Preferred Citation: Khater, Akram Fouad. Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, c2001 2001. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9d5nb66k/

| Inventing HomeEmigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920Akram Fouad KhaterUniversity of California PressBerkeley Los Angeles London© 2001 The Regents of the University of California |

To Jodi, rūhayn b-rūh

Preferred Citation: Khater, Akram Fouad. Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, c2001 2001. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9d5nb66k/

To Jodi, rūhayn b-rūh

Acknowledgments

Surrounded by my research notes, books, and articles, I spent the better part of two years tapping away at the keyboard of my computer in an attempt to write this book. Alone with my own thoughts, I alternated between reveling in crystalline visions of my intellectual purpose (alas far too briefly) and being lost in a labyrinth of ideas so twisted as to induce hyperventilation. With such a contradictory existence (which climaxed at times in hysterical laughter), it would have been far too easy to become hopelessly lost on my scholarly journey—never reaching an end point. However, the support, advice, critical readings, and sense of humor with which colleagues and family showered me helped me stay the course and reach the moment when I can acknowledge all that they have done on my behalf.

Research is a rather expensive undertaking. Thus, the financial support of scholars has, and continues to be, crucial in their work. My case is no different. I was able to undertake this work only because of the extremely generous support of the Fulbright Commission (DDRA grants), a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (which permitted me to take a year's leave of absence from my university), a grant from the American Philosophical Society, and last—but certainly not least—the support that my home institution, North Carolina State University, has afforded me through several research stipends and grants.

In gathering information for my project, I have been aided by the constant support of numerous archivists and librarians. First and foremost is the interlibrary loan staff at North Carolina State University: Marihelen Stringham, Gary Wilson, Baker Ward, Ann Rothe, and Mimi Riggs. Despite my endless—and sometimes unreasonable—requests, they never failed to work hard and creatively in tracing even the most esoteric of manuscripts. And, despite my chronic tardiness in returning books, they still accepted my requests for yet more books with kindness and hardly a reprieve. At the archives of the Smithsonian Museum of American History, I was most fortunate to be able to make use of the Alexa Naff Arab American Collection. Gathered and indexed through the diligent work of Alexa Naff—herself a pioneer in the study of Arab emigration to the United States—this collection proved to be a treasure trove of glimpses into the lives of some emigrants from Lebanon. Cathy Keen, the archivist in charge of the collection, was most generous with her time and advice about finding particular documents within the collection. Finally, the librarians and archivists at the Jafet Library at the American University of Beirut made every effort to facilitate my work there—from welcoming me as a researcher to helping me obtain the only remaining copies of many magazines and newspapers published at the turn of the twentieth century in Lebanon.

Beyond research stretched the whole expanse of the writing experience. Once I began to write, I needed, and received, all the help I could get. Most critical in this process was my wife, Jodi. Without her, I can say in all sincerity, this book would never have been completed. Her support sustained me at more than one level. She comforted me through my anxiety-ridden episodes, when I came to the conclusion that the whole business of writing was pointless and absurd. But, more critically, she helped me focus on the subject of the book through long and patient hours of discussions and intellectual explorations. She kept pushing me to clarify my ideas in the simplest language, never allowing me to obfuscate my intellectual uncertainties with jargon. She read everything I wrote more than once and wrote extensive comments that never failed to improve my narrative and give my ideas a meaningful structure. The best parts of this book are as much hers as mine.

Many colleagues also gave selflessly of their time by reading my manuscript at various stages. The first person to see merit in my subject was my mentor, Edmund Burke III. He was kind and patient enough to work with me as an entering graduate student with little training in the field of history. He helped me grow intellectually through many hours of discussion, debate, and argument. His persistent, yet gentle, criticisms of my work served only to make me a better historian. I will always treasure his friendship through the years and his hospitality. In more recent times, I have had the privilege of receiving advice and support from one of the best historians I have ever known, David Gilmartin. David, whose sense of humor and sharp intellect are legendary in the history department at North Carolina State University, spent many lunches (sometimes in the same day) discussing ideas, methods, and analytical categories of history. He always questioned my thoughts in a way that made constructive sense and made me go back to the manuscript with a clearer sense of purpose. (Buying me lunch also helped out greatly, although I wish he did it more often.) Anthony La Vopa was another colleague who had to suffer through an early version of this manuscript—while vacationing, no less. He meticulously went through every page locating gaps—large and small—as well as identifying strengths. His sense of humor about my trials and tribulations was the perfect antidote to my feelings of persecution and self-pity. Alex DeGrand also read and commented on the manuscript, always graciously and encouragingly praising my effort and propelling me forward with his kind words. Holly Brewer, my office mate for the first four years of my tenure at North Carolina State University, opened my mind to new possibilities in my work through her conversations about American history. Many other colleagues in the department also contributed through years of dialogue and seminar presentations—all of which advanced my knowledge and my training as a historian. I thank them all.

Outside my university, I have been most fortunate to have colleagues who cared enough about my work to take time from their extremely busy schedules in order to give me valuable comments. I thank my two anonymous readers; they caused me much agony through their unwavering, and correct, criticism of the first draft of this work. I received both sets of comments over the Christmas break and thought to myself that they were the most painful presents I had ever received. Yet, without their critiques, this manuscript would have been far poorer in analytical substance. I also would like to thank Beth Baron, whose comments on one of my chapters were instrumental in shaping a better version of it. I owe a debt of gratitude also to Sarah Shields and William Merryman; we spent many delightful Sunday afternoons speaking of many things, including this manuscript. Their friendship and hospitality are treasured.

I would like to also thank my editor, Lynne Withey, for the encouragement and the unfailing support she gave me and this manuscript. In addition, I would be most remiss if I did not thank Pamela Fischer, who did a superb job editing my manuscript.

A word of thanks goes to my brother Emile Khater and his family for their generosity and hospitality in Lebanon and to my brother Tony and sister Amale and their families' unfailing love. Finally, I must thank our two little daughters, Lauren and Micah. Both did all they could to keep my spirits aloft. Lauren went through the manuscript checking my reference notes against the bibliography (I paid her, of course); Micah drew me a picture with the caption “Cheer up Akbam.” It still hangs on my desk. And both did all they could to drag me to the swimming pool during the long summer days of writing—a diversion that was refreshing and welcome.

I would also like to thank Bruce Lawrence and Miriam Cooke for their suggestion of the title of this book.

1. A Departure from the Ordinary

There were 72 of us, we went to Beirut where we remained for eight days, living outdoors. . . . Finally, one night the Beirut agents came and said “let's go.” They directed us through a small canyon and we continued walking until we got to the sea. There were three Turkish officers there whom they bribed. Then they put us in an open boat and took us to Cyprus which was under British rule. And they got us tickets for a French ship.

– Michael Haddy, interview, 1962.

This is how Michel Haddy described his journey to the United States. After a circuitous voyage through Beirut (where the passengers did not disembark) and Alexandria, the ship deposited the villagers from ‘Ayn ‘Arab in Marseilles. From there they traveled to Le Havre, where they and “about 250 Syrians from Zahlé, from Matn, from everywhere” boarded another steamboat for New York. Eighteen days later they emerged from amidst the “cattle, pigs and other animals and the terrible smell,” terrified that they would be turned back. “But thank God no one from ‘Ayn ‘Arab was rejected.”[1]

There are over two hundred thousand such stories of predominantly Christian peasants who left their villages in Mount Lebanon to travel to the Americas in the twenty-five years following 1890. Their departures from their quotidian lives into a world unknown to them, except through a mist of physical and mental distance, are remarkable. Yet few historians have chronicled these extraordinary voyages, and those who have recount only part of the story.[2] Their books tell not always accurately of the reasons which prompted peasants to leave their mountainous villages. They speak of the voyages and the arrivals in the mahjar, the money they sent back, and the “assimilation” of those who stayed.[3] But nothing is said about a host of other matters, the most critical of which is the story of return. Except for a sprinkling of passing remarks, we never encounter those many who went back to the Mountain. We learn nothing about their experience of return, what they brought back with them, how they were received, and their role in the making of “modern” Lebanon.

