The Kinetograph Department Forms Two Production Units

Frank Dyer replaced William Gilmore as vice-president of the Edison Manufacturing Company in June 1908, while Charles H. Wilson was made general manager. Dyer was particularly disturbed by Edison's paltry share of the American film market. Joseph McCoy's June 1908 survey of theaters indicated that the company provided less than 10 percent of their films. In contrast 3.5 percent of the films were supplied by Pathé (see table 5). In response, Dyer's new regime

Table 5. | |||

Pathé | 177 | ||

Vitagraph | 82 | ||

Edison | 45 | ||

Essanay | 42 | ||

Lubin | 40 | ||

Kalem | 32 | ||

Selig | 26 | ||

Méliès | 14 | ||

Total Licensed Films | 458 | ||

Total Unlicensed Films | 57 | ||

Total films seen | 515 | ||

SOURCE : Joseph McCoy, report, June 1908, NjWOE. McCoy's addition was inaccurate and has been corrected for purposes of this analysis. | |||

quickly established a second production unit in the studio. Former Biograph employee Fred Armitage was hired as a cameraman at $40 per week beginning in late June or early July 1908. He began to work with Dawley, who was likewise making $40 per week, while Porter operated his own unit with assistance from Cronjager, the newly hired James Cogan ($35 per week), and others. Production again doubled and studio personnel responsible for negative production expanded to at least eleven. Porter's salary was soon raised another $10 to $75 per week. At the Edison factory in West Orange, Charles Wilson ordered the Kinetograph Department to enlarge its release print capabilities: "Mr. Moore is now furnishing us with 2,000 feet of negative film per week, and work of enlarging the film dept. at factory should be pushed with all possible despatch, so that we can handle this amount weekly. As it is at present, our factory limit is about 100,000 feet per week, whereas with 2,000 ft. of negative, we should have factory capabilities of 200,000 ft."[162] Actor Justus D. Barnes (the outlaw leader in The Great Train Robbery ) was hired on a full-time basis in late July. Actress Francis Sullivan likewise joined the staff in late October. Although both may have had additional duties, this was the beginning of Edison's permanent stock company.

Porter was becoming a de facto studio executive. This move toward a multi-unit system of production remained tentative, however, in that Porter continued to head the first unit and run the studio. Each unit was still organized on a collaborative basis. Dawley and Armitage were paid the same amount, and treated as equals—although Dawley always enjoyed Porter's ear. In fact, collaborative working methods continued to operate across units. As Dawley later explained, Porter "would contact me on the phone when I was working on location and say 'Dawley you better come back to the studio at once, I'm all

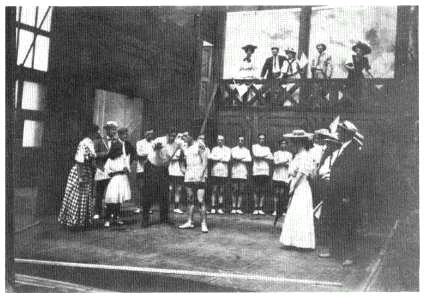

The Little Coxswain of the Varsity Eight.

balked up on this directing stuff. I just can't make it work out the way I want.'"[163] Here Porter's dependence on collaborative working methods continually impeded efficient management based not only on separate production units but on a clear chain of command and responsibility. At a time when Griffith, who had assumed the position of director at Biograph, was producing over two films a week, two production units at Edison struggled to maintain the same output with much less critical success.[164]

The first two Edison films to receive strong negative criticism in the Dramatic Mirror were the first films made under the new two-unit system, Dawley and Armitage's The Boston Tea Party and Porter's The Little Coxswain of the Varsity Eight (both July 1908). The Boston Tea Party was "marred by the obscurity of the opening scenes."[165] A review of The Little Coxswain elaborated on the lack of narrative coherence (see document no. 26). Because the film was not based on a well-known play or story, Porter's critics had no ready framework for understanding. If the synopses had been turned into a lecture or if actors behind the screen had illuminated the "numerous conversations and altercations" with dialogue, spectators would have been less disoriented.

