Mckinley Pictures

When President McKinley went to the Pan-American Exposition early in September 1901, James White and an Edison camera crew were present to take advantage of their special photographic concession. On September 5th they took a simple one-shot film of McKinley delivering a speech that praised American business, competition, and the tariff. The next day, while holding a reception in the Temple of Music, the president was shot in the chest and abdomen by Leon Czolgosz, a Cleveland anarchist. The Edison crew, waiting outside, took a "circular panorama" of the anxious crowd soon after the assassination was announced. Suddenly, the Edison Manufacturing Company had a moving picture exclusive on the biggest news event of the new century: "Our cameras were the only ones at work at the Pan-American Exposition on the day of President McKinley's speech, Thursday September 5th and on Friday September 6th, the day of the shooting. We secured the only animated pictures incidental to these events."[68] Three films, fewer than first announced, were offered for sale: President McKinley's Speech at the Pan-American Exposition, President McKinley Reviewing Troops at the Pan-American Exposition , and Mob Outside the Temple of Music at the Pan-American Exposition .[69] Shortly thereafter, frame enlargements were published in the New York World , along with a brief article featuring White's role and mentioning several anonymous employees, almost certainly including Edwin Porter and J. Blair Smith.[70]

When President McKinley died a week after the shooting, Edison employees filmed the funeral ceremonies as they moved from Buffalo to Washington to McKinley's hometown of Canton, Ohio. Eleven films were offered for sale. These were no longer simple, single-shot subjects comparable to those the Edison Company had sold during the Spanish-American War. Most scenes, such as Taking President McKinley's Body from Train at Canton, Ohio , consisted of several shots that were too brief to be easily sold or exhibited individually. With the Edison Company anxious to get these groupings of moving snapshots on the market, they released unedited camera rushes that included flash frames.

When purchasing the McKinley films, exhibitors had two basic choices: they could either acquire single subjects for their programs or purchase a prearranged selection of subjects joined together by dissolving effects. The Complete Funeral Cortege at Canton, Ohio (675 feet) is one example of this second option. The order given by the Edison Company was:

McKinley's last speech.

Arriving at Canton Station (40 feet)

Body Leaving Train at Canton, Ohio (60 feet)

President Roosevelt at Canton Station (90 feet)

Circular Panorama of President McKinley's House (80 feet)

President McKinley's Body Leaving the House and Church (200 feet)

Funeral Cortege Entering Westlawn Cemetery at Canton, Ohio (200 feet)[71]

Dissolving from scene to scene, the production company was able to give the exhibitor a standardized program with a little something extra.

Many, perhaps most, exhibitors chose not to abdicate their editorial role. A programme from the Searchlight Theater in Tacoma, Washington, shows that a different selection was made for its display of McKinley films. The traveling exhibitor Lyman Howe also devoted a substantial portion of his semiannual tour to films of the Pan-American Exposition and McKinley's funeral, but presented yet another selection and ordering.[72] Although a programme does not survive for John P. Dibble's presentations, this New Haven-based traveling showman began with films of the Pan-American Exposition, included McKinley's last speech, and ended with the funeral ceremonies.[73]

Exhibitors enjoyed a financial windfall as people flocked to see the

Pan-American Exposition by Night goes from day to night as the camera makes a sweeping pan of the exposition.

McKinley/Exposition films. Edison likewise benefited. From October to December 1901, when these films were in greatest demand, the Kinetograph Department set a sales record unmatched during any three-month period between 1900 and 1904.[74] Porter and his associates continued to exploit this trend with The Martyred Presidents (© October 7, 1901), a film indebted to nineteenth-century magic-lantern subjects like Our Departed Heroes .[75] In the film's opening scene, photographs of Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley fade in and out, framed by the static image of a monument. The second shot, a brief tag, shows the assassin kneeling before the throne of justice. The dissolving on and off of photographs, once done by the exhibitor in lantern shows, was now done by the moving picture photographer. While the catalog considered the film "most valuable as an ending to the series of McKinley funeral pictures,"[76] the question of its placement in a program was a decision left to the exhibitor.

