Surgical Therapy

The development of heart surgery constitutes one of the most dramatic advances in the health field in this century. During most surgery on the heart today the pumping and oxygenating of the blood is done outside the body by a heart-lung machine. Few operations—resection of the pericardium, closed mitral valvotomy—can be performed on a beating heart with the blood circulating normally. Cardiopulmonary bypass is obligatory in open-heart surgery. There are four requirements for the performance of open-heart surgery: (1) the blood has to be pumped and oxygenated outside the body; (2) the heart cavities have to be empty; (3) the heart motion has to be stopped; (4) when the circulation and heart motion are restarted, the function of the ventricles has to be restored to its preoperative level.

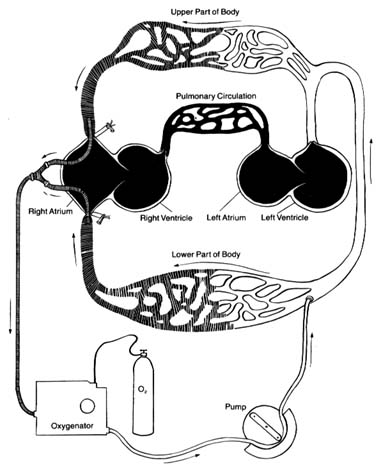

When open-heart surgery was first developed in the 1950s, the task of fulfilling these requirements was indeed formidable. The pump-oxygenator was a highly complex apparatus; several units of blood were needed to start the procedure; and the rate of complications from the artificial perfusion alone was considerable. Since then technology has greatly simplified cardiopulmonary bypass. A simple pump-oxygenator services blood circulating outside the body in disposable tubes and containers (fig. 21). The heart is stopped by injecting into it a solution containing a combination of electrolytes (potassium is a major component). In addition, the heart is cooled so as to reduce its oxygen requirements (hypothermia). Present techniques attain almost perfect preservation of heart muscle function. Cardiopulmonary bypass surgery lasts from one to twelve hours, with some increase in risk in the longer operations. Although surgical results are usually related to the skill and experience of the cardiovascular surgeon, the overall success of the operation is greatly influenced by the contributions of the entire cardiac surgical team of physicians, nurses, and technicians, whose responsibility is to prepare the patient for surgery, administer general anesthesia, supervise the perfusion of blood during cardiopulmonary bypass, and attend to postoperative care.

The overall risk of heart operations varies widely. Several studies have shown that institutions performing a high number of operations are likely to have lower surgical mortality than other institutions.

Commonly performed heart operations include coronary bypass

Figure 21. The artificial circulation used during open-heart surgery (cardiopulmonary bypass,

using a heart-lung machine). Venous (deoxygenated) blood is shown by shaded areas,

oxygenated blood by white areas. Sections of the circulation shown in black represent the

areas bypassed by the artificial circuit and void of blood, which can be opened for repair.

All the blood returning from the superior and inferior venae cavae is drained and channeled

through an oxygenator to be pumped into the arterial system. The blood is prevented

from reentering the heart by the closed aortic valve.

surgery, repair or replacement of heart valves, and correction of congenital malformations of the heart. Coronary bypass is now the most frequently performed major operation in the United States. Even though it does not require opening the heart chambers, the delicate suturing of the arteries has to be performed on a still heart.

Cardiac transplantation has now become a common operation. Its introduction in 1967 was followed by disillusionment because of the low survival rate. However, the development of effective drugs preventing rejection of the transplanted heart has successfully established this procedure, with the majority of patients surviving at least five years. The surgery itself is relatively simple, but the complexity of the overall subsequent care of transplant recipients limits its performance to a small number of institutions. Furthermore, the number of candidates for cardiac transplantation far exceeds the number of suitable donor hearts.

The artificial heart was widely publicized in the media in the mid-1980s when it was implanted into a few patients. Yet the dismal results and astronomical costs made it totally impractical. Some experts doubt whether it will ever become a viable form of treatment. However, a simple mechanical pump assuming the function of one or both ventricles has been used with some success as a temporary bridge when the heart fails totally, until a donor for cardiac transplantation becomes available.