7

The Spread of Commercial Winegrowing

Nicholas Longworth and the Cincinnati Region

The defrauded settlers at Gallipolis, the nameless Frenchman making wine at Marietta, Rapp's Germans at Economy, Dufour's Swiss at Vevay, and all the other earliest winemaking settlers along the banks of the Ohio, from Pittsburgh almost to the junction with the Mississippi, were vindicated at last by the success of Nicholas Longworth at Cincinnati. As the main highway from east to west during the period of early settlement, the Ohio had inevitably seen repeated trials of viticulture, suggested by the combination of southward-facing slopes and broad waters. Dufour, as early as 1801, had assured Congress that the Ohio would rival the Rhine; it has never done so, but it was the scene of the first considerable wine production in this country, flourishing around Cincinnati from the early 1830s till after the Civil War, and unashamedly flaunting the naive slogan "The Rhineland of America."[1] An account of what lay behind this too-ready formula is instructive as to the chances and changes of commercial winegrowing in the era when useful native varieties had been found but before effective controls against diseases had been discovered.

The first person to plant a vineyard on the site now occupied by Cincinnati, on the great double curve of the Ohio, was a Frenchman named Francis Menissier, a political refugee who had once sat in the French parlement . At the end of the eighteenth century he laid out a small vineyard of vinifera on a slope of the new town (now the corner of Main and Third).[2] There he had success enough—or claimed that he had—to petition Congress in 1806 for a grant of land for vine growing on

the strength of his experiments.[3] The petition was denied, but Menissier's example was not lost.

In 1804 a young man named Nicholas Longworth (1782-1863) arrived in Cincinnati from Newark, New Jersey, to make his fortune in this new and burgeoning town, soon to be a city.[4] Longworth had already discovered a consuming interest in horticulture, but he put that aside while he studied law and began a successful practice. He soon found himself doing even better in land than in the law, and in no very long time he was recognized as having the true Midas touch: property that he bought for a song became worth millions, and Longworth joined John Jacob Astor as one of the two largest taxpayers in the United States. Longworth was a little man, and eccentric in dress, speech, and manner. But he was also strong-willed and successful, so that he could afford to do as he wished. By 1828 he was able to quit a regular business life and devote himself to his horticultural interests. These were fairly wide—he helped to establish the scientific culture of the strawberry, for ex-ample-but his first and most enduring love was the grape.

His attention was caught by the work of the Swiss at Vevay, and as early as 1813 Longworth had begun to experiment with grape growing in a backyard way—this was even before the return of Dufour from his long European sojourn.[5] His first commercial beginnings, in 1823,[6] were with the grape grown at Vevay, that is, the Cape or Alexander, which Longworth set out on a four-acre vineyard in Delhi township under the care of a German named Amen or Ammen. Longworth had the idea—a good one—that by making a white rather than a red wine from the Alexander he might get an article superior to that which the Swiss were selling along the Ohio. What he got, according to his own recollection, was a tolerable imitation of madeira, a white wine that required amelioration with added sugar and fortification with brandy.[7]

That was not what he wanted. The next step—again, as in the case of so many other pioneers, we recapitulate in miniature the general history of vine growing in America—was to try European varieties. He planted these by the thousands, from all sources, over a period of thirty years, and did not publicly repudiate the possibility of using vinifera until 1849.[8] He saw, however, that the development of good native varieties was the most important job to be done. He never faltered in that conviction, and even after his success with the wines of the Catawba, he continued to offer a $500 reward for a variety that would surpass that grape for winemaking.[9] He received and made trial of native vines from all over the United States, but did not succeed in finding a new variety to eclipse the Catawba.

Longworth's primary object was the production of an attractive dry table wine from the native grape, both in the name of "temperance" (already a rallying-cry among the moralists of the United States) and because such wine is the necessary basis of any sound winemaking industry in any country. The American idea of wine was, in Longworth's judgment, thoroughly corrupt: the wine favored by a public without a native winegrowing tradition, and long accustomed to rum and

38

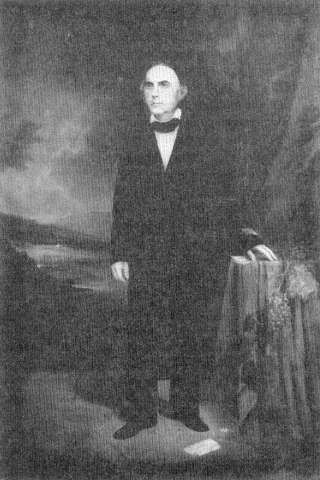

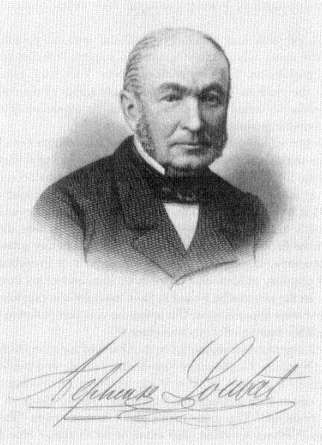

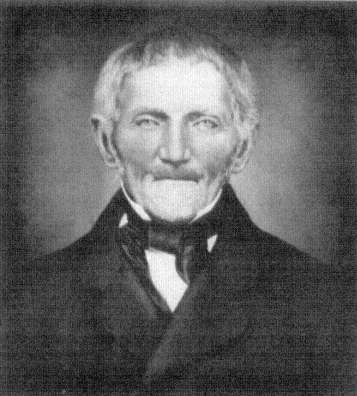

Nicholas Longworth (1782-1863), the man who made Cincinnati and the

banks of the Ohio the "Rhineland of America," at the height of his

reputation as the leading American winemaker. The Catawba grapes on

the table and the vineyards in the background are the emblems of

Longworth's achievement. (Portrait by Robert S. Duncanson, 1858;

Cincinnati Art Museum)

whiskey, generally contained 25 percent alcohol, and, Longworth added, "I have seen it contain forty percent."[10] After his unsatisfactory trials with the Alexander and with imported vinifera, Longworth got his chance when Major Adlum provided him with cuttings of the Catawba in 1825. Why Longworth should have been so slow to respond to this possibility I do not know: he must have known of the new grape as early as 1823, when Adlum began to publicize it. In any case, 1825 is the date of record.[11] Precisely when he got his first wines from the Catawba, is not clear. But by 1828, the year in which he retired to devote himself to wine-

growing, he was already well embarked on the plan with which he persisted through the rest of his life. Young Thomas Trollope, the brother of the novelist, who had accompanied his family to Cincinnati in 1828 on its hare-brained scheme for a frontier emporium selling exotic bijoux, made Longworth's acquaintance then and remembered him as "extremely willing to talk exclusively on schemes for the introduction of the vine into the Western States."[12] Young Trollope's mother, the redoubtable Frances, was quite unflattering about the wine of Cincinnati. A note to her Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832) provides what may be the first published judgment on Longworth's wines. It is not encouraging:

During my residence in America, I repeatedly tasted native wine from vineyards carefully cultivated, and on the fabrication of which a considerable degree of imported science had been bestowed; but the very best of it was miserable stuff. It should seem that Nature herself requires some centuries of schooling before she becomes perfectly accomplished in ministering to the luxuries of man, and, perhaps as there is no lack of sunshine, the champagne and Bordeaux of the Union may appear simultaneously with a Shakspeare, a Raphael, and a Mozart.[13]

The basis of Longworth's plan for viticulture was to make use of—or exploit—the labor of the German immigrants flowing into the Cincinnati region and giving it that German flavor that it still retains. When Trollope knew him, Longworth was employing Germans to cultivate vineyards on his own estate at a wage of a shilling a day (Trollope's figure) and food—a peonage advantageous to Longworth and perhaps tolerable to the new immigrants.[14] The Germans were in fact doubly necessary: they not only grew and made the wine, they drank it as well. The dry white catawba that Longworth succeeded in making was unappreciated by Americans used to sweeter and more potent confections; Longworth used to tell about how even the choicest Rheingaus were mistaken by American tasters for cider or even vinegar. The Germans, however, were better instructed, and for many years, Longworth wrote, "all the wine made at my vineyards, has been sold at our German coffee-houses, and drank in our city."[15]

Like all American winegrowers before him and afterwards, Longworth was troubled by the tendency of Americans to prefer wines with European names to those that were honestly, but too adventurously, given names that meant nothing to an uninstructed consumer: "catawba" was dubious at best; "hock" meant familiarity and security. So, at some time in the 1830s, he wickedly put counterfeit labels on his bottles of catawba: Ganz Vorzuglicher (Entirely Superior); Berg Tusculum (Mount Tusculum, after the actual name of one of his vineyard sites); and Versichert (Guaranteed).[16] He did not actually put these labels on the market, but they helped to make his point—still a familiar one—that there were many who could not abide native wine under its own label but who acclaimed it under a foreign one.

