11

The Fate of Southern California

The Rise and Fall of Anaheim

A bout the time that Haraszthy migrated to Sonoma an other enterprise began in the south of the state that, in its unlikely origins, its rapid prosperity, and its even more rapid demise, presents a number of points of interest. This was the invention and development of the Anaheim colony, now celebrated as the site of Disneyland but originally a well-planned, well-executed agricultural experiment devoted to the production of grapes and wine.[1]

Its remotest origins were in the operations of the firm of Kohler & Frohling. As soon as the two German musicians began to sell their wine successfully, they saw that they needed a larger supply of grapes than Los Angeles yet afforded; they also saw that the empty spaces of Los Angeles County might be quickly and cheaply developed into vineyards. The catch was to find people willing to do the work; the answer was the German population of San Francisco, a population that Kohler and Frohling, of course, already knew and understood. There was a considerable colony there by 1857, all of them drawn by the Gold Rush. Many of them were now both disenchanted with golden prospects and dissatisfied with crude and violent San Francisco as a place in which to raise families and pursue the life of Gemütlichkeit .

The work of forming an agricultural colony out of these San Francisco Germans was assigned to another German, George Hansen (an Austrian, actually), who had served as deputy surveyor to the county of Los Angeles for six years, knew the region well, and had been in consultation with Kohler and Frohling

77

The seal of the Los Angeles Vineyard Society, formed in 1857 by Germans in

San Francisco to grow grapes and make wine in Anaheim (then still a part of

Los Angeles County). They prospered for the next thirty years, until their

vineyards were destroyed by a mysterious disease. (From Mildred McArthur,

Anaheim: "The Mother Colony " [1959])

about the practicability of their plan from the beginning. In February 1857 Hansen held a meeting with the San Francisco Germans at which the plan was unfolded and the Los Angeles Vineyard Society was formed.[2] The scheme was simple. The society would issue fifty shares at $1,400 each (originally the figure was lower, but this was the sum eventually arrived at); with the capital thus raised, the society would buy land, divide it into twenty-acre parcels, of which eight were to be in vineyard, and assign one to each shareholder. But—and this was the distinctive idea of the whole scheme—before anyone moved onto his property, everything was to be put in readiness. By this arrangement, the participants would avoid the rigors of the first pioneering years and—more important—they could remain at their jobs in San Francisco while they earned the money to pay for their shares. This was capitalism on the installment plan. A down payment would secure a share; with the capital thus generated the work could begin; and the shareholder could stay gainfully employed right where he was until he had paid up his share and the new land was ready for him.[3]

The scheme worked quite well. Hansen was made the general manager for the Vineyard Society and set to work scouting for a property to buy in the southland. His first intention, to buy land along the Los Angeles River, did not work out. Under pressure of the impatience of the society's members, he fell back on the knowledge he had acquired as a county surveyor: in 1855 he had surveyed the Rancho San Juan Cajon de Santa Ana, owned by Juan Ontiveros, lying along the Santa Ana River some twenty miles south of Los Angeles. The grapes of the Santa Ana region had a reputation as the "sweetest and best grapes in the state";[4] whether they deserved that or not (and there cannot have been many vines in the Santa Ana Valley then), the important fact was that Ontiveros was willing to sell to the society. In September 1857 Hansen completed the purchase from Ontiveros of a 1,165 acre tract, with water rights providing for an irrigation canal from the river, some six

78

George Hansen, the Austrian surveyor who purchased the Anaheim property,

built the irrigation works, laid out the site, and planted the vines in readiness for

the arrival of the colonists. (Anaheim Public Library)

miles away. Hansen's first order of business then was to lay out the irrigation sys-tem-the gravity flow from northeast to southwest determined the disposition of the Anaheim streets as they exist today—and to arrange the site for occupation.[5] Within two years, working with a motley crew of Indians and Mexican irregular labor, he had done it: the irrigation channels had been dug, the vines—400,000 Mission cuttings[6] mostly from the vineyards of William Wolfskill in Los Angeles—had been planted, and the whole property surrounded by a fence of 40,000 six-foot willow, alder, and sycamore poles, later to grow into a living hedge as a protection against wild animals and range animals alike. The whole expense of two years' labor of preparation was $60,000.[7] Inevitably, Hansen had to encounter

grumblings from his impatient stockholders, but he seems to have done a remarkably capable job of laying the foundations of a successful agricultural community from scratch on land that was nothing but rough, dry, lonely range in every direction. The little house that Hansen built in 1857 as a place to live and from which to direct the operations of his Indians still stands in Anaheim, now a museum called the Mother Colony House.

In September 1859 the first shareholders arrived to claim their twenty-acre homesteads in the colony that now had a name: Annaheim. The name—soon altered from the German Anna to the Spanish Ana —signifies "home on the Santa Ana River"; it had narrowly beaten out the rival name of "Annagau" by vote of the shareholders in 1858.[8] It is a curious circumstance in the history of a successful winemaking colony that most of the Anaheim colonists—there was but one exception—had not only no experience of winemaking but no farming experience at all. They were small tradesmen, craftsmen, and mechanics. They had only their Germanness in common, and so they present a very different case from the earlier German agricultural colonies—Germantown, Pennsylvania; New Harmony, Indiana; and Hermann, Missouri, are instances—so important in the history of wine in this country. The Anaheimers were of diverse origin: they came from Saxony, Hanover, Schleswig-Holstein, Baden, and elsewhere; they were not co-religionists; and, after the colony's land had been bought, laid out, irrigated, planted, and distributed, they ceased to have any further cooperative arrangement.[9] Each shareholder was an individual proprietor, competing with his neighbors just as much as if he still lived in San Francisco, Los Angeles, or Frankfurt. But there was, nevertheless, an intense spirit of community in Anaheim, given the common nationality, the common enterprise of winegrowing, and the common isolation of life on a raw, remote site.

