Four—

Desire, Delay, and the Fourth Dimension:

The Large Glass

When Duchamp Returned to Paris from Munich in the late summer of 1912, he did not go back to his old life. During the months that followed he drew away from the cubist circle around Gleizes and Metzinger, took a job as a librarian in the Latin Quarter, and exchanged the studio in Neuilly, where he had been close to his brothers' house in Puteaux, for one in Paris. He had a single—but very large—artistic project on his mind, the one that would occupy him off and on for over ten years, and which we know as the Large Glass, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Plate 4).

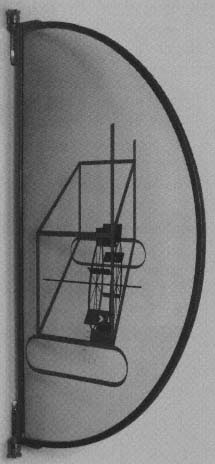

Significant as this moment was, we need to resist the temptation to think that Duchamp already had his later, radical departures in mind. He yielded to this temptation himself later on when he claimed that Munich had been "the scene of my total liberation," making it seem as if the readymades and perhaps even the later abandonment of art were already on his agenda in the fall of 1912; clearly, for reasons we will come to soon enough, they were not. Unusual as the Large Glass would be, it was still a picture, and his first idea was to make it, as one note said, on "a long canvas upright." The turn to glass came during 1913, and with it the first experiment in painting on glass, the Glider Containing a Water-Mill in Neighboring Metals (Fig. 30), which pictured a made-up device—probably inspired in part by Roussel's machines—

that would take its place in the bachelor imagery. One reason for going to work in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Genevieve was that the job's light duties gave the chance to read about geometry and perspective, subjects that now took on new importance for him. At the end of 1913 he drew his first full-scale study for the project, on the wall of the studio he had rented in the Rue Saint-Hippolyte, by which time many of the notes he would later publish had already been written down.[1]

Unprecedented as this work would be, it grew directly out of the ideas he had first explored in a more traditional painterly way in Munich; at the same time, it returned to themes and concerns that had preoccupied him earlier. The conceptual germ of the Large Glass was the relationship of virginity to bridehood he had begun to focus on in Germany and which allowed him to replace his interest in linear movement through space with attention to a kind of motion that was purely formal and intellectual. But physical motion had always appeared in Duchamp's work partly as an evocation of inner experience, his own feelings of disillusionment, desire, or sadness, and the anonymous energy of the Bergsonian deep self; to abandon physical motion as he did in Munich was on one level simply to accord his concern for interior life the independence he had already allowed it in some of his previous work. In Dulcinea he had recorded his fantasy of unclothing a female body, superimposed on its movement through a succession of physical positions; and earlier, in Paradise , he had depicted a form of purely psychic motion by showing figures who were already inwardly banished from the garden of innocence where their bodies still remained. The Large Glass would revive the motif of "stripping" from Dulcinea , but the motion in it would be more like that in Paradise , a fluid or unstable state of consciousness, a purely mental or psychic movement occurring in a frozen moment of time. One other feature of Duchamp's early work would reappear and blossom forth here too: his irony, now become so prominent that it wove a thick veil of uncertainty around the picture's intentions and his own in making it.

The irony is bound to make its impact first, its layering so deep that some have thought it reaches unalloyed to the work's core, and in a way, as we shall see, it does. It begins with the title, invoking an unexplained cast of characters (who are a bride's bachelors?) and concluding with the nonsensical même , "even," calculated to send the mind off on

Figure 30.

Duchamp, Glider Containing a

Water-Mill in Neighboring Metals

(1913-15)

a path to nowhere. The puzzle continues with the unprecedented collection of symbols that populate the picture space, raising to a higher level Duchamp's old tactic of drawing us in and keeping us at bay by holding the promise of meaning forever just out of reach. The restless attack on the public's expectations continues in the notes, their goal of letting people know what the work was about undermined by publishing them episodically and in the same fragmentary form, on odd-shaped and variously acquired bits of paper (some on restaurant or hotel stationery), on which he had originally written them down, and even more by their sometimes impenetrable mix of lyrical effusion and playful nonsense, serious metaphysical speculation and pseudo-science, yearning for transcendent experience and unshaken disillusionment.

They include many crossed-out passages (Duchamp no longer means what they say), along with references to forms he did not include and ideas he merely played with or subsequently abandoned.

The notes are just as important to the work as the visual images. Duchamp several times said that his original intention had been to publish notes and picture together, allowing viewers to move back and forth between them in the way readers use a mail-order catalogue. Moreover, many people in Duchamp's lifetime experienced the work first through the notes, since the picture's only public showing before World War II took place in Brooklyn in 1926 (he had decided to leave it permanently unfinished three years earlier). When it was being sent back to Katherine Dreier, Duchamp's friend and patron who had agreed to buy it in 1921 (the original owner-to-be, Walter Arensberg, having moved to California, too far away to ship the delicate glass), the two plates broke, a misfortune no one knew about for some years because they remained crated up. Duchamp, who had by then developed a thorough commitment to chance and accident, giving his life over to unpredictability and developing a whole series of works to sound the theme, declared himself delighted; all the same, he spent a month during 1936 repairing the picture so that it could be exhibited again. Two years previously he had tried to preserve it for the public in another way, by publishing a large collection of notes in The Green Box of 1934. In the same year André Breton used the notes to write the first essay that brought the picture to the attention of a wider public-even though he had not seen it.[2]

Irony takes many forms in Duchamp's notes. The bride is referred to sometimes as an apotheosis of virginity and sometimes as a pendu femelle , a hung or suspended female body, now as characterized by "splendid vibrations" and now as a mechanical object, a motor or barometer. The proportions of the bachelor section were worked out with painstaking precision, and yet the objects only pretend to work in a mechanical way; at one point their motion is supposed to be powered by the fall of brandy bottles, or lead weights shaped like brandy bottles. (It was in this section, however, that Duchamp wrote at one point "much too far-fetched," not the only sign that many of the notes merely play with possible themes or ideas, so that one should not try to find significance in all of them.) The bachelor glider or chariot sings

"litanies" as it moves, which include "slow life, vicious circle, onanism ... cheap construction ... eccentrics"—a kind of music for the loneliness of provincial life. How expansive and yet sour—at once serious and nonsensical—Duchamp's imagination could be in his notes appears for instance in some ideas about the components of the "wasp" or "sex cylinder" that was the center of the bride.

