Hotel Homes and Cosmopolitan Diversity

Commercialized hotel life and private household life occupy different positions in regard to several cultural issues: the proper type of household, who should cook the food, how close Americans should live to their neighbors, who (if anyone) should have control and surveillance over an individual's activities, how mixed the land uses adjacent to American homes should be, and how committed Americans should be to private material possessions. These issues cut through all of the several types of hotel life.

Defining the Wide Range of Hotel Life

The diversity of hotel life stems from the diversity of hotel residents, the relative stability of their work, and their income. Recent hotel residents have included people like San Francisco's Cyril Magnin, the wealthy owner of a chain of clothing stores, three-time president of the Chamber of Commerce, and San Francisco's chief of protocol for over twenty years. From 1960 until his death in 1988, Magnin lived in a multiroom suite that occupied the fifteenth floor of a city landmark, the Mark Hopkins Hotel.[3] In Washington, D.C., Lawrence Spivak, longtime moderator of NBC's "Meet the Press," has lived for over thirty years in the Wardman Tower of the Sheraton Washington complex, a large hotel in a single-family neighborhood near Rock Creek Park. Spivak's hotel neighbors have included Dwight Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson, Perle Mesta, Clare Booth Luce, and Herbert Hoover (who also maintained a hotel suite in the Astor Towers of New York's Waldorf-Astoria).[4]

Prestigious addresses, time saved in traveling to work, snob appeal, spectacular views, and having unctuous service without supervising servants are conveniences that keep busy and wealthy residents at exclusive hotels. All this has led Paul Goldberger, the architecture critic

Figure 1.1

The Ritz Tower in New York City in 1926, one year after its

completion. The Ritz has long been a favorite for permanent

guests.

for the New York Times , to write that "the perfect apartment, at least in New York, is probably in a residential hotel" (fig. 1.1).[5] In an expensive hotel, permanent residents usually rent two to seven large rooms, including a kitchen, and in many ways live as they would in an apartment.[6]

Only a tiny fraction of hotel life is so elegant. Dorothy Johnson, a sprightly sixty-five-year-old widow, lives in a single room in a Minneapolis hotel. Like a great number of middle-income people who rent one or two rooms in a decent hotel on a good street, she cooks simple meals on a hot plate in her room and enjoys daily room service, a mod-

erately priced dining room, and several cheap coffee shops close by. "I've sold my car because everything is within walking distance," Dorothy says. "My friends in the hotel and I can look forward to an outing arranged by the staff, or on the spur of the moment we can go shopping, take in a movie, or see a play—all without driving."[7] A significant notch lower on the price scale was the hotel living experience of play-wright Jane Wagner. In 1958, she moved to New York City as a young woman "absolutely alone," as she puts it. For three years Wagner lived in a room at the YWCA. For her it was "the college dormitory she had never stayed in." Wagner's experience is hardly unique. In terms of the number of rooms rented in the 1980s, the YMCAs and YWCAs were the third-largest hotel chain in the world.[8]

As residential hotel prices edge toward the lowest range, the streets and neighborhoods are less safe and less desirable, but the locations are still central. In 1982, a veterans' center poster in San Francisco advertised such a hotel like this:

Rooms for rent. Family atmosphere; clean, freshly painted rooms. Community kitchens; clean sheets once a week. Close to the subway. Only $195.00/month rent.

The advertised building is old; built in 1906, it has forty-nine rooms. The bathrooms are down the hall.[9] In hotels of this price range it is not uncommon to look into a room and see a group of friends and four plates on the bed: a dinner party for four, the host cooking (almost legally) on a camp stove, his spice and pot racks on shelves above. Plants crowd some rooms; books, a television set, and cast-off easy chairs crowd others. On occasion a pet kitten scampers down the hall (fig. 1.2).[10] In 1977, Felix Ayson, a Filipino field worker, explained to reporters that he had lived in such a hotel in San Francisco on and off from 1926 to 1977. "Whenever there was no work in the country, I have come to find a job in the city, and I have lived here. Most of the time in America I have spent in this hotel, so it is my home."[11]

Although their homes are very different, Cyril Magnin, Dorothy Johnson, Jane Wagner, and Felix Ayson all have enjoyed what the law defines as a hotel. Legally, a hotel provides multiunit commercial housing, usually without a private kitchen. More precise definitions are complicated since local ordinances, state statutes, and federal programs

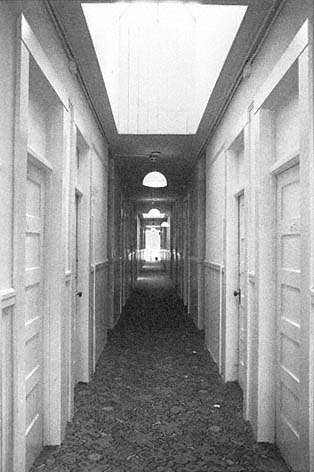

Figure 1.2

A hallway in San Francisco's National Hotel, a large

inexpensive residential hotel which mixes permanent

and transient guests.

set different criteria. Most state codes define a hotel as a commercial operation renting sleeping rooms by the day, week, or month. California's legal definition of 1917, still in force, stipulates that a hotel is "any house or building, or portion thereof, containing six or more guest rooms which are let or hired out to be occupied or are occupied by six or more guests."[12] Depending on the state, the minimum number of rooms in a hotel can vary from three to thirty. Hotel definitions exclude group quarters such as hospitals, jails, and military barracks.