DOCUMENT No. 26 |

The Little Coxswain of the 'Varsity Eight (Edison).—We have hitherto noted a failing of certain Edison films, that they lacked clearness in the |

(Text box continued on next page)

telling of a picture story. This drawback was not present in The Blue and The Gray, but it was evident in The Boston Tea Party reviewed last week, and it is more than ever apparent in The Little Coxswain of the 'Varsity Eight. This film needs a diagram to interpret it, without which the various movements of the actors are, for the most part, meaningless to a spectator of average intelligence. It goes without saying that such a fault is a serious one with any film and should be carefully guarded against. More particularly do we look for the Edison Company to be free from criticism along this line, because the name Edison should stand for the best the world over. The coxswain, it appears, sold the race, or tried to, to a scoundrel who bet heavily that the crew would lose; but the perfidy was discovered, a little girl was substituted as coxswain and the crew won. Further than this the film tells us nothing that is understandable. Young men and girls appear to be having numerous conversations and altercations, there is a card game and somebody gives one of the girls a bank check for some purpose or other, but who they are and what it is all about we are unable to discover without reference to the synopsis of the story sent out by the Edison Company, which, however, is not available to the audience generally. It is especially regretable that the story is so badly told, because the film gives an excellent picture of the preparations for the race, the race itself and the scene following the victorious finish. |

SOURCE : New York Dramatic Mirror , July 25, 1908, p. 7. |

Although enthusiasm for Edison films was declining somewhat by mid 1908, the pictures still received as much praise as Griffith's Biograph productions. With Tales the Searchlight Told (July 1908), Porter returned to Coney Island:

By representing a rustic visitor ascending a searchlight tower at Coney Island, where he secures a telescope and looks through it wherever the light is directed, the Edison Company has invented a novel way of presenting a series of interesting views of Coney Island, taken from elevated points. All the chief sensational features of the great resort are presented, and a series of night views are shown, the weird effect of the electric illuminations as reproduced on the film, being truely startling. The pictures close with views among the bathers on the beach in which a number of comedy situations are introduced.[166]

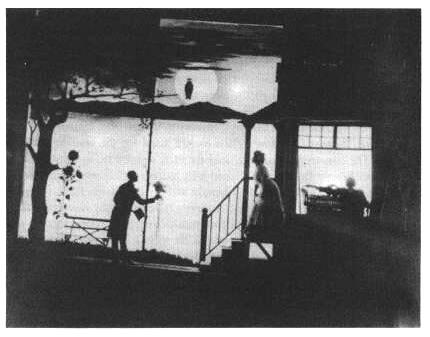

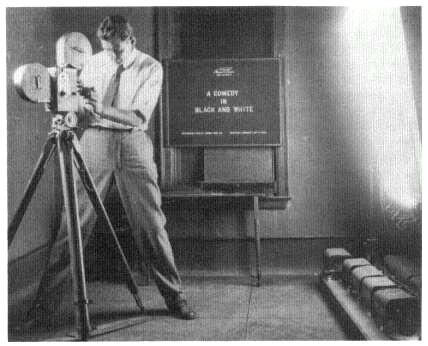

Like How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game , the film recycled actuality footage using point-of-view masks. In this case, the shots were taken from Coney Island at Night .[167] At the same time, the device of a country tube visiting Coney Island to see the sights recalls Rube and Mandy at Coney Island. A Comedy in Black and White (Porter, August 1908) was a silhouette film "produced in a particularly interesting and attractive manner. The story has to do with the calls of two lovers on a certain lively belle, whose father objects

A Comedy in Black and White.

to the visits. The action is amusing, but the chief charm of the picture is the unique style of the photography."[168] When Porter relied on simple narratives, embellished with special photographic effects, his films still garnered favorable comment.

