Chapter Two—

Palace Hotels and Social Opulence

In her 1913 novel, The Custom of the Country , Edith Wharton created the Spragg family of the Hotel Stentorian. The Spraggs—a wealthy midwestern industrialist, his wife, and their spoiled daughter, Undine—had moved to New York City to find Undine an eligible mate. For Wharton, the Spraggs were the typical "rich helpless family, stranded in lonely splendor" in sumptuous West Side hotels with names like the Olympian, the Incandescent, and the Ormolu.[1] In time Wharton allows the Spraggs to accomplish their matrimonial goal, helped by the social position and the acquaintances made possible by their hotel home. Up until the 1950s, people like the Spraggs and homes like their expensive New York hotel were common to the writers of popular fiction and society columns. Although both cheap and expensive hotels were tools for creating class distinction and social stratification, palace hotels displayed that role most blatantly (fig. 2.1).

Personal Ease and Instant Social Position

In 1836, just before the famous Astor House opened in New York, Horace Greeley's New Yorker said, "We hear that half the rooms are already engaged by families who give up housekeeping on account of the present enormous rents of the city."[2] In 1926, when the Mark

Figure 2.1

The Plaza Hotel, New York City, opened in 1907 on a dramatic site

overlooking Fifth Avenue mansions and the corner of Central Park.

It epitomized the social and practical advantages of palace-rank hotel life.

Hopkins opened in San Francisco, high rents for private houses and the social prestige of hotel life were still attracting permanent hotel guests in high numbers. On opening, half of the Mark Hopkins rooms had been leased by permanent guests. At palace hotels the truly wealthy enjoyed perfected personal service, superior dining, sociability as well as privacy, physical luxury, and instant status—all at a cost lower than keeping a mansion or large house. Through palace hotel life, nouveaux riches could buy reliable entry to high society; similarly, through hotel life those already at social pinnacles could maintain their position.

Convenient Luxury

At the most practical level, wealthy people loved hotel life because it eliminated the routine responsibilities of managing a large house and garden, devising details for the constant round of dinner parties and elaborate family meals, and supervising an often un-

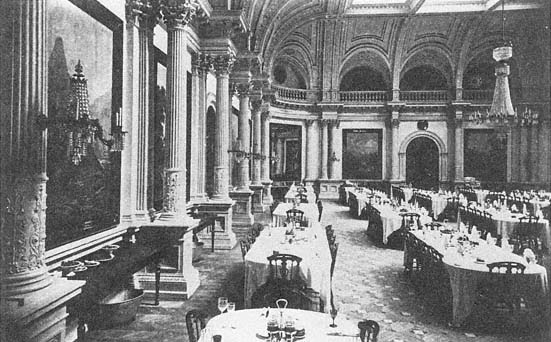

Figure 2.2

The dining room of the Lick House in San Francisco, built in 1861. Until the 1940s, dining areas remained

the chief social vortex of palace hotel life.

ruly staff of servants. Beginning in the 1870s, middle and upper class Americans in private houses (especially the women of the houses) complained regularly about the "servant problem." The available servants were ill-trained, prone to move often, expensive, and not nearly so docile as servants in England. From the 1890s to 1920, the problems increased as immigration brought fewer domestic workers from northern Europe. In the face of these problems, hotels promised perfected service 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. "A suite at the luxurious Westward Ho! will solve all your housekeeping problems," chirped a typical hotel advertisement in the decade before World War I. "We're glad to do your hiring and firing."[3]

Hotel life also offered a gregarious existence not possible in private houses. Grand hotels were built for crowds, and hotel life was spectacularly and notoriously public. In an expensive hotel, barrooms concentrated political and business life; dining rooms, social life.[4] San Francisco's Lick House featured a dining room one hundred feet on a side; the long tables could seat four hundred people amid decor modeled after the dining hall of Versailles (fig. 2.2). The dining room of a palace hotel usually outshone all the other public spaces except the lobby. Before the Civil War, servants sounded great gongs to announce

Figure 2.3

Dinner menu from the exclusive Royal Poinciana Hotel in Palm

Beach, Florida, 1900.

the beginning of the serving hours, which extended for several hours for each meal. Guests walked in during the first half hour, sat down with other people at unreserved tables, and ordered dishes from the day's long bill of fare (fig. 2.3). The American plan of hotel pricing combined room costs and four meals a day into a single daily price. As late as 1910, most of the best hotels were strictly on the American plan.[5]

Astute observers explained the popularity of hotel dining—and hotel living in general—as a manifestation of a peculiarly sociable and gregarious American spirit. In England during the mid-nineteenth century, upper-class hotel guests usually ate alone in private hotel dining rooms. In 1844, when a New York hotel offered this service for the first time in the United States, a local editor objected to the idea as "directly opposed to American ideals of democracy." The public experiences in hotel dining rooms and drawing rooms, he continued, were the "tangible

republic"; "going to the Astor and dining with two hundred well-dressed people and sitting in a splendid drawing room with plenty of company" were major charms of urban life. He warned that private dining in hotels "engendered the spread of dangerous blue-blood habits."[6]

The convenience and sociability of hotel dining aside, pre-Civil War cooking in palace hotels was not always inviting. After spending most of 1862 in America's elegant hotels, the English writer Anthony Trollope praised the vast quantities and types of food served but dreaded the sight of the "horrid little oval dishes" in which all the food swam in grease.[7] After the Civil War, palace hotel managers increased the use of fine cooking to distinguish their hostelries. They imported the best chefs, offered elaborate and exotic menus, and initiated more socially stratified seating procedures in their dining rooms. After 1870, new guests had to know the maître d' (or buy his attention) to get a prominent table, and the tables were no longer of mixed parties. In most cities by 1900, three of the top five restaurants were sure to be in palace hotels, and the creative cookery and inventive bar drinks of the era often emanated from hotel chefs or hotel barkeepers. Parker House rolls, Waldorf salad, Maxwell House coffee, and the Manhattan cocktail all gained their names from hotels. The importance of dining in the company of an elegant crowd and fine food continued into the twentieth century, although elite Americans were building more privacy and class separation into their environments (fig. 2.4). In the 1930s, for instance, a group of New York millionaire investors wanted to have residential suites in a hotel whose restaurant would match the quality of chef Charles Pierre's Park Avenue restaurant. They backed the chef in building the forty-two-story Hotel Pierre.[8]