The pulse needle in addition to its vibratory movement is mounted on a wandering leash. It has the liberty of caged animals.... This pulse needle will thus promenade in balance the sex cylinder which spits at the drum the dew which is to nourish the vessels of the filament paste and at the same time imparts to the Pendu its swinging in relation to the 4 cardinal points.[3]

Overall, as one heading declared, it was to be un tableau hilarant , not exactly "a hilarious picture," as the phrase has usually been translated, but one that could provoke a state of beatific—but also silly—satisfaction, like the happiness of a drunk.

In all this there is much of Roussel, with his "delirium of imagination." One note, not directly connected to the bride and the bachelors, was titled Erratum Musicale (Musical Printer's Error ), recalling Roussel's African "Impressions"—in French a pun on printings—and taking the form of a three-part canonic song, to be sung by Marcel and his sisters Yvonne and Magdeleine, with a text composed of—Roussel's favorite reading—a series of dictionary definitions, here of the verb "to print." (The text read: "To make an imprint mark with lines a figure on a surface impress a seal on wax.") The result showed that Duchamp understood the place of verbal play in Roussel's disorienting scenes, and that he too could use language to create strange worlds by following out verbal links on their own.

On his return to Paris from Munich in 1912 Duchamp took an automobile trip with Apollinaire, Picabia, and the latter's wife Gabrielle Buffet (the same companions with whom he had gone to see Impressions of Africa the previous spring) to her native village in the French Jura; along the way he wrote some notes for a pictorial project inspired by automobile travel. Here the car was "the machine with 5 hearts, the pure child of nickel and platinum," but it was also "the headlight

child," l'nfant phare , its beam preceding it along the road like a comet with its tail in front (and perhaps calling up the idea of an opening flourish, en fanfare ). I admit I do not know what Duchamp meant by associating the road with "the chief of the five nudes" (5 nus , however, reads also as "nude breasts" in French), but the image allowed Duchamp to move back and forth between lyricism and nonsense. First he wrote: "The Jura-Paris road, having to be infinite only humanly, will lose none of its character of infinity in finding a termination at one end in the chief of the 5 nudes, at the other in the headlight child"; but the next paragraph took it back: the road was only indefinite, not infinite, and while it would begin in "the chief of the 5 nudes," it would not "end in the headlight child." The picture that was somehow to contain these images was equally mysterious, using wood as a primary material, although Duchamp also spoke of the "size of the canvas."[4]

Being more extended and more developed, the notes for the Large Glass provide both more passages that are opaque or indecipherable and more elements of stable description. The latter include the strange but finally identifiable objects that people the picture space. The bride's section, the top half, holds two main elements, the bride herself on the left (the image taken whole as a section or cutout from the painting of the same subject done in Munich) and her "halo," also referred to as the "milky way," across the top center. The three nearly square openings in the halo reproduce images Duchamp obtained by photographing pieces of gauze hung in front of an open window, allowing them to be blown and stretched by the breeze; thus they bear the name "draft pistons," the first of several testimonies to the role assigned to chance in the Glass. A second appears in the eight small marks or dots visible below the milky way on the right-hand side of the top section; their locations were obtained by shooting matchsticks dipped in paint out of a toy pistol (the ninth is less easily seen, inside the milky way).

The bachelor imagery is more complicated. In the middle sits an object Duchamp called a chocolate grinder, its three circular drums atop a table resting on "Louis XV legs" and attached by a rod to a scissors-like mechanism above. He said that the grinder was like one he knew from his days as a lycée student in Rouen; actually it seems that the device Duchamp remembered, representing it with techniques of mechanical drawing, was a mixer, used to refine and flatten the rather

rough paste of chocolate and sugar produced by other, perhaps less picturesque grinding machines.[5] Duchamp seems to have been drawn by the combination of the machine's phallic imagery and its relation to chocolate, with its suggestion of sweet physical satisfaction; but in the notes he cast the sexual reference in an onanistic mode, through what he called an "adage of spontaneity: the bachelor grinds his chocolate himself."

To the left is the glider or sled or chariot (Duchamp used all three terms), enclosing a waterwheel in its center. Water was imagined to fall on the wheel, but this did not cause the glider to move, since it was powered by the bottle-shaped weights; instead, wheel and waterfall were somehow associated with a landscape planned for the glider's interior, but which makes no appearance in the Glass. Above the glider are nine shapes that Duchamp referred to variously as "malic molds" or "uniforms and liveries," each representing a particular male occupation: priest, delivery boy, gendarme, cuirassier, policeman, undertaker, flunky, busboy, stationmaster. As several writers have pointed out, these molds seem to have been inspired by mail-order catalogue illustrations of male clothing and costumes, which may also account for the odd assemblage of jobs and functions.[6] They are connected by rods (whose shapes followed those Duchamp obtained by dropping meter-long threads from a one-meter height, producing what he called "standard stoppages"; we will come to these in chapter 6) to seven sieves or parasols suspended over the chocolate grinder. In the imaginary operation of the bachelor machine, the molds would fill with "illuminating gas," apparently a mode of male sexual energy; the gas expanded when it heard the "litanies of the chariot," rising out of the molds and losing the individualized shapes imparted by them, then moving as "spangles" through the rods to the sieves or parasols; here it was converted into liquid form and, Duchamp went on, experienced "dizziness" and spatial disorientation, before falling along a corkscrew-like trajectory into the bottom right of the bachelor space, where it would end in a kind of orgasmic splash.