Longworth continued, as he had begun, with his system of using German labor, though the terms became more liberal than those described by Trollope in 1828. Typically, Longworth sought to settle a German Weinbauer on a small

39

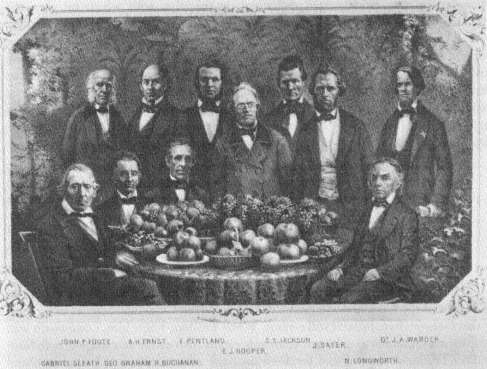

Members of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society, founded in 1843. At least three of these men—

Dr. J. A. Warder, Robert Buchanan, and Nicholas Longworth—were leading wine-growers in

Cincinnati. Note the grapes prominent among the fruits displayed on the table. (Cincinnati

Historical Society)

patch—four acres at most—and to leave him to himself to plant and cultivate. When a crop came in, Longworth would buy the grapes or the must or the vane, and split the profits with his tenant.[17] As the business developed, more and more of the processing went on under Longworth's own control, but the growing continued to be the business of the Germans, who had, as he said, been "bred from their infancy to the cultivation of the vine."

Longworth's earliest public account of his work in winegrowing appears to be an essay he contributed to a local compendium of agricultural advice published in Cincinnati in 1830, in which he urged that silk culture, the perennial rival of viticulture in the American dream, ought to be postponed in favor of the grape, and gave his own experience as his reason for thinking so.[18] In succeeding years the increasing number, frequency, and prominence of his contributions to the press on winegrowing provide an approximate measure of his growing success and recognition. His writings remained irregular and scattered, usually taking the form of letters addressed to particular topics, but they helped to make him the best-known and most frequently consulted expert on the subject of wine in his generation.

Longworth's scale of operations remained small through the 1830s; in 1833, for example, when he took the County Fair prize for his "pure Catawba," the produce of the nine scattered vineyards on which he had tenants was only fifty barrels, or about 3,000 gallons.[19] The development of viticulture in the ensuing ten years is witnessed by the establishment of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society in 1843; it at once took an interest in winegrowing, and made its first report on the subject in the year of its founding.[20]

The explosive expansion of the industry occurred after 1842, when Longworth, quite by accident, produced a sparkling catawba (as it was always called: never "champagne").[21] Even if he did not know how to make one, Longworth decided that a sparkling wine would be his means of opening a market beyond the Weinstuben of Cincinnati. After trying and failing to duplicate his first accidental success, he sent for a Frenchman in 1845. Unluckily, the poor man drowned in the Ohio before he could apply the secrets of his knowledge. Longworth found a successor, who commenced his work in 1847. Though the winemaker was French, Longworth was quite firm about his intent to develop a native wine. "I shall not attempt to imitate any of the sparkling wines of Europe," he wrote in 1849; instead, he aimed to provide "a pure article having the peculiar flavor of our native grape."[22]

By 1848 Longworth had built a 40' x 50' cellar expressly for the production and storage of sparkling catawba; by 1850 he was turning out 60,000 bottles a year and had plans for national distribution of his wine. This he began in 1852, by which year he had two cellars devoted to his sparkling wine, and a production of around 75,000 bottles.[23] The wine was made by the traditional méthode champenoise , in which, after a dose of sugar was added to the wine following its first fermentation, a second fermentation was carried out in the bottles, and the resulting sediment cleared by the tedious process of hand riddling. Losses from bottles bursting under the intense pressure of fermentation were sometimes catastrophically high: when 42,000 of 50,000 bottles were thus lost in a season, Longworth naturally wondered whether it was worth continuing.[24] Something, however, was saved from these losses by distilling the spilled wine into catawba brandy, as a brochure put out by Longworth's firm innocently admits.[25]

A third cellar manager, one Fournier, from Rheims, arrived in 1851 and did better.[26] The troubles and losses of the first years were rewarded; if Americans had been put off by the tart, dry taste of still catawba, they knew without instruction how to be pleased by bubbles. Suddenly, Cincinnati's winegrowers, and Longworth in particular, had a national winner, a widely advertised and widely enjoyed proof that the United States could produce an acceptable wine.

Longworth thoroughly understood the value of advertising. His letters to the press were progress reports on the promising development of his enterprise. He sent his wine to editors and to the competitions of horticultural and state agricultural societies: as early as 1846 he was exhibiting samples of catawba at the annual fair of the American Institute in New York City.[27] In common with a number of other Cincinnati producers, he sent samples of his wine to the Great Exhibition of

1851 in London, the original ancestor of and the model for all subsequent international exhibitions and fairs. The produce of native American grapes was, of course, powerfully strange to British palates; as the official Catalogue of the Exhibition politely remarked, "With many persons the taste for [catawba] is very soon acquired, with others it requires considerable time."[28] The publicity was bound to be helpful back in the United States. One of the great sensations of the Exhibition, the demurely naked Greek Slave of the American sculptor Hiram Powers, was the source of immense national pride in the United States when it was known that the British admired the piece. Powers, as it happened, was a Cincinnati boy whose first patron had been Longworth, another well-publicized fact that helped put Longworth in an attractive light—was he not domesticating both Bacchus and the Muses?[29]

Longworth also sent samples of his wine to eminent men as a way of promoting it. Powers, in Italy, was a useful agent in presenting catawba to politely interested Italians. Perhaps it was during his years in Italy that the poet Robert Browning heard of catawba wine. He knew of it, at any rate, for it is referred to in his curious poem "Mr. Sludge, the Medium" (1864).[30] Longworth made a lucky hit with the poet Longfellow, who responded to a gift of sparkling catawba with some hasty verses (injudiciously included in his collected poems) that have often been reprinted since. A very few lines are enough to show such merit as the poem possesses:

Very good in its way

Is the Verzenay

Or the Sillery soft and creamy;

But Catawba wine

Has a taste more divine,

More dulcet, delicious, and dreamy.

There grows no vine

By the haunted Rhine

By Danube or Guadalquivir,

Nor on island or cape

That bears such a grape

As grows by the Beautiful River.[31]

In 1855 Longworth was able to boast that he had sent a few cases of his wine to London, where it had been successfully sold in the regular way of trade.[32] By this time, Longworth, his large house called Belmont, on Pike Street, adorned with the work of Powers, and his vineyards on a hill (now part of Eden Park) had long beer established as premier attractions among the sights of Cincinnati, to be exhibited to all the many interested travellers who made their way to the Queen City of the Ohio before the Civil War.[33] Longworth was a national figure, celebrated for his wealth, his wine, and, most of all, for being a "character," shabbily dressed, la—conic, unpredictable, and—according to the press at any rate—prodigal of charity. The English journalist Charles Mackay, travelling through the United States as the correspondent of the Illustrated London News in 1858, will do to represent many

40

Longworth's vineyards recorded in 1858, perhaps more after the fashion of European models than as

unadorned documentary truth. The steamboat and the train represent American progress, but the style

of the vendangeurs and vendangeuses is distinctly Old World, as is the single-stake training of the vines,

like that practiced on the Moselle and the Rhine. (From Harper's Weekly . 24 July 1858)

others. Cincinnati did not impress him as quite so enlightened a place as its inhabitants liked to think; as they had been to Mrs. Trollope thirty years earlier, pigs were too much in evidence for Mackay's taste, those pigs that, barreled as pickled pork and shipped up and down the river, gave Cincinnati the name of Porkopolis and made it wealthy. Longworth and his wine moved Mackay's unreserved admiration, however; dry catawba, he reported to the English, was better than any hock, and sparkling catawba better than anything coming from Rheims. When prose seemed inadequate to his rapture, Mackay (a facile song writer) broke forth into verse:

Ohio's green hilltops

Grow bright in the sun

And yield us more treasure

Than Rhine or Garonne;

They give us Catawba,

The pure and the true,

As radiant as sunlight,

As soft as the dew.[34]

Not everyone was so well pleased by Cincinnati's wines: the native character of the Catawba, its labrusca foxiness, was a shock to any uninitiated taste, and some visitors were candid enough to say so. When the Englishwoman Isabella

41

A menu from the Gibson House, Cincinnati, dated 15 November 1856.

