Preferred Citation: Brentano, Robert. A New World in a Small Place: Church and Religion in the Diocese of Rieti, 1188-1378. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9h4nb667/

| A New World in a Small PlaceChurch and Religion in the Diocese of Rieti, 1188–1378Robert BrentanoUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1994 The Regents of the University of California |

For Carroll

Preferred Citation: Brentano, Robert. A New World in a Small Place: Church and Religion in the Diocese of Rieti, 1188-1378. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9h4nb667/

For Carroll

Acknowledgments

The name of my friend Alberto Sestili should appear first in any list of people whom I thank for their help to me in my study of the diocese of Rieti. He has been in various ways my guide and host for many years; it was for example through him that I met the nuns of Santa Filippa Mareri, through him that I found the cavèdano . He made me feel at home in the Cicolano. He cannot be separated in my mind from three generations of the Colangeli family who were also hosts to me and my family at Rieti's Quattro Stagioni at the site of Giovanni Petrignani's San Giovanni Evangelista. To the convent of Santa Filippa itself I was first introduced, after being introduced to her by Alberto Sestili, by Suor Clotilda, my oldest friend in the convent; through her I met the archivist, Suor Gemma, and the abbess mother Margherita Pascalizi. They and the other nuns of their convent adopted me, fed me, chauffeured me about, talked to me and showed me their documents, and even let me talk about their saint at her shrine. I cannot ever thank them enough, but I hope that their redwood will grow very large as a sign of my thanks.

To Don Emidio De Sanctis who was canon archivist of the Archivio Capitolare when I first went to Rieti to check a document in the San Salvatore Maggiore dispute, to his memory, I owe very special thanks. Into the often closed archives he welcomed me, for many days in many years. When I came to Rieti with one or more of my children when they were small, Don Emidio welcomed them too and let them play in the archive room and draw at the table at which I worked, draw the views

(now unfortunately much less beautiful) that they saw from the tower windows. To Don Emidio's brother Don Lino, who was, until he died, priest at San Francesco, I am also grateful. The actual doorkeeper of Don Emidio's archives was the cathedral sacristan, my friend Franco Strivati, who became my protector and, for example, continually worried that I would be locked all night in the archive tower above the sacristy after the finish of evening service. These are, or were, old friends from my earliest days at Rieti. To theirs many other names should be joined; one which must appear is that of Cesare Verani, a wise and learned local art historian, who particularly connects my first with my last days of Rieti work, and thus with the new world of serious young Reatine research historians. Among them Vincenzo Di Flavio first helped me with information and advice and early modern material from the episcopal archives, material of the sort increasingly visible in his own published work. To his name should be joined that of Andrea Di Nicola; the quality of the research of the two men is suggested by their joint publication, the excellent Il Monastero di S. Lucia . I should also thank Henny Romanin for his kindness, and very specially Roberto and Claudia Marinelli, for their help both in Rieti and Borgo San Pietro, and for the particular delight of Roberto's mind and eye as they appear in his various kinds of history, for example in his Il Terminillo, Storia di una montagna . Roberto and his colleagues in Rieti's Archivio di stato have given the face of Reatine local history a new expression. Roberto Messina has helped me in the Rieti Biblioteca Comunale. Don Giovanni Maceroni and Suor Anna Maria Tassi, now keepers of the capitular as well as the episcopal archives at Rieti, have shown me many kindnesses.

I should like to thank Rita Di Vito and the families of the Case Galloni, and Barbara Bini, who not only carted me around the countryside as she took handsome photographs for me but also lent us her house between Contigliano and San Pastore, with its views across the conca to Tcrminillo, during one perfect Eastertide. The sindaco, Augusto Mari, took me on a tour of the mountain communities and uplands above Petrella Salto. The learned local historian Evandro Ricci advised me about Secinaro history and took beautiful photographs of the town for me. Don Antonino Chiaverini sat me down in his parlor in Sulmona and brought me the cathedral's records of the visitation of 1356 and of the canonization of Peter of Morrone. In Penne, the archivist of the cathedral archives of Penne-Pescara, Don Giuseppe Di Bartolomeo, heroically arranged for me to use those archives, from his hospital bed, immediately after a serious motorcycle accident incurred

during that priest's vigorous pursuit of the pastoral care of his widespread flock. The Marchesa Luigina Canali de Rossi, who made Rieti more resonant during my whole time there, talked to me about the Rieti that existed before it had had implanted on it its current road system and its post-World War I values. I should thank Canon Pietro Bedeschi for his help at Ìmola and Don Giorgio Fedalto for his help with Olema, Dottoressa Anna Maria Lombardo for her guidance among the notarial archives in the Archivio di stato at Rome and Richard Mather for showing me the archives of Vèroli.

Daniel Waley sent me encouragement and a valuable document from Siena. Arnold and Doris Esch made me sharpen my interest in the diocesan landscape. Charles McClendon took me back to Farfa. The art historians Gary Radke, Julian Gardner, and Luisa Mortari made me look better at the artistic relics of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries at Rieti. Anthony Luttrell helped me in many ways and particularly in his insistence upon the importance of the Paris Rieti manuscript. Here I continue to be indebted, as I was in earlier work, to those major historians of Italy, my friends Charles Till Davis, Gene Brucker, Lester Little, Peter Herde, Edith Pasztor, Eve Borsook, Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, Stephan Kuttner, and Fra Leonard Boyle. But in this book I am also indebted to newer friends, mostly of Padua, whose example has much affected me and should have made me a much better historian than I am, first of all, Paolo Sambin, and men and women like Giorgio Cracco, Antonio Rigon, Fernanda Sorelli, Sante Bortolami, and, perhaps honorary Padovani, Giovanna Casagrande, and Mario Sensi. I very much wish that this long, long-awaited, and eccentric book could be a more decent reward for their efforts.

I want to thank Kaspar Elm for having lighted up Franciscan studies for us all, even when he is not being used directly, and David Burr for "showing" Franciscanism. And I particularly want to thank the young English evangelical Protestant missionary whom I met one dark Rieti afternoon as I waited for the archives to open and who told me of bringing Christ, now, to the thirsty hill villages.

I must thank William Bowsky, Duane Osheim, Randolph and Frances Starn, and Margaret Brentano for their very careful and generous reading of the long text, and for their many suggestions. I wish that I could have used their suggestions better. I also want to thank Gerry Caspary, Irv and Betsey Scheiner, Beth Berry, James Clark, Miriam Brokaw, Joanna Hitchcock, Jane Taylorson, Tony Hicks, and very specially Edith Gladstone, for their advice and help. Many of my col-

leagues in history at Berkeley have, with their warmth and tolerance, made it possible for me as for others to be, each of us, our own kind of historian (and use our own kind of grammar). Arnold Leiman has made me much more sophisticated in my thought about memory, and Steve Justice has in my thought about narrative, although neither may be overwhelmed by the level of sophistication I have actually achieved.

I thank the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the American Council of Learned Societies for the support they have given me, and for their patience.

This book is very much a family book. My children have grown up (and, two) of them, become parents themselves) living with it. But it has been an extended family, including particularly the Toesca-Bertelli and the Weyer Davis—the wise and richly subtle parents have advised me, and the children have joined mine: Frank and Bernie, early experts on Saint Francis and Saint Anthony, as well as bats; Pierino, on the central Italian countryside and its artifacts, as well as trains. All of them became Reatines. My children, James, Margaret, and Robert, have made everything in life to which they were or are attached a joy—and that includes Rieti.

Note

In the period of this book the year in Rieti began on Christmas day, so that for example a date recorded as 27 December 1298 would be, according to modern reckoning, 27 December 1297. (Modern reckoning is used in this book.) By the late fourteenth century the church of Rieti's fiscal year began on 1 July, and elections of officers were set, at least in some recorded cases, for 15 June, Saint Vitus's day. The calendar of the church of Rieti was dominated by feasts of Christ-God and the Virgin, but the local importance of Saint Barbara (supposedly of Scandriglia) was again apparent by the later fourteenth century.

The unit of land measurement normal in preserved Rieti documents was the Reatine giunta ; the modern Reatine giunta is 1,617.32 square meters, and the modern coppa of the area of Poggio Moiano is about 2,000 square meters. Although careful measuring of land areas is apparent in the area of Rieti by the mid-thirteenth century, there is no necessity or reason to believe that the giunta in the period of this book had a fixed measure; still, it was a recognizable description of surface area, and for arable flatland it was probably thought of as a space which would now be between 1,500 and 2,000 square meters.

The surface of the diocese has been changed by the adjustment of its river systems and the creation of lakes, like the Salto, as well as by the drying of the land in the conca . The area is subject to earthquakes; the highest part of the mountainous areas which surround the conca of Rieti is Terminillo, which at its highest peak is 2,213 meters above sea level.

A clause in the first Reatine statutes says that in Rieti and its district all kinds of money were current—current omnia genera monetarum —and in fact diversity of currencies (at least in describing value and price) is apparent from the beginning to the end of the period of the book: in an early text denari provisini (of Rome) and denari papienses (of Pavia) appear together (and see Spufford, Handbook of Medieval Exchange , 67, 104). But there were usual currencies: in 1337 soldi provisini are referred to as olim usualis monete , once usual, in a text that needs the explanation of memory, and by the turn of the century, around the year 1300, the money of Ravenna, ravennantes (plural), had become the usual money, and it had then a varying rate of about 35 of its soldi to a form (Spufford, Handbook, 72), at a time when the provisini were moving uneasily between 30 and 34 soldi to the florin (Spufford, Handbook, 67–68). (All visible lira currencies followed the convention of 12 denari to the soldo and 20 soldi to the lira.)

The florin itself was very much present in Rieti, as this book should make clear, particularly in its discussion of wills. Complexity at Rieti was increased by the proximity of the kingdom of Naples with its augustali, tareni (tari), uncie, and carlini . Just after 1300 the uncia (at Naples) was worth slightly less than 5 florins and the augustale slightly more than a florin; the florin was worth slightly over 6 tareni, and was worth 13 carlini (Spufford, Handbook, 59, 62–63).