Above the region of that splash, in the upper right section of the bachelor space, are three circular constructions that seem to float in air, surmounted by a smaller circle. The larger shapes were taken from charts used to test vision and thus bore the name témoins oculistes or

"oculist witnesses." The smaller circle was a magnifying glass. All were associated both with the splashes below and with visual effects planned—but never put in place—for the space above them, a boxing match and something called the "Wilson-Lincoln effect," an optical illusion that showed alternately as one president or the other (recalling the visual ambiguities of The Passage from Virgin to Bride ).

More details about the Glass's various parts and workings could be provided (and have been by others), but they would only underscore the point that these are games with an extremely elaborate but never fully specified set of rules, where precision and uncertainty combine to produce a world whose fluid energy never quite coalesces into stable forms.[7] As the consciousness behind it all, Duchamp seems at once to appear and to fade from view, projecting his thoughts and intentions toward a space where they might become visible, then remembering that imagination retains more freedom if it remains unrealized. Despite all its irony, however, the Large Glass was not just a big joke. At one point Duchamp distinguished between an irony of negation and one of affirmation, differing only in the form of laughter proper to each.[8] The Glass seems to contain both forms: for all the recurrence of seeming nonsense and contradiction, certain ideas are clearly enough developed to project the outlines of a coherent story, one that uses irony and seriousness at once to nourish and to exclude each other. In The Green Box of 1934 these ideas all appear together in a series of consecutive pages devoted to the conceptual elements that rule the picture.

When these elements are combined they yield a paradox that simultaneously justifies and undermines the irony that so infuses the project. The key to the Large Glass is that the stripping referred to in the title does not take place, at least not in the ordinary world of physical experience we usually regard as "real." Instead, the titular nudity exists wholly in the spheres of desire and fantasy, while the actual bride, if we may speak about an imaginary figure in this way, remains distant from the bachelors and untouched by them. On one level they are merely figures in her imagination, and the whole play of fantasy and invention echoes Roussel's "Impressions" of an Africa he had never seen.

The nonoccurrence of the action described draws the many ironies of the work's symbolic inventory into the void of meaning created by the final adverb of the title, and Duchamp announced the absence at the

heart of his work by giving it a subtitle, provided at the very start of The Green Box : "Delay in Glass." A delay is a space of time in which something expected to happen does not occur, a moment stretched out while a promised arrival keeps us waiting. The subtitle was followed by a "Preface," in which the sexual energies figured by the "waterfall" and the "illuminating gas" (neither of which were visible in the picture) were said to produce an "instantaneous state of Rest." The Glass's subject was thus a moment removed from time like the earlier "passage from virgin to bride," an instant of imaginative transformation in which no physical action takes place. Duchamp links the imagined nudity of the bride in the Large Glass to the virgin purity distilled by the notion of such a passage when he names the condition her stripping brings about: "an apotheosis of virginity."

The import of such purity should not be confused with any religious celebration of virginity. In Duchamp's world the desire that religion urges us to direct toward higher things finds its satisfaction in itself. The second time he wrote the phrase "apotheosis of virginity," Duchamp glossed it by adding "i.e. ignorant desire, blank desire," that is, desire unrelated to any definable external object, desire fulfilled in its present state of desiring. To this desire was added "a touch of malice," presumably against those external objects that might claim to know better than the bride what she wants. That her desire would not become dependent on them was indicated by calling her "this virgin who has reached the goal of her desire" and "this virgin who has attained her desire"—a desire already fulfilled within her virgin state of bridehood.[9]

The word Duchamp repeatedly uses in his notes to describe what happens when the bride reaches "the goal of her desire" is "blossoming" (épanouissement ), the condition figured by the halo that is "the sum of her splendid vibrations." A halo and vibrations require some kind of energy to feed them, and Duchamp certainly made sexuality its generator, or rather, sexuality drawn into the magnetic field of idealization, for where else does bridehood exist? The precise source of the bride's halo appears in the most concise summary of the program for the Large Glass, which describes the picture as "an inventory of the elements of this blossoming, elements of the sexual life imagined by

her the bride-desiring." Hence it is the bride's imagination that engenders her halo, and on one level the whole action of the painting takes place inside her head, making the picture an image of her world of ideas and visions, where even the bachelors (whether they exist apart from her imagination of them or not) are only personae in her drama of self-presentation; she orders them—communicating "electrically" across the space that separates them—to carry out, in their heads, a stripping that draws them into her imagination of sexual life. This would seem to be one reason why the bachelors are plural: plurality is not the form of male existence that can put an end to virginity—once one man has initiated a virgin into womanhood others can no longer do it—but only the form that exalts it as the focus of multiple and unfulfillable desires.[10]

But even the bride's imagination does not fully control the nudity of the picture. As she draws the bachelors into her world, her unclothing becomes a matter of multiple representations and appearances, the complex product of separate but interacting fantasies. The bachelors—whether in the form imagined by the bride or as separate beings—envision her nudity in one way, she in another; it is just this difference between their mental vision and hers that projects her nudity into a space that neither she nor they can fully define, an imaginary space between two irreconcilable ways of representing it.

In this blossoming, the bride reveals herself nude in 2 appearances: the first, that of the stripping by the bachelors. the second appearance that voluntary-imaginative one of the bride. On the coupling of these 2 appearances of pure virginity—on their collision, depends the whole blossoming, the upper part and crown of the picture.[11]

To say that the two modes by which "the bride reveals herself nude" were "2 appearances of pure virginity" meant that they were two separate ways that virgin nudity was envisioned or imagined: a male way that submits female bodies to male fantasy, and a female one that directs the play of desire so that the unclothed virgin body stands as the sign of its own apotheosis. Visually Duchamp associated the first with

"clockwork movement ... gearwheels, cogs, etc.... the throbbing jerk of the minute hand," whereas the second "should be the refined development of the arbor type. It is born as boughs on this arbor type."[12] From this contrast derives the curiously conventional difference between male and female imagery in the picture, the bride lithe, shapely, and freely swinging in her suspension, the bachelors bulky, mechanical, and noisily active. The coupling of such visions of femininity and sexuality was also a "collision," a smash-up that leaves the trains of desire still struggling to get back on the track toward their destinations.

