Preferred Citation: . Exploring the Deep Pacific. New york: Norton, [1956] 1956. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt6b69q3vg/

| Exploring the Deep PacificHelen RaittW. W. Norton & Company. Inc.New York |

Preferred Citation: . Exploring the Deep Pacific. New york: Norton, [1956] 1956. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt6b69q3vg/

Copyright © 1956 By W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

First Edition

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 56-10089

Printed in the United States of America

For the Publishers by the Vail-Ballou Press

Contents

| Introduction by Roger R. Revelle | ix | |

| 1. | South Sea Meeting | 3 |

| 2. | My Tongan Family | 17 |

| 3. | Polynesian Christmas | 28 |

| 4. | It's a Man's World | 35 |

| 5. | The Disappearing Island | 45 |

| 6. | Night Exploration | 56 |

| 7. | We Cross the Deep | 63 |

| 8. | The Big Winch | 73 |

| 9. | New Year's Day on the Tonga Trench | 81 |

| 10. | Undersea Everest | 94 |

| 11. | Nofoa Tonga | 110 |

| 12. | Pago Pago | 125 |

| 13. | The Long Shot | 132 |

| 14. | Palmerston—A Family Affair | 147 |

| 15. | Point Mike | 158 |

| 16. | Tahiti | 168 |

| 17. | Storm | 180 |

| 18. | An Atoll Rich in Mystery | 184 |

| 19. | Nukuhiva, Land of Typee | 206 |

| 20. | Coral Reefs and Atolls | 217 |

| 21. | Sight! Surface! | 227 |

| 22. | Helen Seamount | 236 |

| 23. | Alone on This Desert of Ocean | 238 |

| 24. | Extruder Extraordinary | 241 |

| 25. | Operation “Concussion” | 252 |

| 26. | The Beautiful Has Vanished | 266 |

| Bibliography | 270 |

Illustrations

Photographs between pages 128 and 129

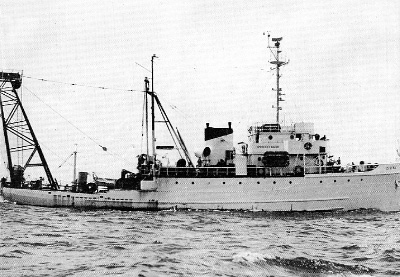

The Spencer F. Baird and the Horizon of Expedition Capricorn

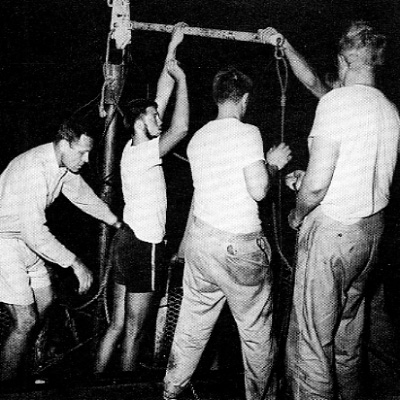

Lowering the corer barrel

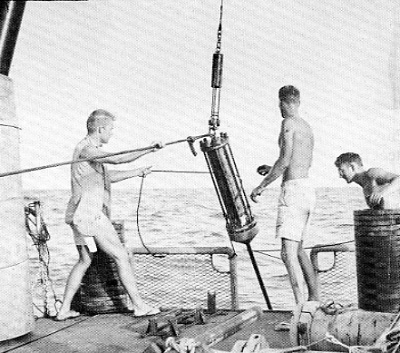

Putting over the temperature probe

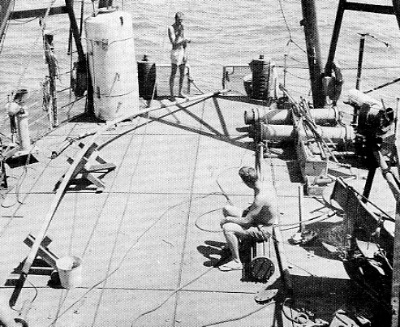

The Baird's fantail

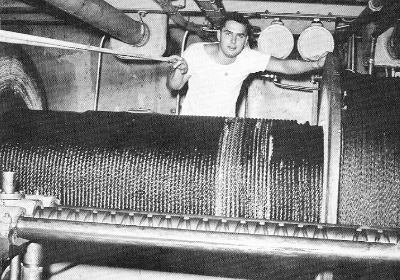

The 40,000-foot cable aboard the Baird

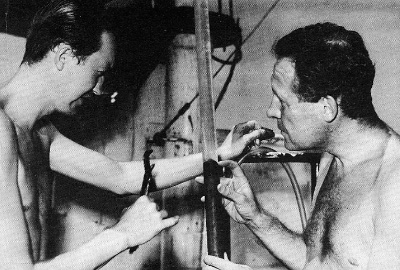

Gustaf Arrhenius and Roger Revelle examine a gravity core

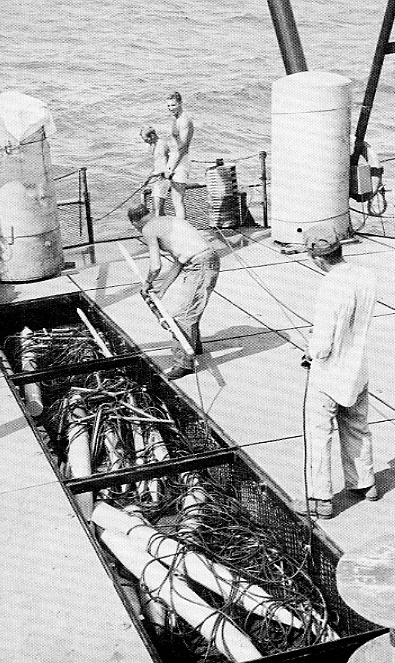

The hydrophones are streamed

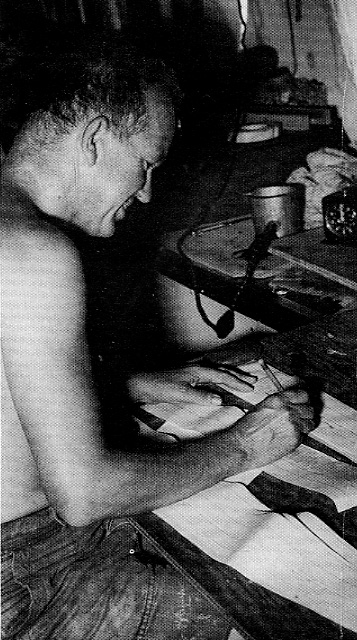

Russell Raitt examines seismic records

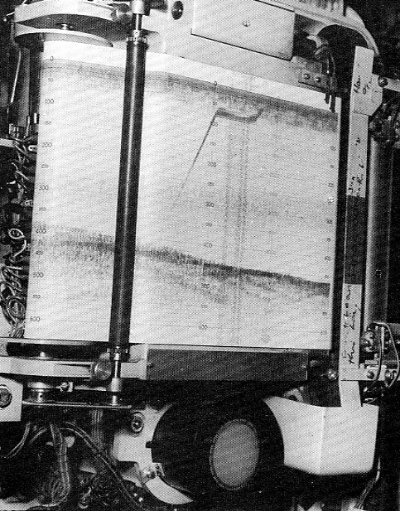

The echo sounder records the ocean bottom

The author typing up the log

Walter Munk examines a coral formation

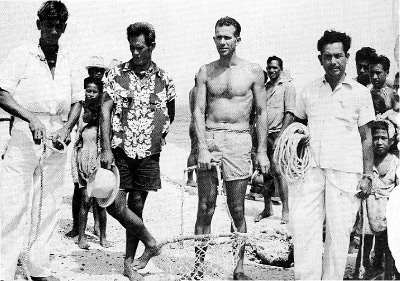

Takaroan pearl divers with Capricorn's Willard Bascom

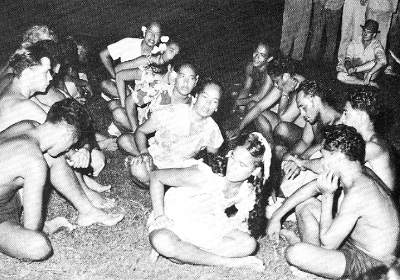

Marquesans perform dance of the loving pigs

Scientists of the Baird

MAPS and DRAWINGS

| Track of Expedition Capricorn | endpapers |

|---|---|

| Profile of Spencer F. Baird, showing main features | Page39 |

| Profile of Kao Island | 58 |

| Tonga Trench is deeper than Everest is high | 64 |

| Map of the Tonga Trench region | 65 |

| Bottom layers in the Tonga Trench area | 87 |

| Guide to the interior of the Earth | 108 |

| How the seismic waves were transmitted | 139 |

| Bathymetric and magnetic contours, Palmerston Atoll | 153 |

| Comparative profiles of volcanic islands, seamount, and coral atoll | 202 |

| Three stages in the formation of an atoll | 204 |

| A typical core record sheet | 245 |

Introduction

ROGER REVELLE

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, La Jolla, California.

