34—

Dum Spiro Spero

Charles's destination was his own palace of Hampton Court where Colonel Edward Whalley, a cousin of Cromwell's, was in charge. Captivity sat lightly upon the King and he had many visitors, including not only Cromwell but Cromwell's wife, his daughter, and her recently-married husband, Henry Ireton. His children also visited him and they all sat to John Hoskins, the miniaturist. Charles's chaplain, Jeremy Taylor, also came. He had been with the King during much of the fighting and had been one of those honoured in 1643, at Charles's request, by the University of Oxford, who conferred upon him the degree of Doctor of Divinity for his pamphlet, Episcopacy Asserted . Now he had published his Liberty of Prophesying , which interested Charles although he did not altogether agree with it, but there were probably other reasons for his visit. He lived ten miles from Mandinam in Carmarthenshire, the home of Joanna Bridges who was rumoured to be Charles's natural daughter. At all events Charles gave Taylor a ring with two diamonds and a ruby, a watch, and a few pearls and rubies which ornamented the ebony case in which he kept his bible. There was no reason why he should give these to Taylor unless they were to pass on to Joanna Bridges, whom the divine later married as his second wife. Charles hunted in his familiar parks, played bowls, walked the terraces and gravel ways of the gardens, watched the Thames, the familiar river associated with his happiest days. In the great house itself, of some 1500 rooms, he had virtual freedom, for he had given his word not to try to escape. He was, nevertheless, so carefully watched that he had little communication with Henrietta-Maria. Yet, despite this deprivation, he remained buoyant and was confident of the future. But he was slow in coming to an agreement with anybody. Berkeley urged him to make a decision. Was he letting slip another opportunity? It seemed likely, for Cromwell's position

was once more endangered in the autumn of 1647 by Lilburne and the agitators who were increasingly restless at his failure to produce the expected results. Cromwell clapped Lilburne in the Tower.

Charles was well aware of Lilburne's plot to capture the army. Sir Lewis Dyve, his own supporter, had been imprisoned in the Tower since the capture of Sherborne Castle in August 1645 and was in close touch with the voluble and excitable Leveller leader, who disclosed his plans to Dyve who passed them on to the King. But Lilburne was at the same time suggesting collaboration with Charles, whose reign he still maintained was 'but as a flea biting' to the enormities of Parliament. The King was also being approached by other sectaries, notably by William Kiffin, the Baptist, who reported to Lilburne that Charles had given him such assurances of liberty for the future that he was completely satisfied of the King's goodwill. On the strength of this Lilburne tried to arrange through Dyve a meeting between some of the leading agitators and the King. If the King would satisfy these men, Lilburne would pawn his life, so Dyve reported to Charles on October 5, 'that within a moneth or six weekes at the farthest the wholl army should be absolutely at your Majestie's devotion to dispose thereof as you pleased'. But Charles was of the opinion, with some justification, that Lilburne at this stage did not represent the true feelings of the Levellers and he heard enough of Cromwell's strength in the Army Council meetings of October and early November to discount the dreams of Dyve and Lilburne. Moreover, he found the reports of the army debates at Putney, which lasted from October 28 to November 11, particularly disturbing, for Levellers and agitators were there discussing a document called The Agreement of the People which claimed a Parliamentary vote for all men on the grounds that the 'poorest hee' in England had as much right as the greatest. Charles was left further away than ever from the possibility of any approach to such men. The violence of their language may, indeed, have contributed to the decision he was about to make.

He had received several round-about reports of plots on his life and the dismissal of Ashburnham, Berkeley and other attendants on November 1 increased his sense of isolation. He had been growing increasingly melancholy at his enforced captivity. Lady Fanshaw, who had made one of the war marriages at Oxford, saw him about this time and was much distressed at his sadness: 'when I took my leave', she wrote, 'I could not refrain from weeping: when he had saluted me, I prayed to God to preserve His Majesty with long life and happy