As Wharton's Spragg family found, palace hotels offered their greatest advantage in the commercialized and nearly instant social position they conferred on their residents. Tenants at palace hotels bought status rather than waiting for it to accrue. Hotel life did not require the slow building and furnishing of an expensive house in the correct neighborhood, the gradual building up of a reputation, or the laborious wheedling of one's way into the proper social clubs and dinner circuits. Immediately after moving into a palace hotel, newcomers could begin to observe (and be observed by) the local elite. The revelry of upper-class dances, banquets, and weddings provided still more social stimu-

Figure 2.4

The Old Poodle Dog Restaurant in San Francisco, an elegant restaurant that competed with palace hotel

dining before 1920.

lation and opportunity. "The pleasantest parties in the world are given at the Lick House," wrote Mark Twain in 1864, further noting that scarcely any save the guests of the establishment were invited.[9] For over a hundred years, hotel advertisers reminded readers that their ballrooms were the scene of particular "invitational dances of the inner circle of society," or they featured photographs of their entertaining rooms to emphasize the hotel's central position in society rituals.[10]

Although the public rooms of a hotel harbored a gregarious life, once residents left the ground floor they could arrange for absolute privacy. As one guest put it, "One of the great joys of being in a hotel" was "to be alone and to be left alone."[11] Desk clerks screened visitors, salesmen, community fund solicitors, and journalists. The service hallways allowed politicians or stage personalities to evade public contact. The better the hotel, the heavier were its walls and draperies and the better the acoustical isolation of its rooms. The selectivity of hotel privacy was its advantage over other private realms. One could intersperse days or hours of seclusion with the conviviality of the dining room, lobby, bar, or downtown theater, gymnasium, or club. "A distinguished literary person can be as isolated in a hotel room as in a cabin in the north woods," wrote one observer, "and yet meet and talk with people at will." At some points in their careers, he added, many prominent busi-

ness people, scientists, artists, writers, and editors relied on hotel seclusion to meet deadlines in their work.[12]

For the very wealthy, a handsome suite in the best hotel cost only a fraction of the price for maintaining a mansion or large private house with comparable amenities. In 1870 in one of San Francisco's five best hotels, a suite of rooms and food cost about $1,000 a year, or $19 a week.[13] By the 1920s, the peak decade for living in hotels, a single room and bath cost from $100 to $230 a month for rent only. Special service and food were available for additional fees. (The usual palace resident rented at least a two-room suite; the single-room price is given here for comparison with other hotel types.)[14] These prices, too, were considerably less than the cost of keeping up a large house with servants (See table 2, Appendix).[15] The generally expanding and volatile business climate of the United States generated both the incomes that paid these costs and also the people who chose hotel life.

Wealthy Hotel Dwellers

In palace hotel life, one most often met first-or second-generation wealth—newly successful entrepreneurs in retail, investment, industrial, or mining enterprises. In Chicago's Sherman House in the 1850s lived Marshall Field's partner Levi Z. Leiter and Potter Palmer. Two prominent tenants in an 1869 apartment hotel in Boston were Major and Mrs. Henry Lee Higginson. Major Higginson was a prominent banker as well as the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In 1874, he moved to his own apartment hotel, the Hotel Agassiz.[16] The families of many of the 1870s leaders of San Francisco's Merchant's Exchange lived in hotels; the exchange was the center of western America's business life.

Predictably, the social groups living at different hotels developed distinct reputations. The eccentric San Francisco philanthropist James Lick, a piano manufacturer who made a fortune in real estate, built the Lick House that later intrigued Twain. In the 1860s, Lick declined to decorate his hotel with the usual buxom female nudes and instead displayed cartloads of tranquil mountain scenes by Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Hill. Thereby, he helped establish the Lick House as the city's preeminently proper family hotel, the home of the "Lick House set." Lick lived out his years at his own elegant hotel, adding his personal reputation and presence to attract others of his economic rank.[17] By the 1890s, the highest prestige in San Francisco had shifted from the Lick

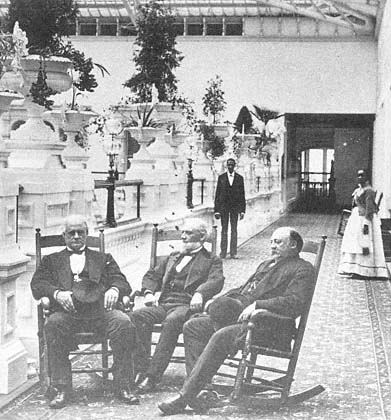

Figure 2.5

Lloyd Tevis, president of Wells Fargo Bank, with friends and servants on the

top floor of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, ca. 1880.

House to the Palace Hotel. Dozens of California's leading families filled the suites on the top two floors of the hotel, including former Governor Leland Stanford, the president of Wells Fargo Bank, and the editor of one of the city's foremost newspapers and his wife (fig. 2.5). After 1910, the residents of the St. Francis Hotel developed a reputation for being the fashion setters and high rollers, while the Palace residents became known as the more traditional and respectable group.[18]