Have you ever asked yourself: “Why is there an ocean?” This question probably would not occur to a fish. Immersed all his life in his watery medium, he would think the universe must be made mostly of water, and that such a state of affairs is natural and proper. Nor, unless we give special thought to the matter, is the question likely to be asked by us human beings. The ocean is so incomprehensibly big, so noisily uncommunicative, so alien to our human affairs, that we are likely to take it for granted as simply one of the background facts of life. But to a man from Mars, on Earth for his first visit, our ocean would be a major mystery. His own planet is dust-dry; there is scarcely enough water on its surface to make a little cap of hoar frost around the poles in winter. The Venusians, Saturnians and Jovians would be equally puzzled, for Earth is the only planet with seas and dry land. So far as we know, there is no water at all on Venus. There is plenty on Saturn and Jupiter, but it is frozen in great shells of ice and snow that cover their entire surfaces. Only on Earth are the waters gathered together in a world-girdling

The pattern of sea and land on Earth makes our own lives possible, and it provides diverse environments for the wonderful variety of living things that share our planetary home. The scientists who study Earth, and try to decipher her long history, are convinced that this pattern is no accident. In part it may have originated when our globe was being formed, four or five billion years ago. But to begin with, the oceans were probably small; the mighty flood of waters we see today may have grown almost drop by drop, throughout the lifetime of our planet, from water seeping out of the interior. We oceanographers have never been able to make up our minds as to what actually happened, because in fact we know so very little about the ocean.

If you pick up in your hands a terrestrial globe and hold it so that Tahiti and the surrounding islands are directly in front of your nose, you will see almost an entire hemisphere of blue, with only bits of North America and Australia cutting into the edges. This is the Pacific. The German geographers used to call it “der Grosse oder Stille Ozean”—the Great or Quiet Ocean—in blissful ignorance of its roaring gales and terrible hurricanes. The very existence of the Pacific has been known to white men for only a few hundred years. Less than 200 years ago, say at the time of the Boston tea party, most of the islands that dot its surface had never been seen by a European or an American. Today all the islands are on charts, though often the chart makers are not quite sure about their size or shape or exact location. But the land beneath the waters is still largely unknown. There are many areas of tens of thousands of square miles without a single sounding. One can hardly go out over the deep Pacific in modern oceanographic ships without discovering

This ignorance is not for want of trying. Beginning with the great British Challenger Expedition in 1872–1876 there have been many oceanographic and hydrographic expeditions into the Pacific. But the scale of effort was inevitably small in comparison with the giant size of that ocean. Moreover, until the last few years, the methods for penetrating beneath the sea surface were inadequate to give more than a vague, and in many respects a quite erroneous, picture. The only way to find the bottom depth was to lower a long wire into the water with a weight at the end, and to measure the length of wire paid out when the weight touched the bottom. It was as if surveyors were trying to make a map of the United States by flying in a blimp above a cloud layer and lowering a wire from the blimp once or twice a day!

One day during World War II, I received a telephone call from a young lady in our Navy's Bureau of Ordnance. “What is the bottom of the ocean like?” she asked. “I need to know for a classified development project.” As an oceanographer masquerading temporarily as a Naval officer, I was shocked. How could anyone ask such a simple question about such a complicated subject? I told her that if she would come over to my office I would give her a lecture of several hours' duration. But she said she was in a hurry and hung up the phone after I told her that in some places the deep sea floor is rough, hilly, and rocky, while elsewhere it is flat and muddy. Over the succeeding years I have occasionally thought about this young lady. I have slowly come to realize that in fact she extracted from me in that one sentence all I knew at the time about the floor of the deep sea. It is only because of the oceanographic research that began

The development of electronic art has made possible new methods of oceanic exploration. For example, with the aid of a marvelous gadget called the recording echo sounder, we are able to send a short, sharp sound straight down toward the sea bottom (somewhat like clapping our hands through a megaphone) and to measure the time required for the echo to return from the bottom to the ship. Such depth measurements can be made quickly and continuously, and recorded automatically on a chart, so that we can make a profile or cross section of the shape of the sea floor along the ship's track. By putting the cross sections from many cruises together we shall eventually have a map of the land under the sea almost as accurate and detailed as our present-day maps of Mexico and South America.

The Scripps Institution's Capricorn Expedition, which Mrs. Raitt has described in this book, was one of a series of exploring expeditions into the deep Pacific sent out by many countries since 1946. Other expeditions, some of them much longer and more ambitious in scope, have been carried out by the Swedes, the Danes, the British, and the Russians. All these cruises had essentially the same purpose: they were voyages of discovery in which new instruments for oceanographic exploration were pitted against the vast unknown of the Pacific Ocean. Our expedition differed from the others chiefly in the variety of instruments used and in the greater diversity of interests of the scientists on board.

Some of the members of the expedition were interested in the electric currents in the atmosphere; others wanted to

Like any other historical research, the problem of deciphering the history of the ocean is a detective problem. The historian of human affairs can often use the confessions made by historical personages. The geological historian has no such advantage. There are no written records. His evidence must be entirely circumstantial, a patient piecing-together of many kinds of clues into a convincing case. What are the clues that may tell us something about the history of the ocean? One of the most dramatic are the coral islands or atolls, which lie like carelessly tossed necklaces on the velvet sea throughout the western tropical Pacific. Each atoll, though it reaches only a few feet above sea level, represents the summit of a mountain peak higher than Mount Shasta, rising steeply from the deep sea floor. In the atolls that have been examined carefully during the last few years, there has been found an ancient volcano at the core, 70 to 100 million years old. The top of the old volcano is now thousands of feet below the sea surface, although at one time it was an island rising above the sea. Above the volcanic rock is a great bone pile, the skeletons and shells of plants and tiny animals that lived in water less than 100 feet deep. We can deduce that for nearly 100 million years the sea level has been rising continually, relative to the old volcanoes, but we can not tell as yet whether the volcanoes sank back into the crust of the earth like corks

The great trenches or deep submarine gashes that surround the central Pacific floor give other clues. A major objective of the Capricorn Expedition was to study one of the most majestic of these, the Tonga Trench, 15 to 30 miles wide and over a thousand miles long, striking nearly due north and south between Samoa and New Zealand, and extending downward beneath the sea nearly a mile further than Mount Everest rises above it. This black and rocky chasm, as steep-sided as the Grand Canyon and seven times deeper, must have been formed by giant stresses deep within the earth's interior. That these stresses are still violently active is evidenced by the volcanic explosions and earthquakes that every few years rack the Tonga Islands.

Other clues come from measurements of the heat flowing continuously out of the earth through the bottom sediments into the ocean, and from the sediments themselves. These are deposited so slowly, and each sediment layer reflects so accurately the conditions in the overlying waters at the time of deposition, that they constitute the best available record of events on the earth during the great ice ages of the last million years.

A most significant clue comes from the character of the rocks far beneath the ocean floor. One of the remarkable scientific discoveries of the postwar years has been the finding that the rocks which underlie the continents down to depths of 20 miles form only a thin veneer, about four miles thick, beneath the oceans. Below twenty miles under the continents and four miles under the oceans there is a sharp change to a rock of unknown character. Some scientists think that this subcrustal material is like the rock of the

The very shape of the sea floor gives evidence for our history. In the eastern north Pacific there are long narrow zones of parallel high ridges and deep troughs, somewhat like the great north-south ridges and valleys of East Africa. These are zones of fracture, where the earth has crumpled under great stresses. Around the volcanic islands of the Pacific, for example Tahiti and the Marquesas, the sea bottom is a flat, nearly level plain, sloping gently outward from the islands for several hundred miles. These plains may yield evidence of great volcanic outpourings that have shaped large parts of the sea floor.

But I am not writing a book about the history of the ocean. This is supposed to be an introduction to a book about the historians themselves and how they go about their job. Mrs. Raitt has attempted, gallantly and honestly, to describe the life of an oceanographic ship. To a considerable extent she has succeeded in reproducing the noise and uncertainty, the small triumphs and tragedies, the mistakes in judgment and execution, the lucky chances and hard-won successes of scientific work at sea.

Of course, our expedition was in a wonderfully romantic part of the world, the islands of Melville and Gauguin, of Loti and Maugham. To all of us there was something bitter-sweet about the contrast between the hard and rather grim work at sea and the lotus lives of the islands. This also is one of the ingredients of this book.

Oceanographers are essentially just sailors who use big words. One of my land-loving scientific colleagues is fond of

Acknowledgments

An expedition to study the ocean is a joint effort of many: the men on ships who have gone to sea before us; the oceanographic institution that sends out the ships; the crews, the technicians and the scientists aboard. On Expedition Capricorn the Navy Department was also a partner in the enterprise.

In like manner this book was the work of so many people that it is difficult to know whom not to thank. First of all I should thank my companions of Expedition Capricorn for accepting me aboard the ship and assisting me in the preparation of this manuscript. My apologies in advance to them for any mistakes I have made in reporting their work.

