19—

Dead West:

Ecocide in Marlboro Country

Mike Davis

Was the Cold War the Earth's worst eco-disaster in the last ten thousand years? The time has come to weigh the environmental costs of the great "twilight struggle" and its attendant nuclear arms race. Until recently, most ecologists have underestimated the impact of warfare and arms production on natural history.[1] Yet there is implacable evidence that huge areas of Eurasia and North America, particularly the militarized deserts of Central Asia and the Great Basin, have become unfit for human habitation, perhaps for thousands of years, as a direct result of weapons testing (conventional, nuclear, and biological) by the Soviet Union, China, and the United States.

These "national sacrifice zones,"[2] now barely recognizable as parts of the biosphere, are also the homelands of indigenous cultures (Kazakh, Paiute, Shoshone, among others) whose peoples may have suffered irreparable genetic damage. Millions of others—soldiers, armament workers, and "downwind" civilians—have become the silent casualties of atomic plagues. If, at the end of the old superpower era, a global nuclear apocalypse was finally averted, it was only at the cost of these secret holocausts.[3]

Part One—

Portraits of Hell

Secret Holocausts

This hidden history has come unraveled most dramatically in the ex-Soviet Union where environmental and anti-nuclear activism, first stimulated by Chernobyl in 1986, emerged massively during the crisis of 1990–91. Grassroots protests by miners, schoolchildren, health-care workers and indigenous peoples forced official disclosures that confirmed the sensational accusations by earlier samizdat writers like Zhores Medvedev and Boris Komarov

(Ze'ev Wolfson). Izvestiya finally printed chilling accounts of the 1957 nuclear catastrophe in the secret military city of Chelyabinsk-40, as well as the poisoning of Lake Baikal by a military factory complex. Even the glacial wall of silence around radiation accidents at the Semipalatinsk "Polygon," the chief Soviet nuclear test range in Kazakhstan, began to melt.[4]

As a result, the (ex-)Soviet public now has a more ample and honest view than their American or British counterparts of the ecological and human costs of the Cold War. Indeed, the Russian Academy of Sciences has compiled an extraordinary map that shows environmental degradation of "irreparable, catastrophic proportions" in forty-five different areas, comprising no less than 3.3 percent of the surface area of the former USSR. Not surprisingly, much of the devastation is concentrated in those parts of the southern Urals and Central Asia that were the geographical core of the USSR's nuclear military-industrial complex.[5]

Veteran kremlinologists, in slightly uncomfortable green disguises, have fastened on these revelations to write scathing epitaphs for the USSR. According to Radio Liberty and Rand researcher D. J. Peterson, "the destruction of nature had come to serve as a solemn metaphor for the decline of a nation."[6] For Lord Carrington's ex-advisor Murray Feshbach, and his literary sidekick Al Friendly (ex-Newsweek bureau chief in Moscow), on the other hand, the relationship between ecological cataclysm and the disintegration of the USSR is more than metaphor: "When historians finally conduct an autopsy on the Soviet Union and Soviet Communism, they may reach the verdict of death by ecocide."[7]

Peterson's Troubled Lands and especially Feshbach and Friendly's Ecocide in the USSR have received spectacular publicity in the American media. Exploiting the new, uncensored wealth of Russian-language sources, they describe an environmental crisis of biblical proportions. The former Land of the Soviets is portrayed as a dystopia of polluted lakes, poisoned crops, toxic cities, and sick children. What Stalinist heavy industry and mindless cotton monoculture have not ruined, the Soviet military has managed to bomb or irradiate. For Peterson, this "ecological terrorism" is conclusive proof of the irrationality of a society lacking a market mechanism to properly "value" nature. Weighing the chances of any environmental cleanup, he holds out only the grim hope that economic collapse and radical de-industrialization may rid Russia and the Ukraine of their worst polluters.[8]

Pentagon eco-freaks Feshbach and Friendly are even more unsparing. Bolshevism, it seems, has been a deliberate conspiracy against Gaia, as well as against humanity. "Ecocide in the USSR stems from the force, not the failure, of utopian ambitions." It is the "ultimate expression of the Revolution's physical and spiritual brutality." With Old Testament righteousness, they repeat the opinion that "there is no worse ecological situation on the planet."[9]

Obviously Feshbach and Friendly have never been to Nevada or western Utah.[10] The environmental horrors of Chelyabinsk-40 and the Semipalatinsk Polygon have their eerie counterparts in the poisoned, terminal landscapes of Marlboro Country.

Misrach's Inferno

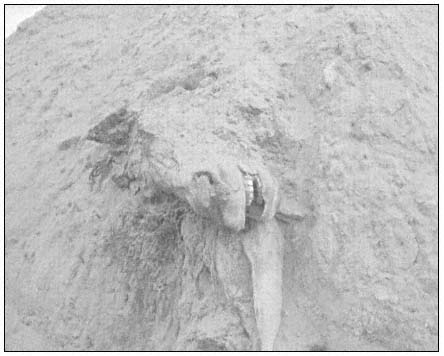

A horse head extrudes from a haphazardly bulldozed mass grave. A dead colt—its forelegs raised gracefully as in a gallop—lies in the embrace of its mother. Albino tumbleweed are strewn randomly atop a tangled pyramid of rotting cattle, sheep, horses, and wild mustangs. Bloated by decay, the whole cadaverous mass seems to be struggling to rise. A Minoan bull pokes its eyeless head from the sand. A weird, almost Jurassic skeleton—except for a hoof, it might be the remains of a pterosaur—is sprawled next to a rusty pool of unspeakable vileness. The desert reeks of putrefication.

Photographer Richard Misrach shot this sequence of 8 x 10 color photographs in 1985–87 at various dead-animal disposal sites located near reputed plutonium "hot spots" and military toxic dumps in Nevada (see fig. 19.1). As a short text explains, it is commonplace for local livestock to die mysteriously, or give birth to monstrous offspring. Ranchers are officially encouraged to dump the cadavers, no questions asked, in unmarked, county-run pits. Misrach originally heard of this "Boschlike" landscape from a Paiute poet. When he asked for directions, he was advised to drive into the desert and watch for flocks of crows. The carrion birds feast on the eyes of dead livestock.[11]

"The Pit" has been compared to Picasso's Guernica. It is certainly a nightmare reconfiguration of traditional cowboy clichés. The lush photographs are repellent, elegiac, and hypnotic at the same time. Indeed Misrach may have produced the single most disturbing image of the American West since ethnologist James Mooney countered Frederic Remington's popular paintings of heroic cavalry charges with stark photographs of the frozen corpses of Indian women and children slaughtered by the Seventh Cavalry's Hotchkiss guns at Wounded Knee in 1890.[12]

But this holocaust of beasts is only one installment ("canto VI") in a huge mural of forbidden visions called Desert Cantos. Misrach is a connoisseur of trespass who, since the late 1970s, has penetrated some of the most secretive spaces of the Pentagon Desert in California, Nevada, and Utah. Each of his fourteen completed cantos (the work is still in progress) builds drama around a "found metaphor" that dissolves the boundary between documentary and allegory. Invariably there is an unsettling tension between the violence of the images and the elegance of their composition.