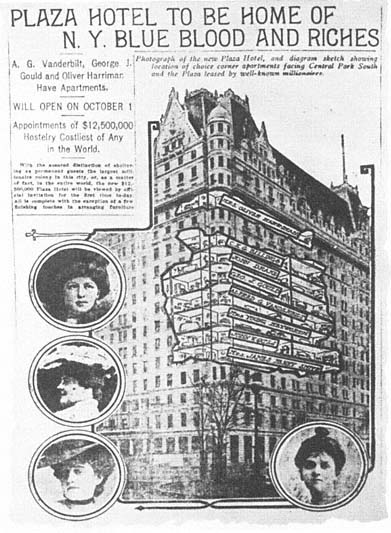

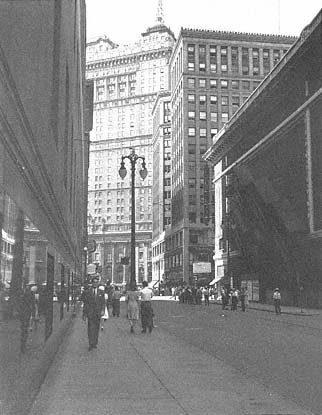

So many business leaders lived in hotels that some developed appropriate corporate legends. In New York City, John W. Gates hammered together the organization of U.S. Steel in his suite at the old Waldorf-Astoria, where he was one of the first permanent guests. James R. Keene, Charles M. Schwab, and other top Carnegie associates also lived at the old Waldorf. When the new Plaza Hotel opened in 1907, the New York Times printed a cutaway diagram of the hotel, revealing the corner suites of the most prominent residents, representing among them many of America's most famous fortunes (fig. 2.6). John Gates

Figure 2.6

Newspaper diagram of the Plaza Hotel, 1907. Published just before the

hotel opened, this cutaway view shows where the wealthiest families

were to live.

and his wife were on the list, along with Mr. and Mrs. George J. Gould, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred G. Vanderbilt, and Mrs. Oliver Harriman.[19]

These most famous and wealthy hotel tenants probably moved to hotels largely for convenience. However, every famous and influential hotel resident attracted a dozen other people like the Spraggs, people who needed to know and be seen with the dominant social group of the city and nation. Indeed, the palace hotel was an important residential counterpart to the increasingly national and closely linked social group leading American business. The rapidly expanding size of corporations and the sheer number of large business organizations after 1900 meant a marked expansion in the number of highly paid and

fairly mobile white-collar employees. Developers made ample provisions in the new palace hotels for this infusion of investors, lawyers, bankers, brokers, financial analysts, and other professionals looking for expensive residential hotel rooms. In 1910, for instance, Tessie Fair Oelrichs, the daughter of the mining king James Fair, completed the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. On opening, half of the rooms were reserved for permanent guests who needed a downtown pied-à-terre. This level of demand was repeated sixteen years later when the Mark Hopkins opened directly across the street from the Fairmont.[20]

Hotel Children

Since married couples (particularly young married couples) often lived in palace hotels, children were a prominent part of residential hotel life, especially in the nineteenth century. The wealthier the young family (with either one parent or both parents present), the more likely they were to have children with them. In 1880, 114 out of the 225 permanent guests in the Lick House were families: 15 married couples with no children, 12 couples with one child, and 9 families with two or more children. One family had five children.[21] When Twain lived at the Lick House, he learned to detest the younger children there, and he explained his judgment by describing a typical afternoon as he tried to work in his room:

Here come those young savages again—those noisy and inevitable children. God be with them!—or they with him, rather, if it be not asking too much. . . . I know there are not more than 30 or 40 of them, yet they are under no sort of discipline, and they make noise enough for a thousand. . . . They assault my works [the door to his room]—they try to carry my position by storm—they finally draw off with boisterous cheers, to harass a handful of skirmishes thrown out by the enemy—a bevy of chambermaids.[22]

In Twain's account, the chambermaids abandon their brooms. The children, still without supervision, ride the brooms as horses and return to taunt the author. Next they attack a Chinese laundryman, steal his basket, and pull his queue. Finally, the children's nurses arrive and drag them off, to Twain's relief.

Twain was hardly alone in his exasperation. "Close and frequent acquaintance with small juveniles in an American hotel," wrote the London journalist George Augustus Sala in 1879, "is apt to induce the conviction that, all things considered, you would like the American child

best in a pie."[23] Victorian hotel rules expressly prohibited the conversion of corridors into playgrounds, but besides the children's dining room, youngsters had few other places to go. In the 1890s, in keeping with new attitudes about children's spaces in American homes, the managers of large hotels began to install kindergartens, playrooms, special classes, and other organized children's programs. The huge McAlpin Hotel in New York had an entire floor set aside for women and children—for both transient and permanent guests.[24]

By the late 1920s, with the greater expansion of apartment living and suburban housing options, the demand for raising children in hotels declined. Only a few palace hotels had so many young children, and some allowed no young children at all. In 1929, for instance, all the 160 permanent residents of San Francisco's Canterbury Hotel were listed in the social register. There were 94 single people (single women outnumbering single men by about 4 to 1), 27 couples with no children, and only 6 families with children.[25] Yet in 1955, Kay Thompson could still choose New York's Plaza Hotel as the setting for a children's book with a rambunctious heroine named Eloise who terrorizes the lobby, elevators, empty meeting rooms, and corridors. Eloise epitomizes the pampered, privileged, upper-class hotel child: she is six years old, with a tutor who goes to Andover, a full-time English nanny, and precocious knowledge of how to order anything she wants from room service. She also divulges that her mother is thirty years old, has a charge account at Bergdorf's, knows the hotel owner ("and Coco Chanel and a dean at Andover, too"), and travels a great deal.[26] At age six, Eloise is well entrained in an upper-class trajectory, and her mother is apparently maintaining her own class status as well.

Edmund White gives a less glowing account of growing up in a "luxury hotel, sedate and respectable," at about the same time as Eloise. White's mother apparently chose the best possible hotel to meet the kind of new husband who could improve her shaky financial status. She could afford only one room with twin beds; White and his sister took turns sleeping on the floor. His mother was gone most of the time, and on cold days the children morosely hung around the hotel, picking fights with each other and eating at different times to avoid each other in the dining room. White discovered an accessible parapet off the empty ballroom and spent hours there, reading.[27]

Especially after 1930, hotel children like Eloise and White had few playmates because outside children were afraid of hotels. For adventure and companionship hotel children often tagged along with the chambermaids and bellboys on their rounds, learning all the inside gossip about the guests. Conscientious mothers complained that they had more child-care responsibilities in hotels compared to houses, because in hotels it was harder to keep children happy.[28] Indeed, the hotel emphasized adult social needs, in contrast to the child-centered suburban environment.

