Nine—

The French Remark:

Breathless and Cinematic Citationality

David Wills

I am not, it seems, in the cinema. Not even in the video. This all comes at a complicated series of removes. At some point I could have said, "I am in the cinema," and left the ambiguity at play between the theater room and the film on the screen. The metonymy works for theater and cinema, but not for video. Yet this is the position I am in, watching a film on video years after its commercial release. In fact, since I was only six in 1959, I was never in the cinema of A bout de souffle; it has always come to me by means of a series of detours. But the metonymic ambiguity of being in the cinema allows for that, and a more general detour mechanism allows even for the current state of affairs whereby I am watching the American remake of A bout de souffle (Breathless , 1983) before I take another look at the original. The chronological wires are crossed: the first thing I watch is a remake.

So it seems I am really not in the cinema. Not even in the video. I am here uttering these things to you the reader, having been there, various versions of "there," writing them. Everything I utter has a complicated play of quotation marks about it, not just because this reading is something of a recital of what I have previously written, but because in a more irredeemable fashion everything I write refers back to a "there"—a film, an experience of watching it, over and over—it refers back to an act of detaching, operations of excision and grafting, functions of de- and recontextualization. That which is a necessary fact of any reading, what we can call the "quotation" or "citation" effect, becomes even more explicitly the case once we come to talk about remakes.

But perhaps I am in the cinema. Perhaps even in the film. Perhaps, even as I write this in front of a screen—a cinema screen, a TV-video screen, a word processor monitor screen, a page—and even as this gets repeated like some sort of screen in front of its submobile and visually stimulated, if not

scopophilic, reader, I am more than ever in the cinema. I say that because as viewer and reader myself I am automatically and inevitably involved in the grafting or (de) recontextualization process just referred to. But I by no means initiate such a process. The film was never an intact and coherent whole offered up for my consumption. It was always, one might say, in the process of writing itself. Quoting, one might say "always already." Always writing and quoting itself. Remarking and remaking itself. Thus what is being commonly and communally referred to here as the remake, the possibility that exists for a film to be repeated in a different form, should rather be read as the necessary structure of iterability that exists for and within every film. That, at least, is my hypothesis, drawn of course from Derrida in work such as "Signature Event Context" (1982) and "The Law of Genre" (1980). First, "every sign . . . can break with every given context, and engender infinitely new contexts, in an absolutely nonsaturable fashion"; but second, as a corollary to that "the possibility of citational grafting . . . belongs to the structure of every mark" and "constitutes every mark as writing" (1982, 320), that is to say, as iterable mark, as remark, as remake. And the cinematic mark is no exception. The slightest mark is being remarked or remade even as it is being uttered or written, to the extent that it cannot make itself as full presence, as intact and coherent entity. It constitutes itself as reconstitutable, at least it must do so in order to function, that is to say, in order to make sense.

Thus what this book refers to as the remake—the essays demonstrate that as soon as we investigate the category its edges begin to blur—is but a particular case of what exists within the structure of every film. The remake has its own codes and practices and by means of them it is able to distinguish itself from another category of films: those not remade in the same set of varied institutional forms. But what distinguishes the remake is not the fact of its being a repetition, rather the fact of its being a precise institutional form of the structure of repetition, what I am calling the "quotation effect" or "citation effect," the citationality or iterability, that exists in and for every film.

The particular case of the remake that I remark upon here is that of the French film reconstituted as Hollywood product. Now, given that something like the Hollywood film or the "classic narrative film" seeks to erase the traces of its own production, and given that, as I have just maintained, after Derrida, the form of production of any mark can be called, between quotation marks, "writing," then it stands to reason that what a Hollywood remake would seek to erase from a French film would be precisely the traces of writing. For purposes of economy, shortly to be explained, I shall concentrate that idea by proposing the following self-evidence: what the Hollywood remake seeks to have erased from a French film is quite simply the subtitles. I can hear the reproach that my argument, quoted from

Derrida, for an idea of "writing" as trace that belongs to every mark, is negated or at least rendered seriously reductive by this recourse to writing in the literal sense of words upon the screen representing a translation of what can be heard on the sound track. However, my strategy has its own logic, namely, that it is the particularly explicit and privileged manifestation of the structure of writing that is the subtitle that enables me to develop the sense of the remake and remark, and that for the following reasons.