I am also greatly indebted to two people, Roger and Ellen Revelle, who helped make it possible for me to go. Nor could I have gone on the journey or finished the book without the love, cooperation and patience of my family, all of them.

Sam Hinton, curator of the T. Wayland Vaughn aquarium-museum of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, has provided this manuscript with illustrations and maps, and John MacFall, expedition photographer, has furnished many photographs. I am indebted to them and to the Scripps Institution for use of this material.

For careful and generous reading and criticism of the

Glenn Gosling and members of the University of California Press have been most helpful with their advice as has Betty Shor in the preparation of the manuscript. I am fortunate to have such understanding editors as Katherine Barnard and Robert Farlow.

But I could not have finished the book as it is today without the able assistance of oceanographer John Knauss.

Thank you, everyone,

“Ofa atu,”

Helen Raitt

1. South Sea Meeting

I suppose I shouldn't have come. All the cautious people said No. This is a foolish venture.

I can hear their voices: “We told you it couldn't be done. Meeting an oceanographic husband for Christmas! Stupid woman, give your husband a break. You shouldn't go to the South Seas anyway. That's a world of brown women. Have you read Michener?”

“Yes, I know, I know.”

But …

Other oceanographic wives have met their husbands in Mexico, Panama, Italy, England. Why shouldn't I meet Russell in the South Seas?

The expedition on which my husband had embarked, with other University of California scientists, was the largest yet undertaken by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Our men had previously made trips (in cooperation with the Navy Electronics Laboratory at San Diego) up in the Arctic, on a long shuttle down South America way, and out as far west as Bikini. Now it was Expedition Capricorn. This would involve two ships, the Horizon and the Spencer F. Baird—the ship Russ was on as Senior Geophysicist. They were to travel together exploring the ocean depths through

Both ships had been at Eniwetok during the atomic tests. They had made an oceanographic survey of the area and Russ had made some seismic measurements to learn about the structure of the coral atoll. Scripps had also, I knew, designed and built a large amount of special equipment for making observations during the actual tests.

When I knew for certain that my husband would be in Suva, Fiji Islands, on December 3 and in Samoa for Christmas, I secretly resolved to be in those two ports with him. For years the job of raising four children had more or less prohibited such excursions. But this fall seemed to be an auspicious occasion to spend Christmas away with Russell. My eldest daughter was married. One son had graduated from college and entered the Navy. Another son was in love, at college, and working. He said, “I can only be home one day.” And Martha, aged thirteen, had said, “I want to go to Grandmother's for Christmas.” So my trip wasn't impossible from the point of view of family considerations. And, in a way, it seemed it was now or never. A geophysicist studying the earth beneath the Pacific sails to many parts of the ocean, not at times that fit his (or my) wishes, but as opportunities arise. My enterprise began to take shape. When Russell left early in October, I said “I'll see you at Christmas!”

My only chance to meet the expedition was to fly to Suva and then come home by freighter. I secured my passports and visas, took all sorts of shots in the arm, and on Thanks-giving Day I was at the San Diego airport with my friends and family who had come to see me off. I was heavily laden with clothes for roughing it on coral reefs with Russ, clothes

Now I was in Fiji, 6,000 miles from home, waiting for the Horizon and the Spencer F. Baird to show up. Was it only a month before that I had left La Jolla, California, on a cold winter's day? Now it was summer, although December, and I had not brought a sweater, nor would I need one.

Suva, I soon discovered, was a town with sights, sounds, and smells that appeal to all the senses—especially the pungent smell of copra. This was a world where fuzzy-haired, lovable, courteous, husky Fijians lived side by side with sad-faced Indians. Here was the typical white man in the tropics, dressed in white shorts, white shirt, and high white wool socks, sipping his tea or gin fizz served by a tiny Indian boy. On the street, the strongest specimens of men I'd ever seen, the Fijians, passed by.

But no ships, no husband, no news! Imagine my chagrin when I called on our ship's agent in Suva and got more questions than answers.

“We heard that your two ships were coming to port November 25. Then we heard December 3. Now it's December 7. Where are they?”

“I wish I knew,” I said wistfully.

“What are they doing?”

“Studying the ocean,” I replied.

“They wrote months ago that they would need fuel and supplies here,” the ship's agent from the Burns Philp company told me. “We'd like to know their needs.”

“I'm sure I'll receive a cable by the first of the week,” I had answered, with conviction I did not really feel.

I couldn't tell these Fijians what I suspected to be the situation. This Scripps-University of California expedition had not originated in the same way as other globe-encircling trips of this century, such as the ones made by the English, or the Swedes or Danes. On those expeditions, plans had been made several years in advance; notices, articles had been sent ahead, and finally the Challenger, the Albatross, and the Galathea had arrived in ports amidst great fanfare.

All I could state was that our ships would leave Kwajalein atoll in the Marshall Islands about the middle of November. A plan had been publicly announced. But no mention was made of how the ships got there. I couldn't state that our oceanographers had been gone a long time and were engaged in secret work of top priority to our country and that perhaps they had been delayed. I couldn't describe the activity all last winter when the men had worked feverishly for months, day and night, in their labs at Scripps, getting their equipment ready for some project that was hidden with the strictest secrecy.

Nor could I reveal how they had quietly disappeared last fall, two or three at a time, with no fanfare, bound for the Pacific, destination unknown, no address.

The men in Fiji said our ships were two weeks late, but they had been lost to me for months. I had no idea in what condition the ships would arrive, what they had seen, or what their needs would be at this port.

I knew only that they left behind at Scripps this fall many homes with lonely women, the men vanished for months. Finally, the newspapers told us that a thermonuclear bomb had been exploded at Eniwetok. Our anxious

Of course, I knew that when the tests were over, our ships were to take a Scripps expedition for the first time into new areas of the South Pacific. The little 143-foot white ocean-going tug, the Horizon, had been on our earlier expeditions, and it quietly left first for its unannounced destination this fall.

One day, Len Usher, Public Relations Officer for the Fiji government, had news for me.

“We have traced your ships to Ocean Island, but have no idea where they are now,” Mr. Usher said. “You know, we expected them two weeks ago.”

Again I made an attempt at an explanation. “Yes, our ships have been delayed, have had real difficulties with equipment,” I invented. “Our long cable was late in arriving at the dock in San Diego.” And I told the story of our fabulous winch, which has a cable that can stretch 40,000 feet down into the ocean, the longest cable on any American ship and especially designed for Expedition Capricorn.

“You know, the Galathea was here,” Mr. Usher said with his eyes glowing. This was a statement I had heard more than once. I had been in La Jolla when the round-the-world Danish oceanographic vessel, the Galathea, arrived. I had been a guest aboard the slim white vessel and well remembered the cordial reception we were given. They had set an all-time high in international oceanographic entertaining. Could our ships meet their challenge?

I visualized our two little work-weary tugs pulling into

Yet Roger Revelle, director of the expedition, had said before leaving La Jolla that we must give a party aboard and that if I arrived in Suva first, I should see what could be done.

I had begun to like Fiji. It had that beautiful combination of enough civilization for the fastidious, but many inaccessible, out-of-the-way places for the curious. Although Suva was hot this time of the year, there was often a cool breeze, and who would go to the tropics, anyway, if he were not willing to accept heat? The temperature rarely went above 90° or below 60°. The hot season was from October to March and the cool from April to September. It was hot and rainy now. Hurricanes were also the subject of conversation this time of year. Suva had recently been hit by a hurricane which ended the life of one of the hotels and blew off the roofs of many houses.

I liked the Grand Pacific Hotel, known as the GPH, where I was eventually able to find accommodations. This hotel appealed to me, perhaps, because I'm the romantic, impractical type anyway. It was a large, squarish two-story building with a huge hall in the center and the dining room at one end. Winding carpeted stairs led up to a balcony that ran around the center hall. When a guest wished to find the bathroom or the phone booth, he looked down on all those below and was visible at the same time to everyone present in the lobby.

The bedrooms had tall green-shuttered doors leading onto a huge veranda that encircled the outside on both floors. A quick tour around the outside balcony early in the

I liked to have my tea out on this balcony in the cool early morning. Here I could look out at the green lawns, the palm trees, and the blue bay beyond. Some morning I would see Russ's ship coming straight toward me in this direction. How long would I have to wait?

And then I finally received the long-awaited cable:

HELEN RAITT GRANPACIFIC SUVA

BAIRD HORIZON ARRIVE SUVA ELEVENTH X REVELLE

KIBR

Here at last had been definite news for all the curious in Suva and for me, who was beginning to wonder if I should ever have tried to meet the ship in the first place. I had not known the ship's call letters, nor had anyone else in Suva. In reply I sent the ship a message and received this answer:

HELEN RAITT GRANPACIFIC SUVA

HOPE DEPART FOURTEENTH X GLAD GIVE COCKTAIL PARTY ON BOARD X YOU ARRANGE DATES AND INVITATIONS X ARRIVING EARLY MORNING TWELFTH PAGO PAGO CHRISTMAS X

ROGER

Christmas in Pago Pago! My excitement and relief at the cable's arrival were offset by the bad news this second wire brought me. Would I be stranded in Fiji and have to spend Christmas alone in Suva?