The children in hotels may not have cared much about architectural opulence, but adult hotel residents certainly did. Like the commercial sociability and other personal advantages of hotel life, architectural luxury and geographic prominence of palace hotels were important attributes for the class formation aspects of expensive hotel life.

Incubators for a Mobile High Society

Multiple architectural advantages favored public hotels over private houses as social incubators. Few private houses could guarantee more than a fashionable address or a local architectural prominence. Palace hotel life, however, enveloped residents in an international network of architectural distinction. By definition, a palace hotel required a building of world prominence and a series of interior public locations—the lobby, the bar, the dining room, the ballroom, the terrace—that were known to virtually everyone in the city (at least everyone in polite society) and that were generally accessible only to the truly elite. Palace hotel opulence—no matter who the architect, owner, or manager—was not only an individual achievement, but also a social fact. Until their prominence was replaced by office buildings in the 1890s, hotels were often the city's most important landmarks. And unlike city halls or office buildings, one could live in these landmarks. The development of these architectural realms paralleled the historical development of the palace hotel as a social institution.

Early Developments:

The First-Class Hotel

The architectural development of the palace hotel was a story of ever-increasing specialization and separation. Wealthy members of the business elite, very much like

the fictional Spraggs, began to live permanently in hotels in about 1800, at the same time that the best hotel buildings began to be more than mere inns. American inns and taverns in the 1700s looked much like large single-family houses. Not until the late 1700s did grand architecture or elegance grace travelers' lodgings in Europe or America; simultaneously, the word hotel (in English) came to denote inns of a superior kind.[29] Between 1790 and 1820, associations of wealthy businessmen in the United States improved on English hotels by building structures with elaborate public spaces as well as a totally new scale of 70 to 300 very simple sleeping rooms. In Boston's 300-room Exchange Hotel, opened in 1809, putting numbers on the room doors was enough of a novelty to merit mention in travelers' accounts.[30] After 1820, American hotel investors outbuilt structures like the Exchange Hotel and essentially invented the world model for the large modern hotel. Simultaneously, they added a new level of luxury and a more private life in personal rooms. Providing each room with an individual washbowl, water pitcher, and soap at first distinguished these hotels. Significantly, it was in this generation of expensive hotels that permanent guests first gained a high profile. English travelers in America frequently complained that they could not get the good rooms they wanted because the best accommodations were occupied by permanent boarders—judges, lawyers, merchants, and others who brought their families to live in the hotel.[31]

Most American inns and hotels before the 1820s had mixed people from somewhat disparate backgrounds, to the chagrin of those European travelers who were both fastidious and wealthy. The opening of Boston's Tremont House in 1829 signaled new and more socially restrictive management ideas for the United States. The Tremont had only one room rate—a high one for its time—of $2 a day for room and board. For permanent residents, it offered elegantly furnished private parlors attached to suites of rooms. As part of their rent, Tremont tenants enjoyed lavish hotel service that included the first bellboys and the first hotel dining room in the United States to feature French cuisine. The managers and the architect of the Tremont also analyzed functions that had been crowded into earlier hotel rotundas and separated them into four spaces—lobby, desk or office, baggage room, and bar. The Tremont was thus one of the first hotels where guests went into a lobby

Figure 2.7

An 1895 view of the Astor House in New York, built in 1836. This panoramic view shows the venerable

hotel and St. Paul's Chapel at the corner of Broadway and Vesey Street. The fire escapes were a late

addition.

to register instead of going into the bar. It was also one of the first hotels with truly private rooms: each room had a separate key, and strangers were not sent to share rooms. (As late as the 1860s, in cheaper hotels rooms were still shared by strangers when necessary.)[32] By 1840, urban Americans were using the term "first-class hotel" to distinguish the very best hotels. With at least one hundred rooms, imposing architectural style, luxurious service and food, and often a famous manager, first-class hotels became an urban social center for the elite, a place to do business, and—for some—a place to live (fig. 2.7). High prices kept out most middle-income residents, except those who stayed for a few days as transient guests.

Like the shift represented by the Tremont House and its followers, shifts in hotel sizes and styles coincided with periods of national economic development. The big inns like the Exchange Hotel came to life in the 1790s with the beginnings of a distinctly American economy and a more reliable system of stagecoach travel. The first-class hotels of the 1820s and 1830s followed another surge of business expansion, land sales, urban population growth, shipping, canal building, and turnpike construction. An imposing hotel became an essential ingredient for any aspiring city in the battle to attract new capital investors and professionals. Emulating the chartered companies of wealthy merchants in established cities, boosters on the urban frontier built ever-larger and more imposing hotels in each generation.[33] Boosters often overbuilt; to fill the rooms, the managers of grand new hotels often had to offer attractive rates to permanent residents. By the 1860s, the transformation

of the economy, availability of larger capital investments, perfection of new management practices, and use of passenger elevators and steel frame construction made even larger hotels feasible. These changes also made necessary a more distinctive architectural and social category of hotel.

Palace Hotels

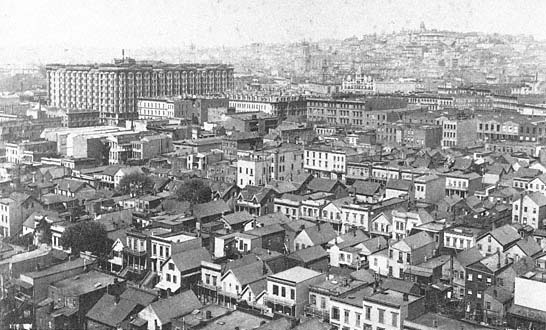

After the Civil War, new hotels—some of them with only middle-income dining and service—jumped to a size of 500 and 700 rooms. By the 1880s, dozens of hotels in any large city could boast "first-class" amenities; the term had come to mean merely a good hotel rather than a socially exclusive hostelry. To distinguish the one to five most elite hotels in the region, citizens began to speak of palace hotels—hostelries that maintained the pinnacles of price, luxury, fine food, social prominence, and architectural landmark status.[34] The heyday of residential life in palace hotels occurred between 1880 and 1945. In name as well as in experience, the Palace Hotel of San Francisco exemplified the type for the Victorian era. The $5 million hotel opened in 1875 and covered an entire city block. Its two prominent owners—the state's most audacious capitalist and a wealthy U.S. senator—set its social status. It had 755 rooms in seven stories arranged around a large central courtyard with a skylight and two additional very large air wells. For the next thirty years, the Palace reigned as a landmark. Its massive seven-story volume loomed over the city, and its hundreds of bay windows dominated downtown vistas (fig. 2.8).[35]