The Face on the Barroom Floor (Porter, July 1908) was chosen as "feature film of the week" by the Dramatic Mirror :

The subject is of such high class and is handled in such an able and original manner that it at once commands attention. The old-time popular poem, "The Face on the Barroom Floor," is the basis for the picture. Verses from the poem are thrown on the curtain at intervals in the film and between the verses scenes illustrating the story are given. A barroom is shown and it is the real thing. The ruined artist, reeling and in rags appears, and after being treated to a drink tells his story to the deeply interested men in the barroom. As he is telling of his downfall and the cause, the scenes he is relating appear as if in a vision in the large mirror over the bar. Then he draws the face of his faithless wife on the floor and falls dead.[169]

As with The Night Before Christmas , selected lines served as intertitles to help spectators maintain a conscious correspondence between poem and picture and to facilitate their understanding of the film.

Reliance on an audience's prior familiarity with the story, increasingly outmoded by the nickelodeons, was further weakened when Harper Brothers won

Shooting titles for A Comedy in Black and White.

a court case against the Kalem Company for producing a film version of Ben Hur (December 1907) without permission of the copyright owners.[170] Henceforth motion pictures were subject to copyright restriction as dramatic productions, curtailing the free borrowing of song lyrics, stage plays, and comic strips that had been an important element in early film production. Subsequent films continued to have antecedents, but they were disguised in many instances to protect the filmmakers, thereby undermining the audience's ability to use the original story as a trot. The Kinetograph Department paid little attention to these new restrictions when they purchased the idea for The Face on the Barroom Floor from a scenario writer. After the poem's original author, H. A. D'Arcy, demanded compensation, Edison lawyers informed him that he had inadequately protected his poem by failing to indicate it was copyrighted.[171]

Edison executives did not have to worry about copyright with another poem-based film, The Bridge of Sighs (Dawley and Armitage, October 1908). Written by the Englishman Thomas Hood (1799-1845) shortly before his death, the poem describes a young suicide who throws herself into the river and drowns. Having no well-developed narrative, the poem lent itself to a reworking of themes expressed in The Miller's Daughter (1905). A country lass runs off to the city with a man who uses her and then abandons her. Her situation becomes more and more desperate. Finally, penniless and without hope, she throws her-

self off the "Bridge of Sighs." Instead of being rescued by a faithful lover, she dies. The Dramatic Mirror declared the film to be "one of the most effective moving picture productions we have seen in a long time. Lines of the poem are thrown on the screen between various scenes, adding to the effectiveness, but if they had been omitted the picture story would still have been complete and powerful so well is it arranged and acted."[172]

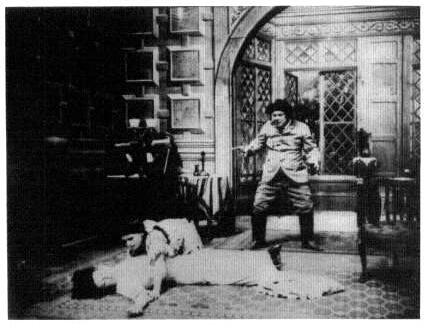

Porter shot Ex-Convict No. 900 (July 1908) as Dawley was making The Bridge of Sighs . A meticulous remake of his earlier The Ex-Convict (1904), the picture was nevertheless heavily criticized. "The story of this film resembles to a considerable extent a well-known vaudeville sketch, which may account for the lack of clearness with which the pictures are made to tell the story. As THE MIRROR has frequently pointed out, when motion picture actors follow in detail a stage drama they usually fail to get the story out to the spectators. In this film, also, the action in a most critical scene is pictured in so much dim obscurity that one finds it difficult to tell what is going on. The plot, itself, is a good one, although none too well handled in this instance."[173]

The basic story for The New Stenographer (Porter, November 1908), had been used in earlier films like Biograph's The New Typewriter and The Story the Biograph Told . (In 1911 Vitagraph remade the film under the same title; it undoubtedly had many vaudeville antecedents, too.) The plot revolves around two partners' employment of an attractive secretary and the subsequent discovery by one man's jealous wife. The Mirror declared this one to be "a very amusing and a particularly well acted comedy."[174]

Several Porter/Edison films continued to offer variations on a simple premise. Fly Paper (Porter, June 1908) recalls The Terrible Kids . Two bad boys have a fine time covering people with flypaper until they are caught and plastered with the sticky material by their victims.[175] The troublemakers were no longer allowed to go free. Ten Pickaninnies (Porter, August 1908) recalls the childhood rhyme "Ten Little Indians." Each scene was introduced by a couplet, beginning with

Ten little Darkies eating Melon fine.

