sophisticated firearms were not offered at the fort for purchase by the customers, of whom many if not most were Plains Indians. The absence of more sophisticated firearms is borne out by notes the historian F. W. Craigen compiled for a book never published. Craigen reported on an incident apparently relayed to him by a Milo H. Slater, in September of 1903. Slater remembered that during "the regular fall buffalo hunt at Bent's Fort" in 1838, a young man called Blue borrowed a rifle from the leader of the hunt, Ike Chamberlain of Taos, so that he could go along. Two weeks after the hunt began, the lock on the rifle broke and the young man had to return to Taos because only flintlock rifles could be had at the fort at the time that were "useless for buffalo hunting."[56]

Slater may have been overstating the case a bit, but it is enough to again call into question the utility of firearms to the Plains Indians. After all, by 1838 the trading association between the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes and the Bent & St. Vrain Company was well established. A vital part of this relationship was that the Bents would provide the tribes with the equipment they needed to procure buffalo robes for the fort. Not only are we being told by Slater that flintlock rifles were useless for buffalo hunting, but that Bent's Old Fort did not have anything but these in stock.

Archaeological material recovered from Bent & St. Vrain Company trash deposits includes nothing that might have been associated with firearms well suited for buffalo hunting. Although the account ledger from the fort indicates that 20,000 percussion caps were purchased by Bent & St. Vrain from the American Fur Company as early as 1840, no percussion caps were found in the portions of the two fort dumps used during the Bent & St. Vrain occupation. The percussion caps in the ledger may have been sold to travelers passing through the fort, sent on to New Mexico or elsewhere, or even used by hunters of European extraction who obtained buffalo (often for meat) at some distance from the fort. But had the caps been used by the Native Americans or trappers who frequented the fort, one might expect at least one to show up in the Bent & St. Vrain-period trash deposits. Also, all gunflints found in these deposits were very small. They could have been used only in pocket pistols or small caliber rifles like fowling pieces.[57] Such weapons would have

been of marginal utility in buffalo hunting, or for that matter any activity in which a Plains Indian might have been likely to engage at that time.[58]

In summary, the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other Plains tribes had questionable need of firearms for hunting or warfare. Their bows and arrows were as accurate and almost as deadly as firearms, well into the late nineteenth century. They were also more quickly readied to fire again. Finally, the bow and arrow was more dependable: according to the data that convinced Britain to change to a percussion system, about 1 shot in 6 from a flintlock would misfire, compared to 1 shot in 166 from a percussion cap weapon.[59]

The fact is, however, that firearms were desired by the Indians of the southwestern Plains. As Schilz and Worcester explained, "Nevertheless, all the Indians of the Spanish borderlands eagerly sought firearms for hunting and warfare because of the 'medicine' attributed to such weapons as well as their striking power."[60] Evident here is the symbolic significance of a trade item usually thought of strictly in functional terms.

Horses were another sort of trade good with strong symbolic significance, although the functional value of the horse to the Plains Indian is beyond dispute. It was the acquisition of the horse that allowed the transition from sedentary agriculture to nomadic hunting and warfare. While the horse was generally regarded among the Plains Indians as the most essential measure of wealth, it was also laden with great spiritual meaning; here, again, we see that the two forms of value were not strictly separated. Frank Gilbert Roe's The Indian and the Horse contains the statement that "the most profound influences exerted by the coming of the horse into Indian life were in the spiritual realm."[61] Roe noted the various ways in which the horse had become an integral part of the religious existence of the Plains Indian: Shamans utilized the ascribed supernatural powers of horses to influence the fate of the tribe. Young men had visions of the horses that were later to be their own. A warrior's horses were often killed to accompany him to the next world. Horse figures adorned clothing and tepees, imparting in this way their spiritual powers. Most significant, horses were among the most common subjects of poetry and legend.

Ethnologist John C. Ewers looked at three Blackfoot myths in The Horse in Blackfoot Indian Culture .[62] One of these myths was called by the Blackfoot informants "Thunder's Gift of Horses." In this, not only horses but also other key symbolic elements of Plains Indian material culture are presented. The story, tells of a wise but poor old man who is rewarded for his

kind treatment of Thunder's horses. The old man receives the knowledge of how clothing can be adorned with porcupine quills, the power to have visions that reveal appropriate tepee decoration, and two physical objects: smoking ("medicine") pipes and horses. Ewers concluded:

These myths constitute evidence that to the native mind the horse was a godsend of importance comparable to that of their most sacred ceremonies, created by the same supernatural powers who gave the Indians their chief ceremonial institutions.[63]

The symbolic value of another sort of item, ceramics, was explored by David Burley, in an article about the Metis of the northwestern Canadian Plains.[64] Ceramics were not, strictly speaking, a trade item; that is, they were not usually traded to nomadic Plains Indian groups. Although these tribes had made and used ceramics as sedentary agriculturalists, this aspect of their material culture had been lost as they took up a new way of life as horse-borne hunters and warriors. Quite simply, ceramics (especially very fragile ceramics such as these) had no place in a lifestyle that involved frequent relocation. Nonetheless, the Metis reestablished the use of ceramics, which they incorporated into their nomadic existence. In transient campgrounds, for example, delicate teawares and expensive transfer-printed wares have been recovered archaeologically.

Burley asked why a frequently mobile, semisedentary, hunting and gathering people would maintain such a nonfunctional form of material culture in the face of more durable alternatives. The Canadian Metis were the progeny of Native American women and the European or Euro-American traders who had occupied the area. They lived a life much more closely aligned to that of the Plains Indians than of the European traders, but they remained attached to these traders in two important ways. First of all, they frequently acted as provisioners, as voyagers, or in other capacities for traders. Also, because European and Euro-American women were completely absent from the area until 1830, the women of the Metis were considered to be the most likely marriage partners for the traders. This was particularly true for clerks and officers, for whom, by 1820, Native American wives were no longer considered appropriate.[65] Metis women who displayed the greatest numbers of "civilized behaviors" were obviously the most appropriate marriage partners. Over time, there developed a considerable group of Metis women in the upper echelons of fur wade society. Daughters of these women were further trained in the accomplishments of ladies, including the use of ceramics.