The earliest cantos (his "desert noir" period?) were formal aesthetic experiments influenced by readings in various cabalistic sources. They are

Figure 19.1

Richard Misrach, Dead Animals #327, 1987.

Copyright Richard Misrach.

mysterious phantasmagorias detached from any explicit sociopolitical context: the desert on fire, a drowned gazebo in the Salton Sea, a palm being swallowed by a sinister sand dune, and so on.[13] By the mid-1980s, however, Misrach put aside Blake and Castaneda, and began to produce politically engaged exposés of the Cold War's impact upon the American West. Focusing on Nevada, where the military controls 4 million acres of land and 70 percent of the airspace, he was fascinated by the strange stories told by angry ranchers: "night raids . . . by Navy helicopters, laser-burned cows, the bombing of historic towns, and unbearable supersonic flights." With the help of two improbable anti-Pentagon activists, a small-town physician named Doc Bargen and a gritty bush pilot named Dick Holmes, Misrach spent eighteen months photographing a huge tract of public land in central Nevada that had been bombed, illegally and continuously, for almost forty years. To the Navy this landscape of almost incomprehensible devastation, sown with live ammo and unexploded warheads, is simply "Bravo 20." To Misrach, on the other hand, it is "the epicenter . . . the heart of the apocalypse":

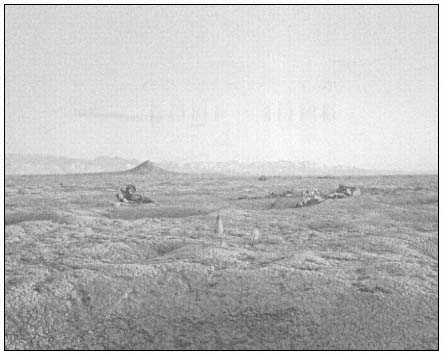

Figure 19.2

Richard Misrach, Bombs, Destroyed Vehicles, and Lone Rock , 1987.

Copyright Richard Misrach.

It was the most graphically ravaged environment I had ever seen. . . . I wandered for hours amongst the craters. There were thousands of them. Some were small, shallow pits the size of a bathtub, others were gargantuan excavations as large as a suburban two-car garage. Some were bone dry, with walls of "traumatized earth" splatterings, others were eerie pools of blood-red or emerald-green water. Some had crystallized into strange salt formations. Some were decorated with the remains of blown-up jeeps, tanks, and trucks.[14]

Although Misrach's photographs of the pulverized public domain, published in 1990, riveted national attention on the bombing of the West, it was a bittersweet achievement. His pilot friend Dick Holmes, whom he had photographed raising the American flag over a lunarized hill in a delicious parody on the Apollo astronauts, was killed in an inexplicable plane crash. The Bush administration, meanwhile, accelerated the modernization of bombing ranges in Nevada, Utah, and Idaho. Huge swathes of the remote West, including Bravo 20, have been updated into electronically scored, multi-target

Map 19.1

Pentagon Nevada.

grids which, from space, must look like a colossal Pentagon videogameboard.

In his most recent collection of cantos, Violent Legacies (which includes "The Pit"), Misrach offers a haunting, visual archeology of "Project W-47," the supersecret final assembly and flight testing of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The hangar that housed the Enola Gay still stands (indeed, a sign warns: "Use of deadly force authorized") amidst the ruins of Wendover Air Base in the Great Salt Desert of Utah. In the context of incipient genocide, the fossil flight-crew humor of 1945 is unnerving. Thus a fading slogan over the A-bomb assembly building reads BLOOD, SWEAT AND BEERS, While graffiti on the administrative headquarters commands EAT MY

FALLOUT. The rest of the base complex, including the atomic bomb storage bunkers and loading pits, has eroded into megalithic abstractions that evoke the ground-zero helter-skelter of J. G. Ballard's famous short story "The Terminal Beach." Outlined against ochre desert mountains (the Newfoundland Range, I believe), the forgotten architecture and casual detritus of the first nuclear war are almost beautiful.[15]

In cultivating a neo-pictorialist style, Misrach plays subtle tricks on the sublime. He can look Kurtz's Horror straight in the face and make a picture postcard of it. This attention to the aesthetics of murder infuriates some partisans of traditional black-and-white political documentarism, but it also explains Misrach's extraordinary popularity. He reveals the terrible, hypnotizing beauty of Nature in its death throes, of Landscape as Inferno. We have no choice but to look.

If there is little precedent for this in previous photography of the American West, it has a rich resonance in contemporary—especially Latin American—political fiction. Discussing the role of folk apocalypticism in the novels of García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes, Lois Zamora inadvertently supplies an apt characterization of Desert Cantos :

The literary devices of biblical apocalypse and magical realism coincide in their hyperbolic narration and in their surreal images of utter chaos and unutterable-perfection. And in both cases, [this] surrealism is not principally conceived for psychological effect, as in earlier European examples of the mode, but is instead grounded in social and political realities and is designed to communicate the writers' objections to those realities.[16]

Resurveying the West

Just as Marquez and Fuentes, then, have led us through the hallucinatory labyrinth of modern Latin American history, so Misrach has become an indefatigable tour guide to the Apocalyptic Kingdom that the Department of Defense has built in the desert West. His vision is singular, yet, at the same time, Desert Cantos claims charter membership in a broader movement of politicized western landscape photography that has made the destruction of nature its dominant theme.

Its separate detachments over the last fifteen years have included, first, the so-called New Topographics in the mid-1970s (Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams, and Joel Deal),[17] closely followed by the Rephotographic Survey Project (Mark Klett and colleagues),[18] and, then, in 1987, by the explicitly activist Atomic Photographers Guild (Robert Del Tredici, Carole Gallagher, Peter Goin, Patrick Nagatani, and twelve others).[19] If each of these moments has had its own artistic virtue (and pretension), they share a common framework of revisionist principles.

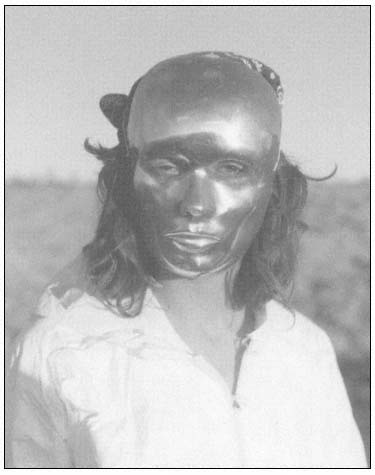

Figure 19.3

Richard Misrach, Princess of Plutonium,

Nuclear Test Site, Nevada, 1988.