This book is intended to remedy such oversight by tracing the journeys of these villagers from the ranks of the peasantry into a middle class of their own making. I wish to write of the struggles of Lebanese peasants to control their destiny amidst the swirling forces of the world capitalist system. And I wish to remedy the scholarly silence about the social history of Lebanon between 1860 and 1920. Most important, however, and in addition to these two issues, I believe that the journeys of peasants have much to tell us about the historical dynamics which made “modern” Lebanon. Embedded in these travels are the stories of how new notions of gender, family, and class were articulated and of how “modernity” was invented in the process. My intent is not to draw a linear and inevitable line between a peasant start and a middle-class end along which these peasants dutifully marched into a spot in history. Instead, I will try to map out the jagged and uncertain paths which the fellahin from Mount Lebanon carved through time and space in their attempt to control their future and their destinies. Along the way, this narrative will shed much needed light on the impact of emigration and immigration on “nations,” it will explore new areas in the history of Lebanon, and it will delve into the complex relationships among gender, family, and class.

More specifically, in unpacking these narratives I wish to elucidate how a class was formed both socioeconomically and culturally. This analytical duality is essential, yet it has been largely missing from studies about the Middle East. Studies about “modernity” in the Middle East have tended to concentrate on the cultural construction of this imagined state of being. This cultural emphasis has been a most welcome addition to the field, one which has helped shed significant light on seemingly well-worn subjects and has as well introduced new images into our historical vision. However, the great majority of these works set about deconstructing “modernity” without explaining how a “middle class” came into existence in the first place. Constructing such an explanation is necessary not merely to satisfy curiosity; it is rather a critical step toward a more sophisticated and organic understanding of the making of the “modern.” This additional analysis is necessary because the processes through which a class forms in classical socioeconomic terms shape the construction of its particular ethos, even as that culture helps to maintain and shape class boundaries. Or, as Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid note for the case of India, “the relation between classes and patriarchies is complex and variable. Not only are patriarchal systems class differentiated, open to constant and consistent reformulation, but defining gender seems to be crucial to the formation of classes and dominant ideologies.”[4] Thus, our comprehension and explanation of the rise of “modernity” will remain lacking unless we incorporate into our narratives an examination of the socio-economic journeys of the middle class, which embodied and exuded “modernity.” Only then can we possibly overcome the circularity of the middle-class narrative which places it outside history.

Finally, through exploring the journeys of these peasants, I want to elucidate how the “traditional” past of this new class was integral to the making of its own “modern” — xa set of ideas and a material culture that its members subsequently used to distinguish themselves from their peasant heritage. In consciously tracing the links between the two historical times and groups, we can discover that the culture of the peasant past remained ever-present in the modern lives of middle-class men and women. This past was not a mere residue but a powerful factor which contoured the shapes of the “modernity” that many ex-peasants were engaged in constructing as they remade themselves into a middle class. Only by taking this mental step back and looking at the larger process can we fully appreciate its engineering complexity. Beyond marveling at accomplishments, through this retreat from a narrow historical focus we can discard the artificial bipolarities of “modern” and “traditional” because it renders them meaningless.

In order to further elaborate the premises of this book, I will proceed in the remainder of this chapter to discuss “modernity” and the ways that class, gender, and family were used to construct this state of being. Additionally, I will define what I mean by these terms through a discussion of their theoretical employment in current scholarship, as well as by introducing my own extensions of some of those definitions. In a subsequent section I will explore the relationship between emigration and the making of “modernity.” I will conclude by presenting a sketch of the contents of the book.

A Local “Modern”

“Modernity” is an elusive term. Yet, ever since the Industrial Revolution, “modernity” has figured prominently in “Western” discourses. Many Europeans came to identify themselves—not in an entirely comfortable manner—as “modern.”[5] The idea and the term have been the subjects of intense scholarly interest, debate, and arguments beginning with Marx and Weber and reaching to the present.[6] Similarly, beginning in the nineteenth-century, “modernity” came to occupy an increasingly prominent position in the words and programs of “reformers” in the Middle East. Newspapers, speeches, and government edicts were filled with words such as reform, new, modern, scientific, advanced, and rational. From the policies of the Tanzimat in the Ottoman Empire to articles in the nascent women's press in Iran, Egypt, and the Levant, the focus for an emerging middle-class elite was on “modernizing” family, society, and nation. To varying degrees, both the European imperial and the indigenous discourses on the “modern” came to depend on—and construct—absolute polarities of modern and traditional, secular and religious, rational and emotional. Within the European imperialist narratives, these dichotomies were all located around a new colonial geography which separated the world neatly and profoundly into West and Orient. Many local—and later nationalist—discourses on the “modern” reacted to this colonial mapping of the world by emphasizing their “modernity” in the face of claims to the contrary. In other words, they accepted this polarity but rejected the label of being “traditional”—even as they sought to redefine, successfully and otherwise, that “modernity” after their own images.

To transcend the historical obliqueness of these construed dichotomies, we must, as Paul Rabinow argues, look at how ideas of modernity have been produced and reproduced at particular historical times and places.[7] Scholarship on the Middle East has begun to do just that. For example, various scholars have looked at how the category of “woman” was invented, defined, and produced for mass consumption at the level of the upper and middle classes.[8] These studies are meant to explain how creating a “scientized” cult of domesticity within an isolated nuclear household presided over by women and dedicated to reproducing and rearing good sons for the “nation” was integral to the larger projects of “modernization” that were taking place in many areas of the Middle East. All was “rationalized” on the premise of liberating women by ascribing positive attributes to these roles and by providing young girls with new educational opportunities and an improved material life. Yet, this project was simultaneously creating a new patriarchal order that subjected women to “new forms of control and discipline.”[9] Gender, in this critical context, becomes a contingent individual identity as well as a set of social relations. Both are imagined and applied in any one particular configuration because of the confluence of economic, social, and political forces at a specific historical time. In turn, gender shapes other sets of identity, like class and sect, and becomes an integral element in the making of other imagined communities, such as the “nation.” Thus gender is not simply a “social category imposed on a sexed body” but is instead a part of every other set of social relations whose transformations make up history.[10]

Equally, the meaning of the term family becomes far more fluid when viewed from the perspective that these new studies of “modernization” are affording us.[11] For example, by examining the discursive formulations of the “nuclear” household over time, these studies oblige us to abandon the assumption that a family is a fixed and static structure that is constantly reproduced through procreation and socialization.[12] Instead, we find that the family has to be contextualized as yet another set of dynamic social relations between individuals of varying ages with rather unequal decision-making powers. Furthermore, these relations are not set but vary over time in relationship to external and internal changes. For example, as other scholars have noted and as we shall see in this book, the role and meaning of “mother” within a family changes over time and not always in a coherent manner with which every member of the family is comfortable. Likewise, the responsibilities of parents to children, and the reverse as well, change with the increase in educational and physical distance between them. Conflict between individual desires and familial obligations creates tensions that alter the power dynamics within the family and change the nature of its constitutive relations. In other words, family—like gender, nation, and class—is a construction whose meaning and meaningfulness are contested from within and without at particular historical times. The articulation of family, gender, and class is, in turn, embroiled in the project of “modernization.” So, to be “modern” is to be a “nuclear” family, and a “nuclear” family projects an air of “modernity.”