First, the subtitles do not—or at least the same ones do not—appear in the "original" foreign language version. When they do appear, as for instance in the English-language version, they show the film "in process," in production if you will: in the process of being transposed, translated, exported. They show that in being exported the film explicitly reveals its supplementary structure, its iterability, its (de) recontextualization. As a result the film might be said to come apart at a most basic level of cinema, namely, in the combination of image and sound tracks. Once subtitles are added the sound track reveals its difference from the image track—the seamlessness of spoken dialogue and moving lips is rent—but it does so on the level of the image track such that the seamlessness of the image track itself as coherent or intact reproduction of the real, as uniform visual surface and depth, is also rent.

Second, as I have noted (and I am saying nothing but the obvious here, nothing that has not already been observed or said, for I am quite simply quoting), the subtitles offer a translation of what is heard on the sound track, and as such they repeat the spoken sound track and so repeat the structure of iterability of the film. For in writing itself and in automatically being rewritten, the film translates itself, repeats itself with a difference, recontextualizes itself to a foreign place within itself. But the repeating effect is redoubled as it is reflected in the inversion[1] of the translated subtitles. The subtitles provide an abyssal form of that iterability by being inserted into the film or inscribed on the surface of the film; by appearing at the bottom of the screen they cause the bottom of the film to fall out.

Last, the translation that is the subtitles renders explicit the particular form of transposition that the Hollywood remake of a foreign film involves, namely, its removal to a more familiar place—a tramp falls into a Beverly Hills swimming pool instead of the Seine (Down and Out in Beverly Hills [1985], Boudu sauvé des eaux [1932]), a Las Vegas petty criminal falls for a French architecture student instead of a French existentialist hero falling for an American student and would-be journalist (Breathless [1983], A bout de souffle [1959]), three men are reset with their baby in America (Trois hommes et un couffin [1985], Three Men and a Baby [1987], like the cousins in love (Cousin, cousine [1975], Cousins [1989], like the recidivist female punk heroine called in to work for this government (La Femme Nikita [1991], Point of No Return [1993]), and so on. The remake neutralizes the otherness

of the foreign film, in general, but in no way more clearly than by effacing the subtitles. However, the paradox is that in erasing the effects of otherness, in removing the subtitles, Hollywood is duped into believing it has restored the seamlessness of a coherent, intact, and consumable image (and sound). It is unaware that it is working within the structure of the supplement and adding to, rather than subtracting from, the play of differences. The film Hollywood produces becomes enfolded into the abyss that is the subtitles of the original film. As a translation and transposition of the foreign original, it takes the place of the explicit form of that foreignness that inhabits the subtitles, it inscribes itself within the structure of noncoherence and nonintegrality, and, in transferring the film to a familiar context, however much it might presume to erase those effects of difference, it simply carries them over into the new product. That is, in any case, my contention, and I would like to explore it further through the remaking of Godard's A bout de souffle into Jim McBride's Breathless .[2]

Godard's film is quite obviously a privileged object for this discussion. It is a film that is less obviously concerned with the erasure of the traces of its own production than many others, although more so than other Godard films. And it is a film that has been given a thoroughly Derridean reading by Marie-Claire Ropars in her exemplary article "The Graphic in Filmic Writing: A bout de souffle or the Erratic Alphabet." But for these same reasons it is a highly unusual candidate for a Hollywood remake. Given the level of its "invention" when it appeared in 1959, its use of the jump cut, its borrowings from film noir and Hollywood, its self-reflexivity in general, it would seem to present a number of quandaries for whomever sought to make it over in the early eighties, inevitably raising the questions of neutralization and domestication. Dated as a revolutionary film, as one of a group of films that brought in the New Wave, but also dated by that historical reference, it could not but represent a problem of transposition, the problem of transposition and translation, the problem of the remake as remark. Although the film was made by a director known for his independence, and although McBride argued strongly for the right to remake the film and fought hard to produce something worthy of the original (cf. McBride, 1983), the American Breathless met with a lukewarm critical reception on both sides of the Atlantic, being dismissed as academic and certainly "not Godard."

