Fourteen—

Feminist Makeovers:

The Celluloid Surgery of Valie Export and Su Friedrich

Chris Holmlund

What constitutes a remake? How far, and in what ways, can the boundaries of "remake" be stretched, "made over," before a new "original" emerges? What, in particular, can be made of experimental film's fondness for recycling fragments of sounds, images, and story lines from earlier movies of all kinds? In this age of mechanical reproduction and celluloid surgery, are there any essential elements that allow us definitively to distinguish a remake from an original? Or are there just spare parts?

Marjorie Garber's discussions of the ways transsexuals, transvestites, and makeup or makeover artists trouble gender categories seem analogous. She finds the case of Renée Richards, born Dick Raskind, particularly instructive, though she is also intrigued by the transformations of cultural icons like Michael Jackson. With Renée, "it is the cutting off, by surgery, of the name and identity of 'Dick'—in effect the quintessential penectomy, the amputation of male subjectivity—that enables the rebirth of Renée" (Garber, 1992, 104). Yet for all the hormone injections, electrolysis, implants, amputations, and more, surely somewhere within Renée "Dick" lives on.[1] And even though everyone agrees that, despite plastic surgery, powder, and makeup, Michael is still Michael, he looks more and more like Diana Ross and more and more white.[2] Indeed, the controversy around Michael's hit single "Black or White" was generated as much by the man as by his message: "I'm not going to spend my life just being a color."

Such controversy is not surprising: artificial alternations of gender, sexuality, and race like those practiced by Renée Richard and suspected of Michael Jackson are hotly debated. Horrified if titillated talk-show audiences protest such changes are both against nature and anti-social; cultural critics gleefully proclaim surgical modifications cut away at and/or reshape privileges predicated on visible—and not so visible—differences. To

my knowledge, however, as yet no one has combined these arguments with questions about the status of experimental makeovers vis-à-vis Hollywood or experimental film originals.

In order to examine celluloid surgery together with plastic surgery, therefore, I want to compare two experimental films by Valie Export and Su Friedrich with the two mainstream originals they make over. What each borrows, and how and why it borrows it, varies, but both manage to blur the boundaries separating film from literature, painting, sculpture, and video by chopping up earlier cinematic sources, then stitching them together with yet other material. In the process, I will argue, each creates films that jeopardize "natural" or "essential" definitions of gender, sexual preference, or race.

Valie Export works within and against a range of philosophical, literary, and artistic traditions. Since the 1960s she has explored several different media and written a number of critical articles and books about her own and others' work. The director of several short and three feature films,[3] Export is best known in Austria and elsewhere as a feminist performance artist practicing what she calls "action art." No matter what medium she uses, however, she is always concerned with the impact of gender on art and art on gender. Her first feature, Invisible Adversaries (Unsichtbare Gegner , 1976), has been called a feminist Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Siegel, 1956, and Kaufman, 1978).[4] But Export's film contains more than one makeover: there are several references to Buñuel and Dali's 1929 An Andalusian Dog (Un Chien Andalou ),[5] to famous paintings, and to Export's own previous performance pieces. As a result, Invisible Adversaries is visually rich, entertaining, striking, but also demanding.

Su Friedrich's experimental narrative films are more accessible, though equally transgressive. Primarily a filmmaker, with a long list of shorts and several full-length films to her name,[6] Friedrich has a history of involvement with the New York experimental and feminist art worlds. She describes herself as a lesbian-feminist-experimental filmmaker who reaches various audiences by what she calls "ghetto hopping."[7] But though Friedrich speaks from and for several at times overlapping, at times disparate, positions, her work has consistently been concerned with contesting heterosexual assumptions and broadening what is seen and desired as "lesbian."[8] Nowhere is this truer than in the 1987 Damned If You Don't , with its reframing of Powell and Pressburger's 1946 acclaimed melodrama, Black Narcissus , and lesbian feminist written and oral histories.

From different angles, then, both these experimental makeovers snip away at sources and clip up centers, demonstrating in the process that "new definitions of identity, the subject, gender [and I would add sexual and racial] roles and reality . . . are a possible consequence of the age of electronic signs" (Export, 1992, 27). I will explore in conclusion just what these

new definitions of identity, roles, and reality may be and ask one last time whether there are any essential elements, or just spare parts, in cinema or society.

Of Clones and Men:

Invasion of The Body Snatchers and Invisible Adversaries

Thanks to technology, which transforms and dissolves the body itself, "man has, as it were, become a kind of prosthetic God," says Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents. But, asks Valie Export in "The Real and Its Double: The Body,"[9] does Freud mean man in the generic or the specific sense, or both? What of woman?