Thus, in questioning the ways “woman” and “family” were construed, I—along with other contemporary scholars—seek to critically appraise and understand the dynamics of the process of “modernization,” which lasted through the better half of the nineteenth century and is still continuing today. In other words, we attempt to define the “modern” in the Middle East by examining the particular ways that the categories of “women,” “family,” and “class” were articulated.

But we need to go beyond examining the hidden elements which make up the “modern.” We need to understand the multiplicity and the contradictory natures of the discourses that collectively make up the historical process of “modernity.” As anthropologist Michelle Rosaldo put it, we need to pursue a meaningful explanation and not a universal explanation of causality.[13] More to the point, and as Michel Foucault suggested, for the notion that social power is unified, coherent, and centralized we need to substitute a concept of power as dispersed groups of unequal relationships, discursively constituted in social “fields of force.”[14] In other words, we cannot assume that “modernization” was a monolithic and seamless construction. Rather, the competing arguments that arose in the face of the new ideals of a domesticated “womanhood” and an enfeebled femininity were part of the making of the “modern.” Many such “voices” represented differing interests. Religious elites were loathe to accept the secularization of morality, wherein women come to be the arbiters in—however limited a form—of societal mores and habits. Conservative observers saw in Qasim Amin's “New Woman” a threat to “classic patriarchy.”[15] However, feminists, who were working from within the confines of the emerging middle classes, sought to dismantle the separation of their daily world into gendered spheres, where women were to occupy a disempowered, if gilded, home. They used the language of rationality and science to perforate the boundaries between these spheres and to challenge the new roles. Yet the language which they used was embroiled in the project of “modernization” and thus limited in its ability to disassemble the edifices of gender inequality. Herein lies a problem that a few scholars, such as Mervat Hatem and Marilyn Booth, have begun to remark on.[16]

However, even acknowledging and investigating the dialectical intricacy of “modernization” projects is still not sufficient. I strongly believe that to complete the debunking of the mythology of “modernization” we cannot continue to confine our analytical attention to the boundaries of its culture and to the language of its self-making narratives. Such a restricted analysis would by necessity limit us as it also confined contemporaneous feminists who were seeking to question the hegemonic relationship inherent in the proposed gender roles and family structures. Hence, we need to extend our own critical analysis beyond the narrow boundaries of the elite classes and the signifying language and material culture of “modernity.” We need to examine the roots from which the occupants of that class wish so eagerly to dissociate themselves: the peasantry. We have to bring class to bear on our subjects of study, and we need to do so at two levels. First, we have to link social and cultural history in ways that connect discursive signifiers to social relations. As Joan Scott notes, “Gender is a constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between the sexes, and gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power. Changes in the organization of social relationships always correspond to changes in representation of power, but the direction of change is not necessarily one way.”[17] Plainly put, we have to ask how narratives are related to tangible daily lives. To assume that words solely shape history is as unsatisfying as the notion that material forces are the only pertinent historical analytical criteria. Within the socioeconomic formation of a distinct middle class, we have clues as to how and why members of that class constructed and adopted particular notions of gender roles and family relations. In turn, these ideological premises define and shape class as a distinct social grouping along a hierarchical ladder.

Second, we need to introduce a vertical view of class into our analysis of the multilayered language of “modernity.” For the most part, scholars have generally looked at the discursive productions of the middle class and its own internal ideas of the “modern.” Yet, that language and its symbolism are not wholly contained within the boundaries of middle-class life. Some of that language—especially in opposition to the construction of private and public spheres—came from outside the experiences of that class. For example, as I will show later in this book, in Lebanon the language of feminism came from the recent historical memories of women working in the fields and silk factories and later of emigrant women working in the streets of the mahjar. These mental images stood in direct opposition to the middle-class notion of a fragile femininity which supposedly could not withstand the trials and tribulations of the world outside the confines of the “modern” house. Moreover, these images were critical not only as part of the feminist critique of bourgeois domesticity but also as an element of the daily lives of many middle-class women. Again, as we will see later on, in order to physically and intellectually transcend the boundaries of the “house,” these women continued to draw consciously and otherwise on memories of life and work in the field, factory, and street.

Exploring this link between peasant past and middle-class present is, therefore, not incidental but fundamental to the historical formation of “modernity.” Even when—and because—the literature and popular writing of the middle class submerged the connections to a peasant past, we as historians have to unearth that genealogy of identity. We need to do so in order to increase our understanding of particular histories, to give subaltern groups their due, and ultimately to dissipate the binding and hegemonic ideas of “modernity.”[18]

“Bound by Distance”[19]

For Lebanon, the argument above is even more compelling because of emigration. Most studies of “modernity” rightfully identify encounters with the “West” as part of the beginning of that historical process, but they tend to focus on individuals who travel beyond a particular “cultural space.”[20] However, in the case of Lebanon, it was not just a handful of people who traveled to the “West”; over a third of the population of the Mountain made this journey between 1890 and the onset of World War I. Through these large physical movements a new matrix of social relations was woven around multiple axes, the most prominent of which were sect, gender, family, and class.[21] It is not only sheer numbers that give a different dynamic to this process. The fact that the overwhelming majority of these emigrants were peasants makes the link between “modernity” and “tradition” all the more strong and relevant to the history of the middle class and its culture. Yet, this link between peasant emigration and the making of a middle class in Lebanon has never been explored.

It is not surprising that emigrants get cursory mention in the history of “nations.” As imagined communities seeking to establish concrete boundaries—which must appear longstanding within a “national” past and culture—“nations” cannot easily accommodate those who leave or enter their borders. Such movements question the very idea that culture is tied to a physical space from whence it emerges and without which it cannot exist. As people come and go, they disrupt this self-contented assumption by transporting and transforming cultures. Amidst these migrations, a “unique” national culture becomes untenable intellectually. Thus, narratives of “nations” have included emigrants and immigrants in a limited way: they are either going or coming but not both.

The difficulty in doing justice to the reality of the shuttling emigrant is evident in the tomes dedicated to the history of the United States—among others. As one scholar complained, “Historians of the United States find research on immigration most relevant when it addresses the Crèvecoeurian theme of making Americans.”[22] This motif stipulated that the “new man ... is an American who, leaving behind all ancient prejudices and manners, received new manners from the new mode of life he has embraced.”[23] Refined over time, with less emphasis on the crude and vacuous notion of the United States as a “melting pot,” this basic premise has nonetheless endured. It has even experienced a renaissance of late amidst the ongoing “culture debates,” with authors like Arthur Schlesinger arguing that within the cultural diversity there is still (and must be) an American essence, or “man” if you will.[24] With such an overly didactic view of Americanization, it becomes difficult to confront the fact that large numbers of financially successful emigrants rejected “America” as an idea and reality. But they did.

Noting that missing link, scholarship on “diaspora” has begun to call into question these nationalist claims to unique histories formed in culturally pristine spaces.[25] Paul Carter summarized the argument of this new body of literature: “It becomes more than ever urgent to develop a framework of thinking that makes the migrant central, not ancillary, to historical processes. We need to disarm the genealogical rhetoric of blood, property and frontiers and to substitute for it a lateral account of social relations, one that stresses the contingency of all definitions of self and the other.”[26] On a less theoretical level, there have been many calls within the field of immigration history to include the stories of return.[27] Heeding such calls are scholars like Donna Gabaccia and Dino Cinel, both of whom wrote about the return of southern Italian emigrants to their villages and towns.[28] Yet the writing of these stories remains difficult and stilted. One practical reason is that it is frustrating to retrace the footsteps of emigrants. Peasants—illiterate for the most part—left few records of their journeys or their thoughts on such matters. Additionally, most historians, trained as they are in a “national” field, can write easily of the point of departure or of entry, but rarely of both. This handicap limits the ability of most immigration historians to speak of the homes that peasants left and did not leave, let alone of those homes to which they went back after many intervening years.

