Continued Film Production

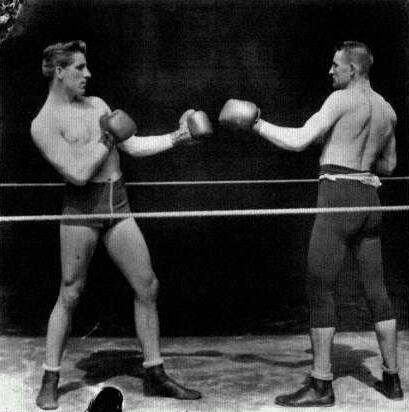

The first subject for the Latham-Rector enterprise was a six-round fight between Michael Leonard and Jack Cushing, filmed by Dickson and Heise in the Black Maria on June 15th.[41] A film of men made by men, The Leonard-Cushing Fight was meant to appeal to the sporting crowd. Again work responsibilities were forgotten as Thomas Edison happily acted as master of ceremonies and supervised the fistic proceedings. His interest was hardly dispassionate, for he found himself mimicking the boxers' thrusts as the fight intensified. When the legality of the fight under New Jersey law was questioned, Edison's role in the

proceedings had to be suppressed. Perhaps this, as much as the time needed for the production of large-capacity kinetoscopes, explains why the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company's storefront arcade on Nassau Street did not open with these films until mid August.

The fruition of Otway Latham's efforts yielded new financing from Samuel J. Tilden, Jr., enabling the group to order seventy-two additional kinetoscopes at $300 a machine.[42] Arrangements were then made for the heavyweight champion James Corbett to fight the New Jersey pugilist Peter Courtney. If he could knock out Courtney in the sixth round, the champion was guaranteed $5,000 against a weekly exhibition fee of $150 (later reduced to $50) for each set of machines on exhibition.[43] On Friday morning, September 7th, four days after Corbett's play Gentleman Jack began a Broadway run, the champion arrived in Orange with his entourage.[44] In the meantime,

Over at the Black Maria, which has been fully described in The Sun , several attendants were busy fixing the kinetograph, so that there might be no slips or mistakes in photographing the impending struggle. The Maria, as the building in which Edison's wonderful machine is located is called, reminded everybody of a huge coffin. It was covered with black tar paper, secured to the woodwork by big metal-topped nails, and was the most dismal-looking affair the sports had ever seen. Inside the walls were painted black, and there wasn't a window of any description, barring a little slide which was directly beside the kinetograph and could be opened or closed at the will of the operator. Half of the roof, however, could be raised or lowered like a drawbridge by means of ropes, pulleys and weights so that the sunlight could strike squarely on the space before the machine.

The ring was 14 feet square. It was roped on two sides, the other two being the heavily padded walls of the building. The floor was planed smooth and covered with rosin. All battles decided in this arena must be fought under a special set of rules. A round lasts a little over one minute, with a rest of a minute and a half to two minutes between the rounds. Consequently, the smallness of the ring and the shortness of the rounds necessitate hot fighting all the time.[45]

At 11 o'clock the prize fighters prepared for the ring, but they were delayed another thirty minutes by a technical problem with the kinetograph.

At 11:45 o'clock everything was ready. The men were first requested to pose in fighting attitudes for an ordinary photograph. Then the chief operator told them to get ready for the fight. John P. Eckhardt of this city was referee and W. A. Brady held the watch. In Corbett's corner were his seconds John McVey and Frank Belcher, with Bud Woodthorpe, bottle holder. In Courtney's corner were John Tracey and Edward Allen, seconds, and Sam Lash, bottle holder. Corbett weighed 195 pounds, he said, and Courtney 190. The men were ordered to shake hands and received instructions as to clinching. Then they went to their corners and waited for the signal to begin the battle. The operators were all ready now, and when the word was given the kinetograph began to buzz.[46]

James Corbett and Peter Courtney pose in the Black Maria before their fight.

Corbett succeeded in knocking out Courtney in the sixth round, and Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph (also known as The Corbett-Courtney Fight ) went on to be a nationwide success. It was shown at Thomas L. Tally's Phonograph and Kinetoscope Parlor at 311 South Spring Street in Los Angeles and in many other large-capacity kinetoscopes across the country. Corbett's contract, however, absorbed much of the profit, and it seems likely that Tilden ultimately lost money on the deal. Moreover, opposition to prize fighting made it difficult to generate additional projects in the months ahead.