years; he stroked me on the cheek, and said, "Child, if God pleaseth, it shall be so, but both you and I must submit to God's will, and you know in what hands I am".' A mysterious letter warning him directly of a plot by the agitators to kill him arrived on the 9th. But his plans were already laid. On the evening of November 11 he left his greyhound bitch whimpering in his room and walked out of Hampton Court. He was joined near the Palace by Colonel William Legge and himself led the familiar way to Thames Ditton where Ashburnham was waiting with Berkeley and horses from his own stables. The little party made for Bishop's Sutton in Hampshire, but the weather was foul and even with Charles as guide they lost their way in Windsor forest. It was dawn before they arrived at the inn where fresh horses were waiting and they were warned by an accomplice that a Parliamentary Committee meeting was already in progress there. So, changing mounts but without rest or refreshment, they pushed on. As when he left Oxford, Charles was undecided where to go. If a boat had been ready he might have gone to Jersey or to France. Perhaps he allowed himself to be influenced by Ashburnham, who was inclined to favour the Isle of Wight. It was still within his kingdom, it was reasonably remote from any assassination attempt, there were a number of good Royalists there, and it offered escape to the Continent if necessary. Moreover Charles seemed to think, without any very good reason, that the new Governor of the Island, Colonel Robert Hammond, would be in sympathy with him.

No contact had been made with Hammond but the Earl of Southampton, who had visited Charles at Hampton Court shortly before he left, welcomed the King at his old haunt of Tichfield on Southampton Water and here he waited with Legge while Ashburnham and Berkeley went over to the Island to feel their way with the Govenor. Their passage was delayed by bad weather and they handled the affair ineptly. They did not know Hammond nor he them, and Ashburnham was staggered by Berkeley's open and, as he termed it, 'verie unskilfull entrance into their business' when, immediately after the opening of formalities, he asked Hammond if he knew who was near him. Naturally enough Hammond replied in the negative and Berkeley rushed on: 'Even good King Charles, who is come from Hampton Court for feare of being murdered privately.' It is difficult to know who was more confused in the subsequent exchanges. Hammond recovered first and suggested that they all three of them go to the King.

Charles had found the waiting long and had put out feelers for a boat to France, but the ports had already been closed on news of his escape. When at last his friends returned Ashburnham went in to him and told him that Hammond was outside. 'Oh Jack! thou hast undone me!' cried Charles. His place of retreat was revealed, what he had intended to be exploratory had become obligatory and there was no going back. They crossed to Cowes the same day and went on to Carisbrooke Castle in the centre of the Island. The people greeted him with affection as he passed and a woman thrust a damask rose into his hand, plucked from her garden at that late date. The Army Command had found the note that Charles had left at Hampton Court saying he feared for his life, as well as the warning letter signed E.R., and the search parties were out; it was not long before Hammond was in communication with them and Charles's whereabouts were known.

Some of Charles's friends believed that the army were glad he had gone, on the grounds that he had proved no use to them and was encouraging the rift between the Command and the agitators. Whether Cromwell and his friends had planted the idea of murder in Charles's mind, whether he himself had manufactured the idea as an excuse to be gone, or whether the notes and his fears were genuine, some of his supporters nevertheless believed he had made a mistake both in leaving Hampton Court and in going to the Isle of Wight. But at first Charles had no reason to regret the change. People were friendly and supporters flocked to Carisbrook to see or speak with him. There was also some justification in his own belief that in dealing with the Army alone he was negotiating on too narrow a front, for, before the year was out, both Parliament and Scots had sent Commissioners to him on the Island. He deliberately played for time, came to the conclusion that the Scots were offering better terms, and made a secret agreement with them in which he promised Presbyterianism for three years and they agreed to raise another army for him. Their solemn agreement was buried in lead in the Castle grounds, at the end of December. Charles tried to postpone his reply to Parliament, but the Commissioners insisted he make known his response to their overtures before they left the Island, and he was forced to admit that he had rebuffed them.

Although he had not expected to declare himself so soon, he had been well aware of the hostility that would result and had again been thinking of escape. But where? To the Scots? To Jersey or France while the Scots raised their army? On the day the Parliamentary

17

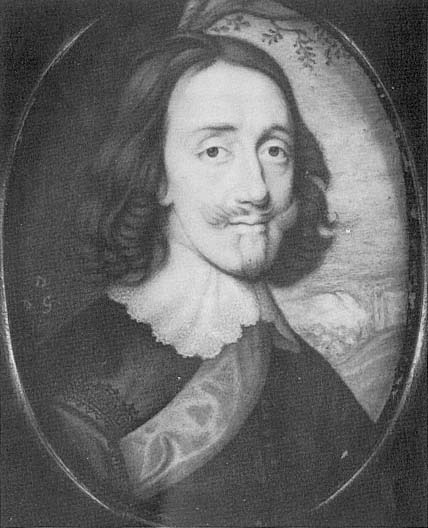

Charles during the civil wars, after the original miniature of John Hoskins. Probably

painted during his imprisonment at Hampton Court There is a marked difference

from the serene monarch of the previous portrait.

