Cinema and Society

The rapid expansion of nickelodeon exhibitions precipitated a crisis not only over how a story was to be cinematically represented but over what was to be presented in the theaters. This latter problem created sharp tensions between the moving picture world and the larger society. As Robert Sklar has pointed out, it was as mass entertainment that the cinema and its subject matter became deeply disturbing to the traditional guardians of American culture.[195] Its increasing presence in American life led many reform groups, newspaper editors, and government officials to demand censorship or even outright prohibition of films. They attempted to limit the nickelodeons' impact by Sunday closing, sometimes harsh fire regulations, and exorbitant licensing fees for theaters.

By September 1906 Chicago papers were publicizing and supporting a crusade against the nickel theaters. The clergymen who initiated the attack claimed that moving pictures "inflame the minds of the younger generation, seriously diverting their moral sense and awakening prurient thoughts which prepare the way for future sin."[196] In New York the police began to apply the Sunday blue laws against the use of a drop curtain to moving picture shows by claiming the screen was such a curtain.[197]Views and Film Index responded in a manner that would typify the motion picture industry for years to come. First, its columnist argued that showing a burglary in which the culprit was captured or killed discouraged the impressionable viewer from becoming a burglar himself. Most of the films were therefore wholesome. Second, he maintained that the motion picture industry was reforming itself and improving its offerings, that "a comparison of the conditions today with what it was only a few years ago will testify that it has become an art, and is going higher and higher every day."[198]

Vituperative attacks against nickelodeons reached new heights in the spring of 1907. Lubin's The Unwritten Law , a reenactment drama focusing on Harry K. Thaw's murder of his wife's former lover, the architect Stanford White, was the hit of the season in many cities. But in Houston, Worcester, and other locales, police stopped showings of the film.[199] The Chicago Tribune reiterated

the belief that five-cent theaters "make schools of crime where murder, robberies and hold-ups are illustrated. The outlaw life they portray in their cheap plays tends to the encouragement of wickedness. They manufacture criminals to infest the streets of the city. Not a single thing connected with them has influence for good. The proper thing for the city authorities to do is to suppress them at once."[200] Small-town newspapers soon followed the lead of large city dailies. Even in New York City, the nation's film capital, motion pictures were under assault. Theater owners were occasionally arrested for showing films depicting murder and suicide.[201] A July report from Police Commissioner Theodore Alfred Bingham urged Mayor George Brinton McClellan to revoke the nickelodeons' licenses and asserted that the suppression of cheap shows would improve city conditions.[202]Moving Picture World asked: "When will this persecution cease? The owners of these places have done all in their power to improve them, have obeyed unjust exactions in many instances and are trying to comply with public sentiment as never before."[203]

Although these attacks posed a direct threat to the entire film industry, the Edison Company was particularly vulnerable to such crusades. Reform ministers and press representatives spoke for—or at least to—prospective purchasers of Edison records, phonographs, batteries, and cement houses. Unrestrained hostility could harm the inventor's reputation and tarnish the image of other Edison products. Some of the best-known Edison films from the pre-nickelodeon era were films of crime (The Great Train Robbery and The Train Wreckers ). Several films from 1905-6 showed juvenile delinquency in a sympathetic light (The Little Train Robbery and The Terrible Kids ). Cohen's Fire Sale showed a Jewish merchant defrauding an insurance company. William Swanson nonetheless maintained that "in the case of the Edison films one never gets a picture 'off color' among them."[204] The Kinetograph Department tried to avoid improper subjects that might have seriously offended sensibilities. As pressures from reformers mounted, top Edison executives, including the inventor himself, began to screen completed films.[205] Yet, as the Dramatic Mirror and other publications noted with surprise, what was acceptable on the stage was not necessarily so in movie houses (a reversal from the days when The Passion Play could be shown on the screen but not on the stage).[206]College Chums (November 1907) offered bawdy humor that had been "worked to death in burlesque." Nonetheless, the Edison film's play with homosexuality, transvestism, and infidelity was not so trite in the nickelodeons, which reached a wider audience in terms of age (children), gender (unescorted women), socioeconomic background (lower classes), ethnicity (recent immigrants), and geography (rural areas).

By late October 1907 Edison advertisements began to announce that "Edison films depend entirely for their success upon their cleverness. They are never coarse or suggestive."[207] Edison soon appeared to side with critics of the nickelodeons. On the cover of Moving Picture World , a photograph that portrayed

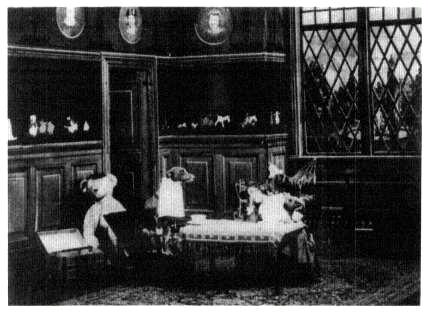

Playmates.

