Society and Its Outcasts

Not all Porter/Edison films from this period explored conflicts within the social structure. The staples of the industry in the pre-Griffith period, as today, concentrated on dramatic conflict between constituted society and those living on its fringes or completely outside it. The tramp, a frequent subject of Edison comedies, was one of society's outcasts. While Porter was growing up, tramps were customarily seen as a dangerous menace. As a result of an attempt to control their pilfering, many ended up in the Connellsville town jail.[25] Almost twenty years later, the tramp and his relationship to society were often viewed in more romantic terms.

The nearer these refugees from modern society can approach the habits of their primeval ancestors the greater appears to be their satisfaction. Many of them boast not only that they no longer need to work, but that they can live without begging. They tell you they are perfectly independent of the laws which govern the rest of the world.

. . . Is stealing to the man or boy who has abandoned human society for that of nature a crime? Stealing is the first law of nature by which all animals not subdued by man and all plant life obtain subsistence.[26]

This perception of the tramp's predicament begins to explain his status as the single most popular figure in turn-of-the-century culture. In "Happy Hooligan," "Burglar Bill," "Weary Willie," and dozens of other comic strips, plays, and short films, the tramp is generally portrayed as an annoying, but relatively harmless, scavenger, whose petty thievings and inevitable punishment provide numerous situations for comedy. The ritual beatings he receives at the hands of the law or outraged citizenry humorously define proper society's boundaries in terms of the outcast. They conform to Henri Bergson's assertion that the comic lies in an individual's inability to adapt to society, and that comedy functions as a kind of social ragging.

The Burglar's Slide for Life (March 1905) elaborates on Porter's earlier Pie, Tramp and the Bulldog (1901) as the bulldog protects the home. He is man's (socialized man's) best friend. The tramp burglar, looking for a free lunch, prowls an apartment building. He hides in a vapor bath when the mistress of the house enters the room. Porter's familiar overlapping action is used as the tramp is discovered, flees through a window, and is chased down the clothesline by the family dog (Mannie). In his desperate effort to escape, the fleeing burglar thus mimes a then popular daredevil stunt ("the slide for life"). Reaching the courtyard, he is beaten by other apartment dwellers and bitten by the dog.

The tramp avoids his ritual beating in Poor Algy! (September 1905) by

Poor Algy has in error received the

tramp's customary punishment.

switching clothes with the young lover, Algy. When Algy, dressed as a tramp, tries to approach his girl, she fails to recognize him and retreats. Algy chases after her. The girl soon passes a pugilist doing roadwork for an upcoming fight. He administers the tramp's traditional beating—to poor Algy. Once again Porter played with a well-established genre and its codified relationships between characters: minimal variations gave the piece a freshness not always apparent to present-day viewers.

"Raffles "—the Dog (June 1905) was another Edison comedy involving a thief. The original Raffles started out as a series of short stories by E. W. Hornung about a gentleman safecracker of elderly years who wins readers' amused tolerance more than their condemnation.[27] By June 1905 Raffles had been made into a play and a comic strip. In "Raffles "—the Dog , "Raffles," once again played by Mannie, is a charming, innocent thief directed by conniving masters. After the thieves rob several upright citizens, a chase ensues that concludes with their capture. The dog's asocial behavior is like that of other petty thieves in Edison comedies: the tramps in Poor Algy! and The Burglar's Slide for Life , the juvenile delinquents in The Terrible Kids (1906), and the shiftless "darkies" of The Watermelon Patch (1905).

Porter, like other filmmakers of the pre-1908 period, often portrayed outlaws who threaten society as members of fringe or outcast groups, with such characterization serving as motivation for their illegal activities. This is the case with the racial humor and black stereotyping in Porter and McCutcheon's The Watermelon Patch (October 1905). Their happy-go-lucky thieves, who "seem to think eating watermelon is the only pleasure in the world"[28] are comedic counterparts to the ruthless, scheming lovers of white women in The Clansman. The Watermelon Patch begins as an absurdist comedy: a number of "darkies" steal watermelons and flee, pursued by redneck farmers dressed in skeleton costumes. Losing their pursuers, the darkies reach their destination, where they dance and

The Watermelon Patch. Inside and outside: spatial distortions reduce fun-loving "darkies" to pygmies.

enjoy their watermelon until the rednecks arrive. When the whites board up the exits and seal the chimney, the darkies are soon covered with soot, another racial "joke." (In 1905 many Negro performers still went on stage in black face—as did white actors impersonating blacks. This joke played with the "childish" belief that black skin is black because it is covered with soot.)