From the 1350s on, the chapter account books give exact prices for a number of commodities, articles, and kinds of labor which were bought or sold by the chapter. It is thus possible to examine fluctuations within years, over time, and in various locations and climates, of grains—wheat, spelt, barley, rye—and sometimes legumes—fave, ceci —as well as oil, wine, and must. From the end of the thirteenth century and the beginning of the fourteenth, wills give real or estimated prices and values for specific items. It is difficult to establish equivalence from these values, but a list of some of them may help anyone reading this book: in 1363, 8 quarters of wheat brought 4 lire, and one quarter 20 soldi, and 4 quarters of spelt brought 14 soldi 7 denari; in the same year the painter Jani got 8 soldi 6 denari for a pictura of the king, and Cola Andrea got 1 florin for the pictura of Saint John and Saint Mary by the crucifix, a dove and a cock (palomba,gallo ) costs soldi 3 denari, and a key for the campanile cost 7 soldi; in 1364 the supplies and work for a door for the campanile next to the bell cost 18 soldi; in 1358 the pay for the singers at the feast of the Purification was 2 soldi 10 denari, and the pay for Antonio who carried the cross for the Rogation procession was 3 soldi.

In 1318 and 1319, 10 giunte of arable and 3 giunte of vineyard or 100 florins seemed an appropriate endowment for a private chapel. In 1301 silver chalices were valued at 15 florins, and through the first half of the fourteenth century tunics as gifts for the poor or worthy ran from 20 soldi down to 10 soldi or less. In 1297 a breviary or missal could be valued at 26 florins, and in 1348 a country pig was worth a florin.

Previously published lists of Reatine bishops have been inexact. I hope that the revised list published here will be helpful to the reader. Previous maps of the thirteenth-century diocese of Rieti have, I think, been unjustified in their exactness. I hope that the map published here will at least warn the reader of that.

I have, here, used the title dompno as a quasi translation of dompnus and most frequently for ordained priests whose offices were not sufficiently high to demand a dominus , so, generally, for example, for prebendaries but not canons. I have quasi-translated the word castrum , when it refers to a town or community, as castro , in part because I think the evidently alluring, generally accepted concept of incastellamento is misleading.

I have kept Latin and Italian in the text, when I have kept it, because I wanted to retain sound or tone, or because I wanted the reader to see the word which I had seen, because I wanted that precision for him or her or because I wanted him or her to translate the word or phrase for him or herself in terms of its specific usage. I have tried to make all retained Latin or Italian clear in paraphrase or explanation.

I have repeatedly retained varying spellings, because I wanted readers to see that variation as part of the reality I was trying to recover and as something important to the way these Reatines thought and read and heard. I wanted the reader to know, also, that I did not really know whether Reatines heard Mertones or Mercones , for example.

Finally I must warn the reader that a book about this material, done from these sources, under the archival circumstances that prevailed, by me, virtually must contain errors; the seeming precision of my approach should not hide that. And I must say that a foreigner doing local history, which is headbreakingly broadly demanding in any case, is foolhardy—I would suspect that no non-Ohio Valleyan could ever capture the sound, smell, shade, taste of the Ohio Valley—but an American medievalist, who believes that real history is local history, is caught.

Revised List of the Bishops of Rieti, 1188–1378

Note: The works cited in brackets refer to nonexistent bishops of Rieti.

Adenolfo de Lavareta "electus" March 1188 (predecessor Benedetto, still active 1185), still "electus" 9 November 1194; "episcopus" 4 February 1195, still "episcopus" September 1212; retired to Tre Fontane

Gentile de Pretorio (canon of Capua) unconsecrated elect, active 3 March 1214

Rainaldo de Labro active 26 May 1215–25 July 1233, almost surely alive on 21 February 1234, dead by 25 January 1236

[Odo: Ughelli, Eubel]

[Rainerio: Ughelli, Michaeli, Register of Gregory IX (edited), Eubel]

Giovanni de Nempha active 8 August 1236–2 September 1240

Rainaldo Bennecelli active 9 May 1244–11 March 1246

Rainaldo da Arezzo, OFM active 17 April 1249–9 March 1250, resigned before 3 February 1252

Tommaso (corrector) 3 February 1252 – active 23 July 1262, pope writes to a bishop 23 May 1263, dead before 23 August 1265

Gottifredo (bishop of Tivoli) 23 August 1265–active 1275/6, dead before 10 January 1276

[Disputed election, 1276–1278; Capitular candidates: Giacomo Sarraceno (canon of Rieti); Benvenuto, OFM]

Pietro da Ferentino (Romano, Egiptius, bishop of Sora) 2 August 1278–22 July 1286, translated to Monreale

Andrea (Rainaldi, or Rainerii, bishop of Sora) 27 July 1286–active 1292

Nicola, O. Cist. active 26 November 1294–resigned after 24 December 1295

Berardo (bishop of Ancona) 4 February 1296–active 24 May 1298, dead before 26 August 1299

Jacopo Pagani (canon of Toul) 26 August 1299–active 4 April 1302, relieved for cause before 8 June 1302

Angelo da Rieti, OFM (bishop of Nepi) 8 June 1302–thought to be alive 14 June 1302, dead before 3 August 1302

Giovanni Papazurri (bishop of Imola) 3 August 1302–alive 26 June 1335, dead by 12 June 1336

[Raimondo: Ughelli, Michaeli]

[Giovanni: Ughelli, Michaeli]

Tommaso Secinari (canon of Rieti) elected before 3 August 1338, confirmed 7 December 1339, died 5 September 1341

[Nicola Rainoni (canon of Lateran), elected 30 September 1341, not confirmed]

Raimond de Chameyrac (canon of Amiens) 5 August 1342–active 17 December 1345, translated to Orvieto by 1 July 1346

Biagio da Leonessa, OFM (bishop of Vicenza) 24 October 1347–died 30 April 1378

Introduction

Ignazio Silone's Pane e vino begins with the picture of old Don Benedetto as he sits, with his sister behind him, on the low wall of his garden, in the shade of a cypress, with the black of his habit absorbed and enlarged by the shade, as the two, brother and sister, look and listen and wait for the small world of young men whom Don Benedetto has touched to return to him.[1] It must be difficult for anyone writing about central Italy not to try to kidnap Silone's Abruzzese place, topography and people, his mixture of sacred and secular, and to enrich with it his, the writer's, own work. Here there is an excuse.

This is a book about the diocese of Rieti (see maps 1 and 2), where the provinces and ideas and speech of Umbria, Lazio, and Silone's Abruzzi join one another, and where the papal states and the Neapolitan Regno—and their currencies—once met (and, when they were joined, resisted the joining with a blur of brigandage).[2] The book deals with the period between 1188 and 1378, from the first known notice of one bishop-elect, Adenolfo, to the death of another bishop, Biagio. It is a book about religion in society, about that aspect of society (of the lives of men living in groups) which finds its focus in religion and the church, or perhaps more exactly about society as it can be seen in the shapes of church and religion, as they look out and observe what of it they need or can use. In this sense the book imitates the collecting gesture of Don Benedetto. And if it seemed necessary to choose one part of the Reatine church more physically to represent the old priest, it would be the chapter of the cathedral church of Rieti, the canons of the church of Santa

1.

Central Italy.

2.

The thirteenth-century diocese of Rieti.

Maria, on the hill which dominates the city of Rieti at the diocese's center.

It is important for the purposes of this book to make clear that church and society are here not treated as, or believed to be, two different or separate entities, even ones seen as intricately interlocked. A more Scotist imagination is required. But, insofar as a formal separation is imaginable, the material here will show, abundantly and unsurprisingly, that ecclesiastical and secular, spiritual and material, body and soul, are very fully absorbed in each other. The most audibly spiritual bishop of Rieti from the period of this book, the Franciscan Rainaldo da Arezzo (who was active at Rieti in 1249 and 1250 and who had resigned the see before 3 February 1252), has left, or there have been left about him, the archival records of only two events during his short episcopate. One of these two is the bishop's dispute with the podestà of Rieti over who got the horse on which the podestà, or his servant, had led the bishop (echoing in the little distance emperor and pope) as he first came as bishop from the gate of the city to the church of Santa Maria.[3] Rainaldo did not long suffer a prelacy with this interpretation; but by the time of his resignation he had been forced to realize that being bishop of Rieti in 1249 involved riding on and litigating about a horse. Rainaldo and the horse show the uniting of spiritual and corporal at a high level, in high relief; but more regularly and more significantly the border between the two quietly shades into nonexistence, into the complexity of life lived by physical beings susceptible to spiritual aspirations and to the different complexity of spiritual acts performed with physical furniture: year after year during the last three decades of this book's time, the chapter's chamberlain, the (by then) canon Ballovino, made record in his accounts of the feast of the Assumption in August, but the memory recorded is the cost of the laurel bought for the feast, and of twine to bind the laurel into a form—in August 1364, for example, 10 soldi and 3 soldi 6 denari, respectively.[4]

Although this book is about a society as it is formed into a church, society is here interpreted as much as possible as a collection of, admittedly limitedly visible, individual men and women, at least in the first instance. Those moments when individual thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Reatines turn their minds' eyes toward the central religious problems of their lives, as when dying they make their wills, are particularly sought here. Many years ago my friend the historian Caecilia Weyer Davis asked me what I wanted to find out in doing the work for this book. Without thinking, I answered, "the color of men's souls." I

may have succeeded in no cases, and in fact the phrase may be clear to no one else, but when I try to scratch at the evidence to see what is in the memory or mind of a farmer from the Cicolano come to give evidence before representatives of an ecclesiastical court, that is what I would most like to see.

Professor Weyer Davis's question was particularly pertinent because of the way the work for this book has proceeded. It began when I first came to Rieti in the 1960s to check the transcription of an edited document that I wanted to use for another book. I was immediately fascinated by the essentially unused thirteenth-century material of the Archivio Capitolare, then stored in a tower above the sacristy of the cathedral, into which the keeper of the archives, the canon Don Emidio De Sanctis, kindly admitted me. At first the city and diocese did not seem to me very striking; but their mild, persuasive attractiveness gained over the years such possession of me that I have found it hard to finish with them and go on to other work. From the beginning, and more so in the beginning, they suggested a place of which the history, or at least the ecclesiastical and religious history for a century or so, might be controlled by one person, who could observe all the surviving documents and monuments and topography.