However, I find what results to be particularly interesting: on the one hand McBride's film demonstrates the practical compromise of a film that has retained something of the "hip" quality of Godard's film but privileges the narrative structure more than does the French original, while on the other hand it reveals that what I have just called a "compromise," putting the word between quotation marks, is a fact of any film and any remake: it

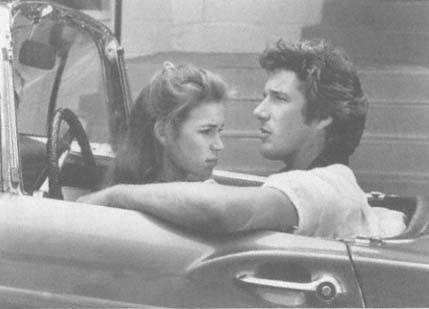

Figure 18.

Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg capture the cross-cultural

playfulness of postmodern young love in Godard's Breathless (1959).

necessarily both covers and fails to cover the discontinuities or incoherences that structure it; it can only ever repeat itself as difference and inscribe those differences in the process of its writing. In other words, because of the multiple play of otherness that works so explicitly through A bout de souffle , two things occur: the first is another self-evidence, simply that not all the otherness gets neutralized; the second is the other side of that, namely, that otherness can never be neutralized, it will only ever reinscribe itself. Breathless is something of the dilemma those ideas represent.

In A bout de souffle small-time gangster Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) has had a brief affair with the American student, newspaper girl, and aspiring journalist Patricia Fracchini (Jean Seberg) on the Côte d'Azur. (See figure 18.) He halfheartedly kills a policeman, returns to Paris in order to fetch Patricia and flee to Italy, but is held up by her tergiversations and a check he can't cash and is finally killed by the police after she denounces him. In Breathless Jesse Lujack (Richard Gere) has an affair with French architectural student Monica Poiccard (Valérie Kaprisky) in Vegas, even more "accidentally" kills a highway patrolman and returns to Los

Figure 19.

Richard Gere and Valerie Kaprisky pause while on the run

in Jim McBride's reverse-role remake of Breathless (1983).

Angeles to fetch her and head for Mexico. (See figure 19.) She also denounces him and he is presumably shot, although, as we shall see, the final frame does not show it.

One could discourse at length on the slight and not-so-slight differences between the two versions. Here are some of them: whereas Poiccard wants to be Bogart, Lujack wants to be Jerry Lee Lewis or the comic-book hero the Silver Surfer; whereas in the French version there is a long "seduction" scene in the cramped quarters of Patricia's Paris apartment, in the American version this scene takes place between the large rooms and swimming pool of a Los Angeles apartment block; whereas the Paris detectives say "[O]n ne plaisante pas avec la police parisienne" ("[O]ne doesn't kid around with the Paris police"), the American says "Don't F-U-C-K with the L-A-P-D"; whereas in Godard's film it is Godard himself who plays the part of a passerby who recognizes the gangster from a newspaper photograph, I have no idea whether the tramp on the steps of a church who does the same is Jim McBride; whereas it is the American woman who introduces the Frenchman to William Faulkner's work in Godard's film, it is the Frenchwoman who introduces the same to the American in Breathless . On the basis of those differences one might begin to make an argument concerning

McBride's adaptation of Godard's film, his domestication or neutralization of it. One might refer to the less marginalized, more institutionalized female figure that has the effect of making the narrative less psychologically convincing—Monica seems much "straighter" than Patricia, less likely to be seduced by Jesse, who appears in turn as more of a boor than Michel; or to the compromise required by changing standards of cultural literacy—Faulkner is considered to be enough of a foreign reference for an American audience without having recourse to some canonical example from French literature. But the explanations for such differences would have, somehow, to collaborate with that which they sought to describe or critique, to some extent explaining away the differences by taking into account the "practical" considerations of adaptation: changes in history as well as geography (De Gaulle's France on the cusp of the sixties versus Reagan's eighties); the desire for a psychological contrast that has Monica fascinated and seduced by someone totally opposite; the importance of the quotation from Faulkner in its own right ("Between grief and nothing I will take grief"). In other words in accounting for these sorts of differences one would get caught up precisely in the question of differences between one film and another, reaching down to the smallest details of the texts but overlooking for the most part the matter of differences within the text, its intrinsic remarkability.