The reality of life in early Anaheim must have been hard, without much margin or amenity. The site was unattractive, a sandy alluvial fan watered by a thin stream flowing through a shallow ditch; it lay, too, in the path of the dessicating Santa Ana wind of winter, booming down off the high desert through the mountain passes to the ocean and leaving a wake of blown sand and jangled nerves behind it. And it would be years before the work of man could do much to ameliorate the scene. A writer in 1863, one of the shareholders, noted that nearly 600 acres—half of the entire tract—still lay vacant, and yet "the welfare of the vineyards requires that this land should be cultivated, for it is now covered with weeds and brush and is the home of innumerable hares, squirrels, and gophers, which eat the vines, young trees, and grapes."[10]

Even from the very earliest years, however, the accounts of the place tend almost invariably to stress the tranquil, harmonious, pastoral simplicity and fruitfulness of the colonists' life. No doubt the idea of a frontier settlement that combined a real community of language and habits of feeling with the poetic labor of winegrowing made this inevitable. And certainly Anaheim was different from the western model of town life. In any case, to conclude from the language of the many

79

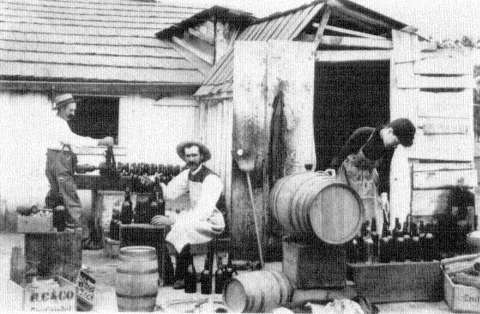

James Bullard, M.D., bottling wine behind his office on Los Angeles Street, Anaheim, c.

1885. Wine was a familiar object throughout Anaheim. (Anaheim Public Library)

newspaper articles generated by curiosity about the Anaheim experiment, all was peaceful and prosperous in the colony: "Their soil is good, their climate, also, their wine is fine, and their tables well supplied" as an envious reporter for the Alta California put it in 1865.[11] Whatever the fantasies about Anaheim, though, the plain fact is that the wine business did succeed, for reasons having perhaps less to do with the quality of the wine or the efficiency of the organization than with the demand for wine on the coast. The wine was made by the various proprietors separately, with the result that Anaheim wine was not a uniform but a highly unpredictable product, at least at first.[12] Later, consolidation and cooperation did come about, but a high level of individualism seems to have persisted to the end.

The wine was not long in acquiring a reputation. The eastern traveller Charles Brace, who did not flatter California wine in general, found Anaheim wine "unusually pleasant and light .... It cannot be stronger than ordinary Rhine wine." He also observed that it was the only wine that could be found throughout the state in 1867: "I found it even in the Sierras, where it was sold at $1.00 a bottle."[13] Much of the crop, too, went to Kohler & Frohling in the early years, as had been the original intention, and their standards certainly helped to establish the reputation of the wine of Anaheim.

There were forty-seven wineries—that is, individual winemaking proprie-

80

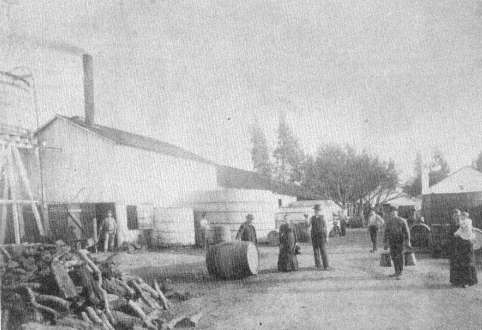

The Dreyfus Winery, Center and East streets, Anaheim, c, 1880. This establishment was

later replaced by a larger winery that never functioned, owing to the death of the vineyards

from the Anaheim disease, (Anaheim Public Library)

tors—in the first decade; two decades later there were fifty, though some of them were by no means small. From a token 2,000 gallons in 1860, the year of the first vintage, production had reached 300,000 gallons in 1864.[14] Twenty years later, at the moment when the Anaheim wine industry was just about to come to its sudden and unforeseen end, production had reached its highest point. Some 1,250,000 gallons of wine were produced by the town in that year, along with 100,000 gallons of Anaheim brandy.[15] In the roster of winery names, German still predominated—Kroeger, Koenig, Langenberger, Zeyn, Lorenz, Reiser, Dreyfus, Korn, Werder—though there were also by that time a Browning Brothers and a Golden Belt Wine Company. Anaheim had also attracted two most unlikely characters, the famous Helena Modjeska, the Polish actress, and a young Polish gentleman later to be quite as famous as the Modjeska, Henryk Sienkiewicz, the author of Quo Vadis . They had come to join a Utopian colony in Anaheim that had only a very brief life, and neither stayed long. Modjeska later bought a summer home in the Santa Ana mountains not far from Anaheim, and Sienkiewicz makes a few references to Anaheim in some of his American sketches, but neither was much taken by the place.[16]

The king of Anaheim winemakers was unquestionably Benjamin Dreyfus, a Bavarian Jew.[17] He was not a member of the San Francisco group that formed the

81

The letterhead of B. Dreyfus & Co., in the year that the vines were being

devastated. Note that the letter is in German. (Anaheim Public Library)

Los Angeles Vineyard Society, but he was a resident of the Anaheim site even before the first shareholders arrived. Dreyfus had opened a store there in 1858 in anticipation of the new community, had welcomed the first settlers to the place, and soon showed that he had gifts as a salesman that were just what was needed by the growers. In 1863 Dreyfus went to San Francisco to manage the depot of the Anaheim Wine Growers' Association (there, incidentally, he made Kosher wine in 1864—perhaps a first for California).[18] Shortly thereafter he opened the firm of B. Dreyfus and Company in New York and San Francisco, through which he sold Anaheim wines. Among his clients was his own winery in Anaheim, supposed at that time to be the largest in the state and using the produce of some 235 acres by 1876.[19] Dreyfus eventually owned properties in Cucamonga, San Gabriel, and the Napa Valley as well as in Anaheim. By the end of the sixties, through Dreyfus and other agents, the city of New York had a wide variety of Anaheim wines available to it: Anaheim hock, claret, port, angelica, sherry, muscatel, sparkling angelica, and brandy are all listed in a promotional pamphlet of the time.[20] The array is striking evidence that the California practice of producing a whole "line" of wine types from one site and from a limited number of grape varieties is no new thing)[21] Dreyfus is said to have made genuine riesling and zinfandel, but the Mission was always the staple grape of Anaheim so long as grapes grew there.[22]

As in the design of a well-made tragic drama, the high point and the collapse of Anaheim winegrowing occurred at the same moment. That was in 1883, when the fifty wineries of Anaheim were yielding their more than a million gallons and when the acreage of vines in the Santa Ana Valley was estimated at 10,000, including substantial plantings for raisins and for table use. In the growing season that year the vineyard workers noticed a new disease among the Mission vines. The leaves looked scalded, in a pattern that moved in waves from the outer edge inwards; the fruit withered without ripening, or, sometimes, it colored prematurely, then turned soft before withering. When a year had passed and the next season had begun, the vines were observed to be late in starting their new growth; when the shoots did appear, they grew slowly and irregularly; then the scalding of the leaves reappeared, the shoots began to die back, and the fruit withered. Without the support of healthy leaves, the root system, too, declined, and in no long time the vine was dead.[23] No one knew what the disease might be, and so no one knew what to do. It seemed to have no relation to soils, or to methods of cultivation, and it was not evidently the work of insects. Not all varieties were equally afflicted, but the disease particularly devastated the Mission, far and away the most extensively planted variety in the vineyards of Anaheim. By 1885, according to one doubtless exaggerated report, half the vines of Anaheim were gone; in the next year, "there was not a vine to be seen."[24] In fact, some vineyards persisted long after this, but the assertion, made by a longtime resident, expresses the sense of sudden, unsparing destruction that the disease created in the Anaheimers as they looked over their blighted vineyards. The official government report estimated the loss to the disease at Anaheim and elsewhere in the Los Angeles region at $10,000,000.[25]