That is what I wanted to do: to observe everything, and to decide after observation what questions could be, by me, most revealingly asked. I wanted the material to form the questions. I wanted to approach the existing remains like the kind of extreme physical archaeologist who would come to a site with no questions, which he could recognize as questions, formed in his mind. I realized, but of course insufficiently, the difficulties of the approach, but I had not realized that the questions formed by this kind of observation, questions to be used in going back through the material, might seem on their surface so disturbingly bland and obvious. In fact, that which I found most compelling was change over time, which would surely seem the most basic and obvious thing that every historian observes; although I generally have been more caught by the fascination of the other twin of the historian's constant pair, continuity. But this has come to be a book about how the church and religion changed over a period of almost two centuries in a specific place. That I have called an area as large as the diocese of Rieti "a small place" may seem odd; but there were not many people scattered over its difficult topography, and in spite of the repeated presence of the papal court in the city of Rieti, and even of Francis of Assisi, who was visibly present there, it was not in any normal sense, and cer-

tainly not more than episodically, an "important" place, or a rich one.

I have most frequently worked on the thirteenth century, and I had intended to study Rieti from the beginning of the papacy of Innocent III, in 1198, to the end of that of Boniface VIII, in 1303. The irresistibility of the fourteenth-century documents in the chapter archives changed my mind; and the interest, for me, of the men, three of them, who were the chapter's most important keepers of records between the 1260s and the 1370s, drew me into, and almost through, the fourteenth century—without, of course, endowing me with the knowledge and talents natural to real fourteenth-century historians.

Ballovino's account books in particular were the documents that drew me (with Bishop Biagio da Leonessa) across the Black Death and the changes it produced, or signaled, toward the end of the fourteenth century, as Matteo Barnabei's notarial cartulary, filled with a miscellany of church business, had drawn me into the fourteenth century. But the classes of individual documents which first drew me to Rieti—records of witnesses' testimony in litigations—and which have most held me there—wills and testaments—still seem to me most sharply, and at the same time resonantly, but not easily, revealing of what church and religion, and a lot else besides, meant there. They talk (in the heavily intrusive presence of the letter u ) of envisaged space and remembered sensation. They give things names. And they give people names. And sometimes the names themselves are surprising in the memories they suggest, like the name of the rustic farmer Roland, who testified in a dispute over San Leopardo in Borgocollefegato in the Cicolano around the year 1210.[5]

The San Leopardo case, from almost the beginning of this book's period, is particularly pungent, with its remembered keys and bells, lunches and dinners, stories told and places stood, selected sacraments and clerical actions, and the relationships in which people were held and which other people remembered—Berardo, a knight, a blood relative of Bishop Dodone, remembering his own youth; Gisone, a member of the familia of the church of San Leopardo. Testimony in this case early indicates kinds of groupings that existed in society, that existed in people's memories, but also the kind of cross-hatching of the same individuals caught in various guises within different groups, which was characteristic of the recorded, remembered church in the diocese, this church with its intricate pluralism of benefices.

The talk, the conversation, within records of litigation and wills, however, is not free and open, not without rules and forms. The speech

in these documents, and others, is shaped by questions asked, answers recorded, laws written, and presumably conventions understood. Aron Gurevich, with his translators (in his essay "The 'Divine Comedy' before Dante" from Medieval Popular Culture ), talking of more clearly literary sources, has given us the helpful phrases of a formula: "A medieval author broke up a psychic experience, his own or someone else's, into semantic units meaningful for him, in accordance with an a priori scheme appropriate to the genre."[6] Both the record of witnesses' testimony and clauses recording bequests in wills break up the experience of memory, and also of expectation, and the sensation of piety, into semantic units with a priori schemes appropriate to their genres. They are elaborately shaped by forms. But, in spite of this, and in fact partly because of it, they break open the past and let its internal treasure spill out before the observer's eyes.

The language implied by the nature of the information found in wills and litigation documents is connected with the more generally accepted structure of language, of communication, for many kinds of (at least nonacademic) statement for essentially the entire period of this book, in central Italy (and many elsewheres).[7] Within the cage of formality, reality is described in the witness's or testator's memory's narrative and in the testator's more limited narrative of action predicted after his death. The Scripta Leonis , the collection of stories about Francis meant to show what he was like, recorded in the 1240s from the memories of his old companions at the hermitage of Greccio, within the diocese and a few miles from Rieti, offers a model of reality. Truth is description. Description is stories. Truth is stories. And it begins with et :

Et sedens cum illo fratre iuxta uitem cepit de uuis comedere ut non uerecundaretur solus comedere; et manducantibus illis laudauit Dominum Deum frater ille . . .

[And] Sitting with the friar by the vine, he began to eat grapes so that he should not be embarrassed at eating alone. As they ate the grapes, the friar praised God . . .[8]

Francis is the sitting, the eating, the inducing without embarrassment, the praising, the vernacular caught within the transparent skein of the Latin. In the contemporary sources used in this book one hears in smaller fragment the syntax shaped by the generally unstated assumption that this is a likely way to think or talk if you want to arrive at truth or knowledge (although this smaller fragment of syntax is not infrequently caught between the heavy binding, stated or presumed, of pro-

tocol and eschatocol, flourished invocation and validating seal). This antique assumption is also in large part the assumption of this book—the truth about the Reatine church, its description with any kind of exactness, could come only from a recapturing of its exact narrative syntax and a maintaining of the exact patterning of its images. (Thus there may seem a kind of irony in my citing Gurevich's stimulating book, so wrongly, I think, dedicated to the general and the collective.)

Even the soundest-seeming generalizations about change (for example: by the middle of the thirteenth century what had once been experimental religious experience was more and more channeled into institutions by then formed) are not crisply descriptive in a way that the specific statement of expenses from the Chapter Account Book written by a new chamberlain in the year after this book closes, for 1379–80, are.[9] They seem to sum up the church of this book, what it has become:

Item pro palmis xx s

Item dedi dominus Agabitus de Columpna de pecunia Camere flor xxvii s xiii d vi

Item pro una Crux pro altari magno xii s

Item dedi Lucia pro aqua pro mensibus Octubris Nouembris Dicembris viiii s

Item pro una Ocha pro Sancta Barbara v s

But even these items are chosen selectively, climbing up folio 62r of Don Agostino's account: the palms, the big money (in florins) for a Colonna (in his maintained nominative), the cross (also nominative) for the high altar, the money for Lucia (also undeclined) for water, the goose for Saint Barbara's day.

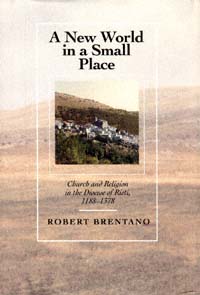

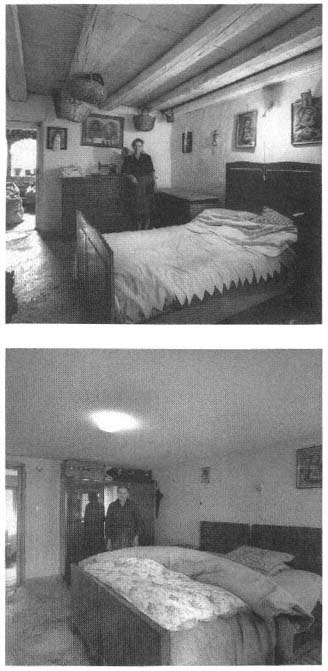

Seeing everything unadjusted, all together, the impossible, would be most desirable, so that one could find what Paolo Costantini, in the catalog for L'insistenza dello sguardo , has suggested photography can do: "La fotografia ha il potere di suggerire altre indicibili realtà celate sotto una minuziosa descrizione superficiale."[10] The depth of reality and interrelationship is strongly suggested by a meticulous description of surface, including light seen on the surface within the photograph, as again and again the photographs of L'insistenza dello sguardo demonstrate. The "minuziosa descrizione superficiale" is also, though, a potential tool for the description of change. In fact the most effective model for me for understanding change, in classes, in thinking about this book, has been a pair of photographs, taken fifteen years apart by

Italo Zannier, one of the composers of L'insistenza dello sguardo . He presents to his viewer the same woman, in the same pose, in the same room, in the same Friuli village house, in Claut, younger and older, in the presence of changed and rearranged furniture (plate I).

To the Scotist one would like to add an Occamist imagination, reticent about anything but the particular. And reading the account books year after year, one can get the impression that one has done this. Sometimes, moreover, like the headlights in a photograph, individual entries suggest, in their emphasis, movement within the books' own flat surfaces. This happens on folio 6IV of Don Agostino's 1379 account, a book that in general has few days and no hours:

Item: on the 17th day of the month of September, Saturday, at noon was broken the naticchiam [metal guard bar] of the mill of Santa Lucia; and the same day it was repaired.[11]

However, my attempt to capture the sort of change that occurs in the room at Claut is of quite a different kind, and is in, or is meant to be in, the tradition of Frederic William Maitland. The "rooms" to which this book will most carefully attend are words, big central defining words, like bishop, diocese, boundary, testament, and even bigger ones like death and by inference at least the biggest of all, Christ and God . The book will try to watch and show the changes that occur within the walls of these words.

