The Edison Manufacturing Company Opens Its Bronx Studio

Gilmore's belated decision to increase the rate of film production in response to the demands of the nickelodeon era coincided with the hiring of James Searle Dawley on May 13, 1907.[65] A playwright, Dawley had been working for the Brooklyn-based Spooner Stock Company as its stage manager. His adaptation of Ouïda's Under Two Flags and his musical comedy Aladdin and His Magic Lamp were performed by the Spooner Company during the theatrical season.[66] Another one of his plays, On Shanon's Shore , had been copyrighted by the Spooners.[67] Dawley was in charge of renting films that were shown between acts of the stock company's plays, a job that took him to Waters' Kinetograph Company, where he eventually met Porter. As the theatrical season came to a close, Dawley was looking for employment. After an interview, the studio manager offered him a job at $40 a week.[68] Dawley joined Porter's staff but did not give up the theater: over the next year and a half, he was to complete at least four plays.[69]

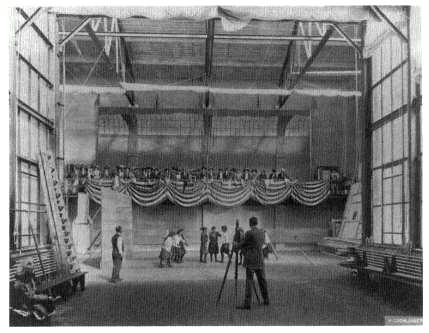

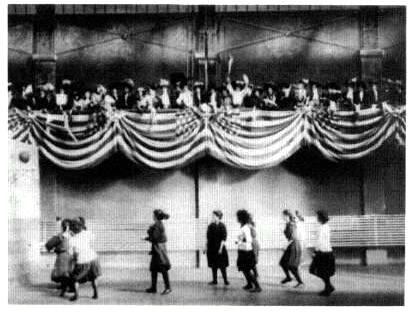

Filming A Country Girl's Seminary Life and Experiences inside Edison's new studio

in March 1908. Next page, a frame from the film.

Two weeks after Dawley joined the Edison staff, Wallace McCutcheon left the Kinetograph Department. The reasons for McCutcheon's departure are unknown, but Porter's salary had been increased from $40 to $50 in March while his remained unchanged. By October 1907 McCutcheon was back working for Biograph.[70] Although Dawley arrived during the making of Cohen's Fire Sale , he remembered Porter's next film, The Nine Lives of a Cat (July 1907), as "my first picture." It was also the last subject to be made before the filmmakers moved into their new studio.

Edison executives had recognized that they needed a new studio soon after fiction narrative films became the company's dominant type of film production. Joseph McCoy, who found a site for the new structure, recalled:

In 1904-5 the Edison Company decided to build a moving picture studio in New York and it was up to me to select a suitable location. I looked at all the vacant places that real estate dealers had listed in Manhattan, but their prices were all too high. I then went over to the Bronx and selected about twelve locations. Mr. Dennison was Secretary of the Company at the time and a photographer. He took photographs of the locations I selected to show to Mr. Gilmore. Moore, Porter and Pelzer visited all the

locations and selected the ground for the studio at 198th Street and Oliver Place, 100 × 100, property owned by Frederick Fox and Company, real estate dealers.

I called to see Fox about buying the property. Fox said he would sell the property for $13,000. I wanted a ten day option on the property at that price. He assured me that the price would be no higher. A couple of days later he telephoned me that his price on the property would be $15,000. I took the matter of the increased price up with Mr. Gilmore. Gilmore, Moore, Pelzer and Ed. Porter looked the location over carefully. As the price of $15,000 was lower than the other locations, Mr. Gilmore said "Take it at the price of $15,000."[71]

This 100' × 100' plot of land on the north side of Oliver Place and the east side of Decatur Avenue near Bronx Park was purchased for $15,000 on June 20, 1905, from the City of New York.[72]

The studio was to be built using reinforced concrete and Edison Portland Cement. Agreements to complete the studio by the spring of 1906 were signed with several contractors just before Christmas 1905. Delays followed. Serious work did not begin on the studio until summer, at which time the studio's completion was announced for the fall at an anticipated cost of $50,000.[73] (The actual cost was $39,557—not including land.)[74] Construction continued over the next year, however, taking much of Moore and Porter's time. As Dawley recalled in his hesitant, scrawled memoirs:

I had the pleasure of watching [the big studio in the Bronx] being built and help [put into working [order]. What a huge place it seem[ed] to Porter and I after working h our former place, a[n] old abandoned photographic studio on the top floor of the building with a sky light roof. Every time we started to take a picture we would hay to run out on the roof next door and see if the sun would pass over a cloud . . . our 21st street studio was about the size of a large office room.

