Initial Film Production

The imminent completion of the kinetoscopes spurred the Edison group into serious film production. Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (© 9 January 1894) was a short film made for publicity purposes during the first week of January 1894.[16] By the beginning of March, Dickson and assistant William Heise had shot The Barbershop and Amateur Gymnast , both full-length subjects. As with most films made during the coming year, these were slightly less than fifty feet long, shot at approximately forty frames per second, and lasted less than twenty seconds. Like Blacksmith Scene, The Barbershop depicts a homosocial environment where easy comradery is routine. A customer receives a "lightning shave" for five cents—the cost of seeing the film. Since the shave and the viewing of the film take the same amount of time, the subject would seem to gently rib the film spectator, who has been quickly separated from his money. Yet the depiction of a complete shaving cycle highlights the work process (the barber's) and treats the barbershop as both a workplace and a place of leisure.

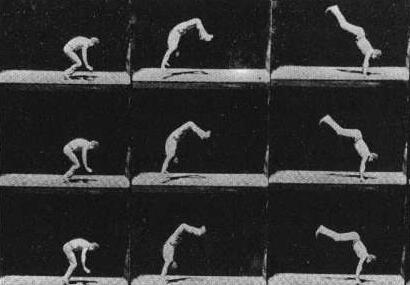

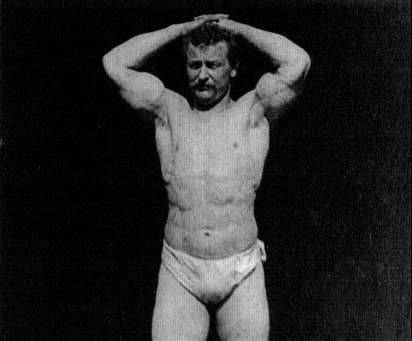

Amateur Gymnast shows a young man performing a somersault: it was probably one of several films taken of members of the Newark Turnverein, a nearby athletic club. Others show two men on parallel bars and a brief boxing match.[17] These may have been rehearsals for the kinetograph's first famous visitor, the strongman Eugene Sandow. On March 6th Sandow came to the Edison laboratory accompanied by the management of Koster & Bial's, the music hall where he was then performing. For the kinetograph, Sandow stripped to a loincloth and assumed an array of positions that showed off his muscular physique. In cinematography as in photography, Dickson had a well-trained eye. His camera framed Sandow just above the knees. Against the black background, the strongman's physique captured the complete attention of his audience.

Making Sandow and other films for this new type of commercial amusement fit easily into the laboratory environment. Although Sandow demanded a $250 fee to pose in the Black Maria unless he could meet Wizard Edison himself, this stipulation was probably unnecessary. Edison, an aficionado of variety entertainment, was delighted to meet the performer. Using a still camera next to the kinetograph, Dickson took several photographs: one caught "Mr. Edison feeling Sandow's muscles with a curiously comical expression on his face."[18] To entertain the inventor, the strongman playfully tossed one of his entourage out the

Amateur Gymnast (1894).

window. The kinetograph added a dash of levity to the laboratory milieu, burdened by discouraging, money-losing efforts in other areas.

The films taken through early March were of men, by men, and principally for men. But this quickly changed. During the second week of that month, the dancer Carmencita pirouetted for the kinetograph—her dress twirling and rising as high as her knees. As the New York Times proclaimed, "the vigor, dash, and sinuous movements of Carmencita herself, having long since defied imitation or improvement, were still indefinable and unique."[19] Unfortunately, the few surviving frames of Carmencita fail even to hint at the reasons for her reputation. Her rise to stardom occurred under Koster & Bial management at their old music hall on Twenty-third Street. There she attracted unprecedented accolades from critics at all the city newspapers. Whatever her actual abilities, like Edison, she was a larger-than-life creation of the mass circulation dailies.[20] She was soon followed by the female contortionist Mme. Ena Bertoldi, then appearing at Koster & Bial's. Both subjects were meant to appeal to male voyeurs who would soon be peeping into Edison's latest novelty. They were films of women, by men and primarily for men. Sandow, Carmencita, and Bertoldi—all headline attractions—were the first of many variety and vaudeville performers to visit the Black Maria over the ensuing year. The most frequent visitor proved to be Carmencita's chief rival, Annabelle Whitford, who performed her Serpentine,

Eugene Sandow.