In one respect the differences just referred to would lead us to such a remarkability, namely, in respect to what has been called the self-reflexivity of Godard's A bout de souffle , its constant reference to matters cinematic. However discussion of such references does not necessarily remove us from the framework of complicit explanation just referred to. While it is true that Bogart has been replaced by Jerry Lee Lewis, and film posters and young people selling cinema journals do not appear in or out of the background of Breathless , Hollywood can never be far from the foreground of a fantasy romance set in Los Angeles. And in any case references to cinema are not absent from McBride's film: there is an Antonioni-like frame of Monica standing at a bus stop that advertises the Hollywood Wax Museum, in front of a military cemetery; the final scene takes place in the ruins of Errol Flynn's "Pines"; and there is the sequence in the movie theater, much more developed than in Godard's film, that I shall return to shortly. The argument is easily made that it would not be a good artistic choice for a film made in the eighties to be self-conscious in the same way as one that was like a new wave breaking in 1959. Similarly, Godard's signatory appearance in his own film in fact says little. Presumably he was no more recognizable to a 1959 French audience than Jim McBride would have been to us in 1983. And what would a contemporary audience raised on Hollywood's permanent fear of self-recognition do with a camera jerking across the sky to the sound of gunshots as Godard's Michel pretends to shoot, like

a converse of Camus's outsider, at the blinding sun, or with a Michel who turns to the camera as he drives to say, "If you don't like the sea, if you don't like mountains, if you don't like cities, then go and get fucked!" (["allez vous fair foutre!"]—this last invective already sanitized by a milder translation in the subtitles)? These things have attained historical inscription as marks of Godard's filmmaking practice that can not easily be translated.[3] So the discussion would bring us back to questions of compromise and problems of translation without, for all that, allowing us to think the questions through very far.

Yet if we read such references less as self-consciousness or self-reflexivity and more as self-iterability, as cinema quoting itself, drawing attention to itself as effects of writing, such things come to form the basis for another level of dislocations that, as I have suggested, turn the question around. The film doesn't just say "I am a film, I am an object-in-construction being presented to you as a self-constituted commodity," it also says: "I am a series of images within images, sounds within sounds, subject to constant recontextualization. The images that constitute me are constantly undercut, in the process of their constitution, by their inability to define themselves as presences without at the same time falling prey to effects heterogeneous to those presumed definitions. Thus I am a series of images within images that are never just or never completely images, never untouched by radical difference, and never purely pictorial without also being graphic. There is never the immediacy of perceived objects without also the presence of hieroglyphic labyrinths; thus I am always graphic in two senses, that of the pictorial and that of the written." The still image of Bogart on the poster of The Harder They Fall and of Michel imitating the way Bogie passed his thumb across his lips becomes not just an image of a poorly formed identity, a petty criminal with personality problems trying to be a larger-than-life celluloid hero, but a type of freeze-frame that arrests the narrative flow, a silence within the noise and music of the continuous images, a problem of identity for the images themselves. The image of Bogart has inscribed upon it like a title or a signature the image of Poiccard, and vice versa. Similarly, when Godard playing a man on the street looks at a photograph in the newspaper he is reading, then looks at Michel, then back at the newspaper photograph, then crosses the street to show the same photograph to two policemen, Godard doesn't just sign his film and wink at the audience in the manner of Hitchcock. He transfers the question of identity posed at the level of the image—and repeated here by means of the competing images of Michel, still and moving, arrested and passing, here and there, past and present, print and celluloid, written and pictorial—he transfers that question of identity to the level of his film as a whole. Once Godard is in it, on its surface, it can no longer simply be a film he has made; nor does it become instead performance art; rather his appearance as a character point-

ing at an image in another medium, inscribing his body or his finger on its surface, is like a name written across his whole film that erases its wholeness and renders it irredeemably heterogeneous. Any translation or transposition of the film will henceforth necessarily be a translation of that heterogeneity, a translation from foreignness to foreignness.

In her article, Marie-Claire Ropars has traced such effects through the play of language in A bout de souffle , especially the play of the written word within the image. Although she in no way limits the idea of writing to these chance or designed appearances of the written word, her strategy enables her to develop the notion of an image constantly worked upon and over by its others. It is her conclusion that I have used as the basis for my argument here, namely, that what the film offers in the final analysis is a question about translation, a problem with translation. All the way through, A bout de souffle keeps coming back to the matter of inter- or translinguistic usage. And it would be incorrect to presume that that is all a function of a relationship between a less-than-bilingual American woman and a Frenchman. Patricia does get her French wrong from time to time, but Michel also corrects the usage of another woman, presumed to be French, whose apartment he visits in order to steal some money. And he himself resorts more than once to the Swiss usage for the numerals seventy and eighty (one could hear that as another signing by Godard, who is of Swiss origin). There is no pure French in the film, but always effects of translation, within a language, between languages.