The disease was not confined to Anaheim; much of the San Gabriel Valley and the Los Angeles basin east through Pomona to Riverside and San Bernardino was seriously affected too; the flourishing trade of the San Gabriel region never fully recovered. Anaheim, and the neighboring vineyards of the Santa Ana Valley at Orange and Santa Ana, planted after the success of the Anaheim experiment, were the hardest hit in the midst of the general affliction. The Anaheimers appealed to the state university for expert opinion, and the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners hired a botanist to study the problem. But the disease baffled all inquiry, and meantime its effects were rapid and sure.

In response to repeated appeals, the U.S. Department of Agriculture belatedly sent an investigator to the Santa Ana Valley in 1887; he was puzzled by all that he saw, but reported hopefully that the trouble would "probably disappear as quietly and mysteriously as it came."[26] In 1891 the department sent another investigator, Newton Pierce, whose careful investigation showed that the disease was none of those currently known and that no remedies existed for it. Pierce's reward for his careful and thorough studies was to have the disease named after him. By the time his report was completed, in 1891, the region of Anaheim was reduced to fourteen acres of vines and its identity as a center of winegrowing utterly annihilated.[27] The fate of the bold new winery building that Benjamin Dreyfus, the Anaheim wine

82

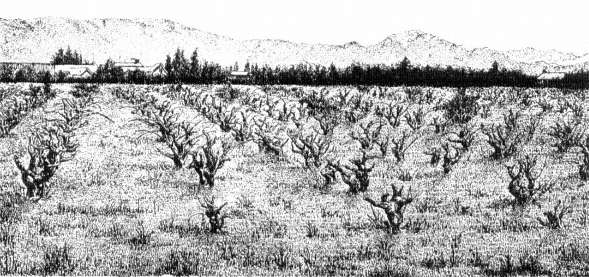

A vineyard of Mission grapes in LOS Angeles County killed by the Anaheim disease. The vines,

planted more than twenty-five years earlier, were dead by 1890, when the picture was made. Mission

vines were peculiarly susceptible to the disease, but all were vulnerable. (From Newton B. Pierce,

The California Vine Disease [1892])

king, had erected in 1884 is symbolic. This was an imposing stone building, far larger than anything else of the kind in the area, but when it was completed and ready to receive a vintage, there was no vintage to receive. The building thereafter passed through various humiliating roles as a warehouse, as a factory for chicken-feeding equipment, even as a winter quarters for a circus. When the freeway went through in the 1960s, part of the building was lopped off by the right of way, it was at last put out of its long agony by demolition in i973.[28]

Anaheim recovered from the disease by turning to the new crops that were just at that time rapidly developing in southern California, especially oranges and walnuts. The Germans of Anaheim had long since set up breweries, and these, of course, were unaffected by the grape disease. So the settlement, which became otherwise indistinguishable from its neighboring communities in making its living from tree crops, still managed to enjoy some notoriety for its beer, its beer gardens, and its beer drinkers. These gave a welcome scandal to their Orange County neighbors, who would otherwise have had little diversion in their rural lives.

What was the Anaheim disease? The plant pathologists have not yet arrived at satisfying answers, but they have continued to study the question because the disease still exists and still threatens California vineyards. In quite recent years, it has been established that the carrier of the disease is a leafhopper, and that the pathogen, as Pierce suspected, but could not prove, is a bacterium. It is also known that the incidence of the disease varies with the populations of its leafhopper carrier, so

that wet years favor it, and sites having abundant weedy and bushy growth surrounding them are vulnerable—both circumstances mean more leafhoppers and so more danger of infection. So far, the only known effective treatment is to pull the infected vines and to start with others, hoping to keep them free of infection.[29] The University of California at Davis is carrying on work to develop a vine specifically resistant to Pierce's Disease by modern means of genetic manipulation, but success has yet to be achieved.[30]

One other thing is known: that the home of the disease in this country (to which it seems so far confined) is in the states bordering on the Gulf of Mexico. The native grapes of that region are the only ones to show any power of resistance to it, and the presence of the disease there doubtless helps to explain why the repeated trials of grape growing in that region met with such poor success. There are abundant other reasons for that result, of course, but the potent destructiveness of Pierce's Disease was certainly a factor in the deaths of any vines brought in from the outside.[31]

The San Gabriel Valley

Even before the Anaheim colony had been planted in the late 1850s, another section of the Los Angeles region was beginning to develop as a major winegrowing area: the San Gabriel Valley, immediately to the east of Los Angeles, stretching for forty or fifty miles. The San Gabriel Mission had originally presided over the territory, and it was the old mission vineyards that gave the idea to later proprietors that winegrowing belonged to their land. This third division of the southern California vineyard, though earlier in its beginnings than Anaheim, reached its heyday a bit later; dominated by ambitious, large-scale proprietors, its spacious ranchos, sprawled over the slopes of the San Gabriel mountains, made it the most splendid of winegrowing regions.

The lines of descent from the mission fathers may be traced through Hugo Reid, a Scotsman who drifted to California, married an Indian woman, and, through his wife, became possessed of the 8,500 acres of the Santa Anita Rancho, once the property of the San Gabriel Mission. Grapes still grew there, and Reid gave some attention to them; by 1841 he had a walled vineyard of 22,000 vines at Santa Anita and boasted, "I consider myself a first-rate wine maker."[32] Reid also owned a small property of some 128 acres, called La Huerta de Cuati, just to the west of his Santa Anita Rancho, and this formed the next step in the growth of San Gabriel Valley vineyards. While Reid lay on his deathbed in 1852, the Huerta de Cuati was bought by Benjamin D. Wilson, who renamed the property "Lake Vineyard," after the shallow lake that lay there, where the Franciscans had built a dam to run a mill and to supply water to the Mission San Gabriel.[33] Here Wilson began one of the most successful of southern California winegrowing enterprises.