Sparkling Catawba from the local vineyards is listed on the same terms

as some distinguished grandes marques from Champagne; so, too,

among the "Hocks," one finds "Buchanan's Catawba" listed along

with Marcobrunner and Rudesheimer. (California State University,

Fresno, Library)

Trotter and her husband visited Cincinnati in 1858, almost at the same time as the well-disposed Mackay had been entertained there, they were regaled by their hosts with "most copious supplies of their beloved Catawba champagne, which we do not love, for it tastes, to our uninitiated palates, little better than cider. It was served in a large red punch-bowl of Bohemian glass in the form of Catawba cobbler, which I thought improved it."[35] To balance the record, one may quote a more enthusiastic description of catawba cobbler, provided by the Cincinnati wine-grower W. J. Flagg. The wine, he says, should be young, and sugar and ice added

to it help to temper the heat of an Ohio valley summer: "A cobbler of new wine, grown in the valley of the Ohio, or Missouri, where the Catawba ripens almost to blackness, drunk when the dog-star rages, lingers in memory for life."[36]

Longworth was always the leading name in Cincinnati winemaking, and sparkling catawba was always the glamorous item. But they could not have long stood alone, and in fact a supporting industry developed quickly. Longworth's part of the whole diminished in proportion as others set up and began to develop their vineyards and wineries. In 1848 there were 300 acres planted, of which 100 were Longworth's; in 1852, there were 1,200, distributed among nearly 300 proprietors and tenants. In 1859, perhaps the peak year in the history of Cincinnati wine-growing, some 2,000 acres produced 568,000 gallons of wine, putting Ohio at the head of the nation's wine production.[37] Almost all of this was white, and almost all from the Catawba, which was now indisputably confirmed as the grape of the region. But it did not quite exclude all its rivals. In 1854, at the New York Exhibition of that year, it was Longworth's sparkling Isabella that took the highest award among American wines.[38]

Among the early growers who followed Longworth into viticulture were Robert Buchanan, John Mottier, William Pesor, C.W. Elliott, A. H. Ernst, and a string of doctors: Stephen Mosher, Louis Rehfuss, and John Aston Warder, the last-named becoming later one of the country's most distinguished horticulturists. Not all of them were actual Cincinnatians; at least, not all of them confined their activity to Cincinnati proper. Dr. Mosher, for example, lived and grew his grapes on the Kentucky side of the river, as did others, including the actor Edwin Forrest.[39] Other vineyards in Ohio lay outside Hamilton County, in which Cincinnati stands; vineyards flourished in Brown and Clermont counties, and extended down the river well into Indiana at least in a minor way, and sometimes in more than a minor way. Clark County, Indiana, across the river from Louisville, had 200 acres of Catawba by 1850, and the calculations of the production along the Ohio included the grapes of Kentucky and Indiana as significant additions to those of the immediate Cincinnati region.[40]

Like Longworth, most of the Ohio River proprietors seem to have relied upon tenants, German by choice, to perform the labor in the vineyards (and then it was usually the woman rather than the man who did the work, as Longworth was fond of pointing out).[41] At this uncertain stage, only a man who had other resources could sustain the vicissitudes of such a pioneering enterprise. The actual wine-making was carried out on the tenanted properties in the early days, with predictably uneven results. As production rose, and the reputation of the wine began to be established, winemaking came increasingly under the control of commercial houses whose business it was to perform the vinification, storage, and distribution of the wine. By 1854 Longworth had two such houses; over his main cellars he had built a sort of barracks, four stories high, where poor laborers and their families might live. They showed their gratitude by frequently breaking into the wine vaults below and stealing their landlord's choicest wine, or so it was reported.[42]

42

A winery on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River, in the region of Cincinnati. The vintage

scene in this picture is described thus: "The grapes, when fully ripe, are gathered in baskets

containing about a bushel, as well as in a sort of 'pannier' of wood, made very light and strong,

and which is supported by straps or thongs of willow, on the back of the picker; . . . they are

brought from the vineyard in this manner and thrown upon the picking tables, where they are

carefully assorted." (Western Horticultural Review I [1850])

Other négociants , as the French would call them, were G. and P. Bogen, Zimmerman and Co. (associated with Longworth), Dr. Louis Rehfuss, and, in Latonia, Ken—tucky, the firm of Messrs. Corneau and Son at their Cornucopia Vineyard, some four miles south of Covington, across the river from Cincinnati. The figures for 1853, a good year, give some idea of the scale of production. The commercia! houses bottled 245,000 bottles of sparkling wine in that year, and 205,000 of stil wine, the value of the whole being estimated at $400,000 at prices ranging from $1.50 a bottle for the finest sparkling wine to 40 cents a gallon for the lowest quality table wine.[43]

The accounts of winemaking methods in Cincinnati show that the general practice in the 1850s was excellent. Longworth himself was emphatic about the necessity of making "natural" wines and confident of his ability to do so. He set a good example. Grapes were picked at full maturity, and all green or unsound berries were removed from the bunches by hand. The grapes were then stemmed

43

Michael Werk, an Alsatian who prospered by making soap and candles in Cincinnati,

joined the growing number of Cincinnati vineyardists in 1847. In less than a decade he

was taking prizes for his wines. Later, when disease threatened to extinguish the Cincinnati

vineyards, Werk developed large vineyards on the Lake Erie shore and then on Middle

Bass Island in Lake Erie. (Cozzens ' Wine Press , 20 August 1856; California State University,

Fresno, Library)

and crushed, and the juice fermented without the addition of sugar whenever possible. The French technique of rubbing the bunches over wooden grids in order to remove the stems was introduced by 1850.[44] The hydrometer was a standard tool, so that the winemaker knew whether he had sufficient sugar to insure a sound fermentation; if not, then the addition of sugar before fermentation was allowed. "allowed" by local agreement as to its utility, that is; we are talking about an in-

dustry in its Innocent Age, wholly unregulated and subject only to its own sweet will. Modern producers and dealers may try to imagine what that condition is like. The juice was fermented at low temperatures, under water seal, and quickly racked from its lees, without undue oxidation, and then stored in clean casks in cool cellars.[45] Modern technology could not prescribe better methods, so far as they went. One irregularity Longworth did, it was whispered, allow himself. He was convinced that Americans were partial to the "muscadine" flavor of rotundifolia grapes. In order to get it he bought large quantities of Scuppernong juice in the Pamlico and Albemarle regions of North Carolina and added that to flavor his Ohio catawba.[46] In the spring the wine may have undergone a malo-lactic fermentation, and then was ready for bottling. There was then, as there is now, some disagreement as to the proper length of aging for white wine. Longworth favored a long time in the wood, keeping his superior wines for four or five years. Others thought that a year in cask was enough: "There are many who think the Catawba wine is better at this period than ever afterwards" is how the writer in the U.S. Patent Office Report for 1850 puts it.[47]

Cincinnati wine may be said to have come of age at the beginning of the 1850s. The commercial wine houses, insuring the stability and distribution of the region's produce, were founded then. In 1851 the growers met in Cincinnati and organized the grandly named American Wine Growers' Association of Cincinnati. Its objects were to publish information useful to growers through its journal, the Western Horticultural Review , and to promote the interest of the industry generally, especially by insuring that only pure, natural wine was sent to the market.[48] The association sponsored a "Longworth Cup," awarded annually to the producer of that year's best catawba,[49] and was the first such organization concerned with wines and vines in this country that is entitled to be called an industry organization.[50]

At the Great Exhibition in London, to which, as has already been mentioned, the growers of Cincinnati made a respectable contribution, the official Catalogue explained that Cincinnati was now the "chief seat of wine manufacture in the United States" and that though yet in its infancy, the trade was "attracting much attention, and growing in importance in America."[51] In vindication of the claim, five producers besides Longworth exhibited specimens of catawba wine: Buchanan, Corneau and Son, Thomas H. Yeatman, C. A. Schumann, and H. Duhme. Yeatman, who took a prize for his wine in London, made visits to the vineyards and wine estates of France, Germany, and Switzerland in 1851 and 1852 in order to study European methods.[52] Longworth sent both catawba and unspecified "other wines" to the Exhibition—a reminder that he never ceased experimenting with alternatives to the Catawba grape in hopes of finding a variety without its defects. In the year following the Exhibition, Longworth began the promotion of his wine on a countrywide basis,[53] and with that event the wine of the Rhineland of America may be said to have arrived.