Sun, and Butterfly dances on numerous occasions between 1894 and 1897. The billowing gauze of her attire was not only sexually evocative but encouraged hand-coloring effects that transcended a strictly masculine appeal. (Hand-coloring work was usually contracted out to the wives of Edison employees, notably the wife of Edmund Kuhn.) However, a large array of dancers came to perform their specialty, including Ruth Dennis (later Ruth St. Denis), who was promoted as "the Champion High Kicker of the World."[21]

These early films functioned within the homosocial amusement world. Cock Fight , shot in early March, was an extremely popular subject, for which new negatives would often have to be made. Filmed as a close view, the intimate depiction of this brutal sport was enhanced by the roosters' rapid movements and flying feathers. Its success generated similar types of subjects.

Through a New York professional rat catcher, Mr. Dickson secured a large cage full of dock rats and he has had at the laboratory for some time two pretty little full-brooded rat terriers. It was an extremely difficult task to arrange the ring, which on account of the limitations of the kinetograph could be only four feet square. The first

Carmencita.

contest was with six rats turned loose in the pit at once, and in fifty-two and one-half seconds all had been killed by one of the terriers. A second and a third trial were made with equally good results.[22]

Rat Catcher , the result of this undertaking, was ultimately considered "not good, the rats being too small."[23]

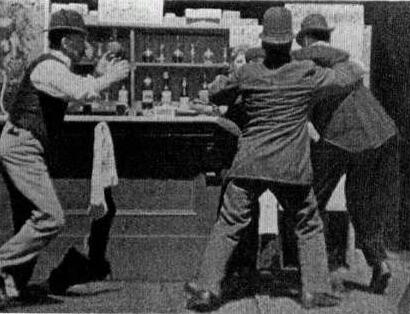

Additional vignettes of masculine daily life also continued to be made. By early April, Dickson had shot Horse Shoeing , a simple variation of Blacksmith Scene . This highly specialized "genre" also included A Bar Room Scene , taken later that spring. Another male-dominated space is depicted, although the emphasis has now clearly shifted toward a distinct leisure realm—from passing the beer bottle in a work context to the saloon. In fact, such all-male environments would frequently support nickel-in-the-slot kinetoscopes in the years ahead. Yet for the first time homosocial space is viewed somewhat critically. Socializing takes the form of a political argument that ends in a fight and requires police intervention. This less than flattering depiction of a saloon suggests a disturbance in the choice and depiction of subjects, a desire to meet the demands (real or imagined) of actual spectators.

The commercial debut of the kinetoscope occurred in mid April with the opening of the first kinetoscope parlor in midtown Manhattan. With a peek costing 5¢ and most patrons expected to see a series of five scenes, viewers had to have disposable income. Most were middle class. At its fashionable location, the kinetoscope drew female as well as male patrons. The masculine appeal needed to be tempered, if not effaced. Three films used for this opening were appropriately desexualized: Highland Dance , showing "A 'Lad' and a 'Lassie' in

A Bar Room Scene.

full costume,"[24]Organ Grinder , and Trained Bears . "The bears were divided between surly discontent and a comfortable desire to follow the bent of their own inclinations," Dickson later reported. "It was only after much persuasion that they could be induced to subserve the interests of science."[25] Made to perform elaborate tricks, the animals evidenced man's mastery of nature while still holding out the potential for violence. Correspondingly, Organ Grinder offered a reassuring picture of a happy, harmless Italian street musician, although the perceived threat of the Italian immigrant could not be totally eliminated. Other films made by early summer—for example, The Boxing Cats, The Wrestling Dog , and Glenroy Brothers (a comic boxing routine)—reversed this tension, displaying physical violence induced in the most domesticated of subjects.[26] These subjects parodied and softened the sporting world's manly preoccupations without in any way criticizing them.

These "non-offensive" subjects not only added to the diversity of available images but became essential when the more provocative selections encountered opposition. That summer, for instance, dancing girl subjects were censored by moralistic officials in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Told to close shop or use more

The first kinetoscope parlor at 1155 Broadway, New York City.

acceptable "views," the local exhibitor acquired a print of The Boxing Cats .[27] Such comparatively tame views, however, were not the most popular. The kinetoscope gave women a more enticing opportunity: to glimpse the half-hidden male-oriented world of cock fights and risqué women from which they were ordinarily excluded. It encouraged a distinctly feminine voyeurism (in some instances complicated by a narcissistic identification with the women on display), a counterpoint to that motivated by masculine desire. Yet despite the various possible subject positions, every film drew from the world of popular amusement. Sex or violence was at the core of almost every image.