18

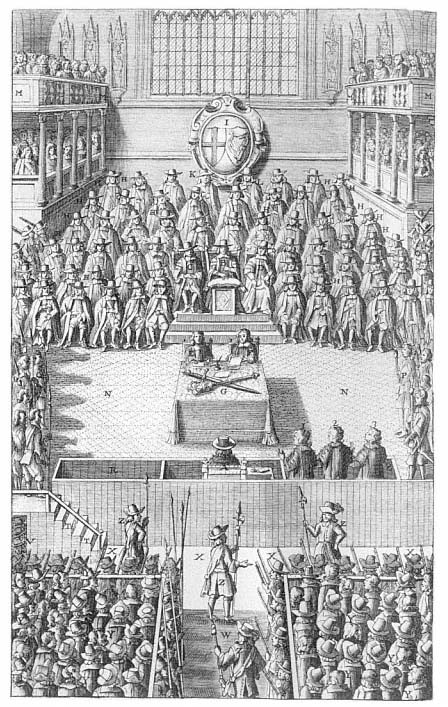

The King on Trial in Westminster Hall, from a contemporary engraving. Charles sits

in the dock, facing his accusers.

19

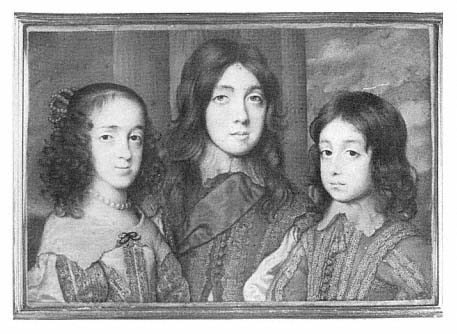

The three children whom Charles saw in his captivity at Hampton Court, where this

miniature was painted by Hoskins. James, Duke of York, shortly afterwards escaped

but Elizabeth and Henry visited him on the day before his execution.

20

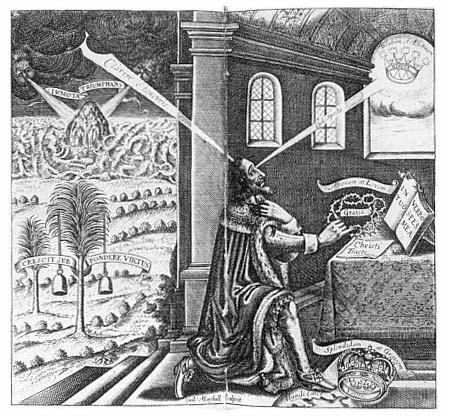

The execution of Charles I as seen by a French contemporary. None of the extant

drawings is accurate, but this one gives a realistic general impression of the scene.

21

Charles the Martyr as portrayed, in slightly varying form, in thousands of copies of

the Eikon Basilike published immediately after his death and reprinted dozens of times.

Commissioners left he learned that the ship he had been expecting was at Southampton and that a small boat was in readiness to take him across from the Island. The wind was set fair. Hurriedly he prepared for the journey. Hammond was attending the departing Parliamentary Commissioners and there was no one to stop him. But a glance out of the window at the last moment revealed that the wind had changed and was blowing from the North, making it impossible to leave the Island.

His captivity had hitherto sat lightly on him. Many of his household had joined him, his carriage and a quantity of his books had been sent over, he had driven round the Island, seen the Needles, walked about Newport and other towns and villages. But on the strength of the King's refusal to Parliament's terms and the knowledge of his agreement with the Scots, tighter security at Carisbrooke was imposed, his Household was reduced, and Ashburnham, Berkeley and Legge were sent away. A sympathetic officer in Newport attempted to rescue him but his plan was discovered before it could be tried, and on 15 January 1648 Parliament passed a vote of No More Addresses to the King.