Our Bronx studio seemed like a whole floor in comparison but before 2 years were out, it seemed to be to[o] small.[75]

Porter and his colleagues moved into their new headquarters on July 11, 1907, although much of the work was unfinished.[76] Heating and ventilation were not completed until October 15th. A roof had to be redone by mid De cember. The studio was near enough to final completion for publicity photo graphs to be taken on March 14, 1908, during the making of A Country Girl's Seminary Life and Experiences .[77] "The Edison studio is said to be one of the finest and largest of its kind in the world," reported the Dramatic Mirror . "The building itself is 60 by 100 feet, built of concrete, iron and glass. The scenic end of the studio, corresponding to the stage in a theatre, except that it is not raised is 60 by 60 feet and 40 feet high. Here the scenes for film productions that cannot be made with natural outdoor backgrounds are painted and set."[78] With work continuing until June or July, the fitting out of the new studio was largely Porter's responsibility. This included custom designs for everything from lighting equipment to a mechanized developing setup for negatives (which he personally operated). The studio emulated Edison's laboratory, with all likely materials and gadgets close at hand (see document no. 23).

DOCUMENT NO. 23 |

EDISON CO.'S NEW STUDIO. |

On a hillside near Webster avenue, the Bronx, New York, the Edison Manufacturing Company has erected a unique building, entirely of one piece, like a rockhewn temple. The material is concrete, with a roof of glass over the larger portion of the building. This odd looking structure attracts the attention of every passerby, while comments upon its probable use are varied and often ludicrous. Some are sure it is an electric power house, although the glass roof is puzzling; others think it is a dynamite factory built to avoid danger from explosion and fire. |

Construction on the building commenced in the summer of 1906; its concrete walls, floors, roofs, ceilings and window casings, all molded in the soft mixture which was used thousands of years ago by the ancient builders, were put up before winter set in. An inspection of this method of house building will convince any one that Mr. Edison is right in using concrete for a photographic studio. Not to mention economy in cost, the |

(Text box continued on next page)

hardness is that of rock itself, and therefore neither dampness, frost, nor gnawing rodents can affect it. Dust is minimized, and the floors and walks can be cleaned, washed or swept like a stone house. Again it is hermetically air proof and cold proof, while in the summer the heat penetrates slowly. |

All these considerations are of great value to photographers and the building of a moving picture. The building extends for 100 feet along Decatur avenue; it is 60 feet wide and 35 feet high—an imposing object seen from Webster avenue. |

This studio is in two parts, distinct, but standing on a common basement story. On the south side stands a plain oblong office building, three stories high, containing offices, dressing rooms, chemical laboratories, darkrooms, tankrooms and drying halls, with other necessary compartments. This faces a glass court. These two parts are connected by a sort of open hall, or atrium, directly open to the stage in the studio. |

The main entrance to the offices on the avenue side opens into an entrance hall or reception room for visitors, neatly furnished. On the left is the door of the loading and chemical washrooms, which can in a moment be turned into a darkroom by simply switching off the light and shutting the door. Here a faint red light burns, and the photographer can "load" the eight inch circular boxes holding the blank films. Many other details of the work are done here also. On the right of the reception room a door leads into the main office. It is a neatly kept room, with the usual desks and office furniture, and on one side is a library shelf of books, including history, romance, adventure, travel, fairy tales—books from which particular information is gathered for constructing plots for the pictures. |

Passing through the offices one comes out into the main hall or atrium before mentioned, whence a full view of the stage is obtained, of which more anon. Opposite the doors of the dressing rooms are seen, and these are four in number. Each dressing room is fitted up as in a theater, with makeup stands and tables, long wall mirrors, wash basins and even shower baths, while the windows are given plenty of light—more, probably, than many an actual theater room can boast. Every convenience and necessity is provided, except, indeed, easy chairs, for there is no lounging whatever in the Edison studio. A busier place would be hard to find. |