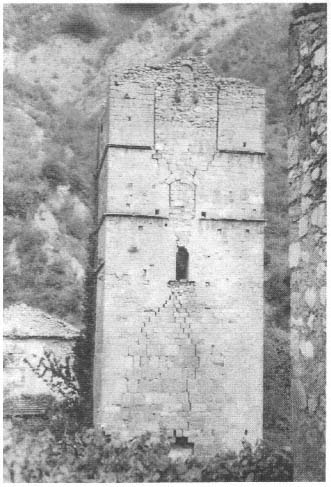

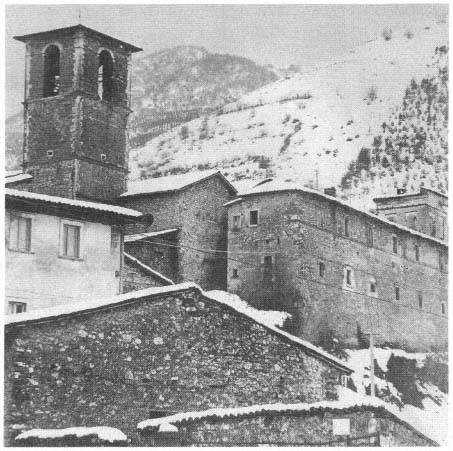

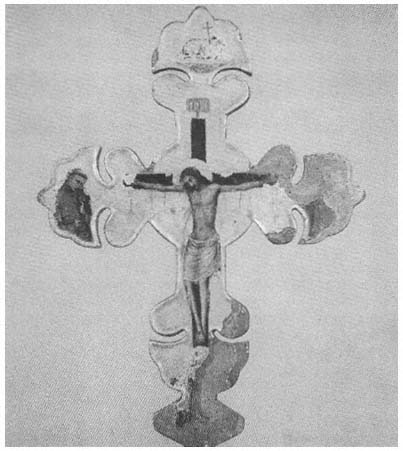

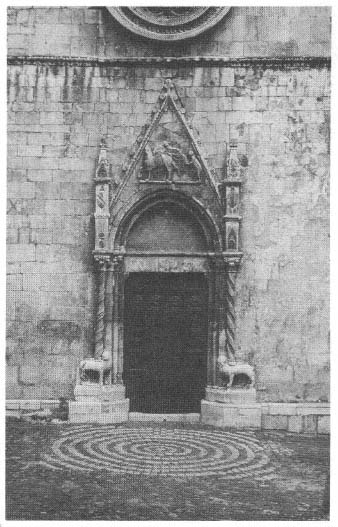

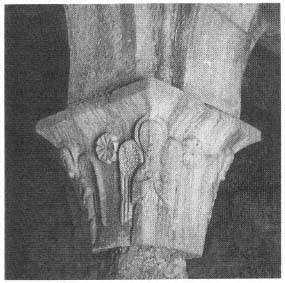

Fortunately for the sake of this image, or for movement within it, walls change too. Within the period in which the definition of bishop/episcopus/vescovo is swelling, significant churches become large. Two major monuments from the diocese of the period of this book are the small, relic-holding country church of Santa Vittoria in Monteleone Sabina (plates 2 and 3) and the great preaching church of Sant'Agostino in Rieti (plates 4 and 5). The full length of the boxlike structures assembled into Santa Vittoria is less than 30 meters; the open length of Sant'Agostino without its apse chapels is over 50 meters. The breadth of Santa Vittoria's facade is about 9 meters and Sant'Agostino's about 16; the main entry door of Santa Vittoria is 155 centimeters wide, Sant'Agostino's 275 centimeters. Santa Vittoria and Sant'Agostino represent different periods, different uses, and different notions about church—it is not just as C. N. Brooke once wrote, rather lightly, that "the sentiment for worshipping in tiny boxes as well as in enormous cathedrals can be paralleled everywhere." And the clearest change in the definition of the biggest words may in fact be pictorial or plastic, as in the quite startling differences between two

public Christs, now both preserved in the Museo del Duomo at Rieti, the earlier a thirteenth-century fresco from an external wall of a church in Canetra (plate 6), the other a fourteenth-century piece of sculpture in wood, polychrome, until quite recently used for processions in the village of Sambuco (plate 7).[12]

A New World in a Small Place is divided into eight chapters. Chapter I is meant to be an introduction to the syntax, the vocabulary, the terms of the problems of the book: what is the church, and the religion, that is being considered here? what is change? what is the place, the diocese of Rieti, in which it is occurring? Chapter 2 is meant to be a lens through which "church" can be seen: two senses of church defined by the roughly contemporary actions, words, and memories (or reconstructions of memory) of two sets of actors on roughly adjacent, and sometimes identical, physical parts of the diocese. These chapters are meant to supplement each other and introduce the rest. Chapters 3 and 4 try in a number of very different ways to define "diocese" and "diocesan boundary"; they mean to describe change. The governmental and record-keeping change described in these chapters is probably the most obvious event of this book's narrative. Insofar as a world can be expressed by governmental self-consciousness, the Reatine diocesan world of the mid-fourteenth century is new and clearly different from that of the early thirteenth century. Its newness, moreover, is connected with newness in many other places. I have tried, however, in chapters 3 and 4, the concluding and beginning dates of which do not quite meet, to show, in dividing, a change in the nature of change, in its pace and material, and in the sources which reveal it. (And certainly a reader might have thought 1254, the date of Bishop Tommaso's verbal map, a more appropriate first ending than 1266, a point in the continuing removal of Amiterno to L'Aquila.)

Chapter 5 considers variety in the persons of bishops, the counterpoint of man against institution. Chapter 6 examines the stability of the cathedral chapter, whose members were more long-lasting and conservatively local than were the bishops, and compares the chapter with other ecclesiastical institutional groups like monasteries and houses of friars. Chapter 6 is meant to restate the descriptive argument of chapter I, at a different level, with different intensity and depth, guided by the nature of the book's dominant institution, the cathedral chapter; chapter 6 means, in the rather plain imagery of institutions, to push hard to reveal the way in which forces for conservation and change worked against and with each other.

Chapter 7 deals directly with sanctity and heresy, twin expressions of relatively extravagant religiosity, particularly through the examination of one woman saint and one man heretic, and reactions to them. The heretic produces more talk; there is more sound around him; and, although it is almost entirely Latin talk, that does not entirely obscure the Italian sound beneath it. The heretic in his parody of sanctity and others' reaction to this parody offers a kind of diagram of what sanctity or at least piety have become, a century after Francis's death; the reaction to reaction offers, too, a new diagram of Reatine society in which the doors of city dwellings are hooked together by spreading gossip and begging friars, who go among them hostiatim . The heretic's world is both denser and more mobile than the saint's. The saint and the heretic are meant to suggest what, in a way, has become of the contrasting pair of participants in chapter 2, and to state again, in a different way, the counterpoint of chapter 5.

Finally, chapter 8, with at its center the examination of men's and women's wills, tries to bring together, around the examination of these articulate documents, what has been happening in this place during these centuries. I have chosen to describe here those wills, out of the larger group of wills, that seem most effectively to display what is new, and I think significant, so that they may stir to life this place, by now established, I hope, and do that particularly by showing what has become of the imitation of Christ. More generally I have tried to recall in specific person and image the themes and counterthemes of the book, to talk of religion, and to return the narrative, its themes and counter-themes, to the reality of specific place.

This outline has not suggested that the book will include a specific examination of lay or popular piety. I hope that by the time he or she has finished the book, the reader will realize why I think such considerations are generally mistaken and destructive. The outline does not refer to comparisons with other places, other times. This is a book about Rieti in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; it is local. Making it just that has been a hard choice, particularly for a historian constantly tempted to comparison. It can be seen formally as the third part of an informal trilogy: the first book was about one part of the English church; the second compared the English and Italian churches in general; the present book is about one part of the Italian church. But more choice is involved than this implies.

There are very important elements of church and religion that are almost, if not entirely, invisible in Rieti documents: confraternities, for

example, hardly appear at all, although their existence is clear. It is tempting to talk of what they must have been like, with evidence from other places—a normal thing to do, particularly in an age of anthropological history. But I have decided, as much as I can, except for that comparison necessary for definition, to stay within my own evidence, even when it is meager. The value of local history is, I think, to show what its historian thinks he knows happened, knows existed, in its one place—to offer that pure to other historians—not to fill in what must have happened, what reasonably would have happened. But this is a pattern that is very hard to follow, like pure nominalism, perhaps impossible—and what historian of the canons of Rieti could keep his eyes from wandering to the documents about the canons of Narni? Who can think of Filippa Mareri and Paolo Zoppo and not have in his mind Margherita Colonna and Peter of Morrone? And frescoes are not bound by diocesan borders.

Finally, I would like to protect whoever reads this book before he or she reads it, by putting in the reader's mind two kinds of confusion, which may help to keep him or her from finding evidence of religious activity too direct, from thinking time and memory are too straightforward, from accepting answers that are too solid and clear.

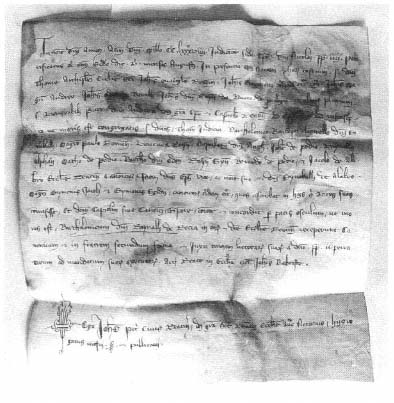

In his parchment cartulary, under the date 7 May 1315, Matteo Barnabei recorded that, in the proaulo (portico) of the papal palace at Rieti, Nevecta Gentiloni Petri Johannis once of Labro gave in perpetuity to the bishop (then Giovanni Papazurri), for the church of Rieti, a house and lot in the Porta Cintia de sopra, in the parish of San Donato, on the hill, but that she reserved for herself and her two nieces Johandecta and Nicolutia Petroni Nicolai once of Greccio, habitation in the house for the span of their lives that they might live there as in a hermitage or anchorage (in carcere ), and that she did this out of love of the church of Rieti and for her soul and for the remission of her sins. She with bended knee begged the bishop to accept the house and grant the anchorage; he in turn accepted and granted with the provision that the women should accept no other person to the place, with, among other witnesses witnessing, the nieces' father, Petrono Nicolai once of Greccio. It seems a moving enough little story—three women with their small-town heritages (Labro, Greccio) struck by the desire to live holy lives apart, closed within their own house, or the aunt's house, in the city parish of San Donato.[13]

But a few folios later Matteo recorded another action. On 16 August, still in 1315, Janductio the painter, formerly of the city of Rome, but

then a resident of Rieti, received the house back in Nevecta's name. The bishop, in the presence of sixteen canons of whom one, Ventura "Raynerii," objected to the act, gave back the house for two stated reasons: because the house was obliged to another for debt; and because the house and contrada were not appropriate (decens ) for an anchor-age.[14] What exactly is hidden behind the words of obligation for debts and of inappropriate place, and behind Ventura's objection, cannot be surely known. But one thing is certain: the action in August casts in doubt and complicates our understanding of the simple-seeming act of piety in May.