Cincinnati wine had only a very fragile tenure, however, more fragile than was yet recognized, though of course sensible men understood that the obstacles to be

44

The label of T. H. Yeatman, from he year in which his wine took a prize

at the Great Exhibition, London. (Western Horticultural Review 1 [1851])

surmounted were considerable. Robert Buchanan, for example, a successful Cincinnati merchant who began growing grapes in 1843, and who, with Longworth, was a founder of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society and a scientific student of viticulture and winemaking, took a modest view of what he and his fellows had accomplished. In his little Treatise on Grape Culture in Vineyards, in the Vicinity of Cincinnati (1850), the best practical handbook that had yet appeared on the subject in the United States, he wrote simply that "we have much to learn yet in the art of making wines."[54] But, as we have seen, the general principles of production at Cincinnati were in fact quite sound. The real—and soon fatal—weakness in the industry lay in the vine growing rather than in the winemaking. The Catawba did not always ripen well, and the average production was not very large; it seems to have run around one and a half tons per acre, though production as high as four tons was known, and ten was claimed.

Most ominous was the damage done by diseases, powdery mildew and black rot chief among them. In the first years of Catawba growing, these diseases were

45

Robert Buchanan's little book, first published anonymously, is one of the earliest and

best accounts of winegrowing around Cincinnati. Buchanan, a Cincinnati merchant,

had had a vineyard since 1843. His book, which went through seven editions in the

next ten years, was unlike any of its American predecessors in being based on the

practices of an established industry. No writer in this country before Buchanan had

had that advantage. (California State University, Fresno, Library)

only a minor problem in the Cincinnati region, so that the early confident assurances of the unchecked profits to be made by viticulture seemed perfectly justified. But the growth of planting and the passage of years saw mildew and black rot increasingly more frequent, as they had a homogeneous and extensive population of grapes to work upon. The record of each successive year's vintage, so far as this can be reconstructed, shows alarming ups and downs according to the lightness or the heaviness with which the infestations, especially black rot, struck the vineyards in a given year.[55] Even before 1850 black rot and mildew were evident, and the growers were unable to take any action against them. The fungous character of the rot was not generally understood—some attributed the disease to worms, some to cultivating methods, others to the atmosphere or to a wrongly chosen soil[56] —and so when the Catawba, a variety peculiarly susceptible, was touched by the blight, all that men could do was to resign themselves to their loss and speculate on the causes and cures.

Among the other diseases that attacked Ohio grapes, powdery mildew was the most important after black rot. This disease, native to the United States, first attracted serious attention not in its native place but after it had been exported to the Old World. In the 1850s Madeira saw its vines, upon which nearly the whole population depended, ravaged by powdery mildew (generally called oidium in Europe). The people of the island, driven to starvation, were forced to abandon their homes and to emigrate in large numbers. The island's wine trade has never fully recovered from the catastrophe—made more bitter still by the fact that it came from the country where Madeira's wines were held in esteem beyond all others. But Madeira was only the worst-afflicted among many: Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy suffered too. In Italy, the appearance of the disease coincided with that of the first railroads. Peasants, putting these things together, blocked new construction and tore up miles of rails already laid in order to fight the disease.[57]

The control of powdery mildew by sulfur dusting was now successfully tested and developed in Europe, but it did little for the growers of Cincinnati. Native vines, unlike vinifera, are sometimes injured by sulfur, so the cure in this case might not have been much preferable to the disease. Against black rot, even the most perfect application of sulfur would have had no effect. For that disease the effective treatment is a compound of copper sulphate and lime called bordeaux mixture, and that was not developed until 1885, much too late to be of use to the growers of Cincinnati.

Throughout the 1850s rot and mildew were increasingly present in the vineyards of Cincinnati. In that decade, only three good years—1853, 1858, and 1859—were granted to the growers by weather conditions inhibiting the rot.[58] By the end of the decade it was clear that the very existence of the industry was now problematical, for who could endure such helplessness and such uncertainty? Some efforts were made to introduce different and more resistant varieties—the Delaware, for example, seemed at one time to promise a better basis for viticulture, but it did not fulfill the promise. Ives' Seedling, a local introduction that had gained the premium

offered by Longworth's Wine House for the "best wine grape for the United States," also had some vogue, but was not good enough for wine or resistant enough to disease to provide a new basis for the trade.[59] The outbreak of the Civil War reinforced and accelerated the process begun by diseases. Though shortages brought high prices for wine, the vineyards were neglected, and new plantings ceased. A visitor to Cincinnati in 1867 reported that "the wine culture" was "somewhat out of favor at present among the farmers of Ohio."[60] By 1870 the vineyards, though still occupying a substantial acreage, were largely moribund. In that year, the brief flourishing of the Rhineland of America came to a symbolic close when Longworth's wine-bottling warehouse was taken over by an oil refinery.[61]

Longworth himself lived long enough to see the end coming, but refused to admit its certainty. As W.J. Flagg, his son-in-law and the manager of his wine business, wrote of Longworth at the end: "It was well enough he should pass away without knowing how nearly had failed the great work of his life. Among his last words before losing consciousness was an inquiry if [Flagg] had arrived: he wanted to tell him, he said, of a new vine he had found which would neither mildew nor rot. He never found it in this world."[62] The extinction of viticulture around Cincinnati was complete, and so powerful was the effect of the failure that even when, later, it became possible to control the diseases that had overwhelmed the vineyards, no one came forward to take the opportunity. Only in very recent years have tentative efforts been made to revive the industry there: more than a century has been needlessly lost in the interval.

Yet there had , after all, been a flourishing winemaking industry in Cincinnati: to show the possibility of such a thing was the historical importance of Longworth and his fellow growers. After many years of loss, Longworth had, before the end, even made money from winegrowing, and the possibility of doing so again waited only upon better cultivars and effective fungicides.

Meantime, the Cincinnati region had generated a sort of colonial extension of itself upon the shores and islands of Lake Erie, two hundred miles to the north. As early as 1830 a gentleman named H. O. Coit was growing vines and making wine in Cleveland, and he prophesied then that the shores of Lake Erie would someday be famous for their vineyards.[63] The success of viticulture along the Ohio River stimulated experiment with Catawba and other varieties along the lake shore in the 1830s. But it was not until late in the 1840s that anything like a commercial scale of viticulture was approached in this region. Northern Ohio had two centers of grape growing, from Cleveland eastward to the Pennsylvania border on one side of the state, and around Sandusky and the Lake Erie Islands on the other. It was in the second of these that winemaking particularly flourished. Here it was discovered that an ideal matching of variety and site had been stumbled upon: the limestone soil of lake shore and islands is classic grape-growing soil; the delayed springs and protracted autumns that the moderating effect of the lake brings to the islands just suited the Catawba; there, too, the diseases that destroyed the Catawba along the Ohio River did not pursue it with the same destructive effects. There has been an

46

Not all Ohio winegrowing was confined to Cincinnati or to the Lake Erie shores; this undated

(c, 1850) trade circular offers altar wine from Martin's Ferry in far southeastern Ohio, just across

the river from Wheeling, West Virginia. Noah Zane, the founder of Wheeling, is credited with

having introduced grape culture to the region. (California State University, Fresno, Library)

uninterrupted history of Catawba growing on Kelley's Island and the Bass Islands since the first vineyards were set out, a record of continuity unmatched in the erratic history of American viticulture.[64]

So long as the Cincinnati region prospered, development along Lake Erie was not notably rapid. The boom commenced as the Cincinnati industry declined: large plantings began just before 1860, and the years 1860-70 were remembered as the era of "grape fever."[65] Seven thousand acres had been planted by 1867, and though growth inevitably slowed, there were 33,000 acres in Ohio by 1889, most of it in the Lake Erie counties. The growers, as at Cincinnati, were largely Germans; indeed, some of them were Cincinnati Germans looking for alternatives to the disease-ridden banks of the Ohio.[66]

The Missouri Germans

Cincinnati had sent out its influences in another direction too—down the Ohio to the Mississippi, up that river to St. Louis, and thence upstream along the Missouri to the German settlement of Hermann. Winegrowing of one kind or another was already a venerable activity in the central Mississippi basin. We remember the Jesuits of Kaskaskia, the reputation of whose vineyards Dufour had heard of in Philadelphia before the end of the eighteenth century. The early dominance of the French in the Mississippi Valley meant that many experiments by small communities and by individuals of that vinophile race—clerical as well as lay—were certainly made with both native and imported grapes. In the 1770s the French settlers at Vincennes on the Wabash made red wine of native grapes for their own consumption that gained a good report.[67] Dufour recorded that vines were growing well in the gardens of St. Genevieve, Missouri, below St. Louis.[68] Cahokia, another old French settlement, also made wine before the coming of the British. But these were strictly domestic efforts. The statement is repeatedly made that the French government in the eighteenth century forbade viticulture in its American territories for fear of injury to the home industry.[69] I have not found proof of this; if it is true, it expresses a fear for which, so far as the record shows, there was very little ground in fact. In Missouri, as in Ohio, a winegrowing industry waited upon the appearance of the Germans.