Wilson was a model instance of the sort of versatility and mobility that went

83

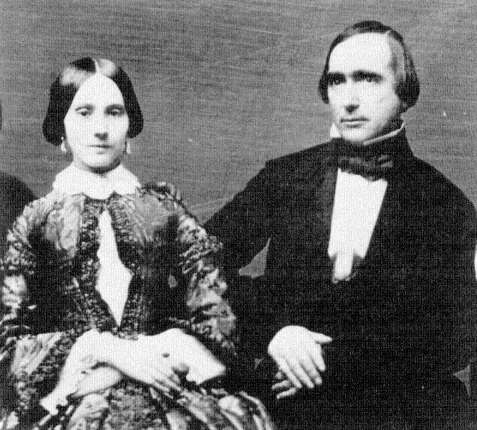

Benjamin Wilson (1811-78), of the Lake Vineyard, Pasadena, with his second wife, probably around 1860.

After a commercial and political career in Los Angeles beginning in 1841, Wilson settled in the San Gabriel

Valley and helped to make it the leading wine region of the state in direct succession to the work of

Mission San Gabriel. (Huntington Library)

with being a California pioneer.[34] A Tennessean by birth, he had been a New Mexico trader before pushing on to California in 1841. There he had married a Mexican wife and had begun to acquire land—at various times he held the Rancho Jurupa, now the city of Riverside; the Rancho San Pedro, now the site of Wilmington and San Pedro; the Rancho San Jose, where Westwood and UCLA now stand; and, finally, the properties now occupied by modern Pasadena, South Pasadena, San Marino, Alhambra, and San Gabriel! He prospered by running cattle, by keeping a store and lending money, and by acquiring ever more land. Wilson may be tracked all over the Los Angeles region: he was one of the party whose exploits in lassoing bears gave its name to Big Bear Lake; he had a rather unheroic part in the Mexican War, and was briefly a prisoner at Chino; he was, after the war, the first Anglo

mayor of Los Angeles, where he had a vineyard on Alameda Street; he built a trail up the high peak behind his San Pascual ranch in order to bring out the timber there, and so that landmark is now called Mount Wilson. One may add that he was twice a member of the state senate, that he went to Washington to lobby for a railroad in southern California, and that he helped to promote the building of Los Angeles harbor. But for us his interest is as a winegrower.

Wilson, despite his long years in Los Angeles, remained a thorough southerner in style, always wearing the white linen collar, ruffled shirt front, and flowing black tie of the plantation gentleman.[35] Despite the expansiveness of his sartorial style and of his hospitality at Lake Vineyard, from his correspondence Wilson appears to have been an undemonstrative, reserved, perhaps slightly melancholy, man. But he nourished a strong passion for his Lake Vineyard. By the time that he bought it, he was wealthy enough to move back east and to live there in style, as some of his friends urged him to do. His new property decided him to stay: he built an adobe house there, and moved in permanently in 1856; the Lake Vineyard, he said, was "the prettiest and healthiest place in California."[36] He planted fruit of all kinds, especially large groves of oranges; he brought in water, planted ornamental trees, laid out avenues, and so adorned the property that it quickly became the unrivalled showplace of the region: no visit to Los Angeles was complete without a visit to Wilson and his Lake Vineyard.[37]

Vines were already on the property when Wilson took over: his granddaughter remembered the original Mission vines there as having trunks six feet high before they succumbed to the Anaheim disease in the eighties and nineties; they may have been planted as early as 1815, for the Lake Vineyard in 1876 was thought to contain vines as much as sixty years old.[38] Wilson went beyond the inheritance of Mission vines, however, and made continuing experiments with new and superior varieties in the hope of discovering what the region would yield best.[39] He also experimented with different wine types; he has the credit, for example, of having made the first sparkling wine in California, though this was a severely limited success.[40] In 1856, the year after the sparkling wine had been created, Dr. H. R. Myles, Wilson's partner in the Lake Vineyard wine business (he had a nearby vineyard of his own), wrote to Wilson that the "old man" who was their champagne master "has been pottering at the sparkling wine ever since you left . . . . The truth is he never will make anything of it . . . . I believe him to be a humbug ."[41] The old man thereafter disappears from the record, and the making of sparkling wine was pretty soon recognized to be one of the things that southern California was not destined to do well.

Wilson also had some local hazards to deal with: the vintage of 1856, over 12,000 gallons, had not yet fallen clear by January 1857. The reason, Myles suggested, was at least in part that they had had "about fifty earth-quakes in the last two weeks, three of which rocked the house very much" and had stirred up all the sediment in the wine;[42] one recalls that the San Gabriel River, which drains the valley, had originally been named the Rio de Ternblores by the Spaniards—the River of Earthquakes.

The unsatisfactory old man's replacement was a Swiss named Adolf Eberhart, who came in 1857;[43] after that, things went better. Wilson continued to acquire land and to plant grapes, so that in a few years he was in a position to seek markets wherever he could find them. His vineyards exceeded 100 acres in 1861, and he was then still adding to them. By 1862 Wilson had a San Francisco agent, who, in addition to supplying the trade in that city, was able to add the exotic touch of a shipment of twenty-five cases to Japan only eight years after that country had been "opened" to foreign trade.[44] More significant was the trade opened with the East Coast; the Sainsevains and Kohler & Frohling had made the first contact between California and the East about 1860. Wilson was not far behind. In 1863 his San Francisco agent shipped fifteen pipes of white wine, sixteen of port, and twenty-one of angelica to Boston; the speculation evidently paid, for Wilson continued to send wine to that city. But the trade was not without its difficulties. As Mr. Hobbs, the agent, complained to Wilson in July 1863, the Bostonians were so accustomed to adulterated wine they no longer believed in the possibility of anything else; in consequence they mostly drank whiskey.[45] Yet if Boston found it hard to accept unadulterated wine, other places found the problem reversed. In St. Louis, in 1866, the local horticultural society, after sampling five different Lake Vineyard wines, pronounced them all "doctored" and unfit to recommend.[46] It is hard to know what the truth was: were the wines pure and thus unaccustomed, as was said in Boston? or adulterated, and thus unpleasant, as was said in St. Louis?

Still, during these years of the Civil War the reputation of Wilson's wines gradually grew both in and out of California; in 1863 two gentlemen from Chicago proposed to set up in the wine business in that city with wine supplied by Wilson because, as they said, "your wines are far superior to those of old Nich. Longworth of Cincinnati";[47] and from his San Francisco agents Wilson heard that his only competition there was from the other Los Angeles producers, Kohler & Frohling and the Sainsevains, because, they reported, "the Anaheim and Sonoma wines are not as good as the wine from Los Angeles."[48] By 1865 the San Francisco trade was large enough to make the old commission agency arrangement no longer satisfactory, and Wilson accordingly set up his own firm in that city.