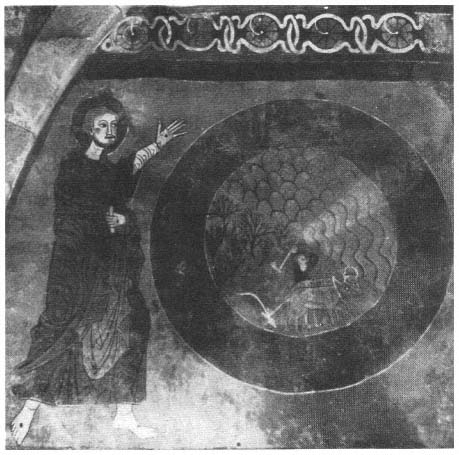

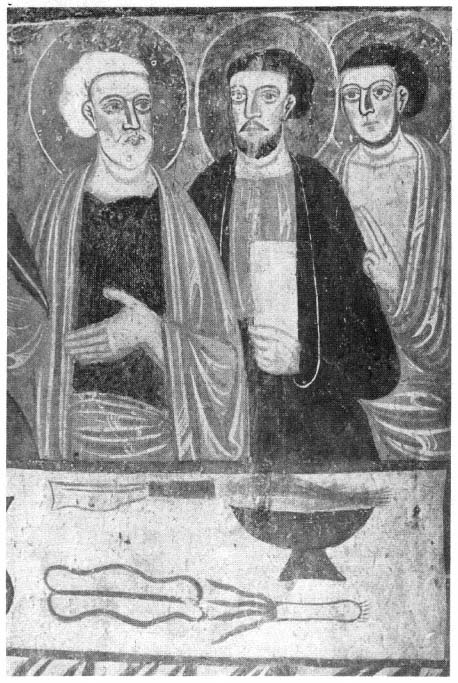

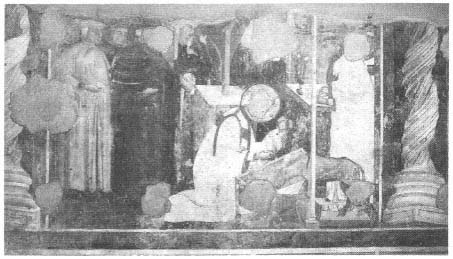

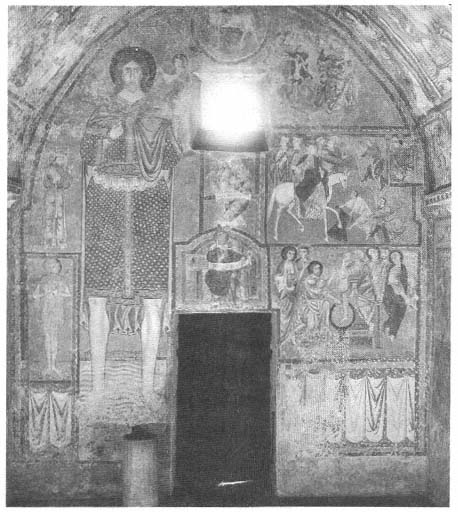

In 1224 the religious house of San Quirico near Antrodoco within the diocese of Rieti was engaged with the bishop of Penne in a struggle about jurisdiction over a group of churches locally within the diocese of Penne.[15] Among these was the twelfth-century collegiate church of Santa Maria di Ronzano near Castel Castagna, which with many of its twelfth-century frescoes still survives. One of these frescoes, from the Old Testament cycle, the creation of the world (plate 8), offers a last opportunity for warning the reader about the complexity of memory and time, the inventiveness to which both of these concepts, both continually important to this book, are susceptible. The God who creates the world of the fresco is Christ, the Redeemer, with the wounds from the nails clearly apparent in His hands and feet. The world He creates is a disc within a circling firmament decorated with heavenly bodies. The disc itself is cut as if by the letter X into four parts, of which the top three represent aspects of earthly nature. In the fourth a man brandishing an axe, as if to clear for planting, stands behind a pair of oxen pulling a plow: that is, a representation of the labor to which humankind was driven after the Fall.[16] No one who recalls the close connection between Incarnation and Crucifixion will be completely surprised by this kind of juxtaposition. But it serves, I think, as a cautionary exemplum. The memories, or reconstructed memories, of the people of this book, which recall the past of their own and earlier lives, sensible and generally trustworthy as they usually seem, live in a world of higher memory, the sequences of which are not always measured by succeeding days and hours.

1.

The same woman in the same room in the Valcellina village

of Claut in the Friuli (a) in 1962 and (b) in 1976. Photographs

by Italo Zannier. Reproduced by permission.

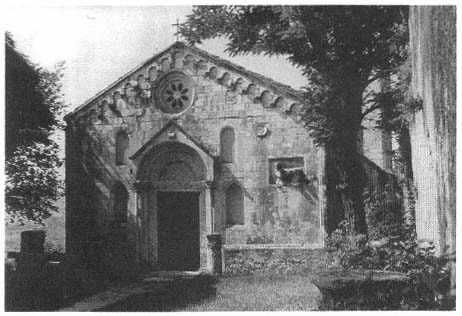

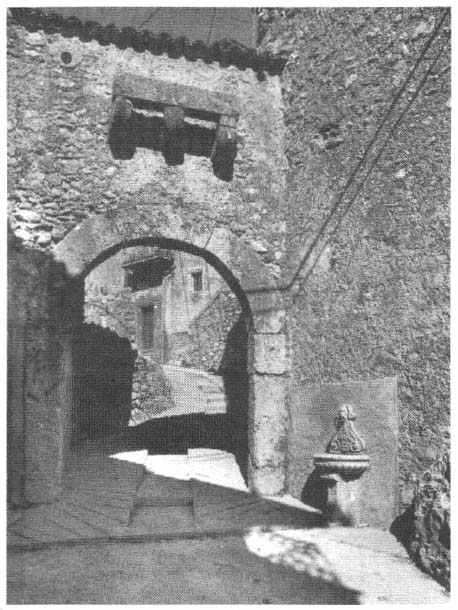

2.

Facade and north flank of the rural church of Santa Vittoria near Monteleone Sabina

reconstructed under Bishop Dodone in the mid-twelfth century.

Photograph by Barbara Bini.

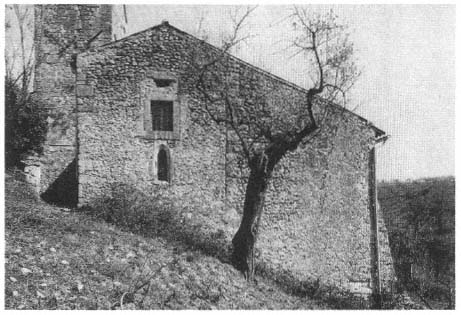

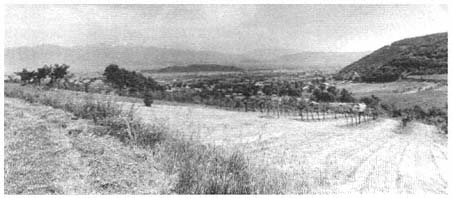

3.

The early country apse of Santa Vittoria near Monteleone Sabina with surrounding

olive trees and landscape. Photograph by Corrado Fanti, reprinted from Marina

Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina medievale (Milan, 1985),

by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

4.

Facade and south flank of the late thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century urban

Augustinian Hermit's (friar's) church of Sant'Agostino, Rieti, with its campanile.

Photograph by Barbara Bini.

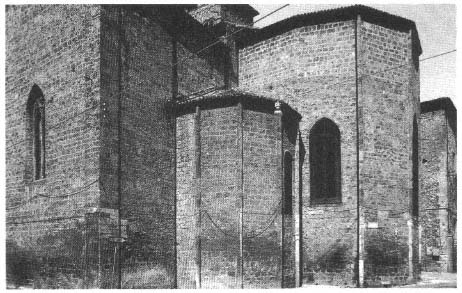

5.

The late city apse of Sant'Agostino within the thirteenth-century walls of Rieti.

Photograph by Corrado Fanti, reprinted from Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed.,

La sabina medievale (Milan, 1985), by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

6.

Fresco of Christ blessing, removed from the external wall of the small church of

San Sebastiano in Canetra, thought to be thirteenth-century, now in the museum

of the cathedral of Rieti. Photograph by Luisa Mortari, reprinted from Luisa Mortari,

Il tesoro del duomo di Rieti (Rome, 1974), courtesy of the Istituto Centrale per il

Catalogo e la Documentazione, Rome.

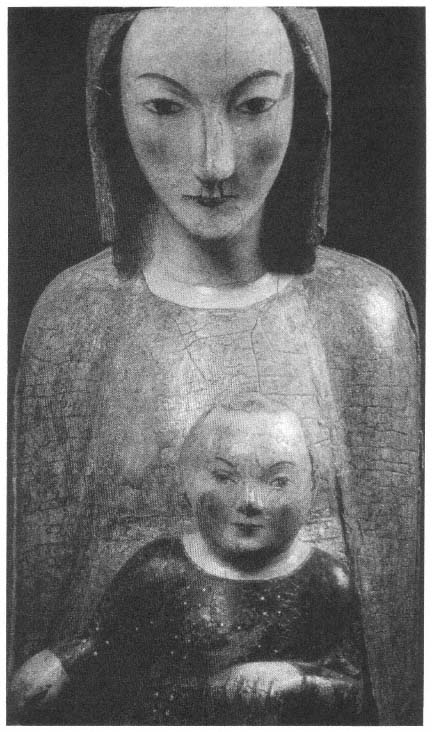

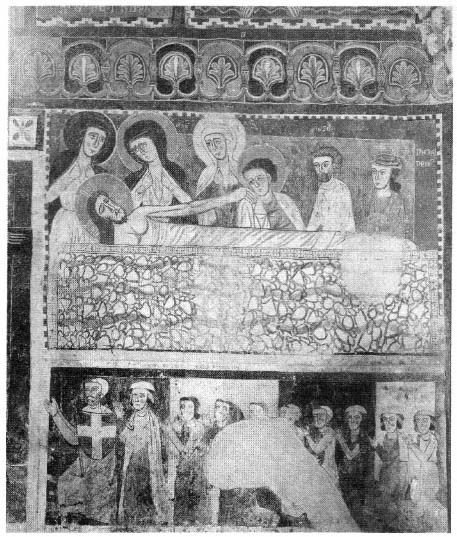

7.