Copyright Richard Misrach.

In the first place, they have mounted a frontal attack on the hegemony of Ansel Adams, the dead pope of the "Sierra Club school" of Nature-as-God photography. Adams, if necessary, doctored his negatives to remove any evidence of human presence from his apotheosized wilderness vistas.[20] The new generation has rudely deconstructed this myth of a virginal, if imperilled nature. They have rejected Adams's Manichean division between "sacred" and "profane" landscape, which "leaves the already altered and inhabited parts of our environment dangerously open to uncontrolled ex-

ploitation."[21] Their West, by contrast, is an irrevocably social landscape, transformed by militarism, urbanization, the interstate highway, epidemic vandalism, mass tourism, and the extractive industries' boom-and-bust cycles. Even in the "last wild places," the remote ranges and lost box canyons, the Pentagon's jets are always overhead.

Secondly, the new generation has created an alternative iconography around such characteristic, but previously spurned or "unphotographable" objects as industrial debris, rock graffiti, mutilated saguaros, bulldozer tracks, discarded girlie magazines, military shrapnel, and dead animals.[22] Like the surrealists, they have recognized the oracular and critical potencies of the commonplace, the discarded, and the ugly.[23] But as environmentalists, they also understand the fate of the rural West as the national dumping ground.

Finally, their projects derive historical authority from a shared benchmark: the photographic archive of the great nineteenth-century scientific and topographic surveys of the intermontane West. Indeed, most of them have acknowledged the centrality of "resurvey" as strategy or metaphor. The New Topographers, by their very name, declared an allegiance to the scientific detachment and geological clarity of Timothy O'Sullivan (famed photographer for Clarence King's 1870s survey of the Great Basin), as they turned their cameras on the suburban wastelands of the New West. The Rephotographers "animated" the dislocations from past to present by painstakingly assuming the exact camera stances of their predecessors and producing the same scene a hundred years later. Meanwhile, the Atomic Photographers, in emulation of the old scientific surveys, have produced increasingly precise studies of the landscape tectonics of nuclear testing.

Resurvey, of course, presumes a crisis of definition, and it is interesting to speculate why the new photography, in its struggle to capture the meaning of the postmodern West, has been so obsessed with nineteenth-century images and canons. It is not because, as might otherwise be imagined, Timothy O'Sullivan and his colleagues were able to see the West pristine and unspoiled. As Klett's "rephotographs" startlingly demonstrate, the grubby hands of manifest destiny were already all over the landscape by 1870. What was more important was the exceptional scientific and artistic integrity with which the surveys confronted landscapes that, as Jan Zita Grover suggests, were culturally "unreadable."[24]

The regions that today constitute the Pentagon's "national sacrifice zone" (the Great Basin of eastern California, Nevada, and western Utah) and its "plutonium periphery" (the Columbia-Snake Plateau, the Wyoming Basin and the Colorado Plateau) have few landscape analogues anywhere else on earth.[25] Early accounts of the intermontane West in the 1840s and 1850s (John Fremont, Sir Richard Burton, the Pacific railroad surveys) chipped away eclectically, with little success, at the towering popular abstraction of

"the Great American Desert." Nevada and Utah, for instance, were variously compared to Arabia, Turkestan, the Takla Makan, Timbuktu, Australia, and so on, but in reality, Victorian minds were travelling through an essentially extraterrestrial terrain, far outside their cultural experience.[26] (Perhaps literally so, since planetary geologists now study lunar and Martian landforms by analogy with strikingly similar landscapes in the Colorado and Columbia-Snake River plateaux.)[27]

The bold stance of the survey geologists, their artists and photographers, was to face this radical "Otherness" on its own terms.[28] Like Darwin in the Galapagos, John Wesley Powell and his colleagues (especially Clarence Dutton and the great Carl Grove Gilbert) eventually cast aside a trunkful of Victorian preconceptions in order to recognize novel forms and processes in nature. Thus Powell and Gilbert had to invent a new science, geomorphology, to explain the amazing landscape system of the Colorado Plateau where rivers were often "antecedent" to highlands and the "laccolithic" mountains were really impotent volcanoes. (Similarly, decades later, another quiet revolutionary in the survey tradition, Harlen Bretz, would jettison uniformitarian geological orthodoxy in order to show that cataclysmic ice-age floods were responsible for the strange "channeled scablands" carved into the lava of the Columbia Plateau.)[29]

If the surveys "brought the strange spires, majestic cliff facades, and fabulous canyons into the realm of scientific explanation," then (notes Gilbert's biographer), they "also gave them a critical aesthetic meaning" through the stunning photographs, drawings, and narratives that accompanied and expanded the technical reports.[30] Thus Timothy O'Sullivan (who with Mathew Brady had photographed the ranks of death at Gettysburg) abandoned the Ruskinian paradigms of nature representation to concentrate on naked, essential form in a way that presaged modernism. His "stark planes, the seemingly two-dimensional curtain walls, [had] no immediate parallel in the history of art and photography. . . . No one before had seen the wilderness in such abstract and architectural forms."[31] Similarly Clarence Dutton, "the genius loci of the Grand Canyon," created a new landscape language—also largely architectural, but sometimes phantasmagorical—to describe an unprecedented dialectics of rock, color and light. (Wallace Stegner says he "aestheticized geology"; perhaps, more accurately, he eroticized it.)[32]

But this convergence of science and sensibility (which has no real twentieth-century counterpart) also compelled a moral view of the environment as it was laid bare for exploitation. Setting a precedent which few of his modern descendants have had the guts to follow, Powell, the one-armed Civil War hero, laid out the political implications of the western surveys with exacting honesty in his famous 1877 Report on the Lands of the Arid Region. His message, which Stegner has called "revolutionary" (and others "socialistic"), was that the intermontane region's only salvation was Cooperativism based

on the communal management and conservation of scarce pasture and water resources. Capitalism pure and simple, Powell implied, would destroy the West.[33]

The surveys, then, were not just another episode in measuring the West for conquest and pillage; they were, rather, an autonomous moment in the history of American science when radical new perceptions temporarily created a pathway for a utopian alternative to the future that became Project W-47 and The Pit. That vantage point is now extinct. In reclaiming this tradition, contemporary photographers have elected to fashion their own clarity without the aid of the Victorian optimism that led Powell into the chasms of the Colorado. But "Resurvey," if a resonant slogan, is a diffuse mandate. For some it has meant little more than checking to see if the boulders have moved after a hundred years. For others, however, it has entailed perilous moral journeys deep into the interior landscapes of the Bomb.