The definition of permanent residence in a hotel (as opposed to being a transient guest) has to do with the length of time one stays. In most states, if a tenant lives in a hotel room for more than a month, that room is then a residential hotel unit, and the person is legally considered a permanent resident of the city. The one-month residency often

Figure 1.3

Two nineteenth-century houses converted to rooming houses, photographed in 1985. In most states

these Lexington, Kentucky, structures would legally qualify as hotels.

applies to apartment dwellers as well and has been a typical residence requirement since the time of the Civil War.[13]

The phrase "boardinghouse reach" comes from an important variant of hotel life. In boardinghouses , tenants rent rooms and the proprietor provides family-style breakfasts and evening dinners in a common dining room. Traditionally, the food was put on the table, and everyone scrambled for the best dishes. Those with a long, fast reach ate best. The term "residential hotel" includes other variations. In private rooming houses (called private lodging houses in some cities), tenants simply rent a room and buy their meals elsewhere. If tenants eat their meals with the family, they are called boarders; if tenants eat elsewhere, they are called roomers or lodgers.[14] If a family rents out many rooms (more than six in California), their boardinghouse crosses over into the definition of a commercial hotel. Commercial boardinghouses and lodging houses are technically open to taxation and inspection as hotels (fig. 1.3).[15] Residential motels, particularly common in resort areas and along bypassed highway routes, operate under the same legal definitions as residential hotels.

The absence of a private kitchen separates hotels from apartments. By 1900, lawyers used the cooking area and the presence of a private bathroom for each unit to distinguish the more socially proper apartment from the less proper tenement. The terms usually stipulate that "families living independently of one another and doing their own cooking" in buildings for three or more households are living in apartments and not in hotels.[16]

Cultural Challenges of Hotel Life

People living in hotels of all types create and support alternatives to traditional household culture.[17] Foremost traits among the distinctions of hotel life are unsupervised individual independence, cosmopolitan mixture, and a life unfettered by place and possessions.

Hotel life offers more individual freedom than any other housing option. Residents in 1870, 1920, and 1980 have all appreciated this characteristic. Without telling anyone in advance, they can dine one night at 8:00 and the next at 5:00 and yet inconvenience no one. In hotels, people on unusual schedules can sleep when tired, awaken when refreshed, eat when hungry, and drink when thirsty.[18] Those few services not available in the hotel can be found within walking distance. Hotel freedoms, however, have never been complete. As in most apartment houses, complete acoustical privacy can be difficult to obtain. One's comings and goings are less controlled than in a family house, but hotel desk clerks take careful note of everyone who passes.[19] However, hotel clerks rarely question the personal life of any guest whose bills are paid and who is not annoying neighbors. In short, hotel life can be virtually untouched by the social contracts and tacit supervision of life found in a family house or apartment unit shared with a group.

Another general ingredient of downtown hotel life is neighborhood mixture—a composite of retail and office activities, production and consumption spheres, many types of recreation, and people who are rich and poor, famous and infamous, married and single, young and old, transient and resident.[20] The term "cosmopolitan" certainly fits these juxtapositions. Active hotel people can feed on the 24-hour stimulation and spontaneity that their choice of residence offers. "You know," one happy hotel dweller affirmed, "I just love to be where there's life and city lights."[21] Downtown hotel life has the promise to be not just urban but urbane.

In another major departure from the typical household culture of the United States, residents of hotels keep themselves freer of material possessions than their suburban counterparts. The absence of household property makes hotel people more obviously mobile than other Americans who move often. Most hotel residents share typical American values, but they do not (or cannot afford to) fasten their identities to the anchor of private property. Even for wealthy hotel residents, a month or a season's lease is the longest financial commitment and tie to their home. They rent their furniture, dishes, and all other aspects of shelter.

Underlying the personal freedom, mixture, and unfettered nature of hotel life is the reality that hotels are blatantly commercial, not in a realm separate from business or manufacturing. Nor has hotel life, especially at the cheaper levels, always been chosen. Within the logic of industrial capitalism—particularly as it matured about the turn of the twentieth century—some employers have relied on a large force of temporary and marginally paid workers. Hotel living helps to make this labor force viable (fig. 1.4). Yet hotels are not always housing of last resort. Studies consistently show that many Americans prefer hotel life over other available and affordable options. Some residents cling to hotel life rather than live with relatives, share an apartment, or (for the elderly) live in a nursing home.[22] Because of public policy and new economic forces, this preference is in a precarious position.