Russell had been right when he said that meeting oceanographic ships would be a difficult feat. Our ships' delay had been fatal to my well-laid plans. Now, although I knew the Horizon and Baird would arrive and refuel and we'd

For I probably couldn't get to Samoa. I had thoroughly canvassed the possibilities of traveling from Suva to Pago Pago, Samoa. I had been told there was an inter-island New Zealand steamer called the Tofua.

After receiving the wire I went aboard the Tofua and made inquiries. From Suva each month it made a ten-day trip to Nukualofa, Vava'u, Niue, Pago Pago, Apia, and then back to Suva. All for $70. But this December the Tofua was not going toward the islands until after Christmas—which meant I could not be with Russ on Christmas!

I canvassed all the shipping offices and finally resorted to buying the Fiji Times and Herald, which gave me news each day of ships in ports. One day I noticed a little squib about the Tielbank, a copra steamer of the Bank line, which was bound for Tonga and Samoa.

I went immediately to the company representing the Tielbank, only to be told, “This freighter isn't a passenger ship. The accommodations would not be suitable for you, Mrs. Raitt.” I wondered, whatever could be so wrong with this ship?

“But I'm willing to accept any accommodations in order to be with my husband on Christmas,” I had answered.

He had been firm. “I'm sure you can find a better way. Have you tried Teal Airways?”

It was useless to explain that I had tried every way out of Suva that had been suggested, even the New Zealand Air Force.

“Will you give me the name of the Captain of the Tielbank? I would like to invite him to our ship's party.”

One day I went to Mr. Usher's office behind the large room where the legislative council convened, there to address

I wrote on the envelopes: Ratu Sir Lala Sakuna and Lady Maraia, Ratu George Tuisawaii O.B.E. and wife, Ratu G. K. Cakobau and wife. Chief Ratu Cakobau was a direct descendant of Fiji's famous Cannibal King of earlier days. In addition to these Fijian chiefs, chosen for their positions of trust in the colonial government, I wrote other names: Vishnu Deo, J. Madhaven and wife—leaders of the Indian population. I was inviting all members of the legislative council, which, together with an executive council, governs this British Crown Colony.

The problems of this colony revolve about its racial division. In 1946 the Indian population surpassed the Fijian. Of the total population of about 300,000 people, 47 per cent are Indian and 44 per cent Fijian. The rest are Chinese, Rotuma Islanders, Europeans, and islanders from all the other parts of the Pacific.

Luckily for me, I had received help with my problems. I had met young Granger Johnson on the plane coming from Nandi, and he had introduced me to his family. His father proved to be the head of one of the large trading companies of Fiji, and one of the able men on whom Suva depended. Although of New Zealand parentage, Mr. Johnson said proudly, “I'm a Fijian. I was born here.” He was a short, thick-set man, briskly energetic, with a tanned, ruddy face. Everyone in Suva called him Tui, which means “chief.” He was of the greatest help to our expedition and its problems.

Then two days before the ships arrived, Winter Davis Horton, Jr. (nephew of the actor Edward Everett Horton), showed up in Suva. Winn was acting as purser for the expedition. With him came the Swedish geologist, Gustaf

Finally Friday, December 12, arrived. I was unable to sleep. I was up several times during the night, dashing to the veranda to look out on the ocean where I hoped to see the Baird's lights. At five-thirty A.M. I started down to the dock to see if our ships had come to port. I found, not the Spencer F. Baird, but Tui, his two sons and Rhodes Fair-bridge, a geologist from Perth, Australia, who was joining our ships at Suva.

Some of us went back to have breakfast at the hotel. It was after breakfast when I heard a shout from Winn. “Helen! There she is!”

I rushed out to the back veranda. I had looked longingly in this direction for so many days. Could I believe my eyes? The Spencer F. Baird was slowly steaming into the harbor. Grabbing my blue plastic raincoat and wishing I had a black Fijian umbrella instead, I started out with Winn on the ten-block walk to the dock.

What a reception in the pouring rain! The ships came closer and closer. Not even the Fijian stevedores were on the dock for atmosphere, it was so wet. Only our small group eagerly awaited their arrival. The Horizon was following close behind the Baird. Winn let out a loud call resembling the bark of a seal and was answered.

Now I could see Russ, hale and hearty, standing on the deck. He was brown, slightly thinner, but with that happy twinkle in his eye, obviously glad to see me. This was worth all the waiting.

I saw other friends: tall, blond John Isaacs, near the bow,

The ships tied up to the dock, but no one was allowed aboard yet. I called out to Bob Dill, “Here's a letter for you from your beautiful wife.” (Gloria had asked me to deliver it as she saw me off at the airport.) Bob for once didn't clown, but grabbed the letter. Then I handed Walter Munk the slide rule he had forgotten and I had been commissioned to bring him. He had been a friend of ours for many years and fired questions at me in rapid succession.

Standing beside Walter was Bob Livingston, our doctor, a professor at the School of Medicine of the University of California at Los Angles, who had joined the ship at Kwajalein. He was a vital member of the expedition, in charge of the aqualung divers and of the health of all. Soon he was conferring with the Port Doctor.

Fijian government officials finally pronounced the ship clean. They didn't like Spencer, the ship's hound. “You have diseases in your country we want to keep out of Fiji,” they said, referring to rabies. After Spencer was locked up, we on the dock were allowed to go aboard.

I knew again, by the way Russ greeted me, that he was glad I had come. We had much to talk about as he packed to go ashore with me to our living quarters at the GPH.

There was not sufficient dock space that day for the two ships, so the Horizon moved alongside the Baird. This meant that the entire party would have to take place on the Baird. How 250 guests would ever get aboard the ship I did not know.

Our men somehow managed to find clean clothes, and

On our one little ship there came such an assortment of people! Large Fijian chiefs with their bushy hair, dressed correctly in white suits; small Indian officials, their wives wearing colorful saris; the Catholic bishop, the Protestant ministers; ship captains; New Zealand Air Force officers; government officials; businessmen of the town; doctors—everyone.

Our guests, after being welcomed to our ship by Roger Revelle and Walter Munk, climbed down a narrow, steep ladder to the fantail where I greeted them and suggested food and drink. We also proposed tours of the ship, guided by our oceanographers. The lab was a very hot place in which to try to explain our equipment, yet the guests were eager listeners as our perspiring oceanographers answered their many questions.

Late in the afternoon, when the party was at its peak, the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific, His Excellency, Mr. R. C. S. Stanley, and his daughter arrived, followed by the Governor and his wife, Sir Ronald and Lady Garvey. Suva was receiving us most warmly indeed! I was hopeful that the party was a success even though crowded, and I still marvel that nobody fell into the sea.

The shipboard party was only the beginning of a whirl of luncheons, dinners, and parties that never stopped—a luncheon at Harold Gatty's, the feast and night at Deuba, the party at the Hedstroms' home. I can't remember when I slept. Finally on Sunday night, after a supper served on Tui Johnson's porch, we went into a huddle over the future plans of the expedition.

It was taking longer than anticipated to repair the broken

“What better place to be at Christmas time than Tonga?” said Tui. “Why don't I cable Prince Tungi for permission?”

Tui, it seems, was the Tongan government representative in Fiji. He and Roger disappeared from the party for a time and then came back with the following cable. Tui was certainly a man of action.

WIRELESS: HRH TUNGI NUKUALOFA

SCRIPPS INSTITUTION OF OCEANOGRAPHY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SHIPS BAIRD AND HORIZON AT PRESENT IN FIJI IN CHARGE OF DIRECTOR ROGER REVELLE CONDUCTING GEOPHYSICAL AND OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INTEND MAKING SCIENTIFIC SURVEY OF TONGA DEEP WITHIN NEXT TWO OR THREE WEEKS. DIRECTOR PROFESSOR REVELLE IN VIEW OF LONG TIME EXPEDITION WILL BE AWAY FROM UNITED STATES DESIRES DO UTMOST MAINTAIN MORALE OF SCIENTISTS AND CREWS BY SPENDING THREE DAYS OVER CHRISTMAS UNDER MOST CONGENIAL CONDITIONS AVAILABLE. I HAVE TAKEN LIBERTY OF INFORMING HIM THAT I WOULD COMMUNICATE WITH YOUR HIGHNESS SEEKING PERMISSION VESSELS TO REMAIN NUKUALOFA DURING THAT TIME. EXPEDITION IS FULLY AUTHENTICATED AND REVELLE BELIEVES HIS MEN ARE WELL BEHAVED AND TRUSTWORTHY. MRS. RAITT WIFE OF A SENIOR SCIENTIFIC MEMBER REQUESTS PERMISSION LAND VAVAU EX TIELBANK THEN PROCEED NUKUALOFA BY LOCAL VESSEL IF AVAILABLE OR EXPEDITION SHIP THERE AWAIT HUSBAND THEN DEPART TOFUA 29TH DECEMBER KINDLY TELEGRAPH IF PERMISSION

― 16 ―GRANTED. CAN ADD MY PERSONAL ASSURANCES FROM CONTACT REVELLE AND SENIOR MEMBERS AND MRS. RAITT. KINDLY REPLY AS SHIPS LEAVING FIJI SIXTEENTH. REGARDS.TUI

The next day we heard that our request had been granted by Prince Tungi, and I found that luckily the Tielbank would take me, so I purchased a ticket for Vava'u for $17. I packed one suitcase for Russ to take on the Baird and the other for Vava'u. The Baird's cable was still not repaired, and I found that my ship would be leaving at daybreak. I would leave Russ and the Spencer F. Baird still in port.