Escape was now more than ever on his mind and the number of people willing to help him indicated both the extent of royalism in the Isle of Wight and his own ability to command support. There were soldiers like Colonel William Hopkins and his son George, who lived at Newport; Captain Cooke, one of his guards, who had come over to his side; Captain Silus Titus, who had originally served Parliament but had been won over by Charles at Holdenby, had come south with him and remained near him at Carisbrooke; there was the sailor who unsuccessfully tried to get letters to the King from his wife and children. Among civilians were Abraham Dowcett, Edward Worsley, Boroughs, Cresset, Napier, who all had access to Carisbrooke; and more than one who, like John Newland of the Corporation of Newport, owned a boat which could be put at the King's disposal. In Charles's household at Carisbrooke were Henry Firebrace, now twenty-eight years old, his page of happier days; David Murray, his tailor; Uriah Babbington, his barber; and a Gentleman Usher named Osborn, who was appointed as a spy but defected. Osborn's duties entailed waiting upon Charles at table and taking care of the royal gloves during the meal; it was easy to convey and receive messages in the fingers of the gloves. There were also Mrs Wheeler, who was in charge of his laundry, and her assistant, Mary, as well as the old man

who brought up coals. Working between London and the Island was his old friend, Jane Whorwood, and Mrs Pitt, a contact of Titus at Southampton. The Earl of Alford, who had spoken so strongly for Parliament in the 1620s was ready to help at his home near Arundel, and Sir John Bowring, who had become a clerk to the Privy Council at Oxford and who had useful connections in the Isle of Wight, had for some time been a trusted confidant and go-between. There were in addition many who helped in carrying letters; Major Bosvile, who had turned up at Holdenby disguised as a rustic, was still active; Clavering of the Post Office was usefully placed; a sailor, a physician, well-dressed women, poor people, and apparently ordinary people were all at various times part of the line of communication that Charles succeeded in maintaining, albeit imperfectly, with his wife and his supporters.

The laundry woman, Mary, had access to Charles's rooms during the day when they were empty and unguarded, and it was simple for her to conceal letters under the carpet or behind the wall-hangings and to indicate to the King where she had hidden them. In this way, with the help of Abraham Dowcett, Napier of the town, and the tailor, David Murray, a plot was hatched in February for making a hole in the ceiling of Charles's room through which he could make his way to an upper storey and so to an unguarded part of the Castle. But Hammond's vigilance was too much for them and the plans were revealed. Mrs Wheeler and Mary, with other servants including (mistakenly at this time) the royal barber were dismissed. Charles would not allow a Parliament man nor a soldier to approach him with a razor and preferred to let his hair and beard grow.

It was about this time that Charles started communicating with Titus on odd scraps of paper, some no more than one inch across, disguising his handwriting and using a cypher for the most important parts of his messages. Parliament became suspicious enough to order Hammond to search his room. Charles surprised the Governor while he was doing so, there was a scuffle in which the King received some small injury, but he succeeded nevertheless in throwing his papers into the fire before Hammond could get them.

Charles's position certainly looked brighter in the spring. The Scots were ready to cross the border in his support, Irish troops had promised help, in South Wales Colonel Poyer declared for the King, all over the country discontent and royalism were joining hands. Cromwell sent Ashburnham and Berkeley to the Isle of Wight in one

more attempt at compromise, but Charles gained far more from the welcome contact than he gave; for why should he compromise when events appeared to be going his way? The one essential was escape.

Henry Firebrace was the leading spirit in the fresh attempt, and he was confident enough to assure the Scots that the King would shortly be joining them. He communicated with Charles through a hole he made in the wall of Charles's bedroom, underneath the tapestry hangings, and Charles knew precisely how and where to surmount the two castle walls that stood between him and the two horsemen who would be waiting with three horses beyond the outer defences. He was convinced he could get out of his chamber window for he had tried the space with his head and refused Firebrace's urging to tamper with one of the bars. On the coast Newland would be ready with a boat to take him to the mainland, he would ride straight to Edward Alford's house at Arundel and thence be conducted to Queensborough in Suffolk where a ship would be waiting.