Jellyfish Babies

If Richard Misrach has seen "the heart of the apocalypse" at Bravo 20, Carole Gallagher has spent a decade at "American Ground Zero" (the title of her new book) in Nevada and southwestern Utah photographing and collecting the stories of its victims.[34] She is one of the founders of the Atomic Photographers Guild, arguably the most important social-documentary collaboration since the 1930s, when Roy Stryker's Farm Security Administration Photography Unit brought together the awesome lenses of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee, and Arthur Rothstein. Just as the FSA photographers dramatized the plight of the rural poor during the Depression, so the Guild has endeavored to document the human and ecological costs of the nuclear arms race. Its accomplishments include Peter Goin's revelatory Nuclear Landscapes (photographed at test-sites in the American West and the Marshall Islands) and Robert Del Tredici's biting exposé of nuclear manufacture, At Work in the Fields of the Bomb.[35]

But it is Gallagher's work that proclaims the most explicit continuity with the FSA tradition, particularly with Dorothea Lange's classical black-and-white portraiture. Indeed, she prefaces her book with a meditation on a Lange motto and incorporates some haunting Lange photographs of St. George, Utah, in 1953. There is no doubt that American Ground Zero is intended to stand on the same shelf with such New Deal—era classics as An American Exodus, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and You Have Seen Their Faces.[36] Hers, however, is a more painful book.

In the early 1980s, Gallagher moved from New York City to St. George to work full-time on her oral history of the casualties of the American nuclear test program. Beginning with its first nuclear detonation in 1951, this small

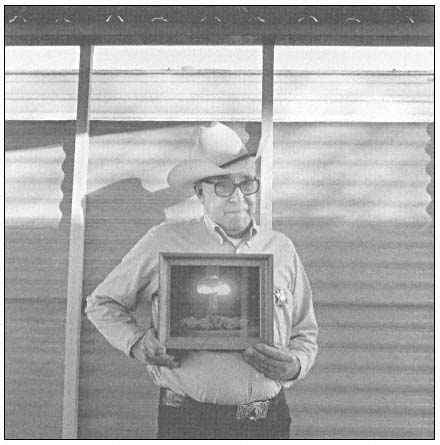

Figure 19.4

Carole Gallagher, Ken Case, the "Atomic Cowboy, " North Las Vegas.

Copyright Carole Gallagher.

Mormon city, due east of the Nevada Test Site, has been shrouded in radiation debris from scores of atmospheric and accidentally "ventilated" underground blasts. Each lethal cloud was the equivalent of billions of x-rays and contained more radiation than was released at Chernobyl in 1988. Moreover, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in the 1950s had deliberately planned for fallout to blow over the St. George region in order to avoid Las Vegas and Los Angeles. In the icy, Himmlerian jargon of a secret AEC memo unearthed by Gallagher, the targeted communities were "a low-use segment of the population."[37]

As a direct result, this downwind population (exposed to the fallout equivalent of perhaps fifty Hiroshimas) is being eaten away by cumulative cancers, neurological disorders, and genetic defects. Gallagher, for instance, talks

Map 19.2

Downwind.

about her quiet dread of going into the local K-Mart and "seeing four- and five-year-old children wearing wigs, deathly pale and obviously in chemotherapy."[38] But such horror has become routinized in a region where cancer is so densely clustered that virtually any resident can matter-of-factly rattle off long lists of tumorous or deceased friends and family. The eighty-some voices—former Nevada Test Site workers and "atomic GIs" as well as Downwinders—that comprise American Ground Zero are weary with the minutiae of pain and death.

In most of these individual stories there is one single moment of recognition that distills the terror and awe of the catastrophe that has enveloped their life. For example, two military veterans of shot Hood (a 74-kiloton hydrogen bomb detonated in July 1957) recall the vision of hell they encountered in the Nevada desert:

We'd only gone a short way when one of my men said, "Jesus Christ, look at that!" I looked where he was pointing, and what I saw horrified me. There were people in a stockade—a chain-link fence with barbed wire on top of it. Their hair was falling out and their skin seemed to be peeling off. They were wearing blue denim trousers but no shirts. . . .

I was happy, full of life before I saw that bomb, but then I understood evil and was never the same. . . . I seen how the world can end.[39]

For sheep ranchers it was the unsettling spectacle they watched season after season in their lambing sheds as irradiated ewes attempted to give birth: "Have you ever seen a five-legged lamb?"[40] For one husband, on the other hand, it was simply watching his wife wash her hair.

Four weeks after that [the atomic test] I was sittin' in the front room reading the paper and she'd gone into the bathroom to wash her hair. All at once she let out the most ungodly scream, and I run in there and there's about half her hair layin' in the washbasin! You can imagine a woman with beautiful, ravenblack hair, so black it would glint green in the sunlight just like a raven's wing, and it was long hair down onto her shoulders. There was half of it in the basin and she was as bald as old Yul Brynner.[41]

Perhaps most bone-chilling, even more than the anguished accounts of small children dying from leukemia, are the stories about the "jellyfish babies": irradiated fetuses that developed into grotesque hydatidiform moles.

I remember being worried because they said the cows would eat the hay and all this fallout had covered it and through the milk they would get radioactive iodine. . . . From four to about six months I kept a-wondering because I hadn't felt any kicks. . . . I hadn't progressed to the size of a normal pregnancy and the doctor gave me a sonogram. He couldn't see any form of a baby. . . . He did a D and C. My husband was there and he showed him what he had taken out of my uterus. There were little grapelike cysts. My husband said it looked like a bunch of peeled grapes.[42]

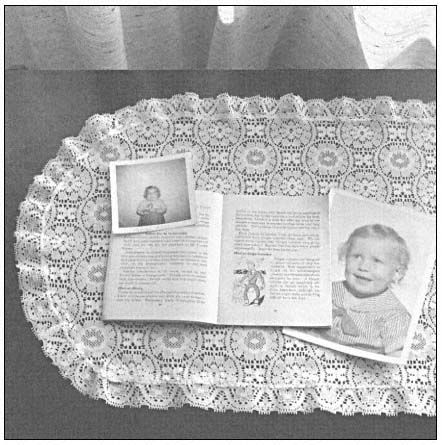

Figure 19.5

Carole Gallagher, Baby photographs of Sherry Millett, before

and during the leukemia from which she died, with the

1957 Atomic Energy Commission propaganda booklet.

Copyright Carole Gallagher.