Down under the main floor is a long, roomy place of great interest— the property room. Yes, there is even the property man here, for the numerous costumes, paraphernalia and necessaries of the work are legion and must be carefully taken stock of. Mr. W. J. Gilroy is property man, and has many interesting features to show one down in the 60 foot long property room. Among other articles are 18 Springfield rifles and a small |

(Text box continued on next page)

armory of other weapons, toys, Roman togas, fairy costumes and lay figures, eagles, and so on. Although not yet a year old, the property room is already filling up. |

Upstairs, on the second floor, are certain mysterious rooms, where uninitiated persons are not admitted, although it is to be guessed that they are for experimental work and secrets of the trade. On the third floor, however, are some highly fascinating rooms, the developing and drying chambers, photographic darkroom and chemical laboratories. |

E. S. Porter, chief photographer and superintendent, is eminently fitted for the responsible position he holds. His ingenuity is constantly exercised; inventiveness and practical method, so necessary to the building of motion pictures, are at his finger ends. |

The scenes painted under Mr. Stevens' direction by the scenic artists, are in distemper—that is, they use only blacks, browns and whites, with the varying shades of these, as photographs do not take color as color, but only suggest it. Houses or block scenery are built up and the stands and wings constructed as in a theatre, only with much more attention to details and naturalness. For the camera, unlike the eye, can not be easily deceived. "Staginess" is avoided and realism is in every case given place over "effect." Scenes indoors can be taken at any time, now that the new and wonderful artificial daylight has been introduced at the studio. |

Much of the apparatus for controlling this light is the device of Mr. Porter himself, and the strength of the violet rays capable of being thrown from any part of the stage on any other part is almost beyond belief. Equal to a thousand of the ordinary arc lamps, the light concentrated on the stage by the reflectors is in photographic effect calculated at the following intensity: Taking the arc street light at its usual power of one thousand standard candles, the studio light equals one million candle power. Such a light in violet rays, is not glaring, but is like daylight diffused. |

The electrical equipment of the whole building is perfect and interchangeable, and especially so these mysterious stage lights. An ordinary theater switch box, with spider boxes and the usual maze of connections, is used. Electric motors of different sizes come handy for mechanical effects, and so there can be produced any sort of scene whatever, even a water scene. |

A water scene? Certainly; and the mystery is explained when we examine the floor of the stage. This floor, 55 × 35 feet, is built in square sections, which can be lifted away, one by one. Beneath is discovered a great tank, the full size of the stage and 8 feet deep. The floor and beams |

(Text box continued on next page)

are so arranged as to render the formation of a pond, a fountain or lake, or even the seashore, easy according to the number of sections of floor taken up. |

A film several hundred feet long would hardly go into a photographer's developing tray, except in Brobdingnag, the giant's country; so special apparatus is used in development. The finest equipment probably in the world is here at the Edison studio. Up on the third floor is a mysterious room, which at first glance looks like some new kind of Turkish bath, there being six porcelain tubs ranged down its length. These are as large as bathtubs, much like them in appearance, but have apparatus around which would disconcert anything but a chameleon. Underneath each is a gas jet series for heating, and at each end are axles, cranks and motors. The latter are compact little devices which are used to turn the axles aforesaid. Now the other side of the room contains several huge drums, hollow and open ended, like cylinders. Mr. Porter who himself conducts the important process of developing, places one of the cylinder drums on the axles of the first tank. This contains the developer and the bottom of the drum dips into the fluid. Then a negative is unwound, all light having been excluded by double curtains at the window and a red light turned on along the falls. The several hundred feet of film is wound carefully on the drum, which is kept in motion until the pictures on the negative begin to "come up." The red light burns magically, lighting dimly the great revolving drum, like a hall of necromancy. The light comes from curious conical devices. |