However, it is in the final exchange of the film that, as Marie-Claire Ropars points out, the matter becomes concentrated, bringing with it a complicated thematics of misogyny that has the female bear the weight of linguistic otherness (156–58). "Tu es vraiment dégueulasse " ("You are really shitty," my translation), Michel says as he lies dying. When Patricia asks the policeman what he said he replies "Il a dit: 'Vous êtes vraiment une dégueulasse' " ("He said: You are really an arsehole" ["bitch" in subtitles]). This is no simple quotation of Michel's words by the policeman. First, he gives the effect of reported speech and so changes the familiar "tu" to the formal "vous," but at the same omits the "que " ("that") so that syntactically his words amount to a quotation of direct speech. But his quotation is a misquote, for he inserts an indefinite article before "dégueulasse " so that that adjective becomes a noun with a stronger sense—"shitty" becomes "arsehole" or something similar, just as "con " ("stupid") as adjective becomes "cunt" as a noun. Patricia is left asking "Qu'est-ce que c'est 'dégueulasse'? " ("What does 'dégueulasse ' mean?"), a question that receives no response, except in the subtitles of the English-language version where many of the preceding subtleties take on quite different nuances.[4]

In McBride's Breathless there are of course similar linguistic transpositions. First of all Monica has a foreign version of the French name "Monique."

She has to have Jesse explain to her what jinxed means, and what a desperado is, although in the latter case the word should be evident enough to a speaker of a Romance language. She refers to Jesse as "taré ," another word that can alternate between an adjective and a noun—"It means crazy, a disgusting person, jerk," she explains—and he appropriates the word for his own use. But in the American film, as in the French, the most interesting linguistic play occurs in the more precise form of the misquotation, in terms of a translation that occurs more strictly within the space of the same.

The first example comes from the scene in the cinema. Here, the characters enter the space behind the screen and watch the images in mirrored form playing in black and white before them. This is first of all, it seems to me, a more radical mise en abyme of the cinematic than anything in A bout de souffle . There are competing cinematic surfaces, inscribing their differences, on almost the same visual plane—this isn't just characters in a film watching a film. The images seen on the screen, from Joseph H. Lewis's Gun Crazy , occur as an inverse background, a sort of subtitle or translation, to the film Breathless —Lewis's characters are speaking of the high stakes in their relationship as Jesse and Monica begin to make love in the moments after a close escape from the police. But that effect is inverted again when Jesse and Monica in turn inscribe themselves within the film they are watching, back to front, especially by means of Monica's quoting of the woman within it. She repeats the words we have just heard from Gun Crazy —"I don't want to be afraid of life or anything else"—to which Jesse replies, "You don't have to be afraid of nothing."

What the quotation has set up here is something quite different from a repetition, a transposition of words from one mouth to another. It is rather a recontextualization radical enough to amount to a reversal, an inversion, according to what I shall call, for reasons that the rest of what I have to say will explain, a logic of the chiasmus.[5] It reoccurs quite clearly at the end of Breathless . After Monica returns to inform Jesse she has denounced him to the police, she tells him to leave so as not to be apprehended. He wants to stay, because he loves her, and believes her to love him. "Do you love me?" he asks, then demands that she reply: "Say it!" When she doesn't, he turns the logic around and at the same time demands that she quote him: "Say you don't love me and then I'll go." She replies and quotes him: "I don't love you," but unconvincingly enough for it to be read by Jesse as meaning the opposite: "Liar!" he declares, and deciding that she loves him, rushes off to pick up the money from Berrutti and return to flee or be with her. Thus the translations and quotations run to and fro within the structure of iterability to the extent that the repetitions become inversions, contresens . Something similar happens in A bout de souffle as Patricia reverses the position of the adjective in the name of the street, Rue Campagne Première , when she denounces Michel, making the correct linguistic assump-

tion that "premier" as adjective precedes the noun, occurring in the weak position, whereas in this case it follows. Her error works as a corollary to her attempts to fathom the logic of her feelings for him, with her finally settling on the inverted formula of "Since I am mean to you I am not in love with you."