The sumptuousness of a palace hotel suite was recorded in 1879, when Sala enthusiastically listed the furnishings of his $4-a-day "alcove bedroom" at the 400-room Grand Pacific in Chicago:

Height at least 15 feet; two immense plate-glass windows; beautifully frescoed ceiling; couch, easy chairs, rocking chairs, foot stools in profusion, covered with crimson velvet; large writing table for gentlemen, pretty escritoire for lady; two towering cheval glasses; handsomely carved wardrobe and dressing table; commanding pier-glass over mantelpiece; adjoining bath-room beautifully fitted; rich carpet; and finally the bed, in a deep alcove, impenetrably screened from the visitor's gaze by elegant lace curtains.[36]

Sala concluded that there was no more splendid hotel in the world than the Grand, although he said something similar about almost every pal-

Figure 2.8

San Francisco's Palace Hotel, as seen from the South of Market district, ca. 1890. The hotel, at rear left,

was a Victorian era landmark in every sense of the term.

ace hotel he visited. From 1820 through the 1940s, suites of two or more rooms remained part of the standard plan of all large hotels. Many were typically occupied by permanent guests.[37]

The elegance, comfort, and convenience of palace hotel life relied not only on food and architecture but also on the level of human and mechanical service. Like ocean liners, some palace hotels employed as many as four or five staff for each guest; ratios of one employee to one guest, or three to two, were the minimum for a palace hotel. In 1990, the twenty to thirty most expensive hotels in the United States were still distinguished by lavish hospitality and an extremely high level of personalized service.[38] Only a small fraction of the hotel personnel were publicly visible as clerks, bellboys, elevator operators, or waitresses. The rest worked in what Sinclair Lewis called (in 1935) "the world behind the green baize doors at the ends of the corridors." There one found industrial-scale machinery that could heat and air-condition thousands of rooms, provide instant hot water, and launder thousands of napkins and sheets. There were large shops for upholsterers, carpenters, and plumbers, along with tailors, printers, florists, and a dozen other trades and specialties.[39] Indeed, in any period after 1880, the gen-

Figure 2.9

Palace hotel as landmark: the Book Cadillac Hotel in

downtown Detroit. Photographed in 1942.

eral manager of a palace hotel hired, trained, and supervised a staff of thousands. At peak seasons and for special events, the manager routinely employed by the day hundreds of additional helpers.

In 1893, when the owners joined the 10-story Waldorf Hotel and its adjoining 16-story Astoria Hotel to create the original Waldorf-Astoria, they set a 1,000-room pace for the new post-Victorian generation of palace hotels. In 1907, the 18-story Plaza Hotel at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Central Park South easily surpassed the Waldorf-Astoria as New York's leading palace hotel.[40] In the next fifteen years, palace hotels elsewhere—for instance, the Book Cadillac in Detroit and the 500-room Drake Hotel on Chicago's Lake Shore Drive—set sparer architectural styles but changed little else (fig. 2.9). On the upper floors of such hotels a few wealthy families often built 10- to 30-room penthouse suites. A case in point is a 1913 hotel home built by a shipping and lumber baron at the top of San Francisco's St. Francis Hotel. He leased two entire floors, one for his family and one for the servants. The

entertaining rooms of the family's suite survive today as part of San Francisco's City Club.

Builders of the next generation of palace hotels, beginning in the mid-1920s, added parking garages and true skyscraper towers but offered smaller guest rooms. Hotels like San Francisco's Sir Francis Drake prominently advertised their built-in garage, with elevator service direct from the garage to guest room floors. The typical bedrooms in late Victorian palace hotels had been 20 feet by 20 feet, offering twice the floor area of rooms in fine hotels built in the 1920s. The palace hotel rooms of the 1920s were still elegantly furnished—but no longer with brocades, fringes, and ornamental brass.[41] Outside, a tower of 18 to 30 stories, in Art Deco architectural style, was almost essential. Managers experimented with penthouse dining rooms; with the end of Prohibition, they added flamboyant bars to the tops of their hotels. Radio stations or at least radio programs originating in palace hotels became another way for hotels to retain their prominence.[42] In 1930, the new Waldorf-Astoria leapfrogged the Plaza in size but never regained its social hegemony because the Waldorf was simply too large. Three hundred of the new 2,253 guest rooms had parlors, but true palace hotel status accrued only to the Waldorf Towers section, which had its own entrance and 500 deluxe suites with 18-foot ceilings, open fireplaces, 45-foot by 25-foot drawing rooms, and 14-foot by 18-foot bath-dressing rooms. In the 1980s, rents for such a suite could range from $5,000 to $8,000 a month. The Waldorf Towers attracted many world-famous people as residents, including Herbert Hoover (who lived there from 1934 to 1964), General Douglas MacArthur (1951 – 1964), Henry Kissinger, and former President Gerald Ford.[43]

Permanent residents retained a prominent part in palace hotels up to the early 1960s, and some palace hotels still had permanent residents in 1990.[44] A San Francisco journalist's survey in 1983 found fifteen residents, including Cyril Magnin at the Mark Hopkins, living in three of the city's palace hotels, still echoing the advantages listed by generations of palace hotel dwellers. Ruth Fennimore, at ninety-one years of age, had worked hard to return to hotel life. She and her husband had lived in a palace hotel for a year after their marriage in 1912. In 1973, some time after her husband died (he had been a prominent optician and president of the Retail Merchants Association), Mrs. Fennimore moved back into a hotel. For her one-bedroom apartment, the rent was