But it was hard to part from Russ when there were so many uncertainties about when we would meet again. I stood on the deck of the Tielbank among an Indian crew and waved goodby to him as we pulled quietly away from the dock at 5:30 in the morning.

As we went out into the harbor, I also waved to the Baird, now anchored well out from shore. I wondered when I would see her again. I was off on the second leg of my Expedition South Pacific.

2. My Tongan Family

Friday, December 26

The freighterTielbank was a tramp which, after picking up cargo all over the South Seas, was on her way home to Glasgow after a year away. Although she had been partly loaded with copra meal and copra oil, we still rode high in the water. Captain Aitkin expected to take on more copra at Vava'u.

The whole ship was permeated with its smell. At first, in Suva, I thought the smell of copra unpleasant; it even seemed to me slightly unclean. By now it had become a friendly odor associated with this world I'd begun to love.

I was told by Captain Aitkin that a rhinoceros-beetle infestation had come to Vava'u in Tonga. This was a pest greatly dreaded by coconut growers, and rigid means have been devised to fight it.

Beetle-free ports will not receive ships that might bring them the beetle in a copra cargo. For instance, the Tielbank could not go to Nukualofa in Tonga or to Suva after loading copra at Vava'u. But she could go from Vava'u on to Samoa, where they have the beetle, and then deliver the copra from both these islands to England.

“If it weren't for the beetle, we wouldn't be going to

On the Tielbank there were Indians to fetch me to come and eat the heavy English meals we were served, and Indians who said their prayers facing Mecca each sunset and dawn. My fellow passengers were the Stephens family, who promptly adopted me. “Mum,” Sela Stephens, was a Tongan matriarch of seventy-five, returning to her own land after forty-five years away in the New Hebrides.

Forty-five years ago she had left Tonga with her English husband and had traveled over a thousand miles of water in a small 28-foot ketch. Now she owned a New Hebrides island where she lived, surrounded by the forty-four members of her family, counting sons-in-law, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren. Her English husband had recently died, and her half-Tongan son Oliver and his New South Wales wife were taking her back to see her family in Tonga.

They gave me lessons in the Tongan language. I typed out vocabularies for each day and learned to say malo a lelei (Good day) and many other words. In the evenings I got out my ukulele to play for Mum, and we persuaded Oliver to sing. These were the first Tongan songs I'd heard.

The early morning when Mum and I stood on the Tielbank's deck together and saw our first glimpse of the little islands of Vava'u was memorable. The ship wound its way up a channel through clusters of small palm-covered islands. We proceeded slowly up the tortuous course, and I began to see small villages on the water's edge. Surely this was one of the most beautiful harbors in the world.

Around the final bend, so small a distance that some could swim it, we saw Neiafu, the chief village of Vava'u. People were walking toward the dock. Mail and news from

A Tongan medical practitioner who had boarded our ship pointed to a large frame house near the shore, saying that it was run by a woman named Ana Falekava and that she had taken guests before. Perhaps I could stay there. The ship tied up to the dock and preparations began for loading copra.

I stepped down the long, treacherous gangplank and went up the street toward the village green. It was very hot for midmorning. Many barefooted Tongans were already busy at the stores. Both men and women wore a ta' ovala, or the “fine mat,” tied around their waists with a kafa cord. Some of the women wore a long vala (a sarong-type wraparound) under their dresses. The men wore shorter valas.

I had walked about two blocks when I came to Falekava's, a faded frame house with a long veranda across the second story. I entered the hall and stepped into a room, bare except for a table in the center. Here I met Lisiate. He was a tall, lean, barefooted Tongan wearing a white shirt and a black vala about his waist.

He had an unusual face, one that caught my attention immediately. The lines etched in this countenance showed a life of thoughtfulness for others. He must have been in his forties.

He spoke to me quietly in English. “Won't you sit down?” He found me a chair. “Tell me your problem.”

I explained to him about the expedition, my husband, meeting the ship in Tonga, and that I needed somewhere to stay until I could get to Nukualofa.

“We didn't know you were coming. We would have been ready. We will take care of you,” he said gravely. He took

“This is fine,” I said. “Now I should perhaps go back to the ship and get my bags?”

“I will meet you there with a lorry,” Lisiate said. Getting my possessions through the customs was a long, hot and complicated business. Fortunately Lisiate worked in the customs office, and he was most helpful.

He loaded my belongings in the truck along with those of the Stephenses. I said goodby to Captain Aitkin and others and we were all off to Falekava's. I had left my ship. I belonged to the village now. A little fearfully I tried out my Tongan vocabulary.

“Malo a lelei,” I said when I reached my Tongan home, and met Lisiate's wife, Kaufoou. I put out my hand and she took it in a friendly manner and smiled at my greeting.

“Malo a lelei,” she said.

I soon became the fine eiki amelika (American married woman) of this village. That is what they called me in their conversation. In less than an hour after we arrived, the town, I am sure, had any particulars about me they needed. There was no necessity for newspapers or radios in this village.

Lisiate had brought his family to live with Ana Falekava, his aunt—a portly, quiet-speaking woman—when her husband had died. Now eleven or more lived there with her. To wake up in the morning and find that Kaufoou and her young sons had been sleeping on a mat on the porch floor beside me was a new experience.

In Vava'u it was very hot, as Vava'u was closer to the equator than Suva, and there was no breeze from the sea

Members of the Falekava household would come to my room, squat on the floor, and happily watch me at whatever I was doing.

Each day I could hear Kaufoou's soft voice call to me as I went by: “Where you going?”

They were my family, and I felt that I belonged to them.

Among the 10,000 Tongans on these eighteen or more islands was one American woman from San Francisco, Pat Matheson. She had come out here, married a Scotch doctor, Farquhar Matheson, who was connected with the tiny hospital. This couple had a three-month-old baby, the only white child in Vava'u. Pat became my friend, and through her I met a Tongan woman, Tu'ifua, for whom they had named their daughter.

I enjoyed the hours each day I spent with Tu'ifua, a young unmarried educated Tongan woman about thirty years old, who spoke English and had high rank in the village. Her father was related to Prince Tungi's wife, Princess Mata'aho. Tu'ifua was not a plump Tongan woman, but stood straight and thin, about my height, 5 feet 6 inches, and had dark brown hair and lovely, sensitive eyes which showed great compassion and understanding.

When Tongans walk together hand in hand they do it in a slightly different manner than we do. They intertwine the two little fingers rather than the whole hand. It was thus that I walked down the street with Tu'ifua when she took me to a cowboy movie at the Funga Lelea theater, and to

Women in Tonga are responsible for cooking the meals, washing the clothes, making mats and baskets, and preparing feasts. Also, women are truly respected in this kingdom ruled by a woman, Prince Tungi's mother, Queen Salote.

When Tu'ifua told me that no woman has to go to work for money in Tonga, I asked her “Why do you suppose Vivi helps Kaufoou at Falekava's? She comes every day, and, as you know, sometimes helps serve our meals.”

“Kaufoou probably asked her to come and help her,” said Tu'ifua.

Here everyone works together. Kaufoou was never alone in her kitchen. Perhaps this was one of the secrets of Tongan life, part of the happiness of their women. No woman is shut up alone in her house as in our world. There are no lonely widows, unhappy spinsters. Everyone is part of a family group. They belong to the family, whatever its size, share in the events and work of that family and that village. They have a feeling of kinship, of belonging, that we have lost. All children are loved. There are no orphanages or insane asylums in Tonga.

Had I known definitely when I would next see Russ, I think I would have enjoyed my days in Vava'u even more, for it was a most beautiful spot. But it was strange to be waiting there for some ship to come take me away. I could not communicate directly with the Baird, and had no real knowledge of what had happened to her.

On my fifth day there the Tongan government ship Hifofua was at the dock and I, with many other Tongans, purchased my $5.00 ticket to go to Nukualofa for the holidays.

My fond farewells were colored with many promises to return on the interisland steamer, the Tofua, after the holidays. In the customs shed my typewriter, ukulele, camera, books, suitcases, and all possessions were given a sticker which said:

“This is to certify that this package has been inspected by — and is entirely free of eggs, larva, and adult stages of rhinoceros beetle.” I was now officially beetle-free.