Farmer catches one leaving but Nine.[176]

"A clever idea is carried out in this series of ten scenes," felt Frank Woods, who later wrote the screenplay for The Birth of a Nation .[177] In Dawley and Armitage's The Lover's Guide (September 1908), a young man uses a how-to manual to facilitate his courtship of women; a series of disastrous incidents result. Moving Picture World approved: "'Lover's Guide' is not what can be called as high standard work as 'Ingomar' of the same manufacturer, but is better received, as the audiences can understand and follow the plot. It is an amusing, well produced, comic picture with some good photographic effects." [178]

Other Edison films continued to tell simple stories that were easy for audiences to follow. When Reuben Comes to Town (Porter, July 1908) elaborated

Ex-Convict No. 900. The final scene reprises the ending of The Ex-Convict.

on the basic idea for Another Job for the Undertaker (1901) and Vitagraph's The Haunted Hotel (1906), allowing plenty of opportunities for film tricks. A farmer checks into a hotel, where all sorts of bizarre incidents take place. He is attacked by huge bedbugs and robbers. By the conclusion, he is delighted to get home alive. Buying a Title (Porter, August 1908) was "slightly reminiscent of a popular vaudeville sketch."[179] A wealthy man wants his daughter to marry a foreign count, but she prefers her American sweetheart. The father is outwitted, and the count suffers a beating. It was declared a clever, clean-cut comedy that was much appreciated by the audience that saw it at the Keith & Proctor's Union Square Theater.

Although Wifey's Strategy (Porter, August 1908) was not a particularly complicated story, it was criticized from two different perspectives. A husband disapproves of his new wife's culinary abilities and decides to hire a cook. The wife disguises herself and manages to get the job. The disguised cook makes life miserable for the husband until the ruse is exposed and the couple are reconciled. Variety felt it was an old idea, suggesting that "the producers are suffering from a paucity of original plots." Nonetheless, it was "well laid out and acted and amused."[180] The Dramatic Mirror disagreed, finding the idea clever, but "so poorly handled that the Edison Company must feel just a little bit ashamed

to take the money."[181] Again, familiarity facilitated spectators' appreciation, while its absence led to confusion and criticism.

One Porter film with a narrative of more than usual complexity, Heard over the 'Phone (August 1908), was praised by the Mirror as a particularly novel subject:

Heard Over the 'Phone is the story of a family living in the suburbs, near Scarsdale evidently. The father, after discharging his hostler for brutal treatment of a horse, goes to business, leaving his wife and child alone. The hostler, in revenge, enters the house to rob. The wife observing his approach, calls her husband over the phone, but she is attacked by the robber, drops the phone and is murdered, the sounds of the conflict and tragedy being carried to the ears of the horrified father at the other end of the wire. The acting of this picture is good, and photographically it is especially artistic.[182]

The film was based on Au téléphone , a play by André de Lorde, which was first presented in Paris in November 1901 at the Théâtre Antoine. An English version, At the Telephone , opened in New York City during October 1902 as a curtain raiser.[183] Subsequent revivals were likely: the play offered a challenging role to the male actor, who conveyed the wife's murder through his changing expression as he listened on the telephone. In March 1908 Pathé released the film A Narrow Escape in the United States; it was based on the same play but substituted a last minute rescue for the bloody ending. Six months after the release of Heard over the 'Phone and a year after the release of A Narrow Escape , Griffith made The Lonely Villa , which was indebted to the Pathé film.[184]

The differences in narrative structure between Heard over the 'Phone and The Lonely Villa are typical of the different representational systems used by Porter and Griffith. Information about the Edison film is scarce, but Porter apparently showed two actions—the husband at the office and the murder at home—simultaneously with a split-screen technique. Griffith, of course, cut back and forth between husband, wife, and robbers in a way that built suspense.