In such a schema, bride and bachelors sought each other across a divide they could never quite bridge. Duchamp arranged the male and female realms so that they remained without contact, by inserting a "cooler" between the picture's two halves. But this cooler also expressed "the fact that the bride, instead of being an asensual icicle, warmly rejects (not chastely) the bachelors' brusque offer": she wants what they do, but in her own way, at once needing and denying their way of desiring her nudity, as a condition of her blossoming. Duchamp even referred to her "motor," activated by love gasoline (essence d'amour , as Paul Matisse points out, means something more than that) and the sparks of desire, as showing "that the bride does not refuse this stripping by the bachelors, even accepts it, since she goes so far as to help towards complete nudity by developing in a sparkling fashion her intense desire for the orgasm."[13] At this point it was possible to think about the bride's blossoming as coming not just out of the "collision" between the bachelors' desire and the bride's, but also as a "conciliation" that was "unanalyzable by logic" and issued in "the blossoming without causal distinction." But even when directed toward orgasm, the bride's desire remains unsatisfiable within the conditions of the picture; one note referred to her blossoming as "the image of a motor car climbing a slope in low gear. The car wants more and more to reach the top, and while slowly accelerating, as if exhausted by hope, the motor of the car turns over faster and faster, until it roars triumphantly." The "triumph" is of desire intensified by the exhausting hope of a fulfillment that remains out of reach.[14]

The notion of delay that located the Glass's action in a moment that never arrived also described the picture's relationship to representation

and meaning. Duchamp said he used the term as "a way of succeeding in thinking that the thing in question is no longer a picture"-that it was not a visual representation of some situation outside it, but a selfcontained and self-referential space. The various forms of irony with which the project was surrounded, keeping the meaning promised by the title, the symbolism, and the notes just beyond the grasp of us the viewers, was another form of delay, making the picture itself an icon of perpetually forestalled communication. Years later, in declaring how much pleasure looking at the Glass still gave him, Duchamp referred to it as "un amas d'idées," a heap or mass or—perhaps the closest translation—hoard of ideas, gathered up and preserved against despoliation.[15]

Among the ideas Duchamp treasured in this way were those given voice in the note on shop windows, where the truth that the world we inhabit is external to ourselves is proved by the disillusionment that comes when we attempt to satisfy desire with the objects life offers. The personae of the Large Glass remain forever in the condition of the window-gazer, whose state of being is expanded and animated by desire without ever experiencing the regret and disillusionment that follow from material possession—here even from seeing with physical senses. They never have to complete the "round trip" that is the penalty of breaking the glass. By creating a permanent state of delay within which the action described by the title cannot occur, the Large Glass suspends the relations between its male and female characters within a metaphysical space much like the one implied by Young Man and Girl in Spring ; what does not take place in the Glass is what has already befallen the inhabitants of Paradise , the physical experience that spoils the imagined unity which precedes it and throws people back into their separate worlds of regret.

Behind the continuity of these themes in Duchamp's work there stood some persistent and recognizable features of his personality, seen in Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia's description of him as repeatedly withdrawing into his own world, as well as the traits of indifference and reserve that Robert Lebel underlined, associating them with those same qualities in his mother. Given that the Large Glass took shape in Duchamp's mind at a moment when he had withdrawn from the Paris art world

and that he continued to keep his distance from it afterward, conceiving the relations between the bride and the bachelors, and dedicating himself to representing those relations, marks an important moment—perhaps the culminating one—in the process by which Duchamp was absorbing and internalizing the qualities of distance and separation that as a boy had troubled him in his mother. In his notes he speaks about the "beauty of indifference."

At the same time that these themes link the Large Glass to elements that seem to have been developing in its maker's consciousness since childhood, their meaning is also illuminated by their ties to some earlier modernists. Duchamp was by no means the first vanguard figure to cultivate eroticism more for the sake of fantasy than for the flesh. A particularly significant predecessor was Charles Baudelaire, whose descriptions of the relationship between urban isolation and heightened poetic imagination have already helped us place Duchamp in the context of developing modernism. Many people in Baudelaire's time and since have taken his poetry as shockingly explicit in its evocation of sexual experience, but close readers have noted how far such understandings are from what the verses actually say. For all his devotion to the details of ordinary experience, Baudelaire was a poet of inner states; when he describes the nudity of his beloved in "Jewels" ("Les Bijoux"), or the smells and textures of her hair in "Locks" ("La Chevelure"), sensual experiences are invoked for their power to expand and dissolve the personality of the poet, for the ability of desire to stoke the fires of imagination, never as an anticipation of satisfactions that are sensual in an ordinary way.

"Locks" begins by evoking the "ecstatic fleece that ripples to your nape / and reeks of negligence in every curl," but instead of leading the poet toward other female body parts, the woman's hair takes him on a distant journey: "As other souls set sail to music, mine, / O my love! embarks on your redolent hair." The voyage leads to a place where (as Martin Turnell observes) the woman has totally vanished from the scene, to be replaced by "a harbor where my soul can slake its thirst / for color, sound and smell." When at the end the poet asks to "braid rubies, ropes of pearls to bind / you indissolubly to my desire," the woman to whom he seeks to tie himself eternally has become "the oasis where I dream, the gourd / from which I gulp the wine of memory."[16]

Such eroticism draws from the vocabulary of sexual realism only to subvert it, riding the power of sexual impulse past its ordinary bodily goals toward regions where memory and fantasy create an imagined world of permanent ecstasy. Nothing would have horrified Baudelaire more than to think that his poetry might be associated with the satisfaction of physical need. As Walter Benjamin understood, the love Baudelaire called up in his poetry is best described as having been "spared, rather than denied fulfillment."[17]

Duchamp seems never to have spoken of Baudelaire as a source for his own projects, but many ties link the two figures. The title of the Large Glass may echo that of Baudelaire's intimate journal Mon Coeur mis à nu (usually translated as My Heart Laid Bare ). Interest in the poet was reviving in the decades before the Great War, and Duchamp's brother Raymond sculpted a portrait of him in 1911 (it can now be seen in the Philadelphia Museum). Another participant in the Baudelaire revival was Jules Laforgue, whose titles Duchamp attached to several of his drawings, and who wrote a well-known encomium that Duchamp may have read. After discussing the urban subjects Baudelaire injected into his work, Laforgue concluded:

He was the first to break with the public.—The poets addressed themselves to the public—human repertoire—but he was the first to say to himself:

"Poetry will be something for the initiated.