Invisible Adversaries offers partial, and contradictory, answers to these questions as it rewrites and transforms Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers through cinematic injections, implants, alterations, and amputations. Both films share the same narrative premise: aliens from outer space have invaded and are replacing human beings. They are so successful that real people are almost indistinguishable from clones, called "pods" in Invasion of the Body Snatchers and "hyksos" in Invisible Adversaries. Both movies weave love stories together with this basic invasion plot. Both indict authority figures like psychiatrists and policemen for collaborating with and even becoming the enemy, and both suggest mass communication networks distort as much as they report. A strong fear of totalitarianism thus subtends both narratives, though what constitutes totalitarianism differs. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is typically discussed with reference to communism, McCarthyism and/or fascism,[10] whereas Invisible Adversaries targets the Austrian right and center left, naming the neo-Nazis and the SPO (Austrian Socialist Party) while, more broadly, linking Western governments to imperialist wars.[11]

Nevertheless, unlike the 1979 Hollywood version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Invisible Adversaries cannot really be called a remake. In her descriptions of her film, Export never mentions Siegel's movie, though neither does she comment on the plethora of other visual and written citations she cuts into and adds onto the "main" hyksos story.[12] Critics, too, often overlook the similarities between Invisible Adversaries and Invasion of the Body Snatchers ,[13] in part because Invasion of the Body Snatchers is carefully structured,[14] whereas, as Marita Sturken says, the "'hyksos' plot . . . gets rapidly lost in the experimental vignettes" (Sturken, 1981, 18). Export alters her protagonist's gender and occupation from male small town doctor to female big city photojournalist. The relative importance accorded psychoanalysis and the mass media shifts in consequence, and the meanings assigned to voyeurism and paranoia within the film's visual and audial structures, vary as a result as well.

The misogynist gender politics of Invasion of the Body Snatchers , like its antitotalitarian stance, remain for the most part below the surface. Yet for Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) the ultimate moment of terror is linked to the absence of female passion: hiding from the pods in a cave with his fiancée (Dana Wynter), he kisses her and she does not respond. From the time and space of the film's frame story, set in a mental institution, he confesses in voice-over, "I'd been afraid a lot of times in my life, but I'd never known the real meaning of fear until I kissed Becky. A moment's sleep and the girl I loved was an inhuman enemy bent on my destruction."[15]

Invisible Adversaries , in contrast, begins by highlighting the importance of gender and leftist politics to its narrative, while expressly calling attention to the roles played by mass media and art in modern society in general and 1970s Vienna in particular.[16] In the first sequence, a male broadcaster warns through static of an invasion by alien hyksos: "Anyone can be a hyksos and not know it. You are contagious. You are alone." The other news items he reports are factual, yet they too revolve around violence, aggression, and contagion. The camera zooms in to a close-up of a newspaper headline with the film's title, then pans the body of a sleeping woman, and finally moves out her apartment window to scan the rooftops of Vienna. At one point, another male voice interrupts the first to quote action artist Georges Mathieu. The voice thereby provides an explanation for the hyksos's presence (radiation) while describing their mission (the destruction of the earth).[17]

It is as if Export had amputated the first two-thirds of Siegel's narrative. She begins with the last third of his film, with much of the world already under hyksos control. She also performs a kind of cinematic sex change on Invasion of the Body Snatchers , rewriting it from Becky's point of view at the very moment when she is about to mutate. The film style is correspondingly chaotic, with jump cuts, 360-degree pans and elaborate montage sequences suggesting disturbance and alienation, perhaps even translating the trauma of the cinematic alterations. Siegel's film, in contrast, is characterized by straightforward point-of-view shots and subtle cinematographic hints of abnormality.[18]

What are the implications for gendered subjectivity when faced with the cutting room floor?[19] Repeatedly Export asks whether it is possible that women in general, and the protagonist Anna (Susanne Widl) in particular, have always been hyksos, never humans? The second sequence certainly suggests as much, showing Anna framed in a doorway, then framed and reflected in a mirror. Her reflection takes on a life of its own, applying lipstick as she watches. Fascinated and horrified by what she has seen in the mirror and heard on the radio, Anna sets out to observe and document her own, her lover Peter's (Peter Weibel), and others' transformations into aliens.

Since Anna is a photographer and video artist, her voyeurism is, quite literally, mediated. Newspapers, photography, video, film, tape recorders, and radio serve as her allies and tools, not—or not primarily, as in Invasion of the Body Snatchers —as her enemies. Miles's voyeurism is, in contrast, direct. He relies on the naked eye, peering into or from windows at his nurse as she prepares to turn a crying baby into a peaceful pod, or down on the triangular town "square" where the aliens have assembled to carry out the takeover of surrounding communities.

With her media helpers Anna finds, and fashions, doubles everywhere. In a videotape entitled "Silent Language," she examines women's body language in art and daily life, documenting a lack of change from Renaissance paintings to the present: Michelangelo's Pietà , for instance, dissolves into a woman holding a vacuum cleaner. Later she runs around cardboard cutouts of people she has placed beside a fountain in a plaza, then, back home, outlines her silhouetted reflection in pins on a wall. A larger-than-life-size photo of herself, hair slicked back rather than down, decorates her refrigerator; inside is a kind of future "double," a baby.