In the film's last three shots, Porter alternated exterior and interior scenes using an editorial construction similar to the ending of Life of an American Fireman . After showing the rednecks sealing the chimney, Porter cut to the interior, where the "darkies" hear the intruders, grow quiet, and slowly feel the ill-effects of the smoke. Realizing what is happening, they make their escape. The final shot, once again of the exterior, returns to the moment when the darkies begin to make their escape. It shows them coming out of the house and receiving the blows of the amused rednecks. What is fascinating, both cinematically and perhaps as an example of unconscious racism, is the contrast between the exterior scenes in which the handful of rednecks dwarf the tiny shack and the interior scenes in which the shack comfortably holds twenty "darkies"—reducing them to the size of pygmies.

The Watermelon Patch is as revealing of the state of American cinema in 1905 as it is of American racism. Earlier Edison films depicting African Americans include Chicken Thieves (1897), in which "darkies" raid a chicken coop; Watermelon Eating Contest (1896), a one-shot facial expression film of happy blacks eating watermelon; and The Pickaninnies (1894), showing three Negro youths doing a jig and breakdown. These often-used motifs are integrated into Porter's later film. The dancing and watermelon contest are treated as self-contained scenes, which interrupt the Watermelon Patch narrative. The isolated images of blacks presented in these earlier films are unified and elaborated.

They are superstitious, petty thieves, good dancers, and love watermelon. They like to have a good time, but their inherent laziness must be subsidized by pilfering.[29]

The Watermelon Patch owes much to Biograph's The Chicken Thief (1904), in which darkies steal chickens and bring them home for a party of eating and dancing. On their next outing, the two thieves are chased and caught by angry rednecks.[30] The many parallels between the two films are partially explained by McCutcheon's involvement in both projects. Sigmund Lubin's somewhat later Fun on the Farm (November 1905) makes the lighthearted tone of these two films even more explicit: tarring and leathering the local pumpkin(!) thief is shown to be one of the many amusing ways to pass the time down on the farm. In all these films, whites chasing blacks is shown to be good, clean fun. African Americans are portrayed as childlike and unsocialized. Whites, as responsible members of society, are obliged to chastise them and maintain discipline.

Although many early films (comedies as well as dramas) used made-up whites to play the roles of blacks, the Edison Company assured prospective buyers of The Watermelon Patch that "all the watermelon thieves are genuine negroes."[31] Not surprisingly, this and most other motion pictures did not make a "sure hit" in the black communities. As storefront theaters began to appear across the country in late 1905 and 1906, those intended for black audiences were among the few to fail. According to one amusement manager, "When a negro goes to a show, it pleases him most to see black faces in the performance. But no pictures are made with Senegambian [sic ] faces."[32] The few films that did use black performers must have alienated these audiences even more.

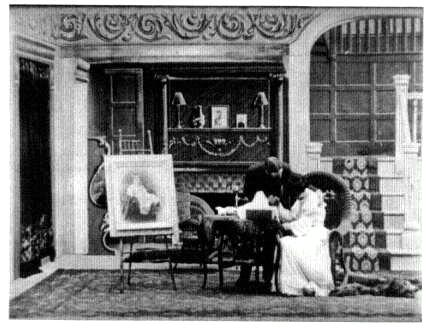

While those outside proper society are undersocialized in Edison comedies; outsiders in Edison dramas are antisocial. They threaten society's very fabric, often by directing their attacks against the family. In Stolen by Gypsies (July 1905), gypsies abduct a well-to-do family's child, who has been left momentarily unattended by a nursemaid. This film belongs to a popular kidnapping genre that emerged in 1904. Porter's first effort was the three-shot Weary Willie Kidnaps a Child (May 1904), but the genre was made popular by such English imports as The Child Stealers (1904).[33] Illustrious examples of this family-centered genre eventually included Cecil Hepworth's Rescued by Rover (1905) and D. W. Griffith's directorial debut, The Adventures of Dollie (1908). All have remarkably similar narratives. A gypsy or some other outcast steals and then abuses the young child of a respectable, upper-middle-class family. The parents experience a range of emotions—anguish, guilt, remorse—over their loss. As in Stolen by Gypsies , the situation is usually more poignant because the victim is an only child. In the inevitable happy ending, the child is rescued and the nuclear family restored.

