Porter Is Demoted

Frank Dyer and other Edison executives screened and approved all completed productions prior to distribution: they were well aware of their films' continued deficiencies. By late February, as Dyer prepared to expand the Kinetograph Department to four production units (three in the Bronx), he concluded that a new head of negative production was needed. On February 26th he accordingly removed the maker of The Great Train Robbery from his position as studio manager. John Pelzer, manager of sales, was temporarily placed in charge of the studio. Porter was sent on a trip to Savannah, Georgia, with James White who had been rehired in December 1908. The reunited makers of Life of an American Fireman filmed A Road to Love; or, Romance of a Yankee Engineer in Central America (March 1909), a film that was "pleasing notwithstanding the apparent carelessness with which it was produced."[86] After his Georgia sojourn, Porter judiciously stayed away from the Bronx studio, making The Doctored Dinner Pail , a comedy trick film in the French style, at East Orange during mid March.

Meanwhile, Dyer had located a new studio chief, his friend Horace G. Plimpton—a carpet dealer.[87] On Saturday March 27th, Wilson announced that Plimpton would become manager of negative production (for $100 a week) and John Pelzer would return to his duties as manager of sales. Edwin Porter would act as photographic expert under Plimpton's direction. Alex T. Moore resigned—or was dismissed. Later characterized by some as lazy, Moore was not needed at Edison and did not continue in film production. A memo was circulated to various departments elaborating on these changes:

3/27/09

TO ALL DEPARTMENTS:

Regarding the attached notice, in order that there may be no conflicting authority between the respective departments, it is to be understood that Mr. Plimpton will have entire charge of and be responsible for the production of all negatives until they are turned over to the Orange factory for printing.

Mr. Porter, acting under Mr. Plimpton's directions, will give such advice regarding negative production and questions relating thereto as his experience may suggest, and

A Road to Love; or, Romance of a Yankee Engineer, made by Porter and White

outside the studio system in March 1909.

will do such other special photographic work as may be possible; and when requested by Mr. Weber, shall investigate and make any recommendations concerning the Orange plant and our machines and output. He will act solely as a consulting and advisory man.

Mr. Pelzer, as Manager of Sales, will confine himself to the selling end of the business, and Mr. Farrell shall act as his assistant. Mr. Jameson [sic ] will be the foreman of the Printing and Developing Plant.

It is hoped that all departments will co-operate cheerfully and in a friendly spirit to advance and improve the quality of Edison pictures.

Frank L. Dyer

Vice-President[88]

Although Dyer and Wilson thus reduced Porter's role to that of consultant, he retained his substantial salary of $75 a week.

Under Horace Plimpton, the Bronx studio continued to expand, and its production procedures were increasingly systematized. A unit-director system with clear lines of authority emerged. In March 1909 Plimpton added a third unit at the Bronx studio, with Maurice George Winterbert St. Loup ($60 per week) as director and Otis M. Gove ($35 per week), who had earlier worked at Biograph, as cameraman.[89] In May, St. Loup was let go, and William F. Haddock ($40 per week) replaced George Harrington at the Twenty-first Street studio. In early June a fourth director, Ashley Miller ($40 per week), and a fourth cameraman,

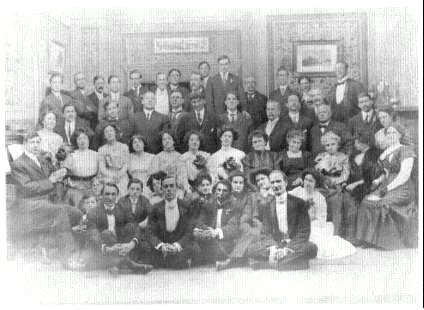

Staff at Edison's Bronx studio, ca. 1909-10. The four directors sit in front

(Ashley Miller on left, Dawley with cigar).

C. L. Gregory ($25 per week), were hired. The number of production units had quadrupled in the space of a year. This was made possible by the enlargement of the Bronx studio, a process begun in 1908 and completed by mid 1909. All regular production was eventually centralized in the Bronx.

During most of his time at Edison, Porter had served simultaneously as cameraman, director, studio manager, film editor, negative developer, and equipment designer. By mid 1909 the Kinetograph Department had developed a highly specialized and hierarchical structure. Under Plimpton were four directors (Dawley, Haddock, Miller, and Matthews) and four cameramen (Cronjager, Armitage, Gove, and Gregory). Plimpton created a camera department headed by Armitage, who coordinated or reassigned such tasks as negative development and editing.[90] It was not until late January 1910 that Edison hired its first film editor—Bert Dawley, J. Searle Dawley's brother. Following Plimpton's arrival, additional actors were hired on a full-time basis, including William Sorelle, Edward Boulden, John Steppling, Herbert E. Bostwick, and Laura Sawyer. The stock company was well established, and the basic elements of the studio system were in place.

Although publicity coming from the MPPCo and the Edison Company continually emphasized the increasing expense of their films, documentation suggests differently. Edison executives kept precise accounts for each film, totaled

the expenses of each director, and compared the results on a monthly basis. The average negative cost varied from $1.28 per foot for Dawley in June 1909 (inflated by the cost of one film, The Prince and the Pauper ) to $.30 per foot for Haddock in October. The average cost per negative foot was $.508 (just over $500 to produce a one-reel film) for June—October 1909, a reduction of 37 percent over the cost of a negative foot for 1906 ($.81).[91] Moreover, the average cost per negative foot declined over the course of the June—October period. By mid 1909 Plimpton had set up rigorous cost controls and other forms of accountability by director. If their units performed poorly either as to production costs or production results, the directors were chastised. If the problem persisted, they were replaced—as Matthews was replaced by Frank McGlynn in August 1909.[92] Despite these efforts to control costs and improve quality, the Edison Company's performance remained disappointing. Although the number of Edison productions increased almost threefold from 1908 to 1909, film sales increased only 22 percent from $554,359 to $675,306. Fewer prints of more subjects were being sold. With film profits remaining virtually unchanged at $234,798, much more energy was being used to attain the same financial results.