More seriously, even those immigration historians who criticize the resurrection of the Crèvecoeurian myth cannot completely elude it as long as they operate within the boundaries of national history. For example, Gary Grestle has noted that one of the main contributions of the “new” social historians of immigration is their “discovery of return migration and sojourning.” Many southern and eastern European immigrants (“perhaps a majority,” according to Gabaccia) had no intention of staying in the United States.[29] Yet, in the next paragraph Grestle hastens to praise the “new” historians of Americanization for acknowledging that a “majority of the new immigrants stayed in America.”[30] In fact, and depending on the sources one chooses to believe, anywhere from 25 to 60 percent of all those who emigrated to the United States made a permanent return trip to their place of birth.[31] These percentages not only make Grestle's statement incorrect but require explanations that transcend “national” narratives.

Historians of Lebanon have been likewise blinded by the artificial borders of “national” history. Focused as most have been on events that took place in Mount Lebanon, these scholars appear to have barely noticed that over one third of the people left and many came back. For instance, in a volume that contained thirty-five articles about Lebanese emigration to various parts of the world, none addressed the experiences of return emigration. Only one article, by Kohei Hashimoto, spoke of the need to begin filling in this scholarly gap. He wrote, “While stress has been placed on Lebanon as a major population exporting region in the Middle East in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, another important reality was unintentionally set aside: the reality that Lebanon was also a receiver of population flow from the New Continent—in the form of Lebanese return migration.”[32] In addition, the sojourns of seven, eight, or twenty years by tens of thousands are glossed over because, from the chroniclers' perspective, a “national” culture can be “found” only in a bounded space. In other words, a unique identity, which was necessary to claim a place for Lebanon among the nations of the world, had to be drawn from the annals of events in the Mountain. Emigrants did not fit that formula. On the one hand, any study of their experiences in the mahjar would quickly reveal that there was no such thing as “Lebanon.” Conversations, debates, and arguments which took place in New York and Buenos Aires manifested the ambiguity and irrelevance—in many ways—of a “national” identity. Initially, family, village, and religion (in that order) provided the markings of peasants' communities. And it was only after years of residence in the mahjar that class, as defined through new gender roles and family structures, came to provide boundaries for a new communal identity. In comparison, the label of “Lebanese” developed only uncertainly and painfully over time.[33]

On the other hand, to take into account the experiences of emigrants and their influence on “Lebanese” society is to admit that culture is not derived from pure and localized volk “traditions.” Or, as James Clifford wrote, “if we rethink culture . . . in terms of travel, then the organic, naturalizing bias of the term culture—seen as a rooted body that grows, lives, dies, etc.—is questioned. Constructed and disputed historicities, sites of displacement, interference, and interaction, come more sharply into view.”[34] Maronite historians, who wrote in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, immortalized these “traditions” in stories about the “original” Maronites who refused to acquiesce to Arab “domination” and thus remained “pure.”[35] Later historians and folklorists only solidified this impression in the minds of the Maronite community and made it seem as “natural” as the rugged land surrounding them.[36] Countervailing historical narratives dismissed this specificity without rejecting its organic ties to a “land.” Instead, in these stories the land is expanded to subsume Lebanon within a greater Syria or a Pan-Arab “nation.” In all cases, local culture—be it Maronite, Syrian, or Arab—supposedly derived from the quintessential and faceless “masses.” Such claims leave no room for habits acquired by emigrants in Uruguay or “traditions” developed in Connecticut, even when these novelties are part of the identity of a “modern” Lebanon.

A Different View

Yet, without the history of emigrants, we are left with a sorely incomplete narrative about the making of “modern” Lebanon. We become trapped in essentializing narratives that cannot explain history except in bits and pieces and that simply mystify and mythologize the past. Thus, we find that most of the scholarship on nineteenth-century Lebanon reduces that period to the events of the year 1860, when Maronite peasants rose against their shuyukh (“feudal” landlords) in rejection of the iqta‘ (“feudal”) system.[37] At that historical moment, the ancien régime presumably passed into the folds of time and was replaced by a “modern” Lebanon. Without making light of the importance of this event, this approach is nonetheless problematic because it makes too simple and complete a leap between the pre-1860 and post-1860 periods.[38] Furthermore, the great bulk of this historical literature concludes its minimal investigation in the year 1860, without giving the slightest explanation as to how subsequent years were affected by events prior to 1860. Of greater relevance to this study is the fact that the majority of history books dealing with Lebanon are mute about the years between the 1860 civil war and World War I. Then, suddenly, historical narratives of modern Lebanon speak of a middle class that appears after World War I and that is—more important—considered profoundly critical to the “uniqueness” of the new nation. We are left with few explanations of what this “modernity” means or of how, when, and why it came to be in the first place. In other words, this narrative assumes an essential “nature” that is ahistorical and that is proposed as an innate characteristic of “Lebanon” and the “Lebanese.”

This dissatisfying and gaping analytical hole is generated in large part by an almost total absence of any serious historical consideration of gender, family, and class. Throughout the peasant revolts, radical economic shifts and tumbles, political changes, and social dislocation, the “family”—if seriously considered at all—remained unchanged in the view of these historians. The Lebanese peasant family at the end of the nineteenth century thus appears exactly the same as that of the eighteenth, seventeenth, and even sixteenth centuries. Gender has fared even worse. Except for Jacqueline des Villettes's study of the lives of peasant women within Lebanese patriarchal society, little else is to be found anywhere in the annals of Lebanese history.[39] Buried under the label of family, peasant women appear as simply a part of the family, a subunit of the clan structure. Since they are viewed mostly as happy matrons, no exploration is ever offered of peasant women as individuals, nor are the conflicts and unequal power relations within families apparent.[40] Not surprisingly, then, we cannot begin to understand how these tensions were central to the making of “modernity” in Lebanon.

As much as these matters have been neglected, I wish to make them central to my study. My narrative begins in 1861, soon after Lebanon's civil war had been “resolved” and the warring Maronite and Druze factions were separated in more than one way. In the succeeding decades the economy of the Mountain flourished (temporarily) because peasants, by increasing silk production, made large sums of money satisfying the needs of French industrialists (Chapter 2). Predictably enough, the subsequent trade which developed between Europe and the Mountain strengthened ties between the two regions. Primarily Christian peasants consciously reoriented their sericulture toward supplying Marseilles and Lyons because they saw profit. If they did not understand the long-term repercussions of their decisions, they were quite cognizant of the short-term financial advantages. The Maronite peasantry could have shunned the approaches of European mercantile capitalists. While a set of conditions did exist to facilitate the incorporation of Christian peasants into the world capitalist market, these do not negate the peasants' agency in the process. Explicitly, the strong links between the Maronite shuyukh and clergy on one hand and France on the other, the active and enthusiastic involvement of the Church with the silk trade, and the weakening of the hold of the Maronite shuyukh over their peasantry were important contributing factors in this process. But all were riddled with contradictory tendencies. For instance, the Maronite Church and shuyukh relationship with France was problematic, and it varied over time from friendly cooperation to outright hostility. And ultimately peasants were not totally obligated to sell to the French; they had some choice in the matter.