Madonna and Child, portable statue (130 cm in height) in wood polychrome,

from the parish church of Santa Maria di Sambuco near Fiamignano in the

Cicolano, removed for restoration after heavy and prolonged resistance by the

parishioners, and now in the museum of the cathedral of Rieti. Photograph by

Corrado Fanti, reprinted from Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina

medievale (Milan, 1985), by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

8.

Creation of the World, twelfth-century fresco from Santa Maria di Ronzano near

Castel Castagna. Photograph reprinted from Guglielmo Matthiae,

Pittura medioevale abruzzese (Milan: Electa, n.d.).

Chapter One—

The Nature of Change, of Place, of Religion

In the very last years of the thirteenth and the first decades of the fourteenth centuries, in Rieti, three men made wills, specific and worrying and personal, which still reveal something of the quality of that part of each of their minds which can reasonably be called "soul." The first of these men was Nicola Cece, a citizen of Rieti but formerly of neighboring Apoleggia, who made a will in 1297, added to it a codicil in 1300, and wrote a new will in 1301; and he made the two wills in the refectory and chapter house of Sant'Agostino, Rieti.[1] The second was Giovanni di don Pandulfo Secinari, or de Secinaro, who made his will in the house of his dead father's sons (one of whom would become bishop) in Rieti, in 1311, but who placed in that will memories of his family's place of origin, Secinaro, across the border of the kingdom of Naples in the diocese of Sulmona.[2] The third was Don Giovanni di magistro Andrea, a canon of Rieti, who made his will in his own house in Rieti in 1319.[3] These wills form an articulate centerpiece in an arc of religious and ecclesiastical history which stretches from Pope Innocent III's heroic pronouncing and defining Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 to the beginning of the papal schism in 1378, and which stretches, with different emphasis and slightly different dating, from Francis of Assisi's brilliant (and, like the Lateran, remembered) presence in the diocese of Rieti in the years before his death in 1226 to the death of the third, and seemingly conventionally successful, Franciscan bishop of Rieti in an earlier part of 1378.

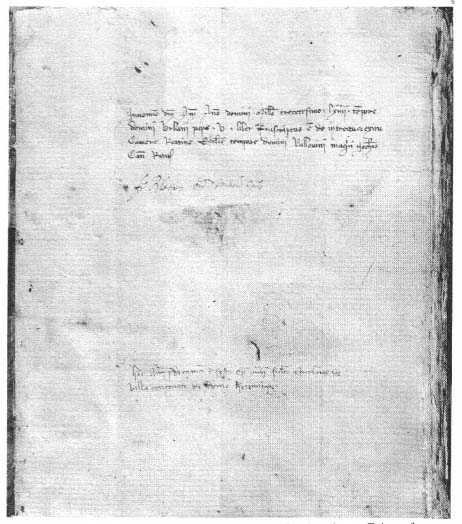

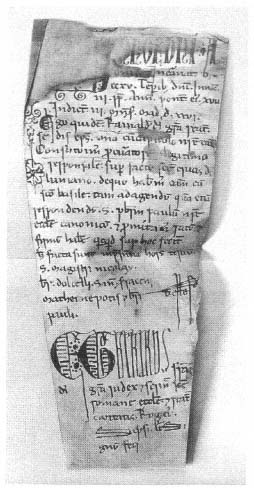

In spite of the sense of decline that one must get from seeing the

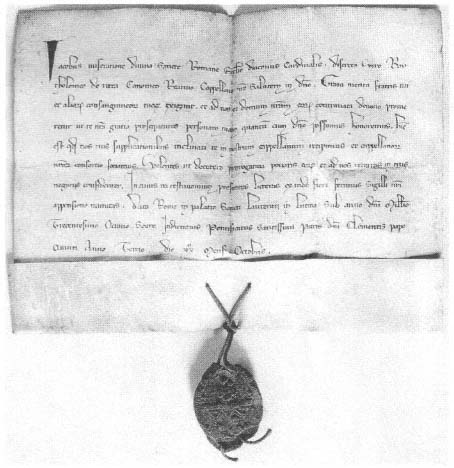

Schism and a conventional Franciscan bishop put next to, or rather following at a distance, the Fourth Lateran and Francis of Assisi, this arc or line of almost two hundred years was in a number of ways, some of which were very important, a line of, to use a word generally disliked by medievalists, progress. In 1227 in a precisely, but in a rather clumsily decoratedly formal, imperfect document, vertical, in an almost too careful curial hand, the Reatine citizen and scribe (scriniario ), Magister Matteo, wrote that in his presence Abassa Crescentii had given a letter sealed with the seal of the bishop of Narni to Bertuldo the son of the by then dead Corrado once duke of Spoleto. And Bertuldo had asked, "What is this letter?" And Abassa had answered that it was a letter which pertained to the case between Bertuldo and the church of Santa Maria of Rieti. Bertuldo had not wanted to take the letter, and he had said to Abassa, "Go and stick the letter up the culo of an ass."[4]

In contrast with this blunt command and the document in which it is preserved, one finds the epistolary elegance of formal and verbal content in letters to the church of Rieti from two neighboring territorial noble houses, the Mareri and the Brancaleone di Romagnia, who dominated the southeastern and the southern parts of the diocese in the mid-fourteenth century. These letters, about clerical livings, were written by baronial chancellors of humane accomplishment. They are small and beautiful and sealed with small and beautiful seals; and in them graceful phrase succeeds to graceful phrase. Most elegantly perfect of all perhaps is a paper letter of 1346 (but itself too elegant to bear a year date, only the indiction and the month and day), small (29 x 18 cm), horizontal, with a tiny (1.8 cm in diameter) black seal en placard , from Nicola de Romagnia, in Belmonte, exercising his right of patronage over the church of Santa Rufina in Belmonte and presenting to the chapter (uenerabilibus hominibus ) for that living, dompno Francesco di Sebastiano of Belmonte, and in this matter, reuerendam et uenerabilem paternitatem et amicitiam uestram affectuose rogantes .[5]

The contrast between Uade et mitte (go and stick) and affectuose rogantes (affectionately asking), which seems starkly to juxtapose a bear-like Germanic baron, old style, just stumbling out of his cave, and the Angevin elegance, almost perfumed, of a lord of Romagnia sitting in his airy view-filled palace on the pleasant heights of Belmonte, exaggerates. The Urslingen Bertuldo and the Brancaleone Nicola were both in their ways trying to maintain and protect their rights in property, including ecclesiastical property, and to ensure, presumably, the continued inheritance and prestige of their clans. It should be remembered

that during the period of mid-fourteenth-century central Italian raids and wars, physical savagery was not dead, and that it would be hard to make a case for its declining, and that the first bishop of Rieti actually to be freddato , murdered or assassinated, would be Ludovico Alfani in 1397 in a reaction against the growing tyranny of his, the Alfani, family.[6] Nevertheless the difference between "affectuose rogantes" and "uade et mitte" does signal a real change in Reatine communal and ecclesiastical behavior, a normalization, perhaps even civilization, certainly bureaucratization, which occurred between the early thirteenth and the late fourteenth centuries.

When the first at all complete surviving official records of Reatine communal discussion and action, the Riformanze of 1377, appear, they are productions of accustomed professionalism, elegant, beautifully written and composed by a communal chancellor, Giacomo di fu Rondo, of Amelia, a writer of considerable accomplishment, able exactly to describe the four horses assigned to him by the podestà.[7] In the presence of serious threats and dangers, like the lurking and threatening societas italicorum in Leonessa, the faulty state of fortifications, the lacerations left from recent violent disputes between Guelfs and Ghibellines (and the distinction between these parties, like that between noble and non-noble, is apparent and assumed when the Riformanze commence), and in spite of the expressed worry that since Pope Gregory would be returning into Italy reform would undoubtedly (absque dubio ) be demanded of the city and citizens of Rieti, the chancellor Giacomo, or he who dictated to Giacomo, was not only capable of phrases like "quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur," but also of finding that the greatest fortification that any city can have is concord, and stating the belief that great concord can naturally follow great discord, as after the tempest comes the calm and "post nubilem dat serenum."[8] All this, including the elaborate governmental structure which the Riformanze record, is unthinkable of the primitive communal government established under Innocent III, when Berardo Sprangone (or Sprangono), a local scriniario and judge, almost omnipresent in the documents of the church of Rieti in various guises but chiefly as authenticating scribe, seems to have become the first podestà.[9]

The development that the first Riformanze indicate, which is a development of surface, but not only of surface, is one which occurs, or is parallel to one which occurs, not only in ecclesiastical structure—in the actual organization and in the recording of church government—but in religion itself, in the pattern and space of religious exhilaration.

This is most obviously connected with the kind of pastoral reform which was pressed forward by the Fourth Lateran Council and by the coming, the influence, and the changing nature of the orders of friars—in Rieti most particularly the Franciscans, but also the Dominicans and the Augustinian Hermits. Inseparable from the friar's presence and pastoral reform was the changing interpretation of Christ's message, particularly through Matthew, and the changing understanding of Christ's self—even, again, in the way He looked, in image, out upon His people, and the way His earthly houses changed as they became in a new way His houses. They, these houses, changed physically and noticeably, particularly at Rieti in the creation of the great open, internal spaces of the churches of San Francesco, San Domenico, and Sant'Agostino, which were placed at three points on the periphery of the growing city, in the area between the old walls and the new thirteenth-century walls, as those walls were being built.[10]

This development is present in wills. From 1371 one finds a record of part of the execution of the will of Pietro Berardi Thomaxicti Bocchapeca, alias Pietro Jannis Cecis, of the city of Rieti, in which will, the document says, multa fecit legata , he made many legacies; and one was for the dowries of orphans, or the dowry of an orphan, or of a poor woman. Pietro's executors, among whom the presence of his wife, Colaxia, is emphasized, in order quickly and well to execute his will, searched vigorously through the city of Rieti, pluries et pluries , for poor orphans, and they found Stefania, daughter of the by then dead Gianni di Andrea Herigi; she was a poor, wretched, orphaned person, lacking a father, and a person of good reputation (personam pauperem, miserabilem, orfanam, et patre carente et personam honestam ). The executors settled upon her for her dowry a piece of vineyard in the Contrada Coll'Arcangeli.[11] This testamentary action is, in its way, fully expressed Christian charity of the new sort.