The Edison studio was operated like a factory. Creative personnel made templates or negatives of selected subjects as inexpensively as possible. This process involved the highly coordinated efforts of many specialists (actors, set designers, cameramen), who worked with several separate units, each of which was the responsibility of managers (the directors). These unit managers reported to and worked with one head supervisor (Plimpton). The negative was developed and a positive copy of each film was assembled by the camera department (headed by Armitage). The picture was screened for quality control in West Orange by a select group of executives—including, in principle at least, Thomas Edison. Once approved, multiple copies were printed up and assembled according to specification in West Orange by low-paid workers. Clearly the cinema had undergone a radical transformation from the days, just ten years earlier, when each exhibitor selected his own one-shot films and ordered them in a way that satisfied his own sense of authorship. By mid 1909, Edison executives were applying many principles of scientific management to film production.[93]

Porter's situation after his demotion was a delicate one. Above and beyond its formal regulation of the industry, the MPPCo provided a framework within which licensed manufacturers reached informal or secret understandings and acted in concert. Manufacturers agreed not to hire personnel away from other licensed producers, nor to hire those that had been discharged for "justified reasons" or simply left. Sidney Olcott, for instance, was dismissed by Kalem in April of 1909 because, according to Frank Marion, "he had a notion that all the manufacturers were clamouring for his services and was therefore beyond all criticism from us." "I don't know that you have a notion of taking him on, but if so I trust you will appreciate that it would have a very bad effect on the

discipline of our establishment," Frank Marion told Dyer. "I suppose this can come well within the defines of our mutual understanding as to employees."[94] Dyer, who desperately needed just such a director, nonetheless reassured Marion by return mail. Olcott, Dyer acknowledged, would be useful, but "the belief that they can leave us at will" could not in any way be encouraged.[95] In the case of Olcott, the director was properly chastened and soon rejoined Kalem in his old capacity. Directors, actors, and other production personnel had to look beyond Edison-affiliated producers for an increase in salary, recognition, or a more sympathetic employer. These restrictions applied to Porter, too.

Porter's continued Edison employment at a good salary may have been designed to discourage him from leaving and joining the independents. Although newly formed independent companies would have benefited from Porter's years of experience, the veteran filmmaker may have been reluctant to join them too precipitously, since their future was so unpredictable. Rather Porter spent his next six months at Edison working on a series of miscellaneous projects. Some of his time was devoted to testing film stock—particularly a nonflammable stock developed by Eastman Kodak. "After making several tests of the new Eastman negative and positive film, we find the speed, quality and action during the course of operation is about the same as our present film," he concluded. "The texture of the stock is much harder and not so flexible and do not think it will stand the wear and tear as our old, but this can only be determined by time."[96] Porter's reservations about the new Eastman stock soon proved accurate. When the nonflammable film was put on the market, renters protested that it wore out very quickly and they could not recoup their costs. Porter, moreover, may have devoted some time to refining the projecting kinetoscope. Although kinetoscope sales for 1908 had declined 18 percent from the previous year to $341,848, they still represented almost 40 percent of the Edison Manufacturing Company's film-related business.

Porter also made a handful of films outside the studio system. In May he directed a comedy, The $10,000 Painting , shot by Armitage and released on June 25th as An Affair of Art . For whatever reasons, this film was not well received. "Oh, Great Edison, what horrors are perpetuated in thy name!" commented the Dramatic Mirror . "This picture is pretty nearly the worst excuse for comedy we have ever seen on a screen."[97] In August, Porter was sent out west for two months (what better way to keep him away from the independents!); he filmed a "fruit industrial" and Bear Hunt in the Rockies in Marble, Colorado. Bear Hunt , his last Edison film, was released on January 11, 1910, and received a generally warm reception:

This fine film has educational as well as some dramatic value. It depicts with fidelity what appears to be a real bear hunt in the Rocky Mountains. The natural scenery is superb, and the bear is a sure enough bear. A considerable party sets out on the hunt on horseback, and with pack horses conveying their camp material. In the party are

two ladies—actor ladies evidently, as they fail at times to conceal their professional training. One of them goes fishing, and is having luck, when a bear appears. She pretends to be frightened and starts to run, but in front of the camera comes the fatal desire to pose, and we realize that the danger from the bear is mere pretense. When she arrives at the camp she again poses, facing the camera, while she tells her experience to those standing behind her. The dogs are now called, and the bear is pursued, treed and shot. We are mercifully spared a scene showing the details of butchering. Later a cub is roped, and led home by the party. Taken as a whole, the film is decidedly entertaining.[98]

Porter's last Edison film recalls one of his first—Terrible Teddy, the Grizzly King —and one of his favorites—The "Teddy" Bears .

Although Porter and White were permitted to operate outside the studio system with minimum resources, they remained only as relics of a bygone era. Porter's methods of production and representation were at odds with developments both at Edison and in the industry as a whole. This awkward situation did not endure. Perhaps Porter was in contact with the increasingly active independents, or was finally judged expendable. In any case, on November 10th Horace Plimpton notified others that Edwin S. Porter and his assistant William J. Gilroy were being dismissed.[99] A few days later they were off the payroll. Though considered America's leading filmmaker in the era before the nickelodeon, Porter had been fired.