Edison as the stern father accompanied his signed statement: "In my opinion, nothing is of greater importance to the Success of the motion picture interests than films of good moral tone. Motion picture shows are now passing through a period similar to that of vaudeville some years ago. Vaudeville became a great success by eliminating all of its once objectionable features, and, for the same reason, the five-cent theatre will prosper according to its moral attitude. Unless it can secure the entire respect of the amusement-loving public it will not endure." [208]

The industry was caught between the desire to make sensational films that would sell and the need to make films that would avoid the wrath of authorities who might interfere in their business. More than most companies, Edison tried to accommodate its critics. Sentimentality was frequently indulged. Playmates (February 1908) is about a child and her faithful companion, a dog, which is dressed in a costume and given a pipe. When the child gets sick, the dog informs the parents and stays with the bedridden girl. When the doctor proclaims the child's case to be hopeless, the dog prays (!) and effects a miraculous cure.[209] A reviewer called it "a well produced and touching story, which called for many exclamations of 'fine, sweet,' etc . . . . The only fault with this film is that it is too short, as an audience is never tired of such a charming subject."[210] Many pictures, for instance A Suburbanite's Ingenious Alarm and Bridal Couple Dodging Cameras , were fluffy, innocent comedies. Others, like A Sculptor's

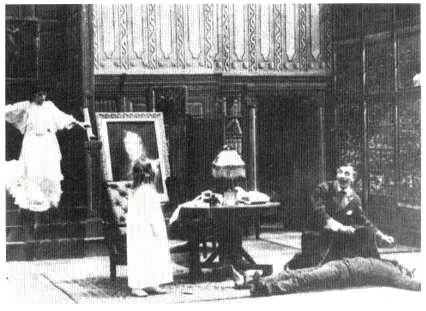

In The Gentleman Burglar, the beloved father in the portrait dies

a hunted and forgotten criminal—as his daughter looks on.

Welsh Rarebit Dream (January 1908) and The Painter's Revenge (May 1908), presented inoffensive film tricks. When a release like The Gentleman Burglar (April 1908) dealt with crime, it had a heavy moral overlay. A gentleman burglar abandons his wicked ways, marries, settles down, and starts a family. He is blissfully happy until an old confederate blackmails him. The gentleman burglar tries to steal the needed money from his father-in-law, but is discovered and turned out. He returns to his old haunts and quarrels with a friend, killing him. He goes to prison, escapes, and returns to his family, only to discover that his child no longer recognizes him. When he realizes that his wife has married her old suitor, the shock kills him. The truth is kept from the wife, "who never knows that the man she loved was nothing more than a common thief."[211] Certainly even the most conservative critic had to acknowledge that this film contained an unequivocal message: "Crime does not pay."

"Hangings, murders and violent deaths in any form should be barred from the sheet," Edison declared in a mid-1908 Variety interview.[212] Yet his company frequently placed these controversial narrative elements in a historic or patriotic setting to diffuse controversy. The tactic often worked: schoolchildren at Public School 188 in New York City were escorted to the local Golden Rule

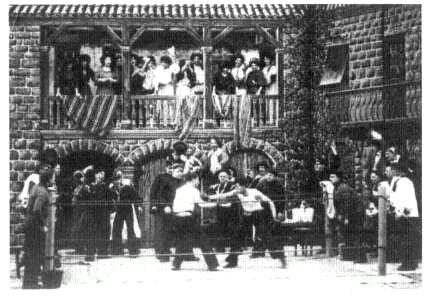

Patriotic violence in A Yankee Man-o-Warsman's Fight

for Love seems to have met with approval.

Theater on Rivington Street to see The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (October 1907), in which British soldiers kill the tollgate keeper's daughter.[213]A Yankee Man-o-Warsman's Fight for Love (January 1908) included a three-round fight between an American and a British sailor, with "several good knockdowns."[214] Because violence was used to defend American honor, it was apparently acceptable. Nero and the Burning of Rome could show the decadence and cruelty of the pagan emperor and still be shown in an occasional church. Even Edison felt comfortable endorsing it as "one of the most interesting [pictures] that has come to my notice."[215]

These efforts to place sensationalistic actions in an acceptable context did not always work. After Nero and the Burning of Rome was shown in his church, Rev. E. L. Goodell protested: "There was nothing in the moving pictures of scantily clad women that could appeal to the innocent mind of a child, but there was a great deal in the pictures of bloodshed that caused terror."[216] With The King's Pardon showing one robbery, two brutal murders, and "a sensational finish of a man standing on the gallows and the executioner adjusting the black cap and the rope," Moving Picture World remarked, "We are once more again going back to highly sensational films."[217] Despite its debt to the stage and the artistic opportunities it gave the lead actor, Heard over the 'Phone must

have been controversial. Its portrayal of a helpless father, unable to protect his family from a wanton criminal, completely violated norms of desirability. The basic story for The New Stenographer (November 1908), the man's employment of an attractive secretary and the subsequent discovery by his jealous wife, had been done often in earlier films. Now the subject had become too hot to handle. One critic said he had to pinch himself to be sure he wasn't dreaming when he saw the manufacturer's trademark.[218]

Attacks by newspapers and government organizations did not abate during 1908. Formal censorship of films was established in several cities including Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Omaha, Nebraska City, and Butte.[219] New Jersey passed a law that forbade children under sixteen years of age to attend movies unless accompanied by a parent.[220] Sunday shows were prohibited in many places including, briefly, New York.[221] Licensing fees were imposed or raised by city, county, and state governments. Coordinated action by motion picture exhibitors, renters, and producers was needed to protect the industry's interests. Industry self-regulation might eliminate the most provocative films while still leaving enough bite to draw patrons to the theaters. Moreover, national, state, and local motion picture organizations were needed to lobby against excessive restrictions and do battle in the courts. The desire for such organizations had encouraged the formation of the Edison combination. Instead, the film war divided the industry and made effective action against anti-motion picture forces more difficult. Here, too, incentive existed for a reconciliation between the Edison and Biograph interests.