The flow of German emigration that reached Cincinnati in the 1820s moved through and beyond it to St. Louis and the Missouri Valley in the next decade. A large part of it had been attracted there by the idealized, romantic description of the region published in 1829 by Gottfried Duden, a wealthy German who was convinced of the evils of overpopulation in the Old World and sought a new beginning in the American West.[70] He bought a farm along the Missouri River in Warren County in the new state of Missouri and wrote of the rich pastoral beauties of the land in order to draw new settlers. They came in large numbers, hastened along by the repressive politics of the reaction to the revolutionary outbreaks on the Conti-

nent in 1830. When they arrived, they found a wilderness not exactly like the smiling land of overflowing plenty that Duden had led them to expect, but neither did they fare badly. St. Louis and the lands along the Missouri for many miles to the west soon took on a distinctly German character.[71]

It was this fact that caught the attention of the directors of the Philadelphia Settlement Society (Deutsche Ansiedlungs-Gesellschaft zu Philadelphia ). This organization was formed in 1836 to carry out an ideal of German cultural nationalism by founding a colony in the remote West that should be German through and through in every particular.[72] The society sent an agent to the Missouri lands, and there, in the angle formed by the junction of the Gasconade and Missouri rivers, he bought some 11,000 acres for the society, which in turn sold the land to its stockholders. Settlement began in late 1837, and within two years Hermann, as the new town was called (after the German national hero Arminius who defeated the armies of Caesar Augustus), had a population of 450 souls: it was laid out with ambitious amplitude, its Market Street being deliberately made wider than Philadelphia's splendid Market Street by its visionary designers. They also included a "Weinstrasse" in the plan of the city's streets.[73] The difficulties of administering a frontier settlement from Philadelphia quickly led to a new arrangement, by which the Philadelphia Society's assets were transferred to the corporation of Hermann and the society dissolved. The aim of fostering a center of distinctively German culture was not abandoned. Hermann was substantially all German throughout the nineteenth century and was a center from which German settlement spread through east-central Missouri in Augusta, Washington, Morrison, and other towns.

The character of the immigrants was far higher than ordinary: most were men of education, and some were of high professional standing. Their distinction is crudely recognized in their local nickname of Lateinische Bauern —"Latin Peasants"—that is, farmers who could read the learned languages. Earlier, organized German settlements associated with winegrowing in this country were typically religious, on the model of the Pietists of Germantown in the time of William Penn, or of the Rappites in Indiana and Pennsylvania. The Hermannites, however, were thoroughly secular, inclining even, here and there, towards free thought. They cared more for literature, music, theater, and public festivals than for church. In Hermann, stores remained open on the Sabbath, and the early settlers did not trouble themselves to put up a church building, though they were quick to establish a theatrical society and to build a music hall.[74] It is perhaps no cause for wonder that a community so disposed should take to winegrowing and succeed at it as no one yet had succeeded.

The first settlers of Hermann had ventured west with the idea that they would become farmers on the wide prairies, but they found that the land their agent had bought was in broken, hilly, stony country, unfit for the agriculture they had in mind.[75] Viticulture was an experiment obviously worth trying, and though the long history of failure in this country was cause for skepticism, they had the current example of Longworth and his early successes as a hopeful sign to guide them.

47

The Poeschel Winery building, erected about 1850, near Hermann, Missouri, by the first

winemaker in the region. Even in the beginning the Germans built solidly. (From Charles

Van Ravenswaay, The Arts and Architecture of Germans in Missouri [1977])

Inevitably—almost as a ritual gesture it seems—some vinifera vines were tried before the end of the 1830s.[76] But the Hermannites were quick to accept the implication of Longworth's work and turned to the native varieties, using cuttings obtained from Cincinnati.[77] The first cultivated grape to produce at Hermann was an Isabella vine planted by Jacob Fugger that fruited in 1845. The first wine, from Isabella grapes, was made in 1846 by Michael Poeschel;[78] there were already 150,000 vines set out in Hermann then, and the economic promise was such that the town established a nursery for vines and offered land for vineyards on extravagantly easy terms.[79] The responses were immediate and strong: six hundred "wine lots" were snapped up, and by 1848 Hermann commenced its era of commercial winemaking with a modest but symbolically important production of 1,000 gallons of wine. The occasion was marked in good German style by a Weinfest that fall. The town cannon was fired in honor of Bacchus, and a steamboat-load of ladies and gentlemen from St. Louis came to join the festivities:[80] the rumor of wine spread instantly through that region, proof of the eagerness with which it was

hoped for. One of the St. Louis gentlemen, a lawyer named Alexander Kayser, was inspired to offer three premiums of $100 for the best specimens of Missouri wine, the first of which was gained in 1850 by a catawba of vintage 1849 from the vineyards of Hermann.[81]

Though the Isabella was the first variety to be used, it satisfied no one. Other varieties were soon tried: the first Catawba crop was produced in 1848; the Norton began to be cultivated around 1850, the Concord in 1855.[82] When mildew and rot began to devastate the Catawba vineyards, as they quickly did, the Germans along the Missouri, unlike their compatriots along the Ohio, had acceptable alternatives to turn to. The Concord, thanks to its tough, productive nature, was not long in occupying the largest share of the acreage in vines, but Hermann would never have established a reputation for wine if it had had only the Concord. The variety for quality was the Norton, a seedling grown by Dr. D. N. Norton, of Richmond, Virginia, before 1830. It had been tried without much enthusiasm in various places, including the vineyards of Cincinnati, where Longworth pronounced that it was good for nothing as a wine grape.[83] The growers at Hermann, however, could venture to disregard the great Longworth's judgment, for their need was desperate. Thus when a Herr Wiedersprecher brought Norton cuttings from Cincinnati, they gave them a trial. To Jacob Rommel belongs the honor of producing the first wine from Norton at Hermann.[84] Thus the Norton caught on in Missouri at a time when the Catawba crop had already been repeatedly damaged by the diseases to which it is vulnerable and the growers were casting about for something to take its place.[85]

A black grape, the Norton yields a dark and astringent wine without foxiness, capable of developing into a sound and well-balanced table wine. Yet the early practice at Hermann was apparently to ferment on the skins for only one or two days and thus to produce wine more pink than red.[86] This was reportedly done to avoid excess astringency. By 1867 the Missourians had learned enough about handling the Norton to please at least one discriminating critic. The philanthropist and writer Charles Loring Brace, reporting on his disappointment with the wines of California that he had sampled on a tour of that state, concluded that "no red wine has ever been produced in America equal to that made by the Germans of Missouri from [the Norton]."[87]

The prominence of the Norton at Hermann links the region with Virginia and the South rather than with Ohio and the northern tradition of white winemaking in the eastern United States. For white wine, the winemakers of Hermann also used a southern grape, the Lenoir. The Catawba persisted, too, but subject to the same wild ups and downs in annual yield, the effect of disease, that plagued the variety at Cincinnati.[88]

By 1855 Hermann was surrounded by 500 acres of vineyards and was producing enough beyond local demand to be able to send wine up the Ohio River to the wine houses of Cincinnati, where Missouri catawba was added to the wine of Cincinnati.[89] By 1861 the volume was great enough to justify the establishment of a large-scale winery at Hermann, built by Michael Poeschel, Hermann's first wine-

48

The Norton grape, originally found in Virginia, came into its own in the vineyards

of Missouri in the years just before the Civil War. It is that rare thing, a native grape

from which an acceptable red wine can be made. (Painting by C. L. Fleischman, 1867;

National Agricultural Library)

maker, and his partner, John Scherer.[90] This firm, which grew to be the largest winery outside of California, operated until Prohibition, and has, since 1965, been put back into the production of native wines.