"I am damned on account of the public.—Good.—The public is not admitted."[18]

Both the theme of unfulfillable desire and the separation between Duchamp and his audience are further developed in a topic discussed at great length in the notes, and usually with very little of the irony that surrounds other questions: the fourth dimension. Duchamp's speculations about fourth-dimensionality (contained mostly in the White Box , published in 1966) are well known and have been closely studied, but their relationship to the other themes of his project is not always recognized. To him as to the writers on whom he drew, the fourth dimension had little to do with the considerations that made it important at

roughly the same time within relativity theory; it was not concerned about time, but about space and representation.[19]

Duchamp approached the topic of the fourth dimension by way of what is usually called—the idea is less mysterious than it may sound at first—"n -dimensionality." Starting from a figure of any given number of dimensions, n , one can progress by ordinary, commonsense operations to one that has n + 1 dimensions. Thus, in geometry a single point has zero dimensions, but any two points define a line, which has one dimension; any two lines or any line rotated around one of its points creates a plane, a two-dimensional figure; any two planes, or any plane figure rotated on one of its edges, creates a volume, a three-dimensional space or object. If we extend the same thinking beyond the world we know, then it appears that a three-dimensional figure, similarly rotated through one of its plane sides ought to produce a four-dimensional continuum. Physically we can't experience this fourth dimension, but in the mind it seems to bear the same relationship to the world we do experience that familiar elements of that world bear to each other. We understand what it means to progress from one dimension to two, and from two to three: why stop there? Our way of thinking about experience seems to demand that we presume the fourth dimension as a possibility, albeit one into which we can never enter.[20]

Such thinking became particularly intriguing at a moment when Western art was abandoning its traditional devotion to two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional spaces, and seeking to explore visual equivalents of ideas that lay outside experience; the fourth dimension was a common theme in cubist theory. Among the possible lines of speculation that arose at the time, Duchamp focused at the start on two. The first lay in the suggestion that, if two-dimensional images could stand for a world of three dimensions, why shouldn't three-dimensional objects be representations of things existing in a world of four dimensions? In this perspective, solid beings might be conceived as the projections into our world of forms that possessed a higher mode of existence. The second line began with the observation that in a three-dimensional world a two-dimensional plane had to be conceived as having no thickness, yet an actual picture plane does have thickness, because it is covered with material paint. Were it possible to make a

picture that somehow declared its own absence of thickness, then it could mirror the fourth dimension in the other direction, so to speak. It would realize a possibility suggested by certain characteristics of our world but which remains outside our ordinary experience.

Both these speculations contributed to the project for the Large Glass. Duchamp referred to an actual two-dimensional plane that approached the theoretical state of having no thickness as being "ultrathin" (inframince ). One reason for undertaking a painting on glass was that it offered a way to make a picture plane from which the thickness of the paint was absent, simply by looking at the image from the unpainted side. "Painting on glass—seen from the unpainted side—gives an ultrathin."[21] Images that appear on such an ultrathin surface create a reference to the fourth dimension, because any three-dimensional object, seen from a four-dimensional vantage point, also approaches the state of having no thickness. Just as we three-dimensional creatures can pass instantaneously through any purely two-dimensional plane, so would four-dimensional beings pass instantaneously through three-dimensional space; both become "ultrathin" from the point of view of a world that has one more dimension than they possess. Duchamp in an early note referred to painting on glass as a "three-dimensional physical medium in a 4-dimensional perspective," that is, a three-dimensional medium that has lost its thickness.[22]

Thus, to paint on glass was to create a reference to a world to which our usual experience cannot be a guide. Duchamp created the same reference in a second way, by conceiving the bride as a three-dimensional representation of a four-dimensional being, and the image we see of her as "the two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional bride who would herself be the projection of a four-dimensional bride in the three-dimensional world."[23] This may seem very mysterious, since for us as viewers the bride-forms cannot refer to four-dimensional objects in the way that traditional pictures refer to three-dimensional ones. But that is just the point: the fourth dimension cannot be approached by three-dimensional senses. The bride's reference to a world we cannot experience is what gives positive meaning to the puzzling and unrecognizable forms through which she appears to us. In one note Duchamp observed that the forms of the bride

no longer have any relationship to measurability as we know it in the three-dimensional world. The principal forms of the bachelor machine are mensurable, but in the bride the principal forms "are more or less large or small, have no longer, in relation to their destination a mensurability." A bit later he began to develop a distinction between an object's "appearance," as it presents itself to our ordinary senses, and something more mysterious he called an "apparition," produced by a colored form and a "mass of light elements." This is one of the most playful and obscure passages in Duchamp's notes (much of it concerns chocolate), but the notion of an "apparition" is another way to think about the bride as a visitor from a realm that remains beyond the bounds of our ordinary experience, a kind of ghostly arrival from the world of the fourth dimension.[24]

However any of us may regard these ideas—as interesting, curious, or perverse—their importance for the Large Glass lies in their relevance to the story of desire without fulfillment that is told there. Duchamp's program of representing an event, the bride's stripping, that takes place only in imagination is carried out by way of the notion that the female figure in the picture is a four-dimensional being: there is no way that the three-dimensional bachelors can have any physical purchase on a four-dimensional bride. In Duchamp's terms they are ultrathin in relation to her, lacking the dimension that imparts solidity in her world. The dimensional relations in the picture are a metaphor for the nature of the relations of desire that exist between its personae: the desire of the bachelors for the bride is like the desire of three-dimensional creatures for an experience of the fourth dimension that our minds can conceive but our bodies never touch. It is the desire for another kind of existence, which imagination engenders in us.