The ordinary Americans who lived, and still live, these nightmares are rendered in great dignity in Gallagher's photographs. But she cannot suppress her frustration with the passivity of so many of the Mormon Downwinders. Their unquestioning submission to a Cold War government in Washington and an authoritarian church hierarchy in Salt Lake City disabled effective protest through the long decades of contamination. To the cynical atomocrats in the AEC, they were just gullible hicks in the sticks, suckers for soapy reassurances and idiot "the atom is your friend" propaganda films. As one subject recalled his Utah childhood: "I remember in school they showed a film once called A is for Atom, B is for the Bomb. I think most of us

who grew up in that period . . . [have now] added C is for Cancer. D is for Death. "[43]

Indeed, most of the people interviewed by Gallagher seem to have had a harder time coming to grips with government deception than with cancer. Ironically, Washington waged its secret nuclear war against the most patriotic cross-section of the population imaginable, a virtual Norman Rockwell tapestry of Americana: gung-ho Marines, ultra-loyal Test Site workers, Nevada cowboys and tungsten miners, Mormon farmers, and freckle-faced Utah schoolchildren. For forty years the Atomic Energy Commission and its successor, the Department of Energy, have lied about exposure levels, covered up Chernobyl-sized accidents, suppressed research on the contamination of the milk supply, ruined the reputation of dissident scientists, abducted hundreds of body parts from victims, and conducted a ruthless legal war to deny compensation to the Downwinders.[44] A 1980 congressional study accused the agencies of "fraud upon the court," but Gallagher uses a stronger word—"genocide"-and reminds us that "lack of vigilance and control of the weaponeers" has morally and economically "played a large role in bankrupting . . . not just one superpower but two."[45]

And what has been the ultimate cost? For decades the AEC cover-up prevented the accumulation of statistics or the initiation of research that might provide some minimal parameters. However, an unpublished report by a Carter administration task force (quoted by Philip Fradkin) determined that 170,000 people had been exposed to contamination within a 250-mile radius of the Nevada Test Site. In addition, roughly 250,000 servicemen, some of them cowering in trenches a few thousand yards from ground zero, took part in atomic war games in Nevada and the Marshall Islands during the 1950s and early 1960s. Together with the Test Site workforce, then, it is reasonable to estimate that at least 500,000 people were exposed to intense, short-range effects of nuclear detonation. (For comparison, this is the maximum figure quoted by students of the fallout effects from tests at the Semipalatinsk Polygon.)[46]

But these figures are barely suggestive of the real scale of nuclear toxicity. Another million Americans have worked in nuclear weapons plants since 1945, and some of these plants, especially the giant Hanford complex in Washington, have contaminated their environments with secret, deadly emissions, including radioactive iodine.[47] Most of the urban Midwest and Northeast, moreover, was downwind of the 1950s atmospheric tests, and storm fronts frequently dumped carcinogenic, radioisotope "hot spots" as far east as New York City. As the commander of the elite Air Force squadron responsible for monitoring the nuclear test clouds during the 1950S told Gallagher (he was suffering from cancer): "There isn't anybody in the United States who isn't a downwinder. . . . When we followed the clouds, we went all

over the United States from east to west. . . . Where are you going to draw the line?"[48]

Part Two—

Healing Global Wounds

Yet, over the last decade, Native Americans, ranchers, peace activists, Downwinders, and even members of the normally conservative Mormon establishment have attempted to draw a firm line against further weapons' testing, radiation poisoning, and ecocide in the deserts of Nevada and Utah. The three short field reports that follow (written in 1992, 1993, and 1996–97) are snapshots of the most extraordinary social movement to emerge in the postwar West.

Humbling "Mighty Uncle"

Flash back to fall 1992. The (private) Wackenhut guards at the main gate of the Nevada Nuclear Test Site (NTS) nervously adjust the visors on their riot helmets and fidget with their batons. One block away, just beyond the permanent traffic sign that warns "Watch for Demonstrators!" a thousand anti-nuclear protestors, tie-dyed banners unfurled, are approaching at a funeral pace to the sombre beat of a drum.

The unlikely leader of this youthful army is a rugged-looking rancher from the Ruby Mountains named Raymond Yowell. With a barrel chest that strains against his pearl-button shirt, and calloused hands that have roped a thousand mustangs, he makes the Marlboro Man seem wimpy. But if you look closely, you will notice a sacred eagle feather in his Stetson. Mr. Yowell is chief of the Western Shoshone National Council.

When an official warns protestors that they will be arrested if they cross the cattleguard that demarcates the boundary of the Test Site, Chief Yowell scowls that it is the Department of Energy who is trespassing on sacred Shoshone land. "We would be obliged," he says firmly, "if you would leave. And please take your damn nuclear waste and rent-a-cops with you."

While Chief Yowell is being handcuffed at the main gate, scores of protestors are breaking through the perimeter fence and fanning out across the desert. They are chased like rabbits by armed Wackenhuts in fast, low-slung dune-buggies. Some try to hide behind Joshua trees, but all will be eventually caught and returned to the concrete-and-razor-wire compound that serves as the Test Site's hoosegow. It is October 11, the day before the quincentenary of Columbus's crash landing in the New World.

The U.S. nuclear test program has been under almost constant siege since the Las Vegas—based American Peace Test (a direct-action offshoot of the old Moratorium) first encamped outside the NTS's Mercury gate in

1987. Since then more than ten thousand people have been arrested at APT mass demonstrations or in smaller actions ranging from Quaker prayer vigils to Greenpeace commando raids on ground zero itself. (In Violent Legacies Misrach includes a wonderful photograph of the "Princesses Against Plutonium," attired in radiation suits and death masks, illegally camped inside the NTS perimeter.) Dodging the Wackenhuts in the Nevada desert has become the rite of passage for a new generation of peace activists.

The fall 1992 Test Site mobilization—"Healing Global Wounds"—was a watershed in the history of anti-nuclear protest. In the first place, the action coincided with Congress's nine-month moratorium on nuclear testing (postponing until this September a test blast codenamed "Mighty Uncle"). At long last, the movement's strategic goal, a comprehensive test ban treaty, seemed tantalizingly within grasp. Secondly, the leadership within the movement has begun to be assumed by the indigenous peoples whose lands have been poisoned by nearly a half century of nuclear testing.

These two developments have a fascinating international connection. Washington's moratorium was a grudging response to Moscow's earlier, unilateral cessation of testing, while the Russian initiative was coerced from Yeltsin by unprecedented popular pressure. The revelation of a major nuclear accident at the Polygon in February 1989 provoked a non-violent uprising in Kazakhstan. The famed writer Olzhas Suleimenov used a televised poetry reading to urge Kazakhs to emulate the example of the Nevada demonstrations. Tens of thousands of protestors, some brandishing photographs of family members killed by cancer, flooded the streets of Semipalatinsk and Alma-Ata, and within a year the "Nevada-Semipalatinsk Movement" had become "the largest and most influential public organization in Kazakhstan, drawing its support from a broad range of people—from the intelligentsia to the working class."[49] Two years later, the Kazakh Supreme Soviet, as part of its declaration of independence, banned nuclear testing forever.