The Civil War slowed agricultural development at Hermann, as it did along the Ohio. Nevertheless, the winegrowing industry continued a modest expansion. The Hermann vineyardists exhibited thirty-five varieties of grapes at the Gasconade County Fair in 1862—the only fair held in Missouri that year.[91] The war did brush the town, for the wine in George Husmann's cellar was all drunk by General Sterling Price's Confederates when they raided the town in October 1864. At the end of the war, Hermann had about a thousand acres of vines, more than

half of which were not yet in bearing. The preceding season had yielded 42,000 gallons of wine. And the demand for cuttings from the nurseries of Hermann exceeded their capacity: some two million went out that year. Winegrowing was now spread far beyond Hermann, touching almost every corner of the state, and moving into Illinois and Kansas, the states flanking Missouri on east and west. Augusta in nearby St. Charles County, another center of German settlement, was producing a significant quantity of wine in the 1860s[92] (after many years of dormancy, wine production has been resumed at Augusta). After the war, then, winemaking around Hermann was ready to enter on a steady prosperity that lasted down to Prohibition.

One may ask why Hermann, on river lands not much different from those around Cincinnati, should have succeeded in setting up an industry that long outlasted the one created by Longworth at about the same time? The most obvious, and perhaps most important, reason is that the Germans did not invest everything in the Catawba and so could survive its failure. They had tried other varieties with success that came before they could grow disheartened, as the Germans of Cincinnati had been disheartened. Another reason, less apparent, and much more difficult to demonstrate, lies in the character of the Missouri Germans. They were not tenant farmers but independent proprietors, prepared to take an experimental and scientific interest in viticulture. Perhaps it is significant that many of the pioneers were not Rhinelanders or South Germans like Rapp's Württembergers, but Hessians and Prussians, without experience of winegrowing in Europe. Hermann's first winemaker, Michael Poeschel, for example, was a north German who had no knowledge of grape culture; on the other hand, those who briefly and futilely tried vinifera at Hermann were Rhinelanders, another instance of Old World experience as a handicap in the new.[93]

As for the Missouri Germans' scientific disposition, that is shown in the work of developing new varieties and in the quantity of technical writing devoted to viticulture for which Missouri was remarkable in the nineteenth century. The philanthropic and literary farmer Friedrich Muench, of Washington, Warren County, a man trained to the Lutheran ministry in the University of Giessen and one of the original emigrants attracted by the blandishment of Gottfried Duden's description of the Missouri country, published the earliest treatise that I have found issuing from the Missouri German community.[94] His "Anleitung zum Weinbau in Nordamerika" ("Directions for Winegrowing in North America") appeared in the Mississippi Handelszeitung in 1859; a later version in book form appeared at St. Louis in 1864 as Amerikanische Weinbauschule ; this went through three editions, and was translated in 1865 as School jar American Grape Culture: Brief but Thorough and Practical Guide to the Laying Out of Vineyards, the Treatment of Vines, and the Production of Wine in North America . Muench, or "old Father Muench" as he grew to be called, had been growing grapes since 1846 and continued to do so until 1881, "when he was found dead among his beloved vines, one fine winter's morning of that year, with the pruning shears still in his hand, in his 84th year."[95] Something of Muench's high-minded style may be had from this passage in his School for American Grape Culture :

49

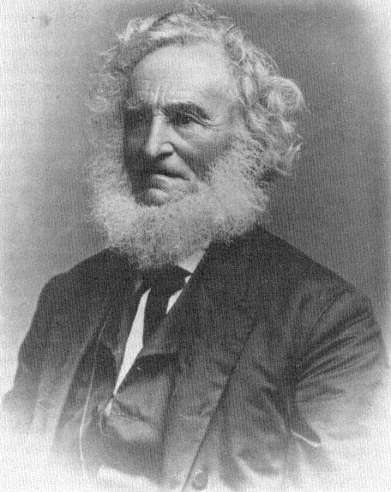

Friedrich Muench (1798?—1881), trained as a Lutheran minister in Germany, typified the

enthusiastic style of the German winegrowers of Missouri. "With the growth of the grape,"

he wrote, "every nation elevates itself to a higher degree of civilization." The winery he

founded in Augusta, Missouri, is in operation today. (State Historical Society of Missouri)

If it prove but moderately remunerative, the vine-dresser, free, lord of his own possessions, in daily intercourse with peaceful nature, is a happier and more contented man than thousands of those who, in our large cities, driven about by the thronging crowd, rarely attain true peace and serenity of mind. With the growth of the grape every nation elevates itself to a higher grade of civilization—brutality must vanish, and human nature progresses. (P. 11)

Before Muench's book appeared, another essay on viticulture was published at Hermann by a second and more important writer, George Husmann, whose An

50

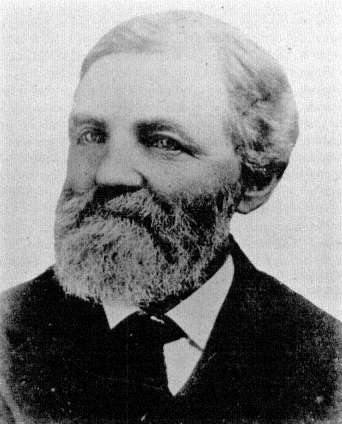

George Husmann (1827—1902), a pioneer winegrower at Hermann, Missouri,

was one of the most devoted proselytizers in the cause of the grape in the

nineteenth century. A viticulturist, winemaker, nurseryman, writer, and professor

of horticulture in Missouri, he ended his days as a winegrower in California's

Napa Valley. (State Historical Society of Missouri)

Essay on the Culture of the Grape in the Great West came out in 1863.[96] Husmann, whose father had been a shareholder in the society that founded Hermann, was a north German like Poeschel and Muench, not a Rhinelander.[97] He thus inherited no tradition of Old World winemaking, but had to learn his craft under native frontier conditions. His next publication was The Cultivation of the Native Grape, and Manufacture of American Wines , published in New York in 1866. This book, written as the Civil War was ending, is filled with a kind of visionary excitement over the prospects of a new viticulture in a newly united country, which may in part help to account for its success. In successive editions and under various new titles, it became one of the standard works on the subject, remaining in print well into this century.

The special emphasis of Husmann was on the power of the winemaker to control his work precisely. He explains the use of both the saccharometer and the

acidimeter, by which the winemaker can know exactly how much sugar and how much acid, the two key ingredients in the raw material of wine, he has to work with. Husmann is also frankly on the side of the winemakers who make no bones about adding sugar to a deficient juice and water to an over-acid juice. The object is to reach an ideal balance of sugar and acid; with the help of analytic instruments, Husmann argued, no winemaker need ever be at the mercy of a bad season. His instructions lean heavily on the work of the German chemist Dr. Ludwig Gall, whose "Practical Guide" had been translated in 1860 for publication in the U.S. Patent Office Report, the forerunner of the reports of the Department of Agriculture. There is no doubt that Husmann exaggerates the quality of the wine produced by his methods; he was writing more as a chemist than as a traditional winemaker, and he did not go uncriticized. But, as he very sensibly maintained, since the eastern grower more often than not was compelled to work with fruit low in sugar and high in acid, the choice was simply between making a "natural" wine unfit to drink and an "artificial" wine that was quite palatable—and profitable.[98]

In 1869 Husmann founded a monthly journal called The Grape Culturist at St. Louis, the first to be devoted to the subject in this country. Though it expired in 1871, that it could have been born at all and then have survived for three years is some measure of the status of winegrowing in the Mississippi Valley. It was also evidence of the literary and technical culture of the Germans. The publisher of the magazine was Conrad Witter, a St. Louis German who advertised that he kept a "large assortment of books treating of the culture of grapes and manufacture of wines."[99] It is hard to imagine any other region in the United States at this date in which such a stock of books might have been offered in the hope of sale.