On the night of Monday March 20 all was ready; but the King failed to come: his body would not follow where his head had gone and after a desperate struggle in which he feared he would not be able to move either way he was thankful to get back into his room. In a note to Titus Charles begged that his friends should be given thanks for their part in the enterprise and almost immediately further plans were set on foot for weakening one of the bars on his window with aqua fortis , or nitric acid, after which it might be pulled from its socket. Jane Whorwood obtained the acid in London but it was spilt on its journey to the Isle of Wight. A further supply was procured which was later found in Charles's room, but an alternative means of removing the bar was also provided by the 'fat plain man' who brought a 'hacker' to Charles — an implement that could convert two plain knives, such as the King possessed, into a saw that would cut through the bars of his window. But too many people were involved in this plot and on June 2 Hammond was able to disclose it to Parliament, although not before a bar of Charles's window had been actually cut. 'He hath one or two about him who are false', reported Hammond, and he sent some of the faithful, including Titus, Boroughs and Cresset away from the Island. They thought of setting fire to the Castle before they left and rescuing the King in the confusion. More practically, Titus managed to stay behind.

While the King was vainly trying to escape, what was virtually a

second civil war was flaring round the country. Reaction had set in fuelled by sequestration, taxation, intolerance, food shortages, censorship, repression. The reaction had not gone the way of the Levellers but the way of the Royalists. By the beginning of May the whole of South Wales was in revolt and Cromwell was hastening westwards. Berwick and Carlisle had been taken for the King, Surrey and Kent, even the Eastern counties were in arms. The Prince of Wales was at sea with a Dutch fleet, and reached the mouth of the Thames, the Duke of York escaped from St James's on April 21 disguised as a girl and reached Holland. In May there was mutiny in the navy. On July 8 a Scottish Royalist army at last crossed the border under the Duke of Hamilton. If Charles had been in any place but the Isle of Wight, separated by sea from his supporters, a Royalist force might have rescued him to lead his armies; if he had gone overseas he might, even now, have been landing with the Prince of Wales on English soil to fight once more for his Crown. Instead there was only expectation and hope, followed all too soon by despair. At the beginning of June Fairfax defeated the Royalists at Maidstone and turned to deal with those in Essex; early in July Cromwell completed the suppression of Charles's supporters in Wales and marched northwards to deal with the Scots, whom he defeated at Preston on August 17. Hamilton was captured shortly afterwards and the capitulation of Colchester on August 28 marked the end of the war in the Eastern counties. Charles was helpless.

Hammond meanwhile was doing what he could for his captive. Charles found the wine poor and the bed-linen not over-clean. But a golf course was made within the outer defences of the Castle, in one corner of which a little summer house was built where he could watch the sea and the shipping and the soft line of green hills which were not visible from his room. He spent nevertheless many hours indoors, praying, reading, and writing. One of his concerns was to record his own reactions to the condition in which he now found himself, another — as far as he could understand them — the reasons for the conflict between himself and his Parliament. As he wrote of the present he could forget his attempts to escape and the defeat of his followers in a resignation so complete that it seemed to embrace whatever the future might bring. His mood of resignation was fostered by the scant communication he had at this time with his family; he complained to Titus that his wife's letters seemed to miscarry, and

there was a hint of bitterness in his remark that he received answers to other letters but not to those he sent to her.

When he wrote of the past he explained, and sometimes excused, his actions. If he had called Parliament to any place but London, he believed, the consequences would have been different; when he left Whitehall he was driven by shame rather than fear, in order not 'to prostitute the Majestie of My Place and Person, the safetie of My Wife and Children'; he passed the Triennial Act 'as gentle and seasonable Physick might, if well applied, prevent anie distempers from getting anie head'; when his wife left England it was not even her going that hurt most but the 'scandal of that necessity'. He was bitter at the publication of the private letters to his wife, which had been captured after Naseby. No man's malice, he wrote, could 'be gratified further by my letters than to see my constancy to my wife, the laws, and religion: bees will gather honey where the spider sucks poison . . . the confidence of privacy may admit greater freedom in writing such letters which may be liable to envious exceptions'.