Like his near neighbors in Los Angeles and in Anaheim, Wilson produced a variety of wines from a variety of grapes: early records show, in addition to the standard Missions, such varieties as Carignane, Zinfandel, Grenache, Mataro, Trousseau, Burger, and Folle Blanche.[49] It was already recognized that the dry light table wines from the Zinfandel and the white wine varieties grown in Los Angeles County were not so good as those produced in more northern regions, and from an early time there was a considerable trade in buying such wines in bulk from northern sources for resale. Sweet, fortified wines—port, angelica, and sherry especially—quickly became and remained the characteristic product of the Lake Vineyard; brandy, too, became increasingly important. But table wines, more white than red, did continue to be produced, even if in less quantity than the dessert wines.

The vicissitudes of commerce began to wear on Wilson as his business grew larger: wines were spoiled in the shipping; agents often adulterated what was sent

to them pure; the American public went on preferring whiskey; competitors undersold one with inferior products; competent help was hard to find and harder to keep; and, in short, Wilson began to think that making and selling wine from the "prettiest place in California" was more trouble than it was worth. Just when he began to weary of the trade, Wilson acquired an energetic son-in-law, who quickly took over the business and was later to lead it through a major transformation. This was a young man named James De Barth Shorb, a native of Maryland, who had come to California in 1863 at the age of eighteen looking for oil in Ventura County. He had soon turned to other things, and had taken his first step towards the considerable prosperity he later enjoyed for a time by marrying Benjamin Wilson's daughter Sue in 1867. The history of the Lake Vineyard under Shorb, though it takes us into another era, is so clear an illustration of the opportunities and disasters of California winegrowing in the later nineteenth century that it will be instructive to tell it here.[50]

Shorb had many of the qualities of the southerner; he talked and wrote fluently and flamboyantly, was quick to take offense, exuded confidence, and loved to promote large but untried enterprises. He was as well a splendid host, a prominent Catholic layman (he now lies buried in the small, select cemetery of the San Gabriel Mission), and the father of eleven children. The undefined and expansive character of California exactly suited him: as he was able to boast in 1888 to the reporter sent round by the historian H. H. Bancroft to record Shorb's impressions for posterity, he had come to California with $700 in his pocket and was now worth from one and a half to two million dollars.[51] Once established as heir presumptive to the Wilson property (Wilson's only son John was a ne'er-do-well who committed suicide in Los Angeles in 1870), Shorb wasted no time in setting to work. With a San Francisco partner, he leased all of the Lake Vineyard and its cellars under the name of B. D. Wilson and Co., his father-in-law lending only his name to the firm. That was in 1867, when, for purposes of the lease, an inventory was made; in this we learn that in addition to a copper still, large iron screw press, grape crusher, and such impedimenta as funnels, wine baskets, measures, dippers, syphons, hoses, bungs, bottles, and boxes, Wilson had thirty tanks of 1,500 to 2,000 gallons' capacity each at the Lake Vineyard.[52] From this it appears that Wilson operated with a storage capacity of, say, about 50,000 gallons. Within fifteen years, Shorb was building a winery of 1,250,000 gallons' capacity.

At first, Shorb took over personal direction of the firm's San Francisco agency. where, he informed his father-in-law, in one year he would "sell more wine than the whole of them put together."[53] But the expansion of the enterprise soon brought Shorb back to the Lake Vineyard, where new vineyards were being planted and large additions made to the cellars. Another novelty for which Shorb was responsible was the introduction of Chinese laborers in 1869: they had not before beer used in southern California. As Shorb wrote in 1870, the experiment was a great success: he thought the Chinese "a more intelligent class of labor" than "the old Mission Indians or Sonorans from Mexico," and found that they could be safely trusted to work alone after only a few days' instruction.[54]

84

A label from the Wilson vineyard in the era of Wilson's son-in-law J. De Barth Shorb, some time

after 1867, when Wilson's Lake Vineyard wines were sold under the name of B. D. Wilson & Co,

(Huntington Library)

The example of Wilson and of Shorb had its effect on their neighbors, more and more of whom planted vineyards and sold their grapes to Shorb or to the wineries of Los Angeles. The San Gabriel Valley was becoming the most extensive vineyard of the state. General George Stoneman, former governor of California, was perhaps the most eminent among the new vineyardists of the region stretching from Pasadena to the east, but he was only one of many who laid out vineyards in the 1870s there: Colonel Edward Kewen, General Volney Howard, Michael White, Alfred Chapman, and John Woodworth may be named among others.[55]

By 1875 Shorb was boasting that "we are the largest wine manufacturers on the Pacific Coast": average production of the Lake Vineyard was 150,000 gallons of wine annually, and 116,000 gallons of brandy.[56] Despite Shorb's expansive optimism, there were inevitable difficulties in selling California wine, the greatest of which was to obtain responsible and intelligent agents who would follow honest

practices in the struggle to educate a recalcitrant American public to the virtues of wine from California. As Shorb reported from New York City in 1869 about the firm's agents there:

They have a double fight before them: first to introduce a new article which all importers are fighting against, and secondly to remove the bad effects and strong prejudice against all California wines, created by the horrible stuff offered here as California wines on this market. Out of one hundred and ten dealers in Cal wines on this market alone, there are but four or five who ever buy a gallon—they manufacture it here in their cellars.[57]

The invoice book of B. D. Wilson and Co. for the five years 1873-78 shows that Shorb was trying to develop markets here and abroad, but with somewhat irregular and dissatisfying results. There are sizeable shipments to the firm's agents in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, though the New York agency seems to be frequently changed: Wilson, Morrow, and Chamberlin give way to B. Dreyfus, then to J. F. Carr, and then to J. H. Smith's Sons. One may guess at some of the troubles implied by this sequence from Shorb's exasperated outburst to a correspondent who offered to do business with him: "My strong predilection," Shorb wrote, "even in business is to deal with gentlemen, and God knows our wine business has been handled almost exclusively by another class."[58] Lake Vineyard wines were also regularly shipped to Cleveland, and, less regularly and in smaller quantities, to Baltimore (the Baltimore agent did not pay his bills), Wilmington, Detroit, and a scattering of smaller places. More interesting are the records of efforts to open a foreign market. Early in his career, Shorb had seemed confident of establishing a large trade in South America and Mexico.[59] Nothing seems to have been achieved in that direction, however. In 1876 Shorb shipped eight barrels of wine and brandy to a William Houston of England; probably these were samples of the winery's whole range. In the same year fifteen barrels went to A. C. Jeffrey of Liverpool. There is no record of repeat orders. Before the shortages and fears created by the onslaught of phylloxera in Europe, England was not ready for California wine.