When our ship pulled away from the dock, I smiled to myself and thought of all the American friends who had said, “You won't mind what kind of a ship you travel on.” I didn't. But they should have seen me on this ship, a native interisland schooner 90 feet long. On the deck with us were several pigs that became seasick and added their vomit to the conglomeration of other smells. We had chickens, babies, and perhaps sixty or more deck passengers, who swarmed all over the little schooner. Soon the stern was completely covered by mats and each inch of space appropriated. Here these experienced travelers prepared to eat, cook, sleep, and live for twenty-four hours. I joined the pigs, the crew, and Betty, the village nurse, out on the bow. My ukulele was immediately appropriated by the crew with my permission, and we began to sing. From that moment on, the crew, from the Captain down to the cook, took me on as their personal responsibility.

I have never had such attention on any ship, nor a chance to hear native Tongan songs for so many hours on end. Obviously, American women do not often travel on this Tongan government boat, as there are only a handful of Americans in the whole kingdom of Tonga. I met three.

Apparently a singing papalangi (white person) from faraway America was a novelty. As we became friends, I showed them all my pictures of Fiji, told them of my love for

At supper time I was called to come below and eat with the cabin passengers, my friends the Stephenses, a meal of hardtack, canned beef, rice, and canned fruit. I found that the man to whose cabin I had been assigned was a Tongan Mormon missionary who had joined the ship above Vava'u.

Not feeling up to sharing the tiny cabin with a man and not knowing what is done in Tonga, I thought the simplest solution would be to stay up all night. I did not realize that this presented a problem to the polite Tongan crew.

“We take care of our women first,” said Captain George to me. And I looked at Betty and her friends already stretched out on the deck below, apparently fighting off seasickness. But they were set for the night. They had brought mats and were prepared. Even had I wanted to stretch out on the deck, there was no space by now.

“I'd like to stay up and watch the sea and stars,” I said. “I don't travel at sea very often.”

“You are welcome to come up on the bridge,” he said. “But I will give you my bunk below.” I thanked him and assured him that he was not to worry about me. I stayed awhile below and saw all the crew go in and out of his tiny hole-in-the-wall cabin where apparently ship's supplies were also kept. I thought I'd try the bridge.

Here I had a cool ride on this strange moonlit night, and music, and long chats with the few who spoke English. I learned again the Tongans' lack of fear of sharks.

“If you are not afraid of them, they won't bite you,” said Harold, one of the crew.

Up here also were forms stretched out on every foot of

On the bridge, perched next to the Tongan boy at the wheel, was a native girl whose metallic voice added to the music of those of the crew as we sang late into the night and early morning.

Finally at three in the morning we came in sight of Kao, a volcanic island in the shape of a perfect cone. Nature seldom produces such symmetrical forms as this on so grand a scale. No one was left awake on the bridge but the man at the wheel and myself. Deciding I'd risk the cockroaches below, I went to the cabin and slept soundly for two hours on Captain George's bunk. Since he had made himself as comfortable as possible on the bridge deck, I thought I'd better use his bunk. I never saw a cockroach.

The kindness of all on the boat—to me, a woman from a foreign land—made me reflect again on this unique little kingdom of Tonga and marvel at these curious, intelligent, friendly people. Among all Polynesians they are said to be the strongest and fiercest. They are certainly wonderful physical specimens. But why had I not heard more of Tonga?

The hidden, unknown, nearly landlocked harbor of Vava'u had not been described, at least to my knowledge, in tourist literature, geologic literature or even in the National Geographic, yet it must be one of the ten most beautiful harbors in all the world—of this I was sure.

From the Tongans I learned about the antiquity of their country. They have preserved the names of their rulers for over 1,000 years. They told me the legend of their origin, how the great Maui from the underworld went to Samoa to obtain a fishhook from an old man there, Toga Fusifonua, and then, using the hook, pulled up Tongatabu and the low islands of Ha'apai, Vava'u and the Niuas. The high islands of Kao and Tofua were made of chips thrown from the sky by the stonemason god, Tagaloa Tufuga.

“Where did you Tongans come from?”

“Samoa,” was the answer. The language, customs, and stories are more like the Samoan than any other Polynesian culture. Tonga means “south.”

The Tongan government, alone of all the Polynesian peoples, has maintained for over a hundred years an enlightened policy of “Tonga for Tongans.” Here in Polynesia is a monarchy which is financially solvent, has no public debt, is ruled by a Queen, a Prime Minister, and an elected parliament of cabinet ministers and commoners. The British Consul acts as adviser to the Queen in matters of financial administration and foreign affairs.

After breakfast we were back on the bridge singing. The guitar and my ukulele changed hands, and always the next man in any group seemed able to play. Finally the second mate, the ship's best singer, joined us. He proudly sang what American songs he knew. Most Polynesians seemed to know “You are my sunshine, my only sunshine.”

Quite to my surprise he said “I'll sing ‘I'm dreaming of a White Christmas!’” It was nearly Christmas, so many miles away from home for me. I said this would make me homesick and cause me to cry, and it did.

The Tongans took great delight in singing me into Nukualofa Harbor in the late afternoon so that I would

3. Polynesian Christmas

The next day, Christmas Eve, I stood on the dock, waiting for our ships to come in. I had received a wire saying that the Baird was to arrive first, the Horizon later. I had a fancy purple-and-green sisi (Tongan version of a hula skirt) around my waist, just handed me as a gift from the friendly Tongan cook of the Hifofua.

A grim-looking Tongan official in khaki ordered me off the dock, but seeing tears in my eyes, relented and allowed me to hide in the shed. There I stood waving my red sarong in greeting. The Baird was flying a beautiful newly made red Tongan flag as she sailed into port and our little tug looked imposing. I was proud.

As the ship came closer to the dock the Hifofua cook asked: “Which is your mari (husband)?”

Fortunately for me, Russ was standing in a position of prominence on the bridge. This was pure chance. My friends from the Hifofua would never know a senior geophysicist of an expedition if they saw one, and they were always convinced that my husband must be Captain. We never managed to make it clear to all that he was not.

The ship was no sooner docked than the Horizon was alongside, and we were all soon lost in the excitement of a tropical Christmas Eve in this kingdom. What a Christmas! The whole island was alive. Lorries full of singers, musicians,

I can still hear the high, metallic voices of the women singers combined with the deep harmonies of the men … haunting music. It must be that plaintive combination of primitive music overlaid with missionary hymn singing.

Also on this Christmas Eve we had an audience with Prince Tungi in his palace. Roger, Russ, and I walked across the green lawn to the Palasi (palace), a large white building two stories high, red-roofed, with towers and architectural gingerbread trimming. A Tongan government official of high rank, a nobleman, ushered us into a grand Victorian parlor where, in a large chair of state, sat Tungi, Prince and Premier. Over six feet tall, he is a huge, well-proportioned man with dark brown hair and a dignified smile. He says he weighs 323 pounds.

This was a prince who could trace his descent from ancient chiefs. His forebears ruled the Tongans before the Norman conquest of England.

Tungi's mother, Salote, born in 1900, was the beloved and wise six-foot-three queen who had come to the throne when she was eighteen years old. She married a Tongan noble, Ulime Tungi, who became the queen's consort and premier. He died in 1941. Queen Salote was away in New Zealand this Christmas, purchasing clothes to wear to the coronation in England.

Crown Prince Tungi, the elder of the two sons of this couple, was in his early thirties. The heir apparent had gone to college in Sydney and had taken an honors degree in jurisprudence at Sydney University. He became premier in 1945. He was married to the daughter of a noble family, Mata'aho, and had two small children.

Prince Tungi was dressed for our audience in crisp white cotton with his coat buttoned up to the chin. Around his waist he wore a wide, clean matting, ta'ovala, worn by Tongans. After chatting about our mutual friends and his visit to Washington, we told him how happy we were to be allowed to come to Tonga this Christmas.

Our audience was suddenly interrupted when the national anthem of Tonga was played outside on the lawn. Prince Tungi said,

“All the bands of Tonga are serenading the palace this Christmas Eve.” We rose and stood solemnly as the serenading band played the song to its end. I thought of Tungi repeating this act time after time through the evening. There are some disadvantages to being a prince.

While we were served tea in cups of delicate china on a glistening silver tray, Prince Tungi asked about the work of our ships in Tonga. Roger told him about surveying the deep Tongan Trench which lay parallel to the length of his island kingdom on the east.

“We are planning to cross this Tonga Trench about 25 times before we leave this area, and to take other geophysical measurements that have not yet been made.”

“How deep did you find the Trench?” Tungi asked.

“South of here we have found it to be about 35,000 feet deep,” Roger answered. “Your trench is one of the deepest spots in the world.”

Christmas day itself began with a church service, then a shipboard turkey dinner, and an afternoon of sightseeing and fun. The Tongans had loaned us two lorries which we piled into and drove about the island, even stopping for a swim on a coral beach this Christmas day.

The day after Christmas was Boxing Day. Prince Tungi and Princess Mata'aho had invited us to a great feast. What

We were taken out towards the sea to a little village where a canopy of mats had been erected on a white, sandy hill not far from the pounding surf, by the British Consul and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. J. E. Windrum. Here Prince Tungi and Princess Mata'aho and the entire village had prepared to entertain us.