For all Anna's and Invisible Adversaries ' emphasis on female doubles, however, the central question Anna asks in one of her tapes, "When is a human being a woman?" is never clearly answered, either in her own videos or photographs or in the film itself.[20] Caught in a web of representations, woman is always a body determined by others: "the natural body of the woman doesn't exist" (Export, 1988, 7). Yet woman is not just a body. As Export says in "The Real and Its Double," woman "views her own body from outside as alien. . . . The ontological experiencing of the body by woman is the simultaneous experiencing of the personal and the alien" (1988, 12–13). Woman is both split and doubled, simultaneously subject and object, eye and "I."

Throughout the film the schizophrenia of Anna's positioning as both hyksos and Anna, alien object and alienated subject, is made visible on and through the body. Overcome by angst after talking to Peter about the spread of the hyksos, she slides down the glass walls of a phone booth. In the street she rearranges herself to fit her environment, wrapping herself around a curb, or cramming herself into corners. At home she suddenly starts to shake. A bit later she unpacks her groceries and starts to cook, only to have a rat run across the table, then a live bird and fish appear. In a rapid and highly surreal montage sequence she decapitates these animals one after another, then goes to the bathroom to photograph feces floating in the toilet, develops the pictures, and finally goes to bed.

Many of these sequences recreate Export's performance pieces from 1972–76, described as "the pictorial representations of mental states, with the sensations of the body when it loses its identity" (Hofmann and Hollein, 1980, 13). An early dream sequence, for example, implants one of her 1972

explorations of the physical and emotional effects of bodily constraints into the "main" hyksos narrative.[21] A screen with black-and-white images of Anna wearing ice skates and walking through Vienna appears over color images of her sleeping. In the black-and-white film the scene changes with each step, echoing the nonsensical temporal and spatial editing of An Andalusian Dog , as also Maya Deren's Meshes of the Afternoon. At the end of Invisible Adversaries Anna enacts another piece from this same set of experiments, going to bed in a mountaineering outfit, woolen hat, gloves, and boots as the radio recounts still more tales of violence and horror.

By stitching this particular performance piece into the main film body, Export makes it clear that the paranoia, angst, and isolation Anna experienced at the beginning of the film have worsened: no trace remains here of the final guarded optimism of Invasion of the Body Snatchers where the psychiatrists finally believe Miles and call the FBI in to help. Instead invisible adversaries are everywhere, and they are both internal and external. Peter, Anna's leftist lover, grows increasingly hostile. "Women are parasites," he tells her at one point, to which she has a woman in her videotape respond, "Men are dwarves." The playfully perverse heterosexual sex we see so much of at the beginning of the film comes to seem threatening, especially since other couples around Peter and Anna quarrel and fight as well. Peter himself maintains love is worthless, impossible: "This disgusting longing for love is an emotional plague," he tells Anna; "love is a transparent prison." What he says echoes what the pod psychiatrist tells Miles in Invasion of the Body Snatchers: "Love, desire, ambition, faith—without them life is so simple. . . . There's no need for love. Love doesn't last."

In contrast to the relatively major part accorded Invasion 's psychiatrist, Anna's psychoanalyst plays a relatively minor role and appears only near the end of the film. He first suggests she have her eyes checked, then diagnoses her as schizophrenic and prescribes pills. The pictures Anna takes of him reveal he is a hyksos but, unlike Miles, Anna does not particularly care. The men and boys she encounters masturbating and fighting in the streets pose more serious threats to her psychic and physical well-being. These images are often intercut with newspaper, film, and TV images of rocket launchers, burning trucks, and napalmed children, effectively linking violence in the third world to violence in the first, and distancing Export's makeover still further from Siegel's original.

Near the end of Invisible Adversaries , Anna goes to see a war movie. "Help in the search!" ("Suchen Sie mit!"), urges the male narrator over the black-and-white and color images of destruction. Anna looks anxiously at herself and the audience in a pocket mirror. Siegel's film was to have ended similarly, with a close-up on Miles's frightened gaze as he tries to convince motorists on the L.A. freeway "You're next!" Whether or not Export is intentionally parodying Invasion of the Body Snatchers , her injection of yet another

film within her main film speaks not just to Anna, but also and more broadly to the spectator of Invisible Adversaries . Export's, Anna's, and other women's reflections on the position and positionings of women open outward, to include us as well.[22] "My visual art is for me a monologue . . . a dialogue with an invisible partner," says Anna in her videotape "When Is a Human Being a Woman?" Unlike Invasion, which encourages our identification by playing on our desire to see, or, better yet, by fueling "our urge to gain access to the meeting ground between the specular and the blind" (Telotte, 1990, 152), Invisible Adversaries proposes "an 'aesthetic of reception' . . . [wherein] [t]he signifying practices of cinema are deployed as an element of a de/re/construction not only of genre film, but also of its spectators. . . . [T]he film makes sense (narratively, technologically) only in feminist terms" (Cranny-Francis, 1990, 225).[23]

For all the implants and injections, amputations and alterations that characterize Export's self-reflexive celluloid surgery, however, her film doubles do not guarantee a way out of the double bind in which women find themselves in patriarchal cultures. Nevertheless these "stagings of the body" do make more obvious the extent to which woman is defined as body "by an alien ideology" (Export, 1992, 33). As Export says of feminist action art in general, "[O]nly knowledge prevents contagion" (1989, 73).