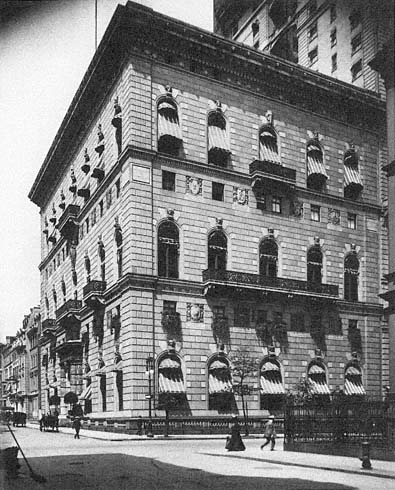

Figure 2.10

The University Club in New York. A classic example of an elite

residential club, it contrasts sharply with the houses to the left.

more than $3,000 a month, but that included what she called "perfected service." She and the other residents visited back and forth just as suburban neighbors did. Another resident confessed, "You know, when you're 86, most of your friends are in the cemetery. The Huntington is my family, from the lowest housekeeper to the manager."[45] San Francisco's permanent palace hotel residents were mostly elderly, although the families of three corporation presidents also kept suites at the Huntington. In other cities, hotel life at the palace level has depended more on the whim of hotel managers than on the demand; only a few managers are willing to take permanent residents. New York City remains the capital of palace hotel living.

If single men or single women were of upper-class social status but did not want to live the relatively public life of a palace hotel, they

might have chosen life in an elite private club (fig. 2.10). Each city had its own top clubs, but usually an expensive club's exclusivity, its quiet and dignified buildings, reasonably good food, and social contacts made residence there a substitute for palace hotel life. For many, clubs were an improvement on hotel life. Because club members carefully chose their companions, life in a club was guaranteed to be more exclusive than life in a hotel, which accepted almost anyone who could pay. Living at a private club was also a prime option for elderly men and women of high status but lowered spending capacity, since living in elite clubs could often cost less than living in posh commercial hostelries.

Cycles of Life at Palace Hotels

On a day-to-day basis, the visible signs of achieving and maintaining membership in upper-class hotel life seemed to consist of wearing stylish clothes and following other avenues of conspicuous consumption as social competition strategies. One hotel resident of the 1920s, disgruntled with the system of buying one's status, complained to an interviewer about the hidden expenses of hotel life:

In order to be recognized as an admirable person, you need a constant shower of money to the help, expensive and very up-to-date clothes, and one must entertain at dinner, play cards, order motors [motorcars], and rush about to theaters and parties.[46]

Another guest, who could afford the expenses and enjoyed hotel life, admitted that the only possible drawback in comparison to life in a private house or apartment was that one had to "constantly be dressed up."[47] Extravagant and stylish clothes did mean a great deal in the palace hotel world. The vast marble-columned lobbies and dining rooms set suitable stages for the daily parade of wealth. Society columnists regularly reserved space to cover hotel visitors and entertainments. Hotel residents helped to redefine a city's social ranks by showing the new canons of consumption and its essential public display; such people had money to spend and the need to display it, as Thorstein Veblen explained. In 1875, Countess Maria Yelverton presaged Veblen as she rather jaundicedly noted that palace hotels permitted the wealthy "to display their riches to the greatest advantage, and make as much show as possible for their money."[48] In 1920, a Chicago society reporter ob-

served the continuity of tradition as she reported that women could give inexpensive parties, "amounting to no more than afternoon tea," followed by a grand announcement in the newspaper that "Mrs. So-and-So entertained 50 guests at luncheon at the Plaza Hotel, the company afterwards playing bridge."[49]

The displays of wealth and the system of "social-position-for-cash-and-appearance" also had unwanted side effects. The instant status conferred by proper clothes, manners, and spending money meant that intelligent thieves could efficiently establish an assumed identity at a hotel, deftly meet officers and employees of large firms, and then extract precise tips about their payrolls and company deliveries. The rich, feeling that they were in a protected environment, inadvertently advertised their enticing jewelry in the lobbies and dining rooms. Hotel people of high social standing were also easy targets for blackmail.[50]

Outnumbering the outright thieves in hotel life were the professional gamblers. Porters quite rightfully described palace and midpriced hotels as the "worst gambling places in the world"; in the 1920s, staff reported that when they took men's bags to a room, one of the more frequent inquiries was, "Say, can you lead me to a little game?"[51] San Francisco's Palace Hotel had many small "committee rooms" devoted largely to card games for large stakes. Women, too, joined the hotel ranks of professional cardsharpers and gamblers. At one palace hotel in the 1920s, an attractive and well-mannered woman met three other women residents. Over a period of days she invited them to her suite for competitive games of bridge and a week later, made off with $9,000 from her victims, who were obviously fond of playing cards for high stakes.[52]

Prostitutes—both men and women but most commonly women—were another socially marginal group who lived and worked in all ranks of hotels, including palace hotels. Hotels were also notoriously convenient places for men to keep mistresses or for women to keep paramours. As late as the 1890s, hotel managers barred single women from registering and staying alone for fear they would be prostitutes and damage the respectability of a proper hotel.[53] Into the 1950s, comments about and images of "loose women" continued to mix with hotel life. The fact that the phrase "loose men" was not common indicates a cultural double standard more than a more abstinent male population. The presence of thieves, professional gamblers, and prostitutes continu-

ally proved that even the exclusivity of palace hotels was not absolute.

If palace hotel residents were looking for a gaming or sexual or retail venue not available at the hotel, they could avail themselves of the full diversions of the surrounding city. That was true for other services as well. Yet, technically, palace hotels needed their neighborhoods only for a labor supply and deliveries. Hotels of such scale and complexity could conceivably exist with minimal reliance on outside services or independent shops on the surrounding streets. With four or five restaurants, three bars, dozens of shops, and several promenade hallways in the interior of their hotel, palace residents were not forced to walk outside.