It was the world's first successful anti-nuclear revolution, and its organizers tried to spread its spirit with the formation of the Global Anti-Nuclear Alliance (GANA). They specifically hoped to reach out to other indigenous nations and communities victimized by nuclear colonialism. The Western Shoshones were amongst the first to respond. Unlike many other western tribes, Chief Yowell's people have never conceded U.S. sovereignty in the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah, and even insist on carrying their own national passport when travelling abroad. In conversations with the Kazakhs and activists from the Pacific test sites, they discovered a poignant kinship that eventually led to the joint GANA-Shoshone sponsorship of "Healing Global Wounds" with its twin demands to end nuclear testing and restore native land rights.

In the past some participants had criticized the American Peace Test encampments for their overwhelmingly countercultural character. Indeed, last

October as usual, the bulletin board at the camp's entrance gave directions to affinity groups, massage tables, brown rice, and karmic enhancements. But the Grateful Dead ambience was leavened by the presence of an authentic Great Basin united front that included Mormon and Paiute Indian Downwinders from the St. George area, former GIs exposed to the 1950s atmospheric tests, Nevada ranchers struggling to demilitarize public land (Citizen Alert), a representative of workers poisoned by plutonium at the giant Hanford nuclear plant, and the Reese River Valley Rosses, a Shoshone country-western band. In addition there were friends from Kazakhstan and Mururoa, as well as a footsore regiment of European cross-continent peace marchers.

The defeat of George Bush a month after "Healing Global Wounds" solidified optimism in the peace movement that the congressional moratorium would become a permanent test ban. The days of the Nevada Test Site seemed numbered. Yet to the dismay of the Western Shoshones, the Downwinders and the rest of the peace community, the new Democratic administration evinced immodest enthusiasm for the ardent wooing of the powerful nuclear-industrial complex. Cheered on by the Tory regime in London, which was eager to test the nuclear warhead for the RAF's new "TASM" missile in the Nevada desert, the Pentagon and the three giant atomic labs (Livermore, Los Alamos, and Sandia) came within a hairsbreadth of convincing Clinton to resume "Mighty Uncle." Only a last-minute revolt by twenty-three senators—alarmed that further testing might undermine the U.S.-led crusade against incipient nuclear powers like Iraq and North Korea—forced the White House to extend the moratorium.

Although the ban has remained in force, there is some evidence that the Pentagon has participated in tests by proxy in French Polynesia. In 1995 the White House, breaking with the policy of the Bush years, allowed the French military to airlift H-bomb components to Mururoa through U.S. airspace, using LAX as a stop-over point. The British Labor Party, echoing accounts in the French press, charged that Washington and London were silent partners in the internationally denounced Mururoa test series, sharing French data while providing Paris with logistical and diplomatic support.[50]

More recently, the spotlight has shifted back to Nevada where peace activists in spring 1997 were preparing for protests against NTS's new program of "zero yield" tests. The Department of Energy is planning to use high explosives to compress "old" plutonium to the brink of chain reaction, an open violation of the Comprehensive Test Ban agreement, in order to generate data for a computer study of "the effects of age on nuclear weapons." This is part of the Clinton administration's science-based Stockpile Stewardship program, which, critics allege, has merely shifted the nuclear armsrace into high-tech labs like Livermore's $1 billion National Ignition Facility where super-lasers will produce miniature nuclear explosions that will in

turn be studied by the next generation of "teraflop" (1 trillion calculations per second) supercomputers. Great Basin peace activists, like their Global Healing counterparts fear that such "virtual atomic tests," combined with data from "zero yield" blasts in Nevada, will encourage not only the maintenance, but the further development of strategic nuclear weapons. In the meantime, motorists will still have to "Stop for Demonstrators" at the Mercury exit.[51]

The Death Lab

January 1993. It has been one of the coldest winters in memory in the Great Basin. Truckers freeze in their stalled rigs on ice-bound Interstate 80 while flocks of sheep are swallowed whole by huge snow drifts. It is easy to miss the exit to Skull Valley.

An hour's drive west of Salt Lake City, Skull Valley is typical of the basin and range landscape that characterizes so much of the intermontane West. Ten thousand years ago it was an azure-blue fjord-arm of prehistoric Lake Bonneville (mother of the present Great Salt Lake), whose ancient shorelines are still etched across the face of the snow-capped Stansbury Mountains. Today the valley floor (when not snowed-in) is mostly given over to sagebrush, alkali dust, and the relics of the area's incomparably strange history.

A half-dozen abandoned ranch houses, now choked with tumbleweed, are all that remain of the immigrant British cottonmill workers—Engels's classic Lancashire proletariat—who were the Valley's first Mormon settlers in the late 1850s. The nearby ghost town of Iosepa testifies to the ordeal of several hundred native Hawaiian converts, arriving a generation later, who fought drought, homesickness, and leprosy. Their cemetery, with beautiful Polynesian names etched in Stansbury quartzite, is one of the most unexpected and poignant sites in the American West.[52]

Further south, a few surviving families of the Gosiute tribe—people of Utah's Dreamtime and first cousins to the Western Shoshone—operate the "Last Pony Express Station" (actually a convenience store) and lease the rest of their reservation to the Hercules Corporation for testing rockets and explosives. In 1918, after refusing to register for the draft, the Skull Valley and Deep Creek bands of the Gosiutes were rounded up by the Army in what Salt Lake City papers termed "the last Indian uprising."[53]

Finally, at the Valley's southern end, across from an incongruously large and solitary Mormon temple, a sign warns spies away from Dugway Proving Ground: since 1942, the primary test-site for U.S. chemical, biological, and incendiary weapons. Napalm was invented here and tried out on block-long replicas of German andJapanese workers' housing (parts of this eerie "doom city" still stand). Also tested here was the supersecret Anglo-American anthrax bomb (Project N) that Churchill, exasperated by the 1945 V-2 attacks

on London, wanted to use to kill twelve million Germans. Project W-47—which did incinerate Hiroshima and Nagasaki—was based nearby, just on the other side of Granite Mountain.[54]

In the postwar years, the Pentagon carried out a nightmarish sequence of live-subject experiments at Dugway. In 1955, for example, a cloud generator was used to saturate thirty volunteers—all Seventh-Day Adventist conscientious objectors—with potentially deadly Q Fever. Then, between August and October 1959, the Air Force deliberately let nuclear reactors melt down on eight occasions and "used forced air to ensure that the resulting radiation would spread to the wind. Sensors were set up over a 210-mile area to track the radiation clouds. When last detected they were headed toward the old U.S. 40 (now Interstate 80)."[55]