After development the drum is lifted into a tank of water, warmer than blood heat, and from there at once lifted over to number three tank, where the hypo clears the pictures. While the first drum is on its way down the room from tank to tank a second and third are started after it, each bearing many hundreds of tiny pictures. The series of tanks contain: No. 1, developer; No. 2, warm water; No. 3, hypo; Nos. 4 and 5, water— the bathing is to wash clean the films of hypo—and No. 6, glycerin and water, to render the films pliable in handling. |

Behind the developing room is a large chemical dark room and laboratory, and outside these rooms is the drying hall, where films are reeled off on great seven-foot high wooden drums, which each holds a thousand feet of film. Here there must be no dust, as that would settle on the pictures and look like pieces of coal in magnifying the scenes on a screen. So the advantage of stone floors, walls and ceilings becomes manifest. Even the too high speeding of the rollers is avoided to prevent currents of dust carrying air. |

The drying is followed by careful inspection and brushing off, and then |

(Text box continued on next page)

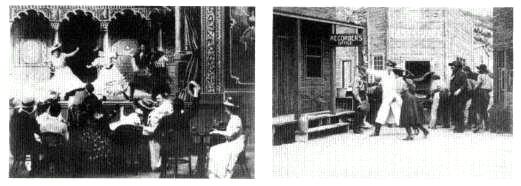

Stage Struck and A Race for Millions.

the films are reeled into their boxes again, ready for shipment to Lewellyn park, where they are developed into positives and prepared for market. |

SOURCE:Film Index , November 28, 1908, p. 4. |

One of Dawley's responsibilities in the new studio was to keep payroll records for actors. These records, as well as some of Dawley's later statements, have led some historians to credit Dawley as author and director of many Edison films of which Porter was in fact producer, (co)scriptwriter, cameraman, editor, and lab technician. While the nature of their collaboration makes attribution of sole authorship inappropriate, Porter retained the dominant role. Dawley was "stage manager" or "stage director" and responsible for blocking and acting. Dawley not only worked under Porter but had little involvement with filmic elements such as camerawork and editing. Porter's former collaboration with McCutcheon provides a comparable model for the relationship between these two men, with one essential difference. In the beginning Dawley was learning about motion pictures and deferred to his studio chief and cameraman more readily than his predecessor. Dawley acknowledged that Porter knew what he wanted, and it was the new employee's job to help him get it. Films such as Rescued from an Eagle's Nest thus continued Porter's previous work in both subject matter and treatment. The two only worked together for a year, after which Dawley was given his own production unit to head. During Dawley's first year, it seems more appropriate to attribute the films that Porter supervised, shot, and edited primarily to the veteran rather than the novice. If this was not the case, Dawley rather than Porter would have taken the blame for the Kinetograph Department's subsequent difficulties.

Stage Struck (July-August 1907) was the first film to be made in the new Edison studio. It starred Herbert Prior as an impoverished thespian who helps three sisters escape the farm for a career on the vaudeville stage. The exteriors

for Stage Struck were shot around New York City—at Coney Island and probably in the Bronx. Two scenes utilized the expanded possibilities offered by the new studio. One set created a concert garden where the thespian and three sisters performed on a substantial stage while the girls' parents sat at a table in the foreground viewing the performance. For another set, a "Human Roulette Wheel" was constructed and used in a chase sequence as the farmer tried to capture his wayward daughters. The wheel was not essential to the story, but Porter could not have filmed this indoor amusement either at Coney Island, where the lighting was inadequate, or in the old studio, which was too small. Porter next used the studio to create a western locale for A Race for Millions (August—September 1907). A car was driven on stage, again something that had been impossible at the old Twenty-first Street rooftop. The studio became a plaything as Porter and his associates explored its many fascinating possibilities.

Once in the new studio, the Kinetograph Department responded to the demand for more films. For the remainder of Porter's tenure, the rate of production increased. In August 1907 the studio staff averaged two films per month; by February and March 1908 they were producing at twice that rate and releasing a new film each week. In some cases, these films were very short. Playmates (February 1908) was only 360 feet long. Within a few months, however, the production staff produced close to a reel of film per week-often of more than one subject. The whole approach to filmmaking shifted. Until February, distribution was determined by the production schedule. When a film was completed, it was readied for release and copies were then sold to the various exchanges. With the release system instituted by the licensees, this arrangement was reversed. The rate of production was dictated not by Porter's needs but by the distribution system.