After Raft & Gammon and Maguire & Baucus assumed the costs of, and increased responsibility for, making new negatives in September, the same types of subjects continued to be produced. The Kinetoscope Company paid Hornbacker and Murphy to fight a "five round glove contest to a finish" in late September. Each round, however, was limited to fifty feet of film. The

Englehardt Sisters fenced for the kinetograph with both broadswords and foils (Lady Fencers ). Pedro Esquirel and Dionecio Gonzales performed a Mexican knife duel. In January 1895, with variations on the obvious exhausted, Capt. Duncan C. Ross and Lieut. Hartung fought with broadswords on horseback in the five-round Gladiatorial Combat .[47]

Dancers, contortionists, acrobats, and novelty acts also continued to visit the Black Maria from September of 1894 through the following spring. Professor Ivan Tschernoff with his performing dogs, then at Koster & Bial's, appeared in Skirt Dog Dance and Summersault Dog on October 17th. The following day, Toyou Kichi, "the Marvellous and Artistic Japanese Twirler and Juggler," gave a performance for the kinetograph.[48] Robetta and Doreto, who performed their comic routine "Heap Fun Laundry" at the close of Tony Pastor's vaudeville bill for a week beginning on November 26th, also brought their act out to the Edison laboratory (Chinese Laundry Scene ).

With the kinetoscope "one of the recognized sights of the town,"[49] performers and amusement entrepreneurs quickly concluded that moving pictures were good publicity and could help their careers. Prof. Harry Welton's Cat Circus was one of several acts that showed improved bookings subsequent to its appearance in the kinetoscope.[50] The manager for James Hoey's upcoming farce announced a new advertising scheme: "Edison's kinetoscope and phonograph are to be combined in a reproduction of the principal spectacular and vocal feature of the new performance, the instrument to be publicly exhibited in the principal cities weeks prior to the play's appearance."[51] Such a response from the public and the theatrical community enabled kinetograph production to continue drawing from diverse elements of the amusement world.

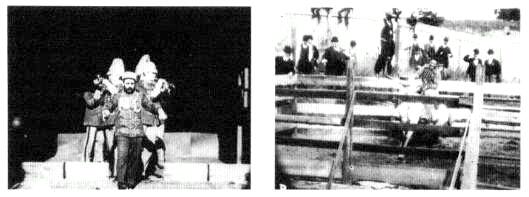

During the fall, various performers from Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, then at the peak of its popularity, came out to the Edison laboratory.[52] Buffalo Bill, his manager, and a group of Indians traveled from Ambrose park in Brooklyn to appear in a series of films on September 24th. These included Buffalo Bill, Sioux Ghost Dance, Buffalo Dance , and Indian War Council . This last film consisted of "seventeen different persons" and showed Buffalo Bill addressing the Indian warriors.[53] A small group of Mexicans appeared two weeks later to perform their specialty: the knife duel and lasso throwing.[54] On October 16th, rodeo star Lee Martin rode a bucking bronco in a makeshift corral outside the Black Maria (Bucking Broncho ).[55] Finally, on November 1st, Annie Oakley demonstrated her rifle-shooting abilities (Annie Oakley ).[56]

Performers giving specialties in regular New York-based theatrical companies flocked to the West Orange site. On October 6th, Charles Walton and John C. Slavin, from Edward E. Rice's comic opera 1492, executed their comic boxing routine. That same day Lucy Daly's Pickaninnies of The Passing Show tumbled and danced—providing motion pictures with their first images of African Americans. A somewhat later visitor, James Grundy, appearing in The South Before the War , executed a cake walk, buck and wing dance, and breakdown.

Band Drill and Bucking Broncho. The R at the bottom left of the frame stands for Raft & Gammon.

The Grundy films were then marketed as "the best negro subjects yet taken and are amusing and entertaining."[57] Bertha Waring and John W. Wilson, eccentric dancers from the musical burlesque Little Christopher Columbus , and the Jamies from Rob Roy added to this long list.

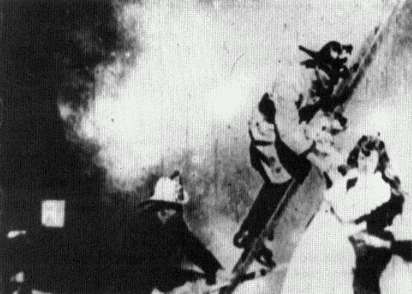

Two of the most ambitious studio productions were taken in December 1894. Early that month members of the Milk White Flag company presented the camera with five abbreviated scenes from Charles Hoyt's successful song-and-dance farce. The musical satirizes the part-time citizen-soldiers whose "commanderies" served a purely social function. Its many musical and dance numbers were perfect for the kinetoscope. One filmed excerpt, Finale of 1st Act of Hoyt's "Milk White Flag, " had "34 Persons in Costume. The largest number ever shown as one subject in the Kinetoscope."[58] Perhaps the single most ambitious subject of this period was Fire Rescue Scene , made for Raff & Gammon. Filmed inside the Black Maria, the production involved elaborate smoke effects and the assistance of a local fire department. The film can be considered an innovative extension of workplace films like Blacksmith Scene . Certainly, fire-men embodied nineteenth-century manly virtues (courage, strength, etc.), and local fire departments served as centers for many male leisure activities. The homosocial worlds of fire fighting and film production easily converged; they would do so again with much frequency in the years ahead.