Most notoriously, the Army conducted 1,635 field trials of nerve gas, involving at least 500,000 pounds of the deadly agent, over Dugway between 1951 and 1969. Open-air nerve-gas releases were finally halted after a haywire 1968 experiment asphyxiated six thousand sheep on the neighboring Gosiute Reservation. Although the Army paid $1 million in damages, it refused to acknowledge any responsibility. Shrouded in secrecy and financed by a huge black budget, Dugway continued to operate without public scrutiny.[56]

Then in 1985 Senator Jeremy Stasser and writer Jeremy Rifkin teamed up to expose Pentagon plans to use recombinant genetic engineering to create "Andromeda strains" of killer microorganisms. Despite the American signature on the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention that banned their development, the Army proposed to build a high-containment laboratory at Dugway to "defensively" test its new designer bugs.[57]

Opposition to the Death Lab was led by Downwinders, Inc., a Salt Lake City–based group that grew out of solidarity with the radiation victims in the St. George area. In addition to local ranchers and college students, the Downwinders were able to rally support from doctors at the Latter Day Saints (Mormon) Hospital and, eventually, from the entire Utah Medical Association. Local unease with Dugway was further aggravated by the Army's admission that ultra-toxic organisms were regularly shipped through the U.S. mail.

The Pentagon, accustomed to red-carpet treatment in super-patriotic Utah, was stunned by the ensuing storm of public hearings and protests, as well as the breadth of the opposition. In September 1988 the Army reluctantly cancelled plans for its new "BL-4" lab. In a recent interview, Downwinders organizer Steve Erickson pointed out that "this was the first grassroots victory anywhere, ever, over germ or chemical warfare testing." In 1990, however, the Dugway authorities unexpectedly resurrected their biowar lab scheme, although now restricting the range of proposed tests to "natural" lethal organisms rather than biotech mutants.[58]

A year later, while Downwinders and their allies were still skirmishing with the Army over the possible environmental impact of the new lab, Desert Shield suddenly turned into Desert Storm. Washington worried openly about Iraq's terrifying arsenal of biological and chemical agents, and Dugway launched a crash program of experiments with anthrax, botulism, bubonic plague, and other micro-toxins in a renovated 1950s facility called Baker Lab. Simulations of these organisms were also tested in the atmosphere.

The Downwinders, together with the Utah Medical Association (dominated by Mormon doctors), went to the U.S. District Court to challenge the resumption of tests at the veteran Baker Lab as well as the plan for a new "life sciences test facility." Their case was built around the Army's noncompliance with federal environmental regulations as well as its scandalous failure to provide local hospitals with the training and serums to cope with a major biowar accident at Dugway. The fantastically toxic botulism virus, for example, has been tested at Dugway for decades, but not a single dose of the anti-toxin was available in Utah (indeed in 1993, there were only twelve doses on the entire West Coast).[59]

In filing suit, the Downwinders also wanted to clarify the role of chemical and biological weapons in the Gulf War. In the first place, they hoped to force the Army to reveal why it vaccinated tens of thousands of its troops with an experimental, and possibly dangerous, anti-botulism serum. Were GIs once again being used as Pentagon guinea pigs? Was there any connection between the vaccinations and the strange sickness—the so-called "Gulf War Syndrome"—brought home by so many veterans?

Secondly, the Downwinders hoped to shed more light on why the Bush administration allowed the sales of potential biological agents in the months before the invasion of Kuwait. "If the Army's justification for resuming tests at Dugway was the imminent Iraqi biowar threat," said Erickson, "then why did the Commerce Department previously allow $20 million of dangerous 'dual-use' biological materials to be sold to Iraq's Atomic Energy Commission? Were we trying to defend our troops against our own renegade bugs?"[60]

In the event, the Pentagon refused to answer these questions and the Downwinders lost their lawsuit, although they remain convinced that bioagents are prime suspects in the Gulf War Syndrome. Meanwhile, the Army completed the controversial Life Sciences Test Facility, and rumors began to fly of research on super-lethal fibroviruses like Ebola Fever. Then, in 1994, Lee Davidson, a reporter for the Mormon Deseret News, used the Freedom of Information Act to excavate the details of human-subject experiments in Dugway during the 1950s and 1960s. Two years later, former Dugway employees complained publicly for the first time about cancers and other disabilities that they believe were caused by chemical and biological testing. The

Department of Defense, finally, admitted that clean-up of Dugway's 143 major toxic sites may cost billions and take generations, if ever, to complete.[61]

The Great "Waste" Basin?

Grassroots protest in the intermontane states has repeatedly upset the Pentagon's best-made plans. Echoing sentiments frequently expressed at "Healing Global Wounds," Steve Erickson of the Downwinders boasts of the peace movement's dramatic breakthrough in the West over the past decade. "We have managed to defeat the MX and Midgetman missile systems, scuttle the proposed Canyonlands Nuclear Waste Facility, stop construction of Dugway's BL-4, and impose a temporary nuclear test ban. That's not a bad record for a bunch of cowboys and Indians in Nevada and Utah: two supposedly bedrock pro-military states!"[62]

Yet the struggle continues. The Downwinders and other groups, including the Western Shoshones and Citizen Alert, see an ominous new environmental and public-health menace under the apparently benign slogan of "demilitarization." With the abrupt ending of the Cold War, millions of aging strategic and tactical weapons, as well as six tons of military plutonium (the most poisonous substance that has ever existed in the geological history of the earth), must somehow be disposed of. As Seth Schulman warns, "the nationwide military toxic waste problem is monumental—a nightmare of almost overwhelming proportion."[63]

The Department of Defense's reaction, not surprisingly, has been to dump most of its obsolete missiles, chemical weaponry, and nuclear waste into the thinly populated triangle between Reno, Salt Lake City, and Las Vegas: an area that already contains perhaps one thousand "highly contaminated" sites (the exact number is a secret) on sixteen military bases and Department of Energy facilities.[64] The Great Basin, as in 1942 and 1950, has again been nominated for sacrifice.

The Pentagon's apocalyptic detritus, however, is a new regional cornucopia—the equivalent of postmodern Comstock—for a handful of powerful defense contractors and waste-treatment firms. As environmental journalist Triana Silton warned a few years ago, "a full-fledged corporate war is shaping up as part of the old military-industrial complex transforms itself into a new toxic waste-disposal complex."[65]

There are huge profits to be made disposing of old ordnance, rocket engines, chemical weapons, uranium trailings, radioactive soil, and the like. And company bottom-lines look even better when military recycling is combined with the processing of imported urban solid waste, medical debris, industrial toxics, and non-military radioactive waste. The big problem has

been to find compliant local governments willing to accept the poisoning of their natural and human landscapes.