The locations of palace hotels, more scattered than midpriced hotels, attested both to their insularity and to the fact that only in a few places of the city could people assemble a single plot of land socially appropriate and large enough for a palace hotel. In San Francisco, these locational directives indicated Union Square (established very early as the retail shopping center of the city) or Nob Hill. At the end of the nineteenth century, Nob Hill was the most prestigious address in the western United States; it was famous as the home of several of California's and the world's richest families. New downtown mansions were still being built not far away. Flamboyant Victorian piles, like the multitowered mansion of Mark Hopkins, were looking like haunted houses; their owners had died or moved, and the children wanted to live elsewhere. Not surprisingly, between 1900 and 1920 (just before and after the great fire of San Francisco), landowners on Nob Hill transformed their properties from an exclusive private neighborhood to the quintessential palace hotel neighborhood, with several parallels to areas like Fifth Avenue in New York and the Gold Coast of Chicago. Nob Hill's real estate developers, often children of the famous families, could see that their sites offered all the necessary neighborhood elements for fashionable hotels, apartments, clubs, and restaurants. In a sense, in replacing the individual private opulence of the Nob Hill mansions, the new palace hotels and clubs helped to create and reinforce elite class position with a more conspicuously social opulence. The optimum stage to display social opulence was at the center of the city, not buried behind shrubbery and trees on a private estate road twenty miles from town.

Nob Hill's location was central, and its transportation was excellent. The best office and retail blocks were within walking distance but not

so close as to bring hoi polloi right to the doors of the hotel. The hill's elevation gave commanding views of the rest of the city and beyond to San Francisco Bay. Several of the city's most expensive boutiques were either inside the hotels or around the block; fine restaurants were close by; the opera house and elite museums were a short cab ride away. The site of the Crocker mansion had become the city's new Episcopal cathedral. (A preponderant share of California's pioneer business families were at least socially Episcopalian). At the top of the hill, a small park gave an urbane and European focus to the district; next to the park was the one remaining prefire mansion in the area, converted into an exclusive men's club. By the 1920s, three palace hotels (the Mark Hopkins, the Fairmont, and the Huntington) and several lavish apartment blocks surrounded the park and club. Although there was no public coercion, virtually no retail stores were visible from the side-walk. The mixture of residential and commercial activity occurred but in hidden and guarded interiors. The only outwardly visible signs for the restaurants were tiny brass plaques; insiders already knew their locations. In the early 1920s, polite hotel districts like these were so accepted and growing so rapidly that utility engineers made plans for 1940 assuming other zones fully occupied by high-class residential hotels. Hotel keepers, too, expected a "Nob Hill/Gold Coast/Fifth Avenue" future for urban residential life.[54]

For social status, leaving a palace hotel and its neighborhood could be as important as being there. Elite downtown living figured as only one phase in an annual cycle of different residences. A hotel suite served as a center city pied-à-terre complementing homes in the country and world tours or business expeditions. So few palace hotel guests stayed at one hotel for the entire year that they were well known among the staff. Wealthy hotel residents moved heavily and ostentatiously from place to place with servants, piles of trunks, valets, and governesses for their children. Some of these shifts of residence were for health reasons: to a resort hotel in Florida, in California, or in the Southwest to avoid the winter; perhaps a trip in the fall to a family house in rural New England; then back to a major city for the opera season, shopping, or business.[55]

Important stops in the annual rounds of residences were a handful of exclusive resort hotels. Compared to downtown palace hotels, upper-class resort hotels were more likely to be sheathed in wood rather

Figure 2.11

Aerial view of the Royal Poinciana Hotel, Palm Beach, Florida. Briefly, the Poinciana was a winter

pinnacle of society.

than marble and horizontally impressive rather than vertically imposing (fig. 2.11). However, the best resort hotels matched the downtown opulence of food, service, and furnishings and added spectacularly beautiful and healthful rural settings and multiple outdoor amusements. The Hotel Del Monte, built in 1880 on a 7,000-acre site at the edge of Monterey, California, offered the requisite amenities: scenic vistas, elegant public rooms, 26 acres of landscaped gardens, a golf course, a polo field, a racetrack, tennis courts, and a 17-mile private carriage road through the Del Monte forests to Pebble Beach and Carmel. Wherever possible, the sites of palace resort hotels included prominent sidings and landings for the conspicuous arrivals of private railroad cars and yachts (fig. 2.12). As Robert Louis Stevenson said in reference to the Del Monte, there one would be sure to find "the millionaire vulgarians of the Big Bonanza."[56]

Like downtown palace hotels, upper-class resort hotels offered a constant round of social entertainments but with a more closed set of participants. Of the vast Royal Poinciana in Palm Beach, which flourished from 1893 to the 1920s, Henry James wrote that "there, as nowhere

Figure 2.12

Group leaving on a private railroad excursion from the Royal Poinciana, March 1896. The group includes

Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, Henry Whitney, Gladys Vanderbilt, and Gertrude Vanderbilt.

else in America, one would find Vanity Fair in full blast . . . compressed under one vast cover." Both men and women had to bring trunkloads of different outfits appropriate for a daily cycle of events that might consist of breakfast, a morning stroll, swimming or boating, lunch, bicycling or carriage riding, golf, tea, an afternoon stroll, a very formal dinner, an evening promenade, and dancing. One dared not repeat an outfit too often during the summer's stay. Because theaters and clubs were not immediately adjacent, the summer resort had to offer lavish entertainment as part of the program.[57] Palace resorts were as expensive as downtown palace hotels. One account cites the cost during the 1890s at Mohonk Mountain House in the Catskills at $125 a week for two parents, a daughter, a maid, and two horses versus $6 to $12 a week per person for modest boardinghouses in the valley for middle-income vacationers.[58]

At palace resorts, dress codes and high prices screened out most people who were economically undesirable, as in downtown palace hotels. But exclusive resorts screened out undesired guests much more overtly than the downtown hostelries. The code word restricted , some-

times seen in advertisements or road signs, meant that Jews, blacks, Asians, or blatantly practicing Catholics (Italians and Irish, especially) would be accepted as servants but not as guests. A few resort hotels advertised all-white kitchen staffs. These restrictions lasted in some resort hotels until World War II.[59] The tightly drawn social circle pointed to a major role for the best resort hotels: because they were so much more insular than downtown hotels, they were the perfect place for the young people of America's elite to meet strictly appropriate people of the opposite sex. Resort hotels also played a recruiting role for hotel residence in the city. While on holiday, summer guests could have their initial conversion experience to the comforts and convenience of more extended hotel life.