Yet another market that Shorb sought to develop was that for altar wine; he had an advantage here, being Catholic, and so particularly eligible for recommendation by the church. "We are getting up a circular," he wrote to his New York agent in 1875, "intending to attract the attention of the Catholic trade to our wines for 'Altar purposes,' and will have certificates from the Bishop [of Los Angeles] accompany the same. This trade will consume all our white wines at high prices if it can be secured. Your firm will have a 'lift' in the circular." The "communion wine," he wrote again, "is the dry Lake Vineyard or Mound Vineyard white wine—and be careful to offer none other."[60]

In Shorb's opinion, the wines of the Lake Vineyard were the best in the state, and so the best in the country: "We make the best wines of California," he wrote in 1872, "and we only ask of the trade that they compare our wines with others to

satisfy themselves."[61] The profits of the business were low, however, and from time to time Shorb would determine to sell out and occupy himself with other things—real estate, for choice. In 1875 he unsuccessfully sought a buyer, on almost any terms, for the firm's entire inventory—some 80,000 gallons of wine and 7,000 gallons of brandy, besides about 30,000 gallons on hand in New York—explaining that "my time is too much occupied to give that attention required to successfully prosecute the business."[62]

It is certainly true that Shorb had plenty of other things he might do. In 1873 he and Wilson had formed a new partnership, under the old name of B. D. Wilson and Co., to carry out livestock and grain-growing operations as well as those of the Lake Vineyard and Winery.[63] And that was only a beginning for Shorb. The Wilson property also included extensive orange and lemon groves, whose produce was shipped widely under Shorb's management. Shorb was also preparing for his later extensive dealings in real estate development by establishing land and water companies and building irrigation systems in the San Gabriel Valley and elsewhere. He was interested in mining in the Mojave; in a furniture factory at Wilmington; in water and land development in the Arizona territory; in railways; in electric power; and in exploiting patents for everything from arc lamps to milling machinery and cable car systems. Nor did he neglect Democratic politics at the local and state levels.

In 1877, on property from his father-in-law, Shorb gave expression to his civic and commercial importance by building the big house, rich with carpenter's ornaments, called "San Marino" after the estate of the same name that had belonged to his grandfather in the Catoctin mountains of Maryland. As Wilson's Lake Vineyard had been before it, San Marino became the showplace of the Los Angeles region, a center of lavish hospitality, the place that every visitor had to see and where every transient dignitary might expect to be entertained. After Shorb's death, the house was bought by Henry Huntington, who razed it and built on the site his own mansion, now the Huntington Art Gallery. Few visitors to that lovely place know that it stands where once the leader of southern California viticulture lived, and that all around them once spread the vineyards of the San Gabriel Valley.

Benjamin Wilson died early in 1878, and though he had long before ceased to have any active part in the wine firm bearing his name, his death seems to have been a signal for it to go dormant for a time. The winery and vineyards remained, of course, but the wine company withdrew from the public marketplace. Instead, Shorb sold his production in bulk to the San Francisco firm of Lachman & Jacobi for a couple of years, and then to Benjamin Dreyfus.[64] But the quiet life of a bulk wine producer was not enough to satisfy the ambitious Shorb, and he soon began to develop plans for a new enterprise on a scale not yet attempted in California.

The second phase of Shorb's winegrowing career, which saw the Lake Vineyard transformed into something very different, opened in 1882 with the formation of the San Gabriel Wine Company, capitalized at $500,000, and financed, in large part, by English investors;[65] prominent and moneyed Californians were in on it

85

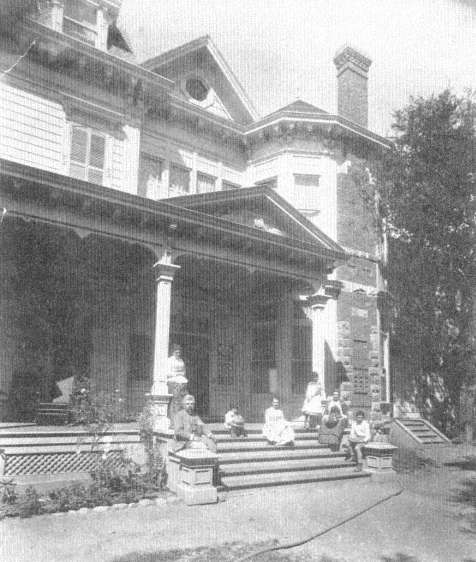

J. De Barth Shorb on the steps of San Marino with a part of his large family. The picture is

probably from the 1880s, when Shorb had established his San Gabriel Winery and hoped

to flood the markets of Europe with the wine of southern California, The site where the

house stood is now occupied by the Henry E, Huntington Art Gallery, (Huntington Library)

86

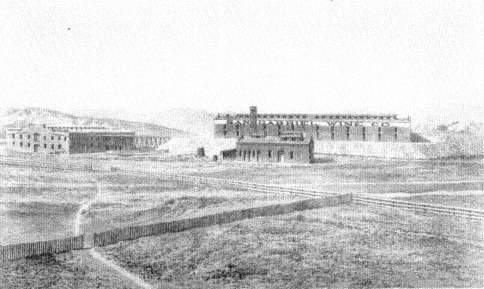

A view of the San Gabriel Wine Company, "the largest in the world," begun in 1882 at Alhambra,

California, between Los Angeles and San Gabriel. With the backing of English investors, the winery,

designed for a capacity of over a million gallons, was intended to put California wines into the world

market as European production collapsed through the ravages of the phylloxera. (From Norman W.

Griswold, Beauties of California [1884])

too, notably the Los Angeles banker Isaias Hellman and a group of San Franciscans including Senator F. G. Newlands and Senator William Gwin. Their intentions were, to put it mildly, grand beyond precedent. It had long been thought "by persons interested in the manufacture of American wine," a prospectus statement ran, that California could compete in the world wine market, given enough capital and intelligence: "This Anglo-American enterprise is the first of its kind which seems to us to have been undertaken on a scale of sufficient magnitude and under all other conditions to solve, exhaustively, the problem of California wine-making."[66]

What can have attracted this kind of interest in the provincial winegrowing industry of a country that did not yet drink wine? The answer lies in the scourge of phylloxera, which was then at the very highest pitch of its destruction of the vineyards of Europe.[67] It did not, at that time, seem an alarmist notion, but rather the sober judgment of informed observers, that Europe would soon be unable to supply its own demand for wine. If wine was going to be produced, it would have to come from unspoiled new sources—California prominent among them. Against this almost surefire prospect of immediate profits, Shorb promoted his San Gabriel Winery. He had another attraction to offer as well: land. Southern California was ripe for development; the railroad from the East would soon run through the San

Gabriel Valley; the nation at large was beginning to grow aware of the Southland's golden climate; the future was immense. The old ranch property accumulated by Ben Wilson would soon be valuable real estate. And so the San Gabriel Wine Company was launched on Shorb's land at the same time that the town of Alhambra, in which it stood, was being invented and promoted by Shorb. Stockholders had shares in land as well as in the company, and dividends could be provided by land sales if, by any unlikely chance, the wine trade should prove insufficient to provide them.