Affirming the agency of peasants in a process which linked the Mountain's economy with that of France is but one aspect of my argument. Another is how imperfect that process was. In other words, what Boutros Labaki paints as a seamless and linear trajectory into a “warped” economy was in reality far more of a jagged and interrupted path whose start and end are difficult to localize at one or two historical points.[41] European merchants suffered many financial setbacks in their dealings with local suppliers of silk. Peasants did not become mindless consumers who purchased whatever Europeans sold locally; rather their tastes dictated the success or failure of particular merchandise. And, most notably, peasant men succeeded in eluding the slide from farming into landless laboring through two strategies. Between 1861 and the 1890s, those men who were most in need of cash sent their daughters to work in the proliferating silk factories. In this manner they remained tied to the land—the source of their social identity and status—while securing additional money to ensure the survival of their families. A later strategy came into play after 1890, when the burgeoning population of the Mountain and stagnating silk prices made it increasingly difficult for peasants to make a decent living off the land. At that point the elevated expectations of peasants (and not their poverty) propelled many of them to leave the Mountain and to emigrate to the Americas (Chapter 3). In such a fashion they once again eluded the fate anticipated for them by Dependency theory and returned to form the nucleus of a new middle class. From this perspective, what Labaki characterizes as underdevelopment (the death of the industrial sector) looks more like the result of a successful resistance to the commodification of labor.

Complicating the narrative of these times even further were the historical ripples from women's work in silk factories and emigration. Both events placed unusual strain on the structure and hierarchy of the “family” and shed harsh and critical light on the contradictions inherent in that patriarchal edifice. When young women's “honor” was sacrificed to safeguard that of their fathers and when men abandoned their families to seek financial refuge beyond the village, the men were in essence reneging on their part of the patriarchal “contract.” The assumption that a woman would and should subsume her interests to that of a family led by a father or husband became less defensible when that man was no longer “protecting” her. Unhinged as men were by women's work in silk factories, the “timeless” premises on which the family was founded suffered even further in the mahjar. Stretched across thousands of miles, family relations became frayed and threatened to break. Furthermore, these peasants were rudely and suddenly yanked out of their small village world to face a dominant culture that was not particularly hospitable to their traditions and ways of life. Consciously and unconsciously, the emigrants had to explain—and even defend—who they were to the larger society as well to themselves (Chapter 4). Their financial success was dependent on their doing so to some extent. To enter the inner sanctum of American society, for example, was to come closer to the sources of wealth and economic power; but only those who did not appear “different” were allowed in.

Internally and externally this struggle went on and touched almost every aspect of the emigrants' lives. Their clothes, language and accent, food, and social habits became measures of their Otherness. Gender and family, more than anything else perhaps, became the site of contention over their cultural identity. Questions—practical and theoretical—arose about Lebanese women's work outside the home, about raising children, and about whether there should be any difference in the treatment of boys and girls. In public newspaper articles and private conversations emigrants argued over these matters, especially as they found themselves caught in the midst of the artificial construct of “East” and “West.” Were they of the “traditional” (read: backward) “East” or of the “modern West”? Were they on the side of science and enlightenment or that of superstitions and ignorance? Ridiculously reductionist as these questions may appear in retrospect, they were nonetheless compelling to many emigrants. Even those who refused to “assimilate” into American society or even accept what they regarded as a ludicrous dichotomy had to actively reject its values and demands. None were spared this onslaught on their sense of self.

This does not mean that the redefinition of individual and collective identities was controlled by the colonizing culture of the “West.” Nor does it imply that these questions were inflicted from outside the culture of the emigrants, even if the language with which these questions were articulated was unprecedented. Rather the encounter with an imperious society only gave greater prominence and immediacy to contradictions that were inherent within the culture of the emigrants. Specifically, there were tensions indigenous to the definition of gender and the relation-ship between family and clan. In the Mountain, these tensions were camouflaged under “tradition” and smothered by economic and social pressures external to the individual and family. In “Amirka” these mechanisms and ideologies became less effective, and the contradictions more glaringly volatile, particularly as emigrants had to endure benevolent and malevolent critiques of their “traditions” in the name of “modernity.”

Such questions were equally significant as they were carried back to the Mountain within the baggage of returning emigrants (Chapter 5). The emigrants' years in the “West” and all the material culture they had accumulated (clocks, clothes, and even a few cars) set them apart from those who had stayed behind in the Mountain. Thus, even as they rejected “America” to return “home,” these emigrants were nonetheless changed by their years in the mahjar. As Stuart Hall observed, “Migration is a one way trip. There is no 'home' to go back to.”[42] By design and inadvertently these differences created a social and cultural gap. Returning emigrants certainly were not interested in plowing the land as much as in owning larger tracts. Although most were illiterate—and perhaps it was because of that—they bought education for their sons and daughters. The old abode was no longer adequate given their sense of material comfort, nor was it an appropriate reflection of their social status. Bigger and more distinct dwellings were erected to announce their success. Even their clothes betrayed their metamorphosis from peasants into something else. Shorter and more expensive dresses, gold watches dangling from suit vests, and make-up signaled a shift in taste toward the “modern.”

The influx of these emigrants coincided with—and promoted—the emergence of a localized ideology of the “modern” within the new print media of Mount Lebanon. This ideology was being constructed in various arenas of the public life in Lebanon, such as education, political structure, democracy, and even the idea of a “nation.” However, the meaning of “modernity” was most vehemently debated as it pertained to gender. Newspapers and magazines dedicated part or all of their pages to subjects such as “modern” mothering and housekeeping, the education of girls, the role of women within Lebanese society, and “modern” marriage. The confluence of these two forces was responsible for the creation of a rural middle class in Lebanon, and the children of this new class became the urban middle class of the cities in later years. Yet, even as members of this new social group were erecting cultural and economic boundaries that distinguished them from peasants and the urban elite, internal voices attempted to dismantle those edifices (Chapter 6). In particular, feminists—a term that was not used by any of the women authors—questioned the public/private paradigm of “modern” middle-class life. They criticized that division and the imprisonment of women within a cult of domesticity. Their critique was based not only on the greater rights that women in the “West” were enjoying but on a “tradition” of women's labor. Women who would not have described themselves as politically active parlayed their designated roles as “mother” into forays into the public world, where they worked to safeguard the morals of society—a task which they accused men of abandoning. In these and other ways, class formation in the Mountain was fraught with dialectical tensions and was punctuated by twists and turns that made its outcome hardly predictable, let alone fixed.

Along every step of this road many peasants/emigrants/members of the middle class struggled to define their metamorphosis, and they succeeded at least some of the time. They did not simply duplicate the culture and society of the “West,” but they critically evaluated its elements, rejecting many while accepting some on their own terms whenever they could. Ultimately, the kaleidoscopic nature of this history makes rigid theoretical constructs like “modernization” and “Dependency” fall quite short of capturing the humanity of the people involved. And it is these multihued colors that my narrative is meant to display—albeit in a necessarily limited range. In the coming pages I venture to tell that history by following in the footsteps of peasants from the village to the factory, across the oceans and back. I write their stories as integral to the making of a new middle class and to the making of “modern” Lebanon.