Once iterability or the remarking effect comes into play, and it does so from the beginning and never stops doing so, then any translation or transposition—that which occurs in and from the beginning as much as that occurring in the case of a remake—involves the sorts of cross-purposes just outlined. Translation necessarily occurs as a chiasmus between the homogeneity of a single sense and the heterogeneity of a divided sense: like the homogeneity of a self-evident image and the heterogeneity of that same image crossed over and crossed out by things supposedly foreign to it. There can never be a faithful remake, and not just because Hollywood demands compromises or because things get lost in translation or mistakes occur, but because there can never be a simple original uncomplicated by the structure of the remake, by such effects of self-division.

In the final analysis it no longer comes down to a question of what Breathless tries, or doesn't try to do with A bout de souffle , or even what it does or doesn't do with it. Thus in returning to the final and perhaps most important divergence between the two films, Breathless' choice of a musical subtext over the French film's use of cinema, Jerry Lee Lewis instead of Bogart, I wish above all to emphasize once more the idea of chiastic self-division that renders the American film irretrievably different from the French one, and that, paradoxically, in spite of any attempts by Hollywood to produce a more domesticated version of Godard, renders it irretrievably different from itself and eminently Godardian. On one level it comes down to the impressive work of Jack Nitzsche on the sound track and his association of a Philip Glass theme with the female character as a counterpoint to Jerry Lee Lewis for Jesse. But I doubt whether the title of that theme, "Openings," from Glassworks had anything to do with his choice. However it is by means of the musical openings produced on the sound track that McBride's Breathless breaks with Hollywood in favor of something more like Godard at the same time that it comes together as a film.

Although Godard's use of sound always recognized its force as an otherness "within" the visual field of film, in some of the films that marked his return to commercial cinema in the early eighties, contemporaneous with Breathless , the work on sound became concentrated in terms of music. That was so for Sauve qui peut (la vie ) (1979 [Every Man for Himself ]) and more explicitly for Prénom Carmen (1983 [First Name Carmen ]).[6] The effect is to seriously disrupt the distinctions between layers of the sound track on the one hand, and sound and image tracks on the other hand. A version of the same thing occurs with the sound track at the end of Breathless . The French

ending that has Michel shot in the back by the police and running for his life but to his death at the end of the Rue Campagne Première is replaced by a Jesse pausing over a gun on the ground, being urged not to pick it up by a frantic Monica and by the police who have their guns trained on him. He suddenly turns to face the police and breaks into a mimed rendition of Jerry Lee Lewis's "Breathless." The sound track music, which during this scene has used an increasingly syrupy strings rendition of Glass's minimalist piano piece "Openings," is interrupted by the beat and melody of the Lewis song; then the two compete in a melodic and rhythmic crisscross as Jesse's mime veers into a sort of expressionistic limbo. The Lewis song reasserts itself with Jesse facing Monica and singing the word from its title and the title of the film before stooping to pick up the gun and again face the police and his death.

By foregrounding the music in this way, Breathless goes beyond the self-consciousness of Jesse's worship and imitation of Jerry Lee Lewis and in a very Godardian fashion brings the music track from its offscreen position into the narrative and onto the screen. Conversely, the visual track is crossed by the sound track and the narrative is frozen in a ghostly mime. Whereas the Glass theme has been used as a pensive "feminine" contrast to the impulsive and macho Lewis songs, presumed to be never more than background, here the counterpoint suddenly takes itself literally, leading to the chiastic effect of this climax. If one wanted, one could read in the word "counterpoint" precisely such a musical and graphic chiasmus by translating it or transposing it as follows: the word "point" would come to be the musical or rhythmic equivalent of the word "trait," privileged by Derrida (1980, 1987) to express the heterogeneity of the line (the French word trait means both brushstroke and stroke of the pen), the divisibility of the pictorial by the graphic and vice versa. "Point" would then mean both "dot" and "beat," and "counterpoint" would express the crossing of one by the other. The counterpoint of Glass's "Openings" would then become the punctuating effect of music upon the narrative and visuals in general that occurs as that piece struggles against the beat of Jerry Lee Lewis in the final shots. It would be like the rudimentary writing effect that is the dot inserting itself as foreign otherness on the screen and on the film. As a result the film is frozen in a composition—the climactic halting of the narrative flow—that is also a transposition or translation: the crossing of the two musical themes and their imposition upon that narrative. The final sequence of Breathless thus works as an opening onto a cinematic process—an opening of the film onto itself and a crossing of the film by itself, a remaking of the marks of cinema—that can be read as far more radical than anything in A bout de souffle .