Burley argued that the use of these delicate ceramics spread to "even

the most 'poor' and mobile of the hunting brigades" by a process which operates according to what Burley, borrowing from Douglas and Isherwood, called the "infectious disease" or "epidemiological" model.[66] He said that the Metis were known for their hospitality and joie de vivre and spent a great deal of time visiting one another, drinking tea, smoking, and gossiping. These visits cut across class boundaries. Burley stated that "as ceramic use spreads from one group to another, social meaning is transferred from visual displays of status to a shared form of material culture."[67] What Burley is saying here, I think, is that the visits were imbued with symbolic significance by means of ritual of the fugitive sort. Burley made it clear that he believed he was following Douglas and Isherwood's thesis:

Instead of supposing that goods are primarily needed for subsistence plus competitive display, let us assume that they are needed for making visible and stable the categories of culture. It is standard ethnographic practice to assume that all material possessions carry social meanings and to concentrate a main part of cultural analysis upon their use as communicators.[68]

Although Burley offered no mechanism for the transmission of social meaning other than his metaphor of contagion, I suggest that the mechanism of transmission is that of ritual. Ritual most certainly produces shared social meanings by means of "sentiment." As Burley observed, "For Metis women, it is important to emphasize that it is not just the acquisition of ceramics that would be important. Rather, it involves the display and use of ceramics with appropriate social protocols."[69] I argue that this is ritual, one that refers to and reenacts the relationships of the European "ancestors." The tobacco-smoking, tea-drinking, and gossiping of the general Metis population are likewise ritual, in this case of a somewhat "degraded" or even "fugitive" sort, since it is less prescribed. It is ritual that resolves a crisis of identity by incorporating the behaviors of ancestors, which are very similar, from two different traditions. The affective response shared by the participants renders the material culture employed important to the participants, in a symbolic sense. It becomes a symbol of their renewed social relationship and, therefore, of slightly altered but essentially stable identities.

Having examined the symbolic value of a variety of trade goods—those that play an essential and obvious role in ritual (tobacco and associated paraphernalia, alcohol), those that at first consideration seem functional (firearms and horses), and those that are functional but which possess a symbolic value more in tune with modern notions of symbol (shells, bracelets, necklaces, mirrors)—we are now better able to appreciate the

significance of the quintessential sort of trade good: beads. Columbus, in fact, on his first voyage to the New World, reported exchanging some small green beads for supplies. Beads were a staple of European-Native American trade from that time forward.

The popularity of beads among Native American groups can be explained, in part, because they could be used in a variety of familiar ways. Beads strung or otherwise used as personal adornment have been dated to the Archaic period (6,000 to 1,000 B.C. ) in the Great Lakes region.[70] Early colonial entrepreneurs produced "counterfeit wampum" beads, which were similar to true wampum, the prehistoric white and dark purple beads made from shells by the native populations of New England.[71] The varied uses of wampum included: as symbols of treaties and agreements, as accompaniment to formal contracts, as tokens of condolence, as message devices, and as mnemonic devices.[72] As to this last use, the Iroquois, for example, had a Keeper of Wampum who was charged with remembering the significance of each string of wampum in his care. Many contemporary. Native Americans claim that because of this, wampum is a sort of historic document, although no one living is sure of how to read the existing strings. At the same time, certain Native American groups have requested the return of wampum from museums and other repositories, saying that wampum belts are sacred objects. From a traditional standpoint, of course, since meaning was assigned by ritual having some mythological referent, such objects are regarded as sacred no matter what the more profane meaning or use attached to them.

Trade beads among Plains Indians replaced the use of Porcupine quills for embellishing clothing, although, "when beads first arrived, the most respected Quillworkers refused to use them."[73] Eventually beads were used to reproduce the simple geometric designs favored by the Plains groups. Even so, Powell reported a tradition of reluctance to use anything manufactured by the white man on the most sacred paraphernalia.[74]

Blue trade beads were much in demand by Cheyenne and Arapaho, who felt that the white man had "stolen the blue from the sky." At Bent's Old Fort, the relative frequency of the discovery of blue beads was much higher in areas that were dated to the later period of the fort's occupancy than in those from the earlier period. The greater number of blue beads in the later deposits may evidence a case of supply catching up with the demands of a particular group of consumers.

In considering beads we have come full circle, back to the initial discussion of the prehistoric exchange of shells and columellae. These items cannot be explained solely in terms of how they functioned as instruments

by which to amass wealth. This approach is steeped in modernity; it assumes that value is ultimately set by an impersonal marketplace and ignores alternate meanings for material culture. But this is not to say that these meanings do not exist and exert a force. Trade goods could be imbued with meaning through their ritual association with cultural mythos, affecting social behavior in ways that cannot be explained by reference to market value or function. Examples presented here include the use of firearms by the nomads of the Southwest and western Plains when the bow and arrow functioned more efficiently in these locations, the spread of fragile ceramics to nomads in northwestern Canada, the killing of valuable horses to be buried with warriors, and even what seems to be, from a modern viewpoint, the "self-destructive" and compulsive use of alcohol and tobacco by Native Americans. All of these phenomena defy, analysis from a stubbornly "modern" perspective that emphasizes function, technology, and economic modeling. This is somewhat curious, since these or similar phenomena are decidedly a part of present-day society.