In her writing, Export recognizes that tapping the tendency of technology "to transform and dissolve the body itself" is risky: (1988, 2) in a world where woman equals body, "deconstructing the body can lead to extinction." Yet, she continues, "since . . . the increased prosthesis-like quality arises from the progress of civilization, we cannot refuse disembodiment" (1988, 17–18). In Invisible Adversaries she even has Anna devise her own prosthesis, cutting her pubic hair and using it as the basis of a temporary sex change wherein she makes herself over into a mustachioed man. For a moment, the artificiality of gender is very much apparent, as it is in An Andalusian Dog where, through the miracles of editing, a woman's armpit hair is transformed into a man's beard.

At times Anna's de- and reconstructions of femininity provide the basis for solidarity among women. At times they unsettle masculinity as well. But Anna's, and Export's, critiques of gender remain tenuous, hampered and hobbled, for, as Export says, "the battle of the sexes has always already been won by men" (1989, 72). Inevitably so, I would argue, since Export never broaches the question of homosexuality in Invisible Adversaries, even though heterosexuality is obviously in crisis.[24] As long as heterosexuality remains an uncopiable original, in trouble yet intact, what Marjorie Garber terms "the twin anxieties of technology and gender" (1992, 108) remain in place, and the dualistic or binary frame that positions women as irremediably inferior and inalterably Other survives and proliferates as well. Export's implants and additions may make us forget the amputations and subtractions

she performs on Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and may thereby jeopardize the notions of cinematic or artistic original, but they stop short of demonstrating once and for all the constructedness of gender.

Much Ado about Nun-Things:

Black Narcissus and Damned If You Don't

By shifting the central organizing perspective of her science fiction film from male to female, Valie Export begins to "rewrite gender within genre" (White, 1987, 84). But, as Judith Butler argues, sex, gender and desire are not necessarily synonymous: "Gender can denote a unity of experience, of sex, gender and desire, only when sex can be understood in some sense to necessitate gender—where gender is a psychic and/or cultural designation of the self—and desre—where desire is heterosexual and therefore differentiates itself through an oppositional relation to that other gender it desires. . . . This conception of gender presupposes not only a causal relation among sex, gender, and desire, but suggests as well that gender reflects or expresses desire" (1990, 22).

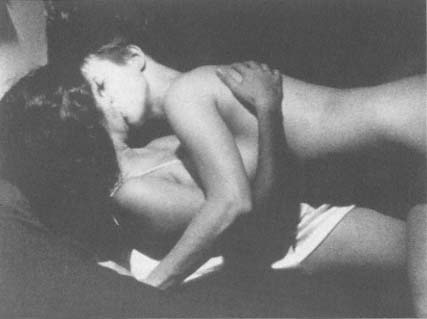

As "the narrative form that takes desire as its subject" (Lang, 1989, 12), melodrama offers a more logical site than science fiction for cinematic investigations of the connections and disjunctures among sex, gender, and desire. Damned If You Don't, Su Friedrich's makeover (and more) of Black Narcissus, successfully adopts this strategy, highlighting how much Black Narcissus and melodrama in general are predicated on the assumption that all desire is heterosexual. Snipping up, then reconstructing Powell and Pressburger's original tragedy of unrequited (white) heterosexual love, madness, and death, Friedrich instead proposes a narrative with a happy ending for lesbians: for once the (Latina) girl, not the boy, gets the (white) girl, and no one dies or goes insane.[25] By the end of Damned If You Don't, lesbianism is no longer a sickly copy of a healthy heterosexual original. (See figure 26.)

The same spirit pervades both Black Narcissus and Damned If You Don't . Both make nuns the central characters of stories where, as Friedrich pointedly puts it, "the chaste are chased" (Hanlon, 1982–83, 81). Both are highly sensual, though, as Michael Powell says of Black Narcissus, "it is all done by suggestion" (1987, 584). Unlike Export, moreover, Friedrich is quite willing to acknowledge her debts to and appreciation of Black Narcissus, even as she manipulates and criticizes several of its basic premises. Like Export, she includes a variety of other material in her film, thereby altering the shape of the original.

But where Export's celluloid surgery of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is ongoing and multiple, Damned If You Don't' s relationship to Black Narcissus is like a single large implant: for the most part the Black Narcissus makeover is confined to the first eight minutes of Damned If You Don't, although a few

Figure 26.

Lovers embrace in Su Friedrich's Damned If You Don't (1987), a transgressive

retake on Powell and Pressburger's 1946 melodrama, Black Narcissus .