The San Gabriel Wine Company itself owned 1,500 acres; 200 of these were planted to vines in 1883, a further 400 in 1884—or that, at least, was what one prospectus stated. A further 400 were planned for 1885.[68] As for the winery itself, that was planned on an unprecedented scale. The buildings, costing $125,000, were to provide a winery meant to be, quite simply, "the largest in the world." The fermenting capacity was a million gallons, the storage, a million and a quarter.[69] Some of the stockholders expressed doubts about beginning on so grand a scale, but Shorb was confident and swept aside such timid hesitations. The winery, brick-built and steam-powered, duly arose in the new town of Alhambra according to the original plan.

The San Gabriel Wine Company did not need to wait for the growth of its own vineyards before it began to make wine: grapes were available from the many vineyards already established all the way from Los Angeles to the foothills above San Bernardino, many miles to the east. The company was able, thus, to crush some 2,000 tons of grapes in the vintage of 1882 and a larger quantity the next year; the plan was to hold back sales until 1885, when the wine would be ready for market.[70] Shipments began as early as 1884, however, by which time the company had chosen agents for its wine in New York. Problems began at once. It was all very well to grow grapes and make wine in the rural simplicity of Los Angeles County, but once the wine left the hands of the producer no one could tell what might happen. After a visit late in 1884 to their New York agents, Evan Coleman, one of the San Francisco investors, wrote to Shorb that "the more I see of the wine business the less I like it; it seems impossible to do an honest, straightforward business and compete with others, all of whom are lying, adulterating, etc., etc." The agents, in turn, were dissatisfied with what was sent to them: "They have many complaints about the Co.'s wines," Coleman reported, "and doubt that Watkins, the wine-maker, is competent."[71]

Such complaints persisted long after changes had been made and experience accumulated. The port wine produced at San Gabriel, a staple of the winery's trade, gave persistent trouble: it was "nothing but trash," wrote one Philadelphia merchant. "I would not give it away much less sell it to my customers."[72] The stuff spoiled during the long rail journey through the southwestern deserts and across the midwestern plains. Appeals to the University of California for analyses and remedies did not much help, but the addition of cherry juice seemed to turn the trick, and so shipments of cherry juice (so-called; in fact not juice but highly alco-

holic cordial) were discreetly made to the San Gabriel Wine Company in wine puncheons ("by this means we can avoid advertising the fact that we use it," the plant manager wrote to Shorb).[73] Capable help was hard to find; and even the design of the splendid new buildings created difficulties: an expert from the university concluded that the winery was too dry, so that evaporation losses were excessive and the wines did not develop well, while the storage building was too hot. Shorb had had in mind the example of the great above-ground bodegas of the sherry region in Spain in designing it, but, as the expert dryly noted, if you wanted to get the results that the Spaniards got, you had to build like them.[74] No wonder that, in the face of all these troubles, the temptation to cheat was powerful. "If we have to go into the 'doctoring' business in order to meet the market," the secretary of the company wrote Shorb, "can we not find some book that will give us the necessary formulae and suggestions so as to avoid the delay and expense of experiments?"[75]

Shorb was full of resource and suggestion in the face of all difficulties. A key possibility, one that had been part of the original idea in founding the new winery, was the development of foreign markets. This proved harder in practice than in theory, but not for lack of trying. It was evident, for one thing, that they could not send anything less than their best to new markets if they hoped to succeed, and so it was necessary to wait until they had properly made and properly aged stocks. A start was made by sending angelica to Canada; France was considered that year, but the idea was not acted on.[76] France, in fact, was never a market for California wines, despite the possibilities that the phylloxera had seemed to open. The French preferred to buy American rootstocks on which to reestablish their own vineyards. England was more accessible; by 1891 the company's London agent was writing that "California wines are becoming quite the rage here and I hope in a few years time to make a very large business indeed in them."[77] By that time, however, the company's prolonged financial illness made "a few years" too long to wait.

The cost of transport from the West Coast to Europe was a major obstacle, and a splendidly simple way of getting around it seemed to be discovered in 1886. This was by the method of concentrating the must, or unfermented juice of the grape, for shipment to foreign parts, where, upon the addition of water, it could be fermented into wine. Since concentrating the must got rid of the water, the product was economical to ship; and since it had not been fermented at the time of its importation, it avoided the duties upon alcohol. Here, it seemed, was the solution to the problem of finding an export market for the product of California's grapes.

The technology of the process had been developed by a German named Dr. F. Springmuhl, and its promotion was in the hands of a San Francisco German, Paul Oeker. Shorb was soon interested in their propositions, and by early 1887 the American Concentrated Must Company of Clairville, California, J. De Barth Shorb, president, was incorporated and awaiting the next vintage. England was to be the main target—the English already had (and still have) a trade in "British wines," which is to say, wines fermented in England from musts brought in from the Mediterranean or other regions of the grape-growing world. They were thus

familiar with the product and could also provide a source of experienced labor. All that was necessary was to persuade the market of the superiority of the raw material from California. An agent was despatched to London to watch over the business at that end (from the charming address of 10, Camomile Street); at the California end, Shorb was busy signing up growers to supply his vacuum condensers. This was a period of deep commercial depression in the California wine trade, so that Shorb had no trouble in finding interested growers: they included Charles Krug, of Napa, Leland Stanford and his Vina Winery in Tehama County, the Italian Swiss Colony of Asti, and Kohler & Frohling.[78]

Dr. Springmuhl went to London to supervise the crucial operation of fermenting the condensed must into wine, and then the troubles of the new company began to mount even before operations properly began. The process seems to have worked all right, but Springmuhl was contentious and litigious, and his principals back in California did not trust him. The quarrel was at last smoothed over: Springmuhl remained to supervise the technical operation, while a new manager was set up and the name of the firm changed to the California Produce Company in 1888.[79] Still, the business did not prosper under these new arrangements. Five years after the company had been formed, one of the chief investors wrote that "the Must business . . . is the d-dest most disagreeable thing any of us ever encountered," and that the only thing to be done was to get rid of it to anybody on any terms.[80] So ended this early phase of California's struggle to find a footing in the international export market.