Being the only woman of the expedition, I was given a pillow to sit upon next to Prince Tungi and across from Princess Mata'aho. When more of our group arrived, we made two long, straight lines facing each other, the men sitting cross-legged, Tongan fashion, on the mats on the ground. I was given an unusual floral neckpiece and a sisi for my waist, and every man was presented with a garland. Suddenly, off to our right, we saw natives bringing in huge litters of food. The first litter was placed in front of Tungi and Mata'aho and then another and another was brought in until all our mats were covered with a massive array of food.

In each seven-foot stretcher were golden-brown roasted pigs (with heads attached). Interspersed were large pink crabs, stalks of yellow bananas, large slices of red watermelon,

We had been given tapa cloth napkins which had a cutout border design around the edge. Behind every guest stood or knelt a Tongan maiden to wait upon him and hand him any delicacy he desired from the lavish feast set before him.

Tungi for a time did not partake of any food but chatted with us. Later Mata'aho pulled some crisp pieces of brown skin from the pig in front of us and handed these to her husband.

I soon saw that we would never make even a dent on the tremendous quantity of food. The native villagers appeared in the background, and when we had finished they carried off the huge trays of food for the whole village to gorge upon. At the close of our meal a small kava bowl, filled with water in which floated tiny flowers, was served each guest for a finger bowl.

Natives beautifully dressed in flowers and sisis, their bodies shining with oil, began to dance for us to the music that a group of Tongans had been playing and singing throughout the feast. They danced in the sun on the white sand against a setting of pandanus trees, blue sky and ocean. Their rhythms were both like and unlike traditional hulas—more lusty, if anything.

Later, ladies of the village, regardless of age or figure, spontaneously joined in the dance. Everyone dances in Tonga. Dancing and singing are as much part of their life as are eating and sleeping.

Who would ever wish to leave such a kingdom? Not I. This feast, the many presents that had been given me, the

But on this last day had come complicated decisions. My plans for future travel were again upset. I had expected to leave Tonga on the interisland steamer, the Tofua, to go on to Samoa where I could again meet the Baird.

But one of our men, John Isaacs, needed to return to California. Prior commitments had made his departure necessary. He, too, wanted passage on the Tofua. But only six Europeans could leave on the Tofua after Christmas, and many more were trying to go. If John and I both sought passage on the Tofua, it would place the Tongans in a difficult position, as I knew the Tofua was crowded with applications for passage. I had not quite bargained on being stranded a month in Tonga. But obviously it was more important to get John home than to get me to Samoa.

Roger said to me, “Since John has to return, why don't you come aboard the Baird and go with us to Samoa? If the Tofua takes only six Europeans from this port, I doubt if you and John can both leave Tonga on the same trip.” Roger was right. I must either take the proffered ride on the Baird or be stranded in Tonga.

I was strongly tempted. I had always wondered how men work at sea. What were their habits? Cooped up for days in close quarters, did the men's dispositions suffer? What were the difficulties of work at sea that Russ had mentioned? Here was my chance to find out.

But if I went on the Baird, would I get in their way? And I had said that I did not believe women should travel on oceanographic ships.

The expedition had originally planned to take a woman

There was no clear-cut, easy decision to make. At Fiji it had been possible to say “I'm going on by myself.” But here other people were involved …

What of the men who said bluntly, “Women don't belong on oceanographic ships?” And Russell—would I put him in a difficult position by being aboard?

I thought of my difficulties in explaining to the crew of the Hifofua why I didn't ride on our ship.

“Why don't you travel with your mari on your ship? Why don't your men take care of you?” the Tongan crew had repeatedly asked me.

“No women on ships” was a concept out of their world. Interisland schooners all through the South Seas had women aboard. On a big rich American ship like ours, of course there was room for me!

“What a strange American custom!” Did these strange American customs lose their importance out here so many thousands of miles from home?

Roger wanted to know my answer. “Will you join us?”

“I'll go,” I said.

4. It's a Man's World

Saturday, December 27

Was it only this morning that I stood on the deck and watched the men cast off the lines as we prepared to leave Nukualofa, this land of love? I was sad. I hated to leave this lovely, clean little town that reminded me of a huge park. The cool green carpet of the unending lawn was set off by many flowering trees and shrubs, pink South Sea oleanders, red and yellow kaute (hibiscus), scarlet-blossomed flamboyants.

I looked at the Hifofua, the little 90-foot schooner in the harbor, and waved goodby to the ship where the crew had sung to me for nearly twenty-four hours on end. Some of my friends from the Hifofua were clustered on the dock waving to me, as our ship slowly began to pull away.

“Nofoa, Lino. Nofoa, Harold,” I called out. I couldn't hear their answering “Alua” but I know that is what they said. “Alua” is the goodby spoken by the one left behind. It means “I stay.” Nofoa means “I go.”

Left behind by his ship was scientist John Isaacs below us on the dock, waving to us. I am sure he had mixed emotions, as did I, for he was leaving the ship, his home for the past three months, and I was leaving a land I had grown to love.

But a bunk is a bunk where you find it out here, I had come to realize.

Now I find myself traveling in luxury, on this “best oceanographic ship afloat.” To me, she's an oily, greasy, rough-riding tug, the 760-ton, 143-foot Spencer F. Baird. I see already from my first day aboard how she rolls and pitches. But here we have cold drinks really cold and hot coffee hot, not tea. My first adventure was to have one of the Baird's fabulous breakfasts: fruit, cereal, waffles, bacon or ham and eggs, right in the heart of Polynesia. I hadn't had menus like this for a long time. Russ and I stood in the galley and waited for the waffles to bake.

Kenny, the cook, with his cheerful smile, white cap and apron, stood there kidding me. “So you think you'll try traveling with us for a change?”

“Yes. This chow looks good to me.”

“If those scientists give you trouble, you come to the galley,” he said. And I could see Kenny was going to be my friend. He is a good-natured cook, something quite unusual in ship's cooks, I'm told.

With a steaming hot waffle on each of our plates, we went to the ward room where Frank, the tall, silent messman, served us the rest of our breakfast: papaya, cereal, coffee.

Luckily for me, the ward room was not crowded this time of day and I didn't have to take the stare from fifteen pairs of eyes as they surveyed their new female passenger. Roger Revelle was already in the ward room.

“We'll indoctrinate you right now, Helen,” he said. “You put your plate down, like this,” he said, suiting the action to the words, “and then go under the table.”

I watched this huge, lanky man slide under the long table secured to the deck and pull himself up through the narrow

Down I went under the table, miraculously missing the deck, and up on the other side. Russ followed. So far, all was well.

After breakfast I realized that I was no longer in Tonga where I must conform to the standards of Queen Salote, who prefers skirts on women at all times. Skirts are an impediment, treacherous and out of place on this ship. Quickly and happily, I pulled out my yellow shorts and shirt, discarding shoes in favor of sandals.

In the first free minutes aboard I tried to stow away my gear in our cabin on the boat deck. I didn't want feminine problems to interfere with the business of the ship. I packed away shore-going clothes and put shirts, shorts, and jeans in the handy drawers below my bunk. With Russ I wrapped the large Tongan tapas and pandanus mats I'd been given and tied them to the overhead. It was difficult to get our tiny cabin in shipshape condition. There were ship's boxes of medical supplies, extra suitcases piled on the deck, giant fluted tridacna clam shells in the corner, brightly colored sisis and leis hanging from the pipes on the overhead. I soon discovered that the real problem was to stow my belongings so that when the ship rolled, everything would not crash to the deck.

Russ led me up the ladder to the bridge directly over our cabin to talk to Captain Larry Davis. This dark-haired, conscientious, quiet man made me feel at home at once.

“Did you go aboard the Hifofua?” he kidded Russ, “and see what your wife's been traveling on?”

“It was probably a good introduction to the Baird, ” Russ answered. Then Larry proudly showed me his orderly chart room, the instruments, how the boat was steered.

“Do you get seasick?” he asked with a sympathetic twinkle in his eyes.

“I hope not,” I answered.

“She rides like a cork,” said Davy (Cleveland H. Davis), second mate, who had been all over the world in ships.

The Baird is a converted U.S. Army sea-going tug, which came from the mothball fleet at Olympia, Washington. She is Navy-owned, but operated by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. This four-month trip in the South Pacific was her first major oceanographic voyage for Scripps. Larry showed me the log book where the sea and weather are described each day, and I learned about the routine checks that are kept on compasses, gyro, and barometer.

“The Baird's navigational equipment is far superior to that of other ships of this size,” Larry said. “She has a gyro pilot, compass, radar, loran, and sonic depth finders.”

“What about her engines?” I was sure this was a question I was supposed to ask.

“She has a twin diesel-electric propulsion engine totaling 2,000 horsepower.”

I was told that on the bridge they stand three watches with two men always on duty. Navigation is particularly important aboard these oceanographic vessels. First mate and navigator Bob Haines tried to explain it to me.