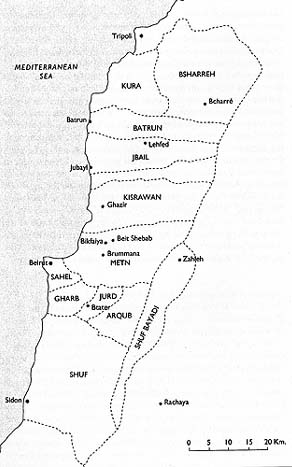

Given this purpose, I have tried whenever possible to let the voices of the people who lived those times come through my narrative. Voices of peasants are not easy to discern as they left little in the way of written records. But in the case of emigrants we are more fortunate. In this regard, the Alexa Naff Arab American Collection at the Smithsonian Museum of American History provided me with rich oral histories told by emigrants and also with evocative photographs. Similarly, preserved Arabic newspapers—published in the United States between 1890 and the onset of World War I—allowed me to hear some of the arguments and discussions that were part of the lives of emigrants. One must be aware, however, that for the most part these voices were of the emerging emigrant middle class and not of the community as a whole. Regrettably, I have not been privileged to gain similar access to the lives and thoughts of emigrants who went to Brazil and Argentina; those would have certainly enriched this work. My approach to collecting and using all this material has been to mix social, economic, and cultural history in a way that best captures the organic complexity of people's lives. In other words, the method to my theoretical “madness” is to avoid the assumption that any one particular analytical approach will suffice in explaining the web of decisions that make up the history of emigrants and their communities. Moreover, I have focused on the Christian communities in Lebanon for two reasons. First, and primarily, the greatest number of emigrants were drawn from these communities. Second, there is precious little information about the history of the Druze community save for one or two contemporary chronicles. Finally, I would like to note that I am using “Mountain,” “Mount Lebanon,” and “Lebanon” interchangeably. In all cases I am employing the noun to refer to the historical limits of the Mutasarrifiyya as shown in Map 1. I am not resorting to these terms as a “national” reference to the current geopolitical map of Lebanon. After all, this book is about the construction of that imagined community.

Map 1. Mount Lebanon, 1870-1921.

Notes

1. Smithsonian Museum of American History, Alexa Naff Arab American Collection, Series 4-c-c, interview with Michel Haddy, 1962.

2. The three main works on emigration from Mount Lebanon to the Americas are Elie Safa, L'Ēmigrationlibanaise (Beirut: Université Saint Joseph, 1960); Alexa Naff, Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985); and most recently Albert Hourani and Nadim Shehadi, eds., The Lebanese in the World: A Century of Emigration (London: Centre for Lebanese Studies and Tauris, 1992).

3. Mahjar means “land of emigration.” “Assimilation” of these emigrants into life in the United States is the focus of Naff's book Becoming American. Yet, that notion of simply abandoning who you are, leaving nary a trace of who you were on your “American” life, is not easily sustainable in the face of the cultural continuities so common among Lebanese Americans of that generation. This idea of assimilation has been attacked quite effectively by Robert E. Park and the Chicago sociologists in the 1920s and by Oscar Handlin, who dominated the field of immigration history in the 1940s and 1950s. In the 1960s and early 1970s scholars such as Rudolph Vecoli, Frank Thistlewaite, and Herbert G. Gutman, and later their students, continued to dismantle the mythology of the “melting pot.” Naff's notion that the emigrants from Mount Lebanon slipped into the “mainstream” without a struggle is untenable in the face of all the arguments and discussions that took place in the Arab media and in other public venues of discourse. She fails to note the struggles by these emigrants to retain a distinct identity and the coercive elements which forced them ultimately to give up so much of their distinctiveness. Nonetheless, one must not deny the valuable contribution of Naff's book, particularly as it was one of the first to document the experiences of early Arab Americans.

4. Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid, eds., Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 5.

5. See Women in the Metropolis: Gender and Modernity in Weimar Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997)—a collection of essays edited by Katharina von Ankum—for examples of the ambivalence with which many “middle-class” Germans approached the notion of “being modern.” On the one hand, such a state of being appeared as a sign of positive progress in life and universal history, particularly when juxtaposed with the “traditional” Other displayed in museum exhibits and written about in anthropological studies and magazine articles. On the other hand, this state of “modernity” brought along anxieties about the submersion of the individual within a mass culture that is progressively alienating.

6. A quick browse through the titles of monographs published in 1998 reveals at least one thousand containing the word modernity or postmodernity.

7. Paul Rabinow, French Modern: Norms and Forms of the Social Environment (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989), 9.

8. Clarissa Pollard, “Nurturing the Nation: The Family Politics of the 1919 Egyptian Revolution” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1997); Mona Russell, “Creating the New Woman: Consumerism, Education, and National Identity in Egypt, 1863–1922” (Ph.D. diss., Georgetown University, 1998); Beth Baron, The Women's Awakening in Egypt: Culture, Society, and the Press (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1994); Margot Badran, Feminists, Islam and Nation: Gender and the Making of Modern Egypt (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995); Afsaneh Najmabadi, The Story of the Daughters of Quchan: Gender and National Memory in Iranian History (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1998). Also see a collection of essays on “modernity” edited by Lila Abu-Lughod, Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998).

9. Abu-Lughod, Remaking Women, 9.

10. Joan Wallach Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” in Feminism and History, ed. Joah Wallach Scott (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 156–157.

11. See Judith Tucker, “The Fullness of Affection: Mothering in the Islamic Law of Ottoman Syria and Palestine,” in Women in the Ottoman Empire: Middle Eastern Women in the Early Modern Era, ed. Madeline C. Zilfi (New York: Brill, 1997), 232–252.

12. This formulation is part of some studies by European historians of the family. Within the work of Jack Goody, for instance, we find that the “Arab” family appears as a fixed extended family that does not change, and it is used to highlight the “significantly” different European nuclear family. Such juxtaposition is essential for the explanations that these historians employ for the rise of industrial capitalism in Europe and “nowhere else.” While most American and European historians have long abandoned the assumption that the nuclear family gave rise to the Industrial Revolution, or vice versa for that matter, the notion still lingers that the “extended” family is the norm for the Middle East. This assumption is based mostly on the absence of any real and recent studies of the history of the family in the area as well as on some early anthropological and ethnological work.

13. Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo, “The Uses and Abuses of Anthropology: Reflections on Feminism and Cross-Cultural Understanding,” Signs 5 (1980): 400.

14. Michel Foucault, Histoire de la sexualité (Paris: Gallimard, 1994–1997), and Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980).

15. Qasim Amin was one of the leading bourgeois advocates of the “modernization” of elite women's roles in family, society, and nation. He wrote the book Al-Mar’ah al-Jadidah (New woman) (Cairo: Sion, 1900) as an argument for changing gender roles and for providing women with greater educational opportunities that would better prepare them for those roles. I am borrowing the notion of “classic patriarchy” from Kandiyoti, who defines it as a system of gender roles based on unequal homosocial spheres, where women are subsumed within an extended family and where they do not exercise any direct control over resources and the decision-making process with regard to the world surrounding them. However, it must be added that within this system women had developed strategies that allowed them to maximize their control over the events surrounding them through informal—but nonetheless real and influential—means. Deniz Kandiyoti, “Islam and Patriarchy,” in Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender, ed. Nikki Keddie and Beth Baron (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991), 34.

16. See, for example, Marilyn Booth's “The Egyptian Lives of Jeanne D'Arc,” in Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East, ed. Lila Abu-Lughod (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998).

17. Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category,” 167.

18. I borrow this notion from Foucault, who wrote, “The purpose of history, guided by genealogy, is not to discover the roots of our identity but to commit itself to its dissipation.” Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1977), 162.

19. “Bound by distance” is the title of a most interesting reading of the history of Southern Italian emigration: Pasquale Verdicchio, Bound by Distance: Rethinking Nationalism through the Italian Diaspora (Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997).

20. Among the most famous of such travelers in the Middle East is Rifa‘a al-Tahtawi (1801–1873), who was sent by Muhammad ‘Ali, the governor of Egypt, on an educational mission to Paris. The observations of Paris and its people that he provided allowed his readers to encounter another culture on their own terms. Such an encounter was part of the process through which the middle classes began to express their consciousness of themselves vis-à-vis the “modern” world.