Summer vacations notwithstanding, other downtown living options away from a mansion were also appealing to wealthy Americans.

Apartment Alternatives

From the 1880s to the 1930s, neighborhoods like Nob Hill were ideal for expensive apartments as well as palace hotels. Yet even when they stood on the same street corners, hotels retained some advantages over apartments. At best, an exclusive apartment building gave its residents a good address on a fashionable street and perhaps a well-known name. A hotel or apartment hotel, however, could add the reputation of its ballroom, the popularity of its chef, and the notoriously high price of its dining room. Hotels also gave nouveau riche residents more opportunities to show off clothing or packages from expensive stores. In apartment lobbies, no one saw these things.[60] In the 1920s, when most of present-day Nob Hill was completed, a luxury apartment of five to seven rooms might have cost $250—about the same price as a multiroom suite in the Mark Hopkins or the Fairmont but not including the food (see table 2, Appendix).

It is hardly surprising that expensive apartments and expensive hotels like the Mark Hopkins would stand on opposite corners, since the two building types had closely intertwining histories. The fashionable apartment's role in reinforcing social class, its architectural form, its facade styles, and especially its mechanical accoutrements before 1900 owed far more to the American residential hotel than to the distant Parisian flat (fig. 2.13). Nineteenth-century apartments in France mixed people of different economic classes; the higher the floor, the cheaper the rent. In America, the availability of the elevator and the

Figure 2.13

The Hotel Majestic and the Dakota Apartments seen from Central Park in 1894.

In their early development, elegant apartments and residential hotels often

shared location, clientele, and building types.

relative insecurity of social position reinforced the desire to build apartment buildings as class-specific as were new hotels.[61] To keep good tenants happy, apartment promoters had to offer a series of features that tenants had come to expect from their stays in palace hotels: wider air shafts, fast and quiet elevators, "the hottest radiators and the most gleaming plumbing in the world," electricity in all rooms, twenty-four-hour telephone service, and all-night elevator service.[62] The intertwining evolution of hotels and apartments also meant that Americans interchanged words for them as well. The earliest American apartment buildings, aimed at wealthy tenants, usually had "hotel" in their title. Before World War I, journalists interchangeably applied terms such as "French flat," "decker," "hotel," "apartment," "apartment hotel," and "family hotel" in articles about a single building that could have been either a hotel or an apartment building. Not until 1930 did some city directories show a heading of simply "Apartment Buildings" and not a listing of "Apartment Houses (see also Hotels)," linking hotels and apartments.[63]

Conversion Experiences for the New City

Upper-class apartments were like palace hotels in that they were not backdrops for a society already formed, not passive stages for human action. Palace hotels played an active role in shaping the flow of life

through them. Restaurants, polo grounds, barrooms, and ballrooms channeled daily lives and structured social interactions; they helped to form and revise social groups as well as to reinforce them. Simultaneously, hotel spaces helped to shape the social consciousness derived from daily life and were spatial tools often consciously wielded by members (and would-be members) of the elite.[64]

Palace hotels played more civic roles as well, influencing the acceptance of new ideas about the arrangements of domestic and urban space.[65] As architects and hotel managers hammered out the architecture and social relations of the first-class hotel and palace hotel, they showed people a possible future for the city. The jumbled, crowded, mixed-use city of the nineteenth century did relatively little to organize human life officially; downtown urban life remained a seemingly disorderly landscape of confusion, individual competition, and commercial greed. The experience of living in and frequenting palace hotels helped to prepare the urban elite to make decisions about more organized, articulated, and stratified urban space (fig. 2.14). The palace hotel was only one place among several where urban elites from the 1820s to the 1890s experimented with the new organization of space; other venues included the commercial arcade, prison, school, campus, and eventually the great pleasure garden park.[66] However, the palace hotel was especially apt as a scale model of a successful future city. Throughout the nineteenth century, palace hotels were increasingly efficient machines for keeping people of different strata and classes in their place, in a total scheme coordinated by centralized planning and direction. Like the city, hotel life brought several groups of strangers together in large numbers and in close juxtaposition. The hotel was overtly commercial, but because it was a privately managed fiefdom, its public spaces presented a uniform and homogeneous arrangement of space and people. The lobbies, dining halls, and hallways of palace hotels were public only to those people in the upper and middle class whose clothing and decorum passed the unobtrusive inspection of a phalanx of hotel detectives and floor clerks who, if necessary, were ready to quietly interview and eject people who looked out of place.

The palace hotel was also a complete and total scheme for a diverse but centrally planned and coordinated set of activities and spaces. Hotel managers could control potentially competing activities. Architects and managers steadily specialized and separated spatial and social ar-

Figure 2.14

The old city and the new city, 1876. Temporary sheds in the foreground contrast with San Francisco's

Palace Hotel in the background.

rangements. Each space and time, if possible, was increasingly organized for one activity and one social group. Palace hotel buildings provided multiple parlors and dining rooms—some for men, some for women, some for men and women together, some for children, some for transient guests, some for permanent residents. Designers and managers strove mightily to keep invisible the world of the hotel workers—servants' hallways, laundries, kitchens, the entire world beyond the green baize doors. Wherever possible, knowledge of the realms of work (production) was not to overlap with the realms of the residents'

daily life (consumption). In hotels this became possible more quickly, more thoroughly, more socially, and at a much larger scale than in the large private houses or other elite environments of the same periods.

Long before the era of the push button, the commercialized community of the hotel was made to appear automatic, effortless, and socially seamless. No wonder, then, that Henry James wrote, "One is verily tempted to ask if the hotel-spirit may not just be the American spirit most seeking and most finding itself."[67] Many middle and upper class Americans agreed with James. However, most of them probably agreed because they thought he was referring not to a palace hotel but to a more common and more approachable type, hotels best known by people of middle incomes.