No locality has been more eager to embrace the new political economy of toxic waste than Tooele County, just west of Salt Lake City. As one prominent activist complained to me, "the county commissioners have turned Tooele into the West's biggest economic red light district."[66] In addition to Dugway Proving Ground and the old Wendover and Deseret bombing ranges, the county is also home to the sprawling Tooele Army Depot, where nearly half of the Pentagon's chemical-weapons stockpile is awaiting incineration. Its non-military toxic assets include Magnesium Corporation of America's local smelter (the nation's leading producer of chlorine gas pollution) and the West Desert Hazardous Industry Area (WDHIA) (see map 19.3), which imports hazardous and radioactive waste from all over the country for burning in its two towering incinerators or burial in its three huge landfills.[67]

Most of these facilities have been embroiled in recent corruption or health-and-safety scandals. Utah's former state radiation-control director, for example, was accused in late December 1996 of extorting $600,000 ("in everything from cash to coins to condominiums") from Khosrow Semnani, the owner of Environcare, the low-level radioactive waste dump in the WDHIA. Semnani has contributed heavily to local legislators in a successful attempt to keep state taxes and fees on Environcare as low as possible. Whereas the two other states that license commercial sites for low-level waste, South Carolina and Washington, receive $235.00 and $13.75 per cubic foot respectively, Utah charges a negligible $.10 per cubic foot. As a result, radioactive waste has poured into the WDHIA from all over the country.[68]

Meanwhile, anxiety has soared over safety conditions at the half-billion-dollar chemical-weapons incinerator managed by EG&G Corporation at Tooele Army Depot. As the only operational incinerator in the continental United States (another, accident-ridden incinerator is located on isolated Johnson Atoll in the Pacific), the Depot is the key to the Pentagon's $31 billion chemical demilitarization program. Vehement public opposition has blocked incinerators originally planned for sites in seven other states. Only in job- and tax-hungry Tooele County, which has been promised $13 million "combat pay" over seven years, did the Army find a welcome mat.[69]

Yet as far back as 1989, reporters had obtained an internal report indicating that in a "worst case scenario" an accident at the plant could kill more than two thousand Tooele residents and spread nerve gas over the entire urbanized Wasatch Front. (The National Gulf War Resource Center in Washington, D.C. would later warn that "if there is a leak of sarin from the Tooele incinerator or one of the chemical warfare agent bunkers, residents of Salt Lake City may end up with Gulf War illness coming to a neighborhood near you.") Federal courts nonetheless rejected a last-minute suit by

Map 19.3

Location map of Tooele Valley and the West Desert

Hazardous Industry Area, Tooele County, Utah.

the Sierra Club and the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation to prevent the opening of the incinerator in August 1996.[70]

Within seventy-two hours of ignition, however, a nerve gas leak forced operators to shut down the facility. Another serious leak occurred a few months later. Then, in November 1996, the plant's former director corroborated the testimony of earlier whistleblowers when he publicly warned EG&G officials that "300 safety, quality and operational deficiencies" still plagued the operation. He also complained that the "plan is run by former Army officers who disregard safety risks and are too focused on ambitious incineration schedules." Environmental groups, meanwhile, have raised fears that even "successful" operation of the incinerator might release dangerous quantities of carcinogenic dioxins into the local ecosystem.[71]

Indeed, there is disturbing evidence that a sinister synergy of toxic environments may already be creating a slow holocaust comparable to the ordeal of the fallout-poisoned communities chronicled by Carole Gallagher. At the northeastern end of Tooele Valley, for example, Grantsville (pop. 5,000)

is currently under the shadow of the chlorine plume from Magnesium Corporation, the emissions from the hazmat incinerators in the WDHIA, and whatever is escaping from the Chemical Demilitarization Facility. In the past it has also been downwind of nuclear tests in Nevada and nerve-gas releases from Dugway, as well as clearly from the open detonation of old ordnance at the nearby but now closed North Area of the Army Depot.

For years Grantsville had lived under a growing sense of dread as cancer cases multiplied and the cemetery filled up with premature deaths, especially women in their thirties. As in a Stephen King novel, there was heavy gossip that something was radically wrong. Finally in January 1996, a group of residents, organized into the West Desert Healthy Environment Coalition (HEAL) by county librarian Chip Ward and councilwoman Janet Cook, conducted a survey of 650 local households, containing more than half of Grantsville's population.

To their horror, they discovered 201 cancer cases, 181 serious respiratory cases (not including bronchitis, allergies, or pneumonia), and 12 cases of multiple sclerosis. Although HEAL volunteers believe that majority Mormon residents reported only a fraction of their actual reproductive problems, they recorded 29 serious birth defects and 38 instances of major reproductive impairment. Two-thirds of the surveyed households, in other words, had cancer or a major disability in the family: many times the state and national averages. As Janet Cook told one journalist, "Southern Utah's got nothing on Grantsville."[72]

"Most remarkable," Ward observed, "was the way that cancer seemed to be concentrated among longtime residents." One source of historical exposure that Ward and others now think has been underestimated were the Dugway tests. "One respondent, for example, reported that she gave birth to seriously deformed twins several months after the infamous sheep kill in Skull Valley in 1968. Her doctor told her that he'd never seen so many birth defects as he did that year."[73]

But more than one incident is undoubtedly indicted in Grantsville's terrifying morbidity cluster. Environmental health experts have told HEAL that "cumulative, multiple exposures, with 'synergistic virulence' [the whole is greater than the sum of the parts] " best explain the local prevalence of cancers and lung diseases. In a downwind town where a majority of people work in hazardous occupations, including the Army Depot, Dugway, WDHIA, and the Magnesium Corporation, environmental exposure has been redoubled by occupational exposure, and vice versa.[74]

Consequently, West Desert HEAL, supported by Utah's Progressive Alliance of labor, environmental, and women's groups, has been demanding increased environmental monitoring, a moratorium on emissions and open detonation, complete documentation of past military testing, and a baseline regional health study with meaningful citizen participation. By early 1997

it had won legislative approval for the health survey and a radical reduction in Army detonations. The Magnesium Corporation, however, was still spewing chlorine and the Pentagon was still playing chicken with 13,616 tons of nerve gas.[75]

From a bar stool in the Dead Dog Saloon, Grantsville still seems like a living relic of that Old West of disenfranchised miners, cowboys, and Indians. Yet just a few miles down the road is the advance guard of approaching suburbia. Since 1995 metropolitan Salt Lake City has expanded, or, rather, exploded into northern Tooele Valley. The county seat, Tooele, has been featured in the New York Times as "one of the fastest-growing cities in the West," and a vast, billion-dollar planned suburb, Overlake, has been platted on its fringe.[76]

Although local developers deride the popular appeal of "tree-huggers" and anti-pollution groups, significant segments of the urban population will soon be in the toxic shadow of Tooele's nightmare industries. "When the new suburbanites wake up one morning and realize that they too are downwinders," Chip Ward predicts, "then environmental politics in Utah will really get interesting."[77]