Dawley's records show that the number of days in active production (for which actors were hired) increased substantially over this period, while the average number of shooting days per film decreased only slightly. Less time was devoted to preproduction, and work on each film became more concentrated. The studio rarely hired players who had other acting commitments during a production. In June 1907 the Edison payroll ledger listed four men as making negative film subjects: Porter at $50 a week, J. Searle Dawley at $40, and William Martinetti and George Stevens at $20 a week each. They were assisted by staff members in other payroll categories, like William Gilroy, who received $15 a week. When the group moved into the new studio, Henry Cronjager was hired at $20 a week as Porter's assistant cameraman.[79] In September Martinetti left and was replaced by the set designer Richard Murphy.[80] With staff size and rate of production moving upward, Porter's salary was raised to $65 a week.

By late 1907 the Kinetograph Department was casting a group of actors with increasing regularity. Receiving $5 a day each, they derived a significant portion of their income from the studio. Edward Boulden appeared in eight films be-

tween September 1907 (Jack the Kisser ) and March 1908 (The Cowboy and the Schoolmarm ), and returned subsequently after a few months' absence. A Mr. Sullivan performed in The Trainer's Daughter (November 1907) and ten other films over the next six months. William Sorelle, who also made his first documented Edison appearance in The Trainer's Daughter , acted in more than twenty films over the next year. John (Jack) Frazer appeared in Stage Struck (July 1907) and then joined the Edison staff in September at $18 a week. His baby daughter Jinnie appeared in The Rivals (August 1907); in her next performance, she was stolen by a mechanical eagle in Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (January 1908). Jinnie Frazer continued to appear in Edison films whenever an infant was needed.

Some of the actors had worked for Porter as early as 1903. Boulden had been the shoe clerk in The Gay Shoe Clerk . Phineas Nairs, who played the detective in The Kleptomaniac (1905), was steadily employed at the Bronx studio after Fireside Reminiscences (January 1908). John Wade, who had been tarred and feathered in The "White Caps " (1905), appeared in Stage Struck and five other Edison films. Gordon Sackville, who had acted for Porter as early as 1904, appeared in Tale the Autumn Leaves Told (March 1908) and Nero and the Burning of Rome (April 1908). He later appeared in Porter's first production for Rex, The Heroine of '76 .[81] Other actors had worked with Dawley in the Spooner Stock Company; among these were Harold Kennedy, Augustus Phillips, and Jessie McAllister. Laura Sawyer, who would become one of Edison's leading players, made her first appearance in Fireside Reminiscences .

A number of actors maintained a loose association with the Edison Company. Kate Bruce appeared in five films over ten months, Miss Francis Sullivan in four, and a Mr. Elaxander in five. Others were associated with the company for two or three films and then moved on, among them D. W. (Lawrence) Griffith. Griffith had been an extra in at least two Biograph films in late 1907 before winning a starring role in Porter's Rescued from an Eagle's Nest . He then worked as an extra at Biograph in mid January before returning to Edison in a similar position for Cupid's Pranks (February 1908).[82] As his connection with Biograph developed and the "film war" heated up, the actor severed his ties with the Edison Company. Herbert Prior appeared in Stage Struck and Nellie, the Pretty Typewriter (February 1908), then moved on to Biograph. He eventually returned to Edison in late 1909 as a full-time stock company actor.[83]

The development of an informal stock company grew naturally out of the increased rate of production and enabled Porter and his colleagues to work with actors who were more or less familiar with Edison procedures and whose abilities were known in advance. Films were no longer treated as discrete, individual productions: there was little time for casting calls. This was only one aspect of the Edison Manufacturing Company's hesitant move toward a studio system. Under Porter, there were some department heads: a prop man, an art director,

The Devil.

and a stage manager in charge of the actors. Yet Porter also retained complete control over photography, editing, and developing—over all the filmic elements. A division of labor was only partially and unevenly instituted. Many of the gains in the rate of production were accomplished not by increased efficiency but by increased personnel. Edison's rising production level, moreover, was only part of a larger phenomenon occurring throughout the industry. This general increase undermined the representational system that had been established in the period before the nickelodeon.