Black Narcissus images reappear briefly at the end as well. Even within this implant, however, Friedrich sets other more minor alterations in motion, then further amplifies and modifies these alterations in the rest of the film. Cinematically, within the Black Narcissus sequence and indeed elsewhere as well, Damned If You Don't is more restrained than Black Narcissus, though no less compelling. Narratively, the two films differ in three key and overlapping areas: 1) how they portray the two lead female characters; 2) whether and how they represent male characters; and 3) how they inscribe racial and ethnic difference.

Rather than contrast virility and femininity, repression and expression, West and East as Powell and Pressburger do, Friedrich takes a different tack. For the most part Damned If You Don't excises Black Narcissus' imperialist fantasies. Gone are the lush but artificial settings created in British studios through matte shots, glass shots, and painted backdrops or, as in the case of the subtropical gardens filled with "cedars, deodars, rhododendrons and azaleas," literally transported from India to England by retired "merchant princes and pro-consuls" (Powell, 1987, 562).[26] Gone too is the incessant drumming of the natives, and gone is almost all reference to any "Indian"

characters. Except for one brief shot of Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) and Kanchi (Jean Simmons), the "sexy little piece who attracts the eye of the young Prince" (Sabu) (Powell, 1987, 576),[27] the Malays, Indians, Gurkhas, Nepalese, Hindus, and Pakistanis Powell and Pressburger indiscriminately cast as Indians have been cut from Friedrich's film.[28] In the stripped-down, stitched-up version of Black Narcissus she offers, the principal characters are known only as the Good Nun (Deborah Kerr), the Bad Nun (Kathleen Byron), and Mr. Dean (David Farrar).

The offscreen female narrator of the Black Narcissus sequence (Martina Siebert) only mentions the Orient twice, in passing. Each time she mocks the racism signaled so blithely in the very title of Powell and Pressburger's film: "Black Narcissus" is the name of the cheap perfume the young prince wears.[29] In Black Narcissus the young prince proudly tells the nuns his perfume comes from the Army Navy Stores of London. "I'll call him Black Narcissus," Sister Ruth, the Bad Nun, says when he leaves. "He's so vain, like a peacock. A fine black peacock." "He's not black," another nun replies. "They all look alike to me," Sister Ruth retorts.

In Damned If You Don't, in contrast, Siebert's offbeat voice-over—which includes, for example, such lines as "[the nuns] forgive [Mr. Dean] for arriving naked, given the state of emergency"—makes the melodrama she recounts seem more like a comedy. Rather than talk of the need to "humanize" the natives, as Mr. Dean and the nuns do, Siebert says flippantly that the nuns "work hard, day and night, bringing aspirin and the English language to Indian peasants." The flatness of her delivery detracts from any exoticism that might attach to her German accent. She also directly links racism to sexism: "[The Good Nun] asks [Mr. Dean] why the local people can't be more disciplined, which somehow raises the question of whether or not she likes children." The Black Narcissus sequence she refers to is more overtly racist, but it disguises sexism as flirtation: wearing shorts, a shirt, and a hat, Mr. Dean crosses and uncrosses his hairy legs and glances "meaningfully" at Sister Clodagh, all the while insisting that the "natives" are "primitive people . . . like children, primitive children."

At only one moment does Friedrich incorporate text from Black Narcissus . The Good Nun says, "If you have a spark of decency left in you, you won't come near us again." Then Friedrich interrupts Siebert's narration to sing Mr. Dean's song herself: "No I won't be a nun, no I shall not be a nun, for I am so fond of pleasure, I cannot be a nun." The pastiche is doubly gender bending: first, because a man sings a song "only" a woman should sing since "only" women can be nuns;[30] second, because a woman, Friedrich, sings a song "originally" sung by a man. Only at the end of the segment do we hear Mr. Dean himself sing the song. Now, however, he does so over medium two-shots of the Good and the Bad Nuns. (See figure 27.)

Figure 27.

The nun in Su Friedrich's experimental makeover, Damned If

You Don't (1987), raises questions of identity and gender.

Friedrich performs other more minor surgical operations on her eight-minute Black Narcissus segment as well. Roll bars flicker across the screen since she has taken the images from a television broadcast without standardizing them to film. Periodic cutaways show a woman who will become one of the main characters of Friedrich's primary narrative (Ela Troyano) pouring herself a glass of wine, then settling in to watch Powell and Pressburger's film on TV, and finally falling asleep.

Friedrich's reshaping of the Black Narcissus implant leaves no doubt about what the lesbian character of her main narrative finds to like in Powell and Pressburger's melodrama. She abbreviates and reframes several shots in order to insist on the exchanges of looks between the Good Nun and the Bad Nun. As a result, the force of their desire and rivalry for Mr. Dean imperceptibly acquires another, lesbian, layer.[31] As Martha Gever says, Friedrich "tells . . . the story of passionate relationships between women within the film's male-centered narrative—by concentrating on the key moments in the rivalry between two female characters" (1988, 16). With the amputation of Kanchi and the young general from the Black Narcissus segment, happy heterosexual love disappears entirely from Damned If You Don't,

leaving only what Friedrich calls "the sexual hysteria at the core of the film" (MacDonald, 1992, 304).