Pocahontas (Porter and Will Rising, September 1908), based on a play produced by Will Rising and originally given at the Jamestown Exposition, was reviewed approvingly in the Dramatic Mirror , which favored films of an instructional or "elevated" nature:

This is a creditable attempt to tell in picture narrative the story of John Smith, Powhatan, Pocahontas and Rolfe, the story ending with the marriage of Rolfe and Pocahontas. Historical subjects, such as this one, should be encouraged not only because they are interesting but also for their instructive value. The different episodes are well selected, the scenery is excellent, and the acting above the ordinary. One or two points in the costuming and stage settings are open to question, historically, notably the use of Navaho blankets and the manner of dressing the hair of the Indians, but the general character of the production is of such high order that we need not be too exacting in this respect.[185]

Heard over the 'Phone. The despairing husband appeared

in the darkened left portion of the screen.

Sime Silverman at Variety did not share this educational bias and criticized the film much more severely:

"Whoever stage managed that picture made a bum of it," said one evidently "wise" person at the Manhattan Wednesday evening. While the opinion may have been slangy, it strikes home. "Pocahontas" is the historical story involving John Smith and John Rolfe, Pocahontas' husband. History will probably tell if the Indians were in the habit of shaking hands in the 16th century as a token of friendship. Somebody said they had a "pipe of peace." And the Indians in "Pocahontas" look like Chinese ballet girls must appear, if they have ballet girls in China. Also the Colonists who were at Jamestown in history—and the picture—resemble a crowd of Hebrew impersonators. "Pocahontas" could only be saved by proclaiming it a comedy subject. It is a pity the waste of time this picture caused, for it is rather elaborately laid out. The Edison Company produced the series.[186]

Surviving fragments of the film affirm Silverman's strongly negative reaction.

By early fall 1908, Mirror assessments of Biograph and Edison films had shifted, reflecting a more general change in the overall film industry. During the first week in November both companies released films based on the popular William DeMille play Strongheart , which focused on an Indian's attempt

She.

to integrate himself into white society. Griffith's The Call of the Wild (September 1908) found special favor. Remarking on the popularity of Indian stories for motion pictures, the Mirror declared that "none . . . can be truthfully said to excell the latest Biograph offering in the particular elements that go to make up a successful moving picture story."[187]A Football Warrior (Dawley and Armitage, October 1908) was complimented for its elaborate detail, but the Mirror found its story line somewhat obscured by excessive shadow and the extreme distance between actors and camera.[188] A mid November overview of Edison productions observed:

Edison pictures are noted for elaborate scenic productions and the artistic beauty of the scenes, whether natural or painted interiors, but these results are sometimes secured at the expense of clearness in telling a picture story. Important action taking place in artistic shadow or at a distance which permits of a beautiful and extended view may, and usually does, weaken the dramatic effect. This criticism is not always true of Edison pictures, as there are frequent occasions when art has been attained without loss of lucidity. Edison subjects are also nearly always of striking character with novel effects.[189]

In contrast Biograph films were distinguished by a closer camera, which showed actors in "heroic size" and enabled them "to convey the ideas intended with utmost clearness."[190]

The Mirror critic felt that She (November 1908), the Kinetograph Department's adaptation of Rider Haggard's novel and the subsequent nineteenth-century stage play, "might have been more comprehensible if the adapter had not undertaken to tell so much, but, on the other hand, there would not have have been so many spectacular scenes with sumptuous settings if the story had been curtailed."[191] Reviewing The King's Pardon (Porter, November 1908), the same critic noted, "There is doubtless an interesting story which this picture is

meant to tell, and it has the advantage of elaborate scenic surroundings and fairly capable acting, but the arrangement of the scenes and action fail to give us a clear, connected narrative, and we are constantly in doubt as to the trend of the story."[192] The issue of linear temporality was again raised; the critic suggested that "a scene showing the preparations for the hanging inserted between the scenes showing the ride to the prison with the pardon, would have added interest to the conclusion."[193] Far more comfortable with pre-nickelodeon narrative constructions, Bush remarked that "among the scenes deserving special praise is the ride of the King's messenger."[194] By late 1908, however, cross-cutting was recognized as a significant editorial procedure that could add credibility and excitement to the narrative. Porter's failure to utilize it was becoming a consistent basis for criticism.