Things were not much better with the parent enterprise, the San Gabriel Wine Company. From the outset it had never had quite enough money to operate easily, for the capital stock was never fully subscribed, and in order to meet its needs it had to depend more and more upon the sale of its lands. The boom year of 1887, when land was eagerly sought by speculators, was fairly easy for the company. But the boom died as quickly as it had come, and year followed year not only without dividends but with a growing indebtedness weighing on the company. As early as 1884, one major investor had come to the conclusion that "a great mistake was made in the beginning in building on such a grand scale. We should have built a winery and cellars of not over one half the capacity of that constructed and had $40,000 more by that means on hand, instead of in buildings which we cannot use to their full capacity for ten years to come."[81] Sales of the company's wines in 1886 amounted to $94,000; in 1888 they had risen to $114,000. Early in that year, after the company had shipped twenty cars of wine to the East in March, the manager reported that "everything is going along nicely."[82] At that moment, when at last the prospects began to look good, the Anaheim disease hit the San Gabriel region, and though its effects do not seem to have been catastrophic, as they were around Anaheim, they added just enough weight to the San Gabriel Wine Company's burden to put a stop to its progress.

"But for that fatal disease the outlook for the future would be good," Evan Coleman, one of the investors closest to the operation of the company, wrote in

September 1888.[83] But if Coleman seemed to despair, Shorb, as always, was quick to take action in response to the new problem. Quite improbably, he was able to find in Los Angeles an Englishman with the resonant name of Ethelbert Dowlen, a graduate of the South Kensington School in London (now the Imperial College of Science), where he had studied botany with the great Thomas Huxley. Dowlen volunteered to devote himself to an examination of the disease in the hope of finding its causes and cure, and Shorb at once engaged him.[84] As a member of the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, Shorb was able to make the appointment official and to provide Dowlen with laboratory equipment and an experimental greenhouse on the San Gabriel property. By the first week of October 1888, Dowlen had issued number one of the weekly reports that he would produce over the next two years. Though he labored with admirable thoroughness, both in the field and in the laboratory, Dowlen was entirely unable to explain the disease or to provide anything like a remedy. Growers could do little except to replant, and then to wait, and though the intensity of the disease in the San Gabriel Valley faded rather quickly, confidence in the future of viticulture was greatly injured. As they had around Anaheim, oranges became the crop of the future.

Shorb and the San Gabriel Wine Company were in dire straits by 1890: he was on the verge of losing his entire investment and had only his wife's estate (itself heavily mortgaged) between him and destitution.[85] The possibility of selling the company now became the main hope of its stockholders, but the chances of doing so diminished as the company's troubles grew. To make matters worse, a group of British investors had bought out the Sunny Slope Winery of Shorb's neighbor L. J. Rose in 1887 and had failed to make the profits they hoped for: the result was that investments in California wine properties went begging in the English money market.[86] Since the San Gabriel Wine Company could not make a profit and could not be sold, it ought to have gone out of business. But Shorb would not submit to that logic yet. A form letter from the company addressed to "Our Patrons and the Trade" on 1 March 1892—just ten years after it had been founded amid such euphoric expectation—announced that there was no possibility of earning "an adequate return on the capital invested" in the wine business. Therefore, it went on, "we . . . beg to inform you that we have determined to discontinue the manufacture and sale of wines and confine our operations henceforth exclusively to the manufacture of brandy."[87] So, Shorb seemed to say, if we can't make it in the wine trade, at least we will stay in business and make brandy. In the next year, we hear of Shorb busily planting citrus orchards on the company's land—an activity that angered the powerful Isaias Hellman, whose bank held the mortgage on Shorb's own estate and who was one of the company's stockholders. "It is all nonsense," Hellman expostulated; "I insist that the San Gabriel Wine Co., must go out of business as other similar corporations have done down South; pay our debts and divide the land and property amongst the shareholders."[88] But Shorb went out of business only on his death, which occurred just a few years later, in 1896, at the rather early age of fifty-four; it is easy to imagine that the scrambling required by his

many enterprises, not least among them the San Gabriel Wine Company, had worn him out.

When the company pulled out of the wine business in order to concentrate upon brandy, its stocks of wine were offered for sale at a heavy discount and were bought up by the New York agency that had represented it from the beginning—evidence, at least, that what the company made was saleable, though at the price of 35 cents a gallon it need not have had much quality to attract a buyer.[89] The kinds and quantities of wines put up for sale at this time make an interesting list: there were nearly 150,000 gallons of wine on hand, 90,000 gallons of which were port and 25,000 gallons sherry; the rest was red and white table wine. Of brandy there were nearly 50,000 gallons, from stocks going back to 1882, the year of the company's founding. The company still owned 1,170 acres of land, and had assets of just over $700,000.[90]

The aftermath of Shorb's brief, busy career is rather sad. The San Gabriel Wine Company struggled on until around the end of the century and then at last expired. Its buildings were taken over for other purposes but have now been demolished. With the proverbial heartlessness of bankers, Isaias Hellman foreclosed the mortgage on Shorb's widow, and the splendors of San Marino, as we have seen, passed into the hands of Henry Huntington. The family migrated to the San Francisco Bay area, where their paths led them far away from the wine business that had so deeply engaged their father and grandfather before them. In the city of Alhambra, which Shorb had both christened and developed, a number of street names commemorate Shorb and his numerous children—Shorb Street itself, and Ramona, Ynez, Marguerita, Campbell, Benito, Edith, and Ethel. Otherwise, his work seems to have left no trace. One looks in vain for anything like a vineyard along the slopes that run for miles up from the San Bernardino freeway to the foothills of the San Gabriel range, and most people living there today are surprised to learn even that grapes once grew in the area; the idea of the valley's once having contained "the world's largest winery" is even more strange.

Shorb's story, as I have said, seems in essentials to be exemplary of the history of winegrowing in southern California: at one end it links up with the era of the missions, through B. D. Wilson and his Mexican wife, whose daughter Shorb had married; at the other, it reaches out to the modern era of large-scale and international commerce; and then it disappears. But good work in one form or another always persists, and it is perhaps not wrong to think that the bold and ambitious example that Shorb set his fellow winemakers helped to change their ideas of what their industry's future might become.

This chapter may conclude on a minor but pleasant note. Somehow, a few bottles of the San Gabriel Wine Company's wines managed to survive to so late a date as 1955, when one California connoisseur, on sampling a San Gabriel cabernet, 1891, found it "a wine to be savoured with pleasure and respect," faded, indeed, but still retaining its character. (One must hint a doubt here as to whether the wine was in fact from San Gabriel: Shorb regularly bought table wine in bulk

from the north to put out under his own label—perhaps it came from Isaac De Turk in Santa Rosa?) As for the 1893 port, that may have been of the San Gabriel Winery's own production (though in 1893 it had already withdrawn from the wine market), and it is gratifying to learn that it was pronounced, upon tasting, "a benediction."[91]Requiescat in pace .