The Old Singer

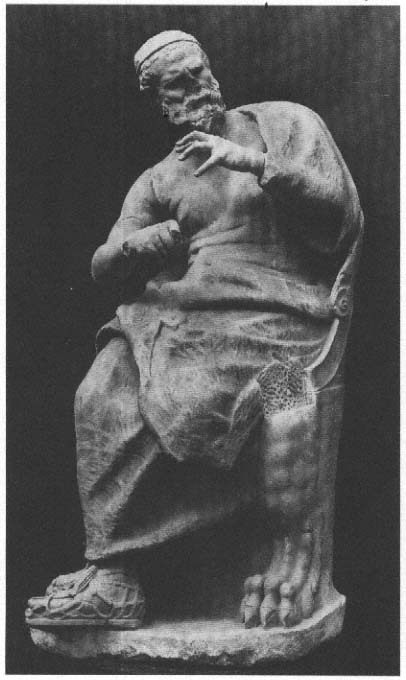

The singer is known from a superb copy of the first century B.C. , almost completely preserved (fig. 79).[1] He held a lyre in his left hand

and the plectrum in the right, just like the statue of Anacreon, which, incidentally was found in the same Roman villa at Rieti. But while the Classical statue's physique and contrapposto stance conform fully to the standard citizen image of the Periclean age, the old singer is presented to us as an awe-inspiring figure from the distant past. He sits on a tall throne with mighty lion-paw feet and has a thick, old-fashioned cloak of matted wool draped about his hips. He wears a luxuriant beard that is utterly different from the contemporary fashion. His powerful build implies that in his youth he was a tough opponent, while the slack limbs and the creases in the chest and belly are striking reminders of his advanced age.

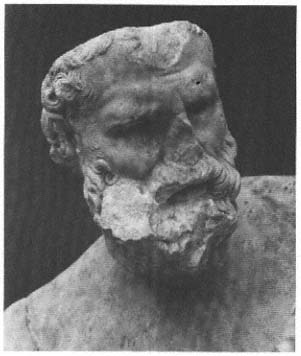

But old age has not stilled the singer's energy and passion. He has sung himself into a state of ecstasy, his entire body seized by the enthusiasm with which he strikes his stringed instrument. His feet are intertwined, as if they had to brace themselves against the surge of energy and prevent the old man from leaping up. The upper body, with the instrument, curves like a spiral to the right, but the head, in its passionate movement, is turned away from the viewer. The singer is completely caught up in his song, enthralled by the instrument and oblivious of the world around him. To judge by the excited expression of his face, the verses he recites have a contentious tone. His inlaid eyes, now gone, must have considerably heightened the pathos of the expression.

A certain identification of the singer is not possible; Pindar and Archilochus have been suggested. What is certain is that the artist meant to represent a specific poet. The detailed characterization presupposes a viewer who was able to infer an association between the portrait and the poetry or the life of the poet. The viewer would have made such observations as these: it must be a lyric poet of the distant past whose work is highly prized in the present, as indicated by the beard, cloak, and throne; this is a poet of strong temperament who sang contentious songs, lived into old age, and had been very strong as a young man. He must have composed not only hymns and battle songs, but also drinking songs for the symposium. The ancient viewer would have inferred this last element from the ivy wreath, a rare attribute, which is preserved in most of the copies (cf. fig. 4).

Fig. 79 a–b

Statue of an old singer. Roman copy of a statue ca. 200 B.C.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. (79a restored).

Of all the renowned Archaic poets, the one who fits this description best is Alcaeus of Lesbos (ca. 600 B.C. ). He himself speaks in one poem of his "greying breast," and we know how passionate and contentious he remained well into old age.[2] The severe and serious Pindar, with his mighty kithara, was imagined very differently in this same period, as we can see in the majestic enthroned statue that stood in an exedra in the sanctuary of Serapis in Memphis.[3] It follows from these observations that we have here most likely a "character portrait" reconstructed from the subject's poetry and what was known of his biography. A retrospective portrait of this kind can have been created only in an environment where there were people familiar with poetic traditions who felt a need for such an image and were able to advise the sculptor accordingly. The statue presupposes a viewer who is also a cultivated reader.