The Missouri Germans were soon at work developing new grapes for western conditions; indeed, they were among the very first in America to carry on sustained trials in grape breeding. Jacob Rommel, who was taken by his parents to Hermann in the year of its founding, began work with native seedlings around 1860 and produced a number of varieties that had some recognition in their day.[100] He was looking for vines that had hardiness against the continental winters of the Midwest, resistance to the endemic fungus diseases, and productiveness enough to be profitable, and he sought these qualities in a series of seedlings derived from a riparia-labrusca ancestor. One at least of Rommel's seedlings, the Elvira, a white grape yielding a neutral white wine favored for blending, is still grown commercially in eastern vineyards, mostly in New York and Missouri. In Canada it had a great success, and it was still the most widely grown variety in the vineyards of Ontario as late as 1979.[101] It is, or was, occasionally met with as a varietal, but more often anonymously as part of a sparkling wine blend. Nicholas Grein, called Papa Grein by the younger generation of Hermannites, also introduced a number of riparia-labrusca seedlings, the best known of which is the Missouri Riesling, still cultivated to some extent in the state of its origin (and often confused with Elvira).[102] It has a strong resistance to black rot for an American variety.

By far the most distinguished scientific contribution to viticultural knowledge

51

Dr. George Engelmann (1809—84) was the leading physician in St. Louis, and,

at the same time, a botanist of international distinction; Engelmann was the most

expert of American ampelographers in the nineteenth century. His career illustrates

the high achievement of the Missouri German community. (State Historical Society

of Missouri)

made by the Missouri German community came from Dr. George Engelmann (1809-84), an M.D. from the University of Würzburg whose passion was botany.[103] He came to the United States in 1832 as agent for his uncles, who wanted to find investments in the Mississippi Valley. Settling in St. Louis, he became the most sought-after physician in the city, yet still found time to keep up his original work in botany, to carry out observations in biology, meteorology, and geology, and to found the St. Louis Academy of Science. Only a fraction of his work was devoted to grapes, but that is nevertheless an important fraction. He published a number of

52

The 1875 edition of the catalogue of Bush & Son & Meissner; it later grew

to include a "grape grower's manual," was translated into French and Italian,

and was used as a textbook in American agricultural schools. (National

Library of Agriculture)

brief articles on the classification of native varieties, beginning with "Notes on the Grape Vines of Missouri" in 1860 and ending with an essay on "The True Grape Vines of the United States" in 1875. This appeared as part of the encyclopaedic and learned catalogue of Bush and Son and Meissner, a leading Missouri nursery founded in 1865 by Isidor Bush (not a Missouri German but a Prague-born Austrian).[104] The catalogue passed through numerous editions and was used rather as a text book than as a commercial list; it was even translated into French and Italian. Engelmann's description and classification of the native vines was the scientific standard for his time: on his death it could be said that "nearly all that we know

scientifically of our species and forms of Vitis is directly due to Dr. Engelmann's investigations."[105]

When Engelmann first came to the United States, he made his way to a settlement of Germans on the Illinois side of the Mississippi, about twenty miles east of St. Louis. Here he had some connections, and here he made his base of operations while he explored and botanized before settling down to his medical practice. This was the region of the old French settlements, where grape growing had long been familiar, so familiar that even the American settlers readily took it up. Gustave Koerner, another German immigrant, a friend of Engelmann's, and later a distinguished lawyer, and a friend and political supporter of Lincoln's, recalled what he, Engelmann, and their friends found as they travelled for the first time to Belleville in 1833. Stopping at a farm, they were pleased to find Isabella grapes growing on the trellised house; even better, the farmer offered them a drink of his wild grape wine. "It was really very good," Koerner remembered, though sweetened a bit by added sugar, "the American having no liking for wine unless it is sweet."[106] The Germans themselves, when a group of them settled around Belleville, began at once to grow vines, and long continued to do so. Years later Koerner remembered giving a visiting German poet, who had said disparaging things about American wines, some "old, well-seasoned Norton Virginia Seedling" from the vineyard of a neighbor:

He drank it with great gusto, remarking that it was a very fine wine; he supposed, he said, it was Burgundy. When I laughingly told him it was St. Clair County wine, he would hardly believe me. . . . I must do him the justice, however, of saying that good Norton has really the body of Burgundy, and can never be taken for Bordeaux.[107]

One of the most prominent men among the Belleville Germans was Theodore Hilgard, who had been a lawyer, judge, and man of letters in Zweibrucken and who, after emigrating to Illinois, produced a wine there that he fondly called "Hilgardsberger."[108] More important for this history, Hilgard's son, Eugene, became professor of agriculture at the University of California, director of the Experiment Stations, and dean of the College of Agriculture, positions in which he made contributions of the first importance to the winegrowing of California.[109] He is thus another claim to the historical importance of the Latin Peasants settled in the region of which St. Louis is the center.

St. Louis itself—including St. Louis County—with its layers of French and German history, has been a scene of winemaking since very early times, as these things are measured in American history. The first St. Louis wine on record was made for church use by the Jesuits of St. Stanislaus Seminary at Florissant, north of the city, in 1823; they later developed commercial production as well, and continued the business down to 1960.[110] The earliest purely commercial winery in St. Louis was the firm called the Missouri Wine Company, founded in 1853. It constructed underground cellars for storage (they still survive in downtown St. Louis) and went into business not only in Missouri wines but in wines from Ohio.[111] The

well-known Cincinnati vineyardist Robert Buchanan, for example, sold his vintages of 1855 and 1856 in bulk to the Missouri Wine Company.[112] So the traffic in wine between Missouri and Ohio was a two-way street; we have seen that Hermann sent some of its wine up the Ohio to Longworth in Cincinnati, while Buchanan was shipping downstream to St. Louis. The Missouri Wine Company was advertising its sparkling catawba in the St. Louis papers in 1857, and the probability is that this was Ohio wine. Another interesting, but indistinct, St. Louis enterprise was carried out by Isidor Bush's partner, Gustave Edward Meissner, who planted 600 acres of vines on Meissner's Island, below the city.[113] These may have been intended as a nursery planting; in any case, no wine production is recorded from Meissner's Island.

The main claim of St. Louis to a place in the history of wine in America rests with the American Wine Company, which took over the Missouri Wine Company in 1859 and, through many changes of fortune, persisted up to the early years of World War II. The president was a Chicago hotelkeeper and politician named Isaac Cook, who, despite the struggles of political faction in Illinois, still managed to take an interest in wine as both a connoisseur and a producer. In 1861 he left Chicago for St. Louis, and built up the American Wine Company to a leading place in the American trade.[114] The main stock in trade was called Cook's Imperial Champagne, a label still in use, though it has passed through various hands and been applied to wines of various origins in its more than a hundred years of currency. Under Cook, the American Wine Company bought vineyards in the Sandusky region of Ohio, and though the finishing of the wine was carried out in St. Louis (in the cellars originally built for the Missouri Wine Company), the history of the business belongs perhaps more to Ohio than to Missouri. The American Wine Company also dealt in such wines as Missouri catawba and Norton.

Missouri is the farthest western reach of winegrowing at this stage of American history (excluding for the moment California and the regions of Spanish-American cultivation in the Southwest). After recounting all the early trials and modest successes in Missouri we may glance briefly, by way of reminder, at the obstacles that the pioneers had to face, and that their successors still face. They cultivated a region at the heart of a continent, untempered by any great body of water. The winter cold there sweeps down from the arctic regions of Canada, or off the high mountains and high plains that form the western, windward, edge of the Missouri basin. Even the hardiest grapes may expect to be killed to the ground from time to time in the freezes that flow from these sources. Phylloxera is at home here. Not too far to the south and east is the home of Pierce's Disease. Mildews, both powdery and downy, are alternately favored by heat and by damp; black rot is always present. If the early growers had known all this, would they have ventured at all? In any case, they did not know, and they did venture. The reviving efforts to establish a significant viticulture in Missouri today have an honorable pioneer tradition behind them of successful struggle against very tough odds.

The Development of Winegrowing in New York State

New York presents four different viticultural regions, running from east to west across the state, whose development is roughly parallel to the westward movement of population. The first is around New York City, especially on Long Island; next is the Hudson Valley; then the Finger Lakes of the central part of the state; and last the so-called Chautauqua region, an extension into western New York of the shorelands along Lake Erie.