By October 1904 the genre was well enough established for Biograph to turn

In Stolen By Gypsies, parents mourn the loss of their only child,

whose portrait dominates their home.

it inside out and make a comedy, The Lost Child . When the child disappears into a dog house, the mother assumes the worst and chases an innocent passerby, whom she believes to be the kidnapper. Societal paranoia and the family-centered drama are spoofed, although the irony is softened because the generic form defines it as an amusing exception. For the first half of Stolen by Gypsies , Porter and co-director Wallace McCutcheon, who had been partially responsible for The Lost Child , took the popular Biograph success and gave it another twist. As before, the wrong people are chased. They are no longer innocent pedestrians, however, but chicken thieves. Moreover, the child is actually stolen. Although sometimes humorous, the first part emphasizes the vulnerability of the family to assault. The second returns to the conventional formula: the child is found and reclaimed by the parents, reuniting the family, while the police perform the subsidiary function of backing up their action with force.

Porter considered Stolen by Gypsies an important film and sent the following note to West Orange with the undeveloped negative:

The Train Wreckers. The outlaws capture the switchman's

daughter; later her lover, the engineer, kills her tormentors.

July 6th

Dear Sir:

Am sending you today undeveloped negative complete with announcements of "Stolen by Gypsies". Have made tests of same and found them photographically perfect. In as much as this has been a quite expensive production kindly see that every care is taken with them. Have instructed Mr. Bonine to develop them in "Pyro."

Very truly yours,

E. S. Porter

P.S. Please return negative to me after they are developed and I will trim same and forward to you immediately.[34]

Stolen by Gypsies , shown with Edwin Arden's play Zorah at Proctor's 5th Avenue Theater, was lauded by the New York Sun . The review was promptly reprinted in an Edison ad:

Yesterday between the second and third acts there was a wait of over half an hour, during which the audience was treated to an intensely interesting motion picture drama, entitled "Stolen by Gypsies." There was so much human interest in this little story and its climaxes came so thick and fast, as it followed the child from the moment that it was stolen up to the hour of its rescue a year later in the gypsies' camp that it made "Zorah" by comparison seem rather stilted and stagy.[35]

Despite the praise, the feature sold a modest 59 prints over the next year and a half (compared to the more than 300 copies sold of Hepworth's Rescued by Rover , which was released in the United States at about the same time).

The Train Wreckers (November 1905) includes Porter's most violent expression of the conflict between constituted society and its outsiders. The outlaw band, with its apparently irrational desire to destroy all social order, is finally eliminated by a combined force of railroad personnel and select passengers.

From the Lumières' Train Entering a Station (1895) to Ilya Trauberg's China Express (1929), the train is one of the central iconographic figures in silent cinema, and Porter, perhaps more than anyone, made it so. Trauberg's train is divided into first, second, and third class compartments, with the principal conflict between the workers in third class and the imperialists and their Chinese associates in first. Porter's train has no such differentiation. Although the film's principal characters are skilled members of the working class, the conflict is not between classes or different social groups, but against an external threat, a cause around which society can rally all its members. With order finally restored, a romance between the engineer and the switchman's daughter, introduced at the beginning of the film, resumes. Society is able to return to its proper preoccupations.

The Train Wreckers effectively demonstrates the need for social cohesion in a way that could serve as a prototype for future good-guy-versus-bad-guy conflicts. It was extremely successful, selling 157 prints during 1905-6, and its narrative would be reworked six years later in one of D. W. Griffith's most successful Biograph films, The Girl and Her Trust (released March 28, 1912). Films like The Train Wreckers and Stolen by Gypsies see the social order as continually threatened from without. In articulating this conflict, Porter used the chase as a central narrative strategy: the bulldog chases the tramp down the clotheslines; the rednecks pursue the watermelon thieves; the railroad passengers overtake the train wreckers; and constituted society defeats its enemies. In films where Porter examined the inner workings of society, this is much less likely to be the case.