He harked back to the death of Strafford, which was always on his mind, acknowledging his greatness, his abilities, which 'might make a Prince rather afraid, then ashamed to emploie him in the greatest affairs of state'. Charles had been persuaded to choose what appeared 'safe' rather than 'just' and the Act that resulted he described as a 'sinful frailtie'. To his son he wrote that the reflections he was putting down were mainly intended for him, in the hope that they would help to remedy the present distempers and prevent their repetition. The fact that the Prince of Wales had experienced troubles while young may help him 'as trees set in winter, then in warmth and serenitie of time' frequently benefit. He urged him to be Charles 'le bon' rather than Charles the Great, to take heed of abetting faction, to use his prerogative to remit rather than to exact and, above all, to begin and end with God.

Charles also made translations from Latin, which he had always enjoyed doing, he wrote favourite passages in the fly-leaves of some of his books, he read the Bible, Bishop Andrewes's sermons, Hooker's Ecclesiastical Polity , Herbert's Divine Poems , and many more religious works. For lighter reading he chose Spenser's Faery Queen and Tasso's Godfrey of Bulloigne . He kept Bacon's Advancement of Learning by him, carefully continuing his annotation. He could still get pleasure from books. Although, as he wrote, they had left him 'but little of life, and onely the husk and shell' yet 'I am not old, as to be wearie of life', he said, and he wrote over and over again in his books: Dum spiro Spero.

The second civil war ended the possibility of any agreement with Cromwell and the army. Charles was once more the Man of Blood and the renewed fighting was a punishment for not having dealt firmly with him before. Charles was all the more glad when Parliament sent Commissioners to Newport to treat in early September 1648. In the absence of the army, which was still in the field, it was a Commission dominated by Presbyterians and it contained several of Charles's old friends.

After a second military defeat Charles had little bargaining power, yet such was the aura of kingship that negotiations were planned and conducted almost as though he were a free monarch. On giving his word not to escape he was conducted to Newport on September 18 and settled in the best state the town could offer, which was at the house of his friend, Colonel Hopkins. Negotiations were conducted in the school house where Charles sat on a chair of state, he was allowed several chaplains, advisers and friends, who included Richmond, Hertford, Southampton, Lindsey and Ashburnham. Some came with their wives, so that evenings once more became social occasions, while during the day Charles again enjoyed the exhilaration of horse riding.

But, although he put on a show, Charles had little spirit for the negotiations. He was determined to give nothing away and obtained the agreement of the Commission that no section should be held binding until the whole proposed treaty had been discussed. Forty days had been allowed for discussion and week after week went by with no tangible result. Charles's friends believed that the Independent faction was playing for time until Cromwell and Fairfax had completed their military work: with the army once more in control there would be an end to negotiations and Charles's life would be in danger. But to all plans for escape he turned a deaf ear. If the Independents were playing for time, he was too, though to what end he was not quite sure. He made concession after concession, sometimes going further than he had done before, sometimes bitterly reproaching himself for doing so, sometimes assuaging his conscience by reminding himself that by his covering stipulation he need hold nothing binding until the conclusion of the whole treaty. When he did consider escape he was brought up against his parole. He was particularly evasive over Irish affairs but finally agreed to settle Ireland as Parliament should decide. In the general coming and going occasioned by the treaty negotiations his communications with France and Ireland

had been easier and he knew that his wife and Ormonde were still planning a Royalist rising in Ireland. In a burst of hope he saw himself escaping and joining them in the field, and he wrote to Henrietta-Maria, telling her he was acting under duress and warning her not to be deceived. 'If the rumour of his concessions concerning Ireland', he wrote to her, 'should prejudice my affairs there, I send the enclosed letter to the Marquis of Ormonde, the sum of which is to obey your command, and to refuse mine till I certify him I am a free man.' He was acting just as, seven years earlier, she had told the Papal agent he would act.

But he had, on the whole, little confidence either that the concessions he had appeared to make would help him or that he was right to have made them. Night after night he went through the day's proceedings with his secretary, Sir Philip Warwick, meticulously, yet with a growing weariness, on one occasion turning away from Warwick and others in the room to hide his tears. Finally he yielded to his friends' importunities and agreed to escape. But scarcely had he done so when he reversed his decision. Signalling privately to Bowring one day to follow him into an inner room, he told him he had just received letters from overseas advising him not to leave the Island and assuring him that the army had no power to harm him. 'So now', said Charles,

if I should go with you, now, as I thought to have done, and things fall out otherwise than well with me; and the rather because my treaty hath had so fair an end . . . and that my concessions are satisfactory, and especially since I have received this advice (you guess from whence it comes) I shall be always blamed here after . . . Therefore I am resolved to stay here, and God's will be done.