21. Another important axis was sectarianism. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, affliation with a religious sect came to play an increasingly important role in the identity of individuals and community. Thus, while being Druze or Maronite was mildly relevant to the daily lives of peasants in Lebanon during the eighteenth century, such identification took on heightened importance between 1800 and 1860 as a result of the confluence of Ottoman reforms, European colonial expansionism, and the political interests of local elites. As Makdisi makes poignantly clear in his writing on this subject, “sectarianism” was elevated to its paramount status by the European and Ottoman narratives which needed a timeless and “backward” identity to juxtapose with the supposed progressivism of a “modernity” in the making; Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). After the civil war of 1860 this juxtaposition continued to exist and was manipulated by Maronite thinkers who were intent on distancing themselves evermore from the other religious communities by drawing a sharp and ahistorical boundary between themselves and the “Others.” Thus they embraced “modernity” as that distinguishing characteristic. In the mahjar this constructed identity was elaborated even further by the writing of narratives of emigration which located the reasons for the movement of peasants in the oppression of the “Turk,” an archetype of “backwardness” and “barbarism”—ostensibly everything that the “West” was not. Furthermore, “modernity,” as it was being constructed in the mahjar and later in Lebanon on the return of the emigrants, was given a sectarian inflection which was meant only to perpetuate the mythology of distinctiveness between “Christian” and “Muslim” in Lebanon. Despite the intriguing and potentially illuminating aspect of this axis of study, I will regrettably not undertake it here because I wish to focus on gender and family.

22. Donna Gabaccia, “Liberty, Coercion and the Making of Immigration Historians,” Journal of American History 84, no. 2 (September 1997): 570–575.

23. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer (Duffeld: Chatto & Windus, 1908 [1782]), 43. This theme was taken up by many writers after de Crèvecoeur. For example, John Quincy Adams wrote in 1819 that immigrants “must cast off the European skin, never to resume it.” Quoted in Moses Rischin, ed., Immigration and the American Tradition (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1976), 47. Zangwill went further and invoked divine providence when he had his protagonist, David, exclaim in The Melting Pot, “America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and reforming! . . . God is making the American.” Israel Zangwill, The Melting Pot: A Drama in Four Parts (New York: Macmillan, 1909), 33.

24. Arthur Schlesinger Jr., The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society (New York: Norton, 1992), 13.

25. I have placed the term diaspora in quotes because I find it problematic. While many of those who write of “diasporas” argue that they are doing so because they seek to challenge isolated national histories, the term itself belies that attempt. It does so because it assumes a point of departure where culture is located and to which people must return if they are to retain that heritage. In other words, it localizes culture in a specific geographical area, thus allowing for an “organic” specificity that very much fits nationalist discourse. I have arrived at this conclusion after an illuminating lunch with my colleague David Gilmartin, who organized a conference on this topic as it pertains to South Asia.

26. Paul Carter, Living in a New Country: History, Traveling and Language (London: Faber & Faber, 1992), 7–8. Similar sentiments have been written in various essays and books such as Edward Said's “Reflections on Exile,” in Out There Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures, ed. Russell Ferguson, Martha Gever, Trinh T. Minh-ha, and Cornel West (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art; Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990). See also Ian Chambers, Migrancy, Culture and Identity (New York: Routledge, 1993); Stuart Hall, “Minimal Selves,” in Identity, the Real Me. Post-Modernism and the Question of Identity, ed. Lisa Appignanesi(London: ICA Documents, 1989).

27. Among the latest are several articles by Ewa Morawska, one of which was entitled “Return Migrations: Theoretical and Research Agendas,” in A Century of European Migrations, 1830–1930, ed. Rudolph Vecoli and Suzanne M. Sinke (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991).

28. Donna Gabaccia, Militants and Migrants: Rural Sicilians Become American Workers (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1988); Dino Cinel, The National Integration of Italian Return Migration, 1870–1929 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991). See also Katy Gardner, Global Migrants, Local Lives: Travel and Transformation in Rural Bangladesh (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

29. Gabaccia, “Liberty, Coercion and the Making of Immigration Historians,” 574. What is also striking in most immigration studies is their focus on European immigrants, when in fact there were many who came from Asia.

30. Gary Grestle, “Liberty, Coercion, and the Making of Americans,” Journal of American History 84, no. 2 (September 1997): 538–539. Of course, one cannot dismiss the focus on those who stayed out of hand; their stories are integral to the story of the United States. Yet, as some immigration historians have begun to argue, this history cannot be complete until it includes the stories of those who left alongside the stories of those who stayed. The numbers alone (ranging from 25 to 60 percent return migration) should compel us to question why these people left and to ponder how they saw “America.”

31. For some samples of these numbers, see Gabaccia, Militants and Migrants, 177–179. For Finland you can refer to Reino Kero, “The Return of Emigrants from America to Finland,” in University of Turku Institute of General History, Publications (Uppsala, 1972), 11–13. And some German statistics for the pre-1880 era can be found in Walter D. Kamphoefner, “The Volume and Composition of German-American Return Migration,” in A Century of European Migrations, 1830–1930, ed. Rudolph Vecoli and Suzanne M. Sinke (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 296–299.

32. Kohei Hashimoto, “Lebanese Population Movement, 1920–1939: Towards a Study,” in The Lebanese in the World: A Century of Emigration,ed. Albert Hourani and Nadim Shehadi (London: Centre for Lebanese Studies and Tauris, 1992), 65.

33. The idea of the “nation” as developed in the mahjar is a research subject that is very much in need of being pursued. Studies of Arab nationalism which focus solely on events and ideological currents in Syria, Lebanon, and the Ottoman Empire provide only a part of the picture because many of the nationalist debates took place in Brazil, Argentina, and the United States. There, the emigrant community was confronted with an identity connected to the mythical structure of the nation, a kind of identity they had not encountered before. This encounter obliged some of them to start defining a countervailing national identity. For example, Antoun Sa‘adeh lived in Brazil for a prolonged period of time. There he began to formulate his thoughts on “Greater Syria,” carrying on the work of a group of intellectuals who had preceded him and who lived in Paris. Pierre Gemayel, the head of the right-wing nationalist party, al-Kata’eb, was himself a product of the community of Lebanese who resided in Egypt.

34. James Clifford, “Traveling Cultures,” in Cultural Studies, ed. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula Treichler (New York: Routledge, 1992), 101.

35. Various Maronite historians have located that origin in different epochs and peoples. Early historians claimed that the “original Lebanese” were the marada, a “warlike” tribe that occupied the northern parts of Mount Lebanon. Later, more nuanced histories displace the marada as predecessors of the “History of Lebanon” and replace them with Maronites, who were allied with the marada in their opposition to “Arabs.” In all these cases, the end result remains the same: the Maronites were “different” from Arabs. This argument takes on a “modernity” twist with Paul Njeim, who in 1908, under the pseudonym Paul Jouplain, wrote a tract entitled La Question du Liban; etude d'histoire diplomatique & de droit international (Paris: Rousseau, 1908; reprint, Beirut: al-Ahliyah lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzī’, 1995). He appealed to the French “nation” to recognize Lebanon as separate from the “East” and as belonging spiritually and intellectually to the “West.” This myth has become an elemental part of the current Maronite identity and continues to surface—albeit much less frequently—in scholarly conferences and debates. For a superb study of Lebanese historians, see Ahmad Beydoun's Le Liban: Une histoire disputée—identité et temps dans l'historiographie libanaise contemporaine (Beirut: Publications de l'Université Libanaise, 1984). Also refer to Kamal Salibi's A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered (Berkeley: University of California Press, and London: Tauris, 1988).