Although the idea of the fourth dimension refers by definition to a sphere beyond experience, Duchamp sought ways to provide some kind of visual intimation of it. The notes contain a long series of meditations about this, involving plays of interreflecting mirrors and attempts to imagine what a four-dimensional perspective would be like, based on parallels with the difference between two and three-dimensional perception. He even considered that color might be used as an analogy to experience beyond the third dimension, because color, like perspective, "cannot be tested by touch."[25] Most of these specula-

tions are simply thoughts Duchamp was trying to develop as he wrote them down, and either remain incomplete or become too convoluted for us to try to deal with them here. But certain of Duchamp's notions about how the fourth dimension might be intimated are simpler, some even rather homey; for instance:

2 "similar" objects i.e. of different dimensions but one being the replica of the other (like 2 deck chairs, one large and one doll size) could be used to establish a 4-dim'l perspective—not by placing them in relative positions with respect to each other in space3 [Duchamp's way of writing three-dimensional space] but simply by considering the optical illusions produced by the difference in their dimensions.[26]

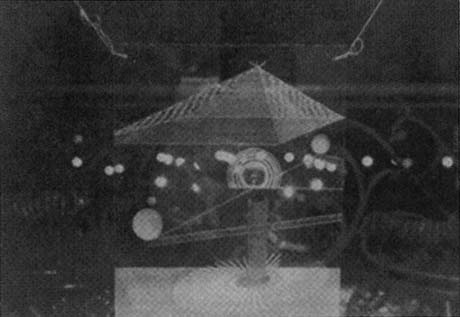

Although Duchamp seems never to have made such a construction, he did make a picture that took up the suggestion in a more abstract, geometrical way. Less than twenty by sixteen inches in size, it was made on glass (mostly during the time he spent in Buenos Aires during 1918) and was called To Be Looked at [from the Other Side of the Glass] with One Eye, Close To, for Almost an Hour (Fig. 31). Here the two spheres joined by a line that makes a tangent to the circle in the middle—actually a magnifying glass—recall the differently sized objects of the note, while the pyramid at the top is constructed so as to create as much uncertainty as possible about where plane surfaces end and volumes begin. One of the oculist charts appears in the lower section, indicating that their role in the Large Glass was to point beyond visibility too. Shown as in the photo reproduced here (the glass has since cracked, so that the work itself no longer gives quite the same effect), the picture seems to provide a passage from the ordinary space where it hangs into a different, more mysterious universe.

The instruction in the title is not just a joke or provocation, but tells the viewer how to induce the sense of disorientation, even dizziness, that seeking to enter the fourth dimension from our more limited world is bound to bring. Duchamp referred to this disorientation when he noted that in a four-dimensional continuum "verticals and horizontals lose their 'fundamental' meaning" (i.e., their ability to orient us in space), just as a two-dimensional being "does not know whether the

Figure 31.

Duchamp, To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close To,

for Almost an Hour (1918)

plane supporting him is horizontal or vertical"; and he tried to evoke the same state in another way when he spoke about losing the possibility of identifying or recognizing "2 similar objects —2 colors, 2 laces, 2 hats, 2 forms whatsoever," through no longer being able to transfer the memory imprint from one to another.[27] For us ordinary folk, trying to think about the fourth dimension makes our heads spin, just what following the instructions for To Be Looked at ... for Almost an Hour would induce. The analogy to erotic experience was made explicit in regard to the "gas spangles" that arose from the malic molds; as they heard the litanies of the chariot, they would experience "dizziness" and "loss of awareness of position," becoming merely a "scattered suspension" or vapor as they moved through the rods and sieves.[28]

Whether Duchamp hoped viewers might experience any similar sensation in looking at the Large Glass is less certain, but there is reason to suspect he did. To elicit such a feeling seems to have been one reason for the carefully developed contrast between the three-dimensionality

of the bachelor space and the insistent flatness of the bride's domain. The bachelor objects are represented in a precise perspective that allows the viewer to think of them as arrayed behind the picture, the chocolate grinder and glider on the floor, and the malic molds, sieves, and oculist witnesses floating in air. We must be standing in front of the glass to see them where they are.[29] But the bridal forms are pure two-dimensional drawings (albeit of objects that have depth and volume), so that we could just as well be seeing them from above. The possibility is implied that we are in two positions at once, standing before the Glass and above it, as if the two halves of the picture were joined by an invisible hinge. Although such a hinge is difficult to imagine in the picture's present state, enclosed in a solid and stable frame, that difficulty arises mostly from the repairs made after the plates broke in 1926; in their original form the two halves were not rigidly held in place. Now, the idea of a hinge was one Duchamp developed extensively in thinking about the fourth dimension, at one point underlining the observation that "A 4-dim'l finite continuum is generated by a finite 3-dim'l continuum rotating (here the word loses its physical meaning —see further on) about a 2-dim'l hinge ." He continued the thought inside the parenthesis by explaining that "rotate" had to lose its physical meaning because the actual rotation of a three-dimensional volume would simply produce another three-dimensional volume. To conceive the fourth dimension required imagining a two-dimensional surface that simultaneously rotated on a hinge and remained immobile.[30] This is exactly what the top half of the Glass would do, were we to find ourselves somehow both before the picture and above it. If we see the Glass as Duchamp imagined we might, we experience our own location as simultaneously in two places at once, as if no longer fixed inside ordinary three-dimensional space; such disorientation draws us toward the fourth dimension.