The story of the remaking of Godard's groundbreaking New Wave film is not finally about how faithful the American copy manages to be or how

original it manages to be, two paradoxical qualities requested or required of a remake. It is rather about how any film, from the explicitly Brechtian to the most seamless Hollywood product, works as a quotation of itself, the repetition or rehearsing of its own differences. The story of A bout de souffle , carried over to Breathless is, after all, about a problem with a check, a check that can't be cashed, a written promise that can't be immediately fulfilled in the form of hard currency. It is therefore about a problem with different media within a system of exchange, like the visual and audio media of cinema, and also a problem with signatures. The problem Michel faces is that although the check is made out to him, it is crossed, made nonnegotiable, requiring it to be processed through the institutional rigors of a bank account. It has lines drawn or written across it and needs more writing and stamping on the back before it can be of any use to him. It is also crossed in the sense suggested by the French word barré , meaning blocked, immobilized. In the American Breathless the problem is similar, although it is the check itself, as written monetary form—or written monetary form different from cash, since there is no nonwritten form—that holds Jesse up and allows the police to close in on him. Either way, the check requires some form of endorsement, a structure that can be called—especially since this is a check that travels to a foreign land, like a traveler's check—that of the countersignature. But, as Derrida (1982, 1984) has shown, what the countersignature does in reaffirming the authenticity of the original signature is subvert that very authenticity by showing the presumed singular and idiosyncratic event of the signature—what makes it mine and the written code for my proper name—to be repeatable and thus subject to the same decontextualizations, in this case especially forgery, as any sign or line. The countersignature is a repetition of the same that ushers in the structure of difference; it is a quotation of the original that is a translation and transposition of it.

The American film Breathless might be read as an attempt to cash in on the credit established by Godard's film, to cash it and at the same time process it through the Hollywood institution, an institution concerned with nothing more than what is bankable. But the check stays crossed, the film remains written, for it cannot be otherwise. On the other side, once it has crossed the Atlantic, in spite of the translations and inversions, there are more crossings, there is more writing. Whichever film one reads first, whichever version is taken to be the original, the heterogeneities of cinema continue to cross both ways; the countersignature divides itself in a play of writing. A bout de souffle, "Breathless" the subtitled version, Breathless the American version, and "Breathless" the song by Jerry Lee Lewis, as well as all the versions that I have quoted in writing about it here, are caught up like so many stolen cars, in such a complicated interchange, something of the shape of which this article has sought to outline.

Works Cited

Brunette, Peter, and David Wills. Screen/Play: Derrida and Film Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Derrida, Jacques. "The Law of Genre." In Glyph 7 , 202–29. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

———. "Living On / Borderlines." In Deconstruction and Criticism , edited by Harold Bloom et al., 75–176. New York: Seabury Press, 1979.

———. Signsponge/Signéponge. Translated by Richard Rand. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

———. The Truth in Painting. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Falkenberg, Pamela. "'Hollywood' and the "Art Cinema' as a Bipolar Modeling System: A bout de souffle and Breathless." Wide Angle 7 , no. 3 (1985): 44–53.

McBride, Jim. "Sortie des Marges: entretien avec Jim McBride." Cahiers du cinéma 350 (1983): 31–34, 64–66.

Ropars-Wuilleumier, Marie-Claire. "The Graphic in Filmic Writing: A bout de souffle, or the Erratic Alphabet." Enclitic 5, no. 2; 6, no. 1 (1981–82), 147–61.

Wills, David. "Carmen: Sound/Effect." Cinema Journal 25, no. 4 (1986): 33–43.

———. "Representing Silence (in Godard)." In Essays in Honour of Keith Val Sinclair, edited by Bruce Merry, 180–92 Townsville: James Cook University, 1991.