It was Charles at his most typical. The letter was obviously from Henrietta-Maria and he was once more tormented with anxiety that she might blame him for doing the wrong thing if he refused to follow her advice. She had also persuaded him to cover his negotiations with a rosy, but false, hue of optimism which he had not felt before. He did not appear to question the reason for her anxiety that he should remain on the Isle of Wight at this time — as once before she had urged him to stay in England.

By the middle of October Charles had agreed, as he had done before, to grant Presbyterianism for three years; he still refused to take the Covenant, but he allowed of 'counsel and assistance' by a Presbytery at the end of the three years. The militia he agreed to abandon first for ten years, but later he conceded twenty. He would on no account

consider the death penalty for his supporters, but agreed to punishments of fine and the confiscation of part of their estates. But by this time his mood had again changed and the optimism had faded. On October 9 he wrote to Hopkins in despair: 'notwithstanding my too great concessions already made, I know that, unless I shall make yet others which will directly make me no King, I shall be at best but a perpetual prisoner . . . To deal fairly with you, the great concession I made this day — the Church, militia, and Ireland — was made merely in order to my escape, of which if I had not hope, I would not have done.' To return to prison now, he said, 'would break my heart, having done that which only an escape can justify'. My only hope, he concluded, 'is that now they believe I dare deny them nothing, and so be less careful of their guards'.

One thing Charles did continue to deny them and that was Episcopacy; he would not give it up as his personal religion and he would not suppress it so long as he had power. He had made concessions to Presbyterians and would foster a fairly wide toleration but from that position he would not budge. Partly on this rock, but partly because there never really was any hope of success, negotiations by the end of October had virtually ground to a halt. On November 12 Charles was enquiring urgently of Hopkins about tides and had decided to make for Gosport on the night of the 16th or 17th when Newland would once more have a boat ready. But it seemed that he no longer had any hand in ordering his own affairs. Hammond knew of his plans on the 13th and the enterprise was necessarily abandoned at the very time that Jane Whorwood reported from London through Sir John Bowring that a plot was actually in being to murder him, and that Sir Peter Killigrew came to warn him that the army intended to bring him to London for a public trial. In his bitterness Charles complained that his friends had failed him and his melancholy grew.

While negotiations had been proceeding at Newport the Army was once more facing its own problems. Internally it had to deal with the Levellers, who were still seeking their own form of constitutional settlement based on universal suffrage and a wide toleration, and particularly with Lilburne, who was still asserting that they could not in law bring the King to trial and that to do so would be to open the door to further arbitrary government. But the trial of the King was precisely what the majority of the soldiers now wanted and Ireton embodied their point of view in a Remonstrance which was published

in the middle of October. But the army had to face the fact that Parliament was still negotiating with the King and that a conjunction between Parliament and King, or the King's escape, might at any moment jeopardize their military victory. At the end of November Ireton's Remonstrance was laid aside by Parliament and Fairfax, albeit reluctantly, once more began to move with his troops towards the capital. They were continuing their discussions with the Levellers, but while the most articulate soldiers were talking the majority could see only the black and white of the situation and by the beginning of December events had begun to move quickly.

On November 27 Hammond, on his refusal to take orders from anyone but Parliament, was removed from the Isle of Wight and the following day placed in custody by the Army, whose headquarters were now at Windsor. On the 30th Lieutenant-Colonel Cobbett and Captain Merryman arrived at Newport with a company of soldiers. On the night of December 1 his friends were urging Charles that now, if ever, was the time to escape. Captain Cooke assured him that he had horses and that a boat was ready. He had the password, and to demonstrate to Charles how easy escape would be he passed and repassed the guards with Richmond. But Charles was overcome with weariness and with inertia, his old fatal disease, and in spite of all he had said he now declared he would not break his word or his parole; he had made an agreement with Parliament and he would keep it. They argued desperately that it was the Army they were now dealing with, and not Parliament. Charles took no notice and retired to bed. The following morning at daybreak he was roused by soldiers under the command of Cobbett and hurried off without his breakfast. As one of the soldiers tried to follow him into his coach Charles thrust him back. 'It's not come to that yet!', he exclaimed.