“It isn't enough to finally get a good star sight after four days of bad weather and to know where you are now. These scientists need to know where they've been for the last four days.”

“I get it. They need the exact latitude and longitude of every station for their records?”

Profile of the Scripps Oceanographic vessel Spencer F. Baird, showing her main features. Horizon had a similar hull but differed somewhat in her superstructure.

“Yes. So we have to work backwards, correcting our dead-reckoning positions where we think we've been in the past four days, on the basis of this new star fix.”

And since there are no loran (longrange electronic navigation) stations in this part of the Pacific, the navigators must rely on star and sun sights for the ship's position at all times.

Leaving the bridge, Russ and I climbed down the steep ladders to the lab, two decks below.

The lab area extends from the midship section to within approximately 40 feet of the stern. It is about 16 by 27 feet in size. There are sinks, work benches, a chart table, and a desk, a circular Nansen-bottle rack and enough instruments to keep me asking questions from here to Samoa. Every inch of available space seems to house some delicate piece of equipment. I see less than two feet of passageway through the complicated maze that these geophysicists have managed to make of their lab. Each man annexed a cubbyhole where he has some drawers and a bench on which to work.

Here in this congested room the men were working, propped on stools or boxes if handy, also standing, either tinkering with their equipment, making measurements, or working on records.

At the chart table three men were huddled over a map of the ocean bottom. Weighty decisions as to the ship's course were apparently under discussion.

When he saw me, Roger stopped his work and handed me the log book that John Isaacs had been keeping and turned it over to me.

“Read this,” he said. “We'll begin work on it tonight after dinner,” and he told me that later I would be taught to stand the four-hour scientific lab watches which were around the clock, day and night.

“Let me learn one thing at a time,” I begged. “No lab watches yet. I'm not very mechanical.”

“Everyone stands watches on this ship except Kenny, Frank, and the mess boy,” he said.

The lab room was very hot, as the ventilation was poor, even though there were a few portholes open on either side and the door was open onto the stern. The men wore shorts, their bodies were covered with sweat. To get a breath of cooler air, I went out on the deck to the stern of the ship, which is called the fantail.

There on the stern was the large “A” frame which rises 32 feet above the deck and is designed to handle loads of equipment up to thirty tons.

Right behind the main deck laboratory were the large drums of the winch. Over a sheave of the “A” frame it was paying out a length of the eight-mile-long tapered steel cable carried below decks on a storage reel.

“When this spool is uncoiling the steel cable, you must stay off this part of the ship,” Russell cautioned me. I listened meekly.

And I began to worry. I knew I would have difficulty explaining how I ever happened to be connected with this two-ship expedition of seventy men. This trip of mine violates all American oceanographic traditions. Famous European oceanographers have taken their wives on parts of their globe-encircling travels. Professional women oceanographers have gone to sea. But I wonder if any other woman in America has ever joined a prolonged deep-sea geophysical exploration of the Pacific?

I hope they will believe me at home when I say it is a man's world, not for women, this cruising about studying the earth beneath the sea. It's not simple or safe. On this first day a

I want to learn everyone's name on this ship—the seventeen scientists and seventeen crew members. Luckily for me I've known most of the scientists for a long time: Roger since college days, our friend Walter Munk, my La Jolla neighbor Willard Bascom, and the young men—Dick Von Herzen and Alan Jones, who work with Russ, have been visitors many times at our home.

Gustaf Arrhenius and Henri Rotschi, newly arrived from Europe, I had known ashore, as well as physical oceanographers Art Maxwell and Ted Folsom.

New to me were Dick Blumberg, University of California engineer, and many of the men on the Horizon. Horizon had fifteen scientists and twenty crew members, and was much the same size as our Baird, but had no big winch like ours. The men aboard the Horizon had different measurements to make, and from their conversation I learned that weather balloons were released around the clock, hauls of plankton and fish were made by nets, and the sea bottom was dredged for samples.

Russell had been right when he had said, “You have no idea what our work or life at sea is like.”

There are no books or movies about geophysical deep-sea explorations for wives such as I. But now I'm learning. I've stumbled on to that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of seeing Russ's work at sea.

Some scientists are fortunate and marry women with scientific backgrounds. Not Russell. My college degree was in English literature and my newspaper training included such topics as society, early California rancho history, and writing

Now I'll be taking a sea-going course in beginning oceanography. But I'll not receive a grade or a diploma when I get home. I do have one certificate now, which I received at Scripps Institution—for counting grunion. In studying these mysterious fish the biologists once tagged a certain number of them as they made their regular spring migrations to the shore, laying their eggs on the beach in the spring at high tide. I helped the marine biologists count the tagged grunion in the midnight hours and so became initiated as a life member of the “Society for the Investigation of Non-Gastronomical Characteristics of the Grunion,” with permission to spawn on the beach at high tide.

But the work on this ship does not seem to involve such simple tasks as grunion counting. We have geologists, chemists, geophysicists, engineers, and divers doing highly complex work aboard.

I look about our ship and see weird, intricate oceanographic equipment. Huge instruments suspended on a long cable disappear into the sea below for hours on end. Bottles in yellow cases with thermometers attached go overside, like a kite in reverse, only the bottles are fastened along the kite string at regular distances and this long wire penetrates far down into the water below. When these Nansen bottles have reached the correct depth a little “messenger” is sent down the wire and trips the bottles. They fill with water and come back laden with valuable samples of H2O at various depths.

Near the stern of our ship three men are examining a torpedo-like instrument which Russell says is usually towed when the ship is underway. Today our sister ship, the Horizon, 50 miles away, is dropping TNT charges. These make

This is a fascinating new world, and though there is much I do not understand, still, I'm learning. These men are exploring the depths below the surface. They're describing the shape of the ocean floor and what lies beneath it.

“We are gathering information so that we can write a history of the ocean,” explains Roger Revelle, Director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography and expedition leader.

I thought of the illustration I had seen of an area of the ocean bottom near Hawaii, the underwater Mid-Pacific Mountains. One looks at the picture and imagines that the ocean has been rolled away.

Every day, every hour with our instruments we are examining the sea beneath us … what is below?

And I am learning that there are many unanswered questions about our oceans. Have the oceans always been as they are now? Have the oceans grown through geologic time? Is part of the ocean getting deeper or shallower? Are the subcontinents sinking or rising towards the surface?

5. The Disappearing Island

Sunday, December 28

I'm still catching my breath on this dizzy, busy ship. Although it's only my second day aboard, I'm wondering if I ever dare go to sleep—I might miss something. When I arrived in the lab to struggle with the ship's log, I saw all sorts of activity. The men on watch had their eyes glued to the echo sounder, the magnetometer was “streamed” behind the ship, and BT's (bathythermographs) were being taken every couple of hours. BT's are vertical temperature profiles of the upper few hundred feet of ocean. Some of these things I know a little—very little—about.

“We crossed a seamount last night,” Walter Munk said.

“I wish I'd seen it.”

“There'll be more, don't worry, Helen.”

I must find out how a ship learns about underwater mountains it can't see. Today perhaps we're going to a mountain we can almost see, and just a few years ago could have seen. We are cruising along one of the greatest chains of active and dormant volcanoes in the world. This is a line of weakness in the earth's crust, where we can expect an island to appear. Last night in the ward room we had a discussion about Falcon Island, a submerged volcano near here, 50 miles

Its Tongan name, Fonua Fo'ou, means “new land.” In 1928 our friend Harry Ladd had visited the island, which was then 2 miles long and 600 feet high. The island erupted in 1933 and in 1936. It was only 30 feet high, but still 1 ½ miles long in 1938. Not often do islands go up and down in the sea with such speed.

“How did Falcon look when Harry Ladd and Tungi's father were there?” I asked Roger.

“It was a black, desolate, treeless waste with two craters. There were trench-like gullies and steep cliffs, 100 feet high. They had a difficult time landing and had to swim through the surf. Tungi's father swam ashore carrying a barometer and other small gear tied on his head in a cloth.”

“I remember,” I said. “Tungi told us more about it … the sulphurous gases that made their eyes smart, and the hot climb to the summit to plant the Tongan flag.”

They had walked over to the crater and had seen a boiling lake whose surface was hidden by clouds of steam. Harry Ladd has written about the sputtering and whistling steam vents that came out of the orange, yellow, and gray walls surrounding the lake. The water tasted vile, he said, and the ground was very hot.

“Was there anything alive on the island?” I asked.

“Only a bush, but all sorts of things had washed ashore: a whiskey bottle, a coral head, coconuts, I think. This is one way life begins on a new island.”

“But what happened to this island if it is completely submerged now? Did it sink?”

“Perhaps as the lava column cooled,” Roger answered, “it contracted, and this may have caused the island to sink. A geologist would call it a withdrawal of subterranean lava.

“All the more reason to stop and let us dive over it,” said Bob Livingston, with that diver's gleam of anticipation in his eye. “When have any divers ever explored a submarine volcano? This is worth doing!”