Duchamp's fourth dimension is a kind of utopia of aesthetic existence, where imagination never has to give way to the conditions and limits of real life. It stands as a conceptual and possibly a visual equivalent for the experience of living perpetually in the realm of aroused desire that Walter Benjamin described as "spared rather than denied fulfillment." In this sense four-dimensionality brings us close to the

declaration Duchamp made—quite without irony—in a later interview, that the value of art lay in its being the only activity which allowed human beings to go "beyond the animal state, because art is an outlet toward regions which are not ruled by time and space."[31] In contrast to the challenges Duchamp would later raise against traditional ideas of art, and particularly against its claim to occupy a sphere independent of ordinary life, the Large Glass strongly links art with transcendence and with freedom from material existence.

One of the ways in which the Large Glass retains these links is through its permanent state of incompleteness. In 1923, after over ten years of planning and often meticulous and laborious work on the project, Duchamp declared the work to be "definitively unfinished." Many reasons contributed to the decision, including the technical difficulties he found in working on glass and the weariness that came from the thing's having dragged on so long, but leaving the work incomplete harmonized so well with his program for it that it is hard not to suspect he had the possibility in his mind from the start. Not finishing the Glass was one more way for it to be a "delay," leaving the expectations it aroused unfulfilled. It remained permanently suspended in time, like its subject, a condition it would have to renounce the moment it descended from potentiality to actualization. Unfinished, it remains always just beyond our grasp; completed, it would be subject to the same disillusionment that Duchamp attributed to possession in his note on shop windows.

That these considerations were in his mind—if not from the start, at least later on—is one of the things suggested by the fact that Duchamp did in a way "finish" the Large Glass—but not within that picture itself. Instead he did another work that showed what the story of the bride and the bachelors would come to if it were removed from the fourth dimension of unfulfilled desire and placed instead within our world of ordinary objects: this was the effect of the construction he produced in secret during the last twenty years of his life, leaving it to confound those who believed he had ceased to work as an artist. Although we will need to skip forward several decades in order to speak about it, looking at Duchamp's last work tells us that its chief purpose was to give greater relief to the subject of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even .

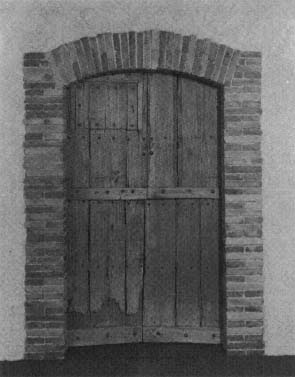

Figure 32.

Duchamp, Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas ,

Exterior View

Duchamp called the thing Given (Étants Donnés ), or more fully Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas (Fig. 32 and Plate 5). He worked on it between 1946 and 1966, storing it in a New York commercial building when it was finished, and leaving behind a box of instructions on how to install it in the Philadelphia Museum, which by then housed the basic collection of his work donated by the Arensbergs and the Large Glass's owner, Katherine Dreier. Given is a construction contained within a space closed off by a heavy wooden door, fixed and unmovable, but pierced by two eye-level holes that allow viewers to gaze into a lit interior. There we see, through a broken brick wall, the sculpted figure of a totally nude woman, her legs open to reveal her sexual parts and the small, dark opening into her body, wholly exposed by the lack of any pubic hair. Her face is obscured behind the wall, but the blond hair of her head covers her neck above the left shoulder. Her right arm is invisible, while the left one holds up a lit gas lamp (seemingly unnecessary, given the blue daylight of the sky). She lies in a field of twigs and brambles with leaves visible among them, while in the

background we see trees, a stream, and in the distance an illuminated waterfall that seems to feed it. The work has been variously read and interpreted, but one of the most genuine and direct reactions was voiced by Duchamp's longtime friend and admirer, the Italian painter Gianfranco Baruchello. Perhaps the right word to convey Baruchello's response is "wounded." Baruchello read Duchamp's career as an inspiration to move constantly beyond the world we know and to imagine alternatives, and he found it incomprehensible that such an artist should have ended by making this heavy, prosaic, altogether realistic and finally depressing thing, the only one of his works that contains direct images of nature and the earth.[32] Baruchello's response captures the mood of Given , and he is right to associate it with "a profound sense of disappointment." But as others have recognized, Duchamp would hardly have devoted so much effort to such a work had he not regarded it as saying something essential about what he had been trying to accomplish in his life. What is its message?

The first thing we see is the door. Duchamp found it in a little village in Spain where he went on vacations, and there exists a photograph of his wife, whom he married in 1954, standing there beside it. Because it was a found object, it has been called a readymade, and perhaps in a way it was. But we shall see that most readymades were manufactured objects, and that Duchamp valued them for not being the direct product of any human hand. The door was certainly handmade by someone, and in contrast to any Duchampian readymade it is old, evocative, seasoned, quaint—all adjectives that associate it with art in an ordinary, banal, even vulgar way. This is the kind of art that closes off possibilities instead of opening them up, and it is just such a closure that the door of Given effects. The door also makes a contrast with another door, one he made years earlier for his Paris apartment. That one swung on its hinges in such a way that when it blocked the entrance to one room it opened up access to another, and many people saw it as a way of defying the commonsense of the French proverb, "a door must be either open or shut" (Fig. 33). No such entry for uncertainty here: the door is definitively, unalterably closed. Placed in proximity to the Large Glass it makes another statement of opposition: for it is opaque where the Glass is transparent, and where it is pierced it imposes a single,

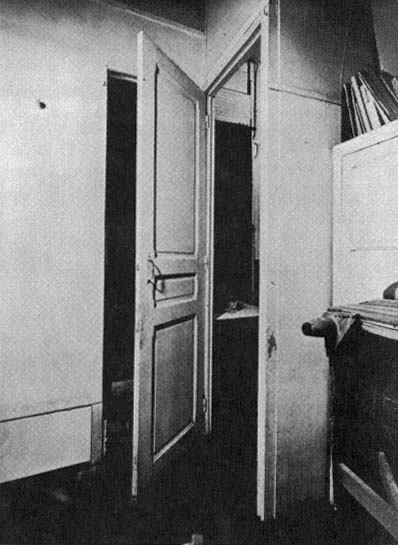

Figure 33.