Kinetograph personnel invested further energies in the Buffalo area during mid to late October. Shortly after making The Martyred Presidents , Porter photographed Pan-American Exposition by Night[77] While Porter and subsequent historians referred to this film for its early use of time-lapse photography, its two-shot construction is also noteworthy. There is a pan in the first shot taken during the day that is continued from the same point, in the same direction, and at the same pace in the second shot filmed at night. Here Porter combined two common stereopticon procedures. The temporal relation between the two shots is characteristic of day/night dissolving views, a popular genre of lantern show entertainments: the image of a building during the day gradually dissolved to the identical view at night (the second view was often produced by using a day-for-night technique). The panorama as a genre pre-dated the cinema by more than a hundred years and found its way into many forms of popular culture, including lantern shows, for which long slides were slowly moved through the lantern. In 1900 it was adapted to moving pictures as the "circular panorama,"

with the photographer rather than the projectionist responsible for the speed and direction of the movement. The combination of day/night dissolving views with a panorama in moving pictures was a visual tour de force. "This picture is pronounced by the photographic profession to be a marvel in photography, and by theatrical people to be the greatest winner in panoramic views ever placed before the public," declared the Edison catalog.[78]

The principle of multi-camera coverage, which the Edison Company had applied to important news events in the late 1890s, continued, not only with the McKinley funeral pictures but for Captain Nissen Going Through Whirlpool Rapids, Niagara Falls , photographed on October 10, 1901. As an Edison description explained,

Captain Bowser is shown embarking in his boat at Niagara Falls, Ontario. After he carefully embarks, the 'Fool Killer' is taken in tow by a rowboat and towed out into the stream. Here the captain is seen to go below the whaleback deck and close the hatch. Then the trip through the Rapids begins. One of our cameras, which was operated by a second photographer, was in waiting on a trolley car, and the progress of the 'Fool Killer' is followed on its entire trip through the mad waters.[79]

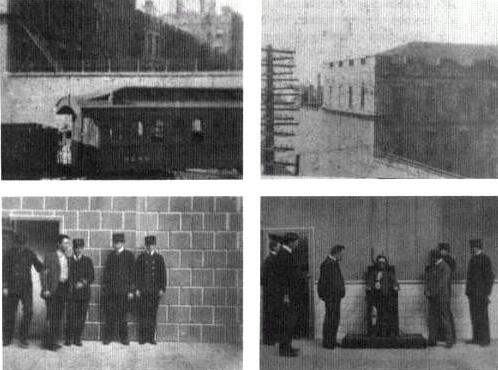

Here the advantages of having two cameras focus on two different aspects of a single situation were apparent. Just prior to the closing of the exposition, the photographers shot their last Pan-American films, including another night view of the exposition (Panorama of Esplanade by Night ). They also took two short panoramas of nearby Auburn State Prison on October 29th, the morning that Czolgosz was executed inside.[80]

Executions, still considered a form of entertainment by some turn-of-the-century Americans, had been popular film subjects during the novelty phase of cinema. Audiences had been impressed that the image of someone who was demonstrably dead could appear so lifelike.[81] With sensationalistic newspapers detailing the steps leading to Czolgosz's death and the New York Times noting the large number of applicants who hoped to watch McKinley's assassin die, it was hardly surprising that the Edison firm chose to make Execution of Czolgosz, with Panorama of Auburn Prison .[82]

The New York World reported that "the owner of a kinetoscope telegraphed that he would pay $2,000 for permission to take a moving picture of Czolgosz entering the death chamber."[83] If White and Porter hoped to film Czolgosz on his way to being executed, they had to be content with filming the exterior of the prison and making "a realistic imitation of the last scene in the electric chair." This studio reenactment, "faithfully carried out from the description of an eye witness" was based, one can be sure, on newspaper reports.[84] Edison production personnel took roles in the film, and James White can be seen signaling "cut" to the cameraman (Porter) just before the film ends. (According to Iris Barry, the Edison Company also tried to recreate Czolgosz's assassination of McKinley, but finally thought better of it.)[85]

Execution of Czolgosz.