Pietro's, and Colaxia's, is a kind of charity, of interpretation of Christ, much more specific and extended than that suggested by the first relatively long and fully stated will which survives from after the coming of Adenolfo to the bishopric and Innocent III to the papacy, the will of Fragulino, written and authenticated by Berardo Sprangone in 1203. This Fragulino, a man of considerable property, was certainly the same Fragulino who is recorded as having been a consul of the city in 1188 and 1193, and so a man who connected the new governmental world of Berardo Sprangone with that which existed before Innocent III's reforms—a figure who shows continuity, a continuity extended by the

appearance of Fragulino's son, Berardo Fragulini, who gave gifts inter vivos for the sake of his father's soul and his own in 1206.[12]

Fragulino thought of his soul. He left the church of San Ruffo in Rieti 20 soldi for his soul. Without specifying purpose he left 20 soldi to the relatively aristocratic San Basilio of the Hospitallers, and one soldo to San Salvatore, presumably to the great Benedictine monastery south of Rieti and physically within the diocese. For what ought to come to him from the will of his brother Pietro Zote he made the church of Santa Maria his heir for his brother's soul and his own. He left more actual and residual money to Santa Maria and its clergy, 40 soldi (provisini) for the clergy and 14 lire (provisini) for the rebuilding (refectionem ) of the church. To the hospital capitis Arci he left 5 soldi. An uncertain but suggestive spiritual profile is drawn: family; attachment to the parish of San Ruffo, and perhaps to its neighborhood extending to San Basilio, with its tone of caste; a nod to a great old Benedictine monastery; and serious money for the cathedral church of Santa Maria particularly for building at what was probably a crucial point in the church's long building campaign. To this is added the 5 soldi for the hospital. These 5 soldi are in the line of the interpretation of Christ which will send Colaxia again and again through the city of Rieti searching for a poor orphan girl. But in the Fragulino will the interpretation of Christ remains relatively mute. One must imply the Christ of corporal acts of mercy, the Christ of Cana, who directly or indirectly provoked the soldi's giving.

The development from Fragulino to Pietro and Colaxia, however, is not so simply one of opening and blossoming as it at first may seem. Pietro's charity, or at least Colaxia's and her colleagues', is caught in a specifically institutional container. Stefania's vineyard dowry is to be hers only if, within two years time, she enters a monastery of nuns within, or in the immediate neighborhood of, Rieti, and takes her vineyard dowry to that monastery, and if she then dwells in habit there like the other nuns. If Stefania fails in this, the vineyard in Coll'Arcangeli is to go instead to a house of Dominican nuns, Sant'Agnese near Rieti.

Between the making of Fragulino's will and the execution of Pietro's, the great majority of religious thoughts, of those spasms of momentary piety, devotion and charity, which, within the diocese of Rieti, affected men's and women's minds and behavior, are of course untraceable. It might seem impossible with so much lost to try to sketch a line of development in this gauzy material; it is tempting to let it rest and to look only at the relatively solid lines of developing government and

institution. But these latter things are inextricably connected with personal piety, and they lose their meaning if they are detached from its more nebulous material. Besides, much does remain, and much that is poignant and moving as well as puzzling.

This pious and testamentary development took place in and around the small urban capital, Rieti, of a big rustic diocese which stretched to different distances in all directions from the city. In its specific Reatine form the development is inseparable from the place in which and the people among whom it took place. Even in thinking as narrowly as one could about Reatine religion one would have to think about, try to sense and see in some detail, what kind of physical place, or places, the city and diocese were, what kind of and how many people lived there, in what patterns of human settlement and tenure and in what kind of geography (mountains, rivers, plants, animals), with what patterns of speech, image, and behavior, and to know something of what they produced besides prayers and churches, wills and heirs. Moving from city to country, and to town or village, from the rules of a great barony to the many speaking voices of a rural inquest and to the amplified voice of a single reacting bishop perhaps will create, at least, a sounding board for the Reatine sermon.

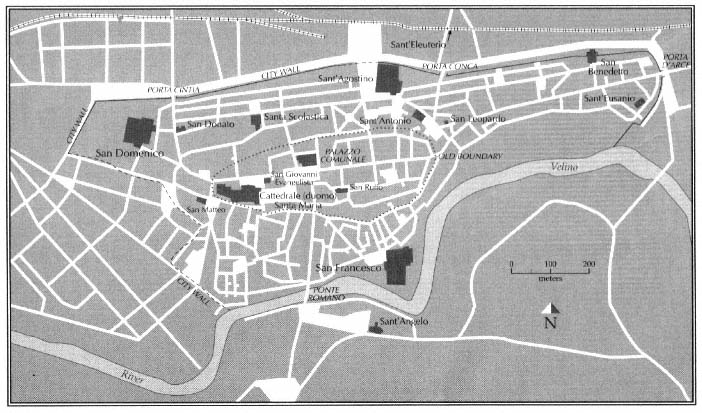

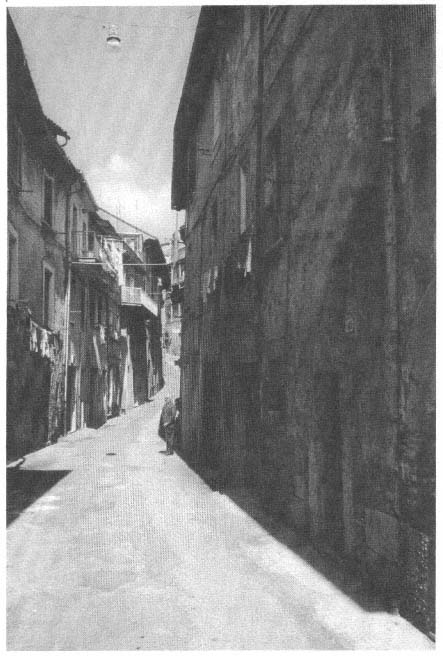

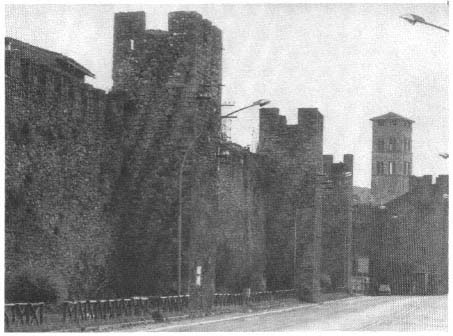

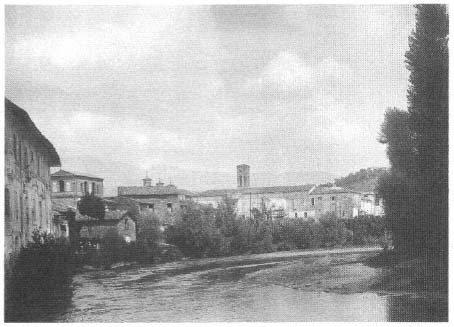

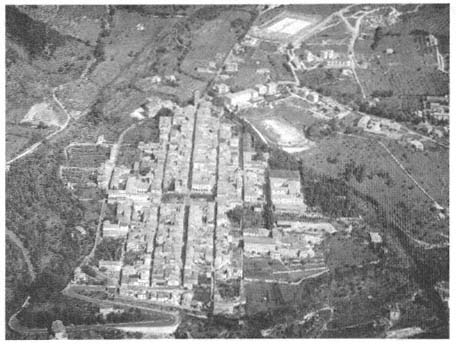

The city itself, for all the surrounding rusticity, was (and is) in the center of Italy and only about eighty kilometers, on the Via Salaria, north and slightly east of Rome.[13] The early thirteenth-century city (plate 9) stretched from west to east in an extended and uneven oval for 1,200 meters (which was at its widest point about 450 meters from north to south) on an outcropping (402 meters above sea level), a ridge above, and north of, the river Velino, where the river was met by the Via Salaria coming from Rome, and where parts of the Roman bridge remain. At the westernmost end and highest part of the ridge stood the cathedral complex with its piazza; close by to the east and slightly to the north developed the building and the area of the palazzo comunale on the site of the Roman forum (see map 3).[14] By the end of the thirteenth century the walled city had been extended in all directions (plate 10) but particularly to the east toward what became the porta d'arce , so that the city's total length from east to west had grown to slightly more than three kilometers. It was extended into the flat land to the north and down the hill to the Velino in the south (plate 11) so that at points it measured a kilometer, or slightly more, from north to south; and it was joined across the Velino, where the river was met by the Via Roma coming down the hill, by a borgo , a suburb, in the neighborhood of the

3.

The city of Rieti.

church of Sant'Angelo. The new walls enclosed the recently established complexes of the Augustinian Hermits to the north (within the wall west of the porta conca ), of the Dominicans to the northwest (in the corner of the city beneath the cathedral and to the west of the porta cintia ) and the Franciscans to the south (actually bound by the Velino not the wall, east of the Via Roma); but they also enclosed another important communal complex, close to and southwest of the Augustinians, the Piazza del Leone, where in the early fourteenth century would be erected the palazzo del podestà.