36. Among the writers who contributed to this mythology were Lahad Khatir, Al-‘Adāt wal taqālid al-lubnaniyya (Beirut: Lahad Khater, 1977), and Anis Furayhah, Hadara fi tarīq al-zawāl: al-Qarya al-lubnaniyya (Beirut: n.p., 1957). The extremist views of later political groups like the Guardians of the Cedar, the Marada, and the Lebanese Forces owe much of their ideological fuel to interpretations of these exclusionist histories.

37. Most notable among the contemporary historians who have written about this period are I. ‘Aqiqi and Mikhail Mishaqa. By the 1950s local and foreign historians like the following wrote extensively on the subject of the 1860 peasant revolt in the Mountain: Asad Rustum, Lubnan fi ‘ahd al-Mutasarrifiyya (Beirut: Publications de l'Université Libanaise, 1954); Yehoshua Porath, “The Peasant Revolt of 1858–61 in Kisrawan,” Asian and African Studies (Jerusalem) 2 (1966): 37–78; Irina Smilianskaya, Al-Harakat al-fallahiyya fi Lubnan: al-Nisf al-awal mina al-qarn al-tasi‘ ‘ashar, tr. Adnan Jamous (Beirut: al-Farabi, 1978); Abdallah Hanna, al-Qadiyya al-zira‘iyyā wa al-harakat al-fallahīyya fi Suriyya wa Lubnan (1820–1920) (Beirut: al-Farabi, 1975). The latest in these histories is Leila Tarazi Fawaz's An Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, and London: Centre for Lebanese Studies and Tauris, 1994).

38. Samir Khalaf wrote of this problem in his book Persistence and Change in 19th Century Lebanon (Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1979).

39. Jacqueline des Villettes, La Vie des femmes dans un village Maronite libanais: ‘Aynel-Kharoubé (Tunis: N. Bascone & S. Muscat, 1964).

40. See Khatir, Al-‘Adāt wal taqālid al-lubnaniyya, and Furayha, Hadara fi tarīq al-zawāl, for a sampling of this romanticized view of the woman as her husband's helper.

41. Boutros Labaki, La Soie dans l'economie du Mont Liban et dans son environnement arabe (1840-1914) (Beirut: Publications de l'Université Libanaise, 1979).

42. Hall, “Minimal Selves,” 44.

2. Factory Girls

You threaten the girls that work in our factories with excommunication because they are not separated enough from the boys, and yet you find yourself incapable of doing anything against one individual who is abusing your name, and marching with an army against the government of your country!!

– Bernard des Éssard, French consul general in Beirut, 1866

Thus, in 1866, did the French consul general sarcastically chide two Maronite clergymen about the church's lack of action against the political renegade Yusuf Karam.[1] To his mind, it was rather absurd for the church to worry about as “trivial” a matter as the distance between the bodies of workers in silk factories when there were far more “serious” matters at hand. What he failed—or chose not—to understand was that young women's work in the increasingly numerous silk factories presented a profound threat to the authority of the church over the “morals” of society in Mount Lebanon. Proximity of unrelated young men and women transgressed a central tenet of the gender politics in Mount Lebanon. When it occurred in one or two instances, it was a manageable scandal. But when thousands of women intermingled on a daily basis with strangers, the situation became a crisis of considerable proportions. Moreover, by entering into a new public space—created by steam-belching and foul-smelling factories—women were publicly undertaking atypical economic and societal roles within peasant families. Work in factories, then, not only threatened to create fitna (social upheaval) by making room for “uncontrolled” sexuality, but it also brought into question the very core of gender roles, themselves the cornerstone of patriarchal society.

This was but one of several consequences of the commercialization of sericulture, which came on the heels of sixty years of political turmoil in Mount Lebanon. Silk was also altering the meaning of class. While the society of Mount Lebanon had long been stratified into peasants and shuyukh, the boundaries between the two groups were articulated in patrilineal terms rather than financial ones. Put more simply, one was born into, and died within, a “strata.”[2] Money could purchase many things, but not social status; and the families on top made certain of that. Mashayikh like the Khazins, Abi-Lam‘as, and Jumblatts were quite jealous of any encroachment on their social privileges and distinctions by the undifferentiated ahali, or the peasants.[3] As one local chronicler put it, “In this country there is tremendous preservation of the rank of people according to custom, which does not disappear in poverty and cannot be obtained through wealth.”[4] While in reality some families did cross these boundaries, the process took many generations to complete, and thus this limited permeability was hidden underneath the cloak of time. Yet, in the new economic realities of the Mountain, these sacrosanct “traditions” suffered far more rapid transformations that could not be concealed or ignored. Some peasants made fortunes that allowed them to buy honorary titles, and many a shaykh suffered humiliating financial crises that crippled his ability to sustain the social rituals necessary for his rank. At the same time that money from silk was wreaking havoc on social divisions, silk factories were infusing “class” with more economic meanings and refined divisions. In this climate, the term factory girl came to identify the social and economic measures of a working class and to differentiate it from peasants and elites.

Profits from silk cocoons augmented this new definition of class by raising the material expectations of many peasants in the Mountain. It started with the greater demand by the textile mills of Lyons for silk and the higher prices they were willing to pay for it. Peasants in Lebanon obliged with a dramatic increase in the cultivation of mulberry to feed more and more hungry silkworms. Within this unpredictable market economy there were more possibilities to make fortunes within a relatively short period of time—as well as to become destitute. As one commentator wrote, “The inhabitants [of Mount Lebanon] live in ease or misery depending on whether the harvest [of silk cocoons] was good or bad.”[5] Good years meant more money to purchase goods (like coffee, rice, and sugar) that peasants rarely had before and that only the shuyukh were previously privileged to enjoy. While this was hardly unbridled consumerism, it still went beyond matters of survival to a quest for some modicum of luxury. Through this cycle peasants stepped further into the market economy, added more debts, and became more vulnerable to xthe changing fortunes of the silk market. And when it began to falter, the repercussions were large for a majority of peasants who had grown accustomed to a better life. Most prominent of these repercussions—as we will see in the next chapter—was emigration

Silk—or more accurately the interaction between the local peasant economy and European capitalism—was instrumental in unleashing a momentum for change that altered the meaning and form of gender, class, and the good life in Mount Lebanon. It is my aim in this chapter to make clear the nature and magnitude of these historical processes. I do so because these ruptures in the societal fabric of Mount Lebanon were critical factors in the history of emigration and in the making of the middle class.

Silk

To truly appreciate these transformations we need to look at the changing role of silk in the economy and lives of peasants.[6] Sericulture, or the raising of silkworms, had been a steady part of the Mountain's economy for many centuries. Yet, while the role it played was important, it was not overwhelmingly critical. A look at the finances of one peasant family—as reported by David Urquhart, a European sojourner—will help clarify this point. He noted that “their resources are, two hundred mulberry trees, which produce silk worth 500 piasters; and a vineyard of two hundred vine-stocks, which gives as much more. They make up the rest by labor in the fields, . . . [which] gives 800 piasters.”[7] Of the total 1,800 piasters that this family needed every year to survive, then, silk provided little over a quarter. This was not an isolated case by any means. Looking at the larger picture across the Mountain, we find that in the late 1790s silk provided only about 13.3 percent of the overall taxes, while olives, wheat, and grapes were providing more than that percentage.[8] In the 1840s these numbers had changed only slightly. Finally, we can evaluate this relative importance of silk by comparing the size of the land that mulberry trees occupied as opposed to wheat, olive, and grapevines. As late as the 1840s, this land did not exceed 10 percent of the total planted acreage in the Mountain, while wheat covered close to one third of the jlal (terraces) of the Mountain, and grapevines followed closely behind.[9]