Duchamp, Door, II rue Larrey (1927)

unalterable perspective for looking at what lies behind it, in contrast to the Glass, which allows us to walk around and see through it from all sides.[33]

Whereas everything in the Glass is open, here everything is closed off and shut up. The work has no more access to unrealized possibilities than the dead artist who left it for us, a point Duchamp explicitly

underlined by assuring that no one would know about his last work until he had departed from life. Yes, he is saying to us, I can make you a finished version of the Large Glass—but I will have to be dead to do it. When the breath of desire no longer lifts me into the world of unrealized aspirations, then the elements of my picture will return to the dead world of time and space, where we can examine them as they would be in a state that belongs wholly to the here and now.

And that is where we find them, beginning with the ones named in the title. The waterfall and illuminating gas that remained wholly imaginary in the Large Glass are here given direct physical form, the gas as a lamp well-known in France before World War I (Duchamp himself had done a sketch of one then) but which had entered into the realm of romantic nostalgia by the 1960s, the water become wholly familiar as a tackily lit bit of scenery (brighter on the spot than in the reproductions), in fact one that Duchamp himself had photographed—in Switzerland, no less.[34] Both have migrated from the realm of fantasy into the world of tourism and artsiness where Duchamp found the wooden door.

Everything in Given belongs to the world of données , of things already determined, data. The landscape depicted here may be in some way the one Duchamp spoke about in the notes for the Glass, and which was to be located inside the glider, in the region of the water-wheel. There, however, it remained a mental image arising within the bachelors' erotic fantasy, which was in turn part of the bride's imagination, "an inventory of the elements of ... the sexual life imagined by her the bride-desiring." Here nothing is left to desire or to imagine, not the landscape and above all not the sexuality of the woman, whose lack of pubic hair creates as explicitly physical and—my own view, but one that many viewers share—brutal a representation of sexuality as possible. The Large Glass's suspension of femininity in a space beyond experience has given way to a body whose heavy three-dimensionality is the counterpart of the unrelievedly material kind of sexuality it proclaims. Even the viewer has here become materialized, identified as a voyeur —Duchamp used the word in his notes—by the necessity of gazing through the eyeholes at the nude figure in the public space of the museum; the contrast with the spectator of the Glass, drawn toward

Figure 34.

Gustave Courbet, L'Origine du monde (1866)

the mysterious space of the fourth dimension by the "hinge" construction that makes the top panel simultaneously a vertical and a horizontal plane, is complete.

To deplore all this—as Baruchello did—because it weakens Duchamp's vocation of questioning the limits of reality is to miss the point, however, for Given is precisely an account of what art becomes when erotic energies, preserved as engines of fantasy within the delay of the Large Glass, turn from imagination to ordinary life. Duchamp made clear how negatively he regarded such images by linking the nude figure in Given to an artist whose role in the history of painting he often deplored, Gustave Courbet. It was with Courbet, the apostle of realism, that Duchamp located the triumph of what he called retinal art, the art dedicated to the exploration of immediate, visual experience. Given is an illustration of just what retinal art is, and the reference to Courbet is explicit. The prone figure recalls some of Courbet's aggressively realistic nudes (see Fig. 34), and lest we miss the point, Duchamp did a series of etchings of nudes in the mid-1960s (when no one

Figure 35.

Duchamp, Selected Details after Courbet (1968)

could yet be aware of their reference to Given ), their sexual parts prominently exposed. One was called Selected Details after Courbet, another Le Bec Auer, for the kind of gas lamp that appears in the left hand of its female subject, just as it does in Given (Figs. 35, 36). Here we see the woman and a presumed partner relaxing as in the aftermath of a sexual encounter, the moment which can never occur in The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even . Everything adds up to let us know

Figure 36.

Duchamp, Le Bec Auer (1968)

that the work Duchamp produced over twenty years but kept hidden while he lived is his account of just what he thought art should not be; it is the world of the Large Glass destroyed by being finished off, the ending he refused to provide all through his life, the work that could come from his hand only once he was dead.

I think this is the point of view from which to consider one aspect of Given not mentioned so far, the seemingly aggressive and hostile treatment to which the female figure has been subjected. Duchamp's relations with women could be complex and mysterious enough (as we shall see later on) that elements of suppressed anger and frustration may be at play behind this maimed and defenseless image. One might even

imagine that he here took his revenge on the bride for the torture she committed on him in his dream of 1912. But if there was misogynistic aggression in Given, it was simultaneously something else. What has been mistreated here is the aspiration to live "beyond time and space" that was Duchamp's own in the Large Glass; the violence done here is done against Duchamp himself in female form, not by him against femininity. By the time he began work on Given he had made public display of a female side to his own personality in his alter ego Rrose Sélavy; his way of being male did not require denying the feminine in himself. Whatever hostility to femininity Given may contain resides within Duchamp's larger theme: desire's ability to lift human beings, male or female, into the realm of imagination turns to disillusionment once they settle for mere physical possession.

To let people know that Given was a comment on the Large Glass, that it was a typically enigmatic and Duchampian way of telling, through a veil of irony, what his earlier work was about, Duchamp did not stop at arranging for its installation near the Glass in the Philadelphia Museum. He also published, in 1966, the year he finished work on Given (he was two years away from death), the third and last collection of his notes, the so-called White Box (also known as Á l'infinitif ). In it he included both the note on shop windows and the speculations about four-dimensionality, materials without which the reading of the Glass developed here would lack essential elements and clues. These notes make the White Box a kind of Duchampian How I Wrote Some of My Books , a revelation at once theoretical and personal. One reason why so many interpretations remain so distant from what we can now know to have been in his mind is that no attempt to understand his work before 1966 could make use of them. Similar difficulties have hindered the understanding of Duchamp's other famous activities, his readymades and the series of objects associated with them. We must now see how the reading of the Large Glass proposed here helps to put them, too, in a different light.