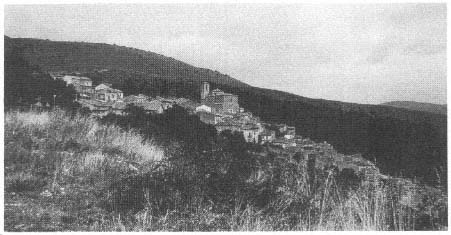

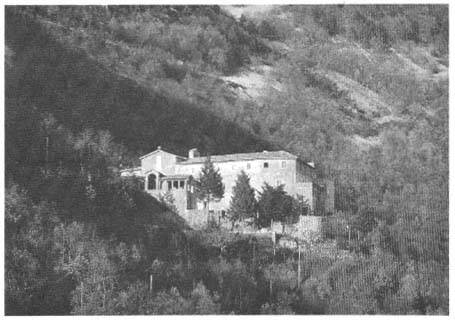

By the end of the thirteenth century the walls enclosed not only the entire new cathedral dedicated to Santa Maria, which had been consecrated by Pope Honorius III in September 1225, and significant portions of all three of the friars' complexes, but also the new cathedral campanile, which says that it was constructed in or after his first year by Bishop Tommaso (1252–1263/5), and the new episcopal-papal palace which Bishop Pietro da Ferentino (1278–1286) made to be constructed (at the time of the podestà Guglielmo da Orvieto) in 1283, with a loggia added in 1288, under Bishop Andrea (1286–1292/4)—(from the time, as it says, of the podestà, Accoramboni da Tolentino)—and, from just before the turn of the century, the Arco del Vescovo, which bears Pope Boniface VIII's family arms.[15] A list from Bishop Tommaso's time, which does not here include Santa Maria or the friars' churches, does include twenty-nine functioning, or at least census-owing, churches under the rubric: ecclesie de ciuitate.[16] It was to this newly enlarged and monumental complex on its ridge above the Velino (plate 12), that members of the Secinari family, one of whom would become bishop, would come, around 1300, returning from their name-giving Abruzzese village, Secinaro (plate 13), to their Rieti house, perhaps already located in the position of their later palazzo on the Via Roma.[17] The contrast must sometimes have shocked them, but so too, except for scale and monumentality, must sometimes the similarity of the two, Rieti and Secinaro, have been assumed by them, human communities, on their ridges, of normal sorts in the rough pitted terrain in this central part of Italy, in spite of, in Rieti's case, the vastness of the great drying basin to its north.

About the actual population of Rieti, before and after the Black Death, it is only possible to guess. By the end of the sixteenth century, when it is possible to do more than guess, Rieti had a population of around six thousand people.[18] With this figure in mind, and with in mind the comparison of Sulmona, which in the late fourteenth century

reached a similar figure, it certainly seems possible to say that, late in the thirteenth century, at least, Rieti's population could well have reached a figure around four thousand.[19] But this is speculation.

Rieti, once a Sabine center, had, under the Romans, become a Roman city; it was the home of the Flavians and appropriately of the agricultural expert Varro. Under the Lombards it had become part of the duchy of Spoleto. It had been the name-giving center of a gastaldate and then a county, which it remained into the twelfth century. Rieti was the victim of memorable and remembered destruction by Roger of Sicily in 1149. Its recovery and rebuilding were accompanied by the growth of communal government under the local direction of consuls. By the end of the century it had come under papal control.

Rieti's continued existence as a governmental center, if this is not too grand a term, was reinforced by its position as an episcopal see. Its traditions connected it with the blood of martyrs, and a fleeting reference to its church is found in the letters of Gregory the Great. Its episcopal position, and memories, were strengthened by the long and seemingly relatively effective episcopate of the twelfth-century bishop Dodone, at least from 1137 to 1179. Still Rieti remained essentially a secondary market and trading center at the heart of an agricultural and pastoral area dedicated particularly to the production of wine and grains, as well as garden and animal products and fish.[20]

From Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) Rieti received two important but not disinterested gifts. Rieti became a free commune, although not free of an annual census, with its own government organized under a podestà. It also became an intermittent papal residence. The city thus entered the thirteenth century, a period of almost universal demographic growth, the period of the growth of its own walled space, with two shaping advantages. Its communal government was able to survive and develop through two periods of violent disorder in central Italy: the wars between the papacy and the emperor in the second quarter of the thirteenth century and the period of seeming chaos and continuous partisan disruption, warring of private armies, and Neapolitan royal infiltration, from the time of the papal retreat from Italy in 1305 particularly until the coming of the legate Cardinal Albornoz in 1353 and the Reatine agreement with him in 1354.[21] There is considerable evidence, especially from the (in many ways more distracting) latter of the two periods, for the continued ability of communal institutions to focus elements of power, both shifting and continuing, within the city, to allow it, the city, to resist, although certainly with mixed effectiveness,

potentially intrusive external forces, royal and baronial. It could be argued that the efforts of the early Angevin kings of Naples, in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century, to strengthen their Abruzzese borderlands with new income- and defense-regulating, relatively urban, planned and gridded communities, like Cittaducale (plate 14) and Leonessa, not only threatened Rieti but helped it, by placing it within a better ordered general neighborhood, and so in some ways echoed the helpful papal organization of territory and border under Innocent III. Certainly in the absence of the papacy, in spite of the presence of papal governors, Rieti was drawn much more heavily into the ambit of the kings of Naples; and it might have been helpful to Rieti if they in fact had been stronger kings.

But Rieti, with its own constitution developed and intact, and visible within its first statutes and its earliest existing Riformanze, survived; and, in the end, it itself, its urban center, survived outside the borders of the kingdom of Naples.[22] Both the army of Rieti, the exercitus Reat' , camped in siege outside the gate of Lugnano in June 1251, and the (particularly nonclerical) counselors from Rieti, asked to help decide whether or not the heretic Paolo Zoppo should be submitted to torture in 1334, suggest the continual existence of a body of responsible and relatively weighty Reatines, of diverse background, substance, and experience, who in their different ways could represent with their strength and wisdom the more general community—a thing which itself existed, was thought to exist, and which could survive partisan fragmentation.[23] In surprisingly similar terms could be described the composite chapter of Rieti, of the cathedral of Santa Maria, representing its church and community.[24]

Innocent III himself came to Rieti. There in 1198, we are told, he consecrated the church of San Giovanni Evangelista (in Statua).[25] One hundred years later in 1298, Innocent's distant successor Boniface VIII came to Rieti and there, it is reported, threatened by the violent earthquakes of November, he took himself from celebrating Mass to the relative physical safety of the cloister of San Domenico.[26] Five thirteenth-century popes, including Innocent and Boniface, the first and the last, together, spent, with their courts, 1,226 days in Rieti: Innocent III, 28 days; Honorius III, 239 days; Gregory IX, 547 days; Nicholas IV, 302 days; and Boniface VIII, 110 days.[27] Popes came to Rieti eleven times for periods ranging from 28 to 547 days; in terms of time spent there, it was the fifth most popular of thirteenth- (and very late twelfth- and early fourteenth-) century central Italian papal residences outside of

Rome: after Viterbo, Anagni, Orvieto, and Perugia.[28] And the popes did not come alone. They came with hundreds of followers (some of whom preceded them to make arrangements), of whom five hundred or six hundred were direct dependents of the papal curia.[29] They packed or bloated the cities at which they arrived. They drastically altered the cities' demands on housing and public services and provisioning. They pushed rents up to as much as four times their normal figure. Some of them demanded hospitality and in what seemed unreasonably spacious quarters.[30] They caused expensive damage and they required protection.[31] They brought many problems and obvious discomforts to the host community; they threatened its fabric. But on the whole they (and the real or presumed economic benefits of their presence) seem to have been much desired, courted, built for; their potential and actual presence seems generally to have improved the facilities and increased the monumentality of the host city, to which they themselves came for various reasons: to strengthen papal presence in the area, to avoid the danger posed by Roman or Rome-threatening enemies, to escape the pain and illness of a Roman summer in a place as seemingly fresh and cool as Rieti—Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi's sweet Rieti (amena Reate ), beneath its mountains and above its waters.[32]

The exact effects of the curia's presence on Rieti and the negotiations leading to that presence are not visible as they are at Viterbo and Perugia, but clearly the monumental center of Rieti, the papal-episcopal palace (built under curial bishops) and the arch of Boniface VIII are connected with attempts to attract the court to, and/or to keep and please it at, Rieti. So may have been, for example, the important fountain in the Piazza del Leone.[33] The late thirteenth century, between the battle of Tagliacozzo (1268) and the popes' departure from Italy, was a time of relative peace and of monumental building and decorating for central Italy; into this pattern the Rieti palace fits naturally, but its specific reason is surely papal presence.[34]

The papal curia brought the world and the world's events to Rieti. In 1288 and 1289, Pope Nicholas IV spent the summer, from mid-May until mid-October, in Rieti. In Nicholas's second year there, Charles II, the new king of Naples, recently freed from the imprisonment in which he had been held hostage, came, with a great following, to Rieti, and on Pentecost, in the cathedral, was crowned king. In memory of this event Charles promised the church of Rieti an annual gift of 20 uncie of gold from the royal treasury, and so an additional financial benefit came to the city, or at least to its church, from the presence of

the papal curia there; but it was not a benefit without eventual problems or one the installments of which would always come free, as is clear from Bishop Giovanni Papazurri's excommunication, in 1311, of any canon who did not pay his share of the money required in order to get the 20 uncie from King Robert, and also in 1332, from the making of proctors by Bishop Giovanni's vicar and the canons of Rieti to appear before the king and dissuade him from any reduction of the sum. In the papal-royal summer of 1289 Rieti was further swollen by the presence there of the thirteenth chapter general of the Franciscan friars minor, men from all over.[35]

The chapter general calls attention to the provenance of the friars resident in the local houses of Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinian Hermits.[36] They were not from the whole world, and they were not all strangers, but the majority of those who can be identified did not come from Rieti or nearby villages but rather from other Italian places. In the early fourteenth century, after the second of the two periods of papal sojourns, and after many Reatines had themselves become members or followers of the papal curia, Rieti, with its Roman Papazurri bishop, was certainly not a place sealed against the outside world. Witnesses and actors who appear, for example, in the parchment cartulary of Matteo Barnabei, for the five-year period 1315–1319, suggest a generous presence of resident strangers.[37] There were signal figures with specific skills: Janductio the painter from Rome, and Magister Jacques, the physician from the diocese of Le Puy-en-Velay (Pandecoste), who had become a resident and medico of Rieti; but there were plenty of others, of course, from neighboring places like Labro, Morro, Greccio, Monteleone, Montereale, Poggio Bustone, but also from more distant and distinct places like Viterbo, Norcia, and Siena, and a sizable number from Rome.

Not all Reatines were Christians. There were Jews in Rieti in 1341, and the nature of their appearance makes it clear that they had been there for some time, if not in great number.[38] On 1 April 1341 in the house of Vanni di Don Tommaso Cimini (or de Ciminis), with as a witness Matteo di don Filippo Pasinelli, "Manuelis Consilii Judeus" came forward to act for himself and a group of some ten named associates, from a somewhat smaller group of families, men with names like those of the brothers (in the genitive) Abrammi and Salomoni alias Bonaventure , sons of the now dead Magister Bengiamini —a high proportion of magistri . Manuelis was present to come to an agreement, to end discord and litigation, with the brothers Musictus and Gagius, sons