He was taken across the Solent to Hurst Castle, a defensive fortress surrounded on three sides by sea, connected at low tide with the mainland by a thin strip of gravelly sand. The Governor was uncouth but not unkind; the rooms were so dark that candlelight was needed right through the day; the King's exercise was merely a daily walk along the shingle where, as usual, he outstripped his companions; the air was dank with winter mist and vapours from the marshes of the mainland. His only solace was in the passing ships that reminded him of freedom and of his own navy. While he was there Colonel Pride, on December 6, stationed himself with a body of musketeers outside the doors of the House of Commons, turning back the Presbyterian

Members as they arrived. He did the same the following day, excluding some 96 altogether, leaving about 56 sitting Members.

Charles was kept at Hurst Castle for a little over two weeks. On the night of December 17 he was awakened by noise and, ringing his little silver bell, sent Herbert to investigate. It was the drawbridge being let down to admit Colonel Harrison, who had been one of the most vehement in demanding the death of the Man of Blood. Charles was convinced that he was come to murder him in that bleak and desolate place, but the reality was reassuring, for on the 19th he was conducted by Cobbett to Windsor. He almost enjoyed the journey. As he was approaching Farnham he noted a fine-featured, splendidly-dressed Officer in command of the welcoming party. On enquiry he learned it was no other than Harrison. That evening after supper Charles perceived the same officer standing across the room from where he stood in his accustomed place in front of the fire. He beckoned him to him and, taking him apart, asked if he really had intended his death at Hampton Court? The answer was no doubt evasive, but the question shows that Charles had a real fear of assassination at that time.

At Bagshot Charles dined with Lord Newburgh. One more hope remained. Newburgh owned some of the fastest horses in England and one of them would be ready if the King could arrange to change his mount. Charles was prepared but again fate — or was it his captors? — had arranged that the horse should become lame shortly before his arrival. There was encouragement from the people who cheered him as he passed towards Windsor, some even crying out for God to bless him. The Castle, where he arrived on December 23, was more like a fortress than ever, for it now held many Royalist prisoners, including his kinsman, friend, and counsellor, Hamilton. Christmas was bleak and lonely. But Charles watched the river from the terrace where he took his daily walk and looked towards Eton with its memories of his first tutor and of bathing parties with Buckingham. A little of his old state was preserved in the serving of his meals, but gradually it was depressed, his attendants were dismissed. As he continued his hurried walking up and down the terrace, pausing to gaze out over the river, his hold on all that he had known throughout his life perceptibly loosened. He had no communication now with the wife who had borne him nine children in fifteen years, nor with his two eldest sons, nor with the daughter whose marriage might have helped his fortunes, nor with that baby, now a little girl of nearly five, who

represented his last contact with Henrietta-Maria. Only Elizabeth and Henry, the children of his happiest years, remained near him — like himself, prisoners.

Charles was to remain at Windsor until 19 January 1649, while his opponents discussed his fate. A strong party of soldiers still urged his trial and condemnation. Fairfax shrank from such a procedure and kept outside the discussions. Lilburne and his party continued to assert that neither Parliament nor Army had the legal right to try the King and that to do so would be to open the door to further arbitrary government. Cromwell hesitated; even Ireton hung back. The Earl of Denbigh was sent with a secret message to Charles at Windsor which could have paved the way to further negotiation. Charles refused to see him. He would struggle for terms no longer; he could not consult his wife; he would no longer plague his conscience to determine what was right; there was no need to prevaricate; as he had written, they had left him with but the 'husk and shell' of life; he merely had to make his peace with himself, which meant with God, and he was helped by the wide, grey river that symbolized the best of his life. He believed that, except for the betrayal of Strafford, he had acted well; he believed his son would reign after him; he believed his captors were evil men and he knew what to expect. It was consequently easy for him to wait. As he had written: 'That I must die as a Man, is certain, that I may die a King, by the hands of My own Subjects, a violent, sudden, and barbarous death, in the strength of My years, in the midst of My Kingdoms, My Friends and loving Subjects being helpless Spectators, My Enemies insolent Revilers and Triumphers over Mee . . . is so probable in humane Reason, that God hath taught Mee not to hope otherwise.'[1]