The gardeners of Long Island, having a large concentrated market just beyond their doorsteps in the city, were naturally interested in seeing if they could succeed in growing wine for it. Not surprisingly, one of the first was a Frenchman, a merchant named Alphonse Loubat, who came originally from the south of France. At a date unrecorded but probably in the 1820s, he set out a vineyard of some forty acres—a notably ambitious effort—at New Utrecht, as it was then known; it is now a part of the Brooklyn waterfront, where the idea of any growing crop is impossible to conceive. Loubat's vines were vinifera, as a Frenchman's would be. Black rot and powdery mildew descended upon him, and he set himself to struggle against them. In the process he is said to have invented the practice of bagging the clusters against their depredations. But at last he was compelled to admit that they were too much for human effort to overcome.[115]

Loubat left a permanent memorial in the shape of a curious little book with the same title as Dufour's, The American Vine-Dresser's Guide , and published just a year later than Dufour's, in 1827, in New York. The book, in French and English on facing pages, opens with a delightful dedication "To the Shade of Franklin"—"À L'Ombre de Franklin." The great man's ghost is invoked to "Protect my feeble essay" and to "protect my vine, and cause it so to thrive that I shall soon be able to pour forth upon thy tomb libations of perfumed Muscatel and generous Malmsey."[116] At the time that he published his Guide , Loubat seems to have had no suspicion at all that his vinifera were doomed, or that the failure of winegrowing in the United States was owing to anything but the inexplicable neglect of a splendid opportunity. The instruction conveyed in his Guide is without any reference to American conditions, and assumes that French practices can be taken over unaltered. He soon had reason to think otherwise, and in 1835 the enterprise that he strove to establish along the banks of the East River came to a rude end when the vineyard property was sold for building lots.[117]

Still, before the end, his work had attracted some attention. Longworth's early trials in Ohio of vinifera were made with vines that he got from Loubat.[118] Another Long Islander, Alden Spooner, the editor of the Brooklyn Long Island City Star and one of the leading citizens of that pastoral community, had watched Loubat's struggles with sympathetic interest, and around 1827 began, in imitation, to plant vinifera grapes in his Brooklyn vineyard, now a part of Prospect Park.[119] Unlike Loubat, however, Spooner soon concluded that the native vines were the only safe bet. He planted the Isabella grape instead, and with this he had success enough to

53

Alphonse Loubat, a New York merchant born in France, planted a large

vineyard of vinifera vines in Brooklyn in the 1820s and published a book,

in both French and English, called The American Vine-Dresser's Guide

(1827). Interesting chiefly as a late memorial to the futile belief that vinifera

would do well in the American East after two hundred years of unbroken

failure, it was, for some inexplicable reason, reprinted in 1872, when its views

had long been discredited. (From Loubat, The American Vine-Dresser's

Guide [New York, 1872])

lead him to publish a book (he commanded a press and a bookstore, as well as a newspaper). Spooner's The Cultivation of American Grape Fines and Making of Wine (1846) is a scissors-and-paste job, of the sort that journalists know so well how to do, but it preserves some authentic anecdotes and is useful evidence of the interest in grape growing around New York City at that time.

The most important by far of the early Long Island grape growers was William Robert Prince, the son, grandson, and great-grandson of nurserymen.[120] The Princes operated the elegantly named Linnaean Botanic Garden at Flushing, Long Island, where, among other horticultural specialities, they kept a large collec-

54

A member of the fourth generation of a family of Long Island nurserymen,

William Robert Prince (1795—1869) made a special study of the grape and

published the first comprehensive book on the subject in this country, A

Treatise on the Vine (1830). Prince introduced one of the most successful

of the early hybrids, the Isabella grape. (From U. P. Hedrick, Manual of

American Grape Growing [1924])

tion of grapes, both native and foreign, for sale: their catalogue for 1830 lists 513 varieties.[121] The youngest Prince, as his father had before him, took a special interest in viticulture and became one of the recognized experts on the subject in the first part of the century, writing frequently for the horticultural magazines and developing the section devoted to vines in his nursery catalogue into a substantial essay on the subject. In 1830 he published a separate work called A Treatise on the Vine , an ambitious and expansive discourse that undertakes, in the easy and inconsequent style of those prespecialized days, to provide a history of the vine from

Noah downwards, a description of two hundred and eighty varieties of grape, and instruction on the "establishment, culture, and management of vineyards." The work is dedicated to Henry Clay in recognition of his part in founding the Kentucky Vineyard Society many years before.

Compared to anything else on viticulture by American writers, the Treatise was a work of an entirely different and higher order—"the first good book on grapes," as Hedrick says.[122] Prince made a serious effort at straightening out the tangle of names used to identify native grapes, and, in his description of native varieties, organized a great deal of local historical information; his prominence as the proprietor of America's best-known nursery made it possible for him to obtain information that no one else could have. Prince promised to publish a second part of his Treatise , to include a "topographical account of all the known vineyards throughout the world, and including those of the United States";[123] for whatever reason, this never appeared, and we can only regret what would have been an unparalleled description of early nineteenth-century viticulture in the United States. He did, at least, print a list of his correspondents and sources, which includes some familiar names: Bolling, whose "Sketch" had been given to Prince; Thomas McCall of Georgia, "who has presented me with a detailed manuscript of his experiments and success in making wines"; and Herbemont, Eichelberger, and Spooner.[124]

Since Prince was able to grow vinifera vines successfully under nursery conditions, he was slow to give up faith in them. A large part of his book is devoted to foreign grapes, which he was confident would grow well in this country. He particularly recommended the Alicante. And no matter what the variety of vinifera, its failure, he thought, could in every case be explained by bad management.[125] An equally large part of Prince's Treatise is devoted to descriptions of some eighty native varieties, far and away the most comprehensive account of the subject that had yet appeared. His own experience showed him the need for improved American varieties, and he was himself one of the earliest of the country's hybridizers, though he does not seem to have introduced any grape of his own breeding. The variety with which Prince's name is associated is the Isabella, which his father obtained in 1816 from Colonel George Gibbs of Long Island, an amateur grower, and named after Gibbs's wife. The grape itself is of disputed origin, but it is generally supposed to be from South Carolina.[126] The Princes did not promote the Isabella at once, but, after Adlum's success in creating notoriety for the Catawba, they began to put forward the Isabella as a superior rival.[127] Unlike Adlum, William Robert Prince was under no illusion as to the value of his labrusca seedling compared to the standard vinifera; still, he wrote of the Isabella, "I have made wine from it of excellent quality, and which has met with the approbation of some of the most accurate judges in our country."[128]

Prince has little to say about mildew and black rot, the diseases that were the bane of native hybrids throughout the East; there is plenty of evidence that these afflictions plagued grape growers around New York when Prince was writing, but he gives them no particular emphasis in his discussion of grape culture. One no-

55

An advertisement for vines from the Croton Point Vineyards of Dr. Robert Underhill (1802-71).

Note the offer to send a vine dresser to take care of the vines "when they commence bearing."

After a generation of successful grape growing along the Hudson, Underhill was himself just

beginning to make wine for the New York City market. ( The Cultivator , December 1855)

table thing he does do, however, is to call attention to the efficacy of spraying with a mixture of lime and sulfur against mildew. He was the first to do so in this country.[129]

Long Island may be imagined in the early part of the nineteenth century as a rural spot where grape growing for ornament and home use was widespread—local patriotism favored the Isabella, which "soon became the cherished ornament and pride of every garden and door-yard."[130] There, Colonel Gibbs, from whose garden the Isabella came, amused himself with a vineyard, as did Colonel Spooner; there, poor Loubat struggled and failed to compel vinifera to grow on a commercial scale; and there the learned Prince poured out, through his catalogues and monographs, information to the country at large from his base in the Linnaean Botanic Garden. Grapes did grow in Brooklyn (and there are wineries there today; that is a different story). One should also mention the famous nursery and botanic garden founded on twenty sterile, rocky acres at the junction of Jamaica and Flat-bush Avenues in 1825 by the Belgian emigré André Parmentier. This quickly became a flourishing garden, complete with rustic observation tower. Parmentier collected and distributed an unprecedentedly comprehensive variety of imported and native plants, including grapes.[131] All of his grapes were, unluckily, imported, and so his work in that line was more enterprising than fruitful. Also unfulfilled was Parmentier's intention to publish an "Essay on the Cultivation of the Vine," left unfinished at his untimely death in 1830.[132] Long Island thus presented the spectacle of much hopeful activity, but did not get beyond the promise of interesting beginnings.