Kinetograph activities slowed during the winter months and were then seriously disrupted in April of 1895, when Dickson left Edison's employ. Although this break may have occurred as early as April 2d, it was not made public until late in the month.[59] Dickson's position had become untenable. He had been fighting with Gilmore for control over the motion picture business and for primacy in the inventor's affections. At the same time he was helping two aspiring competitors (the Lathams and the founders of the American Mutoscope Company) develop their own independent motion picture technology. His de-

Fire Rescue Scene.

parture left William Heise responsible for Edison's motion picture business and ended the easy, long-standing collaborative relationship that had produced these films. In the wake of Dickson's departure, Heise proceeded with a handful of additional subjects, perhaps assisted by John Ott. When Barnum and Bailey's Circus stopped in Orange on May 9th, he kinetographed various members of the troupe in the Black Maria before their afternoon performance. Made for the Continental Commerce Company (the circus was soon going to Europe), scenes showed natives of India (Short Stick Dance ), Samoan Islanders (Dance of Rejoicing ), a renowned strongman (Professor Attilla ), and an Egyptian dancer (Princess Ali ).[60]

By mid June, Edison personnel had taken four scenes from Trilby: Death Scene, Dance Scene, Hypnotic Scene , and Trilby Quartette. Trilby , the theatrical adaptation of George du Maurier's novel, opened at the Garden Theatre on April 15th and was proclaimed "an instant and deserved success, which swelled at times to the proportions of a triumph."[61] Even before the opening, however, others were quickly presenting excerpts.[62] Although the actor playing the hypnotist Svengali visited the Edison laboratory in May 1896, it is unlikely that members of the cast did so when the show opened. Moreover, the death scene was buriesqued, suggesting the performance of a renegade group. The Edison-group had ranged freely through various forms of popular amusement to ac-

quire subjects for their productions. Yet they had not moved outside these well-defined boundaries to make actualities or, with a handful of exceptions, their own original scenes. By spring this lack of diversity, as well as the relatively high cost spectators had to pay to peep, led to declining public interest.

Edison's motion picture business faced slackening demand and other difficulties by the spring and summer of 1895. This decline can be illustrated by an incident that occurred in Asbury Park, New Jersey. For the summer season, six kinetoscopes with The Corbett-Courtney Fight were set up inside a building rented from the Asbury Park Amusement Company. This was the second year of kinetoscope exhibitions at the summer resort, but the success of the first season was not repeated. As a local newspaper explained in early August, "The kinetoscopes, although they give wonderful entertainment for those who like that sort of thing, do not seem to have been profitable thus far this summer."[63] Unable to pay the rent, the kinetoscope manager and some cohorts crept into the hall and started to remove the machines under cover of darkness. A night watchman discovered them, called the police, and warned the landlord. In the confrontation that followed the manager was outnumbered and was forced to abandon the attempted removal. The next day a distress warrant was issued turning the machines over to the local amusement company until proper payment was received.[64]

The manager's inability to meet expenses was perhaps not so unusual and symbolizes the wider problems facing kinetoscope entrepreneurs. Overseas, Maguire & Baucus faced serious competition. In London, Robert Paul was making duplicate kinetoscopes and his own original films. Paul's activities, moreover, were safe from legal action, since Edison had failed to take out foreign patents on his motion picture inventions. This severely reduced Edison's potential foreign sales. Domestic imitators also appeared, reducing sales and the price tag within the American market.[65] When the Lathams began to exhibit their crude eidoloscope projector in April 1895, this, too, deflected interest away from Edison's machine.[66] With the urging of Raft & Gammon, Edison began to experiment with projection. According to Terry Ramsaye, Edison sent experimenter Charles Kayser to the Kinetoscope Company's offices in New York, where he pursued these investigations. Nothing useful, however, materialized from these efforts.[67]