In the final analysis, however, Friedrich's makeover is more a reverent restatement than an outright rejection, as much the enhancement of secondary celluloid characteristics as the castration of primary ones. Friedrich says she appreciates, for example, "the really high drama of Black Narcissus . . . . Powell and Pressburger used lighting to such great effect and created a lot of expression in the faces, which is all you have to work with when you're dealing with characters who are completely covered" (MacDonald, 1992, 304). Damned If You Don't translates this drama into its own terms, using black and white instead of color. For the most part, Friedrich's reconstruction of Black Narcissus refuses the canted angles, extreme long shots, dramatic framing, superimpositions, dissolves, and flashbacks of the original. Instead Friedrich insists on meter and tempo, editing "the rhythm of gestures within the shot . . . with the rhythm of the roll bars, [and] . . . the cadence of the speech at the moment" (MacDonald, 1992, 304–5).

Friedrich admits that "what I felt I was doing by beginning with the Black Narcissus material was saying, "Okay, you want a narrative, here, take it: you can have it. And you can have it just for its high points, you don't have to slog through all the bullshit, all the transitions" (MacDonald, 1992, 306). Yet Black Narcissus functions not only as hook but also as model for the rest of Damned If You Don't, in that Friedrich's film remains a dramatic narrative, though Friedrich adds "god forbid, a happy ending" (Friedrich, 1989–90, 123).

In many ways, therefore, Friedrich's implant of Black Narcissus becomes the basis for the new celluloid body that is Damned If You Don't . The woman (known only as the Other Woman) who watched Powell and Pressburger's film at the beginning of Damned If You Don't adapts elements from the former to fit her own devious designs. At one point she even buys a needle-point head of Christ as a gift for the next door neighbor, the Nun (Peggy Healey), whom she desires. Friedrich carries on Powell and Pressburger's emphases on framing and costuming as well, insisting as they do on the sensuality of spirituality. On an outing to the New York City Aquarium, for example, the Nun watches white whales swim within their tank. Her black robe and white face visually echo their white bodies on the black water. Later images of her in her tiny room or behind grillwork make it clear that she too is a prisoner. The Other Woman's restless movements, dark good looks and flamboyant clothes (black bolero pants, tight tops, a low-cut and diaphanous black party dress), offer a conspicuous contrast to the Nun and combine eroticism and exoticism just as Sister Ruth and especially Kanchi did in Black Narcissus .

Except for the offscreen voice of a priest, there are no male characters at all in the main story of Damned If You Don't . All the watching, all the

desiring that occurs in the constant shot/reverse shots, point-of-view shots and eyeline matches takes place between women. Finally the Nun gives in to desire and decides to love her neighbor as herself. The Other Woman slowly unveils her, and the two make love in silence—a major shift from Black Narcissus' operatic climax, where "music, emotions, images and voices are blended together into a new and splendid whole" (Powell, 1987, 583) as, mad with jealousy and grief because Mr. Dean has rejected her, Sister Ruth tries to kill Sister Clodagh by pushing her off a cliff. Instead she slips and falls to her death. The final credits of Friedrich's film unfold, appropriately enough, to the lascivious lyrics and raucous tune of Patti Smith's "Break It Up."

Two other subnarratives, both of which reinforce the main story's emphasis on the virtues of lesbian love, are grafted onto the sound track of Damned If You Don't . The first set of grafts is excerpted from Judith Brown's Immodest Acts , a study of a nun found guilty of "misconduct" in Renaissance Italy and imprisoned for thirty-five years in prison within her convent.[32] Friedrich also interrupts the first of the two selections she includes. An offscreen narrator (Cathy Quinlan) reads Sister Crivelli's testimony that, as she watched, Jesus removed Sister Benedetta's heart and replaced it with his own. Quinlan chuckles as she says, "How can I live without a heart now?" "Well, why not?" Friedrich's voice responds. Stepping completely out of character, Quinlan says, "You know what? I just had the funny idea that Sister Crivelli said this millions of times too. At a certain point she was just reading the fucking testimony." The second selection, which describes a series of lesbian sex acts in graphic detail, is uninterrupted.

By grafting sections from Immodest Acts onto and into her main story, Friedrich implicitly reclaims past lesbians for the present. Periodically, if more parenthetically, a second set of grafts tells of other lesbian love stories. At one point an anonymous voice on the sound track asserts that the nuns she had crushes on as a child were lesbians. Onscreen we see still other nuns framed in two-shots or three-shots. By association they too become lesbians, or at least potential lesbians.