Although Execution of Czolgosz, with Panorama of Auburn Prison contains only four shots and "three scenes," the resulting film has a surprisingly sophisticated structure. According to the Edison catalog:

The picture is in three scenes. First: Panoramic view of Auburn Prison taken the morning of the electrocution. The picture then dissolves into the corridor of murderer's row. The keepers are seen taking Czolgosz from his cell to the death chamber. The scene next dissolves into the death chamber, and shows State Electrician, Wardens and Doctors making final test of the chair. Czolgosz is then brought in by the guard and is quickly strapped into the chair. The current is turned on at a signal from the Warden, and the assassin heaves heavily as though the straps would break. He drops prone after the current is turned off. The doctors examine the body and report to the Warden that he is dead, and he in turn officially announces the death to the witnesses. 200 ft.[86]

The film's longer, copyright title acknowledges that it is a hybrid that combined two genres: the panorama and the dramatic reenactmerit. An exhibitor could buy the narrative portion with or without the opening panoramas. Thus the editorial decision of the producers could be disregarded if the exhibitor so de-

sired. The film, however, was not simply two separate subjects held together by a dissolve and a common theme: it also made use of a spatial, exterior/interior relation between shots that was beginning to be employed by other filmmakers.[87] The dissolve between the first two scenes not only linked outside and inside, but actuality and reenactment, description and narrative, a moving and a static camera.

The panoramas at the beginning provide the narrative with a context, a well-constructed world in which the action can unfold. Photographed on the day of the execution, the first shot pans with a train as it approaches the prison and then reveals an empty passenger car.[88] It was such a car that brought the witnesses to the prison and led to the final stages of the execution.[89] The second shot shows a more foreboding portion of the facade. These shots distinguish this reenactment film from its contemporaries by heightening the realism. At the same time, they are part of a drama that leads the audience step by step to a vicarious confrontation with the electric chair and a man's death.

The temporal/spatial relation between the second and third scenes is more complex than a casual viewing would suggest. For a modern audience, schooled in the strategies of classical cinema, the pause before Czolgosz's entrance in the last scene facilitates the illusion of linear continuity by allowing time for the prisoner to move from one part of the prison to another. The New York Times noted, however, that "Czolgosz was confined in the cell nearest to the death chamber, so that when he entered the execution room this morning he had only to step a few feet through the stone arch."[90] This spatial relation between the two rooms was known by Edison personnel and most spectators: it suggests the kind of temporal overlap occasionally found in theater. The narrative event was not structured like the descriptions in the New York Times and New York Journal . These started with (1) the activities in the death chamber prior to Warden Mead's signal to have the prisoner brought in—including the testing of the chair, (2) then moved to Czolgosz's cell and his march down the corridor, and (3) shifted back to the death chamber with a description of the execution. The Times maintained a rigorous chronological account of events, while moving freely from a description of activities in one space to activities in another. Porter, in contrast, maintained individual scenes intact by manipulating early cinema's flexible pro-filmic temporality.

Execution of Czolgosz is remarkable for its control of pro-filmic elements. There is a purposeful elaboration of plot in the dramatic portion of the film: Czolgosz is not simply led off and executed. At the beginning of the second scene, the prisoner is at the doorway of his cell. After a few moments, the guards enter from the right, and he withdraws from the doorway. The guards open the cell door, go in and bring him out. He is brought from his cell reluctantly but without resistance. Acting and gesture are restrained, motivated by the desire to reenact the execution in as realistic a manner as possible, in marked contrast to Porter's comedies, which were indebted to burlesque and the comic strip. De-

viations from the norms of classical cinema in acting style and schematic set construction have sometimes been attributed to the naivete of early cinema, a lack of control over pro-filmic elements and insensitivity to "the demands of the medium." In Execution of Czolgosz , control and sensitivity are not the issues. This affirms the fact that Porter's comedies were "crude" because he was working within a genre where crudity was expected—burlesque and realism being fundamentally at cross-purposes. Yet despite the reliance on reenactment in Execution of Czolgosz , the two interior scenes are photographed against sets that show a single wall running perpendicular to the axis of the camera lens. As with The Finish of Bridget McKeen , the images lack almost all suggestion of depth—flattened not only by the sets but by the actors, who move parallel to the walls.