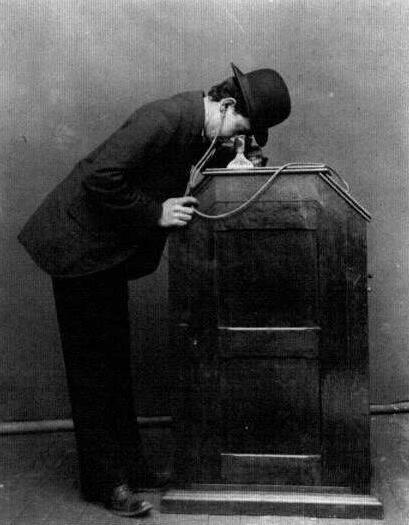

One serious effort to bolster the kinetoscope business was made in the spring of 1895: the kinetophone. A phonograph was placed inside a kinetoscope cabinet with rubber ear tubes protruding from a convenient location for the spectator. Recordings and films could then be loosely synchronized. The longstanding promise of a novelty that combined recorded sound and moving image was to be fulfilled. It was hoped that this would not only revive its novelty value but increase the range of available subjects. The local Orange Chronicle announced:

An unidentified phonograph parlor boasts a kinetoscope. By 1895 business had slowed.

With this combination wonderful possibilities are opened out before the public. An entire change will be made in the character of the objects and scenes taken by the kinetograph. Previously only scenes were taken in which there was a great variety of action, the element of sound being entirely disregarded. Hence such scenes as prize fights, skirt dances, clog dances and the like were taken. With the new combination, the eye and ear being both concerned, the range of subjects is largely increased, and many things that could not have been effectively taken under the principle of the kinetograph alone will now become available.[68]

This breakthrough was premature and no doubt forced by the onset of declining sales. Efforts to kinetograph and phonograph scenes simultaneously had been made, but without success (Dickson Experimental Sound Film and various illustrations testify to these attempts). Thus no new diversity of subject matter resulted. Rather, appropriate music was added to preexisting subjects. The Kineroscope Company announced, for example, that the kinetophone in its offices was featuring Finale of 1st Act of Hoyt's "Milk White Flag ": "as the band is

Looking at and listening to the kinetophone: a pastime that never became popular.

seen coming into view in the Kinetoscope, the music bursts forth with a volume and melody that is truly wonderful and realistic."[69]

The kinetophone was initially marketed in mid April for a cost of $400, $50 more than the kinetoscope. At least one was at Frank Harrison's parlor in Atlanta, Georgia, in May. Although he claimed that they increased business

threefold, Harrison had established a special arrangement with the Kinetoscope Company for the upcoming Cotton States' Exhibition, and his endorsement is hardly credible.[70] Within a short time, the price of the kinetoscope fell to $250 and the price of the kinetophone with it to $300. Demand for the kinetophone proved slight, only forty-five being sold.[71] Dickson's untimely departure from Edison must have harmed whatever slight prospects of success the kinetophone enterprise may have initially enjoyed.

As the kinetoscope and kinetophone novelties faded, Raft & Gammon faced fewer and fewer orders for its goods. Seeking to reverse this decline, they assigned employee Alfred Clark the responsibility for making new films. Clark, who looked after film production and sales for the Kinetoscope Company, tried to reorient and broaden the Edison Company's approach to production. That August and September he produced a group of motion picture subjects at the West Orange laboratory that were not tied to popular theatrical amusement, including several historical scenes based on well-known paintings or other iconography.[72]loan of Arc , which showed the French heroine being burned at the stake, and Rescue of Capt. John Smith by Pocahontas represented larger-than-life, semi-mythical moments. These films, which were taken outdoors, involved elaborate historical costuming. Only one survives, The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots .[73] Its tableau-like, static quality highlights the moment when the ax descends, cutting off the queen's head. In fact, this effect was achieved using stop-action substitution: the filming was halted, while the actor (Robert Thomae in female garb) was replaced by a dummy; then the action and filming resumed. The camera stop was later cleaned up by splicing the two takes together so that the film appeared to consist of one continuous shot. Other scenes, including Indian Scalping Scene and Frontier Scene (later retitled Lynching Scene ), indicate a curious penchant for the gore of murders and executions, subjects regularly depicted in wax at the Eden Musee's Chamber of Horrors.

Demand for Clark's innovative films was modest. In the following months, the handful of new productions returned to tried and true subjects: Umbrella Dance and Acrobatic Dance , featuring the Leigh Sisters; Cyclone Dance and Fan Dance , with the Spanish dancer Lola Yberri. The declining kinetoscope business most affected those people who depended on it for their livelihood and resulted in career changes. James White and Charles Webster sold their kinetoscopes in August, with White returning to the phonograph business.[74] Clark likewise sought more secure employment in the phonograph field, with Webster joining Raft & Gammon to take his place.[75] Late in the year, Raft & Gammon went for months without selling a single machine, and the partners considered selling or even liquidating their business. Then they came across a screen machine that was far superior to the Lathams'. It soon returned them to the forefront of motion picture activity in the United States and in the process revived film production at the Edison Manufacturing Company.