Each and every element of Friedrich's film, including her implant of Black Narcissus , thus hints at the persistence of lesbian desire through time and across cultures, despite silencing and persecution. By the end of Damned If You Don't , heterosexual melodrama has, in effect, been "lesbianized." The moral of Friedrich's film is quite unequivocal: here you're only "damned if you don't."

But while the moral of Damned If You Don't is unequivocal, its address and its referents are not. Who is the "you" in the title? Who will be "damned if they don't?"[33] Only women? Only lesbians? Only white and Latina lesbians? Friedrich's decision to focus on the role played by sexuality in melodrama, like Export's decision to focus on the impact of gender on science

fiction, pushes questions of racial and ethnic difference to the background. Even though each acknowledges in passing that such differences exist—Friedrich through her ironic commentary about Black Narcissus and casting of Troyano and Healey; Export through the offscreen news stories and the documentary images of destruction and disaster in third world countries—"white" remains the dominant, and hence the invisible, color in both films.

In Stitches:

Cutting up As Serious Business

Both Export and Friedrich question profoundly what might constitute copy or serve as source. Though neither operates primarily on racial or ethnic differences, the celluloid surgeries both perform demonstrate the extent to which "the original, like the author and the real are themselves constituted as effects" (Butler, 1991, 146). Each stretches and pads, clips up, and cuts together more than one original. As a result, their fantasies, like Foucault's phantasms and, much earlier, Plato's "bad copies," "brea[k] down all adequation between copy and model, appearance and essence, event and Idea" (Young, 1991, 82).

Are there, then, any essential elements that might allow us to distinguish copy from original, makeover from model? Or are there just spare parts?

Of course more than textual politics is at stake in and around these films, for their indeterminate status as remakes or originals is matched by their offhand insistence on the ineffability of subjectivity. Since identity is predicated on difference, each film to some extent places identity in jeopardy because each, though differently, makes it difficult to see difference, and therefore difficult to tell the difference: in Export's case, between men, women, and hyksos; in Friedrich's case between nuns and lesbians. This does not mean, however, as Barbara Christian argues in another context about such postmodern politics, "that reality does not exist, that everything is relative, that every text is silent about something—which indeed it must necessarily be" (1990, 43). The point must also be made, I think, that since each film overlooks or downplays some differences, each leaves some identities untouched and intact. It is imperative we acknowledge, for example, that both these films leave race largely unexamined. We could, indeed we should, imagine makeovers of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Black Narcissus , or any one of a number of other Hollywood or experimental films, which would foreground and fragment the "security" of identities predicated on racial, ethnic, or national origins as well, much as Michael Jackson's multiple makeovers confuse neat categorizations not just of gender and sexuality but also of race and age.[34]

The extent to which identities are interlocking, not additive, and not

unitary, only emerges when the various celluloid surgeries these experimental filmmakers employ are evaluated each against the other, and both against still other films made from yet other political perspectives. Collective participation and cross-pollination are crucial. Abdul JanMohamed and David Lloyd put it well: "Just as it is vitally important to avoid the homogenization of cultural differences, so it is equally important to recognize the common basis of . . . struggle" (1990, 10).

The more serious question then, politically speaking, is not whether there are essential elements or just spare parts, but who asks such questions, how, and why. As critics, artists, and activists, then, let us openly acknowledge, eagerly expect, and diversely desire different answers.

Taken together, though, I would argue that these two films do begin to shake up "the inevitability of a symbolic order based on a logic of limits, margins, borders and boundaries" (Fuss, 1991, 1), even as they trouble an aesthetics of origins and a metaphysics of identity—at least where gender and sexuality are concerned. Given how much "the twin anxieties of visibility and difference . . . mobilize . . . all of the culture's assumptions about normative sex and gender roles" (Garber, 1992, 130)—and, again, let us not forget race—it may be a very good thing, therefore, if what Marjorie Garber says of essential elements versus spare parts applies equally to cinema and to sex: "The boundary lines . . . never clear or precise . . . are not only being constantly redrawn but are also receding inward . . . away from the visible body and its artifacts" (1992, 108).

Thanks to Lucy Fischer, Chris Straayer, and Su Friedrich for their insightful suggestions for revision.

Works Cited

Biskind, Peter. "Pods, Blobs, and Ideology in American Films of the Fifties." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director, edited by Al LaValley, 185–197. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Braucourt, Guy. "Interview with Don Siegel." In Focus on the Science Fiction Film, edited by William Johnson, 74–77. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972.

Brown, Judith. Immodest Acts. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

———. "Renaissance Lesbian Sexuality." Signs 9, no. 4 (summer 1984): 751–758.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Christian, Barbara. "The Race for Theory." In The Nature and Context of Minority Discourse, edited by Abdul JanMohamed and David Lloyd. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Couder, Martine. "Unsichtbare Gegner." Skrien Filmschrift 137 (September–October 1984): no page available.

Cranny-Francis, Anne. "Feminist Futures: A Generic Study." In Alien Zone, edited by Annette Kuhn, 219–228. London: Verso, 1990.

Export, Valie. "Aspects of Feminist Actionism." New German Critique 47 (spring-summer 1989): 69–92.

———. "Persona, Proto-Performance, Politics: A Preface." Discourse 14, no. 2 (spring 1992): 26–35.

———. "The Real and Its Double: The Body." Working Paper No. 7 (1988), Center for Twentieth-Century Studies: 1–20. Reprinted in Discourse 11, no. 1 (fall-winter 1988–89): 3–27.

Friedrich, Su. "Radical Form: Radical Content." Millenium Film Journal 22 (1989–1990): 118–123.

Fuss, Diana. "Inside/Out." In Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, edited by Diana Fuss, 1–12. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Garber, Marjorie. Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Gever, Martha. "Girl Crazy." Film and Video Monthly 11, no. 6 (July 1988): 14–18.

Hanlon, Lindley. "Female Rage: The Films of Su Friedrich." Millenium Film Journal 12 (1982–1983): 79–86.

Hofmann, Werner, and Hans Hollein. Valie Export: Dokumentations-Ausstellung des Osterreichischen Beitrags zur Biennale Venedig 1980. Vienna: Bundesministerium für Unterricht und Kunst, 1980.

Holmlund, Chris. "Displacing Limits of Difference: Gender, Race, and Colonialism in Edward Said and Homi Bhabha's Theoretical Models and Marguerite Duras's

Experimental Films." Quarterly Review of Film Studies 13, no. 1–3 (May 1990): 1–22.

———. "Fractured Fairytales and Experimental Identities: Looking for Lesbians in and around the Films of Su Friedrich." Discourse 17, no. 1 (fall 1994): 16–46.

———. "When Is a Lesbian Not a Lesbian?: The Mainstream Femme Film and the Lesbian Continuum." Camera Obscura 25–26 (November 1991): 96–119.

JanMohamed, Abdul, and David Lloyd. "Introduction: Toward a Theory of Minority Discourse: What Is to Be Done?" In The Nature and Context of Minority Discourse, edited by Abdul JanMohamed and David Lloyd, 1–16. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Kaminsky, Stuart M. "Don Siegel on the Pod Society." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director, edited by Al LaValley, 153–157. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

———. "The Genre Director: The Films of Don Siegel." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director, edited by Al LaValley, 177–181. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Kiernan, Joanna. "Film by Valie Export." Millenium Film Journal 16–18 (fall-winter 1986–87): 181–187.

Lang, Robert. American Film Melodrama. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Laura, Ernesto G. "Invasion of the Body Snatchers." In Focus on the Science Fiction Film, edited by William Johnson, 71–73. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972.

LaValley, Al. "Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Politics, Psychology, Sociology." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director, edited by Al LaValley, 201–205. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Lukasz-Aden, Gudrun, and Christel Strobel. Der Frauenfilm. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne, 1985.

Lyon, Elizabeth. "Invisible Adversaries, or Body Doubles." Paper presented at the Modern Languages Convention, 1991.

MacDonald, Scott. A Critical Cinema. Vol. 2. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992, 283–318.

Mueller, Roswitha. "The Uncanny in the Eyes of a Woman: Valie Export's Invisible Adversaries ." Sub-Stance 37–38 (1983): 129–139.

———. Valie Export: Fragments of the Imagination. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994.

"Plastic Surgery under Fire." For Women First 4, no. 23 (8 June 1992): 14–25.

Powell, Michael. A Life in Movies. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987.

Pulleine, Tim. "Black Narcissus." Films and Filming 377 (February 1986): 31.

Richards, Renée. Second Serve. New York: Stein and Day, 1983.

Rodrig, Antonio. "Black Narcissus." Cinématographe 109 (April 1985): 5.

Rogin, Michael Paul. "Kiss Me Deadly: Communism, Motherhood, and Cold War Movies." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director, edited by Al LaValley, 201–205. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Sayre, Nora. "Watch the Skies." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director, edited by Al LaValley, 184. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Sheehan, Henry. "Black Narcissus." Film Comment 26, no. 3 (May–June 1990): 37–39.

Sobchack, Vivian. Screening Space. New York: Ungar, 1987.

Steffen-Fluhr, Nancy. "Women and the Inner Game of Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers ." In Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Don Siegel, Director , edited by Al LaValley, 206–221. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Sturken, Marita. "Invisible Adversaries. " Afterimage 8 (May 1981): 18.

Sykora, Katharina. "When Form Takes as Many Risks as Content." Frauen und Film 46 (February 1989): 100–106.

Telotte, J. P. "The Doubles of Fantasy and the Space of Desire." In Alien Zone , edited by Annette Kuhn, 152–159. London: Verso, 1990.

Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies! Jefferson: McFarland, 1982.

White, Patricia. "Madame X of the China Seas. " Screen 28, no. 4 (autumn 1987): 80–95.

Young, Robert. White Mythologies: Writing History and the West. New York: Routledge, 1990.